Abstract

Candida albicans strain WO-1 switches spontaneously and reversibly between a “white” and “opaque” phenotype that affects colony morphology, cellular phenotype, and expression of a number of phase-specific genes and virulence traits. To assess the role of the transcription regulator Tup1p in this phenotypic transition, both TUP1 alleles were deleted in the mutant Δtup1. Δtup1 formed “fuzzy large” colonies made up of cells growing exclusively in the filamentous form. Δtup1 cells did not undergo the white-opaque transition, but it did switch spontaneously, at high frequency (∼10−3), and unidirectionally through the following sequence of colony (and cellular) phenotypes: “fuzzy large” (primarily hyphae) → “fuzzy small” (primarily pseudohyphae) → “smooth” (primarily budding yeast) → “revertant fuzzy” (primarily pseudohyphae). Northern analysis of white-phase, opaque-phase, and hypha-associated genes demonstrated that Tup1p also plays a role in the regulation of select phase-specific genes and that each variant in the Δtup1 switching lineage differs in the level of expression of one or more phase-specific and/or hypha-associated genes. Using a rescued Δtup1 strain, in which TUP1 was placed under the regulation of the inducible MET3 promoter, white- and opaque-phase cells were individually subjected to a regime in which TUP1 was first downregulated and then upregulated. The results of this experiment demonstrated that (i) downregulation of TUP1 led to exclusive filamentous growth in both originally white- and opaque-phase cells; (ii) the white-phase-specific gene WH11 continued to be expressed in TUP1 downregulated cultures originating from white-phase cells, while WH11 expression remained repressed in TUP1-downregulated cultures originating from opaque-phase cells, suggesting that cells maintained phase identity in the absence of TUP1 expression; and (iii) subsequent upregulation of TUP1 resulted in mass conversion of originally white-phase cells to the opaque phase and maintenance of originally opaque-phase cells in the opaque phase and in the resumption in both cases of switching, suggesting that TUP1 reexpression turns on the switching system in the opaque phase.

Candida albicans and related species can switch spontaneously, reversibly, and at very high frequencies (10−4 to 10−2) between two or more general phenotypes distinguishable by differences in colony morphology (24, 37, 43, 44, 45). Because switching can affect a variety of different virulence traits (46, 49), it has been suggested that it plays a role in generating variability in colonizing populations for rapid adaptation to environmental challenges (35, 46). To elucidate the mechanisms involved in switching, the reversible white-opaque transition in strain WO-1 (44) has served as an experimental model system, since it involves only two dominant phases, has a dramatic impact on cellular morphology, can be discriminated on all tested agars, and involves the precise regulation of a number of phase-specific genes at the level of transcription (33, 39, 45, 47, 48, 50).

The white-opaque transition can be separated conceptually into three components: the switch events from white to opaque and from opaque to white, the maintenance of the alternative white and opaque phases, and the downstream regulation of phase-specific genes. Recently, it was demonstrated that the histone deacetylases Hdalp and Rpd3p play roles in suppressing switching in strain WO-1—Hdalp selectively in the white-to-opaque direction and Rpd3p in both the white-to-opaque and the opaque-to-white directions (21, 56)—and that the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sir2p (18) plays a role in suppressing the 3153A-type switching system in strain CAI4 (36). Through the functional characterization of the promoters of coordinately regulated white and opaque-phase-specific genes, a complex pattern of downstream regulation has emerged involving phase-regulated trans-acting factors interacting with phase-specific cis-acting sequences (26, 48, 51-55). The functional characterization of the promoter of the opaque-phase-specific gene OP4 revealed that developmental activation in the opaque phase was mediated through a MADS box protein consensus binding sequence similar to the Mcm1p consensus binding site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, implicating an Mcm1p homolog in phase-specific gene regulation (26). The MADS box binding site in the OP4 promoter is bordered upstream by an α2-like binding site and downstream by an α1-like binding site (49). In S. cerevisiae, the pervasive Tup1p-Ssn6p corepressor complex is recruited by sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins (19, 60, 61), most prominent among them being α2-Mcm1p, which recruits the complex to the promoters of a-specific genes (12, 15, 22). C. albicans possesses homologs to all of this machinery (62), including TUP1 (6), SSN6 (62), α2 (17), and MCM1 (56), suggesting that it may use similar mechanisms to regulate phase-specific gene expression during switching.

In C. albicans, Tup1p has been demonstrated to play a role both in the regulation of the bud-hypha transition and the transcription of a variety of genes, including genes involved in virulence (6-8). Deletion of TUP1 in C. albicans strain CAI4 (14) resulted in exclusive filamentous growth (6), and the simultaneous deletion of TUP1 and the transcription factor EFG1 (25, 59) resulted in a return to the budding yeast form (7). Differences in the patterns of gene transcription and the capacity of the tup1 efg1 double mutant to return to the budding yeast form and still grow in the filamentous form (7, 8), support the idea articulated by Mitchell (29) and by Brown and Gow (10) that there are several pathways, rather than a single pathway, leading to filamentous growth and that resulting filamentous cells that appear morphologically similar may in fact be biochemically distinct (7, 8). To examine the role of TUP1 in the process of high-frequency phenotypic switching, we generated and characterized two independent TUP1 deletion mutants and two rescued strains in which TUP1 was placed under the control of an inducible promoter in strain WO-1. The results demonstrated that Tup1p expression is necessary for the phenotypic transition between the white and opaque phenotypes, is involved in the downstream regulation of phase-specific gene expression, and may participate in the actual switch event.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maintenance of stock cultures.

C. albicans strain WO-1 (44) was maintained on agar containing supplemented Lee's medium (3), the ade2 auxotrophic derivative Red 3/6 was maintained on this agar supplemented with 0.6 mM adenine (51), and a ura3 auxotrophic derivative of Red 3/6, TS3.3, was maintained on this agar supplemented with 0.01 mM uridine (54). The URA3 derivative of TS3.3, TU17, the TUP1 deletion mutants, and the TUP1 rescued strains described in the following sections were maintained on agar containing supplemented Lee's medium. To avoid repeated passage, all strains were stored frozen at −80°C. The strains used in this study plus their genotypes are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Genotypes of strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| WO-1 | Wild type | 44 | |

| Red 3/6 | WO-1 | ade2/ade2 | 51 |

| TS3.3 | Red 3/6 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 | 54 |

| TU17 | TS3.3 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/URA3 | 54 |

| Thet1 | TS3.3 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG-URA3-hisG/TUP1 | This study |

| Thet1-p1 | Thet1 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/TUP1 | This study |

| Thet1-p2 | Thet1 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/TUP1 | This study |

| Δtup1-1 | Thet1 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/Δtup1::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| Δtup1-2 | Thet1 | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/Δtup1::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| Δtup1-1p1 | Δtup1-1 (fuzzy large) | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/Δtup1::hisG | This study |

| Δtup1-1p2 | Δtup1-1 (smooth) | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/Δtup1::hisG | This study |

| Δtup1-1res1 | Δtup1-1 (fuzzy large) | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/Δtup1::hisG RP10/RP10-TUP1-URA3a | This study |

| Δtup1-1res2 | Δtup1-1 (smooth) | ade2/ade2 Δura3::ADE2/Δura3::ADE2 Δtup1::hisG/Δtup1::hisG RP10/RP10-TUP1-URA3a | This study |

Δtup1-1res1 and Δtup1-1res2 were constructed with TUP1 under the control of the MET3 promoter as explained in Materials and Methods.

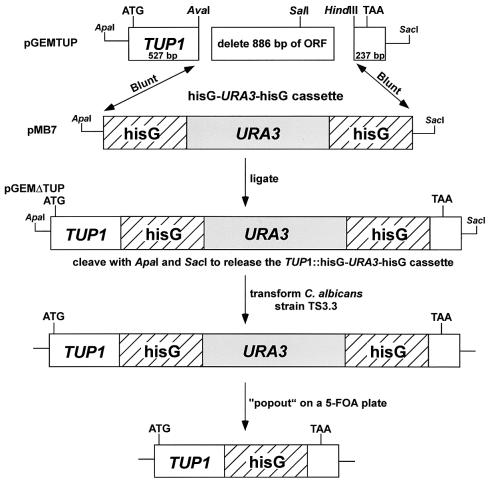

Isolation of the TUP1 gene and construction of the TUP1 knockout vector

Primers were designed based on the published TUP1 sequence (6). Using primers TUPF and TUPR (Table 2), a 1.7-kb PCR fragment was amplified and ligated to the pGEM T-EASY vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.) to create plasmid pGEMTUP (Fig. 1). The full-length clone containing TUP1, as well as 18 nucleotides upstream of the ATG start codon and 120 nucleotides downstream of the TAA stop codon, were confirmed by sequencing. An 886-bp fragment between an AvaI and a HindIII site, located 508 and 1,394 bp, respectively, downstream of the ATG codon, was removed from pGEMTUP, leaving 527 bp upstream and 273 bp downstream of TUP1. The two ends of the plasmid were end repaired by treating them with T4 DNA polymerase, and the 4.0-kb hisG-URA3-hisG cassette from pMB7 (14), which had also been end repaired after excision with BglII and SalI, was ligated at the blunt ends to create plasmid pGEMΔTUP (Fig. 1). For transformation, this plasmid was cleaved by using ApaI and SacI to release the TUP1-hisG-URA3-hisG cassette. Heterozygous TUP1 deletion mutants were generated by transforming the ura3 auxotrophic strain TS3.3 (54) with 25 μg of the TUP1-hisG-URA3-hisG cassette by the lithium acetate method (41). Thirty-six URA3 prototrophic heterozygotes were confirmed by Southern analysis. The heterozygote Thet1 was plated on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) agar to select for spontaneous ura3 pop-out deletion strains (Fig. 1). Pop-out deletion strains Thet1-p1 and Thet1-p2 were confirmed by Southern analysis. A second round of transformation with the same construct was performed on Thet1-p1. Forty-eight potential homozygous TUP1 deletion mutants were identified based on URA3 prototrophy. Two, Δtup1-1 and Δtup1-2, were confirmed by Southern analysis to be homozygous deletion mutants and were selected for further analysis (Fig. 2). Both exhibited a wrinkled colony phenotype. Since the heterozygous and homozygous deletion strains were URA3+, the parental strain TS3.3, which was ura−, was transformed with an URA3-containing fragment to generate the control strain TU17 (56).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in the study

