Abstract

Background

Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma (SHCC) is a rare subtype of primary liver malignancies and is still ill-defined and poorly understood. Therefore, our study was performed to have a comprehensive evaluation SHCC versus conventional hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

A thorough database searching was performed in PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library. RevMan5.3 and Stata 13.0 software were used for statistical analyses. The primary endpoint of our analysis is the long-term survival and the secondary endpoint is clinical and pathological features.

Results

Four studies with a relative large cohort were finally identified. Compared with patients with pure HCC, patients with SHCC had a significantly worse overall survival (P < 0.00001) and disease-free survival (P < 0.0001). Moreover, a larger tumor size (P = 0.003), a higher incidence of node metastasis (P < 0.00001) and a higher proportion of advanced lesions (P = 0.04) were more frequently detected in patients with SHCC. Higher levels of serum ALT (P = 0.02) and TB (P = 0.005) were detected in patients with HCC rather than SHCC, while serum ALB (P = 0.02) level was relatively higher in patients with SHCC. For other measured outcomes, including concurrent viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, liver storage (Child A/B), multifocal tumors, vascular invasion and preoperative AFP level, the results showed no significant difference (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

SHCC has a worse prognosis and exhibits more aggressively than conventional HCC. Future large well-designed studies are demanded for further validation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-022-03949-8.

Keywords: Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Prognosis

Introduction

Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma (SHCC) is a rare subtype of primary liver malignancies with a reported incidence ranging from 1.7 to 1.9% among post-surgical cases with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and a reported incidence ranging from 3.9 to 9.4% among autopsied HCC patients (Maeda et al. 1996; Kojiro et al. 1989; Lu et al. 2015; Kakizoe et al. 1987; Yamaguchi et al. 1997; Watanabe et al. 1994). SHCC shares unusual histopathological features compared with conventional HCC that it contains sarcomatous components, within which spindle-shaped cells are frequently detected, and often manifests as a partial storiform pattern. Moreover, its carcinomatous components generally comprise of poorly or undifferentiated HCC cells (Edmondson–Steiner grade III or IV) (Maeda et al. 1996; Hwang et al. 2008). Currently, the pathogenesis of SHCC remains debating. Some cases accounted it for the necrosis and degeneration after repeated nonsurgical modalities (Kojiro et al. 1989) while others reported the opposite observations that patients without receiving nonsurgical anticancer therapies may also develop SHCC (Yokomizo et al. 2007).

Owing to its rarity, the majority of published literature regarding SHCC are case reports (Numbere et al. 2020; Zhu et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2017; Xue et al. 2013) and its clinical-pathological features, prognosis as well as its optimal therapeutic treatments, especially when it is compared with the most frequently-detected HCC, remains controversial. Although three latest published retrospective comparative studies between SHCC and HCC with a relative larger cohort (Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2019) have focused on their similarities and differences, the sample size and the deficiency of a comprehensive evaluation continued undermining the validity of their results and conclusions.

Therefore, a more comprehensive evaluation was demanded and current meta-analysis was performed to systematically evaluate the clinical–pathological features and long-term prognosis between this rare entity and the conventional HCC.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Current study was conducted following The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration (Liberati et al. 2009). A comprehensive literature researching was performed in PubMed, Cochrane Library and EMBASE till 1st May, 2021. Eligible studies were restricted to comparative studies between SHCC and HCC. The following combinations of terms were used: (Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma) OR (Sarcomatoid HCC). Any relevant studies in the reference list were also screened to broaden our research.

Inclusion criteria

Published or unpublished English studies;

Comparative studies between SHCC and HCC;

Studies reported clinical-pathological outcomes or provided survival information.

Exclusion criteria

Abstracts, letters, meetings, case reports or reviews;

Irrelevant studies or relevant studies but required information was not available;

Non-comparative studies;

Studies shared a same patient source.

Study selection and data extraction

According to the selection criteria, two reviewers (author 1 and author 2) independently browsed all titles and abstracts. All relevant articles presented in the reference list were manually reviewed to find potentially eligible papers. Besides, studies identified in previous reviews were also screened. They also independently assessed all studies included. Any puzzle or divergence between the reviewers was resolved by discussion or by consulting the corresponding author. Extracted data were roughly classified as follows:

Long-term survival between SHCC and HCC: overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) (primary endpoints)

Tumor-related clinical-pathological features of SHCC and HCC: the number of patients with preoperative HBV infection, HCV infection, liver cirrhosis, Child A/B liver function, serum total bilirubin (TB) level, serum, preoperative AFP level, tumor size, tumor number, tumor differentiation status, node metastasis, vascular invasion (secondary endpoints)

Quality assessment

The quality of all identified studies was evaluated by two reviewers (author 1 and author 2) according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) score (Stang and Stang 2010). The quality scores > 6 indicated that the quality of the cohort was relatively high. The results were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all studies included

| Author | Year | Study period | Population source | No. patients with HCC lesions | Follow up | Quality score (NOS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcomatoid | Nonsarcomatoid | ||||||

| Liao et al. | 2019 | 1996–2016 | Database of National Taiwan University Hospital | 40 | 160 |

