Abstract

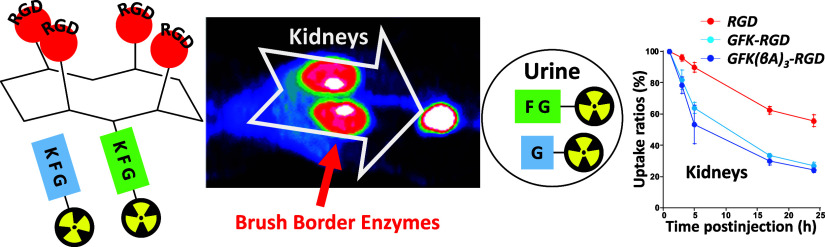

Radiometal-labeled peptide-based radiopharmaceuticals (RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals) are promising for cancer imaging and targeted radiotherapy; however, their effectiveness is often compromised by the high retention of nonspecific radioactivity in the kidneys due to renal excretion pathways. Current strategies to address this issue have limitations, highlighting the need for innovative approaches to improve targeting specificity and therapeutic efficacy. We aimed to evaluate the applicability of the Gly-Phe-Lys (GFK) tripeptide, a renal brush border (RBB) enzyme-cleavable linkage, to reduce renal radioactivity in RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals using the integrin-targeting radiopeptide [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RAFT-c(-RGDfK-)4 ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD). We designed and synthesized the model compound [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(benzoyl [Bz]), its predictive metabolites, and GFK-incorporated [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD derivatives [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(beta-alanine [βA])3-RaftRGD. In vitro studies showed that dual radiometabolites, namely, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF, were simultaneously released from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) by different RBB enzymes, whereas both RaftRGD derivatives released only [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF. When injected into mice, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) and the two RaftRGD derivatives led to the urinary excretion of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF, respectively. PET imaging and biodistribution studies showed the increased rates of reduction in renal radioactivity levels for the two RaftRGD derivatives compared to the parental [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD (e.g., PET: 1 to 24 h postinjection, 73.0 ± 2.3 and 75.6 ± 1.8 vs 43.0 ± 4.5%, p < 0.0001; biodistribution: 3 to 24 h, 61.1 and 74.4 vs 22.8%). Taken together, these results indicate that the designed renal cleavage occurred in vivo. We also noted the steric interference of the RaftRGD moiety on enzyme access, the spacer effect of the trimeric βA sequence (reduced steric hindrance), and the altered radiopharmacokinetics (e.g., initially increased renal accumulation) of the RaftRGD compounds upon linker incorporation. These findings provide important insights into the chemical design of RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals with reduced renal retention based on the RBB strategy.

1. Introduction

Radiometal-labeled peptide-based radiopharmaceuticals (RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals) are promising for cancer imaging and targeted radiotherapy due to the advantages of radiometals and specific peptides.1−4 However, RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals are often limited by high and persistent retention of nonspecific radioactivity in the kidneys.5−7 This is primarily because most radiolabeled peptides (radiopeptides), similar to their unmodified counterparts, are eliminated from the body predominantly through the renal excretion pathway. After initial glomerular filtration, the filtered radiopeptides are partly reabsorbed by renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTECs) and degraded in lysosomal compartments, leading to prolonged retention of radiometabolites in renal cells.8−10 Therefore, the kidneys become the critical or dose-limiting organ for RLPB-radiopharmaceutical therapy because high renal radioactivity levels (RRLs) narrow the therapeutic dose range, compromising effectiveness.11−13 For imaging, high signals in the kidneys can obscure perirenal lesion detection and evaluation, reducing diagnostic accuracy. Therefore, to develop new RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals with improved targeting specificity and efficiency, reducing the RRLs by strategically blocking obstructive renal tubular reabsorption (RTR) is crucial.

Two main strategies have been developed to reduce radiopeptide reabsorption in the kidneys.14−16 One approach involves competitively blocking the endocytic receptors responsible for peptide reabsorption by using positively charged amino acids14,17 or their alternatives.18,19 Currently, coinfusion of lysine and arginine is a standard method for protecting the kidneys during peptide-based radiotherapy.17 However, although rare, side effects can occur.8,14

Another promising approach, known as the renal brush border (RBB) strategy (RBBS), is garnering attention.16 This strategy involves incorporating a small peptide sequence between radiometal chelates and targeting peptide moieties, allowing them to be recognized and cleaved by enzymes present on the RBB membrane (RBBM) lining the lumen of the renal tubules.15,20,21 This enables the release of radiometabolites with high urinary excretion (UE) from the glomerular-filtered radiopeptides before RTR occurs. Arano et al. designed and constructed cleavable linkers with stability in plasma to maintain radioactivity levels in tumors and adaptability to different radiometals.21,22 They developed two tripeptide linkers, Gly-Phe-Lys (GFK) and Met-Val-Lys (MVK), with cleavable G-F and M-V bonds, respectively.23−25 GFK and its variant FGK have been used with [99mTc]Tc/[111In]In-labeled antibody fragments (AFs),23,24,26 while MVK has been utilized with [67/68Ga]Ga- or [64Cu]Cu-labeled AFs via the chelator 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA).25,27 Studies on MVK have also shown promising results for radiolabeled glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists,28−32 prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeting peptidomimetic motif,33 and fibronectin-binding peptides.34 However, these results are still insufficient for therapeutic application, as reviewed by de Roode et al.16 Recently, Brandt et al. incorporated the GFK/MVK linkage into relatively small peptide tracers with molecular weights (MW) < 3 kDa, such as the [64Cu]Cu-labeled somatostatin analog TATE ([Tyr3]octreotate).35 They addressed the issue of premature cleavage in blood circulation by suggesting the attachment of additional albumin binders to improve stability in the blood. However, no reported data exists on the incorporation of GFK into relatively large RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals (> 3 kDa), such as multimeric peptide-based radioligands with enhanced targeting ability.

Previously, we developed an αVβ3 integrin-targeting [64Cu]Cu-labeled 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam)-chelated tetrameric cyclic–Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD) peptide-based radiotheranostic agent [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RAFT-c(-RGDfK-)4 ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD; MW: approximately 4.2 kDa; Figure 1).36,37 [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD can be used for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging37−40 and targeted radiotherapy40−42 owing to the suitable half-life of 12.7 h and multiple decay modes (β+, β–, and Auger electron emissions) of [64Cu]Cu.43 Our previous studies have shown that the coadministration of Gelofusine (succinylated gelatin) and l-lysine with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD resulted in a 30–50% reduction in mouse RRLs.44 Considering the potential applicability of the GFK and MVK linkages to radiometal-labeled AFs and/or peptides, we hypothesize that incorporating such a linkage into the molecular structure of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD can offer an alternative to the aforementioned coadministration approach.

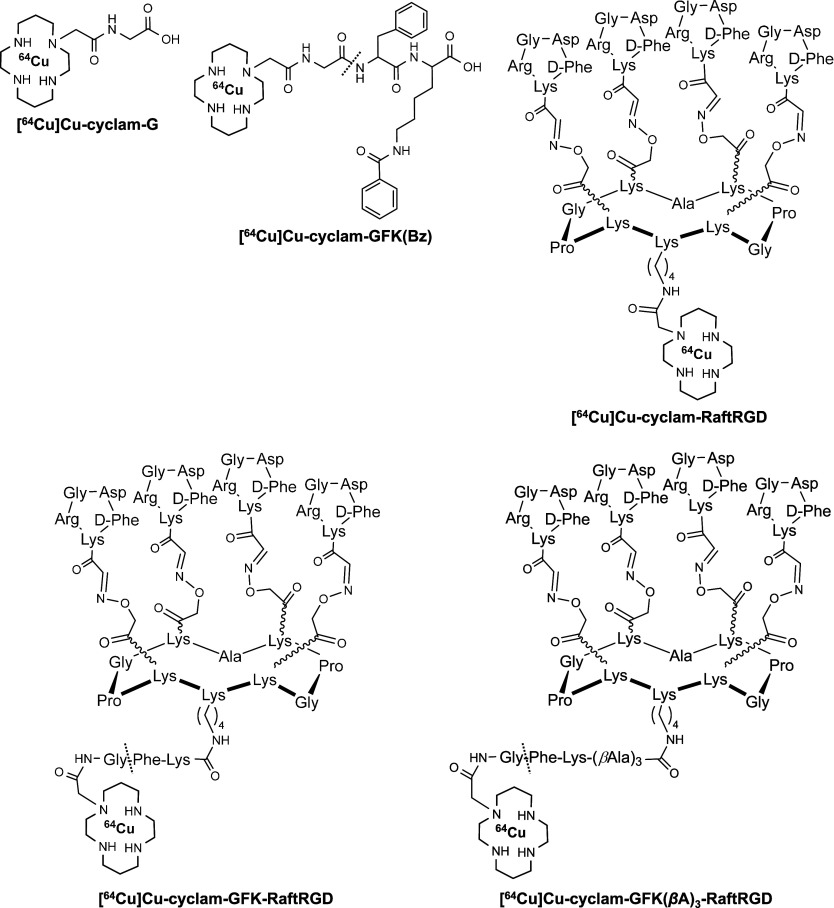

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of [64Cu]Cu-radiolabeled amino acids or peptides using the bifunctional chelator cyclam. The dashed line between G and F indicates the site of renal brush border enzyme cleavage. GFK, Gly-Phe-Lys; Bz, benzoyl; Raft, cyclo(-Lys-Pro-Gly-Lys-Ala-Lys-Pro-Gly-Lys-Lys-); RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp; and βA, beta-alanine.

In this study, we evaluated the applicability of GFK as an RBB enzyme (RBBE)-cleavable linker to reduce RRLs of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD. GFK was selected because its effectiveness has not been thoroughly examined for radiopeptides and another linker, MVK, was primarily developed for NOTA or 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)-chelated complexes and requires caution due to potential radiation-induced methionine oxidation in radiolabeling solutions.45

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Design of Radiocompounds

The GFK linker-based RBB strategic design and modification of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD involves the cleavage and release of a [64Cu]Cu-labeled fragment, with high UE ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G), from the linker-incorporated [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD derivatives (LI-RRDs) (Figure 1). This process occurs at the lumen of renal tubules by enzymes present on RBBMs. In the present study, eight [64Cu]Cu-compounds, in the molecular size order of [64Cu]CuCl2, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-Gly-OH ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-Gly-Phe-OH ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(benzoyl [Bz])-OH ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK[Bz]), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(beta-alanine [βA])3-RaftRGD, were radiosynthesized and investigated. [64Cu]CuCl2 was used for radiolabeling and monitoring dechelated/transmetaled [64Cu]Cu. [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was designed and synthesized as a model compound to study enzyme recognition and cleavage. With this compound, the GFK was modified only at ε-NH2 of K (lysine) with a Bz-protecting group, thus reducing steric hindrance. Having previously reported the design of the RaftRGD peptide46 and the peptide-cyclam conjugation,36 in this study [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD were designed and synthesized as the LI-RRDs mentioned above. The βA tripeptide sequence was inserted between the GFK and RaftRGD motifs to reduce potential steric hindrance from RaftRGD that affected enzymatic access. In the present study, we selected (βA)3 as the spacer because it is a stable (not cleaved by proteases as non-natural amino acids) and flexible linker usually used in peptide research to increase the distance between two functional motifs and prevent mutual interference. [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G was synthesized as a standard for the expected fragment cleaved from the aforementioned [64Cu]Cu-labeled compounds. Lastly, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF were radiosynthesized to identify an unexpectedly detected radiometabolite.

2.2. Synthesis of Cyclam-Gly-OH (Cyclam-G), Radiolabeling, and Pilot PET Imaging

Cyclam-G was synthesized by a commercial consignment based on the reaction of 1,4,8-tritert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-11(carboxymethyl)-cyclam (CM-cyclam[Boc]3) with H-Gly-Trt(2-Cl)-resin (Scheme S1). Cyclam-G was radiolabeled with [64Cu]Cu, achieving a radiochemical yield (RCY) > 99%, as confirmed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Dynamic PET imaging of normal mice within the 0–60 min postinjection (p.i.) period of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G revealed high UE and minimal RTR of this tracer (Figure S1). Renal uptake reached its peak at 20.3 ± 2.9% injected radioactivity dose (%ID)/gram tissue (%ID/g) at 1.5 min p.i., exhibiting a rapid decline to 0.68 ± 0.02%ID/g (96.7% reduction) at 57.5 min p.i., respectively (Figure S1B). Consequently, more than 70% of ID was excreted in urine within 60 min after injection (Figure S1C).

2.3. Synthesis of Cyclam-Gly-Phe-Lys(benzoyl)-OH (Cyclam-GFK[Bz]), Radiolabeling, and Pilot Studies of RBBE Cleavage (RBBEC) and Urinary Radiometabolite

Cyclam-GFK(Bz) was synthesized using the same method as described for cyclam-G, following the standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) solid-phase approach with CM-cyclam(Boc)3 (Scheme S2). Radiolabeling of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was achieved with > 99% RCY, as confirmed by RP-HPLC.

