Abstract

Overexpression of the growth factor receptor subunit c-erbB2, leading to its ligand-independent homodimerization and activation, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of mammary carcinoma. Here, we have examined the effects of c-erbB2 on the adhesive properties of a mammary epithelial cell line, HB2/tnz34, in which c-erbB2 homodimerization can be induced by means of a transfected hybrid “trk-neu” construct. trk-neu consists of the extracellular domain of the trkA nerve growth factor (NGF) receptor fused to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of c-erbB2, allowing NGF-induced c-erbB2 homodimer signaling. Both spreading and adhesion on collagen surfaces were impaired on c-erbB2 activation in HB2/tnz34 cells. Antibody-mediated stimulation of α2β1 integrin function restored adhesion, suggesting a direct role for c-erbB2 in integrin inactivation. Using pharmacological inhibitors and transient transfections, we identified signaling pathways required for suppression of integrin function by c-erbB2. Among these was the MEK-ERK pathway, previously implicated in integrin inactivation. However, we could also show that downstream of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (PKB) acted as a previously unknown, potent inhibitor of integrin function and mediator of the disruptive effects of c-erbB2 on adhesion and morphogenesis. The integrin-linked kinase, previously identified as a PKB coactivator, was also found to be required for integrin inactivation by c-erbB2. In addition, the PI3K-dependent mTOR/S6 kinase pathway was shown to mediate c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion (but not spreading) independently of PKB. Overexpression of MEK1 or PKB suppressed adhesion without requirement for c-erbB2 activation, suggesting that these two pathways partake in integrin inhibition by targeting common downstream effectors. These results demonstrate a major novel role for PI3K and PKB in regulation of integrin function.

INTRODUCTION

c-erbB2 is a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor tyrosine kinase family and forms functional receptors for various growth factors (such as EGF and heregulin) by heterodimerization with other members of the same receptor family. However, no ligand has been found that binds a c-erbB2 homodimer; instead, homodimerization is thought to occur in a ligand-independent manner on overexpression of c-erbB2. This phenomenon is of considerable interest in cancer research, because a number of studies have linked c-erbB2 overexpression to poor prognosis in breast carcinomas (De Potter and Schelfhout, 1995). Studies of forced c-erbB2 overexpression in animals and cell lines have demonstrated the oncogenic potential of c-erbB2, and spontaneous homodimerization leading to tyrosine kinase activation is most likely an important mechanism for the oncogenicity of c-erbB2 overexpression (Weiner et al., 1989; Siegel and Muller, 1996).

Because high constitutive overexpression of c-erbB2 in mammary epithelial cells can be associated with irreversible changes in cell phenotype, such as loss of epithelial characteristics and acquisition of anchorage-independent growth (D'Souza et al., 1993), studies of the early phases in c-erbB2–induced cell transformation require an inducible system in which c-erbB2 homodimerization can be regulated. Such a system was recently developed (Baeckström et al., 2000) by transfection of the immortalized mammary epithelial cell line HB2 (Berdichevsky et al., 1994a) with a hybrid receptor construct, “trk-neu” (Sachs et al., 1996), consisting of the extracellular domain of the trkA nerve growth factor (NGF) receptor fused to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of c-erbB2. Treatment of these transfectants with NGF can stimulate the intracellular effects of c-erbB2 homodimerization, leading to tyrosine kinase activation and substrate domain phosphorylation. In HB2 transfectants expressing high levels of the trk-neu hybrid, NGF-induced homodimerization resulted in a dramatic disruption of morphogenesis of cells grown in three-dimensional culture in collagen, causing cells to grow in a scattered manner as opposed to the multicellular, compact, and spherical morphology of untreated transfectants and parental HB2 cells (Baeckström et al., 2000). The disrupted morphology of NGF-treated transfectants, which was accompanied by decreased proliferation and extensive apoptosis, could be completely restored by treatment with antibodies that activate the collagen-binding integrin α2β1, indicating that the morphogenetic effects of c-erbB2 signaling occur by integrin inactivation.

To dissect the intracellular signaling mechanisms leading from c-erbB2 homodimerization to inhibition of integrin-dependent morphogenesis, a more rapid and tractable assay for integrin function and morphogenesis than three-dimensional culture is desirable. In the present study, we have instead used c-erbB2–induced inhibition of cell adhesion and spreading on collagen as a readout in a series of transient transfection and inhibitor treatment experiments to identify possible signaling mediators of the antiadhesive properties of c-erbB2. The results of these assays implicate the extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases and protein kinase B (PKB or c-Akt) as parallel and essential components of the pathways linking c-erbB2 signaling to inhibition of integrin function and morphogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Solubilized bovine collagen I (Vitrogen 100) was obtained from Cohesion Technologies, Palo Alto, CA. 2.5S NGF from mouse submaxillary gland was purchased from Promega, Madison, WI. DMRIE-C reagent was from Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD. The substances PD98059, LY294002, wortmannin, actinomycin D, calphostin C, chelerythrine chloride, H-89, and bisindolylmaleimide 1 (BIMI) were purchased from Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA. Cycloheximide, cytochalasin D, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG), and X-gal were obtained from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Polyethyleneimine (25 kDa) was from Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI. Antibodies against PKB, ERK, p70 S6 kinase (S6K), and their respective phosphorylation-activated forms and antiserum against PTEN were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The blocking antibodies FB12, P1E6, and P1B5 against integrins α1, α2, and α3, respectively, and the integrin α2β1 stimulatory antibody JBS2 were obtained from Chemicon, Temecula, CA. Hybridoma cells producing the TS2/16 (stimulatory) and P5D2 (inhibitory) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the β1 integrin subunit were purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa, respectively. The HAS4 stimulatory mAb against integrin α2 (Tenchini et al., 1993) was a generous gift from Dr. Fiona Watt, Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London, UK. Clone 3, a mAb against integrin-linked kinase (ILK), was from BD Transduction Laboratories. Antiserum against MEK1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA.

cDNA Constructs

The expression plasmids used in this study were gifts generously provided by the following researchers: pMT2/ILK, pMT2/ILK(K220 M), and pMT2/ILK(S343D) containing cDNA coding for wild-type, dominant-negative, and activated integrin-linked kinase (ILK), respectively, were from Dr. Ian Hiles, GlaxoWellcome, Uxbridge, United Kingdom; pCMV5.SNE/PKBα and pCMV5.SNE/PKBα(K179A), used for expression of HA-tagged wild-type and dominant-negative PKB-α, respectively, were from Dr. Brian A. Hemmings, Friedrich Miescher Institut, Zürich, Switzerland; pCEP4/PTEN coding for wild-type PTEN phosphatase was from Dr. Ramon Parsons, Columbia University, New York; and pECE/HA-MEK1-ca, coding for a constitutively active mutant (S218D/S222D) of hamster MEK1 (Pages et al., 1994), was a gift from Pär Gerwins, Rudbeck Laboratory, University of Uppsala, Sweden. The reporter plasmids pCMVβ and pEGFP-C1 coding for LacZ and green fluorescent protein (GFP), respectively, were from Clontech, Cambridge, UK. Plasmids were propagated in appropriate Escherichia coli strains and purified by use of the JetStar plasmid purification system (Genomed, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany).

Cell Culture

The HB2/tnz34 cell line, (Baeckström et al., 2000) a high-expressing trk-neu transfectant derived from the SV40-immortalized human mammary epithelial cell line HB2 (Berdichevsky et al., 1994a), was grown in DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 10 μg/ml insulin, and 5 μg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA).

Inhibitor Treatments

All pharmacological inhibitors were administered as stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and control cells were given the corresponding amount of pure DMSO. Inhibitor concentrations were generally chosen in the range of 5–10 times the IC50 value supplied by the manufacturer. Different concentrations were always tested to rule out overdosage or underdosage effects.

Spreading Assays

Thin (∼150 μm) layers of polymerized collagen I were prepared by smearing 100 μl of neutralized collagen I over the surface of the wells of six-well plates (before the application of collagen, the edges of the wells had been prepared with sterilized vacuum grease to prevent accumulation of liquid at the well periphery). After polymerization for 2 h at 37°C, 1 × 104 to 2 × 104 HB2/tnz34 cells were plated as a single-cell suspension in 2 ml complete medium per well and incubated for 2 d. The cells were then transfected in situ (see below) or subjected to treatments with NGF (10 ng/ml) and/or inhibitors for an additional 1–2 d before fixation with 2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutardialdehyde in PBS. Spreading was evaluated in untransfected cells by visual inspection of two 4× magnification videomicrographs per sample in which cells were scored either as “round” (>50% of the cell periphery visible as a sharp edge) or “spread” (>50% diffuse cell boundary). Inhibition of spreading was calculated as %Ii = (1 − si/s0) × 100, where s0 is the frequency of spread cells in NGF-untreated controls and si is the frequency of spread cells in sample i. At least 200 cells per sample per micrograph were evaluated.

