Abstract

Background

Ovarian cancer (OC) is a prevalent gynecological malignancy with the highest mortality rate, which generally diagnosed at late stages due to the lack of effective early screening methods and the nonspecific symptoms. Hence, here we aim to identify new metastasis markers and develop a novel detection method with the characteristics of high sensitivity, rapid detection, high specificity, and low cost when compared with other conventional detection technologies.

Methods

Blood from OC patients with or without metastasis were collected and analyzed by 4D Label free LC − MS/MS. Surgically resect samples from OC patients were collected for Single cell RNA sequencing (sc-RNA seq). Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) was used to silence SAA1 expression in SKOV3 and ID8 to verify the relationship between endogenous SAA1 and tumor invasion or metastasis. The functional graphene chips prepared by covalent binding were used for SAA1 detection.

Results

In our study, we identified Serum Amyloid A1 (SAA1) as a hematological marker of OC metastasis by comprehensive analysis of proteins in plasma from OC patients with or without metastasis using 4D Label free LC − MS/MS and gene expression patterns from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases. Further validation using tumor tissues and plasma from human OC and mouse OC model confirmed the correlation between SAA1 and tumor metastasis. Importantly, sc-RNA seq of human OC samples revealed that SAA1 was specifically expressed in tumor cells and upregulated in the metastasis group. The functional role of SAA1 in metastasis was demonstrated through experiments in vitro and in vivo. Based on these findings, we designed and investigated a graphene-based platform for SAA1 detection to predict the risk of metastasis of OC patients.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that SAA1 is a biomarker of OC metastasis, and we have developed a rapid and highly sensitive platform using graphene chips to detection of plasma SAA1 for the early assessment of metastasis in OC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-023-05296-8.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Metastasis, SAA1, Biomarker, Graphene chip, Rapid detection

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the deadliest gynecological cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death in women. Although treatment for OC has improved greatly in the recent decades, overall survival rates have not significantly improved (Moss et al. 2018; Penny 2020; Siegel et al. 2017; Skates and Singer 1991). One of the reasons for the high mortality rate in patients with OC is that the ovaries are located deep within the pelvic cavity, making it difficult to detect the disease in its early stages as it often presents with no or minimal symptoms. More than 60% of patients with OC are diagnosed with advanced stage at the time of detection, and the 5-year overall survival rate is less than 30%. Long-term survival in patients who have metastasized beyond the pelvis (stage III − IV) is 20% or less, in contrast, the 5-year overall survival rate for early patients (stage I–II) is more than 90% (Elias et al. 2018). Ultrasound and the protein biomarker CA125 are two of the best studied screening tools for OC (Menon et al. 2018). However, the CA125 does not always play a role in the early diagnosis of OC, so the development of new OC biomarkers is great significance for the detection and diagnosis (Bast et al. 2020; Nebgen et al. 2019).

Serum amyloid A (SAA) is a sensitive marker of acute response, produced by the liver in response to acute inflammation and tissue damage (Gabay and Kushner 1999; Sack 2020). SAA related genes and proteins contain a closely related family, including SAA1, SAA2, SAA3, and SAA4 (Betts et al. 1991; Sellar et al. 1994). The main functions of SAA1 are amyloid formation, high density lipoprotein remodeling and lipid metabolism, antibacterial functions, regulation of inflammation and immunity (Sun and Ye 2016). In addition, previous studies have shown that plasma SAA was potential biomarkers for cancer (Liu 2012; Malle et al. 2009), with clinical associations reported in several tumor types including breast cancer (du Plessis et al. 2022), glioblastoma (Knebel et al. 2017), lung cancer (Milan et al. 2012), esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (Shu et al. 2022), renal carcinoma (Li et al. 2021), and OC (Urieli-Shoval et al. 2010).

Liquid biopsy is a method of capturing and analyzing tumor-related biomarkers such as circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor nucleic acids, proteins, and tumor derived extracellular vesicles in liquid samples (Chen et al. 2019; Martins et al. 2021). Liquid biopsy has the advantage of small wound and has the potential to be widely used in the early diagnosis and monitoring of metastases in cancer patients (Martins et al. 2021; Mattox et al. 2019). Graphene-based nanomaterials, known for their excellent biocompatibility, electrical conductivity, hydrophilicity, and mechanical flexibility, have emerged as a versatile platform for biomedical detection (Gao et al. 2014; Ozkan-Ariksoysal 2022; Pumera 2011). In addition, using graphene as a biosensor interface has been shown to effectively improve the sensitivity and specificity of biosensors in cancer detection (Khosravi et al. 2016; Orecchioni et al. 2015).

Here, tissue samples and plasma from OC patients with or without metastasis were collected for proteomic analysis and single cell RNA sequencing (sc-RNA seq). We found that SAA1 expression was increased in plasma and tumor cells of OC patients with metastasis. In vivo studies using a mouse ID8 OC model also showed that plasma SAA1 is a potential biomarker for OC metastasis. In vitro cell experiments and in vivo animal models demonstrated that SAA1 knockdown inhibit invasion and metastasis of tumor cell. Based on our results, we developed a graphene-based assay to rapidly detect the abundance of SAA1 protein in the plasma of OC patients.

Materials and methods

Patient

Fresh OC samples and venous blood were obtained from patients with or without metastasis at the West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University. All recruited individuals gave written informed consent, and the ethics review board of the Sichuan University approved the protocol. To obtain the plasma from OC patients, peripheral whole blood was drawn in EDTA tubes (Fisher Scientific). Within 3 h of collection, blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min, then subpackaged and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. The participants' clinical information is summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 4D Label free LC–MS/MS study cohorts

| Patient | Age (y) | Gender | Histology subtype | FIGO stage | Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmetastasis_1 | 32 | Female | HGSC | I | No |

| Nonmetastasis_2 | 38 | Female | HGSC | I | No |

| Nonmetastasis_3 | 55 | Female | HGSC | I | No |

| Metastasis_1 | 47 | Female | HGSC | III | Yes |

| Metastasis_2 | 54 | Female | HGSC | III | Yes |

| Metastasis_3 | 46 | Female | HGSC | III | Yes |

FIGO the international federation of gynecology and obstetrics; HGSC high-grade serous carcinoma

Table 2.