Sarcomatoid: 8.8 (0.7–104.6) Nonsarcomatoid: 34.2 (0.6–110.7) |

8 |

| Wang et al. | 2020 | 2007–2017 | Database of Shandong Provincial Hospital | 41 | 155 |

Sarcomatoid: 10.5 (1.7–81.7) Nonsarcomatoid: 27.7 (2.1–138.5) |

8 |

| Wu et al. | 2019 | 2004–2015 | NCDB database | 104 | 312 | NA | 7 |

| Lu et al. | 2015 | 1994–2012 | Database of West china hospital | 52 | 214 | Every2–3 months the first year, then 3–6 months annually thereafter | 9 |

No. the number of, NA not available, NOS Newcastle Ottawa Scale, NCDB National Cancer Database

Statistical analysis

RevMan5.3 software and Stata 13.0 software were used for statistical analyses. Odds ratio (OR) was applied in the analyses of dichotomous variables. A pooled OR with a 95% confidence interval (CI) did not overlap with 1 indicated the existence of statistical difference. Weighted mean difference (WMD) was applied in the analyses of continuous variables. A WMD with its 95% CI did not overlap with 0 suggested a statistical difference. A hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% CI did not overlap with 1 indicated the existence of statistical significance and was applied in the survival analyses. If the HR was not directly provided, a rough estimate was performed using Tierney’s method from Kaplan–Meier curves by the Engauge Digitizer V4.1 (Markmitch, Goteborg, Sweden) (Tierney et al. 2007).

Heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and the Higgins I2 statistic. A P value lower than 0.1 and an I2 value greater than 50% indicated the existence of significant heterogeneity (Higgins and Thompson 2002). The random-effects model was applied when the value of I2 was greater than 50% otherwise the fixed-effect model would be used.

For the potential publication bias, Begg’s test and Egger’s test were used for evaluation. A P value or corrected P value lower than 0.05 indicated the existence of significant publication bias (Egger et al. 1997). Sensitivity analysis was performed via removing every single study to re-evaluate the stability of the synthetic results.

Results

Study identification and selection

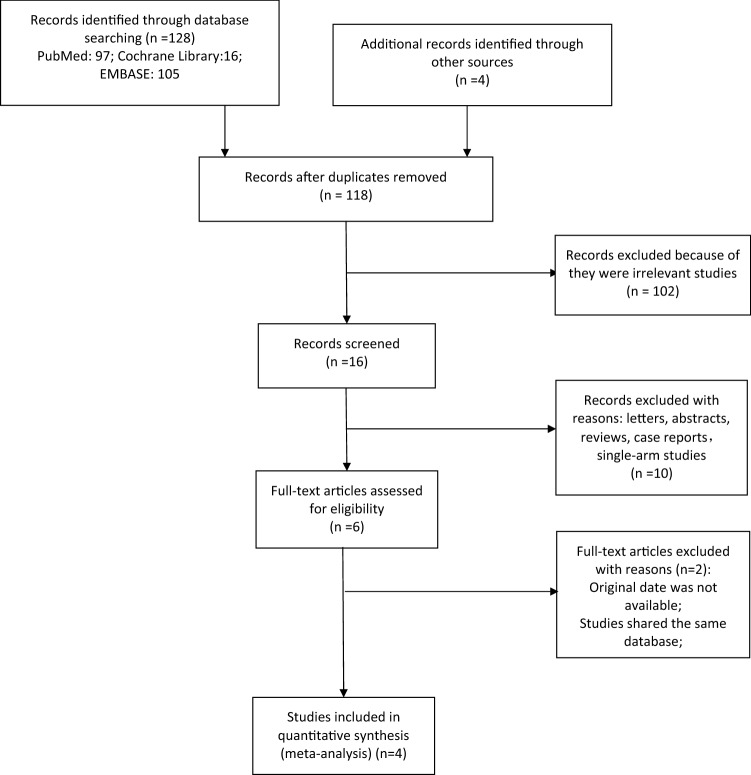

Based on our search strategy, a total of 128 studies were retrieved. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, four studies were finally identified. The specific process of literature searching and selection is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The specific process of literature searching and selection

Study characteristics

All these four studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2019) were retrospective cohort studies between patients with SHCC and conventional HCC. There are about 185 patients with SHCC disease and 627 patients with HCC. All studies included compared the long-term survival between SHCC and HCC, which were presented in the corresponding Kaplan–Meier curves. Besides, studies by Liao et al. (2019), Wang et al. (2020) and Lu et al. (2015) comparatively analyzed the clinical and pathological features of SHCC and HCC. The baseline characteristics of all studies included are summarized in Table 1. Totally, there were 15 measured outcomes identified, including two primary measured outcomes: overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) and thirteen secondary measured outcomes: the number of patients with preoperatively-defined HBV infection, HCV infection, liver cirrhosis, Child A/B class, serum total bilirubin level and serum albumin level, serum ALT level and the number of patients with preoperative AFP level > 20 ng/ml; intraoperatively-evaluated tumor size, the number of patients with intraoperatively-evaluated multifocal tumors, III/IV differentiation status, node metastasis, vascular invasion. The pooled results of all available studies in measured outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pooled results of all available studies in measured outcomes