Spreading assays of transfected cells were performed after DMRIE-C transfection as described below. Cells were kept with or without NGF (10 ng/ml) for 2 d after transfection (see below) before being fixed, washed once with PBS, and developed with 200 μl X-gal stain (PBS, 3 mM MgCl2, 6.6 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 6.6 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], 0.6 mg/ml X-gal) per well. Transfected cells were evaluated according to the criteria outlined above, but scoring was performed directly under a light microscope and restricted to cells stained blue by X-gal staining.

Transfections

For analysis of transfected cells in spreading assays, transient transfections of HB2/tnz34 cells growing on collagen were performed as follows. For each well, 1 μl of DMRIE-C reagent was mixed and incubated for 30 min with 100 μl serum-free medium before the addition of another 100 μl serum-free medium containing a total of 1.5 μg plasmid DNA (0.75 μg plasmid containing gene of interest and 0.75 μg of the LacZ expression vector pCMVβ [Clontech]; control samples were transfected with 1.5 μg of pCMVβ only). The transfection mixture was kept for another 15 min at room temperature before 200 μl was transferred to each well (wells were washed with serum-free medium before transfection). After incubation for 5 h in CO2 incubator, the transfection mixture was removed, and wells were washed once with serum-containing medium and kept overnight with serum-containing medium before incubation with or without NGF.

To prepare transiently transfected cells for use in the adhesion assays, polyethyleneimine transfections were used. For one 6-cm tissue culture dish, a total of 6 μg plasmid DNA was added to 6 μl 20% glucose solution, and this mixture was then added to 5 μl 0.1 M polyethyleneimine solution, buffered to pH 7.0. After thorough mixing, deionized water was added to 60 μl, and the mixture was left for 10 min at room temperature. This solution was then mixed with 4 ml of fresh complete serum-containing cell culture medium and added to HB2/tnz34 cells grown to 60–70% confluence. The cells were then kept with the DNA-PEI complex–containing medium for 2 d before being detached and subjected to adhesion assay.

Adhesion Assays

Ninety-six–well microtiter plates were coated with monomeric collagen by dispensing Vitrogen 100 serially diluted (10 - 0.005 μg/ml) in 10 mM HCl at 50 μl/well and incubating overnight at +4°C. Plates were then blocked by incubation with 100 μl/well of PBS containing 0.1% heat-treated BSA at 37°C for 1 h. Subconfluent cultures of HB2/tnz34 cells were detached by incubation with Puck's saline containing 0.02% EDTA, mixed with an equal volume of serum-containing medium, and passed through a 23-gauge needle to create a single-cell suspension. Cells were then washed in serum-free medium and resuspended at a density of 2.5 × 105/ml in serum-free medium with 5 mM MgCl2. The cells were then pretreated with antibodies or inhibitors (where applicable) for 1 h before addition of NGF (standard concentration, 50 ng/ml) where applicable, followed by another 1-h incubation (both incubation steps were performed at room temperature). A cell suspension (100 μl) was then dispensed in each well of the coated microtiter plates, and the plates were left in the incubator for 1 h. Nonadherent cells were then removed by inversion and flicking of plates, followed by washing three times by immersion of the plate in PBS containing 5 mM MgCl2 and aspiration of buffer by water suction connected to a 21-gauge needle. The amount of adherent cells was quantified by crystal violet staining after fixation with 4% formaldehyde as described (Wu et al., 1999).

Adhesion assay of transfected cells was carried out 2 d after PEI transfection. Except as otherwise stated, cells were cotransfected with 3 μg each of the construct of interest and the LacZ-encoding vector pCMVβ; control cells were transfected with 6 μg pCMVβ. After fixation, adhered transfected cells were detected by incubation with the chromogenic LacZ substrate ONPG (0.88 mg ONPG/ml in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing freshly added 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.31% vol/vol β-mercaptoethanol) and quantified by measurement of the absorbance at 490 nm. Differences in LacZ expression levels between different transfections were compensated for as follows. For each transfection, duplicate aliquots containing 5 × 104 cells in suspension were incubated with ONPG, and the absorbance was measured to yield the specific LacZ activity. For each adhesion assay, the absorbance values were then normalized by division with the specific LacZ activity of the transfection in question.

In all adhesion assays, values from duplicate collagen dilution series were then used to calculate ED50 values, i.e., the amount of collagen coated on a well that was required to obtain half-maximal binding under the given experimental conditions.

This was achieved by plotting corrected absorbance versus the logarithm of the collagen concentration, making linear regression analyses of the linear parts of the plots and relating the line parameters to the highest absorbance value obtained in the control series.

Flow Cytometry

HB2/tnz34 cells were detached, washed and incubated with or without NGF as described under Adhesion Assays. The cell suspensions were then transferred to ice and mixed with mAbs against integrin subunits. After a 1-h incubation, the cells were washed three times with cold FACS diluent (DMEM, 10% FCS, 0.02% sodium azide) and then incubated for 1 h on ice with fluorescein-conjugated antimouse immunoglobulin antiserum (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), diluted 1:50 in FACS diluent (in GFP-transfected cells, antibody binding was detected with biotinylated antimouse immunoglobulin antiserum [Dako] followed by allophycocyanin-labeled streptavidin [Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland], both diluted 1:100). After three more washes in FACS diluent, cells were resuspended in PBS and analyzed in a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Western Blots

Lysates of HB2/tnz34 cells growing on plastic were prepared from subconfluent cultures grown on 60-mm cell culture dishes. Cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100 containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), supplemented with 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM NaF. After protein concentration determination (BCA assay, Pierce), normalized protein amounts were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, separated, and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Hybond-P, Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL). Membranes were blocked in PBS containing 5% dry milk and 0.1% Tween-20, treated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer or TBS with 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20 according to the antibody supplier's instructions, and washed three times with PBS–0.1% Tween-20. Bound antibody was detected with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako) followed by visualization with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden).

RESULTS

Induced c-erbB2 Homodimerization Inhibits Spreading and Adhesion of Mammary Epithelial Cells on Collagen

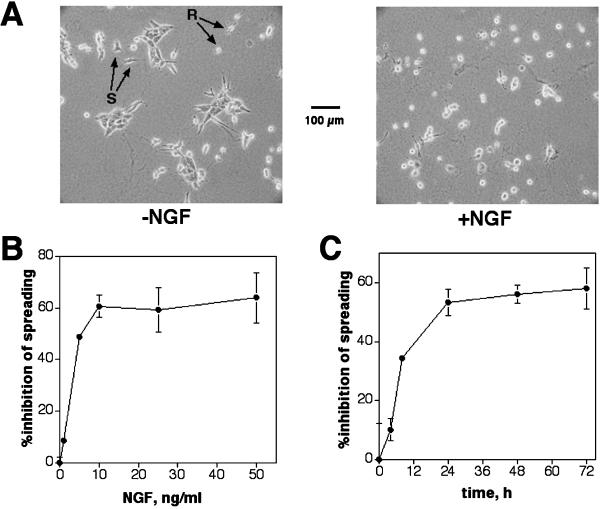

HB2/tnz34 is a high-expressing trk-neu transfectant of the mammary epithelial cell line HB2 that exhibits a striking disruption of integrin-dependent morphogenesis on c-erbB2 homodimer signaling induced by NGF treatment when grown in a three-dimensional collagen matrix (Baeckström et al., 2000). To understand the molecular mechanism behind this observation, we wished to identify the intracellular events that link c-erbB2 homodimer signaling with inhibition of morphogenesis. Because the morphogenesis assay used in the previous study requires that cells survive and proliferate for ∼1 week, we wished to develop an assay for integrin-dependent morphogenesis that was faster and thus more amenable to pharmacological and genetic manipulation than three-dimensional culture. Therefore, we chose to study spreading on collagen as a simplified morphogenesis assay. In the absence of c-erbB2 signaling, HB2/tnz34 cells spread on a polymerized collagen surface, typically reaching 75% flat cells after 3 d; however, NGF treatment strongly inhibited this spreading in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1, A and B). By adding NGF to the cells at different time points during a 72-h incubation, we could conclude that the suppressing effect of c-erbB2 signaling on spreading reached a plateau after ∼24 h of induction (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

c-erbB2 homodimer signaling induced by NGF treatment of trk-neu–transfected cells inhibits spreading and promotes scattering. (A) Morphology of HB2/tnz34 transfectants grown on polymerized collagen for 3 d in the absence or presence of 10 ng/ml NGF. Examples of cells scored as spread (S) or round (R) are indicated by the arrows. (B) Dose dependence of spreading inhibition. Cells were grown for 2 d on polymerized collagen before addition of NGF to the concentrations indicated. Spreading was evaluated after 24 h of treatment by scoring >250 cells per sample in duplicate. (C) Kinetics of spreading inhibition. NGF was added to cells at the indicated times before fixation, which was performed on day 3 after plating.