Characteristics of the sc-RNA seq study cohorts

| Patient | Age (y) | Gender | Histology subtype | FIGO stage | Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmetastasis | 55 | Female | HGSC | I | No |

| Metastasis | 47 | Female | HGSC | III | Yes |

HGSC high-grade serous carcinoma

Table 3.

Characteristics of the IHC staining cohorts

| Feature | Normal | Nonmetastasis | Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 17 | 19 | 27 |

| Age (y) | |||

| Mean (range) | 51.8 (30–68) | 56.9 (29–79) | 56.7 (39–75) |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female |

| Histology subtype | |||

| HGSC | 4 (23.5%) | 8 (42.1%) | 22 (81.5%) |

| EC | 8 (47.1%) | 7 (36.8%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| CCC | 5 (29.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| FIGO stage | |||

| I | 10 (58.8%) | 19 (100%) | |

| III/IV | 7 (41.2%) | 27 (100%) | |

| Metastasis | 27 (100%) |

Normal, paracancer tissue from ovarian cancer patients; HGSC high-grade serous carcinoma; CCC clear-cell carcinoma; EC endometrioid carcinoma

4D Label free LC − MS/MS of plasma

The 4D-label-free-based quantitative proteomic analysis of plasma was carried out by Metware Biotechnology Inc (Wuhan, China). For each sample, the high abundance proteins were removed by ProteoMiner Protein Enrichment Small-Capacity Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the kit’s instruction, the final eluent was collected. Equal amount of proteins from each sample (~ 100 μg) were used for tryptic digestion. Trypsin was added at an enzyme − protein ratio of 1:50 (w/w), the digest reaction was performed at 37 °C for 12–16 h. After digestion, peptides were desalted using C18 Cartridge followed by drying with Vacuum concentration meter. Liquid chromatography (LC) was performed on a nanoElute UHPLC (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). MS raw data were analyzed with FragPipe(v17.1) which relies on MSFragger for qualitative analysis and uses Phosopher for validation and filtering. For label-free quantitation, IonQuant mode was used, and mode of TMT-Integrator was used to perform isobaric labeling-based quantification (TMT/iTRAQ). Proteins denoted as contaminants were removed, the remaining identifications were used for further quantification analysis.

sc-RNA seq of human OC samples

Fresh OC samples from patients with or without metastasis were collected from the West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University and stored in the cold DMEM medium. Before dissociation, fat, fibrous and necrotic areas of tumor samples should be removed. Cut the tumor into small pieces and dissociate the tumor pieces into the gentleMACS C Tube (Miltenyi Biotec, cat#130–093-237, # 130–096-334) containing the enzyme mix of Tumor Dissociation Kit, human (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat#130–095-929). The tumor pieces were digested using the gentleMACSTM Octo Dissociator with Heater (Miltenyi Biotec, cat#130–096-427) according to 37C_h_TDK_1 program followed by washing and removing of erythrocytes. Single cells suspensions with the viability ≥ 90% loaded into Chromium microfluidic chips with 30 v2 chemistry and barcoded with a 10 × Chromium Controller (10X Genomics). RNA from the barcoded cells was subsequently reverse-transcribed and sequencing libraries constructed with reagents from a Chromium Single Cell 30 v2 reagent kit (10X Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed with Illumina (HiSeq 2000 or NovaSeq, depends on project) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). The related data analysis was performed by Novogene (Beijing, China).

sc-RNA seq data analysis

For 10 × dataset, sequencing reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg38) using STAR aligner (v2.5.2b), estimated cell-containing partitions and associated UMI using the Cell Ranger (v6.0.1) single-cell software suite. Seurat object was created out by reading expression matrix, and cells with low gene number were preliminarily filtered. To guarantee the quality of downstream analysis, we only retained the cells with mitochondrial genes content less than 25% and ribosomal genes content less than 40%. 14,597 cells were collected after quality control. The data were standardized and the highly variable genes were found for downstream analysis. Seurat v3 was used for the integration, reduction, and clustering of sc-RNA seq datasets. CCA methods were used for sample integration, and the linear dimension reduction of the data was carried out by PCA to determine the data dimension. Then the data were analyzed by clustering according to the data dimension. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction of samples was carried out using umap to obtain the data of each cell community. marker gene of each cell group was obtained by finding the difference gene between each cell group and other groups. According to the experience combined with the published literature and marker gene website (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CellMarker/) to identification and annotation of colony, to observe the difference of each cell.

TCGA and GEO data analysis

Transcriptomic data and clinical data for OC patients were downloaded from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). OC patient data from the TCGA database or GSE178913 were used to analyze the changes of different genes expression in patients and for survival analysis.

Cell culture

SKOV3, ID8 and 293 T cell lines were obtained from State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, Sichuan University. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco, REF#C11995500BT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cell-Box, AUS-01S-02), 100 units/mL penicillin − streptomycin (Gibco, 15,070,063). Cells were cultured at 37ºC in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Generation of SAA1 knockdown cells

pLKO.1-TRC, pMD2.G and pSPAX2 were obtained from State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, Sichuan University. pLKO.1-TRC vectors were used to generate lentivirus to knock down SAA1. The pLKO.1-TRC cloning vector contains a 1.9 kb stuffer that is released upon digestion with EcoRI and AgeI. The oligos of the shRNA sequence are compatible with the sticky ends of EcoRI and AgeI. Forward and reverse oligos are annealed and ligated into the pLKO.1 vector, producing a final plasmid that expresses the shRNA of interest. For lentivirus manufacture, 293 T cells were incubated with 4 μg of pLKO.1-shRNA or empty, 3 μg pSPAX2, 2 μg pMD2.G and 20 μl lipo 6000 reagent (Beyotime, C0526-0.5 ml) diluted in 5 ml of Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, 31,985,070). Medium was changed to antibiotic-free DMEM after 6 h and once again after 24 h. Medium containing the shRNA lentivirus was collected, filtered (0.45 μm filter, BIOFIL) and add to the cells. ID8/SKOV3 cells were grown to a confluence of 50% and incubated in shRNA lentivirus medium. 48 h after transfection, medium was changed to new culture-medium, supplemented with 2 μg/ml of puromycin (Gibco, A1113803). The primers used for shRNA are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The sequences of primers used for real-time qPCR and shRNA

