Abstract

A genetic screen for mutations synthetically lethal with fission yeast calcineurin deletion led to the identification of Ypt3, a homolog of mammalian Rab11 GTP-binding protein. A mutant with the temperature-sensitive ypt3-i5 allele showed pleiotropic phenotypes such as defects in cytokinesis, cell wall integrity, and vacuole fusion, and these were exacerbated by FK506-treatment, a specific inhibitor of calcineurin. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Ypt3 showed cytoplasmic staining that was concentrated at growth sites, and this polarized localization required the actin cytoskeleton. It was also detected as a punctate staining in an actin-independent manner. Electron microscopy revealed that ypt3-i5 mutants accumulated aberrant Golgi-like structures and putative post-Golgi vesicles, which increased remarkably at the restrictive temperature. Consistently, the secretion of GFP fused with the pho1+ leader peptide (SPL-GFP) was abolished at the restrictive temperature in ypt3-i5 mutants. FK506-treatment accentuated the accumulation of aberrant Golgi-like structures and caused a significant decrease of SPL-GFP secretion at a permissive temperature. These results suggest that Ypt3 is required at multiple steps of the exocytic pathway and its mutation affects diverse cellular processes and that calcineurin is functionally connected to these cellular processes.

INTRODUCTION

Calcineurin is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine protein phosphatase, consisting of a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit (Klee et al., 1979). In mammalian T cells, calcineurin mediates the production of various cytokines in response to the stimulation of T-cell receptors. The immunosuppressive drugs, cyclosporin A and FK506, block the activation of human T cells by specifically inactivating calcineurin (Liu et al., 1991a). Calcineurin may have additional functions in other cell types, and loss of these functions may contribute to the side effects of these drugs, which include nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and osteoporosis. A better understanding of the biological roles of calcineurin in different cell types may promote the development of improved strategies for immunosuppression.

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, calcineurin-deficient strains exhibit normal growth under standard conditions (Cyert et al., 1991; Liu et al., 1991b). However, calcineurin function is required for cell viability under some specific growth conditions. Calcineurin mutants deficient for either the catalytic subunits (CNA1/CNA2; Cyert et al. 1991; Liu et al. 1991b) or the regulatory subunit (CNB1; Kuno et al. 1991; Cyert and Thorner 1992) die in the presence of high concentrations of different ions including manganese, sodium, lithium, and hydroxyl ions, but are more tolerant to calcium ion than the wild-type cells (Nakamura et al., 1993; Mendoza et al., 1994; Farcasanu et al., 1995; Pozos et al., 1996). Some of these ion sensitivities are due to a defect in the calcineurin-dependent transcription of several ion transporter genes, including PMR1, PMR2, and PMC1 (Mendoza et al., 1994; Cunningham and Fink, 1996), whose expression are also regulated through the CRZ1/TCN1 transcription factor (Stathopoulos and Cyert, 1997; Matheos et al., 1997). Calcineurin function is also required for cell viability in several mutations including cell wall synthesis genes, VMA genes, and LUV1/RKI1/TCS3/VPS54 gene, which is required to maintain normal vacuolar morphology (Garrett-Engele et al., 1995; Conboy and Cyert, 2000).

We have been studying the calcineurin signal transduction pathway in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe because this system is amenable to genetic analysis and has many advantages in terms of relevance to higher systems. S. pombe has a single gene encoding the catalytic subunit of calcineurin, ppb1+, that is essential for cytokinesis (Yoshida et al., 1994). We have previously shown that fission yeast calcineurin plays an essential role in maintaining chloride ion homeostasis and acts antagonistically with the Pmk1 MAP kinase pathway (Sugiura et al., 1998, 1999). These phenotypes are quite different from those described above for calcineurin-null cells in budding yeast, suggesting that the upstream or downstream signaling events of calcineurin may be distinct in these two distantly related yeasts.

In general, genes showing a synthetic-lethal genetic interaction function in the same pathway or parallel pathways. To screen for new components in the calcineurin signaling pathway, we used a genetic screen to search for mutations which display synthetic lethality with the calcineurin null mutation and identified eight complementation groups its1–8 (its for immunosuppressant- and temperature-sensitive; Zhang et al., 2000; Yada et al., 2001). The characterization of one of these mutants, its5-1/ypt3-i5, is presented here.

We report here that its5+ is allelic to the ypt3+ gene, which encodes a member of the Ypt/Rab family of small GTPases and is most similar to mammalian Rab11 (Urbe et al., 1993) and to S. cerevisiae Ypt31 and Ypt32 (Benli et al., 1996; Jedd et al., 1997). We show evidence that Ypt3 functions at multiple steps of the exocytic pathway, and its mutation affects diverse cellular functions such as cytokinesis, cell wall integrity, and vacuole fusion. This article also provides the first evidence of a genetic and functional interaction in vivo between calcineurin and the Ypt/Rab small GTP-binding protein family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Genetic and Molecular Biology Methods

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The complete medium, YPD, and the minimal medium, EMM, have been described previously (Toda et al., 1996). Standard genetic and recombinant-DNA methods were used accordingly, except where noted (Moreno et al., 1991).

Table 1.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HM123 | h− leu1-32 | Our stock |

| HM528 | h+ his2 | Our stock |

| KP637 | h− leu1-32 cps8-188 | Ishiguro et al., 1996 |

| KP405 | h− leu1-32 cdc3-6 | Balasubramanian et al. (1994) |

| KP409 | h− leu1-32 cdc8-134 | Balasubramanian et al. (1992) |

| 5A/1D | h−/h+ leu1-32/leu1-32 ura4-D18/ura4-D18 his2/+ ade6-M210/ade6-M216 | Our stock |

| KP119 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ppb1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP162 | h− leu1-32 ypt3-i5 | This study |

| KP1245 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-294 | Our stock |

| MTD2 | h+ leu1-32 his2 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 cpy1::ura4+ | Tabuchi et al. (1997) |

| KTP1 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 vps34::ura4+ | Takegawa et al., 1995 |

The its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant was isolated in a screen of cells that had been mutagenized with nitrosoguanidine as described previously (Zhang et al., 2000).

Cloning and Tagging of the its5+/ypt3+ Gene

To clone the its5+ gene, the its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant (KP162) was transformed with an S. pombe genomic DNA library constructed in the vector pDB248 (Beach et al., 1982), and grown at 27°C. Leu+ transformants were replica-plated to YPD plates at 36°C, and plasmid DNA was recovered from 10 transformants that showed plasmid-dependent rescue. These plasmids had identical or overlapping inserts as judged from restriction digests, and all 10 complemented both the immunosuppressant sensitivity and the temperature sensitivity of the its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant.

For ectopic expression of proteins, we used the thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter at various levels of expression (Maundrell, 1993). Expression was repressed by the addition of 4 μg/ml thiamine to EMM and was induced by washing and incubating the cells in EMM lacking thiamine. To express GFP-Ypt3, the complete open reading frame (ORF) of ypt3+ was amplified by PCR and was ligated to the C terminus of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) carrying the S65T mutation (Heim et al., 1995). The GFP-fused gene was subcloned into pREP1, pREP41, or pREP81 vectors to express the gene at various levels. Maximum expression of the fused gene was obtained using pREP1, whereas pREP81, which contained the most attenuated version of the nmt1 promoter (Maundrell, 1993), was specifically used to rule out any artifact by overexpression. To obtain the chromosome-borne GFP-Ypt3, instead of the plasmid-borne GFP-Ypt3, the fused genes with the nmt1 promoter at various levels were subcloned into the vector containing the ura4+ marker and were integrated into the chromosome at the ura4+ gene locus of KP1245 (h+ leu1-32 ura4-294).

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the Quick Change mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Microscopic Analysis

Standard techniques were used for microscopy (Hagan and Hyams, 1988). For microscopic observation, cells were grown to exponential phase in YPD medium at 27°C, shifted to various conditions as indicated in the figure legends, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.0). To visualize the DNA and septum, cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and Calcofluor, respectively.

For F-actin staining, cells were fixed in 3% formaldehyde in PBS for 30 min (Balasubramanian et al., 1997) and 1 μl of 100 μg/ml rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to 50 μl of fixed cell suspension. After 30 min at room temperature, the excess phalloidin was washed away with PBS.

To visualize the Golgi apparatus, Gma12, a Golgi marker (Chappell et al., 1994), was tagged at the C terminus with hemagglutinin (HA). HA-tagged Gma12 was subcloned into pREP81 (Maundrell, 1993). The plasmid was transformed into cells expressing GFP-Ypt3 for colocalization studies.

