Abstract

Background

Synchronous multiple primary colorectal cancer (SMPCC) is a rare subtype of CRC, characterized by the presence of two or more primary CRC lesions simultaneously or within 6 months from the detection of the first lesion. We aim to develop a novel nomogram to predict OS and CSS for SMPCC patients using data from the SEER database.

Methods

The clinical variables and survival data of SMPCC patients between 2004 and 2018 were retrieved from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to screen the enrolled patients. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to identify the independent risk factors for OS and CSS. The performance of the nomogram was evaluated using the concordance index (C-index), calibration curves, and the area under the curve (AUC) of a receiver operating characteristics curve (ROC). A decision curve analysis (DCA) was generated to compare the net benefits of the nomogram with those of the TNM staging system.

Results

A total of 6772 SMPCC patients were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to the training (n = 4670) and validation (n = 2002) cohorts. Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed that race, marital status, age, histology, tumor position, T stage, N stage, M stage, chemotherapy, and the number of dissected LNs were independent prognostic factors.The C-index values for OS and CSS prediction were 0.716 (95% CI 0.705–0.727) and 0.718 (95% CI 0.702–0.734) in the training cohort, and 0.760 (95% CI 0.747–0.773) and 0.749 (95% CI 0.728–0.769) in the validation cohort. The ROC and calibration curves indicated that the model had good stability and reliability. Decision curve analysis revealed that the nomograms provided a more significant clinical net benefit than the TNM staging system.

Conclusion

We developed a novel nomogram for clinicians to predict OS and CSS, which could be used to optimize the treatment in SMPCC patients.

Keywords: Synchronous multiple primary colorectal cancer, Overall survival, Cancer-specific survival, Nomogram, SEER

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC), the most prevalent malignancy affecting the gastrointestinal tract, ranks as the third most common cancer worldwide in terms of incidence, while its mortality rate stands as the second highest (Siegel et al. 2022). Multiple primary CRC (MPCC) represents a rare variant within the spectrum of CRC, with incidence rates ranging from 1.2 to 8.4% (Leersum et al. 2014; Lam et al. 2011). MPCC is characterized by the simultaneous or sequential emergence of two or more histologically confirmed primary CRC lesions in a single patient (Yoon et al. 2008). Delineating the temporal diagnostic interval, MPCC can be further classified into synchronous MPCC (SMPCC) when the interval less than 6 months or metachronous MPCC (MMPCC) when the interval exceeds six months. Current understanding of the pathogenesis underlying SMPCC remains inconclusive; however, extant literature posits smoking, concurrent adenomatous growths, Lynch syndrome, ulcerative colitis, and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) as potential risk factors associated with SMPCC (Hu et al. 2013; Drew et al. 2017; Lindberg et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2012; Lam et al. 2014). As advancements in colonic endoscopy and computed tomography colonography (CTC) bolster diagnostic sensitivity (Flor et al. 2018), the prevalence of SMPCC has surged, necessitating heightened attention. To date, considerable insights into the prognosis and management of single primary CRC (SPCRC) have been gained. Notably, nomogram-based predictive models derived from extensive databases such as Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) and Adjuvant Colon Cancer End Points (ACCENT) (Renfro et al. 2014; Weiser et al. 2011) have demonstrated notable efficacy in prognosticating CRC outcomes. Nevertheless, the scarcity of SMPCC-related prognostic research, coupled with significant clinical, pathological, surgical, postoperative monitoring, and etiological differences between SMPCC and SPCRC (Wu et al. 2017), renders these models unsuitable for application in SMPCC patients. Furthermore, the lack of reliable prognostic tools and survival prediction systems underscores the pressing need to establish an accurate prognostic model tailored to SMPCC patients.

Considering the limited prevalence of SMPCC, our study centered on a cohort of SMPCC patients sourced from the SEER database. Through meticulous screening, we sought to identify prognostic factors specific to SMPCC, culminating in the development of prognostic nomograms for this distinct CRC subtype. By leveraging these nomograms, we endeavored to predict overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS), engendering a heightened comprehension of this exceptional CRC subtype while furnishing clinicians with invaluable prognostic insights into survival prediction and individualized therapeutic regimens.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The SEER database, a publicly accessible resource maintained by the National Cancer Institute in the United States, comprises cancer incidence and survival data collected from 18 established cancer registries across the nation. This extensive database effectively captures information pertaining to approximately 30% of the entire American population. As a publicly accessible resource, the utilization of the SEER database obviates the need for explicit patient consent. Furthermore, it is imperative to emphasize that the present study adhered to all relevant ethical standards, ensuring compliance with the ethical tenets enshrined in the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Screen of SMPCC patients from SEER database

CRC patients diagnosed between 2004 to 2018 were retrieved from the SEER database using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3) codes 18.0–18.7, 19.9, and 20.9 to identify colorectal cancer sites. Inclusion criteria for SMPCC were as follows: (1) diagnosis between 2004 and 2018; (2) two or more primary CRC lesions diagnosed in a single patient; (3) histopathological confirmation of CRC for multiple primary lesions; (4) age > 18 years; (5) diagnostic interval between the second and first primary lesions ≤ 6 months. Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of other malignancies; (2) carcinoma in situ; (3) unknown or less than one month of survival time; (4) no surgical treatment received; (5) unavailable information on the T stage, N stage, M stage, tumor location, and survival; (6) patients diagnosed only by autopsy or death certificate.