| Human SAA1-sh1 | CCGGTCCAGAGAGAATATCCAGAGATTTCAAGAGAATCTCTGGATATTCTCTCTGGTTTTTTG |

| Human SAA1-sh2 | CCGGTGCCTACTCTGACATGAGAGAATTCAAGAGATTCTCTCATGTCAGAGTAGGCTTTTTTG |

| Mouse SAA1-sh1 | CCGGTCGTCCTCCTATTAGCTCAGTATTCAAGAGATACTGAGCTAATAGGAGGACGTTTTTTG |

| Mouse SAA1-sh2 | CCGGTAGTGATGGAAGAGAGGCCTTTTTCAAGAGAAAAGGCCTCTCTTCCATCACTTTTTTTG |

| Mouse GAPDH Forward | GTGCCGCCTGGAGAAACCT |

| Mouse GAPDH Reverse | TGAAGTCGCAGGAGACAACC |

| Mouse SAA1 Forward | GGAGTCTGGGCTGCTGAGAAAA |

| Mouse SAA1 Reverse | TGTCTGTTGGCTTCCTGGTCAG |

| Human GAPDH Forward | GGTCATCCATGACAACTTTGG |

| Human GAPDH Reverse | GGCCATCACGCCACAG |

| Human SAA1 Forward | TCGTTCCTTGGCGAGGCTTTTG |

| Human SAA1 Reverse | AGGTCCCCTTTTGGCAGCATCA |

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

The total RNA was extracted by TRIzol (ambion, 15,596,026) unless otherwise stated. Then, 1 µg of RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, RR047A) according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. The cDNA was subjected to quantitative by ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q711-2). The primers used for PCR are shown in Table 4.

Western blot

The total protein was extracted with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, P0013B) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Bimake, B14011) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Bimake, B15002). For western blot, the proteins were loaded into 12% polyacrylamide − SDS gradient gels and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The PVDF membrane was incubated overnight at 4℃ with SAA1 (Biorbyt, orb228668, 1:200) or β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog A5441, 1:3000) to detect the effect of SAA1 knockdown.

Wound healing assay

1.0 × 106cells were cultured in a 6 cm plate until they reached a near confluent monolayer. This monolayer was subsequently scratched with a 200 μl culture tip. Subsequently, the wounded cultures were visualized in serum-free medium at 0 and 24 h, and images were captured to detect the migratory ability. Three imaging views were investigated on each plate to quantify the migration rates.

Matrigel invasion assay

Matrigel invasion assay using a Millicell chamber (Corning, 3422). The Transwell chambers were precoated with 50 µl mixture (Matrigel: serum-free medium 1:3, Corning, 356,234) and the stable clone cell lines (1.0 × 105) in 100 µl serum-free medium were seeded onto the upper chamber for 24 h according to the instructions of the Transwell migration assay.

Mice model

All mice work was performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University. 4–6 weeks female wild-type C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from Chengdu Gembio. The mice were exposed to a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, bred as specified-pathogen-free and given food and water ad libitum. For the primary model, ID8 cells were digested with pancreatic enzyme and then resuspended with matrigel. After anesthesia, the mice were injected with 20 μl diluted ID8 cell suspension through the oviduct with a concentration of 1.0 × 108 cells /ml. The final injected cell number of each mouse was 2.0 × 106 cells. For ID8 intravenous injection models, ID8 cells were digested with pancreatic enzyme and then resuspended with PBS. 2.0 × 106 ID8 cells were intravenously injected into the tail vein of C57BL/6 female mice. After 60 days of injection, all mice were sacrificed, the related lungs were harvested, and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological examination. The results were analyzed by quantification of number of lung metastasis.

Plasma isolation from mice

Blood samples were collected from the portal vein and left ventricle of the heart, and allowed to clot at room temperature for 20 min. Samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm, 4 °C for 20 min. Supernatant was transferred to a polypropylene tube and stored at − 80 °C for downstream applications. Plasma was not heat inactivated unless indicated otherwise.

SAA1 detection

SAA1 were determined by ELISA (Invitrogen, KMA0021). Plasma samples were diluted with the standard diluent buffer provided with the kit. The optical density is measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 450 nm. The optical density value is proportional to the concentration of SAA1. By comparing the optical density value of the sample with the standard curve, the concentration of mouse SAA1 in the sample can be calculated.

SAA1 detected by graphene chip

The graphene chips are purchased from Chengdu Ginkgo Electronics Technology Co., Ltd, and manufactured in the same way as previously described (Wan et al. 2021). Covalent binding method was used to coupling the agent 1-pyrene-butanoic acid succinimidyl ester (PASE) on the surface of graphene to covalently bind antibodies. First, graphene chips were incubated in 1 mM PASE (ANASPEC) solution (soluble in methanol) for 2 h at room temperature, then rinsed 3 times with methanol. Next, the chips were incubated with SAA1 (Biorbyt, orb228668) antibody overnight at 4℃. The chips were rinsed with PBS three times the next morning, and incubated with 0.5% Tween-20 at room temperature for 2 h to block the unfunctionalized parts of the graphene and reduce nonspecific binding. After incubation, the chips were rinsed twice with PBS and used for plasma detection of OC patients. The nanomaterials graphene was assembled between the source electrode and the drain electrode to form a conductive channel as the sensing element of the Field Effect Transistor (FET). When the target antigen is present, the specific binding of antigen and antibody can cause changes in the electrical signal of the sensor, and the expression of the target antigen can be deduced. The electrical signal was recorded by Agilent 4155B semiconductor analyzer.

Quantification of metastatic foci in the lung

After animal sacrifice, lungs were harvested and immersed in 4% formalin. The tissues were processed for histological examination by embedding in paraffin and hematoxylin eosin stain. Tumor metastasis were counted in the tissue section of the entire lung in each mouse. The number of metastasis less than 6 was defined as low metastasis, otherwise considered high metastasis.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of the SAA1 was performed on 8 μm paraffin sections from OC tissue. The participants' clinical information is summarized in Table 3. The sections were then deparaffinized, rehydrated and treated in 10 mM citrate buffer (100 °C, 10 min) for antigen repair. Subsequently, the sections were immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxidase for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with SAA1 (Biorbyt, orb228668, 1:200), followed by incubation with the HRP conjugated Goat antirabbit IgG (Servicebio, GB23303). Then DAB display kit (ZSGB-BIO, ZIL-9019) was used for color development.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS statistics 22 and Graphpad Prism 8. Comparison between two groups was performed using Student’s t test, and difference analysis of three or more groups was performed pair-to-pair using one-way ANOVA combined with Post hoc test. The statistical difference between groups is indicated on graphs with stars: the stars (from 1 to 3 stars) respectively represent p-values less than 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001.