| Measured outcomes | No. of studies | No. of patients | Model (fixed/random) | OR/WMD, HR | 95% CI | P (overall test) | Heterogeneity | Begg’s test | Egger test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | NS | I2 (%) | P | Pr >|z|* | Pr >|z|** | P >|t|* | ||||||

| Primary measured outcomes (long-term survival) | ||||||||||||

| OS | 4 | 186 | 674 | Random | 2.43 | 2.06 to 2.87 | < 0.00001 | 36 | 0.20 | 0.174 | 0.308 | 0.052 |

| DFS | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 3.12 | 1.80 to 5.39 | < 0.0001 | 79 | 0.008 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.470 |

| Secondary measured outcomes (clinical-pathological features) | ||||||||||||

| HBV infection | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 0.65 | 0.42 to 0.99 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.90 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.938 |

| HCV infection | 2 | 81 | 315 | Fixed | 1.39 | 0.66 to 2.94 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.42 | – | – | – |

| Liver cirrhosis | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 1.00 | 0.63 to 1.57 | 0.98 | 49 | 0.14 | 0.117 | 0.296 | 0.040 |

| Child–Pugh A/B | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 0.62 | 0.36 to 1.30 | 0.24 | 0 | 0.97 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.995 |

| TB | 2 | 81 | 315 | Fixed | − 0.41 | − 0.70 to − 0.12 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.51 | – | – | – |

| ALT | 2 | 81 | 315 | Fixed | − 10.14 | − 18.93 to − 1.35 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.39 | – | – | – |

| ALB | 2 | 81 | 315 | Fixed | − 0.15 | − 0.27 to − 0.02 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.43 | – | – | – |

| AFP > 20 ng/ml | 2 | 93 | 369 | Random | 0.34 | 0.08 to 1.56 | 0.17 | 90 | 0.002 | – | – | – |

| Tumor size | 3 | 133 | 529 | Random | 1.61 | − 0.47 to 3.69 | 0.13 | 88 | 0.003 | 0.117 | 0.296 | 0.180 |

| Tumor number (multiple) | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 1.16 | 0.77 to 1.74 | 0.49 | 0 | 0.71 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.774 |

| Differentiation status (III/IV) | 4 | 186 | 674 | Random | 1.16 | 0.90 to 1.48 | 0.25 | 85 | 0.0002 | 0.497 | 0.734 | 0.092 |

| Node metastasis | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 6.43 | 3.35 to 12.31 | 0.0001 | 0 | 0.47 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.368 |

| Vascular invasion | 3 | 133 | 529 | Fixed | 0.84 | 0.53 to 1.34 | 0.46 | 0 | 0.93 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.766 |

No. of the number of, OR odds ratio, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, – not applicable, S sarcomatoid, NS nonsarcomatoid, TB total bilirubin, ALT alanine transaminase, ALB albumin, * P value, ** P value (continuity corrected), OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, AFP alpha fetoprotein

