Abstract

Purpose

[18F]NaF PET has become an increasingly important tool in clinical practice toward understanding and evaluating diseases and conditions in which bone metabolism is disrupted. Full kinetic analysis using nonlinear regression (NLR) with a two-tissue compartment model to determine the net rate of influx (Ki) of [18F]NaF is considered the gold standard for quantification of [18F]NaF uptake. However, dynamic scanning often is impractical in a clinical setting, leading to the development of simplified semi-quantitative parameters. This systematic review investigated which uptake parameters have been used to evaluate bone disorders and how they have been validated to measure disease activity.

Methods

A literature search (in PubMed, Embase.com, and Clarivate Analytics/Web of Science Core Collection) was performed up to 28th November 2023, in collaboration with an information specialist. Each database was searched for relevant literature regarding the use of [18F]NAF PET/CT to measure disease activity in bone-related disorders. The main aim was to explore whether the reported semi-quantitative uptake values were validated against full kinetic analysis. A second aim was to investigate whether the chosen uptake parameter correlated with a disease-specific outcome or marker, validating its use as a clinical outcome or disease marker.

Results

The initial search included 1636 articles leading to 92 studies spanning 29 different bone-related conditions in which [18F]NaF PET was used to quantify [18F]NaF uptake. In 12 bone-related disorders, kinetic analysis was performed and compared with simplified uptake parameters. SUVmean (standardized uptake value) and SUVmax were used most frequently, though normalization of these values varied greatly between studies. In some disorders, various studies were performed evaluating [18F]NaF uptake as a marker of bone metabolism, but unfortunately, not all studies used this same approach, making it difficult to compare results between those studies.

Conclusion

When using [18F]NaF PET to evaluate disease activity or treatment response in various bone-related disorders, it is essential to detail scanning protocols and analytical procedures. The most accurate outcome parameter can only be obtained through kinetic analysis and is better suited for research. Simplified uptake parameters are better suited for routine clinical practice and repeated measurements.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12149-024-01991-9.

Keywords: 18-Fluoride, PET, Bone diseases, [18F] NaF, Quantification, Sodiumfluoride

Introduction

[18F]NaF PET scanning has become an increasingly important tool in understanding and evaluating diseases and conditions in which bone metabolism is disrupted. In 1962, Blau et al. first demonstrated that there was increased uptake of 18F in areas of new bone formation, as compared with normal bone [1]. Since this first report, [18F]NaF PET has been established as an imaging modality for understanding and measuring treatment response in various metabolic bone disorders [2].

Bone formation typically occurs in two separate manners, i.e., as endochondral or as intramembranous ossification. In endochondral ossification, mesenchymal stem cells are stimulated to differentiate into chondrocytes, thereby creating a cartilage scaffold. After the cartilage scaffold has been established, mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into osteoblasts and start to produce an extracellular bone matrix, which slowly but steadily replaces the cartilage scaffold [3]. The second is through intramembranous ossification, in which mesenchymal stem cells differentiate directly into osteoblasts, which similarly create an extracellular bone matrix, but without first creating a cartilage scaffold. In the extracellular bone matrix, hydroxyapatite crystals are formed. After injection, [18F]NaF is distributed throughout the body and eventually binds to the crystallized surface, replacing the hydroxyl ions in hydroxyapatite to form fluorapatite [4, 5]. The tracer eventually accumulates in all sites of accessible bone, including sites of bone formation and bone degradation. The rate of accumulation depends on tracer availability, regional blood flow, and bone turnover [6].

[18F]NaF PET cannot only visualize, but also quantify areas of increased bone turnover. The pharmacokinetics of 18F-fluoride can best be described by a two-tissue compartment model for irreversible binding. This model was first described by Hawkins et al. in 1992 and since then it has been recognized as the gold standard for quantifying [18F]NaF uptake [6, 7]. This model considers plasma delivery of 18F-fluoride, its extraction fraction and, finally, its binding to bone matrix. Upon defining an area of interest, the net rate of transfer from plasma to bone binding (Ki) can be estimated with a 60-min full dynamic scanning protocol, including arterial sampling, through nonlinear regression analysis (NLR). Even though this is the most accurate method for quantifying skeletal 18F-fluoride uptake, the procedure is less feasible in clinical practice due to the limited axial field of view covered by a dynamic scan, the complexity of data acquisition, and the burden it places on patients.

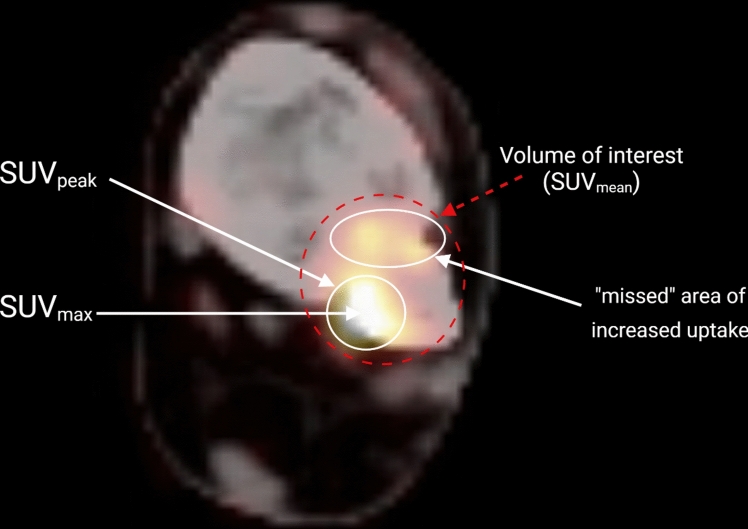

This has led to the use of simplified methods as alternatives to NLR, such as the Gjedde–Patlak analysis and standardized uptake value (SUV). These methods seem to correlate well with full kinetic analysis in normal bone and have become increasingly important in quantifying skeletal 18F-fluoride uptake. Gjedde–Patlak analysis is also based on the compartment model, but only requires a linear regression analysis once the radiopharmaceutical tracer uptake in the target tissue from the plasma occurs at a fixed rate [8, 9]. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to perform Gjedde–Patlak analysis on a regular basis as it still requires blood sampling and a (short) period of dynamic imaging. Therefore, SUV has become the most widely used parameter for quantification in daily clinical routine [10]. SUV is a semi-quantitative measure representing tissue activity in a volume of interest (VOI) corrected for injected activity and a body anthropometric measure such as weight, lean body mass or body surface area (Fig. 1). SUV can be calculated without any blood sampling and it can be used in association with a whole-body scan enabling the measurement of tracer distribution throughout the body [11]. Note that outcome from all mentioned approached depends on the region of interest definition, and SUV can be reported in a few ways. SUVmean is defined as the average SUV (and thus representing average [18F]NaF uptake) of all voxels within a VOI. SUVmax is the highest single-voxel value within a VOI, and SUVpeak is the average of a fixed size volume (often 1 cm3) centered around the hottest voxel within a VOI (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

[18F]NaF PET/CT image explaining the difference between volume of interest, SUVmax, SUVpeak and how an area of increased uptake can be “missed” when using SUVmax or SUVpeak

In recent years, many studies have used various uptake parameters to quantify [18F]NaF uptake in bone disorders. The purpose of this review was to provide an overview of the parameters that presently are used to measure [18F]NaF uptake in bone disorders, and to assess whether they are suitable for assessing disease activity.

Methods

A systematic search was performed in the databases: PubMed, Embase.com, and Clarivate Analytics/Web of Science Core Collection. The timeframe within the databases was from inception to 28th November 2023 and conducted by GLB and RR. The search included keywords and free text terms for (synonyms of) ‘Fluorine-18’ combined with (synonyms of) ‘positron emission’ combined with (synonyms of) ‘bone’. A full overview of the search terms per database can be found in the supplementary information (see Appendix 1). No limitations on date or language were applied in the search.

