Abstract

Accurately imaging adult cardiac tissue in its native state is essential for regenerative medicine and understanding heart disease. Current fluorescence methods encounter challenges with tissue fixation. Here, we introduce the 3D-NaissI (3D-Native Tissue Imaging) method, which enables rapid, cost-effective imaging of fresh cardiac tissue samples in their closest native state, and has been extended to other tissues. We validated the efficacy of 3D-NaissI in preserving cardiac tissue integrity using small biopsies under hypothermic conditions in phosphate-buffered saline, offering unparalleled resolution in confocal microscopy for imaging fluorescent small molecules and antibodies. Compared to conventional histology, 3D-NaissI preserves cardiac tissue architecture and native protein epitopes, facilitating the use of a wide range of commercial antibodies without unmasking strategies. We successfully identified specific cardiac protein expression patterns in cardiomyocytes (CMs) from rodents and humans, including for the first time ACE2 localization in the lateral membrane/T-Tubules and SGTL2 in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. These findings shed light on COVID-19-related cardiac complications and suggest novel explanations for therapeutic benefits of iSGLT2 in HFpEF patients. Additionally, we challenge the notion of "connexin-43 lateralization” in heart pathology, suggesting it may be an artifact of cardiac fixation, as 3D-NaissI clearly revealed native connexin-43 expression at the lateral membrane of healthy CMs. We also discovered previously undocumented periodic ring-like 3D structures formed by pericytes that cover the lateral surfaces of CMs. These structures, positive for laminin-2, delineate a specific spatial architecture of laminin-2 receptors on the CM surface, underscoring the pivotal role of pericytes in CM function. Lastly, 3D-NaissI facilitates the mapping of native human protein expression in fresh cardiac autopsies, offering insights into both pathological and non-pathological contexts. Therefore, 3D-NaissI provides unparalleled insights into native cardiac tissue biology and holds the promise of advancing our understanding of physiology and pathophysiology, surpassing standard histology in both resolution and accuracy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-025-05595-y.

Keywords: Cardiac tissue, Fluorescence confocal imaging, Cardiomyocytes, Connexin-43, Pericytes, ACE2, SGTL2, Claudin-5

Introduction

The quest for successfully regenerating adult cardiac tissue, a paramount objective in treating end-stage heart failure, has primarily centered around cell-dependent strategies. Despite early optimism, efforts such as stem cell engraftment and enhancing resident cardiomyocyte (CM) proliferation have fallen short, often leading to arrhythmia and insufficient functional recovery [1–3]. In contrast, 3D cardiac tissue engineering, which considers the complex interplay between diverse cell populations and the extracellular matrix, presents a promising alternative. However, its potential hinges on clinical validation, necessitating further research. Paradoxically, while extensive studies focus on regenerating pathological cardiac tissue, our understanding of the 3D organization of native cardiac tissue remains a mystery—a crucial gap for engineering functional cardiac tissue faithful to native conditions.

Cardiology's insights into the 3D architecture of the mammalian heart largely rely on noninvasive macroscopic imaging like X-rays and echocardiography, valuable for overall structure but lacking at the microscopic level. Recent advances in tissue clearing techniques [4–7], though significant, raise concerns about preserving native tissue architecture due to the risks associated with chemical fixation. Conventional fixatives like paraformaldehyde (PFA) and glutaraldehyde (GA) pose risks of altering tissue biochemistry, inducing artifacts, and causing epitope masking, particularly challenging in solid cohesive tissues. Crosslinking during fixation (protein–protein, DNA-DNA, DNA-RNA, or DNA–protein crosslinking) can lead to various artifacts, affecting not only tissue-clearing but also histopathology methods, which are considered the gold standard for clinical diagnosis. Mutational signatures associated with formalin fixation on patient samples [8] and alterations in tissue biochemistry revealed by Raman spectroscopy [9] highlight concerns in conventional histopathology examination. Moreover, epitope masking caused by fixatives, a well-known challenge in histopathology [10], can hinder protein recognition in immunodetection methods, especially in solid cohesive tissues. Fixation artifacts are also observed in electron microscopy, necessitating reliable artifact-free methods for tissue examination. Fixation's influence on protein localization, demonstrated by recent studies [11], emphasizes the need for live-cell imaging techniques to closely resemble the native state [12]. Despite their known limitations, fixation methods, developed to capture a snapshot of cells or tissues, extensively persist in cell biology without reassessing the native biological sample, lacking means to image tissues in their closest native state.

Addressing these limitations, we introduce 3D-NaissI (Native Tissue Imaging), a novel method for fresh-tissue immunolabeling applicable to small biopsies, allowing fluorescent labeling without fixation or permeabilization. Beyond cardiac tissue, we also validated its utility to brain, skin, and gut biopsies. Rapid, cost-effective, and autofluorescence-free, 3D-NaissI identifies previously overlooked 3D structures within cardiac tissue. It enabled high-resolution confocal imaging of traditionally challenging cardiac proteins, surpassing formalin-fixed processing. When compared to standard histological methods, 3D-NaissI exposed interpretation errors, challenging established ideas in cardio-pathology, such as the concept of "Cx43 lateralization. Finally, applied successfully in cardiac autopsies, 3D-NaissI facilitates mapping native protein expression in the human heart with minimal artifacts aside from the patient's clinical data. This innovative approach promises to fill the existing gap by providing a means to image tissues in their closest native state, significantly advancing our understanding and applications in the field of tissue imaging.

Results

Fresh native cardiac tissue biopsies: preparation, staining and imaging

The current gold standard for ex vivo cardiac tissue culture relies on living myocardial slices (LMS), optimized for functional studies to maintain adult cardiac tissue for extended periods [13]. However, this conditioning is geared towards functional assessments, such as contraction and electrical conduction, rather than imaging. Typically, imaging is performed using PFA-fixed LMS cryosections [14, 15].

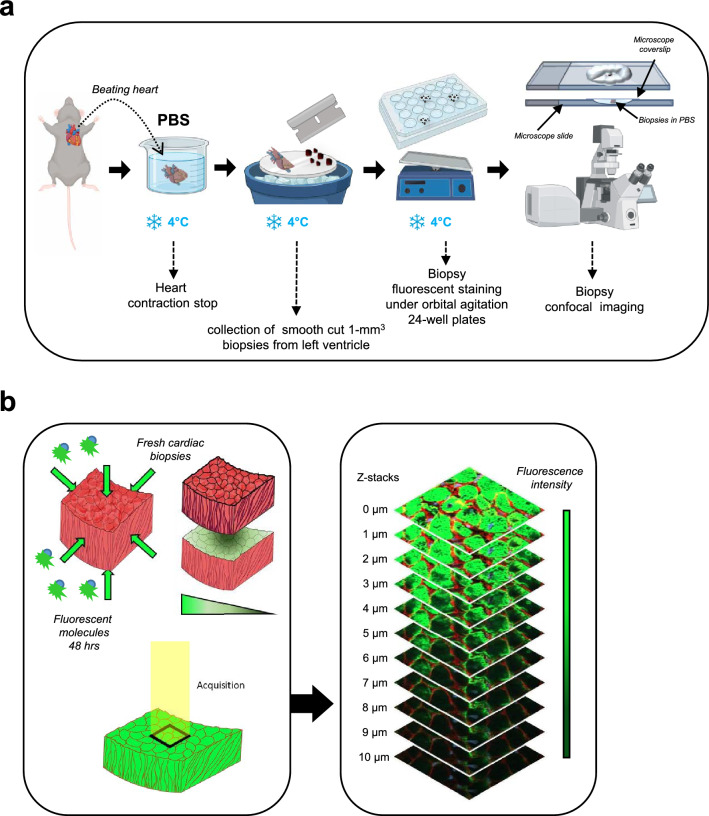

In this study, our objective was to develop a technique that optimally preserves cardiac tissue integrity for short-term imaging in a state closely resembling its native condition, eliminating the need for functional preservation. Hence, we developed a protocol referred to as the 3D-NaissI (Native tissue Imaging) method (Fig. 1a). Cardiac tissue sampling from mice followed a previously described approach for preserving the subcellular architecture of cardiomyocytes (CMs) in electron microscopy imaging [16]. Smoothly cut 1-mm3 fresh biopsies were rapidly collected from the left ventricular myocardium of mice under hypothermic conditions at 4 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1) and maintained in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C until imaging (Fig. 1a). The small biopsy size is crucial for subsequent tissue penetration of fluorescent probes, although it may lead to section artifacts (tissue tearing), necessitating the preparation of multiple biopsies from each sample.

Fig. 1.