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| TUPF | 5′-CGC GGA TCC CCA CCA GCA ATG TCC ATG TAT-3′ |

| TUPR | 5′-GCG GGT ACC GCG ATG TTG ACG GGT GCT GT-3′ |

| OP4NDEIF | 5′-GG CAT ATG AAG TTT TCA CAA GCC-3′ |

| OP4SPHIR | 5′-GGT GGT TGC TCT TCC GCA CTA ATA AAG TTT TCT TTT-3′ |

| FANEFG15′ | 5′-GCG TCG CGA ATG TCA ACG TAT TCT ATA-3′ |

| FANEFG13′ | 5′-GCG CCG CGG CTT TTC TTC TTT GGC AAC AGT CGT-3′ |

| SAP3F | 5′-CCT TCT CTA AAA TTA TGG ATT GGA AC-3′ |

| SAP3R | 5′-TTG ATT TCA CCT TGG GGA CCA GTA ACA TTT-3′ |

| ECE1F | 5′-TCT CAA GCT GCC ATC ATC CA-3′ |

| ECE1R | 5′-AGA TTC AGC TGA TCT AGT AA-3′ |

| HWP1F | 5′-CAC AGG TAG ACG GTC AAG GT-3′ |

| HWP1R | 5′-GAT CCA GAA GTA ACT GGA ACA GAA CTT-3′ |

| RBT5F | 5′-ATG CTC GCC TTA TCC TTA TTG-3′ |

| RBT5R | 5′-AGC TGG CAT GTT ACC GGC GT-3′ |

FIG. 1.

Protocol for creating TUP1 deletion mutants. The plasmid pGEMΔTUP was derived from pGEMTUP by replacing 886 bp of the TUP1 open reading frame with the hisG-URA3-hisG cassette. The plasmid pGEMΔTUP was cleaved with ApaI and SacI to release the TUP1-hisG cassette, which was used to transform the C. albicans ura3 auxotrophic strain TS3.3. Heterozygous transformants were grown on 5-FOA to obtain a pop-out derivative, which was used to obtain the homozygous deletion mutant by repeating the method.

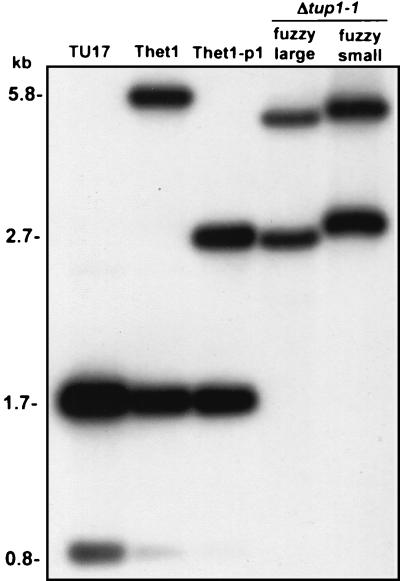

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of the null mutant Δtup1-1. Approximately 3 μg each of total genomic DNA from the parental strain TU17, the heterozygous deletion mutant Thet1, the pop-out derivative of Thet1, Thet1-p1, the original deletion mutant Δtup1-1 exhibiting the “fuzzy large” phenotype, and the Δtup1-1 variant exhibiting the “fuzzy small” phenotype were individually digested with SalI and subjected to Southern blotting. Blots were hybridized with the TUP1 probe. The size in kilobases of the fragments is shown to the left of the patterns. The small differences in migration of the 5.8- and 2.7-kb bands were due to differences in the amount of DNA loaded.

Rescue of the Δtup1 strain with TUP1 under the control of an inducible promoter.

The 1.7-kb fragment TUP1 open reading frame was inserted at the multiple cloning site immediately downstream of the MET3 promoter, which is repressed by exogenous methionine, in the plasmid pCaExp (a generous gift of Peter Sudbery, Cheffield University, Cheffield, United Kingdom) (11). The correct insert in clone pCET1 was confirmed by sequencing. Integration was targeted to the RP10 locus by linearizing the plasmid at a unique NcoI site in the RP10 gene (11). By using the lithium acetate method (41), linearized plasmids were used to transform the ura3− strains Δtup1-1p1 and Δtup1-1p2, URA3 pop-out derivatives generated from a Δtup1-1 “fuzzy large” and a Δtup1-1 “smooth” variant, respectively. Transformants were confirmed by Southern blot hybridization. To express TUP1, transformed cells were grown on agar plates containing modified Lee's medium with no methionine. To repress TUP1, cells were replated on supplemented Lee's medium (3) containing 0.67 mM methionine and incubated for 5 days at 25°C. The rescued strain Δtup1-1res1, derived from Δtup1-1 exhibiting the fuzzy large phenotype, and Δtup1-1res2, derived from Δtup1-1 exhibiting the smooth phenotype, were selected for further analysis. The genotypes of Δtup1-1res1 and Δtup1-1res2 are presented in Table 1.

Testing phase identity in the absence of TUP1 expression.

Cells of strain Δtup1-1res1 were grown at a low density on agar containing modified Lee's medium (3) in the absence of methionine, conditions under which TUP1 is expressed. Cells from a 5-day-old white-phase colony and cells from a 5-day-old opaque-phase colony were collected and grown overnight in modified Lee's liquid medium in the absence of methionine and then plated at low density on agar containing modified Lee's medium supplemented with 0.67 mM methionine, conditions which downregulate TUP1 expression, and grown as individual colonies for 5 days at 25°C. Two alternative protocols were then employed. First, by using velvet cloth, cells were replicate plated onto agar medium lacking methionine. Alternatively, cells from several colonies were pooled, diluted, vortexed, and plated at a low density onto agar medium lacking methionine. In both cases, the final agar medium contained phloxine B, which differentially stains opaque-phase cells red. Colonies were scored as white or opaque after 5 days of growth at 25°C.

Southern and Northern blot analysis.

For Southern analysis, genomic DNA was extracted (40) from cells grown in liquid YPD medium at 37°C. Three micrograms of DNA was digested with SalI, and the resulting fragments were separated on a 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel. DNA was transferred to Zetabind nylon membrane (Cuno, Inc., Meriden, Conn.) and hybridized with the C. albicans TUP1 gene labeled by random priming with [α-32P]dCTP. For Northern analysis, cells in the exponential phase of growth were homogenized with acid-washed glass beads in a bead beater (Bio-Spec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). RNA was then extracted by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and separated on a 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde gel. RNA was transferred to a Zetabind nylon membrane and probed for transcripts of the genes OP4 (31), SAP3 (16, 65), EFG1 (25, 54, 59), ECE1 (4), HWP1 (57, 58), RBT5 (8), and TUP1 (6) with PCR fragments obtained with the primers OP4 NDE1F/OP4 SPHIR, SAP3F/SAP3R, FANEFG15′/FANEFG13′, ECE1F/ECE1R, HWP1F/HWP1R, RBT5F/RBT5R, and TUPF/TUPR, respectively (Table 2). For genes WH11 and SAP1, previously described PCR products were amplified from plasmids (32, 52). Autoradiography was performed by exposing membranes at −70°C by using intensifying screens to Kodak X-Omat film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Characterization of switching.

Cells from test and control strains were plated at a low density on agar medium containing phloxine B and incubated for 5 days at 25°C. Cells from five colonies exhibiting the dominant colony phenotype were inoculated into a single flask containing 25 ml of supplemented Lee's medium and grown to mid log phase. Cells were then diluted into sterile water, the concentration of the cells was adjusted, and 0.2 ml, containing ca. 60 cells, was spread on each agar plate (11 cm in diameter). After 7 days of incubation at 25°C, colony phenotypes were scored. In a standard experiment, 40 plates were scored, with each containing ca. 50 colonies. In the case of newly transformed strains, cells were transferred to fresh agar plates at least three times prior to analysis.

Photomicroscopy.