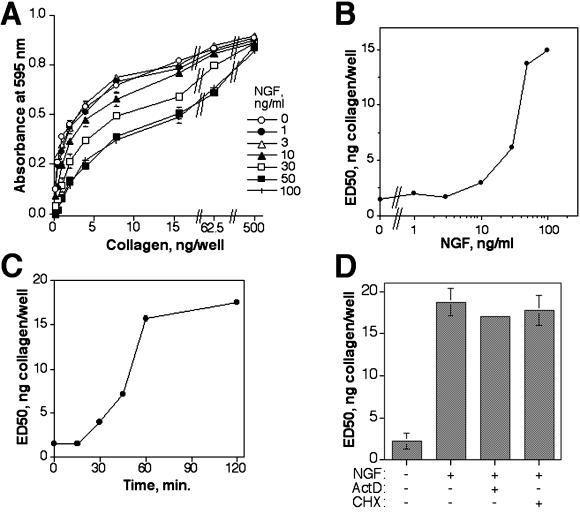

It has also been shown previously that the disruption of morphogenesis in collagen caused by c-erbB2 could be reversed by treatment with antibodies that activate β1 or α2 integrins (Baeckström et al., 2000). Because this result indicated that the morphogenetic disruption seen in NGF-activated HB2/tnz34 cells is caused by integrin inactivation, it was of interest to directly assess the possible influence of c-erbB2 on integrin function. To that end, we measured the capacity of untreated and NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells in suspension to adhere to monomeric collagen coated in serial dilutions in microtiter wells. As shown in Figure 2A, adhesion was indistinguishable (∼70% cells bound, data not shown) between controls and NGF-treated cells at high collagen densities (500 ng/well); however, under conditions in which collagen was limiting, a pronounced, dose-dependent suppression of adhesion was observed with NGF treatment (Figure 2A). To be able to compare large and complex sets of data, the results of the adhesion assays in the rest of this article are presented as the amount of coated collagen required for half-maximal binding (ED50; see MATERIALS AND METHODS for details on calculation); as an example, the ED50 values corresponding to the data from Figure 2A are presented in Figure 2B, plotted against the NGF concentration. From these figures, it can be seen that the c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion reached a plateau at NGF doses ≥50 ng/ml, where the ED50 value was typically 10 times higher than in NGF-untreated cells (fold increase average of >40 assays = 9.86).

Figure 2.

c-erbB2 homodimer signaling inhibits primary adhesion of HB2/tnz34 cells to monomeric collagen. Cells were pretreated with NGF for 1 h before plating and incubation for 1 h in microtiter plates coated with serial dilutions of collagen I (starting at 0.5 μg/well). The amount of adherent cells was quantified by crystal violet staining. (A) Dependence of the adhesion-suppressing effect of c-erbB2 on NGF concentration. (B) Data from A presented as ED50 values (collagen coating amount required for half-maximal binding), calculated as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS, plotted against NGF concentration. Note the logarithmic scale of the x axis. (C) Kinetics of adhesion inhibition by c-erbB2 as measured in an “accelerated” adhesion assay. HB2/tnz34 cells were pretreated with 50 ng/ml for the time periods indicated before being transferred to collagen-coated 96-well plates. The plates were then centrifuged at 200 × g for 3 min, and the amount of adhered cells and ED50 values were measured as above. (D) c-erbB2 inhibits adhesion to collagen in a manner independent on transcription and translation. Suspended HB2/tnz34 cells were pretreated with 2 μM actinomycin D (ActD) or 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) or left untreated for 1 h before incubation with or with-out 50 ng/ml NGF. (A–C) Data are representative values from experiments performed in duplicate and repeated three times; (D) data show averages and SDs of two separate experiments performed in duplicate.

Using an accelerated adhesion assay (in which cells were briefly centrifuged to avoid the time delay required for sedimentation), we could observe inhibition of adhesion after a minimum of 30 min of c-erbB2 signaling, reaching maximum level after 1 h (Figure 2C). As expected for such a rapid response, c-erbB2–induced adhesion downregulation was independent of both transcription and protein synthesis, as shown by its insensitivity to treatment with actinomycin D and cycloheximide, respectively (Figure 2D). The efficiency of cycloheximide treatment was verified in metabolic labeling experiments in which cycloheximide completely abrogated the incorporation of [35S]methionine into proteins (data not shown). No NGF-induced effect on adhesion or spreading was observed in control transfectants not expressing trk-neu (data not shown).

Adhesion to Collagen of HB2/tnz34 Cells Is Mediated by Integrin α2β1, the Function but Not Surface Abundance of Which Is Affected by c-erbB2

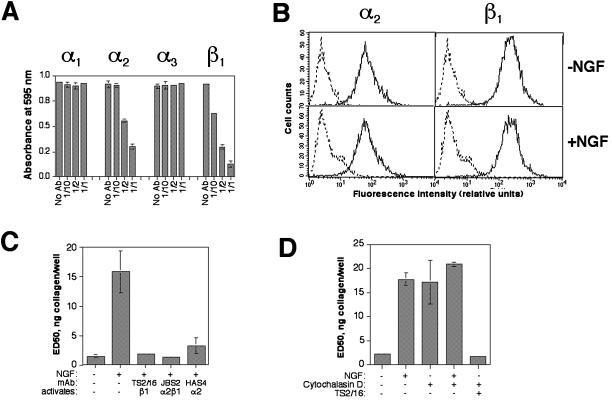

We next wished to identify the specific integrin(s) of importance for the binding of HB2/tnz34 cells to collagen in our adhesion assay. Cells were therefore pretreated with blocking antibodies to the collagen-binding integrin subunits α1, α2, and α3 and their heterodimerization partner β1 before their adhesion to collagen was analyzed. As shown in Figure 3A, adhesion was strongly suppressed by antibodies against the α2 and β1 subunits, whereas inhibition of α1, which is poorly expressed in these cells (Berdichevsky et al., 1994b, and our unpublished results), or α3 had no effect on adhesion. We thus concluded that the main integrin responsible for collagen binding under these conditions was α2β1.

Figure 3.

Integrin and cytoskeleton dependence of HB2/tnz34 cell adhesion to collagen and its regulation by c-erbB2. (A) Effects on adhesion to microtiter wells coated with collagen I (0.5 μg/well) of blocking antibodies against integrin subunits α1 (FB12), α2 (P1E6), α3 (P1B5), and β1 (P5D2). Antibodies were diluted as indicated, with a starting concentration of 10 μg/ml or undiluted hybridoma supernatant in the case of P5D2. (B) NGF-induced c-erbB2 homodimer signaling is not associated with surface downregulation of integrins α2 or β1. HB2/tnz34 cells in suspension were treated with or without 50 ng/ml NGF for 1 h before flow cytometry analysis using antibodies against integrin subunits. Dashed lines show control samples stained with FITC-labeled secondary antibody only. (C) Antibody-mediated activation of integrin α2β1 restores adhesion in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells. Cells were pretreated for 1h with the antibodies HAS4 (10 μg/ml), TS2/16 (0.5 μg/ml), or JBS2 (10 μg/ml), which activate integrin α2, β1, or α2β1, respectively, before incubation with or without 50 ng/ml NGF as indicated. (D) Effect of cytochalasin D treatment on adhesion of HB2/tnz34 cells to collagen. Cells were pretreated for 1 h with or without 10 nM cytochalasin D followed by treatment with NGF (50 ng/ml), TS2/16 (0.5 μg/ml), or neither for 1 h.

Our results indicated that the ability of integrin α2β1 to bind collagen was suppressed by c-erbB2 homodimer signaling. One possible mechanism for this event would be that c-erbB2 signaling causes a depletion of the integrin from the cell surface. To test this hypothesis, HB2/tnz34 cells were left in suspension for 1 h with or without NGF (conditions identical to those used in the adhesion assays) and then subjected to FACS analysis using antibodies against the α2 and β1 subunits. The results showed that no change in surface expression of these integrin subunits could be detected with NGF treatment (Figure 3B). It thus appeared that the effect of c-erbB2 on the α2β1 integrin was mediated by a modulation of integrin function rather than abundance. We assessed this possibility by treating the cells with the mAbs TS2/16, which activates the binding capacity of β1 integrins, and JBS2, which specifically stimulates integrin α2β1, before NGF treatment and adhesion assay. We found that both antibodies almost completely restored adhesion in the presence of c-erbB2 signaling (Figure 3C). The anti-α2 antibody HAS4 (Tenchini et al., 1993), for which a stimulatory role also has been suggested (Alford et al., 1998; Baeckström et al., 2000), had a similar effect. We therefore concluded that the major cause of c-erbB2–induced suppression of adhesion to collagen is functional inhibition of integrin α2β1.

