Abstract

We report a water induced phase transformation in a flexible MOF, [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] (Hbtca = 1H-benzotriazole-5-carboxylic acid), that exhibits a two-step water vapor sorption isotherm associated with water-induced phase transformations. Variable temperature X-ray diffraction studies revealed that the dehydrated phase, LP-β, is almost isostructural with the previously reported solvated phase, LP-α. LP-β reversibly transformed to a partially hydrated phase, NP, at 5% RH, and a fully hydrated phase, LP-γ, at 47% RH. Structural studies reveal that host–guest and guest–guest interactions are involved in the NP, LP-α, and LP-γ phases. The LP-β phase, however, is atypical; molecular modeling studies indicating that it is indeed energetically favorable as a LP structure. To our knowledge, [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] is only the second sorbent that exhibits water induced LP-NP-LP transformations (after MIL-53) and represents the first regeneration optimized sorbent (ROS) with two steps at RH ranges relevant for both atmospheric water harvesting and dehumidification.

Population growth and climate change have resulted in water scarcity in many locations.1 Arid and semiarid climates are particularly vulnerable as their already limited water supply cannot be replenished quickly enough to meet utility. In low humidity climates, where relative humidity (RH) is typically 10–40%, water scarcity is compounded because traditional water-harvesting technologies such as fogwater collection are rendered inefficient.2 Atmospheric water harvesting (AWH) using water vapor sorbents (desiccants) is an emerging technology that could address water scarcity even under low humidity by improving the productivity and energy efficiency of moisture collection.3 In a typical AWH process, water vapor from the atmosphere is adsorbed by a sorbent with optimal kinetics and low energy of regeneration, a regeneration optimized sorbent (ROS),4 and concentrated after the desorption step by condensation.5,6

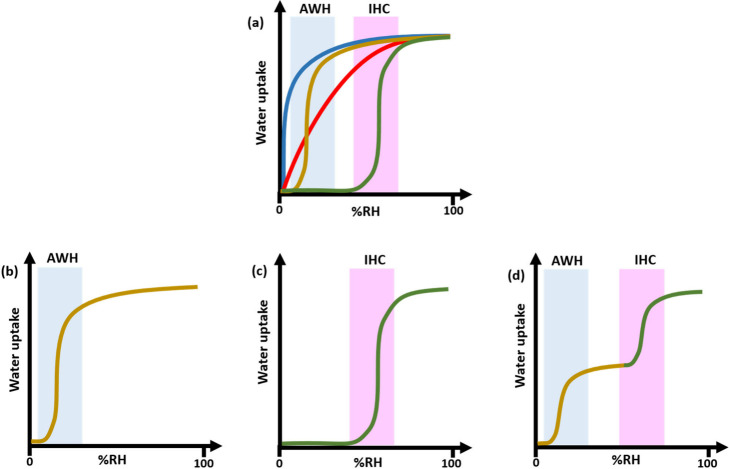

Another application for sorbent-based technologies is indoor humidity control (IHC).7,8 In the absence of adequate IHC measures, prolonged exposure to toxigenic fungi can trigger high levels of allergies and infectious diseases.9,10 Consequently, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers recommends that the appropriate IHC range for an indoor environment is 45–65% RH.11 Unfortunately, current IHC systems have large energy penalties that are the major component of a building’s energy consumption.11 Therefore, an ROS suitable for passive IHC in the range of 45–65% RH could reduce, perhaps significantly, the energy footprint of IHC systems. Sorbent-based technologies for water harvesting and humidity control require a suitable ROS which exhibits the following features:12−16 (i) high working capacity; (ii) hydrolytically and mechanically robust; (iii) sorbent regeneration at relatively low temperatures (<80 °C for AWH and IHC); and (iv) rapid adsorption and desorption of water.4,17 Conventional inorganic desiccants are exemplified by zeolites, silica gel, and hygroscopic salts.18 Strongly hydrophilic desiccants like zeolites typically exhibit Type I19 sorption isotherms with steep uptake at low RH (Scheme 1a, blue). Moderately hydrophilic desiccants such as silica gels that are optimized for dehumidification, e.g., Syloid AL-14 and Mobil Sorbead R,20 tend to exhibit more linear Type I isotherms with less uptake at low RH (Scheme 1a, red). Inorganic salts and mesoporous inorganics such as MCM-4121 tend to exhibit stepped or Type V19 isotherms, also with lower uptake at low RH (Scheme 1a, green). Most recently, the study of the water sorption properties of metal–organic frameworks, MOFs,22,232425−27 has resulted in families of rigid desiccants with Type V isotherms that exhibit steps at low RH (Scheme 1a, gold).28−31 In the context of AWH, rigid desiccants are exemplified by MOF-303,32 UiO-66,29 Al-fumarate,33 MOF-801,28 Co2Cl2BTDD,34 CAU-10(Al)-H,35 CAU-23-Al,36 Zr-Fumarate,37 Cr-soc-MOF-1,38 ROS-37,39,40 and ROS-39.41 Other rigid desiccants perform at higher RH values and so are more suited for passive IHC, as exemplified by Y-shp-MOF-511 and MIL-100(Fe).7 Desiccants with low uptake at low RH are unlikely to be suitable for AWH. Further, whereas zeolites are well-suited to adsorb water vapor at very low RH levels, they are poorly suited for AWH or IHC because of the high energy required for desorption.42,43 An ideal desiccant for AWH44 or passive IHC38 would exhibit a water vapor isotherm with a steep humidity-triggered step at <30% or ca. 60% RH respectively, with little or no hysteresis for AWH and a desorption branch below 45% RH for passive IHC. Unfortunately, AWH and IHC are usually mutually exclusive in that a desiccant is unlikely to exhibit dual purpose performance parameters.

Scheme 1. (a) Schematic Illustration of Characteristic Water Vapor Isotherm Shapes of Rigid Desiccants and Characteristic Water Vapor Isotherm Shapes of Flexible Desiccants (b) Type F-IVS (Single Step at Low RH), (c) Type F-IVS (Single Step at Moderate RH), and (d) Type F-IVm (Multistep) Isotherm.

Type I (strongly hydrophilic, blue); Type I (moderately hydrophilic, red); Type V (step at high RH, green); Type V (step at low RH, gold).

The powder blue and pink regions of each diagram are the RH ranges of interest for AWH and IHC, respectively.