Study variables

The variables extracted for each case from the SEER database encompassed various parameters, including age, marital status, race, grade, T stage, N stage, M stage, tumor size, tumor number, histology, the number of lymph nodes dissected (no. of LNs dissected), chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Tumor location was categorized into distinct subgroups: right-sided colon (C18.0–18.4) and left-sided colon (C18.5–18.7, C19.9, and C20.9). Based on the positional relationship between multiple tumors, patients were stratified into two groups: unilateral group (comprising cases with tumors on the same side, either left or right) and bilateral group (comprising cases with tumors on both sides). The lesion with the most advanced stage or size among the multiple lesions was used as the index tumor for analysis. The primary outcomes in this study were overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Statistical analysis

A random allocation method was used to allocate all enrolled SMPCC patients into a training cohort and a validation cohort, with a ratio of 7:3. The categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages (N, %), and the differences in the distribution of the variables between the training and validation cohorts were assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test. The training cohort was utilized as the study cohort for univariate and multivariate Cox analyses using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. These analyses aimed to identify independent prognostic factors and ascertain their respective hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Significant variables obtained from the multivariate analysis were integrated to construct a prognostic nomogram, enabling the prediction of 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates for SMPCC patients. The nomogram's performance was assessed through calibration curves with a 1000-times bootstrapping, comparing the predicted and observed survival rates in both the training and validation cohorts. The concordance index (C-index) was employed to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram. The area under the curve (AUC) with the 95% confidence interval (CI) of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated to evaluate the discrimination ability of the nomogram. The area under the roc curve (AUC) value > 0.7 was considered to have good predictive capabilities. Decision curves analysis (DCA) were generated to compare the net benefits of the nomogram with those of the TNM staging system. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value below 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.2.

Results

Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of SMPCC patients

A comprehensive search of the SEER database from 2004 to 2018 yielded 6672 SMPCC patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A detailed flowchart depicting the patient selection process is presented in Fig. 1. The majority of patients were of white ethnicity (N = 5318, 79.70%), with 3,730 male cases (55.91%) and 2,942 female cases (44.09%). Among all cases, 6108 (91.55%) had two primary lesions, while 564 (8.45%) exhibited three or more primary lesions. Unilateral group were observed in 3491 cases (52.32%), whereas bilateral group were present in 3181 cases (47.68%). The distribution of tumor stages was as follows: Stage I (N = 1090, 16.34%), Stage II (N = 2048, 30.69%), Stage III (N = 2538, 38.04%), and Stage IV (N = 996, 14.93%). Radiotherapy and chemotherapy were administered in 817 cases (12.25%) and 2677 cases (40.12%), respectively. To establish a training cohort (N = 4670) and a validation cohort (N = 2002), we randomly allocated the 6672 enrolled patients in a ratio of 7:3. Notably, the distribution of all included variables exhibited no statistically significant differences between the training and validation cohorts. The demographic and clinical features of the SMPCC patients in the training and validation cohorts are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart illustrating the SMPCC patient selection process

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the training and validation cohorts

| Variables | Training cohort (N = 4670) | Validation cohort (N = 2002) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.849 | ||

| < 60 | 1220 (26.12%) | 541 (27.02%) | |

| 60–69 | 1140 (24.41%) | 474 (23.68%) | |

| 70–79 | 1281 (27.43%) | 543 (27.12%) | |

| ≥ 80 | 1029 (22.03%) | 444 (22.18%) | |

| Sex | 0.210 | ||

| Female | 2083 (44.60%) | 859 (42.91%) | |

| Male | 2587 (55.40%) | 1143 (57.09%) | |

| Race | 0.298 | ||

| White | 3736 (80.00%) | 1582 (79.02%) | |

| Black | 521 (11.16%) | 243 (12.14%) | |

| Other | 413 (8.84%) | 176 (8.79%) | |

| Marital status | 0.966 | ||

| Married | 2426 (51.95%) | 1034 (51.65%) | |

| Unmarried | 2048 (43.85%) | 882 (44.06%) | |

| Unknown | 196 (4.20%) | 86 (4.30%) | |

| Tumor postion | 0.929 | ||

| Unilateral group | 2441 (52.29%) | 1050 (52.45%) | |

| Bilateral group | 2227 (47.71%) | 952 (47.55%) | |

| Tumor number | 0.903 | ||

| 2 | 4277 (91.58%) | 1831 (91.46%) | |

| ≥ 3 | 393 (8.42%) | 171 (8.54%) | |

| Grade | 0.144 | ||

| Well/moderately | 3368 (72.12%) | 1403 (70.08%) | |

| Poorly | 805 (17.24%) | 376 (18.78%) | |

| Undifferentiated | 155 (3.32%) | 57 (2.85%) | |

| Unknown | 342 (7.32%) | 166 (8.29%) | |

| Histology | 0.268 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 4014 (85.95%) | 1739 (86.86%) | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 582 (12.46%) | 241 (12.04%) | |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 74 (1.58%) | 22 (1.10%) | |