Although the function of the integrin-stimulating antibodies is generally held to be caused by induction of conformational changes in the extracellular domain, it cannot be concluded that c-erbB2–induced suppression of adhesion also affects integrin conformation. Another possible mode of integrin suppression is by weakening integrin–cytoskeleton interactions, which are essential for integrin function. To analyze this possibity, we treated HB2/tnz34 cells with the actin-depolymerizing drug cytochalasin D. Whereas adhesion was completely abolished at higher concentrations (100 nM, not shown), a concentration of 10 nM caused a suppression of adhesion similar to that with NGF treatment, and addition of NGF to these cells did not significantly affect adhesion further (Figure 3D). The TS2/16 antibody, however, could still restore adhesion in cytochalasin d–treated cells. These data indicate that the effect of c-erbB2 on integrin function is dependent on the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton and suggest that the integrin–cytoskeleton linkage may be affected by c-erbB2.

c-erbB2–induced Integrin Inhibition Is Dependent on the MEK1/2 MAP Kinase Pathway

Next, we wished to determine the intracellular signaling pathways involved in mediating the antagonistic effects of c-erbB2 signaling on the function of integrin α2β1. We reasoned that if such a signaling pathway could be blocked, then the trk-neu–transfected cells would adhere normally even upon c-erbB2 homodimer signaling. Furthermore, the importance of the pathways studied for integrin-regulated morphogenesis could also be assessed by comparison with the effects of the same treatment in the spreading assay. Using pharmacological inhibitors and transient transfections, we therefore studied the effects of interference with the function of intracellular signaling enzymes.

Because a Ras/Raf-initiated pathway, leading to the activation of the MAP kinases ERK1/2, has previously been implicated in integrin inactivation (Hughes et al., 1997) and because the EGF receptor family tyrosine kinases are known to activate Ras, it was of interest to study the role of this pathway in c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion and spreading. Using Western blotting with antibodies specific for the activated, phosphorylated state of ERK1/2, we could confirm that this pathway is indeed activated by the c-erbB2 homodimer in HB2/tnz34 cells (Figure 4A). The importance of ERK activation in integrin regulation by c-erbB2 was then analyzed by treating HB2/tnz34 cells with NGF in combination with PD98059, which inhibits the activation of the MAP kinase kinases MEK1 and MEK2, immediate upstream activators of ERK1/2. As shown in Figure 4B, treatment with PD98059 resulted in restoration of adhesion and spreading in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells. These results indicate that activation of a MEK-ERK pathway is required for inactivation of integrin α2β1 by c-erbB2 and suggest that this effect is important for disruption of spreading morphogenesis.

Figure 4.

c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation is dependent on MAP kinase activation. (A) c-erbB2 homodimerization induces activating phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 MAP kinases. Serum-starved cells were preincubated for 1 h with or without PD98059 (30 μM), which inhibits the ERK activators MEK1/2 and then stimulated for another hour with NGF (50 ng/ml). Cell lysates were analyzed in Western blots with antibodies against total ERK1/2 or ERK1/2 phosphorylated at the activating sites Thr-202 and Tyr-204. (B) PD98059 restores adhesion and spreading in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells. PD98059 (30 μM) was added to cells 1 h before NGF treatment (adhesion assay) or together with NGF (spreading assay) as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Adhesion assay data show averages and SDs of at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate; spreading data show representative averages of duplicate samples from experiments performed at least three times.

Activation of Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase–Dependent Pathway(s) Is Also Required for c-erbB2–induced Integrin Inactivation

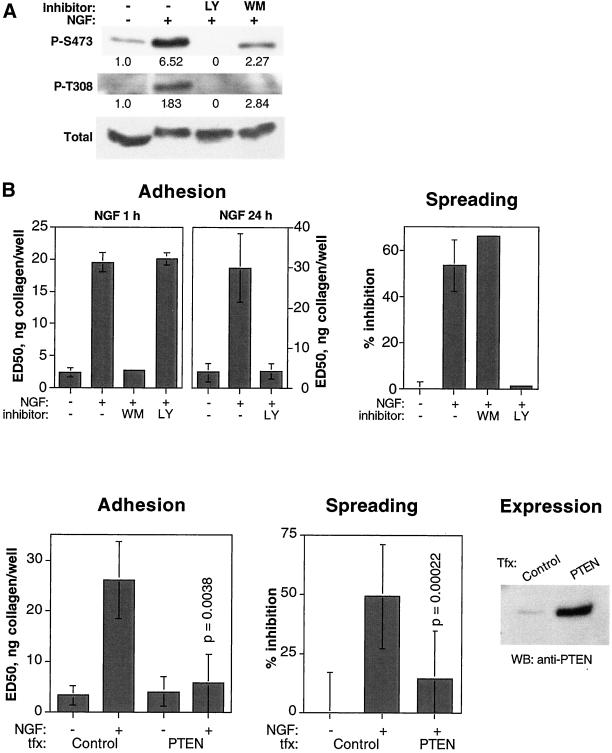

Although our results supported the notion that the MEK1/2 pathway is required for integrin inactivation, they did not exclude the possibility that other intracellular signals are equally important for this process. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) is another major effector of receptor tyrosine kinases that regulates a number of pathways of crucial importance to a variety of cellular functions. We could readily detect c-erbB2–induced activation of PI3K in HB2/tnz34 cells by measuring the activating phosphorylations at Thr308 and Ser473 in PKB, a well-established PI3K effector, on NGF treatment (Figure 5A). The PI3K dependence of this event was verified by the abrogating effect on PKB phosphorylation of treatment with LY294002 and wortmannin, two pharmacological PI3K inhibitors. To investigate a possible role of PI3K in integrin regulation by c-erbB2, we used these two PI3K inhibitors in our adhesion and spreading assays. Although wortmannin completely restored primary adhesion to collagen in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells (Figure 5B), LY294002 was without effect under standard conditions for this assay (1 h of inhibitor treatment followed by addition of NGF). Intriguingly, spreading of these cells was restored by LY294002 but not wortmannin. Wortmannin is known to be more unstable than LY294002; however, repeated additions of fresh wortmannin during the 24-h incubation with NGF also failed to restore spreading. We asked ourselves whether the difference in response to LY294002 between the spreading and adhesion readouts could be a result of the difference in the duration of the assays (2 h in adhesion assay vs. 24 h in spreading assays). We therefore studied the influence of LY294002 on the adhesion of cells that had been pretreated with NGF for 24 h. Under these conditions, adhesion was indeed restored (Figure 5B). It thus appears that the sensitivity to LY294002 of the integrin-regulating PI3K response varies with the duration of the c-erbB2 signaling. Long-term NGF treatment, however, did not change the effect of LY294002 or wortmannin on NGF-induced activating PKB phosphorylation compared with the short-term conditions shown in Figure 5A (data not shown).

Figure 5.

c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation is mediated by PI3K. (A) Activation of PI3K by c-erbB2 and inhibition by LY294002 and wortmannin as detected by changes in phosphorylation of PKB. Serum-starved cells were pretreated for 1 h with or without inhibitors followed by incubation for another hour with or without NGF. Cell lysates were analyzed for PKB phosphorylation in Western blots using antibody against PKB or antisera specific for PKB phosphorylated at Thr-308 or Ser-473. The numbers below the P-S473 and P-T308 blots show band intensities compared with NGF-untreated controls and normalized with respect to total PKB band intensity. (B) Influence of PI3K inhibitors LY294002 (LY, 30 μM) and wortmannin (WM; adhesion, 25 nM; spreading, 100 nM) on NGF-induced inhibition of spreading and adhesion of HB2/tnz34 cells. In the adhesion assay, the cells were incubated with NGF for 1 or 24 h as indicated. Under the 24-h conditions, the cells were adherent during NGF treatment before detachment and incubation with both NGF and LY294002 for 1 h. Adhesion assay data show averages and SDs of at least two separate experiments performed in duplicate; spreading data show representative averages of duplicate samples from experiments performed at least three times. (C) Influence of PTEN transfection on c-erbB2–induced suppression of adhesion and spreading. HB2/tnz34 cells were transiently cotransfected with PTEN and a LacZ expression vector. Staining with ONPG (adhesion assay) or X-gal (spreading assay) was used to identify transfected cells. Control transfections were per-formed with LacZ plasmid only. In the adhesion assays, the absorbance readouts were normalized with respect to transfection efficiency as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The data show averages and SDs derived from three (adhesion) or five (spreading) separate experiments performed in duplicate or more. The p values show the result of a comparison to NGF-treated control cells using Student's paired t test. Verification of the expression of transfected PTEN using a PTEN-specific antiserum in Western blot is also shown.

As an alternative to the PI3K inhibitor treatments, we also examined the effect of overexpressing the phosphoinositide-3-phosphatase PTEN, which antagonizes PI3K function by lowering the intracellular levels of 3-phosphoinositides. A wild-type PTEN expression plasmid was introduced into HB2/tnz34 cells in transient transfections, in which cotransfected LacZ was used as a reporter gene to identify transfected cells. The cells were then used in adhesion and spreading assays, in which the adhesive properties of the transfected cells could be selectively evaluated after exposure to chromogenic LacZ substrates (see MATERIALS AND METHODS for details). Using this technique, we found that PTEN could restore integrin function in both spreading and adhesion assays (Figure 5C). We therefore tentatively concluded that PI3K is required for integrin inactivation by c-erbB2 but that the dependence is likely to be complex, with different downstream components showing differences in influence on adhesion, sensitivity to inhibitors, and dependence on signal duration.

