Abstract

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are rapidly urbanizing, and in response to this, there is an expansion in the body of scholarship and significant policy interest in urban healthcare provision. The idea and the reality of ‘urban advantage’ have meant that health research in LMICs has disproportionately focused on health and healthcare provision in rural contexts and is yet to sufficiently engage with urban health as actively. We contend that this research and practice can benefit from a more explicit engagement with the rich conceptual understandings that have emerged in other disciplines around the urban condition. Our critical review included publications from four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Social Sciences Citation Index) and two Community Health Worker (CHW) resource hubs. We draw upon scholarship anchored in sociology to unpack the nature and features of the urban condition; we use these theoretical insights to critically review the literature on urban community health worker programs as a case to reflect on community health practice and urban health research in LMIC contexts. Through this analysis, we delineate key features of the urban, such as heterogeneity, secondary spaces and ties, size and density, visibility and anonymity, precarious work and living conditions, crime, and insecurity, and specifically the social location of the urban CHWs and present their implications for community health practice. We propose a conceptual framework for a distinct imagination of the urban to guide health research and practice in urban health and community health programs in the LMIC context. The framework will enable researchers and practitioners to better engage with what entails a ‘community’ and a ‘community health program’ in urban contexts.

Keywords: urban health, community health program, urban sociology, community health worker, community health

Key messages.

The concept of ‘urban advantage’ has led to a disproportionate research focus on rural health in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), while limiting deeper engagement with the rich conceptual insights into urban conditions and city life.

Urban community health research and practice can benefit from integrating conceptual understandings from the social sciences about the ‘urban condition’, enhancing the depth of analysis in community health worker (CHW) programs.

Designed for rural areas, CHW programs face challenges when adapted to urban contexts, highlighting the gaps and need for considering urban features like heterogeneity, secondary ties, size and density, precarity, and social location of the CHW.

By critically engaging with the urban condition through CHW program literature, a conceptual framework is proposed to guide future urban health research and policy in LMICs.

Introduction

The idea and the reality of ‘urban advantage’ have meant that health research in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has disproportionately focused on health and healthcare provision in rural contexts and is yet to sufficiently engage with urban health as actively (Ezeh et al. 2017, Shawar and Crane 2017, Gore 2019). The issue is not that there is no research on health in urban contexts—there is plenty of it. The issue rather, we contend, is that this research (and practice) does not sufficiently engage with the rich conceptual understandings that have emerged in other disciplines around the features of the city, the life in the city, and the urban condition generally—we also contend that health research and practice would greatly benefit from a more explicit engagement with these understandings. In this paper, we examine community health programs, specifically community health worker (CHW) programs, one major area of health research and practice in LMICs, to interrogate these contentions. We draw upon key scholarly works in the social sciences to unpack the nature of the city and the key features of the urban condition; we use these theoretical insights to critically review the literature on urban CHW programs and the role of urban CHWs in LMIC contexts. Using the CHW program literature as a case in point, we examine how the literature engages with the urban and reflect on the implications of different features of the urban condition on urban community health policy and practice. The choice of interrogating CHW programs is purposeful, as historically, community health programs broadly and CHW programs specifically in LMICs have been designed for and have been implemented in rural communities—it is only in the last decade or so that we see attempts to replicate them in urban contexts. The struggles and travails of CHW programs in LMICs as they migrate from their roots in the village to the city, we show, reveal the need for and the importance of a distinct understanding of the urban in how one approaches research and practice in urban health, including but not limited to CHW programs.

Through examining how the literature on CHW programs engages with the urban condition in LMIC contexts, we seek to flag the merits of a theoretically grounded understanding of the ‘urban’ within urban health programs and research. In the process, drawing on theoretical insights primarily from the sociology of the urban condition, we develop and propose a conceptual framework to guide health research and practice in urban LMIC contexts.

Materials and methods

Ludwick et al.’s (2020) recent scoping review that maps the evidence on urban CHW roles in LMICs across study designs, settings, and program types was the trigger and the starting point for this review; among others, it revealed the many similarities and differences in the way community health services are delivered and CHW roles conceptualized in urban and rural settings (Ludwick et al. 2020). To us, the struggles with the transplantation of rural models to urban contexts stuck out as a key takeaway from the scoping review. We replicated and updated (for 2021) the search strategy used by Ludwick et al. (2020) to identify additional relevant papers since the publication of this scoping review. While we follow the search strategy of Ludwick et al. (2020), we do not engage in assessing the size and scope of literature nor do we characterize the quantity and quality of literature as is the practice in a scoping review. A critical review evaluates the quality of the literature by going beyond the descriptive analysis and includes some degree of conceptual insight or innovation. In this paper, the critical review method is adopted to take stock of the existing literature on CHW programs and offer critical reflection and conceptual development (Grant and Booth 2009). Here, the term ‘critical review’ is used in a true adverbial sense, indicating ‘a critical review of the literature’ wherein conceptual and theoretical ideas are used to critique the underlying assumptions about organization of healthcare (Edgley, et al., 2016).

While the details of the search strategy can be found in Ludwick et al. (2020), we summarize the approach in brief here. The search included all peer-reviewed articles on CHW programs in urban settings in LMICs, irrespective of the study type. The search adopted a broad definition of CHW programs and CHW roles, including CHWs who deliver services as part of peer-based interventions. Given the diversity of terms used to refer to CHWs, we used the search terms used by Glenton et al.’s (2013) Cochrane Review and World Health Organization (WHO)’s recent review (Glenton et al. 2013, World Health Organization (WHO) 2018). We searched four databases—MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Web of Science (social science)—for peer-reviewed literature and two WHO resource hubs (CHW Central and Global Health Workforce Alliance) for additional publications. Of 876 articles, 180 met the inclusion criteria. Programs spanned 34 LMICs. We included all articles that self-described their settings using terms like urban, city, metropolitan, town, peri-urban, suburb, township, slum, informal settlement, or shantytown. We surveyed the sociological literature on the ‘urban’ and identified theorists and authors investigating the impact of urbanization on ‘communities’ and ‘community life’. We also looked at contemporary scholars in the global south theorizing the ‘urban’ and found that this important and developing understanding of the urban is underutilized in the CHW program literature. By collating the overlapping and consistent themes about the ‘urban condition’, we created a matrix of urban features, which was then used to systematically and critically investigate how the ‘urban’ is accounted for in the literature. The matrix was used as a coding framework (Supplementary File 1) to examine the papers included in the review and to map and record how these features have been accounted for in CHW programs and research. The paper (and the analysis) is divided into three main sections. Drawing on key conceptual writings from the social sciences, the ‘first section’ presents the important features of the urban condition and introduces what they might potentially mean for health service provision; a conceptual framework is proposed. In the second and third sections, guided by the conceptual insights introduced in the first section, we critically examine empirical studies (surveys, qualitative studies, randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, and evaluation studies) on CHW interventions in urban settings. Specifically, in the second section, in Table 1 (a detailed version of which can be found in Supplementary File 5), we present an overview of how the empirical literature on CHW programs from LMICs has engaged with the key features of the city that are introduced in the first section. In ‘the third section’, we discuss the overview presented in Table 1. We do so by reflecting on the importance of each urban feature by discussing the gaps in engagement in the health programs and drawing implications for the provision of community health services in the urban context.

Table 1.

