Abstract

Background

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents 80–90% of all kidney tumors and about 15–25% of patients will develop distant metastases. Systemic therapy represents the standard of care for metastatic patients, but stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) may play a relevant role in the oligoprogressive setting, defined as the progression of few metastases during an ongoing systemic therapy on a background of otherwise stable disease. Aim of the present study was to analyze the outcome of RCC patients treated with SABR on oligoprogressive metastases.

Materials and methods

In this monocenter study, we analyzed patients affected by RCC treated with SABR on a maximum of 5 cranial or extracranial oligoprogressive sites of disease. Endpoints were overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and toxicity.

Results

We included 74 oligoprogressions (26 intracranial and 48 extracranial) and 57 SABR treatments in 44 patients. Most common concomitant treatments were sunitinib (28, 49.1%), pazopanib (12, 21.0%) and nivolumab (11, 19.3%). Median follow-up was 19.0 months, and 1- and 2-year OS rates were 79.2% and 57.3%, respectively. Repeated SABR was a positive predictive factor for OS (p = 0.034). Median PFS was 9.8 months, with 1- and 2-year rates of 43.2% and 25.8%. At multivariable analysis, disease-free interval (p = 0.022) and number of treated metastases (p = 0.007) were significant for PFS. About 80% of patients continued the ongoing systemic therapy 1- and 2-years after SABR with no grade 3 or 4 toxicities.

Conclusions

we confirmed the efficacy and safety of SABR for oligoprogression from RCC, with the potential to ablate resistant metastases and to prolong the ongoing systemic therapy.

Keywords: Oligometastatic, SBRT, SABR, Stereotactic radiotherapy, Oligometastases, Kidney cancer, Radiosurgery, Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, Renal cancer

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents 80–90% of all kidney tumors (Motzer et al. 2014; Woodward et al. 2011) and 3–5% of all adult cancers (Bray et al. 2018). Surgical resection is the main approach for localized kidney disease, but about 15–25% of patients will develop distant metastases after primary treatment (Kim et al. 2011). Although systemic therapy represents the standard of care for metastatic patients, the role of metastases-directed treatments has been investigated in the last decades. Metastasectomy seems to be beneficial in terms of patients’ survival (Vogl et al. 2006; Seitlinger et al. 2021) but not always feasible due to patient’s or disease’s characteristics. Radiotherapy delivered with ablative intent is able to overcome the typical RCC radioresistance and thus it appears to be a valid alternative to more invasive approaches (Ning et al. 1997; de Meerleer et al. 2014). Zaorsky et al. (2019) published a meta-analysis of 28 studies investigating the efficacy of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) in oligometastatic RCC. The summary effect size for 1-year local control (LC) was 89.1% for extracranial and 90.1% for intracranial metastases, respectively. Moreover, SABR appeared to be safe with an incidence of any grade 3 and 4 toxicity of only 0.7% for extracranial disease and 1.1% for intracranial disease. Ablative metastases-directed radiotherapy may play a relevant role in the oligoprogressive setting, defined as the progression of few isolated metastatic sites during an ongoing systemic therapy on a background of otherwise stable disease (Guckenberger et al. 2020). Ablation of oligoprogressive metastases has the potential to control metastatic foci become resistant to the ongoing drug and to delay the switch or the intensification of the systemic treatments. Aim of the present study was to analyze the outcome in terms of control of disease, survival, and toxicity of a group of patients treated with SABR on cranial and extracranial oligoprogressive metastases from RCC.

Materials and methods

Study population

With this monocenter study, we analyzed patients affected by RCC treated with SABR on oligoprogressive sites of disease during systemic treatment. A maximum of 5 sites of oligoprogression in up to 2 organs was allowed. All cases were presented to and approved by the multidisciplinary oncologic team of our Institution. Indication to treat sites of oligoprogression was generally reserved for patients unfit for the intensification or switch of systemic treatment or affected by an indolent disease characterized by a long disease-free interval (DFI). The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and local regulations.