| Tumor size | 0.283 | ||

| ≤ 50 | 2554 (54.69%) | 1094 (54.65%) | |

| > 50 | 1803 (38.61%) | 753 (37.61%) | |

| Unknown | 313 (6.70%) | 155 (7.74%) | |

| T stage | 0.358 | ||

| T1 | 405 (8.67%) | 189 (9.44%) | |

| T2 | 596 (12.76%) | 272 (13.59%) | |

| T3 | 2896 (62.01%) | 1196 (59.74%) | |

| T4 | 773 (16.55%) | 345 (17.23%) | |

| N stage | 0.161 | ||

| N0 | 2331 (49.91%) | 1007 (50.30%) | |

| N1 | 1404 (30.06%) | 632 (31.57%) | |

| N2 | 935 (20.02%) | 363 (18.13%) | |

| M stage | 0.241 | ||

| M0 | 3989 (85.42%) | 1687 (84.27%) | |

| M1 | 681 (14.58%) | 315 (15.73%) | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.893 | ||

| Yes | 574 (12.29%) | 243 (12.14%) | |

| No/unknown | 4096 (87.71%) | 1759 (87.86%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.672 | ||

| Yes | 1882 (40.30%) | 795 (39.71%) | |

| No/unknown | 2788 (59.70%) | 1207 (60.29%) | |

| No of LNs dissected | 0.175 | ||

| ≥ 12 | 3730 (79.87%) | 1569 (78.37%) | |

| < 12 | 940 (20.13%) | 433 (21.63%) |

Independent prognostic factors for OS and CSS

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on the training cohort to evaluate the influence of various factors on overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). The results of univariate survival analysis demonstrated that race, marital status, age, tumor position, grade, histology, tumor size, T stage, N stage, M stage, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and no. of LNs dissected were identified as potential prognostic factors for OS (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Further multivariate analysis confirmed that race, marital status, age, histology, tumor location, T stage, N stage, M stage, chemotherapy, and no. of LNs dissected were independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 2). Univariate survival analysis revealed that tumor number, marital status, age, tumor position, grade, histology, tumor size, T stage, N stage, M stage, chemotherapy, and the number of dissected LNs were identified as potential prognostic factors for CSS (Table 3). Subsequent multivariate analysis determined that marital status, age, tumor position, T stage, N stage, M stage, chemotherapy, and no. of LNs dissected were independent prognostic factors for CSS.

Table 2.

The univariable and multivariate Cox regression analysis of OS

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | ||||

| < 60 | Reference | |||

| 60–69 | 1.44 (1.27–1.64) | < 0.001 | 1.55 (1.36–1.76) | < 0.001 |

| 70–79 | 1.98 (1.76–2.23) | < 0.001 | 2.26 (2.00–2.55) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 80 | 3.08 (2.73–3.47) | < 0.001 | 3.34 (2.94–3.81) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.95 (0.87–1.02) | 0.162 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.97 (0.86–1.1) | 0.661 | 1.05 (0.93–1.20) | 0.417 |

| Other | 0.77 (0.66–0.9) | 0.001 | 0.83 (0.71–0.97) | 0.017 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | Reference | |||

| Unmarried | 1.41 (1.30–1.53) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.14–1.34) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.2 (0.98–1.48) | 0.077 | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) | 0.447 |

| Tumor position | ||||

| Unilateral group | Reference | |||

| Bilateral group | 1.1 (1.02–1.19) | 0.017 | 1.1 (1.02–1.19) | 0.017 |

| Tumor number | ||||

| 2 | Reference | |||

| ≥ 3 | 1.12 (0.97–1.28) | 0.12 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| Well/moderately | Reference | |||

| Poorly | 1.2 (1.09–1.33) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | 0.848 |

| Undifferentiated | 1.36 (1.10–1.70) | 0.005 | 1.13 (0.90–1.41) | 0.299 |

| Unknown | 1.03 (0.85–1.26) | 0.753 | 0.97 (0.79–1.18) | 0.747 |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | Reference | |||

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) | 0.336 | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | 0.6 |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 1.5 (1.12–2.01) | 0.006 | 1.37 (1.01–1.86) | 0.042 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤ 50 | Reference | |||

| > 50 | 1.17 (1.07–1.27) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 0.214 |

| Unknown | 0.91 (0.77–1.07) | 0.252 | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | 0.515 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | |||

| T2 | 1.36 (1.12–1.66) | 0.002 | 1.24 (1.01–1.52) | 0.039 |

| T3 | 1.79 (1.51–2.11) | < 0.001 | 1.4 (1.17–1.68) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 2.93 (2.44–3.52) | < 0.001 | 2.03 (1.65–2.49) | < 0.001 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 1.36 (1.23–1.49) | < 0.001 | 1.5 (1.36–1.66) | < 0.001 |

| N2 | 1.97 (1.79–2.18) | < 0.001 | 2.02 (1.80–2.27) | < 0.001 |

| M stage | ||||

| M0 | Reference | |||

| M1 | 3.47 (3.15–3.82) | < 0.001 | 3.42 (3.07–3.82) | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) | 0.001 | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 0.637 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 1.22 (1.12–1.32) | < 0.001 | 1.54 (1.39–1.70) | < 0.001 |

| No of LNs dissected | ||||

| ≥ 12 | Reference | |||

| < 12 | 1.16 (1.06–1.28) | 0.001 | 1.24 (1.13–1.37) | < 0.001 |

Table 3.