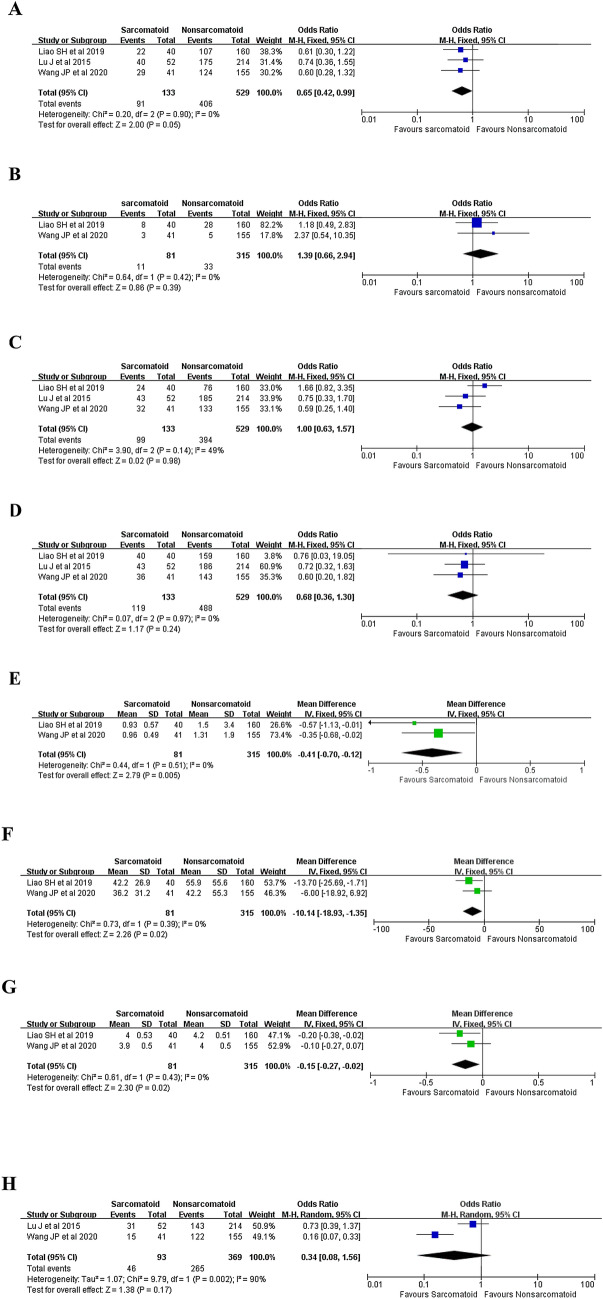

HBV infection

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with preoperatively-defined HBV infection and the result revealed no significant difference between patients with SHCC and patients with HCC (68.4 versus 76.0%, OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.42–0.99; P = 0.05) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots presenting the clinical features between patients with SHCC and patients with pure HCC. A Concurrent HBV infection, B concurrent HCV infection, C concurrent liver cirrhosis, D preoperative liver function (Child A/B); E total serum bilirubin level; F alanine transaminase, G albumin, H the number of patients with preoperative AFP level > 20 ng/ml

HCV infection

Two studies (Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with preoperatively-defined HCV infection and the result revealed no significant difference between two groups (13.6 versus 10.5%, OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.66–2.94; P = 0.39) (Fig. 2B).

Liver cirrhosis

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with preoperatively-defined liver cirrhosis and the result revealed no significant difference between two groups (74.4 versus 74.5%, OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.63–1.57; P = 0.98) (Fig. 2C).

Child–Pugh class, A/B

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with preoperatively-defined liver function (Child A/B) and the result revealed no significant difference between two groups (89.5 versus 92.2%, OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.36–1.30; P = 0.24) (Fig. 2D).

Serum TB

Two studies (Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the preoperatively-evaluated serum TB level of two groups and the result revealed that patients with HCC shared a significantly higher serum TB level (WMD = − 0.41; 95% CI − 0.70 to − 0.12; P = 0.005) (Fig. 2E).

Serum ALT

Two studies (Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the preoperatively-evaluated serum ALT level of two groups and the result revealed that patients with HCC shared a significantly higher serum ALT level (WMD = − 10.14; 95% CI − 18.93 to − 1.35; P = 0.02) (Fig. 2F).

Serum ALB

Two studies (Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the preoperatively-evaluated serum ALB level of two groups and the result revealed that patients with HCC shared a significantly higher serum ALB level (WMD = − 0.15; 95% CI − 0.27 to − 0.02; P = 0.02) (Fig. 2G).

Preoperative AFP level > 20 ng/ml

Two studies (Lu et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with preoperative AFP level > 20 ng/ml. Pooled result reveled that patients with HCC shared a higher incidence with an elevated preoperative AFP level (49.5 versus 71.8%, OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.08–1.56; P = 0.17) (Fig. 2H). However, the result failed to reach a statistical difference (P = 0.17).

