Abstract

Btn2p, a novel coiled-coil protein, is up-regulated in btn1Δ yeast strains, and this up-regulation is thought to contribute to maintaining a stable vacuolar pH in btn1Δ strains (D. A. Pearce, T. Ferea, S. A. Nosel, B. Das, and F. Sherman, Nat. Genet. 22:55-58, 1999). We now report that Btn2p interacts biochemically and functionally with Rsg1p, a down-regulator of the Can1p arginine and lysine permease. Rsg1p localizes to a distinct structure toward the cell periphery, and strains lacking Btn2p (btn2Δ strains) fail to correctly localize Rsg1p. btn2Δ strains, like rsg1Δ strains, are sensitive for growth in the presence of the arginine analog canavanine. Furthermore, btn2Δ strains, like rsg1Δ strains, demonstrate an elevated rate of uptake of [14C]arginine, which leads to increased intracellular levels of arginine. Overexpression of BTN2 results in a decreased rate of arginine uptake. Collectively, these results indicate that altered levels of Btn2p can modulate arginine uptake through localization of the Can1p-arginine permease regulatory protein, Rsg1p. Our original identification of Btn2p was that it is up-regulated in the btn1Δ strain which serves as a model for the lysosomal storage disorder Batten disease. Btn1p is a vacuolar/lysosomal membrane protein, and btn1Δ suppresses both the canavanine sensitivity and the elevated rate of uptake of arginine displayed by btn2Δ rsg1Δ strains. We conclude that Btn2p interacts with Rsg1p and modulates arginine uptake. Up-regulation of BTN2 expression in btn1Δ strains may facilitate either a direct or indirect effect on intracellular arginine levels.

Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, or Batten disease, is an autosomal recessive progressive neurodegenerative disease in children, with an incidence as high as one in 12,500 live births (1, 5). Diagnosis is often based on visual defects, behavioral changes, and seizures. Progression is characterized by a decline in mental abilities, increased severity of untreatable seizures, blindness, loss of motor skills, and premature death. The human CLN3 gene, positionally cloned in 1995, was shown to be responsible for Batten disease, with most individuals with the disease harboring a major deletion in the gene (8). A characteristic of Batten disease is the lysosomal storage or accumulation of lipopigments such as lipofuscin in all cell types. A predominant component of this storage material is proteolipid subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase (6, 12, 14, 15). However, despite knowledge of the genetic defect and evidence for Batten disease being a lysosomal storage disease, an understanding of the molecular basis for Batten disease remains elusive. Genes encoding predicted proteins with high sequence similarity to the human Cln3 protein have been identified in mice, dogs, rabbits, Caenorhabditis elegans, and yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We previously reported that the corresponding yeast gene, denoted BTN1, encodes a nonessential protein that is 39% identical and 59% similar to the human Cln3 protein (16). We further demonstrated that yeast strains lacking Btn1p were resistant to d-(−)-threo-2-amino-1-[p-nitrophenyl]-1,3-propanediol (ANP) and that this phenotype was complemented by expression of the human Cln3 protein, indicating that yeast Btn1p and the human Cln3 protein have some functional overlap (17). Furthermore, the degree of ANP resistance was correlated with point mutations identified in the human CLN3 gene that are associated with less-severe forms of Batten disease, further establishing the functional equivalence of Btn1p and the human Cln3 protein (15). The human Cln3 protein, like Btn1p, has been localized to the lysosome, denoted the vacuole in yeast (3, 7, 9, 10, 18).

Resistance of btn1Δ yeast strains to ANP was caused by an apparent decrease in the pH of growth media brought about by an elevated ability to acidify growth medium. This elevated rate of acidifying the growth medium was brought about by an increase in the activity of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase (18). Furthermore, it was proposed that the elevated activity of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase was most likely caused by a response to an imbalance in intracellular pH homeostasis within the cell, resulting from a decrease in the pH in the vacuoles of btn1Δ strains (18). Curiously, the elevated activity of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase and the decrease in vacuolar pH were evident only in early exponentially growing cells, apparently being normalized as the cells grew. DNA microarray analysis revealed that the expression of only two genes, HSP30 and BTN2, was increased as btn1Δ strains grew. The product of HSP30, as well as being a heat shock protein, acts as a down-regulator of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase (20), and therefore in btn1Δ strains this protein normalized the elevated plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity exhibited in early growth. BTN2 encodes a novel coiled-coil protein of unknown function, which was subsequently localized to the cytosol (2). Furthermore, deletion of BTN2, btn2Δ, results in an elevated activity of the vacuolar H+-ATPase, suggesting that up-regulation of BTN2 expression in btn1Δ strains may contribute either directly or indirectly to correction of the vacuolar pH defect in btn1Δ strains.

