Abstract

Purpose

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression may influence the prognosis of patients with localized esophageal cancer. The current study compared the prognostic value of PD-L1 expression between tumor cells and immune cells.

Methods

Archival esophageal tumor tissue samples were collected from patients who received paclitaxel and cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in three prospective phase II trials. PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells was examined immunohistochemically by using the SP142 antibody and scored by two independent pathologists. The association of PD-L1 expression with patient’s outcomes was analyzed using a log-rank test and Cox regression multivariate analysis.

Results

A total of 100 patients were included. PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was positive (≥ 1%, TC-positive) in 55 patients; PD-L1 expression on immune cells was high (≥ 5%, IC-high) in 30 patients. TC-positive status was associated with poor overall survival (OS) (HR: 1.63, P = 0.035), whereas IC-high status was associated with improved OS (HR: 0.44, P = 0.0024). Multivariate analysis revealed that TC-positive, IC-high, and performance status were independent prognostic factors for progression-free survival and that IC-high and performance status were independent factors for OS. Furthermore, the combination of IC-high and TC-negative status was associated with the optimal OS, whereas that of TC-positive and IC-low status was associated with the worst OS.

Conclusion

PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells may have different prognostic value for patients with locally advanced ESCC receiving neoadjuvant CRT. A combination of these two indexes may further improve the prognostic prediction.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-021-03772-7.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, PD-L1, Immune cells, Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, Prognosis

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a prevalent malignant disease in East and Central Asia. At the time of diagnosis, most patients present with locally advanced disease, which can be treated with multimodal therapy with curative intent. However, despite aggressive multimodal therapy, such as neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) plus radical esophagectomy, the long-term survival rate of patients with ESCC is only 30–40% (van Hagen et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2015). Postesophagectomy pathological staging is essential for prognosis (Guo et al. 2015; Oppedijk et al. 2014). Researchers have been investigating prognostic biomarkers based on pretreatment ESCC tumor tissues, but are yet to define them.

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and its receptor program death protein-1 (PD-1) represent an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates T cell activation and function. On binding with PD-L1, PD-1 expressed on T cells transduces inhibitory signaling to help maintain the homeostasis of the adaptive immune system. Dysregulation of PD-L1 and PD-1 signaling occurs in multiple human diseases, including cancers. Since 2014, blockade of the PD-L1/PD-1 immune checkpoint has become an important modality of cancer therapy. As of the end of 2020, multiple anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of more than 20 indications across cancers, including advanced ESCC (Kato et al. 2019; Kojima et al. 2020).

PD-L1 expression has been widely investigated as a predictive biomarker to help identify cancer patients who are likely to benefit from anti-PD-L1/PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade (Song et al. 2019; Aguiar et al. 2016). However, PD-L1 expression on immune cells and tumor cells may have distinct biological and clinical significance because of multiple and variable mechanisms underlying PD-L1 expression. The PD-L1 expression on immune cells and tumor cells is believed to be mainly driven by interferon-gamma secreted by infiltrating T cells following activation. However, PD-L1 expression on tumor cells can also be driven by oncogenes and may contribute to cancer invasiveness (Chen et al. 2014), metastasis, antiapoptosis (Azuma et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2016a, b), resistance to chemotherapy and radiation (Black et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016a, b), epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Alsuliman et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016), cancer stemness (Almozyan et al. 2017), antiautophagy (Clark et al. 2017), and aerobic glycolysis (Chang et al. 2015).

The prognostic value of PD-L1 expression in locally advanced ESCC has been reported (Guo et al. 2018), but the results are inconsistent. Some studies have reported that PD-L1 expression on tumor cells has poor prognostic value (Lim et al. 2016), and others have reported that PD-L1 expression on immune cells has good prognostic value (Hatogai et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). Thus, for patients with ESCC, the difference in the prognostic value of PD-L1 expression between tumor cells and immune cells remains unclear.

