Abstract

The discussion on cell proliferation cannot be continued without taking a look at the cell cycle regulatory machinery. Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), cyclins, and CDK inhibitors (CKIs) are valuable members of this system and their equilibrium guarantees the proper progression of the cell cycle. As expected, any dysregulation in the expression or function of these components can provide a platform for excessive cell proliferation leading to tumorigenesis. The high frequency of CDK abnormalities in human cancers, together with their druggable structure has raised the possibility that perhaps designing a series of inhibitors targeting CDKs might be advantageous for restricting the survival of tumor cells; however, their application has faced a serious concern, since these groups of serine–threonine kinases possess non-canonical functions as well. In the present review, we aimed to take a look at the biology of CDKs and then magnify their contribution to tumorigenesis. Then, by arguing the bright and dark aspects of CDK inhibition in the treatment of human cancers, we intend to reach a consensus on the application of these inhibitors in clinical settings.

Keywords: Cyclin-dependent kinases, CDK, Cyclin, Cell cycle, Cancer, CDK inhibitors

Introduction

As a valuable asset of the cells, cell cycle regulation is managed by intact sensor mechanisms—called checkpoints—that intensely control the order of the events within each phase of the cell cycle (Hartwell and Weinert 1989). If any perturbation is detected in each stage, these checkpoints transmit a signal to a group of proteins named cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors to block the progression of the cell cycle (Musacchio and Salmon 2007; Williams and Stoeber 2012). CDKs—named due to the functional dependence on binding to cyclins (Cycs)—are a wide group of serine/threonine protein kinases that primarily regulate cell cycle (Canavese et al. 2012); however, these proteins might also play a fundamental role in the regulation of diverse biological processes, including cell metabolism, differentiation, hematopoiesis, and even stem cell renewal (Peyressatre et al. 2015; Hydbring et al. 2016; Lim and Kaldis 2013; Malumbres 2014). Other biological roles of CDKs are mostly mediated through the regulation of the transcription process; CDKs phosphorylate the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II), thereby regulating both the initiation and the elongation steps of the transcription process (Larochelle et al. 2012; Fisher 2005). Moreover, these kinases modulate the accumulation of short-lived transcription factors such as nuclear factor (NF)-κB and p53 within the cells, thus indirectly taking part in different biological events (Shapiro 2006).

By keeping these in mind, it is reasonable to argue that any disability in the function of CDKs can lead to uncontrolled cell cycle progression, which in turn by providing a condition for autonomous cell proliferation facilitates cancer development (Lin et al. 2018; Łukasik et al. 2021). Dysregulation in the expression of CDKs due to either genetic abnormalities or epigenetic alterations has been reported in more than 80% of human cancers (Peyressatre et al. 2015; Ortega et al. 2002). The aberrancy of CDKs in human cancers together with their druggable structure has raised the possibility that perhaps designing a series of inhibitors targeting these kinases might be advantageous in cancer therapeutics. But, it should be mentioned that the non-canonical function of CDKs might also be influenced by these interventions (Hydbring et al. 2016; Dai and Grant 2003); although this issue seems to be a dilemma for the application of CDK inhibitors in the treatment of human malignancies, it did not stop the development of novel CDK inhibitors: the more the discoveries about the biology of CDKs in cancer biology, the more will be the potential inhibitors designed for targeting these kinases (Asghar et al. 2015; Schwartz and Shah 2005; Malumbres and Barbacid 2001). In the present review, we aimed to take a look at the biology of CDKs in normal cells, and consider the contribution of these kinases to tumorigenesis under a magnifying glass.

An overview of the cell cycle

The cell cycle, which consists of four different phases, is a set of processes required to replicate one eukaryote cell into two identical daughter cells (Williams and Stoeber 2012). During interphase which itself has three steps, including gap phase-1 (G1), DNA synthesis (S), and gap phase-2 (G2), the cell prepares itself to enter the mitosis stage (M) in which the DNA content is copied and then cell division occurs (Lin et al. 2018). In the G1 phase, as the first stage of growth, cell size is increased, organelles are divided, and the molecular structures needed for subsequent growth are created. As the next step and in the S phase, not only does the cell synthesize a complete copy of DNA, but also reproduces a microtubule organization structure called the centrosome (Łukasik et al. 2021). In the G2 phase, as the last stage of interphase and the second stage of growth, the cell grows more and more, makes more proteins and organelles, and begins to reorganize its contents for mitosis (Schwartz and Shah 2005; Vermeulen et al. 2003). If cells fail to maintain their proliferation due to either lack of sufficient mitogenic stimuli or the presence of antimitogenic signals, they may exit G1 and enter the G0 (rest) stage—a phase in which cells undergo quiescence. Notably, the G0 stage is permanent for some cells, while others may re-enter the cell cycle if they receive appropriate signals and resume division (Vermeulen et al. 2003; Zetterberg and Larsson 1985).

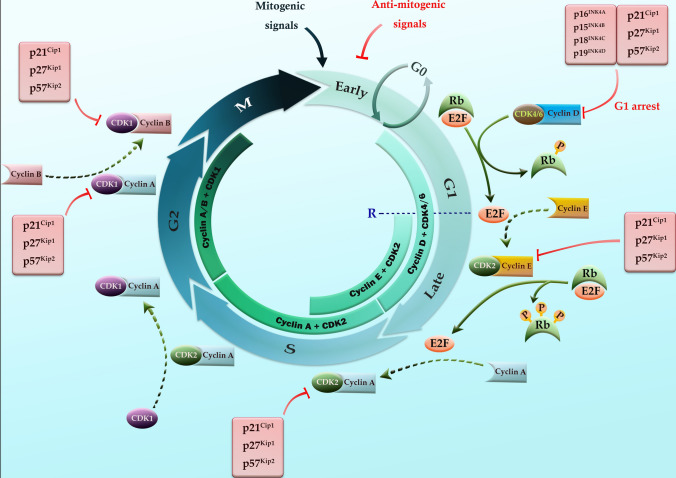

The transition of the cells in different stages is under intense surveillance by the sensor mechanisms called checkpoints, at which a group of serine/threonine kinases named CDKs plays fundamental roles (Lim and Kaldis 2013; Hunt et al. 2011). Checkpoints are indeed the corrector pens that prevent the incidence of the acquired mutations during DNA replication. If the genome defects, signals are sent to the effector proteins through the checkpoints, which in turn prevent cell cycle progression until the damage is resolved (Hartwell and Weinert 1989). Among the longitude list of effector proteins, CDK inhibitors (CDKIs) are important executioners which prevent a compromised cell from continuing to divide (Dai and Grant 2003). It is important to note that the lack of these regulatory mechanisms may lead to the accumulation of defects and genome instability, which subsequently may act in favor of neoplastic transformation (Gali-Muhtasib 2006; Zhang et al. 2021a). For better understanding, the detailed information on the stages of the mammalian cell cycle, as well as their regulation by CDKs, cyclins, and in vivo CDKIs are represented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the mammalian cell cycle stages, as well as cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and in vivo CDK inhibitors (CDKIs) involved in the regulation of these stages. The complex of cyclin D–CDK4/6 is implicated in the early G1 phase of the cell cycle where its task is to phosphorylate the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein in the Rb–E2F complex, consequently leading to the release of E2F that further begins the synthesis of cyclin E. After that, CDK2 connects to cyclin E in the late G1 phase and fulfills it by making cells independent of mitogenic signals (the letter R in the figure stands for the restriction point). Also, the complex of cyclin E–CDK2 is involved in G1–S transition by beginning the replication process of DNA, and CDK2 afterward combines with cyclin A for progression and completion of the S phase. The CDK1 binds to cyclin A and cyclin B for the transition from the S to G2 and G2 to M phases, respectively. In vivo CDK inhibitors (CDKIs) consist of the INK4 family (having four members of p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d) and the Cip/Kip family (having three members of p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2). While the members of the INK4 family predominantly target CDK4/6, the Cip/Kip family members are more promiscuous and extensively interfere with the functions of cyclin D-, E-, A-, B-dependent kinase complexes. G0: quiescence, G1: gap 1 (cell growth), S: DNA replication, G2: gap 2 (preparation for cell division), M: mitosis (cell division)

CDKs: the cornerstone of the cell cycle machinery

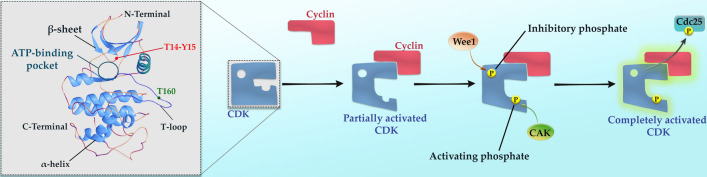

CDKs are relatively small proteins that belong to the family members of CMGC, in which several other proline-directed serine–threonine kinases, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), glycogen synthase kinases (GSKs), as well as CDK-like kinases (CLKs) are located (Peyressatre et al. 2015). According to genetic and biochemical retrospective studies, CDKs were first recognized independently in starfish, Xenopus, and yeast (Nurse 1975; Hartwell et al. 1974; Lee and Nurse 1987; Labbe et al. 1988, 1989; Lohka et al. 1988). They have similar two-lobed structures as other protein kinases, so that the major section of the monomeric structure contains α-helix in the C-terminal, while the N-terminal consists of β-sheets (Ortega et al. 2002). The adenosine triphosphate (ATP) cleft within the active site is located between these two sites. Of note, the activation loop or T-loop in the C-terminal lobe occupies a large and flexible area to create a barrier to prevent the entrance of protein substrate to the active site. It is worth mentioning that cyclin binding to CDK only results in partial activation, and phosphorylation of threonine residue nearby the kinase active site by CDK-activating kinase (CAK) is required to achieve full activation (Fig. 2). Upon complete activation of CDKs, their conformation structure changes in the way that it aligns Glu51 with Lys33 and Asp145 to open the catalytic groove that hydrolyzes ATP and transfer phosphate to the substrate (Malumbres 2014; Vivo et al. 2011).

