Abstract

A patient with persistent refractory headaches from aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage was treated with monthly erenumab injections, a monoclonal antibody to the calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) receptor. These injections decreased the frequency and severity of the patient's debilitating headaches from daily to once or twice per month with positive improvement in function and quality of life. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the literature of a patient with persistent post‐subarachnoid hemorrhage headache that was successfully treated with an antibody against the CGRP receptor. This case report highlights the role of CGRP in post‐subarachnoid hemorrhage headaches and the potential role for CGRP pathway‐based therapies as an effective treatment.

Keywords: calcitonin gene–related peptide, erenumab, headache, migraine, subarachnoid hemorrhage, trigeminovascular system

Abbreviations

- aSAH‐HA

aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage headache

- CGRP

calcitonin gene–related peptide

- DCI

delayed cerebral ischemia

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a devastating clinical event associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Acutely, these patients often have complications such as rebleeding, vasospasm, delayed cerebral ischemia, hydrocephalus, or seizures. 1 Survivors of the initial ictus of SAH can experience long‐term complications such as stroke, vasospasm, hydrocephalus, neurocognitive dysfunction, epilepsy, and headaches. 2 , 3 Persistent headache attributed to past non‐traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (see International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition, section 6.2.4.2, hereafter called persistent post‐SAH headache) lasts longer than 3 months, and is a debilitating long‐term sequela of SAH. 4 They have a diurnal pattern of diffuse pressing or stabbing pain and can last from months to years after SAH. 4 , 5 , 6 In one study, persistent post‐SAH headaches were found to impair quality of life more than control individuals with chronic, non‐SAH–related headaches. 7 Many common anti‐headache medications are avoided in patients with a history of SAH due to possible risks such as vasospasm. 8

Calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) has been found to play an important role in both migraine pathogenesis and post‐SAH and traumatic brain injury neuroprotection. 9 Given CGRP's intersecting role as both a key mediator in headache development and post‐subarachnoid hemorrhage neuroprotection, this pathway presents itself as an interesting therapeutic target for the management of post‐SAH headache. Here we present the first known case report of a 55‐year‐old male who had a successful therapeutic response to erenumab, an antibody to the CGRP receptor, for his post‐SAH headaches.

CASE DISCUSSION

A 55‐year‐old male with past medical history of renal artery aneurysm, hypertension, and no prior history of headache presented to our practice with persistent headaches which began after sustaining a Hunt Hess 3, modified Fischer 4 aneurysmal SAH at the age of 47, secondary to a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. The aneurysm was successfully treated via endovascular coil embolization followed by open craniotomy for clipping of a small residual. He subsequently spent 1 month in the intensive care unit after the original hemorrhage, then 2 years at a rehabilitation facility. His post‐operative course was complicated by seizures which were stabilized with valproic acid and lamotrigine.

After the hemorrhage, he was left with severe, persistent, and daily throbbing headaches involving the whole head that would last for many hours. His headaches were exacerbated with activity and associated with difficulty concentrating and hyperacusis, which required the use of earplugs to leave the house; nevertheless, he denied nausea, vomiting, or symptoms of aura. His life became very restricted, spending much of the day in his bedroom and being unable to return to work. His neurological examination was unremarkable except for mild postural tremor, attributed to valproic acid. The valproic acid was successfully tapered off gradually to achieve lamotrigine monotherapy for seizures, without worsening of his headaches. Over the next year, the patient attempted numerous pharmacotherapies to achieve headache control. He underwent acetaminophen taper for possible medication‐overuse headache, but his headaches persisted. Topiramate was considered but deferred due to his history of renal stones. The patient was already taking metoprolol for treatment of his hypertension, so adding another beta‐blocker was not considered. The patient then tried non‐pharmaceutical therapies such as a combination product of magnesium, riboflavin, feverfew, and butterbur as well as acupuncture, which led to no improvement. He next started amitriptyline 30 mg daily, which provided some relief. The patient reported a decrease in headache frequency to twice per week and improved hyperacusis. Unfortunately, the patient was unable to tolerate the amitriptyline due to side effects of fatigue, xerostomia, and urinary retention. The amitriptyline was transitioned to nortriptyline, 10 mg nightly, with continued headaches and adverse effects.