Cells were examined by differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescent microscopy using an Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Photographs were taken with a SPOT2 digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Images were processed with the CorelDRAW software (Corel Corporation Inc., Ottawa, ON).

For the treatment with latrunculin A (LAT-A; Molecular Probes Inc.), a stock solution of LAT-A was made in DMSO (50 mM) and used at a concentration of 100 μM.

FM4–64 Labeling

Vacuoles were labeled with FM4–64. Cells were grown to exponential phase in YPD medium at 27°C. Samples of 250 μl of cells were incubated with medium containing 80 μM FM4–64 for 30 min at 27°C. The cells were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 1 min, washed by resuspending in YPD to remove free FM4–64, and collected by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 1 min. Cells were then resuspended in YPD and incubated for 2–3 h at 27°C before microscopic observation.

Electron Microscopy

Conventional electron microscopy was performed (Sato et al., 1996) with some modifications. Cells were grown to exponential phase in YPD medium at 27°C, shifted to various conditions as indicated in the figure legends, washed with distilled water, and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 2 h. Cells were washed with the same buffer and then postfixed with 3% potassium permanganate in distilled water at room temperature for 90 min. After washing with distilled water, cells were embedded in 2% agarose, and then block staining was carried out with 2% uranyl acetate in distilled water at 4°C for >30 min. Blocks were dehydrated with a graduated acetone series and were embedded in Quetol 653 mixture. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and were observed with a transmission electron microscope (model H-7000; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 75 kV.

Quantification of micrographs was carried out as previously described (Jedd et al., 1997). To distinguish small vesicles, large vesicles, and Golgi-like structures (cisternae and Berkeley body-like structures), all of which were manifested as electron-dense profiles of varying size and shape, the following criteria were used. Profiles were counted as small vesicles if they were 50–80 nm in diameter, and as large vesicles if they were 100–150 nm in diameter. Linear membranous profiles >200 nm in length were scored as cisternae. Circular membranous structures >200 nm in diameter were scored as Berkeley body-like structures (Novick et al., 1981). Thirty cells were counted for each strain.

Expression and Detection of GFP Fused with the Leader Sequence of pho1+ Acid Phosphatase

GFP fused with the leader sequence of pho1+ acid phosphatase (SPL-GFP) was subcloned into the expression vector pREP1 (Braspenning et al., 1998). Cells transformed with the pREP1-SPL-GFP construct were grown to early log phase in EMM containing 4 μM thiamine. Cells were then spun and washed in thiamine-free EMM and allowed to resume growth. After 24 h, cells were collected and transferred to fresh medium. Then, cells were examined at distinct conditions as shown in Figure 8, A and B. Fluorescence of the SPL-GFP–expressing cells was visualized without fixation. For immunoblot detection, proteins present in the growth media were precipitated with 0.015% deoxycholic acid and 10% trichloroacetic acid and washed with acetone three times. To prepare the crude cell extracts, cells were broken mechanically by vortexing for 100 s at 4°C with glass beads in the homogenizing buffer, after which the glass beads and cellular debris were removed by centrifugation. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-GFP antibody.

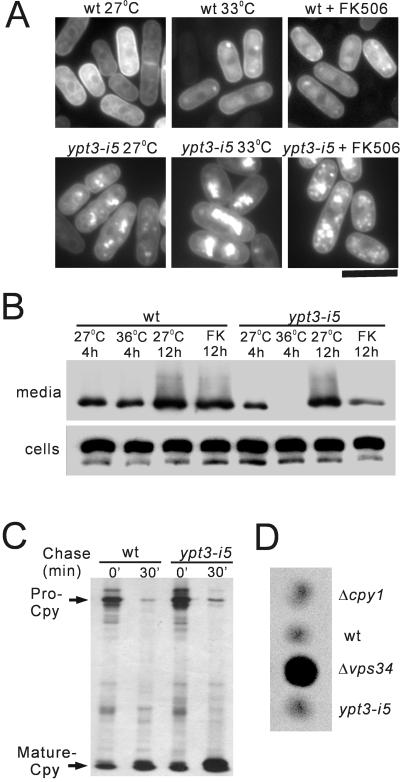

Figure 8.

The ypt3-i5 mutant shows a specific defect in the exocytic pathway. (A) Accumulation of SPL-GFP in the ypt3-i5 mutant. Wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells expressing SPL-GFP were cultured in EMM medium at 27, 33, or 27°C with the addition of FK506 for 2 h, and the localization of SPL-GFP was tested by fluorescence microscopy analysis. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Defective secretion of SPL-GFP to the growth medium in the ypt3-i5 mutant. Wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells expressing SPL-GFP were cultured at 27 or 36°C for 4 h or at 27°C with or without the addition of FK506 (FK) for 12 h. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western Blotting using anti-GFP antiserum. Top panel: the trichloroacetic acid-precipitate of supernatant of 5 × 106 cells; bottom panel, cell extract of 1 × 106 cells. (C) Processing of carboxypeptidase Y in vivo. Wild-type strain and ypt3-i5 mutant cells were pulse-labeled with Express-35S-label for 10 min at 28°C and chased. The immunoprecipitates were separated on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel. The autoradiograms of the fixed dried gels are shown. (D) Immunoblot analysis of the carboxypeptidase Y. Cells were grown on the nitrocellulose filter overnight at 30°C, and the filter was processed for immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody against S. pombe Cpy1. Δcpy1 (MTD2) was used as a negative control, and Δvps34 (KTP1) was used as a positive control for Cpy1 missorting.

Pulse-Chase Analysis and Immunoblot Analysis of the S. pombe Cpy1 protein

Pulse-chase analysis and immunoprecipitation of the vacuolar carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) were carried out as previously described (Tabuchi et al., 1997). Immunoblot analysis of the CPY was performed by replica-plating freshly grown spots onto nitrocellulose for overnight growth (Black and Pelham, 2000). Antibody incubations were carried out using rabbit polyclonal antibody against S. pombe Cpy1 (Tabuchi et al., 1997).

RESULTS

Isolation of the its5-1/ypt3-i5 Mutant

To better understand the in vivo functions of calcineurin, we took a genetic approach to identify genes that are involved in the calcineurin pathway. The rationale behind this approach was based on the following. Calcineurin is an in vivo target of FK506 in fission yeast, and inhibition of calcineurin activity by gene disruption or by the addition of FK506 to the media does not affect the vegetative growth of fission yeast (Yoshida et al., 1994). Moreover, wild-type cells exposed to FK506 acquire all the phenotypes of calcineurin deletion including cytokinesis abnormality (Yoshida et al., 1994) and Cl− sensitivity (Sugiura et al., 1998). Thus, mutants that require calcineurin activity for vegetative growth will not grow in the presence of FK506. Using this approach, we isolated eight mutants that showed both immunosuppressant and temperature sensitivity, and these loci were designated its. Complementation analysis of these its mutants showed that they define eight different loci its1–8 (Zhang et al., 2000; Yada et al., 2001). Here, we focus on the characterization of the its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant.

its5-1/ypt3-i5 Is a Novel Allele of the ypt3+ Gene that Encodes a Homolog of Mammalian Rab11 GTP-Binding Protein

The its5+ gene was cloned by complementation of the ts growth defect. Nucleotide sequencing of the cloned DNA fragment revealed that its5+ gene encodes the Ypt3 protein, which was previously reported (Miyake and Yamamoto, 1990). Ypt3 showed a high homology to mammalian Rab11 GTPase (148/214, 69% identity) and to S. cerevisiae Ypt31 (132/214, 62% identity) and Ypt32 (135/214, 63% identity). To investigate the relationship between the cloned ypt3+ gene and its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant, linkage analysis was performed as follows. The entire ypt3+ gene was subcloned into the pUC-derived plasmid containing S. cerevisiae LEU2 gene and integrated by homologous recombination into the genome of the wild-type strain HM123. The integrant was mated with the ypt3-i5 mutant. The resulting diploid was sporulated, and tetrads were dissected. A total of 24 tetrads were dissected. In all cases, only parental ditype tetrads were found, indicating allelism between the ypt3+ gene and the its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutation (our unpublished results). Accordingly, we renamed the its5-1 mutant as the ypt3-i5 mutant.