For colony morphology, low-density agar cultures grown at 25° for 7 days were photographed by using the macro setting on a Nikon Coolpix 990 digital camera. For cell morphologies, cells were photographed through a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with phase-contrast optics. Images were captured through a microscope-mounted Optronics Cooled CCD camera. Images at ×600 magnification were formatted for publication by using Adobe PhotoShop version 5.5 software.

UV treatment.

To test the effects of UV radiation on switching, cells were grown in liquid medium to a concentration of 107 cells per ml and then plated at a density of 60 CFU per agar plate. Lids were removed, and the plates exposed to UV light emitted from a prewarmed 15-W General Electric germicidal lamp (G15TB) with an emission wavelength of 254 nm. The UV source was placed 16 cm above the cells. Cells were treated for 2 s, resulting in ca. 5 to 15% cell death.

RESULTS

Creating a deletion mutant of TUP1 in strain WO-1.

To create deletion mutants of TUP1 in strain WO-1, we used the “urablaster” protocol of Fonzi and Irwin (14). The TUP1:hisG-URA3-hisG cassette (Fig. 1) was used to transform white-phase cells of the ura3 auxotrophic derivative of strain WO-1, TS3.3 (54). Of 48 transformants tested, 36 were confirmed by Southern analysis to be heterozygous at the TUP1 locus. Southern analysis of total cellular DNA digested with SalI showed that, in control strain TU17, the URA3 derivative of TS3.3, a 1.8- and a 0.8-kb fragment hybridized to the TUP1 probe (Fig. 2). In the heterozygous transformant Thet1, a new 5.8-kb fragment appeared that corresponded to the addition of the 4.0-kb hisG-URA3-hisG cassette (Fig. 2). After a pop-out strategy, in which the transformant Thet1-p1 was selected for loss of the URA3 gene by growth on 5-FOA, the extra band decreased from 5.8 to 2.7 kb, indicating the loss of the URA3 gene and one copy of hisG (Fig. 2). White-phase cells of Thet1-p1 were retransformed with the TUP1:hisG-URA3-hisG cassette. Of 48 transformants, 2 were confirmed to be homozygous TUP1 disruptants by the complete loss of the 1.8- and 0.8-kb bands and the presence of the 5.8- and 2.7-kb bands (Fig. 2). Two resulting homozygotes, Δtup1-1 and Δtup1-2, were chosen for further analysis.

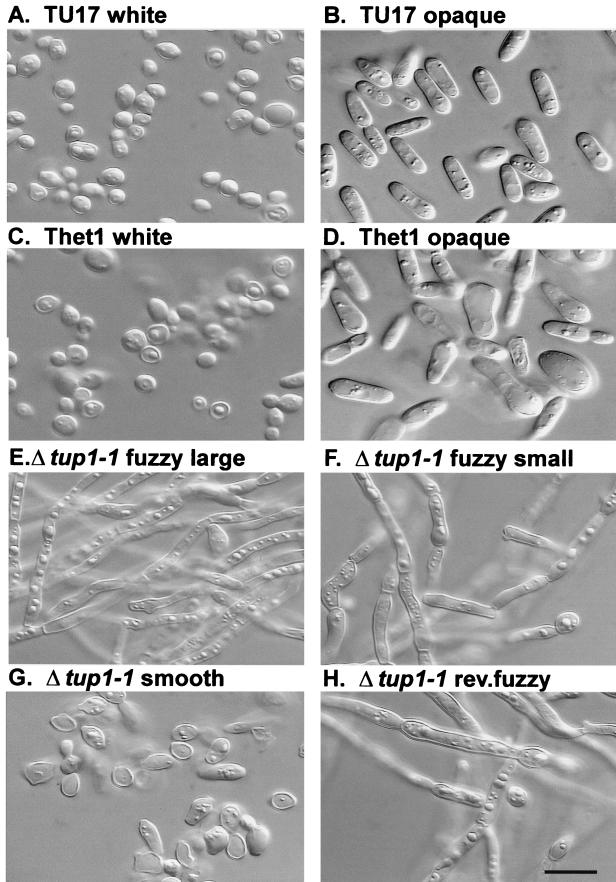

TUP1 mutant cells grow exclusively in the filamentous form.

Braun and Johnson (6) demonstrated that when both copies of TUP1 were deleted in C. albicans CAI4, an auxotrophic derivative of strain SC5314 (14), cells grew exclusively in the filamentous form. To assess the effects of TUP1 deletion on the growth form of strain WO-1, cells of the control strain TU17, the heterozygous deletion mutant Thet1, and the homozygous deletion mutant Δtup1-1 were examined microscopically after growth in liquid medium at 25°C, conditions which support the budding yeast form in wild-type strains. Cells from white- and opaque-phase colonies were examined in the case of strains TU17 and Thet1, and cells from the uniformly fuzzy colony phenotype in the case of Δtup1-1. White-phase cells of TU17 and Thet1 exhibited the round budding phenotype (Fig. 3A and C, respectively) characteristic of that phase in the original parental strain WO-1 (1, 44), and opaque-phase cells of the two strains exhibited the enlarged, elongate, asymmetric phenotype (Fig. 3B and D, receptively) characteristic of that phase in strain WO-1 (1, 44). The opaque-phase cells of strain Thet1 were slightly larger and more irregular than those of strain TU17. In contrast, cells of strain Δtup1-1 grew exclusively in the filamentous form (Fig. 3E), the same result obtained with the homozygous TUP1 deletion mutant of strain CAI4 (6). No individual budding cells were observed in Δtup1-1 cultures (Fig. 3E), even after vortexing, thus supporting the conclusion that growth was primarily in the filamentous form and that separation between cellular compartments did not readily occur. The independently isolated TUP1 homozygous mutant Δtup1-2 exhibited the same filamentous growth phenotype as Δtup1-1 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Cellular phenotypes. (A and B) White- and opaque-phase cells, respectively, of control strain TU17. (C and D) White- and opaque-phase cells, respectively, of the TUP1 heterozygous deletion mutant Thet1. (E) Hyphal phenotype of Δtup1-1 “fuzzy large” colonies. (F) Pseudohyphal phenotype of Δtup1-1 “fuzzy small” colonies. (G) Budding phenotype of Δtup1-1 “smooth” colonies. (H) Pseudohyphal phenotype of Δtup1-1 “revertant fuzzy” colonies. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Switching in ΔTUP1 mutants strains.

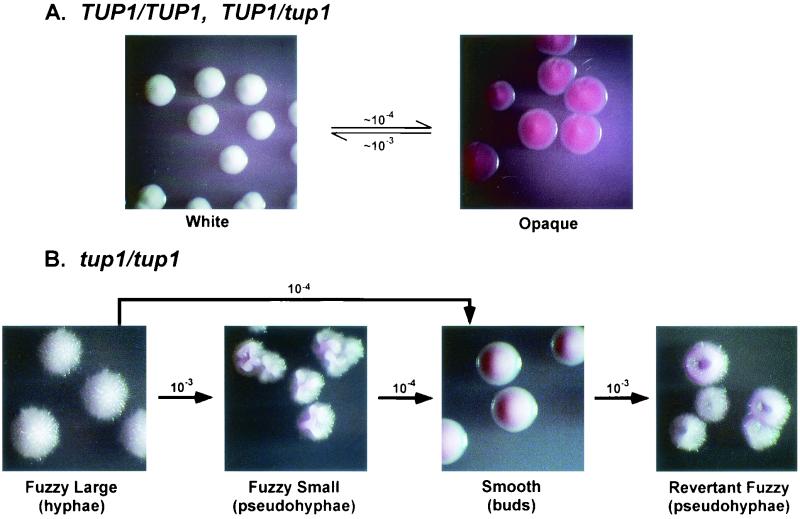

When cells from 5-day-old white-phase colonies of control strain TU17 or the heterozygous deletion mutant Thet1 were plated at low density on agar containing phloxine B, they formed predominately white-phase colonies, which were colored white to light pink (Fig. 4A). When cells from opaque-phase colonies of both strains were plated on agar containing phloxine B, they formed predominately opaque-phase colonies, which were colored red (Fig. 4A). To characterize switching in strain TU17 and Thet1, white-phase and opaque-phase cells from visually homogeneous white- and opaque-phase colonies were grown in liquid medium at 25°C. Cell samples were then plated at low density on agar containing phloxine B, grown for 5 days at 25°C, and assessed for colony phenotype. In five plating experiments of white-phase TU17 cells, the average frequency of opaque CFU was 10−4 (Table 3). In five plating experiments of opaque-phase TU17 cells, the average frequency of white-phase CFU was 3 × 10−3 (Table 3). After 11 days, opaque-phase sectors appeared in white-phase colonies and, to a lesser extent, white-phase sectors in opaque-phase colonies. In one plating experiment of white-phase Thet1, the average frequency of opaque-phase CFU was 3 × 10−4, and in one plating experiment of opaque-phase Thet1, the average frequency of white-phase CFU was <3 × 10−4 (Table 3). After 11 days, opaque-phase sectors appeared in white-phase colonies and, to a lesser extent, white-phase sectors appeared in opaque-phase colonies. Strains TU17 and Thet1, therefore, switched between the white and opaque phases at 25°C in a fashion similar to that of the original strain WO-1 (1, 44).

