Abstract

Purpose

In an oncological set up the role of frozen section biopsy is undeniable. They serve as an important tool for surgeon’s intraoperative decision making but the diagnostic reliability of intraoperative frozen section may vary from institute to institute. The surgeon should be well aware of the accuracy of the frozen section reports in their setup to enable them to take decisions based on the report. This is why we had conducted a retrospective study at Dr B. Borooah Cancer Institute, Guwahati, Assam, India to find out our institutional frozen section accuracy.

Methods

The study was conducted from 1st January 2017 to 31st December 2022 (5 years). All gynaecology oncology patients who were operated on during the study period and had an intraoperative frozen section done were included in the study. Patients who had incomplete final histopathological report (HPR) or no final HPR were excluded from the study. Frozen section and final histopathology report were compared and analysed and discordant cases were analysed based on the degree of discordancy.

Results

For benign ovarian disease, the IFS accuracy, sensitivity and specificity are 96.7%, 100% and 93%, respectively. For borderline ovarian disease the IFS accuracy, sensitivity and specificity are 96.7%, 80% and 97.6%, respectively. For malignant ovarian disease the IFS accuracy, sensitivity and specificity are 95.4%, 89.1% and 100%, respectively. Sampling error was the most common cause of discordancy.

Conclusion

Intraoperative frozen section may not have 100% diagnostic accuracy but still it is the running horse of our oncological institute.

Keywords: Intraoperative frozen section, Histopathological report, Sensitivity, Specificity

Introduction

The practical importance of intraoperative frozen section is well known in any surgical setup, especially in cancer speciality hospitals. Specimens from the gynaecologic organs account for a major chunk of specimens sent for intraoperative frozen section (IFS) analysis with the vast majority being ovarian masses. Ovarian cancer presents in women of various age strata including the reproductive age group in whom the incidence of malignant tumours is as high as 20% (Shen et al. 2021). This is of paramount importance considering the need for fertility preservation and the extent of surgery.

The gold standard for diagnosing a malignant tumour is the histo-pathological report (HPR). A variety of markers and investigations are used pre-operatively to predict the malignant nature of an adnexal mass which include tumour markers Cancer Antigen 125 (CA 125), Human epididymis 4 (HE 4), carcinoembryonic antigen CEA, Alfa feto-protein (AFP), CA 19-9, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (BHCG) levels and a combination of ultrasound, CA 125 and menopausal status, i.e. Risk of malignancy index (RMI score) (Al-Musalhi et al. 2015), risk of malignancy algorithm (ROMA) and use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Ledermann et al. 2013). However, most of these methods have not shown good accuracy in the pre-operative detection of malignancy.

Intraoperative frozen section (IFS) finds its place as an important diagnostic tool in this regard wherein a representative tissue is analysed, thus providing a preliminary diagnosis based on which the operating surgeon plans the extent of the surgery. IFS is also used in hysterectomy specimens to evaluate the endometrium for malignancy, in radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer to evaluate the nature of suspicious nodes and in vulval cancer to assess the margin status.

This study aims to determine the accuracy of diagnosis rendered on intraoperative frozen section (IFS) compared to the final diagnosis provided on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections. We analysed possible sources of discrepancy and the further management of such discordant cases. This enabled us to detect the pitfalls of IFS thereby serving as an internal audit to improve our health care.

Material and methods

Aim of study

Primary objective

To estimate the degree of accuracy of diagnosis rendered on intraoperative frozen sections (IFS) compared to final diagnosis provided on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded histopathological tissue sections (FFPE-HPR) in gynaecological cancers with emphasis on ovarian masses in a tertiary cancer care institute.

-

2.Secondary objectives

-

A.To analyse the source of discrepancies with special emphasis on cases where a change in patient management had to be made.

-

B.To study the further management of discordant cases.

-

A.

Inclusion criteria

All gynaecology oncology patients who were operated on during the study period and had an intraoperative frozen section done.

