ABSTRACT

Influenza, as well as other respiratory viruses, can trigger local and systemic inflammation resulting in an overall “cytokine storm” that produces serious outcomes such as acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). We hypothesized that gene therapy platforms could be useful in these cases if the production of an anti-inflammatory protein reflects the intensity and duration of the inflammatory condition. The recombinant protein would be produced and released only in the presence of the inciting stimulus, avoiding immunosuppression or other unwanted side effects that may occur when treating infectious diseases with anti-inflammatory drugs. To test this hypothesis, we developed AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A, an inflammation-inducible cassette that remains innocuous in the absence of inflammation but releases HMGB1 Box A, an antagonist of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), in response to inflammatory stimuli such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or influenza virus infection. We report here that this novel inflammation-inducible HMGB1 Box A construct in a non-replicative adenovirus (AdV) vector mitigates lung and systemic inflammation therapeutically in response to influenza infection. We anticipate that this strategy will apply to the treatment of multiple diseases in which HMGB1-mediated signaling is a central driver of inflammation.

IMPORTANCE

Many inflammatory diseases are mediated by the action of a host-derived protein, HMGB1, on Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to elicit an inflammatory response. We have engineered a non-replicative AdV vector that produces HMGB1 Box A, an antagonist of HMGB1-induced inflammation, under the control of an endogenous complement component C3 (C3) promoter sequence, that is inducible by LPS and influenza in vitro and ex vivo in macrophages (Mϕ) and protects mice and cotton rats therapeutically against infection with mouse-adapted and human non-adapted influenza strains, respectively, in vivo. We anticipate that this novel strategy will apply to the treatment of multiple infectious and non-infectious diseases in which HMGB1-mediated TLR4 signaling is a central driver of inflammation.

KEYWORDS: TLR4, MD-2, HMGB1, Box A, influenza, LPS, mice, cotton rats, adenovirus

INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus infection causes serious disease worldwide and can lead to a massive death toll during pandemics, particularly, when followed by secondary bacterial infection (1–3). Prediction of which influenza strains to incorporate in each year’s vaccine, including unexpected strain dominance, has led to efforts to develop a “universal vaccine” (4–7). Antiviral drugs are limited by their need to be administered early after infection (8) and the appearance of drug-resistant strains (8, 9), although at a low frequency. Although the disease is initiated by influenza replication resulting in airway epithelial damage, the severe inflammatory response that follows metabolic stress in innate immune cells (e.g., Mϕ) elicits a “cytokine storm” that leads to acute lung injury (ALI) or the more severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (10, 11), also seen in SARS-CoV-2 (12).

Our initial finding that TLR4−/− mice are highly refractory to lethal influenza infection (13, 14) led to the hypothesis that TLR4 antagonist therapy would mitigate disease by blunting the “cytokine storm.” Eritoran (Eisai, Inc.), a potent lipid A analog antagonist that acts by competitive inhibition of the TLR4 co-receptor, MD-2 (14), failed in Phase 3 clinical trials for all-cause sepsis (15). However, we reasoned that influenza, which targets the lung and leads to a “cytokine storm,” might be more amenable to therapeutic TLR4 antagonism. Eritoran treatment of mice infected with an LD90 of mouse-adapted influenza strain A/PR/8/34 (PR8) starting 2 days post-infection (p.i.) for 5 days, blunted inflammatory cytokines and lung histopathology, with significant survival, even when treatment was delayed until 6 days p.i. (14, 16–19). These findings were confirmed in cotton rats (CR), Sigmodon hispidus, that, in contrast to mice, are susceptible to non-adapted human respiratory viruses (20–22). Eritoran treatment of mice or CR also blunted the enhanced disease observed when influenza is followed by secondary Gram-positive infection (23). We have since shown that many TLR4 antagonists that are structurally unrelated to Eritoran and act by distinct mechanisms are highly effective therapeutically in influenza-infected mice and CR (24). However, Eritoran synthesis is very complex (25, 26), and continuous or repeated i.v. dosing is required in murine or human endotoxicity, sepsis, and influenza infection (14, 26, 27).

Importantly, influenza does not express “pathogen-associated molecular patterns” (PAMPs) that activate TLR4. We found that influenza-induced lung inflammation and lethality are mediated by host-derived HMGB1 (17). HMGB1, a nuclear protein released from dying cells (28), was first identified as a key mediator of endotoxicity and sepsis (29–31). Like the prototype TLR4 PAMP, LPS, the disulfide-HMGB1 isoform is a “danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP)” that activates TLR4 signaling by binding the TLR4 co-receptor, MD-2 (32–36).

However, other mechanisms of TLR4-dependent HMGB1 signaling have been proposed via CD14 (37) or the HMGB1 receptor, receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (38). In contrast to TLR4−/− mice (13, 14, 39), both CD14−/− (14) and RAGE−/− mice succumb to PR8, although RAGE−/− mice exhibit an extended mean time to death (40; Fig. S1). Therefore, the direct HMGB1-MD-2 binding mechanism seemed most likely. To test this hypothesis, the treatment of mice therapeutically with P5779, a small molecule inhibitor that competitively inhibits HMGB1 binding to MD-2 and blocks TLR4 signaling (32, 34), protected PR8-infected mice comparably to Eritoran (17). However, the high concentrations of P5779 required for protection are not clinically achievable. In CR infected with human influenza strains, disease severity based on lung pathology and cytokine production correlated with serum HMGB1 levels, and were reduced by Eritoran treatment (23, 41). These data, and reports that HMGB1 underlies many other inflammatory diseases (42–49), suggest that HMGB1-mediated TLR4 signaling is a common denominator.

HMGB1 contains two ~80 amino acid domains, Box A and Box B (50). Box A binds TLR4 and stabilizes the interaction of Box B with MD-2 that triggers TLR4-dependent cytokine-stimulating activity of intact HMGB1 (34). Recombinant HMGB1 Box A (rBox A) competitively inhibits disulfide-HMGB1-induced activation of TLR4/MD-2 signaling by binding with high affinity to TLR4, thereby displacing native HMGB1 (34). In vitro, bacterially derived rBox A inhibited cytokine release from HMGB1-treated murine Mϕ (30). rBox A also reduced inflammation associated with allograft rejection (51), ischemia (52, 53), sterile injury (34), and others. However, in a model of intratracheal (i.t.) LPS, even 600 µg/mouse of rBox A was only partially protective (54), and this same dose administered multiple times to mice that received LPS systemically or during cecal ligation and puncture, induced only partial protection (30). Our data showing a lag of 2–4 days for induction of circulating HMGB1 in response to influenza (41), coupled with the partial efficacy of Eritoran as late as 6 days p.i. (14), suggests there is a therapeutic window in influenza-induced ALI.

Herein, we report the development of a novel, inflammation-inducible rBox A expression cassette encoded by a non-replicative AdV vector, “AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A,” that mitigates lung and systemic inflammation when administered therapeutically to influenza-infected animals. We anticipate that this approach may be tested using diverse viral vectors, and will apply to the treatment of multiple diseases in which HMGB1-mediated TLR4/MD-2 signaling is a central driver of inflammation (45).