Fig. 2.

Schematic depiction of the structure and activation process of CDKs. Generally, the binding of cyclin to a CDK causes the induction of a major conformational switch of the activation segment or T-loop of CDK, leading to rendering the substrate-binding cleft more accessible and exposing this loop to be phosphorylated by the CDK-activating kinase (CAK). CAK phosphorylates the T-loop at threonine160, which leads to the activation of CDK; however, subsequent phosphorylation at T14-Y15 can reduce the activity of CDK. Cdc25 family of phosphatases is responsible for dephosphorylating inhibitory phosphate residues, which leads to the complete activation of CDKs

Depending on which cyclins it binds to and their regulatory subunits, CDKs can regulate the transition of the cells from any stage of the cell cycle (Malumbres 2014). However, it should be noted that the biological functions of these kinases are not restricted only to the cell cycle, as these groups of regulatory proteins can also modulate the transcription process, messenger RNA (mRNA) processing, and cell differentiation (Łukasik et al. 2021). Based on sequencing, CDKs are categorized into “cell cycle-related CDKs” including CDK1, − 2, − 4, − 6, and “transcriptional CDKs” consisting of CDK7, -8,-9, -11, -12, -13, -19, and -20 (Wood and Endicott 2018; Malumbres and Barbacid 2009; Bose et al. 2013; Musgrove et al. 2011).

Cell cycle-related CDKs

Once cells exit from the G0 phase, the mitogenic signals activate CDK4 and CDK6 to bind to cyclin D (Malumbres and Barbacid 2009). The formed complex phosphorylates retinoblastoma (Rb) protein and partially releases the E2F transcription factor, leading to the transition of the cells from the G1 to S phase. E2F is the main player in this process as it enhances the transcription of cyclin E, a necessary protein of the S phase (Narasimha et al. 2014; Weintraub et al. 1995). When cyclin E binds to CDK2, it increases Rb phosphorylation and leads to the complete activation of E2F (Harbour et al. 1999). The degradation of cyclin E and the production of cyclin A, which in the absence of cyclin E binds to CDK2, transmit a signal for DNA replication (Petersen et al. 1999; Coverley et al. 2000). At the end of the S phase, the accumulated cyclin A activates CDK1 and allows cells to enter the G2 phase (Lin et al. 2018). Following the successful completion of G2, CDK1 makes a partnership with cyclin B to form a complex named maturation or M phase-promoting factor (MPF) that prepares the cells to undergo mitosis (Fig. 1). Based on these descriptions, CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 are classed as cell cycle-related CDKs (Lin et al. 2018; Łukasik et al. 2021; Schmitz and Kracht 2016; Kubiak and Dika 2011; Kishimoto 2015).

Transcriptional CDKs

The synthesis of RNA from DNA (i.e., transcription process) which is carried out by the RNA polymerase enzyme occurs in three steps, including initiation, elongation, and termination (Dannappel et al. 2018). Thus far, several CDKs have been identified to play fundamental roles in this process (Zhang et al. 2021a; Malumbres et al. 2009); for example, CDK7 in association with cyclin H and mating-type 1 (MAT1) protein makes up the complex called CDK-activating kinase (CAK) that is part of general transcriptional factor IIH (TF IIH). The catalytic subunit of this complex, i.e., CDK7, phosphorylates the CTD of RNA pol II which is essential for transcription (Shapiro 2006; Meinhart et al. 2005). Furthermore, CDK7 has essential roles in cell division through phosphorylation of several CDKs (Fisher 2005). Indeed, CAK activity has also been reported to be critical to promote CDK1 and CDK2 connecting to their corresponding cyclins, thus allowing cell division (Thoma et al. 2021). CDK20, also previously referred to as cell cycle-related kinase (CCRK), is the second CAK that shares the utmost sequence characteristics (43%) with CDK7 (Malumbres et al. 2009; Lai et al. 2020; Kaldis and Solomon 2000). Noteworthy, by activating CDK2 and cyclin D, CDK20 positively regulates the cell cycle (Lai et al. 2020; Tian et al. 2012).

Another transcriptional CDK is cell division protein kinase 8 (CDK8) that forms a complex with different proteins. The CDK8-like intracellular enzyme, CDK19 also known as CDK11 or death preventing kinase, belongs to the CMGC protein kinase superfamily. Both of these mediator kinases regulate transcription via RNA pol II phosphorylation (Wood and Endicott 2018). CDK9 is a positive transcription elongation factor b (p-TEFb) which in connection with its partner cyclin T or K can phosphorylate the C-terminal of RNA pol II, thereby performing as an essential regulator of transcription elongation (Łukasik et al. 2021; Lee and Zeidner 2019). Another less-known kinase associated with transcription is CDK13 which is different from other transcriptional CDKs except for CDK12, due to possessing an additional serine-arginine (SR)-rich region that is required for pre-mRNA splicing (Łukasik et al. 2021; Greifenberg et al. 2016). CDK13 has also been reported to play a role in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) mRNA splicing (Berro et al. 2008). To provide a well-conceptualized overview, Fig. 3 presents the involvement of transcriptional CDKs in different steps of the transcription process. Besides, we summarized the mammalian CDKs, their corresponding cyclin-activating partners, and biological functions in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

The regulation of the transcription process steps by CDK/cyclin complexes. The mediator complex, which consists of CDK8 or its paralog (CDK19), cyclin C, the mediator complex subunit 12 (Med12), and Med13 components, phosphorylates the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase (Pol) II to hinder its connecting to promoter DNA, thereby negatively regulating the transcription process. CDK8 or CDK19 also phosphorylates cyclin H to negatively regulate the activity of the TFIIH complex. The transcriptional CDKs 7 along with its partner, namely cyclin H/MAT1, phosphorylate the CTD of RNA Pol II at residues Ser-5, leading to facilitating the initiation of transcription. Noteworthy, CDK7/cyclin H as a CDK-activating kinase (CAK) phosphorylates and activates CDK9, which connects to the T-type cyclins (T1 and T2) as the subunit of the positive transcription elongation factor b (p-TEFb) to liberate the promoter from proximal arrest and provoke elongation step. Besides, the activated CDK9/cyclin T promotes the extension of the pre-mRNA transcript via the phosphorylation of negative elongation factor (NELF) and 5,6-dichloro-1-beta-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole sensitivity-inducing factor (DSIF) to liberate the stalling of the elongation complex. CDK12 and CDK13 with their cofactor cyclin K also phosphorylate the CTD at the Ser2 position, therefore allowing mRNA elongation. CDK11/cyclin L is implicated in the regulation of RNA splicing via phosphorylating factors related to pre-mRNA splicing, including SC35 and 9G8. Finally, sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein 1 (SCP1) promotes the termination of transcription through dephosphorylating Ser5 of CTD-RNA Pol II

Table 1.

The mammalian CDKs, their corresponding cyclin-activating partners, and biological functions

| CDK | Partner | Cell cycle function | Other functions | Reference (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle-related CDKs | ||||

| CDK1 |

Cyclin A Cyclin B |

G2 phase Mitosis |

DNA damage repair Epigenetic regulation Stem cell self-renewal |

Coudreuse and Nurse (2010), Jackman et al. (2003), Chen et al. (2009), Marais et al. (2010), Li et al. (2012), Ali et al. (2011), Chen et al. (2011), Huertas et al. (2008), Chen et al. (2010), Kaneko et al. (2010), Wei et al. (2011), Wu and Zhang (2011), Lavoie and St-Pierre (2011) and Goel et al. (2020) |

| CDK2 | Cyclin A | G1-S transition, S phase |

Stem cell self-renewal Epigenetic regulation |

Marais et al. (2010), Ali et al. (2011), Chen et al. (2010), Lavoie and St-Pierre (2011), Sherr and Roberts (2004) |

| CDK4 | Cyclin D | G1 phase, Rb/E2F transcription | Epigenetic regulation | Sherr and Roberts (2004), Ho and Dowdy (2002), Aggarwal et al. (2010) |

| CDK6 | Cyclin D | G1 phase, Rb/E2F transcription | Malumbres and Barbacid (2009) and Sherr and Roberts (2004) | |

| Transcriptional CDKs | ||||

| CDK7 | Cyclin H | CDK-activating kinase (CAK: CDK2 activator) | CAK for CDKs implicated in transcription | Fisher (2005), Lai et al. (2020), Goel et al. (2020) |

| CDK8 | Cyclin C | Regulator of multiple steps |

Lipogenesis inhibition Wnt/β-catenin signaling |

Szilagyi and Gustafsson (2013), Firestein et al. (2008), Akoulitchev et al. (2000) and Zhao et al. (2012) |

| CDK9 | Cyclin T, K | DNA damage repair (Cyclin K) | Wang and Fischer (2008) and Yu et al. (2010) | |

| CDK11 | Cyclin L | RNA splicing regulation | Hu et al. (2003) | |

| CDK12 | Cyclin K, L |

DNA damage repair (Cyclin K) Splicing regulation (Cyclin L) |

Chen et al. (2006), Bartkowiak et al. (2010), Blazek et al. (2011) and Cheng et al. (2012) | |

| CDK13 | Cyclin K, L | Splicing regulation (Cyclin L) | Chen et al. (2007) | |

| CDK19 | Cyclin C | García-Reyes et al. (2018) and Tsutsui et al. (2011) | ||

| CDK20 | Cyclin H | CAK (activates CDK2 and cyclin D) | Lai et al. (2020) | |

Cyclins: the oscillating proteins in the cell cycle

Basic research on the cell cycle of primitive eukaryotic model systems, sea urchins, enabled scientists to identify a diverse family of proteins named cyclins (Evans et al. 1983). Unlike cell cycle regulatory kinases, cyclins display dramatic changes in concentrations and are expressed periodically during each phase. In plain words, these putative regulatory subunits stay at low levels until the function of the target protein is required (Satyanarayana and Kaldis 2009). Accordingly, based on function and the timing of expression, cyclins are divided into four substantial classes (Malumbres and Barbacid 2009; Satyanarayana and Kaldis 2009).