Exclusion criteria

All cases where a frozen section was done and final histopathology reports were incomplete or unavailable.

Study design

It is a retrospective observational study.

Study period

1st January 2017 to 31st December 2022 (5 years).

Site

Department of Gynaecology Oncology and Oncopathology, Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah Cancer Centre, Guwahati, Assam.

Prior medical reports of Gynaecology Oncology patients who have been operated on between 1st January 2017and 31st December 2022 in the institute and had an intraoperative frozen section done had been analysed.

Statistical methods

It is a descriptive study. All data analysis had been performed on computer using SPSS version 23. The descriptive statistics will be analysed as percentages and bar diagrams will be used. The results were compared to permanent sections to evaluate accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values and negative predictive value of frozen section.

The procedure of frozen section

The specimen for frozen section analysis was sent to the Oncopathology lab soon after removal in the operation theatre with normal saline and relevant clinical details. An immediate gross examination was done by our pathologists recording the size, volume and intactness/breach of the capsule. After gross examination, sections were obtained from representative areas at the discretion of the pathologist. A minimum of two sections and as many as six sections were taken depending upon the size or type of tumour. Sections of 4–6 microns were cut using Cryostat microtome (Leica CM1850) at temperatures − 22 to − 24 °C and using tissue freezing media from Leica. The sections were then stained by rapid haematoxylin and eosin stain. The average overall time for the procedure was 20 min which includes grossing and processing of 5–10 min and reporting which is of 8–10 min depending upon the number of sections and the nature of the specimen. The frozen sections were reported by trained senior pathologists and the report was communicated to the surgeon directly over the phone and entries were made into the frozen section register. The remaining tissue as well as original sections taken during IFS were then submitted for final formalin-based fixation and tissue processing.

We retrieved the data from archives of the Oncopathology Department frozen section register and electronic medical records from 1st January 2017 to 31st December 2022 which included FFPE-HPR reports as well as other clinical and demographical details of the cases included in the study. IFS and FFPE-HPR concordance data were recorded in tabular manner. Any discrepancy/discordancy between IFS and FFPE HPR reports was noted down.

We further divided discordancy into major and minor errors. Major discordancy referred to those cases where discordant results led to major differences in patient management in terms of the extent of radicality of surgery. Minor discordancy referred to those cases where the change was more of pathological significance rather than a change in the intraoperative management. In major discordant cases, the records were reviewed to analyse further management. The reasons for such discordancy were also reviewed.

Ethical clearance from the institutional review board had been obtained.

Results

The study included a total of 334 cases which included 307 ovarian masses to ascertain the nature of the tissue, s cervical cancers to assess suspicious lymph nodes, 15 vulval cancers for assessing surgical margin status and evaluation of nodes and 5 uterine cancers to assess the nature of endometrial tissue. Figure 1 shows the overall distribution of cases. The overall sensitivity of 91% and 100% specificity was recorded for IFS diagnosis overall.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of cases. A total of 17 major discordant cases had been reported all of which have been recorded in ovarian mass. The 27 other site cancers had 100% concordant reports

As there was 100% concordance in the evaluation of other gynaecological malignancies detailed analysis of IFS in ovarian mass was studied.

Table 1 shows the comparison of IFS and FFPE-HPR diagnoses with respect to ovarian masses. There were 276 (89.9%)concordant cases and 31 discordant cases(10.1%)of which 17 cases were major discordant(54.8%) and 14 cases were minor discordant(45.2%). All major discordancies were underdiagnosed cases which included seven benign cases and seven borderline cases which were later diagnosed to be malignant on FFPE-HPR.

Table 1.