Schematic workflow of 3D-NaissI method. a Procedure from beating heart retrieval to biopsy preparation for confocal imaging. b Confocal imaging of fluorescent staining in fresh cardiac biopsies and z-stack acquisitions

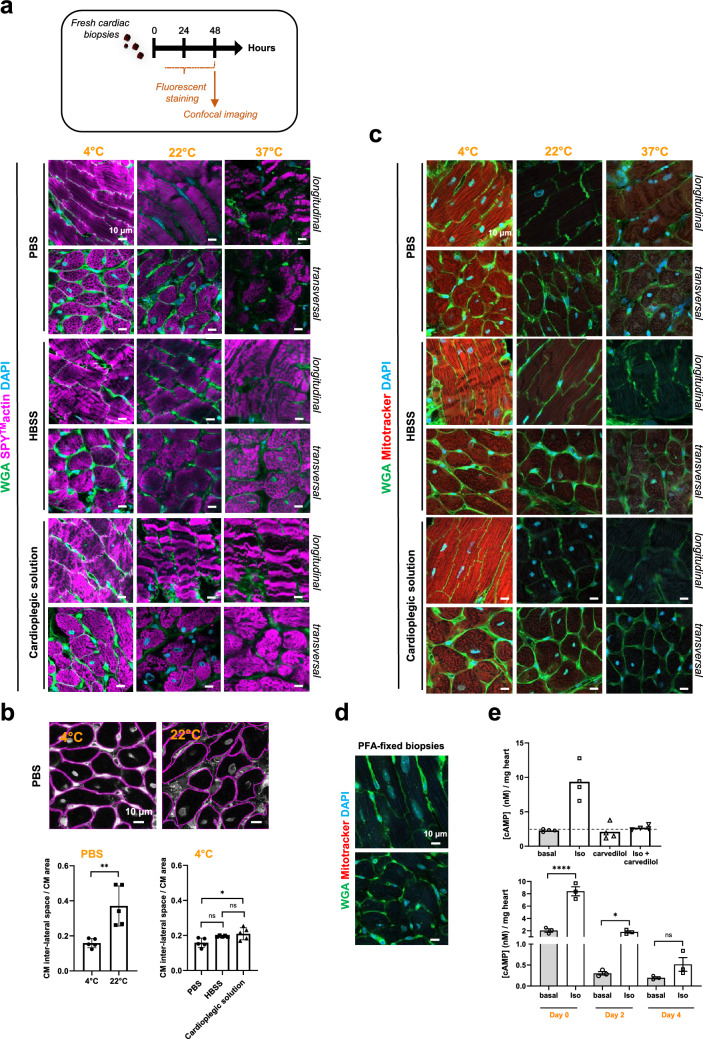

We first conducted a thorough qualitative and quantitative evaluation of staining solutions on fresh biopsies at different temperatures. Direct fluorescent staining using small fluorescent molecules was prioritized for their enhanced tissue penetration. Fresh cardiac biopsies were incubated for 48 h in the dark with agitation in 24-well plates, using PBS, Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS), or a cardioplegic solution at 4 °C, 22 °C (room temperature), or 37 °C. Stained biopsies were mounted and immobilized for confocal imaging. To prevent tissue edge damages, the top layers of the biopsies were excluded from image acquisition (See Methods), and 1 µm stacks were acquired until staining loss occurred (Fig. 1b). Related Z-stacks were compared among the different samples. Fluorescent staining may exhibit heterogeneity due to the small size and non-oriented nature of the biopsies (Supplementary Fig. 2), necessitating multiple samples per condition for a comprehensive view of the tissue. The cytoarchitecture of the CMs, reflected by both actin (SPY™-actin cell permeable-live cell fluorescent probe) and Wheat-Germ-Agglutinin (WGA)-surface stainings, was well-preserved at 4 °C, regardless of the buffer used (Fig. 2a). At 22 °C, tissue disorganization had already begun, hindering fluorescent staining. At 37 °C, extensive damage occurred in all buffers, rendering the tissue unsuitable for further use. These findings were further supported by a quantitative assessment of the CM inter-lateral space area (Fig. 2b) (See Methods), which typically expands in pathophysiology due to cardiac tissue disorganization and resulting in a loss of tissue cohesion [17]. Due to the variability in fluorescent staining among different buffers, only a few PBS quantifications were performed at 22 °C. The results showed a significantly higher space at 22 °C compared to 4 °C in PBS (Fig. 2b, left panel), indicating loss of tissue cohesion. Conversely, the inter-cellular space at 4 °C remained well-maintained across all preservation buffers, albeit with a slight increase observed in HBSS and the cardioplegic condition (Fig. 2b, right panel). Larger cardiac biopsies could also be processed in PBS at 4 °C for confocal fluorescence imaging (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Optimizing experimental conditions to preserve stability, integrity, and viability of fresh cardiac tissue biopsies using the 3D-NaissI method. a Stability-integrity of fresh cardiac biopsies from mice qualitatively evaluated by confocal imaging following 48 h of fluorescent staining with cell surface probe (wheat germ agglutinin-WGA), cytoskeletal actin (SPY™-actin) and nuclei (DAPI) at 4, 22 or 37 °C and in PBS, HBSS or a cardioplegic solution. Images illustrate cardiomyocyte (CM) cytoarchitecture under the different conditions and are representative of 3–5 independent experiments (5 mice). b Stability-integrity of fresh cardiac biopsies assessed by quantification of the inter-CM space (indicative of the cardiac tissue cohesion) in fluorescent-WGA-stained fresh biopsies at 4 or 22 °C in PBS, HBSS or a cardioplegic solution. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 5 mice (5–10 biopsies/mouse, 1 image /biopsy), one-way ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc test. c Mitochondria viability in fresh cardiac biopsies from mice qualitatively evaluated by confocal imaging following 48 h of fluorescent staining with cell surface probe (WGA)/Mitochondria membrane potential probe (Mitotracker) and nuclei (DAPI) at 4, 22 or 37 °C and in PBS, HBSS or a cardioplegic solution. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments (3 mice). d Negative control for mitotracker probe staining using paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed, non-living cardiac biopsies. e Viability of fresh cardiac biopsies from mice assessed by measuring β-adrenergic activity of the tissue. Upper panel: cAMP production quantified in biopsies stimulated or not (basal) with 10 µM isoproterenol (ISO) or 10 µM carvedilol alone or in combination for 30 min at room temperature. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of 4 different biopsies from one mouse and are expressed as cAMP concentration (nM)/mg heart. Lower panel: cAMP production quantified in fresh cardiac biopsies collected immediately (Day 0), or 2 (Day 2), or 4 (Day 4) days after collection and stimulated or not (basal) with 10 µM isoproterenol (ISO) for 30 min at room temperature. Data are mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 mice (3–4 biopsies/mouse), one-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak’s post-hoc test. (* P < 0.05; **** P < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant)

Fresh native cardiac tissue biopsies: stability-viability

Fresh cardiac biopsies stored in PBS at 4 °C demonstrated sustained tissue stability for at least 10 days, as evidenced by consistent CM inter-lateral space and CM area (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Likewise, in a similar setting, sarcomeric α-actinin expression, a constituent of the CM contractile apparatus, remained stable up to 10 days (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Optimal preservation of fresh cardiac biopsies at 4 °C was further confirmed using the MitoTracker probe (Fig. 2c). Positive fluorescent MitoTracker labeling, indicative of viable mitochondria, was observed in biopsies at 4 °C in all buffers. In contrast, no labeling was observed at 22 °C and 37 °C, indicating loss of tissue viability. Notably, mitochondria viability persisted for at least 7 days at 4 °C (Supplementary Fig. 5a). As expected, MitoTracker fluorescence was absent in PFA-fixed biopsies, confirming loss of mitochondria viability (Fig. 2d). Similarly, plasma membrane integrity in viable CMs, assessed using the potentiometric fluorescent dye di-8-ANEPPS, remained evident for up to 10 days only in whole biopsy CM (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These results were supported by a quantitative assessment of the β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR)/Adenylyl-cyclase/cAMP signaling pathway (Fig. 2e). Stimulation of freshly collected heart biopsies with isoproterenol (nonselective β-agonist) at room temperature for 30 min resulted in significant cAMP production, which was completely blocked by co-stimulation with carvedilol (β-antagonist), confirming β-AR dependence (Fig. 2e, upper panel). This β-AR response, encompassing G protein and adenylyl cyclase enzymatic activity, was maintained in biopsies stored in PBS at 4 °C for up to 2 days but was lost after 4 days (Fig. 2e, lower panel), aligning with short-term preservation of cellular activity under cold exposure. These results were further supported by the rapid decline in GAPDH enzyme expression during the first 2 days in the cardiac tissue samples stored in PBS at 4 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

In summary, these findings underscore that fresh cardiac biopsies stored and stained at 4 °C in PBS exhibit superior preservation of tissue integrity. Notably, this approach effectively maintains both tissue stability and viability, with structural proteins exhibiting greater stability than enzymatic counterparts. These optimized experimental conditions were consistently employed for all subsequent experiments using the 3D-NaissI method.