Figure S2A shows the RP-HPLC radioactivity profiles of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) following overnight incubation at 37 °C with mouse serum, mouse urine, or RBBM vesicles (RBBMVs), serving as a source for RBBEs,47,48 with or without an enzyme inhibitor (EI). Notably, the formation of radiometabolite ([64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G) was observed only when [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was incubated with RBBMVs. Furthermore, the release of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was almost completely inhibited by phosphoramidon, an inhibitor of neutral endopeptidase (NEP),49 but remained unaffected by cilastatin, an inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase.50 These findings on EIs are consistent with previously reported results for the [99mTc]Tc-labeled GFK(Boc) model compound.23,24Figure S2B shows the RP-HPLC radioactivity profiles of mouse urine collected at 10 min and 2 h p.i. of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz). In addition to the majority of the radioactivity corresponding to intact [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), 5.9% and 13.8% of the radioactivity were detected at 10 min and 2 h p.i., respectively, exhibiting a retention time (tR) relatively consistent with that of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G. This indicates the enzyme-mediated UE of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz).

The pilot studies of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G (Figure S1) and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (Figure S2) suggested the feasibility of integrating the cleavable GFK into the molecular structure of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-labeled peptides. Based on these findings, a series of additional investigations were performed, with the results detailed and analyzed as follows.

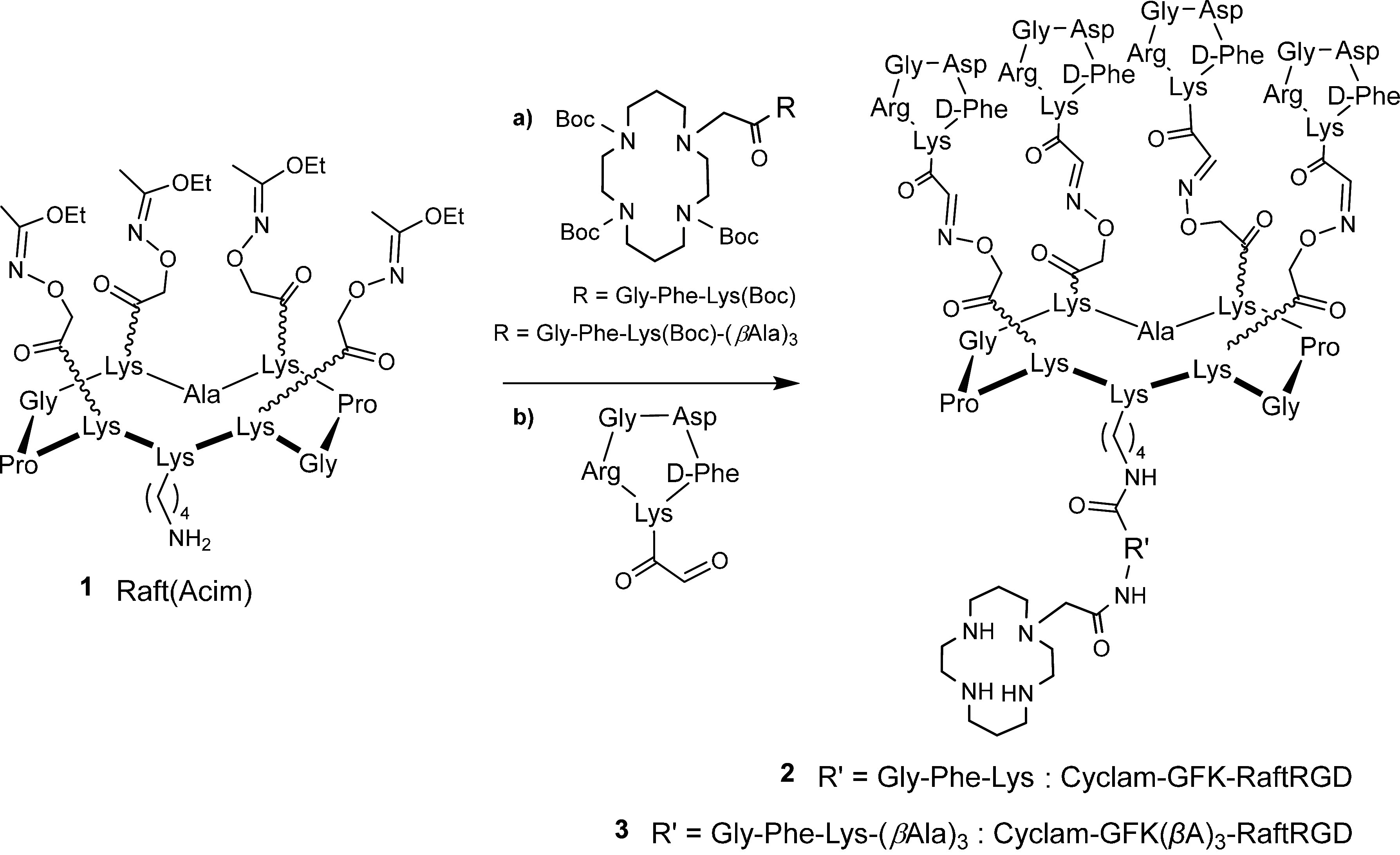

2.4. Synthesis of Cyclam-RaftRGD, Cyclam-Gly-Phe-Lys (GFK)-RaftRGD (Cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD), and Cyclam-GFK(Beta-Alanine)3-RaftRGD (Cyclam-GFK[βA]3-RaftRGD)

The standard cyclam-RaftRGD was synthesized following previously described protocols.36 Cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD were synthesized according to the outlined procedures in Scheme 1. Peptides and cyclam derivatives were synthesized using solid and solution phase peptide synthesis methodologies previously developed by our group.36,51 Cyclam derivatives were added to Raft(acetimidate function [Acim]) (1) using conventional benzotriazol-1-yloxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP) coupling in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) under slightly alkaline conditions. The one-pot deprotection of aminooxy and amino groups, followed by oxime ligation of the aldehyde-RGD compound, was performed under acidic conditions,52 yielding cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD (2) and cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (3). Compounds 2 and 3 were purified by RP-HPLC and unambiguously characterized by both electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), with deconvoluted masses matching the calculated values.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Procedures for Cyclam-Gly-Phe-Lys (GFK)-RaftRGD (2) and Cyclam-GFK(beta-alanine)3-RaftRGD (3).

a) cyclam coupling using benzotriazol-1-yloxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate/N,N-diisopropylethylamine in N,N-dimethylformamide; and b) cyclo(-RGDfK[COCHO]-) coupling in trifluoroacetic acid/H2O/CH3CN (70:15:15). Acim, acetimidate function; and Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl.

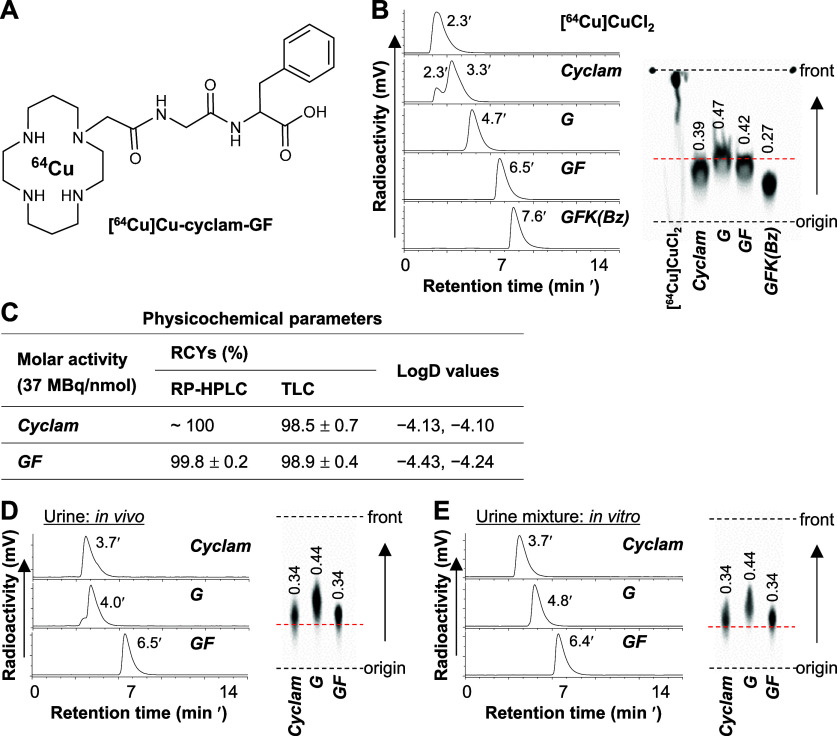

2.5. Radiolabeling of the Cyclam Derivatives and Labeling Efficiency Study

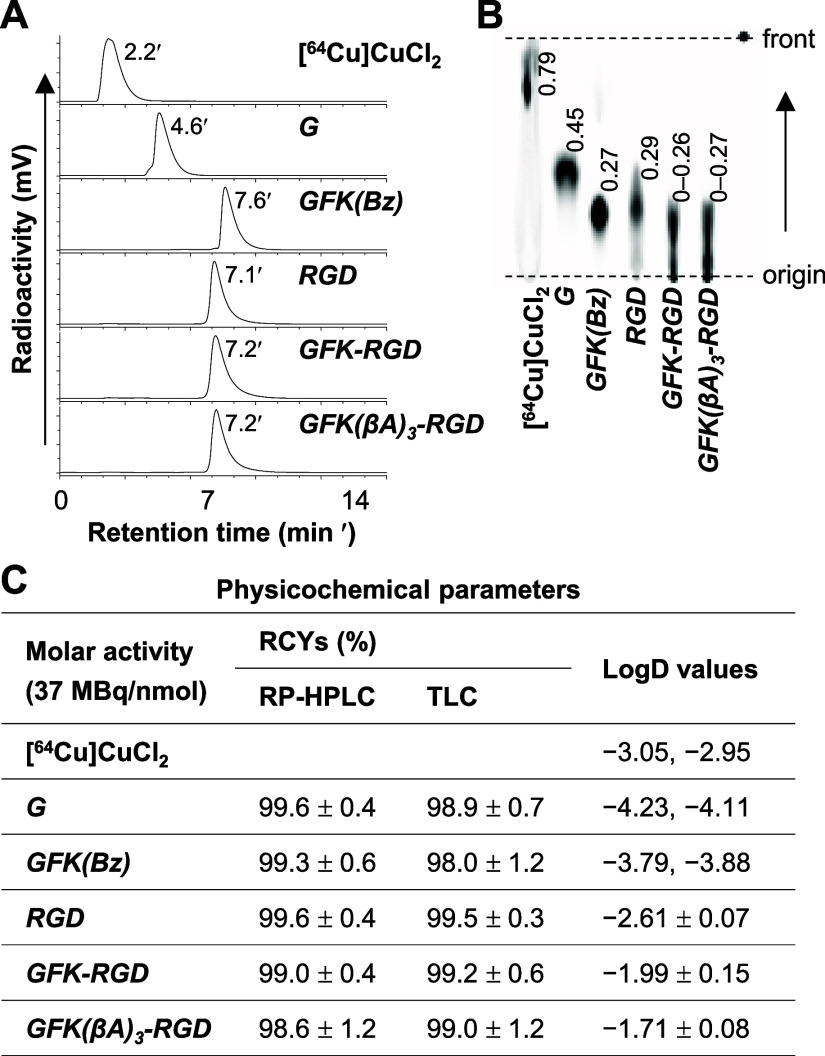

The cyclam derivatives, including cyclam-G, cyclam-GFK(Bz), cyclam-RaftRGD, cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD, were radiolabeled with [64Cu]Cu following the procedures outlined in the Experimental Section. All [64Cu]Cu-labeled compounds had high RCYs (typically > 98%, Figure 2C), with an estimated molar activity (Am) of ≥ 37 MBq/nmol. Each [64Cu]Cu compound exhibited a unique RP-HPLC tR value (Figure 2A) and TLC retention factor (Rf) value (Figure 2B). However, under the current RP-HPLC/TLC assay conditions, both parameters were nearly identical for the two LI-RRDs. The [64Cu]Cu-compounds prepared as described above were used for subsequent experiments unless otherwise stated.

Figure 2.

Radiolabeling and characteristics of [64Cu]Cu-compounds. (A) RP-HPLC radiochromatograms and (B) corresponding TLC images of radiolabeling reaction mixtures of [64Cu]CuCl2 and cyclam-conjugated amino acids or peptides (37 MBq: 1 nmol) after incubation at 90 °C for 15 min. (C) Radiochemical yields (RCYs) determined by RP-HPLC (n = 5–6) and TLC (n = 7–9), and LogD values (n = 2 or 4). G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G; GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz); RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD; GFK-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD; and GFK(βA)3-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD. Values shown in (B) represent the retention factors of radiocompounds.

