Abstract

Nitrate pollution frequently impacts groundwater quality, particularly in agricultural regions across the world, but identifying the sources of nitrate (NO3−) pollution remains challenging. The extensive use of nitrogen-containing fertilizers, surpassing crop requirements, and livestock management practices associated with the spreading of manure can lead to the accumulation and transport of NO3− into groundwater, potentially affecting drinking water sources. We investigated the occurrence and distribution of NO3− in groundwater in Southern Alberta, Canada, a region characterized by intensive crop cultivation and livestock industry. Over 3500 samples from a provincial-scale groundwater quality database, collated from multiple projects and sources, involving domestic wells, monitoring wells, and springs, coupled with newly obtained samples from monitoring wells provided comprehensive geochemical insights into groundwater quality. While stable isotope compositions of NO3− (δ15N and δ18O) were exclusively available for groundwater samples obtained from monitoring wells, the stable isotope data were instrumental in constraining NO3− sources and transformation processes within the aquifers of the study region. Among all samples, 49% (n = 1746) were associated with NO3− concentrations below the detection limits. Ten percent (n = 369) of all groundwater samples, including samples with concentrations below detection limits, exceed the Canadian drinking water maximum acceptable concentration of 10 mg/L for nitrate as nitrogen (NO3−–N). Elevated NO3− concentrations (> 10 mg/L as NO3−–N) in groundwater were mainly detected at shallow depths (< 30 m) predominantly in aquifers in surficial sediments and less frequently in bedrock aquifers. Statistical correlations between aqueous geochemical parameters showed positive associations between concentrations of NO3−–N and both potassium (K+) and chloride (Cl−), indicating the influence of synthetic fertilizers on groundwater quality. In addition, isotope analyses of NO3− (δ15N and δ18O) revealed three NO3− sources in groundwater, including mineralization of soil organic nitrogen followed by nitrification in soils, nitrification of ammonium or urea-based synthetic fertilizers in soils, and manure. However, manure was identified as the dominant source of NO3− exceeding the maximum acceptable concentration in groundwater within agriculturally dominated areas. Additionally, this multifaceted approach helped identify denitrification in some groundwater samples, a process that plays a key role in reducing NO3− concentrations under favorable redox conditions in shallow aquifers. The methodological approach used in this study can be applied to other regions worldwide to identify NO3− sources and removal processes in contaminated aquifers, provided there are well networks in place to monitor groundwater quality and drinking water sources.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10533-025-01209-8.

Keywords: Groundwater quality, Nitrate, Agriculture, Fertilizers, Manure

Introduction

The global population relies on clean, fresh water not only for drinking purposes but also to sustain agriculture, support industrial activities, and maintain ecological balance. Groundwater serves as a primary source of safe drinking water for millions of people worldwide (Smith et al. 2016). Despite its fundamental importance and limited availability, groundwater resources are increasingly affected by widespread NO3− pollution derived from agricultural activities and urban discharges. Nitrate contamination can substantially degrade groundwater quality, affecting not only individual communities but also entire regions and nations that depend on groundwater to meet their essential needs (Galloway et al. 1995; Kim et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2020; Harris et al. 2022).

Nitrate, the most oxidized dissolved species of nitrogen (+ V), commonly constitutes over 80% of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) in surface waters as it is the most stable form under oxidizing conditions (Meybeck 1982). Nitrate is also highly soluble and mobile in soils, allowing water containing NO3− to enter surface waters or infiltrate through the soil into groundwater (Carpenter et al. 1998). Elevated concentrations of NO3− in drinking water obtained either from surface water or groundwater have been shown to adversely affect human health, causing methemoglobinemia in infants under six months old, birth defects, thyroid disease, and some types of cancer (Ward et al. 2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) established a drinking water guideline of 50 mg NO3−/L (WHO 2022). In Canada, the drinking water guideline, also referred to as the maximum acceptable concentration (MAC), of NO3− is set at 45 mg/L as NO3− or 10 mg/L as NO3−–N (Health Canada 2013). Recent epidemiological studies suggest there may be economic and health benefits of lowering drinking water standards to < 2 mg/L as NO3−–N (Jacobsen et al. 2024).

While NO3− release into the water can result from natural processes, human activities are mainly responsible for the occurrence of elevated NO3− concentrations in surface waters and shallow groundwater (Nordin and Pommen 1986; Holloway et al. 1998; Kendall 1998). Agricultural practices are often a key factor causing high NO3− inputs to freshwater resources (Moss 2008). Numerous studies across Europe, the United States, and Asia have demonstrated the direct link between agricultural practices and elevated NO3− concentrations in water systems (e.g., Dubrovsky et al. 2010; Kristensen et al. 2018; Harris et al. 2022; Racchetti et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2020). An extensive assessment of surface water and groundwater quality in the United States reported that NO3−–N concentrations exceeding background levels of 1 mg/L were commonly associated with agricultural and urban land use (Dubrovsky et al. 2010). In Northeast China, groundwater quality was closely related to land use, with agricultural activities and chemical fertilizer application identified as the primary source for regions exhibiting elevated NO3− concentrations (Yu et al. 2020). Racchetti et al. (2019) and Harris et al. (2022) demonstrated the influence of NO3− derived from synthetic fertilizer applications on irrigated land and the interaction with groundwater in some parts of Italy and Australia, respectively, resulting in nitrate-contaminated groundwaters. Similarly in Germany and Spain, agriculture and the application of synthetic fertilizers and manure have been attributed as the main cause of high concentrations of NO3− in groundwater (Kristensen et al. 2018). These studies evidenced a complex interaction of factors influencing NO3− concentrations in groundwater, including land use features, nitrogen transformations in soils, and aquifer characteristics. In Canada, groundwater contamination by agricultural NO3− is a well-known issue in some regions (e.g., Abbotsford, British Columbia, Wassenaar 1995). However, there is a lack of groundwater NO3− studies that document the extent of NO3− contamination at regional scales in agricultural areas, particularly those that integrate isotopic and hydrochemical data.

In Canada, agriculture is one of the major contributors to the economy, ranking as the fifth-largest exporter of agri-food products in the world (Government of Canada 2023). This robust agricultural sector has led to a considerable surge in the use of nitrogen-containing commercial fertilizers, with approximately a 2.5-fold increase from 800,000 metric tonnes in 1980 to 2,000,000 metric tonnes in 2010 (Dorff and Beaulieu 2014). The province of Alberta is one of the leaders in grain cultivation and livestock production in Canada, ranking as the second-highest user of commercial fertilizers in Canada, applying them to approximately 73% of the total cropland (Dorff and Beaulieu 2014). Similarly, Alberta ranks as the second-highest user of manure as a fertilizer on farmland due to the extensive cattle industry in the province (Dorff and Beaulieu 2014). Particularly the southern region of Alberta is characterized by a distinct landscape with concentrated cultivation of wheat, barley, and canola, and a large cattle industry supported by confined feeding operations (CFO) due to the availability of irrigation water (ABMI 2019; ORRSC 2022). Southern Alberta has the largest irrigation infrastructure in Canada, with approximately 6000 km2 of land irrigated within 11 irrigation districts (AMEC 2009).

Groundwater in the province of Alberta plays a crucial role in providing drinking water to more than 90% of the rural population, approximately 600,000 people (Government of Alberta 2021b). The intensive agricultural activities, particularly prevalent in Southern Alberta, may affect the quality of this resource due to the high use of manure (Kohn et al. 2021; Kyte et al. 2023). Although several studies have investigated the sources and potential controls of NO3− in aquatic systems, they have mainly focused on surface waters (Rock and Mayer 2004a, b; Kruk et al. 2020; Kobryn and Villeneuve 2021). In groundwater, studies by Rodvang et al. (2004, 2014), Olson et al. (2009), Bourke et al. (2015, 2019), and Kohn et al. (2016), and most recently (Kyte et al. 2023) have focused on understanding the impact of manure application on land and manure storage on groundwater NO3− concentrations. Hendry et al. (1984) suggested that elevated NO3− concentrations in groundwater in Southern Alberta may also result from the natural oxidation of ammonium present in glacial till deposits. Other regional to province-wide groundwater studies in Alberta (Fitzgerald et al. 2001; Forrest et al. 2006; Wilson 2019; Kohn et al. 2020) have focused on reporting spatial variations of NO3− concentrations in groundwater. However, a comprehensive assessment incorporating available NO3− data with geochemical and redox conditions of groundwater is still missing across regional aquifers below cropland with a mix of intensive agricultural activities. Our objective was to integrate aqueous geochemistry, N and O stable isotope ratios (δ15N and δ18O) of NO3−, land use data, and geological information to identify the dominant sources of NO3− contamination in shallow groundwater and to determine the processes capable of removing NO3− from aquifers. To test this approach, we investigated the occurrence and distribution of NO3− in groundwater across a 48,900 km2 region in Southern Alberta, Canada, characterized by intensive crop cultivation and livestock operations. Using an extensive groundwater chemistry dataset sourced from multiple archival databases, supplemented by newly acquired groundwater samples from monitoring wells, we formulated and tested the following hypotheses: (1) nitrate concentrations are significantly higher in shallow groundwater (< 30 m) compared to deeper aquifers due to greater exposure to surface derived-nitrogen inputs, (2) groundwater NO3− concentrations are elevated in aquifers beneath irrigated areas compared to non-irrigated regions, (3) regions with high livestock density and manure production exhibit positive correlations with elevated NO3− concentrations in groundwater, (4) dual NO3− isotope (δ15N and δ1⁸O) signatures, combined with groundwater geochemical indicators, are expected to reveal manure as the dominant source of NO3− contamination, reflecting the prevalence of CFOs and extensive manure application on farmland, and (5) given the natural and geologically controlled reducing conditions present even in shallow aquifers in Alberta, isotopic evidence is expected to indicate denitrification as a key pathway for NO3− removal.