Nonrigid or structurally flexible materials can also exhibit stepped isotherms driven by a different mechanism: water-induced phase transformation(s) of nonporous (closed pore, CP) to large pore (LP) transformations45−47 can afford single-step type F-IVS isotherms48 (F = flexible, S = single step, Scheme 1b (left, middle), and CP to narrow pore (NP) to LP phases can result in Type F-IVm sorption isotherms49 (Scheme 1b, right) that, to our knowledge, do not exist in traditional inorganic desiccants. Once again, dual purpose performance is out of reach. Flexible metal–organic materials (FMOMs) with two water-induced phase transformations at appropriate RH values would be ideal candidates to serve as dual-purpose sorbents. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, none have yet been reported. As a part of our interest in the dynamic behavior of porous solids,48 we were motivated to investigate the water sorption properties of the previously reported FMOM [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] (Hbtca = 1H-benzotriazole-5-carboxylic acid), which undergoes several phase transformations induced by gas adsorption/desorption.50,51 Herein, we report a detailed investigation of the water sorption properties and dynamic behavior of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2], which was previously reported to exhibit indications of humidity-induced transformations.52 Our study reveals that LP–NP–LP transformations occurred during water uptake, leading to two steps in its water vapor sorption isotherm. Importantly, the two steps are at thresholds suitable for AWH and passive IHC, respectively. Insight into the observed water sorption behavior is provided by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD), variable-temperature powder X-ray diffraction (VT-PXRD) and computational experiments.

Single crystals of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] were obtained by solvothermal reaction of H2btca and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and H2O following a reported procedure.50 Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of the as-synthesized crystals revealed DMF and H2O molecules within its pores, in agreement with the previously reported crystal structure.50 [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2]·DMF·4H2O (herein referred to as LP-α) adopted space group C2/c with unit cell parameters a = 18.5505(7) Å, b = 11.6548(5) Å, and c = 11.0031(4) Å (Table S1). Bulk phase purity was established using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD, Figure S1).

Previous reports concerning [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] studied its gas sorption properties50−52 but did not address water-induced phase transformation even though activated crystals exposed to the atmosphere during handling were reported to form a hydrated phase.52 We found that immersion of LP-α crystals in H2O (3 × 72 h, 323 K) afforded an unreported hydrate [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2]·8H2O (herein referred to as LP-γ, Figure 1a) that is isostructural to LP-α, with a similar PXRD pattern to LP-α. (Figure S1). Four symmetry independent H2O molecules (O1W–O4W, see ESI for details) disordered over two positions (major component A and minor component B) occupy the cavities that have a pore limiting diameter dlim = 4.9 Å and maximum cavity diameter dmax = 5.9 Å. The water molecules of hydration form a hydrogen-bonded chain with the OH2O···OH2O distances ranging from 2.439 to 3.004 Å (Table S2). Three of the four symmetry independent water molecules (O1W–O3W) form H-bonds with either the bridging hydroxo (O1WA···O3 = 2.830 Å) or carboxyl groups (O2WA···O14 = 3.010 Å, O3WA···O15 = 3.183 Å) of the host framework. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Figure S2) of LP-γ revealed two mass loss event of 12 wt % (4 molecules/formula unit) with onset temperatures of 311 and 348 K, respectively. Single crystallinity was retained during heating, allowing for structure determination by SCXRD, which revealed that the first water loss at 311 K afforded the previously reported tetrahydrate,[Zn3(OH)2(btca)2]·4H2O (hereinafter referred to as NP, Figure 1b).

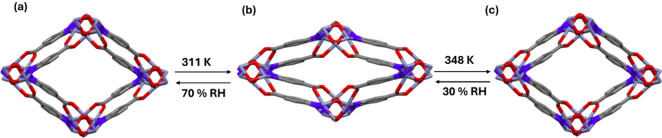

Figure 1.

Reversible LP-NP-LP water-induced structural transformations exhibited by [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2]: (a) LP-γ, (b) NP, and (c) LP-β.

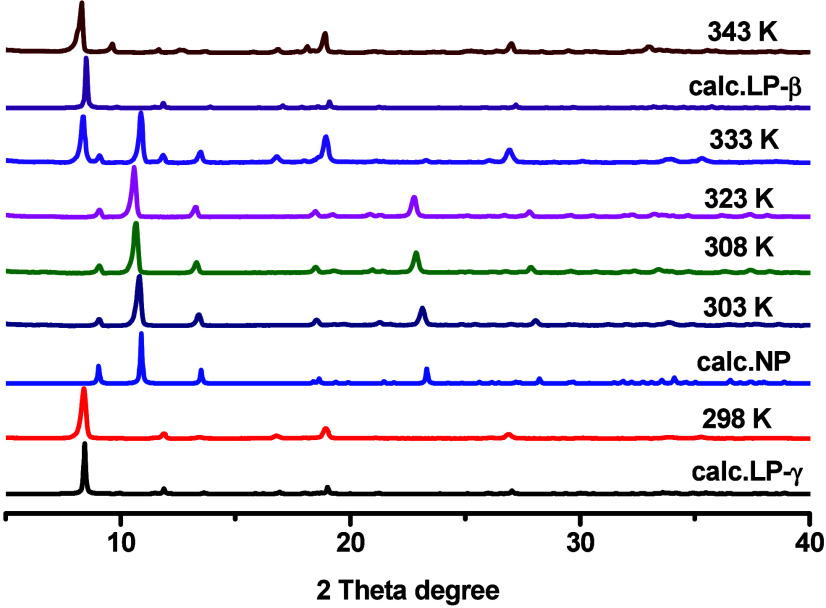

The single-crystal-to-single-crystal (SC–SC) transformation from LP-γ to NP resulted in contraction along the crystallographic b-axis with concomitant expansion along the a-axis (dlim = 2.77 Å and dmax = 3.50 Å, Table S1). A different PXRD pattern with strong peaks shifted to higher 2θ values being observed, indicating a structural transformation to a smaller unit cell (Figure.S1). This phase transformation was also studied in a powdered sample by using VT-PXRD (Figure 2). Water molecules in NP H-bond with the host and the other water molecules (Table S3): hydroxo (O1WA···O3 = 2.740 Å) and carboxyl groups (O2WA···O14 = 2.839 Å, O2WA···O15 = 3.073 Å) and water–water interactions (O1WA··· O2WA = 2.741 Å, O2WA··· O2WA = 3.133 Å); further hydrogen bond interactions are summarized in Figure S3. Heating an NP crystal on the SCXRD goniometer at 373 K resulted in transformation to the anhydrate phase LP-β. The NP → LP-β phase transformation resulted in expansion along the crystallographic a-axis with concomitant contraction along the b-axis (dlim = 5.29 Å and dmax = 6.53 Å, Table S1). The absence of electron density in the difference electron density maps (Figure S4) and TGA indicate that LP-β is guest-free. Notably, the reverse transformation occurred within minutes under ambient conditions (ca. 50% RH, 298 K), indicating reversibility. Such LP–NP–LP transformations are counterintuitive and rare in FMOMs, MIL-53 being the prototypal example.53,54 As discussed below, this phenomenon can be attributed to an induced fit mechanism of water binding.55,56

Figure 2.