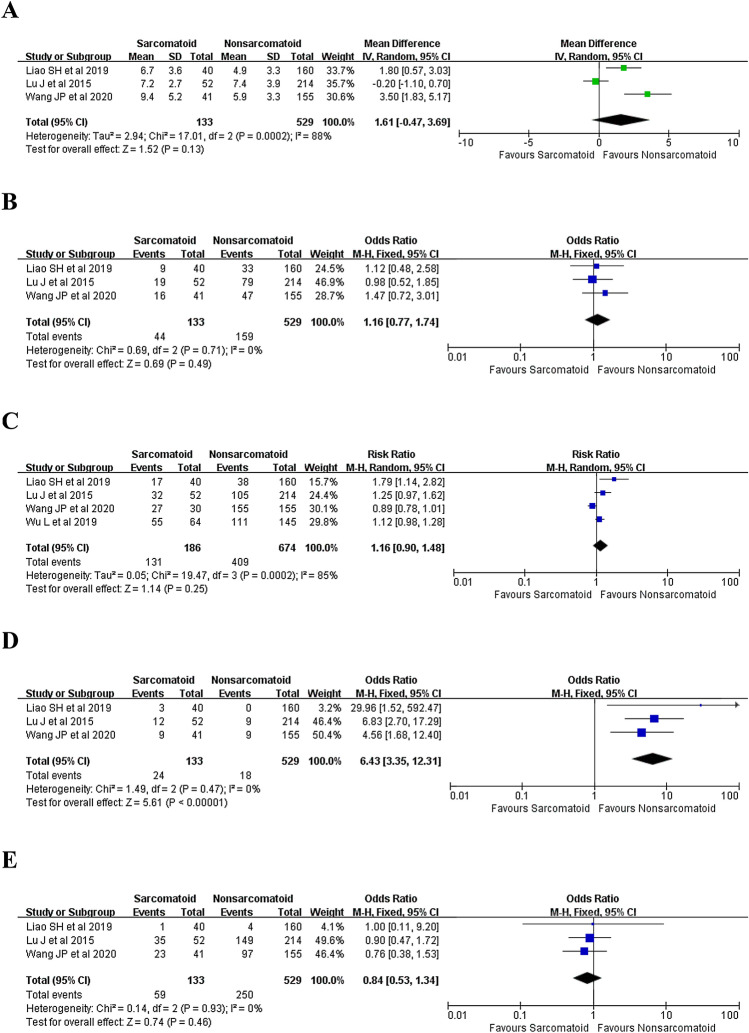

Tumor size

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the intraoperatively evaluated tumor size and the result revealed that SHCC shared a significantly larger tumor size than HCC (WMD = 1.61; 95% CI − 0.47 to 3.69; P = 0.13) (Fig. 3A). However, after excluding the study by Lu et al. (2015), a significant difference was detected (WMD = 2.55; 95% CI 0.90–4.21; P = 0.003).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots presenting the tumor pathological features between patients with SHCC and HCC. A Tumor size, B tumor number (multiple), C tumor differentiation status (poorly or undifferentiated), D node metastasis, E vascular invasion

Multifocal tumors

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with multifocal tumors of two groups and the result revealed no significant difference between two groups (33.1 versus 30.1%, OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.77–1.74; P = 0.49) (Fig. 3B).

III/IV differentiation grades

Four studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2019) reported the number of patients with poorly (III) or undifferentiated (IV) lesions of two groups and the result revealed no significant difference between two groups (70.4 versus 60.7%, OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.90–1.48; P = 0.25) (Fig. 3C). However, after excluding the study by Wang et al. (2020), the subsequent pooled result revealed that patients with SHCC shared a relatively higher incidence of III/IV disease (66.7% versus 58.9%, OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.01–1.59; P = 0.04).

Node metastasis

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with node metastasis of both groups and the result revealed that node metastasis was more frequently detected in patients with SHCC (18.0 versus 3.4%, OR 6.43, 95% CI 3.35–12.31; P < 0.00001) (Fig. 3D).

Vascular invasion

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) reported the number of patients with vascular invasion of both groups and the result revealed no significant difference between two groups (44.4 versus 47.3%, OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.53–1.34; P = 0.46) (Fig. 3E).

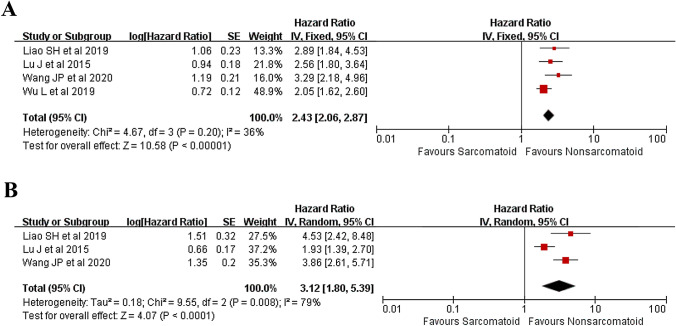

OS

Four studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2019) were incorporated in the analysis of OS and the result revealed that patients with SHCC shared a significantly worse OS than patients with pure HCC (HR 2.43, 95% CI 2.06–2.87, P < 0.00001) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots presenting the long-term survival between patients with SHCC and HCC. A OS, B DFS

DFS

Three studies (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020) were incorporated into the analysis of DFS and the result revealed that patients with SHCC shared a significantly worse DFS than patients with pure HCC (HR 3.12, 95% CI 1.80–5.39, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4B).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Begg’s test and Egger’s test were applied in the evaluation of publication bias within each applicable comparison. The results were robust. Sensitivity analyses were accomplished via removing every single study to evaluate the stability of the synthetic results. Only the study by Wang et al. (2020) had a great impact on the comparison of III/IV differentiation grades and the study by Lu et al. (2015) had a great impact on the pooled result within the comparison of tumor size.

Discussion

Sarcomatoid carcinoma is a relatively infrequent malignancy differing from conventional adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. The sarcomatoid component of this rare entity comprises of spindle-shaped cells, a small subset of cells within the tumor exhibit oval and elongated nuclei, accompanied by conspicuous nucleoli as well as spindle-shaped eosinophilic cytoplasm with increased mitotic activity (Giunchi et al. 2013). Various terminologies have been introduced to describe sarcomatoid carcinoma, such as spindle cell carcinoma, pleomorphic carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma and carcinosarcoma. As its name implies, sarcomatoid carcinoma consists of spindle cells with the remaining cells developing epithelial differentiation, such as CK, while no mesenchymal transition-related markers are detected (Lee 2014). The most frequently detected locations of sarcomatoid carcinoma were in lungs, followed by urinary system, breast and digestive system (Chin and Kim 2014; Lao et al. 2007). Only a few studies with a limited number of patients have reported its primary location within the liver and most of them are case reports (Maeda et al. 1996; Yang et al. 2020; Chin and Kim 2014; Lao et al. 2007; Li et al. 2018; Murata et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2014). Little has been known about SHCC and our meta-analysis was performed in such a condition to evaluate its tumor biological features and long-term survival versus conventional HCC. Our major findings are as follows:

SHCC shares a significantly worse OS (P < 0.00001) and DFS (P < 0.0001) versus pure HCC.

