Abstract

Objective:

Developmental disruption contributes to poor psychosocial outcomes among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer, though indicators of AYAs’ developmental status are not well understood. In this study, we describe perceived adult status as a novel developmental indicator and examine its associations with social milestones achievements and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Methods:

For this secondary analysis, AYAs with cancer were recruited using a 2 (on/off treatment) × 2 [emerging adults (EAs) 18–25 years-old, young adults (YAs) 26–39 years-old] stratified sampling design through an online research panel. Surveys assessed perceived adult status (i.e., self-perception of the extent to which one has reached adulthood), social milestones (marital, child-rearing, employment, educational status), demographic and treatment characteristics, and HRQoL. Generalized linear models tested associations between perceived adult status, social milestones, and HRQoL.

Results:

AYAs (N = 383; Mage = 27.2, SD = 6.0) were majority male (56%) and treated with radiation without chemotherapy (37%). Most EAs (60%) perceived they had reached adulthood in some ways; most YAs (65%) perceived they had reached adulthood. EAs who perceived they had reached adulthood were more likely to be married, raising a child, and working than EAs who did not perceive they had reached adulthood. Among EAs, lower perceived adult status was associated with lower HRQoL when accounting for social milestones. Among YAs, perceived adult status was not associated with social milestones and neither perceived adult status nor social milestones were associated with HRQoL.

Conclusions:

Perceived adult status may be a useful developmental indicator for EAs with cancer. Findings highlight unique developmental needs of EAs and utility of patient perspectives for understanding developmental outcomes.

Keywords: adolescent and young adult, cancer, development, health-related quality of life, oncology, social outcomes

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer are at high risk for poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL).1 Compared to healthy populations, AYAs with cancer experience HRQoL deficits in physical and mental health2 and for many, these persist into post-treatment survivorship.3,4 Disruptions in key developmental processes and goals are widely considered a driver of poor outcomes for AYAs and are believed to contribute to HRQoL deficits.5–7 However, indicators of AYAs’ developmental status are not well understood. Developmental status broadly refers to the extent to which one has achieved the relevant developmental goals based on life stage, and thus may be indicated by a range of factors depending on one’s age and the developmental domain of interest (e.g., socioemotional). For AYAs with cancer, identifying indicators of developmental status that are relevant for HRQoL may help us better understand how and when developmental disruptions occur, identify at-risk individuals, and inform developmentally tailored care.

To examine developmental status among AYAs with cancer, it is critical to differentiate the unique developmental periods within the National Cancer Institute (NCI) defined AYA age range. These include adolescence (15–17 years-old), emerging adulthood (18–25 years-old), and young adulthood (26–39 years-old), each of which is associated with unique developmental processes and goals. Though AYA studies typically differentiate adolescents with cancer from older AYAs, few consider emerging adults and young adults with cancer as unique groups. Emerging adults are tasked with exploring independent roles via education, career, and romantic relationships, though most are not fully independent from parents.8–10 Indeed, establishing financial self-sufficiency and an equal relationship with parents are considered key markers of the transition from emerging adulthood to young adulthood.11–13 During young adulthood, identity stabilizes and goals evolve to establishing long-term social roles through career, marriage, and/or parenthood.10 Given that each developmental period is associated with different developmental goals, indicators of AYAs’ developmental status and their relevance for HRQoL may also differ between EAs and YAs with cancer.

One approach to understanding AYAs’ developmental status has been via achievement of social milestones including employment, education, marriage, and parenthood. During emerging and young adulthood, these social milestones may indicate developmental status by serving as proxies for developmental goals or representing the accomplishment of developmentally expected social roles. A growing body of evidence has suggested that AYAs with cancer experience deficits or delays in some social milestones such as marriage, having children, and full-time employment.14,15 However, characterizing AYAs’ developmental status based on social milestones alone is limited. First, social milestones are often imperfect proxies for developmental goals; thus, delays in their achievement may or may not indicate developmental disruption. Second, using social milestones to signify developmental outcomes assumes a traditional view of the life course that does not account for shifting cultural expectations or individual differences in values (e.g., choosing not to have children). Indeed, most young people do not consider social milestones of marriage, having a child, or being settled in a career as important markers of adulthood11–13 and, among non-ill AYAs, attaining these milestones is not associated with better wellbeing.13 Among AYAs with cancer, evidence for associations between social milestones and HRQoL has also been mixed.16–18 Thus, there is need to explore other developmental indicators that may better capture AYAs’ developmental status and have more relevance for HRQoL.

Perceived adult status, or the extent to which individuals perceive they have reached adulthood,8 may represent a useful developmental indicator for AYAs with cancer. Perceived adult status has not been examined among AYAs with cancer though its significance as a developmental indicator in the general population has been well-described.8,19 Importantly, perceived adult status is believed to capture a unique aspect of developmental status beyond age and developmental period. Though older individuals are more likely to perceive they have reached adulthood, there is substantial variability within each developmental period even when accounting for age.8 Perceived adult status is also believed to be unique from social milestones as young people tend to rate individualistic criteria (e.g., personal responsibility, having an equal relationship with parents) as the most important markers of adulthood and rate social role transitions (e.g., getting married, having a child) among the least.11–13 Thus, by capturing how AYAs with cancer subjectively view their own developmental status, perceived adult status may be an important developmental indicator with relevance for AYAs’ HRQoL outcomes.