Results

Serum Amyloid A1 is a risk factor for ovarian cancer

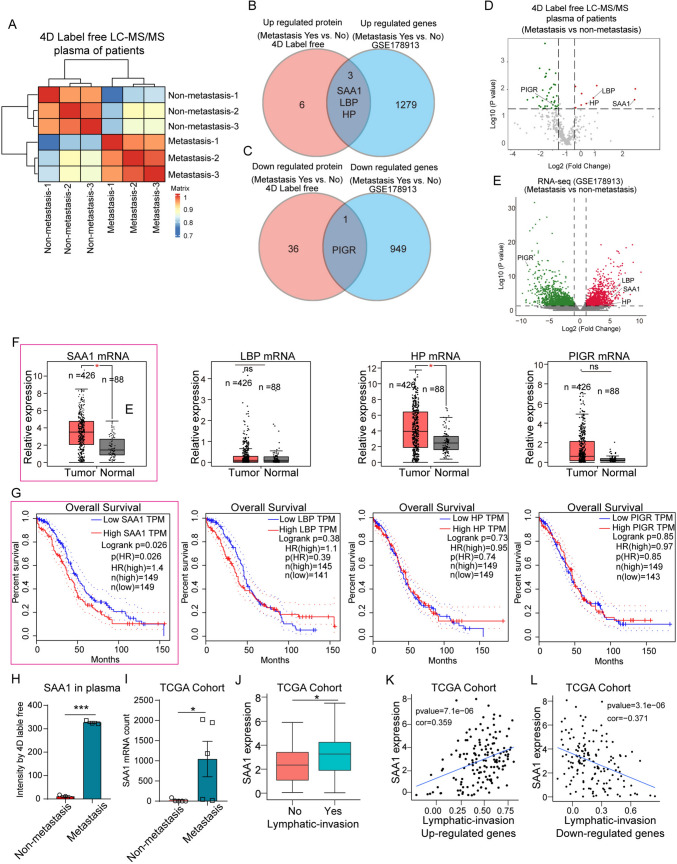

In order to identify potential biomarkers of OC, venous blood from six high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) patients with or without metastasis were collected and quantitatively analyzed by 4D Label free LC–MS/MS (Fig. 1A). Patients with acute infectious diseases and other chronic diseases were excluded. A total of 9 upregulated proteins and 37 downregulated proteins were identified by LC − MS (Supplementary Table 1). These proteins were analyzed with 5 pairs mRNA profile of ovarian tumors from primary and omental metastasis (GSE178913) (Fig. 1B, C; Supplementary Table 2). We found the plasma protein and tumor tissue RNA expression levels of SAA1, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), haptoglobin (HP) were significantly increased in OC patients with metastasis, while the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR) expression levels were decreased (Fig. 1B, C). Figure 1D and E showed the change of these genes in the two data sets. By analyzing the data from TCGA, mRNA expression levels of SAA1 and HP were significantly increased in OC tissues, while LBP and PIGR showed no difference between normal and tumor tissues (Fig. 1F). In addition, only the expression levels of SAA1 significantly associated with overall survival of OC patients (Fig. 1F, G). LC − MS/MS and RNA-seq analysis (TCGA) showed that SAA1 was significantly elevated in plasma and tumor tissue of OC patients with metastasis (Fig. 1H, I). Moreover, high expression of SAA1 is relate to tumor lymphatic invasion (Fig. 1J−L). The previous studies have shown that SAA1 is connected with the malignancy of different tumors. Our results suggest that SAA1 was highly expressed in plasma and tumor tissue of OC metastatic patients, indicating SAA1 is significantly associated with OC metastasis, and is a risk factor for OC.

Fig. 1.

SAA1 is a risk factor for OC. A Heatmap of the predicted similarity score. B Venn diagram for significant upregulated proteins or mRNA in OC patients (metastasis vs nonmetastasis). C Venn diagram for significant downregulated proteins or mRNA in OC patients (metastasis vs nonmetastasis). D Volcano plot show log2-transformed fold change of plasma proteins between OC patients with metastasis (n = 3) and nonmetastasis (n = 3). E Volcano plot show log2-transformed fold change of gene expression in tumor tissues between OC patients with metastasis and nonmetastasis (GSE178913). F TCGA database analysis showed SAA1, LBP, HP, and PIGR relative expression in tumor or normal tissue. G Overall survival analysis of OC patients with high or low expression of SAA1, LBP, HP and PIGR in tumor tissues. H SAA1 protein of plasma in different OC patients (metastasis vs nonmetastasis). I SAA1 mRNA expression level in OC patients (metastasis vs nonmetastasis). J Relationship between SAA1 and tumor lymphatic invasion. K SAA1 expression was positively correlated with the upregulated gene of lymphatic invasion. L SAA1 expression was negatively correlated with downregulated genes of lymphatic invasion. (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns means no significance)

SAA1 as a metastasis biomarker in OC

To further test whether SAA1 in plasma can be used as a marker of OC metastasis, ID8 cell were used for mouse primary OC model. By analyzing the relationship between plasma SAA1 and lung metastasis, we found that SAA1 was significantly increased in mice with high metastasis (Fig. 2A–C; lung metastatic lesion < 6, low metastasis; lung metastatic lesion ≥ 6, high metastasis). Immunohistochemical (IHC) was also performed on tissue slices from 63 OC patients, the participants’ clinical information is summarized in Table 3. As shown in Fig. 2D and E, the SAA1 was upregulate in advanced patients with metastasis. In addition, we also performed IHC analysis of matched specimens from 3 OC patients before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) (Fig. 2F). The decreased expression of SAA1 in tumor tissues of patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy indicates that SAA1 can reflect the therapeutic effect. These results suggest that SAA1 expression in plasma and tumor tissue is closely related to metastasis, and can be used as a biomarker of tumor metastasis and prognosis.

Fig. 2.