In this study, we investigated PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and immune cells obtained from pretreatment esophageal tumor tissues derived from patients with locally advanced ESCC receiving neoadjuvant CRT. We determined the distinct prognostic value of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and immune cells, and we constructed a combined index to improve prognostic prediction.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study included patients with locally advanced ESCC from three prospective clinical trials conducted in our institute from 2000 to 2015 (supplementary Table 1). The study design, protocol treatment, and results have been published before (Lin et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2018). The three trials had similar inclusion and exclusion criteria. In brief, patients with locally advanced ESCC, defined as T3 or N + according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system (6th or 7th edition), with adequate liver, renal, and bone marrow functions and with adequate performance status, were enrolled. All patients received paclitaxel and cisplatin-based neoadjuvant CRT with a total radiation of 40 Gy over 20 fractions. Esophagectomy was performed 4–6 weeks after completing neoadjuvant CRT. Patients who did not undergo esophagectomy received a second course of CRT to an accumulated radiation dose of 66 Gy. Patients with ESCC with archival esophageal tumor tissues available for analysis were retrospectively enrolled in this study, and their clinical stages were reassigned according to the AJCC (7th edition). Other clinical characteristics recorded for analysis included age, sex, ECOG performance status, location of primary esophageal tumor, radical esophagectomy received or not, pathological complete response (pCR) or not, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS).

Immunohistochemistry and analysis

All tissues analyzed were obtained by endoscopic biopsy before the start of the treatment. After reviewing the corresponding hematoxylin–eosin stains, sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were retrieved from the Department of Pathology of our institute. All tissue slides were confirmed to contain suitable tumor lesions representing more than 50% of the tissues based on the hematoxylin–eosin staining. The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed using Tris–EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a pressure cooker. Dual endogenous enzyme block (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) was used before incubation with primary antibody against PD-L1 (dilution 1:100; clone SP142; Ventana, Arizona, USA) overnight at 4 °C. Incubation was then performed with secondary antibody (Dako real envision HRP rabbit/mouse) for 30 min, followed by the application of diaminobenzidine and hematoxylin. PD-L1 expression on immune and tumor cells was independently scored by two pathologists (Liang and Li) according to a published scoring system, and any discrepancy was resolved through consensus (Fehrenbacher et al. 2016). PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was scored as TC0 (< 1%), TC1 (≥ 1% and < 5%), TC2 (≥ 5% and < 50%), and TC3 (≥ 50%). PD-L1 expression on immune cells was scored as IC0 (< 1%), IC1 (≥ 1% and < 5%), IC2 (≥ 5% and < 10%), and IC3 (≥ 10%). PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was categorized as positive (TC-positive: TC 1–3) or negative (TC-negative: TC0). PD-L1 expression on immune cells was categorized as high (IC-high: IC2/3) or low (IC-low: IC0/1). The optimal cutoff values were determined by survival curves of subgroups of TC and IC (Figure S1).

Outcomes and definitions

The study outcomes were pCR, PFS, and OS. pCR was defined as the total clearance of cancer cells in the esophagectomy specimens, including dissected esophagus and lymph nodes, after neoadjuvant CRT. PFS was defined as the time from the start of treatment to the time of the first evidence of tumor progression, recurrence, or death, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as the time from the start of treatment to the time of the patient’s death.

Statistical analysis

The pCR rates of different groups were compared using a Chi-square test. The survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared among patients with different levels of PD-L1 expression by using a log-rank test. Cox univariate and stepwise regression models were used for the multivariate analysis.

Results

Study population

Data from 100 patients with locally advanced ESCC were included. The other 93 patients were not eligible because the archival tissues were not available or were inadequate for analysis. The median patient age was 56 years, and most of the patients (89%) were men. Their baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between the three cohorts (Table S2). In total, 70 patients underwent esophagectomy following neoadjuvant CRT. With a median follow-up duration of 99 months (range: 47–176 months), the median PFS and OS were 14 months and 22 months, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled

| Parameters | Patients (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 56 (36 ~ 76) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 89 |

| Female | 11 |

| ECOG-PS | |

| 0 | 29 |

| 1, 2 | 71 |

| Stage (AJCC 7th ed.) | |

| II | 10 |

| III | 90 |

| Tumor site | |

| Upper | 27 |

| Middle | 49 |

| Lower | 24 |

| Surgery | |

| Yes | 70 |

| No | 30 |

Fig. 1.

a Overall survival and b progression to survival of the whole cohort

PD-L1 expression on the tumor cells and immune cells of pretreatment ESCC tissues