SHCC exhibits more aggressively versus pure HCC that a larger tumor size, a higher incidence of node metastasis and a higher proportion of advanced lesions are more frequently detected in patients with SHCC (P < 0.05)

Higher levels of preoperatively examined serum ALT and TB are detected in patients with HCC rather than SHCC, while serum ALB level is relatively higher in patients with SHCC.

Etiology

The etiology of SHCC has not been elucidated. The most common recognized theory is the conversion theory, which suggests that the sarcomatous elements derive from the carcinoma tissue during its evolution (Maeda et al. 1996; Shin et al. 1981; McCluggage 2002; Lester et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2019). For example, numerous studies have indicated that epithelial-mesenchymal transition accounted for the sarcomatous change (Kim et al. 2015; Sung et al. 2013; Yen et al. 2017). However, other potential mechanisms were also reported but have not been explored and validated. Some authors accounted it for the necrosis and degeneration after repeated nonsurgical modalities (Kojiro et al. 1989), such as trans arterial chemoembolization, radio ablation or ethanol injection, while others reported the opposite observations that patients without receiving nonsurgical anticancer therapies may also develop SHCC (Yokomizo et al. 2007). Others also argued that viral hepatitis, especially hepatitis B or C infection, were closely-associated with the proliferation process of sarcomatous cells (Yu et al. 2017). Comparable frequencies of HBV and HCV infection are acquired in our manuscript, suggesting the unfeasibility of the theory of hepatitis viral-originated carcinogenesis. However, the limited number of patients greatly undermined the validity of our results. Perhaps, various undiscovered molecules adjusting tumor proliferation and differentiation or cells immune micro-environment may promote sarcomatous change. Future well-designed basic experiments are required for further exploration.

Diagnosis

To our knowledge, except for post-surgical pathological examination, there are no effective methods assisting clinicians in its accurate preoperative diagnosis. Some patients were reported to have higher incidences of developing unrepresentative symptoms, including abdominal discomfort, weight loss and fever (Wang et al. 2020). Interestingly, a ten times higher incidence of fever was observed in patients SHCC versus those with pure HCC, partially due to the more frequently-occurred tumor necrosis owing to the larger tumor size and the faster growth of the sarcomatoid tumor (Wang et al. 2020). The observations above were only reported in a few cases and were not that powerful to draw a conclusion. Undeniably, the accurate preoperative diagnosis of SHCC relies on a combination of multiple modalities, especially radiological examinations. The CT findings of SHCC often manifests irregular heterogeneous masses with delayed and prolonged peripheral enhancement, along with central necrosis and hemorrhage (Yoshida et al. 2013). Approximately more than half of patients with SHCC in the study by Liao et al. presented like this (Liao et al. 2019). However, in terms of MRI examination, over 60% patients with SHCC showed similar imaging features as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHCC) or liver abscess (Wang et al. 2020; Seo et al. 2019). Clinically, fever, rigor, nausea, and weight loss as well as many other nonspecific symptoms suggestive of liver abscess were also frequently-detected in patients with SHCC, which may delay the timely diagnosis of this malignancy and the following treatment (Wang et al. 2012). Moreover, the secondary formation of liver abscess due to the central necrosis and infection within the tumor might also make the accurate diagnosis of SHCC more confusing. However, as reported by Yang et al., SHCC can be differed from liver abscess that a relatively thicker wall was more frequently detected in patients with liver abscess while portal vein or hepatic vein thrombosis was rarely detected (Yang et al. 2020). Additionally, numerous studies have reported that patients with SHCC shared a similar history of concurrent viral hepatitis and liver cirrhosis as patients with HCC did, suggesting that patients with the concurrent disease above may be in high risk of developing SHCC (Lu et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020). Conventional ultrasound screening in these patients may contribute to early detection and achieving a better survival but lacks specific sensitivity for SHCC (Heimbach et al. 2018; Choi et al. 2019). Conventional laboratory tests also showed the absence of sensitivity in the diagnosis of SHCC. An inflammatory response with nonspecifically elevated WBC and increased C-proteins can be observed in patients with liver abscess or malignant disease with necrosis and infection. Regarding tumor biomarkers, an elevated preoperative AFP level seemed to be more frequently detected in patients with HCC. Only the study by Lu et al. (2015) and the study by Wang et al. (2020) reported the preoperative AFP level and our pooled results revealed that patients with HCC had a higher tendency with preoperative AFP level > 20 ng/ml (49.5 vs 71.8%). Many other invasive diagnostic modalities, such as fine needle aspiration and biopsy, could provide the accurate pathological diagnosis. However, the risk of hemorrhage, bile leakage, and tumor spreading have limited their conventional application (Midia et al. 2019). Therefore, the accurate preoperative diagnosis of SHCC remains confusing and challenging.