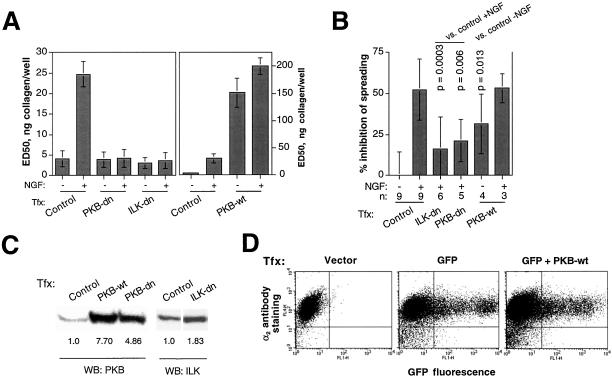

PKB and Integrin-Linked Kinase Mediate Integrin Regulation Downstream of PI3K

To resolve the question of the possible importance of PI3K-dependent pathways in c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation, we sought to interfere with the function of individual PI3K effectors and study the resulting effect on adhesion and spreading. We had already established that PKB was activated by c-erbB2 in our system (Figure 5A). PKB is a major mediator of PI3K signaling, which has been implicated in diverse biological phenomena, such as metabolic control, protection against apoptosis, and cell motility (Chan et al., 1999; Kim, 2001). In addition to its requirement for direct binding to 3-phosphoinositides, activation of PKB is also dependent on the upstream activators phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK-1) and, interestingly, ILK, a putative serine/threonine kinase that also binds the β1 integrin, promoting its phosphorylation and functional downregulation (Hannigan et al., 1996). To elucidate whether c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation is dependent on PKB and/or ILK, we transiently transfected wild-type and dominant-negative PKB and ILK constructs into HB2/tnz34 cells and studied the behavior of transfected cells in adhesion and spreading assays. The results of these assays showed a striking restoration of adhesion and spreading by dominant-negative PKB and ILK in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells (Figure 6, A and B). Indeed, overexpression of wild-type PKB was sufficient to suppress adhesion in the absence of NGF. In contrast, wild-type ILK transfection did not alter adhesion or spreading (data not shown).

Figure 6.

c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation is dependent on ILK and PKB. cDNA constructs coding for wild-type (wt) or dominant-negative (dn) PKB or ILK were transiently cotransfected into HB2/tnz34 cells together with a LacZ reporter plasmid before adhesion (A) or spreading (B) was analyzed in the absence or presence of NGF. Staining with ONPG (adhesion assay) or X-gal (spreading assay) was used to identify transfected cells. Control transfections were performed with LacZ plasmid only. In the adhesion assays, the absorbance readouts were normalized with respect to transfection efficiency as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Note the difference in y-axis scale between the left and right halves of A. The p values in B refer to a comparison with NGF-treated or untreated control cells as indi-cated by Student's paired t test. Unless the number of experiments is explicitly stated (n), the data show averages and SDs of at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate. (C) Verification of the expression of transfected PKB or ILK constructs by Western blot (WB). The numbers below the PKB and ILK blots show band intensities relative to endogenous protein bands in control transfections. (D) PKB-induced suppression of adhesion and spreading is not caused by decreased surface expression of integrin α2β1. Cells were cotransfected with PKB and a GFP reporter plasmid and stained with mAbs against the α2 or β1 subunits followed by biotinylated antimouse antibody and allophycocyanin-labeled streptavidin. Transfection efficiency was monitored as GFP fluorescence in channel FL-1, and integrin antibody staining (only α2 shown) was measured in the FL-4 channel.

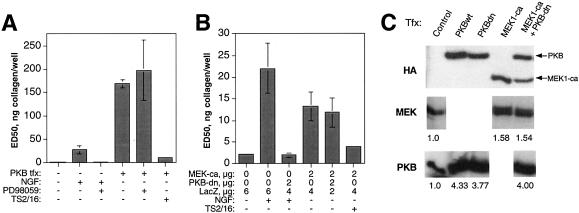

Because the adhesion-suppressing response of PKB transfection (measured as ED50 value) was >5 times stronger than that of NGF-induced c-erbB2 signaling and because the duration of elevated PKB signaling by necessity was much longer after PKB transfection than the standard 1-h NGF treatment, we asked whether some mechanism other than integrin inactivation might be involved in this effect. We therefore analyzed the effect of PKB overexpression on the levels of integrin α2 and β1 surface expression in flow cytometry, using coexpressed GFP as a reporter for transfection. In this assay, integrin levels were unaffected by PKB (shown for α2 in Figure 6D; identical results were obtained in similar experiments in which the other constructs used in this study were expressed; data not shown). Moreover, when PKB-transfected cells were treated with the integrin-activating antibody TS2/16, adhesion was restored by >95% (see Figure 8A), strongly indicating that integrin inactivation is indeed the major mediator of the antiadhesive effect of PKB. These results demonstrate a novel role for PKB as a potent regulator of the functional status of integrins and as a mediator of the antiadhesive and antimorphogenetic effects of strong c-erbB2 homodimer signaling.

Figure 8.

MEK1 overexpression combined with PKB inhibition and vice versa are both sufficient to inhibit adhesion to collagen without concomitant c-erbB2 signaling. (A) HB2/tnz34 cells transfected (tfx) with wild-type PKB and a LacZ reporter plasmid were analyzed in adhesion assay with or without inhibition of MEK1/2 by treatment with 30 μM PD98059. Results of NGF treatment with or without concomitant treatment with PD98059 are included as a positive control for the effect of PD98059. (B) Cells were transfected with constitutively active MEK1 (MEK1-ca) and a LacZ reporter plasmid with or without cotransfection with a dominant-negative PKB (PKB-dn) expression vector using the plasmid DNA amounts indicated. Results of NGF treatment with or without concomitant PKB-dn transfection are included as a positive control for the effect of PKB-dn. In both panels, restoration of adhesion by treatment with the integrin β1–activating mAb TS2/16 is also shown to confirm that suppression of adhesion caused by PKB or MEK1 overexpression is a result of integrin inactivation. Staining with ONPG was used to identify adhered transfected cells. Control transfections were performed with LacZ plasmid only. The absorbance readouts were normalized with respect to transfection efficiency as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (C) Verification of the expression of transfected wild-type (wt) or dominant-negative (dn) PKB or constitutively active MEK1 (all HA-tagged) using antibodies specific for PKB, MEK1, or the HA epitope in Western blot. The numbers below the MEK and PKB blots show band intensities relative to endogenous protein bands in control transfections. Note that the transfected PKB and MEK appear slightly larger than the endogenous species because of the presence of the HA epitope.

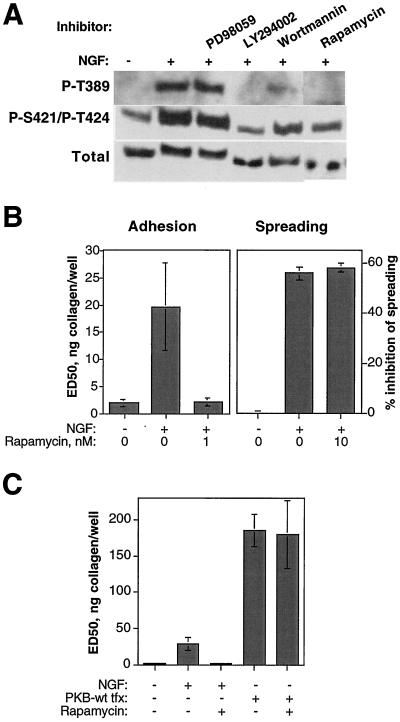

c-erbB2 Activates a PKB-Independent, Rapamycin-Sensitive Pathway That Is Required for Inhibition of Adhesion but Not Spreading

The complex response of c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation to PI3K inhibitors prompted us to search for additional PI3K effectors that might mediate this effect apart from, or perhaps as an effector of, PKB. Because treatment with inhibitors against protein kinases A or C (which both are activated by PDK-1; Cantrell, 2001) was unable to restore spreading or adhesion in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells (Table 1), these signaling molecules are unlikely to play an important role in integrin regulation by c-erbB2.

Table 1.

Protein kinase inhibitors used without effect on NGF-induced suppression of spreading and adhesion on collagen in HB2/tnz34 cells

| Inhibitor | Target | Reported IC50, nMa | Highest concentration used without effect, nM |

|---|---|---|---|

| H-89 | PKA | 48 | 500 |

| Chelerythrine chloride | PKC | 660 | 5000 |

| Calphostin C | PKC | 50 | 200 |

| Bisindolylmaleimide I | PKC | 10 | 1000 |

Values according to supplier's data.