SAA1 as a metastasis biomarker in OC. A Two cases of histologically detectable metastasis in lung of mouse with OC are shown. B Quantification of histologically detectable lung metastasis in mouse model of OC (low metastasis, n = 7; high metastasis, n = 7). C Comparison of SAA1 expression in plasma among low metastasis and high metastasis (low metastasis, n = 7; high metastasis, n = 7). D SAA1 IHC of normal, nonmetastasis, and metastasis cases of human OC. E Quantification of SAA1 staining in normal (n = 17), nonmetastasis (n = 19) and metastasis (n = 27). F IHC was used to detect the expression of SAA1 in 3 patients before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. NAC neoadjuvant chemotherapy (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05)

SAA1 is enriched in tumor cells

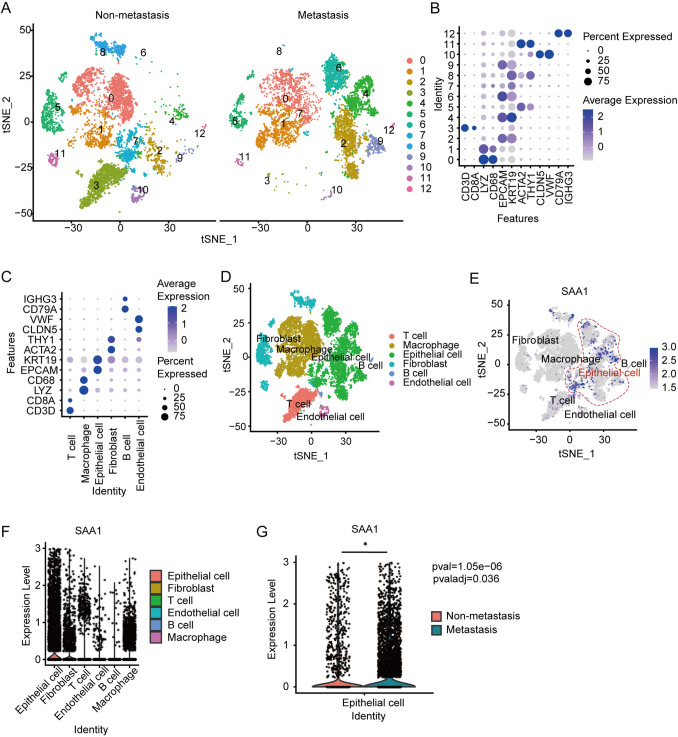

To explore which cells in the OC microenvironment contribute to the increase of SAA1 expression, we collected primary surgically resect samples from HGSC patients for sc-RNA seq. The participants’ clinical information is summarized in Table 2. Cells from two patients were divided into thirteen different subgroups by cluster analysis according to different maker genes (Fig. 3A, B), and six major cell groups were finally identified (Fig. 3C, D). These cell groups include lymphocytes (T and B cells), epithelial cells (considered OC cells), endothelial cells, macrophages, and fibroblast. The analysis showed that although all the cells expressed SAA1, tumor cells was higher than other cell cluster (Fig. 3E, F). When compared with OC cells without metastasis, tumor cells from patients with metastasis expressed higher levels of SAA1 (Fig. 3G). These results suggest that the expression of endogenous SAA1 in tumor cells is closely related to the metastasis of OC, and may play a role in the process of tumor cell metastasis.

Fig. 3.

SAA1 is enriched in tumor cells. A t-SNE plot of Seurat integration of all cells from human OC specimens of patients with or without metastasis, leads to 13 clusters. B Dot plot of the relative expression of established cellular markers (x axis) and the related number of cluster (y axis) of scRNA-seq date of OC. C, D The identification of cell types from scRNA seq date of OC patients. Dot plot of the relative expression of cellular markers (y axis) and the related cell types. E, F Expression level of SAA1 in different cells from OC microenvironment. G Expression level of SAA1 in epithelial cells from OC patients with or without metastasis. (*P < 0.05)