The univariable and multivariate Cox regression analysis of CSS

| Variables | Univariate alysis | Multivariate alysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | ||||

| < 60 | Reference | |||

| 60–69 | 1.25 (1.08–1.45) | 0.003 | 1.45 (1.25–1.68) | < 0.001 |

| 70–79 | 1.34 (1.16–1.54) | < 0.001 | 1.69 (1.46–1.97) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 80 | 1.7 (1.47–1.98) | < 0.001 | 2.23 (1.89–2.62) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.492 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.07 (0.92–1.26) | 0.379 | ||

| Other | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 0.824 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | Reference | |||

| Unmarried | 1.31 (1.18–1.46) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.11–1.38) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.11 (0.85–1.46) | 0.431 | 1.06 (0.81–1.39) | 0.668 |

| Tumor postion | ||||

| Unilateral group | Reference | |||

| Bilateral group | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) | 0.008 | 1.11 (1.00–1.23) | 0.048 |

| Tumor number | ||||

| 2 | Reference | |||

| ≥ 3 | 1.22 (1.03–1.45) | 0.022 | 1.14 (0.95–1.36) | 0.150 |

| Grade | ||||

| Well/moderately | Reference | |||

| Poorly | 1.37 (1.2–1.55) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (0.90–1.17) | 0.713 |

| Undifferentiated | 1.77 (1.38–2.27) | < 0.001 | 1.31 (1.01–1.69) | 0.041 |

| Unknown | 1.02 (0.78–1.32) | 0.900 | 0.91 (0.70–1.19) | 0.508 |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | Reference | |||

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1.01 (0.86–1.17) | 0.949 | 0.88 (0.75–1.03) | 0.117 |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 1.63 (1.14–2.32) | 0.007 | 1.08 (0.74–1.57) | 0.679 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤ 50 | Reference | |||

| > 50 | 1.31 (1.18–1.46) | < 0.001 | 1.1 (0.99–1.23) | 0.079 |

| Unknown | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) | 0.138 | 1.05 (0.83–1.33) | 0.695 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | |||

| T2 | 1.15 (0.83–1.6) | 0.406 | 1.04 (0.74–1.46) | 0.808 |

| T3 | 2.7 (2.07–3.52) | < 0.001 | 1.75 (1.32–2.32) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 5.45 (4.13–7.2) | < 0.001 | 2.65 (1.96–3.58) | < 0.001 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 2.28 (2.01–2.59) | < 0.001 | 2.16 (1.88–2.47) | < 0.001 |

| N2 | 3.86 (3.4–4.39) | < 0.001 | 3.05 (2.63–3.54) | < 0.001 |

| M stage | ||||

| M0 | Reference | |||

| M1 | 5.49 (4.91–6.13) | < 0.001 | 4.15 (3.67–4.70) | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 1.05 (0.90–1.23) | 0.508 | 0.94 (0.80–1.11) | 0.481 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 0.8 (0.72–0.88) | < 0.001 | 1.45 (1.29–1.64) | < 0.001 |

| No of LNs dissected | ||||

| ≥ 12 | Reference | |||

| < 12 | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) | 0.011 | 1.36 (1.20–1.54) | < 0.001 |