VT-PXRD diffractograms of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] collected under air.

To gain additional insight into the water induced phase transformations of LP-β, NP, and LP-γ, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy experiments were conducted. The anhydrous phase, LP-β, was prepared by heating the as-synthesized powdered sample of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] at 373 K under a dynamic vacuum (1 mbar) for 12 h and kept under dry N2 to prevent exposure to moisture during handling and data collection. The absence of broad peaks in the range 3700–2700 cm–1 of the FTIR spectrum of LP-β (Figure S5a) indicate dehydration,57 whereas the sharp, low-intensity peak at 3654 cm–1 corresponds to the bridging hydroxyl group (μ2-OH).57,58 If nanoconfined water had been present then sharp peaks would have been expected.59 The hydrous NP phase was studied under a laboratory atmosphere (44% RH and 293 K measured using a diagnostic psychrometer), conditions that are consistent with its generation (Figure 3). After 1 min of exposure, a broad peak centered at 3391 cm–1 appeared, consistent with water adsorption.57 The relative peak intensity increased at 2 min, and no further changes were observed after 3 and 20 min of exposure, indicating that adsorption to the NP phase was complete within 2 min. This rapid uptake is relatively fast and in line with the inflection in the isotherm (Figure 3). Another difference between the FTIR spectra of the LP-β and NP phases was the presence of a peak at 743 cm–1 in LP-β corresponding to a Caromatic–H bending frequency from the btca ligand. This peak disappeared during hydration, perhaps because of the changed environment of the Caromatic–H moieties following water adsorption. A peak at 1548 cm–1 in the LP-β spectrum and 1545 cm–1 in the NP spectrum is attributed to the deprotonated (O–C–O)− moiety from the btca ligand (Figure S5b).

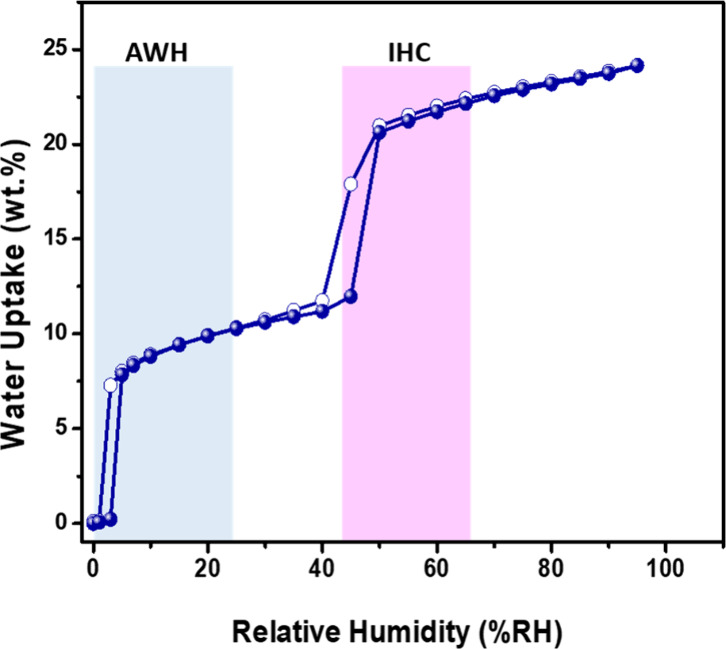

Figure 3.

Water vapor sorption isotherm collected (300 K) by dynamic vapor sorption (DVS).

LP-γ was prepared by storage in a desiccator at 84% RH (KCl salt solution, 293 K) for 1 h. The most notable difference in the IR spectrum is an increase in the relative peak intensity of water60 and a slight shift in this peak with respect to that of NP (3381 cm–1 vs 3374 cm–1). No other significant peak shifts during the water vapor induced phase changes were noted.

To further investigate the water sorption properties of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2], dynamic water vapor sorption (DVS) experiments were conducted after activating a microcrystalline sample of LP-γ under dry air flow at 373 K, thereby inducing the transformation to LP-β. The water vapor sorption isotherm (Figure 3) was collected at 300 K and contains two steps at 5% and 47% RH with uptakes of ca. 7.8 and 20.6 wt %, respectively, and the maximum water uptake was observed to be 24.5 wt % at 95% RH. These uptakes are consistent with the TGA and SCXRD data. The isotherm collected at 333 K revealed a shift of the inflection point to RH 8% and 52% RH, respectively (Figure S6). The profile of the water sorption isotherm corresponds to a Type F-IVm isotherm,49 but the LP–NP–LP mechanism does not involve the characteristic closed pore (CP) to NP to LP transitions typical of a material that undergoes two phase transformations.49 Interestingly, desorption revealed little hysteresis and the release of adsorbed water molecules at 0% RH without heating. Hydrolytic stability tests conducted upon a powdered sample of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] subjected to 100 hydration–dehydration cycles between 0 and 60% RH at 300 K revealed retention of water sorption capacity (Figure S7) and exhibit hydrolytic stability as evidenced by PXRD before and after the cycling experiment (Figure.S8). [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] therefore meets the criteria as a dual purpose ROS for AWH and passive IHC with inflection points at appropriate RH ranges suitable for both technologies. Our review of the literature revealed only 7 MOFs with multistep water vapor isotherms: MIL-100(Fe),31 MIL-101 (Cr),61 MIL-101-NH2,61 MIL-101-SO3H,61 [Mn(imH)]2[Mo(CN)8],62 [FeII(prentrz)2PdII(CN)4],63 and MIL-53(Cr),53,54 (see Table S4). Out of these, only [Mn(imH)]2[Mo(CN)8], [FeII(prentrz)2PdII(CN)4], and MIL-53(Cr) are driven by water-induced structural transformations. Specifically, a Prussian Blue analogue [Mn(imH)]2[Mo(CN)8] underwent a breathing mechanism due to water inclusion, a Hofmann structure [FeII(prentrz)2 PdII(CN)4] transformed through a flexible ligand and layer sliding, whereas MIL-53(Cr) underwent induced fit.58,64−66 MIL-53(Cr) is an outlier in that its guest-free phase is LP, contracting upon water loading to an NP phase through an induced fit mechanism,54 before expanding to the same LP structure at higher RH. These existing MOFs with multistep water sorption isotherms are unsuited for dual purpose AWH and passive IHC because the threshold RH values for their steps meet the criteria for only one application (see Table S4).