Still without reasonable headache control, the patient agreed to a trial of an antibody to the CGRP receptor, erenumab. We considered such an approach because of the presentation of the migraine‐like headache quality, severity duration, and presence of hyperacusis, and because of the known role CGRP plays in post‐SAH neuroprotection. We hypothesized that the high concentrations of CGRP seen after SAH may have led to hypersensitization of the trigeminovascular nociceptive pathway, leading to the patient's persistent headaches. 5 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

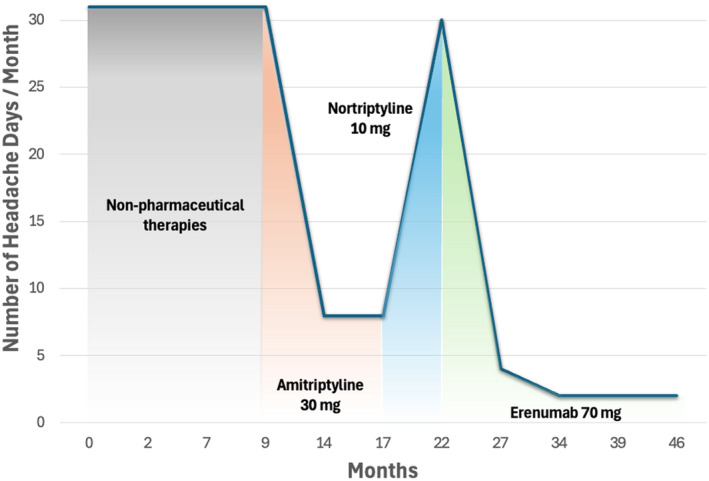

The patient started monthly injections of erenumab 70 mg, resulting in gradual improvement in headaches (Figure 1). After 3 months, headaches had reduced from daily to once weekly, lasting only several hours. By 6 months of therapy, headaches occurred twice per month. He was able to taper off the nortriptyline. At 18 months of therapy, he only had one to two headaches per month lasting only a few hours at a time. Given his excellent response, the patient was maintained on the 70 mg dose. His sound sensitivity also improved significantly. He reported being able to leave his home, tolerate noisier environments, and return to work. The patient has provided written informed consent to have his case published.

FIGURE 1.

The number of headache days per month as reported by the patient. Month 0 indicates the start of the patient's headache diary. After initiating amitriptyline, the patient reported a reduction in headache days but developed intolerable adverse effects of fatigue, xerostomia, and urinary retention. Nortriptyline was then started, but adverse effects persisted, and headache days increased. After starting erenumab, the number of headache days per month decreased significantly without any adverse effects. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

Headache is a prevalent and burdensome long‐term sequela of non‐traumatic SAH. Post‐aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage headaches (“post‐aSAH‐HA”) have largely been attributed to a persistent state of vascular hypersensitivity, oxidation‐induced brain injury, and heightened neuroinflammation after the original ictus of hemorrhage. 5 , 8 , 12 , 13 CGRP has been identified as a key neurochemical mediator in post‐SAH vasodilation and neuroprotection as well as in the sensitization of the trigeminovascular nociceptive pathway. 5 , 8 , 9 Here we present the first case report to our knowledge of the successful management of post‐aSAH‐HA with the use of an antibody to the CGRP receptor.