3D-NaissI method: comparison with common histological techniques

To assess the 3D-NaissI method against conventional histological approaches in cardiac tissue fluorescence imaging, we compared WGA and DAPI small-fluorescent molecule staining on fresh tissue (3D-NaissI), PFA-prefixed tissue, and Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue. Native tissue exhibited minimal autofluorescence across various filters, contrasting with significant autofluorescence in PFA or FFPE tissue (Supplementary Fig. 6). These outcomes align with the expected autofluorescent properties resulting from crosslinking with amines and proteins in the presence of PFA or formalin. This discrepancy underscores the 3D-NaissI method's substantial enhancement of the fluorescent signal-to-noise ratio. Beyond signal quality, using native fresh tissue for cardiac imaging surpasses classical histological methods by better preserving cellular and tissue integrity, as qualitatively shown in Fig. 3a. Accordingly, the CM inter-lateral space (Fig. 3b, left panel) and the CM area (Fig. 3b, right panel) were significantly smaller in PFA-fixed and FFPE tissues compared to fresh biopsies, indicating compromised tissue cohesion and cellular alterations in the presence of fixatives. These alterations may influence the intricate architecture of CMs, protein expression, and localization, critical in cardiology research. In conclusion, conventional histological techniques considerably shrink cardiac tissue and are not appropriate for precisely studying cellular architecture and spatial organization of proteins in situ compared to 3D-NaissI method.

Fig. 3.

Performance of 3D-NaissI compared to conventional histological techniques. a Representative confocal images of fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and DAPI-staining in cardiac tissue (left ventricles) from fresh cardiac biopsies (3D-NaissI method), PFA-fixed-tissue or Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue. b Quantification of inter-CM space (indicative of the cardiac tissue cohesion) and CM area in fluorescent-WGA-stained cardiac tissue using fresh cardiac biopsies (3D-NAissI; PBS, 4 °C), PFA-fixed tissue or FFPE-tissue. Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 mice (7–10 biopsies/mouse, 1 image /biopsy), one-way ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc test

3D-NaissI method: optimization of fluorescent staining and immunostaining

We optimized fluorescent staining of fresh cardiac tissue at 4 °C in PBS using small molecules. A 30-min labeling allowed visualization of DAPI, Alexa Fluor 488-WGA, and Alexa Fluor 594-mitotracker fluorescence. Extended incubation times (24–48 h) resulted in an optimal imaging depth of ~ 40 µm (Supplementary Fig. 7), aligning with confocal microscope capabilities. The signal-to-noise ratio was improved at greater depths by linearly increasing laser power, enabling depths imaging of up to 100 µm (Supplementary Fig. 8).

We next assessed the suitability of small biopsies in the 3D-NaissI method for immunostaining. Due to inherent random sectioning and the large size of CMs, the fresh biopsies comprise both intact and sectioned CMs. Thus, we hypothesized that, without permeabilization, a selective antibody targeting an intracellular CM protein could label sectioned CMs while leaving intact CMs unlabeled (Fig. 4a). In agreement, fresh biopsies incubated with an anti-α-actinin antibody for 48 h followed by a 48 h-incubation with a fluorescent complementary secondary antibody, showed specific α-actinin staining in sectioned CMs, while intact CMs remained unlabeled (Fig. 4b). In contrast, PFA-fixed biopsies exhibited positive α-actinin staining in all CMs (Fig. 4c), agreeing with PFA-induced permeabilization. Saponin permeabilization allowed antibody penetration into intact cells without significant tissue disruption (Supplementary Fig. 9a), as demonstrated by similar measurements of the CM inter-lateral space (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Immunofluorescence imaging depth also linearly increased with extended incubation time, but optimal staining depth did not exceed 20 µm compared to small molecule staining (Supplementary Fig. 10a), likely influenced by antibody size. It is worth noting that the duration for antibody-based fluorescent staining can be streamlined to just 48 h prior to imaging (Supplementary Fig. 10b). These depth variations were primarily influenced by fluorescent molecule size rather than laser penetration properties, as they persisted under similar laser parameters (Supplementary Fig. 11). Notably, immunofluorescent labeling on fresh tissue demonstrated remarkable selectivity for most tested antibodies, regardless of the manufacturer, thus supporting the hypothesis of frequent epitope masking in tissues when using fixatives.

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescent staining of fresh cardiac biopsies using 3D-NaissI method. a Schematic illustrating the hypothetical antibody penetrance in fresh cardiac biopsies, highlighting staining differences between whole and transected cardiomyocytes. b Representative images (3 independent experiments) display XY, XZ, YZ projections and associated Z-stacks, illustrating fluorescent staining of a whole cardiomyocyte (left panel) or a sectioned cardiomyocyte (right panel) for wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), α-actinin, DAPI in fresh cardiac biopsies (3D-NaissI, 2-month old male mice). Both cases exhibit WGA-rod shape surface staining, with a notable absence of α-actinin staining is observed exclusively in the whole cardiomyocyte. c Representative images (3 independent experiments) of fluorescent staining for WGA, α-actinin, DAPI in the cardiac tissue from 2-month-old male mice, highlighting the contrast in antibody penetrance between fresh biopsies (3D-NAissI) with whole cardiomyocytes and PFA-fixed- tissue with permeabilized cardiomyocytes

Native expression of cardiac proteins using 3D-NaissI method: advancing scientific comprehension and interpretations

To assess the efficacy of the 3D-NaissI method, we explored the native expression patterns of both well-known and less-known cardiac proteins in fresh biopsies (myocardium) from left ventricles of mice.

Connexin-43

We first examined connexin-43 (Cx43), a pivotal transmembrane protein in CM gap junctions essential for heart conduction, comparing conventional imaging of FFPE-cardiac tissues and the 3D-NaissI method. The imaging of FFPE-cardiac tissue confirmed the expected and distinct localization of Cx43 at the intercalated discs in control mice (Fig. 5a). This localization was further confirmed by quantifying the Cx43 fluorescent intensity along the lateral membrane (dystrophin-positive) and at the intercalated disk (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 12a). Intriguingly, the 3D-NaissI method unveiled an additional presence of Cx43 at the CM lateral membrane (Fig. 5a), resembling the documented "Cx43 lateralization" observed in injured hearts [18–20], which can be better visualized on larger image fields of the tissue (Supplementary Fig. 13). In these quantifications (Supplementary Fig. 13), it is worth noting that, unlike FFPE conditions, where dystrophin labeling is confined to the lateral membrane, 3D-NaissI also shows weaker labeling at the intercalated disc and sometimes in T-Tubules. This aligns with previous report of dystrophin expression in T Tubules, depending on the technique [21]. Hence, these results suggest that the 3D-NaissI method facilitates the detection of transmembrane proteins across all plasma membrane compartments of CMs.

Fig. 5.

Artifacts of “connexin 43 lateralization” in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE)-cardiac tissues revealed through 3D-NaissI. a, c Representative images of connexin-43 immunostaining in the presence of fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) in fresh-(3D-NaissI) or FFPE- cardiac tissue from 2-month old male X-linked muscular dystrophy (MDX) mice and their respective controls (C57BL6J OlaHsd). Zoomed-in images (right panels) illustrate the localization of connexin-43 at the lateral membrane or the intercalated disc of the cardiomyocyte. b, d Representative images and corresponding quantification of connexin-43 fluorescence intensity along the manual dotted trace (lateral membrane and intercalated disk) performed on confocal images of (b) dystrophin/Connexin-43/DAPI- or (d) Connexin-43/wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-stained Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) cardiac tissue or fresh cardiac biopsies (3D-NaissI) from 2-month-old male (b) control or (d) MDX mice. e Corresponding quantification of the inter-cardiomyocyte (CM) space in fluorescent-WGA-stained biopsies from a,c. Data are mean ± s.d. (e, FFPE) n = 2 mice /group; (e, 3D-NaissI) n = 1 mice/group (5–10 biopsies/mouse, 1 image /biopsy)

To comprehensively understand these findings, we extended our analysis to cardiac tissue from X-linked muscular dystrophy (MDX) mouse model, a model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy showcasing "Cx43 lateralization" [22, 23]. As anticipated, Cx43 lateralization was evident in both FFPE and fresh cardiac tissue from adult MDX mice (Fig. 5c, MDX). However, in fresh biopsies, MDX mice exhibited distinct Cx43 expression patterns, characterized by a more homogeneous yet punctuate distribution across the CM surface compared to the FFPE method (Fig. 5d), and contrasting with the large clusters observed in control mice (Fig. 5a, 3D-NaissI). While these results confirm issues with Cx43 expression/localization in the MDX mouse model, they demonstrate that that Cx43 lateralization is not pathology-specific but a hallmark of normal cardiac tissue in adult mice.