Techniques of radiotherapy

For treatment planning, the clinical target volume (CTV) was equal to the gross tumor volume (GTV) and was delineated on simulation CT imaging, co-registered with an MRI scan when available. In the case of disease located in an organ subject to internal movement such as lung, patients were simulated with a 4D CT scan. All patients were positioned supine and immobilized with a thermoplastic mask, including brain, thorax and abdomen sites. An isotropic margin of 5–10 mm was added to CTV to obtain the planning target volume (PTV). For brain metastases, the CTV corresponded to the GTV and included the post-contrast enhancing tumor on T1-MRI. The PTV was generated by adding an isotropic margin of 2 mm from CTV. All patients were treated with the volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) technique. Patient’s position was evaluated daily with cone-beam CT imaging before each treatment session. Biological effective dose (BED) was calculated with an α/β of 10 to compare different schedules of radiotherapy, with the following calculation according to the linear quadratic model:

For daily systemic agents, the concomitant treatment was interrupted during the days of SABR delivery (1 − 6 days), including 3 days before and after radiation treatment, independently from the body site. For agents with 2 or 3 weekly administrations, SABR was delivered during the drug-free window. All the concomitant treatments were taken at full dose.

Response assessment

Clinical and radiological evaluation with thorax-abdomen CT scan was performed every 3 months after SABR for the first year. For patients treated on brain or liver metastases, an MRI scan was added to the standard radiological imaging to better evaluate treatment response. Tumor response was classified according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours (EORTC-RECIST) criteria version 1.16.

Statistical analysis

Endpoints of the present study were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). The OS was calculated from SABR to death from any cause or last follow-up. The PFS was defined as the time from radiotherapy treatment to in-field or out-field progression, or death from any cause.

Univariate analysis was performed with the log-rank test, and Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for the included potential risk factors. Variables with a p value ≤ 0.05 at univariate test were selected for the multivariable Cox regression analysis performed to evaluate the association between clinical factors and survival. Statistical calculations were performed using STATA, version 15.

Results

We included a total of 74 oligoprogressive metastases and 57 SABR treatments delivered to 44 patients (Table 1). Majority of patients (33, 75%) was male, with an ECOG performance status (PS) of 0 (23, 52.2%). Median age at the time of diagnosis of kidney primary tumor was 63.4 (29.8–84.7) years. All the included patients were affected by RCC, and all except one were treated with a previous nephrectomy. Median DFI, defined as the time between primary tumor diagnosis and first appearance of metastases, was 21.8 (0–237.3) months. One line of systemic therapy was administered before SABR in 45 (78.9%) cases and bone disease was present in 22 (38.6%) cases. A total of 26 (35.1%) lesions were intracranial, and 48 (64.9%) metastases were extracranial. Most common sites of body metastases were lung (21, 28.3%), bone (10, 13.5%), and liver (6, 8.1%). The median value of the maximum diameter of lesions was 19.5 (5–80) mm. Most common concomitant treatments were sunitinib (28, 49.1%), pazopanib (12, 21.0%) and nivolumab (11, 19.3%). Thirty-three (75%) patients received a single course of SABR, while 11 (25%) patients received ≥ 2 SABR courses on further oligoprogressions. Median SABR dose was 40 Gy (16–60), delivered in 1–6 fractions. Median BED was 81.6 Gy (28.8–160.5). Most common schedules of dose were: 24 Gy in single fractions (18 brain metastases), 48 Gy in 4 fractions (14 lung metastases), and 45 Gy in 6 fractions (8 metastases, including liver, lymph node, pancreas, adrenal gland).

Table 1.