Rates of water adsorption/desorption are key performance parameters with respect to assessing utility in water harvesting.4,32,67,68 For FMOMs, water vapor sorption kinetics are rarely reported.60,69−72 Our group has recently developed and reported an isotherm-based kinetics model4 that links water vapor sorption thermodynamics with kinetics and explains differences in sorption kinetics for various sorbents, including structurally rigid sorbents such as ROS-037,39 ROS-039,41 ROS-040,73 MOF-303,67 MIL-160,74 CAU-10-H,75 and Al-fumarate76 as well as flexible sorbents such as X-dia-2-Cd.69 Interestingly, for 2-stepped isotherms as exhibited by [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2], the model4 was found to predict two distinct rates of adsorption, as seen for the adsorption kinetics of MIL-101(Cr)77 and the desorption kinetics of [[Mn(imH)]2[Mo(CN)8]]n.62 Indeed, humidity swing experiments were conducted on [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] from 0 to 60% RH at 298 K (see Figure S9), and we observed two distinct water vapor sorption rates (Figure 4a). During the adsorption phase, there was initial fast loading followed by slower adsorption loading. Similarly, during desorption, we observed fast unloading followed by slower unloading. These kinetic profiles were fitted using our isotherm-based kinetics model (Figure 4b), further supporting the validity of the model.4 In a separate RH-swing experiment conducted from 0 to 30% RH at 298 K, corresponding to the low RH step in the [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] isotherm, the kinetics exhibited a constant rate for both adsorption and desorption. For a 5.6 mg sample, adsorption was complete within 15 min, while desorption required 80 min (Figure 4c). This experimental kinetics data is also consistent with our kinetics model (Figure 4d).4 With regards to the sorption mechanism, sorption kinetics tends to be limited by diffusion of water vapor to the sorption bed.4 Therefore, the position and profile of the inflection are the key factors that impact adsorption kinetics rather than whether adsorption occurs by pore condensation or structural transformation(s).78

Figure 4.

Above: (a) 0–60% RH humidity swing kinetics data collected at 300 K on 5.6 mg of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2]; (b) 0–60% RH humidity swing kinetics observed (blue) vs calculated using an isotherm-based kinetics model4 (orange); Below: (c) 0–30% RH humidity swing kinetics data collected at 300 K on 5.6 mg of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2]; (d) 0–30% RH humidity swing kinetics observed (blue) vs calculated using the same model4 (orange).

The LP–NP–LP mechanism can be rationalized by evaluating the level of distortion of the coordination environment of the metal during the structural transformations that occurred during hydration. During the transformation from LP-β → NP → LP-γ, the relative positions of the Zn and hydroxo atoms in the rod building block that is the backbone of the network structure remained relatively unchanged despite considerable contraction and subsequent expansion along the b axis (Figure S10). Instead, the framework flexibility is enabled by changes in the carboxyl and triazolate coordination geometries. The extent of bond distortion can be assessed by structural changes in the framework, specifically the angles δ1 (centroid c1–N5–Zn1, Figure S10c) and δ2 (centroid c2–centroid c3–C10, Figure S10d). These ligating moieties tend to form coordination bonds that have δ1 and δ2 values near 180°. The most obtuse angles were observed for LP-β with δ1 = 166.22° and δ2 = 164.79° whereas NP exhibited more acute angles, δ1 = 150.73° and δ2 = 141.69°, an indication of strain. However, the existence of this phase indicates that the energy gained by the H-bonded network of water molecules can overcome the geometric strain of the Zn–Ntriazolate and Zn–Ocarboxyl coordination bonds. Such distortions were also observed for the LP–NP transformation in MIL-53(Cr) during water loading.55 Further water uptake from NP to LP-γ relieves this distortion, with δ1 = 162.84° and δ2 = 154.31°. This analysis suggests that both NP and LP-γ distort to adapt to the optimal geometry of the H-bond network through an induced fit mechanism. Overall, water adsorption by LP-β resulted in a phase transformation that involved contraction by 24% of the unit cell volume to form NP. This compares to the unit cell volume reduction of 45% in MIL-53. It is reasonable to assert that the induced fit NP–LP transformation can be attributed to water–pore wall interactions that overcome the inherently strained structure of NP. There are also examples of torsional freedom in a linker ligand resulting in enhanced host–guest interactions through a different induced fit mechanism.79

To further evaluate the asserted induced fit mechanism and resultant water sorption isotherm profile of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2], we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations and grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations. Different crystal structures (structures 0–13) were selected from DFT minimum energy pathways of the empty host material between unit cell volumes ranging incrementally from 1939.72 to 2669.51 Å3 (see Table S6 and ESI for details). Adsorption isotherms were calculated for each of the 14 structures using GCMC simulations (Figure S13). Type I80 adsorption isotherms were observed for structures 0 to 6 with unit cell volumes between 1939.72 and 2281.735 Å3 (Table S6); this profile is characteristic of a unimolecular layer within the pore.80 By further increasing the unit cell volume from 2334.673 to 2669.54 Å3 (structures 7 to 13, Table S6), the profile of the simulated isotherms became S-shaped (Figure S13). Using the simulated isotherms in Figure S13, a contour plot representing each simulated structure (unit cell volume) with respect to changing RH was constructed (Figure 5). This plot was used to identify the phase transformation landscape of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] during water loading. For each RH value in the experimental isotherm, the most probable structure was determined by correlating experimental uptake with the uptake from the simulated isotherms. Starting with empty LP-β at 0% RH (structure 8), the uptake at first loading (4.03% RH) corresponds to structure 3 with a similar cell volume to NP. Further loading (6.12% RH) results in a small cell volume expansion and correlates to structure 4. This phase is maintained until 30.16% RH. Upon further increase in RH, the unit cell volume expands corresponding to most probable structures 5, 9, and 11 at RH values of 36–41.5%, 45.12%, and 51.02% RH, respectively. LP-γ (structure 11) is the predominant phase for >51.02% RH.

