Abstract

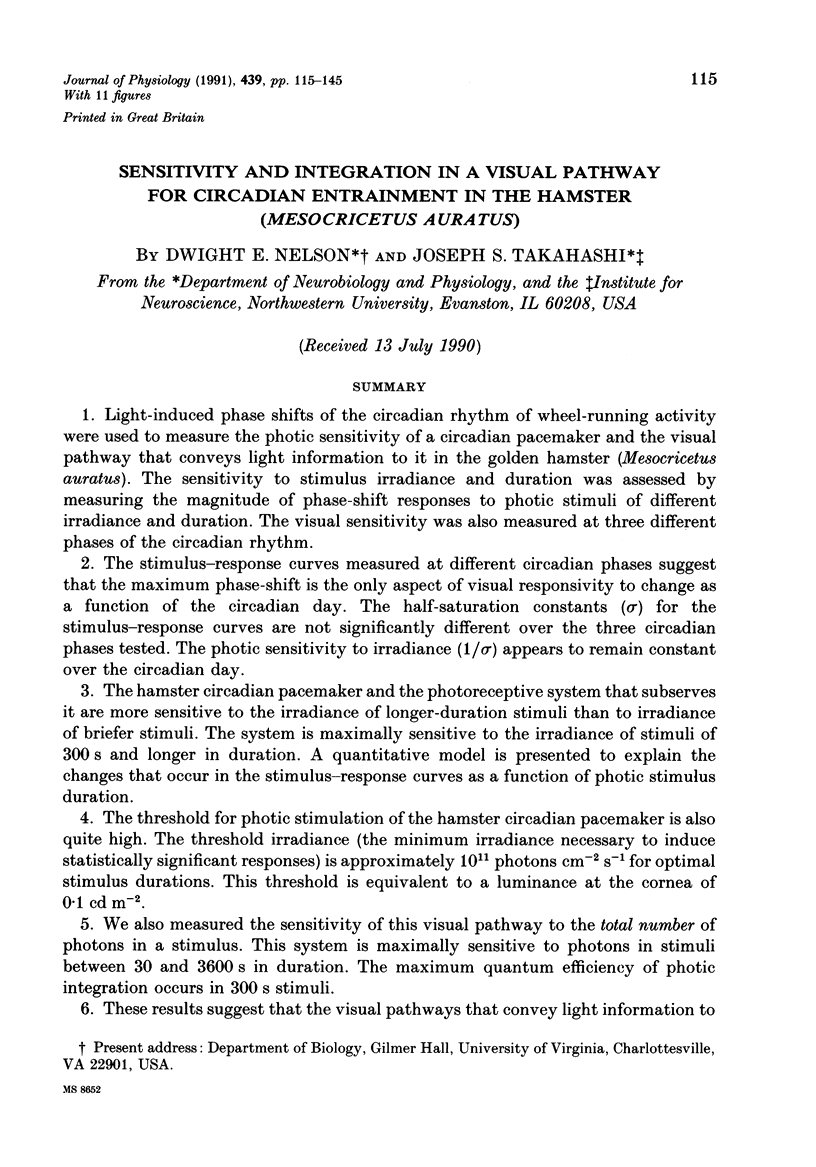

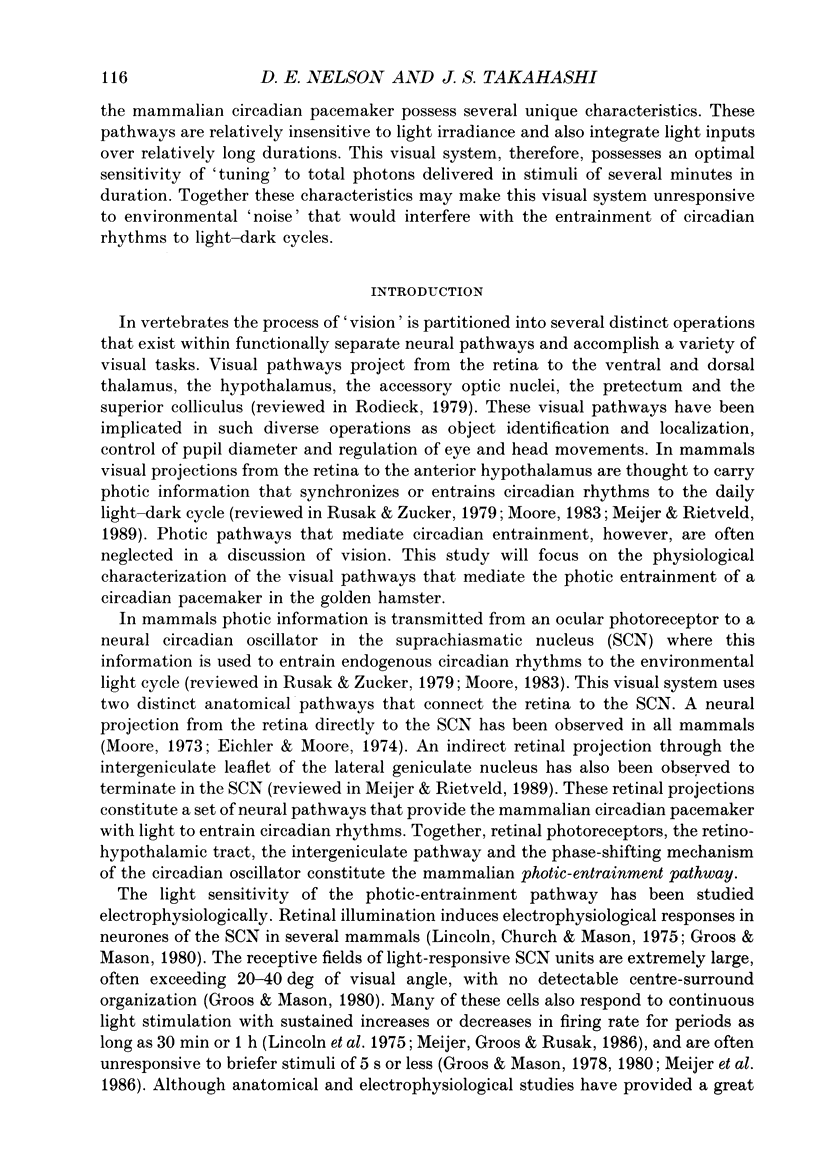

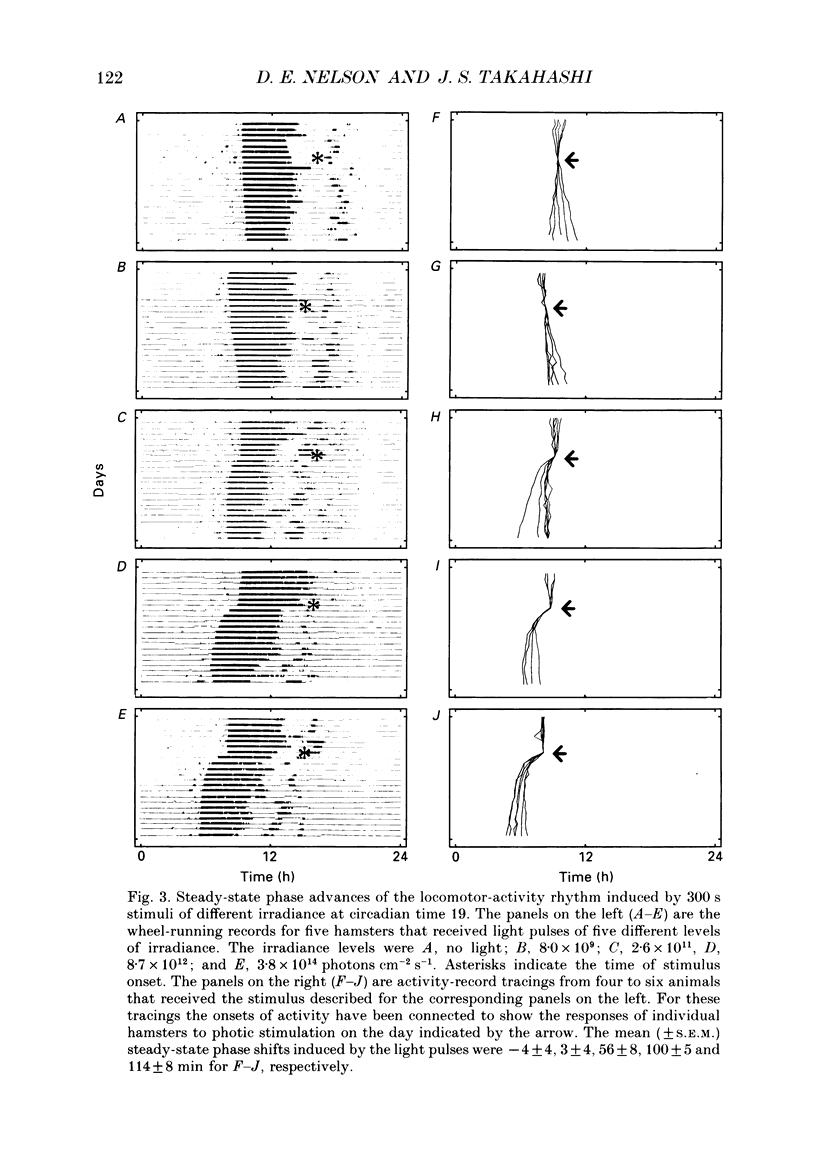

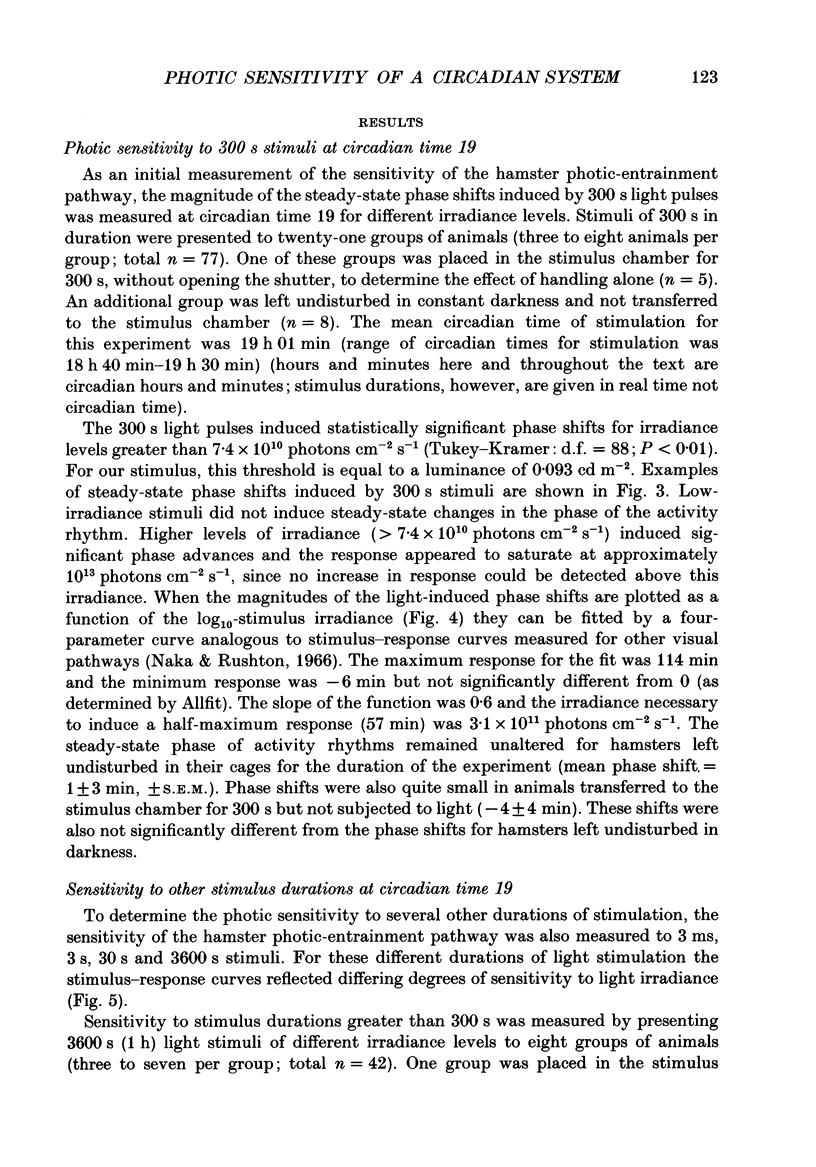

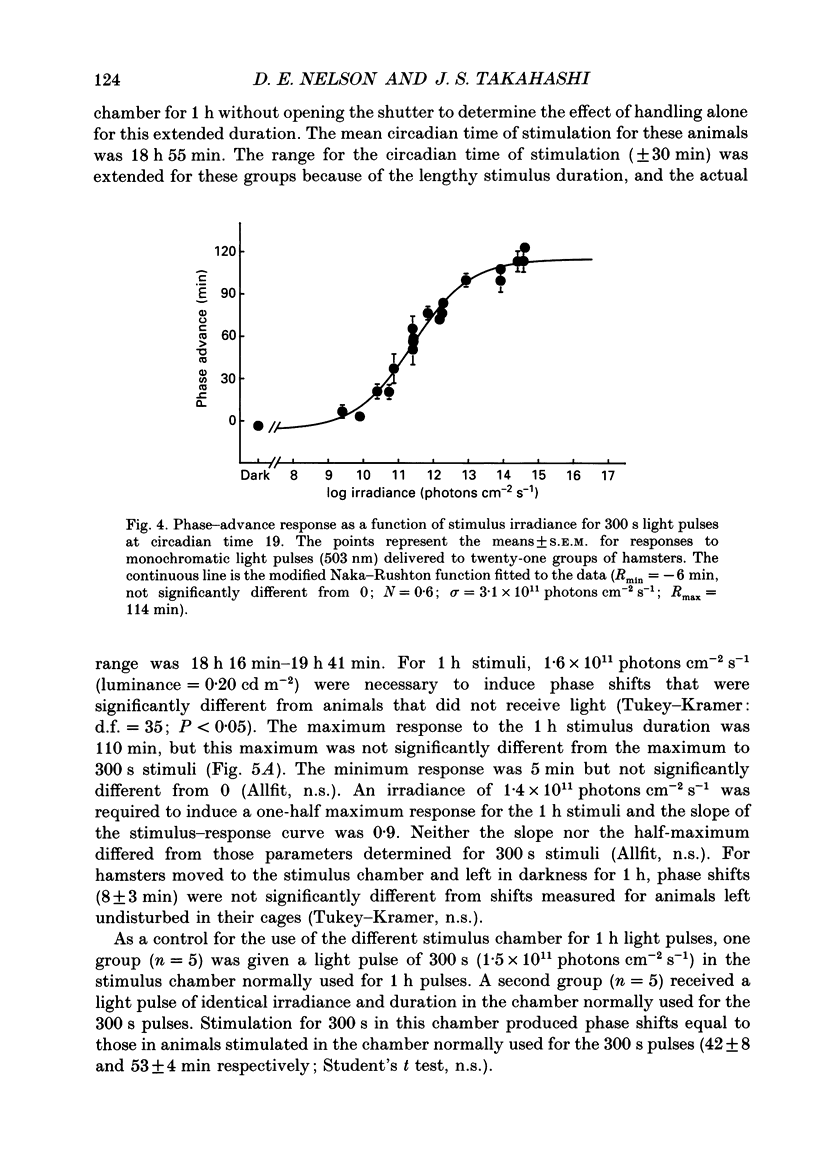

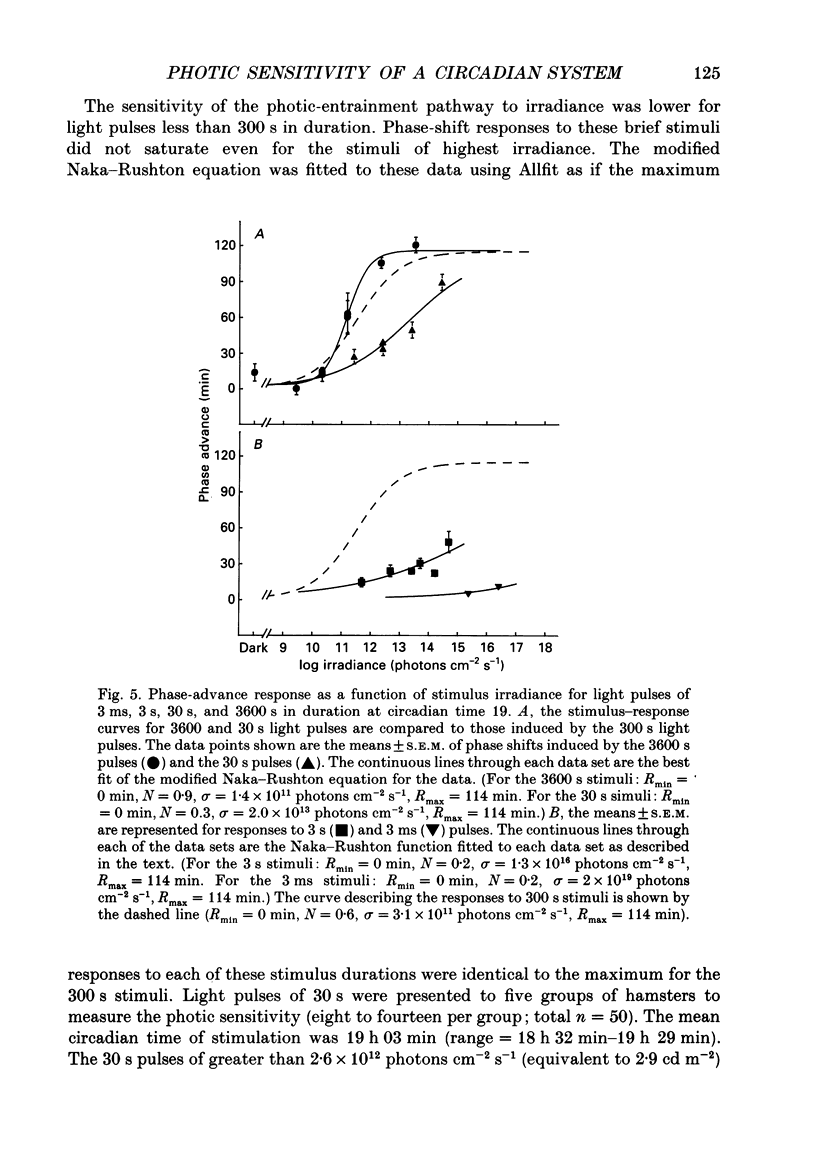

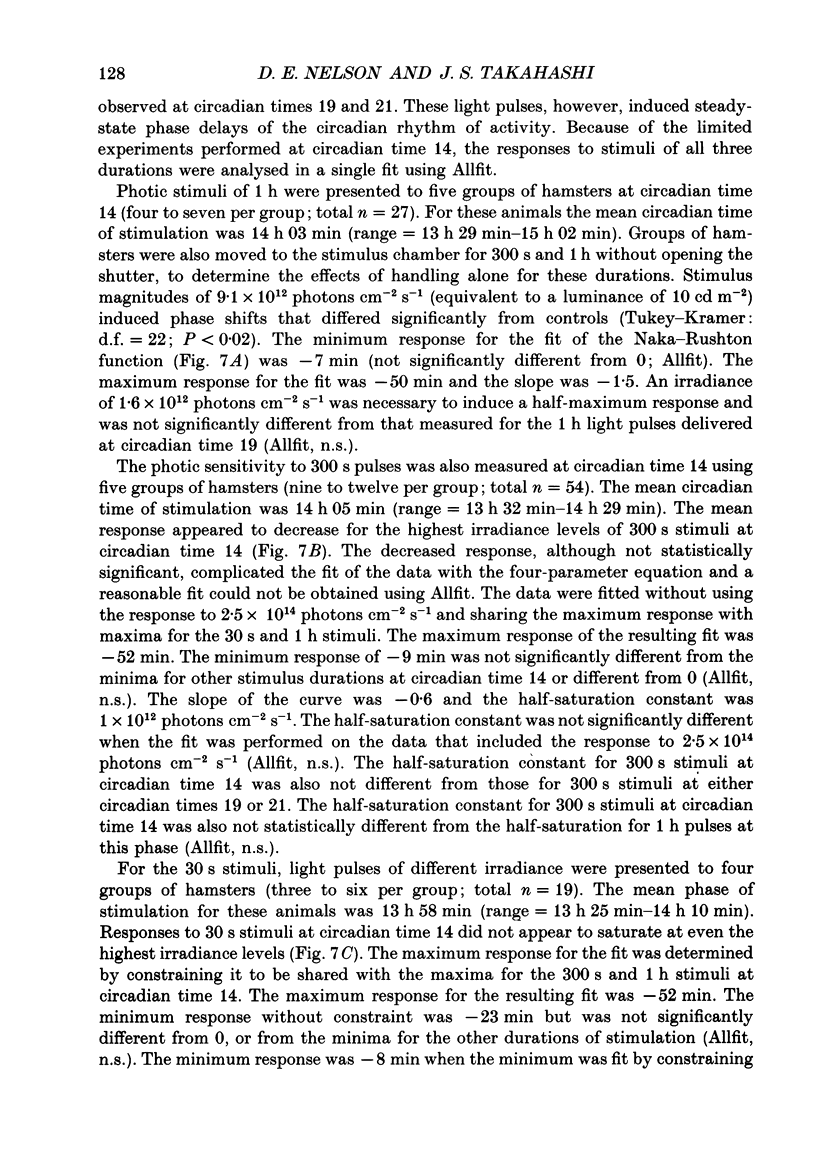

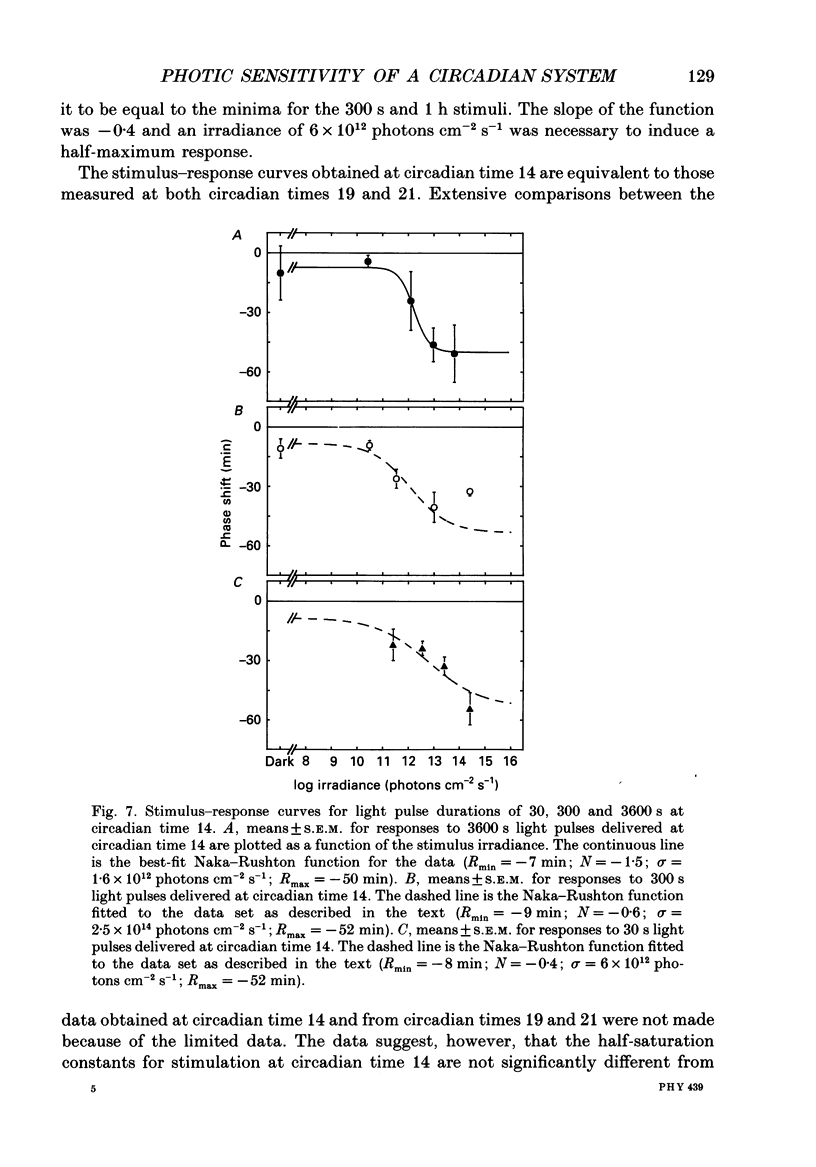

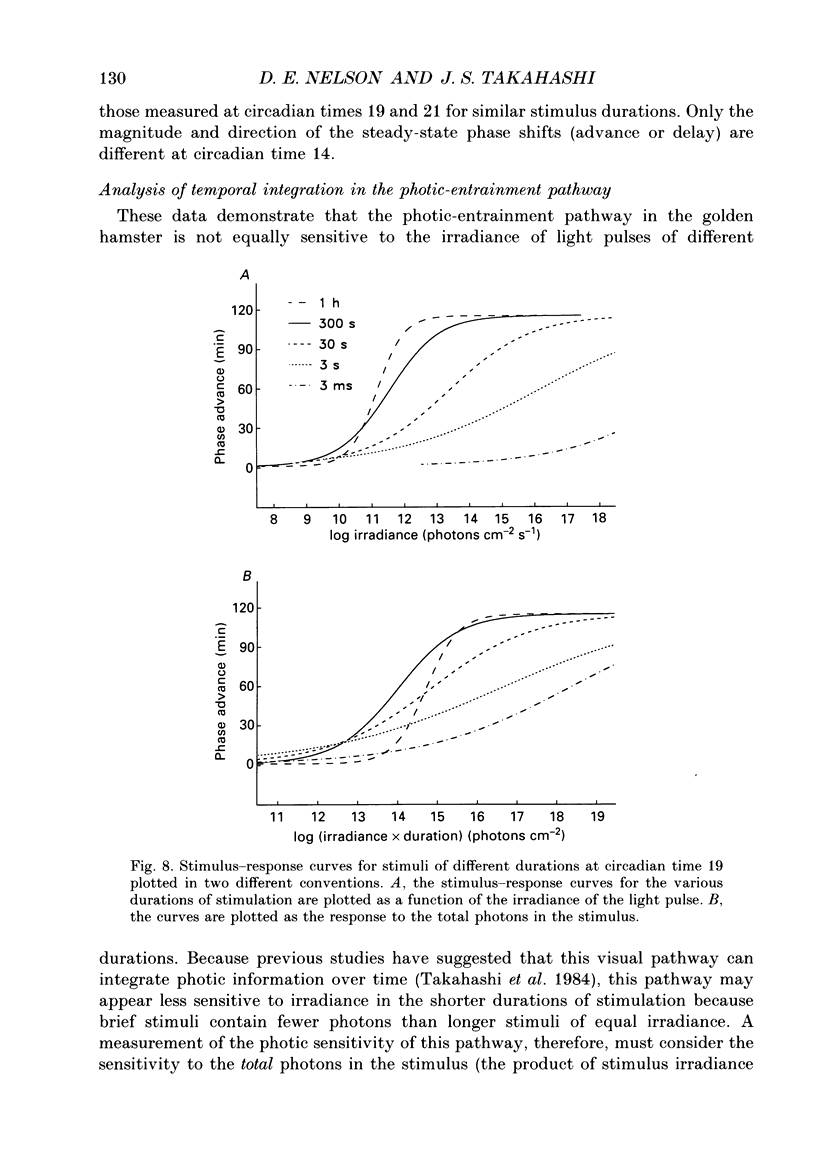

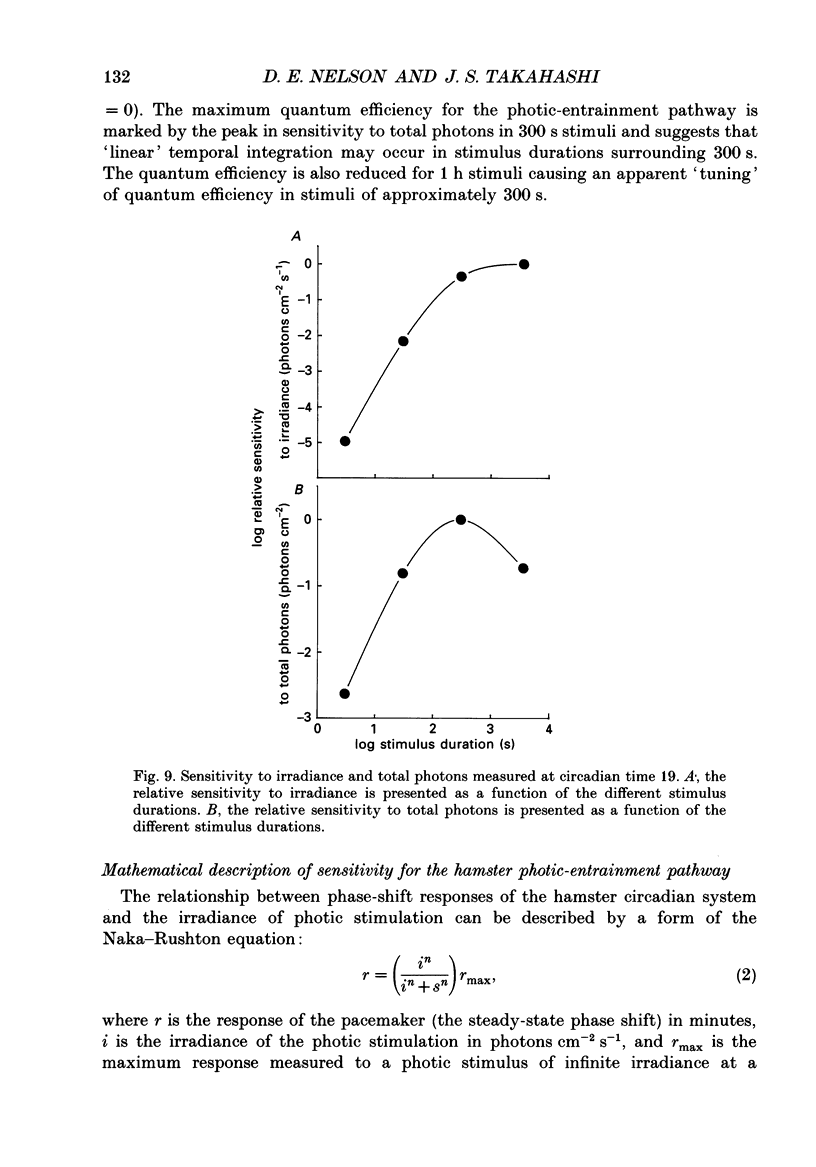

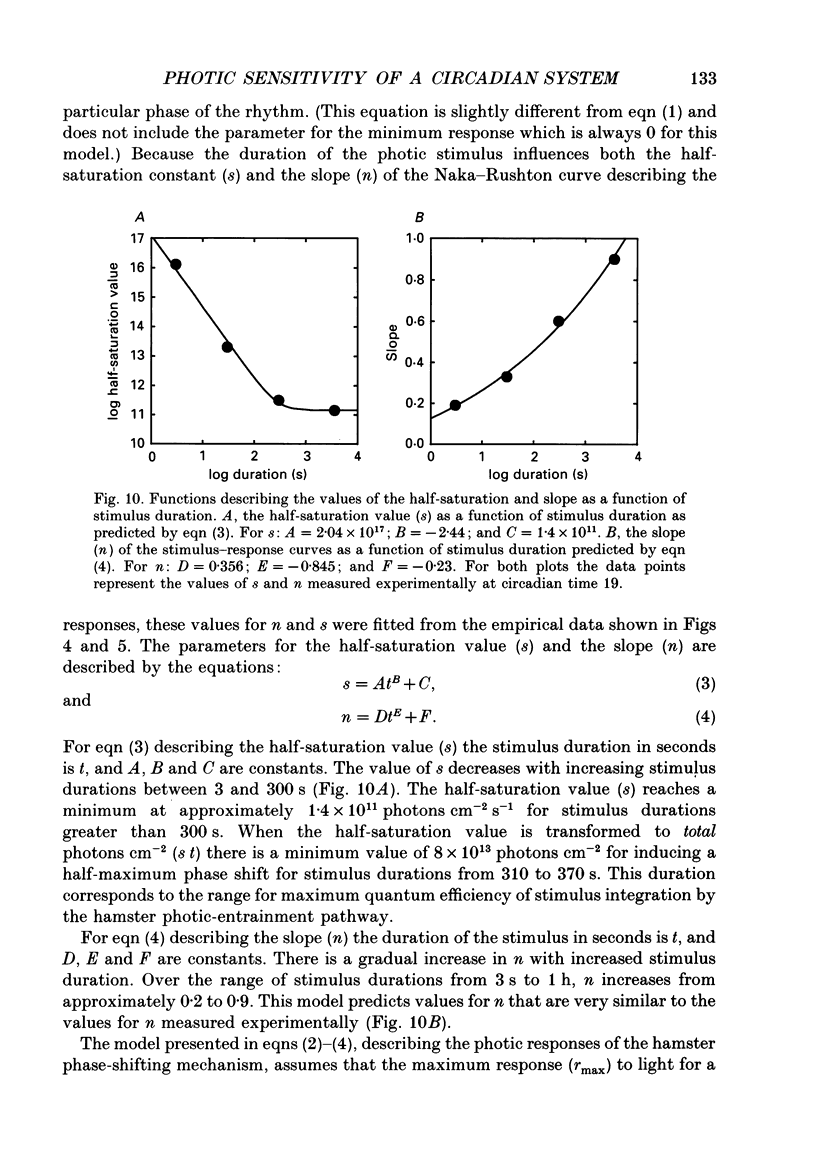

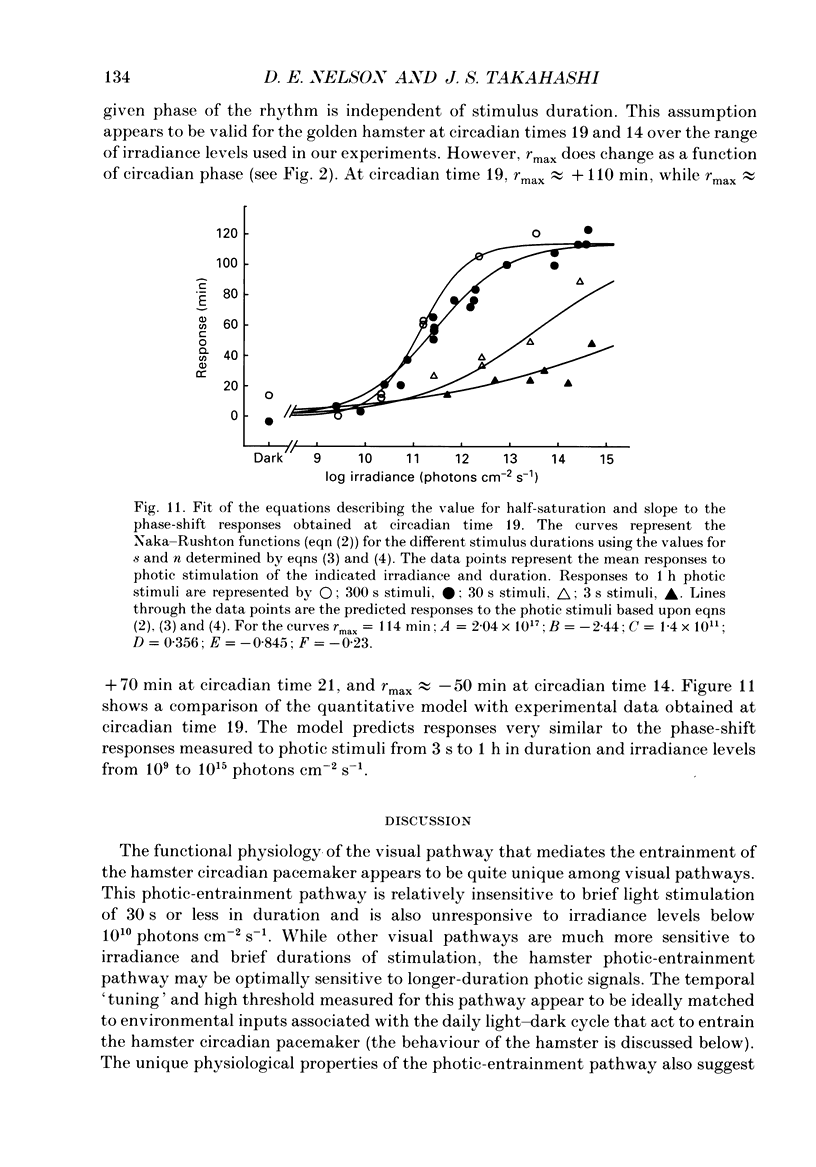

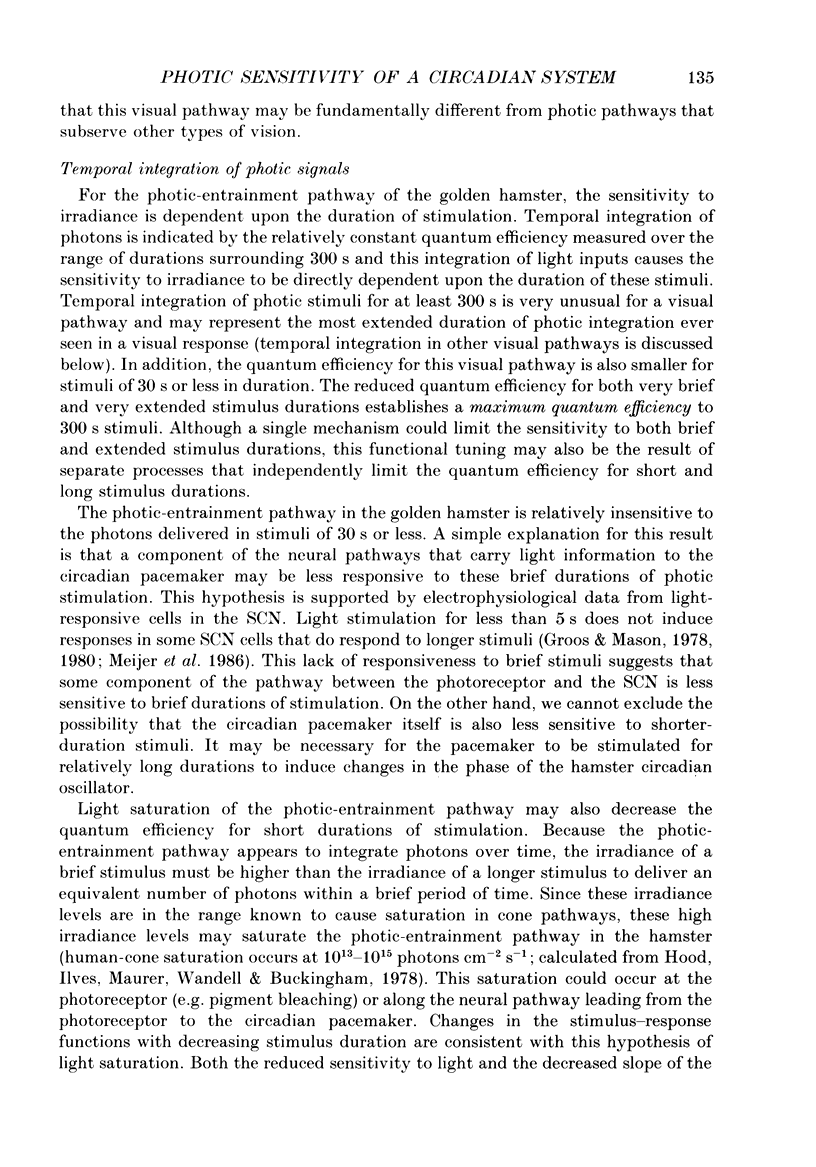

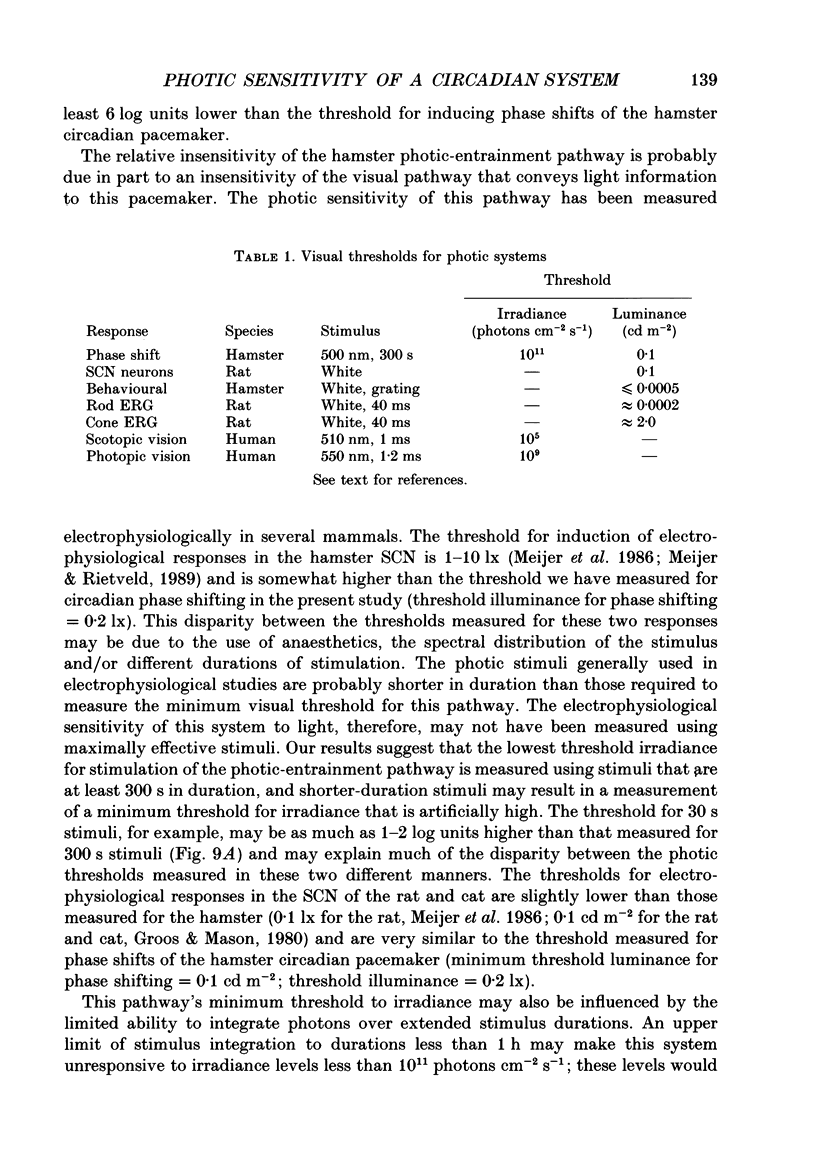

1. Light-induced phase shifts of the circadian rhythm of wheel-running activity were used to measure the photic sensitivity of a circadian pacemaker and the visual pathway that conveys light information to it in the golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus). The sensitivity to stimulus irradiance and duration was assessed by measuring the magnitude of phase-shift responses to photic stimuli of different irradiance and duration. The visual sensitivity was also measured at three different phases of the circadian rhythm. 2. The stimulus-response curves measured at different circadian phases suggest that the maximum phase-shift is the only aspect of visual responsivity to change as a function of the circadian day. The half-saturation constants (sigma) for the stimulus-response curves are not significantly different