SAA1 promote metastasis of OC cells

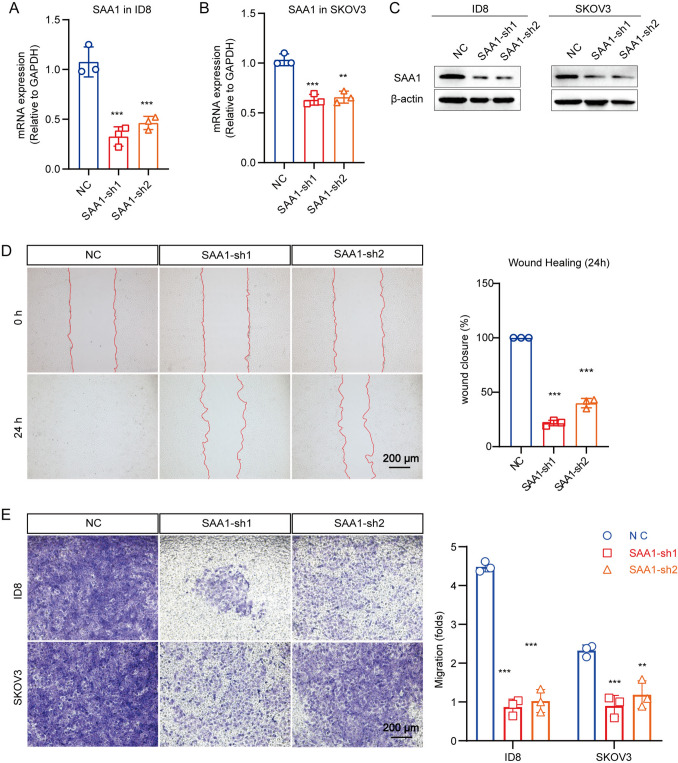

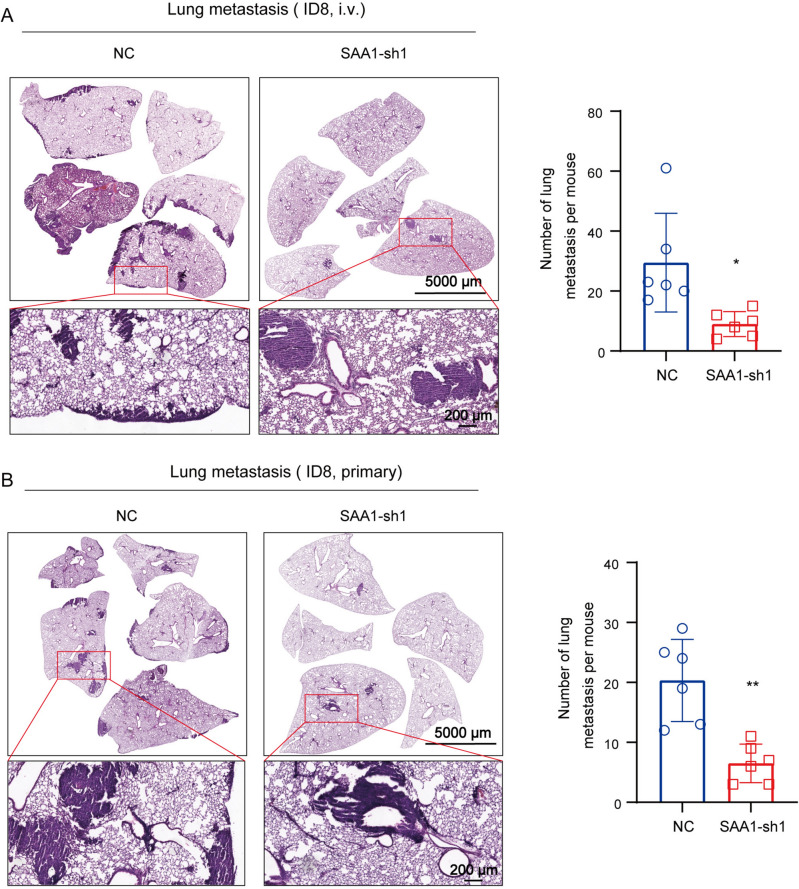

Previous results have shown that high expression of SAA1 in OC tumor cells may be associated with metastasis. To verify the relationship between endogenous SAA1 and tumor invasion or metastasis, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to silence SAA1 expression in human OC cell line SKOV3 and mouse OC cell line ID8. Real-time qPCR and western blot validated the knockdown effect of shRNA (Fig. 4A−C). The results of wound healing showed that when compared with NC, the wound closure of ID8 cells with SAA1 knockdown were significantly decreased after 24 h, indicating that the migration ability of tumor cells was reduce after SAA1 konckdown (Fig. 4D). However, SAA1 knockdown had no obvious effect on SKOV3 migration, which may be caused by the weak migration ability of the cells themselves. Subsequently, Transwell test were conducted to detect the effects of SAA1 knockdown on the invasion of SKOV3 and ID8 cells. Given the number of cells, we evaluated cell migration capacity based on the crystal violet staining area. The results showed that compared with the contrast, the invasiveness of SKOV3 and ID8 cells was significantly reduced after SAA1 inhibit (Fig. 4E). In addition, we conducted the ID8 mouse intravenous injection and primary models to verify the roles of SAA1 in metastasis. HE staining and the related quantification revealed that knockdown of SAA1 inhibits lung metastasis in both models (Fig. 5A, B). These results demonstrated in vivo that SAA1 promotes metastasis of OC. In summary, we believe that SAA1 promote the invasion and metastasis of OC, and high expression of SAA1 in tumor cells is a sign of malignant degeneration.

Fig. 4.

SAA1 promote migration of OC cell. A, B SAA1 mRNA expression, as assessed by qRT-PCR, in ID8/SKOV3 which were transfected with SAA1-shRNA (SAA1-sh1/2) or NC (empty) constructs. C SAA1 protein expression, as assessed by western blot, in ID8/SKOV3 which were transfected with SAA1-shRNA (SAA1-sh1/2) or NC (empty) constructs. D SAA1 regulates the metastatic phenotype of ID8. The ability of cell migration was evaluated by wound healing assay, and is expressed as the healing area of migrated cells. Representative photographs and statistical charts are shown for the SAA1-knockdown cells when compared with their corresponding control, respectively. E SAA1 knockdown inhibit the invasion ability of OC cells. Transwell assay based on the matrigel was used for the invasion analysis of ID8/SKOV3 cells with SAA1 knockdown. The related quantification is on the right. (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01)

Fig. 5.

SAA1 knockdown inhibit ID8 cell metastasis in vivo. A Left: representative image of lung metastasis in ID8 intravenous injection model; right: quantification of histologically detectable lung metastasis. (NC, n = 6; SAA1-sh1, n = 6). i.v.: intravenous. B Left: representative image of lung metastasis in ID8 primary model; right: quantification of histologically detectable lung metastasis. (NC, n = 6; SAA1-sh1, n = 6). (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05)

SAA1 detection of plasma by graphene chip

Previous studies have shown that plasma SAA1 is a marker of OC metastasis, so we tried to construct graphene chips for the rapid detection of SAA1. In order to detect target antigens, antibodies need to be loaded into the chip. Here, the graphene FET-functional chip is prepared by covalent binding (Fig. 6A). The integrity of the graphene chip needs to be tested before use. The graphene functional chip does not add liquid, and two direct current pins are inserted into the electrodes on two flanks. After directly switching on the power supply, the voltage test is carried out (Fig. 6B, C). The results show that the current signal increases with the voltage, the chip shows good electrical conductivity, indicating that the graphene chip has complete function (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Plasma SAA1 detection by graphene chip. A Schematic diagram of graphene chip detection principle. Covalent binding method was used to coupling the agent 1-pyrene-butanoic acid succinimidyl ester (PASE) on the surface of graphene to covalently bind antibodies. Tween-20 block the unfunctionalized parts of the graphene and reduce nonspecific binding. The nanomaterials graphene was assembled between the source electrode and the drain electrode to form a conductive channel as the sensing element of the FET. When the target antigen is present, the specific binding of antigen and antibody can cause changes in the electrical signal of the sensor, and the expression of the target antigen can be deduced. B Graphene chips. C The graphene chip was placed under the microscope and used for test. D Test the function of graphene chips. The graphene functional chip does not add liquid, and two direct current pins are inserted into the electrodes on two flanks. After directly switching on the power supply, the voltage test is carried out. E Plasma SAA1 detection of OC patiens (metastasis, H0-H2; non-metastasis, H3-H5)

Then we tested plasma from six OC patients with or without metastasis. Chips with identical electrical conductivity were used for detection. The data logger recorded the results once per second. SAA1 antigen in the plasma combines with the antibody on the chip to release chemical energy. This signal is picked up by the detection system and displayed as an amplified current signal. When the plasma was added to the graphene chip, a change in the current signal was detected immediately and reached a peak within half a minute. The current signal of all samples increased obviously after dripping (Fig. 6E). The plasma current peak value of patients with metastasis (H0, H1) was higher than that of patients without metastasis (H3, H4, H5), indicating a higher level of SAA1 protein in the plasma of patients with metastasis. These results indicate that our strategy can be used for the rapid detection of SAA1, and further optimization of processing is still needed to improve its sensitivity.