As shown in Figure 1A, when cultured at 36°C or in the presence of FK506 at 27°C, ypt3-i5 mutant cells were not able to grow, whereas wild-type cells grew normally. The cloned ypt3+ gene complemented the temperature-sensitive growth defect as well as the FK506-sensitive growth defect of ypt3-i5 mutant cells. Consistent with FK506 sensitivity of ypt3-i5 mutants, when we crossed the ypt3-i5 with calcineurin deletion (Δppb1), no double mutant was obtained at any temperature (our unpublished results), indicating that ypt3-i5 and Δppb1 are synthetically lethal. These results suggest that Ypt3 is involved in the pathway performing overlapping function with calcineurin.

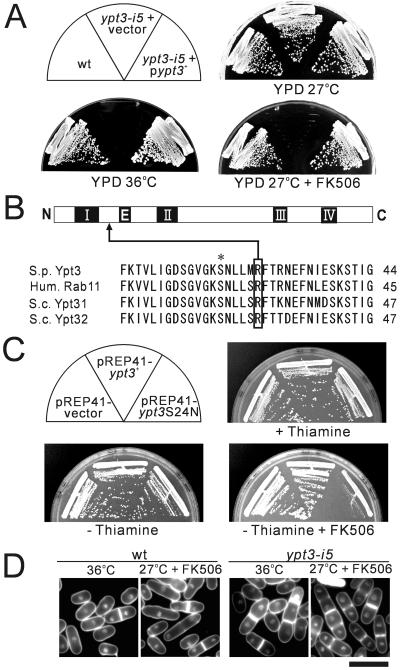

Figure 1.

Mutation in ypt3+ gene caused immunosuppressant- and temperature-sensitive phenotypes. (A) The immunosuppressant and temperature sensitivity of its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant cells. Wild-type (wt) and its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutant cells transformed with multicopy vector pDB248 or the vector carrying ypt3+ gene were streaked onto each plate, containing YPD or YPD plus 0.5 μg/ml FK506, and incubated at 27°C or 36°C. (B) The its5-1/ypt3-i5 mutation is in a conserved residue. The linear presentation of the structure of Rab GTPases and the predicted amino-acid sequence of Ypt3 with the corresponding region of human Rab11, Ypt31, and Ypt32 of the budding yeast. The conserved motifs involved in the GTP-binding (II, III, and IV) and GTP-hydrolysis (I and II), are represented in black boxes. The black box marked E denotes the effector region. Arrow indicates the mutation site in the conserved Arg29 of Ypt3, which when mutated to histidine resulted in immunosuppressant and temperature-sensitive function in Ypt3. Asterisk indicates the conserved Ser24, which was used to create a dominant-negative form of Ypt3 protein. S. p., S. pombe; Hum., Human; S. c., S. cerevisiae; These sequence data are available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession numbers: Ypt3, X52100; Rab11, X56740; Ypt31, X72833; and Ypt32, X72834. (C) Effects of expression of Ypt3 and dominant-negative Ypt3 (Ypt3S24N). Cells of wild-type (HM123) transformed with pREP41 vector, pREP41-ypt3+, or pREP41-ypt3S24N, were streaked onto each plate containing EMM, EMM plus FK506 with or without 2 μM thiamine and incubated for 3 d at 33°C. (D) Fluorescence micrographs of wild-type (wt) and ypt3-i5 mutant cells stained with DAPI and Calcofluor. Cells were shifted to restrictive temperature (36°C) for 6 h, or FK506 was added for 6 h and incubated at 27°C and then stained with DAPI (to visualize DNA) and Calcofluor (to visualize cell wall and septum). Bar, 10 μm.

A single base change (G to A) was detected in the ypt3-i5 gene, which caused the replacement of the conserved Arg29 in Ypt3 proteins by a histidine residue (Figure 1B). The mutation changes an amino acid that is conserved in structure among Rab11/Ypt3 proteins.

We constructed a dominant-negative mutant form of the Ypt3 protein, in which the conserved Ser24 among Rab11/Ypt3 proteins (Figure 1B, asterisk) was mutated to Asn (Ypt3S24N). This mutation was constructed by analogy to the dominant-negative Rab11S25N (Ren et al., 1998). We examined the effect of its expression in wild-type cells. Dominant-negative Ypt3S24N and wild-type Ypt3 were expressed from thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter on pREP41 vector in wild-type cells (Maundrell, 1993; Basi et al., 1993). Notably, wild-type cells expressing Ypt3S24N exhibited severe FK506-sensitive growth defect, whereas cells expressing wild-type Ypt3 grew well (Figure 1C). Thus, expression of dominant-negative Ypt3S24N is lethal in combination with inactivation of calcineurin, supporting our genetic evidence of synthetic-lethal interaction between calcineurin deletion and the ypt3-i5 mutant.

Shift to the Restrictive Temperature or Addition of FK506 to the Culture Media Impaired Cytokinesis of ypt3-i5 Mutant Cells

We examined the morphological changes in wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells, which were cultured at the permissive temperature and shifted to the restrictive temperature. Microscopic observation revealed that upon shift to 36°C, many mutant cells had an unusually thick septum brightly stained with Calcoflour. Some of these cells had multiple thick septa (Figure 1D). On addition of FK506 to the medium at the permissive temperature, ypt3-i5 mutant cells showed a dramatic change compared with wild-type cells. Nearly 100% of ypt3-i5 mutant cells were septated at 6 h, and the frequency of multiple-septated cells was unusually high (Figure 1D). Together, these results indicate that Ypt3 is required for completion of cytokinesis, and loss of calcineurin activity accentuates the defective cytokinesis of ypt3-i5 mutant cells, suggesting a significant functional interaction between Ypt3 and calcineurin in cytokinesis.

To investigate why ypt3-i5 mutant cells failed to separate, we compared the septum structure of wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells at the elevated temperature by electron microscopy. As expected, the septa of ypt3-i5 mutant cells were 100–200% thicker than those of wild-type cells (see Figure 6A), consistent with what was observed with Calcoflour staining (Figure 1D). These results suggest the possibility that the synthesis of the division septum is defective in ypt3-i5 mutant cells and that the structure is cleaved less efficiently, thereby causing abnormality in cytokinesis.

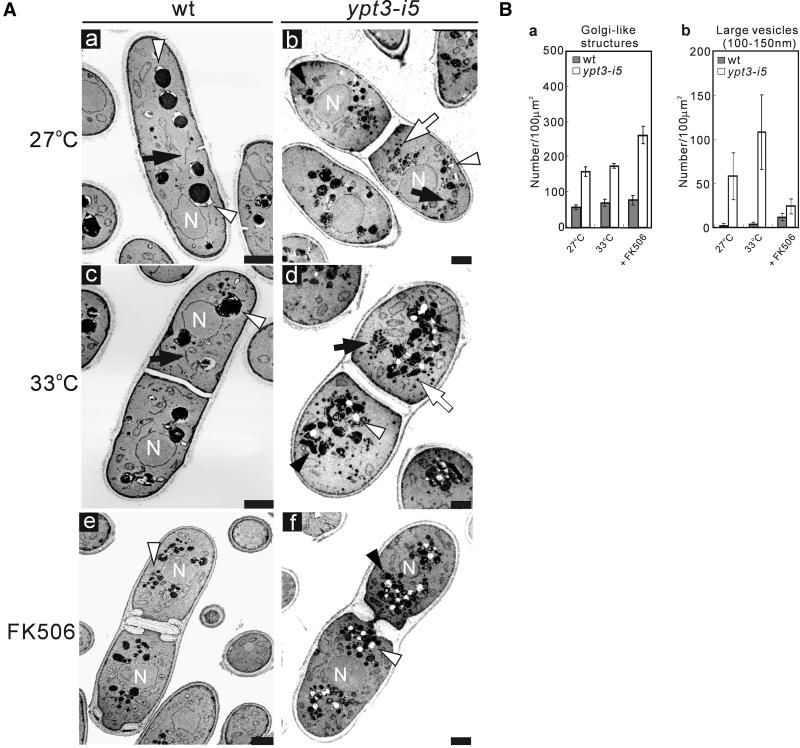

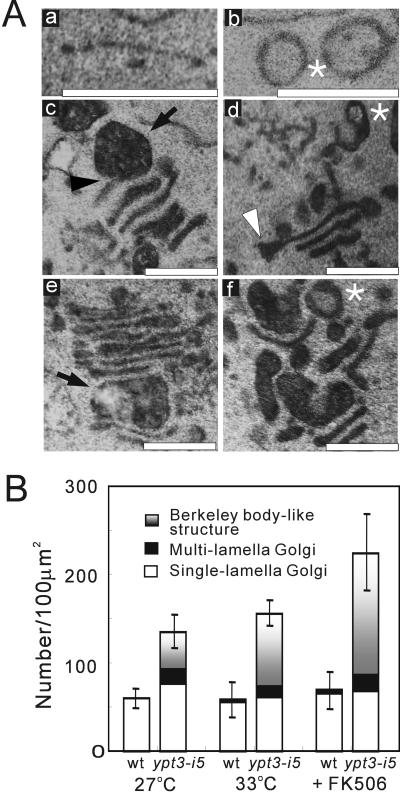

Figure 6.