RESULTS

Engineering AdV.C3-Tat.HIV-Box A vectors

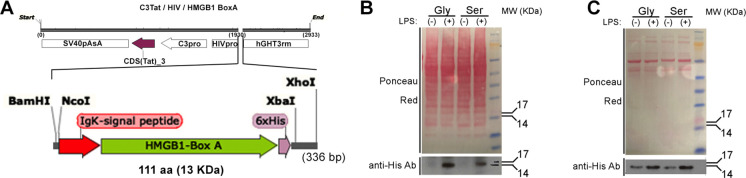

Figure 1A illustrates that the AdV vector expresses the protein of interest (rBox A) under the control of a two-component expression system developed by Varley and colleagues (55–57). The construct contains an inflammation-activated promoter region (mouse C3 gene promoter) that, in response to inflammatory insults, drives the production of HIV transactivator of transcription (Tat), that induces transcription of the gene of interest through its HIV LTR promoter, inserted into a non-replicating AdV vector. This inflammation-inducible cassette was first used successfully to express luciferase (Luc) in vivo (55–57) in response to i.p. LPS or turpentine, and later, to mitigate joint inflammation in rodent models of arthritis by intraarticular expression of IL-1R antagonist (58) or IL-10 (59). We hypothesized that in mice and CR challenged with LPS or infected with influenza, treatment with our engineered vectors, “AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer” or “AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly,” would produce rBox A to mitigate ALI by antagonizing TLR4-mediated inflammation induced by HMGB1, while “AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc” would secrete luciferase and serve as a negative control.

Fig 1.

(A) Structure of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A cloned under control of a two-component, inflammation-driven, AdV expression system (C3-Tat/HIV, top), our chimeric DNA construct encodes the HMGB1 Box A protein (green arrow) flanked by a secretory peptide (N-terminus, red arrow) and a C-terminal, 6x-His tag (purple arrow) (total 111 aa). (B) Detection of HMGB1 Box A produced in cell lysates of CR peritoneal Mϕ infected in vitro with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly or -Box ASer (MOI = 1) and then treated with LPS (10 ng/mL, 18 h). (C) Detection of secreted HMGB1 Box AGly or HMGB1 Box ASer by CR BAL Mϕ obtained 24 h after i.n. infection with 107 PFU of the indicated AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vector. BAL Mϕ were harvested 24 h after infection with AdV vectors, then cultured and treated with LPS for 24 h, followed by the analysis of culture supernatants by WB.

Several modifications to the Box A sequence were made before insertion into the original AdV construct based on predictions that would facilitate secretion, purification, and detection: (i) The N-terminus of the Box A sequence was placed in tandem with the IgK signal peptide sequence to enhance secretion because, due to the lack of a leader sequence, Box A cannot be actively secreted through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi secretory pathway (60, 61); (ii) The predicted glycosylation site within the wild-type (WT) sequence, “NFS” (resulting in rBoxASer), was mutated to “NFG” (resulting in non-glycosylatable rBox AGly), to prevent retention of rBox A protein in the ER; and, (iii) A 6X-His tag sequence was added to the Box A C-terminus to facilitate detection by western blot (WB) and permit rBox A purification by Ni++ columns.

Comparable protein expression of rBox ASer and rBox AGly constructs was observed in transient transfection experiments using Expi293F cells (data not shown). Optimized Box A expression constructs were transferred from a pENTR 1A dual selection vector to the final AdV vector by in vitro homologous recombination with a plasmid containing an E1/E3 deleted (non-replicating) AdV backbone using Gateway cloning. Genome sequences were confirmed, and viruses were rescued following Pacl genome linearization and transfection into TRex293 cells. AdV recombinants encoding Box ASer, Box AGly, and luciferase (Luc) were amplified, purified by two rounds of CsCl ultracentrifugation, titrated for infectious titers (all virus stocks had a viral titer of >1011 PFU/mL) and physical titers (>1012 vp/mL)) (62, 63).

Inducibility of the non-replicating AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A promoter system by inflammatory stimuli

CR peritoneal Mϕ were infected with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. After 24 h, Mϕ were treated with medium or LPS (10 ng/mL) for 18 h. Proteins were separated on a 4%–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a membrane that was stained with Ponceau red for total protein (Fig. 1B, top) and WB with anti-His antibody (Fig. 1B, bottom). AdV-infected CR Mϕ expressed both WT (Ser) and mutated (Gly) Box A proteins only when stimulated with LPS (with the Box AGly showing slightly higher expression) at the predicted 13 kDa MW by WB. CR bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) Mϕ obtained 24 h after i.n. inoculation with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (107 PFU/CR), were stimulated ex vivo with LPS (Fig. 1C). While low levels of Box A-His proteins were detected in culture supernatants of BAL Mϕ stimulated with medium only, levels of both Box A variants increased comparably upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 1C), indicating that glycosylation of rBox A does not impede secretion. Low levels of rBox A in supernatants of the medium-treated Mϕ are likely attributable to low-level inflammation in vivo that stimulates the vectors’ C3 promoter to induce the His-tagged protein.

To confirm the inflammation-inducible activity of the promoter in vitro, CR Mϕ were infected with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (MOI = 1) 24 h prior to LPS stimulation for an additional 24 h, resulting in strong luciferase induction (Fig. 2A). In vivo, mice were administered AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc i.n. (105 PFU/mouse) 3 days prior to the LPS challenge (10 µg/mouse i.t.). After 18 h, a time when LPS induces significant lung pathology and cellular infiltration (39), luciferase levels in lung homogenates were significantly increased only in response to LPS (Fig. 2B), indicating inflammation-induced activation of the construct in vivo. Next, CR were treated i.n. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (105 PFU/CR) and infected 3 days later with human influenza A(H3N2) (A/Wuhan/359/95; 107 TCID50/CR). Lung luciferase activity was significantly increased 1 and 2 days p.i. (Fig. 2C). These data correlated with endogenous C3 gene expression in CR Mϕ treated with LPS (Fig. 2D) and the early kinetics of expression of Box AGly and Box ASer mRNA in in CR Mϕ transduced with AdV-C3.Tat/HIV-Box AGly or AdV-C3.Tat/HIV-Box ASer followed by LPS treatment (Fig. 2E). Importantly, (i) mice/CR treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc alone (without inflammatory induction) showed low luciferase expression (Fig. 2B and C) and (ii) treatment of CR i.n. with either PBS (Fig. 3A) or with 107 PFU of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc for 1 day (Fig. 3B) or 3 days (Fig. 3C) failed to induce lung inflammation, in contrast to the strong alveolitis and interstitial pneumonia seen 3 days p.i. with A(H3N2) (Fig. 3D). Thus, our AdV.C3-Tat/HIV vectors are inducible by ALI-inducing challenges and safe in vivo in the absence of an inflammatory stimulus.

Fig 2.

(A) CR peritoneal Mϕ were treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc for 24 h and half the samples were exposed to LPS (10 ng/mL) for an additional 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates (n = 4, Student’s t test, ****P < 0.0001). (B) Mice were treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc i.n. and challenged with saline or LPS i.t. (10 µg/mouse); mice were sacrificed at 18 h post-challenge, and lung luciferase levels were measured; P < 0.05, Student’s t test. (C) CR were treated i.n. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (105 PFU/CR) and challenged i.n. with PBS or influenza A(H3N2) virus (107 TCID50/animal). CR were sacrificed at the indicated times p.i. with A(H3N2) (105 TCID50/CR) and luciferase expression measured in lung homogenates. (n = 3–5/group; ANOVA, ***P < 0.0001; **P < 0.01). (D) CR peritoneal Mϕ were exposed to LPS (10 ng/mL) for the indicated times. Expression of the endogenous cotton rat C3 gene was determined by quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR. (E) CR peritoneal Mϕ were transduced with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer using an MOI = 1. Twenty-four hours post-transduction, cells were exposed to medium only (black symbols), LPS (Gly—red symbols; Ser—blue symbols) for the indicated time periods. Expression of the vector-based Box A mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR to show the kinetics of Adv.C3-Tat/HIV/Box A expression of the C3 mRNA post-LPS treatment.