To further understand the function of Btn2p and the role of up-regulation of BTN2 expression in the yeast model for Batten disease, btn1Δ strains, we performed two-hybrid analysis with Btn2p. We report that Btn2p interacts with Rsg1p. Rsg1p has been shown to be a negative regulator of the uptake of arginine and lysine through the Can1p permease, and consequently rsg1Δ strains exhibit elevated uptake of arginine (22). We report that Rsg1p normally localizes to the cell periphery, close to the plasma membrane, and that, in btn2Δ strains, Rsg1p remains in the cytosol. As a result of the altered localization of Rsg1p in btn2Δ strains, btn2Δ strains are phenotypically similar to rsg1Δ strains with regard to sensitivity to arginine analog canavanine and to an increased rate of arginine uptake. We therefore conclude that Btn2p has a role in regulating arginine levels in the cell through modulation of arginine uptake. Interestingly, btn1Δ suppresses sensitivity to canavanine and elevated uptake of arginine in a btn2Δ rsg1Δ strain, the implication of which is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, plasmids, and media.

Yeast strains used in the course of this study are listed in Table 1. Strain B-11718 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and strains B-12388, B-13048, and B-14248 were obtained from Research Genetics. All other strains derived from these strains were previously reported strains and constructs (2, 17). For overexpression of BTN2, BTN2 was cloned with primers BTN2-BamHI (GGATCCATGTTTTCCATATTC) and BTN2-SalI (GTCGACTTATATCTCCTCAATAATAG) behind the GAL1 promoter in pAA1052, generating pDAP071. For canavanine sensitivity, cultures (10 units of optical density at 600 nm [OD600]/ml) were diluted (1:50, 1:75, or 1:150) in sterile water and 3 μl of each was spotted on plates lacking Arg but containing canavanine (60 μg/ml) and also containing YPD (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% glucose) as a growth control and were incubated at 30°C for 2 to 3 days. Growth comparisons on synthetic complete media were performed in the same way.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Genotype | Strain no. |

|---|---|

| MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-11718 |

| MATaleu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-7553 |

| MATα btn1Δ::KANMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-13048 |

| MATα btn2Δ::KANMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-12388 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-14248 |

| MATabtn1Δ::HIS3 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-10195 |

| MATabtn2Δ::URA3 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-12641 |

| MATarsg1Δ::KANMX leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-14249 |

| MATabtn1Δ::HIS3 btn2Δ::URA3 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-12642 |

| MATabtn1Δ::HIS3 rsg1Δ::KANMX leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-13051 |

| MATabtn2Δ::URA3 rsg1Δ::KANMX leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-13054 |

| MATabtn1Δ::HIS3 btn2Δ::URA3 rsg1Δ::KANMX leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3Δ trp1-289 | B-14250 |

| MATα btn1Δ::KANMX btn2Δ::URA3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-14251 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX btn1Δ::HIS3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-13052 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX btn2Δ::URA3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-13053 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX btn1Δ::HIS3 btn2Δ::URA3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-14252 |

| MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 lys2-801 trp1-901 cdc25-2 | CDC25H |

| MATaleu2Δ1 ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 lys2-801 trp1Δ63 | YPH499 |

| MATα btn2Δ::KANMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 + pAA1052 | B-14379 |

| MATα btn2Δ::KANMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 + pDAP071 | B-14380 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX btn2Δ::LEU2 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | B-14399 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX btn2Δ::LEU2 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 + pAA1052 | B-14400 |

| MATα rsg1Δ::KANMX btn2Δ::LEU2 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 + pDAP071 | B-14401 |

Two-hybrid studies.

The Stratagene Cytotrap system was utilized for two-hybrid screening of interacting partners for Btn2p. Essentially the manufacturer's instructions were followed. BTN2 was amplified with Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene) from yeast genomic DNA with primers BTN2Nco, TACACCATGGCCATGTTTTCCATATTC, and BTN2Not, GTATTGCGGCCGCTTATATCTCCTC. The resultant PCR product was cloned in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions into ZeroBlunt (Invitrogen) and subsequently digested with NcoI and NotI to liberate BTN2 to facilitate cloning into the NcoI and NotI sites of the pSOS bait plasmid. In-frame insertion of BTN2 was confirmed by sequencing. Expression of the human SOS (hSOS)-Btn2 protein was confirmed by Western analysis (not shown). A yeast cDNA library was constructed in the pMyr or trap plasmid. Total RNA was isolated from yeast cells, and mRNA was isolated with the Stratagene mRNA isolation kit in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The yeast cDNA library was prepared from this mRNA with the Stratagene Cytotrap XR library construction kit, again by following the manufacturer's instructions.