Electron microscopic analysis of ypt3-i5 mutant cells. (A) Wild-type cells (wt) and ypt3-i5 mutant cells were analyzed by electron microscopy. Electron micrographs of the representative cells are shown for the following strains: (a) wild-type and (b) ypt3-i5 mutant strain grown at 27°C, (c) wild-type and (d) ypt3-i5 mutant strain cultured at 33°C for 4 h, (e) wild-type and (f) ypt3-i5 mutant strain treated with FK506 for 12 h at 27°C. Black arrows indicate a single Golgi cisterna of wild-type cells and stacked Golgi cisternae in the ypt3-i5 mutant. Black arrowheads point to the electron-dense membranous structures visible in the ypt3-i5 mutant. White arrows point to the accumulation of large vesicles (100–150 nm). White arrowheads point to the vacuoles of wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells. N, nucleus. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Quantification of the distinct membranous structures that accumulate in wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells at 27, 33, or 27°C with the addition of FK506: (a) Golgi-like structures (Golgi cisternae and Berkeley body-like structure), (b) large vesicles (100–150 nm). Wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells are indicated as gray bars and white bars, respectively. Bars represent the mean number of structures in 30 cell sections. Data are normalized to a density per 100 μm2. Error bars, 1 SD.

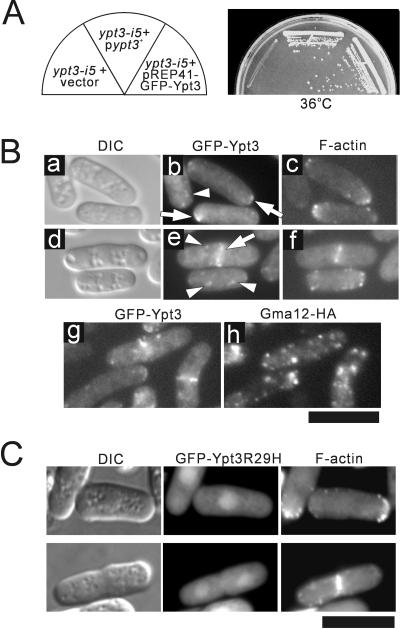

Intracellular Localization of Ypt3

To study the intracellular localization of Ypt3, we tagged the 5′ end of ypt3+ with the sequence encoding GFP. The expression of GFP-Ypt3 complemented both the temperature-sensitive growth defect of the ypt3-i5 mutant (Figure 2A) and the synthetic lethality of ypt3-i5 and Δppb1 mutant (our unpublished results), indicating that the tagged protein is fully functional.

Figure 2.

Intracellular localization of Ypt3. (A) Complementation of the temperature sensitivity of the ypt3-i5 mutant by the expression of GFP-Ypt3. The ypt3-i5 mutant was transformed with pREP41-GFP-Ypt3 or control vector and streaked onto EMM plate without thiamine and incubated at 36°C for 3 d. (B) Subcellular localization of Ypt3 tagged with GFP. The fused gene encoding GFP-Ypt3 was integrated into the chromosome of wild-type cells under the control of the nmt1 promoter of pREP41 (chromosome-borne GFP-Ypt3; see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Cells were grown in the absence of thiamine, and cells of midlog phase were fixed and then stained for actin with rhodamine-phalloidin. Representative patterns during interphase (a–c) and mitosis (d–f) are shown. Arrows point to the colocalization of GFP-Ypt3 with actin. Arrowheads point to a punctate distribution of GFP-Ypt3, which did not colocalize with actin. Colocalization study based on the expressed GFP-Ypt3 and immunocytochemistry with anti-HA antibody for Gma12-HA (g and h, respectively, see MATERIALS AND METHODS) revealed that Ypt3 was not preferentially concentrated in the Golgi apparatus. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Defective intracellular localization of mutant Ypt3 protein. ypt3-i5 mutant cells expressing the GFP-Ypt3R29H were grown at 27°C for 6 h and then fixed and stained for actin with rhodamine-phalloidin.

We examined the localization of Ypt3 in wild-type cells by expressing the GFP-Ypt3 fusion protein under the control of the nmt1 promoter. Two prominent staining features were observed: one, the localization of Ypt3 at the cell tips and at the medial region, similar to F-actin as visualized with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (Marks et al., 1986), and two, the punctate structures scattered throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 2B, b and e, arrowheads). GFP fluorescence at the cell tips and at the medial region were observed in interphase and mitotic cells, respectively (Figure 2B, b and e, respectively). In contrast, the punctate structures were observed at all phases of the cell cycle. The size and number of the punctate structures did not change at various expression levels, and similar staining patterns were obtained for the plasmid- and chromosome-borne GFP-Ypt3, indicating that these punctate structures are not artifactual staining caused by overexpression (our unpublished results). To determine whether these punctate structures indicate the Golgi-associated localization of Ypt3, the colocalization of GFP-Ypt3 and Gma12-HA was examined. Because double staining showed two distinct patterns instead of a simple colocalization pattern, this indicates that cytoplasmic punctate staining of Ypt3 is not related to Golgi. Alternatively, Gma12 and Ypt3 may reside in different Golgi compartments. In S. cerevisiae, endosomes have a punctate (Golgi-like) appearance by light microscopy (Lewis et al., 2000). Although endosomal morphology of S. pombe has not been well characterized, the punctate staining of GFP-Ypt3 may represent endosomal compartments (Figure 2B, g and h).

The localization of GFP-Ypt3R29H mutant protein (derived from the ypt3-i5 mutant) was also examined. Interestingly, GFP-Ypt3R29H mutant protein was no longer localized to discrete regions of the cell, and there was no punctate staining. Instead, the whole cytoplasm and the nucleus were stained (Figure 2C), indicating that the conserved Arg29 is primarily required for the specific localization of Ypt3 protein.

Ypt3 Localization to Cell Tips and the Medial Region is Actin Dependent

The fact that F-actin and Ypt3 localized to the similar region of the cell prompted us to determine whether the actin cytoskeleton was required for the localization of GFP-Ypt3. To address this, F-actin was depolymerized with LAT-A (Spector et al., 1989). After 10 min upon LAT-A addition, Ypt3 localization to both the growing ends and the medial region was abolished (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the number of the punctate GFP-associated structures in the cytoplasm increased after LAT-A treatment, suggesting that these structures were dispersed from the polarized growth sites. Thus, the cortical actin cytoskeleton appears to be essential for the correct localization of theYpt3 protein to polarized growth sites. Because secretory vesicles and endosomes are known to be located at places of active cell growth, these results may suggest that Ypt3 is concentrated at secretory vesicles or endosomes.

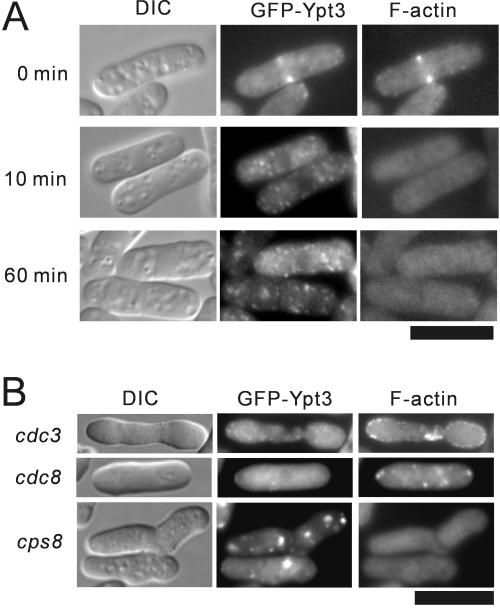

Figure 3.