Development and evaluation of the novel prognostic model

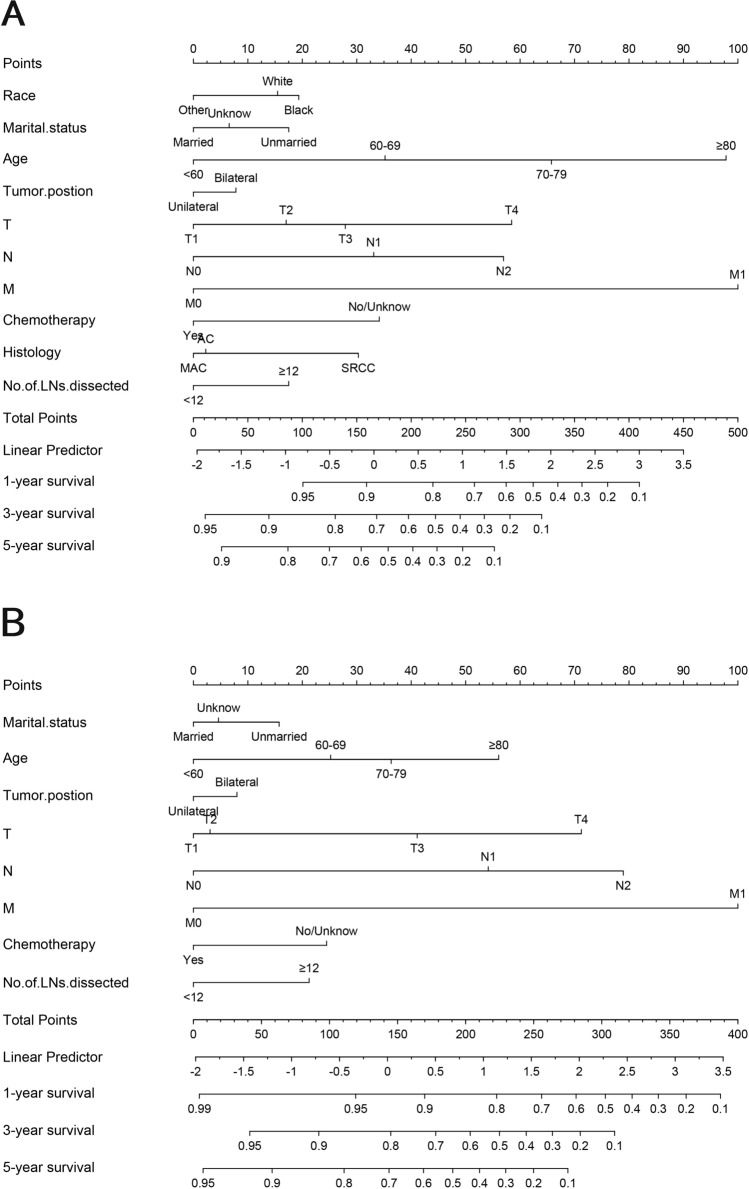

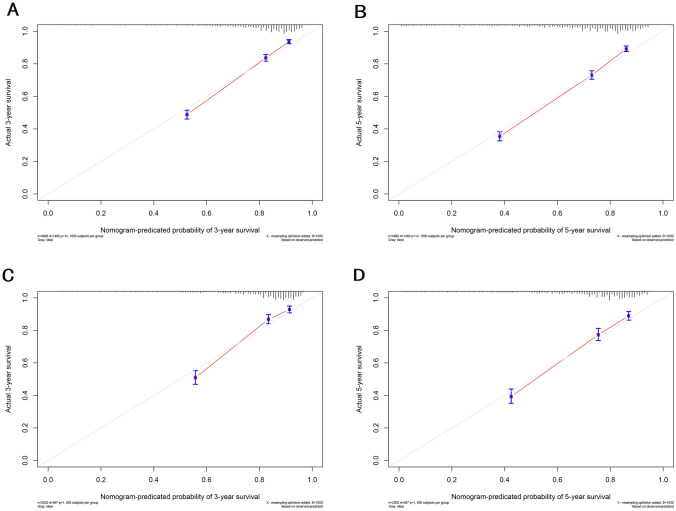

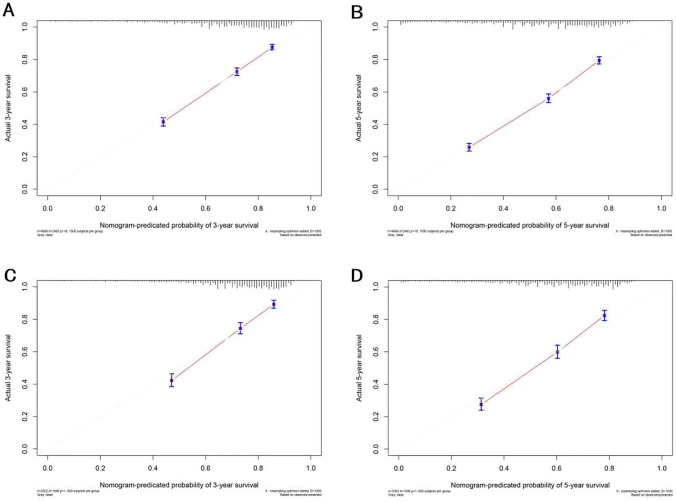

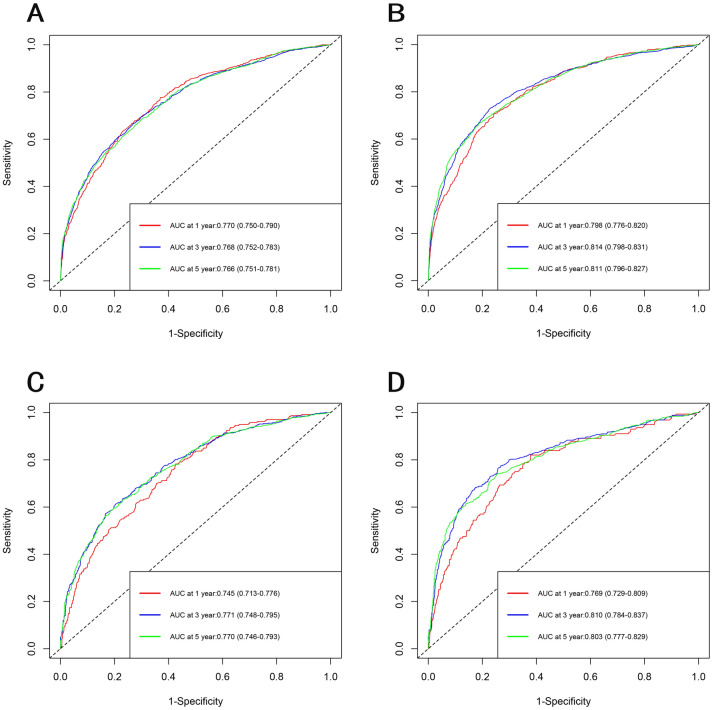

The selected variables were incorporated to develop nomograms for predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) (Fig. 2). The constructed nomograms exhibited excellent predictive performance in the training and validation cohorts. The C-index values for OS and CSS prediction were 0.716 (95% CI 0.705–0.727) and 0.718 (95% CI 0.702–0.734) in the training cohort, respectively. Likewise, the C-index values for OS and CSS prediction were 0.760 (95% CI 0.747–0.773) and 0.749 (95% CI 0.728–0.769) in the validation cohort, respectively. These results confirmed the robust discriminative ability of the nomograms for predicting OS and CSS. Furthermore, the calibration curves of the nomograms demonstrated optimal agreement between predicted survival and observed survival at 3 and 5 years in both training and validation cohorts, aligning closely with the 45-degree diagonal line (Figs. 3, 4). The ROC curves demonstrated that the nomograms' predictive performance for OS in the training cohort yielded AUC values of 0.770 (95% CI 0.750–0.790), 0.768 (95% CI 0.752–0.783), and 0.766 (95% CI 0.751–0.781) at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. In the validation cohort, the AUC values for OS were 0.745 (95% CI 0.713–0.776), 0.771 (95% CI 0.748–0.795), and 0.770 (95% CI 0.746–0.793) at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. In the training cohort, the nomograms for CSS achieved AUC values of 0.798 (95% CI 0.776–0.820), 0.814 (95% CI 0.798–0.831), and 0.811 (95% CI 0.796–0.827) at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. The AUC values in the validation cohort for CSS were 0.769 (95% CI 0.729–0.809), 0.810 (95% CI 0.784–0.837), 0.803 (95% CI 0.777–0.829), at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively (Fig. 5). Additionally, decision curve analysis revealed that the nomograms provided a more significant clinical net benefit than the TNM staging system, indicating their superior clinical applicability (Fig. 6).