G1 cyclins

Once a growth factor binds to its receptor or a mitogenic signal is transmitted, Rb protein became phosphorylated and disassociates from E2F (Harbour et al. 1999). The released E2F enhances the transcription of G1 cyclins including D-type cyclins (D1, D2, and D3); once their concentrations increase within the cells, they bind to CDK4 and CDK6 to trigger a cascade of transcriptional and post-transcriptional activities (Satyanarayana and Kaldis 2009). This complex also phosphorylates Rb in a compensative manner, aiding the excessive production of cyclin D and the progression of the cells from the G1 phase (Satyanarayana and Kaldis 2009; Sandal 2002).

G1/S cyclins

At the end of G1, cyclin E is expressed and makes a complex with CDK2 to release E2F from the phosphorylated Rb, an event that leads to G1/S transition (Satyanarayana and Kaldis 2009). The complex of cyclin E-CDK2 is also capable of phosphorylating G1/S specific proteins that are essential for DNA replication initiation and centrosome duplication. Moreover, as soon as the cell reaches an appropriate size and the cellular environment is accurate for DNA replication, the G1 cyclins allow cell cycle progression to the S phase by neutralizing the G1-related CDKs (Echalier et al. 2010; Deshpande et al. 2005; Murray 2004).

S cyclins

The beginning of the S phase is associated with an increase in cyclin A1 and A2—which their expression depends on the type of the cell (Satyanarayana and Kaldis 2009). In the S phase, the aforementioned cyclins with the help of their partner CDK2 are responsible for the synthesis of wholesale DNA. This step allows the cell to double genetic material before entering mitosis (Schwartz and Shah 2005; Malumbres and Barbacid 2005).

M cyclins

When S phase-related cyclins undergo ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, the expression of mitosis-related cyclins begins at the G2 phase (Kishimoto 2015). As mentioned above, cyclin B makes a team with CDK1 to form a complex named MPF during G2 (Chesnel et al. 2007). Cross talk between this complex and its target regulates the doubling of chromosomes and cell growth so that the cell contents distribute equally in the two daughter cells in cell division (Foster 2008).

Aberrant cell cycle and cancer

The association between the aberrancy in the regulation of the cell cycle components and the neoplastic formation has been reported in several studies, and currently cyclins and CDKs are under scrutinized evaluation for their role in tumorigenesis (Williams and Stoeber 2012; Zhang et al. 2021a; Deshpande et al. 2005). So far, several activating mutations have been recognized in the genes encoding CDKs as well as cyclins and a mounting body of evidence supports the correlation between these mutations and the development of several human cancers (Canavese et al. 2012; Peyressatre et al. 2015; Malumbres and Barbacid 2009).

Aberrant CDKs in tumorigenesis

The footprints of genetic abnormalities in genes encoding CDK4/CDK6 and Rb can be traced in more than half of human cancers (Ortega et al. 2002). For example, CDK6 amplification was observed in numerous types of malignancies, including leukemia, lymphomas, gliomas, head and neck, gastric, pancreatic squamous cell carcinoma, and medulloblastoma (Corcoran et al. 1999; Costello et al. 1997; Mendrzyk et al. 2005). On the other hand, a point mutation in the R24C codon of CDK4—leading to the replacement of Arg 24 to Cys or His—was frequently found in lung cancer, lymphomas, and melanoma, as well (Ortega et al. 2002; Sotillo et al. 2001, 2005; Chawla et al. 2010; Puyol et al. 2010; Vincent-Fabert et al. 2012). No matter how they are up-regulated, over-expressed CDK4/6 can affect mitogenic signals and lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation (Peyressatre et al. 2015).

A large number of researches have also suggested that CDK2 hyperactivation is particularly associated with hormone-dependent breast cancer, ovarian and endometrial carcinomas. Moreover, this abnormality was detected in highly aneuploidy cancers such as KRAS-mutant lung and thyroid carcinoma, as well as melanoma and osteosarcoma (Husdal et al. 2006; Ekberg et al. 2005; Nar et al. 2012; Wang et al. 1996; Furihata et al. 1996; Donnellan and Chetty 1999; Huuhtanen et al. 1999; Chao et al. 1998; Santala et al. 2014; Shaye et al. 2009; Nakayama et al. 2010; Karst et al. 2014; Lockwood et al. 2011; Koutsami et al. 2006; Yue and Jiang 2005). While CDK1 overexpression has been reported in advanced melanoma, lymphoma, lung cancer, ovarian carcinoma, liver, and colorectal cancers (Zhao et al. 2009; Abdullah et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2011), the evidence is controversial concerning CDK8 as its function might be different from cell to cell. While it can act as an oncogene through stimulating the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway in colon cancers (Firestein et al. 2008), CDK8 could serve as a tumor suppressor in cancers with activated Notch or EGFR signaling (Dannappel et al. 2018; Gu et al. 2013). Taken together, according to the type of cancer, each CDK might play a critical role in the maintenance of the proliferative capacity of the neoplastic cells, and thereby, guarantee their survival.

Aberrant cyclins in tumorigenesis

Deregulation of cyclin D1 affected by various mechanisms such as amplification, overexpression, rearrangement, and point mutation has been identified in the majority of human cancers (Akervall et al. 1997; Dobashi et al. 2004; Gillett et al. 1994). The best example of this dysregulation has been observed in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) where a chromosomal rearrangement placed heavy chain immunoglobulin (IGH) gene side by side to human cyclin D1 (CCND1) (Bertoni et al. 2006; Li et al. 1999). Apart from MCL, the presence of cyclin D1 overexpression or amplification has been reported in breast cancer, neuroblastoma, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma (Gansauge et al. 1997; Kim and Diehl 2009; Seong et al. 1999; Barbieri et al. 2004; Shan et al. 2017). Cyclin D1 mutations are also common in esophageal and endometrial cancers (Moreno-Bueno et al. 2004; Benzeno et al. 2006).

Another cyclin whose overexpression is common in different human cancers and is associated with tumor progression is cyclin E (Wang et al. 1996; Lockwood et al. 2011; Koutsami et al. 2006; Yue and Jiang 2005; Kitahara et al. 1995). The majority of the studies claimed that this is the truncated isoform of cyclin E that participates in the tumorigenesis. When this cyclin binds to CDK2, it aberrantly increases the activity of CDK2. However, as CDK2/cyclin E complex is resistant to CDK inhibitors and consequently even in the presence of stop signals, it forces the transition from the G1/S phase of the cell cycle. Breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma are those cancers at which truncated cyclin E was found (Keyomarsi et al. 1995; Porter and Keyomarsi 2000; Harwell et al. 2004; Akli and Keyomarsi 2004; Bedrosian et al. 2004; Bales et al. 2005). In addition to solid tumors, the overexpression of normal length cyclin E was reported in leukemias, lymphomas, and osteosarcoma, as well (Lockwood et al. 2011; Koutsami et al. 2006; Yue and Jiang 2005; Erlanson et al. 1998; Wołowiec et al. 1995).