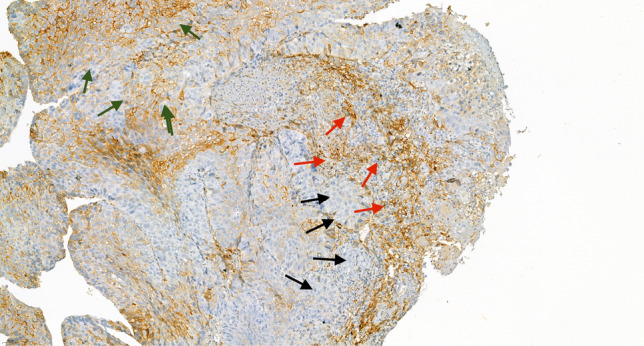

PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and immune cells is demonstrated in Fig. 2. PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was TC0, TC1, TC2, and TC3 in 45, 24, 27, and 4 patients, respectively. PD-L1 expression on immune cells was IC0, IC1, IC2, and IC3 in 27, 43, 24, and 6 patients, respectively. No significant correlation was observed between the PD-L1 expressions on tumor cells and immune cells (χ2 = 1.34, P = 0.51; Table 2). PD-L1 expression on tumor cells or immune cells was not correlated with age, sex, clinical stage, tumor location, or performance status (Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of PD-L1 with membranous expression on tumor cells (green arrows) and immune cells expression infiltrating tumor tissues (red arrows). Regions of negative staining are indicated by black arrows

Table 2.

Association of PD-L1 expression between immune cells and tumor cells

|

X2 = 1.34 P = 0.51 |

Immune cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Tumor cells | Negative | 30 | 15 |

| Positive | 40 | 15 | |

Tumor cells negative < 1%, positive ≥ 1%, immune cells low < 5%, high ≥ 5%

PD-L1 expression and pCR

Among the 70 patients who underwent esophagectomy, 29 (41%) achieved pCR. The pCR rate was higher in patients with IC-high than in those with IC-low status (57 vs 35%), but the difference was not significant. The pCR rates in patients with TC-negative and TC-positive status were similar (42 vs 41%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and immune cells with pCR

| Parameters | pCR | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor cells | Negative | 15/36 (42%) | 1 |