Study area

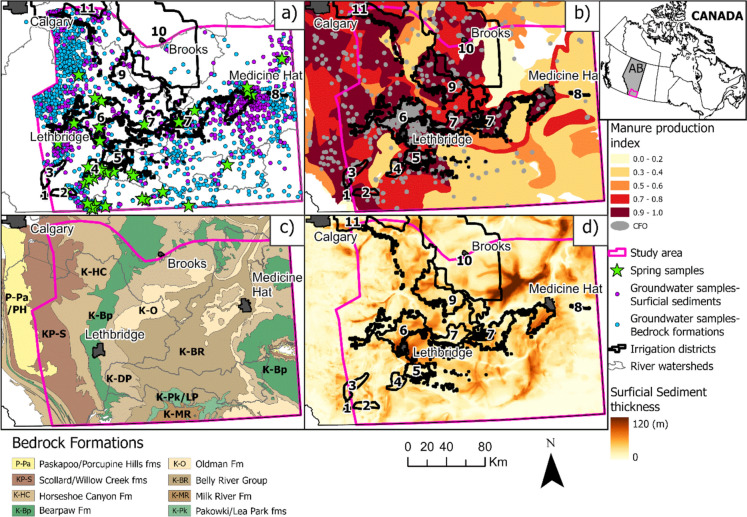

The study area (Fig. 1) is located in Southern Alberta, Canada, southeast of the City of Calgary and east of the Rocky Mountains. To the east, the limit of the study area is the border with the Province of Saskatchewan, and to the south, the border with the State of Montana (United States of America). The study area is approximately 48,900 km2, which is > 100 times larger than most previous studies on groundwater NO3− in Southern Alberta. The study area includes portions of four major watersheds including the Bow River, Oldman River, Milk River, and South Saskatchewan River watersheds. The area is characterized by prairie and semi-arid plains that are part of Alberta's Mixedgrass and Dry Mixedgrass Natural Subregions (Downing and Pettapiece 2006). Elevations range from 1450 to 550 m decreasing from west to east, except for the Cypress Hills in the east, with a maximum elevation of 1450 m, with a mainly undulating topography, and some portions of hummocky uplands (Downing and Pettapiece 2006). The undulating topography creates small wetlands known as prairie potholes, representing important locations for depression-focused recharge of shallow aquifers (Hayashi et al. 1998). The daily temperature ranges from typically − 30 to 0 °C in winter, and from + 10 to above + 30 °C in the summer, while annual precipitation is usually less than 374 mm in Southern Alberta (Downing and Pettapiece 2006). The most common soil types are Dark Brown and Brown Chernozems in the mixed-grass and dry mixed-grass subregions, respectively (Downing and Pettapiece 2006; AMEC 2009).

Fig. 1.

Location map of Southern Alberta showing a the location of the different groundwater sample types, b the manure production index (AAFRD 2005) and location of confined feeding operations (CFOs, shown as light grey dots) (ABMI 2019), c bedrock geology modified from Prior et al. (2013), and d thickness of surficial sediments modified from Atkinson et al. (2020). In three panels, the location of irrigation districts is shown as outlined-black polygons

Land use

Fifty-eight percent of the land in the study area is influenced by human activity, while the remaining 42% shows minimal or no evidence of human footprint (ABMI 2019). The primary land use in the area is agriculture (~ 50%), dominated mainly by cultivation (42%) of wheat, canola, barley, dry peas, vegetables, and fruits. Other agricultural land uses include the growth of hay (tame pasture) and rough pastures (~ 7%). The livestock industry is also an essential part of the economy in the province, with over 5 million cattle and calves on Alberta farms, representing more than 40% of the cattle and calf population in Canada (Statistics Canada 2023a), either free-ranging on pastures or in feedlots. Confined feeding operations (CFOs) constitute an important component of livestock management, providing enclosed spaces or fenced lands for the growth and sustenance of animals (ORRSC 2022). In Southern Alberta, > 2200 CFOs cover 0.2% of the total study area (ABMI 2019), as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Oil and natural gas operations are also common across the area, contributing roughly 2% to the human footprint in the region, followed by transportation infrastructure accounting 1%, with rural and urban residential areas contributing an additional 1% (ABMI 2019).

Due to the low annual precipitation, irrigation is essential for some crops in Southern Alberta, providing indispensable support to agricultural systems. Currently, there are 11 irrigation districts located in Southern Alberta that provide water to farmers and rural residents (Government of Alberta 2023c). Most of the irrigation districts (8.5 of 11) are located within the study area (Fig. 1). Irrigation canal water originates from reservoirs on upstream rivers, that are in part fed by headwater streams located in the forested eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains (AMEC 2009). These headwater streams experience limited anthropogenic N inputs, with reported levels of 1908 kg N/km2/year in the late 1990s, compared to higher loads of 5123 kg/km2/year in areas with large agricultural activities (Rock and Mayer 2004a, b). In 2022, Alberta used 1.6 billion m3 of irrigation water, accounting for nearly 75% of all irrigation water applied to crops across Canada (Statistics Canada 2023c).

The intensive agricultural land use in Southern Alberta relies on the application of synthetic fertilizers and manure to the fields to facilitate the growth of several types of crops. The most common types of synthetic fertilizers used in field and forage crops as well as in fruit and vegetable production are urea-based products, custom or common blends containing nitrogen and phosphorus, followed by ammonium sulfate and ammonia or anhydrous ammonia, among others (Statistics Canada 2022). Due to the large cattle inventory, manure is also a significant source of nutrients commonly applied to the land as an organic fertilizer in Southern Alberta (Statistics Canada 2017). Figure 1b shows the relative amount of manure production represented by an index between 0 (lowest) and 1 (highest) in the study area (AAFRD 2005).

In addition to the potential agricultural influence on NO3− in groundwater, effluents from rural septic systems and wastewater treatment plants can also contribute to elevated NO3− concentrations in aquatic systems, as suggested by Kruk et al. (2020) for surface water of the Bow River in Southern Alberta. However, the population in the study area of Southern Alberta comprises only 7% of the total population of the province, with a considerable portion concentrated in urban centers, including Lethbridge and Medicine Hat (Statistics Canada 2023b). Therefore, the total population inhabits less than 1% of the land in the study area, resulting in a population density of < 10 persons/km2 (AMEC 2009; ABMI 2019).

Geology and hydrogeology

The study area lies within the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), where Late Cretaceous to Paleocene formations serve as key bedrock aquifers (Fig. 1c; Fig. S1). These formations (Milk River formation, Belly River Group, Horseshoe Canyon/St. Mary River, Scollard/Willow Creek, and Paskapoo/Porcupine Hills formations) consist of sandstones, siltstones, and mudstones primarily deposited in non-marine and shallow marine environments, which act as aquifers or aquifer/aquitard mixtures (Jim Hendry et al., 1991; Eberth and Hamblin, 1993; Dawson et al. 1994; Grasby et al. 2008). Aquitards composed of mudstones, shales, and siltstones include the Pakowki/upper Lea Park, the Bearpaw, and the Battle formations (Dawson et al. 1994; Atkinson et al. 2017).

Most of the Upper Cretaceous–Paleogene clastic wedge of bedrock formations is covered by heterogeneous sediments of fluvial, lacustrine, and glacial origin (Fig. 1d) deposited during the Neogene and Quaternary (Fenton et al. 1994; Atkinson et al. 2020). These surficial sediments are predominantly tills deposited from the Laurentide Ice Sheet and are commonly considered aquitards overlying localized coarse-grained Quaternary fluvial sediments that host aquifers (Fenton et al. 1994). The thickness of surficial sediments can vary across the study area (Fig. 1d), ranging from an absent cover, especially in topographic hills, to about 120 m in some preglacial valleys (Atkinson et al. 2020). A redox boundary (redoxcline) is observed within surficial sediments, marked by a transition from oxidized reddish-brown sediment to reduced gray sediment. This shift occurred due to a lower water table during the mid-Holocene (Rodvang and Simpkins 2001). The redox boundary is often found at depths ranging from 4 to 16 m, and up to 25 m in areas with thick sediment cover. It also appears in bedrock formations, such as the Paskapoo Formation, where glacial deposits are absent or thin (Hendry et al. 1984; Rodvang and Simpkins 2001; Grasby et al. 2008).

