Abstract

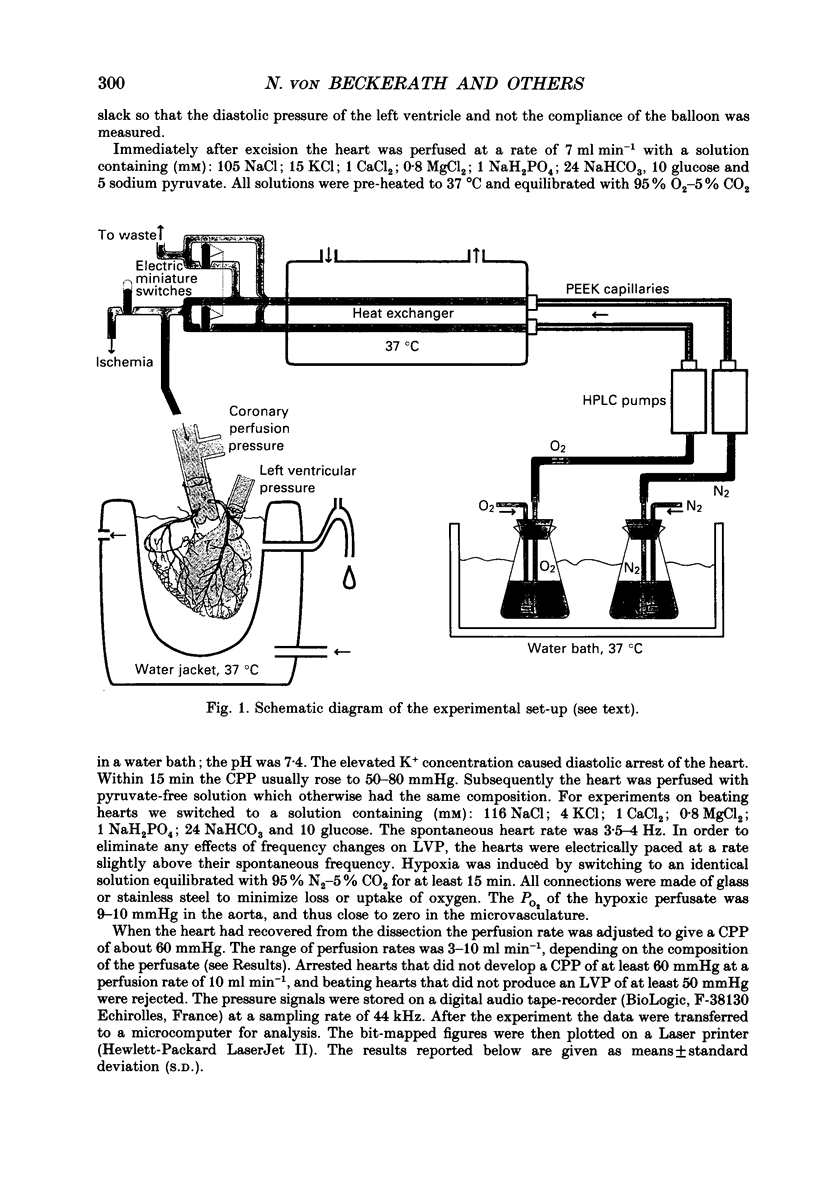

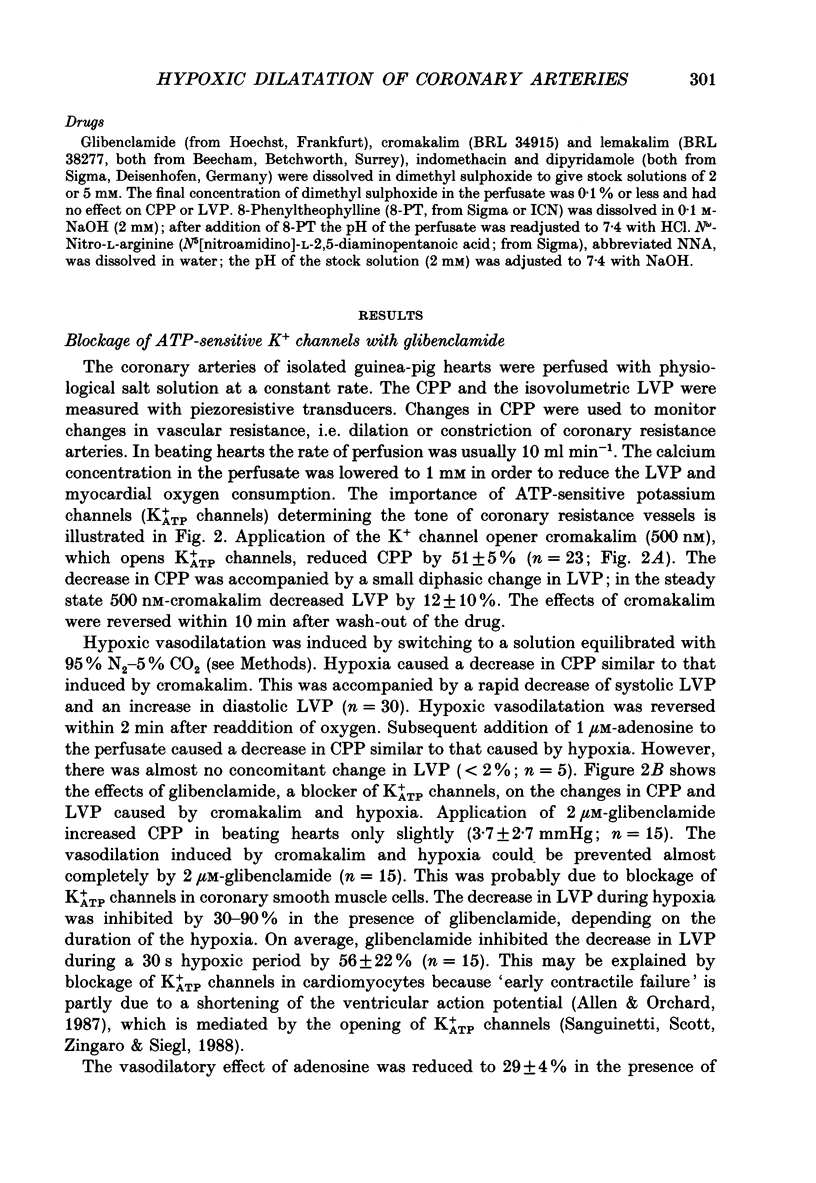

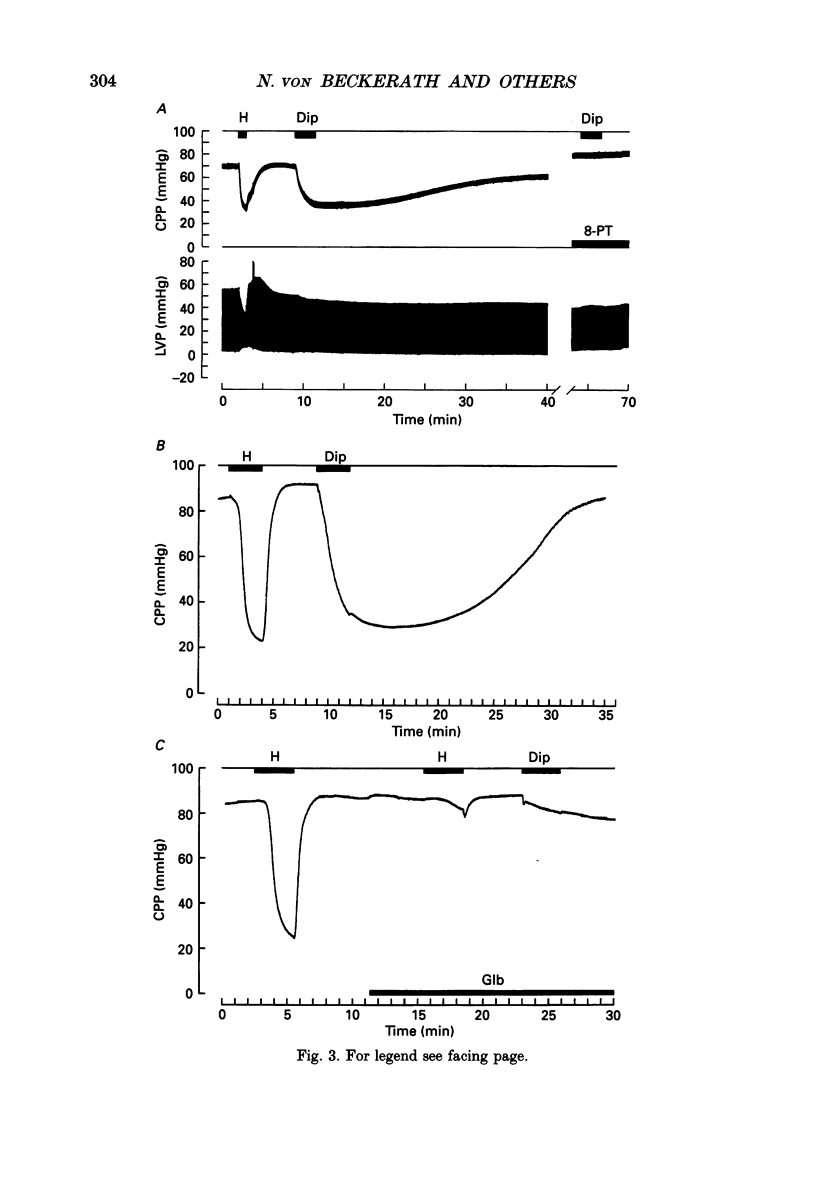

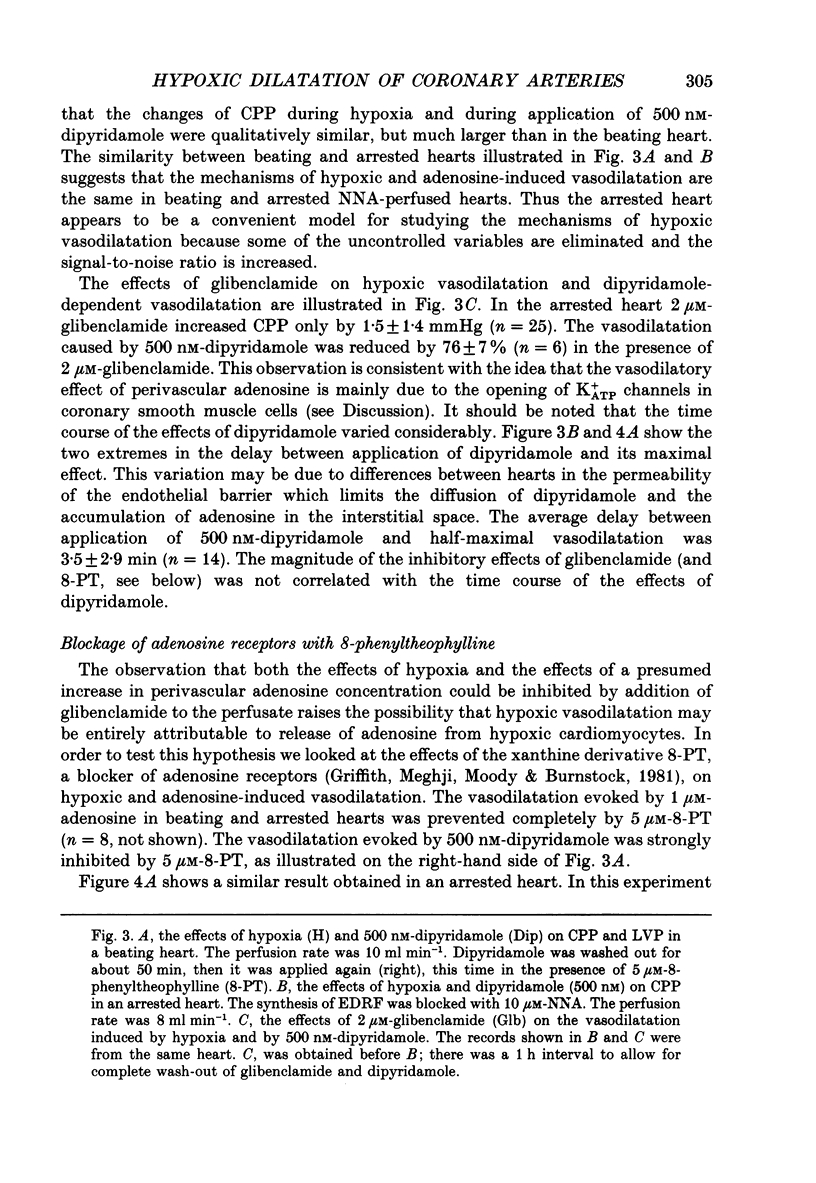

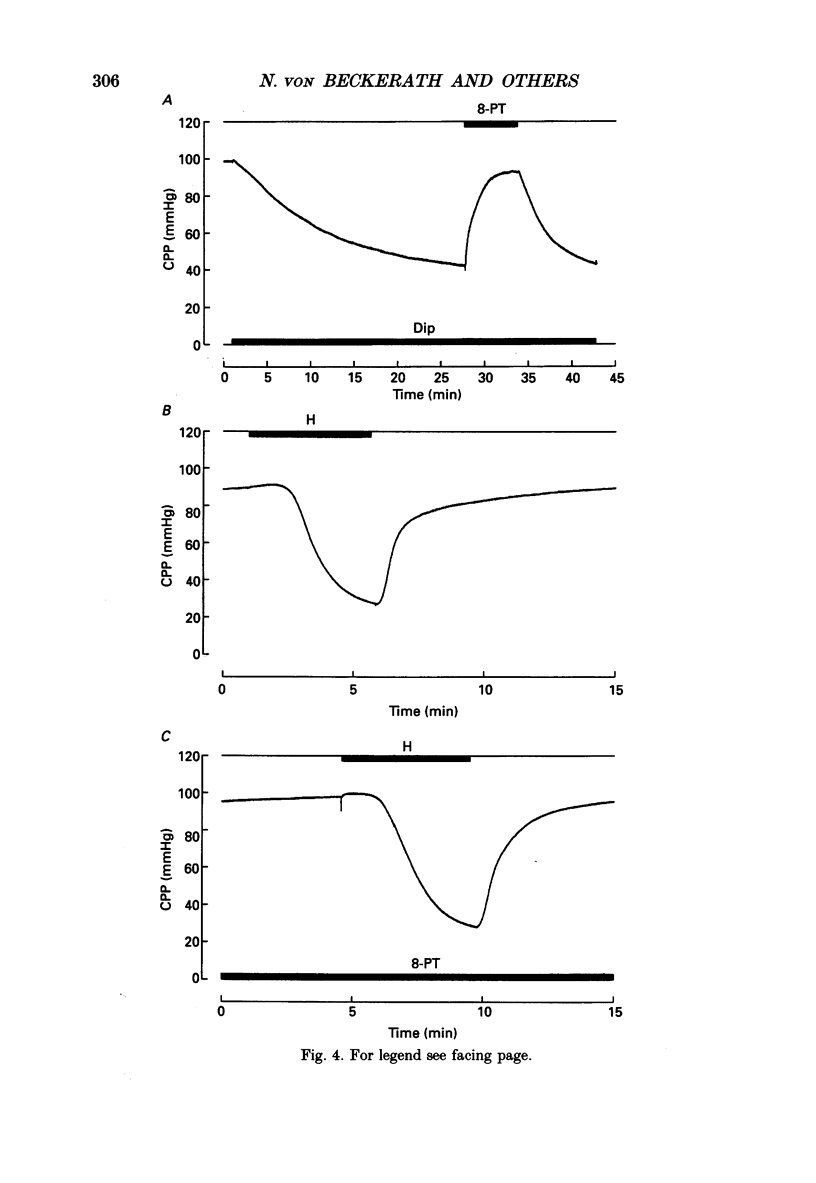

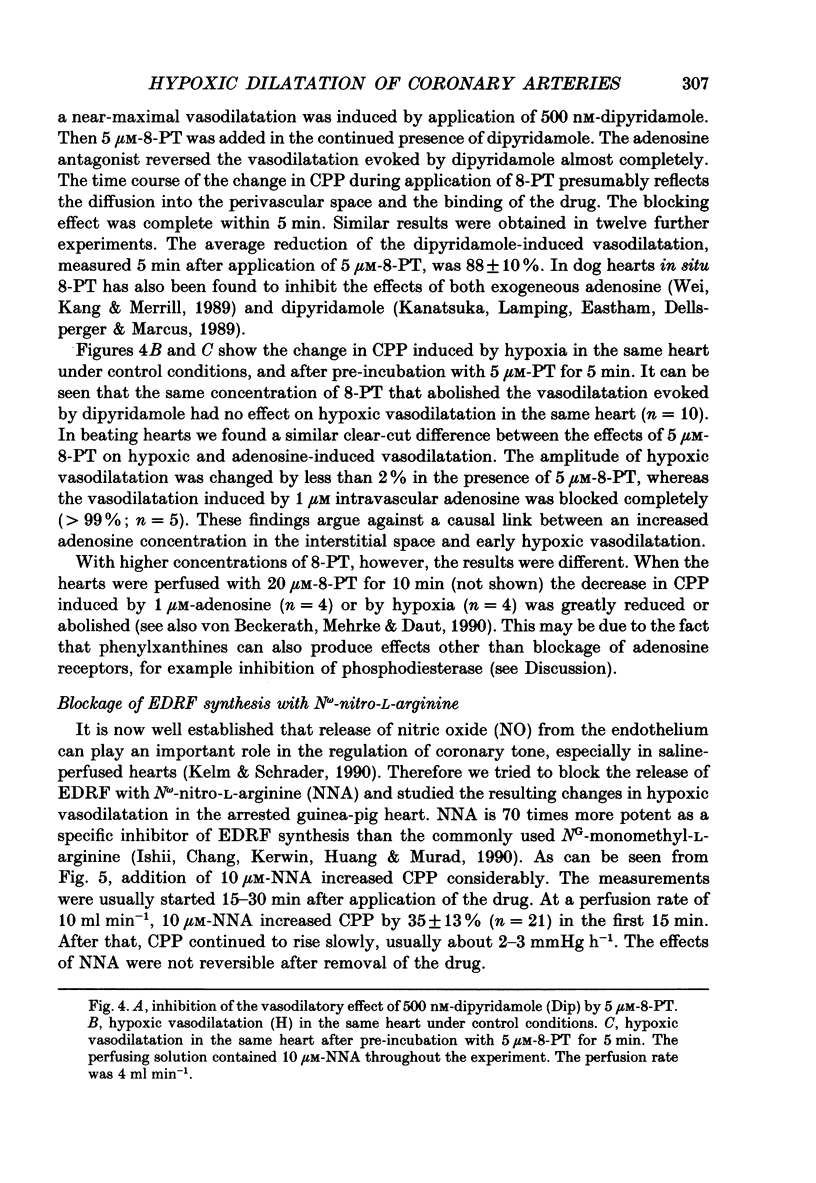

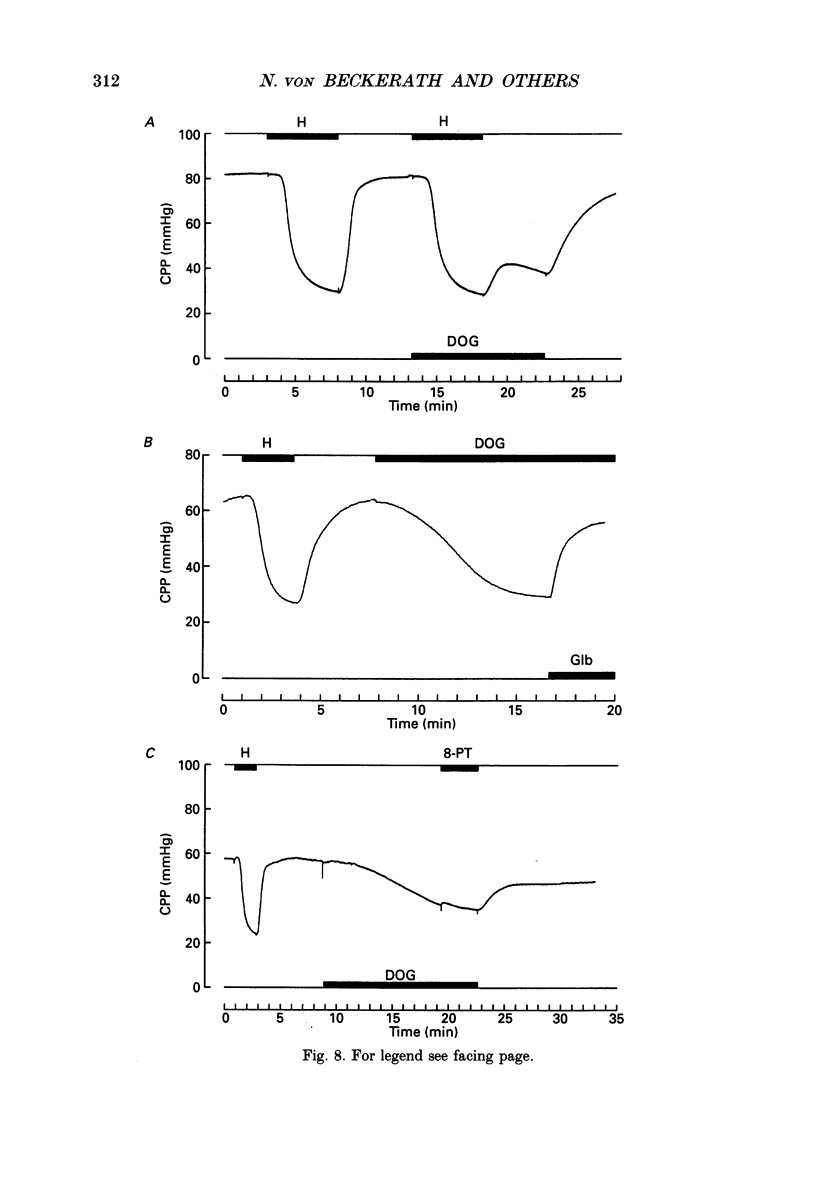

1. The mechanisms underlying hypoxic dilatation of coronary arteries were studied in isolated guinea-pig hearts perfused with physiological salt solution at 37 degrees C. The hearts were perfused at a constant rate of 3-10 ml min-1; coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) and isovolumetric left ventricular pressure (LVP) were measured with piezoresistive transducers. 