over the three circadian phases tested. The photic sensitivity to irradiance (1/sigma) appears to remain constant over the circadian day. 3. The hamster circadian pacemaker and the photoreceptive system that subserves it are more sensitive to the irradiance of longer-duration stimuli than to irradiance of briefer stimuli. The system is maximally sensitive to the irradiance of stimuli of 300 s and longer in duration. A quantitative model is presented to explain the changes that occur in the stimulus-response curves as a function of photic stimulus duration. 4. The threshold for photic stimulation of the hamster circadian pacemaker is also quite high. The threshold irradiance (the minimum irradiance necessary to induce statistically significant responses) is approximately 10(11) photons cm-2 s-1 for optimal stimulus durations. This threshold is equivalent to a luminance at the cornea of 0.1 cd m-2. 5. We also measured the sensitivity of this visual pathway to the total number of photons in a stimulus. This system is maximally sensitive to photons in stimuli between 30 and 3600 s in duration. The maximum quantum efficiency of photic integration occurs in 300 s stimuli. 6. These results suggest that the visual pathways that convey light information to the mammalian circadian pacemaker possess several unique characteristics. These pathways are relatively insensitive to light irradiance and also integrate light inputs over relatively long durations. This visual system, therefore, possesses an optimal sensitivity of 'tuning' to total photons delivered in stimuli of several minutes in duration. Together these characteristics may make this visual system unresponsive to environmental 'noise' that would interfere with the entrainment of circadian rhythms to light-dark cycles.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adelson E. H. Saturation and adaptation in the rod system. Vision Res. 1982;22(10):1299–1312. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton R. M., Whitten D. N. Visual adaptation in monkey cones: recordings of late receptor potentials. Science. 1970 Dec 25;170(3965):1423–1426. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3965.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPBELL F. W., RUSHTON W. A. Measurement of the scotopic pigment in the living human eye. J Physiol. 1955 Oct 28;130(1):131–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson L. D., LaVail M. M., Sidman R. L. Differential effect of the rd mutation on rods and cones in the mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978 Jun;17(6):489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENTON E. J., PIRENNE M. H. The absolute sensitivity and functional stability of the human eye. J Physiol. 1954 Mar 29;123(3):417–442. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DODT E., ECHTE K. Dark and light adaptation in pigmented and white rat as measured by electroretinogram threshold. J Neurophysiol. 