Management

Currently, there are no established guidelines regarding the optimal treatment modalities for SHCC. Curative surgery provides the only chance of curing this malignant disease and remains the most effective therapeutic option for SHCC, especially for those with AJCC stage I and II disease. For patients with SHCC with AJCC stage III and IV disease, the majority of them only received palliative treatment. The results in the study by Wu et al. (2019) suggested the survival benefit brought by curative therapy differed much between patients with SHCC and HCC. A significantly worse prognosis after curative therapy was achieved in patients with SHCC compared with patients with pure HCC (Wu et al. 2019). Moreover, in the study by Wu et al., although curative surgery was performed equally in SHCC patients with AJCC stage I and II disease, survival benefit was only observed in those with AJCC I disease while the long-term survival was comparable among AJCC II, III and IV disease. Totally, all patients with II, III and IV disease failed to survive more than 2 years (Wu et al. 2019). Hence, curative-intent surgery in patients with SHCC seems to be only applicable in patients with AJCC I lesions while for those with more advanced disease, a combination of multiple therapeutic modalities, such as liver resection, liver transplantation and ablation, are required. Undoubtedly, upcoming well-designed studies are required for further validation.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with SHCC is generally considered poorer than conventional pure HCC, which has been validated in many previously-published studies (Maeda et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2015; Hwang et al. 2008; Liao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2019). Similarly, our results, with the largest number of patients included, acquired the same observation that patients with SHCC have a significantly worse OS and DFS than those with HCC (P < 0.00001). The first relative large study with 52 SHCC patients included by Lu et al. (2015) revealed a significantly worse survival in patients with SHCC compared with patients with pure HCC (P < 0.05). Four years later, similar observations were also detected in the studies by Wu et al. (2019) and Liao et al. (2019). However, the three studies introduced above have an inescapable defect, that is, the inconsistency of the surgical indication between two groups. Many uncontrolled factors, including fibrosis score, tumor size, the extent of resection and the tumor differentiation status, continued undermining the validity of their conclusions. Fortunately, a comparative study by Wang et al. (2020) controlled the potential confounding factors and also acquired a significantly worse prognosis in patients with SHCC. Moreover, our study has revealed that a relatively larger tumor size and a higher incidence of node metastasis are more frequently detected in patients with SHCC (P < 0.05), suggesting that SHCC exhibits more aggressively than HCC, which further explains the survival difference between two types of lesions. In line with our findings, many studies have also demonstrated that lymph node metastasis and vascular invasion were more frequently detected in patients with SHCC (Maeda et al. 1996; Watanabe et al. 1994; Eriguchi et al. 2001; Honda et al. 1996), which greatly validated the fact that SHCC is more aggressive and has a worse prognosis than pure HCC.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. Firstly, owing to the rarity of the disease, the number of available studies is limited and our conclusion is less statistically powerful. Secondly, the retrospective nature of the studies included would introduce bias, especially the selection bias due to many uncontrolled factors. Thirdly, a rough estimate via Tierney’s method may introduce moderate bias. Fourth, the inadequate original date, such as the preoperative AFP level and the specific locations of recurrence, hindered a more comprehensive evaluation.

Conclusion

Current systematic review and meta-analysis provides an in-depth analysis on the consistencies and inconsistencies of SHCC versus conventional HCC. Our results reveals that SHCC shares a significantly worse prognosis and has exhibited more aggressively than pure HCC. Considering the small sample size as well as many uncontrolled factors, more powerful well-designed studies are warranted for further validation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC21046); 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence-Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2021HXFH001); Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2021YJ0132, 2021YFS0100); The fellowship of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M692277); Sichuan University-Zigong School-local Cooperation project (2021CDZG-23); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019SCUH0021), and Post-Doctor Research Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2021HXBH127).

Author contributions

T-RL and H-JH contributed equally to the study. T-RL contributed to data acquisition and drafted the manuscript. H-JH contributed to the literature review, manuscript editing and subsequent minor revision. PR, FL were involved editing the manuscript. F-YL contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was Supported by 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC21046); 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence-Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2021HXFH001); Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2021YJ0132, 2021YFS0100); The fellowship of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M692277); Sichuan University-Zigong School-local Cooperation project (2021CDZG-23); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019SCUH0021), and Post-Doctor Research Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2021HXBH127).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study is included in the published article.

Declarations

Role of the funding source

Funding Source has no role in design and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tian-Run Lv and Hai-Jie Hu contributed equally to the study and were the co-first authors.