Hydraulic conductivity (K) values have been reported to vary from 10−7 to 10−9 m/s in weathered tills, but K can reach lower values of ~ 10−11 m/s for non-weathered tills in the absence of fractures (Hendry et al. 1984). Hydraulic conductivity is higher in sand layers of aquifers ranging from 10−7 to 10−5 m/s (Bourke et al. 2019). In some bedrock units (e.g., Paskapoo Formation), a higher K of 10−3 m/s has been reported in coarse-grained sandstones (Grasby et al. 2008).

Materials and methods

This study is based on water quality data from four archived sources and newly obtained groundwater samples from monitoring wells. Groundwater hydrogeochemical data were compiled by the Applied Geochemistry Group (AGg, University of Calgary) with support from researchers at the Alberta Geological Survey (AGS) and Alberta Environment and Protected Areas (EPA). Source data included the Alberta Water Well Information Database (AWWID), a publicly available database with water well records from the early 1900s to 2013. This database contains information about domestic and monitoring water wells across the province and associated aqueous geochemical data (Government of Alberta 2021a). A dedicated monitoring water well network owned by the Government of Alberta, the Groundwater Observation Well Network (GOWN), contains records from approximately 1159 wells installed since the 1950s. Currently, over 200 GOWN wells are monitored for water levels every hour, and 50 to 100 wells are sampled annually for water quality (Government of Alberta 2023b). The Alberta Health Services (AHS) dataset contains water quality information for more than 60,000 samples collected since the early 2000s from domestic water wells in rural areas of Alberta. The Baseline Water Well Testing (BWWT) dataset contains water quality information for more than 14,000 groundwater samples obtained from wells located predominantly in central Alberta, in the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor. These data were collected under a program established in 2006 to monitor domestic water wells that were within a radius of 600 to 800 m from newly completed coal bed methane (CBM) wells above the base of groundwater protection.

Groundwater samples obtained within the above-mentioned sampling programs were collected following slightly different protocols and have varying amounts of metadata retained within each original dataset. The AHS samples were usually collected by the well owner from the kitchen tap or the wellhead and sent to a certified laboratory for physical and chemical testing, as detailed by Alberta Health (2014). Groundwater samples from the GOWN monitoring network were collected from the wellhead after pumping several well volumes, and after pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, redox, and electrical conductivity had stabilized (Humez et al. 2019). These field parameters were measured using multi-parameter continuous water quality monitoring sondes (YSI 6600 XLM, EX01, or EX02). The sample tubing was connected to a 400–900 mL flow-through cell and field parameters were logged at 1–2 min intervals for a total of 15 consecutive readings or until field parameters had stabilized. Groundwater samples from the BWWT program were also collected from the wellhead after field parameters had stabilized. The AWWID samples were collected following protocols similar to those outlined by AHS and GOWN. Detailed information about each dataset incorporated into the database can be found in Humez et al. (2019).

Groundwater samples were analyzed for concentrations of major and minor ions, and trace elements by certified laboratories using standard techniques, including the Alberta Center for Toxicology, InnoTech Alberta, and ALS Environmental. Analysis of groundwater samples included major and minor ions such as calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), iron (Fe2+), chloride (Cl−), bicarbonate (HCO3−), sulfate (SO42−), and NO3−–N. Most samples did not include measurements of dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations and field-measured redox potential (Eh) values. However, all samples were included in the analysis. Concentrations of NO3−, reported here as NO3−–N and measured typically using ion chromatography (IC) had detection limits ranging from 0.001 to 0.25 mg/L as NO3−–N. Given the challenges with incomplete metadata and methods variability, we have included all data that passed the quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) tests and made the assumption that the resulting datasets are sufficiently comparable for the purpose of this study. This assumption acknowledges potential limitations but enables a comprehensive assessment of NO3− contamination across large regions.

Groundwater samples for the analysis of N and O isotope ratios of NO3− were filtered in the field using an in-line 0.2 μm disposable capsule membrane (Waterra CAP600X-0.22) and frozen until analysis. The δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− values of NO3− were analyzed for groundwater samples with NO3−–N concentrations above 0.1 mg/L at the Isotope Science Laboratory (ISL) at the University of Calgary (Calgary, Alberta, Canada). The reported δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− values were obtained from 2006 onward. Oxygen and nitrogen isotope ratios are reported in the standard delta (δ) notation in permil (‰) and are reported relative to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW) for δ18O–NO3−, and N2 in air for δ15N–NO3−. The δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− values of NO3− were determined using bacterial reduction of NO3− to produce nitrous oxide (N2O) through the denitrifier method (Sigman et al. 2001; Casciotti et al. 2002) followed by isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) using a Thermo Scientific Delta V Plus coupled to a Thermo Scientific PreCon device. Standardization of the isotope ratio measurements was achieved by calibrating against international reference materials including IAEA N1 (δ15N 0.4 ± 0.3‰), N2 (δ15N 20.3 ± 0.3) and NO3 (δ15N 4.7 ± 0.2‰) and USGS 32 (δ15N 180 ± 1.0‰), 34 (δ15N − 1.8 ± 0.2‰) and 35 (δ15N 2.7 ± 0.2‰) for N isotope measurements and IAEA NO3 (δ18O 25.6 ± 0.4‰) and USGS 32 (δ18O 25.7 ± 0.4‰), 34 (δ18O − 27.9 ± 0.6‰) and 35 (δ18O 57.5 ± 0.6 ‰) for O isotope measurements of NO3−. The accuracy of the measured δ15N and δ18O values of NO3− were ± 0.3‰ and ± 0.7‰, respectively.

After a careful QA/QC procedure, ensuring that samples had valid coordinates, well-depth information, geological unit assignment, and complete analyses of major ions (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, HCO3−, SO42−, Cl−) with a charge balance < ± 10%, as well as NO3−–N concentrations, 3572 samples from approximately 1000 groundwater wells were selected for this study. Some wells have been sampled multiple times in different years, and all water quality results for these groundwater samples were considered in this study. The majority of water quality data (71%, n = 2532) are from the AHS dataset, followed by AWWID (25%, n = 875), BWWT (3%, n = 95), and GOWN (2%, n = 70) datasets. The sampling dates for groundwater samples ranged from 1960 to 2020, with 76% (n = 2708) of the samples collected between 2000 and 2020 and 24% (n = 864) from 1960 to 1999. The compiled database contains information about water chemistry, isotope composition of NO3− (δ15N and δ18O), well depth, screened intervals of some wells, and the corresponding geological units in which the monitoring and domestic water wells are completed. Samples obtained from water wells screened in bedrock units comprise 68% of the dataset (n = 2433), with a wide variability of water well depths ranging from 2.4 to 500 m with a median of 46 m. The remaining 32% (n = 1139) of the groundwater samples were obtained from water wells completed in surficial sediments with depths ranging from 0.30 to 110 m and a median depth of 12 m.

Data for groundwater sampled at springs was obtained from a compilation of different reports and datasets by the Alberta Geological Survey (Stewart 2014). In the study area (Fig. 1a), approximately 400 springwater samples have been reported, but only 203 were analyzed for NO3− concentrations. Since some springs were sampled multiple times, it was difficult to estimate the exact number of distinct springs. For this study, the 203 spring samples were treated as individual samples. The database includes major ion geochemistry (Ca2+, Na+, Mg2+, K+, Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−, NO3−–N) and pH measurements. However, no isotope data are available for any of the spring samples. No details about sampling protocols are available for the spring database.

Data analysis

The spatial distribution of NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater was evaluated by creating maps of the median concentration in mg/L per Alberta Township System (ATS) that contains at least one water well using ArcGIS Pro 3.1.1. The ATS divides the province into squares of equal size. Each township has a size of ~ 9.6 by 9.6 km (Government of Alberta,2023a. Separate maps were created using samples from wells completed in surficial sediments and bedrock formations to investigate patterns based on the aquifer type. A representativity index (RI) was established for each township to determine the spread of NO3− concentrations around the median based on sample size and descriptive statistics (e.g., interquartile range, median). The coefficient of variation (CV), which was calculated as the ratio of the interquartile range and the median due to the non-normal distribution of NO3− concentrations (Arachchige et al. 2020), was assigned a low CV if the calculated value was below 80% and a high CV if it exceeded that level. Townships with three or fewer groundwater samples were assigned a low RI (hashed township), townships with > 3 samples and low CV represented a high RI (bold township), and townships with > 3 samples but high CV were considered as intermediate RI.