Cyclin A is another cyclin whose overexpression has been reported to be associated with the induction of DNA lesions and the promotion of genome instability. Cyclin A overexpression has been described in metastatic tumors, including breast, colorectal, prostatic, esophageal, and oral cancers (Husdal et al. 2006; Ekberg et al. 2005; Nar et al. 2012; Wang et al. 1996; Furihata et al. 1996; Huuhtanen et al. 1999; Chao et al. 1998; Santala et al. 2014; Handa et al. 1999; Li et al. 2002). The excessive expression of cyclin B1 has been also reported in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and gastric cancer (Nar et al. 2012; Aaltonen et al. 2009; Begnami et al. 2010; Murakami et al. 1999; Soria et al. 2000). Overall, according to what was discussed above, it seems that aberrant expression of CDKs and cyclins is a common event in human cancers and perhaps harnessing these small proteins might be advantageous for cancer patients, irrespective of the type of malignancy. An overview of different aberrations of cyclins and CDKs in various cancers is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dysregulation in the expression of CDKs and their regulatory cyclin subunits in various cancers

| Alteration | Type of cancer | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclin A | ||

| Amplification | BC | Husdal et al. (2006) |

| Overexpression | CRC, EC, TC, HCC, Soft tissue sarcoma, AML, ESCC | Ekberg et al. (2005), Nar et al. (2012), Wang et al. (1996), Furihata et al. (1996), Huuhtanen et al. (1999), Chao et al. (1998), Santala et al. (2014) and Li et al. (2002) |

| Truncated form owing to the integration of HBV DNA | HCC | Chao et al. (1998) and Wang et al. (1990) |

| Cyclin B | ||

| Overexpression | BC, GC, ESCC, NSCLC, TC | Nar et al. (2012), Aaltonen et al. (2009), Begnami et al. (2010), Murakami et al. (1999) and Soria et al. (2000) |

| Overexpression/nuclear localization | BC | Suzuki et al. (2007) |

| Cyclin D | ||

| Amplification/overexpression | HNSCC | Akervall et al. (1997), Meredith et al. (1995) and Michalides et al. (1997) |

| Overexpression | EC, LC, PaC, Follicular MCL, BC, HNSCC, ESCC, CRC, OC, GC | Dobashi et al. (2004), Gansauge et al. (1997), Kim and Diehl (2009), Seong et al. (1999), Barbieri et al. (2004), Shan et al. (2017), Moreno-Bueno et al. (2004) |

| IgH translocation and overexpression | MCL, MM | Bertoni et al. (2006), Li et al. (1999), Bergsagel and Kuehl (2005) and Chesi et al. (1996) |

| Truncated form (cyclin D1b) (A870G polymorphism) | PC, BC, NSCLC, ESCC, PC | Comstock et al. (2009), Millar et al. (2009), Gautschi et al. (2007), Betticher et al. (1995), Li et al. (2008), Knudsen et al. (2006) and Burd et al. (2006) |

| Truncated cyclin D1b and co-expression with cyclin D1a | BC | Abramson et al. (2010) |

| Cyclin D1a isoformsa | MCL | Wiestner et al. (2007) |

| Mutation disrupting phosphorylation-dependent nuclear export | ESCC | Benzeno et al. (2006) |

| Cyclin E | ||

| Amplification | OC | Nakayama et al. (2010) and Karst et al. (2014) |

| Overexpression/amplification | CRC, BC | Wang et al. (1996), Kitahara et al. (1995) and Scaltriti et al. (2011) |

| Overexpression | Osteosarcoma, NSCLC, PaC, BC, CRC, Acute and chronic leukemias, HL, NHL, IBC | Lockwood et al. (2011), Koutsami et al. (2006), Yue and Jiang (2005), Erlanson et al. (1998), Wołowiec et al. (1995), Lindahl et al. (2004), Zhou et al. (2011), Alexander et al. (2017) |

| Overexpression/high nuclear expression | Early development of BC | Shaye et al. (2009) |

| Overexpression of small isoforms | BC | Keyomarsi et al. (1995), Porter and Keyomarsi (2000), Weroha et al. (2010) and Wingate et al. (2009) |

| LMV isoform (truncated) | BC, OC, melanoma | Harwell et al. (2004), Akli and Keyomarsi (2004), Bedrosian et al. (2004) and Bales et al. (2005) |

| CDK1 | ||

| Overexpression | Advanced melanoma, B cell lymphoma, CRC, ESCC | Zhao et al. (2009), Abdullah et al. (2011), Li et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2021b) |

| CDK2 | ||

| Overexpression | Oral cancer, advanced melanoma, BC, LSCC | Wang et al. (1996), Abdullah et al. (2011), Weroha et al. (2010), Mihara et al. (2001) and Georgieva et al. (2001) |

| CDK3 | ||

| Overexpression | Glioblastoma | Zheng et al. (2008) |

| Highly expressed | Non-malignant BC | Cao et al. 2017) |

| CDK4 | ||

| Amplification | Glioblastoma, refractory rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma | Park et al. (2014), Wei et al. (1999) and Schmidt et al. (1994) |

| Amplification/overexpression | Sporadic BC, uterine cervix cancer, osteosarcoma | Wei et al. (1999), Wunder et al. (1999) and Cheung et al. (2001) |

| Overexpression | LC, melanomas | Dobashi et al. (2004), Wu et al. (2011) and Smalley et al. (2008) |

| R24C mutation | MCL, LC, familial melanoma | Sotillo et al. (2001), Sotillo et al. (2005), Chawla et al. (2010), Puyol et al. (2010), Vincent-Fabert et al. (2012), Zuo et al. (1996), Wölfel et al. (1995), Vidwans et al. (2011), Tsao et al. (2012) and Sheppard and McArthur (2013) |

| CDK5 | ||

| Amplification/overexpression | PaC | Eggers et al. (2011) |

| Overexpression | PC | Strock et al. (2006) |

| BC | Liang et al. (2013) | |

| mRNA up-regulation | BC, CRC, HNSCC, OC, LC, lymphoma, PC, MM, sarcoma, bladder cancer | Levacque et al. (2012) |

| SNPs in the promoter region | Enhanced risk of LC | Choi et al. (2009) |

| Reduced methylation of promoter leading to overexpression | MCL | Leshchenko et al. (2010) |

| CDK6 | ||

| Amplification | SCC, glioma, lymphoma | Costello et al. (1997) and Chilosi et al. (1998) |

| BC | Yang et al. (2017) | |

| Overexpression | Medulloblastoma | Mendrzyk et al. (2005) |

| Highly expressed | NSCLC | Gong et al. (2020) |

| Sumoylation | Glioblastoma | Bellail et al. (2014) |

| Translocation | Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | Corcoran et al. (1999) |

| D32Y mutation | Neuroblastoma | Easton et al. (1998) |

| CDK7 | ||

| Overexpression | HCC, OSCC, osteosarcoma | Liu et al. (2018), Jiang et al. (2019) and Ma et al. (2021) |

| CDK8 | ||

| Amplification | BC | Broude et al. (2015) |

| Amplification and overexpression | CRC | Firestein et al. (2008), Firestein et al. (2010) and Seo et al. (2010) |

| Overexpression | Colon cancer, GC | Adler et al. (2012) and Kim et al. (2011) |

| Tumor-suppressive function | EC | Gu et al. (2013) |

| siRNA-mediated silencing inhibits proliferation | BC | Li et al. (2014) |

| Up-regulation upon loss of macroH2A histone variant | Melanoma | Kapoor et al. (2010) |

| CDK8 expression and the delocalization of β-catenin expressionb | GC | Kim et al. (2011) |

| CDK9 | ||

| Overexpression | PaC, EC | Kretz et al. (2017) and He et al. (2020) |

| Highly expressed | CLL, MM | Tong et al. (2010) |

| High expression predicts poor prognosis | Osteosarcoma | Ma et al. (2019) |

| Differential expression correlating with malignant transformation | Lymphoma | Bellan et al. (2004) |

| Expression correlates with differentiation grade | Primary neuroectodermal tumors and neuroblastoma | Falco et al. (2005) |

| CDK10 | ||

| Down-regulation | HCC, biliary tract cancer, GC | Zhong et al. (2012), Yu et al. (2012) and You et al. (2018) |

| Low expression | GC | Zhao et al. (2017) |

| CDK11 | ||

| Overexpression | Osteosarcoma | Duan et al. (2012) |

| Gene deletion/translocation | Neuroblastoma | Lahti et al. (1994) |

| Loss of one allele of Cdc2L/decreased CDK11 expression | Melanoma | Chandramouli et al. (2007) |

| CDK12 | ||

| Overexpression | BC, cervical cancer | Paculová and Kohoutek (2017), Yang et al. (2021a) |

| CDK13 | ||

| Up-regulation | PC | Qi et al. (2021) |

| CDK14 | ||

| Overexpression | ESSC, HCC, NSCLC | Miyagaki et al. (2012), Leung et al. (2011) and Yang et al. (2021b) |

| Highly expressed | CRC | Mao et al. (2017) |

| CDK15 | ||

| Highly expressed | CRC | Huang et al. (2022) |

| Up-regulation | BC | Zhang et al. (2021c) |

| CDK16 | ||

| Overexpression | NSCLC, CSCC | Wang et al. (2018) and Yanagi et al. (2017) |

| CDK19 | ||

| Amplification | BC | Broude et al. (2015) |

| Overexpression | Advanced PC | Brägelmann et al. (2017) |

| Up-regulation | HCC | Cai et al. (2021) |

| CDK20 | ||

| Overexpression | LC | Wang et al. (2017) |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; CRC, colorectal cancer; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TC, thyroid carcinoma; BC, breast cancer; IBC, inflammatory breast cancer; GC, gastric cancer; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; LC, lung cancer; PaC, pancreatic carcinoma; OC, ovarian carcinoma; CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; PC, prostate cancer; EC, endometrial cancer; HL, Hodgkin's lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; LSCC, laryngeal squamous cell cancer; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain; UTRs, untranslated regions; LMV, low molecular weight; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms

aHaving truncated 3′ UTRs, not alternatively spliced cyclin D1b mRNA isoforms/changes of the 3′ UTR structure of the cyclin D1 gene (CCND1)

bPositively correlate with carcinogenesis and tumor progression

CDK/cyclin inhibitors

Over the past decades, with the identification of CDK/cyclin impact in cancer progression, interest in recognizing inhibitors of these regulatory proteins has been increased (Dai and Grant 2003; Zhang et al. 2021a). CDK inhibitors (CKI) are lightweight chemical molecules that by interaction with their substrate can block the cell cycle stages. For the first time, CKIs were obtained from natural sources such as plants, bacteria, fungi, and sponges; however, the synthetic forms of these inhibitors were also developed very soon (Peyressatre et al. 2015; Gali-Muhtasib 2006).