Figure S3 shows the effect of incorporating the GFK or GFK(βA)3 sequences on the radiolabeling efficiency of cyclam-conjugated RaftRGD. When the lowest dose of 0.033 nmol was incubated with 37 MBq [64Cu]CuCl2, the RCYs of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD were 66.6% and 36.3%, respectively, whereas it was 74.2% with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD. These results indicate that the incorporation of the GFK-based linkers, especially GFK(βA)3, between [64Cu]Cu-cyclam and RaftRGD motifs may change the stability of the metal complex. However, the [64Cu]Cu-radiolabeling efficiency of the two LI-RRDs was sufficient to achieve relatively high levels of Am at 74–185 MBq/nmol compared with 370 MBq/nmol for the parent compound.

2.6. Lipophilicity and In Vitro Stability Studies

Lipophilicity is a basic physicochemical property that can affect the pharmacokinetics of a given biochemical compound.53,54 For radiolabeled compounds, high lipophilicity (high LogD value) can lead to significant plasma protein binding, resulting in delayed blood clearance and increased liver uptake.55,56 The LogD values of all the examined [64Cu]Cu-compounds are shown in Figure 2C. [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G exhibited the least lipophilicity, whereas [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD was the most lipophilic, followed by [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD. These results suggest that the incorporation of either GFK or GFK(βA)3, especially the latter, led to higher lipophilicity compared with unmodified [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD.

Figure S4 shows the results of stability assays for all the evaluated [64Cu]Cu-compounds after incubating in various media, including radiolabeling buffer, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and mouse serum, at 37 °C for 10 min–24 h. Under all tested conditions, all these radiocompounds exhibited high stability (> 97% intact) as determined by TLC. However, a slight degradation (> 83% intact) was observed with the two LI-RRDs when incubated in serum for 24 h (Figure S4A,B). These findings were confirmed by corresponding RP-HPLC analyses (Figure S4C). Collectively, the results of in vitro stability studies suggest that these [64Cu]Cu-compounds possess stability sufficient for further RBBEC and in vivo studies.

2.7. In Vitro RBBEC of the GFK Linkage in [64Cu]Cu-Cyclam Labeled Peptides

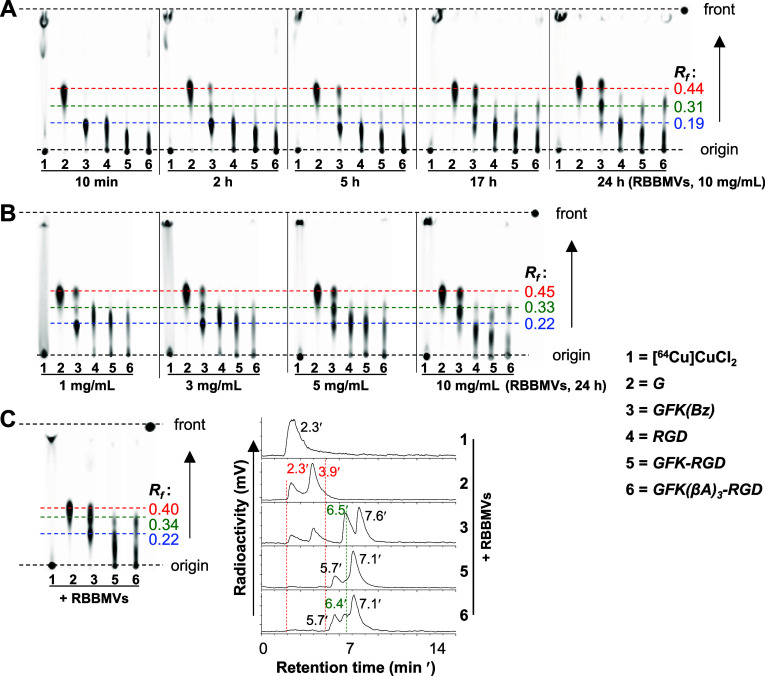

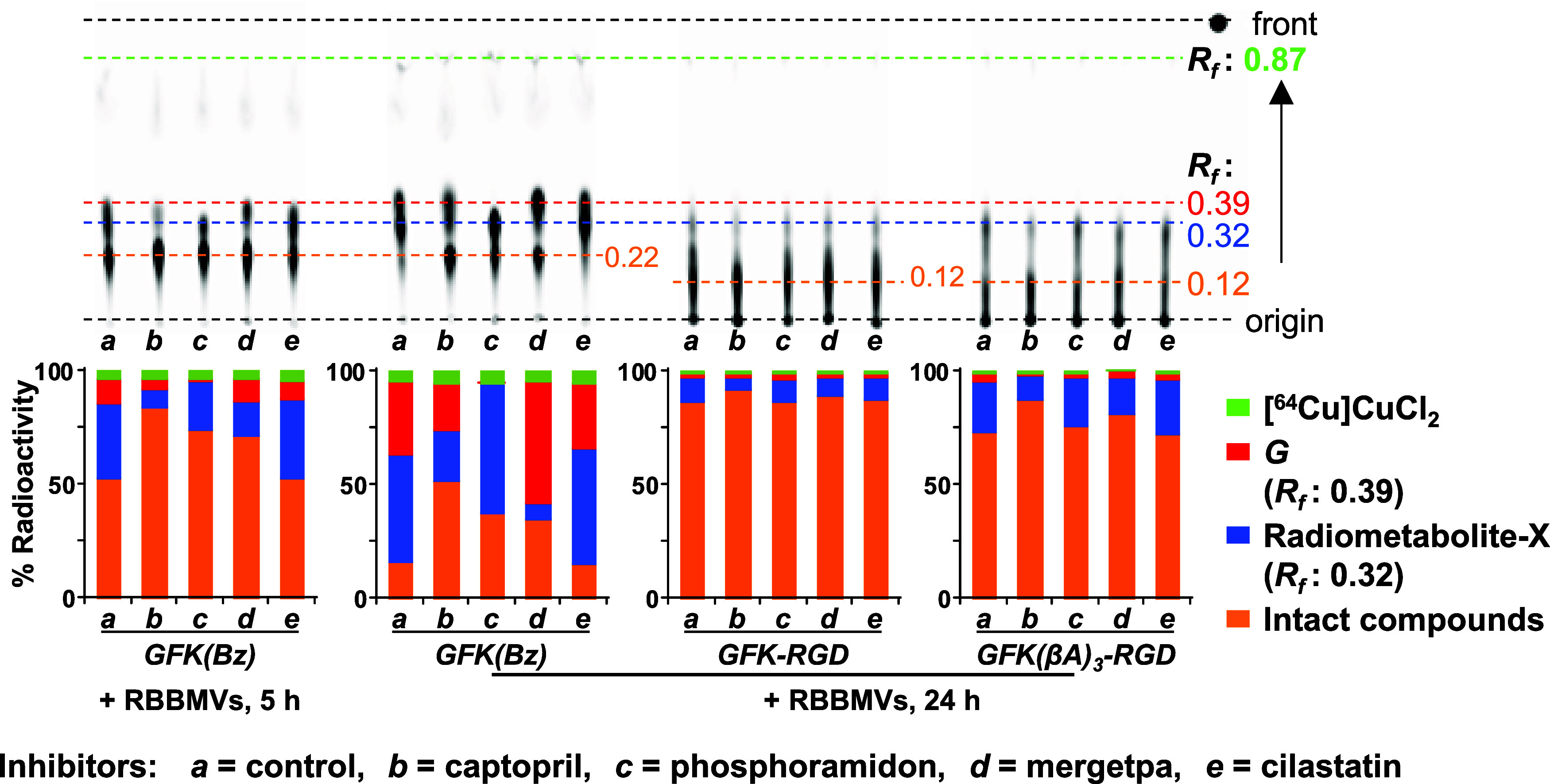

Figure 3A shows the TLC imaging of the radiometabolites observed after incubating the GFK-incorporated radiocompounds (185 kBq/0.005 nmol/μL), along with other [64Cu]Cu-compounds at the same dose for reference, in the presence of RBBMVs (10 mg/mL) at 37 °C as a function of incubation time intervals (10 min–24 h). Upon incubation, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (Rf, 0.19) released the expected fragment [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G (Rf, 0.44) along with an unidentified radiometabolite (Rf, 0.31), hereafter referred to as radiometabolite-X. Conversely, both [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD failed to release [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G but generated only one radiometabolite with a similar Rf value to radiometabolite-X. Quantitative analysis (Figure S5A) summarized the radioactivity levels (% of the radioactivity) of each radiometabolite, demonstrating a time-dependent cleavage by RBBMVs. The release of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and radiometabolite-X from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) occurred at similar radioactivity levels at each time point, indicating a dual-cleavage mode. Comparatively, the extent of release of radiometabolite-X was in the order of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD, and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD at 24 h and 43.7%, 22.9%, and 18.2% of the radioactivity, respectively.

Figure 3.

TLC imaging of cleavage effects of renal brush border membrane vesicles (RBBMVs) on the GFK tripeptide linkage. (A) Time-dependent effect: [64Cu]Cu-compounds (185 kBq/0.005 nmol/μL) were incubated with 10 mg/mL RBBMVs at 37 °C for 10 min, 2, 5, 17, and 24 h. (B) Dose-dependent effect: [64Cu]Cu-compounds (same concentrations as above) were incubated with 1, 3, 5, or 10 mg/mL RBBMVs at 37 °C for 24 h. (C) TLC profiles and corresponding RP-HPLC radiochromatograms: [64Cu]Cu-compounds (same concentrations as above) were incubated with 10 mg/mL RBBMVs at 37 °C for 5 h. G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G; GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz); RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD; GFK-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD; GFK(βA)3-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD; and Rf, retention factor.

The dose-dependent cleavage effect of RBBMVs was similarly investigated (Figures 3B and S5B–D). As mentioned above, the dual-cleavage mode of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) and the sole-cleavage mode of the LI-RRDs were similarly shown, with reproducible results.

An additional study involving TLC and RP-HPLC assays was performed (Figure 3C). By referencing the TLC profiles, the RP-HPLC tRs of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and radiometabolite-X released from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) were found to be 2.3–3.9 and 6.5 min, respectively. The presence of two peaks of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G can be attributed to the formation of stereoisomers because free [64Cu]Cu (tR, 2.3 min) was not detected in the TLC imaging. Radiometabolite-X (tR, 5.7–6.5 min) was observed in the radiochromatograms of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD samples. The radioactivity peak (tR, 5.7 min) likely represented a stereoisomer of radiometabolite-X.

Enzyme inhibition studies were performed by coincubating the compounds with various EIs (Figure 4). The release of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was nearly completely inhibited by the NEP inhibitor phosphoramidon, partially inhibited by captopril (an inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme57), and not inhibited by the dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitor cilastatin and mergetpa (an inhibitor of carboxypeptidase58). These results on the effects of the EIs on [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G release are generally consistent with those reported for [99mTc]Tc-labeled GFK(Boc).23,24 Conversely, the release of radiometabolite-X from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was barely inhibited by phosphoramidon, partially inhibited by mergetpa and captopril, and not inhibited by cilastatin. Similar trends of inhibition were observed with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD. These findings suggest that the liberation of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and radiometabolite-X was differentially inhibited depending on the type of EIs, suggesting recognition and cleavage of the G-F and F–K bonds in the GFK by different RBBEs.

Figure 4.

Differential effects of designated inhibitors on in vitro cleavage actions of renal brush border membrane vesicles (RBBMVs) on the GFK tripeptide linkage. Upper panels: TLC imaging of 185 kBq/0.005 nmol/μL of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (GFK[Bz]), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD (GFK-RGD), and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (GFK[βA]3-RGD) after incubation with 10 mg/mL RBBMVs in the absence (control) or presence of various inhibitors (1 mM) at 37 °C for 5 or 24 h. Lower panels: Quantification of the percentages of radioactivity for each radiocomponent shown in the upper images (n = 1). Rf, retention factor; and G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G.