FIG. 4.

Summary of switching in TU17 (TUP1/TUP1), Thet1 (TUP1/tup1), and Δtup1-1 (tup1/tup1). (A) The white-opaque transition in TU17 and Thet1. Colonies were photographed with direct lighting after 7 days of incubation at 25°C. (B) Unidirectional switching in Δtup1-1. The frequencies along each arrow represent the number of variants (phenotype pointed to) in a population of phenotype from which each arrow emanates. Fuzzy large, fuzzy small, and smooth colonies were photographed with indirect lighting after 11 days incubation at 25°C. Revertant fuzzy colonies were photographed with indirect lighting after 14 days incubation at 25°C.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypic switching in TU17 (TUP1/TUP1), Thet1 (TUP1), and Δtup1-1 (tup1/tup1) strains

| Strain | Genotype | UV treatment | Initial phenotype | No. of expt. | Total no. of colonies | No. of colonies with original phenotype | No. of colonies with variant phenotype | Frequency of variant phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU17 | TUP1/TUP1 | − | White | 5 | 10,523 | 10,522 | 1 opaque | 10−4 |

| Opaque | 5 | 10,205 | 10,176 | 29 white | 3 × 10−3 | |||

| Thet1 | TUP1/tup1 | − | White | 1 | 3,158 | 3,157 | 1 opaque | 3 × 10−4 |

| Opaque | 1 | 3,044 | 3,044 | 0 white | <3 × 10−4 | |||

| Δtup1-1 | tup1/tup1 | − | Fuzzy large | 3 | 5,434 | 5,426 | 6 fuzzy small | 10−3 |

| Δtup1-2 | tup1/tup1 | − | Fuzzy large | 1 | 1,992 | 1,989 | 2 fuzzy small 1 smooth | 2 × 10−3 |

| Δtup1-2 | tup1/tup1 | + | Fuzzy large | 1 | 1,977 | 1,972 | 5 fuzzy small | 3 × 10−3 |

| Δtup1-1 | tup1/tup1 | − | Fuzzy small | 5 | 8,076 | 8,075 | 1 smooth | 10−4 |

| Δtup1-1 | tup1/tup1 | + | Fuzzy small | 1 | 3,294 | 3,274 | 20 smooth | 6 × 10−3 |

| Δtup1-1 | tup1/tup1 | − | Smooth | 1 | 3,214 | 3,212 | 2 revertant fuzzy | 6 × 10−4 |

In three plating experiments of Δtup1-1 and one of Δtup1-2 on agar containing phloxine B, there was no indication of a transition to a bright red colony, nor was there bright red sectoring after prolonged incubation, a characteristic of the white-opaque transition. There did appear, however, a new fuzzy variant phenotype (Fig. 4B), which after 10 days was smaller and more wrinkled than the original fuzzy colony phenotype. Because of the size difference, the original fuzzy colony phenotype of Δtup1 (Fig. 4B) is referred to as “fuzzy large,” whereas the smaller variant fuzzy phenotype (Fig. 4B) is referred to as “fuzzy small.” The fuzzy small phenotype appeared repeatedly at frequencies of 10−3 in Δtup1-1 and of 2 × 10−3 in Δtup1-2 (Table 3). When Δtup1-2 cells were exposed to UV at a dose that killed ca. 5% of the cells and has been demonstrated to stimulate the white-opaque transition in strain WO-1 (30) and switching in strain 3153A (38, 43), the frequency of fuzzy small variants was 3 × 10−3, similar to that of untreated cells (Table 3). Again, no bright red opaque-phase colonies or sectors were observed (Table 3). Cells from the fuzzy small colonies grew exclusively in the pseudohyphal form (Fig. 3F), exhibiting more pronounced constrictions at cell compartment junctions and a slightly less elongate compartment than filaments in fuzzy large colonies (Fig. 3E). In fuzzy small populations, there was a low level of cell separation between compartments, resulting in a minor population of single elongate cells with morphologies superficially similar to those of opaque-phase cells. The fuzzy small variant was confirmed to be a Δtup1 derivative by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2). We also found one case in which fuzzy large switched spontaneously to a “smooth” colony phenotype (Table 3), a morphology which will be discussed in the next section.

Fuzzy small switches in turn to smooth, which grows in the budding yeast form.

To test whether fuzzy small cells switched back to the fuzzy large phenotype, cells from fuzzy small colonies were in turn plated at low density. No fuzzy large morphologies were observed (Table 3), suggesting that either the frequency of the reverse transition was very low (<2 × 10−4) or that the fuzzy small phenotype was irreversible. Although fuzzy small cells did not switch back to the fuzzy large phenotype, they did switch to a “smooth” phenotype, which was superficially similar to the original white-phase colony phenotype in strains TU17 and Thet1 (Fig. 4B). Smooth colonies did, however, exhibit a slightly darker pink color than white-phase colonies. The smooth variant was confirmed to be a Δtup1 derivative by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). The combined results of five plating experiments of Δtup1-1 fuzzy small cells provided an average frequency of 10−4 for the spontaneous switch from fuzzy small to smooth (Table 3). When fuzzy small cells were irradiated with a dose of UV that killed ca. 5% of the population, the frequency of smooth colonies increased to 6 × 10−3, a 16-fold increase (Table 3). Cells in all smooth colonies grew exclusively in the budding yeast growth form (Fig. 3G). This was also true for the single smooth colony obtained in the fuzzy large plating experiment (Table 3). To test whether smooth cells switch back to fuzzy small or fuzzy large, we performed a plating experiment on a smooth clone obtained from fuzzy small colonies. Two revertant fuzzy colonies (Fig. 4B) were obtained at a frequency of 6 × 10−4 (Table 3). Revertant fuzzy colonies, which grew slower than the smooth parent strain, exhibited a phenotype after 10 days that was morphologically distinct from both the small fuzzy and fuzzy large colony phenotypes. Cells in revertant fuzzy colonies grew exclusively in the pseudohyphal form (Fig. 3H), just as did cells in fuzzy small colonies (Fig. 3F).

In large plating experiments of the original fuzzy large phenotype and all subsequent unidirectional switch phenotypes, we observed no indication of the white-opaque transition. More importantly, no opaque-phase colonies were observed in the plating experiment of smooth cells (Table 3). Since smooth colonies (Fig. 4B) appeared superficially similar to white-phase colonies (Fig. 4A) and smooth budding yeast cells (Fig. 3G) appeared superficially similar to budding white-phase yeast cells (Fig. 3A and C), smooth-phase colonies were incubated for 14 days at 25°C, a procedure that results in intense opaque-phase sectoring at the periphery of every wild-type white-phase colony. No opaque-phase sectors were observed, supporting the conclusion that Δtup1 smooth cells do not undergo the white-opaque phase transition. Since all unidirectional switch phenotypes contained URA3 in the disruption cassette, the possibility existed that the unidirectional switch phenotypes could be due to differential expression of orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase, the gene product of URA3. To test this possibility, all unidirectional switch phenotypes were grown on plates containing uridine. All maintained their original colony phenotype, demonstrating that their colony phenotypes were not due to differential expression of the URA3 gene in the URA-hisG cassette.

Unidirectional switching is not the result of gross chromosomal reorganization.

The combined switching results suggest that Δtup1 cells are unable to undergo the white-opaque transition, the dominant phenotypic switching system in both the parent strain TU17 (TUP1/TUP1) cells and the heterozygous strain Thet1 (TUP1/tup1) (Fig. 4A). Δtup1 (tup1/tup1) cells are, however, capable of undergoing spontaneous, unidirectional, high-frequency switching in the sequence fuzzy large (hyphae) → fuzzy small (pseudohyphae) → smooth (budding yeast cells) → reverent fuzzy (pseudohyphae) (Fig. 4B). The frequencies of the unidirectional switches were far higher than that expected for point mutations and, in contrast to phenotypic switching, were not reversible at high frequency. Since C. albicans undergoes chromosomal reorganization at relatively high frequency (27), we compared the karyotypes of TU17 fuzzy large, fuzzy small, smooth, and revertant fuzzy by using contour-clamped homogenous electric field electrophoresis. Of the seven separated bands (27), no variation was observed in any of the tested strains either in band position or intensity (data not shown). These results demonstrate that unidirectional switching is not due to gross chromosomal reorganization.

The level of TUP1 transcript is affected by switching.

Before we assessed the role of Tup1p in the downstream regulation of phase-specific genes, we first assessed the level of TUP1 expression in white- and opaque-phase cells by Northern blot analysis. Densitometric analysis of hybridization bands indicated that the level of the TUP1 transcript was more than fourfold higher in white-phase cells than in opaque-phase cells both in strain TU17 and in strain Thet1 (Fig. 5 and 6). In addition, the levels of the TUP1 transcript in the white and opaque phases of strain Thet1 were roughly half those of the white and opaque phases in strain TU17 (Fig. 5).