Overview of how the empirical literature on CHW programs from LMICs engages with the key features of the urban condition.

| Key features of the urban condition | Papers Reviewed |

|---|---|

| Heterogeneity of the population | 14 |

| Size & Density | 9 |

| Visibility & Anonymity | 14 |

| Importance of Secondary ties | 35 |

| Importance of Secondary Spaces | 18 |

| Weak Primary Ties | 9 |

| Informal Housing | 13 |

| Informal Work Conditions | 20 |

| Crime & Insecurity | 7 |

| Community Health Workers’ social location in the city | 30 |

Our aim in this paper is to urge and encourage a critical reflection on the conventional understandings of the community, conventional templates of health and community program design, and the role of CHW workers in the urban context. Therefore, we do not assess the quality of the papers as is conventionally done in some reviews; we only critically examine the current empirical literature on CHW programs in LMICs based on key features of the urban condition.

Results

Section I

Towards an understanding of the ‘urban’ in urban healthcare provision

Sociologists have long theorized the urban condition and asked what happens when traditional ties of rural communities that provide security and cohesion are disrupted. How do people deal with the ‘social disorganization’ that comes with urbanization? And how do they form communities or bonds in the urban environment despite the forces of the urban economy? ‘Simmel, 1950’, in his book ‘Metropolis and Mental Life’, talks of the effects of the chaos and the fast pace of the city on the human psyche. Simmel, observing from his context in Germany, discusses how people in the city turn into impersonal, materialistic, and reserved personalities. He goes on to add that the money-based economy of the city, while freeing people from traditional restraints, reduces them to mere consumers (Simmel 1950, pp. 409–424). Wirth (1938) builds a similar argument explaining how the high density, large size, and heterogeneity of inhabitants in the city make it impossible for an individual to build meaningful bonds and interact as full personalities—thus producing what he terms as a ‘schizoid’ urbanite. These urbanites, although may know a larger number of people than their rural counterparts, interact with each other in segmented roles, and their relationships are secondary, impersonal, and superficial (Wirth 1938, pp. 1–24). The dense urban space allows greater interaction among a large number of heterogeneous inhabitants across race, class, caste, and ethnicity but also furthers the need to keep social contacts distant and puts a premium on visual recognition. By greater interaction, we do not intend to overestimate the equalizing effect of urban spaces and claim that various identity-based inequalities go away, nor do we intend to overestimate the cohesion and ignore the inequalities and power structures operating in rural areas. (Omvedt 1980, Jodhka 2002, Singh et al. 2019) Often these inequalities manifest in other unique ways in the urban context marginalizing certain groups; however, the urban offers, sometimes, forces and encourages greater interaction across groups compared to the small towns and rural counterparts. While over decades Wirth’s views have been both challenged and elaborated, there is recognition that, globally, the very size, density, and heterogeneity, which relatively frees people from traditional restraints, also underpins and contributes to urban social problems and challenges like crime, mental breakdowns, and other forms of psychological and social disorganization. These ideas also resonate with Ferdinand Tonnie’s idea of the fading of primary bonds of kinship and community life and the forming of secondary or formal bonds (1957), and Emile Durkheim’s concept of ‘anomie’ where the individuals are released from group ties and are left isolated and without a meaningful life (Tönnies 1957; Durkheim 1951). Putnam (1995), referring to urbanization in the USA, similarly notes that the urban is characterized by greater individualism, reductions in social capital and civic engagement, and a loss of generalized trust and reciprocity.

While there seems to be broad agreement among urban sociologists on the weakening of the primary ties in the city, many do not fully agree with this, sometimes, rather gloomy take. Other scholars have discussed how newer forms of associations and communities emerge in the city and how these help individuals integrate into the larger urban society. Viewing the city as an organism, Park (1915) argues that cities have local ‘natural’ areas like the central district, diverse residential areas, industrial areas, and slums, which provide a basis for shared identity and community. While the idea of these areas being ‘natural’ has been challenged revealing political forces discriminating against some groups through exclusionary city planning and ghettoization (Campanella 2010, Wacquant 2008), these areas do form their own sense of community and may have their own traditions and norms similar to villages (Boyd 2017). However, given the dynamic nature of the city, these communities develop occupational and other cultural interests and also move into nonspatial communities. He also argues the potential of nonspatial communities, formal organizations, or political institutions as community phenomena to integrate individuals and hold the city together. While Park agrees with Simmel on the segmented role of individuals in a city, he empathizes with the individual’s struggle to search for a community and emphasizes the need for scholarship to understand what neighbourliness and community mean in a large urban society.

Building on Park’s famous description of the city as a ‘mosaic of social worlds’ and reformulating Wirth’s urban features of size, density, and heterogeneity, Fischer (1976) argues that instead of destroying traditional communities and creating anomie, the size and density of the city create a critical mass which helps foster new subcultures and ways of living and communing. These local communities are heterogeneous and include diverse ethnic, immigrant neighbourhoods and occupation-based groups, which might coexist peacefully or even have conflicts, but nevertheless, the community exists in a modified form in the urban space (Fischer 1976). Fischer’s ideas echo the contributions of other theorists like Jacobs (1961) who also argues that the urban communities must not be analogized with rural communities that are relatively self-contained, homogeneous, and introverted. Jacobs highlights the importance of what she refers to as ‘hop-skip links’ in urban contexts—a situation wherein actors rooted in diverse communities form relationships and build networks. These ties and networks are similar to what Fischer (1976) calls new ‘ways of living and communing’—wherein the strength of these networks is often based on the sociopolitical importance of the actors creating these hop-skip links.

In her recent book, Tonkiss (2013) brings many of these features of the city together when she argues that ‘the major plotline in the big story of contemporary urbanization is one of informality’. She draws on and agrees with Roy (2009) in stating that ‘informality is not only “an idiom of urbanization”, but now its first language’. She contends that globally, the rapid urbanization of the last few decades has happened informally and in fact has been mediated by informality (Roy 2009, Tonkiss 2013). And that at local levels, policy practitioners tacitly and explicitly recognize that many aspects of urban life are ‘done off-the-books, without planning permission, in defiance or ignorance of regulations’. Another important aspect of informality is that much of what is informal is not formally visible including both informal structures and people working informally. This has clear implications for healthcare provision as it renders invisible particular people, places, and practices within the city, and it is in these invisibilities that the greatest vulnerabilities of the city or the urban lie. For example, while increase in informal and contractual labour has been observed in both urban and rural communities, the aspects of density and lack of habitable space, the presence of heterogeneous groups, their diverse needs and claims to the limited resources of the city, weak social ties, and the absence of social support and legal protections together produce a certain kind of invisibilization—‘precariousness’ that is specific to the urban (Strauss 2018, Campbell and Laheij 2021). Evidence suggests that density and size, coupled with such informal work conditions, foster precarious and poor-quality living arrangements wherein urban residents, especially the urban poor, lack access to basic services such as water, electricity, housing, education, and healthcare—all of which complicate the provision of healthcare in urban contexts.

The urban precariousness deepens inequalities as it intersects with other oppressive aspects of identities like gender, caste, class, and ethnicity, producing multiple vulnerabilities (Amarasuriya and Spencer 2015, Kunduri 2018). Moreover, the compound nature of precarity, i.e. the aggregation of lack of social support, legal protection, and informal, unstable work and living conditions, gives it a pervasive quality that reflects in everyday life and decision-making of the urban residents, producing experiences of disenfranchisement. While the effect of these conditions on city dwellers can produce conditions of ‘anomie’ as Durkheim explains or a ‘schizoid urbanite’ as Wirth put it, the common experiences of informality and precarity, as Bayat (1997, 2000) explains, also become the basis for forming of new identities, secondary ties, networks, and even forging new solidarities and political networks to demand resources and policy attention.