Figure 5.

Contour plot representing GCMC simulated H2O adsorption isotherms (uptake is color coded) for each of the 14 crystal structures determined from DFT calculations. The black circles/lines represent the unit cell volume of the most probable structure at the specified experimental uptake and RH.

The DFT calculations indicate that the relative energy of the LP-β (structure 10) is −45.59 kJ/mol lower than that of NP (structure 0) which we can attribute to the strain in NP discussed above. Analysis of the experimental and simulated crystal structures thereby allows us to assert that the energy gained from hydrogen bonding interactions between water molecules and the framework of NP can indeed overcome the inherently strained structure of NP. Further loading of water molecules enables LP-γ to be energetically favored over NP above ca. 50% RH. The average adsorption energy at the DFT (BEEF-vdW) level stays within the range from −60 to −50 kJ/mol per water during the loading of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] (Table S7), with hydrogen bond networks visualized for four relevant water loadings in Figure S14. Furthermore, an energy decomposition analysis of the adsorption energies shows that water–host interactions are dominant at low water loading (low unit cell volumes) and are being surpassed by water–water interactions at higher water loadings in LP phases.

In conclusion, we report the water-induced structural transformations of [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2], an FMOM that underwent atypical LP–NP–LP structural transformations triggered by increasing RH. To our knowledge, this is only the second example of such a two-step transformation after MIL-53. Our work offers two main take home messages. First, with regards to design of FMOMs, induced fit behavior can be governed by at least two mechanisms: torsional freedom in a linker ligand, as seen in sql-SIFSIX-bpe-Zn, can enable a more strained NP phase that is stabilized by enhanced host–guest binding; here we reveal that strain in an NP phase of a sorbent with relatively rigid ligands and RBBs can be overcome by a combination of guest–guest and host–guest interactions, also resulting in induced fit. Second, this work further points toward the potential utility of FMOMs in water harvesting and dehumidification applications, which is much less recognized than for rigid sorbents. Indeed, to our knowledge the first example of an FMOM that offers relatively fast kinetics, hydrolytic stability, small hysteresis, and a step at low RH was only reported in 2023 by us.69 This study goes “one step further” than our previous work by detailing the first example of a water sorbent of any type that exhibits a 2-step water sorption isotherm that meets the performance criteria needed to serve as a dual purpose water vapor sorbent thanks to steps suitable for both AWH (5% RH) and passive IHC (47% RH). Nevertheless, there is no expectation that a two-step sorbent such as [Zn3(OH)2(btca)2] will offer better performance for either AWH or IHC when compared to a single-step sorbent with a step at an appropriate threshold. This is because the low RH step would not be in play under typical IHC conditions whereas the intermediate RH step should not occur under AWH (low RH) conditions.

Acknowledgments

M.J.Z. gratefully acknowledges the support from the Irish Research Council (IRCLA/2019/167), the European Research Council (ADG 885695), and Research Ireland (16/IA/4624). S.J.N. and M.V. acknowledge the Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC) for the provision of computational facilities and support. S.J.N. is grateful for support by Enterprise Ireland and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (Grant Agreement No. 847402, Project ID: MF20210297).

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2328383-2328385 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this work. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: + 44 1223 336033.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.4c02019.