Fig 3.

CR were treated i.n. with PBS (A; 100 µL), or with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (B and C; 107 PFU/CR in 100 µL) and sacrificed on days 1 (A, B) or day 3 p.i. (C), showing undetectable lung inflammation in CR treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc in contrast to CR infected with A(H3N2) (107 TCID50/CR) and harvested on day 3 p.i. (D). Magnification, 100×. Insets show details of bronchi, 200×.

AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A therapy protects mice against lethal influenza

Mice were infected with PR8 (LD90), then 24 h later, administered saline, 2 × 107 PFU of AdV-C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (i.v.) or 2 × 107 PFU of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly (an equal mix of Ser and Gly variants) by either i.v. or i.m. routes. We initially used a mixture of the AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly since we did not know if the two vectors would be equivalently protective, despite comparable expression. This dose is very low compared to doses used for vaccines or gene therapy (e.g., 109 to 1010 PFU (64)). Neither saline- nor AdV-C3-Tat/HIV-Luc protected mice against the lethal PR8 challenge (Fig. 4A). By contrast, a single i.v. dose of the AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly vectors significantly improved survival (to ~60%), while i.m. treatment AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A only delayed death (blue line, Fig. 4A). When the i.m. dose of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vectors was increased 10-fold to 2 × 108 PFU/mouse, survival was enhanced to ~50%, approaching that induced by i.v. administration of 2 × 107 PFU/mouse (compare Fig. S2 (2 × 108 i.m.) with Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

(A) C57BL/6J mice were infected on day 0 with PR8 (LD90). Twenty-four hours later, mice were treated with saline (i.m.), AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (i.v.), or an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (2 × 107 PFU/mouse) administered either i.m or i.v. Data are from two separate experiments with 5 mice/treatment/experiment. Results from AdV-Luc-treated mice were obtained from 5 mice in a single experiment. (B) Mice were infected as in panel A. Twenty-four hours later, mice were treated i.v. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (2 × 107 PFU/mouse), an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants, or the individual AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (Gly or Ser) (2 × 107 PFU/mouse). Data are from two separate experiments with 5 mice/treatment/experiment. (C). Mice were infected as in panel A. Mice were treated i.v. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (2 × 108 PFU/mouse), an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants, or the individual AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (Gly or Ser) (2 × 108 PFU/mouse). Data are from two separate experiments with 5 mice/treatment/experiment. (D) Mice were infected as in panel A. Mice were treated i.v. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (2 × 107 PFU/mouse) or an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (2 × 107 PFU/mouse) on day 1, day 3, or day 5 post-infection. N = 5 mice/treatment group. (E) Mice were infected as in panel A. Mice were treated i.v. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (2 × 108 PFU/mouse) or an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (2 × 108 PFU/mouse) at day 1, day 3, or day 5 p.i. N = 5 mice/treatment group.

These experiments were extended by comparing the responses of mice to influenza PR8 infection, followed on day 1 by i.v. treatment with 2 × 107 PFU/mouse of the AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc, AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly, AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer only, or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly only. No mice survived treatment with control AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc. Surprisingly, the mixture of the two variant vectors was more protective than the same dose of either variant vector alone (Fig. 4B). When the dose of the mixed and individual vectors was increased 10-fold and administered on day 1, the individual Box A Ser or Gly vectors protected mice comparably to the mixture (Fig. 4C). To assess whether treatment could be delayed and still protect, mice were infected then administered 2 × 107 PFU/mouse of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (day 1 only) or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly i.v. on days 1, 3, or 5 p.i. Figure 4D shows that AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly treatment at day 1 p.i. elicited the same degree of protection seen in Fig. 4A and B. Delaying treatment until day 3 p.i. resulted in a significant increase in the time to death (P = 0.0179). No protection was observed if treatment was delayed until day 5 p.i. When the treatment dose was increased 10-fold, enhanced protection was observed when the vector mixture was administered on day 3, but not if treatment was delayed until day 5 (Fig. 4E). Thus, protection induced by AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly are dose- and time-dependent.

CR were similarly treated i.v. with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer and whole blood and organs were collected 1 day later for analysis of AdV DNA by qPCR. AdV DNA was detected primarily in blood, liver, spleen, and heart, with small intestine and lung as secondary sites (Table S1). Thus, the AdV vector disseminates throughout the body upon i.v. delivery. Together, the data show that our non-replicating AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vectors are inflammation-regulated and sufficiently active in vitro and in vivo to induce rBox A in response to potent non-infectious or infectious inflammatory stimuli (e.g., LPS or influenza) and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A constructs protect against influenza-induced disease.

Effect of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A therapy on the inflammatory response to influenza

Mice were infected and treated i.v. as in Fig. 4A. Five days p.i., a time just before control mice begin to die, lungs were harvested and pathology was blindly scored in H&E-stained sections as detailed in Materials and Methods (65). Figure 5A shows representative photomicrographs of lung sections. Mice treated therapeutically with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (left) exhibited much greater lung inflammation than mice treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly (right). Mice treated with 2 × 107 PFU/mouse of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly exhibited significantly reduced pathology for each parameter as well as for the combined pathology score (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

C57BL/6J mice were infected on day 0 with PR8 (LD90). Twenty-four hours later, mice were treated i.v. with saline (mock), AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc, or an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (2 × 107 PFU). (A) Representative pathology of lung sections derived from mice treated therapeutically with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A 24 h after infection with PR8 (LD90) at 5 days p.i. (B) Quantification of lung histopathology scores for the individual mice including a combined histology score. (C) Quantification of lung cytokine mRNA levels by qRT-PCR for the individual mice. (B and C) Each symbol represents one mouse.

The effect of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A therapy on the cytokine response induced by influenza was also measured. Mice that received saline only (mock) had low levels of lung cytokine mRNA, in contrast to PR8-infected mice treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (Fig. 5C). PR8-infected mice treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer/Gly had significantly decreased lung inflammatory cytokine mRNA observed compared to AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc treatment. At this same time, levels of AdV vectors were comparable (Fig. S3).

CR were infected i.n. with influenza A(H3N2) (107 TCID50/CR) on day 0. On day 1 p.i., groups of CR were treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc, AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly, or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (107 PFU/animal, i.v.), and sacrificed on either day 3 or day 6 p.i. (Fig. 6). Figure 6A shows that just 2 days post-treatment, levels of TNFα mRNA were significantly reduced in CR that received AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly vector, with a similar but non-significant trend for those treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer. Conversely, levels of anti-inflammatory IL-10 mRNA were upregulated by treatment with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer. No significant change in the production of influenza M protein mRNA was detected (data not shown), indicating that influenza replication was not affected at this time point. Lung histopathology (Fig. 6B) at day 3 p.i. revealed significantly reduced alveolitis in CR treated with either AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (Fig. 6B and C).

Fig 6.