The CGRP pathway as a target for post‐subarachnoid hemorrhage headache

The CGRP pathway has an important vasodilatory role in neuroprotection from vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. 10 , 14 , 15 , 16 Nevertheless, there have been few published investigations evaluating the role of CGRP in post‐aSAH‐HA. 5 , 9 , 10 , 17 In SAH, CGRP is released in a large bolus immediately after the hemorrhage. With serum concentrations sharply rising and then dissipating by a month after the ictus, it is hypothesized to be released as a neuroprotective mediator in combating cerebral vasoconstriction. 9 , 10 , 11 , 18 , 19 , 20 Regarding headaches, the large efflux of CGRP may lead to increased trigeminal hypersensitization and thus the development of chronic cephalgia. 9 , 10 Interestingly in one study of patients with SAH, those with higher mean serum CGRP levels had significantly poorer performance on their health‐related quality of life questionnaire, worst in the pain and somatoform syndrome categories. 10

Clinical considerations for CGRP pathway therapy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

Employing CGRP pathway antagonists for post‐aSAH‐HA draws concerns regarding potential vasoconstrictive effects in this post‐hemorrhagic period. Delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) is a significant morbidity after aneurysmal SAH. 21 The risk of DCI is highest 4 to 10 days after aneurysmal rupture and can occur as far out as 6 weeks from the inciting ictus. 21 , 22 , 23 Out of concern for DCI, the use of traditional headache medications has been limited in patients with aneurysmal SAH and others who are at risk for stroke or cardiovascular disease. 24 The question of when to initiate anti‐CGRP pathway therapy in the post‐SAH period has not yet been explored and requires further clinical investigation. We recommend against initiation of therapy until the risk of DCI is minimal—at least 3 to 6 weeks after ictus in our experience. The use of erenumab in our case was years after the window for cerebral ischemia attributable to DCI. Regarding the duration of therapy, the natural history of post‐aSAH headache has been described in the literature to last from many months to even years after rupture. 5 , 6 Therefore, the total duration of therapy may vary among patients. Importantly, erenumab is not metabolized by cytochrome P‐450 enzymes and is therefore unlikely to interact with other drugs, such as anti‐seizure medications, which induce or inhibit cytochrome P‐450. 25 , 26 , 27

Determining the clinical effectiveness of this medication for post‐aSAH‐HA will require further investigation

As presented here, erenumab 70 mg injected monthly was effective and well tolerated in our patient. Because the patient demonstrated a steadily improved response to the therapy and with his history of sensitivity to medication side effects, the dose was never escalated. Given our patient's long‐standing headaches, which had been frequent, debilitating, and refractory to multiple agents for years after his aneurysmal rupture, we believe it to be unlikely, but still possible, that these headaches remitted according to their natural history. While the etiology of persistent headaches after subarachnoid hemorrhage is likely multifactorial, there is growing evidence, including the case presented here, that CGRP pathway‐based headache therapy deserves further clinical investigation.

CONCLUSION

Here we present the first case report to our knowledge of the successful use of a monoclonal antibody against the CGRP receptor (erenumab) for post‐aSAH‐HA. CGRP has been shown to be an important mediator role in both headache pathogenesis and post‐SAH/traumatic brain injury neuroprotection. Prospective studies into the safety and efficacy of CGRP pathway therapies in patients with persistent headaches secondary to prior non‐traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage may be warranted.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ajay Gandhi: Data curation; writing – original draft. Travis R. Quinoa: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Eric Geller: Conceptualization; data curation; supervision. Priyank Khandelwal: Conceptualization; supervision. Pankaj K. Agarwalla: Conceptualization; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Travis R. Quinoa, Ajay Gandhi, Eric Geller, Priyank Khandelwal, and Pankaj K. Agarwalla declare no conflicts of interest.