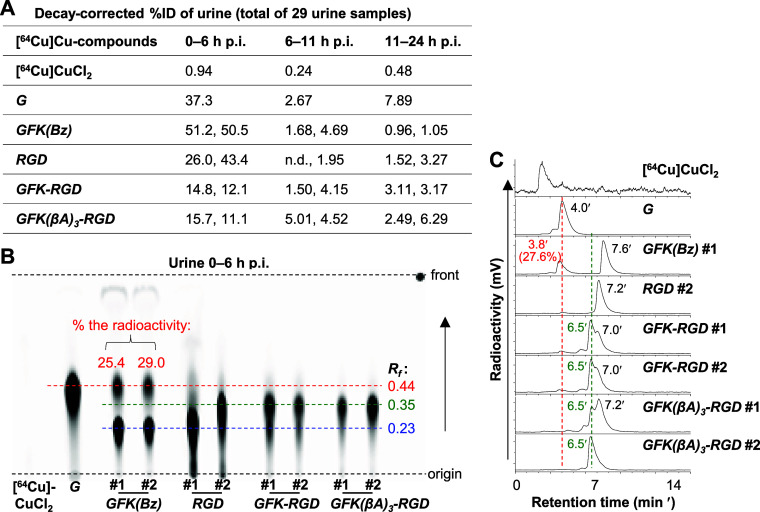

2.8. Radiometabolites in Urine

Figure 5A shows the cumulative radioactivity levels of mouse urine samples at three consecutive times of 0–6, 6–11, and 11–24 h p.i. of each [64Cu]Cu-compound investigated. [64Cu]CuCl2 showed the lowest urinary radioactivity of < 1%ID each time. For other radiocompounds, a majority of urinary radioactivity was excreted in the initial 6 h. The 0–6 h urinary radioactivity levels of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (13.5 ± 1.9%ID and 13.4 ± 3.2%ID, respectively) were much lower than those of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, within the range of 34.7 to 50.9%ID. Based on these results, all urine samples were analyzed by TLC coupled with RP-HPLC.

Figure 5.

In vivo cleavage actions of renal brush border enzymes on the GFK tripeptide linkage examined in normal mice administered intravenously with 7.4 MBq [64Cu]Cu-compounds (0.8 nmol) as indicated. (A) Percentage injected radioactivity dose (%ID; n = 1–2) excreted in urine during each indicated time period. (B) TLC imaging of urine samples collected 0–6 h postinjection (p.i.), and (C) corresponding RP-HPLC radiochromatograms of selected urine samples as indicated. G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G; GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz); RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD; GFK-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD; GFK(βA)3-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD; and Rf, retention factor.

Figure 5B shows the TLC imaging of urine samples obtained 0–6 h p.i., and Figure 5C shows the corresponding RP-HPLC profiles of selected samples. [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) urine on TLC showed 27.2 ± 2.5% and 67.6 ± 3.4% of the radioactivity fractions. These were characterized with Rf, 0.44 (tR, 3.8 min) and Rf, 0.23 (tR, 7.6 min), similar to those of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G standard and the intact [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), respectively. For [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD urine, 56.9 ± 2.0% and 27.7 ± 2.4% of the radioactivity fractions were characterized on TLC with Rf, 0.35 (tR, 6.5 min) and Rf, 0.23 (tR, 7.0 min), similar to those of radiometabolite-X and the intact [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, respectively. In [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD urine, radiometabolite-X was measured with 69.1 ± 4.5% radioactivity. However, the radioactivity of the intact [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (tR, 7.2 min) was much lower and poorly defined for quantification. [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G was not detected in the urine of the two LI-RRDs.

Urine samples collected 6–11 and 11–24 h p.i. were similarly analyzed and the results are summarized in Figure S6. In [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) urine, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and the intact [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) were still detectable at 6–11 h, with no radiometabolite-X (Figure S6A,B). However, in either [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD urine, radiometabolite-X remained predominant during these periods, with no formation of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G (Figure S6A–D). However, the radiometabolite of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, neither [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G nor radiometabolite-X, was detected at these p.i. (Figure S6A–D).

2.9. Synthesis of Cyclam-GF, Radiolabeling, and Identification of Radiometabolite-X

To identify radiometabolite-X, cyclam-GF (Figure 6A, Scheme S3) was synthesized following the same method used for cyclam-G and cyclam-GFK(Bz). Both [64Cu]Cu-cyclam and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF were prepared with high RCYs (typically > 98%) and an estimated Am of 37 MBq/nmol, with very low lipophilicity (Figure 6C). Figure 6D shows the RP-HPLC and TLC results for urine samples of mice obtained 0–6 h p.i. of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G, or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF. [64Cu]Cu-cyclam urine contained only one radiocomponent characterized by Rf, 0.34 and tR, 3.7 min. These values matched those of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam when mixed briefly with mouse urine in vitro (Figure 6E). Compared to other [64Cu]Cu-compounds, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G may exhibit slightly different Rf and/or tR values upon repeated measurements (e.g., Figure 3A–C) or when different solvents are employed (e.g., Figure 6B,E), likely due to their more flexible conformational structures. In contrast, the only radiocomponent detected in [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF urine was characterized by Rf, 0.34 and tR, 6.5 min, which were identical to those of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF standard (Figure 6B). Direct comparison between the Rf and tR profiles of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF with those of radiometabolite-X (Rf, 0.31–0.34 and tR, 6.5 min) shown in Figures 3 and 5 further verified that radiometabolite-X was consistent with the [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF standard. This confirmed the cleavage of the F–K bond. Previous reports on RBBEC assays of radiocompounds incorporating the MVK linkage or the modified sequences showed the release of unidentified fragments along with the initially expected radiometabolite. The expected metabolite was formed by the typical NEP-directed cleavage of the M–V bond.28,29,33 However, no subsequent investigation was performed to identify these unknown radiometabolites, which may include compounds formed by the cleavage of another amide bond of V–K. For further study, replacing the cationic [64Cu]Cu-cyclam with other types of radiometal chelates (e.g., the neutral [99mTc]Tc-chelate or the anionic [64Cu]Cu-TETA) and repeating the experiments should be considered. Such a comparison would help elucidate the cleavage mode and mechanism and further emphasize the importance of linkers with chelates in linkage cleavage.

Figure 6.

Analyses of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF for identification of radiometabolite-X. (A) Chemical structure of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF. (B) RP-HPLC radiochromatograms and corresponding TLC images of radiolabeling mixtures of [64Cu]CuCl2 and cyclam or cyclam-conjugated amino acids or peptides (37 MBq: 1 nmol) after incubation at 90 °C for 15 min. (C) Radiochemical yields (RCYs) determined by RP-HPLC and TLC (n = 3–4), and LogD values (n = 2). (D) RP-HPLC radiochromatograms and corresponding TLC images of urine samples collected 0–6 h postinjection (p.i.) of [64Cu]Cu-compounds (7.4 MBq, 0.2 nmol) as indicated and (E) those of the mixtures of [64Cu]Cu-compounds and mouse urine as standards. Cyclam, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam; G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G; GF, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF; and GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz). Values shown in TLC images indicate the retention factors of radiocompounds.

2.10. Whole-Body Dynamic PET Studies

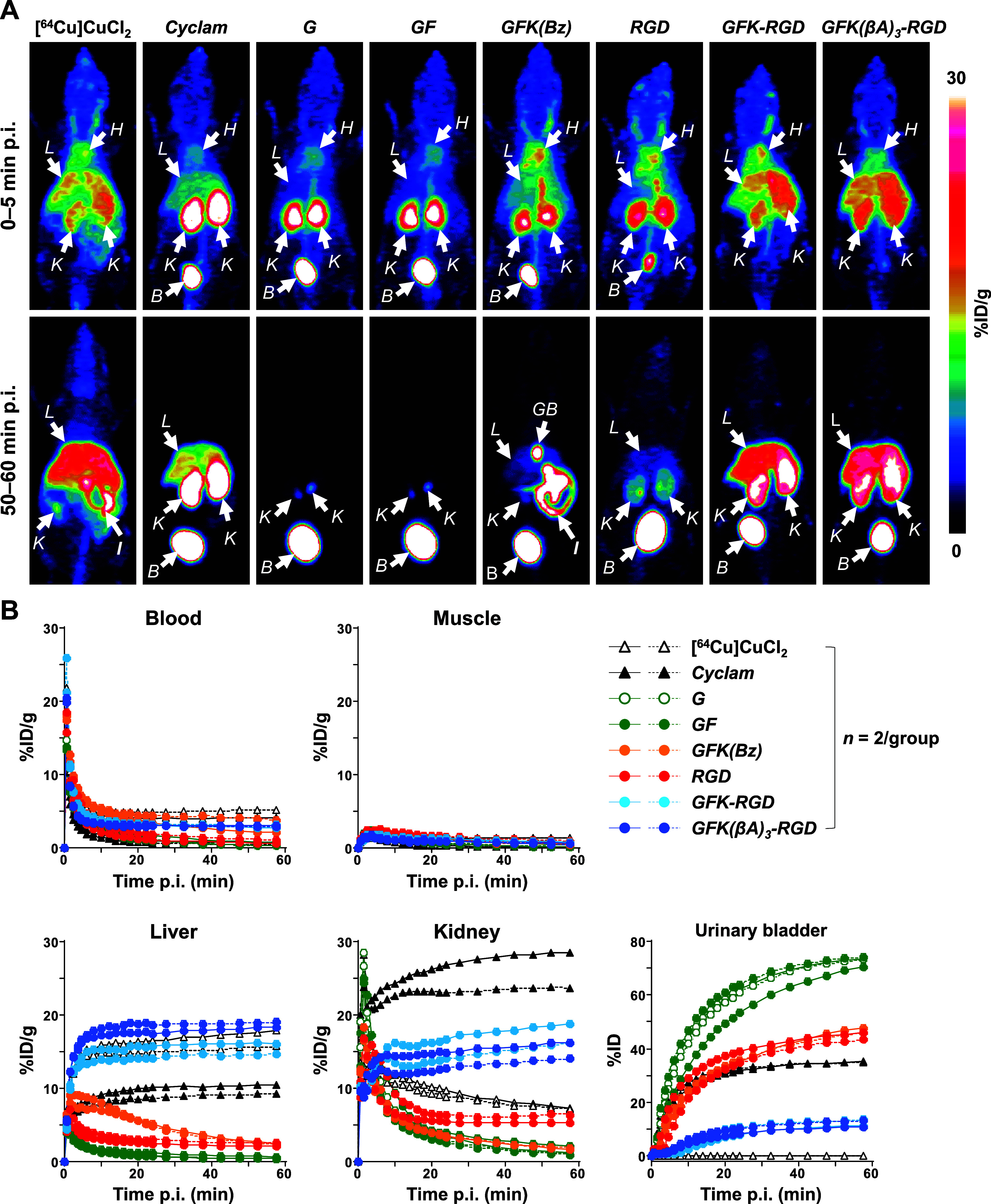

As a quality control prior to in vivo imaging studies, the stabilities of all involved [64Cu]Cu-compounds were further verified by challenging them with 1000-fold molar excess ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (see Figure S7 for details). To determine the effects of GFK/GFK(βA)3 incorporation on the radiopharmacokinetics of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, whole-body dynamic PET imaging was performed in normal mice 0–60 min p.i. (Figure 7A). A direct comparison of the radiopharmacokinetic profiles of these relevant [64Cu]Cu-compounds was made (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

PET imaging of normal mice administered intravenously with 2.92–4.26 MBq of [64Cu]CuCl2 or [64Cu]Cu-labeled compounds (0.3 nmol). Dynamic PET scans were performed 0–60 min postinjection (p.i.). (A) Representative maximum-intensity projection PET images at 0–5 and 50–60 min p.i. (B) Time–activity curves for organs of interest. Cyclam, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam; G, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G; GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz); RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD; GFK-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD; GFK(βA)3-RGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD; B, urinary bladder; GB, gallbladder; H, heart; I, intestine; L, liver; and K, kidney.

[64Cu]CuCl2 and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam were evaluated to monitor their possible release from [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-labeled peptides. [64Cu]CuCl2 exhibited the slowest blood clearance among all the [64Cu]Cu-compounds, high and intermediate levels of radioactivity accumulation in the liver and kidneys, respectively, and less UE. However, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam was rapidly cleared from the blood and all background organs and tissues via the urinary system (> 35%ID in the bladder by 1 h), with the highest and intermediate levels of radioactivity accumulation in the kidneys and liver, respectively.

[64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF showed similar radiopharmacokinetics. They were rapidly cleared from the blood pool and all background organs and tissues via the urinary system (> 70%ID in the bladder by 1 h). The RRLs of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF were as low as 1.14 ± 0.15 and 1.50 ± 0.81%ID/g, respectively, at 57.5 min p.i., exhibiting less RTR. Therefore, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF can be identified as suitable radiometabolites for the GFK-based RBBS. [99mTc]Tc-IPG-G and [99mTc]Tc-MAG3-G, released from [99mTc]Tc-labeled AFs via the GFK-based RBBS,23,24 showed a gradual increase in the intestinal radioactivity levels. IPG and MAG3 represent 2-picolylglycine and mercaptoacetyltriglycine, respectively. This indicates the influence of a metal-chelate structure on the biological behavior of radiometabolites under the same RBB concept.

[64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was rapidly cleared from the entire body via the hepatobiliary and UE pathways. The rapid renal clearance, along with the finding that [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) urinary radioactivity was composed of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (Figure 5B), indicate that [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) is a radiopeptide with low RTR.