2. Addition of the K+ channel opener cromakalim (500 nM) to the perfusate caused a maximal vasodilatation in beating hearts, i.e. a decrease in CPP of about 50%. Switching from normal perfusate (partial pressure of O2 (PO2), 650-700 mmHg) to hypoxic perfusate (PO2, 9-10 mmHg) caused a similar vasodilatation. Both of these effects were prevented by 2 microM-glibenclamide, a blocker of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Hypoxic vasodilatation was accompanied by a marked decrease in LVP, which was reduced by 56 +/- 22% (mean +/- S.D.) in the presence of glibenclamide. 3. In hearts arrested by increasing the K+ concentration of the perfusate to 15 mM, the addition of the adenosine-uptake inhibitor dipyridamole evoked a maximal vasodilatation and this was inhibited by 76 +/- 7% in the presence of glibenclamide. 4. The adenosine antagonist 8-phenyltheophylline (8-PT; 5 microM) inhibited the vasodilatation induced by dipyridamole by 88 +/- 10%. In contrast, hypoxic vasodilatation was unaffected by 5 microM 8-PT. This suggests that hypoxic dilatation of coronary arteries is not mediated by release of adenosine from cardiomyocytes. 5. In order to test whether release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) contributed to hypoxic vasodilatation we blocked EDRF synthesis with N omega-nitro-L-arginine (NNA). When applied at a perfusion rate of 10 ml min-1 to arrested hearts, 10 microM-NNA increased CPP by 35% and prolonged the delay between application of hypoxic solution and half-maximal vasodilatation from 52 +/- 9 to 129 +/- 29 s. 6. Under control conditions the relation between perfusion rate and the CPP measured in the steady state was linear. In the presence of 10 microM-NNA coronary resistance was increased more than twofold at low perfusion rates; at perfusion rates between 4 and 10 ml min-1 coronary resistance decreased progressively. This change in the pressure-flow relationship may be responsible for the alterations in the time course of hypoxic vasodilatation induced by NNA. 7. In order to test whether changes in energy metabolism in coronary smooth muscle cells were responsible for hypoxic vasodilatation we blocked glycolysis by replacing the glucose in the perfusate with deoxyglucose (DOG).(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