Comparison of IFS and FFPE-HPR for ovarian cases (N = 307)

| Benign on final HPE | Borderline on final HPE | Malignant on final HPE | Concordancy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign on IFS | 163 (concordant) | 3 | 7 | 94.2 |

| Borderline on IFS | 0 | 12 (concordant) | 7 | 63.1 |

| Malignant on IFS | 0 | 0 | 115 (concordant) | 100 |

IFS intraoperative frozen section, FFPE-HPR formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded histopathological tissue sections

Table 2 and Fig. 2 show the diagnostic values of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of benign, borderline, malignant and combined borderline and malignant cases in IFS.

Table 2.

Diagnostic value of IFS for benign, borderline and malignant ovarian lesions N = 307

| Diagnostic value % (95% CI) | Benign | Borderline | Malignant | Borderline and Malignant combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 96.7% (94–98.4) | 96.7% (94–98.4) | 95.4% (92.4–97.4) | 96.7% (94–98.4) |

| Sensitivity | 100% (97.7–100) | 80% (51.9–95.6) | 89.1% (82.4–93.9) | 93% (87.6–96.6) |

| Specificity | 93% (87.6–96.6) | 97.6% (95.1–99) | 100% (97.9–100) | 100% (97.7–100) |

| Positive predictive value | 94.2% (89.9–96.7) | 63.1% (54.1–78.8) | 100% | 100% |

| Negative predictive value | 100% | 98.9% (97.1–99.6) | 92.7% (88.5–95.4) | 94.2% (89.9–96.7) |

IFS intraoperative frozen section

Fig. 2.

Bar diagram showing the diagnostic value of IFS for benign, borderline and malignant ovarian lesions

For benign ovarian disease, the IFS accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value are 96.7%, 100%, 93%, 94.2% and 100% respectively. For borderline ovarian disease the IFS accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value are 96.7%, 80%, 97.6%, 63.1% and 98.9%, respectively. For malignant ovarian disease the IFS accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value are 95.4%, 89.1%, 100%, 100% and 92.7%, respectively. When both borderline and malignant disease are clubbed together the IFS accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value is 96.7%, 93%, 100%, 100% and 94.2%, respectively.

Tables 3, 4 and 5 shows the cases where major discordancy has been observed. There were no overdiagnosed cases. The 17 underdiagnosed cases have been further divided into 3 categories which include upstaging of a. Benign to borderline b. Benign to Malignant c. Borderline to malignant. Ten cases were planned for adjuvant chemotherapy; however, two patients defaulted chemotherapy. Two patients underwent completion surgery after chemotherapy.

Table 3.

Major discordancy between IFS and FFPE-HPR (benign to borderline) (1.7%)

| S. no. | Age | IFS | HPE | Surgery done | Size of the lesion and Reason for discordancy | Management of discordant cases | Resurgery done |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 24 | Mucinous cystadenoma | Borderline mucinous | LSO Omental nodule excision | 12 cm (1, 2) | Observation | No |

| 2. | 37 | Mucinous cystadenoma | Borderline mucinous with micro invasion | TAH BSO ICO PLND PALNDa | 30 cm (1, 2) | Observation | No |

| 3. | 47 | Mucinous cystadenoma | Borderline with micro invasion | TAH BSO Omentectomy | 15 cm (1, 2) | Observation | No |

IFS intraoperative frozen section, HPR final histopathology report, LSO left salphingo-oophorectomy, TAH total abdominal hysterectomy, BSO bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy, ICO infracolic omentectomy, PLND pelvic lymphadenectomy, PALND paraaortic lymphadenectomy P-parity. Index of discordancy: 1 sampling error, 2 technical error

aIn view of large size of tumour and the refusal of patient to undergo a second surgery an extensive surgery which included TAH BSO ICO PLND PALND was performed

Table 4.