Moving away from Western-centric explanations of the city, Jennifer Robinson, in her work ‘A World of Cities’, further highlights the differences in cities of the West and cities rebuilding post-apartheid in South Africa (Robinson 2004). Scholars from Africa and the Global South point out key urban governance challenges, including managing a divided population amid pro-/anti-privatization conflicts, fostering participatory governance in diverse and transient communities, and ensuring equitable access to services in both formal and informal settlements and how the process of globalization ties these varied cities together (Amin and Thrift 2002, Beall et al. 2002). We delve deeper into the understanding of ‘Urban’ in the LMIC context in the next sub-section.

The ‘Urban’ in the LMIC Context

Urban sociology scholars who have studied urbanization in the LMICs context, while generally agreeing with the above features of the urban, nuance how the cities in the global north and global south are different owing to the distinct nature and rate of the urbanization process. This scholarship highlights how in many southern cities the rate of industrialization and economic development did not match the urban demographic growth, leading to not enough jobs, housing, and services (Bhan 2019, Lawhon and Le Roux 2019, Randolph and Storper 2023). This scholarship also alerts us to take a differentiated view of urban experience and highlights the analytical salience of taking into account structural differences like the history of colonization, late industrialization and neoliberal economic structures, and peripheral or dependent position in the world economy of the southern cities (Garrido et al. 2021). This ‘southern urban theory’ scholarship, as Bhan (2019) calls it, offers a nuanced and contextualized (to LMIC contexts) understanding of the analytical categories to examine the urban (e.g. heterogeneity, size and density, and precarity) in LMICs and is a useful starting point to interrogate the LMIC urban CHW program literature. That said, the characteristics of overcrowded, dense, and heterogeneous urban areas wherein people formed secondary ties and found some form of social capital (e.g. through unions, associations, and occupation-based neighbourhoods), in contrast to the traditional communal ties belonging to specific ethnic or religious groups, holds true for urban spaces globally (Kapur 2017). However, the nature of the density, the variety of heterogeneity, and the level and depth of precarity in terms of informal housing and work conditions may differ from Mumbai to Lagos to New York.

Given what we understand of the various features of the urban condition and the constraints to building a sense of community in an urban space, one would expect formal institutions, like the public health system, to be explicitly cognizant of these features. This should also be expected as the literature on urban health highlights a range of challenges like high mobility of urban dwellers (both inter-city movement and rural to urban migration), long working hours, precarious residences, particularly in informal settlements, insecurities, crime, violence, lack of social network to rely on, and also physically unsafe conditions like poor drainage, poor sanitation, and industrial pollution, which complicate the provision of health services and constrain CHWs from reaching the deserving populations (Ruel et al. 1999, van de Vijver et al. 2015, Shawar and Crane 2017). However, as Rydin et al. (2012) and Elsey et al. (2019) have argued, in the current urban health literature, in high-, middle-, and low-income country contexts alike, one continues to see insufficient engagement with these features of the urban.

This disregard is perhaps the most obvious in community health initiatives, where the idea of ‘community’ remains somehow rooted in its rural origins. And while there are exceptions, most ‘community health worker programs’ are modelled with rural social structures in mind. We briefly develop and illustrate this point. In LMIC contexts, CHW programs serve as a bridge between rural communities and the health system; CHWs belong to the community, either by geography or by identity and usually a combination of both, and draw on the aspects of familiarity, trust, and accessibility to fulfil their roles. In areas where health facilities, whether private or public, are not easily available, CHWs also provide care and play an important role in addressing the issue of geographical accessibility. However, in cities, the availability of numerous healthcare providers solves this problem of geographical access, rendering the CHW’s role rather ambivalent. Unlike in the village, CHWs in urban areas cannot make themselves easily visible, familiar, and relatable in the dense, dynamic, and constantly evolving urban context.

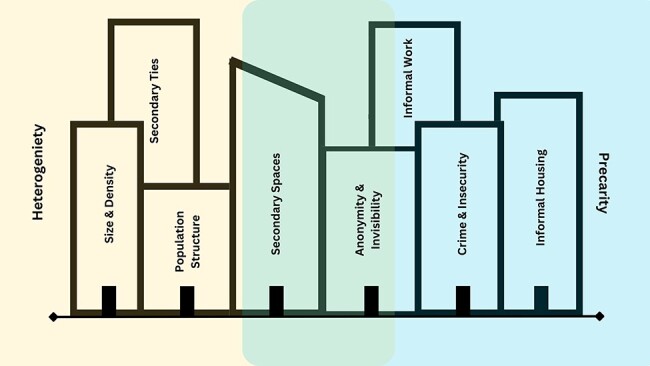

Figure 1 reflects the above discussion—it brings together the key conceptual understandings about the features of the city and the urban condition in the form of a conceptual framework. The figure highlights key urban features, including heterogeneity, size and density, population structure, secondary ties and spaces, anonymity and invisibility, informal work and housing, crime, insecurity, and precarity. Of these, heterogeneity and precarity emerge as overarching and multifaceted dimensions that influence and, in some cases, subsume the others. Secondary spaces and anonymity and invisibility lie at the intersection of these two complex dimensions, as they foster informal networks while simultaneously rendering individuals and their concerns invisible in the crowded, chaotic landscape of urban life. Together, these features form the foundation for understanding the intricate dynamics shaping community health services in urban contexts. Using this new framework, we interrogate the current literature on CHW programs in urban contexts to illuminate various aspects of the framework, and in doing so, we elaborate and develop it. Towards the end, we also present a more applied and practical version of the framework.

Figure 1.

A framework for analysing community health services in urban contexts.

Drawing from the above theoretical insights, and with a view to better understand urban health and urban community healthcare provision, some of the critical questions one could ask, including the current literature on CHW programs in urban LMIC contexts, would be: What kind of communities do CHW programs imagine and how do they identify them? Using Park’s words, does the health system consider this ‘mosaic of social worlds’ while planning for urban health and urban community healthcare provision? Do the roles and tasks of CHWs consider the heterogeneous population of the cities? How should the size, density, and heterogeneity of the population change the way CHWs work, and the way community health programs are organized? Might insights on community subcultures, nonspatial communities, and more generally the whole ‘mosaic of social worlds’ be useful in reimagining urban healthcare provision and urban community health work?

Next, in Section II, we ask these questions of the empirical literature on CHW programs from LMICs. In Table 1, we present an overview of how the empirical literature on CHW programs from LMICs engages with the key features of the city introduced in the first section (synthesized as a conceptual framework in Figure 1 and later in Figure 2).