Study selection

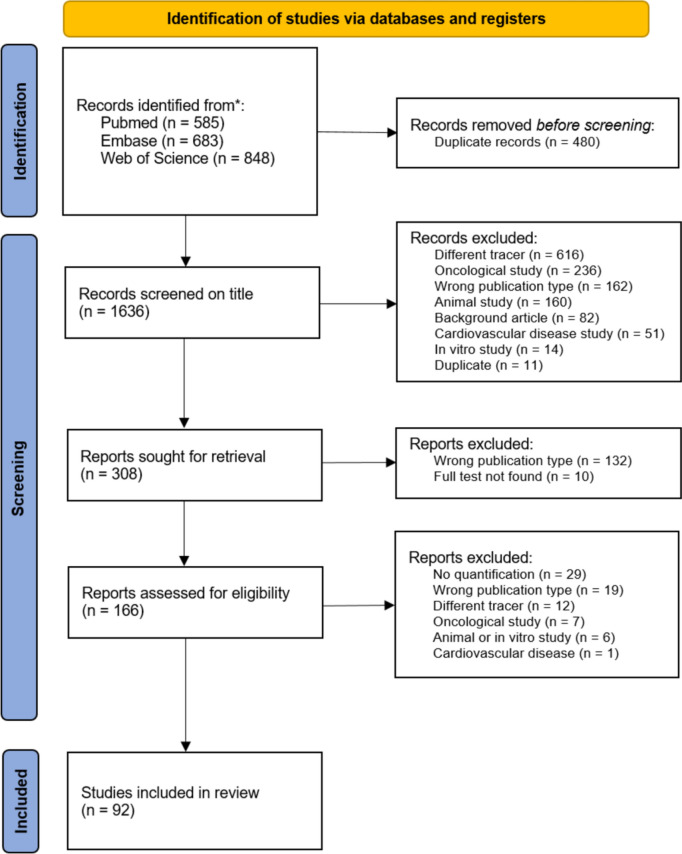

Two reviewers (RR and EE) independently screened all potentially relevant titles and abstracts for eligibility using Rayyan (web-tool to screen and select studies). Where necessary, the full text of an article was checked against the eligibility criteria. Differences in judgment were discussed and resolved by a consensus. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) studies using [18F]NaF PET; (ii) pathological condition primarily involving bone metabolism and/or healing; (iii) [18F]NaF PET-derived uptake parameter reported; (iv) studies published in English; and (v) full-text availability. Studies were excluded if they concerned: (i) oncological diseases; (ii) cardiovascular diseases; (iii) studies in otherwise healthy subjects; (iv) animal and in vitro studies; and (v) certain publication types such as editorials, letters, legal cases, interviews, conference abstracts, and reviews. The PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection

Quality assessment

The full text of the selected articles was obtained for further review. Two reviewers (RDdR and EMWE) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the full-text papers using the Study Quality Assessment Tool created by NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute). The results of this quality assessment can be found in Supplementary Material S2.

Results

Search and selection of results

The literature search generated a total of 2116 references: 584 in PubMed, 678 in Embase.com, and 623 in Clarivate Analytics/Web of Science Core Collection. After removing duplicates of references that were selected from more than one database, 1636 remained. The flow chart of the search and selection process is presented in Fig. 2.

After screening titles and abstracts, based on the selection criteria described above, 166 remained for full-text analysis. This analysis excluded a further 74 articles (Fig. 2). From the remaining 92 articles, the following data were extracted: study type, number of participants, age of participants (mean and standard deviation (SD)), quantitative parameters examined, chosen method of validation of the uptake parameters, and purpose of parameter quantification, which can be found in Table 1. In addition, details of PET methodology were extracted: PET scanner type, injected dose and scan time, reconstruction algorithm, and volume of interest (VOI) definition, which can be found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Articles included in the review. Listed is the study type, number of participants, age of participants (mean and standard deviation (SD)), quantitative parameters examined, chosen method of validation of the uptake parameters, and purpose of parameter quantification

| Author | Disease | Study type | Participants | Age (mean—SD) | Parameter | Purpose and result of [18F]NaF PET parameter quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kogan (2018) [83] |

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury | Cross-sectional | 15 | 32.7 (10.5) | SUVmax | Significantly increased subchondral bone SUVmax and cartilage T2 times were observed in the ACL-reconstructed knees compared to the contralateral knees. Using the contralateral knee as a control, a significant correlation between the difference in subchondral bone SUVmax (between injured and contralateral knees) and the adjacent cartilage T2 times was observed |

|

Jeon (2018) [37] |

Ankle trauma | Cross-sectional | 121 | 45.9 (16.7) |

SUVmax SUVmean TLF |

The fracture group had higher SUVmax, SUVmean, and TLF (total lesion fluorination) values than the non-fracture group. A higher SUVmax, SUVmean and TLF correlated with more limited range of motion scores in the fracture group but not in the non-fracture group |

|

Dyke (2019) [84] |

Ankle arthroplasty (total) | Prospective cohort | 9 | 68.9 (8.2) |

K1 NLR-derived Ki SUVmean |

Full kinetic analysis was performed, and Ki was analyzed over time. Ki appeared to mirror the measured SUVmean normalized for lean body mass, but correlation analysis was not performed. SUVmean values were analyzed pre- and post-operatively in the talus, with a higher SUVmean post-operatively |

|

Bruijnen (2018) [54] |

Ankylosing spondylitis | Prospective cohort | 12 | 36.7 (10.6) |

NLR-derived Ki SUVAUC # PET positive lesions |

SUVAUC was the most representative semi-quantitative outcome measure for monitoring the focal tracer uptake during intervention with anti-TNF therapy, with the highest correlation with NLR-derived Ki. Histological analysis of PET positive lesions confirmed local osteoid formation. Lesions were also followed-up on over time. After 12 weeks of anti-TNF treatment, [18F]NaF uptake in clinical responders (> 20% improvement in disease activity score (ASAS20)) decreased significantly in the costovertebral and SI joints in contrast to non-responders |

|

Kim (2020) [32] |

Ankylosing spondylitis | Prospective cohort | 27 | 37.9 (6.2) |

K1, k2, k3, k4 NLR-derived Ki SUVmean SUVmax |

Dynamic and static parameters were independently associated with disease scores, but correlation between scores was not investigated. Response to therapy was evaluated with a disease activity score (BASDAI). NLR-derived Ki and SUVmean were significantly different between the responders and non-responders. SUVmax of the spine had a significant positive correlation with BASDAI score |

|

Lee (2020) [85] |

Ankylosing spondylitis | Prospective cohort | 28 | 35.5 (11.3) |

Lesion-to-background SUVmax SUVmean |

Lesion-to-background (LBR) was compared to BASDAI score and follow-up BASDAI score. The LBR of the posterior joint correlated with BASDAI score. There was no significant correlation between the other analyzed areas and follow-up BASDAI score |

|

Bruckmann (2022) [86] |

Ankylosing spondylitis | Prospective cohort | 16 | 38.6 (12.0) | SUVmax | Quantification of tracer uptake showed that the mean SUVmax for all joints in the vertebra decreased significantly upon treatment. Anti-TNF antibody treatment led to a significant decrease in uptake within 3–6 months, especially, but not solely, at sites of inflammation |

|

Strobel (2010) [87] |

Axial spondyloarthritis | Prospective cohort | 28 | 47.0 (9.5) | SUVratio | Uptake was compared to radiographic grading of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ). Taking an SIJ/S ratio (SUVmean SIJ/SUVmean sacrum) of > 1.3 as the threshold, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy on a per patient basis were 80%, 77%, and 79%, respectively, for predicting SIJ arthritis |

|

Brenner (2004) [38] |

Bone graft healing | Prospective cohort | 34 | NS |

NLR-derived Ki Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean |

[18F]NaF uptake in cancellous grafts decreased by 25% from 6 to 12 months post-surgery and revealed a total decrease of 60–65% after 2 years as measured by SUVmean, Patlak-derived Ki, and NLR-derived Ki. Highly significant correlations were found between SUVmean, Patlak-derived Ki, and NLR-derived Ki for both grafts and normal limb bones. In patients imaged repeatedly, the percentage changes in [18F]NaF also correlated significantly between SUVmean, Patlak-derived Ki, and NLR-derived Ki |

|

Pumberger (2016) [88] |

Bone graft healing (spondylectomy) | Prospective cohort | 8 | 55.7 (9.2) | SUVmax | The SUVmax was 1.46 in the cage center, 8.14 in the reference vertebra, and 11.19 in adjacent endplates. Therefore, the viability of the bone within the cage was dramatically decreased compared to the reference (four-fold decreased). In contrast, the endplates showed a higher bone metabolism than the reference vertebra (1.6-fold increased) |

|

Kobayashi (2016) [89] |

Femoroacetabular impingement | Cross-sectional | 27 | 50.0 (15.6) | SUVmax | The SUVmax of in areas of impingement was significantly higher than the SUVmax of the contralateral regions. The SUVmax ratio between the affected and unaffected side correlated positively with the angle of impingement |

|

Oishi (2019) [90] |

Femoroacetabular impingement | Retrospective cohort | 41 | 43.0 (14.4) | SUVmax | An increased SUVmax corresponded with a specific femoroacetabular impingement subtype, making it possible to distinguish various morphologies of femoroacetabular impingement by measuring uptake |

|

Botman (2019) [53] |

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva | Prospective cohort | 5 | 26.9 (6.9) | SUVpeak | SUVpeak over time was compared to heterotopic bone volume. A SUVpeak > 8.4 corresponded with an increase of heterotopic bone volume |

|

Papadakis (2019) [20] |

Fibrous dysplasia | Retrospective cohort | 15 | 27.0 (6.9) |

MAV SUVmax SUVmean TLF |

Metabolic active volume (MAV) and total lesion fluorination (TLF) significantly correlated with lifetime fractures/orthopedic/craniofacial surgeries, mean fractures/orthopedic/craniofacial surgeries per year, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin and n-telopeptides |