The NO3−–N concentrations that fell below detection limits, referred to as censored values, were imputed (estimated) using the log-ratio and Expectation–Maximisation (EM) algorithm implemented in the zCompositions R package (Palarea-Albaladejo and Martín-Fernández 2015). This method is suitable for handling variables with censored values exceeding 25% of a dataset and that contain multiple detection limits, using a compositional data approach (Aitchison 1982). All statistical analyses were conducted using the imputed censored data, including descriptive statistics and nonparametric statistical tests (Spearman’s rank correlations) to assess bivariate correlations (Helsel et al. 2020). Comparisons among different groups of samples were conducted using either the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon or the Kruskal–Wallis tests (Helsel et al. 2020). An α value of 0.05 is used for each test. All analyses were performed in the R software environment (R Core Team 2021).

Denitrification trends, based on the 1:1 and 2:1 relationship between oxygen and nitrogen isotopes, were determined using an approximation of the Rayleigh equation, δs = δs0 + ε ln C/Co. This equation was applied with known isotopic enrichment factors for denitrification, with ε15N values up to − 20‰ and ε18O values around − 8.0‰ (Mariotti et al. 1988; Clark and Fritz, 1997). To further explore denitrification scenarios under different environmental conditions, various N isotope enrichment factors (ε = − 4, − 9, − 14‰) were modeled using the Rayleigh equation (Mariotti et al. 1988).

Results

Groundwater well samples exhibit a wide variability in NO3−–N concentrations, ranging from below detection limits (0.001–0.25 mg/L) to 300 mg/L in the investigated dataset. Among all samples, 49% (n = 1746) were associated with NO3−–N concentrations below the detection limits. The median NO3−–N concentration was 0.022 mg/L (n = 3572), considering samples both above and below detection limits. In comparison, the median concentration of samples with NO3−–N above the detection limits was 1.5 mg/L (n = 1826), two orders of magnitude higher. In the dataset, including samples with NO3−–N below and above detection limits, 10% (n = 369) of the groundwater samples exceeded the Canadian drinking water guideline or maximum acceptable concentration of 10 mg/L NO3−–N. Descriptive statistics for NO3−–N, other ions, and stable isotope compositions of NO3− (δ15N and δ18O) are provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Information).

A statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed between the median NO3−–N concentration for groundwater samples collected from wells completed in bedrock formations (0.0067 mg/L) and surficial sediments (0.20 mg/L). Additionally, the maximum NO3−–N concentration (246 mg/L) was slightly lower for groundwater collected from bedrock aquifers compared to samples obtained from surficial sediments (300 mg/L, Table S2). Of all samples exceeding the maximum acceptable concentration (n = 369), a higher percentage of groundwater samples (6%, n = 224) was associated with samples from bedrock formations compared to 4% (n = 145) in groundwater samples from surficial sediments. It is important to note that elevated NO3−–N concentrations (≥ 10 mg/L) were prevalent across groundwater samples from aquifers in various geological formations, independent of their lithological composition (fine to medium and coarse-grained compositions, Table S3) and depositional environment (marine and nonmarine), although detected NO3−–N concentrations were less common in groundwater from bedrock aquifers from geological formations associated with marine environments.

Summary statistics for chemical parameters and δ15N and δ18O values of NO3− for groundwater samples from wells completed in surficial sediments and bedrock formations are presented in Table S2. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in the median concentrations of major ions and Fe2+ based on the geological distinction between surficial sediments and bedrock aquifers. Groundwater samples from aquifers in surficial sediments exhibited significantly higher median concentrations (p < 0.05) of Ca2+ (82 mg/L), Mg2+ (42.8 mg/L), K+ (4.5 mg/L), SO42− (322 mg/L), and Fe2+ (0.08 mg/L) compared to samples from bedrock formations, where the median concentrations were as follows: Ca2+ (28.7 mg/L), Mg2+ (12.9 mg/L), K+ (2.5 mg/L), SO42− (280 mg/L), and Fe2+ (0.06 mg/L). Conversely, groundwater samples from bedrock formations displayed significantly higher median concentrations (p < 0.05) of Na+ (327 mg/L), HCO3− (480 mg/L), and Cl− (23.8 mg/L) compared to samples from surficial sediments, where the median concentrations were lower for Na+ (173 mg/L), HCO3− (430 mg/L), and Cl− (20.4 mg/L).

The spatial distribution of median NO3−–N concentrations per township for groundwater samples from surficial sediments and bedrock formations are shown in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. The study area is divided into 547 townships, revealing that nearly half of the townships (41%, n = 227) associated with surficial sediment aquifers exhibit median NO3−–N concentrations ranging from < 2 to 100 mg/L, while the remaining 320 townships had no available NO3−–N concentration data (Fig. 2a). Within the subset of 227 townships, 38 townships (17%) displayed median NO3−–N concentrations ≥ 10 mg/L, dispersed throughout the study area without discernible spatial trends, observed in areas under both irrigated and non-irrigated land, as well as areas with and without considerable CFO activities. The majority of the townships (63%, n = 143) have small sample sizes (n ≤ 3) of groundwater from surficial sediments, reflecting a low representativity index (RI) depicted as hatched areas in Fig. 2a. Only 14 (6%) townships show a high RI with larger sample sizes (> 3) and low CV (< 80%).

Fig. 2.

Spatial distribution of median NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater samples per township: a wells completed in surficial sediments, b wells in bedrock formations, and c NO3−–N concentrations in spring samples in Southern Alberta. The Representativity Index (RI) of the median NO3−–N concentration per township is depicted as follows: hashed squares indicate low RI, bold-outlined squares indicate high RI, and squares with no additional symbology indicate intermediate RI. Histograms of NO3−–N concentrations for individual groundwater samples analyzed in this study are shown to the right of the maps

For townships associated with bedrock aquifers, the median NO3−–N concentration per township exhibits similar ranges to those in surficial sediment aquifers (< 2 mg/L to 100 mg/L), covering a larger number of townships (64%, n = 350). However, in bedrock aquifers, only 14 townships (4%) out of 350, exhibited median NO3−–N concentrations ≥ 10 mg/L, observed predominantly in areas adjacent to major irrigation districts with a high manure index (> 0.5, Fig. 1b) near Lethbridge and west of Medicine Hat (Fig. 2b). Consistently low median NO3−–N concentrations (< 2 mg/L) per township were observed in groundwater from bedrock aquifers towards the southeast and northwest corners of the study area. About half of the townships (53%, n = 184) yielding groundwater from bedrock aquifers exhibit small sample sizes (n ≤ 3), indicating a low RI (Fig. 2b), while 23 townships (7%) had a high RI.

Descriptive statistics were also calculated for NO3−–N concentrations of groundwater samples below irrigated and non-irrigated land based on groundwater samples from surficial sediments and bedrock formations (Table S4). The results indicate statistically higher median NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater samples under non-irrigated land relative to land under major irrigation districts (p < 0.005) for both groundwater samples from surficial sediment and bedrock aquifers. The results also show that a smaller proportion of samples (< 20%) were collected under irrigated land compared to non-irrigated land. Median NO3−–N concentrations per township for groundwater samples in surficial sediments and bedrock aquifers did not correlate (p > 0.05) with the average crop area and manure production per township (Fig. S2).

Nitrate concentrations in spring samples

Spring samples containing NO3−–N also had a wide range of concentrations from 0.02 to 216 mg/L (Fig. 2c; Table S5). The median NO3−–N concentration for spring samples (2.9 mg/L) was higher compared to groundwater from water wells. A larger percentage of spring samples (22%, n = 44) exceeded the drinking water guideline of 10 mg/L as NO3−–N relative to samples from water wells (10%). Elevated NO3−–N concentrations (≥ 10 mg/L) in spring samples were predominantly observed in the southwest of the study area, south of Lethbridge, and near Medicine Hat (Fig. 2c), aligning closely with townships exhibiting elevated median NO3−–N concentrations for groundwater samples sourced from surficial sediments. Conversely, most spring samples with low NO3− levels were situated in townships where the median NO3−–N concentration for groundwater samples sourced from bedrock formations was < 10 mg/L.