Polarized GFP-Ypt3 localization is dependent on the integrity of F-actin cytoskeleton. (A) Mislocalization of Ypt3 upon disruption of the F-actin cytoskeleton. Wild-type cells expressing chromosome-borne GFP-Ypt3 were treated with LAT-A for 10 min and 60 min and then stained for F-actin with rhodamine-phalloidin (bottom). (B) Lack of the GFP-Ypt3 localization to specific growth sites in mutants with defects in actin-binding proteins. cdc3, cdc8, and cps8 actin mutant cells were grown at 36°C for 6 h and processed for fluorescence microscopy. Bar, 10 μm.

To disrupt the actin cytoskeleton by another approach, the ts profilin mutant cdc3, the ts tropomyosin mutant cdc8, and the ts actin mutant cps8 (Balasubramanian et al., 1992, 1994; Ishiguro and Kobayashi, 1996) were transformed with the GFP-Ypt3 fusion plasmid and incubated at restrictive temperature. Under these conditions, the F-actin patches associated with the cell periphery and the actomyosin ring structure failed to form, resulting in mitosis without cytokinesis. As expected, these mutants failed to localize GFP-Ypt3 to either cell ends or the cell center (Figure 3B). These results reinforce the conclusion that the polarized localization of Ypt3 is dependent on the integrity of the F-actin cytoskeleton.

The ypt3-i5 Mutant Is Defective in Cell Wall Integrity

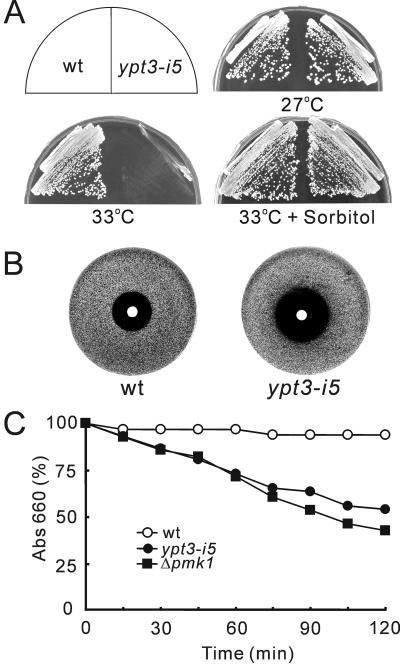

Three lines of evidence indicate that Ypt3 is required for cell wall integrity in fission yeast. First, the ypt3-i5 mutant showed osmo-remedial temperature sensitivity. Addition of 1.2 M sorbitol, an osmotic stabilizer, to the growth medium complemented the temperature-sensitive phenotype of the ypt3-i5 mutant (Figure 4A). Second, the ypt3-i5 mutant displayed hypersensitivity to the detergent SDS (Figure 4B) and to Calcofluor (our unpublished results). Finally, we performed β-glucanase treatment (Shiozaki and Russell, 1995; Toda et al., 1996) to ypt3-i5 mutant cells, Δpmk1 cells, and wild-type cells. ypt3-i5 mutant cells lysed faster than wild-type cells. The sensitivity of ypt3-i5 mutant cells to β-glucanase was as severe as that of the Δpmk1 cells (Figure 4C), which lack a MAP kinase regulating the cell wall integrity of fission yeast (Toda et al., 1996), thereby indicating that ypt3-i5 mutant cells are defective in cell wall integrity.

Figure 4.

ypt3-i5 mutant cells are defective in cell wall integrity. (A) Rescue of the ypt3-i5 mutant with an osmotic stabilizer. Wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells were streaked onto YPD plate with or without 1.2 M sorbitol and incubated at 27°C or 33°C for 3 d. (B) A halo assay showing supersensitivity of ypt3-i5 mutant cells to SDS. Approximately 105 wild-type or ypt3-i5 mutant cells were spread onto YPD plates with soft agar. After the agar solidified, sterile filter papers spotted with 5 μl of 20% SDS were placed in the center of each plate. (C) Cell wall digestion of wild-type, ypt3-i5 mutant and Δpmk1 strains by β-glucanase. Cells exponentially growing in YPD medium were harvested and incubated with β-glucanase (Zymolyase) at 30°C with vigorous shaking. Cell lysis was monitored by measuring optical density at 660 nm (the value before adding the enzyme was taken as 100%).

Ypt3 Plays an Essential Role in Vacuole Fusion

In the course of studying cytokinesis by electron microscopy, we noted the high incidence of abnormally small vacuoles in ypt3-i5 mutant cells and in wild-type cells treated with FK506 (see Figure 6A). This prompted us to examine more closely the functional relationship between Ypt3 and calcineurin in regulating vacuolar morphology.

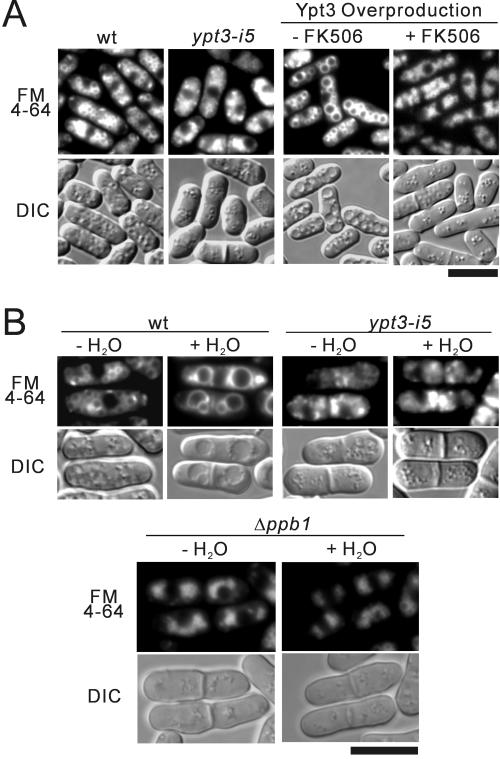

FM4–64, a member of the family of fluorescent dyes (Vida and Emr, 1995), was used to compare vacuolar morphology of wild-type cells and ypt3-i5 mutant cells. Numerous small vacuoles, but no large vacuole, were observed in ypt3-i5 mutant cells (Figure 5A). Interestingly, unusually large vacuoles were observed in wild-type cells expressing Ypt3 under the native promoter from a multicopy plasmid (Figure 5A, Ypt3 overproduction − FK506). Moreover, upon treatment with FK506, larger vacuoles completely disappeared, and vacuoles became as small as those seen in ypt3-i5 mutant cells (Figure 5A, Ypt3 overproduction + FK506).

Figure 5.

ypt3-i5 mutant cells are defective in vacuole fusion. (A) Wild-type (wt) and ypt3-i5 mutant cells were grown in YPD medium and labeled with FM4–64 fluorescent dye (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Cells were then collected and examined by DIC and fluorescence microscopy. Wild-type cells transformed with a multicopy plasmid carrying ypt3+ gene, under the native promoter (Ypt3 Overproduction) were grown in EMM medium and incubated in the presence (+ FK506) or absence (− FK506) of FK506 for 20 h and examined as above. (B) Wild-type, the ypt3-i5 mutant, and Δppb1 cells were grown in YPD medium. Cells were collected, labeled with FM4–64, and resuspended in H2O (+ H2O). Photographs were taken after 30 min. Bar, 10 μm.

Larger vacuoles resulting from vacuole fusion evidently appeared in the wild-type cells treated with hypotonic stress for 30 min (Figure 5B, wt), as described by Bone et al. (1998). In contrast, vacuoles remained small and numerous in ypt3-i5 mutant cells suspended in water (Figure 5B, ypt3-i5), and no vacuole fusion was observed even after more than 24 h (our unpublished results). Vacuoles of the Δppb1 cells were on the average smaller than those of wild-type cells. In contrast to the ypt3-i5 mutant, which showed no large vacuole, large vacuoles in Δppb1 cells were observed after long exposure to the hypotonic stress. The vacuolar fusion process appeared to be very slow and apparently no fused large vacuole was observed after the 30-min hypotonic stress (Figure 5B, Δppb1).