Patients’ and disease’s characteristics

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | 44 | |

| Treatments | 57 | |

| Lesions | 74 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 33 | 75.0 |

| Female | 11 | 25.0 |

| Performance status ECOG | ||

| 0 | 23 | 52.2 |

| 1 | 16 | 36.4 |

| 2 | 5 | |

| Age (years), median (range) | 63.4 (29.8—84.7) | |

| Disease-free interval, median (range) | 21.8 (0—237.3) | |

| Number of sistemic lines before SBRT | ||

| 1 | 38 | 66.7 |

| 2 | 12 | 21.0 |

| ≥ 3 | 7 | 13.3 |

| Presence of bone disease at time of Tx | 22 | 38.6 |

| Number of treated metastases | ||

| 1 | 45 | 78.9 |

| 2 | 7 | 12.3 |

| 3 | 4 | 7.0 |

| 4 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Site of metastases | ||

| Brain | 26 | 35.1 |

| Lung | 21 | 28.3 |

| Bone | 10 | 13.5 |

| Liver | 6 | 8.1 |

| Lymph node | 5 | 6.7 |

| Adrenal gland | 4 | 5.4 |

| Pancreas | 1 | 1.3 |

| Muscle | 1 | 1.3 |

| Lesion diameter mm, median (range) | 19.5 (5–80) | |

| Type of systemic drug during SBRT | ||

| Sunitinib | 28 | 49.1 |

| Pazopanib | 12 | 21.0 |

| Nivolumab | 11 | 19.3 |

| Other | 6 | 10.6 |

| Total dose, median (range) Gy | 40 (16–60) | |

| Number of fractions, median (range) | 4 (1–6) | |

| BED, median (range), Gy | 81.6 (28.8–160.53) | |

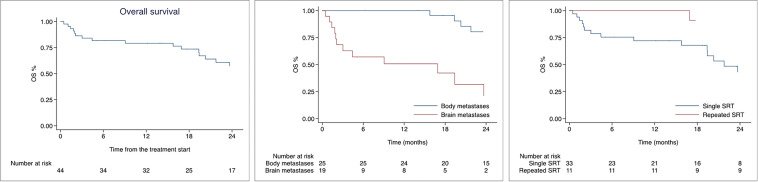

Median follow-up was 19.0 months (0.5–100.2). Median OS was 36.3 months with 1- and 2-year OS rates of 79.2% (95% CI 63.8–88.6), and 57.3% 95% CI 39.5–71.7) as shown in Fig. 1. In univariate analysis, patients treated on brain metastases had worse survival compared to patients treated on body lesions (HR 3.26, 95% CI 1.00–10.56; p = 0.049) as shown in Table 2. Moreover, the increasing number of metastatic organs was associated with worse OS (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.09–2.25; p = 0.013). On the contrary, repeated SABR on subsequent oligoprogressions was associated with improved OS (HR 0.19, 95% CI 0.05–0.66; p = 0.009). In multivariable analysis only repeated SABR remained significant with an improvement in patients’ survival (HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.12–0.91; p = 0.034). Median OS for the whole population was 36.3 months, 49.3 months and 16.9 months after extracranial and intracranial SABR, respectively. For patients treated with one course of SABR median OS was 21.7 months versus 90.5 months of patients treated with repeated SABR. Figure 1 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for OS of the whole population, according to the site of treated metastases and number of treatments.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for Overall survival of the whole population, according to site of metastases and number of radiotherapy courses

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for overall survival and progression-free survival.

| OS | PFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.97–1.05 | 0.457 | 1.02 | 0.98–1.05 | 0.203 |

| Gender | 0.76 | 0.29–1.97 | 0.586 | 1.47 | 0.65–3.33 | 0.351 |

| Disease free interval | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.239 | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | 0.036 |

| Bone disease | 1.53 | 0.67–3.49 | 0.312 | 1.11 | 0.59–2.08 | 0.739 |

| Liver SBRT | 2.12 | 0.27–16.25 | 0.468 | 1.18 | 0.41–3.34 | 0.750 |

| Nodal SBRT | 1.07 | 0.24–4.63 | 0.922 | 0.63 | 0.15–2.66 | 0.538 |

| Brain SRT | 4.04 | 1.68–9.67 | 0.002 | 1.64 | 0.86–3.12 | 0.130 |

| N. metastatic organs | 1.57 | 1.09–2.25 | 0.013 | 1.04 | 0.78–1.38 | 0.780 |

| Number treated mets | 0.87 | 0.43–1.76 | 0.707 | 1.67 | 1.10–2.55 | 0.016 |

| Dimension mets | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.443 | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.338 |

| Lines systemic therapy | 1.42 | 0.82–2.44 | 0.200 | 1.10 | 0.74–1.64 | 0.608 |

| BED | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.374 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.713 |

| Repeated radiotherapy | 0.19 | 0.05–0.66 | 0.009 | – | – | – |

| Multivariable analysis | ||||||

| Brain SRT | 2.60 | 0.83–8.18 | 0.100 | – | – | – |

| N. metastatic organs | 1.18 | 0.74–1.89 | 0.475 | – | – | – |

| Disease free interval | – | – | – | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | 0.022 |