Correlation analysis

Correlation analysis was conducted to better understand factors influencing NO3− contamination of groundwater from aquifers in surficial sediments and bedrock formations within the study area (Fig. S3), considering nine chemical parameters (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, HCO3−, SO42−, Cl−, NO3−–N, Fe2+). Spearman (ρ) correlations revealed consistent moderate positive correlations (p < 0.001, ρ = 0.2–0.3) between NO3−–N and Ca2+, Mg2+, and K+ concentrations across both groups of groundwater samples. Notably, in groundwater samples from surficial sediments, a moderate positive correlation (p < 0.001, ρ = 0.2) between NO3−–N and Cl− concentrations was also observed (Fig. S3a), while no correlation (p > 0.05) between NO3−-N and Cl− was found in samples from bedrock formations (Fig. S3b). No clear correlations were observed between NO3−–N and SO42− concentrations for groundwater samples in both surficial sediments and bedrock. In contrast, both sample groups show moderate negative correlations (p < 0.001, ρ = 0.2–0.5) between NO3−–N and Fe2+, Na+, and HCO3− concentrations (Fig. S3). These correlation patterns suggest that hydrochemical groundwater facies, or water types, characterized by Ca–Mg–HCO3 (having elevated Ca + Mg/Na) are often associated with elevated NO3−–N concentrations, whereas Na–HCO3 and Na–HCO3–Cl water types (having low Ca + Mg/Na) tend to exhibit lower NO3−–N concentrations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Depth (m) vs. Ca + Mg to Na mass ratio in groundwater samples associated with surficial sediments (blue circles) and bedrock formations (red circles). The size range represents the NO3−–N concentrations of the samples

Water well depth and nitrate concentrations

Variations in NO3−–N concentrations across depth intervals for groundwater samples sourced from surficial sediments and bedrock formations are shown in Fig. 4a and b, respectively. Most of the samples (91%, n = 2201) associated with bedrock aquifers were obtained from depths shallower than 150 m, while nearly all groundwater samples from surficial sediments (99%, n = 1134) were retrieved from depths < 75 m, reflecting common drilling depths for domestic and drinking water wells. Overall, NO3−–N was present at all depth intervals, but elevated NO3−–N concentrations were consistently observed at shallower depths < 30 m, decreasing as depth increases.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of NO3−–N concentrations at different depth intervals for groundwater samples obtained from wells completed in surficial sediments (a) and bedrock formations (b) in Southern Alberta. The blue values indicate the percentage of samples with NO3−–N concentrations above detection limits. The red dashed line represents the maximum acceptable concentration of 10 mg/L NO3−–N for drinking water in Canada (Health Canada 2013). Boxes represent 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile values, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within Q1/Q3 − / + 1.5 × IQR, and closed circles represent outliers beyond that range; the star symbol indicates the mean NO3−–N concentrations

Nitrate concentrations in groundwater samples obtained from wells completed in surficial sediments and bedrock formations show an inverse correlation with depth, having similar Spearman values (p < 0.05, ρ = − 0.31). Maximum groundwater NO3−–N concentrations of 300 and 246 mg/L occurred at 20–30 m and 10–20 m depth intervals in wells completed in surficial sediments and bedrock formations, respectively (Fig. 4a, b). Median NO3−–N concentrations > 0.3 mg/L were observed at depths between 0 and 20 m as well as 0 and 30 m for groundwater samples from aquifers in surficial sediments and bedrock formations, respectively. In contrast, median NO3−–N concentrations < 0.01 mg/L were predominantly observed at depths greater than 30 and 40 m. Additionally, more than 50% of samples from depths exceeding 30 m had NO3−–N concentrations below detection limits.

The highest percentage of groundwater samples from surficial sediments (19%, n = 88) surpassing the maximum acceptable concentration of 10 mg/L NO3−–N occurred at the shallowest depth (0–10 m). In contrast, for groundwater samples from bedrock formations, the largest proportion (25%, n = 63) of samples surpassing the maximum acceptable concentration threshold was observed at depth intervals between 10 and 20 m. Interestingly, 90 groundwater samples collected from wells completed in bedrock formations exceeded the maximum acceptable concentration at depths > 30 m compared to only four groundwater samples from surficial sediments.

Isotopic composition of nitrate (δ15N and δ.18O)

Out of 70 groundwater samples obtained from the GOWN monitoring wells (n = 26), 59 samples had NO3−–N concentrations < 0.1 mg/L yielding insufficient NO3−– to conduct isotope analyses or were obtained before 2006. Therefore, only 11 groundwater samples with sufficient NO3−–N concentrations were analyzed for nitrogen and oxygen isotope ratios of NO3−–N (Tables S1, S2). Samples with sufficient NO3−–N concentrations were collected from six different GOWN monitoring wells screened in both bedrock and surficial sediments with depths ranging from 4.2 to 73.2 m, with most samples from shallow depths < 30 m. The δ15N–NO3− values ranged from + 6.2 to + 40.6‰ and δ18O–NO3− values from − 11.1 to + 25.9‰ (Fig. 5; Table S1). The median δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3 values were + 19.9‰ and + 3.5‰, respectively. Specifically, samples from bedrock aquifers (n = 7) had δ15N–NO3− values ranging from + 6.2 to + 40.6‰ and δ18O–NO3− from − 11.1 to + 25.9‰ (Fig. 5). In contrast, samples from wells completed in surficial sediments (n = 4) had a narrower δ15N–NO3− range from 11.9 to 23.1‰ and δ18O–NO3− values varying from − 8.0 to + 4.2‰ (Fig. 5). No statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in δ15N–NO3− or δ18O–NO3− values between groundwater samples obtained from surficial sediments and bedrock aquifers. None of the spring samples were analyzed for N and O isotope ratios of NO3−–N.

Fig. 5.

δ18O vs. δ15N values of nitrate in groundwater from monitoring wells completed in bedrock formations (circles) and surficial sediments (triangles) from Southern Alberta. Numbers from 1 to 7 indicate the individual GOWN wells and repeated numbers represent replicate samples from the same well. Boxes indicate ranges of stable isotope ratios of nitrate sources (Kendall et al. 2007; Proemse et al. 2012; Kruk et al. 2020). The solid and dashed blue arrows represent denitrification lines of 1:1 and 2:1 ratio, respectively. The legend shows the hydrochemical facies associated with each groundwater sample

Discussion

In this section, we explore the patterns, drivers, and implications of nitrate contamination in groundwater in the southern part of Alberta. Utilizing the geochemical and nitrate isotope results presented in the previous section, we discuss the influence of agricultural activities, geological conditions, and land use practices on nitrate concentrations and sources in shallow aquifers.

Nitrate variations in groundwater of agricultural areas

Nitrate–N concentrations in groundwater from wells and springs across Southern Alberta exhibit large variability, ranging from below detection limits (as low as < 0.001 mg/L) to over 100 mg/L. However, few studies have reported NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater > 50 mg/L, i.e., the largest groundwater NO3− study in the United States reported concentrations < 50 mg/L in agricultural areas (Burow et al. 2010). In contrast, higher NO3−–N concentrations have been observed in contaminated agricultural regions, such as Spain, where NO3−–N concentrations > 100 mg/L have been documented (Menció et al. 2016). In Alberta, NO3−–N concentrations > 50 mg/L in groundwater are consistent with findings from various local studies conducted in Southern Alberta (Hendry et al. 1984; Rodvang et al. 2004; Kohn et al. 2016). Notably, this study at a regional scale revealed that 10% of groundwater samples and 22% of spring samples exceeded the Canadian drinking water guideline for NO3−–N. Surficial sediment aquifers appear more susceptible to NO3− contamination compared to bedrock aquifers, as evidenced by the higher median NO3−–N concentration (0.2 mg/L, Table S2) in groundwater from surficial sediment aquifers. Township-level analysis (Fig. 2) further supported this observation, showing a larger number of townships (n = 38) with median NO3−–N concentrations exceeding 10 mg/L in groundwater from surficial sediments compared to only 14 townships in groundwater from bedrock formations.

In bedrock aquifers, elevated NO3−–N concentrations were more prevalent in bedrock associated with nonmarine environments rather than in marine environments (Table S3). The difference in NO3−–N relative to bedrock aquifer geology may be attributed to reduced agricultural activity in areas overlying marine bedrock formations, particularly in the southeastern corner of the study area, characterized by Lea Park/Pakowki sediments (Fig. 1c). Another explanation for the low NO3−–N concentrations in marine shales is the presence of pyrite, which promotes autotrophic denitrification in these aquifer/aquitard systems (Korom 1992; Robertson et al. 1996; Jørgensen et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2022).

The spatial distribution of elevated NO3−–N concentrations in spring samples and observed groundwater NO3−–N concentration hotspots in the western part of the study area (near Lethbridge, Fig. 2) coincides with regions characterized by a dense presence of CFOs (Fig. 1b), suggesting that elevated NO3− could partially originate from these activities. Although there was no statistical correlation between the median NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater and the median manure index per township (Fig. S2) in areas with CFOs, intensive manure applications to agricultural land are common (Kohn et al. 2020). Additionally, the spatial distribution of spring samples with NO3−–N above 10 mg/L in and near townships with elevated median groundwater NO3−–N concentrations in surficial sediments suggests possible local flow systems between these particular surficial sediment aquifers and springs (Fig. 2).