The absence of Cx43 immunostaining at the CM lateral membrane in FFPE-control mice may result from epitope masking, as it commonly occurs with this technical procedure [24], or restricted antibody access. This limitation may result from CM shrinkage and reduced lateral space between CMs induced by formalin fixation, as previously demonstrated (Fig. 3b). Accordingly, in MDX mice, the trend towards increased intercellular space in FFPE tissues (≥ 0.2; Fig. 5e) compared to control mice ( < 0.2) supported improved antibody access, facilitating the detection of Cx43 lateral staining. Further supporting this hypothesis, the increased intercellular space in MDX-FFPE tissues closely approached that observed in the 3D-NaissI method (Fig. 5e). These findings were substantiated in CM-specific Efnb1 KO mice, a model of tissue cohesion loss that we have previously described [25, 26]. In fact, a significant increase of the intercellular space was measured in FFPE-treated tissues from KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 14a), while the 3D-NaissI method demonstrated similar CM inter-lateral space in both wild-type (WT) and KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 14b). Similar disparities between FFPE tissue and fresh tissue were noted when quantifying CM area (Supplementary Fig. 14 c, d), further substantiating the phenomenon of CM shrinking under FFPE conditions. Consistent with the expanded inter-cellular space observed in FFPE tissues from KO mice, we observed Cx43-specific staining at both the intercalated disk and the lateral membrane in the KO mice, while a unique staining pattern in the intercalated disk was depicted in WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 14e). In contrast, the 3D-NaissI method unveiled Cx43 staining at both the CM lateral membrane (large patches) and the intercalated disc in control WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 14f). Notably, in KO mice, a more continuous labeling was observed all around the CM surface (Fig. 5d), contrasting with our initial description in cryo-fixed tissue [25].

In summary, the 3D-NaissI method distinctly revealed native Cx43 expression in both the lateral membrane and the intercalated disc of healthy adult CMs in situ, challenging the conventional characterization of "Cx43 lateralization" as pathology-specific. The “Cx43 lateralization”, specifically described in conventional FFPE-pathological cardiac tissues and not in normal tissues, more likely reflects a technical artifacts leading to tissue shrinking with a decreased CM area and increased CM inter-lateral space. Now, whether the pathological phenotype of the CM interlateral space or the CM area observed in FFPE-treated tissue is a technical idiosyncrasy or an exacerbation of the pathological phenotype remains an open question.

Claudin-5

Beyond the challenges encountered in visualizing proteins like Cx43 at the lateral side of CMs using conventional FFPE-processed heart sections, numerous transmembrane proteins remain difficult to image at the CM lateral membrane within the tissue context. Claudin-5, a tight junctional protein atypically localized at the CM lateral membrane [25, 27], exemplifies this challenge and has proven elusive in FFPE-cardiac tissue despite various protocols and antibodies, as illustrated in Fig. 6a, b. In contrast, the 3D-NaissI procedure applied to fresh cardiac biopsies allowed clear visualization of specific Claudin-5 staining on the inner face of the CM surface using an antibody targeting an intracellular epitope (Fig. 6a), while specific staining of the outer CM surface was achieved using an antibody directed against an extracellular epitope (Fig. 6b). Again, an additional advantage observed when utilizing fresh cardiac biopsies for fluorescent immunostaining with the 3D-NaissI method was the absence of nonspecific fluorescence. The effective visualization of transmembrane proteins, such as Claudin-5, at the CM lateral membrane within the tissue context demonstrates the superiority of the 3D-NaissI approach over conventional FFPE processing.

Fig. 6.

Visualization of the native expression pattern of Claudin-5 using the 3D-NaissI method. Representative confocal images (3 independent experiments) of Claudin-5 immunostaining in both fresh (3D-NaissI) or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cardiac tissue from 2-month-old male mice, in the presence of wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and DAPI (upper panels: transversal view; lower panels: longitudinal view). Antibodies targeting either an intracellular epitope (a, Acris antibody) or an extracellular epitope (b, Novus antibody) of Claudin-5 were used

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)

The need for detailed mapping of protein expression within human cardiac tissues becomes evident in understanding specific cardiac diseases, particularly in the context of the recent COVID-19 pandemic wherein patients may experience severe and long-term cardiac complications that remain not fully understood [28]. In this critical context, the mapping of ACE2 expression, the receptor for SARS-CoV-2, was crucial. While transcriptomic profiling of ACE2 in the human heart has been reported [29, 30], protein expression and spatial distribution within the tissue remain underexplored. Immunohistochemistry, used in relatively few studies, has yielded highly variable results and poor resolution quality [31–34]. Here, we harnessed the 3D-NaissI method to map ACE2 spatial expression in fresh myocardial tissues from adult mice, rats, and humans, using a knockout-validated anti-ACE2 antibody. Similar ACE2 expression patterns were observed across all examined cardiac tissue species (Fig. 7a), including specific expression in vascular cells confirmed by co-localization with Iso-B4 (Fig. 7b), as classically reported. Notably, ACE2 was detected across the entire plasma membrane of CMs, including the lateral surface, intercalated disks, and intracellular T-tubule invaginations, where it co-localized with caveolin-3 (Fig. 7c). Significant ACE2 expression was also noted in the CM nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 15a). The specificity of ACE2 expression in CMs was further confirmed by western-blot analysis using lysates from adult primary CMs purified from mouse hearts (Fig. 7d). In contrast, specific ACE2 expression in CMs was elusive using FFPE-tissues following supplier-recommended protocols, being detected only in vessels (IsoB4 co-localization; Supplementary Fig. 15b). The distinctive patterns of ACE2 expression in CMs, highlighted through the 3D-NAissI method, reveal potential mechanisms underlying SARS-CoV-2 infection and its impact on cardiac pathophysiology, particularly in COVID-19 cardiomyopathies. Additionally, the identification of ACE2 in the nuclei of CMs unveils a novel potential target for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, suggesting its involvement in dysregulation of nuclear signaling and contributing to the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in the heart. Accordingly, a recent study has revealed the presence of a nuclear localization signal sequence within the spike protein, indicating its putative potential for nucleus translocation [35].

Fig. 7.

Visualization of native ACE2 expression in cardiac tissue though the advanced 3D-NaissI Method. Representative images (3–5 independent experiments) of: a ACE2 immunostaining with fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and DAPI in fresh cardiac tissue (3D-NaissI) from 2-month-old male mice, rats or 19-year-old-man. Zoomed-in images (right panels) highlight ACE2 localization within cardiomyocytes. b ACE2-Isolectin B4 (IsoB4)-DAPI co-staining in fresh cardiac tissue from 2-month old male rats. Zoomed-in image (right panels) highlights ACE2 localization within vascular cells (Iso-B4 positive cells). c (Left panels) ACE2-Caveolin-3 (CAV3) co-staining in fresh cardiac tissue from 2-month old male mice. Zoomed-in images emphasize ACE2 positive co-localization with Caveolin-3 within cardiomyocytes (arrows, yellow dots on the merge). (Right panel) Corresponding quantification of Mander’s coefficient for co-localization between ACE2 and CAV3. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 3 mice (3–5 biopsies/mouse, 8–15 CMs/mouse). d Representative ACE2 expression quantified by western blot in 25 and 50 µg lysates from purified adult cardiomyocytes from 2-month-old male mouse

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2)