Major discordancy between IFS and FFPE-HPR (benign to malignant) (4%)

| S. no. | Age | IFS | HPE | Surgery done | Size of the lesion and reason for discordancy | Management of discordant cases | Resurgery done |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 30 | Mucinous cystadenoma | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | TAH BSO ICOa | 37 cm (1) | Adjuvant chemotherapy(defaulted) | No |

| 2. | 46 | Benign serous cystadenoma | High-grade serous carcinoma | TAH BSO | 15 cm (1, 3) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

| 3. | 47 | Endometriosis | Clear cell carcinoma | TAH BSO SCOb | 12 cm (3, 4) | Adjuvant chemotherapy(defaulted) | No |

| 4. | 62 | Benign serous cystadenoma | High-grade serous carcinoma | TAH BSO SCO PLNDc | 14 cm (1, 2) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

| 5. | 30 | Sertoli Leydig tumour | High-grade serous carcinoma | RSO ICO | 5 cm (3, 4, 5) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | TAH LSO SCO post chemotherapy |

| 6. | 32 | Mucinous cystadenoma | High-grade serous carcinoma | LSO SCOa | 12 cm (1, 3) | Observation | No |

| 7. | 22 | Mucinous cystadenoma | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | LSO ICO multiple biopsy | 26 cm (1, 2) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

IFS intraoperative frozen section, HPR final histopathology report, LSO left salphingo-oophorectomy, TAH total abdominal hysterectomy, BSO bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy, ICO infracolic omentectomy, SCo supracolic omentectomy, RSO right salphingo-oophorectomy, PLND pelvic lymphadenectomy, PALND paraaortic lymphadenectomy P-Parity

aIn view of large size of tumour, positive peritoneal cytology and refusal of patient to undergo surgery at a second sitting TAH BSO ICO was done

bIn view of long standing history of endometriosis in post-menopausal woman TAH BSO SCO was done

^In view of gross finding of solid cystic tumour with focal areas of surface papillary projections a thorough staging was undertaken. Index for discordancy: 1 sampling error (limited number of sections during IFS, 2 the technical difficulty in freezing tissues especially with high mucinous content, 3 frozen section artefacts, 4 inexperienced pathologist, 5 inherent nature of the disease with heterologous elements

Table 5.

Major discordancy between IFS and FFPE-HPR (borderline to malignant) (36%)

| S. no. | Age | IFS | HPE | Surgery done | Size of the lesion and Reason for discordancy | Management of discordant cases | Resurgery done |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 58 | Borderline mucinous | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | TAH BSO ICO | 15 cm (1, 2) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

| 2. | 47 | Borderline micropapillary serous | Low-grade serous papillary carcinoma | TAH BSO ICO | 8 cm (1, 5) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

| 3. | 69 | Borderline mucinous | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | TAH BSO ICO PLND | 30 cm (1, 2) | Observation | No |

| 4. | 50 | Borderline mucinous | Sero-mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | TAH BSO SCO | 30 cm (1) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

| 5. | 42 | Borderline mucinous | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | TAH BSO PLND | 10 cm (1, 2) | Observation | No |

| 6. | 58 | Borderline micropapillary pattern | Low-grade serous cystadenocarcinoma | TAH BSO SCO | 15 cm (1, 3) | Adjuvant chemotherapy | No |

| 7. | 39 | Borderline mucinous | High-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma | RSO SCO | 7 cm (1) | Observation | TAH LSO 4 years later |

Index for discordancy: 1 sampling error (limited number of sections during IFS, 2 the technical difficulty in freezing tissues especially with high mucinous content, 3 frozen section artefacts; inexperienced pathologist, 4 in experienced pathologist, 5 inherent nature of the disease with heterologous elements, 6 IHC requirements

IFS intraoperative frozen section, HPR final histopathology report, LSO left salphingo-oophorectomy, TAH total abdominal hysterectomy, BSO bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy, ICO infracolic omentectomy, SCo supracolic omentectomy, RSO right salphingo-oophorectomy, PLND pelvic lymphadenectomy, PALND paraaortic lymphadenectomy P-parity

Table 6 shows cases having minor discordancy where there was a difference between the IFS and FFPE-HPR but the discordancy did not affect the surgery planned. It includes both the following: a. cases where a benign cyst had a different type of final HPE diagnosis and b. cases where a malignant cyst had a different type on final HPE diagnosis.