As previously reported,44 [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD exhibited a typical renal retention after the two phases of initial rapid uptake (0–5 min p.i.) and fast washout (until ∼ 20 min p.i.), with significant RRLs (e.g., 5.87 ± 0.76%ID/g at 57.5 min p.i.). We expected that such renal retention could be alleviated by using RBBS with the GFK-based linker. However, unexpected results were observed. Compared with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD exhibited relatively slow blood clearance and considerably increased radioactivity accumulation in the liver and kidneys. Regarding the kinetics of RRLs, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD showed a peak (13.6 ± 3.4%ID/g) at 3.5 min p.i., followed by a biphasic (rapid and slow) washout, with the radioactivity decreasing to 5.87 ± 0.76%ID/g at 57.5 min p.i. However, the renal uptake of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD increased to 17.5 ± 1.8 and 15.1 ± 1.4%ID/g, respectively, which was observed by the 60 min dynamic scan. This resulted in 2.98- and 2.57-fold higher RRLs than [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD at 57.5 min p.i. The two LI-RRDs showed less UE compared with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD. In the liver, the time-activity patterns of the two LI-RRDs were similar to those with [64Cu]CuCl2 and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam. They showed much higher liver radioactivity levels than [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, which were comparable to the corresponding level of [64Cu]CuCl2.

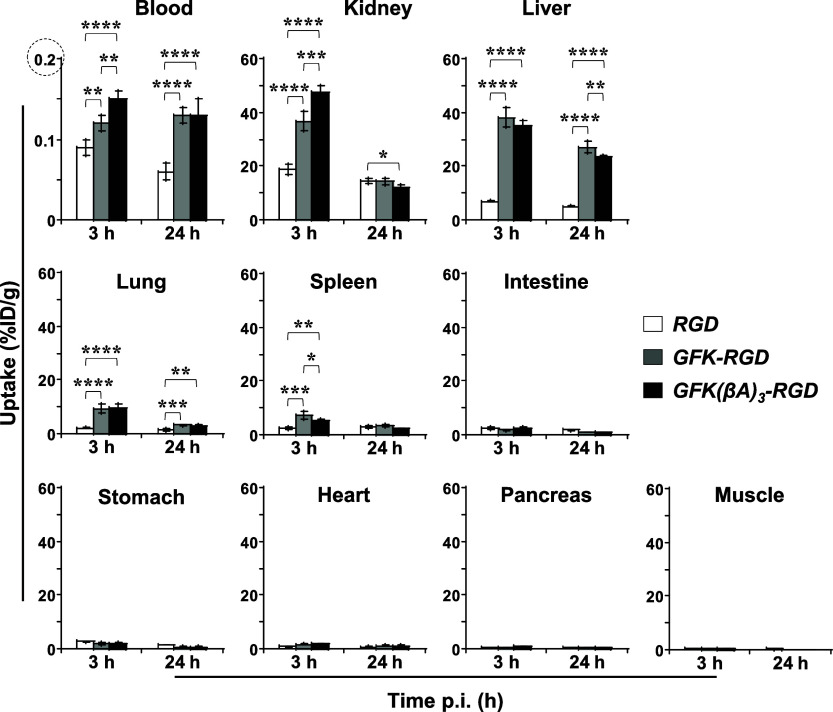

2.11. Ex Vivo Biodistribution Assay

Figure 8 summarizes the biodistribution data of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD and the LI-RRDs at 3 and 24 h p.i., with detailed values shown in Table S1. Consistent with the 0–60 min dynamic PET results, the biodistribution data demonstrated that both LI-RRDs exhibited significantly higher radioactivity uptake in the kidneys, liver, blood, and blood-rich lung and spleen compared to [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD at 3 and/or 24 h p.i. In all three cases, the tissue or organ radioactivity levels generally declined from 3 to 24 h. Notably, for the kidneys, the GFK- and GFK(βA)3-incorporated compounds achieved reductions of 61.1% and 74.4%, respectively, which were significantly larger than the 22.8% reduction observed with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD. However, for the liver, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD and the GFK/GFK(βA)3 compounds exhibited comparable smaller reduction rates of 27.0%, 28.0%, and 34%, respectively. This marked decrease in RRLs observed with the LI-RRDs could be attributed to the occurrence of GFK cleavage. This was confirmed by the detection of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GF as the major radiometabolite in all urine samples (harvested 0–6, 6–11, and 11–24 h p.i.) of both LI-RRDs (Figures 5 and S6). These findings indicate that even after the LI-RRDs were internalized in RPTECs, the designed RBBEC may occur at the internalized membrane fractions before being transported to the lysosomal compartments. However, further studies are needed to support this hypothesis, including evaluation of the stability of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-chelate at the cellular level.

Figure 8.

Effects of incorporating the GFK tripeptide linkage on the biodistribution profiles of the GFK-incorporated [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD derivatives. Normal mice (n = 4/group) were intravenously injected with 0.74 MBq/0.068 nmol of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD (RGD), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD (GFK-RGD), or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (GFK[βA]3-RGD) and examined at 3 and 24 h postinjection (p.i.). *, **, ***, ****p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively.

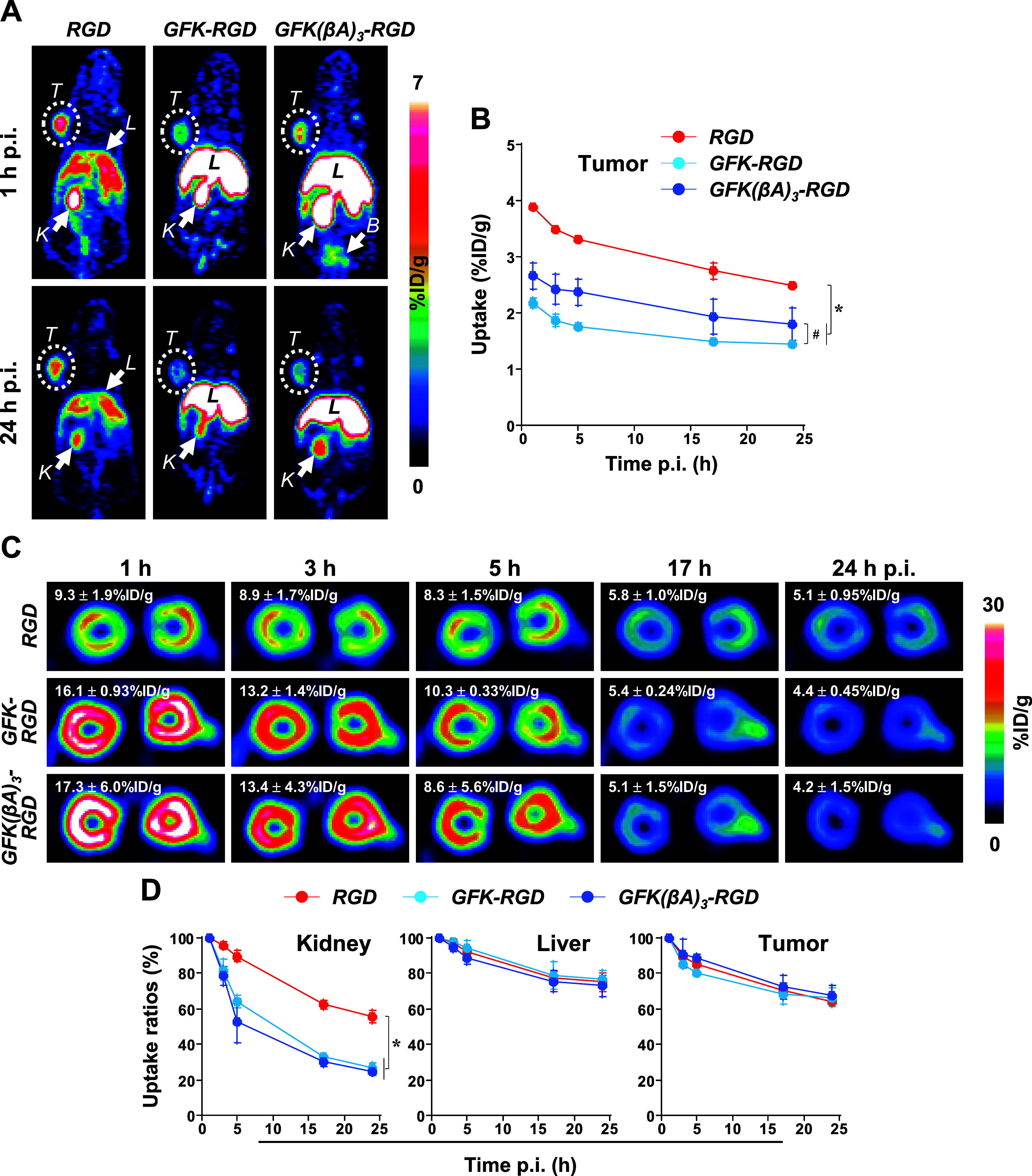

2.12. PET and Post-PET Biodistribution Studies in Tumor-Bearing Mice

Figure 9 summarizes the PET studies of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD and the LI-RRDs in tumor-bearing mice. All three compounds showed clear tumor visualization at all examined time points of 1–24 h p.i., whereas both LI-RRDs exhibited reduced tumor uptake compared to the parental tracer (Figure 9A,B). This decline was mainly due to a decrease in tumor accumulation during the early uptake phase (within 1 h p.i.), with similar rates of decline observed across all compounds from 1 to 24 h (Figure 9D). Notably, of the two LI-RRDs, the tumor uptake levels of the GFK(βA)3 compound were significantly higher than those of the GFK compound at 1–5 h p.i. (Figure 9B), suggesting that the spacer (βA)3 enhances tumor retention.

Figure 9.

PET imaging of U87MG tumor-bearing mice administered intravenously with 16.9–18.3 MBq/0.1 nmol of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD (RGD), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD (GFK-RGD), or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (GFK[βA]3-RGD). Static PET scans were performed at 1, 3, 5, 17, and 24 h postinjection (p.i.). (A) Representative coronal PET images. (B) Chronological tumor uptake levels quantified from PET images. (C) Representative PET images of kidneys (transverse) and renal uptake levels. (D) Chronological uptake ratios of kidney, liver, and tumor relative to values at 1 h p.i. n = 3/group (except n = 2 in the GFK[βA]3-RGD group at 5 h p.i.); B, urinary bladder; L, liver; K, kidney; T, tumor; *p < 0.05 at all the time points; and #p < 0.05 at 1, 3, and 5 h p.i.

For the kidney, PET imaging effectively visualized and quantified the rapid reduction in RRLs achieved by both LI-RRDs (Figure 9C,D). [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD exhibited significantly higher rates of reduction, e.g., from 1 to 24 h p.i., 73.0 ± 2.3% and 75.6 ± 1.8%, respectively, compared to 43.0 ± 4.5% for [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD (p < 0.0001). Conversely, all three compounds showed a similar degree of decrease in the accumulated radioactivity in other tissues, such as the liver and tumors (Figure 9D). These findings further validate the results of the PET and biodistribution studies conducted in normal mice.

The %ID/g values of tumor, liver, and kidney quantified from PET images at 24 h p.i. and post-PET biodistribution measurements are shown in Table S2, with correlations analyzed in Figure S8 for reference.

2.13. Possible Mechanisms for Changes in the Radiopharmacokinetic Properties and Tumor Accumulation of the LI-RRDs

The absence of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam detected in the urine of the LI-RRDs (Figure 5) makes it unlikely that uncoupled [64Cu]Cu-cyclam, which exhibited a high level of renal accumulation, contributed to the elevated renal radioactivity observed with the LI-RRDs. Furthermore, the distinct differences in kidney and urinary bladder radioactivity levels between the LI-RRDs and [64Cu]CuCl2 negate the possibility that [64Cu]Cu dechelation was responsible for the retention of radioactivity in the liver associated with the LI-RRDs.

The increased lipophilicity of the LI-RRDs compared to the parent compound may partly explain their greater accumulation in the liver and kidneys. However, even the less lipophilic [64Cu]Cu-cyclam accumulated considerably in these organs. In any case, the altered pharmacokinetics of the LI-RRDs may reflect some conformational changes upon the GFK/GFK(βA)3 conjugation and may be related to the compromised tumor uptake. Further assays, such as combined chromatography and mass spectrometry of the radiocomponents extracted from tissues of interest, are needed to elucidate the pharmacokinetic changes and to find ways to overcome this problem.

2.14. Renal Handling of the LI-RRDs

Although the precise cause of the increased renal accumulation of LI-RRDs (typically within 1 h p.i.) is unclear, we speculate that the cleavage sequence may serve as a substrate for RBBEs, resulting in higher interaction with the brush border membrane. Therefore, the initial renal uptake would be higher for the cleavage sequence-incorporated compound. In previous studies on AFs,23,25 the molecular size of AFs (∼ 55 kDa) is much larger than that of the cleavage sequence (< 0.4 kDa). Therefore, introducing a cleavage sequence would not affect kidney uptake, and any differences in renal uptake between AFs with and without the sequence would be primarily due to the cleavage effect. However, for LI-RRD, with a smaller molecular size (< 5 kDa), the cleavage sequence itself can influence kidney uptake independently of the cleavage process.