Taken together, these findings suggest that Ypt3 GTPase is essential for vacuole fusion in fission yeast and that calcineurin is also involved in this cellular process.

ypt3-i5 Mutant Cells Accumulated Aberrant Golgi-like Structures and Large Vesicles

The fact that ypt3+ encodes a member of Ypt GTPase family prompted us to investigate whether the ypt3-i5 mutant showed a defect in secretory pathway by electron microscopy. In general, mutants defective in the exocytic function have been shown to accumulate an organelle or vesicular intermediate of the secretory compartments that precede the step in which they first function (Novick et al., 1981; Kaiser and Schekman, 1990). To determine whether ypt3-i5 mutant cells accumulate such membrane structures, the cells were cultured at the permissive temperature (27°C), at the nonpermissive temperature (33°C) or at 27°C with the addition of FK506, and examined by electron microscopy. As shown in Figure 6A, even at the permissive temperature, the ypt3-i5 mutant accumulated aberrant membrane structures, which became more remarkable when the mutant cells were shifted to 33°C or treated with FK506. According to similar studies with budding yeast (Jedd et al., 1997), we quantified the accumulation of the aberrant membrane structures such as small vesicles similar to transport vesicles from ER to Golgi in budding yeast (50–80 nm), Golgi-like structures (cisternae and Berkeley body-like structures), and large vesicles resembling post-Golgi secretory vesicles (100–150 nm). The numbers of these three types of membrane structures in the ypt3-i5 mutant were compared with those in wild-type cells. Even at the permissive temperature, the ypt3-i5 mutant exhibited an abundance of Golgi-like structures (Figure 6Ba), similar to the phenotype of S. cerevisiae ypt31/32 mutant cells. Surprisingly, the accumulation of large vesicles was also seen in ypt3-i5 mutant cells (Figure 6Bb), and this was not observed in S. cerevisiae ypt31/32 mutant cells but was the case in sec4 mutant cells, which showed a defect in the fusion of post-Golgi vesicles with the plasma membrane (Novick and Brennwald, 1993). At the restrictive temperature, the accumulation of large vesicles was more remarkable (Figure 6Bb). Interestingly, when treated with FK506, the accumulation of large vesicles became negligible, whereas the number of Golgi-like structures increased dramatically (Figure 6Bb). There was no statistical difference in the number of small vesicles between ypt3-i5 mutant and wild-type cells in all of these conditions (our unpublished results). Taken together, these results suggest that Ypt3 GTPase plays an essential role in protein transport from the Golgi apparatus as well as for the later step of the exocytic pathway in fission yeast and that calcineurin may be involved in the regulation of these cellular events. Another possibility is that accumulation of Golgi membranes is caused by a block in retrograde transport to the Golgi if components required for Golgi exit are not recycled.

ypt3-i5 Mutant Cells Show Aberrant Golgi Profiles

To further confirm the role of Ypt3 in the Golgi apparatus, we analyzed and quantified Golgi-like structures using electron microscopy and then classified them as single-lamella Golgi, multi-lamella Golgi, and Berkeley body-like structures (Figure 7). Wild-type Golgi structure was mostly observed as an elongated cisternae (Figure 7Aa). The ypt3-i5 mutant accumulated numerous aberrant membrane structures (Figure 7A, c and e, black arrow) and stacked Golgi cisternae (Figure 7A, c–f). Some membrane structures had characteristic morphology of “Berkeley bodies” known to represent abnormal Golgi membranes (Figure 7Ab) and some electron dense membrane structures connected to the Golgi stacks, suggesting that they were derived from the Golgi apparatus (Figure 7Ac, black arrowhead). Mutant Golgi structures were longer and thicker than those seen in wild-type cells (length, 645 ± 269 and 469 ± 88 nm, respectively; thickness, 46.5 ± 14.2 and 13.7 ± 2.8 nm, respectively) and were occasionally swollen to ∼150 nm at their periphery (Figure 7Ad, white arrowhead), indicating a possible defect in vesicle formation. It should be noted that these alterations of Golgi profiles conferred by the ypt3-i5 mutation clearly resemble those reported in S. cerevisiae ypt31/32 mutant cells (Benli et al., 1996; Jedd et al., 1997).

Figure 7.

Analysis of Golgi-like structures accumulated in ypt3-i5 mutant cells. (A) Details of Golgi-like structures in wild-type (a) and ypt3-i5 mutant cells at 27°C (b) or at 33°C for 4 h (c–f): wild-type Golgi is usually observed as an elongated cisternae (a) Example of stacked cisternae connected to electron-dense membrane structure in the mutant strain is shown (c, arrowhead). Black arrows indicate electron-dense membrane structures (c and e). Asterisks in b, d, and f show spherical and enlarged cup-shaped membrane structures resembling “Berkeley bodies.” White arrowhead indicates swelling to 150 nm at the cisternal rim, which may represent an intermediate preceding vesicle formation by membrane fission (d). Bar, 0.5 μm. (B) Quantification of cisternal profiles and Berkeley body-like structures in wild-type and ypt3-i5 mutant cells, which were cultured at 27 or 33°C for 4 h or 27°C with the addition of FK506 for 12 h. The percentage of the total structures counted as single-lamella Golgi, multilamella Golgi, or Berkeley body-like structures are indicated by white bars, black bars, and gray bars, respectively.

As shown in Figure 7B, even at 27°C, the ypt3-i5 mutant exhibited marked accumulation of multi-lamella Golgi and Berkeley body-like structures, whereas these were negligible in the wild-type strain. On temperature upshift or FK506-treatment, the total number of aberrant Golgi profiles increased, and the population became dominated by Berkeley body-like structures (Figure 7B, 31% of total at 27°C, 55% of total at 33°C, and 61% of total with FK506 at 27°C). These results suggest that ypt3-i5 mutant cells have a defect in the Golgi function, which is accentuated upon temperature upshift, or FK506-treatment.

ypt3-i5 Mutant Cells Show Secretion Defect That Is Exacerbated by FK506 Treatment

Pho1 acid phosphatase undergoes glycosylation and proteolytic processing as it moves from the ER through the Golgi apparatus and from the Golgi to the plasma membrane. GFP fused with the pho1+ leader peptide (SPL-GFP) is secreted through the same pathway as Pho1 acid phosphatase (Braspenning et al., 1998). Because our electron microscopic study revealed that ypt3-i5 mutant cells have defects in the exocytic pathway, we expected that the ypt3-i5 mutant would accumulate SPL-GFP at some step(s) during the translocation process. As shown in Figure 8A, at 27°C, fluorescence of SPL-GFP could be mostly detected in the peri-nuclear, peri-plasma membrane regions in wild-type cells, and there was no dramatic change when they were shifted to 33°C or treated with FK506. In contrast, in ypt3-i5 mutant cells cultured at 27°C, SPL-GFP localized as large dots with bright fluorescence in the cytoplasm as well as in the regions stained in the wild-type cells. When shifted to 33°C, larger fluorescence clusters were observed in ypt3-i5 mutant cells. Interestingly, with the treatment of FK506, more dots but not larger dots could be observed in the ypt3-i5 mutant compared with those without any treatment.

Furthermore, we tried to determine whether the ypt3-i5 mutant showed a defect in secreting SPL-GFP to the medium (Figure 8B). At the permissive temperature, there was no marked difference in the amount of secreted SPL-GFP in the growth media. When shifted to 36°C for 4 h, the secretion of SPL-GFP was abolished in the ypt3-i5 mutant, whereas no remarkable change was seen in wild-type cells (Figure 8B). There was no dramatic change of secretion of SPL-GFP when the ypt3-i5 mutant was treated with FK506 for 4 h (our unpublished results). However, significant decrease of SPL-GFP detected in the growth medium was observed when the ypt3-i5 mutant was treated with FK506 for 12 h, whereas there was no observable change in wild-type cells (Figure 8B). Likewise, calcineurin null cells secrete SPL-GFP normally (our unpublished results). No remarkable difference in the amount of SPL-GFP detected in the cell extracts of all these samples was observed (Figure 8B, cells).

To investigate whether Ypt3 is involved in vacuolar protein sorting, pulse-chase analysis of CPY was performed. During a 15-min pulse of wild-type cells with Express 35S-label, an immunoreactive band with an apparent molecular mass of 110 kDa (proCPY) was detected. After 30 min of chase, the molecular mass of this 110-kDa form was converted to 32-kDa form (mature form of CPY) in wild-type cells (Figure 8C). In ypt3-i5 mutant cells, the maturation of CPY was not impaired significantly at the permissive temperature (Figure 8C). Similar results were obtained with the experiments at restrictive temperature and with FK506 treatment (our unpublished results). Immunoblot analysis also showed that vacuolar protein sorting was unaffected in the ypt3-i5 mutant (Figure 8D).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the functional analysis of an immunosuppressant- and temperature-sensitive mutant of the ypt3+ gene has indicated that Ypt3 GTPase functions in the fission yeast exocytic pathway. We have also indicated that Ypt3 mutation caused defects in secretion that lead to defects in cytokinesis and that these defects become lethal in the absence of calcineurin function. In addition, we have demonstrated that Ypt3 is required for cellular processes such as cell wall integrity and vacuole fusion in fission yeast. The functional and genetic interaction of the Rab family with calcineurin presented here provides the first link between the fission yeast exocytic pathway and the calcineurin functions.