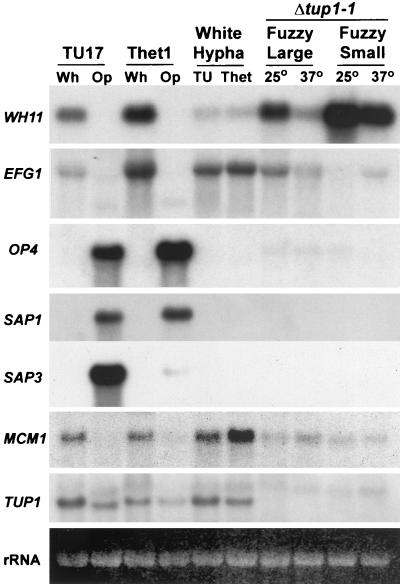

FIG. 5.

Northern analysis of the expression of phase-regulated genes (WH11, EFG1, OP4, SAP1, SAP3, and MCM1) and TUP1 in white (Wh)- and opaque (Op)-phase cells of TU17 and Thet1, white-phase hyphae in TU17 (TU) and Thet1 (Thet), and the “fuzzy large” and “fuzzy small” phenotypes of Δtup1-1 grown at 25 and 37°C. Northern blots were probed with the noted genes. The ethidium bromide-stained 18S rRNA bands are presented at the bottom of the hybridization patterns to demonstrate comparable loading.

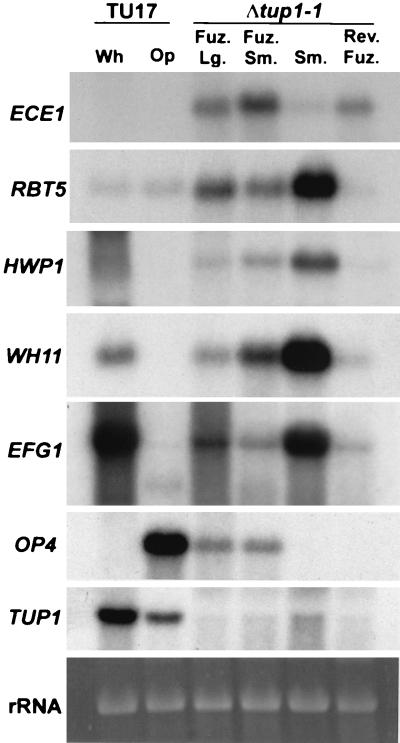

FIG. 6.

Northern analysis of the expression of hypha-associated genes (ECE1, RBT5, and HWP1), phase-specific genes (WH11, EFG1, and OP4), and TUP1 in white (Wh)- and opaque (Op)-phase cells of TU17, and Δtup1-1 fuzzy large (Fuz. Lg.), fuzzy small (Fuz. Sm.), smooth (Sm.), and revertant fuzzy (Rev. Fuz.) cells. RBT5 and HWP1 have been demonstrated to be regulated by TUP1 (7, 39). Northern blots were probed with the noted genes. The ethidium bromide-stained 18S rRNA bands are presented at the bottom of the hybridization patterns to demonstrate comparable loading.

Expression of phase-specific genes in the TUP1 heterozygous deletion mutant Thet1.

The two white-phase-specific genes WH11 (52) and EFG1 (25, 54, 59) and the white-phase-enriched gene MCM1 (56), were differentially expressed in the white phase of strain TU17 and Thet1, and the three opaque phase-specific genes OP4 (31), SAP1 (32), and SAP3 (16, 65) were differentially expressed in the opaque phase of both strains (Fig. 5). There were, however, differences in expressions between TU17 and Thet1. The levels of WH11 and EFG1 transcripts were higher in the white phase of Thet1 than in the white phase of TU17, and the level of the OP4 transcript was higher in the opaque phase of Thet1 than in the opaque phase of TU17 (Fig. 5). The level of the SAP3 transcript was lower in the opaque phase of Thet1 than in the opaque phase of TU17 (Fig. 5). These results, obtained in a repeat experiment, indicate that the level of TUP1 expression affects the levels of select white- and opaque-phase-specific gene expression but not the phase specificity of expression.

In both TU17 and Thet1, hypha formation was induced by diluting white budding phase cells into serum-containing medium and incubating the cultures for 6 h. The white-phase-specific gene WH11 was downregulated in both TU17 and Thet1 hyphae (Fig. 5), as previously reported for original strain WO-1 (52, 53). The levels of the EFG1 and MCM1 transcripts were slightly higher in Thet1 hyphae (Fig. 5). None of the opaque-phase-specific genes (OP4, SAP1, and SAP3) were expressed in the hyphae formed by white-phase cells of either strain (Fig. 5). Finally, TUP1 was expressed in hyphae of both strains, but the level of transcript in Thet1 hyphae was lower than that in TU17 hyphae, as was the case in white budding cells (Fig. 5). These results were obtained in repeat experiments.

Expression of phase-specific genes in Δtup1 mutant cells.

Because the phase-specific activation sequence of the OP4 promoter includes a MADS box consensus binding site with homology to the S. cerevisiae Mcm1p binding site (26) and is bordered immediately upstream by an α2-like binding site (49), we entertained the possibility that Tup1p was involved in the repression of OP4 expression, since α2-Mcm1p recruits the Tup1p-Ssn6p corepressor complex in S. cerevisiae (11, 15, 22). Northern analysis demonstrated, however, that although homozygous deletion of TUP1 did not completely derepress OP4 expression to the levels of opaque-phase cells, OP4 was expressed at very low levels in fuzzy large and fuzzy small cells (Fig. 5 and 6). Deletion of TUP1 did not derepress SAP3 (Fig. 5), which also contains a MADS box consensus binding site in its promoter (S. Lockhart and D. R. Soll, unpublished observations). Δtup1 fuzzy large, which grew exclusively in the filamentous form, exhibited a general pattern of phase-specific gene expression similar to that of white-phase cells of the control strain TU17 and the heterozygote Thet1 (Fig. 5). Δtup1 cells expressed the white-phase-specific genes WH11, EFG1, and MCM1 at significant levels, and expressed OP4, SAP1, and SAP3 at very low or undetectable levels (Fig. 5). In addition, downregulation of WH11 expression at 37°C, which was demonstrated previously in control strain TU17 (54, 56), also occurred in Δtup1 at 37°C (Fig. 5). These results suggest that the differential expression of OP4 in the opaque phase is not regulated solely by Tup1p-mediated repression in the white phase, reinforcing the conclusion from the functional characterization of the OP4 promoter that regulation is primarily through opaque-phase-specific gene activation (26). The results also demonstrate that fuzzy large filamentous cells exhibit a pattern of gene expression similar to that of white-phase cells.

Transcript levels of phase-specific genes are altered in the fuzzy small variant.

The cellular phenotype of the fuzzy small variant, which appeared spontaneously and after UV irradiation in populations of Δtup1 fuzzy large, was pseudohyphal (Fig. 3F), and a minority of detached cells had shapes similar to those of opaque-phase cells. However, just as in the case of large fuzzy cells, none of the opaque-phase-specific genes (OP4, SAP1, and SAP3) were activated in fuzzy small cells (Fig. 5). The levels of select phase-specific genes were, however, altered. While the level of the WH11 transcript increased severalfold, the level of EFG1 transcript decreased to a negligible level at 25°C and to a reduced level at 37°C (Fig. 5). No major differences were observed in the transcript levels of MCM1 between fuzzy large and fuzzy small (Fig. 5).

Expression of hypha-associated and Tup1p-regulated genes.

We also assessed the levels of expression of three genes associated with hypha formation: ECE1, the expression of which has been demonstrated to correlate with the degree of cell compartment elongation (4); RBT5, a GPI-modified cell wall protein which is differentially expressed in the hyphal growth form and has been reported to be under TUP1 regulation (8); and HWP1, which encodes a surface adhesin (57, 58) demonstrated to be regulated by Tup1p (42). ECE1 was not expressed in either the white or opaque phases of TU17 but was expressed in fuzzy large, fuzzy small, and revertant fuzzy cells (Fig. 6). Expression was greater in fuzzy small than in fuzzy large cells. ECE1 was expressed at a negligible level in smooth (Fig. 6). Therefore, the expression of ECE1 correlated with filamentous growth.

Expression of neither RBT5 nor HWP1, however, remained associated with filamentous growth in the switching lineage. RBT5 was expressed at a low level and HWP1 at an undetectable level in white- and opaque-phase budding cells (Fig. 6). Both were expressed at various levels in the fuzzy large, fuzzy small, and smooth phenotypes but at negligible levels in the revertant fuzzy phenotype in the unidirectional switch phenotypes (Fig. 6). Surprisingly, the patterns of WH11 and EFG1 expression, i.e., lower in the fuzzy large and fuzzy small phenotype than the smooth phenotype and very low to negligible in the revertant fuzzy phenotype, were roughly similar to those of RBT5 and HWP1 (Fig. 6). These results suggest that RBT5, HWP1, WH11, and EFG1 may be coordinately regulated in the unidirectional switching lineage of Δtup1, although small differences in the relative intensities between switch phenotypes do exist. Furthermore, it should be noted that both HWP1 and RBT5, the expression of which have been reported associated with the filamentous growth form (8, 40, 57, 58), were expressed most intensely in Δtup1 smooth cells, which grew exclusively in the yeast form (Fig. 3G), and that both genes were downregulated in revertant fuzzy cells, which grew exclusively in the filamentous form (Fig. 3H). These results demonstrate that while the unidirectional switch phenotypes exhibit the general gene expression pattern of white-phase cells, the phase of the original transformed cell lines, all of the switch phenotypes differ in the expression of at least one tested gene.