Table 6.

Minor discordant cases

| S. no. | IFS | HPE | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Benign to benign | |||

| 1. | Benign cyst | Sex cord-stromal tumour | 1, 3 |

| 2. | Endometriotic cyst | Serous cystadenofibroma | 1 |

| 3. | Benign serous cystadenoma | Haemorrhagic cyst | 3, 4 |

| 4. | Fibrothecoma | Haemorrhagic cyst | 2, 3 |

| 5. | Benign serous cystadenoma | Haemorrhagic cyst | 3, 4 |

| 6. | Benign serous cystadenoma | Haemorrhagic cyst | 3, 4 |

| 7. | Benign serous cystadenoma | Corpus luteal cyst | 2, 3, 4 |

| 8. | Seromucinous cystadenoma | Endometriosis | 1, 3 |

| 9. | Seromucinous cystadenoma | Endometriotic cyst | 1, 3 |

| 10. | Mucinous tumour | Dermoid | 1, 2, 5 |

| (b) Malignant to malignant | |||

| 1. | Malignant Brenner | High-grade serous carcinoma | 1, 3, 4 |

| 2. | Clear cell carcinoma | Endometriod adenocarcinoma G1 | 1, 3 |

| 3. | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | GIST | 1, 6 |

| 4. | High-grade adenocarcinoma | Clear cell carcinoma | 1, 3 |

Index for discordancy: 1 sampling error(Limited number of sections during IFS), 2 the technical difficulty in freezing tissue with high mucinous content, 3 frozen section artefacts, 4 inexperienced technician, 5 inherent nature of the disease with heterologous elements, 6 IHC requirements

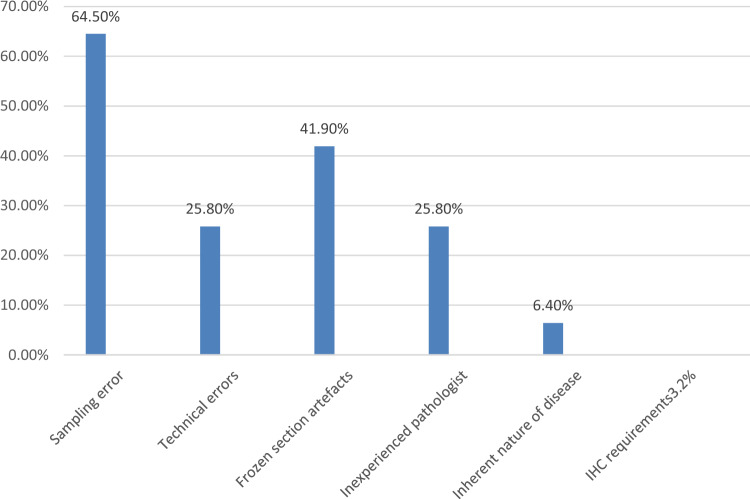

Figure 3 shows the causes of major and minor discordancy as discordant sources combined.

Fig. 3 .

Source of discordancy between IFS and FFPE-HPE

Discussion

Accurate classification of gynaecologic neoplasms, especially ovarian neoplasms as benign, borderline or invasive on frozen sections often is a real challenge in the practical world even for a well-trained pathologist. With the help of IFS diagnosis, the surgeon would have a provisional report of the nature of the specimen. This would translate into increased or decreased radicality of the surgery and advocate more aggressive follow-up of the patients diagnosed to have malignancy to ensure proper adherence to further follow-up visits in advanced disease or avoidance of chemotherapy/completion surgery in cases of well-differentiated stage 1A ovarian cancer disease(Maggioni et al. 2006). In addition to IFS application in ovarian neoplasms, it also finds its place in cervical and vulval carcinoma to see for lymph node metastasis and tumour margin analysis and assess prognostic markers in endometrial carcinoma (Scurry and Sumithran 1989). A study done by Swift et al. (2022) showed 97.2% PPV of IFS for lymph node assessment in vulval cancer. A similar study done by Santaro et al. (2019) showed 97.2% agreement for the evaluation of endometrium. A retrospective study done by Tanaka et al. (2020) showed 72% sensitivity in the evaluation of cervical cancer but this included the nature of mass as well. We found 100% concordance in our study for cervical, uterine and vulval cancer. This could be attributed to the lower number of cases in our study.