The absence of significant correlations between median groundwater NO3−–N concentrations and average manure production per township (Fig. S2) implies that while manure production and its subsequent spreading on agricultural land may contribute to the elevated groundwater NO3− concentrations of the study area (Kohn et al. 2016; Kyte et al. 2023), other factors likely play an important role in explaining the variability of NO3−–N concentrations in both groundwater and spring samples. It is important to note that there is a low density of groundwater quality samples in the regions of Southern Alberta with high CFO density (e.g., north of Lethbridge). Moreover, the statistically higher NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater samples from areas outside major irrigation districts, compared to samples obtained under irrigation districts (Table S4), indicate a potential dilution effect resulting from the use of irrigation water sourced from rivers with low NO3− concentrations, as indicated by Dubrovsky et al. (2010) in some areas of the USA. For instance, some rivers used as sources of irrigation water in Southern Alberta commonly exhibit NO3−–N concentrations < 1 mg/L (Rock and Mayer 2004a, b; Kruk et al. 2020), which supports this hypothesis. Nonetheless, these results contrast the findings by Kyte et al. (2023), who observed higher NO3− concentrations in groundwater under irrigated land than under non-irrigated land at an experimental site in Southern Alberta. The authors focused their analysis on shallow groundwater, typically at depths < 6 m, whereas the median groundwater depths in this regional study exceeded 10 m, with < 7% (n = 258) of the total samples having depths of less than 6 m. This discrepancy suggests that the influence of irrigation on groundwater NO3− concentrations may be localized in shallow aquifers, although further data from shallow wells would be necessary to make better comparisons to the findings of Kyte et al. (2023).

Analysis of NO3−–N concentrations relative to depth revealed that the majority of samples (74%, n = 274) exceeding the maximum acceptable concentration for NO3−–N (10 mg/L) were found at depths shallower than 30 m (Fig. 4). The finding of elevated NO3− concentrations in shallow aquifers is consistent with similar studies conducted in the USA (Dubrovsky et al. 2010; Burow et al. 2010) and Southern Alberta (Hendry et al. 1984; Rodvang et al. 2004, 2014; Kohn et al. 2020). The high NO3− concentrations at depths < 30 m align with the maximum depth of the regional redoxcline, which developed in shallow sediment/bedrock during the mid-Holocene due to lower water table levels (Rodvang and Simpkins 2001), and the potential geochemical linkages are discussed in Sect. 5.4. A considerable proportion of groundwater samples (26%, n = 95) with NO3−–N concentrations > 10 mg/L were also identified at greater depths (up to 150 m), particularly in samples associated with bedrock formations. The elevated NO3−–N concentrations at greater depths contrast previous observations in Southern Alberta, where elevated NO3−–N concentrations were restricted to aquifer depths < 20 m usually associated with surficial sediments, including tills (Hendry et al. 1984; Kohn et al. 2020). Therefore, this broader study shows that NO3− contamination may extend deeper into the aquifers than previously recognized, highlighting the potential for a more widespread and complex groundwater contamination issue in some regions.

Geochemical indicators associated with nitrate in groundwater

Geochemical indicators provide crucial insights into the underlying processes driving NO3− variability in groundwater (Menció et al. 2016). Nitrate concentrations generally are highest in groundwater with a Ca + Mg to Na mass ratio > 1 at depths shallower than 30 m (Fig. 3), predominantly in surficial sediment aquifers consistent with observations from Fig. 4. Conversely, lower Ca + Mg/Na, are usually associated with lower NO3−–N concentrations, predominantly at depths greater than 50 m in groundwater sourced mainly from bedrock aquifers. The low NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater with a low Ca + Mg/Na suggest either conditions favorable for NO3− removal or a limited to negligible impact of anthropogenic NO3− on geochemically evolved groundwater. Previous studies in Alberta have identified that Na-rich waters with low Ca/Na are primarily found in evolved groundwaters under reducing conditions, while Ca–Mg–HCO3 facies with high Ca/Na indicate freshly recharged water sources (Grasby et al. 2000; Huff et al. 2012; Humez et al. 2016; Ruff et al. 2023). Therefore, the high Ca to Na mass ratios observed in some shallow aquifers reveal that freshly recharged waters especially in the uppermost 30 m of surficial sediment aquifers are most likely to be associated with NO3− inputs from agriculture, while more chemically evolved groundwater under increasingly reducing conditions, facilitates NO3− removal via denitrification or may have never been impacted by anthropogenic NO3− (Burow et al. 2010). Elevated NO3−–N concentrations (> 10 mg/L) in Na-rich groundwaters, especially at depths greater than 30 m, may suggest the direct entry of NO3− from surface operations into aquifers via infiltration through poorly sealed wells and leaky well casings (Kohn et al. 2021).

Sources of nitrate in groundwater samples

The δ15N and δ18O values of NO3− obtained from groundwater samples revealed three primary NO3− sources, which include the mineralization of soil organic nitrogen followed by nitrification, the nitrification of ammonium/urea-containing fertilizers in soils, and manure (Fig. 5). Source signatures of δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− values were derived from existing literature for NO3− in atmospheric deposition (Proemse et al. 2012), and δ15N values for NH4+ fertilizers and δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− values for sewage and cattle manure were obtained from a previous study in Southern Alberta by Kruk et al. (2020). However, sewage was considered to have a minimal contribution to groundwater nutrient levels compared to cattle manure, given the presence of approximately 800,000 cattle and calves in the County of Lethbridge, outnumbering the approximately 11,000 inhabitants in the same county, which is the most populous area in this study (Government of Alberta 2023d).

The lowest δ15N–NO3− value of 6.2‰ (Fig. 5), observed in one of the groundwater samples associated with a bedrock aquifer, corresponded to the lowest NO3−–N concentration of 0.39 mg/L suggesting that nitrification of ammonium, potentially derived from soil organic matter (SOM), dissolved organic nitrogen, or another ammonium source was likely the NO3− formation process. This particular monitoring well (Well#1) is situated in the southeastern corner of the province, aligning with the spatial distribution of NO3− in groundwater, which suggests reduced agricultural influence in this part of the study area. The surrounding land in this region had a low manure index of < 0.5, with a small average area of cultivated land per township of < 1 km2 (Fig. 1).

In contrast, groundwater samples from bedrock and surficial sediment aquifers, displaying δ15N–NO3− values > 8.5‰ (Fig. 5), were commonly associated with NO3−–N concentrations ranging from 1.4 to 300 mg/L, indicative of manure as the primary source of NO3−. Notably, some of the wells yielding groundwater with the highest NO3−–N concentrations (> 50 mg/L), identified as manure-derived based on isotope data, were found near Lethbridge. Furthermore, groundwater samples exhibiting δ15N–NO3− values > 8.5‰ were typically collected from depths < 20 m. It is important to note that, while isotopic data provide valuable insights, more data would be required to better constrain the specific sources and processes contributing to NO3− occurrence in groundwater.

Correlations of concentrations of major ions and NO3−–N in groundwater samples further support the manure source associated with elevated NO3−–N concentrations and, to a lesser extent, synthetic fertilizer sources in Southern Alberta (Fig. S3). Elevated concentrations of Na+, K+, Cl−, SO42−, and NO3− in groundwater are often attributed to agricultural activities, including the use of synthetic fertilizers and manure (Koh et al. 2010; Menció et al. 2016). Positive correlations (p < 0.0001, ρ = 0.2–0.3) between NO3−–N, K+, and Cl− concentrations ("Sources of nitrate in groundwater samples" section and Fig. S3) in groundwater samples, notably from surficial sediment aquifers, suggest similar sources for these constituents, likely driven by a combination of synthetic fertilizer and manure applications. For instance, the application of nitrogen-based fertilizers (e.g., liquid urea), potassium chloride (KCl), and ammonium sulfate have been reported especially on fields with forage, fruits, vegetables, and canola crops in Alberta (Smith et al. 2019; Statistics Canada 2022).

In addition to synthetic fertilizers, manure application can contribute to K+ and Cl− inputs to groundwater. Although K+ concentrations in groundwater after manure application were not reported, Olson et al. (2003) noted higher NO3−, K+, and Cl− concentrations in manure-amended soils compared to those without manure, indicating the potential leaching of NO3−, K+, and Cl− into groundwater. Other localized studies (Olson et al. 2009; Kohn et al. 2021; Kyte et al. 2023) have also identified simultaneous increases in NO3−–N and Cl− concentrations in groundwater affected by manure spreading, earthen manure storage, and improperly sealed or poorly constructed wells in close proximity to dairy pens or temporary manure stockpiles in Alberta.

To further investigate NO3− sources and denitrification in groundwater, NO3−/Cl− was plotted against Cl− concentrations for samples from GOWN monitoring wells (Fig. S4). Since Cl− is a conservative tracer, it can be used as an indicator of geochemical processes as well as contamination sources (Liu et al. 2006). Generally, synthetic N-containing fertilizers increase NO3− concentrations without significant increases in Cl− concentrations, resulting in high NO3−/Cl− (Liu et al. 2006; Su et al. 2020). In contrast, sewage and manure sources result in low NO3−/Cl− but with elevated Cl− concentrations (Liu et al. 2006; Yue et al. 2017; Su et al. 2020). Groundwater samples from the GOWN wells with high NO3−/Cl− (> 0.01) and low Cl− concentrations (< 3 mmol/L) indicate predominantly NO3− contributions from mineralization of soil organic nitrogen followed by nitrification, or nitrification of ammonium or urea-based synthetic fertilizers (Fig. S4), where the yellow diamond represents the sample with a δ15N–NO3− value of 6.2‰ related to mineralization of soil organic nitrogen followed by nitrification (Fig. 5). In contrast to the expected low NO3−/Cl− for groundwater samples impacted by manure, samples from the GOWN wells revealed high NO3−/Cl− (> 0.01) with Cl− concentrations generally > 3 mmol/L. Manure as the dominant NO3− source is supported by δ15N–NO3− values > 8.5‰ shown as blue diamonds (Fig. S4). Groundwater samples with a low NO3−/Cl− < 0.01 mg/L indicate denitrification, which is supported by δ15N–NO3− values > 40‰ and δ18O–NO3− values > 20‰ of the GOWN samples (red circle). The results agree with the denitrification trend in core extracts from surficial sediments with NO3−/Cl− below 0.1 in Southern Alberta (Bourke et al. 2015). It is also possible that the lower NO3−/Cl− and elevated Cl− concentrations indicate mixing with deeper and more saline waters, decreasing the NO3−–N concentrations while increasing Cl− concentrations in some groundwater samples (McCallum et al. 2008).