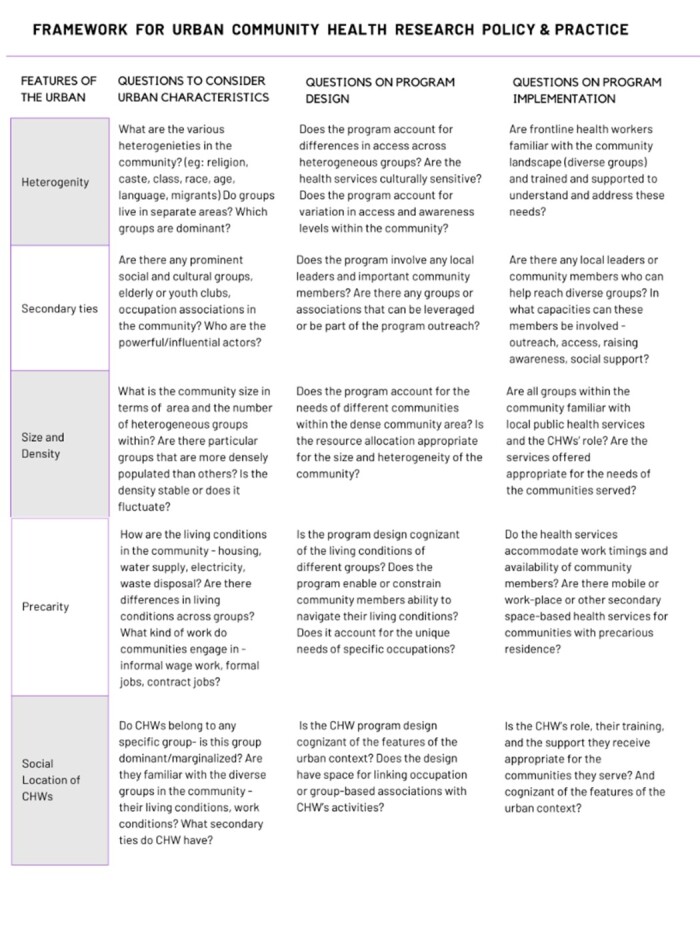

Figure 2.

Framework for Urban Community Health Research Policy and Practice

Section II

How the empirical literature on CHW programs from LMICs engages with the urban condition

Table 1 presents the matrix of urban features used to examine individual papers and an overview of which features are accounted for in the literature. Of the sample of 110 papers, 57 did not account for any of the urban features listed below, and the other 53 papers accounted for one or more urban features. Table 1 shows how many papers accounted for each urban feature (see Supplementary File 5 for a detailed presentation of all papers individually).

Table 1 provides an overview of the extent to which the urban condition is accounted for in the literature on urban community health programs in LMICs. The detailed presentation of this table (Supplementary File 5) arranges papers showing which features are accounted for in the order of least accounted for to most accounted for. Among the features of the urban condition, we see that heterogeneity, crime, and insecurity are the least accounted for, and secondary networks and social locations of CHWs are among the most acknowledged in the literature.

Discussion

Section III

In this section, we engage with each feature of the urban condition and analyse how it is accounted for in the literature on urban community health programs in LMICs. For each feature, ‘the first part’ we draws on Section I to discuss how the feature is considered in urban community health programs in LMICs. The second ‘part’ reflects on the implications of the feature for community health work and healthcare provision broadly in urban contexts, primarily in LMICs, but also generally. For ease of analysis and due to their overlapping characteristics, we have clubbed some of the features—like informal housing and working conditions and crime and insecurity together in one section on precarity, the features of importance of secondary ties, spaces, and weak primary ties in one section, and have subsumed visibility and anonymity in the size and density section.

Heterogeneities in the city

How do urban CHW programs engage with these heterogeneities?

In the few papers that acknowledged and accounted for heterogeneity, the urban CHW programs involved targeting specific populations and engagements with diverse stakeholders like local politicians, administrators, community, and religious leaders in designing and provision of health services (Benzaken et al. 2007, Odhiambo et al. 2016). Due to the increased utility of secondary ties in the urban context, which involves heterogeneous stakeholders, we see overlaps between the ‘importance of secondary ties’ and ‘heterogeneity’ elements in this review. Some health programs acknowledged heterogeneity by identifying and targeting specific groups within broader groups like men of different ethnic identities within the MSM (men having sex with men) community or married men left out by HIV programs targeting MSM (Tucker et al. 2013, Parry et al. 2017). However, these heterogeneities were identified to target and address specific vulnerabilities rather than recognizing them within broader population-level programs.

For instance, the vast majority of urban CHW interventions in the current literature treat the urban communities and urban poor as a monolithic entity or acknowledge heterogeneity in populations nominally without substantive consideration within the program design (Mash et al. 2012, 2015, Bryant et al. 2017, Gebreegziabher et al. 2017, Wijesuriya et al. 2017). Some even implemented one-size-fits-all interventions across rural, urban, and even nomadic communities, further highlighting blindness towards the heterogeneous nature of the urban (Khan et al. 2002, Ardalan et al. 2013, Olayo et al. 2014, Druetz et al. 2015, Tilahun et al. 2017). The few CHW programs that took into account heterogeneities substantively at the population level did so in a variety of ways—most commonly, this involved recognizing the varied socioeconomic conditions and specific vulnerabilities faced by some groups. For example, the CHW program that Salud et al. (2009) report on explicitly considered the varied knowledge levels among breastfeeding women, their economic conditions, and other important illnesses among them to enable effective outreach and increased breastfeeding outcomes. Similarly, Irwin et al. (2006) discuss how the CHW program on drug abuse recognized the varied economic conditions, diverse identities, and multiple degrees of stigma among drug users; it further provided services based on their location and time constraints—thus enabling and ensuring the inclusion of diverse groups within the larger group of injection drug users. Moreover, these programs recruited CHWs who had experience of breastfeeding or were previous drug users, thus leveraging relevant identities to broaden their community outreach (Irwin et al. 2006, Salud et al. 2009).

What are the implications of this heterogeneity for healthcare provision generally and CHW programs specifically?

Health is socially determined and shaped by historical, physiological, social, cultural, and economic differences. The city has multiple small and large relatively homogenous groups of people (Park’s ‘mosaic’) living alongside each other—making it difficult to attribute particular characteristics to urban communities. The urban community members, both in general and within the homogenous sub-communities, vary—ranging from established residents to new migrants and to groups who regularly return to their rural hometowns. In an urban space, these differences are complicated by the various heterogeneities that typify the urban—we argue that the inequities that these differences engender are potentially amplified by the informality of work and residence and by the lack of neat geographic boundaries in urban communities. The argument can be reasonably extended to say that an explicit accounting (or not) for heterogeneity within urban health programs has far greater equity-related implications than in similar rural programs. We contend that in urban contexts, health policies and programs need to explicitly zoom in to recognize and address the needs of diverse groups and zoom out to contextualize their relative position in the larger heterogeneous urban community. For urban health and community health programs to adapt and be equitably responsive to the needs and expectations of all city dwellers, it is important to understand that the unique circumstances of different groups, their particular economic activities, their network patterns, and the social institutions they access are part of and considered important.

Having said that, it is important to interrogate what it practically means for a health program to account for heterogeneities. For example, the unpacking of heterogeneities has clear but rather challenging implications for the selection and recruitment of CHWs. The conventional traits of familiarity, belonging, and accessibility associated with CHWs in rural communities should be differently assessed, given the heterogeneities and multiple identities acquired and embodied by individuals and groups in the city. While the literature indicates the use of certain secondary ties as criteria for selecting CHWs for specific population groups in cities, the utility of such ties in selecting CHWs to serve the vast heterogeneous urban population may not be as straightforward. We develop this example further in the following sections.

Importance of secondary ties and spaces and weak primary ties

Do urban CHW programs recognize and engage with the diversities in social ties that typify life in the city?