The hSOS-BTN2 bait and pMyr library constructs were cotransformed into yeast strain CDC25H (Table 1) by a slightly modified lithium acetate transformation procedure as described with the Cytotrap kit (Stratagene). Transformants were grown on synthetic complete media lacking leucine and uracil for 4 to 5 days at 25°C, replica plated onto synthetic complete media lacking leucine and uracil with galactose as the carbon source instead of glucose, and grown at 37°C. Colonies that grew on these media were picked and rescreened for their ability to grow at 37°C on the glucose and galactose media and were compared to the positive and negative controls provided by Stratagene.

Coimmunoprecipitation of Btn2p and Rsg1p.

BTN2 and RSG1 were cloned into pESC yeast epitope tagging vector pESC-TRP (Stratagene) by using BTN2Not1, GCGGCCGCATGTTTTCCATATTC, and BTN2Spe1, ACTAGTATCTCCTCAATAATAGAGTTT, for BTN2 and RSGApa1, GGGCCCATGGAATACGC, and RSGSal1, GTCGACCATTATAGAAC, for RSG1. BTN2 was cloned in frame in the NotI-SpeI sites of the vector so that its product contains the FLAG epitope at its C terminus. RSG1 was similarly cloned in frame in the ApaI-SalI sites of the same vector so that its product contains the c-myc epitope at its C terminus. The plasmids containing BTN2 adjacent to the FLAG coding sequence and RSG1 adjacent to the c-myc coding sequence were transformed into yeast strain YPH499 (Table 1). A single colony of the transformants was inoculated into 50 ml of synthetic galactose minimal medium to an OD600 of 0.2 and grown at 30°C for 16 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C in a Sorval SA600 rotor. The pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of coimmunoprecipitation (CIP) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1 tablet of mini-protease inhibitor [Boehringer-Mannheim] per 10 ml of buffer). An equal volume of 0.45-mm sterile glass beads was added, and the suspension was vortexed for 30 s with a 1-min interval on ice five or six times. The pellet was collected after centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. An anti-FLAG mouse monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was added at a dilution of 1:150, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 4°C with mild shaking. Fifty microliters of protein A-agarose (Sigma) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h and centrifuged at 850 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of CIP buffer on ice, and the suspension was centrifuged at 850 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resultant pellet was washed twice with 500 μl of cold CIP buffer, re-collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in 50 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer, and proteins were separated on an SDS-10% PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose by standard techniques. Tagged Rsg1p was visualized with an anti-c-myc mouse monoclonal antibody (diluted 1:1,000; Neomarkers) and subsequently with a horseradish peroxidase-tagged antimouse secondary antibody (diluted 1:3,000; Amersham) and finally stained with the ECLplus kit and developed in ECL film.

Localization of GFP-Btn2p and GFP-Rsg1p.

For localization studies of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-RSG1p in rsg1Δ and rsg1Δ btn2Δ strains, RSG1 was amplified with Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene) by using the following primers, which contain BamHI and EcoRI restriction recognition sequences: RSG1Bam, GGATCCATGGAATACGC, and RSG1Eco, GAATTCCATTATAGAAC. RSG1 was cloned in frame into pUG34 (N-fus-GFP) (U. Guldener and J. Hegemann, unpublished data). rsg1Δ and rsg1Δ btn2Δ cells were transformed with the construct by the standard lithium chloride technique. Transformants were grown on media lacking Met and His to an OD600 of 0.2 and observed by confocal microscopy (TCS SP laser scanning confocal microscope with an argon laser and a 100× lens with a numerical aperture of 1.3; Leica). Similarly, BTN2 was amplified with BTN2spe, GCTCATACTACTAGTATGTTTTCCATATTC, and BTN2Sal, CTAGACTGTCGACTATCTCCTCAATAATAG, and ligated into pUG23 (C-fus-GFP) (U. Gueldener and J. Hegemann, unpublished data). All plasmid constructions were in accordance with standard molecular biology procedures (21).

Arginine uptake.

The arginine uptake assay was performed as described by Urano et al. (22) with some minor modifications. Late-phase cultures (OD600, 6) grown at 30°C in YPD were collected and washed twice with synthetic minimal medium supplemented with 20 mg of histidine, 20 mg of uracil, and 20 mg of tryptophan/liter (SDHUW). Cells were resuspended in 7 ml of the same medium, and 1.2 ml of the suspension was used for uptake studies. The assay was initiated by the addition of 15 μl of [14C]arginine (348 mCi/mmol; AP-Biotech) and 12 μl of 10 mM nonradioactive arginine (Sigma). Then 200 μl was removed, immediately diluted 25-fold in SDHUW, and filtered. The filtered cells were washed twice and collected with a vacuum manifold on Whatman GF/C filters. Uptake was determined by measuring the radioactivity associated with dried filters in Ecoscint A liquid scintillation solution (National Diagnostics) by using a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter. Assay of uptake by cells overexpressing BTN2 was performed essentially as described above except that cells were grown in synthetic complete medium (B-11718, B13048, and B-12388) or synthetic complete medium lacking uracil (B-14379 and B-14380) and induced in galactose for 90 min at 30°C.