| Positive | 14/34 (41%) | ||

| Immune cells | Low | 17/49 (35%) | 0.11 |

| High | 12/21 (57%) | ||

Tumor cells negative < 1%, positive ≥ 1%, immune cells low < 5%, high ≥ 5%

PD-L1 expression and patient survival

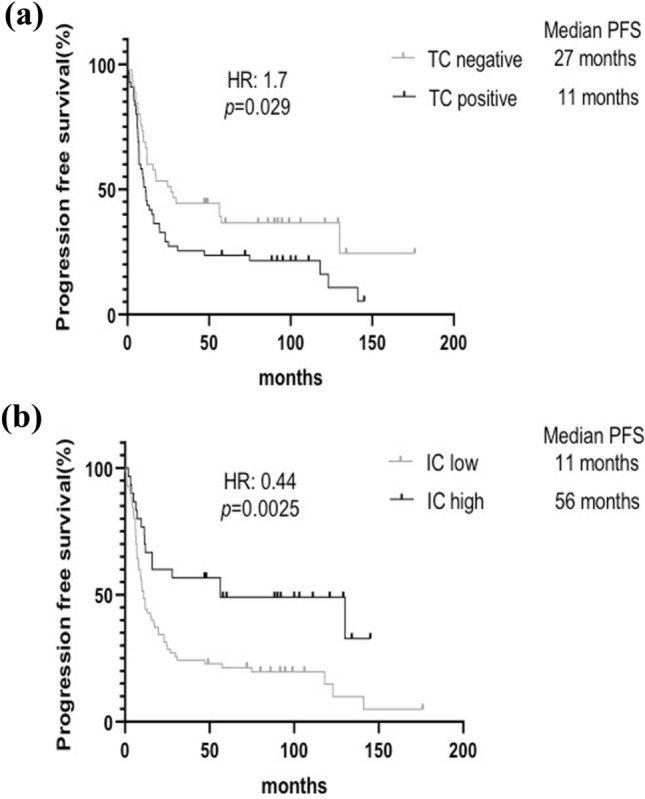

Patients with TC-positive status had significantly shorter PFS [hazard ratio (HR): 1.7, P = 0.029) than those with TC-negative status (Fig. 3a). Patients with IC-high status had significantly longer PFS (HR: 0.44, P = 0.0025) than those with IC-low status (Fig. 3b). In the univariate analysis (Cox regression model), ECOG-PS performances status 0 (vs. 1 or 2), esophagectomy (vs. no esophagectomy), and IC-high status (vs. IC-low status) were significantly associated with longer PFS; TC-positive status (vs. TC-negative status) was significantly associated with shorter PFS (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, sex, ECOG performance status, esophagectomy, PD-L1 TC expression, and PD-L1 IC expression remained significant factors for PFS.

Fig. 3.

Progression-free survival curves of patients with a TC-positive versus TC-negative and b IC-high versus IC-low. The survivals were compared by log-rank test

Table 4.

Regression analysis for progression-free survival

| Variables | Patients (n = 100) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age (years) | 100 | 1.02 (1.00 ~ 1.05) | 0.08 | 1.00 (0.96 ~ 1.03) | 0.74 |

| Gender | |||||

| F vs M | 11 vs 89 | 0.78 (0.53 ~ 1.16) | 0.22 | 0.33 (0.14 ~ 0.78) | 0.011* |

| ECOG-PS | |||||

| 0 vs 1, 2 | 29 vs 71 | 0.72 (0.55 ~ 0.96) | 0.023* | 0.40 (0.22 ~ 0.73) | 0.003* |

| Stage | |||||

| II vs III | 10 vs 90 | 0.92 (0.62 ~ 1.36) | 0.67 | 1.20 (0.52 ~ 2.78) | 0.66 |

| Location | |||||

| Middle vs upper | 49 vs 27 | 0.69 (0.41 ~ 1.17) | 0.17 | 1.07 (0.61 ~ 1.88) | 0.81 |

| Lower vs upper | 24 vs 27 | 0.83 (0.45 ~ 1.53) | 0.55 | 0.89 (0.47 ~ 1.70) | 0.73 |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes vs no | 70 vs 30 | 0.66 (0.52 ~ 0.84) | 0.001* | 0.42 (0.25 ~ 0.71) | 0.001* |

| PD-L1 expression on TC | |||||

| Positive vs negative | 45 vs 55 | 1.29 (1.02 ~ 1.63) | 0.031* | 1.69 (1.01 ~ 2.83) | 0.044* |

| PD-L1 expression on IC | |||||

| High vs low | 30 vs 70 | 0.66 (0.50 ~ 0.87) | 0.003* | 0.34 (0.18 ~ 0.63) | 0.001* |

Tumor cells negative < 1%, positive ≥ 1%, immune cells low < 5%, high ≥ 5%

* <0.05

Patients with TC-positive status had significantly shorter OS (HR: 1.63, P = 0.035) than those with TC-negative status (Fig. 4a). Patients with PD-L1 IC-high status had significantly better OS (HR: 0.44, P = 0.0024) than those with IC-low status (Fig. 4b). In the univariate analysis by Cox regression model, ECOG-PS performances status 0 (vs. 1 or 2), esophagectomy (vs. no esophagectomy), and PD-L1 IC-high status (vs. IC-low status) were significantly associated with improved OS, and PD-L1 TC-positive status (vs. TC-negative status) was significantly associated with poor OS (Table 5). On multivariate analysis, sex, ECOG performance status, esophagectomy, and PD-L1 IC expression remained significant for OS.

Fig. 4.

Overall survival curves of patients with a TC-positive versus TC-negative and b IC-high versus IC-low. The survivals were compared by log-rank test

Table 5.