The role of denitrification affecting the concentration and N and O isotope ratios of nitrate

The isotopic data analysis for NO3− reveals the occurrence of denitrification in a small number of samples, observed in Figs. 5 and 6. Denitrification typically occurs in low-oxygen or oxygen-depleted environments when microorganisms reduce NO3−, leading to the production of N2 or N2O (Kendall 1998). The observed trends in Figs. 5 and 6, characterized by an increase in both δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− values coupled with a simultaneous decrease in residual NO3−–N concentrations, are consistent with N and O isotope fractionation during denitrification as observed in previous studies conducted in Southern Alberta (Kyte et al. 2023). Groundwater samples exhibiting δ15N–NO3− above + 40‰ associated with low NO3−–N concentrations are influenced by denitrification as observed in some groundwater samples from bedrock aquifers (Fig. 6). The groundwater sample with the highest δ15N–NO3− (+ 40‰) and δ18O–NO3− (+ 26‰) values and a low NO3−–N concentration (< 0.5 mg/L) was obtained from a depth > 50 m from a monitoring well completed in the Bearpaw Formation, located towards the southwest of the study area. Denitrification trends (Fig. 6) indicate that several samples with δ15N–NO3− values > 20‰ are likely influenced by partial denitrification, characterized by low N isotope enrichment factors between − 4 and − 9. Denitrification leads to the enrichment of 15N in the remaining NO3−, as NO3−–N concentrations decrease to < 0.5 mg/L in some cases, making the identification of NO3− sources based on stable isotope fingerprinting more challenging (Chang et al. 1999).

Fig. 6.

Theoretical evolution of δ15N–NO3− values and NO3−–N concentrations. Blue arrows represent theoretical evolution during denitrification for a source A (SA) with a NO3−–N concentration of 300 mg/L and a δ15N–NO3− of 18‰ with N isotope enrichment factors of ε = − 4‰ (dashed blue line), ε = − 9‰ (dotted blue line), and ε = − 14‰ (solid blue line). Numbers from 1 to 7 indicate the individual GOWN wells and repeated numbers represent replicate samples

The negative correlation between NO3−–N and dissolved Fe2+ concentrations (Figs. S3, S5) also suggests the influence of redox conditions on NO3− concentrations in groundwater, supporting a redox sequence favoring NO3− removal followed by the appearance of dissolved iron in aquifers. This sequence involves a series of reactions initiated by oxygen depletion, followed by denitrification and subsequent reduction of Fe(III) in minerals to Fe2+ as groundwater becomes increasingly reducing (Appelo and Postma, 2005). Figure S5 illustrates that at elevated NO3−–N concentrations above 10 mg/L, Fe2+ concentrations are typically below 0.8 mg/L, contrasting with elevated Fe2+ concentrations of up to 40 mg/L at NO3−–N concentrations < 2 mg/L. Within the regional redoxcline in surficial sediments and bedrock, reduced gray sediments, signifying the presence of Fe(II) minerals, are typically found at depths of approximately 4–25 m (Hendry et al. 1984; Rodvang and Simpkins 2001; Grasby et al. 2008). Microbially mediated denitrification coupled with Fe(II) oxidation (Liu et al. 2019), may also contribute to the observed decrease in NO3−–N concentrations at depths > 10–30 m.

Despite the valuable insights gained regarding the sources and fate of NO3− in shallow aquifers, several challenges with the utilized datasets were identified. One limitation is the lack of key chemical parameters, such as concentrations of DO, Mn2+, and ammonium (NH4+), for most of the groundwater samples collected from domestic water wells. The absence of these parameters hinders a more comprehensive understanding of redox conditions, which are crucial for elucidating nitrogen transformation processes that influence NO3−–N concentrations and isotopic signatures. Additionally, the dataset would benefit from more extensive isotopic analyses of NO3−, particularly for groundwater samples across the intensively used agricultural areas of Southern Alberta, especially at shallow depths (< 30 m). The absence of repeated sampling at specific sites and depths further limits the ability to accurately assess the temporal evolution of aqueous geochemistry parameters and the isotopic composition of NO3−.

Another challenge of the study arises from the inherent nitrogen transformation processes in the aquifers. Nitrogen compounds in groundwater samples may be affected by several nitrogen transformation processes, such as nitrification, denitrification, and ammonium oxidation, which can have additive or contrasting isotope effects on the δ15N and δ1⁸O values of NO3−. These processes can compromise to some extent the ability to conclusively identify the sources of groundwater NO3−–N especially if δ15N values of NO3− vary between + 4 and + 8‰.

Despite these shortcomings, this study demonstrates that the joint evaluation of aqueous geochemistry and stable isotope data in concert with land use and geological information is a powerful tool to identify NO3− sources and N cycling processes in groundwater at regional scales while integrating historical and current datasets from different sources.

Conclusions

Our findings confirmed the hypothesis that elevated NO3−–N concentrations are predominantly observed in shallow aquifers (< 30 m), with 10% (n = 369) of all groundwater samples exceeding the Canadian maximum acceptable concentration of 10 mg/L for NO3−–N. Elevated NO3−–N concentrations were most commonly observed in surficial sediment aquifers associated with Ca–Mg–HCO3 water types, indicative of recently recharged groundwater. However, NO3− contamination was also detected at greater depths than previously recognized, extending as deep as 150 m in some regions, suggesting vertical migration of NO3− that needs further investigation. Deeper aquifers generally exhibited lower NO3−–N concentrations and geochemically evolved water types (e.g., Na–HCO3 and Na–HCO3–Cl), reflecting conditions more favorable for denitrification and natural attenuation processes that have the potential to remove NO3−.

The hypothesis that irrigated areas would exhibit higher NO3− concentrations in groundwater was rejected, as no significant difference was observed between irrigated and non-irrigated areas. This finding may imply that irrigation practices do not affect NO3− concentrations across all groundwater depth ranges investigated in this study. Areas with high NO3−–N concentrations in shallow groundwater were observed to spatially overlap with regions of intense CFOs. However, statistical analyses revealed no significant correlation between manure production and NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater at the township scale. This lack of a clear relationship is likely influenced by substantial data gaps in regions with high CFO density (e.g., north of Lethbridge). These gaps hinder the ability to accurately assess the role of CFOs in groundwater NO3− contamination, underscoring the need for enhanced groundwater monitoring in these areas.

Combining NO3−–N concentration data and δ15N and δ18O values of NO3− revealed three sources in groundwater: (1) mineralization of soil organic nitrogen followed by nitrification, (2) nitrification of ammonium/urea-containing fertilizers in soils, and (3) manure. Although stable isotope data (δ15N and δ18O) were limited, the isotopic composition of NO3−–N with δ15N values above + 8‰ associated with the manure source, when interpreted alongside other chemical parameters and NO3− to Cl− ratios, provided support for the conclusion that elevated NO3−–N concentrations in groundwater, reaching up to 300 mg/L, were predominantly influenced by manure-derived nitrate. Nitrate derived from synthetic fertilizers was also identified as a secondary source, evidenced by positive correlations between NO3−–N and concentrations of K+ and Cl− in groundwater.

Geological, geochemical, and stable isotope data showed that conditions become increasingly favorable for denitrification with increasing aquifer depth and below the regional redoxcline, a process that actively removes NO3− from groundwater. It was also observed that NO3−-N concentrations in bedrock aquifers varied depending on the geologic origin of the formations, with aquifers in nonmarine environments exhibiting higher NO3−–N concentrations compared to those associated with marine formations. This supports the hypothesis that the presence of pyrite in marine shales facilitates autotrophic denitrification, enhancing the removal of NO3− nitrate from groundwater in these bedrock aquifers.