A contemporary challenge in cardiology revolves around comprehending the cardiac benefits associated with Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) therapeutic interventions through the examination of SGLT2 protein expression patterns in the heart. Recently, iSGLT2 have shown promise in reducing cardiovascular death and hospitalization in patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) [36], which accounts for over 50% of heart failure (HF) cases. Despite in vitro studies demonstrating direct cardiobenefits of SGLT2 inhibitors [37, 38], this finding contradicts the prevailing belief that SGLT2 expression is absent in both healthy and failing myocardium [39], despite conflicting results in the literature [40]. To address this discrepancy, our investigation focused on discerning the expression profile of SGTL2 in fresh myocardial biopsies obtained from adult mice, using the 3D-NaissI method. Our results clearly revealed a predominant intracellular expression with distinct punctate and lamellar labeling of SGLT2 within CMs and beneath the CM plasma membrane (Fig. 8a), with enhanced visualization in the Z-stack projection (Supplementary movie 1 and movie 2). This SGLT2 staining did not resemble T-Tubule labeling, and accordingly, it did not co-localize with caveolin-3 (Supplementary Fig. 16a). The labeling, especially in the Z-stack projection, reminisces the expression in the sarcoplasmic reticulum surrounding the myofibrils. Consistently, co-localization of SGLT2 with sarcoplasmic protein Calsequestrin (CASQ, Fig. 8b and Supplementary Fig. 16b) was observed, providing evidence for specific SGTL2 expression within the sarcoplasmic reticulum of the CM. In contrast, we failed to detect SGTL2 in FFPE-tissue following supplier-recommended protocol (Supplementary Fig. 16c). The specificity of SGLT2 labelling within CMs was validated by using a distinct SGLT2 antibody targeting the extra-transmembrane part of the protein (Supplementary Fig. 17a, Supplementary movie 3 and 4). The Mander’s correlation coefficient for SGLT2 and calsequestrin co-localization was comparable to that obtained for two well-known sarcoplasmic reticulum proteins, junctophilin 2 and phospholamban (Supplementary Fig. 17b). Supporting SGTL2 expression in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, empagliflozin was shown to enhance contractility and Ca2+ transients in isolated CMs [38]. The specific expression of SGTL2 in CMs was further confirmed by western-blot analysis of protein lysates from isolated adult CMs with or without SGLT2 immunoprecipitation and by using HEK293T kidney cells either endogenously expressing SGLT2 or overexpressing different levels of SGLT2 as positive control (Fig. 8c). The expected 73 kDa immature form of SGLT2 was detected endogenously in native HEK293T cells as expected for kigney epithelial cells where SGLT2 is highly expressed, and was further increased following transient expressing of SGLT2 (Exposition 1 and 2). Prolonged ECL exposition revealed a similar 73 kDa immature form in CM lysates, which was significantly enriched following SGLT2 immunoprecipitation (Exposition 1, 2, 3), suggesting a lower level of SGLT2 expression in CMs compared to HEK293T cells. Higher order SGLT2, likely SGLT2 oligomers, could also be detected in HEK293T cells or CMs.

Fig. 8.

Visualization of native SGTL2 expression in cardiac tissue though the advanced 3D-NaissI Method. Representative images (3–4 independent experiments) of: a SGTL2 immunostaining with fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and DAPI in fresh cardiac tissue (3D-NaissI) from 2-month-old male mice (3 independent experiments) or a 20-year-old woman. Zoomed-in images (right panels) highlight the punctuated and laminar SGTL2 staining within cardiomyocytes and beneath the plasma membrane (WGA-positive). b SGTL2-Calsequestrin (CASQ)-WGA-DAPI co-staining in fresh cardiac tissue from 2-month-old male mice. Zoomed-in image (right panels) emphasizes SGTL2 positive co-localization with Calsequestrin (yellow dots, arrows) within cardiomyocytes. c Representative SGTL2 expression quantified by western blot in lysates from purified adult cardiomyocytes of 2-month-old male mouse, with or without SGLT2 immunoprecipitation. Untransfected HEK293T cells, which endogenously express SGLT2 (immature form ~ 73 kDa and higher-order oligomers), or HEK293T cells transiently overexpressing different levels of SGLT2, were used as positive controls, as indicated

The identified specific expression of SGLT2 in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of CMs may have implications for the regulation of Ca2+ uptake to this compartment during diastole. This novel finding offers a compelling and alternative explanation for the observed therapeutic benefits of iSGLT2 in HFpEF patients, which may arise from the endogenous expression of SGLT2 in CMs rather than in non-cardiac tissues.

Junctophilin 2 (JPH2)-Ryanodine receptor (Ryr)

In addition to unraveling the expression of elusive cardiac proteins, the 3D-NaissI method facilitates the assessment of native expression/organization of known proteins within the natural context of cardiac tissue. It proves instrumental in investigating the native organization of components integral to excitation–contraction coupling (E-C coupling) within cardiac tissues, a domain predominantly explored in isolated CMs [41]. Unlike isolated CMs in culture, CMs within the tissue experience longitudinal mechanical constraints at the intercalated disc junctions and lateral constraints through interactions with the extracellular matrix and surface crests neighbored CMs. Both of this factors may influence the expression and spatial organization of proteins involved in the regulation of the E-C coupling. We applied the 3D-NaissI method to visualize JPH2 in fresh cardiac biopsies, a crucial structural protein forming 'dyads' that link the sarcoplasmic reticulum to the T-tubule membrane, in conjunction with the Ryr located on the sarcoplasmic reticulum. These proteins play pivotal roles in E-C coupling and are prone to spatial disorganization in HF [42]. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 18a, the expression of JHP2 in fresh myocardial samples from mice and humans aligns with the expected species differences in T-tubule organization, with smaller species exhibiting more intricate arrangements compared to larger mammals [42]. Consistent with the reduction of T-tubules observed during aging [43], JHP2 exhibited reduced expression and spatial organization in older patients compared to younger individuals (Supplementary Fig. 18b). The application of Airyscan technology allowed for the acquisition of JHP2 and Ryr expression patterns with exceptional resolution (Supplementary Fig. 18c and Supplementary Movie 5). In the future, the 3D-NaissI method holds promise for enhancing the analysis of E-C coupling component disorganization within a tissue context across diverse cardiac pathologies.

3D-NaissI reveals pericyte-rings structures encircling cardiomyocytes

The 3D-NaissI method provides only a small window of tissue visibility compared to the observation of the entire heart, yet excels in revealing intricate 3D architecture within specific cardiac compartments. The 3D reconstruction of the left ventricle myocardium stained with fluorescent-WGA unveiled previously undocumented ring-shaped structures surrounding α-actinin positive-CMs along their longitudinal axis in the adult mouse heart, a pattern conserved in rats and humans (Fig. 9a, b and Supplementary Fig. 19a). These structures, found throughout the myocardium, endocardium, and epicardium (Supplementary Fig. 20a), were compromised following PFA-biopsy fixation (Supplementary Fig. 21a). Close examination of WGA-staining revealed that the ring structures emanate from the cytoplasmic extensions of specific cells lying on the endothelial cell prolongations at the lateral surface of CMs, as indicated by nuclear staining in this location (Supplementary Fig. 21b). These structures exhibited 100% IsoB4 immunoreactivity (Fig. 9c and Supplementary Fig. 19b and 20b), suggesting a vascular origin. Drawing parallels with ring-like structures formed by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in the microvasculature [44], we hypothesized that pericytes, with their remarkable extension and connectivity potential [45], might mimic, on the microcirculation side and around the CM myofiber, the spatial organization of VSMCs. Supporting this hypothesis, the ring structures tested positive for the NG2 pericyte marker (Fig. 9d and Supplementary Fig. 19c), and exhibited 100% positivity for laminin 2 (Fig. 9e), suggesting that cardiac pericytes play a crucial role in the production of the CM basement membrane, a function recently demonstrated in other tissues [46, 47]. Accordingly, a distinct spatial arrangement of laminin-2 receptors, α-dystroglycan (Fig. 9f) and β1 integrin (Supplementary Fig. 21c), was observed along the laminin 2 positive ring structures on the CM surface. These ring-like structures could be better visualized in 3D representation (Supplementary movie 6 and 7). This reveals a novel spatial organization of pericytes in cardiac tissue [48], forming 3D-ring structures encompassing the rod-shaped CMs. This unique organization challenges the conventional understanding of ring structures formed by VSMCs around macrovasculature or pericytes around microvasculature [44]. The substantial coverage of CM lateral surfaces by pericytes, as revealed in this study, underscores a new pivotal role of pericytes in CM function.

Fig. 9.

Unveiling a novel 3D architectural structure in fresh cardiac tissue through advanced 3D-NaissI imaging. Representative images three-dimensional confocal imaging (3–5 independent experiments) of: a Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-DAPI-stained fresh cardiac biopsies from 2-month-old male mice, rat or a 26-year-old-man, revealing unidentified WGA-positive tube-like structures. These structures intricately surround cardiomyocytes along their longitudinal axis, as depicted by α-actinin positive staining (b). These novel 3D-structures are: c Isolectin B4 (IsoB4)-positive, d Neural/glial antigen 2 (NG2)-positive, e Laminin-2-positive and f meticulously organized along the α-dystroglycan positive-staining at the surface of cardiomyocytes. g Schematic illustrating a novel model of pericyte architecture in the cardiac tissue

Applicability of 3D-NaissIacross diverse tissues

While optimized for imaging native cardiac tissue, the 3D-NaissI method's applicability extends to challenging tissues such as the lipid-enriched brain, solid-cohesive skin, spongy air-filled lung tissue, and the gut. The method was applied directly to 1 mm3 fresh biopsies extracted from the mouse cortex, human skin, mouse lung, or mouse gut, successfully enabling imaging of all these tissues (Supplementary Fig. 22).