Extraction of yeast amino acids.

A standard procedure for extraction of total amino acids was used (13). In summary, cells at an OD600 of 1.6 were harvested, washed twice in distilled water, resuspended in AA buffer (2.5 mM potassium phosphate buffer [pH 6.0] containing 0.6 M sorbitol, 10 mM glucose and 0.2 M CuCl2) and incubated for 10 min at 30°C. This buffer permeabilizes the plasma membrane and causes leakage of cytosolic amino acids (13). The cell suspension was collected by filtration on membrane filters (0.45-μm pore size; Millipore) and washed four times with AA buffer lacking 0.2 M CuCl2. These filtrates were combined and represent the cytosolic fraction (13). Cells retained on the filter were resuspended in water and boiled for 15 min and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected as the vacuolar fraction.

Amino acid analysis.

Yeast cytosolic and vacuolar fraction supernatants were analyzed by the Hewlett-Packard Aminoquant system. Amino acids were derivatized in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions and separated on an HP column (5 μM; 200 by 2.1 mm).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Btn2p interacts with Rsg1p.

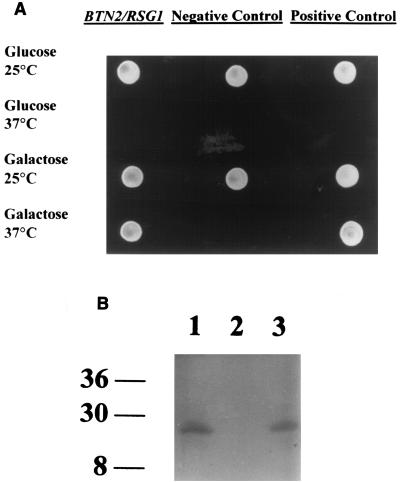

We utilized the Cytotrap (Stratagene) two-hybrid system. In summary, Btn2p is fused to hSOS, while a cDNA library is fused to a myristylation signal. To complement a cdc25 defect in the host transformation strain, SOS needs to be brought into close proximity with the plasma membrane, which occurs if Btn2p interacts with a protein at the plasma membrane by virtue of the myristylation signal. Figure 1A shows the growth characteristics of a single candidate transformant from this screening procedure, indicating a candidate protein for interaction with Btn2p that we subsequently identified through sequence analysis as Rsg1p. Essentially, positive candidates such as the RSG1 strain must grow at 37°C on galactose medium, which induces expression of the library of genes. As with all two-hybrid systems, biochemical or in vivo confirmation of interaction is required. Figure 1B shows Western analysis with a c-myc monoclonal antibody probing extracts from several yeast strains. Lane 1 shows whole-cell extract from the appropriate strain expressing both C-terminal c-myc-tagged Rsg1p and C-terminally FLAG-tagged Btn2p and shows the presence of c-myc-tagged Rsg1p. Lane 2 shows whole-cell extract from the appropriate strain expressing C-terminally FLAG-tagged Btn2p, which was immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. Lane 3 shows whole-cell extract from the appropriate strain expressing both C-terminally c-myc-tagged Rsg1p and C-terminally FLAG-tagged Btn2p, which was immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. As can be seen, immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody which binds to FLAG-tagged Btn2p brings with it c-myc-tagged Rsg1p, confirming that Btn2p and Rsg1p physically interact in vivo. It should be noted that these tags do not alter the function of Rsg1p or Btn2p as determined by the sensitivity of the growth of both btn2Δ and rsg1Δ strains to canavanine media, a phenotype that is discussed later.

FIG. 1.

Btn2p interacts with Rsg1p in two-hybrid screens and in vivo. (A) Growth of yeast strain CDC25H bearing pSOS-BTN2 and a candidate gene expressed from the pMYR cDNA library, identified as RSG1, at 37°C on galactose media but not at 37°C on glucose media. This isolate represents one positive candidate out of several thousand transformants that showed no growth at 37°C on galactose media and that therefore were deemed negative for a sequence that interacted with Btn2p. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of Btn2p and Rsg1p. Shown is Western analysis probing cell extracts derived from YPH499 expressing Btn2p-FLAG or Btn2p-FLAG and Rsg1p-c-myc with an anti-c-myc monoclonal antibody. Lane 1, cell extract of YPH499 expressing Btn2p-FLAG and Rsg1p-c-myc; lane 2, cell extract of YPH499 expressing Btn2p-FLAG only and immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody; lane 3, cell extract of YPH499 expressing Btn2p-FLAG and Rsg1p-c-myc immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody. Size markers in kilodaltons are indicated on the left.

btn2Δ strains fail to localize Rsg1p.