On analysis of IFS utility in ovarian masses, a recent systematic review by Meys et al. showed the average IFS sensitivity when borderline and malignant ovarian masses were clubbed together was 96.5% and specificity was 89.5% (Meys et al. 2017). In another study by Kung et al., the IFS sensitivity was 92.51% and the specificity was 100% (Kung et al. 2019). The sensitivity of IFS in other studies ranged between 73 and 98% (Cuello et al. 1999; Hamed et al. 1993; Buza 2019). In our study, the sensitivity and specificity of IFS for both borderline and malignant cases clubbed together were 93% and 100%, respectively. This implies while IFS can be criticized for underdiagnosing tumours resulting in a second surgery, it does not over-diagnose malignancy. The PPV in our study was 100% compared to a study by Kung et al. (2019) which showed PPV of 81.2% as we had also considered cases where the IFS diagnosis showed borderline with other features suggestive of malignancy as malignant cases in our analysis. This was proven to be a good decision as most of the patients had a malignant diagnosis on the final HPE. This cannot be taken as a discrepancy as considered in other studies as the surgeon would do a complete staging in these cases (Ureyen et al. 2014).

IFS demonstrates low performance in differentiating between borderline and malignant tumours. Various studies have shown the up gradation rate of borderline to malignant tumours was 20–25% (Medeiros et al. 2005; Ratnavelu et al. 2016). We found 63% upgradation of borderline tumours to malignant tumours. Five cases were mucinous in histology. This has been the largest source of discrepancy in gynaecology specimens as mucinous tumours are heterogeneous in nature (Medeiros et al. 2005; Tempfer et al. 2007). The mean size of mucinous tumours was 24.8 cm in a study by Subbian et al. (2013) while the average size of the tumours in our study was 17 cm. It is well known that the large size of mucinous tumours makes them pre-disposed to sampling errors. In a busy tertiary care centre, the logistic issue becomes a deterrent to ideal sectioning limits and it is impractical to do more than six frozen sections given the large size of the adnexal masses.

The accuracy of IFS is affected by various factors such as errors in sampling, technical errors and interpretation errors (Stewart et al. 2006). Heterogeneous tumours such as mucinous tumours and dermoid cysts are prone to sampling errors (Yoshida et al. 2021). In a study by Kung, the rate of sampling error was as high as 47% (Kung et al. 2019). We observed 64.5% of discordancy was due to sampling errors. It is important that proper sectioning of the cyst wall is done, especially if the ovarian tumour does not have solid areas. Proper orientation of the sample is also a key component during IFS as a properly oriented section can help to detect the infiltrative pattern better than the expansile variety in mucinous carcinomas which would have falsely been diagnosed as borderline in IFS (Baal et al. 2017). This could also explain the discordance reported in various studies of early ovarian cancer (Baal et al. 2017; Armstrong et al. 2021). In comparison to a study done by the College of American Pathologists which showed 40% interpretation error and 12.7% sectioning error (Bachner and Howanitz 1991), we found 25% of discordancy due to technical errors and 41% due to frozen section artefacts.

Serous and clear cell carcinoma are usually well identified on IFS compared to mucinous tumours (Kung et al. 2019). This is primarily due to the over-reliance of IFS on architectural pattern and cellular morphology making it difficult to pick up the correct diagnosis in mucinous tumours which are usually very large and have heterogeneous histology as described earlier.