Details of synthetic procedures and analytical testing methods, additional crystallographic parameters and analysis, supporting figures, details of computational methodology, and supporting references (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. CRediT: S.M.S, A.A.B, A.C.E: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing-original draft, review and editing; D.S, S.-Q. W., V. N., S.D.: investigation, writing-review and editing; S.J.N, M. V: formal analysis, writing-review and editing; M. Z.: funding acquisition, formal analysis, writing-review and editing. CRediT: Samuel M. Shabangu conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mekonnen M. M.; Hoekstra A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci.Adv. 2016, 2 (2), e1500323. 10.1126/sciadv.1500323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y.; Wang R.; Zhang Y.; Wang J. Progress and Expectation of Atmospheric Water Harvesting. Joule 2018, 2 (8), 1452–1475. 10.1016/j.joule.2018.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Rao S. R.; Kapustin E. A.; Zhao L.; Yang S.; Yaghi O. M.; Wang E. N. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting device for arid climates. Nat.Commun. 2018, 9, 1191. 10.1038/s41467-018-03162-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezrukov A. A.; O’Hearn D. J.; Gascon-Perez V.; Darwish S.; Kumar A.; Sanda S.; Kumar N.; Francis K.; Zaworotko M. J. Metal-organic frameworks as regeneration optimized sorbents for atmospheric water harvesting. Cell Rep.Phys.Sci. 2023, 4 (2), 101252. 10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmutzki M. J.; Diercks C. S.; Yaghi O. M. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Water Harvesting from Air. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30 (37), 1704304. 10.1002/adma.201704304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapotin A.; Kim H.; Rao S. R.; Wang E. N. Adsorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting: Impact of Material and Component Properties on System-Level Performance. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52 (6), 1588–1597. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y. K.; Yoon J. W.; Lee J. S.; Hwang Y. K.; Jun C. H.; Chang J. S.; Wuttke S.; Bazin P.; Vimont A.; Daturi M.; et al. Energy-Efficient Dehumidification over Hierachically Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks as Advanced Water Adsorbents. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24 (6), 806–810. 10.1002/adma.201104084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La D.; Dai Y. J.; Li Y.; Wang R. Z.; Ge T. S. Technical development of rotary desiccant dehumidification and air conditioning: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14 (1), 130–147. 10.1016/j.rser.2009.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla A.; Candido C.; Gocer O. Indoor air quality and early detection of mould growth in residential buildings: a case study. UCL Open Environment 2022, 10.14324/111.444/ucloe.000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier T.; Coutand M.; Bertron A.; Roques C. A review of indoor microbial growth across building materials and sampling and analysis methods. Building and Environment 2014, 80, 136–149. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhalim R. G.; Bhatt P. M.; Belmabkhout Y.; Shkurenko A.; Adil K.; Barbour L. J.; Eddaoudi M. A Fine-Tuned Metal–Organic Framework for Autonomous Indoor Moisture Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (31), 10715–10722. 10.1021/jacs.7b04132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrestani Z.; Sadeghzadeh S.; Motejadded Emrooz H. B. An overview of atmospheric water harvesting methods, the inevitable path of the future in water supply. RSC Adv. 2023, 13 (15), 10273–10307. 10.1039/D2RA07733G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng A.; Akther N.; Duan X.; Peng S.; Onggowarsito C.; Mao S.; Fu Q.; Kolev S. D. Recent Development of Atmospheric Water Harvesting Materials: A Review. ACS Mater. Au 2022, 2 (5), 576–595. 10.1021/acsmaterialsau.2c00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Lu H.; Zhao F.; Yu G. Atmospheric Water Harvesting: A Review of Material and Structural Designs. Acs.Mater.Lett. 2020, 2 (7), 671–684. 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.0c00130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L.; Dang Y.; Wang Y.; Chen K.-J. Recent advances in metal–organic frameworks for water absorption and their applications. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8 (5), 1171–1194. 10.1039/D3QM00484H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.; Kirlikovali K. O.; Chen Z.; Farha O. K. Metal-organic frameworks for water vapor adsorption. Chem. 2024, 10 (2), 484–503. 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikel N.; Prévot M. S.; Yaghi O. M. MOF water harvesters. Nat.Nanotechnol. 2020, 15 (5), 348–355. 10.1038/s41565-020-0673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng E. P.; Mintova S. Nanoporous materials with enhanced hydrophilicity and high water sorption capacity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114 (1–3), 1–26. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sing K. S. W.; Everett D. H.; Haul R. A. W.; Moscou L.; Pierotti R. A.; Rouquerol J.; Siemieniewska T. Reporting Physisorption Data for Gas Solid Systems with Special Reference to the Determination of Surface-Area and Porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57 (4), 603–619. 10.1351/pac198557040603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram E. O.; Hines A. L. Pure vapor adsorption of water on Mobil Sorbead R silica gel. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1983, 28 (1), 11–14. 10.1021/je00031a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn P.; Schüth F.; Grillet Y.; Rouquerol F.; Rouquerol J.; Unger K. Water sorption on mesoporous aluminosilicate MCM-41. Langmuir 1995, 11 (2), 574–577. 10.1021/la00002a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. J. IV; Perman J. A.; Zaworotko M. J. Design and synthesis of metal–organic frameworks using metal–organic polyhedra as supermolecular building blocks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38 (5), 1400. 10.1039/b807086p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. R.; Zheng Y.-R.; Stang P. J. Metal–Organic Frameworks and Self-Assembled Supramolecular Coordination Complexes: Comparing and Contrasting the Design, Synthesis, and Functionality of Metal–Organic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113 (1), 734–777. 10.1021/cr3002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa S.; Kitaura R.; Noro S.-I. Functional Porous Coordination Polymers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43 (18), 2334–2375. 10.1002/anie.200300610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-C.; Long J. R.; Yaghi O. M. Introduction to Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112 (2), 673–674. 10.1021/cr300014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Férey G. Hybrid porous solids: past, present, future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37 (1), 191–214. 10.1039/B618320B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hearn D. J.; Bajpai A.; Zaworotko M. J. The “Chemistree” of Porous Coordination Networks: Taxonomic Classification of Porous Solids to Guide Crystal Engineering Studies. Small 2021, 17 (22), 2006351. 10.1002/smll.202006351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Yaghi O. M. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Water Harvesting from Air, Anywhere, Anytime. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6 (8), 1348–1354. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H.; Gándara F.; Zhang Y.-B.; Jiang J.; Queen W. L.; Hudson M. R.; Yaghi O. M. Water Adsorption in Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks and Related Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (11), 4369–4381. 10.1021/ja500330a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtch N. C.; Jasuja H.; Walton K. S. Water Stability and Adsorption in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (20), 10575–10612. 10.1021/cr5002589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küsgens P.; Rose M.; Senkovska I.; Fröde H.; Henschel A.; Siegle S.; Kaskel S. Characterization of metal-organic frameworks by water adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 120 (3), 325–330. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikel N.; Prevot M. S.; Fathieh F.; Kapustin E. A.; Lyu H.; Wang H. Z.; Diercks N. J.; Glover T. G.; Yaghi O. M. Rapid Cycling and Exceptional Yield in a Metal-Organic Framework Water Harvester. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5 (10), 1699–1706. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremias F.; Fröhlich D.; Janiak C.; Henninger S. K. Advancement of sorption-based heat transformation by a metal coating of highly-stable, hydrophilic aluminium fumarate MOF. RSC Adv. 2014, 4 (46), 24073–24082. 10.1039/C4RA03794D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieth A. J.; Yang S.; Wang E. N.; Dincă M. Record Atmospheric Fresh Water Capture and Heat Transfer with a Material Operating at the Water Uptake Reversibility Limit. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3 (6), 668–672. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange M. F.; Zeng T.; Vlugt T. J. H.; Gascon J.; Kapteijn F. Manufacture of dense CAU-10-H coatings for application in adsorption driven heat pumps: optimization and characterization. CrystEngComm 2015, 17 (31), 5911–5920. 10.1039/C5CE00789E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen D.; Zhao J.; Ernst S.-J.; Wahiduzzaman M.; Ken Inge A.; Fröhlich D.; Xu H.; Bart H.-J.; Janiak C.; Henninger S. A metal–organic framework for efficient water-based ultra-low-temperature-driven cooling. Nat.Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 3025. 10.1038/s41467-019-10960-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K. H.; Mileo P. G. M.; Lee J. S.; Lee U. H.; Park J.; Cho S. J.; Chitale S. K.; Maurin G.; Chang J.-S. Defective Zr-Fumarate MOFs Enable High-Efficiency Adsorption Heat Allocations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (1), 1723–1734. 10.1021/acsami.0c15901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towsif Abtab S. M.; Alezi D.; Bhatt P. M.; Shkurenko A.; Belmabkhout Y.; Aggarwal H.; Weseliński Ł. J.; Alsadun N.; Samin U.; Hedhili M. N.; et al. Reticular Chemistry in Action: A Hydrolytically Stable MOF Capturing Twice Its Weight in Adsorbed Water. Chem. 2018, 4 (1), 94–105. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rather B.; Zaworotko M. J. A 3D metal-organic network, [Cu2(glutarate)2(4,4′-bipyridine)], that exhibits single-crystal to single-crystal dehydration and rehydrationElectronic supplementary information (ESI) available: experimental details, IR, TGA and XRPD of all compounds. See ht. Chem. Commun. 2003, 7, 830–831. 10.1039/b301219k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaworotko M. J.; Pérez V. G.; Bezrukov A. A.; O’Hearn D. J.; Wang S.. Water capture methods, devices, and compounds. U.S. Patent US20200030737A1, 2020.