1961 Jul;24:427–445. doi: 10.1152/jn.1961.24.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DODT E., HEERD E. Mode of action of pineal nerve fibers in frogs. J Neurophysiol. 1962 May;25:405–429. doi: 10.1152/jn.1962.25.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoursey P. J. Light-sampling behavior in photoentrainment of a rodent circadian rhythm. J Comp Physiol A. 1986 Aug;159(2):161–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00612299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLean A., Munson P. J., Rodbard D. Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. Am J Physiol. 1978 Aug;235(2):E97–102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling J. E. The site of visual adaptation. Science. 1967 Jan 20;155(3760):273–279. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3760.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dräger U. C., Hubel D. H. Studies of visual function and its decay in mice with hereditary retinal degeneration. J Comp Neurol. 1978 Jul 1;180(1):85–114. doi: 10.1002/cne.901800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnest D. J., Turek F. W. Effect of one-second light pulses on testicular function and locomotor activity in the golden hamster. Biol Reprod. 1983 Apr;28(3):557–565. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod28.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler V. B., Moore R. Y. The primary and accessory optic systems in the golden hamster, Mesocricetus auratus. Acta Anat (Basel) 1974;89(3):359–371. doi: 10.1159/000144298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson V. F. Grating acuity of the golden hamster. The effects of stimulus orientation and luminance. Exp Brain Res. 1980;38(1):43–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00237929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank K. D., Zimmerman W. F. Action spectra for phase shifts of a circadian rhythm in Drosophila. Science. 1969 Feb 14;163(3868):688–689. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3868.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. G. Scotopic and photopic components of the rat electroetinogram. J Physiol. 1973 Feb;228(3):781–797. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groos G. A., Meijer J. H. Effects of illumination on suprachiasmatic nucleus electrical discharge. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;453:134–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb11806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood D. C., Ilves T., Maurer E., Wandell B., Buckingham E. Human cone saturation as a function of ambient intensity: a test of models of shifts in the dynamic range. Vision Res. 1978;18(8):983–993. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi D., Chandrashekaran M. K. Bright light flashes of 0.5 milliseconds reset the circadian clock of a microchiropteran bat. J Exp Zool. 1984 May;230(2):325–328. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402300219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARRIOTT F. H. THE FOVEAL ABSOLUTE VISUAL THRESHOLD FOR SHORT FLASHES AND SMALL FIELDS. J Physiol. 1963 Nov;169:416–423. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer J. H., Groos G. A., Rusak B. Luminance coding in a circadian pacemaker: the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the rat and the hamster. Brain Res. 1986 Sep 10;382(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer J. H., Rietveld W. J. Neurophysiology of the suprachiasmatic circadian pacemaker in rodents. Physiol Rev. 1989 Jul;69(3):671–707. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menaker M., Underwood H. Extraretinal photoreception in birds. Photophysiology. 1976 Apr;23(4):299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1976.tb07251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. Y. Organization and function of a central nervous system circadian oscillator: the suprachiasmatic hypothalamic nucleus. Fed Proc. 1983 Aug;42(11):2783–2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. Y. Retinohypothalamic projection in mammals: a comparative study. Brain Res. 1973 Jan 30;49(2):403–409. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOELL W. K. Differentiation, metabolic organization, and viability of the visual cell. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958 Oct;60(4 Pt 2):702–733. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080722016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z. M., Misanin J. R. Visual perception in the retinal degenerate C3H mouse. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1970 Aug;72(2):306–310. doi: 10.1037/h0029465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka K. I., Rushton W. A. S-potentials from luminosity units in the retina of fish (Cyprinidae). J Physiol. 1966 Aug;185(3):587–599. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PITTENDRIGH C. S. Circadian rhythms and the circadian organization of living systems. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1960;25:159–184. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1960.025.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh C. S., Takamura T. Latitudinal clines in the properties of a circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms. 1989 Summer;4(2):217–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt B. L., Goldman B. D. Activity rhythms and photoperiodism of Syrian hamsters in a simulated burrow system. Physiol Behav. 1986 Jan;36(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodieck R. W. Visual pathways. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1979;2:193–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.02.030179.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusak B., Zucker I. Neural regulation of circadian rhythms. Physiol Rev. 1979 Jul;59(3):449–526. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver P. H. Spectral sensitivity of the white rat by a training method. Vision Res. 1967 May;7(5):377–383. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(67)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi J. S., DeCoursey P. J., Bauman L., Menaker M. Spectral sensitivity of a novel photoreceptive system mediating entrainment of mammalian circadian rhythms. Nature. 1984 Mar 8;308(5955):186–188. doi: 10.1038/308186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. A., Olton D. S. Circadian rhythm of luminance detectability in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1979 Jul;23(1):17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfree A. T. On the photosensitivity of the circadian time-sense in Drosophilia pseudoobscura. J Theor Biol. 1972 Apr;35(1):159–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(72)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman W. F., Goldsmith T. H. Photosensitivity of the circadian rhythm and of visual receptors in carotenoid-depleted Drosophila. Science. 1971 Mar 19;171(3976):1167–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3976.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]