Discussion

This study introduces the 3D-NaissI method as an innovative and robust approach for imaging fresh native cardiac tissue biopsies, offering distinct advantages over traditional histological techniques. Our findings underscore the method's exceptional ability to preserve tissue integrity in hypothermic conditions, thus establishing a reliable platform for short-term imaging studies. By preserving tissue integrity, the 3D-NaissI method enables detailed imaging of cellular and molecular architecture, facilitating a comprehensive examination of native cardiac protein expression. Several pivotal insights have emerged from our results, underscoring the far-reaching implications of the 3D-NaissI method for advancing cardiac research.

In contrast to conventional tissue techniques, such as light and electron microscopy, which typically involve the use of chemical cross-linking agents to preserve tissue integrity, the 3D-NaissI method is entirely fixative-free. This approach relies on the use of fresh tissue biopsies throughout the entire process of fluorescent immunostaining and confocal imaging, successfully circumventing major artifacts associated with chemical fixation:

-

i.

The 3D-NaissI method facilitates the preservation of antibody epitopes, mitigating issues like epitope masking, conformational changes in proteins, disruption of protein–protein interactions, even protein aggregation artifacts. As a result, the 3D-NaissI method enables the successful use of a wide range of commercially available antibodies described for immunofluorescence, which stands in contrast to classical immunohistological techniques that often require unmasking strategies or prove ineffective with many antibodies.

-

ii.

The 3D-NaissI method significantly reduces autofluorescent background signals and nonspecific antibody binding. This reduction contributes to a high signal-to-noise ratio, enabling the detection of low levels of protein expression without the need for additional blocking steps to minimize nonspecific signals.

-

iii.

The 3D-NaissI method excels in preserving the native cellular and molecular spatial organization. Hence, our study delves into the intricate architecture of cardiac tissue, uncovering previously undocumented ring-like structures formed by pericytes around CMs. This novel 3D organization emphasizes the significance of pericytes in cardiac tissue and challenges conventional notions of their spatial arrangement, which has been exclusively described relative to the vascular cells until now This intricate structure, lost after tissue fixation, underscores the method's superiority. Unlike fixed biopsies, fresh samples retain the inter-lateral space between CMs, reflecting natural tissue cohesion. Fixation-induced shrinkage alters intercellular space, potentially masking epitopes. Notably, 3D-NaissI minimizes cell size changes seen in fixed conditions, preventing significant modifications to biomolecule organization.

Challenging prior assumptions, these findings underscore the importance of studying protein expression in the native tissue context. Applying 3D-NaissI to analyze cardiac proteins like Cx43, ACE2, and SGLT2 reveals novel insights into their distribution. Particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, mapping ACE2 expression sheds light on cardiac complications related to infectious diseases. The unexpected lateralization of Cx43, as revealed in native healthy cardiac tissues, has challenged our understanding of cardiac pathophysiology. Contrary to previous assumptions, this discovery points more towards concerns about tissue decompaction (increased inter-lateral space between CMs) than a pathological localization of Cx43 on the lateral face of the CM. The presence of Cx43 at the CM lateral membrane prompts questions about its specific role in this location, challenging conventional wisdom regarding its typical presence at the intercalated disc and its established role in rhythmology and arrhythmogenesis [19].

In summary, the fixative-free nature of the 3D-NaissI method offers significant advantages over traditional techniques. It not only effectively preserves tissue integrity and spatial organization but also mitigates artifacts, thus enhancing the overall quality of imaging and analysis for a more comprehensive understanding of native tissue characteristics.

Beyond fixative omission, the 3D-NaissI method offers a significant advantage by obviating delipidation-based permeabilization, a conventional hurdle in intracellular antibody penetration. Preserving cell membrane integrity unlocks the visualization of native membrane proteins, a feat conventionally more challenging. Moreover, this technique is characterized by its simplicity, swift application, compatibility with standard confocal microscopes, and cost-effectiveness. However, limitations include reliance on small tissue samples and restricted fields of view, positioning the 3D-NaissI method as a complementary tool that synergizes with other classical tissue imaging techniques for affirming native protein expression in specific organ sub-compartments.

The use of fresh cardiac tissue in cardiology is not new, with the emergence of living myocardial slices (LMS) in recent years, albeit presenting technical challenges [49]. Unlike isolated cell preparations, LMS serves as a physiologically relevant ex vivo organotypic model, preserving the native intercellular network. However, current developments have predominantly focused on functional studies, concentrating on mechanical and electrical investigations [50]. Although maintaining LMS functionality for extended periods involves specific ex vivo culture procedures [14, 49, 51], such as the use of thick cardiac slices (~ 300 µm) and environmental factors like oxygenation, ionic culture medium, and electromechanical stimulation, its applicability for microscopic imaging is constrained. Typically, fixatives are necessary, compromising the tissue's native properties. In this context, the 3D-NaissI method emerges as a complementary approach to LMS, facilitating the short-term utilization of fresh cardiac biopsies specifically for imaging purposes.

In conclusion, the 3D-NaissI method stands out as a powerful tool for short-term imaging of fresh native cardiac tissue biopsies, offering relative high preservation of tissue integrity, viability, and native protein expression. Its versatility is evident not only in cardiac research but also in imaging various tissues, showcasing its potential applications. The method's ability to provide detailed insights into the 3D organization of cellular components and protein expression patterns makes it a valuable addition to the toolbox of researchers investigating biological systems in their native state. Hence, the 3D-NaissI method holds great promise for both research and clinical applications. Beyond its potential to complement existing databases like the Human Protein Atlas (www.proteinatlas.org), the method distinguishes itself with clinical diagnostic utility. For instance, the use of fresh cardiac biopsies obtained during surgeries could yield valuable insights into cellular and molecular aspects of cardiac diseases, extending its applicability to other medical fields such as oncology. Integrating this methodology into surgical procedures might not only enhance our understanding of diseases but also facilitate translational research, bridging the gap between basic research and clinical practice. In line with the clinical translational aspect, the ability to image fresh tissue biopsies derived from human autopsy samples adds a significant dimension to the 3D-NaissI method. This provides access to a larger tissue collection, including control tissues that are often scarce in surgical contexts. However, it is essential to note that the imaging results of autopsy biopsies are contingent upon the clinical context of the patient. Overall, the 3D-NaissI method emerges as a versatile tool with profound implications for advancing biomedical knowledge and improving patient care.

Methods

Further material and methods details used in his manuscript are available on the Supplementary material online.

Ethical statement

Procedures involving human cardiac samples were conducted at the Department of Forensic Medicine, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Toulouse (University of Toulouse, France), adhering strictly to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, these procedures received approval in accordance with French legislation from the Agence de Biomédecine under registration number PFS21-015, with explicit consent obtained from the relatives, signifying their non-objection to the sampling process.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the European directive for the protection of animals used for scientific purpose and were approved of the French CEEA-122 ethical committee (CEEA 122 2015–28).

Animal models and euthanasia

All studies were performed on 2-month old male C57BL/6J OlaHsd mice, Spague Dawley rats (purchased from Envigo, Huntingdon, United-Kingdom). Hearts from male X-linked muscular dystrophy mice (C57BL/10ScSnDmdmdx/J) designed as MDX, were obtained from Dr O. Cazorla, (PhyMedExp, Université de Montpellier, France) and from a colony maintained in their local animal facility (Plateau Central d’Elevage et d’Archivage, Montpellier, France). Two-month old male C57BL/6J OlaHsd mice purchased from Envigo were designed as control for the MDX mice. Cardiomyocyte-specific efnb1 knock-out mice (KO) and their WT counterparts have already been described [25], and all studies using these mice were performed on male and age-matched littermate mice.

All animals were maintained in the animal facility at the UMS06-Centre régional d'exploration fonctionnelle et de resources expérimentales-CREFRE (Toulouse, France) under specific-pathogen free (SPF) conditions and following institutional animal use and care guidelines. Animals were housed conventionally in controlled humidity and temperature, operating on12 h of light and dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 50 mg/kg Dolethal (Vetoquinol, Lure, France) in the presence of 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine and euthanasia was performed after chest opening by promptly excising the beating heart to prepare fresh cardiac biopsies.

Preparation of fresh cardiac biopsies

For mice and rats, immediately after removal, the beating heart was transferred in cold PBS and gently pressed to squeeze blood out. Then, a cross-sectional heart slice (~ 3 mm thick) was briefly washed in 3 successive cold PBS baths. The left ventricle was excised, the endocardium and epicardium were excised and the remaining myocardium was then cautiously sliced (~1 mm3 biopsies) on a glass slide on ice using a very fine and sharp scalpel. Similar procedure was performed for the human cardiac biopsies, except that only a small portion of the left ventricular myocardium was harvested from autopsy hearts.