Nevertheless, the results of in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo studies collectively indicate the efficacy of RBBEC by the LI-RRDs. Following glomerular filtration, a portion of the derivatives underwent cleavage by RBBEs on the outer surface of RPTECs, liberating radiometabolites into the urine, while a substantial fraction was uptaken by RPTECs. Subsequently, a significant portion of the internalized compounds underwent cleavage by internalized RBBEs before transport to lysosomal compartments. As the uptake process decreased after 1 h p.i. (Figure 7B [kidney] vs Figure 9D), a rapid decline in RRLs was observed, with either [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD demonstrating greater reductions compared to 64Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD (Figures 8 and 9C,D). This suggests that radiometabolites released from the LI-RRDs were cleared from renal cells significantly faster than those resulting from lysosomal degradation of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD. Moreover, 64Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD exhibited a slightly higher reduction rate (though not statistically significant) compared to 64Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD (Figure 8), indicating a potential enhancement in GFK cleavage possibly because of the alleviation of steric hindrance from RaftRGD by the spacer. Similar trends were observed in the in vitro RBBEC assay (Figures 3 and S5) and in vivo urine metabolism study (Figures 5 and S6), emphasizing the importance of inserting a spacer between the cleavable motif and the targeting peptide. However, such spacers require further rational design to be more effective.

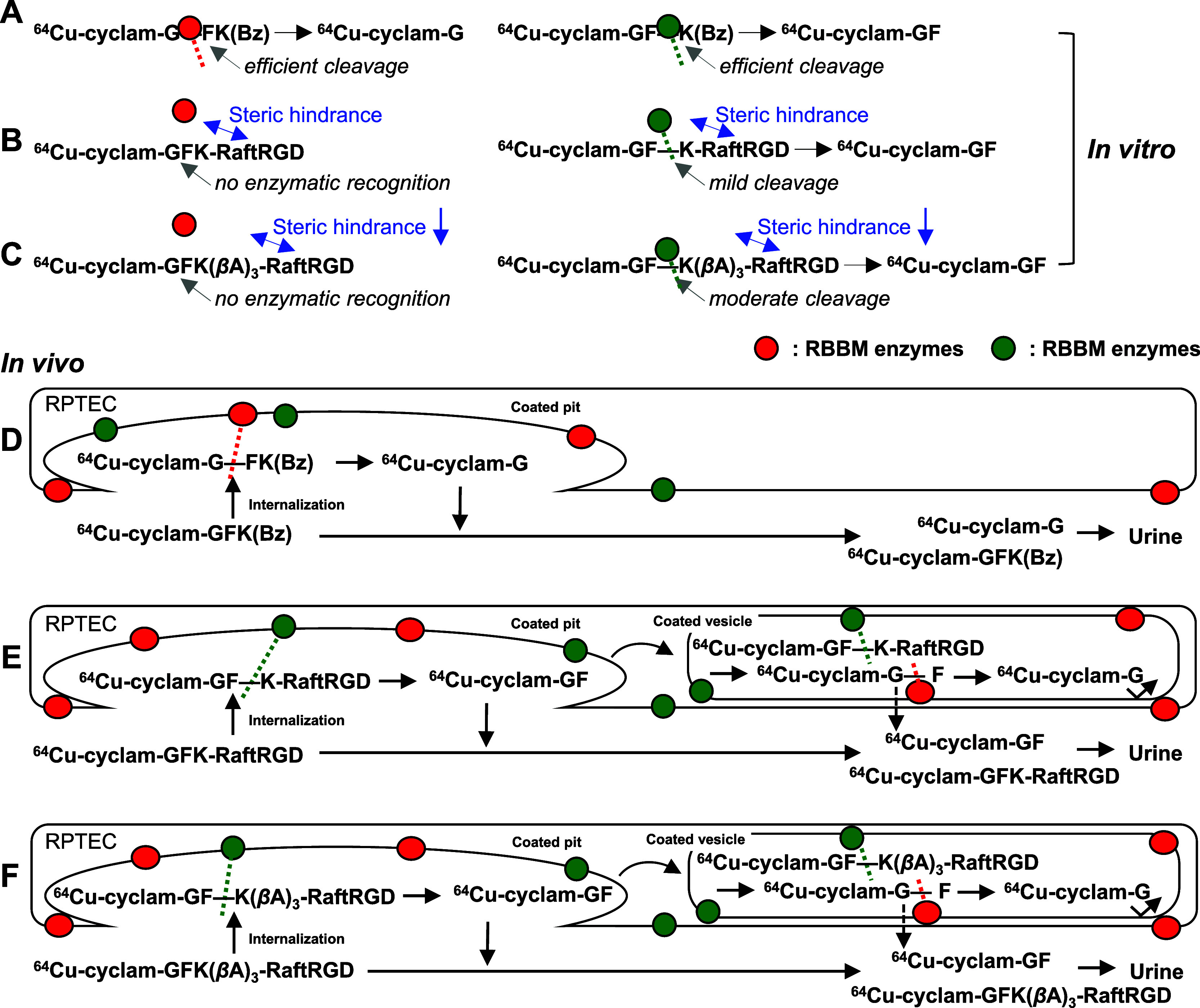

2.15. Suggested Mechanisms of RBBEC

Recent studies by Uehara et al.24 and Suzuki et al.27 have shed light on the renal handling of GFK or MVK sequence-incorporated radiometal-labeled AFs and proposed a novel mechanism. They suggested that the generation of radiometabolites via RBBE-mediated cleavage occurs not only during the internalization process (coated pit formation) of the parent AFs but also during postcoated vesicle formation within renal cells. Moreover, they interpreted differences in enzymatic recognition and cleavage between in vitro and in vivo experimental systems. While in vitro systems using RBBMVs involve direct contact between substrates and enzymes on RBBMVs, in vivo cleavage occurs through both direct physical contact and interactions with coated pits and vesicles.

Building upon these proposed mechanisms and the findings of our study, Figure 10 depicts our suggested in vitro and in vivo mechanisms for RBBE-mediated cleavage of GFK in [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) and the LI-RRDs. In vitro, with adequate physical contact, both the G–F and F–K bonds of GFK in [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) were efficiently cleaved by NEP and other RBBEs, respectively (Figure 10A). However, for [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD (Figure 10B) and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (Figure 10C), presumably due to their relatively large molecular size (> 4.5 kDa) and/or steric hindrance from the bulky RaftRGD moiety, enzymatic contacts were significantly hindered, resulting in the absence of G–F bond or weak cleavage of the F–K bond, respectively. The uncleavable state of the G–F bond was likely due to the molecular size of the parent molecule rather than steric hindrance, making access to NEP challenging. NEP typically cleaves peptides with MW ≤ 3 kDa due to size-restricted access to the catalytic crypt59,60 and might fail to attack the two GFK-incorporated compounds unless they are degraded into smaller fragments, which was not indicated. Inserting the (βA)3 spacer between GFK and RaftRGD motifs tended to improve F–K cleavage but had no effect on G–F cleavage, possibly due to limited access to the NEP enzyme. Fujioka et al. demonstrated that the spacer structure between the parental AF and the substrate (the GK sequence) plays a crucial role in the RBBE-mediated release of the expected radiometabolite.61

Figure 10.

Suggested mechanisms underlying the in vitro (A–C) and in vivo (D–F) cleavage actions of renal brush border membrane (RBBM) enzymes on the GFK tripeptide linkage in [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-labeled compounds. A and D, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz); B and E, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD; and C and F, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD. 64Cu, [64Cu]Cu; and RPTEC, renal proximal tubule epithelial cell.

Similar cleavage mechanisms are illustrated in the in vivo studies (Figure 10D–F). For instance, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) was cleaved only at the G–F bond, suggesting a predominant effect of NEP. Given its low RTR, this model compound was predominantly cleaved extracellularly through simple physical contact and enhanced contact at coated pits of RPTECs. Conversely, for [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD, which exhibited high RTR, cleavage of the F–K bond of GFK may occur both extracellularly and intracellularly, involving interactions during the entire internalization process of coated pits and coated vesicles.

Further, the statement regarding LI-RRD’s enzyme access, limited by molecular size, does not contradict the successful application of the same GFK linkage to AFs, which have a much larger molecular size.23,24In vitro assays using RBBMVs are typically not conducted on AFs23 due to their tendency to adhere to vesicle membranes, obstructing enzymatic access. However, in vivo studies, such as radioiodinated AFs detected in kidney homogenates 10 min p.i.,61 suggest that AFs with cleavable bonds are likely degraded at the membrane and cleaved without major hindrance before being incorporated into renal cells.

2.16. Limitations and Management of the Study

In addition to the foregoing, at least four more limitations need to be noted. First, though the in vitro receptor-binding affinities of the LI-RRDs were not assessed, the addition of a small peptide linker is unlikely to affect the binding affinity due to spatial separation between the targeting domain (the four cRGD motifs) and the functional domain (on the linker side). Second, only urine samples were examined for metabolic studies. Further studies on the liver, kidney, tumor, and other related organs may reveal radiocomponents other than those detected in the urine and facilitate further elucidation of the suggested mechanisms (Figure 10). Third, only one type of spacer, namely (βA)3, was inserted and tested between the GFK linker and RaftRGD motif. To address these, future studies need to consider a more rational design of spacers, considering the effects of not only alleviating the steric hindrance but also modulating the pharmacokinetics of the parent compound. Fourth, only the GFK linker was evaluated in this study. Further structural optimization studies should include testing different potential cleavable linkers and/or a dual or repeated linker approach.

3. Conclusions

This study marks the first incorporation of the RBBE-cleavable tripeptide GFK linker into the molecular structure of a relatively large RLPB-radiopharmaceutical, exemplified by the well-established radiotracer [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, aimed at reducing RRLs based on the RBBS. In addition to the GFK/GFK(βA)3-incorporated [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD derivatives, we also developed a series of reference radiocompounds, including [64Cu]Cu-labeled cyclam, cyclam-G, cyclam-GF, and cyclam-GFK(Bz). We performed in vitro enzyme-mediated cleavage studies, radiometabolic assays in normal mice, and PET imaging and biodistribution studies in normal and tumor-bearing mice. Collectively, the results indicate that (1) the designed renal cleavage occurred both in vitro and in vivo; (2) the spacer effect of (βA)3 on linker cleavage was observed, albeit relatively weak; and (3) the “simple” incorporation of the linker could alter physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of the parental compound, significantly obscuring the expected cleavage effect and affecting tumor uptake. Therefore, further improvements in molecular design that strategically combine cleavable linkers with chelates, targeting moieties, and appropriate spacers are needed. While the present study has not achieved an ideal design yet, we believe it provides important information regarding the critical requirements for adapting the RBBS to RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals in further optimization studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General

[64Cu]CuCl2 was produced in-house at the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology Facility (Chiba, Japan), with an Am of 1.77 ± 1.17 TBq/μmol and a radionuclidic purity exceeding 99.9%. Dried [64Cu]CuCl2 was dissolved in ammonium citrate buffer (ACB; 0.1 M, pH 5.5; 1.85–7.4 MBq/μL before decay) for radiolabeling. Cyclam and 1,4,8-tri-Boc-cyclam (cyclam[Boc]3) were purchased from CheMatech (Dijon, France). Chemicals including Cl-Trt(2-Cl)-resin, captopril, phosphoramidon, and mergetpa were purchased from Iris Biotech (Marktredwitz, Germany), FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan), Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka), and Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada), respectively. Cilastatin was obtained via ethanol extraction from TIENAM (Banyu Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), following previous protocols.48 All commercially available chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Radioactivity (counts per minute, cpm) was measured with decay correction on an automated gamma counter (2480 WIZARD2, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The purity of all tested compounds exceeded 95% as determined by HPLC analysis.

4.2. RP-HPLC Assay

RP-HPLC was conducted on a Waters HPLC system (Nihon Waters K.K., Tokyo) equipped with a Cosmosil 5C18-MS-II column (4.6 mm i.d. × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan). A linear gradient mobile phase was employed, starting from 100% A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid [TFA] in H2O) and 0% B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile), and progressing to 40% A and 60% B over 30 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min (utilized in the pilot study). Alternatively, unless otherwise stated, a gradient from 95% A and 5% B to 0% A and 100% B over 15 min at a flow rate of 1.3 mL/min was used (established for [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD analysis37). Detection was achieved with an online Waters 2489 dual absorbance detector (214 and 254 nm) coupled with a NaI(Tl) radiation detection system (Ludlum Model 44–10 γ-scintillator and Model 2200 Scaler/Ratemeter; Ludlum Measurements Inc., Sweetwater, TX) at an approximately 0.5 min lag time.