|

van der Bruggen (2020) [18] |

Fibrous dysplasia | Retrospective cohort | 20 | 46.0 (14.1) |

SUVmean SUVpeak TLF |

TLF correlated with the skeleton burden score (region-based scoring system estimating uptake per area to generate an overall disease score, SBS). TLF correlated with ALP, procollagen peptide type 1 N-terminal (P1NP), and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23). The SBS did not correlate with ALP or P1NP, but was correlated to FGF-23. SUVpeak did not appear to have to have any correlation of the serum biomarkers of bone metabolism |

|

Choe (2011) [46] |

Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 41 | 72.8 (9.5) | SUVmax | A SUVmax > 5.0 was indicative of sceptic loosening of the prothesis |

| Forrest (2006) [42] | Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 15 | 45.0 (6.4) | SUVmean | The SUVmean in the operated hips was significantly higher than the non-operated hips, indicating increased burn turnover. This did not differ per hip region |

|

Kumar (2016) [45] |

Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 45 | 51.8 (15.3) | SUVmax | A SUVmax > 4.4 in the early imaging phase, and SUVmax > 8.1 in the delayed imaging phase correlated with sceptic loosening of the implant as confirmed by surgery and histopathology |

|

Piert (1999) [39] |

Hip arthroplasty | Cross-sectional | 16 | 71.6 (7.7) |

NLR-derived Ki Patlak-derived Ki |

Allogenic bone grafts were characterized by a significantly increased NLR-derived Ki after 3–6 weeks (+ 190.9%) compared with contralateral hips but decreased almost to the baseline levels of contralateral hips (+ 45.5%) after 5 months to 9 years |

|

Raijmakers (2014) [91] |

Hip arthroplasty | Cross-sectional | 22 | 44.8 (25.2) |

NLR-derived Ki Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean |

The Patlak-derived Ki, for 10–60 min after injection, showed a high correlation with the NLR-derived Ki. The highest correlation between Ki and lean body mass–normalized SUV was found for the interval 50–60 min. Finally, changes in SUV correlated significantly with those in NLR-derived Ki. The present data support the use of both Patlak and SUV for assessing fluoride kinetics in humans. However, [18F]NaF PET has only limited accuracy in monitoring bone blood flow |

|

Temmerman (2008) [41] |

Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 6 | 76.0 (5.0) | NLR-derived Ki | There was a significant increase in periprosthetic bone metabolism as measured by NLR-derived Ki in patients in whom allogeneic bone grafts were used compared to patients where no bone grafts were used |

|

Tezuka (2020) [92] |

Hip arthroplasty | Randomized control trial | 52 | 65.0 (12.0) | SUVmax | The influence of a coating in hip arthroplasty in terms of bone mineral density (BMD) preservation is limited. No significant correlation was found between BMD and SUVmax measured by PET, either with or without the use of a hip arthroplasty in coating |

|

Ullmark (2009) [40] |

Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 7 | 66.0 (6.4) | SUVmean | Uptake was 64% higher on the affected side compared to reference bone. 1 week after surgery, it was increased by 77% in segmental regions, while the uptake of the cavitary regions was at the reference level. After 4 months, the uptake was increased by 91% in cavitary regions and by 117% in segmental regions |

|

Ullmark (2013) [43] |

Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 8 | 57.5 (7.5) | SUVmean | The SUVmean was statistically significantly higher in both types of implants compared to the contralateral hip at 4 months and was most pronounced in the upper femur |

|

Ullmark (2020) [44] |

Hip arthroplasty | Prospective cohort | 26 | NS | SUVmean | The SUVmean was 4.6 (at 6 weeks) and 3.5 (at 6 months) around the uncemented cups, and 4.8 and 4.0, respectively, for the cemented cups. Normal healthy bone metabolism in the reference bone was 2.8 and 2.7 SUV at 6 weeks and 6 months, respectively |

|

Mechlenburg (2013) [93] |

Hip dysplasia (periacetabular osteotomy) | Prospective cohort | 12 | 36.0 (9.3) | NLR-derived Ki | Non-linear regression fitting was not stable for the first 45 min, fitting required a scanning time of 90 min which was not obtained for most of the participants and therefore not reported |

|

Waterval (2011) [94] |

Hyperostosis cranialis interna | Prospective cohort | 9 | NS |

SUVmax SUVmean |

Uptake of patients was compared to family members acting as control patients. SUVmean was significantly higher in the sphenoid bone and clivus regions of patients with hyperostosis cranialis interna |

|

Jenkins (2017) [95] |

Lower back pain | Cross-sectional | 6 | 65.3 (10.1) |

Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean SUVmax |

Patlak-derived Ki correlated with disability score (and weakly with MRI facet athropathy grade). SUVmax and SUVmean were also compared but did correlate significantly |

| Kobayashi (2013) [23] | Osteoarthritis (hip) | Cross-sectional | 48 | 42.3 (15.3) | SUVmax | Differences in the average SUVmax were found for each Kellgren–Lawrence (K/L) grade group. The average SUVmax values were increasingly higher according to K/L grade group and pain severity group |

|

Kobayashi (2015) [30] |

Osteoarthritis (hip) | Cross-sectional | 43 | 49.8 (14.7) | SUVmax | Joints were considered positive for PET uptake when a SUVmax > 6.5 was found. Most (96%) of the joints affected by osteoarthritis on the MRI were also PET positive |

|

Kobayashi (2015) [25] |

Osteoarthritis (hip) | Cross-sectional | 57 | 50.8 (11.3) | SUVmax | A SUVmax cut-off value of 7.2 (sensitivity: 1.00, specificity: 0.84) in the joint was predictive for pain worsening and 6.4 (sensitivity: 0.92, specificity: 0.83) for minimal joint space narrowing |

|

Tibrewala (2019) [96] |

Osteoarthritis (hip) | Cross-sectional | 10 | 59.9 (12.5) |

Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean SUVmax |

Shaft thickness correlated with SUVmean and SUVmax in the femur and Patlak-derived Ki in the acetabulum. Pain had increased correlations with SUVmean and SUVmax in the acetabulum and femur when shaft thickness was considered |

|

Yellanki (2018) |

Osteoarthritis (hip) | Retrospective cohort | 116 | 48.6 (10.7) | SUVmean | SUVmean for the hip positively correlated with BMI as a risk factor for developing osteoarthritis, but not to age |

| Jena (2022) [24] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | Cross-sectional | 16 | 42.7 (11.8) | SUVmax | Globally the mean SUVmax was found to increase according to K/L score. There is a proportional increase in SUVmax with the size of osteophytes |

| Jena (2023) [29] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | Cross-sectional | 16 | 41.0 (11.8) | SUVmax | Bone marrow lesions and osteophytes with a higher MRI osteoarthritis knee score (MOAKS) score showed higher SUVmax |

|

Mackay (2021) [97] |

Osteoarthritis (knee) | Cross-sectional | 11 | 54.0 (12.0) |

SUVmax Ktrans |

SUVmax was positively associated with adjacent Ktrans (the volume transfer coefficient between the blood plasma and the extracellular extravascular space). Synovitis is more intense adjacent to peripheral bone regions with increased metabolic activity than those without, although there is some overlap. Subregional bone metabolic activity is positively associated with intensity of adjacent synovitis |

|

Savic (2016) [28] |

Osteoarthritis (knee) | Prospective cohort | 16 | NS |

Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean SUVmax |

SUVmean correlated highly with Patlak-derived Ki. Degenerative changes on the MRI were associated with increased bone turnover on the PET. Associations between pain and increased bone uptake were seen in the absence of morphological lesions in cartilage, but the relationship was reversed in the presence of incident cartilage lesions |

|

Tibrewala (2020) [27] |

Osteoarthritis (knee) | Prospective cohort | 29 | 55.9 (8.6) | SUVmean | Using the mean values of the MRI intensity and SUV of all the patients in the various VOIs in a regression model were able to predict the bone and cartilage lesion scores as measured by K/L and WORMS scores |

|

Watkins (2021) [98] |

Osteoarthritis (knee) | Prospective cohort | 31 | 65.6 (10.4) |

K1 NLR-derived Ki SUVmax |

Mean and maximum SUV and kinetic parameters Ki, K1, and extraction fraction were significantly different in the knee joint between healthy subjects and subjects with osteoarthritis. Between-group differences in metabolic parameters were observed both in regions where the osteoarthritis group had degenerative changes as well as in regions that appeared structurally normal. Uptake parameters were not correlated to each other |

|

Watkins (2022) [99] |

Osteoarthritis (knee) | Prospective cohort | 10 | 59.0 (8.0) |

K1 NLR-derived Ki SUVmean, SUVmax |

There was a significant increase in [18F]NaF uptake as measured in NLR-derived Ki, K1, SUVmean and SUVmax in osteoarthritis exercised knees, differing per bone region |