Fluorescent staining of fresh cardiac biopsies

Tissue integrity study. Fresh biopsies were incubated in 500 µL PBS, HBSS or cardioplegic solution in 24-well plates at 4 °C, 37 °C or room temperature under constant rotational agitation for 2 days in the dark in the presence of Alexa Fluor-WGA, DAPI and Alexa Fluor-IsoB4. For the kinetics study, fresh biopsies were incubated in cold PBS for 0, 2, 4, 7 or 10 days and stained with Alexa Fluor-WGA and DAPI for 4 h before confocal image acquisition.

Tissue viability study. Fresh biopsies were incubated in 500 µL PBS, HBSS or cardioplegic solution 24-well plates at 4 °C, 37 °C or room temperature under constant rotational agitation for 2 days in the dark and in the presence of Alexa Fluo-WGA, DAPI and MitoTracher®Red CMXRos. For the kinetics study, fresh biopsies were prepared on Day 0 and subjected to 2 days of staining in PBS at 4 °C in the dark with MitoTracher®Red CMXRos, Alexa Fluor™-WGA and DAPI before confocal imaging at day 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Alternatively, staining was performed in the presence of Di-8-ANEPPS and DAPI for 4 h before confocal imaging at day 2, 4, 7 and 10 (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Tissue immunostaining. Fresh biopsies were incubated in 500 µL PBS in 24-well plates at 4 °C under constant rotational agitation in the dark with the primary antibody for 2 days, followed by a rapid washing step with cold PBS, incubation with the secondary antibody for 2 more days at 4 °C under constant rotational agitation in the dark, and finally a prompt was with cold PBS before confocal imaging.

2D quantification of cardiomyocyte area and inter-lateral space

Quantification of cardiomyocyte (CM) area was performed on confocal images of paraffin-embedded heart sections (transverse sections) or fresh cardiac biopsies, both stained with Alexa FluorTM488-WGA, enabling precise delineation of the CM surface. The CM areas were quantitatively assessed using Fiji (Image J, NIH) by manually tracing cellular contours from confocal microscope images (Zeiss LSM 900 confocal microscope, Carl Zeiss) captured at a magnification of 63X. Approximately 5–10 images per mouse were acquired to ensure appropriate statistical analysis. On the same 2D confocal images, inter-lateral space between CMs was quantified by subtracting the total CM area from the entire image area. To account for potential variations in CM area associated with cardiac phenotype, the inter-lateral space was finally quantified relative to the CM area and thus expressed as a ratio.

Confocal microscopy and image acquisition/analysis

Fresh biopsies were mounted on ice on concave microscope glass slides (Hecht Karl™, 42,412,010) filled with 80 µL cold PBS and covered with coverslips (Menzel-Gläser, MENZCB00190RA120) fixed with a silicon seal and immediately imaged at the temperature of the confocal microscope room set at 19 °C.

Image acquisition was conducted on a ZEISS LSM 900 Axio Observer.Z1/7 with Airyscan 2 inverted confocal microscope using a X63 1.4 NA oil objective at a maximum resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels. Three-dimensional stacks were acquired with a 1 µm z-spacing and x and y pixel size of 0.099 µm. The images presented in this paper represent the most representative selection from multiple acquisitions. Image visualization was performed using Zen Blue (Carl Zeiss, Germany) software. Three-D images was carried out using Zen Blue and Imaris (Bitplane, Belfast, UK). For comparative studies, similar microscope settings have always been used with the same primary antibody; however, depending on the primary antibody, different settings may have been applied. Filter ranges: DAPI 405: 400–510 nm/AF 488: 510–550 nm/AF 555: 550–700 nm/AF 568: 545–620 nm/AF 594: 595–645 nm/AF 633: 645–700 nm/AF 647: 656–700 nm. Gain: DAPI 405: 500–600 V/AF 488: 550–700 V/AF 555: 600 V/AF 568: 550–700 V/AF 594: 600–700 V/AF 633: 600–700 V/AF 647: 600–700 V. Pixel Dwell time: 0.52 µsec.

For quantification of fluorescence co-localizations, confocal images were analyzed using FIJI software. A region of interest (ROI) corresponding to the cardiomyocyte cytoplasm was manually selected. Automatic segmentation of the CASQ and SGLT2 signals within this ROI was performed using the YEN (or Moments) auto-thresholding method [52] for CRSQ and SGLT2 signal. The resulting masks were then filtered with a median filter (radius = 1 pixel) to reduce noise. Mander’s overlap coefficient (MOC) [53] for SGLT2 was calculated from the segmented masks along with the fraction of CASQ within the ROI.

Quantification of cAMP production in fresh cardiac biopsies

Quantification of intracellular cAMP was performed using the HTRF cAMP competitive immunoassay (cAMP Gi kit, 62AM9PEB, Revvity) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fresh mouse cardiac biopsies (1 biopsy ~ 1–3 mg/well) were distributed in a 96-well white microplate (OptiPlate-96; PerkinElmer) and incubated or not (basal) with isoproterenol (10 µM) or carvedilol (10 µM) alone or in combination for 30 min at room temperature and in the presence of 0.5 mM IBMX to prevent phosphodiesterase-mediated cAMP degradation. After the addition of cryptate-labeled cAMP (donor) and anti-cAMP-d2 (acceptor) for 1 h, the specific FRET signals were calculated by the fluorescence ratio of the acceptor and donor emission signal (665/620 nm) collected using a modified Infinite F500 (Tecan Group Ltd). Conversion of the HTRF ratio of each sample into cAMP concentrations was performed on the basis of a standard curve to determine the linear dynamic range of the assay.

Data analysis-statistics-reproducibility

The n number for each experiment and analysis is stated in each figure legend.

An unpaired Student t-test for parametric variables was used to compare two groups. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test was used for multiple group comparisons (> 2 groups). The level of significance was assigned to statistics in accordance with their p values: p ≤ 0.05 *; p ≤ 0.01 **; p ≤ 0.001 ***; p ≤ 0.0001 ****). All graphs and statistics were generated using v9.2.0 (GraphPad Inc, San Diego, California).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank support from Remy Flores-Flores at the PHI-histology imaging platform (I2MC-Toulouse, France) and the We-Met functional biochemistry platform from TRI Genotoul network facilities. We also thank Dr Olivier Cazorla from PhyMedExp (Université de Montpellier, France) for providing the mdx mice. Dr Corinne Lorenzo is acknowledged for helpful discussions on biopsy imaging, and we thank everyone from the ANR-18-CE06-0027-04 consortium for all their support in this project.

Author contributions

C.G. conceived the idea and assisted N.P in realizing all the imaging experiments. N.P. performed all the small tissue biopsies required for the 3D-NaissI method, as well as the entire processing of the biopsies up to image acquisition. C.G.F. provided us with the human biopsies. C.G.F. and J.M.S. handled ethical authorization at the “Agence de Biomédecine” for the use of human biopsies obtained from autopsies for scientific purposes. V.P. conducted the functional studies (cAMP production) of the biopsies used in the NaissI method. A. W. conducted and quantified all Western blot experiments, as well as some staining experiments using the NaissI method. C.G wrote the paper with the help of C.K., J.M.S and CGF. All authors contributed to proofreading.

Funding

This study was supported by the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche” (ANR-18-CE06-0027-04 to CG).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

Procedures involving human cardiac samples were conducted at the Department of Forensic Medicine, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Toulouse (University of Toulouse, France), adhering strictly to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, these procedures received approval in accordance with French legislation from the Agence de Biomédecine under registration number PFS21-015, with explicit consent obtained from the relatives, signifying their non-objection to the sampling process.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the European directive for the protection of animals used for scientific purpose and were approved of the French CEEA-122 ethical committee (CEEA 122 2015-28).