| Number treated mets | – | – | – | 1.81 | 1.17–2.79 | 0.007 |

| Repeated radiotherapy | 0.22 | 0.06–0.77 | 0.018 | – | – | – |

In bold the risk factors with p value <= 0.005

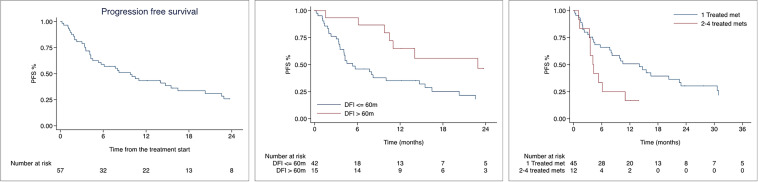

Median PFS was 9.8 months, and PFS rates at 1 and 2 years were 43.2% (95% CI 29.8–55.9) and 25.8% (95% CI 14.2–39.1) as shown in Fig. 2. At univariate analysis, DFI (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–0.99, p = 0.036) and number of treated metastases (HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.10–2.55, 0.016) were significantly associated with PFS. At multivariable analysis, both DFI (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–0.99; p = 0.022) and number of treated metastases (HR 1.81, 95% CI 1.17–2.79; p = 0.007) remained significant. Nevertheless, the median PFS for DFI ≤ 60 months was 5.3 months, versus 22.9 months for patients with DFI > 60 months. Moreover, median PFS was 14.0 months for patients treated on 1 metastasis, versus 4.1 months for patients treated on 2–4 metastases. Median time to the onset of the next systemic therapy was not reached, and 79.3% patients continued the ongoing line of systemic therapy 1 and 2 years after SABR. Systemic treatment was intensified or switched after 18 (31.6%) treatments in 13 (29.5%) patients.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for Progression free survival of the whole population, according to the site and number of treated metastases

We observed only two (2.70%) local failures after SABR, both related to two bone metastases, treated with 18 Gy in a single fraction and 30 Gy in 5 fractions. Both patients with local failure were receiving concomitant sunitinib, one with 3 previous lines of systemic therapy. No significant correlations between the risk factors, including BED, and the risk of local failure were observed.

In terms of acute toxicity, a mild pattern was observed with 1 (1.7%) patient reporting grade 2 dyspnea for lung SABR, and 1 (1.7%) patient with gastrointestinal grade 2 side effect for irradiation on pancreatic metastasis, both treatments were delivered during concomitant sunitinib. In the late setting, 5 (8.8%) patients were diagnosed with grade 2 radionecrosis after brain radiosurgery, in treatment with sunitinib (2 patients, 3.5%), nivolumab (2 patients, 3.5%) and everolimus (1 patient, 1.7%). No grade 3 or 4 side effects were observed both in the acute and late setting.

Discussion

With the present paper, we demonstrated the efficacy and safety of SABR in oligoprogressive RCC, with about 80% of patients continuing their ongoing systemic therapy two years after this local ablative treatment. In recent years, a large number of paper has been published on metastatic RCC treated with SABR, the majority focusing on oligorecurrent or mixed oligometastatic cases (Wersall et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2021; Marvaso et al. 2021; Franzese et al. 2019, 2021, 2022a).

In the case of isolated progression under systemic therapy, metastatic kidney cancer patients have been historically treated with further lines of immunotherapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) regardless of the pattern of progression, with, however, poor and unsatisfying results. The evidence about the use of local ablative treatment on oligoprogression is increasing for different primary tumors and in particular for prostate cancer (Yaney et al. 2022; Franzese et al. 2022b; Pezzulla et al. 2021; Onal et al. 2021; Deek et al. 2021; Berghen et al. 2021). However, the literature on oligoprogressive RCC is still scarce, but growing with the publication of some retrospective papers (Santini et al. 2017; Schoenhals et al. 2019; De et al. 2022) and few prospective trials (Hannan et al. 2022; Cheung et al. 2021).

In the study published by Schoenhals et al. (2021), 36 patients were treated with SABR on 43 oligoprogressive metastases with a median dose of 36 Gy in 3 fractions. The 1-year LC rate was 93% and patients receiving SABR while on immunotherapy exhibited a longer median PFS than patients not on immunotherapy (> 28.4 vs 9.2 months, p = 0.0001). Meyer et al. (2018) conducted a multicenter retrospective study of 180 patients with metastatic RCC, including 101 patients treated with SABR for oligoprogressive disease. The median local recurrence-free survival, PFS, time to systemic therapy, and OS were 19.3, 8.6, 10.5, and 23.2 months, respectively. Hannan et al. (2022) conducted a phase II trial of SABR on oligoprogressive kidney cancer with the primary objective to extend ongoing systemic therapy by > 6 months in > 40% of patients. Twenty patients were enrolled, the local control rate was 100%, and at a median follow-up of 10.4 months, SABR extended the duration of the ongoing systemic therapy by > 6 months in 70% of patients. Indeed, SABR is capable to ablate any isolated foci of metastatic disease become resistant to an ongoing systemic therapy, and has the peculiarity of being able to be repeated several times in the patient's clinical course without significant side effects. In our analysis, 19 patients (34.3%) received 2 or more courses of SABR for further oligoprogressions, and the repeated treatment was associated with a benefit in terms of survival. Median OS was 90.5 months for patients who received multiple SABR courses versus 21.7 months for patients treated with a single SABR (p = 0.034).