Discussion

In 1979, SAA was discovered as a biochemical marker that could differentiate between disseminated and localized/regional disease, as well as monitor response to therapy (Rosenthal and Sullivan 1979). In recent years, a lot of researchers have found that SAA is associated with a variety of tumors, including breast cancer, glioma, lung cancer, cervical cancer, renal carcinoma, stomach cancer, and ovarian cancer (du Plessis et al. 2022; Knebel et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2019; Li et al. 2021; Liu 2012; Malle et al. 2009; Milan et al. 2012; Rosenthal and Sullivan 1979; Shu et al. 2022). Proteomic analysis has identified SAAs, especially SAA1 as one of the top ten proteins upregulated in lung cancer patients, and mounting evidence suggests that increased SAA expression may be linked to cancer pathogenesis (Cho et al. 2004). For instance, in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer treated with EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, increased plasma SAA1 expression is an indicator of poor prognosis (Milan et al. 2012; Ren et al. 2014). SAA could serve as a potential diagnosis and treatment prediction biomarker (Li et al. 2020). Moreover, SAA promotes OVCAR-3 cell migration by regulating MMPs and EMT which may correlate with AKT pathway activation (Li et al. 2020). Therefore, SAA has been detected as a marker for OC (Moshkovskii et al. 2005). Consistently, we demonstrated that SAA1 is a biomarker of OC metastasis both in patients and mouse OC models. Sc-RNA seq of human OC samples by ourselves indicate that tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment were the major contributors to the increased expression of SAA1. Different from the previous work by other groups, we included in vivo studies to demonstrate the effect of SAA1 on OC metastasis. However, the mechanism of SAA1-mediated tumor metastasis is still poorly understood. A recent study found that hepatocytes coordinate tumor liver metastasis through activation of IL-6/STAT3 signaling, leading to the production of SAA. This alters the immune and fibrotic microenvironment of the liver to establish a metastasizing niche (Lee et al. 2019). Similarly, during the development of OC, increased SAA1 expression in tumor cells enhances their ability to metastasize, while plasma SAA1 in patients may also play a role in establishing a premetastatic niche, highlighting the potential of SAA1 as a marker for tumor metastasis to assist with disease diagnosis. Here, we identified that SAA1 could be used as a hematological marker of tumor metastasis for the early assessment of metastasis in OC patients. SAA1 can be identified as a critical prognostic gene due to higher SAA1 expression associated with overall survival (HR = 1.4, p < 0.05, Fig. 1G). In clinical practice, it is very important to predict the progression of tumor after treatment. In this study, SAA1 levels decreased significantly after treatment, and high expression of SAA1 is associated with poor survival and metastasis. This may be an ideal biomarker for predicting treatment outcomes and a reasonable therapeutic target for OC.

With advances in hardware technology and the development of nanomaterials, the combination of graphene and biosensors offers significant advantages over traditional biological analysis, such as faster and simpler detection, reduced analysis time, high sensitivity, rapid detection, high specificity, and low cost (Cordaro et al. 2020; Ozkan-Ariksoysal 2022; Pumera 2011; Wan et al. 2021). Our previous research has also demonstrated that graphene combined with antibodies can be used to detect tumor cells(Wan et al. 2021). Here, we functionalized graphene chips using PASE and attempted to detect SAA1 in plasma of OC patients (Oishi et al. 2022). The results confirmed that this method can be used to detect SAA1 protein in plasma. This method allows for the detection of SAA1 protein differences in plasma within half a minute, dramatically improving detection speed and enabling rapid screening of a large number of samples, leading to faster diagnosis and treatment initiation (Khosravi et al. 2016). The potential for this assay system to be applied to other tumor markers is an exciting area of research, and optimizing detection methods and improving the sensitivity of chips while reducing detection costs will be crucial moving forward.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to thank Bisen Ding (West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University) for providing the ID8, SKOV3 and 293T cells. We would also like to thank Xiaoqing Tang and Xiangqi Chen (West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University) for providing pLKO.1-TRC, pMD2.G and pSPAX2.

Abbreviations

- OC

Ovarian cancer

- SAA

Serum amyloid A

- sc-RNA seq

Single cell RNA sequencing

- TCGA

The cancer genome Atlas

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- IHC

Immunohistochemical

- NAC

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- FIGO

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- HGSC

High-grade serous carcinoma

- CCC

Clear-cell carcinoma

- EC

Endometrioid carcinoma

- LBP

Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein

- HP

Haptoglobin

- PIGR

Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- PASE

1-Pyrene-butanoic acid succinimidyl ester

- FET

Field effect transistor

Author contributions

ZC, AZ and YH conceived and designed the study. YZ and ZG developed the study methodology. YZ, YC and XD acquired, analyzed, and/or interpreted data. QW constructed graphene chips and detected the plasma. CX analyzed the TCGA, GEO database and sc-RNA Seq data. ZC and YH wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and all authors wrote, reviewed, and/or revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Science Foundation of China (82125002, 00402154A1062), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (23NSFSC0014) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (0040214153014).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All recruited individuals gave written informed consent, and the ethics review board of the West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University approved the protocol Medical Research 2020 (059).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yilin Zhao, Yao Chen and Qi Wan have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Yan Hu, Email: huyancsu@126.com.

Ai Zheng, Email: 894591422@qq.com.

Zhongwei Cao, Email: zhongweicao@scu.edu.cn.