References

- Chin S, Kim Z (2014) Sarcomatoid combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7:8290–8294 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D, Kum H, Park S et al (2019) Hepatocellular carcinoma screening is associated with increased survival of patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 17:976-987.e974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (clin Res Ed.) 315:629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Okuda K et al (2001) Unusual liver carcinomas with sarcomatous features: analysis of four cases. Surg Today 31:530–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunchi F, Vasuri F, Baldin P, Rosini F, Corti B, D’Errico-Grigioni A (2013) Primary liver sarcomatous carcinoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract 209:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimbach J, Kulik L, Finn R et al (2018) AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 67:358–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21:1539–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda H, Hayashi T, Yoshida K et al (1996) Hepatocellular carcinoma with sarcomatous change: characteristic findings of two-phased incremental CT. Abdom Imaging 21:37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S, Lee S, Lee Y et al (2008) Prognostic impact of sarcomatous change of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients undergoing liver resection and liver transplantation. J Gastrointest Surg off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract 12:718–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizoe S, Kojiro M, Nakashima T (1987) Hepatocellular carcinoma with sarcomatous change. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies of 14 autopsy cases. Cancer 59:310–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Kim H, Park Y (2015) Sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells associated with hepatolithiasis: a case report. Clin Mol Hepatol 21:309–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim B, Jeong J, Baek Y (2019) Analysis of intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma: experience from 11 cases within 17 years. World J Gastroenterol 25:608–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojiro M, Sugihara S, Kakizoe S, Nakashima O, Kiyomatsu K (1989) Hepatocellular carcinoma with sarcomatous change: a special reference to the relationship with anticancer therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 23:S4-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao X, Chen D, Zhang Y et al (2007) Primary carcinosarcoma of the liver: clinicopathologic features of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 31:817–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K (2014) Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma with mixed osteoclast-like giant cells and chondroid differentiation. Clin Mol Hepatol 20:313–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Kim MW, Choi NK, Cho IJ, Hong R (2014) Double primary hepatic cancer (sarcomatoid carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma): a case report. Mol Clin Oncol 2:949–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester T, Hunt K, Nayeemuddin K et al (2012) Metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the breast appears more aggressive than other triple receptor-negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131:41–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wu X, Bi X et al (2018) Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of four rare subtypes of primary liver carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res Chung-Kuo Yen Cheng Yen Chiu 30:364–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Su T, Jeng Y et al (2019) Clinical Manifestations and outcomes of patients with sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 69:209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6:e1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Xiong X, Li F et al (2015) Prognostic significance of sarcomatous change in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol 22:S1048-1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Adachi E, Kajiyama K, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K, Tsuneyoshi M (1996) Spindle cell hepatocellular carcinoma. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 15 cases. Cancer 77:51–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluggage W (2002) Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol 55:321–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midia M, Odedra D, Shuster A, Midia R, Muir J (2019) Predictors of bleeding complications following percutaneous image-guided liver biopsy: a scoping review. Diagn Interv Radiol (Ankara, Turkey) 25:71–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata M, Miyoshi Y, Iwao K et al (2001) Combined hepatocellular/cholangiocellular carcinoma with sarcomatoid features: genetic analysis for histogenesis. Hepatol Res off J Jpn Soc Hepatol 21:220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numbere N, Zhang D, Agostini-Vulaj D (2020) A rare histologic subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma, sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Hepat Oncol 8:HEP33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo N, Kim M, Rhee H (2019) Hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma: magnetic resonance imaging evaluation by using the liver imaging reporting and data system. Eur Radiol 29:3761–3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin P, Ohmi S, Sakurai M (1981) Hepatocellular carcinoma combined with hepatic sarcoma. Acta Pathol Jpn 31:815–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang A, Stang A (2010) (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 259:603–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung C, Choi H, Lee K, Kim S (2013) Sarcomatoid carcinoma represents a complete phenotype with various pathways of epithelial mesenchymal transition. J Clin Pathol 66:601–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR (2007) Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 8:16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Cui B, Weng J, Wu Q, Qiu J, Lin X (2012) Clinicopathological characteristics and outcome of primary sarcomatoid carcinoma and carcinosarcoma of the liver. J Gastrointest Surg off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract 16:1715–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yao Z, Sun Y et al (2020) Clinicopathological characteristics and surgical outcomes of sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 26:4327–4342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe J, Nakashima O, Kojiro M (1994) Clinicopathologic study on lymph node metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 660 consecutive autopsy cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol 24:37–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Tsilimigras D, Farooq A et al (2019) Management and outcomes among patients with sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Cancer 125:3767–3775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D, Zuo K, Li X et al (2013) Concomitant early gallbladder carcinoma with primary sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Oncol Lett 5:1965–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi R, Nakashima O, Yano H, Kutami R, Kusaba A, Kojiro M (1997) Hepatocellular carcinoma with sarcomatous change. Oncol Rep 4:525–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Lv K, Zhao Y, Pan M, Zhang C, Wei S (2020) Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma mimicking hepatic abscess: a case report. Medicine 99:e22489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen C, Lai C, Liao C et al (2017) Characterization of a new murine cell line of sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma and its application for biomarker/therapy development. Sci Rep 7:3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomizo J, Cho A, Yamamoto H et al (2007) Sarcomatous hepatocellular carcinoma without previous anticancer therapy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14:324–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida N, Midorikawa Y, Kajiwara T et al (2013) Hepatocellular carcinoma with sarcomatoid change without anticancer therapies. Case Rep Gastroenterol 7:169–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zhong Y, Wang J, Wu D (2017) Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma (SHC): a case report. World J Surg Oncol 15:219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Li H, Yuan Z et al (2020) Achievement of complete response to nivolumab in a patient with advanced sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 12:1209–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study is included in the published article.