A suggestion we would like to make is to have a peri-operative discussion between the operating surgeon, the pathologist and at times the medical oncologist along with the patient and her relatives. This is of paramount importance as the provision of relevant clinical details of the patient would enable the pathologist to give a better diagnosis. Another solution would be to prepare the frozen section slides in the operating room complex where the surgeons can provide their input thus leading to better sampling rates, especially in large tumours.

We observed 17 out of 307 cases (5%) to be underdiagnosed on IFS. Three cases were upstaged from benign to borderline and were observed. Of the remaining 14 patients four patients (28%) were observed whereas the remaining ten patients (72%) were given adjuvant chemotherapy. Completion surgery was done in 2 patients post-chemotherapy (20%). Patients with early-stage high-grade tumours were administered adjuvant chemotherapy. It worked in our favour that seven out of eight patients (87%) had a complete surgery upfront given their elderly age and completion of family. One patient refused further completion surgery as pre-operative imaging did not show any disease post-chemotherapy and only lymph nodes were to be removed. The upstaging of benign to malignant tumours was also seen in a study by Cross et al. (2012) who reported 19 similar cases and attributed interpretational error and sampling error to be the causative factors. It is always prudent to get a second opinion from another pathologist during a dicey report.

The main strength of the study is that of the heterogeneity of cases which gives an overall picture of a wide variety of cases an oncologist is bound to encounter. We also have explained the pitfalls of the pathology diagnosis and how to avoid it. The main drawback is being a retrospective study the possibility of review of the IFS slides is very much limited and since the pathologist was already aware of the IFS report, proper blinding could not be done.

There is something not found in literature called “surgeon gut feeling” which has helped a few of our patients where despite a diagnosis of benign/ borderline a complete surgery has been done due to the surgeon's clinical acumen and preoperative imaging of the patient. It is beneficial for patients to receive the provisional diagnosis based on IFS thus helping to counsel them for chemotherapy as the specificity was 100% in our study.

Conclusion

Frozen section despite its drawbacks still is the working horse of any oncology unit. It is up to the surgeon and pathologist as a team to correlate the clinical, radiological and intraoperative findings to keep the horse on track. Proper counselling of the patient is to be done to explain the pitfalls of such a procedure. We also encourage regular auditing of the IFS reports to improve the accuracy of reporting from time to time.