Many studies in Table 1 show that secondary ties and networks like interest groups, voluntary associations, and school and university space-based ties are sometimes leveraged by urban CHW programs to reach particular communities and to provide certain services. For instance, identities like previous illness survivors, well-liked opinion leaders, and interest group volunteers can be leveraged to strengthen CHWs’ access and accessibility and, in the process, foreground their position in the community (Haider et al. 2000, Duan et al. 2013, Morojele et al. 2014).

This recognition that primary ties are sometimes less important in urban settings and that interventions intervening via primary ties exclusively are less likely to be effective is important. However, the literature shows that similar to the recognition of heterogeneities, the recognition of what secondary ties mean for policy and program choices is rather limited to contexts that involve stigma or where the centrality of secondary ties is inherent to the health condition being targeted. To specify, secondary ties are central to the epidemiology of conditions like HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and injection drug use—and therefore targeted health interventions prefer CHWs from and intervene within these secondary networks like voluntary interest groups or support groups, allowing easy communication and mobilization (Welsh et al. 2001, Shetty et al. 2005, Benzaken et al. 2007, Sandøy et al. 2012, Duan et al. 2013, Morojele et al. 2014, Kabir et al. 2015, Hugo et al. 2018). However, CHW programs directed at the general urban population or broad-based conditions like maternal health, child health, or nutrition, did not recognize the salience of secondary ties (Refer to Supplementary File 5).

As Bayat (1997, 2000) has argued, despite the urban being a contested space, the impetus for city dwellers to forge secondary ties enables them to exert influence, lobby, and provide solidarity, social security, political influence, and opportunities for social reinvention. While some secondary ties and networks are straightforward, ties and networks like neighbourhood tea party networks of women, informal networks of small traders, networks of sex workers and bar owners, and multi-locale injection drug-user networks are some examples of complex secondary networks (Irwin et al. 2006, Gozum et al. 2010, Morojele et al. 2014). Literature suggests that while many of these networks and ties are loose, they have the potential to be mobilized and can be very strong.

What are the implications of strong secondary ties and networks in urban spaces for healthcare provision generally and CHW programs specifically?

The centrality of secondary networks and ties in urban contexts points to the importance of accounting for these ties in urban CHW programs—not merely in the hiring and selection of CHWs but also in developing strategies to ensure the performance and influence of CHWs. Secondary ties and networks are both created and characterized by heterogeneous groups that exist within urban communities; they also often inform health conditions and epidemiologies. It follows that, as noted in the previous section, community health programs that are cognizant of secondary ties can better address urban heterogeneities, thereby addressing the health inequities therewith. Leveraging secondary identities can also potentially enable CHW programs to create some sense of familiarity and relatability beyond geographical belonging—something that many of the papers we reviewed tacitly or explicitly recognized as difficult to achieve in urban settings. Our contention is that CHW programs in urban contexts need to reimagine themselves in such a way that they explicitly consider (in design, strategies, and implementation) secondary networks and ties. This contention echoes Jacobs’s (1961) view that urban communities are best understood within a network frame rather than in a geospatial frame. However, as alluded to in the previous section, such a reimagination is likely to be challenging, as it would require substantial changes to how CHW programs have traditionally defined and understood the communities they serve.

Recognizing the sheer varieties of heterogeneities and the vast range of secondary ties that exist and typify the city also raises important questions about which secondary institutions and ties matter, which secondary ties are more likely to invoke trust and familiarity, and (if and) how this might vary across health conditions and the different urban populations being targeted. We found that all CHW programs included in the review struggled to transplant the tenets of community health work conventionally developed within and attuned to rural contexts to urban contexts. A major part of these struggles seemed to be around secondary ties and networks (what they are, how they operate, and which of those matter) and how to adapt and engage with them. We contend that this effort, demanding as it may be at times, is worthwhile and that this step is essential.

Size and density of the city

How do urban CHW programs engage with the size and density aspects of the city?

Literature shows that the few papers that acknowledged and accounted for the size- and density-related features did so by recognizing the role of density in the increasing need for health services, the linked spatial and infrastructural limitations that affect healthy living, and, to some extent, the invisibilization that they portend for certain vulnerable groups. These issues were addressed (the literature reveals) by providing more or targeted services and by using secondary networks to visibilize and empower communities (Benzaken et al. 2007, Odendaal et al. 2009, Morojele et al. 2014). Most of the CHW programs struggled to address the large size and density of the city, and even though some attempts were observed that involved secondary networks, self-help groups, and provision of uniforms to increase the visibility of CHWs in dense locations, they ended up addressing the aspects of heterogeneity and secondary ties more, and not so much issues of density and size or the linked issues of informal living conditions in the communities they served (Akweongo et al, 2011, Kabir et al. 2015, Odhiambo et al. 2016, Tomlinson et al. 2016). We found that the CHW programs tend to miss out on the interconnected consequences of size, density, and heterogeneity elements and the secondary networks that they foster as these features have different effects on communities living in precarious conditions and on communities living in comparatively assured living conditions.

What are the implications of size and density for healthcare provision generally and CHW programs specifically?

The large size and density of the city have obvious and direct implications for the volume and nature of health services and health personnel required to ensure the health of all the inhabitants. Size and density are inextricably intertwined with the various heterogeneities outlined in Section I, and due to this, the familiarity-based recognition that rural folk can rely on does not hold in the city—city folk tend to rely much more on other forms of identification and recognition (e.g. uniforms, identity cards, and other such signifiers). This lack of natural familiarity and visibility makes it difficult for individuals to stand out, and in contexts of certain vulnerable populations, this results in the sidelining of their needs.

While the density of the city generally solves the problem of (lack of) proximity and geographical access to health services, its demerits lie in the congregation of large heterogeneous populations with a vast variety of health problems and heterogenous needs in a (relatively) small space and in invisibilizing the needs of certain vulnerable groups. Therefore, we argue that for health and CHW programs to be able to address size and density, they must consider size and density not only in terms of their obvious consequence for the volume and scale of health services to be provided but also in how they interact with other features of the city like the many heterogeneities, the nature of social ties, and, as we discuss next, also precariousness. We contend that program designs and implementation approaches also need to be particularly vigilant about the invisibilizing effects of size, density, and heterogeneities—and to systematically incorporate mitigating strategies in the design and implementation of urban health and community health services.

Precarity

How do urban CHW programs engage with precarity?

In our review, the few papers (Table 1) that acknowledged and accounted for precarity did so by conducting preintervention surveys, mapping areas of informal housing, involving permanent and migrating residents, designing time-sensitive CHW service provision, and taking cognizance of the socioeconomic conditions of the community in its program design (Mathews et al. 1991, Haider et al. 2000, Odendaal et al. 2009, le Roux et al. 2013, Yan et al. 2014, Mathias et al. 2021). However, the majority of the papers included in the review merely acknowledged the aspects of urban precarity in their introduction for the purpose of justifying the intervention in an urban space or discussed effects of urban precarity on health outcomes as findings or in their recommendations, without engaging with them within the program design and service delivery (Shetty et al. 2005, Goudet et al. 2011, Raj et al. 2013, Druetz et al. 2015, Ijumba et al. 2015, Jolly et al. 2016, Gebreegziabher et al. 2017). We found that all CHW programs struggled to outreach to and target vulnerable populations, as their community members engaged in long and unpredictable work hours, which did not suit the conventional work timings of CHWs. Moreover, conditions like temporary housing, frequent migration, and lack of permanent (phone) contact numbers rendered the previously beneficial idea of having CHWs from the same geographical area to evoke belonging and address proximity futile. Even when CHW programs, especially those involving counselling and home visits, managed to reach communities, both the CHWs and the people they served found the activities to be too time-consuming and inconvenient, rendering such program activities rather ineffective as communities were unwilling to devote much time (Cooper et al. 2009, Mash et al. 2012, 2015, Olayo et al. 2014, Balcazar et al. 2015, He et al. 2017, Powell and Grantham-McGregor 2017, Hugo et al. 2018).