Consent for publication

All the authors have approved and agreed to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chong JJ, Yang X, Don CW, Minami E, Liu YW, Weyers JJ et al (2014) Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature 510:273–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabisonia K, Prosdocimo G, Aquaro GD, Carlucci L, Zentilin L, Secco I et al (2019) MicroRNA therapy stimulates uncontrolled cardiac repair after myocardial infarction in pigs. Nature 569:418–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiba Y, Gomibuchi T, Seto T, Wada Y, Ichimura H, Tanaka Y et al (2016) Allogeneic transplantation of iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerates primate hearts. Nature 538:388–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Q, Garrett A, Bose S, Blocker S, Rios AC, Clevers H et al (2021) The frontier of live tissue imaging across space and time. Cell Stem Cell 28:603–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian T, Yang Z, Li X (2021) Tissue clearing technique: recent progress and biomedical applications. J Anat 238:489–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolesova H, Olejnickova V, Kvasilova A, Gregorovicova M, Sedmera D (2021) Tissue clearing and imaging methods for cardiovascular development. iScience 24:102387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodyer WR, Beyersdorf BM, Duan L, van den Berg NS, Mantri S, Galdos FX et al (2022) In vivo visualization and molecular targeting of the cardiac conduction system. J Clin Invest 132:e156995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Q, Lakatos E, Bakir IA, Curtius K, Graham TA, Mustonen V (2022) The mutational signatures of formalin fixation on the human genome. Nat Commun 13:4487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirizzi G, Jelke F, Pilot M, Klein K, Klamminger GG, Gerardy JJ et al (2024) Impact of formalin- and cryofixation on Raman spectra of human tissues and strategies for tumor bank inclusion. Molecules 29:1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paavilainen L, Edvinsson A, Asplund A, Hober S, Kampf C, Ponten F et al (2010) The impact of tissue fixatives on morphology and antibody-based protein profiling in tissues and cells. J Histochem Cytochem 58:237–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira PM, Albrecht D, Culley S, Jacobs C, Marsh M, Mercer J et al (2019) Fix your membrane receptor imaging: actin cytoskeleton and CD4 membrane organization disruption by chemical fixation. Front Immunol 10:675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnell U, Dijk F, Sjollema KA, Giepmans BN (2012) Immunolabeling artifacts and the need for live-cell imaging. Nat Methods 9:152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson SA, Scigliano M, Bardi I, Ascione R, Terracciano CM, Perbellini F (2017) Preparation of viable adult ventricular myocardial slices from large and small mammals. Nat Protoc 12:2623–2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer C, Milting H, Fein E, Reiser E, Lu K, Seidel T et al (2019) Long-term functional and structural preservation of precision-cut human myocardium under continuous electromechanical stimulation in vitro. Nat Commun 10:117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ou Q, Jacobson Z, Abouleisa RRE, Tang XL, Hindi SM, Kumar A et al (2019) Physiological biomimetic culture system for pig and human heart slices. Circ Res 125:628–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guilbeau-Frugier C, Cauquil M, Karsenty C, Lairez O, Dambrin C, Payre B et al (2019) Structural evidence for a new elaborate 3D-organization of the cardiomyocyte lateral membrane in adult mammalian cardiac tissues. Cardiovasc Res 115:1078–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidel T, Edelmann JC, Sachse FB (2016) Analyzing remodeling of cardiac tissue: a comprehensive approach based on confocal microscopy and 3D reconstructions. Ann Biomed Eng 44:1436–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy HS (2012) The molecular mechanisms of gap junction remodeling. Heart Rhythm 9:1331–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontes MS, van Veen TA, de Bakker JM, van Rijen HV (2012) Functional consequences of abnormal Cx43 expression in the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818:2020–2029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesketh GG, Shah MH, Halperin VL, Cooke CA, Akar FG, Yen TE et al (2010) Ultrastructure and regulation of lateralized connexin43 in the failing heart. Circ Res 106:1153–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevenson S, Rothery S, Cullen MJ, Severs NJ (1997) Dystrophin is not a specific component of the cardiac costamere. Circ Res 80:269–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez JP, Ramachandran J, Xie LH, Contreras JE, Fraidenraich D (2015) Selective connexin43 inhibition prevents isoproterenol-induced arrhythmias and lethality in muscular dystrophy mice. Sci Rep 5:13490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Himelman E, Lillo MA, Nouet J, Gonzalez JP, Zhao Q, Xie LH et al (2020) Prevention of connexin-43 remodeling protects against Duchenne muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 130:1713–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pina R, Santos-Diaz AI, Orta-Salazar E, Aguilar-Vazquez AR, Mantellero CA, Acosta-Galeana I et al (2022) Ten approaches that improve immunostaining: a review of the latest advances for the optimization of immunofluorescence. Int J Mol Sci 23:1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genet G, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Honton B, Dague E, Schneider MD, Coatrieux C et al (2012) Ephrin-B1 is a novel specific component of the lateral membrane of the cardiomyocyte and is essential for the stability of cardiac tissue architecture cohesion. Circ Res 110:688–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karsenty C, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Genet G, Seguelas MH, Alzieu P, Cazorla O et al (2023) Ephrin-B1 regulates the adult diastolic function through a late postnatal maturation of cardiomyocyte surface crests. Elife 12:80904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanford JL, Edwards JD, Mays TA, Gong B, Merriam AP, Rafael-Fortney JA (2005) Claudin-5 localizes to the lateral membranes of cardiomyocytes and is altered in utrophin/dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38:323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z (2022) Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med 28:583–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shao X, Zhang X, Zhang R, Zhu R, Hou X, Yi W et al (2022) The atlas of ACE2 expression in fetal and adult human hearts reveals the potential mechanism of heart-injured patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 322:C723–C738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tucker NR, Chaffin M, Bedi KC Jr, Papangeli I, Akkad AD, Arduini A et al (2020) Myocyte-specific upregulation of ACE2 in cardiovascular disease: implications for SARS-CoV-2-mediated myocarditis. Circulation 142:708–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bargehr J, Rericha P, Petchey A, Colzani M, Moule G, Malgapo MC et al (2021) Cardiovascular ACE2 receptor expression in patients undergoing heart transplantation. ESC Heart Fail 8:4119–4129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brumback BD, Dmytrenko O, Robinson AN, Bailey AL, Ma P, Liu J et al (2023) Human cardiac pericytes are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. JACC Basic Transl Sci 8:109–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hikmet F, Mear L, Edvinsson A, Micke P, Uhlen M, Lindskog C (2020) The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol Syst Biol 16:e9610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson FA, Mihealsick RP, Wagener BM, Hanna P, Poston MD, Efimov IR et al (2020) Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and pericytes in cardiac complications of COVID-19 infection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 319:H1059–H1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sattar S, Kabat J, Jerome K, Feldmann F, Bailey K, Mehedi M (2023) Nuclear translocation of spike mRNA and protein is a novel feature of SARS-CoV-2. Front Microbiol 14:1073789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Bohm M et al (2021) Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 385:1451–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen S, Coronel R, Hollmann MW, Weber NC, Zuurbier CJ (2022) Direct cardiac effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21:45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, Lu Q, Qiu Y, do Carmo JM, Wang Z, da Silva AA, et al (2021) Direct cardiac actions of the sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin improve myocardial oxidative phosphorylation and attenuate pressure-overload heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 10:018298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Franco A, Cantini G, Tani A, Coppini R, Zecchi-Orlandini S, Raimondi L et al (2017) Sodium-dependent glucose transporters (SGLT) in human ischemic heart: a new potential pharmacological target. Int J Cardiol 243:86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marfella R, Scisciola L, D’Onofrio N, Maiello C, Trotta MC, Sardu C et al (2022) Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) expression in diabetic and non-diabetic failing human cardiomyocytes. Pharmacol Res 184:106448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner E, Lauterbach MA, Kohl T, Westphal V, Williams GS, Steinbrecher JH et al (2012) Stimulated emission depletion live-cell super-resolution imaging shows proliferative remodeling of T-tubule membrane structures after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 111:402–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dibb KM, Louch WE, Trafford AW (2022) Cardiac transverse tubules in physiology and heart failure. Annu Rev Physiol 84:229–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyu Y, Verma VK, Lee Y, Taleb I, Badolia R, Shankar TS et al (2021) Remodeling of t-system and proteins underlying excitation-contraction coupling in aging versus failing human heart. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 7:16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corliss BA, Mathews C, Doty R, Rohde G, Peirce SM (2019) Methods to label, image, and analyze the complex structural architectures of microvascular networks. Microcirculation 26:e12520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray IR, Baily JE, Chen WCW, Dar A, Gonzalez ZN, Jensen AR et al (2017) Skeletal and cardiac muscle pericytes: functions and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Ther 171:65–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM (2013) Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med 19:1584–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakhneny L, Epshtein A, Landsman L (2021) Pericytes contribute to the islet basement membranes to promote beta-cell gene expression. Sci Rep 11:2378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longden TA, Zhao G, Hariharan A, Lederer WJ (2023) Pericytes and the control of blood flow in brain and heart. Annu Rev Physiol 85:137–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perbellini F, Thum T (2020) Living myocardial slices: a novel multicellular model for cardiac translational research. Eur Heart J 41:2405–2408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pitoulis FG, Watson SA, Perbellini F, Terracciano CM (2020) Myocardial slices come to age: an intermediate complexity in vitro cardiac model for translational research. Cardiovasc Res 116:1275–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson SA, Duff J, Bardi I, Zabielska M, Atanur SS, Jabbour RJ et al (2019) Biomimetic electromechanical stimulation to maintain adult myocardial slices in vitro. Nat Commun 10:2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yen JC, Chang FJ, Chang S (1995) A new criterion for automatic multilevel thresholding. IEEE Trans Image Process 4:370–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manders EM, Stap J, Brakenhoff GJ, van Driel R, Aten JA (1992) Dynamics of three-dimensional replication patterns during the S-phase, analysed by double labelling of DNA and confocal microscopy. J Cell Sci 103(Pt 3):857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.