The p70 S6 kinase is also reported to be indirectly activated by PI3K in a PDK-1– and possibly also PKB-dependent manner (Dufner and Thomas, 1999). Activating phosphorylation of S6K was found to be induced by c-erbB2 homodimer signaling in a manner sensitive to inhibition of PI3K but not of MEK (Figure 7A). We therefore analyzed the influence on c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation of rapamycin, which inhibits activation of S6K by the upstream kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). As shown in Figure 7B, rapamycin potently restored primary adhesion, but not spreading, in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells. S6K or some other mTOR effector is therefore likely to be a necessary mediator of the antiadhesive effect of PI3K. The mTOR/S6K pathway has been implicated primarily in selective regulation of protein synthesis (Gingras et al., 2001). Because c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation was shown to be independent of protein synthesis (Figure 2D), our results suggest a novel mode of function for S6K, or some other mTOR effector, in integrin regulation.

Figure 7.

The mTOR-S6K pathway is activated by c-erbB2, and mTOR inhibition reverses suppression of adhesion by c-erbB2 in a PKB-independent manner. (A) c-erbB2 homodimer signaling induces activating phosphorylation of p70 S6K in HB2/tnz34 cells. Serum-starved cells were pretreated for 1 h with or without rapamycin (1 nM), which inhibits the S6K activator mTOR, or the PI3K inhibitors LY294002 (30 μM) or wortmannin (100 nM) or the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (30 μM) before incubation for another hour with or without NGF (50 ng/ml). Cell lysates were analyzed in Western blot for S6K or phosphorylation at the activating sites Thr389 and Ser421/Thr424 in S6K with antibody against S6K and phosphorylation state–specific antisera, respectively. (B) c-erbB2–induced suppression of adhesion, but not spreading, is rapamycin-sensitive. HB2/tnz34 cells were treated with NGF, alone or in combination with rapamycin at the concentrations indicated, in adhesion and spreading assays. (C) The rapamycin-sensitive mechanism of integrin inactivation is not acting downstream of PKB. Adhesion to collagen was analyzed in control or PKB-transfected (tfx; wt, wild-type) HB2/tnz34 cells in the presence or absence of 1 nM rapamycin. Cells were cotransfected with LacZ, and staining with ONPG was used to identify adhered transfected cells. Control transfections were performed with LacZ plasmid only. The absorbance readouts were normalized with respect to transfection efficiency as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Adhesion assay data show averages and SDs of at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate; spreading data show representative averages of duplicate samples from experiments performed at least three times. Note the difference in y-axis scale between the adhesion graphs in B and C.

Some studies have suggested a role for PKB in activation of the mTOR-S6K pathway, although this connection has been disputed (Dufner and Thomas, 1999). We analyzed a possible link between PKB and mTOR-S6K in c-erbB2–induced integrin regulation by treating PKB-transfected HB2/tnz34 cells with rapamycin in adhesion assays. As shown in Figure 7C, the suppression of adhesion caused by PKB was completely unaffected by rapamycin treatment, indicating that PKB and the rapamycin-sensitive pathway act as parallel and independent mediators of the integrin-inactivating effect of PI3K. This conclusion was further strengthened by the observed lack of S6K activation on PKB transfection (data not shown).

The MEK and PKB Pathways Appear to Regulate Integrin Activity via Common Target(s)

The reversal of c-erbB2–induced disruption of adhesion and spreading observed when the function of either MEK or PKB was inhibited strongly indicated that both signaling pathways were required for integrin inactivation by c-erbB2. It was therefore somewhat surprising that suppression of integrin function could be achieved solely by overexpression of PKB in the absence of c-erbB2 homodimer signaling (Figure 6A). First, to test the possibility that PI3K or PKB could activate MEK, we searched for evidence of cross talk between these pathways by using inhibitor treatments, transfections, or combinations of both. As shown in Table 2, no manipulation of the PI3K or PKB pathways had any effect on ERK phosphorylation, and conversely, neither activated MEK1 nor the MEK inhibitor PD98059 could influence the activation status of PKB (in addition, we showed that the rapamycin-sensitive pathway also is independent of the MEK pathway). These results clearly indicated that the MEK and PKB pathways were acting in a parallel manner. Another possible explanation for the apparent MEK independence of the effect of PKB on adhesion would be that the constitutive MEK activity in unstimulated cells was sufficient to support integrin inactivation when combined with increased PKB activity. However, when we inhibited MEK signaling by treatment with PD98059, the integrin-inactivating effect of PKB overexpression was not diminished (Figure 8A). Thus, it appears that PKB, when expressed at a sufficiently high level, can mediate integrin inactivation in the absence of MEK activity. This in turn suggests that the MEK and PKB pathways may use common downstream targets for regulating integrin activity. Such a hypothesis would predict that stimulation of the MEK pathway in the absence of PKB signaling also would be sufficient for integrin inactivation. As shown in Figure 8B, transient transfection with constitutively active MEK1 was indeed capable of suppressing adhesion in the absence of NGF-induced c-erbB2 homodimer signaling, an effect that was not perturbed by cotransfection with dominant-negative PKB. The suppressive effect of MEK transfection appeared considerably weaker than that induced by PKB; however, this discrepancy may be explained by the higher degree of overexpression of PKB compared with MEK (Figure 8C), although it should be kept in mind that the MEK used was a constitutively active mutant, whereas PKB was wild-type. We also confirmed that the adhesion-suppressing effect of MEK1 transfection could be reversed by integrin activation mediated by treatment with the TS2/16 mAb (Figure 8B). It therefore appears that overexpression of either PKB or MEK1 overrides the requirement for activation of both pathways to achieve integrin inactivation. These results are thus in accordance with the hypothesis that the MEK and PKB pathways may use common downstream effectors for downregulation of integrin function.

Table 2.

Summary of negative results indicating that the MEK, PKB, and rapamycin-sensitive pathways operate in a parallel fashion downstream of c-erbB2 in HB2/tnz34 cells

| Treatment | Without effect on | Compared to treatment |

|---|---|---|

| NGF + LY294002 (30 μM) | ERK phosphorylation | NGF |

| NGF + wortmannin (100 nM) | ERK phosphorylation | NGF |

| NGF + rapamycin (1 nM) | ERK phosphorylation | NGF |

| PKB transfection | ERK phosphorylation | Control transfection |

| NGF + PD98059 (30 μM) | PKB phosphorylation | NGF |

| NGF + rapamycin (1 nM) | PKB phosphorylation | NGF |

| MEK1-ca transfection | PKB phosphorylation | Control transfection |

| MEK1-ca transfection | S6K phosphorylation | Control transfection |

| PKB transfection | S6K phosphorylation | Control transfection |

NGF concentration: 50 ng/ml.

DISCUSSION

The present study was prompted by the profound effect of intense c-erbB2 homodimer signaling on morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells in three-dimensional collagen culture and its reversal by integrin activation observed previously (Baeckström et al., 2000). Here, we have attempted to elucidate the intracellular events that mediate this morphogenetic effect. Adhesion assays have been used to study the regulation of integrin function without interference from other phenomena, whereas spreading assays were used as a simplified indicator of morphogenesis. Our findings can be summarized as follows.

Integrin Function Is Negatively Affected by c-erbB2

This was suspected from the earlier finding that the inhibition of morphogenesis in collagen caused by c-erbB2 homodimer signaling could be reversed by antibodies that activate α2 or β1 integrins (Baeckström et al., 2000). However, the present study provides direct evidence that c-erbB2 inhibits integrin-dependent matrix adhesion. Specifically, we have shown that primary adhesion to collagen of HB2/tnz34 cells is dependent on integrin β1 and α2 subunits and that c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion can be completely reversed by mAbs that induce an active conformation in the α2β1 integrin. Moreover, the restoration of adhesion caused by inhibitor treatments (discussed below) was consistently abrogated by incubation with an α2-blocking antibody, and in no case did these inhibitors cause increased surface expression of integrin α2 or β1 (data not shown). Together, these findings strongly indicate that the function of integrin α2β1 is suppressed by c-erbB2 and that the manipulations that restore adhesion do so by relieving this suppression.

Integrin function can be regulated by changing integrin extracellular conformation, clustering of integrins at the cell surface, or integrin–cytoskeleton attachment. The present study cannot conclusively identify at what level(s) the antiadhesive signal from c-erbB2 acts. However, because no effect of NGF was seen in the cytochalasin d-treated cells (Figure 3D), it is likely that a cytoskeleton-dependent mechanism plays an important role. Detection of changes in β1 extracellular conformation using activation epitope–specific antibodies has been attempted (data not shown), but although a reproducibly suppressive effect of NGF could be seen, the interpretation of these results was hampered by the very weak binding of the conformation-specific antibodies to untreated as well as manganese-activated cells. It is possible that the regulation of β1 integrin activity in epithelial cells involves more subtle changes in extracellular conformation.