|

Christersson (2018) [58] |

Osteomyelitis | Prospective cohort | 8 | 52.0 (11.0) |

SUVmax SUVmax ratio |

[18F]NaF uptake and [18F]FDG uptake were evaluated in areas suspicious for osteomyelitis. [18F]NaF SUVmax compared to contralateral regions and was found to be elevated in infected areas as confirmed with tissue histology. SUVmax between [18F]NaF and [18F]FDG correlated highly. Combination of tracers leadS to better identification of area requiring resection during surgery |

|

Freesmeyer (2014) [56] |

Osteomyelitis | Cross-sectional | 11 | 53.0 (6.9) |

SUVmax SUVmean |

The early dynamic sequence SUV values correlated with SUV values obtained from the later static sweep. Uptake was compared to diagnosis already made on other radiographical images. The affected bone area showed significantly higher SUVmax and SUVmean compared to the healthy contralateral region. The affected bone areas also significantly differed from non-affected contralateral regions in conventional late [18F]NaF PET/CT |

|

Reinert (2022) [57] |

Osteomyelitis (jaw) | Prospective cohort | 6 | 55.3 (10.0) | SUVmean | SUVmean in affected jawbone was significantly increased in all patients compared to healthy jawbone |

|

Kubota (2015) [64] |

Osteonecrosis (femoral head) | Cross-sectional | 42 | 39.5 (11.0) | SUVmax | SUVmax increased according to the progression of the Ficat classification stage. The mean SUVmax was significantly higher in the collapse group than the non-collapse group (P < 0.01). The cut-off SUVmax of 6.45 (sensitivity: 0.80, specificity: 0.92) was used for the prediction of femoral head collapse |

|

Aratake (2009) [65] |

Osteonecrosis (knee) | Prospective cohort | 13 | 70.0 (5.0) | SUVmax | The SUVmax was measured at different disease stages (SONK). There were no significant differences in these measurements between the SONK stages. However, a significant positive correlation between the SUVmax and lesion size, including the surface area of the lesion and the condyle width ratio, was found. The approximate volumes of the lesions also showed a significant correlation with the SUVmax |

|

Schiepers (1998) [66] |

Osteonecrosis (femoral head) | Cross-sectional | 5 | 33.0 (9.2) | NLR-derived Ki | The femoral head affected by osteonecrosis exhibited lower uptake as measured by NLR-derived Ki than femoral heads unaffected |

|

Frost (2008) [71] |

Osteoporosis | Cross-sectional | 16 | 64.3 (6.6) |

NLR-derived Ki Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean |

The precision of the PET parameters ranged from 12.2% for Ki−3 k to 26.6% for Ki−4 k. The individual precision errors in Ki for each subject were significantly greater using the 2t4k model than the 2t3k model or Patlak model. No significant difference in precision was found among Ki−2t3k, Ki-Patlak, and SUVmean. The precision values of the 3 biochemical markers were similar to the value observed for Ki using the 2t3k model and Patlak and SUVmean but were less than that observed using the 2t4k model. Direct comparison of individual [18F]NaF uptake and biochemical markers was not performed |

|

Jassel (2019) [67] |

Osteoporosis | Retrospective cohort | 63 | NS |

NLR-derived Ki SUVmean |

Correlation between SUV, hounsfield units (HU), bone mineral apparent density (BMAD), bone mineral density (BMD) was analyzed. Uptake as measured by NLR-derived Ki correlated positively with HU, BMAD, and BMD. Correlations were highest between NLR-derived Ki and HU and lowest between NLR-derived Ki and areal BMD. Performance of SUVmean was comparable to NLR-derived Ki |

|

Park (2023) [100] |

Osteoporosis | Retrospective cross-sectional | 88 | 48.0 (15.6) | SUVmean | There was a significant negative correlation between SUVmean and age in females and a weaker, but also significant correlation in males |

|

Puri (2021) [101] |

Osteoporosis | Cross-sectional | 30 | 61.0 (5.8) | NLR-derived Ki at different time intervals | A comparison was performed for 2t3k-ki performance at different time points to investigate whether similar Ki measurements could be found using a shorter time interval. Ki measurements with statistical power equivalent or superior to conventionally analyzed 60-min dynamic scans were obtained with scan times as short as 12 min |

|

Rhodes (2020) [102] |

Osteoporosis | Retrospective cohort | 139 | 52.0 (15.6) |

Bone metabolism score (BMS) SUVmean |

Age was negatively correlated with left and right femoral head BMS (SUV of bone exceeding 100 HU/SUV of total region * 100), predominately in the cortical bone. BMD was positively correlated with whole and cortical BMS |

|

Uchida (2009) [103] |

Osteoporosis (Alendronate treatment) |

Cross-sectional | 24 | 59.6 (5.4) | SUVmean | Lumbar spine SUVmean measurements were significantly lower in the osteoporotic group (T-score ≤ − 2.5) than in the group that was healthy or osteopenic (T-score > − 2.5). Although there was a significant correlation between BMD and SUV in the lumbar spine at baseline, there was no correlation between the 2 variables at 12 months of treatment with alendronate |

|

Frost (2003) [104] |

Osteoporosis (Risendronate treatment) | Prospective cohort | 18 | 67.0 (4.6) |

K1, k2, k3, k4, k3/[k2 + k3] NLR-derived Ki, |

Mean vertebral Ki decreased significantly by 18.4% from baseline to 6 months post-treatment. This decrease was similar in magnitude to the decrease observed for ALP |

|

Frost (2011) [68] |

Osteoporosis (Teriparatide treatment) | Cross-sectional | 20 | 65.3 (8.2) |

NLR-derived Ki, K1, k2, k3, k4 SUVmean |

Change in NLR-derived Ki in the spine was compared to changes in BTMs after 6 months of teriparatide therapy. None of the four correlations were statistically significant. Change in NLR-derived Ki in the lumbar vertebral bodies showed a highly significant change from baseline with a mean percentage increase of 23.8%. This correlated poorly with SUV measurement in the spine |

|

Siddique (2011) [105] |

Osteoporosis (Teriparatide treatment) | Cross-sectional | 40 | 65.3 (8.2) | NLR-derived Ki (2t3k and 2t4k model) Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean | Methods that calculated Ki assuming K4 = 0 required fewer subjects to demonstrate a statistically significant response to treatment than methods that fitted K4 as a free variable. Although SUV gave the smallest precision error, the absence of any significant changes makes it unsuitable for examining response to treatment in this study |

|

Fushimi (2022) [106] |

Osteoporosis (Zolendronic acid and denosumab treatment) | Matched, case–control | 23 | 70.2 (10.8) | SUVmean | The mean SUVs of the thoracic vertebrae in the denosumab and control group were not significantly different. The mean SUV of the cervical vertebrae in the zolendronic acid group were significantly lower than that in the control group |

|

Puri (2012) [69] |

Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | Retrospective cross-sectional | 12 | 61.5 (5.5) |

NLR-derived Ki (2t3k and 2t4k model) Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean |

Correlations between 2t4k-Ki and 2t3k-Ki, Patlak-derived Ki and SUV measured in the hip and lumbar spine combined were high with correlations of 0.91, 0.97, and 0.93, respectively |

|

Cook (2000) [21] |

Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | Cross-sectional | 26 | 62.0 (8.8) |

K1, k2, k3, k4 NLR-derived Ki |

Mean vertebral Ki and k1 in the lumbar vertebrae were found to be significantly greater than Ki and k1 in the humerus but no significant differences were found in K2, K3, and K4 |

| Frost (2004) [107] | Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | Cross-sectional | 72 | 61.0 (7.9) |

k3/(k2 + k3) NLR-derived Ki |

Vertebral estimates of NLR-derived Ki were significantly lower in the osteoporotic group compared with both the osteopenic and normal groups. A significant positive correlation was observed between BMD and Ki and the fraction of the tracer that bound to the bone mineral [k3/(k2 + k3). A significant negative correlation was observed between levels of ALP and the fraction of tracer that bound to bone mineral |

|

Frost (2009) [108] |

Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | Cross-sectional | 23 | 64.3 (4.4) |

K1, k2, k3, k4, Ki/k1 NLR-derived Ki |

Mean bone perfusion K1 and bone turnover Ki were significantly higher at the lumbar spine compared to the humerus for both treatment-naïve and antiresorptive groups |

|

Puri (2013) [70] |

Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | Cross-sectional | 12 | 62.6 (5.3) |