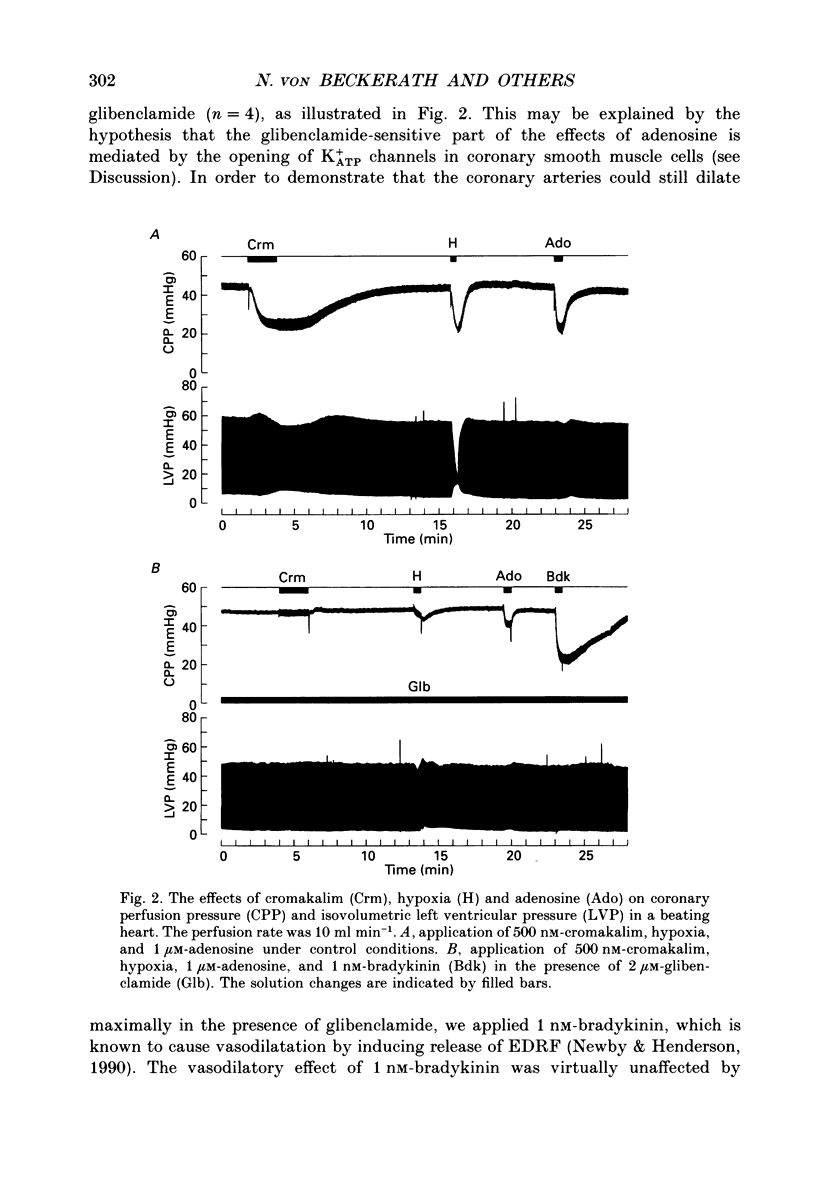

Full text

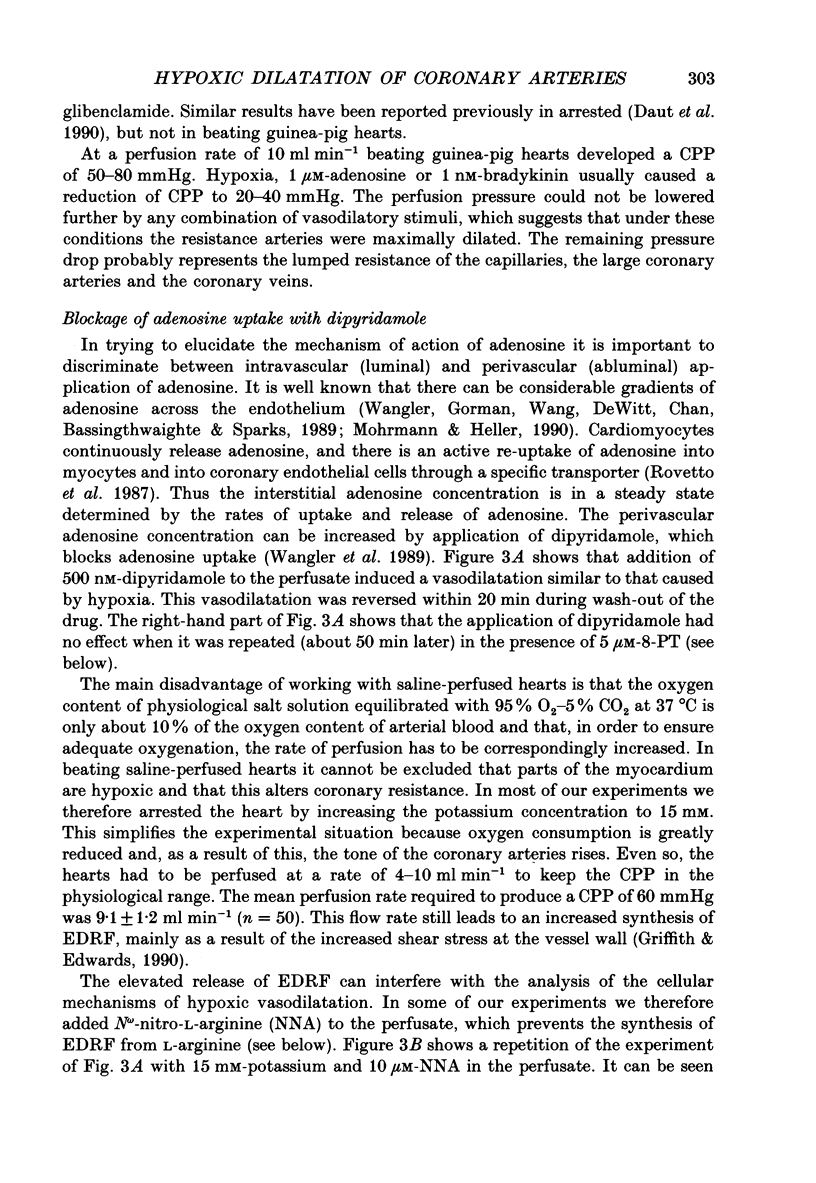

PDF

Images in this article

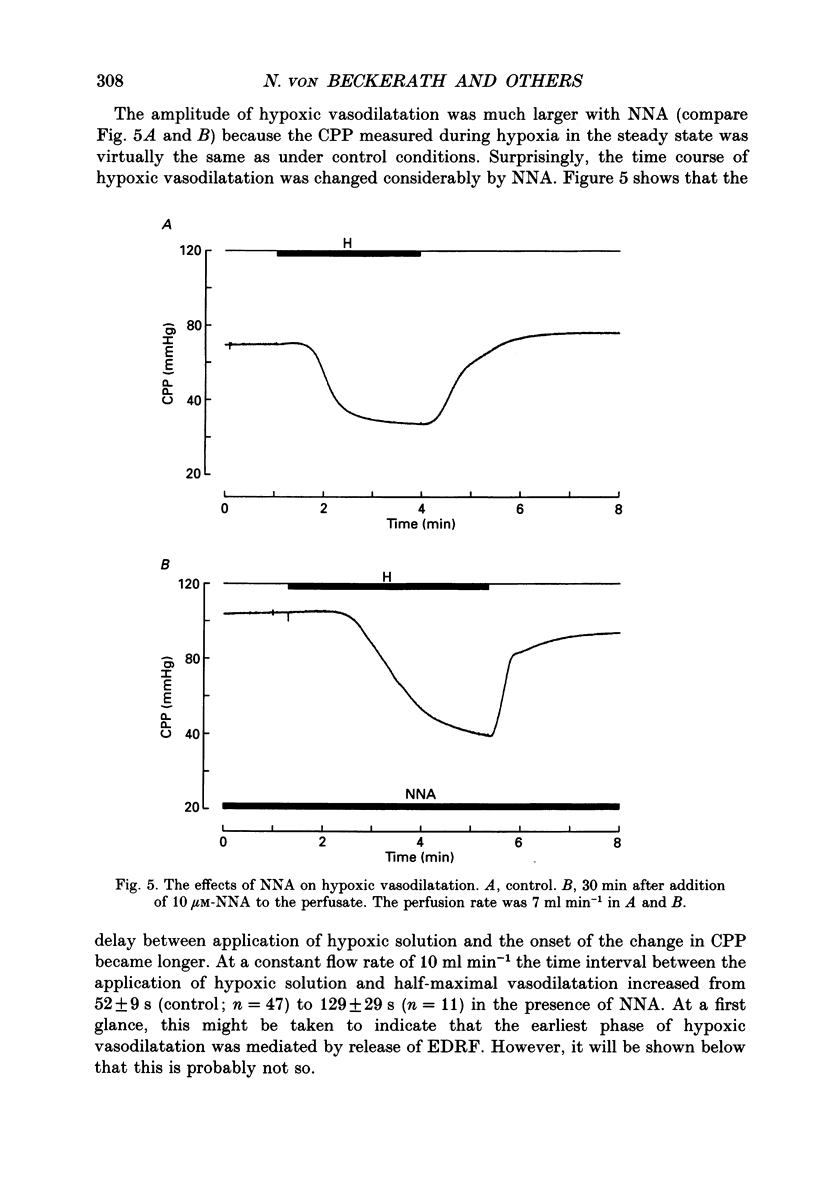

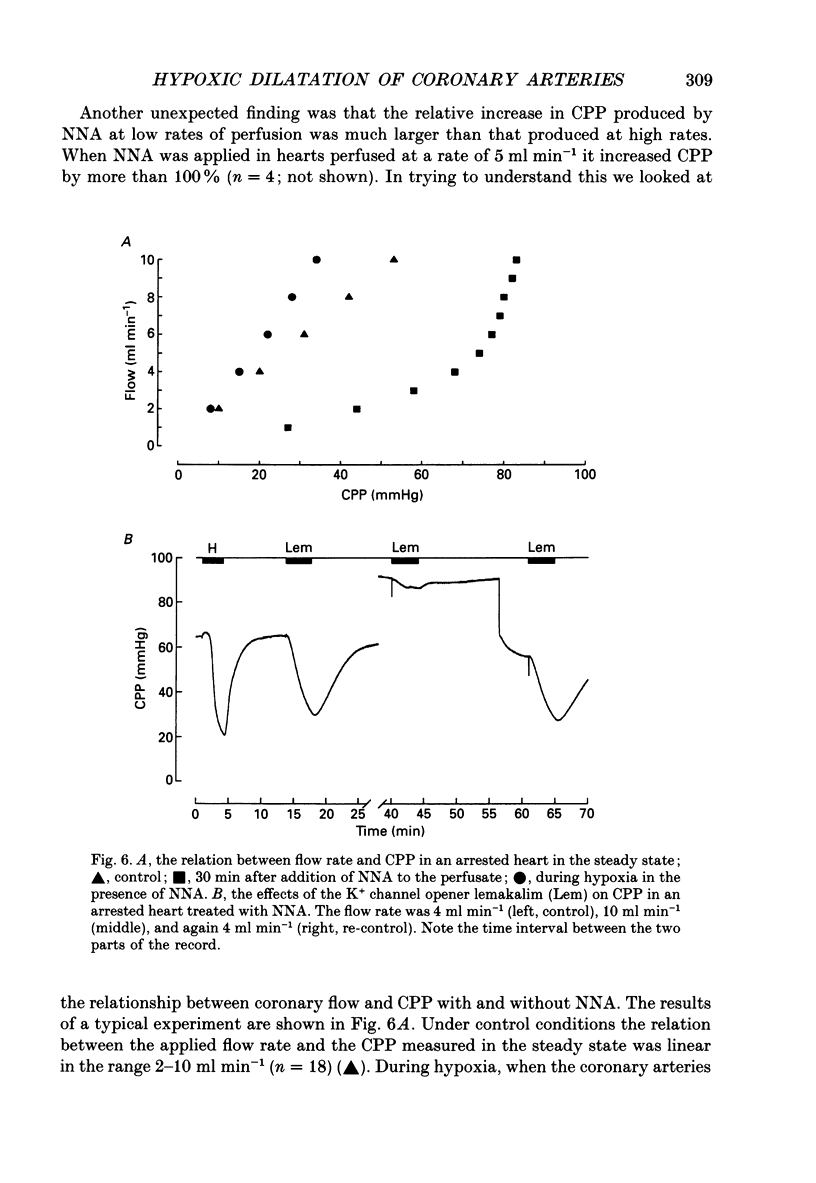

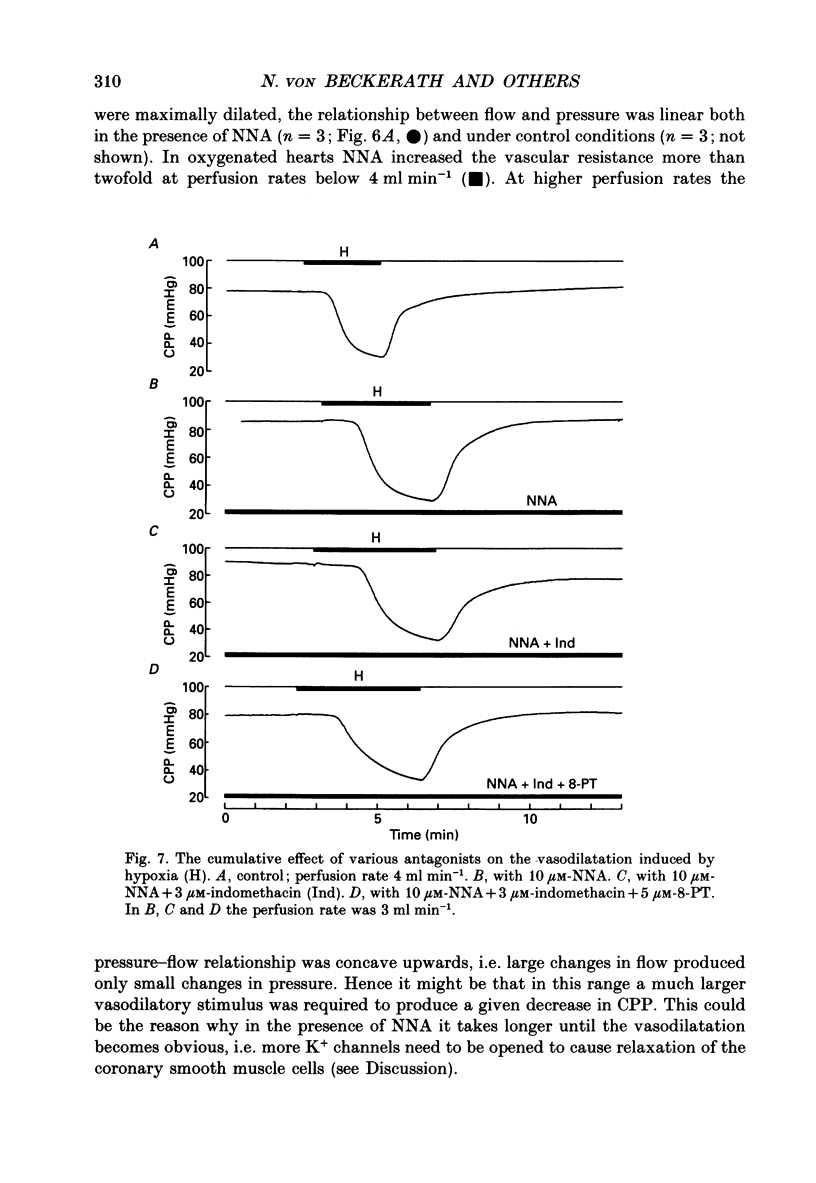

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Orchard C. H. Myocardial contractile function during ischemia and hypoxia. Circ Res. 1987 Feb;60(2):153–168. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft S. J., Ashcroft F. M. Properties and functions of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Cell Signal. 1990;2(3):197–214. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNE R. M. Cardiac nucleotides in hypoxia: possible role in regulation of coronary blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1963 Feb;204:317–322. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.204.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte J. B., Wang C. Y., Chan I. S. Blood-tissue exchange via transport and transformation by capillary endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1989 Oct;65(4):997–1020. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi H., Fosset M., Lazdunski M. Characterization, purification, and affinity labeling of the brain [3H]glibenclamide-binding protein, a putative neuronal ATP-regulated K+ channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Dec;85(24):9816–9820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne R. M. The role of adenosine in the regulation of coronary blood flow. Circ Res. 1980 Dec;47(6):807–813. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan J. A., Joyce E. H., Wellman G. C. Flow-dependent dilation in a resistance artery still occurs after endothelium removal. Circ Res. 1988 Nov;63(5):980–985. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.5.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff P., Sipkema P., Westerhof N. Pump perfusion abolishes autoregulation possibly via prostaglandin release. Am J Physiol. 