The MEK-ERK and PI3K Pathways Are Both Required for c-erbB2–induced Integrin Inhibition

Our data strongly indicate an important role for the Raf-MEK pathway, because PD98059, a substance that inhibits the activation of MEK1/2 by Raf, potently restored spreading and adhesion in NGF-treated HB2/tnz34 cells (Figure 2). Hughes et al. (1997) showed the potential of this pathway to inhibit integrin activation. Apart from confirming this previous observation, we have demonstrated the relevance of the integrin-inactivating capacity of the ERK pathway in a wider context, both with respect to its role as a mediator of c-erbB2 signaling to the α2β1 integrin and with respect to its function in disruption of morphogenesis. The integrin-inactivating downstream effector(s) of ERK are still not characterized, but both our data and those of Hughes et al. clearly indicate that regulation of transcription or protein synthesis is not involved. We have also established that the effect of PD98059 (as well as that of the other adhesion-restoring inhibitors wortmannin and rapamycin) was insensitive to cycloheximide treatment (data not shown). As will be discussed below, our data suggest that the ERK signal and those of other pathways may target a common integrin-regulating effector.

In our initial characterization of the possible PI3K dependence of c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion and spreading using the two widely used pharmacological PI3K inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin, the paradoxical result was obtained that adhesion was restored by wortmannin but not LY294002, whereas the reverse was the case for cell spreading (Figure 5B). In the case of LY294002, a time-dependent effect is suggested by the observation that after prolonged (24 h) c-erbB2 activation, the adhesion-suppressing response of HB2/tnz34 cells becomes sensitive to LY294002, although the duration of the inhibitor treatment is not changed. Because overexpression of the 3-phosphoinositide phosphatase PTEN as well as inhibition of at least two different PI3K effectors also restored integrin function (see below), we feel that it is safe to conclude that c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation indeed is PI3K-dependent. As a tentative explanation for the observed difference in response to PI3K inhibitors, one may speculate that PI3K elicits integrin-activating as well as integrin-inactivating mechanisms and that the balance between opposing effects on integrin function downstream of PI3K may be sensitive to how PI3K is inhibited and/or to the duration of the PI3K signal. The slight difference in inhibition efficiency beteween LY294002 and wortmannin seen in Figure 5A may be of importance in this context. Different PI3K effectors have previously been reported to respond differently to LY294002 compared with wortmannin (Adi et al., 2001). Although wortmannin is known to be capable of inhibiting myosin light chain kinase (Nakanishi et al., 1992) and mTOR (Gingras et al., 2001) in addition to PI3K, these kinases are not likely to be direct mediators of the effect of wortmannin in our experiments, because the concentrations required for their inhibition (∼200 nM) are far higher than the 25 nM used in our adhesion assays.

Although PI3K has often been implicated in downstream events after integrin–ligand binding, only a small number of reports describe a role for PI3K in the regulation of integrin function (e.g., Shimizu et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1996); moreover, in those studies, PI3K was found to enhance integrin-mediated matrix adhesion. Likewise, the morphogenetic effects of PTEN overexpression were described by Tamura et al. (1998) as antagonistic to spreading. These observations are thus in apparent conflict with our data, which indicate that integrin function is inhibited by PI3K and restored by PTEN. It should be kept in mind, however, that whereas the cells used by Tamura et al. were mesenchymal in origin and Shimizu et al. and Zhang et al. studied hematopoietic cells, our system consists of epithelial cells. Regulation of matrix adhesion is likely to be highly cell-type specific, given the radically different adhesion requirements of different cell types. It should also be noted that our experiments have neither addressed nor elucidated the possibility of an active role for PTEN in c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation.

Downstream of PI3K, ILK, PKB, and a Rapamycin-Sensitive Pathway Mediate Integrin Inactivation Initiated by c-erbB2

A major novel finding in this study is the crucial role of PKB in mediating the integrin-inactivating effects of c-erbB2 demonstrated by the restoration of both adhesion and spreading on transfection with dominant negative forms of PKB or the PKB coactivator ILK (Figure 6). Like PI3K, PKB has often been implicated in events after integrin engagement (outside-in signaling; e.g. Khwaja et al., 1997); however, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a crucial role for PKB in cellular regulation of integrin function (inside-out signaling). Interestingly, PKB has recently been implicated in cancer cell motility and invasion (Kim, 2001). This effect was partly explained by increased metalloproteinase production, and no changes in primary adhesion to collagen were observed on PKB transfection. However, only one relatively high collagen coating concentration was used in the adhesion assays and, as shown in the present study, suppression of adhesion caused by integrin inactivation may not be evident under conditions in which the supply of matrix is not limiting. Another recent report (Kirk et al., 2000) demonstrated phosphorylation of integrin β3 at a cytoplasmic threonine by PKB; however, the report did not investigate possible changes in the functional status of the integrin after this event. The threonine residue in question is situated in a region that is conserved between β integrins, and it is a possibility worth exploring that a similar event is taking place in β1 integrins on c-erbB2–induced activation of PKB and that this contributes to integrin inactivation.

Our data also identify ILK as a necessary mediator of the integrin-inactivating effects of c-erbB2. Although ILK was initially identified as a molecule that binds, phosphorylates, and inactivates integrin β1 (Hannigan et al., 1996), very little is known about this aspect of ILK function. Instead, the bulk of our present knowledge about ILK pertains to its role in activating downstream effectors such as PKB, glycogen synthase kinase-3, and the β-catenin pathway (Delcommenne et al., 1998; Tan et al., 2001). However, in HB2/tnz34 cells, neither downregulation of adhesion nor PKB phosphorylation could be observed after overexpression of either wild-type ILK or a putatively activated S343D mutant (Lynch et al., 1999) (data not shown). It is therefore possible that these effects of ILK are cell-type dependent or that higher expression levels of ILK than those achieved in the present study are necessary to suppress adhesion and/or cause PKB phosphorylation in HB2/tnz34 cells. These observations, and the finding that PKB is capable of causing integrin inactivation, raise the intriguing possibility that downregulation of matrix adhesion by ILK (Hannigan et al., 1996) is mediated by PKB. One may speculate that ILK recruits PKB to the vicinity of integrin cytoplasmic domains, in which PKB becomes activated and phosphorylates the integrins or associated proteins necessary for integrin function. Because ILK has been shown to have a vital function in Drosophila that is independent of its kinase activity (Zervas et al., 2001), one may speculate that ILK regulates integrin function both as a kinase-independent adapter molecule and, perhaps more subtly, as an integrin-proximal activator of PKB.

The surprising result that c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion can be reversed by treatment with rapamycin indicates a previously unknown function for the protein kinase mTOR, which has been known primarily as a specific regulator of protein synthesis (Gingras et al., 2001). The best-described effector of mTOR is S6K, a protein kinase known to phosphorylate the S6 ribosomal protein, thereby mediating a major part of the translation-regulating function of mTOR (Proud, 1996). Neither kinase has earlier been implicated in regulation of cell adhesion. Because S6K but not mTOR is reported to be dependent on PI3K for activation (Gingras et al., 2001), it is possible that the observed rapamycin-sensitive suppression of adhesion is mediated by activation of S6K by PI3K and that mTOR itself plays a permissive role. On the basis of the present data, however, it is not possible to decide whether it is S6K or some other mTOR effector that is mediating integrin inhibition. In either case, this pathway is likely to be acting in parallel with and not downstream of PKB, because rapamycin was unable to restore the suppression of adhesion caused by transfection with wild-type PKB; in addition, PKB overexpression failed to induce activating phosphorylation of S6K (data not shown). In contrast to these data, an interesting recent report (Neshat et al., 2001) found that a rapamycin analog could antagonize growth of cells expressing activated PKB (or lacking PTEN). However, that study did not directly analyze the influence of PKB signaling on S6K activity.

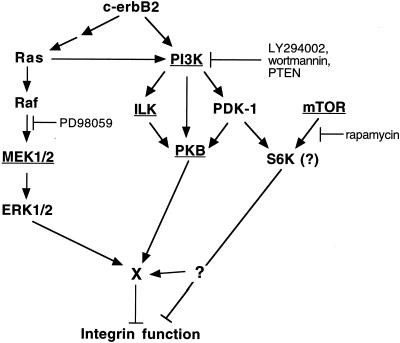

The MEK and PKB Pathways May Use Common Downstream Mediators to Inhibit Integrin Function

Our results regarding the MEK and PKB dependence of c-erbB2–induced integrin inactivation presented us with an apparent paradox: on one hand, the observation that inhibition of either PKB or MEK is sufficient to restore integrin function in the presence of c-erbB2 signaling strongly indicated that both pathways are necessary mediators of the antiadhesive effect of c-erbB2. On the other hand, we had found that overexpression of either wild-type PKB or constitutively active MEK was sufficient to inhibit integrin function in the absence of c-erbB2 signaling. Even when inhibiting constitutive MEK signaling in PKB-transfected cells or vice versa, we failed to observe interdependence between the two pathways in suppression of adhesion (Figure 8), suggesting that MEK and PKB use a common downstream effector to exert their antiadhesive function (Figure 9). One possible explanation for this apparent contradiction is that when PKB is strongly overexpressed, the putative common effector is activated to a sufficient degree to make MEK signaling redundant (and vice versa); however, at the level of signaling achieved by trk-neu homodimerization, both MEK and PKB are necessary to reach the signaling intensity necessary for integrin inactivation. Identification of the putative common effector(s) is evidently an urgent task for future research.