K1 NLR-derived Ki SUVmean |

Values of K1, NLR-derived Ki and SUV at the femoral neck and femoral shaft were three times lower than at the lumbar spine. Among the proximal femur sites, NLR-derived Ki and SUV were lower at the femoral shift compared with the femoral neck. Spearman correlation coefficient between K1, NLR-derived Ki and SUVmean was highly statistically significant |

|

Cook (2002) [109] |

Paget’s disease | Prospective cohort | 7 | 70.7 (ns) |

K1, k2, k3, k4 K1/k2, Ki/K1 NLR-derived Ki |

Compared with normal bone, pagetic bone demonstrated higher values of NLR-derived Ki and k1, reflecting increased mineralization and blood flow, respectively. A high correlation was found between ALP levels and Ki in pagetic bone |

|

Installe (2015) [22] |

Paget’s diseases | Cross-sectional | 14 | 64.8 (12.7) |

K1, Ki/K1 NLR-derived Ki Patlak-derived Ki SUVmax |

Baseline uptake of [18F]NaF by pagetic bones was significantly higher than in normal bones. SUVmax correlated with both Patlak-derived Ki and NLR-derived Ki at baseline, 1 month, and 6 months. Moreover, the change of SUVmax between baseline and 1 month, as well as between baseline and 6 months, also correlated with the change of Patlak-derived Ki and NLR-derived Ki |

|

Waterval (2013) [35] |

Otosclerosis | Prospective cohort | 21 | 59.5 (12.7) |

SUVmax SUVmean |

Against grading on CT and hear loss, the relation between CT otosclerosis classification and SUVmean values at different anatomical subsites was investigated; a significant correlation was found at the saccule between these two. Significant correlations between audiogram classification and SUVmean values were present for the fenestral and saccule areas and the posterior part of the internal auditory canal |

|

Draper (2012) [36] |

Patellofemoral pain | Cross-sectional | 20 | 31.0 (5.2) |

SUVmean SUVpeak |

SUV was compared against experienced pain as evaluated by standardized pain questionnaires. Patients with painful knees exhibited increased tracer uptake compared to the pain-free knees of four subjects with unilateral pain and there was a correlation between increasing SUVpeak and pain intensity |

|

Graf (2020) [74] |

Primary hyperparathyroidism and brown tumors | Retrospective cohort | 8 | 49.3 (13.6) | MAV | MAV was correlated with PTH and ALP, and the requirement for intense post-operative calcium substitution, which determines the duration of hospitalization. The total MAV of the brown tumor per patient correlated positively with serum calcium. MAV correlated significantly with serum PTH, ALP and duration of post-operative hospitalization |

|

Hochreiter (2019) [110] |

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 84.5 (3.8) | SUVmax | The mean value of SUVmax of the allografts was compared to the reference vertebrae but was not statistically different, implying viability and fusion in all allografts |

|

Jonnakuti (2018) [111] |

Rheumatoid arthritis (knee arthrosis) | Cross-sectional | 18 | 56.7 (12.4) |

SUVmean TBR |

SUV correlated with K/L score. Unadjusted global SUVmean of the knee or femoral neck scores did not significantly correlate with average K/L grading. Higher TBR scores of the knee were observed among individuals with higher average K/L grading scores |

|

Park (2021) [33] |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Cross-sectional | 17 | 53.8 (9.5) |

SUVmax TBR |

Tender and swollen joints had a significantly higher SUVmax and joint-to-bone uptake ratio than joints without synovitis. On correlation analysis, summed joint SUVmax and summed joint-to-bone uptake ratio of 28 joints showed strong positive correlation with a rheumatoid arthritis disease score (DAS28-ESR). The summation of both PET/CT parameters of 28 joints showed a diagnostic accuracy of 100.0% for predicting high disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis |

|

Reddy (2023) [112] |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Cross-sectional | 18 | 57.3 (11.9) | SUVmean | In the knees, SUVmean significantly correlated with body weight, BMI, leptin, and sclerostin levels. No significant correlation was observed between either PET parameter and age, height, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and interleukins 1 and 6 |

|

Watanabe (2016) [34] |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Prospective cohort | 12 | 60.0 (11.8) | SUVmax | SUVmax was compared against radiographic erosion on X-ray and estimated yearly progression of total radiographic scores. Progression significantly correlated with the SUVmax. DAS28 and physical function assessments were also performed but not compared to [18F]NaF uptake |

|

Aaltonen (2020) [14] |

Renal osteodystrophy | Cross-sectional | 26 | 63.0 (13.3) |

Fractional uptake rate Patlak-derived Ki |

Fractional uptake rate (FUR) was calculated with Patlak-derived Ki by dividing Patlak-derived Ki in the area of interest by the AUC blood activity. There was a statistically significant correlation between mean Patlak-derived Ki and FUR levels and a majority of the histomorphometric parameters, such as bone formation rate, activation frequency, mineralized surface per bone surface and osteoblast- and osteoclast surfaces. There was also a statistically significant correlation between osteoid thickness and fluoride activity at the anterior iliac crest measured with FURmean. However, there was no correlation between mean Ki and FURmean and osteoid volume of bone volume or mineralization lag time. There was a statistically significant correlation between PTH and Ki mean and FURmean levels. There was no statistical correlation between Ki mean and FURmean and ionized calcium and ALP. A weak correlation between phosphorus and Ki and FURmean was also observed |

|

Aaltonen (2021) [13] |

Renal osteodystrophy | Cross-sectional | 26 | 63.0 (13.3) |

Fractional uptake rate Patlak-derived Ki |

Ki and FUR were compared to histologic classification of renal osteodystrophy (ROD) (high/mild/low). In ROC analysis for discriminating high turnover/hyperparathyroid bone disease from other types of ROD, using unified TMV-based classification, Ki cut-off > 0.055 Ml/min/Ml in the PET scan had an AUC of 0.86, the sensitivity was 82% and specificity 100%, the negative predictive value 88% and positive predictive value 100%. In ROC analysis for discriminating low turnover/adynamic bone disease from other types of ROD, using unified TMV-based classification, fluoride activity cut-off < 0.038 Ml/min/Ml in the PET scan had an AUC of 0.87 with 100% sensitivity and 70% specificity, the negative predictive value was 100% and positive predictive value |

|

Frost (2013) [17] |

Renal osteodystrophy | Cross-sectional | 19 | 64.0 (15.4) |

NLR-derived Ki NLR-derived Ki/BMAD |

Significant differences in NLR-derived Ki between different skeletal sites were observed for both the CKD stage 5 and osteoporosis groups. NLR-derived Ki was also compared to bone mineral density as measured on the DXA scan. Significant correlation between Ki/BMAD and mineral acquisition apposition rate in histological analysis was observed but not between Ki/BMAD and other histological mineral density parameters |

|

Fuglo (2023) [113] |

Renal osteodystrophy | Cross-sectional | 10 | 67.0 (5.8) |

Patlak-derived Ki NLR-derived Ki |

Various input functions toward calculating NLR-derived Ki and Patlak-derived Ki were compared. The NLR-derived Ki from the femoral bone VOI’s correlated positively to PTH and showed significant differences between patients and controls |

|

Vrist (2021) [15] |

Renal osteodystrophy | Prospective cohort | 17 | 62.5 (10.1) |

Patlak-derived Ki NLR-derived Ki |

Ki from Patlak analyses correlated well with non-linear regression analysis. NLR-derived Ki correlated with bone turnover parameters obtained through bone biopsy, being able to detect a low bone turnover with a high sensitivity (83%) and specificity (100%) |

|

Vrist (2022) [16] |

Renal osteodystrophy | Prospective cohort | 17 | 62.5 (10.1) | Estimation of Patlak-derived Ki from static images | The pelvic Ki from [18F]NaF PET/CT correlated with bone turnover parameters obtained by bone biopsy. CT-derived radiodensity correlated with bone volume. Of the biomarkers, only osteocalcin showed a correlation with turnover assessed by histomorphometry |

| Constantinescu (2020) [50] | Spinal interbody fusion (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) | Prospective cohort | 18 | 67.8 (5.2) | SUV | SUV was compared for fused and unfused patients, though these did not differ. The [18F]NaF uptake did not correlate with the chronological change in the clinical parameters |

|

Peters (2015) [52] |

Spinal interbody fusion (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) | Prospective cohort | 36 | NS | SUVmax | SUVmax in the vertebral endplates was significantly higher in patients in the lowest Oswestry Disability Index category (i.e., with the worst clinical performance) than in patients in higher categories. The visual analog scale and EuroQol results were similar although less pronounced, with only SUVmax between category 1 and 2 being significantly different |

|

Peters (2015) [51] |

Spinal interbody fusion (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) | Prospective cohort | 16 | NS |

NLR-derived Ki Patlak-derived Ki K1, k2, k3, Vb K1/k2 k3/(k2 + k3) SUVmax SUVmean |

Statistically significant differences between control and operated regions were observed for SUVmax, SUVmean, NLR-derived Ki, Patlak-derived Ki, K1/k2 and k3/(k2 + k3). Diagnostic CT showed pseudarthrosis in 6/16 patients, while in 10/16 patients, segments were fused. Of all parameters, only those regarding the incorporation of bone (NLR-derived Ki, Patlak-derived Ki, k3/(k2 + k3)) differed statistically significantly in the intervertebral disc space between the pseudarthrosis and fused patients group |

|

El Yaagoubi (2022) [49] |

Spinal Fusion (aseptic pseudoarthrosis) | Retrospective cohort | 18 | 58.5 (14.7) |