1988 Aug;255(2 Pt 2):H280–H287. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.2.H280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Vascular control by purines with emphasis on the coronary system. Eur Heart J. 1989 Nov;10 (Suppl F):15–21. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/10.suppl_f.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J., Maier-Rudolph W., von Beckerath N., Mehrke G., Günther K., Goedel-Meinen L. Hypoxic dilation of coronary arteries is mediated by ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Science. 1990 Mar 16;247(4948):1341–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.2107575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith S. G., Meghji P., Moody C. J., Burnstock G. 8-phenyltheophylline: a potent P1-purinoceptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981 Oct 15;75(1):61–64. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith T. M., Edwards D. H., Davies R. L., Henderson A. H. The role of EDRF in flow distribution: a microangiographic study of the rabbit isolated ear. Microvasc Res. 1989 Mar;37(2):162–177. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith T. M., Edwards D. H. Myogenic autoregulation of flow may be inversely related to endothelium-derived relaxing factor activity. Am J Physiol. 1990 Apr;258(4 Pt 2):H1171–H1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.4.H1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood A. M., Lincoln J., Kirkpatrick K. A., Burnstock G. Adenosine 5'-triphosphate, adenosine and endothelium-derived relaxing factor in hypoxic vasodilatation of the heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989 Jun 20;165(2-3):323–326. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90730-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K., Chang B., Kerwin J. F., Jr, Huang Z. J., Murad F. N omega-nitro-L-arginine: a potent inhibitor of endothelium-derived relaxing factor formation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990 Feb 6;176(2):219–223. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90531-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. C. Autoregulation of blood flow. Circ Res. 1986 Nov;59(5):483–495. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsuka H., Lamping K. G., Eastham C. L., Dellsperger K. C., Marcus M. L. Comparison of the effects of increased myocardial oxygen consumption and adenosine on the coronary microvascular resistance. Circ Res. 1989 Nov;65(5):1296–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm M., Schrader J. Control of coronary vascular tone by nitric oxide. Circ Res. 1990 Jun;66(6):1561–1575. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch G. E., Codina J., Birnbaumer L., Brown A. M. Coupling of ATP-sensitive K+ channels to A1 receptors by G proteins in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1990 Sep;259(3 Pt 2):H820–H826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrke G., Daut J. The electrical response of cultured guinea-pig coronary endothelial cells to endothelium-dependent vasodilators. J Physiol. 1990 Nov;430:251–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrke G., Pohl U., Daut J. Effects of vasoactive agonists on the membrane potential of cultured bovine aortic and guinea-pig coronary endothelium. J Physiol. 1991 Aug;439:277–299. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrman D. E., Heller L. J. Transcapillary adenosine transport in isolated guinea pig and rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1990 Sep;259(3 Pt 2):H772–H783. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nees S., Herzog V., Becker B. F., Böck M., Des Rosiers Ch, Gerlach E. The coronary endothelium: a highly active metabolic barrier for adenosine. Basic Res Cardiol. 1985 Sep-Oct;80(5):515–529. doi: 10.1007/BF01907915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. T., Patlak J. B., Worley J. F., Standen N. B. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jul;259(1 Pt 1):C3–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby A. C., Henderson A. H. Stimulus-secretion coupling in vascular endothelial cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 1990;52:661–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.003305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson R. A., Bünger R. Metabolic control of coronary blood flow. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1987 Mar-Apr;29(5):369–387. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(87)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl U., Busse R. Hypoxia stimulates release of endothelium-derived relaxant factor. Am J Physiol. 1989 Jun;256(6 Pt 2):H1595–H1600. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.6.H1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabouni M. H., Hargittai P. T., Lieberman E. M., Mustafa S. J. Evidence for adenosine receptor-mediated hyperpolarization in coronary smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1989 Nov;257(5 Pt 2):H1750–H1752. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti M. C., Scott A. L., Zingaro G. J., Siegl P. K. BRL 34915 (cromakalim) activates ATP-sensitive K+ current in cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Nov;85(21):8360–8364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangler R. D., Gorman M. W., Wang C. Y., DeWitt D. F., Chan I. S., Bassingthwaighte J. B., Sparks H. V. Transcapillary adenosine transport and interstitial adenosine concentration in guinea pig hearts. Am J Physiol. 1989 Jul;257(1 Pt 2):H89–106. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H. M., Kang Y. H., Merrill G. F. Canine coronary vasodepressor responses to hypoxia are abolished by 8-phenyltheophylline. Am J Physiol. 1989 Oct;257(4 Pt 2):H1043–H1048. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.4.H1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]