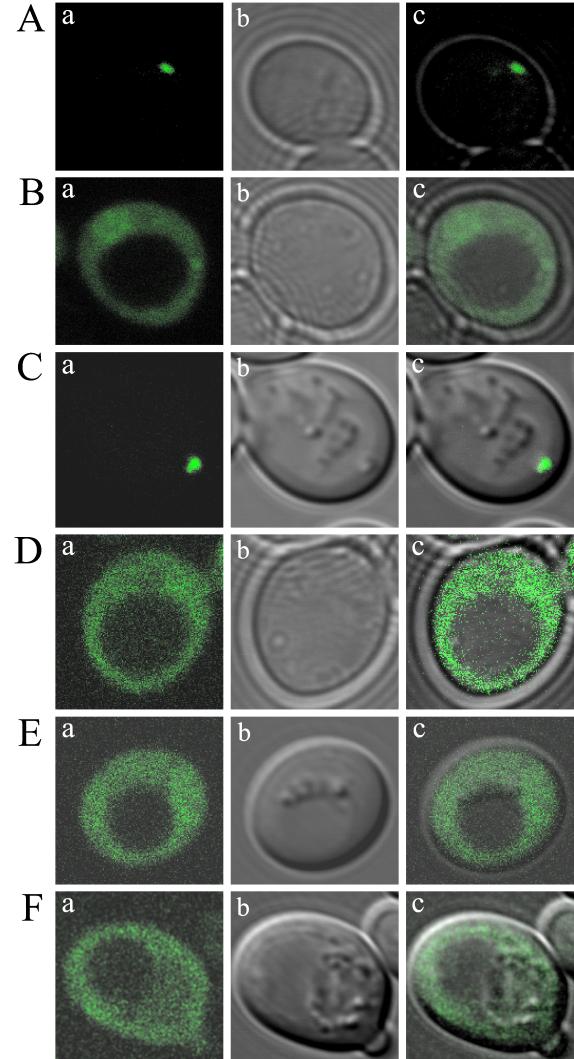

We previously reported that a functional Btn2p-GFP localized to the cytosol (2). We were interested in whether the absence of Btn2p affected the localization of Rsg1p or whether the absence of Rsg1p affected the localization of Btn2p-GFP. The localization of Rsg1p has not been previously reported. Therefore, we localized an N-terminal fusion of GFP to Rsg1p, GFP-Rsg1p, in rsg1Δ and btn2Δ strains and localized a C-terminal fusion of GFP to Btn2p, Btn2p-GFP, in rsg1Δ strains. In Fig. 2A we demonstrate that GFP-Rsg1p localizes to a distinct site toward the periphery of the cell, adjacent to the plasma membrane. On the basis of the reported sensitivity to canavanine of rsg1Δ strains (22), GFP-Rsg1p is functional and is therefore likely to be localized correctly within the cell. Localization of Rsg1p to the periphery of the cell fits with a previous report implicating Rsg1p in regulating the activity of the plasma membrane Can1p permease. Figure 2B indicates that in btn2Δ strains GFP-Rsg1p is no longer localized to a distinct site toward the cell periphery but rather is in the cytosol. This suggests that the absence of Btn2p alters the localization of Rsg1p and that Btn2p may therefore be involved in the trafficking or localization of Rsg1p to the correct subcellular location. This phenomenon is complemented by reintroduction of plasmid-encoded Btn2p, but not the vector only, into rsg1Δ and btn2Δ strains (Fig. 2C and D). In Fig. 2E and F we reconfirm a cytosolic localization for Btn2p and show that rsg1Δ does not alter the cytosolic localization pattern of Btn2p-GFP. Each image shown is typical of what was seen for the entire cell population for each strain.

FIG. 2.

Cellular localization shows that Rsg1p and Btn2p are located at the periphery of the cell adjacent to the plasma membrane and in the cytosol, respectively, and that localization of Rsg1p is altered in btn2Δ strains. (A) GFP-Rsg1p in rsg1Δ strain B-14248; (B) GFP-Rsg1p in rsg1Δ btn2Δ strain B-13053; (C) GFP-Rsg1p in rsg1Δ btn2Δ strain B-14401, which also contains pDAP071 (vector plus BTN2); (D) GFP-Rsg1p in rsg1Δ btn2Δ strain B-14400, which also contains pAA1052 (vector only, no BTN2); (E) Btn2p-GFP in btn2Δ strain B-12388; (F) Btn2p-GFP in rsg1Δ btn2Δ strain B-13053. (a) GFP fluorescence; (b) differential interference contrast; (c) merged images. Each image presented is typical of that seen for the entire cell population.

btn2Δ and rsg1Δ strains are sensitive for growth in the presence of arginine analog canavanine.