Author contributions

A, E and F main manuscript text B, C,D prepared figures and tables

Funding

The research had not received any grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest among the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Al-Musalhi K, Al-Kindi M, Ramadhan F, Al-Rawahi T, Al-Hatali K, Mula-Abed WA (2015) Validity of cancer antigen-125 (CA-125) and risk of malignancy index (RMI) in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Oman Med J 30(6):428–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A et al (2021) Ovarian cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw JNCCN 19(2):191–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachner P, Howanitz PJ (1991) Using Q-Probes to improve the quality of laboratory medicine: a quality improvement program of the College of American Pathologists. Qual Assur Health Care 3:167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buza N (2019) Frozen section diagnosis of ovarian epithelial tumors: diagnostic pearls and pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med 143(1):47–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross PA, Naik R, Patel A, Nayar AGN, Hemming JD, Williamson SLH et al (2012) Intra-operative frozen section analysis for suspected early-stage ovarian cancer: 11 years of Gateshead Cancer Centre experience. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 119(2):194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello M, Galleguillos G, Zárate C, Córdova M, Brañes J, Chuaqui R et al (1999) Frozen-section biopsy in ovarian neoplasm diagnosis: diagnostic correlation according to diameter and weight in tumors of epithelial origin. Rev Med Chil 127(10):1199–1205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamed F, Badía J, Chuaqui R, Wild R, Barrena N, Oyarzún E et al (1993) Role of frozen section biopsy in the diagnosis of adnexal neoplasms. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol 58(5):361–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung F, Tsang A, Yu E (2019) Intraoperative frozen section analysis of ovarian tumors: a 11-year review of accuracy with clinicopathological correlation in a Hong Kong Regional hospital. Int J Gynecol Cancer 29:ijgc–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, Sessa C et al (2013) Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 24 Suppl 6:vi24-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni A, Benedetti Panici P, Dell’Anna T, Landoni F, Lissoni A, Pellegrino A et al (2006) Randomised study of systematic lymphadenectomy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer macroscopically confined to the pelvis. Br J Cancer 95(6):699–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, Edelweiss MI, Stein AT, Bozzetti MC, Zelmanowicz A et al (2005) Accuracy of frozen-section analysis in the diagnosis of ovarian tumors: a systematic quantitative review. Int J Gynecol Cancer off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc 15(2):192–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meys EMJ, Jeelof LS, Achten NMJ, Slangen BFM, Lambrechts S, Kruitwagen RFPM et al (2017) Estimating risk of malignancy in adnexal masses: external validation of the ADNEX model and comparison with other frequently used ultrasound methods. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 49(6):784–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnavelu NDG, Brown AP, Mallett S, Scholten RJPM, Patel A, Founta C et al (2016) Intraoperative frozen section analysis for the diagnosis of early stage ovarian cancer in suspicious pelvic masses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3(3):CD010360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro A, Piermattei A, Inzani F, Angelico G, Valente M, Arciuolo D, Spadola S, Martini M, Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Gallotta V, Scambia G, Zannoni GF (2019) Frozen section accurately allows pathological characterization of endometrial cancer in patients with a preoperative ambiguous or inconclusive diagnoses: our experience. BMC Cancer. 10.1186/s12885-019-6318-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scurry JP, Sumithran E (1989) An assessment of the value of frozen sections in gynecological surgery. Pathology 21:159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Hsu HC, Tai YJ, Kuo KT, Wu CY, Lai YL et al (2021) Factors influencing the discordancy between intraoperative frozen sections and final paraffin pathologies in ovarian tumors. Front Oncol. 10.3389/fonc.2021.694441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CJR, Brennan BA, Hammond IG, Leung YC, McCartney AJ (2006) Intraoperative assessment of ovarian tumors: a 5-year review with assessment of discrepant diagnostic cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol off J Int Soc Gynecol Pathol 25(3):216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbian A, Devi UK, Bafna UD (2013) Accuracy rate of frozen section studies in ovarian cancers: a regional cancer institute experience. Indian J Cancer 50(4):302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift BE, Tigert M, Nica A, Covens A, Vicus D, Parra-Herran C et al (2022) The accuracy of intraoperative frozen section examination of sentinel lymph nodes in squamous cell cancer of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 164(2):393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Miyamoto S, Terada S, Kogata Y, Fujiwara S, Tanaka Y et al (2020) The diagnostic accuracy of an intraoperative frozen section analysis and imprint cytology of sentinel node biopsy specimens from patients with uterine cervical and endometrial cancer: a retrospective observational study. Pathol Oncol Res 26(4):2273–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempfer CB, Polterauer S, Bentz EK, Reinthaller A, Hefler LA (2007) Accuracy of intraoperative frozen section analysis in borderline tumors of the ovary: a retrospective analysis of 96 cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 107(2):248–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ureyen I, Turan T, Cirik DA, Tasci T, Boran N, Bulbul D et al (2014) Frozen section in borderline ovarian tumors: is it reliable? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 181:115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baal J, Van de Vijver KK, Coffelt SB, van der Noort V, van Driel WJ, Kenter GG et al (2017) Incidence of lymph node metastases in clinical early-stage mucinous and seromucinous ovarian carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 124(3):486–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Tanaka H, Tsukada T, Abeto N, Kobayashi-Kato M, Tanase Y et al (2021) Diagnostic discordance in intraoperative frozen section diagnosis of ovarian tumors: a literature review and analysis of 871 cases treated at a Japanese cancer center. Int J Surg Pathol 29(1):30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]