Rescued Δtup1 cells undergo the white-opaque transition.

To confirm that the Δtup1 mutant phenotype was due to the homozygous disruption of TUP1 and not to a second site mutation and to test whether changes in the unidirectional switching system affected the capacity of cells to undergo the white-opaque transition, we rescued both the fuzzy large and the smooth phenotypes of Δtup1 with a single copy of the TUP1 gene under the control of the MET3 promoter in the plasmid pCET1. Integration was targeted to the RP10 locus. In this configuration, a gene is expressed in the absence and repressed in the presence of methionine (11). Positive transformants were selected on minimal medium plates lacking methionine and uridine and were distinguishable by colony morphology, since they reverted from the fuzzy large and smooth colony phenotypes that did not sector, respectively, to a smooth colony phenotype which underwent sectoring. In both cases, the original transformed clones formed primarily opaque colonies that then formed white sectors. Rescued strains were confirmed by Southern analysis (data not shown). Cells of rescued strains from both the fuzzy large phenotype, Δtup1-1res1, and from the smooth phenotype, Δtup1-1res2, grew in the budding yeast growth form in minimal medium and in supplemented Lee's medium lacking methionine (data not shown). When replated on agar containing either growth medium, cells from both rescued strains formed opaque- and white-phase colonies and continued to switch between the white and opaque phases at relatively normal frequencies (∼10−3), exhibiting white budding yeast cells in the former colonies and opaque budding yeast cells in the latter colonies that were indistinguishable from white and opaque budding yeast cells of strains TU17, Thet1, or WO-1. These results demonstrate that the Δtup1 mutant phenotype was due solely to the homozygous disruption of TUP1. They further demonstrate that the presumed genetic changes involved in unidirectional switching from fuzzy large to fuzzy small to smooth have no effect on the white-opaque transition when TUP1 expression is reestablished.

Testing phase memory in the absence of TUP1 expression.

By placing TUP1 under the control of an inducible promoter in a rescued strain, we were able to test whether white-phase cells and opaque-phase cells maintained their respective identities when grown in the filamentous form after downregulation of TUP1 expression. In the experimental protocol, white- and opaque-phase cells of strain Δtup1-1res1 were first plated at low density on agar lacking methionine, conditions that support TUP1 expression and the white-opaque transition. Cells from white-phase colonies and cells from opaque-phase colonies were then individually grown in liquid medium lacking methionine for 48 h, checked microscopically for cellular homogeneity, and plated at low density on agar medium containing methionine, conditions that downregulate TUP1 expression, resulting in exclusive filamentous growth. After 5 days, colonies were either replicate plated on agar medium lacking methionine, or cells from individual colonies were plated at low density on agar medium lacking methionine for 5 days, in both cases resulting in TUP1 reexpression. If cells maintained their original phase identity (white or opaque) during the period that TUP1 expression was downregulated, then originally white-phase cells would exhibit the white-phase phenotype, and originally opaque-phase cells would exhibit the opaque-phase phenotype when TUP1 was reexpressed. If one or both original phenotypes lost identity when TUP1 expression was downregulated and then reverted to an alternative phenotype when TUP1 was reexpressed, then all of the originally white-phase cells and all of the originally opaque-phase cells would exhibit only one of the alternative phenotypes (i.e., white or opaque) when TUP1 was reexpressed. If one or both phenotypes lost identity when TUP1 expression was downregulated, then randomized their phenotype, the final proportions upon TUP1 reexpression would be 50:50 for one or both. In both the replicate plating protocol and the single cell plating protocol, the results were similar. When TUP1 was downregulated and then upregulated, both the majority of originally white-phase cells and the majority of originally opaque-phase cells expressed the opaque-phase phenotype (Table 4). In both cases the cells then switched at normal frequencies to white, and the reversible white-opaque transition was reestablished. Since addition of methionine was used to downregulate TUP1, and subsequent removal was used to again upregulate it, the possibility existed that these manipulations independent of TUP1 expression affected switching and mass conversion. To test this possibility, white- and opaque-phase cells of control strain TU17 were transferred from medium containing methionine to medium lacking methionine, which caused mass conversion from white to opaque in strain Δtup1-1res1. The transfer had no effect on established phenotypes or switching frequency (data not shown), suggesting that the effects observed in Δtup1-1res1 were TUP1 mediated.

TABLE 4.

Stability of phase identity after downregulation of TUP1 in Δtup1-1res1, in which TUP1 is under control of the inducible MET3 promotera

| Expt protocol | Expt no. | Original phenotypeb | After reexpression of TUP1

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of colonies | Proportion white (%) | Proportion opaque (%) | |||

| Replica plate | 1 | White | 824 | 10 | 90 |

| Opaque | 463 | 3 | 97 | ||

| Dilute plate | 1 | White | 484 | 11 | 89 |

| Opaque | 427 | 0 | 100 | ||

| 2 | White | 625 | 4 | 96 | |

| Opaque | 608 | 1 | 99 | ||

In the last step of the protocol for the phase memory experiment, cells were either replica plated or diluted and plated onto agar lacking methionine to induce the reexpression of TUP1.

For both experiments 1 and 2, the original white and opaque cultures were >98% white and opaque, respectively.

Mass conversion to opaque occurs upon upregulation of TUP1.

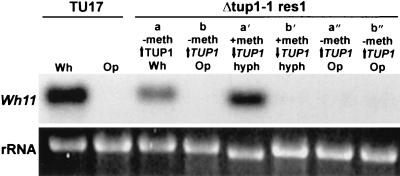

The preceding results suggest that either at the time TUP1 expression is downregulated or at the time TUP1 expression is upregulated, white-phase cells switch en masse to the opaque phase. To distinguish between these alternatives, we analyzed the expression of the white-phase-specific gene WH11 by Northern analysis. If white-phase cells converted to opaque immediately after TUP1 was downregulated, then the expression of WH11 would be repressed in cultures of white-phase cells which had been transferred from medium lacking methionine to medium containing methionine and would remain repressed in opaque-phase cultures treated in the same manner. Alternatively, if cells retained white-phase identity after TUP1 was downregulated, and mass converted to opaque only after TUP1 was again upregulated, then WH11 would continue to be expressed after TUP1 downregulation in originally white-phase cells and would be repressed only after TUP1 was upregulated. In this latter scenario, WH11 would remain repressed in opaque-phase cultures after TUP1 downregulation and after TUP1 was upregulated. The latter result was obtained. At 48 h after TUP1 downregulation in white-phase cell cultures, the majority of cells were filamentous, WH11 continued to be expressed, and at 48 h after subsequent TUP1 upregulation, WH11 was repressed (Fig. 7). Opaque-phase cells did not express WH11 through the protocol (Fig. 7). In the case of the opaque-phase-specific gene OP4, expression remained repressed in white-phase cells after TUP1 downregulation and was upregulated after TUP1 upregulation; opaque-phase cells continued to express OP4 through the entire protocol (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that white-phase and opaque-phase cells retain their respective phase-specific gene expression patterns and hence their phase identity after TUP1 is downregulated and that mass conversion of white-phase cells to the opaque phase occurs when TUP1 is again upregulated.

FIG. 7.

Northern analysis of the expression of the white phase-specific gene WH11 in the white (Wh) and opaque (Op) phases of parental strain TU17, in the white (Wh) and opaque (Op) phases of the rescued strain Δtup1-1res1 grown in the absence of methionine, which upregulates TUP1 (a, b), in hyphae of the large fuzzy phenotype of original white- and original opaque-phase cells transferred to medium containing methionine, which downregulates TUP1 (a′, b′), and after the hyphae from original white- and opaque-phase cultures were transferred to medium lacking methionine, which again upregulates TUP1 (a″, b″).

DISCUSSION

The Tup1p-Ssn6p corepressor complex is one of the most pervasive transcriptional repressors in S. cerevisiae. It affects the levels of expression of ca. 180 genes (13) and plays a fundamental role in regulating a-specific genes in a cell-type-specific fashion (12, 15, 23). It does not bind DNA directly but rather is recruited to specific genes by sets of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins (19, 61). The role of Tup1p and related proteins in the developmental biology of C. albicans has, therefore, become a topic of intense investigation. Braun and Johnson (6) first demonstrated that deletion of TUP1 resulted in exclusive filamentous growth, suggesting that Tup1p plays a role in the repression of genes necessary for hypha formation. In addition, the deletion of homologues of genes encoding proteins that interact with the Tup1p-Ssn6p complex in S. cerevisiae results in mutant phenotypes similar to the TUP1 deletion strain of C. albicans (9, 20, 34). We demonstrate here that in addition to its emerging role(s) in the regulation of the bud-hypha transition, TUP1 plays a major role in high-frequency phenotypic switching.

TUP1 may be necessary for the white-opaque transition.