Natural (in vivo) CKIs

Based on the structure and type of cyclins that react with, natural CDK inhibitors are categorized into two main classes, including the INK4 family and the CIP/KIP family (Asghar et al. 2015; Ding et al. 2020).

INK4 family

INK4 family also called inhibitors of CDK4/6 are polypeptides with 15–19 kilo Daltons weight and consist of several subtypes such as INK4a (p16) and INK4b (p15); INK4c (p18) and INK4d (p19) are two additional associates of the INK4 family that share multiple ankyrin repeats (Sherr and Roberts 1999). While p15 and p16 are encoded by the 9p21 chromosome, p18 and p19 are located on 1p32 and 19p13, respectively. The members of this family of CKIs are approximately 40% homologs and can inhibit cyclin D, an event that leads to G1 cell cycle arrest (Fig. 1) (Malumbres and Barbacid 2001; Sherr and Roberts 1999; Roussel 1999; Cánepa et al. 2007).

CIP/KIP family

The second category of CKIs, CDK-interacting protein/kinase inhibitor proteins (CIP/KIP), controls the cell cycle at the broader level (Sherr and Roberts 1999). This family has several well-known members such as p27 (Kip1), p57 (Kip2), as well as p21 (Cip1), also called Waf1, Sdi1, and CAP20. The members of this family bind to CDKs through their N-terminal CDK binding/inhibitory domain. CIP/KIP inhibitors not only interact with cyclin E and A, but also are essential for stabilizing the CDK4/6-cyclin D complex (Fig. 1) (Denicourt and Dowdy 2004; Jung et al. 2010). Apart from cell cycle regulation, several latest papers implied that CIP/KIP inhibitors might have other biological functions; for instance, p21 other than its role in proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-mediated DNA damage repair, could regulate cell differentiation, transcription, apoptosis, and cellular senescence (Sherr and Roberts 1999; Denicourt and Dowdy 2004; Jung et al. 2010). Moreover, CKIs 1B (p27kip1) and 1C (p57kip2) parallel to p21 are tumor suppressors which can prevent Rb phosphorylation and halt DNA synthesis by suppressing the activity of cyclin E/A-CDK2 complexes (Lai et al. 2020; Creff and Besson 2020).

Synthetic (in vitro) CKIs

Many pharmacologic inhibitors of CDKs belonging to different chemical classes have been developed over recent years, some of which have been tested in clinical trials (Lin et al. 2018; Schwartz and Shah 2005; Zhang et al. 2021a). In the first generation of CDK inhibitors (also known as pan-CDK inhibitors), alvocidib (flavopiridol) is the first in class that reached clinical trials. This synthetic CDK inhibitor, which was first extracted from an Indian plant, is a pan-CDK inhibitor with the ability to inhibit several CDKs, including CDKs 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9 (Asghar et al. 2015; Gali-Muhtasib 2006; Zhang et al. 2021a). Although numerous studies have implied the potent anti-tumor activity of this agent, the unfavorable toxicity and the lack of specificity for monopolized CDK muted the enthusiasm into the clinical application of alvocidib (Wiernik 2016; Blachly and Byrd 2013). Among second-generation CKIs, AT7519 is a novel pan-CDK inhibitor that inhibits CDKs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 9 in an ATP-competitive manner (Goel et al. 2020; Seftel et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2021). In a previous study, it has been reported that CDK inhibition using AT7519 decreased survival of a panel of leukemia-derived cell lines irrespective of p53 status; proposing that this agent may probably be effective both in mutant and wild-type p53-harboring leukemic cells (Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi et al. 2020). Inline, AT7519 not only suppressed acute myeloid leukemia cell survival through the inhibition of autophagy, but also intensified the anti-leukemic effect of arsenic trioxide (Zabihi et al. 2019). An overview of the first- and second-generation CKIs used in clinical trials is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

An overview of the first- and second-generation CDK inhibitors (CKIs) used in clinical trials

| Other names | Class | Major CDK targets | Phase | Identifier | Injection mode | Indications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation inhibitors | |||||||

| Flavopiridol | Alvocidib, L868275, HMR-1275 | Flavonoid | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9 | Phase II | NCT03604783 | Oral/I.V | AML, ALL, CLL, MM, lymphoma, MCL |

| UCN-01 | 7-hydroxystaurosporine | Alkaloid | 1, 2, 4 | Phase I | NCT00019838 | I.V | Refractory lymphoma or leukemia |

| R-roscovitine | Seliciclib, CYC202, roscovitine | Trisubstituted purine | 1, 2, 5, 7, 9 | Phase II | NCT03774446 | Oral | NSCLC, Crohn’s disease, Niemann Pick disease type C, metastatic breast cancer, advanced solid tumors |

| Second-generation inhibitors | |||||||

| AT7519 | AT-7519, AT 7519, AT7519M | Pyrazole | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9 | Phase II | NCT02503709 | I.V | CLL, MCL, MM, NHL, solid tumors |

| PD-0332991 | Palbociclib | Pyridopyrimidine | 4, 6 | Phase I/ II | Oral/I.V | Hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer, advanced gastrointestinal tumors, advanced solid tumors, metastatic melanoma, advanced NSCLC, MM, lymphoma | |

| SNS-032 | SNS032, BMS-387032 | Thiazole | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9 | Phase I | NCT00446342 | I.V | B-lymphoid malignancies, CLL, solid tumors, advanced breast cancer, melanoma/NSCLC |

| TG02 | TG-02, SB1317, SB-1317, Zotiraciclib | Pyrimidine | 1, 2, 5, 7, 9 | Phase II | NCT03904628 | Oral | Glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, CLL, hematological neoplasm |

| Dinaciclib | SCH-727965, SCH 727965, MK-7965, MK 7965 | Pyrimidine | 1, 2, 5, 9 | Phase III | NCT01580228 | I.V | CLL, MCL, NSCLC, melanoma, breast cancer |

| Roniciclib | BAY1000394, BAY-1000394 | Pyrimidine | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9 | Phase II | NCT02161419 | Oral | SCLC |

| P276-00 | Riviciclib hydrochloride, P276 | Flavone | 1, 4, 9 | Phase II | NCT00899054 | I.V | Breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, neoplasms |

| RGB-286638 | RGB286638 | Indenopyrazole | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9 | Phase I | NCT01168882 | I.V | Hematological malignancies |

| R-547 | Ro 4584820 | Diaminopyrimidine | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9 | Phase I | NCT00400296 | I.V | Neoplasms |

| AZD5438 | AZD-5438; AZD 5438 | Pyrimidine | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 | Phase I | NCT00088790 | Oral | Neoplasms |

| ZK304709 | MTGI, ZK-CDK, ZK-304709, ZK 304709 | Aminopyrimidine | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9 | Phase I | ND | Oral | Advanced solid tumors |

| PHA-848125AC | PHA848125AC, PHA 848125AC, Milciclib Maleate | Pyrazole | 1, 2, 4, 5 | Phase I | NCT01300468 | Oral | Solid tumors |

| PHA793887 | PHA-793887, PHA 793887 | Pyrazole | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 | Phase I | NCT00996255 | I.V | Advanced/metastatic solid tumors |

| Indirubin | Isoindigotin; Indigopurpurin | Indolinone | 1, 2, 4, 5 | Phase IV | NCT02200978 | Oral | Childhood acute promyelocytic leukemia |

| CYC-065 | CYC065, CYC 065, Fadraciclib | Aminopurine | 2, 9 | Phase I | NCT02552953 | Oral | MDS, AML, advanced cancer, relapsed/refractory CLL |

| AG-024322 | AG024322 | Imidazole | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9 | Phase I | NCT00147485 | I.V | NHL, neoplasms |

| Voruciclib | P1446A-05 | Flavonoid | 4, 6, 9 | Phase I | NCT03547115 | Oral | AML, CLL, melanoma |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MM, multiple myelomal MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; MTGI, multi-targeted growth inhibitor; ND, not determined

Conclusion and future perspective

As the number of studies supporting the fundamental roles of CDKs in tumorigenesis increases, enthusiasm for the development of novel CDK inhibitors has grown intensively. So far, several CDK inhibitors have entered clinical trials and successful application of CDK4/6 inhibitors (ribociclib, palbociclib, and abemaciclib) in the treatment of breast cancer has energized the field to develop more potent inhibitors (Lin et al. 2018; Ding et al. 2020). Unlike the success of pan-CDK inhibitors, the mono-specific CDK inhibitors did not experience many victories. The best example could be described in mono-specific inhibitors against CDK5; indeed, the similarity between the structure of CDK2 and CDK5 causes undesirable suppression of the former using CDK5 inhibitors. Since each CDK might have other biological functions in addition to regulating the cell cycle, undesired interventions may lead to serious side effects. Now, a question arises; “Is it the end for CDK inhibitors?”