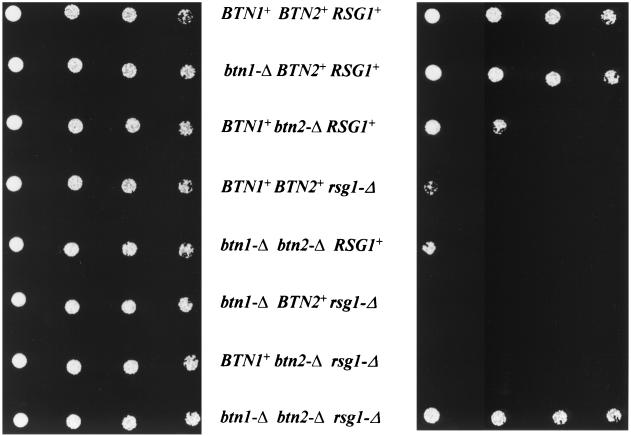

rsg1Δ results in growth sensitivity to canavanine (22). As Btn2p interacts with Rsg1p and as btn2Δ results in Rsg1p not being localized to the periphery of cells, it seemed reasonable to assume that btn2Δ strains would have altered Rsg1p function and would therefore also have growth sensitivity to canavanine. As indicated in Fig. 3, growth of rsg1Δ strains is sensitive to canavanine and btn2Δ strains, while not as sensitive as rsg1Δ strains, do indeed have restricted growth on canavanine media. It is likely that, although btn2Δ strains do not correctly localize Rsg1p, a small portion of the Rsg1p pool does randomly reach the plasma membrane area, thereby giving partial function, resulting in the not-so-tight phenotype on the canavanine media. Not surprisingly, btn2Δ rsg1Δ strains are also sensitive to canavanine.

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of the growth of rsg1Δ and btn2Δ strains to the arginine analog canavanine. Serial dilutions of wild type (B-7553), btn1Δ (B-10195), btn2Δ (B-12641), rsgΔ (B-14249), btn1Δ btn2Δ (B-12642), btn1Δ rsg1Δ (B-13051), btn2Δ rsg1Δ (B-13054), and btn1Δ btn2Δ rsg1Δ (B-14250) strains were used. Wild-type cells grow normally, whereas btn2Δ, rsg1Δ, btn1Δ btn2Δ, btn1Δ rsg1Δ, and btn2Δ rsg1Δ strains show growth sensitivity. The presence of btn1Δ in btn2Δ rsg1Δ strains suppresses the growth sensitivity. (Left) Strains plated on media lacking Arg to verify plating; (right) growth sensitivity on canavanine medium. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 2 days. Reintroduction of plasmid-borne BTN1, BTN2, or RSG1 complements the growth phenotypes shown for the pertinent deletion.

The primary reason for the study of Btn2p function was to determine why expression of BTN2 is increased in the Batten disease yeast model, btn1Δ strains. We therefore tested the effect of canavanine on the growth of a btn1Δ strain and found no associated change in growth (Fig. 3). However, although btn1Δ did not alter the sensitivity to canavanine for either a btn2Δ or rsg1Δ strain, the growth sensitivity of a btn2Δ rsg1Δ strain was completely suppressed by btn1Δ.

Deletion and overexpression of BTN2 result in increased and decreased arginine uptake, respectively.

rsg1Δ strains display sensitivity to arginine analog canavanine as a result of a lack of negative regulation of arginine uptake by the Can1p permease (22). Therefore, we have confirmed that arginine uptake is increased in rsg1Δ strains and show that btn2Δ also results in an increased rate of arginine uptake (Table 2). Arginine uptake is most likely increased in the btn2Δ strain as a result of the mislocalization of Rsg1p in this strain. Furthermore, intracellular levels of arginine are increased in both btn2Δ and rsg1Δ strains relative to the increased rates of uptake that we see: total intracellular arginine levels (means ± standard deviations of four independently grown and extracted samples) for BTN1+ (B-11718), btn2Δ (B-12388), and rsg1Δ (B-14248) strains (OD600, 2.0) were 122 ± 14, 199 ± 19, and 282 ± 15 nmol/108 cells, respectively. These elevated intracellular levels of arginine suggest that the arginine accumulates in the cells. Interestingly, like canavanine sensitivity, elevated uptake of arginine in a btn2Δ rsg1Δ strain is suppressed by btn1Δ (Table 2; Fig. 3). btn1Δ suppresses the sensitivity of growth to canavanine and elevated rate of uptake of arginine for a btn2Δ rsg1Δ strain, which strongly suggests that an absence of Btn1p may require a cell to keep intracellular levels of arginine and lysine down for reasons yet to be ascertained.

TABLE 2.