CR were infected i.n. on day 0 with A(H3N2) (107 TCID50/CR). On day 1 p.i., CR were treated by i.v. injection with 107 PFU/CR of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc, AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer. CR were then sacrificed on 3 and 6 days p.i. to analyze lung cytokine mRNA expression and lung histopathology. (A) mRNA expression of TNFα and IL-10 in lung samples of CR sacrificed on day 3 p.i. (n = 4/treatment). (B) Score of alveolitis at 3 days p.i. for the different groups of CR (n = 4/treatment). (C) Representative microscopic images of lungs of CR treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (a), AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly (b), or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (c) showing reduced numbers of cells in the alveolar spaces of CR treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vectors. Magnification, 200×. (D) mRNA expression of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-10 in lungs of CR harvested at day 6 p.i. (n = 5/treatment) (E) Pathology scores for lungs of individual CR for peribronchioliis, perivasculitis, interstitial pneumonia, and alveolitis (n = 5/treatment). (F) Representative microscopic images of lungs of CR treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (a), AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly (b), or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (c) showing reduced peribronchiolitis in animals treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vectors. Magnification, 40×. n = 4–5/group; Student t test, **P < 0.01; **P < 0.05.

In CR lungs harvested at day 6 p.i., levels of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-10 mRNA were significantly reduced only when treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (Fig. 6D). Peribronchiolitis and alveolitis scores were significantly decreased in CR treated with either Box A variant, whereas interstitial pneumonia was significantly reduced only in CR that had been treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly. By day 6, perivasculitis was not resolved in any group (Fig. 6E). Figure 6F illustrates representative images from CR treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (i), AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly (ii), or AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer (iii) showing reduced peribronchiolitis in CR treated with both Box A variants. Thus, both AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer exert anti-inflammatory effects in response to human influenza A(H3N2) infection of CR.

DISCUSSION

Increased circulating HMGB1 correlates with many inflammatory diseases, that is, sepsis, viral respiratory infections, traumatic brain injury, systemic lupus erythematosus, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and others (42–46). HMGB1 has three cysteine residues, but only the disulfide (cys23 and cys45) isoform is a TLR4 DAMP, binding MD-2 at a site distinct from LPS. Blocking the HMGB1 binding to MD-2 with P5779 blocked HMGB1-mediated, but not LPS-induced TLR4 signaling (32). In addition, monoclonal antibody 2G7 (directed against Box A), rBox A, and glycyrrhizin (a molecule that binds HMGB1) antagonize HMGB1-mediated signaling in models of inflammation (66–69), yet have not advanced beyond pre-clinical studies. We hypothesized that an inflammation-inducible viral vector might facilitate more sustained expression of therapeutic transgenes that dissipate as inflammation wanes (70).

He et al. (34) showed that rBox A competitively antagonizes the binding of intact HMGB1 to TLR4, causing its release from both TLR4 and MD-2, thereby significantly reducing TLR4-mediated signaling. Our data support this model (Fig. 7) and indicate that sufficient HMGB1 Box A is synthesized from our AdV vectors in an inflammation-inducible fashion to blunt the effect of HMGB1 in rodent models of LPS and influenza challenge.

Fig 7.

Model. Intact HMGB1 contains two domains, HMGB1 Box A and HMGB1 Box B. The HMGB1 Box A domain binds to TLR4, while the HMGB1 Box B domain binds MD-2 to elicit TLR4 signaling (top image). In response to an inflammatory stimulus, the Adv.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vector produces rBox A that competitively inhibits the binding of the intact protein HMGB1’s Box A domain to TLR4 and precludes its Box B from binding to MD-2 (bottom image).This results in disruption of TLR4-mediated signaling (modified from reference 34).

In experimental endotoxicity and sepsis, where bacterial-derived rBox A or P57799 was used to antagonize HMGB1-mediated signaling, high concentrations, and multiple doses were required (17, 30). We sought proof of principle that therapy with an AdV vector that elicits inflammation-inducible rBox A would mitigate ALI in two well-established rodent models of influenza. We took advantage of a non-replicating AdV vector to respond to inflammation to drive the production of specific proteins (55–59). Specifically, luciferase was expressed in AdV-treated mice challenged with LPS or turpentine (55, 56), and when modified to express IL-10 or IL-1RA, and administered into the joints of arthritic rodents, lessened inflammation (58, 59). When we substituted the HMGB1 Box A sequence for sequences encoding luciferase, IL-10, or IL-1RA, Box A-His protein was secreted in response to inflammatory stimuli in vitro, ex vivo, or in vivo. AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer failed to induce significant inflammation in CR at high doses; however, when administered therapeutically after influenza infection, lethality, and ALI were mitigated in mice, as was ALI in CR, accompanied by a significant reduction in proinflammatory cytokine responses. Intravenous was more effective than i.m. treatment, but increasing the dose i.m. compensated to improve survival and may be related to different kinetics of rBox A expression or cellular tropism of the AdV vector. Unexpectedly, an equal mixture of the AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly variants, presumably producing both glycosylated and non-glycosylated forms of rBox A, provided greater protection at a lower dose (2 × 107 PFU/mouse) than an equivalent dose of either variant alone. Nonetheless, increasing the dose of either variant alone 10-fold improved survival equivalent to that of the mixed vectors. While we do not know the mechanism underlying this observation, it is possible that differentially glycosylated rBox A proteins are released in different compartments in vivo, antagonize topologically different TLR4/MD-2 receptors, or that the two different rBox A variants interact synergistically to compete with HMGB1 for binding to TLR4. Since rBox A blocks RAGE-dependent endocytosis (71), our approach may also apply to RAGE-mediated diseases, in contrast to P5779 which is specific for TLR4/MD-2 (32). Together, treatment of influenza-infected mice/CR with the inflammation-inducible AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A decreased lethality, pathology, and proinflammatory cytokine expression.

The protection from lethal PR8 challenge by TLR4 or HMGB1 antagonists exceeded that reported herein with the AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A vector (95%–100% vs. ~60%). This may be attributable to the fact that the former was administered at high doses daily for each of 5 days, in contrast to a single injection of AdV.C3-TAT/HIV-Box A. This was done intentionally to minimize the host response to the vector itself. Studies are ongoing to further optimize vector delivery, timing, and route of administration.

This approach is early in development but has significant potential for treating multiple HMGB1-mediated diseases. To demonstrate proof-of-concept, we used a human adenovirus type-5 vector (HAdV-C5) due to the ease of genetic engineering, the ability to grow it to high titers, and well-established dosing regimens for rodents. However, humans may have pre-existing immunity to this AdV serotype, which could negate the therapeutic effect (72). In addition, i.v administration of AdV5 in humans warrants caution due to off-target interactions with coagulation factors and other blood components, possibly resulting in dose-limiting toxicity (73). Despite this, this inducible therapeutic transgene cassette is compatible with many other vector systems such as rare serotype AdVs (>200 vectors exist with low seroprevalence in humans (72, 74)), adeno-associated vectors, or lentiviruses (75). Such platforms could be engineered and tailored to specific inflammatory disease conditions in the future, including those focused on localized delivery rather than systemic delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc

Adenovirus C3-tat/HIV-luc (provided by Dr. Robert Munford (56)) was transduced into HEK-293A cells that were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% amphotericin B, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% glutamax (ThermoFisher, 35050061). Transductions were done using 50 µL of virus stock in opti-MEM (ThermoFisher, 31985-070) for 1 h in a 75% confluent T225 culture flask at 37°C. After 2 days, viruses were harvested by collecting the medium and lysing cells using three freeze-thaw cycles in PBS. Lysates were centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 15′ at 4°C). Cleared lysates’ supernatant and medium were pooled, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C as AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc viral stocks.