SUVmax SUVratio |

Statistically significant difference in SUVmax values (around cage/intervertebral disk space) and uptake ratios between the revision surgery and control groups. An increased SUVmax was also indicative of aseptic pseudoarthrosis |

|

Lee (2019) [55] |

Surgical site infection | Retrospective cohort | 23 | NS |

Lesion-to-blood ratio Lesion-to-bone ratio Lesion-to-muscle ratio SUVmax SUVmean |

Diagnosis was made against other markers (clinical, microbiological or radiographical). Lesion-to-blood pool uptake ratio on early phase scan showed the highest area under the receiver operating characteristic curve value with the cut-off value of 0.88 showing sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 85.7%, 88.9%, and 87.0%, respectively |

|

Lee (2013) [63] |

Temporomandibular joint disorder | Cross-sectional | 24 | 32.0 (14.0) |

SUVmean, TMJ-to-skull ratio, TMJ-to-spine ratio TMJ-to-muscle ratio |

Temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD) with osteoarthritis had a high temporomandibular joint (TMJ) uptake ratio on 18F-PET/CT. The TMJ-to-skull uptake ratio on PET/CT showed the highest sensitivity (89%) and accuracy (81%) of all the uptake ratios examined |

|

Suh (2018) [62] |

Temporomandibular joint disorder | Prospective cohort | 76 | 40.3 (17.1) | SUVmax | Uptake was compared against disease activity and symptoms. SUVmax was significantly greater in arthralgic TMJs than in non-arthralgic TMJs. SUVmax was also significantly greater in TMJ osteoarthritis than in non-TMJ osteoarthritis and asymptomatic TMJs |

|

Lundblad (2017) [47] |

Tibia bone healing (complex fractures, osteomyelitis, osteotomies) | Prospective cohort | 24 | 46.3 (17.6) |

SUVmax SUVmean SUVmean change per day |

Uptake was evaluated in the fracture healing process. SUVmean and SUVmax difference per day did not appear to have a consistent pattern throughout the bone-healing progress. Dynamic analysis was performed and compared to simplified parameters but not reported |

|

Lundblad (2015) [114] |

Tibia bone healing (with Taylor Spatial Frame) | Prospective cohort | 18 | 42.5 (14.4) |

Patlak-derived Ki SUVmean SUVmax |

Correlation analysis was performed of SUVmean against Patlak Ki (r = 0.92). Fracture healing region compared to reference bone and muscle. The site of the fracture showed increased uptake in the Patlak-derived Ki, compared to reference muscle and bone on a per patient basis, though no statistical analysis was performed |

|

Sanchez-Crespo (2017) [48] |

Tibia bone healing (with Taylor Spatial Frame) | Prospective cohort | 24 | 45.2 (17.0) | NLR-derived Ki, SUVmax | NLR-derived Ki and SUVmax correlated poorly to each other. NLR-derived Ki differed significantly between the separate orthopedic conditions (pseudoarthrosis, deformity, fracture) |

|

Rauscher (2015) [115] |

Unclear foot pain | Prospective cohort | 22 | 41.0 (13.3) |

SUVmean SUVmax |

Multiple pathologies (osteoarthritis and stress fractures) were analyzed and determined on MRI and CT images. Increased 18F-fluoride correlated with a concurrent radiological diagnosis for SUVmean and SUVmax |

|

Lima (2018) [61] |

Unilateral condylar hyperplasia (UCH) | Prospective cohort | 20 | 26.1 (8.1) |

SUVmax SUVratio |

SUVmax measured in the affected condyle was significantly higher than in the unaffected condyle |

|

Ahmed (2016) [60] |

Unilateral condylar hyperplasia | Prospective cohort | 16 | 19.5 (2.6) | SUVmax | The affected condyle was compared to the unaffected condyle. A statistically significant difference was present between the mean percentage difference of SUVmax of the affected and unaffected samples |

|

Saridin (2009) [59] |

Unilateral condylar hyperplasia | Prospective cohort | 13 | 28.0 (7.5) | NLR-derived Ki | No evidence of an abnormally high rate of bone growth in the affected condylar region in UCH patients. Instead, the rate of bone growth appeared to be reduced in the contralateral condylar region |

|

Schiepers (1997) [116] |

Various bone disorders | Cross-sectional | 9 | 64.0 (7.5) | NLR-derived Ki | Metabolically active zones have an increased influx rate and permits classification of bone disorders and can in potential monitor therapy response in metabolic bone disease |

Table 2.

PET methodology details

| Authors | Disease | PET scanner | PET/CT/MRI | Scan time and injected dose | Reconstruction algorithm details reported | VOI method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kogan (2018) [83] | Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury | PET–MR hybrid system (GE SIGNA, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 74–111 MBq Scan time: static sweep 45 min after injection |

Matrix: 256 × 128 MR-based attenuation correction |

Manual On MRI and PET images separately Based on anatomical boundaries on the MRI and hot spots on the PET images |

| Jeon (2019) | Ankle trauma | Biograph mCT (Siemens Healthcare, Munich, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 5.18 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

NS | NS |

| Dyke (2019) [84] | Ankle arthroplasty (total) |

Biograph 64-slice Siemens mCT (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 185 – 370 mBq Scan time: Dynamic sequence (4 × 15 s, 5 × 30 s, 2 × 60 s, 2 × 120 s, 4 × 240 s, and 3 × 300 s) totaling 45 min. Data were summed to create the static image set |

NS |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Bruijnen (2018) [54] | Ankylosing spondylitis |

Gemini TF or Ingenuity TF (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA, USA) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 111 MBq Scan time: 30 min dynamic sequence, 45 min post-injection the whole-body static sweep was performed |

NS |

Manual On PET images |

| Kim (2020) [32] | Ankylosing spondylitis | Gemini (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 322 – 396 MBq Scan time: 30 min dynamic sequence, immediately followed by a static sweep |

NS | Unclear, erroneous referencing in the article |

| Lee (2020) [85] | Ankylosing spondylitis | Biograph 6 (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: 60 min after injection |

Matrix: 168 × 168 Algorithm: a standard iterative algorithm |

Manual On PET images |

| Bruckmann (2022) [86] | Ankylosing spondylitis | Biograph mMR (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 161 ± 8 MBq Scan time: 40 min after injection |

Correction: attenuation, truncation |

Manual On MRI images |

| Strobel (2010) [87] | Axial spondyloarthritis |

Discovery STE or Discovery Rx (GE Health Systems, Milwaukee, WI) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 100 – 150 MBq Scan time: 30 – 45 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM |

Manual On CT images |

| Brenner (2004) [38] | Bone graft healing | Advance Tomograph (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) | PET |

Dose: 3.7 MBq/kg Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (4 × 20 s 4 × 40 s, 4 × 60 s, 4 × 180 s, 8 × 300 s) |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: filtered back-projection using a Hanning filter Correction: Random and scattered coincidences, attenuation and decay |

Manual with a range of fixed-sized VOIs On PET images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Pumberger (2016) [88] | Bone graft healing (spondylectomy) | Gemini TF 16 PET/CT system (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: 45 min after injection |

Correction: attenuation |

Manual On PET/CT (fused) images |

| Kobayashi (2016) [89] | Femoroacetabular impingement | SET-2400W instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM Correction: attenuation |

Manual On PET images Based on anatomical boundaries (overlaid on separate acquired CT and MRI images) |

| Oishi (2019) [90] | Femoroacetabular impingement |

Celesteion (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: 40 min after injection |

NS |

Manual On CT images |

| Botman (2019) [53] | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva |

Gemini TF-64 (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) |

PET/CT | NS | NS |

Manual On CT images Based on a threshold of 80 HU and anatomical boundaries |

| Papadakis (2019) (20) | Fibrous dysplasia | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| van der Bruggen (2019) [18] | Fibrous dysplasia |

Philips Gemini TF TOF 64 T (Philips Healthcare; Eindhoven, The Netherlands) GE Discovery MI (GE Healthcare; Chicago, Illinois) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 1.00 MBq/kg (0.93–1.06 MBq/kg) Scan time: static sweep 49 min (44–67 min) after injection |

NS |

Manual and semi-automatic On CT and PET images Based on a SUV cut-off for PET activity |

| Choe (2011) [46] | Hip arthroplasty | SET 2400 W machine (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM Correction: attenuation |

NS |

| Forrest (2006) [42] | Hip arthroplasty | Siemens ECAT EXACT-31 PET scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET |

Dose: 250 MBq Scan time: static sweep 45 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: filtered back-projection algorithm with a Hanning filter Correction: attenuation, scattered and random coincidences |

Manual On PET images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Kumar (2016) [45] | Hip arthroplasty | Biograph 64 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 150 – 180 MBq Scan time: an early blood pool phase and delayed uptake phase images were acquired immediately and 20–30 min |