Fig. 2.

Nomogram for predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year OS (a) and CSS (b) for patients diagnosed with SMPCC. The top row is the point assignment for each prognostic variable. For an single patient, each prognostic variable corresponds to a point on the first row. Add the points of each prognostic variable and place the total point on the total points axis. Vertical lines drawn from the total points scale show the corresponding 3- and 5-year OS and CSS

Fig. 3.

Calibration curves of nomograms for OS in the training cohort and validation cohort. a 3-year calibration curve of OS in the training cohort. b 5-Year calibration curve of OS in the training cohort. c 3-Year calibration curve of OS in the validation cohort. d 5-Year calibration curve of OS in the validation cohort. The calibration curves exhibit a close proximity to the 45° line, indicating a strong agreement between the predicted probabilities and the observed probabilities

Fig. 4.

Calibration curves of nomograms for CSS in the training cohort and validation cohort. a 3-Year calibration curve of CSS in the training cohort. b 5-Year calibration curve of CSS in the training cohort. c 3-Year calibration curve of CSS in the validation cohort. d 5-Year calibration curve of CSS in the validation cohort. The calibration curves exhibit a close proximity to the 45° line, indicating a strong agreement between the predicted probabilities and the observed probabilities

Fig. 5.

The ROC curves of nomograms for OS and CSS in the training cohort and validation cohort. a ROC curve of OS in the training cohort. b ROC curve of CSS in the training cohort. c ROC curve of OS in the validation cohort. d ROC curve of CSS in the validation cohort. ROC curves indicate that the nomogram showed satisfactory discriminative ability

Fig. 6.

The decision curve analysis (DCA) curve of nomograms for OS and CSS in the training cohort and validation cohort. a DCA curve of OS in the training cohort. b DCA curve of CSS in the training cohort. c DCA curve of OS in the validation cohort. d DCA curve of CSS in the validation cohort. The DCA curves of nomograms indicated that the nomograms (purple line) had a superior clinical net value than the TNM staging system (blue line)

Discussion

The prevalence of SMPCC in CRC ranges from 1.2% to 8.4% (Leersum et al. 2014; Lam et al. 2011). As the incidence of CRC continues to rise and diagnostic techniques advanced, the rate of SMPCC has gradually increased. One of the main reasons for missed detection of multiple primary lesions is tumor obstruction, which hinders comprehensive examination of the entire colon during a colonoscopy. Therefore, it is advisable for such patients to undergo computed tomography colonography (CTC) or intraoperative colonoscopy (Flor et al. 2020; Park et al. 2012; Chin et al. 2019) to avoid overlooking multiple primary lesions and compromising patient survival. SMPCC exhibits differences from SPCRC regarding clinical pathology, etiology, surgical resection extent, and prognosis. Several studies have demonstrated that SMPCC is more prevalent among males and elderly individuals (Leersum et al. 2014; Lam et al. 2011, 2014; Yoon et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2013; Drew et al. 2017; Lindberg et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2012; Flor et al. 2018, 2020; Renfro et al. 2014; Weiser et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2017; Park et al. 2012; Chin et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2011), with a higher proportion of mucinous adenocarcinoma (Arakawa et al. 2018). Furthermore, SMPCC is closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), Lynch syndrome, and other hereditary colorectal diseases (Lindberg et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2012; Lam et al. 2014). Currently, limited research on the prognosis of SMPCC exists, and conflicting findings are present. Most studies suggest that SMPCC has a worse prognosis compared to SPCRC (Oya et al. 2003; He et al. 2019), while others argue for no significant difference in prognosis between SMPCC and SPCRC (Mulder et al. 2011; Ochiai et al. 2021). Considering the unique clinical and pathological characteristics of SMPCC, it is imperative for future investigations to meticulously account for confounding factors such as age, TNM stage, histological type, and microsatellite status in order to facilitate an unbiased assessment of SMPCC prognosis. At present, no standardized treatment guidelines for SMPCC have been established. Surgery remains the primary treatment approach for SMPCC. Different from SPCRC, SMPCC necessitates tailored surgical strategies based on the location of multiple lesions. For patients with multiple lesions in adjacent segments of the intestine, an expanded resection approach can be adopted (Bos et al. 2018). Patients with lesions located in different segments of the intestine and at considerable distances from each other may benefit from segmental resection or broader surgical resection options (Easson et al. 2002; Holubar et al. 2010). Notably, for patients with multiple tumor lesions across various intestinal locations, inflammatory bowel disease or FAP, most studies recommend a larger-scale surgical resection approach such as subtotal or total colectomy to mitigate the risk of MMPCC development (Oya et al. 2003; He et al. 2019; Mulder et al. 2011; Ochiai et al. 2021; Bos et al. 2018; Easson et al. 2002; Holubar et al. 2010; Riegler et al. 2003).