Figure 9.

Schematic overview showing an interpretation of the results of the present study. Proteins whose function was found to be essential for c-erbB2–induced inhibition of adhesion and/or spreading are underlined. Note that the involvement of S6K in integrin inactivation is speculative. The molecule X is one or more putative integrin-regulating effector(s) common to the MEK and PKB pathways. See DISCUSSION for details.

When the influences of different signaling molecules mediating the effects of c-erbB2 are summarized, there is a striking similarity between the responses in adhesion and spreading assays: with the exception of the rapamycin-sensitive effector, all pathways that were shown to be important for adhesion also affected spreading. This correlation suggests that the mechanisms that govern the rapid modulation of integrin activation status also are critical to the longer-term effects of c-erbB2 on cellular morphogenesis. Such a conclusion strengthens the concept of a crucial role for integrin regulation in c-erbB2–induced conversion of cellular phenotype.

PKB has recently emerged as an important mediator of a variety of cancer-associated effects of c-erbB2 signaling, including desensitization to tumor-preventing mechanisms, such as cell cycle arrest by p21WAF (Zhou et al., 2001), hormone dependence (Wen et al., 2000), and tumor necrosis factor–induced apoptosis (Zhou et al., 2000). Because impairment of α2β1 integrin–mediated adhesion has been strongly associated with breast cancer progression (Zutter et al., 1990, 1995), the results of the present study may present yet another aspect of PKB function in c-erbB2–induced carcinogenesis. The influence of integrin inactivation on the emerging carcinoma cell is likely to include increased motility and invasiveness, facilitating tumor cell dissemination and metastasis. This process would be further enhanced by the recently identified PKB-mediated matrix metalloproteinase production (Kim, 2001). The versatility of PKB in mediating the carcinogenic effects of c-erbB2 makes this kinase an interesting target for novel strategies in cancer treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Ian Hiles, Brian Hemmings, Ramon Parsons, and Pär Gerwins for generously providing expression plasmids; Dr. Fiona Watt for the gift of the HAS4 antibody; and Dr. Staffan Johansson for critical reading of the manuscript. The P5D2 hybridoma developed by E. A. Wayner was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa. This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Fund (grant no. 99 3317), Assar Gabrielsson's Fund, the Lars Hierta Memorial Fund, Magn. Bergvall's Foundation, Adlerbert's Research Foundation, and the Swedish Society of Medicine.

Abbreviations used:

- ERK

extracellular-regulated kinase

- ILK

integrin-linked kinase

- MEK

MAP ERK kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- ONPG

o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-(3)-kinase

- PDK-1

phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1

- PKB

protein kinase B

- S6K

p70 S6 kinase

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–02–0064. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–02–0064.

REFERENCES

- Adi S, Wu NY, Rosenthal SM. Growth factor-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and p70(S6K) is differentially inhibited by LY294002 and Wortmannin. Endocrinology. 2001;142:498–501. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.8051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford D, Baeckström D, Geyp M, Pitha P, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Integrin-matrix interactions affect the form of the structures developing from human mammary epithelial cells in collagen or fibrin gels. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:531–532. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeckström D, Lu PJ, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Activation of the α2β1 integrin prevents c-erbB2-induced scattering and apoptosis of human mammary epithelial cells in collagen. Oncogene. 2000;19:4592–4603. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky F, Alford D, D'Souza B, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Branching morphogenesis of human mammary epithelial cells in collagen gels. J Cell Sci. 1994a;107:3557–3568. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky F, Wetzels R, Shearer M, Martignone S, Raemakers FCS, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Integrin expression in relation to cell phenotype and malignant change in the human breast. Mol Cell Differentiation. 1994b;2:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell DA. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathways. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1439–1445. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.8.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TO, Rittenhouse SE, Tsichlis PN. AKT/PKB and other D3 phosphoinositide-regulated kinases: kinase activation by phosphoinositide-dependent phosphorylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:965–1014. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza B, Berdichevsky F, Kyprianou N, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Collagen-induced morphogenesis and expression of the α2-integrin subunit is inhibited in c-erbB2-transfected human mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:1797–1806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Potter CR, Schelfhout A-M. The neu-protein and breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 1995;426:107–115. doi: 10.1007/BF00192631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufner A, Thomas G. Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:100–109. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 2001;15:807–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.887201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan GE, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Fitz-Gibbon L, Coppolino MG, Radeva G, Filmus J, Bell JC, Dedhar S. Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new β1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature. 1996;379:91–96. doi: 10.1038/379091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PE, Renshaw MW, Pfaff M, Forsyth J, Keivens VM, Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Suppression of integrin activation: a novel function of a Ras/Raf-initiated MAP kinase pathway. Cell. 1997;88:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81892-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennström S, Warne PH, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:2783–2793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim S, Koh H, Yoon SO, Chung AS, Cho KS, Chung J. Akt/PKB promotes cancer cell invasion via increased motility and metalloproteinase production. FASEB J. 2001;15:1953–1962. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0198com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RI, Sanderson MR, Lerea KM. Threonine phosphorylation of the β3 integrin cytoplasmic tail, at a site recognized by PDK1 and Akt/PKB in vitro, regulates shc binding. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30901–30906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DK, Ellis CA, Edwards PA, Hiles ID. Integrin-linked kinase regulates phosphorylation of serine 473 of protein kinase B by an indirect mechanism. Oncogene. 1999;18:8024–8032. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S, et al. Wortmannin, a microbial product inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2157–2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, Stiles B, Thomas G, Petersen R, Frost P, Gibbons JJ, Wu H, Sawyers CL. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10314–10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages G, Brunet A, L'Allemain G, Pouyssegur J. Constitutive mutant and putative regulatory serine phosphorylation site of mammalian MAP kinase kinase (MEK1) EMBO J. 1994;13:3003–3010. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proud CG. p70 S6 kinase: an enigma with variations. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs M, Weidner KM, Brinkmann V, Walther I, Obermeier A, Ullrich A, Birchmeier W. Motogenic and morphogenic activity of epithelial receptor tyrosine kinases. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1095–1107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.5.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Mobley JL, Finkelstein LD, Chan AS. A role for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the regulation of beta 1 integrin activity by the CD2 antigen. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1867–1880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel PM, Muller WJ. Mutations affecting conserved cysteine residues within the extracellular domain of Neu promote receptor dimerization and activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8878–8883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Gu J, Matsumoto K, Aota S, Parsons R, Yamada KM. Inhibition of cell migration, spreading, and focal adhesions by tumor suppressor PTEN. Science. 1998;280:1614–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C, Costello P, Sanghera J, Dominguez D, Baulida J, de Herreros AG, Dedhar S. Inhibition of integrin linked kinase (ILK) suppresses beta-catenin-Lef/Tcf-dependent transcription and expression of the E-cadherin repressor, snail, in APC-/- human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:133–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenchini ML, Adams JC, Gilberty C, Steel J, Hudson DL, Malcovati M, Watt FM. Evidence against a major role for integrins in calcium-dependent intercellular adhesion of epidermal keratinocytes. Cell Adhes Commun. 1993;1:55–66. doi: 10.3109/15419069309095681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner DB, Liu J, Cohen JA, Williams WV, Greene MI. A point mutation in the neu oncogene mimics ligand induction of receptor aggregation. Nature. 1989;339:230–231. doi: 10.1038/339230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Hu MC, Makino K, Spohn B, Bartholomeusz G, Yan DH, Hung MC. HER-2/neu promotes androgen-independent survival and growth of prostate cancer cells through the Akt pathway. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6841–6845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JM, Rosser MP, Howlett AR, Feldman RI. A cell-based adhesion assay for the characterization of αvβ3 antagonists. In: Howlett A, editor. Integrin Protocols. Vol. 129. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1999. pp. 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas CG, Gregory SL, Brown NH. Drosophila integrin-linked kinase is required at sites of integrin adhesion to link the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1007–1018. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shattil SJ, Cunningham MC, Rittenhouse SE. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma and p85/phosphoinositide 3-kinase in platelets. Relative activation by thrombin receptor or beta-phorbol myristate acetate and roles in promoting the ligand-binding function of alphaIIbbeta3 integrin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6265–6272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BP, Hu MC, Miller SA, Yu Z, Xia W, Lin SY, Hung MC. HER-2/neu blocks tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis via the Akt/NF-kappaB pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8027–8031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BP, Liao Y, Xia W, Spohn B, Lee MH, Hung MC. Cytoplasmic localization of p21Cip1/WAF1 by Akt-induced phosphorylation in HER-2/neu-overexpressing cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:245–252. doi: 10.1038/35060032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zutter MM, Mazoujian G, Santoro SA. Decreased expression of integrin adhesive protein receptors in adenocarcinoma of the breast. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:863–870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zutter MM, Santoro SA, Staatz WD, Tsung YL. Re-expression of the α2β1 integrin abrogates the malignant phenotype of breast carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7411–7415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]