Algorithm: OSEM |

Manual On PET images Based on observed PET activity |

| Piert (1999) [39] | Hip arthroplasty | Advance PET scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) | PET |

Dose: 370 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 6 × 30 s, 5 × 300 s, 3 × 600 s) |

NS |

Manual On CT images Input function was derived from arterial samples out of the A. Radialis |

| Raijmakers (2014) [91] | Hip arthroplasty | EXACT HR + scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET |

Dose: 100 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (6 × 5 s, 6 × 10 s, 3 × 20 s, 5 × 30 s, 5 × 60 s, 8 × 150 s, and 6 × 300 s) |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: filtered back-projection with a Hanning filter Correction: decay, scatter, randoms, and (measured) photon attenuation |

Manual On PET images Based on anatomical regions |

| Temmerman (2008) [41] | Hip arthroplasty | EXACT HR + scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET |

Dose: 100 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (6 × 5 s, 6 × 10 s, 3 × 20 s, 5 × 30 s, 5 × 60 s, 8 × 150 s, and 6 × 300 s) |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: filtered back-projection with a Hanning filter Correction: decay, scatter, randoms, and (measured) photon attenuation |

Manual On PET images Based on anatomical regions |

| Tezuka (2020) [92] | Hip arthroplasty | Celesteion™ scanner (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 45 min after injection |

NS |

Manual On CT images According to pre-existing radiographical areas (Gruenn zones) |

| Ullmark (2009) [40] | Hip arthroplasty | Siemens/CTI Exact HR + scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: static sweep 30 min after injection |

Algorithm: filtered back-projection Correction: attenuation, scatter, and decay |

NS |

| Ullmark (2013) [43] | Hip arthroplasty | Discovery ST (General Electrics, Milwaukee, Tennessee) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: static sweep 30 min after injection |

Algorithm: filtered back-projection Correction: attenuation, scatter, and decay |

Semi-automatic According to a polar map method dividing the hip into various separate regions |

| Ullmark (2020) [44] | Hip arthroplasty | Discovery ST (General Electrics, Milwaukee, Tennessee) | PET/CT |

Dose: 140 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM with 2 iterations and 21 subsets Correction: attenuation, scatter, and decay |

Semi-automatic According to a polar map method dividing the hip into various separate regions |

| Mechlenburg (2013) [93] | Hip dysplasia (periacetabular osteotomy) |

Biograph 40 (Siemens Healthcare, Knoxville, TN) Biograph 40 Truepoint (Siemens Healthcare, Knoxville, TN) |

PET/CT |

Dose: NS Scan time: dynamic sequence of 90 min. Plasma IF was obtained via forty arterial blood samples |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Corrections: random events, detector sensitivity, dead time, attenuation, and scatter |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Waterval (2010) | Hyperostosis cranialis interna | Siemens Biograph mCT-4R 64 slice (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 150 MBq Scan time: 60 min after injection |

Matrix: 256 × 256 with a Gaussian filter of 5 mm Algorithm: filtered back-projection |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Jenkins (2017) | Lower back pain | 3 T Signa PET/MR imaging scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 170.2 ± 29.6 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Correction: decay, attenuation, scatter and dead time |

Manual Fixed-sized VOIs Based on anatomical locations |

| Kobayashi (2013) [23] | Osteoarthritis (hip) | SET-2400W instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM Correction: attenuation |

NS |

| Kobayashi (2015) [25] | Osteoarthritis (hip) | SET 2400 W instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM |

NS |

| Kobayashi (2015) [30] | Osteoarthritis (hip) | SET-2400W instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM Correction: attenuation |

Manual |

| Tibrewala (2019) [96] | Osteoarthritis (hip) | SIGNA 3 T time-of-flight (TOF) PET/MR (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 247.97 ± 19.82 MBq Scan time: 45 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 6 × 30 s, 10 × 240 s) |

NS | NS |

| Yellanki (2018) [25, 26] | Osteoarthritis (hip) | NS (part of CAMONA study) | PET/CT |

Dose: NS Scan time: static sweep 90 min after injection |

Corrections: attenuation, scatter, scanner dead time, and random coincidences |

Manual and semi-automatic On CT images Based on a threshold of 150 HU and anatomical boundaries |

| Jena (2022) [24] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | Siemens ET/MRI system, Biograph mMR (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 185–370 MBq Scan time: static sweep 45 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM with 3 iterations and 21 subsets, Gaussian smoothing |

Manual On MRI images Based on anatomical locations |

| Jena (2023) [29] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | Siemens ET/MRI system, Biograph mMR (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 185–370 MBq Scan time: static sweep 45 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM with 3 iterations and 21 subsets, Gaussian smoothing |

Manual On MRI images Based on anatomical locations |

| Mackay (2021) [97] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | 3 T PET-MRI platform (GE Signa PET-MR, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 50 min dynamic sequence |

Algorithm: TOF |

Manual On MRI images |

| Savic (2016) [28] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | 3 T PET-MR scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 340.4 MBq Scan time: 60 dynamic sequence (12 × 10,s 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Algorithm: OSEM, TOF |

Manual On MRI images Image-derived input function obtained from A. poplitea |

| Tibrewala (2020) [27] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | SIGNA 3 T time-of-flight (TOF) PET-MRI (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 294.87 ± 59.78 MBq Scan time: dynamic sequence for 60 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM 4 iterations and 28 subsets, TOF | NS |

| Watkins (2021) [98] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | 3 T whole-body time-of-flight hybrid PET/MRI (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 93 ± 4.4 MBq Scan time: 50 min dynamic sequence (20 × 1 s, 10 × 10 s, 10 × 30 s, 5 × 1 min 1 × 2 min) |

Algorithm: TOF |

Manual On MRI images According to existing radiological score subdivisions Image-derived input function obtained from A. poplitea |

| Watkins (2022) [99] | Osteoarthritis (knee) | 3 T PET-MRI system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | PET/MRI |

Dose: 89 ± 7.0 MBq Scan time: 50 min (20 × 1 s, 10 × 10 s, 10 × 30 s, 5 × 1 min 1 × 2 min) |

Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On MRI images According to grid zones based on anatomy |

| Christersson (2018) [58] | Osteomyelitis |

GE Discovery ST16 hybrid (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 2 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

NS | NS |

| Freesmeyer (2014) [56] | Osteomyelitis | Biograph mCT 40 (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: Dynamic sequence of 5 min was performed after injection. Static sweep was then performed 30–45 min post-injection |

Matrix: 200 × 200 |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries and on CT affected areas |

| Reinert (2022) [57] | Osteomyelitis (jaw) | Biograph mCT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 4 MBq/kg (284 ± 137 MBq) Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

NS |

Semi-automatic On PET images Based on observed PET activity |

| Kubota (2015) [64] | Osteonecrosis (femoral head) | SET-2400W (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM Corrections: attenuation |

NS |

| Aratake (2009) [65] | Osteonecrosis (knee) | SET-2400W (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

NS | NS |

| Schiepers (1998) [66] | Osteonecrosis (femoral head) | ECAT-931 PET (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA) | PET |

Dose: 300 – 370 MBq Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

NS | NS |

| Frost (2008) [71] | Osteoporosis | ECAT-951R PET (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA) | PET |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Corrections: attenuation |

Semi-automatic toll based on a threshold of 50% of the maximum bone activity in each image set Image-derived input function from the aorta abdominalis corrected using venous blood samples |

| Jassel (2019) [67] | Osteoporosis | GE Discovery (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 90 MBq for the lumbar spine scan and 180 MBq for the hip scan Scan time: dynamic scan for 60 min after injection |

Algorithm: Back-projection using a 6.3-mm Hanning filter Corrections: Scattered radiation and attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Park (2023) [100] | Osteoporosis | GE Discovery (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 2.2 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 90 min after injection |

NS |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Puri (2021) [101] | Osteoporosis | GE Discovery PET-CT scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 180 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Corrections: decay, attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Arterial input function was estimated using a semi-population method |

| Rhodes (2020) [102] | Osteoporosis | GE Discovery STE, VCT, RX, and 690/710 (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 2.2 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 90 min after injection |

NS |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries with 100 HU threshold for whole bone and 300 HU for cortical bone |

| Uchida (2009) [103] |

Osteoporosis (Alendronate treatment) |

Advance system (GE Healthcare) | PET |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 50 min after injection |

Algorithm: iterative, 14 subsets and 2 iterations |

Manual with fixed-sized VOI On PET images |

| Frost (2003) [104] |

Osteoporosis (Risendronate treatment) |

ECAT-951R PET (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA) | PET |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Algorithm: back-projection with Hann filter Corrections: attenuation |

Semi-automatic tool based on a threshold of 50% of the maximum bone activity in each image set Image-derived input function from the aorta abdominalis corrected using venous blood samples |

| Frost (2011) [68] |

Osteoporosis (Teriparatide treatment) |

GE Discovery PET/CT (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 24 s) followed by a static scan of the femur and pelvis |

Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Input function was estimated using a semi-population curve method |

| Siddique (2011) [105] |

Osteoporosis (Teriparatide treatment) |

GE Discovery PET/CT scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

NS |

Manual On PET/CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Arterial plasma input function was calculated using a semi-population method, corrected with venous samples |

| Fushimi (2022) [106] |

Osteoporosis (Zolendronic acid & denosumab treatment) |

Biograph mCT 64-slice PET/CT (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Knoxville, TN) | PET/CT |

Dose: 5 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

Algorithm: TOF |

Manual Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Puri (2012) [69] |

Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) |

GE Discovery ST scanner (General Electric medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 90 MBq for lower spine scan and 180 MBq for the hip scan Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s and 14 × 240 s) |

Mode: 2-dimensional Corrections: scatter, attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Cook (2000) [21] |

Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) |

ECAT-951R PET (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA) | PET |

Dose: 180 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s and 14 × 240 s) |

Correction: attenuation |

Manual Arterial input function was based on a mean population input function corrected for plasma samples obtained at 30, 40 and 50 min |

| Frost (2004) [107] | Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | ECAT-951R PET (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA) | PET |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Correction: attenuation |

Semi-automatic tool based on a threshold of 50% of the maximum bone activity in each image set Image-derived input function obtained from the abdominal aorta and corrected using venous blood samples |

| Frost (2009) [108] | Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | ECAT-951R PET (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA) | PET |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Correction: attenuation |

Semi-automatic tool based on a threshold of 50% of the maximum bone activity in each image set Image-derived input function obtained from the abdominal aorta and corrected using venous blood samples |

| Puri (2013) [70] | Osteoporosis (postmenopausal bone turnover) | Discovery ST (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 90 MBq for the lumbar spine scan and 180 MBq for the hip scan Scan time: dynamic sequence for 60 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Mode: 2-dimensional Corrections: attenuation |

Semi-automatic On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Cook (2002) [109] | Paget’s disease | ECAT-951R PET scanner (Siemens/CTI Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET |

Dose: 180 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s,14 × 240 s) |

Correction: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Image-derived input function from the aorta |

| Installe (2015) | Paget’s diseases | ECAT 961 PET scanner (Siemens/CTI Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET |

Dose: 397 ± 40.7 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s,14 × 240 s) |

Correction: dead time, random coincidences, scatter, decay, attenuation |

Manual On PET images |

| Waterval (2013) [35] | Otosclerosis | Gemini TF (Philips, Best, The Netherlands) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: 60 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM Corrections: random events, scattered radiation and attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Draper (2012) [36] | Patellofemoral pain | GE Discovery LS (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185–370 mBq (2.96 mBq/kg) Scan time: 69 ± 23 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Time/bed position: 5 min acquisition Algorithm: OSEM |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Graf (2020) [74] | Primary hyperparathyroidism and brown tumors |

Discovery VCT, Discovery STE (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 100 MBq Scan time: 30 min after injection |

Matrix: 256 × 256 Algorithm: OSEM |

Manual Unclear on which images Based on tumor locations |

| Hochreiter 2019 [110] | Reverse shoulder arthroplasty | Discovery 710 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WN) | PET/CT |

Dose: 150 MBq Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

Algorithm: OSEM |

Manual On CT images Based on a 50% threshold of the PET activity in the area of interest |

| Jonnakuti (2018) [111] | Rheumatoid arthritis (knee arthrosis) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Manual On CT images Based on a threshold of 150 HU and on anatomical boundaries |

| Park (2021) [33] | Rheumatoid arthritis | Biograph mCT 20 (Siemens Healthineers, Knoxville, TN, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 57 ± 5 min after injection |

Algorithm: Iterative reconstruction algorithm Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Reddy (2023) [112] | Rheumatoid arthritis | Biograph 64 Hybrid PET/CT Imaging System (Siemens Medical Solutions, Inc. Malvern, PA, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 2.96 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 90 min after injection |

Corrections: scatter, random coincidences, dead time, attenuation |

Manual On CT image Based on anatomical boundaries and thresholds of 150 HU up to 1500 HU |

| Watanabe (2016) [34] | Rheumatoid arthritis | SET 2400 W (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On PET images Based on observed PET activity and anatomical boundaries |

| Aaltonen (2020) [14] | Renal osteodystrophy | Discovery VCT scanner (GE Healthcare) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Image-derived input function from the abdominal aorta |

| Aaltonen (2021) [13] | Renal osteodystrophy | Discovery VCT scanner (GE Healthcare) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (24 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Image-derived input function from the abdominal aorta |

| Frost (2013) [17] | Renal osteodystrophy | GE Discovery PET/CT scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) | PET/CT |

Dose: 90 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (12 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Corrections: attenuation |

Semi-automatic tool based on a threshold of 50% of the maximum bone activity in each image set Image-derived input function obtained from the abdominal aorta and corrected using venous blood samples |

| Fuglo (2023) [113] | Renal osteodystrophy | Siemens Biograph mCT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 200 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (4 × 30 s, 8 × 60 s, 12 × 240 s) |

Matrix: 400 × 300 Algorithm: OSEM, 4 iterations and 21 subsets |

Manual Based on anatomical boundaries Imaged derived input function from the A. Iliaca |

| Vrist (2021) [15] | Renal osteodystrophy | Siemens Biograph mCT-4R 64 slice PET/CT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 150 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (203x, 12 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Correction: attenuation |

Manual On PET/CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Image-derived input function obtained from the left ventricle and corrected using venous blood samples |

| Vrist (2022) [16] | Renal osteodystrophy | Siemens Biograph mCT-4R 64 slice PET/CT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | PET/CT |

Dose: 150 MBq Scan time: 60 min dynamic sequence (203x, 12 × 5 s, 4 × 30 s, 14 × 240 s) |

Correction: attenuation |

Manual On PET/CT images Based on anatomical boundaries Image-derived input function obtained from the left ventricle and corrected using venous blood samples |

| Constantinescu (2020) [50] | Spinal interbody fusion (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) | Discovery LS 690/710 (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) | PET/CT |

Dose: 2.2 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 90 min after injection |

Corrections: attenuation, scatter, random coincidences, and scanner dead time |

Manual and semi-automatic On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Peters (2015) [51] | Spinal interbody fusion (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) | Gemini TF PET/CT (Philips, The Netherlands) | PET/CT |

Dose: 156–263 MBq Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

Algorithm: TOF Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images |

| Peters (2015) [52] | Spinal interbody fusion (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) | Gemini TF PET/CT (Philips, The Netherlands) | PET/CT |

Dose: 156–214 MBq Scan time: 30 min dynamic sequence (6 × 5 s, 3 × 10 s, 9 × 60 s, 10 × 120 s) |

Algorithm: blob-os-TF |

Manual On CT images Image-derived input function obtained from the abdominal aorta |

| El Yaagoubi (2022) [49] | Spinal fusion (aseptic pseudoarthrosis) | Discovery IQ (Discovery IQ; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WN) | PET/CT |

Dose: 2.2 MBq/kg Scan time: static sweep 60 min after injection |

NS |

Manual On PET images Based on observed PET activity |

| Lee (2019) [55] | Surgical-site infection | Biograph mCT 128 (Siemens Healthcare, Knoxville, TN) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185 MBq Scan time: Early-phase imaging was performed after injection (sequence times not reported). Static sweep was performed approximately 45 min post-injection |

Algorithm: Iterative algorithm using point-spread-function modeling and time-of-flight reconstruction Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Lee (2013) [63] | Temporomandibular joint disorder | Biograph™ 40 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Hoffman Estates, IL) | PET/CT |

Dose: 185–370 MBq Scan time: static sweep 40 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Algorithm: OSEM Correction: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Base on anatomical locations |

| Suh (2018) [62] | Temporomandibular joint disorder | Discovery (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) | PET/CT |

Dose: 5.18 MBq/kg Scan time: 60 min after injection |

Matrix: 128 × 128 Mode: 3-dimensional Algorithm: ordered-subset iteration algorithm Corrections: attenuation and scatter |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Lundblad (2017) [47] | Tibia bone healing (complex fractures, osteomyelitis, osteotomies) |

Biograph 64 Truepoint TrueV (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) |

PET/CT |

Dose: NS Scan time: Dynamic sequence of 45 min after injection, followed by static sweep at 60 min |

Algorithm: “suitable reconstruction algorithm was determined via phantom studies” Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |

| Lundblad (2015) [114] | Tibia bone healing (with Taylor Spatial Frame) |

Biograph 64 Truepoint TrueV (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) Discovery 710 and Discovery MI DR (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) |

PET/CT |

Dose: 2 MBq/kg Scan time: Dynamic sequence of 45 min after injection, followed by static sweep after 60 min |

Algorithm: suitable reconstruction algorithm was determined via phantom studies Corrections: attenuation |

Manual On CT images Based on anatomical boundaries |