Amplification of the AdV transgene

DNA was extracted from virus stocks using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, 51304). DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification of the two-component transgene (C3-Tat/HIV(LTR)-Luc), with the following primers that incorporate KpnI and XhoI sites: FWD, 5′-CAGCTTTAAAGGTACCCGGGGATCCAGACATGATAAGATAC-3′; REV, 5′-TAGCTGATATCCTCGAGATCGATGATACCCAATTCAACAGGC-3′.

Reactions were carried out using GoTaq long PCR (Promega, M4021). Amplified fragments (cassette) were agarose gel purified and extracted (New England Biolabs, Monarch 1020S).

Cloning of C3-Tat/HIV(LTR)-Luc cassette into Gateway pENTR 1A dual selection vector (Invitrogen, A10462)

Box A expression cassettes were cloned into pENTR 1A dual selection vector (ThermoFisher, A10462). Plasmids were purified from the T1 bacteria (Invitrogen, A10460) using a plasmid maxi-prep kit (Qiagen, 12362). Amplified PCR products were cloned into pENTR 1A using KpnI and XhoI restriction sites.

Primers for sequencing (5′→3′) were as follows: CACCACTGCTCCCATTCATCAGTTCC, GATCGCCGTGTAATTCTAGAGGATC, CCTTACTTCTGTGGTGTGACATAATTGG, CCTTTCTTTATGTTTTTGGCGTCTTCC, and GTAACATCAGAGATTTTGAGACA.

Transfer of the HMGB1-Box A (Ser or Gly) transgene into the cassette

pcDNA3.1 plasmids containing the engineered “IgK leader-Box A-6×His” constructs were synthesized using synthesis services (GeneWhiz) and amplified using primers that included a NcoI or NotI site matching cloning sites in the pENTR 1A.C3-Tat/HIV(LTR)-Luc. Sequencing confirmed the cloning of Box A inserts (accession number X12597.1, HMGB1 sequence human mRNA and nucleotides 53–319 for Box A), resulting in three pENTR 1A with the two-component inducible-expression system: C3-Tat/HIV-Luc, C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer, and C3-Tat/HIV-Box AGly.

Propagation of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A and AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc constructs

Recombinant AdV5 genomes (E1/E3 deleted) were produced by in vitro homologous recombination using LR clonase and gateway technology (Life Technologies). Plasmids containing genetically modified adenoviral genomes were fully sequence confirmed using PlasmidSaurus Inc., followed by PacI digestion to release the viral genome, and transfection into T-Rex-293 cells (Life Technologies). Viruses were scaled up, released from cells by freeze-thaw cycles, purified using two rounds of CsCl ultracentrifugation, and titrated (76). Physical viral particle titers were determined using a microBCA assay (63, 77). Expression of rBox ASer and rBox AGly was confirmed in transient transfection experiments using Expi293F cells (ThermoFisher).

Mice and CR

Six-week-old WT C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Six- to 8-week-old RAGE−/− mice (provided by Dr. Ann Marie Schmidt, NYU) were bred in-house at UMB. Four- to 6-week-old female and male CR (~100 g), seronegative for adventitious respiratory viruses, were obtained from SBI’s inbred colony.

For in vitro studies, thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal CR Mϕ was cultured as reported (78). BAL Mϕ were collected by washing the entire lung block with 3 mL cold saline, three times (78).

Influenza viruses

Mouse-adapted A(H1N1) influenza A/PR/8/34 virus (“PR8”) (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was kindly provided by Dr. Donna Farber (Columbia University). The human A(H3N2) virus was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and propagated in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells.

Mouse and CR virus challenge and treatment

For survival experiments, mice were infected with an LD90 of PR8 (~7500 TCID50 i.n., 25 µL/nares) (14, 17). One day after infection, mice received saline, AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc (2 × 107 PFU), an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants, i.m or i.v., or the individual AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (Gly or Ser) (2 × 107 PFU or 2 × 108 PFU) by i.v. injection. For time course studies, mice were infected on day 0 with PR8 (LD90), then treated with AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc or an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (2 × 107 PFU or 2 × 108 PFU) i.v. on days 1, 3, or 5 p.i. For tissue analysis, mice were infected on Day 0 with PR8 (LD90). Day 1 p.i., mice were treated with saline (mock), AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Luc, or an equal mixture of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A variants (2 × 107 PFU) i.v. On Day 5 p.i., lungs were harvested for histology and gene expression. WT and RAGE−/− mice were infected with PR8 (LD90). Mice were monitored daily for 14 days.

CR were infected i.n. with 100 µL (107 TCID50) of A(H3N2) virus. Treatments were performed retro-orbitally under isoflurane anesthesia. In some experiments, AdV vectors were administered i.n. Animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation.

Western blot

For secreted protein, culture supernatants were collected with protease inhibitor (CST, 5871S), and incubated with Ni-Sepharose FF-6 beads (Cytiva, 17531806, 50% slurry) for 2 h at RT. Washed beads were incubated with sample buffer and 10× reducing agent (Invitrogen, NP0007, NP0009), boiled, and loaded onto a 4%–12% Bis-Tris gel (NuPAGE, Invitrogen). Cell lysates were collected in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatants were mixed with 10× reducing agents and loaded onto gels (NuPAGE, Invitrogen). Ponceau stain (Sigma-Aldrich, P7170) reflected protein loading. MW markers (Cytiva, RPN800E) and rBox A produced in Expi293F cells (ThermoFisher, A14635) transfected with a pcDNA3.1 containing the Box A sequence were used to confirm MW and antibody specificity. Primary anti-6x His (ThermoFisher, MA1-21315) or anti-HMGB1 (Abnova, H00003146-M08) antibodies (1:1,000 dilution) and a sheep anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate (Cytiva NA931V) were used for detection. Blots were developed using ECL substrate and film (Cytiva, RPN3004, 28906838).

Luciferase assays

Mϕ were lysed in Glo-lysis buffer (Promega, E266A), mixed with equal volumes of Bright-Glo reagent (Promega, E2610), and assayed on a luminometer (Promega, GM2000 Glomax Navigator).

For tissue luciferase assays, ~200 mg tissue was placed into 1.5 mL of Glo-lysis buffer with two steel beads, homogenized at 50 Hz on a Qiagen tissuelyser LT, centrifuged, and 100 µL of supernatant mixed with 100 µL of Bright-Glo reagent to assay.

Tissue distribution of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box A following i.v. injection of CR

CR were treated retro-orbitally with 1 × 107 PFU of AdV.C3-Tat/HIV-Box ASer. One day post-treatment, CR were bled, euthanized, and organs dissected for the detection of the AdV genome using qPCR with two different specific primer sets, the +AdV set (79) and the +Hex set (80). Tissues of uninfected animals showed Ct values of 40.