One observation specific to intervention studies involving randomized control trials (RCTs) stood out within the empirical literature reviewed here. In such studies, the aspects of urban precarity like unequal income levels, availability of health services, and housing facilities were used as parameters to achieve equivalence between the intervention and control groups; they were, however, not accounted for in the intervention design (Cooper et al. 2009, Ardalan et al. 2013, Jolly et al. 2016, Powell and Grantham-McGregor 2017). As urban informalities and precarity are systemic conditions that can be altered only in the long term, they were expectedly treated as ‘ceteris paribus’ in such intervention studies involving CHW programs.

What are the implications of different aspects of precarity for healthcare provision generally and CHW programs specifically?

The effects of precarious work and living conditions are varied, systemic, and long-lasting on the health of urban communities. Unlike the previously discussed elements of heterogeneity and secondary networks, urban precarity does not lend itself to be wielded in innovative ways as we see in the case of the selection of CHWs from and intervening within heterogeneous and secondary networks. Therefore, we contend that urban precarity needs to be understood both as a standalone phenomenon and also in its effect on the features of the urban condition, as it is highly pervasive and can be misunderstood as community behaviour rather than as a structural constraint faced by urban communities. Having said that, the systemic and compound nature of urban precarity also makes it extremely difficult to address through the CHW programs, as that would require stronger political and administrative efforts. However, we argue that by understanding the precarious conditions of the city, CHW programs can better identify what communities consider as immediate and long-term needs, if certain health conditions are caused by health behaviours or by lack of certain facilities, and how the role of CHWs can be attuned to the systemic precarity faced by urban communities. For example, Odendaal et al. (2009) report on a home visitation program for unintentional childhood injuries, wherein the program accounted for poor housing, water, and electric facilities that created accident-prone conditions like the use of paraffin oil to substitute electricity, firewood for gas, and the use of easily flammable curtains and cardboard as room dividers as houses were very small. The program supplied safety devices to replace these materials and created educational materials for children and messages for caregivers that were portioned in multiple time-sensitive home visits. In this example, which was an RCT, urban precarity was recognized and designed into the CHW program, unlike the mere (nominal) acknowledgement that we found throughout the urban CHW program literature.

To be able to account for urban precarity meaningfully, we argue that health and community health programs need to recognize and engage with the complex and intersecting structural features of the urban condition that create unique, often very local, segmented, and unpredictable vulnerabilities among the many heterogeneous communities that typify the city. Crucially, we contend that the first step is perhaps to unlearn the conventional ways presently modelled after rural communities and to understand what entails a ‘community’ and what then entails a ‘community health program’ in an urban context.

Social location of the CHW in a city

How do urban CHW programs engage with the social location of the CHWs?

Literature suggests that the programs or intervention studies that accounted for the social location of CHWs did so by recruiting them within various secondary networks, leveraging on identities like previous illness survivors, community leaders, and interest group volunteers, by ensuring proximity of CHWs and by providing uniforms to address lack of visibility (Akweongo et al. 2011, Haider et al. 2000, Benzaken et al. 2007, Everett-Murphy et al. 2010, Gozum et al. 2010, Duan et al. 2013, Coetzee et al. 2017, Hugo et al. 2018). However, most CHW programs grappled with selecting appropriate CHWs for the vast heterogeneous populations they encountered, with the lack of CHW familiarity and poor community participation, and with the presence of various other private health service providers competing with CHWs.

The struggle with heterogeneous populations can be observed in the vast range of CHWs one encounters in the literature reviewed—ranging from paid and unpaid health volunteers, incentive-based or honorarium-based peer counsellors with previous illness experiences, peer educators trained for specific health problems, and more formal CHWs trained in community health practice. In some cases, the aspects of heterogeneity and secondary networks were accounted for in selecting CHWs, but in most instances, the economic condition of CHWs, the time constraints faced by CHWs, and community perceptions and beliefs about CHWs were not sufficiently accounted for. With few exceptions, CHWs were low or unpaid, nominally trained, and their work hours mismatched with the odd working hours of the communities targeted as part of the CHW programs (Welsh et al. 2001, Ijumba et al. 2015, Mash et al. 2015, Bryant et al. 2017, Mbachu et al. 2017, Wijesuriya et al. 2017, Hugo et al. 2018, Mary Kapanee et al. 2018).

What are the implications of the social location of CHWs in an urban space for CHW programs?

The aspects of the city, including heterogeneity, importance of primary ties, size and density, and urban precariousness have a bearing not only on the conventional ‘community—CHW’ relationship but also on CHWs as individuals grappling with similar urban conditions. Given the complex nature of the city, we argue that equal attention needs to be given to the effects of the urban condition both on the specific communities targeted within CHW programs and the CHWs themselves who embody these urban complexities. While the literature reviewed highlights some efforts in terms of recruiting CHWs from secondary networks and coming up with different versions of CHWs to suit specific communities, it was observed that in many cases, the social location of CHWs was not accounted for as they were poorly compensated or even unpaid, inadequately trained to tackle diversity in the community, were working in insecure neighbourhoods without formal protections, and were offering identical health services as other CHWs working in the same vicinity.

At another level, the various features of the urban condition outlined in earlier sections are also at odds with the conventional (rural CHW program-based) rationale that CHWs rely on trust, specifically familiarity-based trust, to relate to and engage with the communities they serve.

The rural context-oriented CHW literature has consistently emphasized this centrality of trust to the effective functioning and performance of CHWs. However, in the absence of familiarity as the basis for fostering ‘trust’ in urban contexts, what alternative basis could CHWs draw from to foster trust, needs to be understood and then reflected in the design, and implementation of CHW programs in the city.

We contend that the lack of social cohesion, weak primary bonds, informal work and living conditions, and insecurity characterizing the urban communities also inform the lives of urban CHWs and may affect their ability to understand and perform their roles within CHW programs. On this account, we argue that urban CHW programs need to recognize the social location of the CHWs, rooted as it is, in the heterogeneity, density, informality insecurity, anonymity, and the secondary identities that characterize the city. In other words, programs need to appreciate that CHWs in a city, like all city dwellers, embody the complexities of the city, and therefore, the role of urban CHWs requires reimagination accordingly—in terms of their profile, selection, training, remuneration, and rewards. Urban health programs need to develop CHW roles such that city-specific ways of belonging, familiarity, and trust are fostered.

Conclusions: A way forward

In conclusion, through a critical interrogation of the literature on community health programs in urban LMIC contexts, we have highlighted the need for and importance of reimagining urban healthcare provision and urban community health work such that it explicitly relates to and engages with the many unique features of the city. In doing so and extensively drawing upon the rich theoretical insights from the social sciences, in Figure 2, we have proposed an analytical framework that can serve as a guide for those involved in organizing and researching health and community health services in urban contexts. In presenting these urban features and their possible implications, we are cognizant of how they might vary depending on the training, support for CHWs, and demography of the urban area. In Section I, Figure 1 offers a generic presentation of the urban features and a framework for analysing community health services in urban contexts. Figure 2 builds and elaborates on Figure 1 and translates it into a practical guide for health researchers and policymakers working on urban CHW programs and, more broadly, on close-to-community health services in urban contexts in LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sanjana Santosh, Nossal Institute For Global Health, Melbourne School Of Population And Global Health, Level 2, 32 Lincoln Square North, The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia; Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, BMCC Road, Pune 411004, India.