4.3. TLC Assay

TLC was performed using TLC silica gel 60 glass plates (RP-18 F254s, Merck Millipore). The stationary phase was loaded with 2.0 μL of the sample solution and developed in a mobile phase composed of a mixture of 10% ammonium acetate/methanol (60:40; or, unless otherwise stated, 40:60, v/v). Radioactive components separated on the plate were exposed to an imaging plate (BAS-MS 2040; Fujifilm Co. Ltd., Tokyo) and scanned using a bioimaging analyzer (FLA-7000, Fujifilm) as previously described. The Rf value of each radioactive component was calculated by measuring the distance traveled by the component relative to the distance traveled by the mobile phase.

4.4. Chemistry: Synthesis of Cyclam-G, Cyclam-GFK(Bz), and Cyclam-GF

Cyclam-G, cyclam-GFK(Bz), and cyclam-GF were commercially synthesized by Scrum Inc. (Tokyo), with detailed synthetic procedures provided in the Supporting Information [SI]). Purification by RP-HPLC (220 nm) yielded products with 99.8–100% purity. MALDI-TOF MS yielded cyclam-G, cyclam-GFK(Bz), and cyclam-GF: calculated/found: 315.2/315.6 (Figure S9B), 694.4/695.5 (Figure S10B), and 462.3/463.9 (Figure S11B), respectively. ESI-MS (positive mode, unless otherwise stated) yielded cyclam-G, cyclam-GFK(Bz), and cyclam-GF: calculated/found: 315.2/316.1 (Figure S9C), 694.4/695.4 (Figure S10C), and 462.3/463.2 (Figure S11C), respectively.

4.5. Synthesis of Cyclam-RaftRGD, Cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and Cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD

Cyclam-RaftRGD was synthesized as previously described.36 Cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD 2 and cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD 3 were synthesized starting from Raft(Acim) 1 and cyclam derivatives, cyclam-GFK and cyclam-GFK(βA)3, respectively (Scheme 1). Both cyclam derivatives were prepared using solid-phase peptide synthesis from Cl-Trt(2-Cl)-resin using standard Fmoc procedures. Raft(Acim) 1 and cyclo(-RGDfK[COCHO]-) were prepared as previously described.36,51

To prepare cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD 2, Raft(Acim) 1 (25 mg, 0.016 mmol) was added to a DMF solution (250 μL) containing cyclam(Boc)3-GFK(Boc) (32 mg, 0.032 mmol, 2 equiv), PyBOP (16.6 mg, 0.032 mmol, 2 equiv), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 11 μL, 0.064 mmol, 4 equiv). After stirring at room temperature (RT) for 2 h, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude material was dissolved in a minimum amount of methylene chloride, precipitated from ether, and washed three times with ether. The resulting crude cyclam(Boc)3-GFK(Boc)-Raft(Acim) compound was added to a TFA/H2O solution (1 mL; 7:3) containing cyclo(-RGDfK[COCHO]-) (32 mg, 0.048 mmol, 5 equiv). After stirring at RT for 15 min, the mixture was purified by RP-HPLC (214 nm) to yield compound 2 as a white powder (6 mg, 0.0014 mmol). MALDI-TOF MS yielded calculated/found: 4451.9/4451.6 (Figure S12B). ESI-MS yielded calculated/found: 4449.3/4451.9 (Figure S12C).

To prepare cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD 3, Raft(Acim) 1 (12 mg, 0.0075 mmol) was added to a DMF solution (250 μL) containing cyclam(Boc)3-GFK(Boc)(βA)3 (18 mg, 0.015 mmol, 2 equiv), PyBOP (7.8 mg, 0.015 mmol, 2 equiv), and DIPEA (5 μL, 0.03 mmol, 4 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred, concentrated, dissolved, precipitated, and washed as described above. The crude cyclam(Boc)3-GFK(Boc)(βA)3-Raft(Acim) compound was then added to the TFA/H2O solution containing cyclo(-RGDfK[COCHO]-) (15 mg, 0.038 mmol, 5 equiv). After purification as above, compound 3 was obtained as a white powder (2.8 mg, 0.0006 mmol). MALDI-TOF MS yielded calculated/found: 4665.2/4665.3 (Figure S13B). ESI-MS yielded calculated/found: 4662.4/4662.6 (Figure S13C).

4.6. Radiometal Labeling

The [64Cu]Cu-radiolabeling of cyclam-conjugated amino acids or peptides was conducted according to previously described procedures.37,42 An aliquot of cyclam-conjugate in 95–100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO in H2O) was mixed with an aliquot of [64Cu]CuCl2 in ACB mentioned above (37–185 MBq/nmol; 1:1–1.5, v/v), and the reaction mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 15 min. After cooling to RT, the mixture was analyzed by RP-HPLC and/or TLC. Radiolabeling methods for cyclam-G and cyclam-GFK(Bz) used in the pilot studies were described in the SI.

To evaluate the influence of the linker incorporation on the radiolabeling efficiency of cyclam-RaftRGD, the [64Cu]Cu-radiolabeling was performed with varying amounts (0.033, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, or 1 nmol/37 MBq) of cyclam-RaftRGD, cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, or cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by TLC by spotting all samples on a single TLC plate for parallel development.

When [64Cu]CuCl2 was used as a reference or standard for other radiocompounds, it was formulated in the same radiolabeling solution as those compounds.

4.7. In Vitro Stability Assay

The stability of [64Cu]Cu-compounds was assessed by incubating them in the radiolabeling buffer (a mixture of DMSO/ACB; 1:1, v/v), PBS, and mouse serum (freshly prepared), respectively. Each of the designated [64Cu]Cu-compounds (2 μL, 0.1 nmol, ∼ 3.7 MBq before decay) was mixed with a 9-fold volume (18 μL) of the radiolabeling buffer, PBS, or serum. Following incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, 2 h, and 24 h, aliquots (2 μL) of the mixture were withdrawn and subjected to TLC analysis. Moreover, representative samples (5 μL aliquots withdrawn after ∼ 24 h incubation) were analyzed using RP-HPLC to validate the results obtained from TLC.

4.8. Lipophilicity (LogD) Measurement

For LogD measurements following the reported method,62 0.37–1.48 MBq/0.168 nmol of each [64Cu]Cu-compound in the radiolabeling buffer (10 μL) was added to a mixture of ultrapure water (1 mL) and n-octanol (1 mL) in 5.0 mL Eppendorf protein LoBind tubes (n = 2 or 4 as indicated). The two solvent phase systems (organic and aqueous phases) were thoroughly mixed using a microtube rotator for 1 h at RT. Afterward, the samples were centrifuged at 1,750 × g for 5 min for separation. Subsequently, an aliquot (600–800 μL) of the aqueous phase was withdrawn followed by an equal volume of organic phase. The radioactivity of the aliquots was then counted. LogD was calculated using the formula: LogD = log10 (mean cpm in octanol/mean cpm in water).

4.9. Enzyme-Mediated Cleavage Assay and Inhibition Study

The RBBMVs were isolated from the renal cortex of male Wistar rats using the Mg/EDTA precipitation method, as previously described.47,48 The in vitro RBBE-mediated cleavage of the tripeptide GFK linkage was initially examined in a pilot study of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), following a previously reported method.23,25,48 Briefly, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (3 μL, 2.5 nmol, ∼ 9.2 MBq before decay) was mixed with a 9-fold volume (27 μL) of mouse serum, mouse urine, RBBMVs (3 mg/mL), or RBBMVs with 1 mM of cilastatin or phosphoramidon. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C overnight (12–15 h) and analyzed using RP-HPLC. Subsequent cleavage assays were conducted using [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD, with other [64Cu]Cu-compounds studied in parallel as authentic standards or references. Time-dependent effects of cleavage were investigated by preincubating a solution of RBBMVs (5 μL, 20 mg/mL; newly prepared) at 37 °C for 10 min, followed by the addition of an equal volume of the solution of each radiocompound (5 μL, 370 kBq/0.01 nmol/μL, 10× diluted in PBS). After 10 min, 2, 5, 17, and 24 h of incubation, 2 μL-aliquots of the reaction mixture were analyzed by TLC.

Dose-dependent effects of cleavage were examined similarly, by mixing an aliquot of RBBMVs at 2, 6, 10, or 20 mg/mL in PBS with an equal volume of the solution of each radiocompound (370 kBq/0.01 nmol/μL) as above. After 5 and 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the reaction mixtures were analyzed by TLC as described above.

An additional cleavage study involving simultaneous TLC and RP-HPLC assays was conducted following 5 h of incubation with 10 mg/mL RBBMVs.

Similar studies (using 5 and/or 24 h of incubation and 10 mg/mL RBBMVs) were conducted in the presence of 1 mM EIs (captopril, phosphoramidon, mergetpa, or cilastatin).

4.10. Animals and Tumor Model

Animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee of the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST; Protocol No. 13–1022–9, Chiba, Japan) and the Chiba University Animal Care Committee. Male Wistar rats (9-week-old, 200–250 g) were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). Normal or tumor-bearing mice (female BALB/cAJcl-nu/nu; CLEA Japan, Inc., Tokyo) at 7–8 weeks of age (19.2–22.6 g) were examined.

The αVβ3 integrin-positive human glioblastoma U87MG cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Mice with subcutaneous U87MG tumors (7–10 mm in diameter) were established as previously reported.44

4.11. Urinary Radiometabolite Assay

A pilot study was conducted using [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz). A normal mouse was intravenously injected with [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (13.3 MBq/12.4 nmol/15 μL in 0.2 mL normal saline), and urine was collected at 10 min and 2 h p.i. for analysis by RP-HPLC. Further metabolic studies were performed using [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz), [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD. Other [64Cu]Cu-compounds were studied in parallel as the authentic standards or references. Mice (n = 1 or 2/group) were injected intravenously with 7.4 MBq of each [64Cu]Cu-compound (0.8 nmol/16 μL or 0.2 nmol/8 μL, as indicated, in 0.2 mL normal saline with 1% Tween 80 [NS/Tw80]41) and housed individually in metabolic cages (3600M021; Tecniplast S.p.A, Buguggiate, Italy) for urine collection at 0–6, 6–11, and 11–24 h p.i. The radioactivity of each urine sample was analyzed using decay correction. Aliquots (2 μL) of all the urine samples were analyzed using TLC. Aliquots (15–20 μL) of certain representative samples were also analyzed using RP-HPLC to validate TLC results. Additional TLC/RP-HPLC assays were performed on the designated [64Cu]Cu-compounds mixed briefly with mouse urine (1:9, v/v) as urine standards.

4.12. EDTA Challenge

Aliquots (18.5 MBq/0.5 nmol/10 μL) of freshly prepared [64Cu]Cu-compounds were mixed with 1000-fold molar excess EDTA solution (0.5 M in H2O; 10:1, v/v) or H2O only (10:1, v/v) as a reference. The mixtures were then incubated at 37 °C for 0–72 h prior to TLC assay as above.

4.13. Small-Animal PET Study

Using an Inveon PET scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN), we performed PET scans following previously established protocols.40,42 Briefly, normal mice (n = 2/group), positioned prone, were anesthetized with 1–2% (v/v) isoflurane and placed on a heating pad to maintain body temperature. Subsequently, they received intravenous injections of the designated radiocompounds (2.92–4.26 MBq/0.3 nmol/3 μL in 0.1 mL NS/Tw80) via a preinstalled tail vein catheter. For the initial pilot study, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G (approximately 7.4 MBq/2 nmol/8 μL in 0.2 mL NS) was administered. Postinjection, a dynamic scan lasting 60 min was conducted, comprising 22 timeframes (1 min ×5, 2 min ×10, and 5 min ×7). Initially, the pilot study employed 20 timeframes (1 min ×4, 2 min ×8, and 5 min ×8). Reconstruction of PET images was performed using a 3D MAP method (18 iterations with 16 subsets; b = 0.2) without attenuation correction. Radioactivity levels (decay-corrected) were quantitatively analyzed by defining volumes of interest in various organs from dynamic images, generating time–radioactivity curves via ASIPro VM Micro PET Analysis software (Siemens). Results were expressed as the (mean) %ID/g (assuming 1 g/cm3 tissue density) and/or %ID, reflecting total activity accumulation in designated organs. Decay-corrected PET images were visualized using Inveon Research Workplace software (version 4.0, Siemens).

4.14. Ex Vivo Biodistribution Study

Normal mice (n = 4/group) received intravenous injections of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (0.74 MBq/0.068 nmol/1.1 μL in 0.2 mL NS/Tw80). At 3 and 24 h p.i., mice were euthanized via isoflurane saturation, followed by cardiac puncture to draw blood. Major organs of interest were promptly harvested, weighed, and radioactivity measured. Decay-corrected %ID/g of each organ was calculated and normalized by multiplying the ratio of the measured body weight (g) to a body weight of 20 g.