Regression analysis for overall survival

| Variables | Patients (n = 100) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age (years) | 100 | 1.03 (1.00 ~ 1.05) | 0.05* | 1.00 (0.98 ~ 1.04) | 0.72 |

| Gender | |||||

| F vs M | 11 vs 89 | 0.80 (0.54 ~ 1.18) | 0.25 | 0.39 (0.17 ~ 0.91) | 0.030* |

| ECOG-PS | |||||

| 0 vs 1,2 | 29 vs 71 | 0.73 (0.55 ~ 0.97) | 0.027* | 0.47 (0.26 ~ 0.85) | 0.012* |

| Stage | |||||

| II vs III | 10 vs 90 | 0.93 (0.63 ~ 1.38) | 0.73 | 1.17 (0.51 ~ 2.66) | 0.72 |

| Location | |||||

| Middle vs Upper | 49 vs 27 | 0.63 (0.37 ~ 1.07) | 0.087 | 0.89 (0.51 ~ 1.55) | 0.68 |

| Lower vs Upper | 24 vs 27 | 0.79 (0.43 ~ 1.45) | 0.45 | 0.88 (0.46 ~ 1.67) | 0.69 |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes vs No | 70 vs 30 | 0.70 (0.55 ~ 0.89) | 0.003* | 0.51 (0.31 ~ 0.85) | 0.010* |

| PD-L1 of TC | |||||

| Positive vs Negative | 45 vs 55 | 1.28 (1.02 ~ 1.62) | 0.036* | 1.62 (0.97 ~ 2.71) | 0.068 |

| PD-L1 of IC | |||||

| High vs Low | 30 vs 70 | 0.66 (0.50 ~ 0.87) | 0.003* | 0.38 (0.21 ~ 0.69) | 0.001* |

Tumor cells negative < 1%, positive ≥ 1%, immune cells low < 5%, high ≥ 5%

* <0.05

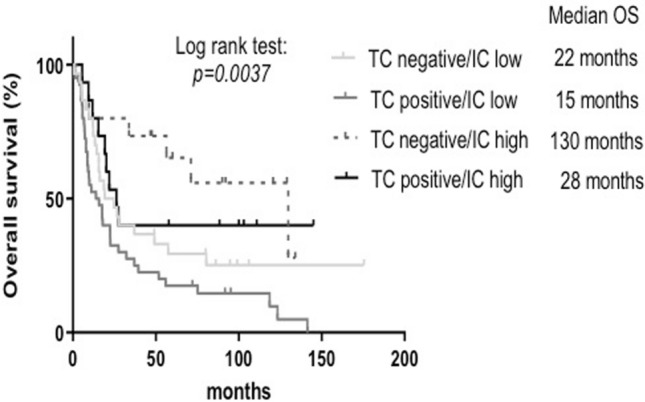

Combined predictor of PD-L1 expression on immune cells and tumor cells

The analyses indicated that PD-L1 expression may have different prognostic effects between tumor and immune cells. Therefore, we combined the PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells to improve predictive performance. As presented in Fig. 5, we divided the patients into four subgroups according to their PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells. We found that patients with TC-negative and IC-high status had the optimal OS (median: 130 months) and those with TC-positive and IC-low status had the worst OS (median: 15 months; P = 0.0037; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Overall survival curves of four subgroups: TC-negative/IC-low, TC-positive/IC-low, TC-negative/IC-high, and TC-positive/IC-high. The survivals were compared by log-rank test

Discussion

This retrospective study demonstrated the prognostic value of PD-L1 expression on immune cells and tumor cells for patients with locally advanced ESCC who received paclitaxel and cisplatin-based neoadjuvant CRT. Our study demonstrated opposite effects of PD-L1 expression on prognosis between tumor and immune cells: TC-positive status was associated with inferior survivals, and IC-high status was associated with improved survivals.

Studies examining the prognostic value of PD-L1 on tumor and immune cells for locally advanced ESCC (Table 6) have shown inconsistent results, which may result from differences in study populations. Hatogai et al. and Jesinghaus et al. have enrolled patients who underwent surgery alone, whereas Lim et al. and Zhang et al. have enrolled patients who received neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment in addition to surgery. These studies also used different antibodies for immunohistochemical analysis of PD-L1 expression and different cutoff values for high or positive expression. The studies of patients undergoing surgery alone demonstrated that PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was associated with good prognosis (Hatogai et al. 2016; Jesinghaus et al. 2017); however, Lim et al. reported that it was associated with poor survival. High PD-L1 expression on immune cells was associated with good survival in two studies (Hatogai et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). In contrast to previous reports, we included patients with locally advanced ESCC treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy using paclitaxel/platinum, which is a standard-of-care endorsed by contemporary treatment guidelines worldwide. Our results may therefore be more relevant and informative to current clinical practice.