Sumit Kane, Nossal Institute For Global Health, Melbourne School Of Population And Global Health, Level 2, 32 Lincoln Square North, The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia; Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, BMCC Road, Pune 411004, India.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Health Policy and Planning online.

Author contributions

Sumit Kane (Conception and design), Sanjana Santosh (Data collection), Sanjana Santosh, Sumit Kane (Data interpretation), Sanjana Santosh, Sumit Kane (Drafting of the article), Sumit Kane, Sanjana Santosh (Critical revision of the article)

Reflexivity statement

The authors include one senior researcher and one early career researcher. While the senior researcher conceptualized the study, as the Author contributions section articulates, this work is a joint endeavour. The idea of and the need for this critical review emerged from the two researcher’s ongoing involvement in research on close-to-community health services, including in urban contexts, and from the recognition that there was much to learn from how the social sciences have understood and studied the ‘city’ and the ‘urban condition’.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required for this study.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

- Akweongo P, Agyei-Baffour P, Sudhakar M et al. Feasibility and acceptability of ACT for the community case management of malaria in urban settings in five African sites. Malaria J 2011;10:240. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasuriya H, Spencer J. “With that, discipline will also come to them”: the politics of the urban poor in Postwar Colombo. Curr Anthropol 2015;56:S66–75. doi: 10.1086/681926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin A, Thrift N. Cities: Reimagining the Urban. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ardalan A, Mowafi H, Ardakani HM et al. Effectiveness of a primary health care program on urban and rural community disaster preparedness, Islamic Republic of Iran: a community intervention trial. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013;7:481–90. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Fernandez-Gaxiola AC, Perez-Lizaur AB et al. Improving heart healthy lifestyles among participants in a Salud para su Corazón promotores model: the Mexican pilot study, 2009-2012. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:14029. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat A. Un-civil society: the politics of the “informal people”. Third World Q 1997;18:53–72. doi: 10.1080/01436599715055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat A. From “dangerous classes” to “quiet rebels”: politics of the urban subaltern in the global South. Int Sociol 2000;15:533–57. doi: 10.1177/026858000015003005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beall J, Crankshaw O, Parnell S. Uniting a Divided City: Governance and Social Exclusion in Johannesburg. London: Earthscan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaken AS, Garcia EG, Sardinha JCG et al. Community-based intervention to control STD/AIDS in the Amazon region, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2007;41:118–26. doi: 10.1590/s003489102007000900018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhan G. Notes on a Southern urban practice. Environ Urban 2019;31:639–54. doi: 10.1177/0956247818815792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RL. Urban locations and Black Metropolis resilience in the Great Depression. Geoforum 2017;84:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Schafer A, Dawson KS et al. Effectiveness of a brief behavioural intervention on psychological distress among women with a history of gender-based violence in urban Kenya: a randomised clinical trial. PLoS Med 2017;4:e1002371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella R. Delta Urbanism: New Orleans 1st edn. New Orleans: Routledge, 2010. doi: 10.4324/9781351179737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell B, Laheij C. Introduction: urban precarity. City Soc 2021;33:283–302. doi: 10.1111/ciso.12402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee B, Kohrman H, Tomlinson M et al. Community health workers’ experiences of using video teaching tools during home visits—a pilot study. Health Soc Care Comm 2017;26:167–75. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L et al. Improving quality of mother-infant relationship and infant attachment in socio-economically deprived community in South Africa: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druetz T, Ridde V, Kouanda S et al. Utilization of community health workers for malaria treatment: results from a three-year panel study in the districts of Kaya and Zorgho, Burkina Faso. Malaria J 2015;14:71. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0591-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Zhang H, Wang J et al. Community-based peer intervention to reduce HIV risk among men who have sex with men in Sichuan province, China. AIDS Educ Prev 2013;25:38–48. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim É. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York: The Free Press, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Edgley A, Stickley T, Timmons S et al. Critical realist review: exploring the real, beyond the empirical Journal of Further and Higher Education 2016;40:316–330. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2014.953458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsey H, Agyepong I, Huque R et al. Rethinking health systems in the context of urbanisation: challenges from four rapidly urbanising low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health 2019;4:e001501. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett-Murphy K, Steyn K, Mathews C et al. The effectiveness of adapted, best practice guidelines for smoking cessation counselling with disadvantaged, pregnant smokers attending public sector antenatal clinics in Cape Town, South Africa. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:478–89. doi: 10.3109/00016341003605701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh A, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D et al. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet 2017;389:547–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31650-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C. The Urban Experience. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido M, Ren X, Weinstein L. Toward a global urban sociology: keywords. City Comm 2021;20:4–12. doi: 10.1111/cico.12502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gebreegziabher EA, Astawesegn FH, Anjulo AA et al. Urban health extension services utilization in Bishoftu Town, Oromia Regional State, Central Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:195. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2129-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;10:CD010414. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010414.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore R. National and subnational politics of health systems’ origins and change. In: Parker R, Garcia J (eds), Routledge Handbook on the Politics of Global Health. London: Routledge, 2019, 122–31. [Google Scholar]