A key finding of this study was that 49% (n = 1746) of all groundwater samples were associated with NO3−–N concentrations below the detection limits. This raises questions about whether these groundwater samples were never affected by NO3− inputs from agricultural or other sources, or if NO3− had entered the aquifers and was subsequently denitrified. The methods used in this study cannot conclusively answer this question. Future research, potentially incorporating microbiological techniques to assess the abundance of denitrifying bacteria, in combination with dissolved gas geochemistry (e.g., N2O abundances) and groundwater age dating, may provide further insights.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the field sampling team members, including Joanna Borecki from Alberta Environment and Protected Areas (EPA), for their efforts in sampling monitoring water wells. We also acknowledge the Alberta Geological Survey (AGS), including Jessica Liggett for their contributions to the groundwater geological assignments for samples from the compiled unified database. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the constructive feedback from the editor and two anonymous reviewers, which resulted in significant improvements to the final version of this manuscript.

Author contributions

IP, PH, CM, and BM were involved in the study’s conception and design. LW and MN contributed to data acquisition. IP and PH prepared the data used in the study. IP, PH, CM, and BM contributed to the data analysis. IP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BM, CM, and PH reviewed and edited all manuscript versions. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was enabled through generous financial support from the Alberta Innovates Water Innovation Program (AI-WIP), which is gratefully acknowledged. The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) provided further financial support for this investigation in the form of a Discovery Grant to Bernhard Mayer. Funding was also provided by Alberta Environment and Protected Areas (EPA) to BM. Isabel Plata gratefully acknowledges scholarship support from the University of Calgary and the Ministerio de Ciencia Tecnologia e Innovacion (MinCiencias, Colombia).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study can be found at:

Springs dataset: https://ags.aer.ca/publication/dig-2014-0025

AHS domestic water wells—routine chemistry: https://open.alberta.ca/opendata/domestic-well-water-quality-in-alberta-routine-chemistry#summary

AHS domestic water wells—trace elements: https://open.alberta.ca/opendata/domestic-well-water-quality-in-alberta

AWWID and BWWT datasets: https://groundwater.alberta.ca/WaterWells/d/

GOWN dataset: https://www.alberta.ca/lookup/groundwater-observation-well-network.aspx.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- ABMI (2019) Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute and Alberta Human Footprint Monitoring Program. ABMI human footprint inventory (HFI) for Alberta 2019 (version 1.0). Geodatabase. ABMI

- Aitchison J (1982) The statistical analysis of compositional data. J R Stat Soc B 44(2):139–160. 10.1111/J.2517-6161.1982.TB01195.X [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Agriculture Food and Rural Development, AAFRD (2005) Agricultural land resource atlas of Alberta, 25 maps, 2nd edn. Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, Resource Management and Irrigation Division, Conservation and Development Branch, Edmonton. https://www.alberta.ca/agricultural-land-resource-atlas-of-alberta

- Alberta Health (2014) Domestic well water quality in Alberta, 2002–2008, characterization. Physical and chemical testing. Alberta Health

- AMEC (2009) South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta: water supply study. Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development, Lethbridge [Google Scholar]

- Arachchige CNPG, Prendergast LA, Staudte RG (2020) Robust analogs to the coefficient of variation. J Appl Stat 49(2):268–290. 10.1080/02664763.2020.1808599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson LA, Liggett JE, Hartman G, Nakevska N, Mei S, MacCormack KE, Palombi D (2017) Regional geological and hydrogeological characterization of the Calgary–Lethbridge Corridor in the South Saskatchewan Regional Planning Area. AER/AGS Report 91. Alberta Energy Regulator

- Atkinson LA, Pawley SM, Andriashek LD, Hartman GMD, Utting DJ, Atkinson N (2020) Sediment thickness of Alberta, Version 2, AER/AGS Map 611, Scale 1:1,000,000. Alberta Energy Regulator/Alberta Geological Survey

- Bourke SA, Turchenek J, Schmeling EE, Nessa Mahmood F, Olson BM, Jim Hendry M (2015) Comparison of continuous core profiles and monitoring wells for assessing groundwater contamination by agricultural nitrate. Groundw Monit Remediat 35(1):110–117. 10.1111/gwmr.12104 [Google Scholar]

- Bourke SA, Iwanyshyn M, Kohn J, Jim Hendry M (2019) Sources and fate of nitrate in groundwater at agricultural operations overlying glacial sediments. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 23(3):1355–1373. 10.5194/hess-23-1355-2019 [Google Scholar]

- Burow KR, Nolan BT, Rupert MG, Dubrovsky NM (2010) Nitrate in groundwater of the United States, 1991–2003. Environ Sci Technol 44(13):4988–4997. 10.1021/ES100546Y/SUPPL_FILE/ES100546Y_SI_001.PDF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S, Caraco NF, Correll DL, Howarth RW, Sharpley AN, Smith VH (1998) Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorus and nitrogen. Ecol Appl 8(3):559–568 [Google Scholar]

- Casciotti KL, Sigman DM, Galanter Hastings M, Böhlke JK, Hilkert A (2002) Measurement of the oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate in seawater and freshwater using the denitrifier method. Anal Chem 74(19):4905–4912. 10.1021/AC020113W/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/AC020113WF00005.JPEG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CCY, Kendall C, Silva SR, Battaglin WA, Campbell DH (1999) Nitrate stable isotopes: tools for determining nitrate sources among different land uses in the Mississippi River Basin. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 56(10):1856–1864. 10.1139/f99-126 [Google Scholar]

- Dawson FM, Evans C, Marsh R, Power B (1994) Uppermost cretaceous and tertiary strata of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. In: Geological atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. Alberta Research Council, Edmonton, pp 387–406

- Dorff E, Beaulieu MS (2014) Feeding the soil puts food on your plate, no. 96. Statistics Canada

- Downing DJ, Pettapiece WW (2006) Natural regions and subregions of Alberta. Publication No. T/852. Natural Regions Committee, Government of Alberta

- Dubrovsky NM, Burow KR, Clark GM, Gronberg JM, Hamilton PA, Hitt KJ, Mueller DK et al (2010) The quality of our nation’s waters—nutrients in the nation’s streams and groundwater, 1992–2004. US Geological Survey Circular 1350, No. 2. Pubs.Usgs.Gov. https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1350/

- Fenton MM, Schreiner BT, Nielsen E, Pawlowicz JG (1994). Quaternary geology of the Western Plains. In: Geological atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. Alberta Research Council, pp 413–420

- Fitzgerald D, Chanasyk DS, Neilson RD, Kiely D, Audette R (2001) Farm well water quality in Alberta. Water Qual Res J Can 36(3):565–588. 10.2166/wqrj.2001.030 [Google Scholar]

- Forrest F, Rodvang SJ, Reedyk S, Wuite J (2006) A survey of nutrients and major ions in shallow groundwater of Alberta’s agricultural areas. In: Prepared for the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration Rural Water Program, Project Number: 4590-4-20-4. Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, Edmonton, p 116

- Galloway JN, Schlesinger WH, Levy H, Michaels A, Schnoor JL (1995) Nitrogen fixation: Anthropogenic enhancement–environmental response. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 9(2):235–252. 10.1029/95GB00158 [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta (2021a) Alberta water wells web application. Government of Alberta. Alberta.Ca. https://www.alberta.ca/alberta-water-wells-web-application.aspx

- Government of Alberta (2021b) Groundwater—overview: Alberta. Government of Alberta. https://www.alberta.ca/groundwater-overview.aspx

- Government of Alberta (2023a) Alberta Township survey (ATS). Government of Alberta. https://www.alberta.ca/assets/documents/energy-alberta-township-survey.pdf.

- Government of Alberta (2023b) Groundwater Observation Well Network. Government of Alberta. https://www.alberta.ca/lookup/groundwater-observation-well-network.aspx

- Government of Alberta (2023c) Irrigation strategy. Government of Alberta. Alberta. https://www.alberta.ca/irrigation-strategy.aspx

- Government of Alberta (2023d) Lethbridge County—total cattle and calves. Government of Alberta. https://regionaldashboard.alberta.ca/region/lethbridge-county/total-cattle-and-calves/#/

- Government of Canada (2023) Overview of Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector. Government of Canada. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/sector/overview

- Grasby SE, Hutcheon I, Krouse HR (2000) The influence of water–rock interaction on the chemistry of thermal springs in Western Canada. Appl Geochem 15(4):439–454. 10.1016/S0883-2927(99)00066-9 [Google Scholar]

- Grasby SE, Chen Z, Hamblin AP, Wozniak PRJ, Sweet AR (2008) Regional characterization of the Paskapoo Bedrock Aquifer System, Southern Alberta. Can J Earth Sci 45(12):1501–1516. 10.1139/E08-069/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/E08-069F21.JPEG [Google Scholar]

- Harris SJ, Cendón DI, Hankin SI, Peterson MA, Xiao S, Kelly BFJ (2022) Isotopic evidence for nitrate sources and controls on denitrification in groundwater beneath an irrigated agricultural district. Sci Total Environ 817(April):17. 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2021.152606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Van Der Kamp G, Rudolph DL (1998) Water and solute transfer between a prairie wetland and adjacent uplands, 1. Water balance. J Hydrol 207(1–2):42–55. 10.1016/S0022-1694(98)00098-5 [Google Scholar]