The latest advances in drug discovery of kinase inhibitors have made it possible to design novel mono-specific CDK inhibitors, this time by targeting other regions rather than the ATP active-binding sites. Inhibitors could be designed to interact with the allosteric region, target the inactive conformation, create the covalent ligand, and interfere with the binding of substrate. It is postulated that these classes of inhibitors might have lower toxic effects, better pharmacokinetic properties, and higher anti-cancer activities. Taking advantage of these, CDK inhibitors might have a long way to receive approval for the treatment of human cancers, but their development can shed a ray of hope for cancer patients, especially those who suffer from aberrant expression of CDKs/cyclins.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Tehran, Iran) for supporting this study.

Abbreviations

- CAK

CDK-activating kinase

- CCRK

Cell cycle-related kinase

- CDKIs

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors

- CDKs

Cyclin-dependent kinases

- CIP/KIP

CDK-interacting protein/kinase inhibitor protein

- CTD

Carboxy terminal domain

- INK4

Inhibitors of CDK4/6

- MAT1

Mating-type 1

- MPF

Maturation or M phase-promoting factor

- PCNA

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- p-TEFb

Positive transcription elongation factor b

- Rb

Retinoblastoma

- RNA Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- TFIIH

Transcription factor IIH

Author contributions

Mitra Zabihi: Investigation, writing the main manuscript text. Ramin Lotfi: prepared Tables, Writing-original draft. Amir-Mohammad Yousefi: Investigation, prepared figures.Davood Bashash: Conceptualization, Data validation, Supervision, Writing-review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript."

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the present study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aaltonen K, Amini RM, Heikkilä P, Aittomäki K, Tamminen A, Nevanlinna H et al (2009) High cyclin B1 expression is associated with poor survival in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 100(7):1055–1060. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah C, Wang X, Becker D (2011) Expression analysis and molecular targeting of cyclin-dependent kinases in advanced melanoma. Cell Cycle 10(6):977–988. 10.4161/cc.10.6.15079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson VG, Troxel AB, Feldman M, Mies C, Wang Y, Sherman L et al (2010) Cyclin D1b in human breast carcinoma and coexpression with cyclin D1a is associated with poor outcome. Anticancer Res 30(4):1279–1285 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler AS, McCleland ML, Truong T, Lau S, Modrusan Z, Soukup TM et al (2012) CDK8 maintains tumor dedifferentiation and embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Cancer Res 72(8):2129–2139. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-11-3886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal P, Vaites LP, Kim JK, Mellert H, Gurung B, Nakagawa H et al (2010) Nuclear cyclin D1/CDK4 kinase regulates CUL4 expression and triggers neoplastic growth via activation of the PRMT5 methyltransferase. Cancer Cell 18(4):329–340. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akervall JA, Michalides RJ, Mineta H, Balm A, Borg A, Dictor MR et al (1997) Amplification of cyclin D1 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and the prognostic value of chromosomal abnormalities and cyclin D1 overexpression. Cancer 79(2):380–389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akli S, Keyomarsi K (2004) Low-molecular-weight cyclin E: the missing link between biology and clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res 6(5):188–191. 10.1186/bcr905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akoulitchev S, Chuikov S, Reinberg D (2000) TFIIH is negatively regulated by cdk8-containing mediator complexes. Nature 407(6800):102–106. 10.1038/35024111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F, Hindley C, McDowell G, Deibler R, Jones A, Kirschner M et al (2011) Cell cycle-regulated multi-site phosphorylation of Neurogenin 2 coordinates cell cycling with differentiation during neurogenesis. Development 138(19):4267–4277. 10.1242/dev.067900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar U, Witkiewicz AK, Turner NC, Knudsen ES (2015) The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14(2):130–146. 10.1038/nrd4504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales E, Mills L, Milam N, McGahren-Murray M, Bandyopadhyay D, Chen D et al (2005) The low molecular weight cyclin E isoforms augment angiogenesis and metastasis of human melanoma cells in vivo. Cancer Res 65(3):692–697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri F, Lorenzi P, Ragni N, Schettini G, Bruzzo C, Pedullà F et al (2004) Overexpression of cyclin D1 is associated with poor survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncology 66(4):310–315. 10.1159/000078332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak B, Liu P, Phatnani HP, Fuda NJ, Cooper JJ, Price DH et al (2010) CDK12 is a transcription elongation-associated CTD kinase, the metazoan ortholog of yeast Ctk1. Genes Dev 24(20):2303–2316. 10.1101/gad.1968210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedrosian I, Lu KH, Verschraegen C, Keyomarsi K (2004) Cyclin E deregulation alters the biologic properties of ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene 23(15):2648–2657. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begnami MD, Fregnani JH, Nonogaki S, Soares FA (2010) Evaluation of cell cycle protein expression in gastric cancer: cyclin B1 expression and its prognostic implication. Hum Pathol 41(8):1120–1127. 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellail AC, Olson JJ, Hao C (2014) SUMO1 modification stabilizes CDK6 protein and drives the cell cycle and glioblastoma progression. Nat Commun 5:4234. 10.1038/ncomms5234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellan C, De Falco G, Lazzi S, Micheli P, Vicidomini S, Schürfeld K et al (2004) CDK9/CYCLIN T1 expression during normal lymphoid differentiation and malignant transformation. J Pathol 203(4):946–952. 10.1002/path.1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzeno S, Lu F, Guo M, Barbash O, Zhang F, Herman JG et al (2006) Identification of mutations that disrupt phosphorylation-dependent nuclear export of cyclin D1. Oncogene 25(47):6291–6303. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM (2005) Molecular pathogenesis and a consequent classification of multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 23(26):6333–6338. 10.1200/jco.2005.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berro R, Pedati C, Kehn-Hall K, Wu W, Klase Z, Even Y et al (2008) CDK13, a new potential human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitory factor regulating viral mRNA splicing. J Virol 82(14):7155–7166. 10.1128/jvi.02543-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni F, Rinaldi A, Zucca E, Cavalli F (2006) Update on the molecular biology of mantle cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol 24(1):22–27. 10.1002/hon.767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betticher DC, Thatcher N, Altermatt HJ, Hoban P, Ryder WD, Heighway J (1995) Alternate splicing produces a novel cyclin D1 transcript. Oncogene 11(5):1005–1011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blachly JS, Byrd JC (2013) Emerging drug profile: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Leuk Lymphoma 54(10):2133–2143. 10.3109/10428194.2013.783911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazek D, Kohoutek J, Bartholomeeusen K, Johansen E, Hulinkova P, Luo Z et al (2011) The Cyclin K/Cdk12 complex maintains genomic stability via regulation of expression of DNA damage response genes. Genes Dev 25(20):2158–2172. 10.1101/gad.16962311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose P, Simmons GL, Grant S (2013) Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor therapy for hematologic malignancies. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 22(6):723–738. 10.1517/13543784.2013.789859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brägelmann J, Klümper N, Offermann A, von Mässenhausen A, Böhm D, Deng M et al (2017) Pan-cancer analysis of the mediator complex transcriptome identifies CDK19 and CDK8 as therapeutic targets in advanced prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 23(7):1829–1840. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-16-0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broude EV, Győrffy B, Chumanevich AA, Chen M, McDermott MS, Shtutman M et al (2015) Expression of CDK8 and CDK8-interacting genes as potential biomarkers in breast cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 15(8):739–749. 10.2174/156800961508151001105814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd CJ, Petre CE, Morey LM, Wang Y, Revelo MP, Haiman CA et al (2006) Cyclin D1b variant influences prostate cancer growth through aberrant androgen receptor regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(7):2190–2195. 10.1073/pnas.0506281103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Deng J, Zhou J, Cai H, Chen Z (2021) Cyclin-dependent kinase 19 upregulation correlates with an unfavorable prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol 21(1):377. 10.1186/s12876-021-01962-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavese M, Santo L, Raje N (2012) Cyclin dependent kinases in cancer: potential for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Biol Ther 13(7):451–457. 10.4161/cbt.19589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cánepa ET, Scassa ME, Ceruti JM, Marazita MC, Carcagno AL, Sirkin PF et al (2007) INK4 proteins, a family of mammalian CDK inhibitors with novel biological functions. IUBMB Life 59(7):419–426. 10.1080/15216540701488358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli A, Shi J, Feng Y, Holubec H, Shanas RM, Bhattacharyya AK et al (2007) Haploinsufficiency of the cdc2l gene contributes to skin cancer development in mice. Carcinogenesis 28(9):2028–2035. 