Rates of [14C]arginine uptake for different strainsa

| Strain no. | Genotype | Rate of [14C]arginine uptake (μmol min−1) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| B-11718 | Wild type | 8.1 ± 0.5 |

| B-13048 | btn1Δ | 7.8 ± 0.2 |

| B-12388 | btn2Δ | 9.8 ± 0.6 |

| B-14248 | rsg1Δ | 11.8 ± 0.3 |

| B-14251 | btn1Δbtn2Δ | 9.5 ± 0.7 |

| B-13052 | btn1Δrsg1Δ | 13.9 ± 0.3 |

| B-13053 | btn2Δrsg1Δ | 13.2 ± 2.9 |

| B-14252 | btn1Δbtn2Δrsg1Δ | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

Arginine uptake was determined by sampling every 15 s after addition of radiolabeled arginine to cells. Uptake was linear with time. Rates were determined from four independent cultures and measurements for each strain. Altered rates of uptake are complemented by reintroduction of plasmid-borne BTN1, BTN2, or RSG1 in the pertinent strain.

One could predict that, in btn1Δ strains, there is a requirement to alter uptake of basic amino acids such as arginine, as up-regulation of Btn2p may modulate uptake of arginine through interaction with Rsg1p. BTN2 is overexpressed by more than eightfold in btn1Δ strains (18). We have confirmed, by further increasing the expression of BTN2 using overexpression vectors, that Btn2p modulates the rate of arginine uptake (Table 3). Therefore, either the absence of Btn2p or the increased presence of Btn2p does in fact alter the rate at which arginine is transported into the cell. Therefore, the eightfold up-regulation of Btn2p in btn1Δ strains may simply keep arginine uptake in check. Such a hypothesis suggests that btn1Δ strains have a requirement to keep arginine at a diminished level or that btn1Δ strains have a requirement for arginine that is energetically too expensive for the cell, resulting in altered control of this process.

TABLE 3.

Rates of [14C]arginine uptake in strains containing overexpression vector pAA1052 or pDAP071a

| Strain no. | Genotype | Rate of [14C]arginine uptake (μmol min−1) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| B-11718 | Wild type | 8.1 ± 0.5 |

| B-12388 | btn2Δ | 9.8 ± 0.6 |

| B-14379 | btn2Δ + pAA1052 | 8.8 ± 0.5 |

| B-14380 | btn2Δ + pDAP071 | 5.2 ± 0.5 |

Arginine uptake was determined by sampling every 15 s after addition of radiolabeled arginine to cells. Uptake was linear with time. Rates were determined from four independent cultures and measurements for each strain.

Functional implication of altered BTN2 expression in btn1Δ strains.

Btn1p is a vacuolar protein, and btn1Δ strains were previously shown to have altered vacuolar pH (18). A direct link between the alteration of vacuolar pH and a possible alteration in the regulation of proteins involved in arginine uptake and in arginine uptake itself remains to be uncovered. However, altered vacuolar levels of arginine and lysine in yeast strains with defective vacuolar function have previously been described (4, 11). Therefore, it is possible that the disturbance in vacuolar function in btn1Δ strains results in a general cellular response to functional stress of this organelle that directly or indirectly results in an alteration in the subcellular distribution and/or uptake of metabolites such as amino acids. Alternatively, Btn1p may play a direct role in maintaining amino acids within the cell, most likely in the vacuole, and disruption of function could specifically alter subcellular distribution or uptake of amino acids. The latter supposition suggests that Btn1p may be directly involved in the transport of amino acids at the vacuolar membrane and that disrupted function precipitates a change in this transport and therefore changes in amino acid levels. If this were the case, altered uptake at the plasma membrane would be downstream of Btn1p function. Moreover this explanation suggests that the altered pH in the vacuole of btn1Δ strains may result from a disturbance in a pH gradient that may drive transport of amino acids. A previous study revealed that btn2Δ results in an elevated activity of the vacuolar H+-ATPase, suggesting that up-regulation of BTN2 expression in btn1Δ strains may also contribute either directly or indirectly to the normalization of the vacuolar pH defect in btn1Δ strains (2). Therefore it is possible that a further understanding of the consequence of increased Btn2p expression may confirm a biological link between basic amino acid uptake and the regulation of vacuolar pH and perhaps vacuolar content.

We have previously demonstrated that the protein associated with Batten disease, the human Cln3 protein, and Btn1p have a conserved function. We previously speculated that the proteins that are usually targeted to the lysosome for degradation could either accumulate or aggregate due to the disturbance in vacuolar/lysosomal pH and may contribute to the accumulation of storage materials in the lysosome characteristic of Batten disease. It may be that altered pH and perhaps altered intracellular levels of metabolites such as arginine precipitate changes in the lysosomal environment resulting in an inhibition of lysosomal function which leads to the accumulation of storage material. btn1Δ strains serve as models for the study of the effects of loss of the human CLN3 gene and colocalization of the human Cln3 protein to synaptic vesicles in neuronal cells (7, 9). A disturbance in the lysosomal content or the levels of certain amino acids, particularly in neurons, may result in a perturbation in the trafficking of proteins implicated in neurotransmission (19) or may directly interfere with metabolism of amino acids involved in neurotransmission, contributing to the causation of Batten disease.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Johannes Hegemann (Heinrich-Heine-Universitaet, Duesseldorf, Germany) for providing the pUG23 and pUG34 GFP fusion plasmids used in this study. We thank Brian Vanwuykhuyse and Gurrinder Bedi (University of Rochester, Microchemical Protein/Peptide Core Facility) for amino acid analyses. We also thank Tim Curran, Paul Roberts, and Shannon Consaul for technical assistance during the course of this study and Fred Sherman for useful discussions.