- Goforth A. M.; Su C. Y.; Hipp R.; Macquart R. B.; Smith M. D.; zur Loye H.-C. Connecting small ligands to generate large tubular metal-organic architectures. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178 (8), 2511–2518. 10.1016/j.jssc.2005.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Salles F.; Zajac J. A Critical Review of Solid Materials for Low-Temperature Thermochemical Storage of Solar Energy Based on Solid-Vapour Adsorption in View of Space Heating Uses. Molecules 2019, 24 (5), 945. 10.3390/molecules24050945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Cho H. J.; Narayanan S.; Yang S.; Furukawa H.; Schiffres S.; Li X.; Zhang Y.-B.; Jiang J.; Yaghi O. M.; Wang E. N. Characterization of adsorption enthalpy of novel water-stable zeolites and metal-organic frameworks. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6 (1), 19097. 10.1038/srep19097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmutzki M. J.; Diercks C. S.; Yaghi O. M. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Water Harvesting from Air. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30 (37), 1704304. 10.1002/adma.201704304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneemann A.; Bon V.; Schwedler I.; Senkovska I.; Kaskel S.; Fischer R. A. Flexible metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (16), 6062–6096. 10.1039/C4CS00101J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-C. J.; Kitagawa S. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (16), 5415–5418. 10.1039/C4CS90059F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa S.; Uemura K. Dynamic porous properties of coordination polymers inspired by hydrogen bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34 (2), 109. 10.1039/b313997m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. Y.; Lama P.; Sen S.; Lusi M.; Chen K. J.; Gao W. Y.; Shivanna M.; Pham T.; Hosono N.; Kusaka S.; et al. Reversible Switching between Highly Porous and Nonporous Phases of an Interpenetrated Diamondoid Coordination Network That Exhibits Gate-Opening at Methane Storage Pressures. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (20), 5684–5689. 10.1002/anie.201800820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-Q.; Mukherjee S.; Zaworotko M. J. Spiers Memorial Lecture: Coordination networks that switch between nonporous and porous structures: an emerging class of soft porous crystals. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 231, 9–50. 10.1039/D1FD00037C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J.; Wu Y.; Li M.; Liu B.-Y.; Huang X.-C.; Li D. Crystalline Structural Intermediates of a Breathing Metal-Organic Framework That Functions as a Luminescent Sensor and Gas Reservoir. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19 (6), 1891–1895. 10.1002/chem.201203515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H.; Xie M.; Huang Y. L.; Zhao Y. F.; Xie X. J.; Bai J. P.; Wan M. Y.; Krishna R.; Lu W. G.; Li D. Induced Fit of C2H2 in a Flexible MOF Through Cooperative Action of Open Metal Sites. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (25), 8515–8519. 10.1002/anie.201904160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero-Antonino M.; Remiro-Buenamañana S.; Souto M.; García-Valdivia A. A.; Choquesillo-Lazarte D.; Navalón S.; Rodríguez-Diéguez A.; Mínguez Espallargas G.; García H. Design of cost-efficient and photocatalytically active Zn-based MOFs decorated with Cu2O nanoparticles for CO2methanation. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (73), 10932–10935. 10.1039/C9CC04446A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourrelly S.; Moulin B.; Rivera A.; Maurin G.; Devautour-Vinot S.; Serre C.; Devic T.; Horcajada P.; Vimont A.; Clet G.; et al. Explanation of the Adsorption of Polar Vapors in the Highly Flexible Metal Organic Framework MIL-53(Cr). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (27), 9488–9498. 10.1021/ja1023282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles F.; Bourrelly S.; Jobic H.; Devic T.; Guillerm V.; Llewellyn P.; Serre C.; Ferey G.; Maurin G. Molecular Insight into the Adsorption and Diffusion of Water in the Versatile Hydrophilic/Hydrophobic Flexible MIL-53(Cr) MOF. J.Phys.Chem.C 2011, 115 (21), 10764–10776. 10.1021/jp202147m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Férey G.; Serre C. Large breathing effects in three-dimensional porous hybrid matter: facts, analyses, rules and consequences. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38 (5), 1380–1399. 10.1039/b804302g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devic T.; Horcajada P.; Serre C.; Salles F.; Maurin G.; Moulin B.; Heurtaux D.; Clet G.; Vimont A.; Grenèche J.-M.; et al. Functionalization in Flexible Porous Solids: Effects on the Pore Opening and the Host–Guest Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (3), 1127–1136. 10.1021/ja9092715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Han R.; Lu S.; Liu Q. A metal-OH group modification strategy to prepare highly-hydrophobic MIL-53-Al for efficient acetone capture under humid conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 107, 111–123. 10.1016/j.jes.2021.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau T.; Serre C.; Huguenard C.; Fink G.; Taulelle F.; Henry M.; Bataille T.; Ferey G. A rationale for the large breathing of the porous aluminum terephthalate (MIL-53) upon hydration. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10 (6), 1373–1382. 10.1002/chem.200305413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcañiz-Monge J.; Linares-Solano A.; Rand B. Water Adsorption on Activated Carbons: Study of Water Adsorption in Micro- and Mesopores. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105 (33), 7998–8006. 10.1021/jp010674b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Sensharma D.; Nikolayenko V. I.; Darwish S.; Bezrukov A. A.; Kumar N.; Liu W.; Kong X.-J.; Zhang Z.; Zaworotko M. J. Structural Phase Transformations Induced by Guest Molecules in a Nickel-Based 2D Square Lattice Coordination Network. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35 (2), 783–791. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c03662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama G.; Matsuda R.; Sato H.; Hori A.; Takata M.; Kitagawa S. Effect of functional groups in MIL-101 on water sorption behavior. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 157, 89–93. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magott M.; Gaweł B.; Sarewicz M.; Reczyński M.; Ogorzały K.; Makowski W.; Pinkowicz D. Large breathing effect induced by water sorption in a remarkably stable nonporous cyanide-bridged coordination polymer. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (26), 9176–9188. 10.1039/D1SC02060A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J.-P.; Hu Y.; Zhao B.; Liu Z.-K.; Xie J.; Yao Z.-S.; Tao J. A spin-crossover framework endowed with pore-adjustable behavior by slow structural dynamics. Nat.Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 3510. 10.1038/s41467-022-31274-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat J. P. S.; Seymour V. R.; Griffin J. M.; Thompson S. P.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Fairen-Jimenez D.; Düren T.; Ashbrook S. E.; Wright P. A. A novel structural form of MIL-53 observed for the scandium analogue and its response to temperature variation and CO2 adsorption. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41 (14), 3937–3941. 10.1039/C1DT11729G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Mowat J. P. S.; Fairen-Jimenez D.; Morrison C. A.; Thompson S. P.; Wright P. A.; Düren T. Elucidating the Breathing of the Metal–Organic Framework MIL-53(Sc) with ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Simulations and in Situ X-ray Powder Diffraction Experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (42), 15763–15773. 10.1021/ja403453g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serre C.; Millange F.; Thouvenot C.; Nogues M.; Marsolier G.; Louer D.; Ferey G. Very large breathing effect in the first nanoporous chromium(III)-based solids:: MIL-53 or CrIII(OH)•{O2C-C6H4-CO2}•{HO2C-C6H4-CO2H}x•H2Oy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124 (45), 13519–13526. 10.1021/ja0276974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathieh F.; Kalmutzki M. J.; Kapustin E. A.; Waller P. J.; Yang J. J.; Yaghi O. M. Practical water production from desert air. Sci.Adv. 2018, 4 (6), eaat3198. 10.1126/sciadv.aat3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Yang S.; Rao S. R.; Narayanan S.; Kapustin E. A.; Furukawa H.; Umans A. S.; Yaghi O. M.; Wang E. N. Water harvesting from air with metal-organic frameworks powered by natural sunlight. Science 2017, 356 (6336), 430–432. 10.1126/science.aam8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subanbekova A.; Nikolayenko V. I.; Bezrukov A. A.; Sensharma D.; Kumar N.; O’Hearn D. J.; Bon V.; Wang S. Q.; Koupepidou K.; Darwish S.; et al. Water vapour and gas induced phase transformations in an 8-fold interpenetrated diamondoid metal-organic framework. J.Mater.Chem.A 2023, 11 (17), 9691–9699. 10.1039/D3TA01574B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M.; Mukherjee S.; Liang Y.-J.; Fang X.-D.; Zhu A.-X.; Zaworotko M. J. Water vapour induced reversible switching between a 1-D coordination polymer and a 0-D aqua complex. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (59), 8218–8221. 10.1039/D2CC02777A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; Wang S.-Q.; Liu Z.; Chen Y.; Zaworotko M. J.; Cheng P.; Ma J.-G.; Zhang Z. Fabrication of Moisture-Responsive Crystalline Smart Materials for Water Harvesting and Electricity Transduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (20), 7732–7739. 10.1021/jacs.1c01831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsobnang P. K.; Hastürk E.; Fröhlich D.; Wenger E.; Durand P.; Ngolui J. L.; Lecomte C.; Janiak C. Water Vapor Single-Gas Selectivity via Flexibility of Three Potential Materials for Autonomous Indoor Humidity Control. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19 (5), 2869–2880. 10.1021/acs.cgd.9b00097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su C.-Y.; Goforth A. M.; Smith M. D.; Pellechia P. J.; Zur Loye H.-C. Exceptionally Stable, Hollow Tubular Metal–Organic Architectures: Synthesis, Characterization, and Solid-State Transformation Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (11), 3576–3586. 10.1021/ja039022m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadiau A.; Lee J. S.; Damasceno Borges D.; Fabry P.; Devic T.; Wharmby M. T.; Martineau C.; Foucher D.; Taulelle F.; Jun C.-H.; et al. Design of Hydrophilic Metal Organic Framework Water Adsorbents for Heat Reallocation. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27 (32), 4775–4780. 10.1002/adma.201502418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinsch H.; Van Der Veen M. A.; Gil B.; Marszalek B.; Verbiest T.; De Vos D.; Stock N. Structures, Sorption Characteristics, and Nonlinear Optical Properties of a New Series of Highly Stable Aluminum MOFs. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25 (1), 17–26. 10.1021/cm3025445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaab M.; Trukhan N.; Maurer S.; Gummaraju R.; Muller U. The progression of Al-based metal-organic frameworks - From academic research to industrial production and applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 157, 131–136. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita K.; Hwang J.; Shamim J. A.; Hsu W. L.; Matsuda R.; Endo A.; Delaunay J. J.; Daiguji H. Kinetics of Water Vapor Adsorption and Desorption in MIL-101 Metal-Organic Frameworks. J.Phys.Chem.C 2019, 123 (1), 387–398. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b08211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezrukov A. A.; O’Hearn D. J.; Gascón-Pérez V.; Matos C. R. M. O.; Koupepidou K.; Darwish S.; Sanda S.; Kumar N.; Li X.; Shivanna M.; et al. Rapid determination of experimental sorption isotherms from non-equilibrium sorption kinetic data. Chem. 2024, 10 (5), 1458–1470. 10.1016/j.chempr.2024.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shivanna M.; Otake K. I.; Song B. Q.; Van Wyk L. M.; Yang Q. Y.; Kumar N.; Feldmann W. K.; Pham T.; Suepaul S.; Space B.; et al. Benchmark Acetylene Binding Affinity and Separation through Induced Fit in a Flexible Hybrid Ultramicroporous Material. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (37), 20383–20390. 10.1002/anie.202106263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue M. D.; Aranovich G. L. A new classification of isotherms for Gibbs adsorption of gases on solids. Fluid Phase Equilib. 1999, 158, 557–563. 10.1016/S0378-3812(99)00074-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2328383-2328385 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this work. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: + 44 1223 336033.