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation into the prognosis prediction of SMPCC. Through a comprehensive analysis of a large dataset from the SEER database, encompassing 6672 SMPCC patients, we identified 10 prognostic factors associated with SMPCC prognosis. Based on these factors, we developed novel prognostic nomograms capable of accurately predicting 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS and CSS. Notably, our nomograms demonstrated excellent predictive performance in the training and validation cohorts. The utilization of this predictive model holds promising implications for clinicians, as it enables accurate survival predictions for individual SMPCC patients, facilitating informed decision-making regarding treatment strategies and follow-up plans.

The TNM staging system is the cornerstone for assessing the prognosis of CRC. Numerous studies utilizing large-scale population databases have incorporated TNM stages into prognostic models for CRC (Renfro et al. 2014; Weiser et al. 2011). Consistent with previous research findings, our study confirmed that higher T, N, and M stages are associated with shorter OS and CSS in patients with SMPCC. It is important to note that the final stage for SMPCC should be determined based on the highest TNM stage among multiple lesions. Additionally, our study identified chemotherapy as a protective factor for OS and CSS in SMPCC patients. Given the greater tumor burden in SMPCC than in SPCRC, adjuvant chemotherapy has been recommended in previous studies (Chen et al. 2016). Nonetheless, further research is warranted to determine whether SMPCC should be considered a high-risk factor necessitating chemotherapy in stage II patients.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines emphasize the importance of adequate lymph node retrieval during curative surgery for CRC. The guidelines recommend examining a minimum of 12 lymph nodes to ensure accurate pathological staging and enhance patient prognosis (Kotake et al. 2012; Duraker et al. 2014). Our study findings corroborated these recommendations, demonstrating that sufficient retrieved lymph nodes significantly improved OS and CSS outcomes in SMPCC patients. Furthermore, our investigation identified advanced age as a significant risk factor for OS and CSS. Elderly patients often exhibit lower physical fitness scores and a higher incidence of complications such as perforation and obstruction. Additionally, they are more susceptible to postoperative complications, which may hinder timely access to other therapeutic interventions. These factors likely contribute to the inferior prognosis observed in older individuals compared with their younger counterparts (Khattak et al. 2012; Dekker et al. 2014). Tumor position is also a prognostic predictor of OS and CSS, and the prognosis of the bilateral group is worse than that of the unilateral group, which may be because the multiple tumor lesions of the bilateral group are located in the left and right colon and often receive a wider range of surgical resection.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, it is essential to note that the training and validation cohorts used in this study were exclusively derived from the SEER database. Therefore, it is crucial to validate the generalizability of the nomogram by examining its applicability in diverse patient populations from multiple centers. Secondly, due to the inherent limitations of the SEER database, certain essential prognostic factors were unavailable for analysis, including information on distant metastasis sites, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), specific radiotherapy or chemotherapy protocols, and genetic mutations. The absence of these variables impacted the comprehensive evaluation of prognostic indicators. Lastly, as with any retrospective study based on existing data, unavoidable biases, including selection biases, must be acknowledged, which can influence the observed outcomes.

Conclusion

For the diagnosis and treatment of SMPCC patients, clinicians should make full use of computed tomography colonography or intraoperative colonoscopy to minimize the missed diagnosis rate of SMPCC. Based on the location of the tumors and hereditary colorectal disease, the clinicians chooses the appropriate surgical strategies, combined with postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy, targeted therapy and other means to improve the prognosis of SMPCC patients. In this study, we developed a novel nomogram to predict OS and CSS for SMPCC patients using data from the SEER database. The nomogram achieved satisfactory discrimination and calibration in both training and validation cohorts. The nomogram helps clinicians to predict individualized survival and optimize the treatment in SMPCC patients.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: XZ, BM. Data curation: XZ, CL, YH. Formal analysis: YH, JZ, WR. Writing—original draft: XZ, BM, KD. Writing—review and editing: KD, WR, BM.

Funding

No funding support.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database at http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arakawa K, Hata K, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Tanaka T, Nishikawa T et al (2018) Prognostic significance and clinicopathological features of synchronous colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 38(10):5889–5895. 10.21873/anticanres.12932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos ACRK, Matthijsen RA, van Erning FN, van Oijen MGH, Rutten HJT, Lemmens VEPP (2018) Treatment and outcome of synchronous colorectal carcinomas: a nationwide study. Ann Surg Oncol 25(2):414–421. 10.1245/s10434-017-6255-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L,Yulin G, Guijin C,Yanbing J,Yu W,Zimeng L et al (2016) Clinical analysis of synchronous multiple primary colorectal carcinomas. Acad J Chin PLA Med Sch 37(07):735–738. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3275.r.20160330.1041.004.html