As first demonstrated by Braun and Johnson (6) in C. albicans CAI4, deletion of TUP1 in strain WO-1 results in exclusive filamentous growth. Plating experiments of the TUP1 deletion mutant revealed no transition between a white phase and an opaque phase that could be discriminated by coloration on phloxine B-containing agar plates. UV irradiation, which stimulated the white-opaque transition (30), did not stimulate white-opaque switching as discriminated by coloration or cellular phenotype on phloxine B-containing agar. More importantly, the smooth variant of Δtup1, which grows in a yeast form similar to that of white-phase cells, did not undergo the white-opaque transition as evidenced by the absence of opaque sectors in aged colonies. It should be noted that, although several mutations have been demonstrated to affect the frequency of switching, including deletion mutants of HDA1 (21, 56), RPD3 (56), and CaNIK1 (55) and misexpression of WH11 in the opaque phase (23), deletion of TUP1 represents the first mutation that apparently shuts down the white-opaque transition. However, this interpretation must be tempered by the possibility that the block in the switching process may occur either in the basic switch event or downstream in the expression of the opaque-phase phenotype.

The original Δtup1-1 mutant expresses a white-phase like pattern of gene expression.

Since opaque-phase budding yeast cells express at least two hypha-specific surface antigens (2) and are elongate (1, 44), like pseudopod compartments (28), we entertained the possibility that the filamentous cells of the original Δtup1 mutant strains would express an opaque-phase pattern of gene expression. In fact, we found that the Δtup1 mutant exhibit a pattern of gene expression similar to that of white-phase cells. Since the auxotrophic strain used to generate the original Δtup1 mutants was in the white phase, these results imply that the cells maintained their original white-phase identity. Since a binding sequence similar to the Mcm1p consensus binding site in S. cerevisiae was identified in the activation regions of the promoters of the opaque-phase-specific genes OP4 (26) and SAP3 (48), we also expected to find that deletion of TUP1 would result in constitutive expression of OP4 and SAP3. Instead, we found that OP4 was expressed at very low levels in Δtup1 fuzzy large and fuzzy small cells and at undetectable levels in Δtup1 smooth and revertant fuzzy cells and that SAP3 was not expressed in either Δtup1 fuzzy large or fuzzy small cells.

Δtup1 mutant cells “switch” unidirectionally through a lineage of variant phenotypes.

We have found that the original Δtup1 fuzzy large cell switches unidirectionally through the following sequence of colony phenotypes (and cell morphologies): fuzzy large (hyphae) → fuzzy small (pseudohyphae) → smooth (budding cells) → revertant fuzzy (pseudohyphae). The apparent unidirectionality of the switches suggests that they represent mutations, but their high frequencies (∼10−3) and reproducibility suggest that they do not represent random point mutations. The frequency at which these variants appear and the characteristic of unidirectionality is consistent with the process of mitotic recombination (64). However, an explanation for the reproducible sequence of variant phenotypes is not immediately obvious. Biochemical support for the distinctiveness of the four phenotypes in this unidirectional lineage was obtained in Northern analyses of gene expression. Each switch phenotype differed from the other three in the expression of one or more phase-specific, phase-enriched, or hypha-associated genes. For instance, fuzzy small differed from fuzzy large and revertant fuzzy in the level of expression of HWP1 and from smooth in the level of expression of ECE1; smooth differed from the other three phenotypes in the level of expression of ECE1; and revertant fuzzy differed from the other three in the levels of expression of WH11, RBT5, and HWP1.

To test whether unidirectional switching affected the capacity to undergo the white-opaque transition, we rescued Δtup1 cells expressing the fuzzy large phenotype and Δtup1 cells expressing the smooth phenotype. In both rescued strains, cells switched between the white and opaque phases at frequencies similar to those of strains WO-1 and TU17, demonstrating that the presumed genetic change(s) involved in the switch from the fuzzy large to fuzzy small and fuzzy small to smooth had no effect on the white-opaque transition. These results suggest that the white-opaque transition and the unidirectional switching system uncovered in Δtup1 mutants are distinct.

TUP1 and the maintenance of phase identity.

By rescuing a Δtup1 deletion mutant with TUP1 under the control of the inducible MET3 promoter, we were able to perform a unique experiment that tested the role of TUP1 in the maintenance of phase-specific gene expression and phase identity. By downregulating TUP1 in individual white-phase and opaque-phase cultures, growing cells for many generations in the filamentous growth form in the absence of TUP1 expression, and then upregulating TUP1 again, we in essence tested whether white- and opaque-phase cells “remembered” their original identity in the absence of TUP1 expression. We found that when TUP1 was reexpressed, white-phase cells switched to opaque and that opaque-phase cells remained opaque, suggesting that reinitiation of the switching system occurs through the opaque phase. To assess when white-phase cells mass converted to the opaque phase, we used expression of the white-phase-specific gene WH11 as a white-phase marker. First, we found that after TUP1 downregulation, filamentous cells emanating from white-phase cells continued to express WH11, and filamentous cells emanating from opaque-phase cells continued to downregulate WH11. These results demonstrated that the phase-specific pattern of gene expression, and by extrapolation the phase identity, is maintained in the absence of TUP1 expression. Second, we found that WH11 expression terminated only when TUP1 was upregulated, suggesting that mass conversion to the opaque phase occurred only after TUP1 was reexpressed.

Possible mechanism of TUP1 in the regulation of switching.

In S. cerevisiae, TUP1 is a component of a repressor complex recruited by DNA-binding proteins to suppress gene expression, and we assume that in C. albicans its function is similar. Recently, Watson et al. (63) demonstrated that the recruited Ssn6p-Tup1p complex could interact with a class I deacetylase complex. These authors suggested that the Ssn6p-Tup1p complex may recruit deacetylase complexes to a nucleosome adjacent to the regulated gene. Wu et al. (66) have shown that TUP1 can interact directly with Hda1p, and Bone and Roth (5) have shown that recruitment of the Tup1p-Ssn6p repressor complex results in localized deactylation of histone H3 and H4. Recently, we demonstrated that the deacetylase Hda1p plays a selective role in suppressing the white-to-opaque transition but not the opaque-to-white transition and that the deacetylase Rpd3p plays a role in suppressing switching in both the white-to-opaque and opaque-to-white directions (21, 56). It has been suggested that switching involves a metastable change in chromatin structure at one or more switching loci (45, 48, 49) and that these chromatin states involve deacetylation (21, 36). Although one might suggest that the role of TUP1 in switching may be to suppress expression of one or more genes involved in the switch event(s) through the recruitment of deacetylase complexes, the phenotypes of the TUP1 mutant and the deacetylase mutants (21, 36, 56) do not support such a straightforward model. The deletion of the deacetylases upregulate switching, while the deletion of TUP1 appears to suppress switching. More importantly, these results obtained in the experimental regime in which TUP1 expression was first downregulated and then upregulated in strain Δtup1-1res1 suggest that when the switching system is reinitiated through reexpression of TUP1, the start point is opaque. Therefore, the key to understanding the role of TUP1 in switching may be through the mass conversion event stimulated by the reexpression of TUP1 in strain Δtup1-1res1. The reexpression of TUP1 sets the switching system to the opaque phase, which in turn results in the reestablishment of the reversible transition. Tup1p must be recruited in a complex to a site at which it sets the switching system. This may be the site of the switch event or an upstream gene that regulates the switch event. We will, therefore, employ the experimental regime of resetting the switching process by TUP1 upregulation in identifying the DNA-binding protein that recruits the Tup1p complex, the site of Tup1p regulation, and ultimately the master switch locus.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Srikantha and Deborah Wessels for their help in portions of this work.