References

- Bast RC Jr, Lu Z, Han CY, Lu KH, Anderson KS, Drescher CW, Skates SJ (2020) Biomarkers and strategies for early detection of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 29:2504–2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts JC, Edbrooke MR, Thakker RV, Woo P (1991) The human acute-phase serum amyloid A gene family: structure, evolution and expression in hepatoma cells. Scand J Immunol 34:471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SL, Chen CY, Hsieh JC, Yu ZY, Cheng SJ, Hsieh KY, Yang JW, Kumar PV, Lin SF, Chen GY (2019) Graphene oxide-based biosensors for liquid biopsies in cancer diagnosis. Nanomaterials (basel, Switzerland) 9:1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho WC, Yip TT, Yip C, Yip V, Thulasiraman V, Ngan RK, Yip TT, Lau WH, Au JS, Law SC et al (2004) Identification of serum amyloid a protein as a potentially useful biomarker to monitor relapse of nasopharyngeal cancer by serum proteomic profiling. Clin Cancer 10:43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaro A, Neri G, Sciortino MT, Scala A, Piperno A (2020) Graphene-based strategies in liquid biopsy and in viral diseases diagnosis. Nanomaterials (basel, Switzerland) 10:1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis M, Davis TA, Olivier DW, de Villiers WJS, Engelbrecht AM (2022) A functional role for serum amyloid A in the molecular regulation of autophagy in breast cancer. Front Oncol 12:1000925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias KM, Guo J, Bast RC Jr (2018) Early detection of ovarian cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 32:903–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C, Kushner I (1999) Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med 340:448–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Lian C, Zhou Y, Yan L, Li Q, Zhang C, Chen L, Chen K (2014) Graphene oxide-DNA based sensors. Biosens Bioelectron 60:22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi F, Trainor PJ, Lambert C, Kloecker G, Wickstrom E, Rai SN, Panchapakesan B (2016) Static micro-array isolation, dynamic time series classification, capture and enumeration of spiked breast cancer cells in blood: the nanotube-CTC chip. Nanotechnology 27:4403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knebel FH, Uno M, Galatro TF, Bellé LP, Oba-Shinjo SM, Marie SKN, Campa A (2017) Serum amyloid A1 is upregulated in human glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 132:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Stone ML, Porrett PM, Thomas SK, Komar CA, Li JH, Delman D, Graham K, Gladney WL, Hua X et al (2019) Hepatocytes direct the formation of a pro-metastatic niche in the liver. Nature 567:249–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Hou Y, Zhao M, Li T, Liu Y, Chang J, Ren L (2020) Serum amyloid a, a potential biomarker both in serum and tissue, correlates with ovarian cancer progression. J Ovarian Res 13:67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Cheng Y, Cheng G, Xu T, Ye Y, Miu Q, Cao Q, Yang X, Ruan H, Zhang X (2021) High SAA1 expression predicts advanced tumors in renal cancer. Front Oncol 11:649761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C (2012) Serum amyloid a protein in clinical cancer diagnosis. Pathol Oncol Res POR 18:117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Sodin-Semrl S, Kovacevic A (2009) Serum amyloid A: an acute-phase protein involved in tumour pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS 66:9–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins I, Ribeiro IP, Jorge J, Gonçalves AC, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, Melo JB, Carreira IM (2021) Liquid biopsies: applications for cancer diagnosis and monitoring. Genes 12:349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox AK, Bettegowda C, Zhou S, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (2019) Applications of liquid biopsies for cancer. Sci Transl Med 11:507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon U, Karpinskyj C, Gentry-Maharaj A (2018) Ovarian cancer prevention and screening. Obstet Gynecol 131:909–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan E, Lazzari C, Anand S, Floriani I, Torri V, Sorlini C, Gregorc V, Bachi A (2012) SAA1 is over-expressed in plasma of non small cell lung cancer patients with poor outcome after treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. J Proteom 76:91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshkovskii SA, Serebryakova MV, Kuteykin-Teplyakov KB, Tikhonova OV, Goufman EI, Zgoda VG, Taranets IN, Makarov OV, Archakov AI (2005) Ovarian cancer marker of 11.7 kDa detected by proteomics is a serum amyloid A1. Proteomics 5:3790–3797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HA, Berchuck A, Neely ML, Myers ER, Havrilesky LJ (2018) Estimating cost-effectiveness of a multimodal ovarian cancer screening program in the united states: secondary analysis of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). JAMA Oncol 4:190–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebgen DR, Lu KH, Bast RC Jr (2019) Novel approaches to ovarian cancer screening. Curr Oncol Rep 21:75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi Y, Ogi H, Hagiwara S, Otani M, Kusakabe K (2022) Theoretical analysis on the stability of 1-pyrenebutanoic acid succinimidyl ester adsorbed on graphene. ACS Omega 7:31120–31125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orecchioni M, Cabizza R, Bianco A, Delogu LG (2015) Graphene as cancer theranostic tool: progress and future challenges. Theranostics 5:710–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan-Ariksoysal D (2022) Current perspectives in graphene oxide-based electrochemical biosensors for cancer diagnostics. Biosensors 12:607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny SM (2020) Ovarian cancer: an overview. Radiol Technol 91:561–575 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumera M (2011) Graphene in biosensing. Mater Today 14:308–315 [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Wang H, Lu D, Xie X, Chen X, Peng J, Hu Q, Shi G, Liu S (2014) Expression of serum amyloid A in uterine cervical cancer. Diagn Pathol 9:16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal CJ, Sullivan LM (1979) Serum amyloid A to monitor cancer dissemination. Ann Intern Med 91:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack GH Jr (2020) Serum amyloid A (SAA) proteins. Subcell Biochem 94:421–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellar GC, Jordan SA, Bickmore WA, Fantes JA, van Heyningen V, Whitehead AS (1994) The human serum amyloid A protein (SAA) superfamily gene cluster: mapping to chromosome 11p15.1 by physical and genetic linkage analysis. Genomics 19:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Z, Guo J, Xue Q, Tang Q, Zhang B (2022) Single-cell profiling reveals that SAA1+ epithelial cells promote distant metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol 12:1099271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2017) Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 67:7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skates SJ, Singer DE (1991) Quantifying the potential benefit of CA 125 screening for ovarian cancer. J Clin Epidemiol 44:365–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Ye RD (2016) Serum amyloid A1: structure, function and gene polymorphism. Gene 583:48–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urieli-Shoval S, Finci-Yeheskel Z, Dishon S, Galinsky D, Linke RP, Ariel I, Levin M, Ben-Shachar I, Prus D (2010) Expression of serum amyloid a in human ovarian epithelial tumors: implication for a role in ovarian tumorigenesis. J Histochem Cytochem off J Histochem Soc 58:1015–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q, Han L, Guo Y, Yu H, Tan L, Zheng A, Chen Y (2021) Graphene-based biosensors with high sensitivity for detection of ovarian cancer cells. Molecules (basel, Switzerland) 26:7265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.