- Chin CC, Kuo YH, Chiang JM (2019) Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: predisposing factors and characteristics. Colorectal Dis 21(4):432–440. 10.1111/codi.14539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker JW, Gooiker GA, Bastiaannet E, van den Broek CB, van der Geest LG, van de Velde CJ et al (2014) Cause of death the first year after curative colorectal cancer surgery; a prolonged impact of the surgery in elderly colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 40(11):1481–1487. 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew DA, Nishihara R, Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Qian ZR, Mima K et al (2017) A prospective study of smoking and risk of synchronous colorectal cancers. Am J Gastroenterol 112(3):493–501. 10.1038/ajg.2016.589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraker N, Civelek Çaynak Z, Hot S (2014) The prognostic value of the number of lymph nodes removed in patients with node-negative colorectal cancer. Int J Surg (Lond, Engl) 12(12):1324–1327. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easson AM, Cotterchio M, Crosby JA, Sutherland H, Dale D, Aronson M et al (2002) A population-based study of the extent of surgical resection of potentially curable colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 9(4):380–387. 10.1007/BF02573873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor N, Zanchetta E, Di Leo G, Mezzanzanica M, Greco M, Carrafiello G et al (2018) Synchronous colorectal cancer using CT colonography vs other means: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom Radiol (n y) 43(12):3241–3249. 10.1007/s00261-018-1658-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor N, Ceretti AP, Luigiano C, Brambillasca P, Savoldi AP, Verrusio C et al (2020) Performance of CT colonography in diagnosis of synchronous colonic lesions in patients with occlusive colorectal cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 214(2):348–354. 10.2214/AJR.19.21810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Zheng C, Wang Y, Dan J, Zhu M, Wei M, Wang J, Wang Z (2019) Prognosis of synchronous colorectal carcinoma compared to solitary colorectal carcinoma: a matched pair analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 31(12):1489–1495. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holubar SD, Wolff BG, Poola VP, Soop M (2010) Multiple synchronous colonic anastomoses: are they safe? Colorectal Dis 12(2):135–140. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Chang DT, Nikiforova MN, Kuan SF, Pai RK (2013) Clinicopathologic features of synchronous colorectal carcinoma: a distinct subset arising from multiple sessile serrated adenomas and associated with high levels of microsatellite instability and favorable prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol 37(11):1660–1670. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31829623b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattak MA, Townsend AR, Beeke C, Karapetis CS, Luke C, Padbury R (2012) Impact of age on choice of chemotherapy and outcome in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer (Oxf, Engl, 1990) 48(9):1293–1298. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake K, Honjo S, Sugihara K, Hashiguchi Y, Kato T, Kodaira S et al (2012) Number of lymph nodes retrieved is an important determinant of survival of patients with stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 42(1):29–35. 10.1093/jjco/hyr164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AK, Carmichael R, Gertraud Buettner P, Gopalan V, Ho YH, Siu S (2011) Clinicopathological significance of synchronous carcinoma in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg 202(1):39–44. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AK, Chan SS, Leung M (2014) Synchronous colorectal cancer: clinical, pathological and molecular implications. World J Gastroenterol 20(22):6815–6820. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LJ, Wegen-Haitsma W, Ladelund S, Smith-Hansen L, Therkildsen C, Bernstein I et al (2019) Risk of multiple colorectal cancer development depends on age and subgroup in individuals with hereditary predisposition. Fam Cancer 18(2):183–191. 10.1007/s10689-018-0109-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Goldblum JR, Zhao Z, Landau M, Heald B, Pai R et al (2012) Distinct clinicohistologic features of inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal adenocarcinoma: in comparison with sporadic microsatellite-stable and Lynch syndrome-related colorectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 36(8):1228–1233. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318253645a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder SA, Kranse R, Damhuis RA, de Wilt JH, Ouwendijk RJ, Kuipers EJ et al (2011) Prevalence and prognosis of synchronous colorectal cancer: a Dutch population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol 35(5):442–447. 10.1016/j.canep.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai K, Kawai K, Nozawa H, Sasaki K, Kaneko M, Murono K et al (2021) Prognostic impact and clinicopathological features of multiple colorectal cancers and extracolorectal malignancies: a nationwide retrospective study. Digestion 102(6):911–920. 10.1159/000517271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oya M, Takahashi S, Okuyama T, Yamaguchi M, Ueda Y (2003) Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: clinico-pathological features and prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 33(1):38–43. 10.1093/jjco/hyg010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Lee JH, Lee SS, Kim JC, Yu CS, Kim HC et al (2012) CT colonography for detection and characterisation of synchronous proximal colonic lesions in patients with stenosing colorectal cancer. Gut 61(12):1716–1722. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro LA, Grothey A, Xue Y, Saltz LB, André T, Twelves C et al (2014) ACCENT- based web calculators to predict recurrence and overall survival in stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 106(12):dju333. 10.1093/jnci/dju333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegler G, Bossa F, Caserta L, Pera A, Tonelli F, Sturniolo GC et al (2003) Colorectal cancer and high grade dysplasia complicating ulcerative colitis in Italy. A retrospective co-operative IG-IBD study. Dig Liver Dis 35(9):628–634. 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00380-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A (2022) Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clinicians 72(1):7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leersum NJ, Aalbers AG, Snijders HS, Henneman D, Wouters MW, Tollenaar RA et al (2014) Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: a risk factor in colorectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 57(4):460–466. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser MR, Gönen M, Chou JF, Kattan MW, Schrag D (2011) Predicting survival after curative colectomy for cancer: individualizing colon cancer staging. J Clin Oncol 29(36):4796–4802. 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A, He S, Li J, Liu L, Liu C, Wang Q, Peng X et al (2017) Colorectal cancer in cases of multiple primary cancers: clinical features of 59 cases and point mutation analyses. Oncol Lett 13(6):4720–4726. 10.3892/ol.2017.6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Peng JY, Chen W (2011) Synchronous colorectal cancers: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Dig Surg 28(5–6):379–385. 10.1159/000334073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JW, Lee SH, Ahn BK, Baek SU (2008) Clinical characteristics of multiple primary colorectal cancers. Cancer Res Treat 40(2):71–74. 10.4143/crt.2008.40.2.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database at http://www.seer.cancer.gov.