Histology and staining

Lungs were inflated and fixed with 4% PFA. Lung sections (5 µm) were stained with H&E. Four parameters were scored independently from 0 to 4 for each section: peribronchiolitis (primarily lymphocytes, surrounding a bronchiole), perivasculitis (primarily lymphocytes, surrounding a blood vessel), alveolitis (within alveolar spaces), and interstitial pneumonia (increased thickness of alveolar walls). Slides were randomized and blindly scored. Data are shown as individual scores for each parameter or a cumulation of the four parameters (65).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total murine RNA isolation and quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR were performed as previously described (14, 81, 82). Levels of mRNA for specific mouse genes were normalized to the level of the housekeeping gene, Hprt, in the same samples (83). For CR qRT-PCR (41, 84), amplifications were performed on a Bio-Rad iCycler (MyiQ Single Color). Each gene was normalized to β-actin mRNA as a housekeeping gene (83). Data are expressed as “fold induction” (2−ΔΔCt) over mock-treated animals.

Statistics

Statistical differences between the two groups were determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test with significance set at P < 0.05. For >3 groups, analysis was done by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test with significance determined at P < 0.05. For survival studies, a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Dominic Esposito, director, Protein Expression Laboratory (NCI, NIH), with whom we discussed modifications to the HMGB1 Box A sequence that would be predicted to facilitate secretion, purification, and detection once inserted into the AdV vector and produced in host cells. We also are very grateful to Dr. Robert S. Munford (NIAID, NIH) for his careful reading of the manuscript and his insightful suggestions.

Provisional Patent Application Number 63/680,304 was filed 7 August 2024, titled “Inducible HMGB1 antagonist for mitigating local and systemic inflammation,” and Provisional Patent Application Number 63/721,755 was filed 18 November 2024, titled "An Adenoviral Vector Encoding an Inflammation-inducible Antagonist, HMGB1 Box A, as a Therapeutic for Inflammatory Diseases."

Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health grants R41 HL167254 (J.C.G.B. and S.N.V.) and R01 AI148369 (L.C.)

Conceptualization: J.C.G.B. and S.N.V. Vector engineering: J.J., J.B., A.W.V., L.C., and H.N. Adenovirus propagation L.C. and H.N. Investigation: K.A.S., S.V., J.J., and J.C.G.B. Funding acquisition: J.C.G.B., S.N.V., and L.C. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article is a direct contribution from Stefanie N. Vogel, a Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology, who arranged for and secured reviews by Jonathan Kagan, Boston Childrens Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and Mira Patel, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Stefanie N. Vogel, Email: svogel@som.umaryland.edu.

Sara Cherry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All primary data from which the figures in this paper and the supplemental materials are deposited in the OSF public database at https://osf.io/dgyxw/. All novel materials described will be provided through a licensing agreement or a materials transfer agreement with the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

ETHICS APPROVAL

All animal work was conducted under approved IACUC protocols from the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB), and Sigmovir Biosystems Inc. (SBI), both AAALAC-accredited institutions.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.03387-24.

Table S1 and Fig. S1 to S3.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. 2008. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis 198:962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chertow DS, Memoli MJ. 2013. Bacterial coinfection in influenza: a grand rounds review. JAMA 309:275–282. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.194139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rynda-Apple A, Robinson KM, Alcorn JF. 2015. Influenza and bacterial superinfection: illuminating the immunologic mechanisms of disease. Infect Immun 83:3764–3770. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00298-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, Roberts PC, Augustine AD, Ferguson S, Paules CI, Graham BS, Fauci AS. 2018. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis 218:347–354. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rajão DS, Pérez DR. 2018. Universal vaccines and vaccine platforms to protect against influenza viruses in humans and agriculture. Front Microbiol 9:123. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nachbagauer R, Feser J, Naficy A, Bernstein DI, Guptill J, Walter EB, Berlanda-Scorza F, Stadlbauer D, Wilson PC, Aydillo T, et al. 2021. A chimeric hemagglutinin-based universal influenza virus vaccine approach induces broad and long-lasting immunity in A randomized, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Nat Med 27:106–114. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1118-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coughlan L, Palese P. 2018. Overcoming barriers in the path to a universal influenza virus vaccine. Cell Host Microbe 24:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/media/pdfs/2024/09/treating-influenza.pdf. Retrieved 16 Oct 2024.

- 9. Govorkova EA, Takashita E, Daniels RS, Fujisaki S, Presser LD, Patel MC, Huang W, Lackenby A, Nguyen HT, Pereyaslov D, Rattigan A, Brown SK, Samaan M, Subbarao K, Wong S, Wang D, Webby RJ, Yen HL, Zhang W, Meijer A, Gubareva LV. 2022. Global update on the susceptibilities of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir, 2018-2020. Antiviral Res 200:105281. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nye S, Whitley RJ, Kong M. 2016. Viral infection in the development and progression of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front Pediatr 4:128. doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalil AC, Thomas PG. 2019. Influenza virus-related critical illness: pathophysiology and epidemiology. Crit Care 23:258. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2539-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li H, Liu L, Zhang D, Xu J, Dai H, Tang N, Su X, Cao B. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet 395:1517–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nhu QM, Shirey K, Teijaro JR, Farber DL, Netzel-Arnett S, Antalis TM, Fasano A, Vogel SN. 2010. Novel signaling interactions between proteinase-activated receptor 2 and Toll-like receptors in vitro and in vivo. Mucosal Immunol 3:29–39. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shirey KA, Lai W, Scott AJ, Lipsky M, Mistry P, Pletneva LM, Karp CL, McAlees J, Gioannini TL, Weiss J, Chen WH, Ernst RK, Rossignol DP, Gusovsky F, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. 2013. The TLR4 antagonist Eritoran protects mice from lethal influenza infection. Nature New Biol 497:498–502. doi: 10.1038/nature12118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Opal SM, Laterre P-F, Francois B, LaRosa SP, Angus DC, Mira J-P, Wittebole X, Dugernier T, Perrotin D, Tidswell M, et al. 2013. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA 309:1154–1162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Piao W, Shirey KA, Ru LW, Lai W, Szmacinski H, Snyder GA, Sundberg EJ, Lakowicz JR, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. 2015. A decoy peptide that disrupts TIRAP recruitment to TLRs Is protective in a murine model of influenza. Cell Rep 11:1941–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shirey KA, Lai W, Patel MC, Pletneva LM, Pang C, Kurt-Jones E, Lipsky M, Roger T, Calandra T, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y, Bowie AG, Fasano A, Dinarello CA, Gusovsky F, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. 2016. Novel strategies for targeting innate immune responses to influenza. Mucosal Immunol 9:1173–1182. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perrin-Cocon L, Aublin-Gex A, Sestito SE, Shirey KA, Patel MC, André P, Blanco JC, Vogel SN, Peri F, Lotteau V. 2017. TLR4 antagonist FP7 inhibits LPS-induced cytokine production and glycolytic reprogramming in dendritic cells, and protects mice from lethal influenza infection. Sci Rep 7:40791. doi: 10.1038/srep40791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shirey KA, Lai W, Brown LJ, Blanco JCG, Beadenkopf R, Wang Y, Vogel SN, Snyder GA. 2020. Select targeting of intracellular Toll-interleukin-1 receptor resistance domains for protection against influenza-induced disease. Innate Immun 26:26–34. doi: 10.1177/1753425919846281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blanco JCG, Pletneva LM, Wan H, Araya Y, Angel M, Oue RO, Sutton TC, Perez DR. 2013. Receptor characterization and susceptibility of cotton rats to avian and 2009 pandemic influenza virus strains. J Virol 87:2036–2045. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00638-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ottolini MG, Blanco JCG, Eichelberger MC, Porter DD, Pletneva L, Richardson JY, Prince GA. 2005. The cotton rat provides a useful small-animal model for the study of influenza virus pathogenesis. J Gen Virol 86:2823–2830. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81145-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blanco JC, Boukhvalova MS, Perez DR, Vogel SN, Kajon A. 2014. Modeling human respiratory viral infections in the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus). J Antivir Antiretrovir 6:40–42. doi: 10.4172/jaa.1000093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shirey KA, Perkins DJ, Lai W, Zhang W, Fernando LR, Gusovsky F, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. 2019. Influenza "trains" the host for enhanced susceptibility to secondary bacterial infection. MBio 10:e00810-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00810-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shirey KA, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. 2021. Targeting TLR4 signaling to blunt viral-mediated acute lung injury. Front Immunol 12:705080. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.705080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Orr JD. 2013. Highly purified antiendotoxin compound. Patent no: US 8,377,893 B2. Date of patent: Feb. 19, 2013, issued