Table 6.

Published studies on the prognostic value of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and immune cells for locally advanced ESCC

| Study | Patient number | Treatment | PD-L1 IHC antibody | PD-L1( +) percentage | Overall survival (HR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hatogai (2016) | 196 | Surgery | E1L3N | IC: 60.7% | IC: 0.59, P = 0.01* |

| TC: 18.4% | TC: 0.46, P = 0.016* | ||||

| Lim (2016) | 73 | NAC/NCRT + surgery | 5H1 | IC: 60% | IC: 1.44, P = 0.82 |

| TC: 56% | TC: 2.29, P = 0.023* | ||||

| Zhang (2017) | 344 | Surgery + / − RT | SP142 | IC: 25% | IC: 0.72, P = 0.015* |

| TC: 15% | TC: ns | ||||

| Jesinghaus (2017) | 125 | Surgery | SP263 | IC: 30% | IC: ns |

| TC: 29% | TC: 0.56, P = 0.026* |

NAC neoadjuvant chemotherapy, NCRT neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, R/T adjuvant radiotherapy, ns not significant

* <0.05

Several recent meta-analyses have indicated the differential prognostic value of PD-L1 expression between tumor and immune cells. A 2017 meta-analysis of 60 clinical studies with 10,310 patients and 15 cancer types reported that high expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells is generally associated with poor prognosis (Wang et al. 2017). Another meta-analysis including 2877 patients with ESCC from six studies reported similar results (Guo et al. 2018). However, another meta-analysis of 18 studies enrolling 3674 patients with 12 cancer types evaluated the prognostic value of PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating immune cells (Zhao et al. 2017), and the authors concluded that higher PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating immune cells is related to a lower risk of death. The differential prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression between tumor and immune cells may be attributed to their distinct underlying biologies. PD-L1 expression on tumor cells can be driven by their intrinsic oncogene activation and can increase tumor aggressiveness, drug resistance, and metastasis. These mechanisms may explain the poor prognostic impact of PD-1 expression on tumor cells. However, PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating immune cells likely reflects an existing adaptive anticancer immunity in the tumor microenvironment. Several studies have demonstrated that PD-L1 on immune cells, especially macrophages and other myeloid cells, contributes to immune evasion and the response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy (Tang et al. 2018; Noguchi et al. 2017; Lau et al. 2017; Tang et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2018).

We demonstrated that combining the PD-L1 expressions on tumor and immune cells may improve the predictive performance. Specifically, patients with TC-negative and IC-high status had the highest OS (median: 130 months) and those with TC-positive and IC-low status had the lowest OS (median: 15 months). If validated, this index may help categorize patients with locally advanced ESCC to receive individualized therapies.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample size was smaller than those of other studies; however, our cohort had relatively homogeneous clinical and treatment characteristics compared to other studies. Our patients were prospectively enrolled in three clinical trials in a single institute. All patients were scheduled to receive neoadjuvant CRT, which was uniform among the cohorts and in line with current standards. However, there is slight heterogeneity of treatment among the three clinical trials. The phase II trial “Phase II Study of Metabolic Response to One-Cycle Chemotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma” had one cycle of induction chemotherapy before neoadjuvant CRT with the study aim to evaluate the predictive value of metabolic response to the single cycle of chemotherapy. But, adding one cycle of chemotherapy to neoadjuvant CRT did not improve the pCR rate or outcomes of the patients (Huang et al. 2018). Second, we did not use an independent cohort to validate our findings and did not calculate the prognostic sensitivity or specificity of PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells. Third, we used the PD-L1 antibody clone SP142, which is not a standard practice for ESCC. Currently, clones 28–8 and 22C3 are used for ESCC treated with nivolumab and pembrolizumab, respectively. However, other clones of PD-L1 antibodies have not been compared for patients with ESCC.

In conclusion, our results revealed that PD-L1 expression on immune cells is a favorable prognostic factor for patients with locally advanced ESCC who have received paclitaxel and cisplatin-based neoadjuvant CRT; moreover, PD-L1 expression on tumor cells is a poor prognostic factor. Combining PD-L1 expressions on tumor and immune cells may improve prognostic performance, and this combined indicator should be validated in larger-scale studies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the statistical assistance provided by the Department of Medical Research, NTUH.