This research was supported by NIH grant AI2392 to D.R.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, J. M., and D. R. Soll. 1987. Unique phenotype of opaque cells in the “white-opaque transition” of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 169:5579-5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, J., R. Mihalik, and D. R. Soll. 1990. Ultrastructure and antigenicity of the unique cell wall pimple of the Candida opaque phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 172:224-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedell, G. W., and D. R. Soll. 1979. Effects of low concentrations of zinc on the growth and dimorphism of Candida albicans: evidence for zinc-resistant and -sensitive pathways for mycelium formation. Infect. Immun. 26:348-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birse, C. E., M. Y. Irwin, W. A. Fonzi, and P. S. Sypherd. 1993. Cloning and characterization of ECE1, a gene expressed in association with cell elongation of the dimorphic pathogen Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 61:3648-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone, J. R., and S. Y. Roth. 2001. Recruitment of the yeast Tup1p-Ssn6p repressor is associated with localized decreases in histone deacetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1808-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun, B. R., and A. D. Johnson. 1997. Control of filament formation in Candida albicans by the transcriptional repressor TUP1. Science 277:105-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, B. R., and A. D. Johnson. 2000. TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics 155:57-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, B. R., W. S. Head, M. X. Wang, and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Identification and characterization of TUP1-regulated genes in Candida albicans. Genetics 156:31-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun, B. R., D. Kadosh, and A. D. Johnson. 2001. NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth in C. albicans, is downregulated during filament induction. EMBO J. 20:4753-4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, A. J., and N. A. Gow. 1999. Regulatory networks controlling Candida albicans morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 7:333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Care, R. S., J. Trevethick, K. M. Binley, and P. E. Sudbery. 1999. The MET3 promoter: a new tool for Candida albicans molecular genetics. Mol. Microbiol. 34:792-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper, J. P., S. Y. Roth, and R. T. Simpson. 1994. The global transcriptional regulators, SSN6 and TUP1, play distinct roles in the establishment of a repressive chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 8:1400-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeRisi, J. L., V. R. Iyer, and P. O. Brown. 1997. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science 278:680-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herschbach, B. M., M. B. Arnaud, and A. D. Johnson. 1994. Transcriptional repression directed by the yeast alpha 2 protein in vitro. Nature 370:309-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hube, B., M. Monod, D. Schofield, A. Brown, and N. Gow. 1994. Expression of seven members of the gene family encoding aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 14:87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hull, C. M., and A. D. Johnson. 1999. Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science 285:1271-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imai, S., C. M. Armstrong, M. Kaeberlein, and L. Guarente. 2000. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403:795-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keleher, C. A., M. J. Redd, J. Schultz, M. Carlson, and A. D. Johnson. 1992. Ssn6-Tup1 is a general repressor of transcription in yeast. Cell 68:708-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalaf, R. A., and R. S. Zitomer. 2001. The DNA binding protein Rfg1 is a repressor of filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics 157:1503-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klar, A., T. Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 2001. A histone deacetylation inhibitor and mutant promote colony-type switching of the human pathogen Candida albicans. Genetics 158:919-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komachi, K., M. J. Redd, and A. D. Johnson. 1994. The WD repeats of Tup1 interact with the homeo domain protein alpha 2. Genes Dev. 8:2857-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kvaal, C. A., T. Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 1997. Misexpression of the white phase-specific gene WH11 in the opaque phase of Candida albicans affects switching and virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:4468-4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lachke, S. A., T. Srikantha, L. K. Tsai, K. Daniels, and D. R. Soll. 2000. Phenotypic switching in Candida glabrata involves phase-specific regulation of the metallothionein gene MT-II and the newly discovered hemolysin gene HLP. Infect. Immun. 68:884-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo, H.-J., J. R. Kohler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutations are a virulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockhart, S. R., M. Nguyen, T. Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 1998. A MADS box protein consensus binding site is necessary and sufficient for activation of the opaque-phase specific gene OP4 of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 180:6607-6616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magee, P. T., and K. Chibana. 2001. The genomes of Candida albicans and other Candida species, p. 293-304. In R. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. American Society of Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Merson-Davies, L. A., and F. C. Odds. 1989. A morphology index for characterization of cell shape in Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:3143-3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell, A. 1998. Dimorphism and virulence in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:687-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow, B., J. Anderson, E. Wilson, and D. R. Soll. 1989. Bidirectional stimulation of the white-opaque transition of Candida albicans by ultraviolet irradiation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:1201-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow, B., T. Srikantha, J. Anderson, and D. R. Soll. 1993. Coordinate regulation of two opaque-phase-specific genes during white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 61:1823-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrow, B., T. Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 1992. Transcription of the gene for a pepsinogen, PEP1, is regulated by white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2997-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrow, B., H. Ramsey, and D. R. Soll. 1994. Regulation of phase-specific genes in the more general switching system of Candida albicans strain 3153A. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 32:287-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murad, A., A. Munir, P. Leng, M. Straffon, J. Wishart, S. Macaskill, D. MacCullum, N. Schnell, D. Talibi, D. Marechal, F. Tekaia, C. d'Enfert, C. Gaillardin, F. C. Odds, and A. J. P. Brown. 2001. NRG1 represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis and hypha-specific gene expression in Candida albicans. EMBO. J. 20:4742-4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odds, F. C. 1997. Switch of phenotype as an escape mechanism of the intruder. Mycoses 40:S9-S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Martin, J., J. A. Uria, and A. D. Johnson. 1999. Phenotypic switching in Candida albicans is controlled by a SIR2 gene. EMBO J. 18:2580-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pomes, R., C. Gil, and C. Nombela. 1985. Genetic analysis of Candida albicans morphological mutants. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:2107-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsey, H., B. Morrow, and D. R. Soll. 1994. An increase in switching frequency correlates with an increase in recombination of the ribosomal chromosomes of Candida albicans strain 3153A. Microbiology 140:1525-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rikkerink, E. H. A., B. B. Magee, and P. T. Magee. 1988. Opaque-white phenotype transition: a programmed morphological transition in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 170:895-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scherer, S., and D. A. Stevens. 1987. Application of DNA typing methods to epidemiology and taxonomy of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:675-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiestl, R. H., and R. D. Gietz. 1989. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr. Genet. 16:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharkey, L. l., M. D. McNemar, S. M. Saporito-Irwin, P. S. Sypherd, and W. A. Fonzi. 1999. HWP1 functions in the morphological development of Candida albicans downstream of EFG1, TUP1, and RBF1. J. Bacteriol. 181:5273-5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slutsky, B., J. Buffo, and D. R. Soll. 1985. High-frequency switching of colony morphology in Candida albicans. Science 42:666-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slutsky, B., M. Staebell, J. Anderson, L. Risen, M. Pfaller, and D. R. Soll. 1987. “White-opaque transition”: a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 169:189-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soll, D. R. 1992. High-frequency switching in Candida albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5:183-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soll, D. R. 1992. Switching and its possible role in Candida pathogenesis, p. 156-172. In J. E. Bennett, R. J. Hay, and P. K. Peterson (ed.), New strategies in fungal disease. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

- 47.Soll, D. R. 1997. Gene regulation during high-frequency switching in Candida albicans. Microbiology 143:279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soll, D. R. 2001. The molecular biology of switching in Candida, p. 161-182. In R. Cihlar and R. Calderone (ed.), Fungal pathogenesis: principles and clinical application. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 49.Soll, D. R. 2001. Phenotypic switching, p. 123-142. In R. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 50.Soll, D. R., J. Anderson, and M. Bergen. 1991. The developmental biology of the white-opaque transition in Candida albicans, p. 20-45. In R. Prasad (ed.), Candida albicans: cellular and molecular biology. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 51.Srikantha, T., A. Chandrasekhar, and D. R. Soll. 1995. Functional analysis of the promoter of the phase-specific WH11 gene of Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:1797-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srikantha, T., and D. R. Soll. 1993. A white-specific gene in the white-opaque switching system of Candida albicans. Gene 131:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srikantha, T., L. K. Tsai, and D. R. Soll. 1997. The WH11 gene of Candida albicans is regulated in two distinct developmental programs through the same transcription activation sequences. J. Bacteriol. 179:3837-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srikantha, T., L. Tsai, K. Daniels, and D. R. Soll. 2000. EFGI null mutant of Candida albicans can switch, but cannot suppress the complete phenotype of white budding cells. J. Bacteriol. 182:1580-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srikantha, T., L. Tsai, K. Daniels, L. Enger, K. Highley, and D. R. Soll. 1998. The two-component hybrid kinase regulator CaNIK1 of Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:2715-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Srikantha, T., L. Tsai, K. Daniels, A. Klar, and D. R. Soll. 2001. The deacetylases HDA1 and RPD3 play complex roles both in switching and phase-specific gene regulation in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 183:4614-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staab, J. F., C. A. Ferrer, and P. Sundstrom. 1996. Developmental expression of a tandemly repeated, proline- and glutamine-rich amino acid motif on hyphal surfaces of Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6298-6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Staab, J. F., S. D. Bradway, P. I. Fidel, and P. Sundstrom. 1999. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of Candida albicans HWP1. Science 283:1535-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stoldt, V. R., A. Sonneborn, C. E. Leuker, and J. F. Ernst. 1997. Efg1p, and essential regulator of morphogenics of the human pathogen Candida albicans is a member of a conserved class of bHCH proteins regulating morphogenetic processes in fungi. EMBO J. 16:1982-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treitel, M. A., and M. Carlson. 1995. Repression by SSN6-TUP1 is directed by MIG1, a repressor/activator protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3132-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzamarias, D., and K. Struhl. 1994. Functional dissection of the yeast Cyc8-Tup1 transcriptional corepressor complex. Nature 369:758-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzung, K.-W., R. M. Williams, S. Scherer, N. Federspiel, T. Jones, C. Komp, R. Surzycki., R. Tamse, R. W. Davis, and N. Agabian. 2001. Genomic evidence for a complete sexual cycle in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:3249-3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watson, A. D., D. G. Edmondson, J. R. Bone, Y. Mukai, Y. Yu, W. Du, D. J. Stillman, and S. Y. Roth. 2000. Ssn6-Tup1 interacts with class I histone deacetylases required for repression. Genes Dev. 14:2737-2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whalen, W. L., and D. R. Soll. 1982. Mitotic recombination in Candida albicans: recessive lethal alleles linked to a gene required for methionine biosynthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 187:477-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White, T. C., S. H. Miyasaki, and N. Agabian. 1993. Three distinct secreted aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 175:6126-6135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu, J., N. Suka, M. Carlson, and M. Grunstein. 2001. TUP1 utilizes histone H3/H2B-specific H DA1 deacetylase to repress gene activity in yeast. Mol. Cell 7:117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]