The risk of further metastatic progression after ablative radiotherapy still remains a critical point to be explored. So far, few risk factors have been recognized to be predictive of out-field progression thus improving the identification of patients with a more indolent disease. In our study, we identified DFI and the number of metastases as independent predictive factors for PFS. Indeed, the longest median PFS was achieved in patients with a DFI longer than 60 months (22.9 vs 5.3 months) and treated on one single metastases (14.0 vs 4.1 months). Santini et al. (2017) published the results of 55 oligoprogressive kidney cancer patients treated with locoregional treatment in the form of radiotherapy (45.5%), surgery (45.5%) and thermal ablation (9.1%). The authors found that Fuhrman grade (p = 0.021), MSKCC risk score (p = 0.036) and first site of progression (p = 0.045) were significantly correlated with the risk of death after locoregional treatments but no risk factor was predictive for further progression. A large multicenter study including both oligorecurrent and oligoprogressive disease (Franzese et al. 2021) showed for these latter a significant reduction of PFS rates at the increase of the number of treated metastases (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.11–1.59; p = 0.002), and also a positive role of the radiation dose in terms of BED (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–0.99; p = 0.033). This result highlights the importance of the radiotherapy aim in this setting, that should ablative rather than palliative. Actually, as previously demonstrated (Hong et al. 2015), tumors are often characterized by an intrinsic heterogeneity and its subclonal diversity can change during progression. In fact, in some cases metastatic cells can colonize the surgical bed, or give rise to new further metastases. Thus, an effective radiation treatment with ablative doses (commonly defined as an equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions > 50 Gy) may be able to interrupt the metastatic cascade and prevent the appearance of new metastases, often characterized by an intrinsic resistance to the ongoing treatments.

Ablation with SABR may be achieved without the onset of severe toxicity. In our study, we didn’t observe any grade 3 or 4 side effect from the association of SABR with concomitant systemic therapy. Majority of patients reported grade 1 and 2 toxicities, above all during concomitant sunitinib. These results are in line with other published studies. In the prospective study of Hannan et al. (2022) only 1 case of grade 3 toxicity was reported in the form of small intestinal perforation for an abdominal/peritoneal SABR with concurrent everolimus and lenvatinib; more common was the incidence of grade 1 fatigue, nausea and vomiting. According to Schoenhals et al. (2021), 36% of treated patients had documented toxicity related to SABR and/or systemic therapy with no grade 3 or 4 side effects. He et al. (2020) used SABR during TKI in 56 patients and reported grade 3 toxicity in only four (7%) patients, with 60% represented by grade 3 anemia. Among the patients with grade 3 toxicity, half were treated concurrently with axitinib, and the others received concurrent sunitinib. Even less impacting seems to be the association of radiotherapy with immunotherapy as shown by the systematic review and meta-analysis recently conducted by Sha et al. (2020). After the evaluation of 51 studies, the authors showed comparable grade 3 and 4 toxicity in using immunotherapy plus radiotherapy compared to immunotherapy alone. Prospective ongoing studies are evaluating the role of SABR in the oligoprogressive setting of kidney cancer (e.g. NCT04299646, NCT02855203, NCT04090710), to better clarify the benefit and the safety of the association of radiotherapy with the most modern systemic therapies. We acknowledge the limitations of this study that include the retrospective nature, the small number of patients, and the heterogeneity of the treatments; however, we believe that our experience can enforce the promising results of the published literature.

Conclusions

With the present study, we confirmed the efficacy of SABR for oligoprogression from RCC, with the potential to ablate resistant metastases and to prolong the ongoing systemic therapy. The association of SABR with TKI or immunotherapy seems to be safe without severe toxicities, and with a major benefit in patients with long DFI and limited oligoprogressive site. Prospective trials are necessary to improve patients’ selection and to optimize the combination strategies.

Author contributions

CF: study design and writing, BM: data collection, DB: manuscript writing, MB: data collection, PN: manuscript writing, LB: data collection, DF: manuscript writing, TC: manuscript editing, EC: manuscript editing, MAT: data collection, MM: data collection, LC: data collection, LLF: data collection, ST: data analysis, MS: supervisor.