Author’s contributions

Guarantor of the article: TC Huang. JWL and YIL independently reviewed and scored PD-L1 expression. YJC performed immunohistochemical staining. TCH and JCG collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to interpretation of data. TCH, CHH, and YKT drafted the manuscript. CCL, ALC and CHH provided critical revision of the draft for important intellectual content. All authors critically reviewed content and approved final version for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant for investigator-initiated trials (NCTRC200909) from the National Clinical Trial and Research Center of National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan; a grant (NTUH 110-S5021) from the Department of Medical Research Internal of National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan; two grants (MOST 105-2314-B-002-186-MY3, MOST 108-2314-B-002-076-MY3) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Executive Yuan, Taiwan. The role of these funding sources is to support scientific research in Taiwan.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee Office of National Taiwan University Hospital (201712154RINA).

Consent to participate

Waiver of consent was approved by the Research Ethics Committee Office.

Consent to publish

Waiver of consent was approved by the Research Ethics Committee Office.

Data availability

Raw data is available when requested.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ann-Lii Cheng, Email: chihhunghsu@ntu.edu.tw, Email: alcheng@ntu.edu.tw.

Chih-Hung Hsu, Email: chihhunghsu@ntu.edu.tw, Email: alcheng@ntu.edu.tw.

References

- Aguiar PN Jr, Santoro IL, Tadokoro H, de Lima LG, Filardi BA, Oliveira P et al (2016) The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a network meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 8:479–488. 10.2217/imt-2015-0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almozyan S, Colak D, Mansour F, Alaiya A, Al-Harazi O, Qattan A et al (2017) PD-L1 promotes OCT4 and Nanog expression in breast cancer stem cells by sustaining PI3K/AKT pathway activation. Int J Cancer 141:1402–1412. 10.1002/ijc.30834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsuliman A, Colak D, Al-Harazi O, Fitwi H, Tulbah A, Al-Tweigeri T et al (2015) Bidirectional crosstalk between PD-L1 expression and epithelial to mesenchymal transition: significance in claudin-low breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer 14:149. 10.1186/s12943-015-0421-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma T, Yao S, Zhu G, Flies AS, Flies SJ, Chen (2008) B7–H1 is a ubiquitous antiapoptotic receptor on cancer cells. Blood 111:3635–3643. 10.1182/blood-2007-11-123141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M, Barsoum IB, Truesdell P, Cotechini T, Macdonald-Goodfellow SK, Petroff M et al (2016) Activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint confers tumor cell chemoresistance associated with increased metastasis. Oncotarget 7:10557–10567. 10.18632/oncotarget.7235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck AD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD et al (2015) Metabolic competition in the tumor microenvironment is a driver of cancer progression. Cell 162:1229–1241. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Deng H, Lu M, Xu B, Wang Q, Jiang J et al (2014) B7–H1 expression associates with tumor invasion and predicts patient’s survival in human esophageal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7:6015–6023 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jiang CC, Jin L, Zhang XD (2016b) Regulation of PD-L1: a novel role of pro-survival signalling in cancer. Ann Oncol 27:409–416. 10.1093/annonc/mdv615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MF, Chen PT, Chen WC, Lu MS, Lin PY, Lee KD (2016a) The role of PD-L1 in the radiation response and prognosis for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma related to IL-6 and T-cell immunosuppression. Oncotarget 7:7913–7924. 10.18632/oncotarget.6861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CA, Gupta HB, Curiel TJ (2017) Tumor cell-intrinsic CD274/PD-L1: a novel metabolic balancing act with clinical potential. Autophagy 13:987–988. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1280223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J et al (2016) Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1837–1846. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JC, Huang TC, Lin CC, Hsieh MS, Chang CH, Huang PM et al (2015) Postchemoradiotherapy pathologic stage classified by the american joint committee on the cancer staging system predicts prognosis of patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 10:1481–1489. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Wang P, Li N, Shao F, Zhang H, Yang Z et al (2018) Prognostic value of PD-L1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 9:13920–13933. 10.18632/oncotarget.23810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatogai K, Kitano S, Fujii S, Kojima T, Daiko H, Nomura S et al (2016) Comprehensive immunohistochemical analysis of tumor microenvironment immune status in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 7:47252–47264. 