4.15. PET and Post-PET Biodistribution Studies of Tumor-Bearing Mice

U87MG tumor-bearing mice (n = 3/group) were injected intravenously with 16.9–18.3 MBq [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, or [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD (0.1 nmol/4.2 μL in 0.2 mL NS/Tw80). Static 5-, 10-, 10-, 15-, and 20 min PET scans were performed 1, 3, 5, 17, and 24 h p.i., respectively. Immediately after the last PET scan for each mouse (24 h p.i.), we measured biodistribution data of tumor and organs of interest as described above.

4.16. Statistical Analyses

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using Student’s t-tests (unpaired and two-tailed) and a one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni test for two-group and multiple comparisons, respectively (KaleidaGraph Version 4.0, Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Correlations were also determined using the KaleidaGraph. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied for statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the “Initiative for the Implementation of the Diversity Research Environment (Collaboration Type, FY 2015)” program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT, Japan) and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-17-EURE-0003, France). The authors M. Degardin and D. Boturyn wish to acknowledge support from the ICMG Chemistry Nanobio Platform (Grenoble, France), on which the peptide synthesis was performed, and the Labex ARCANE and CBH-EUR-GS (ANR-17-EURE-0003). The authors thank the Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences and the Cyclotron Operation Section (QST, Chiba, Japan) for supplying [64Cu]Cu. Finally, all the authors thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACB

ammonium citrate buffer

- Acim

acetimidate function

- AFs

antibody fragments

- Am

molar activity

- βA

beta-alanine

- Boc

tert-butoxycarbonyl

- Bz

benzoyl

- cyclam

1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane

- cyclam(Boc)3

1,4,8-tri-Boc-cyclam

- CM-cyclam(Boc)3

1,4,8-tritert-butoxycarbonyl-11(carboxymethyl)-cyclam

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EI

enzyme inhibitor

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- Fmoc

9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- %ID

percent injected radioactivity dose

- %ID/g

percent injected radioactivity dose/gram tissue

- LI-RRDs

linker-incorporated [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD derivatives

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- MW

molecular weight

- NEP

neutral endopeptidase

- NOTA

1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PET

positron emission tomography

- p.i.

postinjection

- PyBOP

benzotriazol-1-yloxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate

- RBB

renal brush border

- RBBE

renal brush border enzyme

- RBBEC

renal brush border enzyme cleavage

- RBBM

renal brush border membrane

- RBBMVs

renal brush border membrane vesicles

- RBBS

renal brush border strategy

- RCY

radiochemical yield

- Rf

retention factor

- RGD

Arg-Gly-Asp

- RLPB-radiopharmaceuticals

radiometal-labeled peptide-based radiopharmaceuticals

- RP-HPLC

reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- RPTECs

renal proximal tubule epithelial cells

- RRLs

renal radioactivity levels

- RT

room temperature

- RTR

renal tubular reabsorption

- SI

Supporting Information

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TLC

radio–thin-layer chromatography

- tR

retention time

- UE

urinary excretion

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c10621.

Synthetic procedures for cyclam-G, cyclam-GFK(Bz), and cyclam-GF (Schemes S1, S2, and S3, respectively); syntheses of cyclam-G, cyclam-GFK(Bz), and cyclam-GF (Chemistry); radiolabeling of cyclam-G and cyclam-GFK(Bz) in pilot studies (Radiosynthesis); pilot PET imaging of renal and urinary excretion of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-G in normal mice (Figure S1); pilot study of cleavage effects of renal brush border enzymes on [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(Bz) (Figure S2); effect of incorporating the GFK or GFK(βA)3 sequences on the [64Cu]Cu-radiolabeling efficiency of cyclam-conjugated RaftRGD (Figure S3); in vitro stability of [64Cu]Cu-compounds (Figure S4); TLC imaging and quantification of cleavage effects of renal brush border membrane vesicles on the GFK tripeptide linkage (Figure S5); TLC imaging and corresponding RP-HPLC radiochromatograms of urine samples (6–11 and 11–24 h p.i., Figure S6); EDTA challenge of [64Cu]Cu-compounds (Figure S7); correlations between the %ID/g values quantified by PET imaging and corresponding values measured by biodistribution assay (Figure S8); detailed biodistribution data of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD in normal mice (Table S1); PET vs biodistribution data of [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-RaftRGD, [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK-RaftRGD, and [64Cu]Cu-cyclam-GFK(βA)3-RaftRGD in U87MG-tumor bearing mice (Table S2); and compound characterization data (Figures S9–13) (PDF)

Author Contributions

T.F., Z.-H.J., T.U., and D.B. conceived and designed the project. M.D., D.B., and P.D. synthesized the multimeric cRGD compounds. His.S., K.N., and M.-R.Z. prepared [64Cu]CuCl2. Z.-H.J., M.D., T.F., A.B.T., Hir.S., H.W., A.S., and W.A. performed the experiments. All authors, Z.-H.J., M.D., T.F., T.U., A.B.T., Hir.S., H.W., A.S., W.A., His.S., K.N., M.-R.Z., P.D., D.B., and T.H., analyzed and discussed the results. Z.-H.J., M.D., T.U., and D.B. wrote the manuscript draft, T.F. and A.B.T. revised the manuscript, and all authors assisted in paper preparation. A.B.T. and T.H. supervised the project.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kręcisz P.; Czarnecka K.; Królicki L.; Mikiciuk-Olasik E.; Szymański P. Radiolabeled peptides and antibodies in medicine. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32, 25–42. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S.; Malviya G.; Chottova Dvorakova M. Role of peptides in diagnostics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8828. 10.3390/ijms22168828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulova M. B.; Mikuš P. Advances in development of radiometal labeled amino acid-based compounds for cancer imaging and diagnostics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14, 167. 10.3390/ph14020167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalily M. P.; Soydan M. Peptide-based diagnostic and therapeutic agents: Where we are and where we are heading?. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2023, 101, 772–793. 10.1111/cbdd.14180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K.; Shang J.; Xie L.; Hanyu M.; Zhang Y.; Yang Z.; Xu H.; Wang L.; Zhang M.-R. PET imaging of VEGFR with a novel 64Cu-labeled peptide. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 8508–8514. 10.1021/acsomega.9b03953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpati D.; Vats K.; Sharma R.; Sarma H. D.; Dash A. 68Ga-labeling of internalizing RGD (iRGD) peptide functionalized with DOTAGA and NODAGA chelators. J. Pept. Sci. 2020, 26, e3241 10.1002/psc.3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaihani S.; Sadeghzadeh N.; Abediankenari S.; Abedi S. M. [99mTc]-labeling and evaluation of a new linear peptide for imaging of glioblastoma as a αVβ3-positive tumor. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2022, 36, 976–985. 10.1007/s12149-022-01786-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolleman E. J.; Melis M.; Valkema R.; Boerman O. C.; Krenning E. P.; de Jong M. Kidney protection during peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with somatostatin analogues. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 1018–1031. 10.1007/s00259-009-1282-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegt E.; de Jong M.; Wetzels J. F.; Masereeuw R.; Melis M.; Oyen W. J.; Gotthardt M.; Boerman O. C. Renal toxicity of radiolabeled peptides and antibody fragments: mechanisms, impact on radionuclide therapy, and strategies for prevention. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 1049–1058. 10.2967/jnumed.110.075101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus R.; Niyazi M.; Lange-Sperandio B. Radiation-induced kidney toxicity: molecular and cellular pathogenesis. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 43. 10.1186/s13014-021-01764-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert B.; Cybulla M.; Weiner S. M.; Van De Wiele C.; Ham H.; Dierckx R. A.; Otte A. Renal toxicity after radionuclide therapy. Radiat. Res. 2004, 161, 607–611. 10.1667/RR3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolleman E. J.; Krenning E. P.; Bernard B. F.; de Visser M.; Bijster M.; Visser T. J.; Vermeij M.; Lindemans J.; de Jong M. Long-term toxicity of [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate in rats. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 34, 219–227. 10.1007/s00259-006-0232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geenen L.; Nonnekens J.; Konijnenberg M.; Baatout S.; De Jong M.; Aerts A. Overcoming nephrotoxicity in peptide receptor radionuclide therapy using [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumours. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 102–103, 1–11. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigoho D. M.; Bridoux J.; Hernot S. Reducing the renal retention of low- to moderate-molecular-weight radiopharmaceuticals. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 63, 219–228. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J.; Lee H.; Rousseau J.; Bénard F.; Lin K.-S. Application of cleavable linkers to improve therapeutic index of radioligand therapies. Molecules 2022, 27, 4959. 10.3390/molecules27154959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roode K. E.; Joosten L.; Behe M. Towards the magic radioactive bullet: Improving targeted radionuclide therapy by reducing the renal retention of radioligands. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17, 256. 10.3390/ph17020256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwil C.; Apostolidis L.; Rathke H.; Apostolidis C.; Bicu F.; Bruchertseifer F.; Choyke P. L.; Haberkorn U.; Giesel F. L.; Morgenstern A. Dosing 225Ac-DOTATOC in patients with somatostatin-receptor-positive solid tumors: 5-year follow-up of hematological and renal toxicity. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 49, 54–63. 10.1007/s00259-021-05474-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong C.; Yin D.; Li J.; Huang Q.; Ravoori M. K.; Kundra V.; Zhu H.; Yang Z.; Lu Y.; Li C. Metformin reduces renal uptake of radiotracers and protects kidneys from radiation-induced damage. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2019, 16, 808–815. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b01091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.; Pan Q.; Li F. Decreased 68Ga-NOTA-exendin-4 renal uptake in patients pretreated with Gelofusine infusion: a randomized controlled study. J. Pancreatol. 2020, 3, 161–166. 10.1097/JP9.0000000000000053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arano Y. Strategies to reduce renal radioactivity levels of antibody fragments. Q. J. Nucl. Med. 1998, 42, 262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arano Y. Renal brush border strategy: A developing procedure to reduce renal radioactivity levels of radiolabeled polypeptides. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 92, 149–155. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arano Y.; Fujioka Y.; Akizawa H.; Ono M.; Uehara T.; Wakisaka K.; Nakayama M.; Sakahara H.; Konishi J.; Saji H. Chemical design of radiolabeled antibody fragments for low renal radioactivity levels. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki C.; Uehara T.; Kanazawa N.; Wada S.; Suzuki H.; Arano Y. Preferential cleavage of a tripeptide linkage by enzymes on renal brush border membrane to reduce renal radioactivity levels of radiolabeled antibody fragments. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5257–5268. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T.; Kanazawa N.; Suzuki C.; Mizuno Y.; Suzuki H.; Hanaoka H.; Arano Y. Renal handling of 99mTc-labeled antibody Fab fragments with a linkage cleavable by enzymes on brush border membrane. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31, 2618–2627. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T.; Yokoyama M.; Suzuki H.; Hanaoka H.; Arano Y. A Gallium-67/68-labeled antibody fragment for immuno-SPECT/PET shows low renal radioactivity without loss of tumor uptake. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3309–3316. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H.; Araki M.; Tatsugi K.; Ichinohe K.; Uehara T.; Arano Y. Reduction of the renal radioactivity of 111In-DOTA-labeled antibody fragments with a linkage cleaved by the renal brush border membrane enzymes. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8600–8613. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H.; Kise S.; Kaizuka Y.; Watanabe R.; Sugawa T.; Furukawa T.; Fujii H.; Uehara T. Copper-64-labeled antibody fragments for immuno-PET/radioimmunotherapy with low renal radioactivity levels and amplified tumor-kidney ratios. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 21556–21562. 10.1021/acsomega.1c02516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Jacobson O.; Kiesewetter D. O.; Ma Y.; Wang Z.; Lang L.; Tang L.; Kang F.; Deng H.; Yang W.; Niu G.; Wang J.; Chen X. Improving the theranostic potential of exendin 4 by reducing the renal radioactivity through brush border membrane enzyme-mediated degradation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 1745–1753. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Ye J.; Xie Z.; Yan Y.; Wang J.; Chen X. Optimization of enzymolysis clearance strategy to enhance renal clearance of radioligands. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32, 2108–2116. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Ye J.; Xie Z.; Wang Y.; Ma W.; Kang F.; Yang W.; Wang J.; Chen X. Combined probe strategy to increase the enzymatic digestion rate and accelerate the renal radioactivity clearance of peptide radiotracers. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2022, 19, 1548–1556. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel B.; Valpreda G.; Lutz A.; Schibli R.; Mu L.; Béhé M. Reducing kidney uptake of radiolabelled exendin-4 using variants of the renally cleavable linker MVK. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2023, 8, 21. 10.1186/s41181-023-00206-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbs J.; Raavé R.; Boswinkel M.; Glendorf T.; Rodríguez D.; Fernandes E. F. A.; Heskamp S.; Bjørnsdottir I.; Gustafsson M. B. F. New long-acting [89Zr]Zr-DFO GLP-1 PET tracers with increased molar activity and reduced kidney accumulation. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 7772–7784. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c02073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]