- 26. Christ WJ, McGuinness PD, Asano O, Wang Y, Mullarkey MA, Perez M, Hawkins LD, Blythe TA, Dubuc GR, Robidoux AL. 1994. Total synthesis of the proposed structure of Rhodobacter sphaeroides lipid A resulting in the synthesis of new potent lipopolysaccharide antagonists. J Am Chem Soc 116:3637–3638. doi: 10.1021/ja00087a075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rossignol DP, Wong N, Noveck R, Lynn M. 2008. Continuous pharmacodynamic activity of eritoran tetrasodium, a TLR4 antagonist, during intermittent intravenous infusion into normal volunteers. Innate Immun 14:383–394. doi: 10.1177/1753425908099173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersson U, Yang H, Harris H. 2018. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) operates as an alarmin outside as well as inside cells. Semin Immunol 38:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. 1999. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, Czura CJ, Wang H, Roth J, Warren HS, Fink MP, Fenton MJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. 2004. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434651100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lamkanfi M, Sarkar A, Vande Walle L, Vitari AC, Amer AO, Wewers MD, Tracey KJ, Kanneganti T-D, Dixit VM. 2010. Inflammasome-dependent release of the alarmin HMGB1 in endotoxemia. J Immunol 185:4385–4392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang H, Wang H, Ju Z, Ragab AA, Lundbäck P, Long W, Valdes-Ferrer SI, He M, Pribis JP, Li J, Lu B, Gero D, Szabo C, Antoine DJ, Harris HE, Golenbock DT, Meng J, Roth J, Chavan SS, Andersson U, Billiar TR, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y. 2015. MD-2 is required for disulfide HMGB1-dependent TLR4 signaling. J Exp Med 212:5–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Zoelen MAD, Yang H, Florquin S, Meijers JCM, Akira S, Arnold B, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Tracey KJ, van der Poll T. 2009. Role of toll-like receptors 2 and 4, and the receptor for advanced glycation end products in high-mobility group box 1-induced inflammation in vivo. Shock 31:280–284. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318186262d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He M, Bianchi ME, Coleman TR, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y. 2018. Correction to: Exploring the biological functional mechanism of the HMGB1/TLR4/MD-2 complex by surface plasmon resonance. Mol Med 24:21. doi: 10.1186/s10020-018-0030-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun S, He M, Wang Y, Yang H, Al-Abed Y. 2018. Folic acid derived-P5779 mimetics regulate DAMP-mediated inflammation through disruption of HMGB1:TLR4:MD-2 axes. PLoS One 13:e0193028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sun S, He M, VanPatten S, Al-Abed Y. 2019. Mechanistic insights into high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1)-induced Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) dimer formation. J Biomol Struct Dyn 37:3721–3730. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1526712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Youn JH, Oh YJ, Kim ES, Choi JE, Shin JS. 2008. High mobility group box 1 protein binding to lipopolysaccharide facilitates transfer of lipopolysaccharide to CD14 and enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated TNF-alpha production in human monocytes. J Immunol 180:5067–5074. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deng M, Tang MY, Li W, Wang X, Zhang R, Zhang X, Zhao X, Liu J, Tang C, Liu Z, et al. 2018. The endotoxin delivery protein HMGB1 mediates Caspase-11-dependent lethality in sepsis. Immunity 49:740–753. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Richard K, Piepenbrink KH, Shirey KA, Gopalakrishnan A, Nallar S, Prantner DJ, Perkins DJ, Lai W, Vlk A, Toshchakov VY, Feng C, Fanaroff R, Medvedev AE, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. 2021. A mouse model of human TLR4 D299G/T399I SNPs reveals mechanisms of altered LPS and pathogen responses. J Exp Med 218:e20200675. doi: 10.1084/jem.20200675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Zoelen MAD, van der Sluijs KF, Achouiti A, Florquin S, Braun-Pater JM, Yang H, Nawroth PP, Tracey KJ, Bierhaus A, van der Poll T. 2009. Receptor for advanced glycation end products is detrimental during influenza A virus pneumonia. Virology (Auckl) 391:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel MC, Shirey KA, Boukhvalova MS, Vogel SN, Blanco JCG. 2018. Serum High-Mobility-Group Box 1 as a biomarker and a therapeutic target during respiratory virus infections. MBio 9:e00246-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00246-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Andersson U, Tracey KJ. 2011. HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection. Annu Rev Immunol 29:139–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kang R, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ, Billiar TR, Tang D. 2014. Cell death and DAMPs in acute pancreatitis. Mol Med 20:466–477. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paudel YN, Angelopoulou E, Piperi C, Othman I, Shaikh MohdF. 2020. HMGB1-mediated neuroinflammatory responses in brain injuries: potential mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. IJMS 21:4609. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andersson U, Ottestad W, Tracey KJ. 2020. Extracellular HMGB1: a therapeutic target in severe pulmonary inflammation including COVID-19? Mol Med 26:42. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00172-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang Z, Simovic MO, Edsall PR, Liu B, Cancio TS, Batchinsky AI, Cancio LC, Li Y. 2022. HMGB1 inhibition to ameliorate organ failure and increase survival in trauma. Biomolecules 12:101. doi: 10.3390/biom12010101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang X, Hu X, Ou J, Chen S, Nie L, Gao L, Zhu L. 2020. Glycyrrhizin ameliorates radiation enteritis in mice accompanied by regulation of the HMGB1/TLR4 pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020:8653783. doi: 10.1155/2020/8653783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brammer J, Choi M, Baliban SM, Kambouris AR, Fiskum G, Chao W, Lopez K, Miller C, Al-Abed Y, Vogel SN, Simon R, Cross AS. 2021. A non-lethal murine flame burn model leads to a transient reduction in host defenses and enhanced susceptibility to lethal Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Infect Immun 89:e0009121. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00091-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang H, Andersson U, Brines M. 2021. Neurons are a primary driver of inflammation via release of HMGB1. Cells 10:2791. doi: 10.3390/cells10102791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li J, Kokkola R, Tabibzadeh S, Yang R, Ochani M, Qiang X, Harris HE, Czura CJ, Wang H, Ulloa L, Wang H, Warren HS, Moldawer LL, Fink MP, Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Yang H. 2003. Structural basis for the proinflammatory cytokine activity of high mobility group box 1. Mol Med 9:37–45. doi: 10.1007/BF03402105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang Y, Yin H, Han J, Huang B, Xu J, Zheng F, Tan Z, Fang M, Rui L, Chen D, Wang S, Zheng X, Wang C-Y, Gong F. 2007. Extracellular hmgb1 functions as an innate immune-mediator implicated in murine cardiac allograft acute rejection. Am J Transplant 7:799–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, Funke B, Eichberger SN, Kaya Z, Buss S, Autschbach F, Pleger ST, Lukic IK, Bea F, Hardt SE, Humpert PM, Bianchi ME, Mairbäurl H, Nawroth PP, Remppis A, Katus HA, Bierhaus A. 2008. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation 117:3216–3226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Muhammad S, Barakat W, Stoyanov S, Murikinati S, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Bendszus M, Rossetti G, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Schwaninger M. 2008. The HMGB1 receptor RAGE mediates ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci 28:12023–12031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2435-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gong Q, Xu J-F, Yin H, Liu S-F, Duan L-H, Bian Z-L. 2009. Protective effect of antagonist of high-mobility group box 1 on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Scand J Immunol 69:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Varley AW, Coulthard MG, Meidell RS, Gerard RD, Munford RS. 1995. Inflammation-induced recombinant protein expression in vivo using promoters from acute-phase protein genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:5346–5350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Varley AW, Geiszler SM, Gaynor RB, Munford RS. 1997. A two-component expression system that responds to inflammatory stimuli in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 15:1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nbt1097-1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Munford RS, inventor . 1998. U.S. Patent 5,744,304. Inflammation-induced expression of a recombinant gene