Gandhi A, Quinoa TR, Geller E, Khandelwal P, Agarwalla PK. Erenumab in a patient with persistent headaches after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A case report of an effective treatment. Headache. 2025;65:373‐376. doi: 10.1111/head.14884

REFERENCES

- 1. Ikawa F, Michihata N, Matsushige T, et al. In‐hospital mortality and poor outcome after surgical clipping and endovascular coiling for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage using nationwide databases: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43:655‐667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ogden JA, Utley T, Mee EW. Neurological and psychosocial outcome 4 to 7 years after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:25‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schatlo B, Fung C, Stienen MN, et al. Incidence and outcome of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: the swiss study on subarachnoid hemorrhage (Swiss SOS). Stroke. 2021;52:344‐347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huckhagel T, Klinger R, Schmidt NO, Regelsberger J, Westphal M, Czorlich P. The burden of headache following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective single‐center cross‐sectional analysis. Acta Neurochir. 2020;162:893‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen AP, Marcussen NS, Klit H, Kasch H, Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. Development of persistent headache following stroke: a 3‐year follow‐up. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:399‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaastra B, Carmichael H, Galea I, Bulters D. Duration and characteristics of persistent headache following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Headache. 2022;62:1376‐1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sorrentino ZA, Laurent D, Hernandez J, et al. Headache persisting after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a narrative review of pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Headache. 2022;62:1120‐1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehkri Y, Hanna C, Sriram S, Lucke‐Wold B, Johnson RD, Busl K. Calcitonin gene‐related peptide and neurologic injury: an emerging target for headache management. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2022;220:107355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bründl E, Proescholdt M, Störr EM, et al. The endogenous neuropeptide calcitonin gene‐related peptide after spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage‐a potential psychoactive prognostic serum biomarker of pain‐associated neuropsychological symptoms. Front Neurol. 2022;13:889213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schebesch K‐M, Herbst A, Bele S, et al. Calcitonin‐gene related peptide and cerebral vasospasm. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:584‐586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu F, Liu Z, Li G, et al. Inflammation and oxidative stress: potential targets for improving prognosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:739506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu L, Wang W, Lai N, Tong J, Wang G, Tang D. Association between pro‐inflammatory cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid and headache in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;366:577841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flynn LMC, Begg CJ, Macleod MR, Andrews PJD. Alpha calcitonin gene‐related peptide increases cerebral vessel diameter in animal models of subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Front Neurol. 2017;8:357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johansson SE, Abdolalizadeh B, Sheykhzade M, Edvinsson L, Sams A. Vascular pathology of large cerebral arteries in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: vasoconstriction, functional CGRP depletion and maintained CGRP sensitivity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;846:109‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao M, Kaiser E, Cucchiara B, Zuflacht J. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome exacerbation after calcitonin gene‐related peptide inhibitor administration. Neurohospitalist. 2023;13:415‐418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tran Dinh YR, Debdi M, Couraud JY, Creminon C, Seylaz J, Sercombe R. Time course of variations in rabbit cerebrospinal fluid levels of calcitonin gene‐related peptide‐ and substance P‐like immunoreactivity in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1994;25:160‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kee Z, Kodji X, Brain SD. The role of calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) in neurogenic vasodilation and its cardioprotective effects. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumar A, Williamson M, Hess A, DiPette DJ, Potts JD. Alpha‐calcitonin gene related peptide: new therapeutic strategies for the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease and migraine. Front Physiol. 2022;13:826122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Juul R, Hara H, Gisvold SE, et al. Alterations in perivascular dilatory neuropeptides (CGRP, SP, VIP) in the external jugular vein and in the cerebrospinal fluid following subarachnoid haemorrhage in man. Acta Neurochir. 1995;132:32‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vergouwen MDI, Vermeulen M, van Gijn J, et al. Definition of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage as an outcome event in clinical trials and observational studies. Stroke. 2010;41:2391‐2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dodd WS, Laurent D, Dumont AS, et al. Pathophysiology of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e021845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin‐Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2023;54:e314‐e370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petersen CL, Hougaard A, Gaist D, Hallas J. Risk of stroke and myocardial infarction among initiators of triptans. JAMA Neurol. 2024;81(3):248‐254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. AMGEN . Aimovig (erenumab‐aooe) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 21, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761077s000lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lundbeck . Vyepti (eptinezumab‐jjmr) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 21, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761119s000lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA . Ajovy (fremanezumab‐vfrm) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2020. Accessed May 21, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761089s002lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]