This study was supported by NIH grant R01 NS36610 and by the JNCL Research Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee, P., A. Dasgupta, A. Siakotas, and G. Dawson. 1992. Evidence for lipase abnormality: high levels of free and triacylglycerol forms of unsaturated fatty acids in neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses. Am. J. Med. Genet. 42:549-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chattopadhyay, S., N. E. Muzzafar, F. Sherman, and D. A. Pearce. 2000. The yeast model for Batten disease: btn1, btn2, and hsp30 alter pH homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 182:6418-6423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croopnick, J. B., H. C. Choi, and D. M. Mueller. 1998. The subcellular location of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of the protein defective in juvenile form of Batten disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 50:335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gent, D. P., and J. C. Slaughter. 1998. Intracellular distribution of amino acids in an slp1 vacuole-deficient mutant of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:752-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goebel, H. H. 1995. The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. J. Child Neurol. 10:424-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall, N. A., B. D. Lake, N. N. Dewji, and N. D. Patrick. 1991. Lysosomal storage of subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase in Batten's disease. Biochem. J. 275:269-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haskell, R. E., C. J. Carr, D. A. Pearce, M. J. Bennett, and B. L. Davidson. 2000. Batten disease: evaluation of CLN3 mutations on protein localization and function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9:735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Batten Disease Consortium. 1995. Isolation of a novel gene underlying Batten disease. Cell 82:949-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvela, I., M. Sainio, T. Rantamaki, V. M. Olkkonen, O. Carpen, L. Peltonen, and A. Jalanko. 1998. Biosynthesis and intracellular targeting of the CLN3 protein defective in Batten disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarvela, I., M. Lehtovirta, R. Tikknen, A. Kyttala, and A. Jalenko. 1999. Defective intracellular transport of CLN3 is the molecular basis of Batten disease (JNCL). Hum. Mol. Genet. 8:1091-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamoto, K., K. Yoshizawa, Y. Ohsumi, and Y. Anraku. 1988. Mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with defective vacuolar function. J. Bacteriol. 170:2687-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kominami, E., J. Ezaki, D. Muno, K. Ishido, T. Ueno, and L. S. Wolfe. 1992. Specific storage of subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase in lysosomes of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten's disease). J. Biochem. 111:278-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohsumi, Y., K. Kitamoto, and Y. Anraku. 1988. Changes induced in the permeability barrier of the yeast plasma membrane by cupric ion. J. Bacteriol. 170:2676-2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer, D. N., I. M. Fearnley, J. E. Walker, N. A. Hall, B. D. Lake, L. S. Wolfe, M. Haltia, R. D. Martinur, and R. D. Jolly. 1992. Mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c storage in the ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease). Am. J. Med. Genet. 42:561-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer, D. N., S. L. Bayliss, and V. J. Westlake. 1995. Batten disease and the ATP synthase subunit c turnover pathway: raising antibodies to subunit c. Am. J. Med. Genet. 57:260-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce, D. A., and F. Sherman. 1997. BTN1, a yeast gene corresponding to the human gene responsible for Batten's disease, is not essential for viability, mitochondrial function, or degradation of mitochondrial ATP synthase. Yeast 13:691-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce, D. A., and F. Sherman. 1998. A yeast model for the study of Batten disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6915-6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearce, D. A., T. Ferea, S. A. Nosel, B. Das, and F. Sherman. 1999. Action of Btn1p, the yeast orthologue of the gene mutated in Batten disease. Nat. Genet. 22:55-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearce, D. A. 2000. Localization and processing of CLN3, the protein associated to Batten disease: where is it and what does it do? J. Neurosci. Res. 59:19-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piper, P. W., C. Ortiz-Calderon, C. Holyoak, P. Coote, and M. Cole. 1997. Hsp30, the integral plasma membrane heat shock protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is a stress-inducible regulator of plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Cell Stress Chaperones 2:12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Urano, J., A. P. Tabancay, W. Yang, and F. Tamanoi. 2000. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rheb G-protein is involved in regulating canavanine resistance and arginine uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11198-11206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]