10.1093/carcin/bgm066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Y, Shih YL, Chiu JH, Chau GY, Lui WY, Yang WK et al (1998) Overexpression of cyclin A but not Skp 2 correlates with the tumor relapse of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 58(5):985–990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla R, Procknow JA, Tantravahi RV, Khurana JS, Litvin J, Reddy EP (2010) Cooperativity of Cdk4R24C and Ras in melanoma development. Cell Cycle 9(16):3305–3314. 10.4161/cc.9.16.12632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Wang YC, Fann MJ (2006) Identification and characterization of the CDK12/cyclin L1 complex involved in alternative splicing regulation. Mol Cell Biol 26(7):2736–2745. 10.1128/mcb.26.7.2736-2745.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Wong YH, Geneviere AM, Fann MJ (2007) CDK13/CDC2L5 interacts with L-type cyclins and regulates alternative splicing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354(3):735–740. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YJ, Dominguez-Brauer C, Wang Z, Asara JM, Costa RH, Tyner AL et al (2009) A conserved phosphorylation site within the forkhead domain of FoxM1B is required for its activation by cyclin-CDK1. J Biol Chem 284(44):30695–30707. 10.1074/jbc.M109.007997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Bohrer LR, Rai AN, Pan Y, Gan L, Zhou X et al (2010) Cyclin-dependent kinases regulate epigenetic gene silencing through phosphorylation of EZH2. Nat Cell Biol 12(11):1108–1114. 10.1038/ncb2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, Lu LX, Ohi MD, Creamer KM, English C, Partridge JF et al (2011) Cdk1 phosphorylation of the kinetochore protein Nsk1 prevents error-prone chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol 195(4):583–593. 10.1083/jcb.201105074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SW, Kuzyk MA, Moradian A, Ichu TA, Chang VC, Tien JF et al (2012) Interaction of cyclin-dependent kinase 12/CrkRS with cyclin K1 is required for the phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol 32(22):4691–4704. 10.1128/mcb.06267-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesi M, Bergsagel PL, Brents LA, Smith CM, Gerhard DS, Kuehl WM (1996) Dysregulation of cyclin D1 by translocation into an IgH gamma switch region in two multiple myeloma cell lines. Blood 88(2):674–681 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnel F, Bazile F, Pascal A, Kubiak JZ (2007) Cyclin B2/cyclin-dependent kinase1 dissociation precedes CDK1 Thr-161 dephosphorylation upon M-phase promoting factor inactivation in Xenopus laevis cell-free extract. Int J Dev Biol 51(4):297–305. 10.1387/ijdb.072292fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung TH, Yu MM, Lo KW, Yim SF, Chung TK, Wong YF (2001) Alteration of cyclin D1 and CDK4 gene in carcinoma of uterine cervix. Cancer Lett 166(2):199–206. 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00457-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilosi M, Doglioni C, Yan Z, Lestani M, Menestrina F, Sorio C et al (1998) Differential expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 in cortical thymocytes and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia. Am J Pathol 152(1):209–217 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HS, Lee Y, Park KH, Sung JS, Lee JE, Shin ES et al (2009) Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter of the CDK5 gene and lung cancer risk in a Korean population. J Hum Genet 54(5):298–303. 10.1038/jhg.2009.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock CE, Augello MA, Benito RP, Karch J, Tran TH, Utama FE et al (2009) Cyclin D1 splice variants: polymorphism, risk, and isoform-specific regulation in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15(17):5338–5349. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-08-2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran MM, Mould SJ, Orchard JA, Ibbotson RE, Chapman RM, Boright AP et al (1999) Dysregulation of cyclin dependent kinase 6 expression in splenic marginal zone lymphoma through chromosome 7q translocations. Oncogene 18(46):6271–6277. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello JF, Plass C, Arap W, Chapman VM, Held WA, Berger MS et al (1997) Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) amplification in human gliomas identified using two-dimensional separation of genomic DNA. Cancer Res 57(7):1250–1254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudreuse D, Nurse P (2010) Driving the cell cycle with a minimal CDK control network. Nature 468(7327):1074–1079. 10.1038/nature09543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverley D, Pelizon C, Trewick S, Laskey RA (2000) Chromatin-bound Cdc6 persists in S and G2 phases in human cells, while soluble Cdc6 is destroyed in a cyclin A-cdk2 dependent process. J Cell Sci 113(Pt 11):1929–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creff J, Besson A (2020) Functional versatility of the CDK inhibitor p57(Kip2). Front Cell Dev Biol 8:584590. 10.3389/fcell.2020.584590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Grant S (2003) Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol 3(4):362–370. 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00079-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannappel MV, Sooraj D, Loh JJ, Firestein R (2018) Molecular and in vivo Functions of the CDK8 and CDK19 Kinase Modules. Front Cell Dev Biol 6:171. 10.3389/fcell.2018.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco G, Bellan C, D’Amuri A, Angeloni G, Leucci E, Giordano A et al (2005) Cdk9 regulates neural differentiation and its expression correlates with the differentiation grade of neuroblastoma and PNET tumors. Cancer Biol Ther 4(3):277–281. 10.4161/cbt.4.3.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vivo M, Bottegoni G, Berteotti A, Recanatini M, Gervasio FL, Cavalli A (2011) Cyclin-dependent kinases: bridging their structure and function through computations. Future Med Chem 3(12):1551–1559. 10.4155/fmc.11.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denicourt C, Dowdy SF (2004) Cip/Kip proteins: more than just CDKs inhibitors. Genes Dev 18(8):851–855. 10.1101/gad.1205304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Sicinski P, Hinds PW (2005) Cyclins and cdks in development and cancer: a perspective. Oncogene 24(17):2909–2915. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Cao J, Lin W, Chen H, Xiong X, Ao H et al (2020) The roles of cyclin-dependent kinases in cell-cycle progression and therapeutic strategies in human breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci 21(6):1960. 10.3390/ijms21061960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi Y, Goto A, Fukayama M, Abe A, Ooi A (2004) Overexpression of cdk4/cyclin D1, a possible mediator of apoptosis and an indicator of prognosis in human primary lung carcinoma. Int J Cancer 110(4):532–541. 10.1002/ijc.20167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan R, Chetty R (1999) Cyclin E in human cancers. Faseb j 13(8):773–780. 10.1096/fasebj.13.8.773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Zhang J, Choy E, Harmon D, Liu X, Nielsen P et al (2012) Systematic kinome shRNA screening identifies CDK11 (PITSLRE) kinase expression is critical for osteosarcoma cell growth and proliferation. Clin Cancer Res 18(17):4580–4588. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton J, Wei T, Lahti JM, Kidd VJ (1998) Disruption of the cyclin D/cyclin-dependent kinase/INK4/retinoblastoma protein regulatory pathway in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 58(12):2624–2632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echalier A, Endicott JA, Noble ME (2010) Recent developments in cyclin-dependent kinase biochemical and structural studies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804(3):511–519. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers JP, Grandgenett PM, Collisson EC, Lewallen ME, Tremayne J, Singh PK et al (2011) Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 is amplified and overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and activated by mutant K-Ras. Clin Cancer Res 17(19):6140–6150. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-2288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg J, Holm C, Jalili S, Richter J, Anagnostaki L, Landberg G et al (2005) Expression of cyclin A1 and cell cycle proteins in hematopoietic cells and acute myeloid leukemia and links to patient outcome. Eur J Haematol 75(2):106–115. 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00473.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson M, Portin C, Linderholm B, Lindh J, Roos G, Landberg G (1998) Expression of cyclin E and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 in malignant lymphomas-prognostic implications. Blood 92(3):770–777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T, Rosenthal ET, Youngblom J, Distel D, Hunt T (1983) Cyclin: a protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell 33(2):389–396. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90420-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein R, Bass AJ, Kim SY, Dunn IF, Silver SJ, Guney I et al (2008) CDK8 is a colorectal cancer oncogene that regulates beta-catenin activity. Nature 455(7212):547–551. 10.1038/nature07179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein R, Shima K, Nosho K, Irahara N, Baba Y, Bojarski E et al (2010) CDK8 expression in 470 colorectal cancers in relation to beta-catenin activation, other molecular alterations and patient survival. Int J Cancer 126(12):2863–2873. 10.1002/ijc.24908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RP (2005) Secrets of a double agent: CDK7 in cell-cycle control and transcription. J Cell Sci 118(Pt 22):5171–5180. 10.1242/jcs.02718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster I (2008) Cancer: a cell cycle defect. Radiography 14(2):144–149. 10.1016/j.radi.2006.12.001 [Google Scholar]