Funding

No fundings were used for the present study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Berghen C et al (2021) Progression-directed therapy for oligoprogression in castration-refractory prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 4:305–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F et al (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P et al (2021) Stereotactic radiotherapy for oligoprogression in metastatic renal cell cancer patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy: a phase 2 prospective multicenter study. Eur Urol 80:693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De B et al (2022) Definitive radiotherapy for extracranial oligoprogressive metastatic renal cell carcinoma as a strategy to defer systemic therapy escalation. BJU Int 129:610–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Meerleer G et al (2014) Radiotherapy for renal-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol 15:e170–e177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deek MP et al (2021) Metastasis-directed therapy prolongs efficacy of systemic therapy and improves clinical outcomes in oligoprogressive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 4:447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese C et al (2019) Role of stereotactic body radiation therapy for the management of oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 201:70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese C et al (2021) The role of stereotactic body radiation therapy and its integration with systemic therapies in metastatic kidney cancer: a multicenter study on behalf of the AIRO (Italian Association of Radiotherapy and Clinical Oncology) genitourinary study group. Clin Exp Metastasis 38:527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese C et al (2022a) Risk-group classification by recursive partitioning analysis of patients affected by oligometastatic renal cancer treated with stereotactic radiotherapy. Clin Oncol 34:379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese C et al (2022b) Oligoprogressive castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with metastases-directed stereotactic body radiation therapy: predictive factors for patients’ selection. Clin Exp Metastasis 39:449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guckenberger M et al (2020) Characterisation and classification of oligometastatic disease: a European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendation. Lancet Oncol 21:e18–e28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan R et al (2022) Phase II trial of stereotactic ablative radiation for oligoprogressive metastatic kidney cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 5:216–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L et al (2020) Survival outcomes after adding stereotactic body radiotherapy to metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Oncol 43:58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong MKH et al (2015) Tracking the origins and drivers of subclonal metastatic expansion in prostate cancer. Nat Commun 6:6605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SP et al (2011) Outcomes and clinicopathologic variables associated with late recurrence after nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma. Urology 78:1101–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvaso G et al (2021) Oligo metastatic renal cell carcinoma: stereotactic body radiation therapy, if, when and how? Clin Transl Oncol. 10.1007/s12094-021-02574-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer E et al (2018) Stereotactic radiation therapy in the strategy of treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a study of the Getug group. Eur J Cancer 98:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ et al (2014) Kidney cancer, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 12:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning S, Trisler K, Wessels BW, Knox SJ (1997) Radiobiologic studies of radioimmunotherapy and external beam radiotherapy in vitro and in vivo in human renal cell carcinoma xenografts. Cancer 80:2519–2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onal C et al (2021) Stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligoprogressive lesions in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients during abiraterone/enzalutamide treatment. Prostate 81:543–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzulla D et al (2021) Stereotactic body radiotherapy to lymph nodes in oligoprogressive castration-resistant prostate cancer patients: a post hoc analysis from two phase I clinical trials. Clin Exp Metastasis 38:519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini D et al (2017) Outcome of oligoprogressing metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with locoregional therapy: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Oncotarget 8:100708–100716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhals J et al (2019) Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for oligoprogressive metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 105:E257 [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhals JE et al (2021) Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for oligoprogressive renal cell carcinoma. Adv Radiat Oncol 6:100692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitlinger J, Prieto M, Siat J, Renaud S (2021) Pulmonary metastasectomy in renal cell carcinoma: a mainstay of multidisciplinary treatment. J Thorac Dis 13:2636–2642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha CM et al (2020) Toxicity in combination immune checkpoint inhibitor and radiation therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol 151:141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C et al (2021) Definitive radiotherapy in lieu of systemic therapy for oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma: a single-arm, single-centre, feasibility, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00528-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl UM et al (2006) Prognostic factors in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: metastasectomy as independent prognostic variable. Br J Cancer 95:691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersall PJ et al (2005) Extracranial stereotactic radiotherapy for primary and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 77:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward E et al (2011) Skeletal complications and survival in renal cancer patients with bone metastases. Bone 48:160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaney A et al (2022) Radiotherapy in oligometastatic, oligorecurrent and oligoprogressive prostate cancer: a mini-review. Front Oncol. 10.3389/fonc.2022.932637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaorsky NG, Lehrer EJ, Kothari G, Louie AV, Siva S (2019) Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma (SABR ORCA): a meta-analysis of 28 studies. Eur Urol Oncol 2:515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y et al (2019) Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy (SAbR) used to defer systemic therapy in oligometastatic renal cell cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 105:367–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]