- 58. Bakker AC, van de Loo FAJ, Joosten LAB, Arntz OJ, Varley AW, Munford RS, van den Berg WB. 2002. C3-Tat/HIV-regulated intraarticular human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene therapy results in efficient inhibition of collagen-induced arthritis superior to cytomegalovirus-regulated expression of the same transgene. Arthritis Rheum 46:1661–1670. doi: 10.1002/art.10481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Miagkov AV, Varley AW, Munford RS, Makarov SS. 2002. Endogenous regulation of a therapeutic transgene restores homeostasis in arthritic joints. J Clin Invest 109:1223–1229. doi: 10.1172/JCI14536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kwak MS, Kim HS, Lee B, Kim YH, Son M, Shin J-S. 2020. Immunological significance of HMGB1 post-translational modification and redox biology. Front Immunol 11:1189. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.001189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Palade G. 1975. Intracellular aspects of the process of protein synthesis. Science 189:867. doi: 10.1126/science.189.4206.867-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang Y, Chirmule N, Gao GP, Qian R, Croyle M, Joshi B, Tazelaar J, Wilson JM. 2001. Acute cytokine response to systemic adenoviral vectors in mice is mediated by dendritic cells and macrophages. Mol Ther 3:697–707. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Coughlan L, Bradshaw AC, Parker AL, Robinson H, White K, Custers J, Goudsmit J, Van Roijen N, Barouch DH, Nicklin SA, Baker AH. 2012. Ad5:Ad48 hexon hypervariable region substitutions lead to toxicity and increased inflammatory responses following intravenous delivery. Mol Ther 20:2268–2281. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Curiel D. 2016. Adenoviral vectors for gene therapy. 2 [second edition]. Elsevier/Academic Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Prince GA, Prieels JP, Slaoui M, Porter DD. 1999. Pulmonary lesions in primary respiratory syncytial virus infection, reinfection, and vaccine-enhanced disease in the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus). Lab Invest 79:1385–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yang H, Wang H, Andersson U. 2020. Targeting inflammation driven by HMGB1. Front Immunol 11:484. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xue J, Suarez JS, Minaai M, Li S, Gaudino G, Pass HI, Carbone M, Yang H. 2021. HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in disease. J Cell Physiol 236:3406–3419. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Singh H, Agrawal DK. 2022. Therapeutic potential of targeting the HMGB1/RAGE axis in inflammatory diseases. Molecules 27:7311. doi: 10.3390/molecules27217311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Taverna S, Tonacci A, Ferraro M, Cammarata G, Cuttitta G, Bucchieri S, Pace E, Gangemi S. 2022. High Mobility Group Box 1: biological functions and relevance in oxidative stress related chronic diseases. Cells 11:849. doi: 10.3390/cells11050849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Coughlan L. 2020. Factors which contribute to the immunogenicity of non-replicating adenoviral vectored vaccines. Front Immunol 11:909. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yang H, Liu H, Zeng Q, Imperato GH, Addorisio ME, Li J, He M, Cheng KF, Al-Abed Y, Harris HE, Chavan SS, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. 2019. Inhibition of HMGB1/RAGE-mediated endocytosis by HMGB1 antagonist box A, anti-HMGB1 antibodies, and cholinergic agonists suppresses inflammation. Mol Med 25:13. doi: 10.1186/s10020-019-0081-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mennechet FJD, Paris O, Ouoba AR, Salazar Arenas S, Sirima SB, Takoudjou Dzomo GR, Diarra A, Traore IT, Kania D, Eichholz K, Weaver EA, Tuaillon E, Kremer EJ. 2019. A review of 65 years of human adenovirus seroprevalence. Expert Rev Vaccines 18:597–613. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1588113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Coughlan L., Alba R, Parker AL, Bradshaw AC, McNeish IA, Nicklin SA, Baker AH. 2010. Tropism-modification strategies for targeted gene delivery using adenoviral vectors. Viruses 2:2290–2355. doi: 10.3390/v2102290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Coughlan Lynda, Kremer EJ, Shayakhmetov DM. 2022. Adenovirus-based vaccines-a platform for pandemic preparedness against emerging viral pathogens. Mol Ther 30:1822–1849. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bulcha JT, Wang Y, Ma H, Tai PWL, Gao G. 2021. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6:53. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00487-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg 27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bradshaw AC, Parker AL, Duffy MR, Coughlan L, van Rooijen N, Kähäri V-M, Nicklin SA, Baker AH. 2010. Requirements for receptor engagement during infection by adenovirus complexed with blood coagulation factor X. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001142. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Richardson JY, Ottolini MG, Pletneva L, Boukhvalova M, Zhang S, Vogel SN, Prince GA, Blanco JCG. 2005. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection induces cyclooxygenase 2: a potential target for RSV therapy. J Immunol 174:4356–4364. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Heim A, Ebnet C, Harste G, Pring-Akerblom P. 2003. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. J Med Virol 70:228–239. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Echavarria M, Forman M, Ticehurst J, Dumler JS, Charache P. 1998. PCR method for detection of adenovirus in urine of healthy and human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Clin Microbiol 36:3323–3326. doi: 10.1128/JCM.36.11.3323-3326.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shirey KA, Cole LE, Keegan AD, Vogel SN. 2008. Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain induces macrophage alternative activation as a survival mechanism. J Immunol 181:4159–4167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shirey KA, Pletneva LM, Puche AC, Keegan AD, Prince GA, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. 2010. Control of RSV-induced lung injury by alternatively activated macrophages is IL-4Rα-, TLR4-, and IFN-b-dependent. Mucosal Immunol 3:291–300. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Blanco JCG, Cullen LM, Kamali A, Sylla FYD, Chinmoun Z, Boukhvalova MS, Morrison TG. 2022. Correlative outcomes of maternal immunization against RSV in cotton rats. Hum Vaccin Immunother 18:2148499. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2148499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 and Fig. S1 to S3.

Data Availability Statement

All primary data from which the figures in this paper and the supplemental materials are deposited in the OSF public database at https://osf.io/dgyxw/. All novel materials described will be provided through a licensing agreement or a materials transfer agreement with the University of Maryland, Baltimore.