- Furihata M, Ishikawa T, Inoue A, Yoshikawa C, Sonobe H, Ohtsuki Y et al (1996) Determination of the prognostic significance of unscheduled cyclin A overexpression in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2(10):1781–1785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gali-Muhtasib H (2006) Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors from natural sources: recent advances and future prospects for cancer treatment. Adv Phytomed 2:155–167. 10.1016/S1572-557X(05)02009-X [Google Scholar]

- Gansauge S, Gansauge F, Ramadani M, Stobbe H, Rau B, Harada N et al (1997) Overexpression of cyclin D1 in human pancreatic carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. Cancer Res 57(9):1634–1637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Reyes B, Kretz AL, Ruff JP, von Karstedt S, Hillenbrand A, Knippschild U et al (2018) The emerging role of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 19(10):3219. 10.3390/ijms19103219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautschi O, Ratschiller D, Gugger M, Betticher DC, Heighway J (2007) Cyclin D1 in non-small cell lung cancer: a key driver of malignant transformation. Lung Cancer 55(1):1–14. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva J, Sinha P, Schadendorf D (2001) Expression of cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases in human benign and malignant melanocytic lesions. J Clin Pathol 54(3):229–235. 10.1136/jcp.54.3.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett C, Fantl V, Smith R, Fisher C, Bartek J, Dickson C et al (1994) Amplification and overexpression of cyclin D1 in breast cancer detected by immunohistochemical staining. Cancer Res 54(7):1812–1817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel B, Tripathi N, Bhardwaj N, Jain SK (2020) Small molecule CDK inhibitors for the therapeutic management of cancer. Curr Top Med Chem 20(17):1535–1563. 10.2174/1568026620666200516152756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greifenberg AK, Hönig D, Pilarova K, Düster R, Bartholomeeusen K, Bösken CA et al (2016) Structural and functional analysis of the Cdk13/Cyclin K complex. Cell Rep 14(2):320–331. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Wang C, Li W, Hsu FN, Tian L, Zhou J et al (2013) Tumor-suppressive effects of CDK8 in endometrial cancer cells. Cell Cycle 12(6):987–999. 10.4161/cc.24003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa K, Yamakawa M, Takeda H, Kimura S, Takahashi T (1999) Expression of cell cycle markers in colorectal carcinoma: superiority of cyclin A as an indicator of poor prognosis. Int J Cancer 84(3):225–233. 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990621)84:3%3c225::aid-ijc5%3e3.0.co;2-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, Postigo AA, Dean DC (1999) Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell 98(6):859–869. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Weinert TA (1989) Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science 246(4930):629–634. 10.1126/science.2683079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Culotti J, Pringle JR, Reid BJ (1974) Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. Science 183(4120):46–51. 10.1126/science.183.4120.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwell RM, Mull BB, Porter DC, Keyomarsi K (2004) Activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by full length and low molecular weight forms of cyclin E in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 279(13):12695–12705. 10.1074/jbc.M313407200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Fang X, Xia X, Hou T, Zhang T (2020) Targeting CDK9: A novel biomarker in the treatment of endometrial cancer. Oncol Rep 44(5):1929–1938. 10.3892/or.2020.7746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Dowdy SF (2002) Regulation of G(1) cell-cycle progression by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 12(1):47–52. 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00263-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Mayeda A, Trembley JH, Lahti JM, Kidd VJ (2003) CDK11 complexes promote pre-mRNA splicing. J Biol Chem 278(10):8623–8629. 10.1074/jbc.M210057200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Du R, Jia X, Liu K, Qiao Y, Wu Q et al (2022) CDK15 promotes colorectal cancer progression via phosphorylating PAK4 and regulating β-catenin/ MEK-ERK signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ 29(1):14–27. 10.1038/s41418-021-00828-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas P, Cortés-Ledesma F, Sartori AA, Aguilera A, Jackson SP (2008) CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature 455(7213):689–692. 10.1038/nature07215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T, Nasmyth K, Novák B (2011) The cell cycle. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366(1584):3494–3497. 10.1098/rstb.2011.0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husdal A, Bukholm G, Bukholm IR (2006) The prognostic value and overexpression of cyclin A is correlated with gene amplification of both cyclin A and cyclin E in breast cancer patient. Cell Oncol 28(3):107–116. 10.1155/2006/721919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huuhtanen RL, Blomqvist CP, Böhling TO, Wiklund TA, Tukiainen EJ, Virolainen M et al (1999) Expression of cyclin A in soft tissue sarcomas correlates with tumor aggressiveness. Cancer Res 59(12):2885–2890 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydbring P, Malumbres M, Sicinski P (2016) Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17(5):280–292. 10.1038/nrm.2016.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman M, Lindon C, Nigg EA, Pines J (2003) Active cyclin B1-Cdk1 first appears on centrosomes in prophase. Nat Cell Biol 5(2):143–148. 10.1038/ncb918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Huang R, Wu Y, Diao P, Zhang W, Li J et al (2019) Overexpression of CDK7 is associated with unfavourable prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology 51(1):74–80. 10.1016/j.pathol.2018.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YS, Qian Y, Chen X (2010) Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity. Cell Signal 22(7):1003–1012. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldis P, Solomon MJ (2000) Analysis of CAK activities from human cells. Eur J Biochem 267(13):4213–4221. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Li G, Son J, Xu CF, Margueron R, Neubert TA et al (2010) Phosphorylation of the PRC2 component Ezh2 is cell cycle-regulated and up-regulates its binding to ncRNA. Genes Dev 24(23):2615–2620. 10.1101/gad.1983810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A, Goldberg MS, Cumberland LK, Ratnakumar K, Segura MF, Emanuel PO et al (2010) The histone variant macroH2A suppresses melanoma progression through regulation of CDK8. Nature 468(7327):1105–1109. 10.1038/nature09590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst AM, Jones PM, Vena N, Ligon AH, Liu JF, Hirsch MS et al (2014) Cyclin E1 deregulation occurs early in secretory cell transformation to promote formation of fallopian tube-derived high-grade serous ovarian cancers. Cancer Res 74(4):1141–1152. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-13-2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyomarsi K, Conte D Jr, Toyofuku W, Fox MP (1995) Deregulation of cyclin E in breast cancer. Oncogene 11(5):941–950 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Diehl JA (2009) Nuclear cyclin D1: an oncogenic driver in human cancer. J Cell Physiol 220(2):292–296. 10.1002/jcp.21791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MY, Han SI, Lim SC (2011) Roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 8 and β-catenin in the oncogenesis and progression of gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol 38(5):1375–1383. 10.3892/ijo.2011.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T (2015) Entry into mitosis: a solution to the decades-long enigma of MPF. Chromosoma 124(4):417–428. 10.1007/s00412-015-0508-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara K, Yasui W, Kuniyasu H, Yokozaki H, Akama Y, Yunotani S et al (1995) Concurrent amplification of cyclin E and CDK2 genes in colorectal carcinomas. Int J Cancer 62(1):25–28. 10.1002/ijc.2910620107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen KE, Diehl JA, Haiman CA, Knudsen ES (2006) Cyclin D1: polymorphism, aberrant splicing and cancer risk. Oncogene 25(11):1620–1628. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsami MK, Tsantoulis PK, Kouloukoussa M, Apostolopoulou K, Pateras IS, Spartinou Z et al (2006) Centrosome abnormalities are frequently observed in non-small-cell lung cancer and are associated with aneuploidy and cyclin E overexpression. J Pathol 209(4):512–521. 10.1002/path.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz AL, Schaum M, Richter J, Kitzig EF, Engler CC, Leithäuser F et al (2017) CDK9 is a prognostic marker and therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Tumour Biol 39(2):1010428317694304. 10.1177/1010428317694304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak JZ, El Dika M (2011) Canonical and alternative pathways in cyclin-dependent kinase 1/Cyclin B inactivation upon M-phase exit in xenopus laevis cell-free extracts. Enzyme Res 2011:523420. 10.4061/2011/523420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe JC, Lee MG, Nurse P, Picard A, Doree M (1988) Activation at M-phase of a protein kinase encoded by a starfish homologue of the cell cycle control gene cdc2+. Nature 335(6187):251–254. 10.1038/335251a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe JC, Picard A, Peaucellier G, Cavadore JC, Nurse P, Doree M (1989) Purification of MPF from starfish: identification as the H1 histone kinase p34cdc2 and a possible mechanism for its periodic activation. Cell 57(2):253–263. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90963-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti JM, Valentine M, Xiang J, Jones B, Amann J, Grenet J et al (1994) Alterations in the PITSLRE protein kinase gene complex on chromosome 1p36 in childhood neuroblastoma. Nat Genet 7(3):370–375. 10.1038/ng0794-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Shin GY, Qiu H (2020) The role of cell cycle regulators in cell survival-dual functions of cyclin-dependent kinase 20 and p21(Cip1/Waf1). Int J Mol Sci 21(22):8504. 10.3390/ijms21228504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle S, Amat R, Glover-Cutter K, Sansó M, Zhang C, Allen JJ et al (2012) Cyclin-dependent kinase control of the initiation-to-elongation switch of RNA polymerase II. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19(11):1108–1115. 10.1038/nsmb.2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie G, St-Pierre Y (2011) Phosphorylation of human DNMT1: implication of cyclin-dependent kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409(2):187–192. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Nurse P (1987) Complementation used to clone a human homologue of the fission yeast cell cycle control gene cdc2. Nature 327(6117):31–35. 10.1038/327031a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Zeidner JF (2019) Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 9 and 4/6 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a promising therapeutic approach. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 28(11):989–1001. 10.1080/13543784.2019.1678583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshchenko VV, Kuo PY, Shaknovich R, Yang DT, Gellen T, Petrich A et al (2010) Genomewide DNA methylation analysis reveals novel targets for drug development in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 116(7):1025–1034. 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung WK, Ching AK, Chan AW, Poon TC, Mian H, Wong AS et al (2011) A novel interplay between oncogenic PFTK1 protein kinase and tumor suppressor TAGLN2 in the control of liver cancer cell motility. Oncogene 30(44):4464–4475. 10.1038/onc.2011.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levacque Z, Rosales JL, Lee KY (2012) Level of cdk5 expression predicts the survival of relapsed multiple myeloma patients. Cell Cycle 11(21):4093–4095. 10.4161/cc.21886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Gaillard F, Moreau A, Harousseau JL, Laboisse C, Milpied N et al (1999) Detection of translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32) in mantle cell lymphoma by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Pathol 154(5):1449–1452. 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65399-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JQ, Miki H, Wu F, Saoo K, Nishioka M, Ohmori M et al (2002) Cyclin A correlates with carcinogenesis and metastasis, and p27(kip1) correlates with lymphatic invasion, in colorectal neoplasms. Hum Pathol 33(10):1006–1015. 10.1053/hupa.2002.125774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]