Ypt3 GTPase Is Involved at Multiple Steps of the Fission Yeast Exocytic Pathway

Rab proteins exist in all eukaryotic cells and form the largest branch of the small GTP-binding protein superfamily. The human genome contains 60 Rab proteins (Bock et al., 2001). The yeast S. cerevisiae genome sequence encodes 11 Rab proteins. The fission yeast S. pombe genome sequence encodes 7 Rab proteins including Ypt3. The comparatively smaller number of Rab proteins in fission yeast makes it a simple model organism in the study of the exocytic pathway regulated by Rab proteins. Our present results support a hypothesis in which Ypt3 GTPase is involved at multiple steps of the exocytic pathway, that is, Ypt3 is required for the exit from the trans-Golgi as well as for the later step of the exocytic pathway.

The ypt3-i5 mutant accumulated aberrant Golgi-like structures similar to those reported in the mutation of Ypt31/32, a functional pair of budding yeast GTPases essential for exit from the trans-Golgi (Benli et al., 1996; Jedd et al., 1997). This observation support the essential role of Ypt3 for exit from the trans-Golgi. However, the immunofluorescence data showed a punctate staining that did not coincide with the Golgi marker Gma12. Although, to our knowledge, the presence of recycling endosomes has not been demonstrated in S. pombe, it is intriguing to hypothesize that Ypt3 may play a role in controlling traffic through the recycling endosome similar to its mammalian homolog Rab11 (Ullrich et al., 1996); and the recycling of components required for Golgi exit may be impaired. Future studies will be needed to reveal molecular details of the mechanism by which the ypt3-i5 mutant accumulated aberrant Golgi-like structures.

In addition, Ypt3 is suggested to be implicated in the post-Golgi membrane traffic based on the following observations. First, the ypt3-i5 mutant accumulated 100–150 nm vesicles, similar to the budding yeast sec4 mutant, which reportedly had a defect in the fusion of post-Golgi vesicles to plasma membrane (Novick and Brennwald, 1993). Second, Ypt3 showed a polarized localization similar to Sec4, which resided on the late secretory vesicles in budding yeast (Pruyne et al., 1998). These results support our hypothesis that Ypt3 plays a critical role in the later step of exocytic pathway of fission yeast.

Furthermore, Nakase et al. (2001) reported that fission yeast spo20+ gene encodes a homologue of S. cerevisiae Sec14, the major phosphatidylinositol transfer protein of budding yeast, and showed that Spo20 is required for Golgi secretory function by demonstrating that spo20-KC104 mutant accumulated aberrant Golgi cisternae at restrictive temperature. Interestingly, similar to the ypt3-i5 mutant, spo20-KC104 mutant is also defective in cell separation at the restrictive temperature. Furthermore, Spo20 localized at both cell poles and at the medial region at mitosis, and this localization requires the actin cytoskeleton. Because mammalian phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins likely regulate the fusion of secretory granules with the plasma membrane (Hay and Martin, 1993), Nakase et al. (2001) suggested that Spo20 may play an analogous role in fission yeast, in addition to its role in the protein transport from the yeast Golgi complex. Although the biochemical functions of Ypt3 and Spo20 are very different, the similarity in their intracellular localization and mutant phenotypes again suggest that Ypt3 is required for the exit from the trans-Golgi as well as for the later step of the exocytic pathway, suggesting that Ypt3 plays the roles of both Ypt31/32 and Sec4 in the exocytic pathway of the budding yeast.

The Pleiotropic Phenotypes of the ypt3-i5 Mutant May Result as a Consequence of Impaired Exocytic Pathway

The phenotypes of ypt3-i5 mutant cells, including defects in cytokinesis, cell wall integrity, and vacuole fusion may result as a consequence of impaired exocytic pathway. As shown in this study, Ypt3 showed a distribution at the growing tips and at the medial region in a cell cycle–dependent manner. In these regions, both synthesis and degradation of the cell wall take place to ensure tip growth and septum formation. Taken together, we hypothesize that Ypt3 protein may play a role in transport of enzymes implicated in cell wall synthesis, such as 1,3-β-glucan synthase, to the sites where cells will undergo polarized cell growth or cytokinesis. The morphological phenotypes of the ypt3-i5 mutant, including increased frequency of septated cells, appearance of multiple-septated cells, and abnormally thickened septa, strongly support this hypothesis.

We also hypothesize that Ypt3 is involved in the transport of the regulator of vacuole fusion, such as a SNARE complex, or that Ypt3 itself acts as a regulator of vacuole fusion. Recently, it has been reported that Ca2+/calmodulin signal controls the late phase of vacuole fusion (Peters and Mayer, 1998). It would be attractive to speculate that calcineurin also plays a role in vacuole fusion, by dephosphorylating some components required for vacuole fusion or vacuole membrane biogenesis.

Ypt3 and Calcineurin Synthetic Lethality

The present finding of synthetic lethal genetic interaction between Ppb1 calcineurin and Ypt3 GTPase mutation suggest a functional interaction between calcineurin and Ypt3. The functions of calcineurin have been shown to regulate vesicle transport in higher eukaryotic systems and to dephosphorylate several proteins required for clathrin-mediated vesicle recycling such as dynamin, amphiphysin, and synaptojanin (Marks and McMahon, 1998). However, we could not directly link calcineurin function to exocytosis in the present study. On the contrary, we obtained compelling data that exocytosis is not compromised in the absence of calcineurin function unless Ypt3 function is eliminated. Further studies are needed to define the significance of calcineurin in the fission yeast exocytic pathway.

The synthetic lethal interaction may be easily explained if the lack of calcineurin causes a decrease in the abundance of Ypt3. On the contrary, the lack of calcineurin did not cause any change in the level of mRNA or protein of Ypt3 (our unpublished results). It is possible that calcineurin regulates enzymes involved in cell wall synthesis and breakdown and therefore affects cell wall integrity. The secretory pathway is likewise involved in regulating cell wall structures, so that the combined defects in ypt3+ and ppb1+ lead to lethality. Consistent with this possibility, secretory defects in FK506-treated wild-type cells are nondetectable. Furthermore, loss of cell wall integrity seems to be the primary defect affecting ypt3-i5 viability, as shown in Figure 4, and is therefore most likely responsible for the synthetic lethal phenotype.

This study on the S. pombe Ypt3 protein, which has not been previously described in great detail, may expand the current knowledge of the function of Rab11-related proteins. In addition, the elucidation of the mechanisms of interaction between calcineurin and Ypt3 protein may be of general interest for an understanding of eukaryotic transport system and/or morphogenetic events.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Yingjie Zhang and Sharon A. Tooze for helpful discussions on the manuscript, to Shinichi Tanioka for able technical assistance, and to Fujisawa Japan Inc. for gifts of FK506. This work was jointly supported by research grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and a grant from the Novartis Foundation (Japan).

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.01–09–0463. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.01–09–0463.