10.18632/oncotarget.10055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TC, Hsu CH, Lin CC, Tu YK (2015) Systematic review and network meta-analysis: neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locoregional esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 45:1023–1028. 10.1093/jjco/hyv119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TC, Lin CC, Wu YC, Cheng JCH, Lee JM, Wang HP et al (2018) Phase II study of metabolic response to one-cycle chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Formos Med Assoc 118:1024–1030. 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesinghaus M, Steiger K, Slotta-Huspenina J, Drecoll E, Pfarr N, Meyer P et al (2017) Increased intraepithelial CD3+ T-lymphocytes and high PD-L1 expression on tumor cells are associated with a favorable prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and allow prognostic immunogenic subgrouping. Oncotarget 8:46756–46768. 10.18632/oncotarget.18606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, Okada M, Lin CY, Chin K et al (2019) Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:1506–1517. 10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30626-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Koh J, Kim MY, Kwon D, Go H, Kim YA et al (2016) PD-L1 expression is associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Hum Pathol 58:7–14. 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T, Shah MA, Muro K, Francois E, Adenis A, Hsu CH et al (2020) Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-181 study of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 38:4138–4148. 10.1200/JCO.20.01888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J, Cheung J, Navarro A, Lianoglou S, Haley B, Totpal K et al (2017) Tumour and host cell PD-L1 is required to mediate suppression of anti-tumour immunity in mice. Nat Commun 8:14572. 10.1038/ncomms14572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SH, Hong M, Ahn S, Choi YL, Kim KM, Oh D et al (2016) Changes in tumour expression of programmed death-ligand 1 after neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with squamous oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer 52:1–9. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, Hsu CH, Cheng JC, Wang HP, Lee JM, Yeh KH et al (2007) Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with twice weekly paclitaxel and cisplatin followed by esophagectomy for locally advanced esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol 18:93–98. 10.1093/annonc/mdl339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Wei S, Hurt EM, Green MD, Zhao L, Vatan L et al (2018) Host expression of PD-L1 determines efficacy of PD-L1 pathway blockade-mediated tumor regression. J Clin Invest 128:805–815. 10.1172/JCI96113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T, Ward JP, Gubin MM, Arthur CD, Lee SH, Hundal J et al (2017) Temporally distinct PD-L1 expression by tumor and host cells contributes to immune escape. Cancer Immunol Res 5:106–117. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppedijk V, van der Gaast A, van Lanschot JJ, van Hagen P, van Os R, van Rij CM et al (2014) Patterns of recurrence after surgery alone versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery in the CROSS trials. J Clin Oncol 32:385–391. 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2186 (Epub 2014 Jan 13) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Li Z, Xue W, Zhang M (2019) Predictive biomarkers for PD-1 and PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Immunotherapy 11:515–529. 10.2217/imt-2018-0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, Zheng P (2018) Tumor cells versus host immune cells: whose PD-L1 contributes to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade mediated cancer immunotherapy? Cell Biosci 8:34. 10.1186/s13578-018-0232-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Liang Y, Anders RA, Taube JM, Qiu X, Mulgaonkar A et al (2018) PD-L1 on host cells is essential for PD-L1 blockade-mediated tumor regression. J Clin Invest 128:580–588. 10.1172/JCI96061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi S, Saeki H, Nakashima Y, Ito S, Oki E, Morita M et al (2017) Programmed death-ligand 1 expression at tumor invasive front is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci 108:1119–1127. 10.1111/cas.13237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL et al (2012) Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 366:2074–2084. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liu F, Liu L (2017) Prognostic significance of PD-L1 in solid tumor: an updated meta-analysis. Medicine (baltimore) 96:e6369. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Pang Q, Zhang X, Yan C, Wang Q, Yang J et al (2017) Programmed death-ligand 1 is prognostic factor in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and is associated with epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Sci 108:590–597. 10.1111/cas.13197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Li C, Wu Y, Li B, Zhang B (2017) Prognostic value of PD-L1 expression in tumor infiltrating immune cells in cancers: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12:e0176822. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is available when requested.