- Goudet SM, Faiz S, Bogin BA et al. Pregnant women’s and community health workers’ perceptions of root causes of malnutrition among infants and young children in the slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1225–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozum S, Karayurt O, Kav S et al. Effectiveness of peer education for breast cancer screening and health beliefs in Eastern Turkey. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:213–20. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181cb40a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider R, Ashworth A, Kabir I et al. Effect of community-based peer counsellors on exclusive breastfeeding practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;356:1643–47. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03159-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Irazola V, Mills KT et al. Effect of a community health worker-led multicomponent intervention on blood pressure control in low-income patients in Argentina: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:1016–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo JM, Rebe KB, Tsouroullis E et al. Anova Health Institute’s harm reduction initiatives for people who use drugs. Sex Health 2018;15:176–78. doi: 10.1071/SH17158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijumba P, Doherty T, Jackson D et al. Effect of an integrated community-based package for maternal and newborn care on feeding patterns during the first 12 weeks of life: a cluster-randomized trial in a South African township. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:2660–68. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015000099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin K, Karchevsky E, Heimer R et al. Secondary syringe exchange as a model for HIV prevention programs in the Russian Federation. Subst Use Misuse 2006;41:979–99. doi: 10.1080/10826080600667219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Jodhka S. Nation and village: images of Rural India in Gandhi, Nehru and Ambedkar. Economic & Political Weekly 2002;37:3343–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly SP, Rahman M, Afsana K et al. Evaluation of maternal health service indicators in urban slums of Bangladesh. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir H, Saha NC, Gazi R. Female unmarried adolescents’ knowledge on selected reproductive health issues in two low performing areas of Bangladesh: an evaluation study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2597-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur D. How will India’s urban future affect social identities? Urbanisation 2017;2:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2455747117700950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Walley JD, Witter SN et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of different DOT strategies for the treatment of tuberculosis in Pakistan. Health Policy Plann 2002;17:178–86. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.2.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunduri E. Between Khet (field) and factory, Gaanv (village) and Sheher (city): caste, gender and the (re)shaping of migrant identities in urban India. South Asia Multidiscip Acad J 2018;19. doi: 10.4000/samaj.4582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhon M, Le Roux L. Southern urbanism or a world of cities? Modes of enacting a more global urban geography in textbooks, teaching and research. Urban Geogr 2019;40:1251–69. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1575153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM et al. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant mothers and their infants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS 2013;27:1461–71. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283601b53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwick T, Morgan A, Kane S et al. The distinctive roles of urban community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of the literature. Health Policy Plann 2020;35:1039–52. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary Kapanee AR, Meena KS, Nattala P et al. Perceptions of accredited social health activists on depression: a qualitative study from Karnataka, India. Indian J Psychol Med 2018;40:11–16. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_114_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash B, Levitt N, Steyn K et al. Effectiveness of a group diabetes education programme in underserved communities in South Africa: pragmatic cluster randomized control trial. BMC Family Prac 2012;13:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash R, Kroukamp R, Gaziano T et al. Cost-effectiveness of a diabetes group education program delivered by health promoters with a guiding style in underserved communities in Cape Town, South Africa. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:622–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C, Vanderwalt H, Hewitson DW et al. Evaluation of a peri-urban community health worker project in the Western Cape. South Afr Med J 1991;79:504–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias K, Corcoran D, Pillai P et al. The effectiveness of a multi-pronged psycho-social intervention among people with mental health and epilepsy problems—a pre-post prospective cohort study set in North India. Int J Health Policy Manag 2021;10:546–53. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbachu C, Dim C, Ezeoke U. Effects of peer health education on perception and practice of screening for cervical cancer among urban residential women in south-east Nigeria: a before and after study. BMC Women’s Health 2017;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0399-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Kitleli N, Ngako K et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a bar-based sexual risk reduction intervention for bar patrons in Tshwane, South Africa. Sahara J Soc Asp 2014;11:1–9. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2014.890123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odendaal W, Van Niekerk A, Jordaan E et al. The impact of a home visitation programme on household hazards associated with unintentional childhood injuries: A randomised controlled trial. Accid Anal Prev 2009;41:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo GO, Musuva RM, Odiere MR et al. Experiences and perspectives of community health workers from implementing treatment for schistosomiasis using the community directed intervention strategy in an informal settlement in Kisumu City, western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2016;16:986. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3662-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayo R, Wafula C, Aseyo E et al. A quasi-experimental assessment of the effectiveness of the Community Health Strategy on health outcomes in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:S3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-S1-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omvedt G. Caste, agrarian relations and agrarian conflicts. Sociol Bull 1980;29:142–70. doi: 10.1177/0038022919800202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park R. The city: suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the urban environment. Am J Soc 1915;20:577–612. doi: 10.1086/212433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH, Carney T, Williams PP. Reducing substance use and risky sexual behaviour among drug users in Durban, South Africa: assessing the impact of community-level risk-reduction interventions. Sahara J Soc Asp 2017;14:110–17. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2017.1381640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell C, Grantham-McGregor S. Home visiting of varying frequency and child development. Pediatrics 2017;84:157–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.84.1.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J Democracy 1995;6:65–78. doi: 10.1353/jod.1995.0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raj S, Goel S, Sharma VL et al. Short-term impact of oral hygiene training package to Anganwadi workers on improving oral hygiene of preschool children in North Indian City. BMC Oral Health 2013;13:67. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-13-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph GF, Storper M. Is urbanisation in the Global South fundamentally different? Comparative global urban analysis for the twenty-first century. Urban Stud 2023;60:3–25. doi: 10.1177/00420980211067926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. A world of cities. Br J Sociol 2004;55:569–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00038.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. Strangely familiar: planning and the worlds of insurgence and informality. Plan Theory 2009;8:7–11. doi: 10.1177/1473095208099294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel M, Haddad L, Garrett J. Some urban facts of life: implications for research and policy. World Dev 1999;27:1917–38. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00095-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rydin Y, Bleahu A, Davies M et al. Shaping cities for health: complexity and the planning of urban environments in the twenty-first century. Lancet 2012;379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60435-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salud MALB, Gallardo JI, Dineros JA et al. People’s initiative to counteract misinformation and marketing practices: the Pembo, Philippines breastfeeding experience, 2006. J Hum Lactation 2009;25:341–49. doi: 10.1177/0890334409334605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandøy IF, Zyambo C, Michelo C et al. Targeting condom distribution at high-risk places increases condom utilization-evidence from an intervention study in Livingstone, Zambia. BMC Public Health 2012;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawar YR, Crane LG. Generating global political priority for urban health: the role of the urban health epistemic community. Health Policy Plann 2017;32:1161–73. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AK, Mhazo M, Moyo S et al. The feasibility of voluntary counselling and HIV testing for pregnant women using community volunteers in Zimbabwe. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:755–59. doi: 10.1258/095646205774763090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmel G. The metropolis and mental life. In: Wolff KH (ed.), The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: The Free Press, 1950, 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Vithayathil T, Pradhan KC. Recasting inequality: residential segregation by caste over time in urban India. Environ Urban 2019;31:615–34. doi: 10.1177/0956247818812330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss K. Labour geography 1: towards a geography of precarity? Prog Hum Geogr 2018;42:622–30. doi: 10.1177/0309132517717786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tilahun H, Fekadu B, Abdisa H et al. Ethiopia’s health extension workers use of work time on duty: time and motion study. Health Policy Plann 2017;32:320–28. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM et al. Thirty-six-month outcomes of a generalist paraprofessional perinatal home visiting intervention in South Africa on maternal health and child health and development. Prevent Sci 2016;17:937–48. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0676-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkiss F. Cities By Design: The Social Life of Urban Form. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies F. Community & Society (Gemeinschaft Und Gesellschaft). East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker A, de Swardt G, Struthers H et al. Understanding the needs of township men who have sex with men (MSM) health outreach workers: exploring the interplay between volunteer training, social capital, and critical consciousness. AIDS & Behav 2013;17:S33–42. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0287-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver S, Oti S, Oduor C et al. Challenges of health programmes in slums. Lancet 2015;386:2114–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00385-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Ghettos and anti-ghettos: an anatomy of the new urban poverty. Thesis Eleven 2008;94:113–18. doi: 10.1177/0725513608093280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MJ, Puello E, Meade M et al. Evidence of diffusion from a targeted HIV/AIDS intervention in the Dominican Republic. J Biosoc Sci 2001;33:107–19. doi: 10.1017/s0021932001001079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesuriya M, Fountoulakis N, Guess N et al. A pragmatic lifestyle modification programme reduces the incidence of predictors of cardio-metabolic disease and dysglycaemia in a young healthy urban South Asian population: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med 2017;15:146. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0905-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth L. Urbanism as a way of life. Am J Soc 1938;44:1–24. doi: 10.1086/217913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize Community Health Worker Programmes. 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275474/9789241550369-eng.pdf (27 November 2024, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- Yan HJ, Zhang RJ, Wei CY et al. A peer-led, community-based rapid HIV testing intervention among untested men who have sex with men in China: an operational model for expansion of HIV testing and linkage to care. Sex Transm Infec 2014;90:388–93. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.