REFERENCES

- Balasubramanian MK, Helfman DM, Hemmingsen SM. A new tropomyosin essential for cytokinesis in the fission yeast S. pombe. Nature. 1992;360:84–87. doi: 10.1038/360084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian MK, Hirani BR, Burke JD, Gould KL. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc3+ gene encodes a profilin essential for cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1289–1301. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian MK, McCollum D, Gould KL. Cytokinesis in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1997;283:494–506. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)83039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basi G, Schmid E, Maundrell K. TATA box mutations in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe nmt1 promoter affect transcription efficiency but not the transcription start point or thiamine repressibility. Gene. 1993;123:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90552-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach D, Piper M, Nurse P. Construction of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene bank in a yeast bacterial shuttle vector and its use to isolate genes by complementation. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;187:326–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00331138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benli M, Doring F, Robinson DG, Yang X, Gallwitz D. Two GTPase isoforms, Ypt31p and Ypt32p, are essential for Golgi function in yeast. EMBO J. 1996;15:6460–6475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MW, Pelham HR. A selective transport route from Golgi to late endosomes that requires the yeast GGA proteins. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:587–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock JB, Matern HT, Peden AA, Scheller RH. A genomic perspective on membrane compartment organization. Nature. 2001;409:839–841. doi: 10.1038/35057024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone N, Millar JB, Toda T, Armstrong J. Regulated vacuole fusion and fission in Schizosaccharomyces pombe: an osmotic response dependent on MAP kinases. Curr Biol. 1998;8:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braspenning J, Meschede W, Marchini A, Muller M, Gissmann L, Tommasino M. Secretion of heterologous proteins from Schizosaccharomyces pombe using the homologous leader sequence of pho1+ acid phosphatase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:166–171. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell TG, Hajibagheri MA, Ayscough K, Pierce M, Warren G. Localization of an alpha 1,2 galactosyltransferase activity to the Golgi apparatus of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:519–528. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.5.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy MJ, Cyert MS. Luv1p/Rki1p/Tcs3p/Vps54p, a yeast protein that localizes to the late Golgi and early endosome, is required for normal vacuolar morphology. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2429–2443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KW, Fink GR. Calcineurin inhibits VCX1-dependent H+/Ca2+ exchange and induces Ca2+ ATPases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2226–2237. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyert MS, Kunisawa R, Kaim D, Thorner J. Yeast has homologs (CNA1 and CNA2 gene products) of mammalian calcineurin, a calmodulin-regulated phosphoprotein phosphatase. J Cell Biol. 1991;124:351–363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyert MS, Thorner J. Regulatory subunit (CNB1gene product) of yeast Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphoprotein phosphatases is required for adaptation to pheromone. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3460–3469. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farcasanu IC, Hirata D, Tsuchiya E, Nishiyama F, Miyakawa T. Protein phosphatase 2B of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for tolerance to manganese, in blocking the entry of ions into the cells. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:712–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Engele P, Moilanan B, Cyert MS. Calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, is essential in yeast mutants with cell integrity defects and in mutants that lack a functional vacuolar H+-ATPase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4103–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan IM, Hyams JS. The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Cell Sci. 1988;89:343–357. doi: 10.1242/jcs.89.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Martin TFJ. Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein is required for ATP-dependent priming of Ca2+-activated secretion. Nature. 1993;366:572–575. doi: 10.1038/366572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R, Cubitt AB, Tsien RY. Improved green fluorescence. Nature. 1995;373:663–664. doi: 10.1038/373663b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro J, Kobayashi W. An actin point-mutation neighboring the ‘hydrophobic plug’ causes defects in the maintenance of cell polarity and septum organization in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:237–241. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedd G, Mulholland J, Segev N. Two new Ypt GTPases are required for exit from the yeast trans-Golgi compartment. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:563–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CA, Schekman R. Distinct sets of SEC genes govern transport vesicle formation and fusion early in the secretory pathway. Cell. 1990;61:723–733. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90483-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee CB, Crouch TH, Krinks MH. Calcineurin: a calcium- and calmodulin-binding protein of the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6270–6273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno T, Tanaka H, Mukai H, Chang CD, Hiraga K, Miyakawa T, Tanaka C. cDNA cloning of a calcineurin B homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;180:1159–1163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ, Nichols BJ, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Riezman H, Pelham HR. Specific retrieval of the exocytic SNARE Snc1p from early yeast endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:23–38. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD, J, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991a;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes (CMP1 and CMP2) encoding calmodulin-binding proteins homologous to the catalytic subunit of mammalian protein phosphatase 2B. Mol Gen Genet. 1991b;227:52–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00260706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks B, McMahon HT. Calcium triggers calcineurin-dependent synaptic vesicle recycling in mammalian nerve terminals. Curr Biol. 1998;8:740–749. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J, Hagan IM, Hyams JS. Growth polarity and cytokinesis in fission yeast: the role of the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 1986;5:229–241. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1986.supplement_5.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheos D, Kinsbury T, Ahsan U, Cunningham K. TCN1p/Crz1p, a calcineurin-dependent transcription factor that differentially regulates gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3445–3458. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maundrell K. Thiamine-repressible expression vectors pREP and pRIP for fission yeast. Gene. 1993;123:127–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90551-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza I, Rubio F, Rodriguez-Navarro A, Pardo JM. The protein phosphatase calcineurin is essential for NaCl tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8792–8796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, S., and Yamamoto, M. (1990). Identification of ras-related, YPT family genes in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 9, 1417–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Liu Y, Hirata D, Namba H, Harada S, Hirokawa T, Miyakawa T. Protein phosphatase type 2B (calcineurin)-mediated, FK506-sensitive regulation of intracellular ions in yeast is an important determinant for adaptation to high salt stress conditions. EMBO J. 1993;12:4063–4071. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase Y, Nakamura T, Hirata A, Routt SM, Skinner HB, Bankaitis VA, Shimoda C. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spo20+ gene encoding a homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sec14 plays an important role in forespore membrane formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:901–917. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P, Brennwald P. Friends and family: the role of the Rab GTPases in vesicular traffic. Cell. 1993;75:597–601. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P, Ferro S, Schekman R. Order of events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1981;25:461–469. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Mayer A. Ca2+/calmodulin signals the completion of docking and triggers a late step of vacuole fusion. Nature. 1998;396:575–580. doi: 10.1038/25133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozos TC, Sekler I, Cyert MS. The product of HUM1, a novel yeast gene, is required for vacuolar Ca2+/H+ exchange and is related to mammalian Na+/Ca2+ exchangers. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3730–3741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne DW, Schott DH, Bretscher A. Tropomyosin-containing actin cables direct the Myo2p-dependent polarized delivery of secretory vesicles in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1931–1945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren M, Xu G, Zeng J, De Lemos CC, Adesnik M, Sabatini DD. Hydrolysis of GTP on rab11 is required for the direct delivery of transferrin from the pericentriolar recycling compartment to the cell surface but not from sorting endosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6187–6192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Kobori H, Ishijima SA, Feng ZH, Hamada K, Shimada S, Osumi M. Schizosaccharomyces pombe is more sensitive to pressure stress than Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Struct Funct. 1996;21:167–174. doi: 10.1247/csf.21.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K, Russell P. Counteractive roles of protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) and a MAP kinase kinase homolog in the osmoregulation of fission yeast. EMBO J. 1995;14:492–502. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector I, Shochet NR, Blasberger D, Kashman Y. Latrunculins—novel marine macrolides that disrupt microfilament organization and affect cell growth: I. Comparison with cytochalasin D. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1989;13:127–144. doi: 10.1002/cm.970130302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos AM, Cyert MS. Calcineurin acts through the CRZ1/TCN1-encoded transcription factor to regulate gene expression in yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3432–3444. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R, Toda T, Dhut S, Shuntoh H, Kuno T. The MAPK kinase Pek1 acts as a phosphorylation-dependent molecular switch. Nature. 1999;399:479–483. doi: 10.1038/20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R, Toda T, Shuntoh H, Yanagida M, Kuno T. pmp1+, a suppressor of calcineurin deficiency, encodes a novel MAP kinase phosphatase in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:140–148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi M, Iwaihara O, Ohtani Y, Ohuchi N, Sakurai J, Morita T, Iwahara S, Takegawa K. Vacuolar protein sorting in fission yeast: cloning, biosynthesis, transport, and processing of carboxypeptidase Y from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4179–4189. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4179-4189.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegawa K, DeWald DB, Emr SD. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Vps34p, a phosphatidylinositol-specific PI3-kinase essential for normal cell growth and vacuole morphology. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3745–3756. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T, Dhut S, Superti FG, Gotoh Y, Nishida E, Sugiura R, Kuno T. The fission yeast pmk1+ gene encodes a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog which regulates cell integrity and functions coordinately with the protein kinase C pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6752–6764. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich O, Reinsch S, Urbe S, Zerial M, Parton RG. Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:913–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbe S, Huber LA, Zerial M, Tooze SA, Parton RG. Rab11, a small GTPase associated with both constitutive and regulated secretory pathways in PC12 cells. FEBS Lett. 1993;334:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida TA, Emr SD. A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:779–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yada T, Sugiura R, Kita A, Itoh Y, Lu Y, Hong Y, Kinoshita T, Shuntoh H, Kuno T. Its8, a fission yeast homolog of Mcd4 and Pig-n, is involved in GPI anchor synthesis and shares an essential function with calcineurin in cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13579–13586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Toda T, Yanagida M. A calcineurin-like gene ppb1+ in fission yeast: mutant defects in cytokinesis, cell polarity, mating and spindle pole body positioning. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1725–1735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sugiura R, Lu Y, Asami M, Maeda T, Itoh T, Takenawa T, Shuntoh H, Kuno T. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase its3 and calcineurin Ppb1 coordinately regulate cytokinesis in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35600–35606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]