In the current study, we first aim to describe perceived adult status among emerging adults (EAs) and young adults (YAs) with cancer by (a) describing the distribution of perceived adult status among EAs and YAs; and (b) examining if perceived adult status varies based on social milestone achievements. Second, we aim to examine if perceived adult status is a unique and useful predictor of HRQoL when accounting for social milestones. Informed by developmental theory,8 we predict that perceived adult status will be associated with HRQoL among both EAs and YAs and will account for unique variance in HRQOL beyond what is accounted for by social milestones.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Data collection and study participants

This secondary analysis includes emerging adults (EAs) and young adults (YAs) with cancer recruited for a larger study through an online research panel, Opinions 4 Good (Op4G). Op4G partners with national health-related non-profits to recruit panel members by contacting donors, volunteers, and the communities they serve. AYAs were recruited for the larger study using a 2 × 3 sampling design (on-treatment vs. off-treatment; adolescents [15–17 years], emerging adults [18–25 years], young adults [26–39 years]). Eligible AYAs were diagnosed with stage 0-IV cancer between the ages of 15–39; currently receiving treatment or <5 years post-treatment; ages 15–39 years-old at time of survey; and able to speak and read English, access the Internet, and provide electronic consent. AYAs were excluded if they had a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. For this secondary analysis, adolescents were excluded as our variables of interest (i.e., perceived adult status, social milestones) were not developmentally relevant for this age group.

Eligible AYAs were identified, approached, and consented by Op4G. Participants were invited to complete an anonymous web-based survey and selected a non-profit organization for a donation. To mitigate data quality concerns, we eliminated surveys missing >10% of items and those that indicated invalid responding (e.g., <1/3 of median survey completion time). Procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (Protocol #: IRB00035377).

2.2 |. Measures

Perceived adult status.

Perceived adult status was assessed using a single item (“Do you think you’ve reached adulthood?”). Respondents answered, ‘Yes,’ ‘No,’ or ‘In some respects yes, and some respects no.’ This global item has been used in previous research with AYA samples in the general population.8,9,19

Social milestones.

(1) Marital status was assessed via a single item (“What is your marital status?”) with responses coded as 0 [single (including single, divorced, separated, or widowed) or 1 [partnered (married or living with partner)]. (2) Child-rearing status was assessed via a single item (“Are you currently raising a child <18 years-old?) with responses coded as 0 (yes) or 1 (no). (3) Education was assessed via a single item (“What is the highest level of education you have completed?”) with responses coded as 0 (≤high school), 1 (some college), or 2 (≥college). (4) Employment status during treatment was determined based on two items assessing school/employment status right before diagnosis and change in school/employment status due to treatment. To create a single variable reflecting employment status during treatment, participants were grouped into 4 mutually exclusive categories: 0 (full- or part-time student), 1 (full- or part-time working), 2 (not in school or working), or 3 (unknown).

Health-related quality of life.

The Late Adolescence and Young Adulthood Survivorship-Related Quality of Life (LAYA-SRQL20) measure was used to assess HRQoL. Thirty items assess satisfaction with ten domains of HRQoL: existential/spirituality, coping, relationship, dependence, vitality, health care, education/career, fertility, intimacy/sexuality, and cognition/memory. For each item, response options range from 1 (completely unsatisfied) to 7 (completely satisfied). Mean scores are calculated for each domain with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction. In this study, all domains demonstrated satisfactory reliability as assessed by Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.82–0.90).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Self-reported sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex (male, female), race, and ethnicity. Self-reported clinical characteristics included treatment status (on or off) and treatment history [history of chemotherapy (yes; no), radiation (yes; no), and surgery (yes; no)]. Treatment history was recoded into a 4-level categorical variable: chemotherapy without radiation (+/− surgery); radiation without chemotherapy (+/− surgery); both chemotherapy and radiation (+/− surgery); and neither chemotherapy nor radiation (i.e., surgery only).

2.3 |. Statistical analyses

Preliminary analyses.

First, we stratified our data by developmental period [EAs = 18–25 years-old, YAs = 26–39 years-old] and described the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of each group. Next, we conducted a factor analysis to determine if it was justifiable to use a mean HRQoL satisfaction score as our outcome of interest (vs. examine each HRQoL domain individually). Specifically, we examined satisfaction scores for each domain across both age groups to determine whether a consistent pattern was observed. Then, we conducted a factor analysis to confirm appropriateness of a single factor structure.

Study aims.

For our first aim, we described perceived adult status by calculating the frequency and percentage of EAs and YAs at each level of perceived adult status. We then used a chi-square test or ANOVA (for categorical or continuous variables, respectively) to identify statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences in perceived adult status based on marital status, child-rearing status, education, employment status, sex, treatment status, treatment history and age.

For our second aim, we used generalized linear models (GLMs) to test if perceived adult status was uniquely associated with HRQoL when accounting for social milestones within each developmental period. This resulted in two GLM models (EAs, YAs); each model included five independent variables (perceived adult status, marital status, child-rearing status, education, employment status) and four covariates (age, gender, treatment status, treatment history) with HRQoL as the outcome of interest.

Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding respondents with a treatment history of surgery only to ensure that our results were not altered by their inclusion. This group is likely to represent individuals with early-stage cancers and/or mild treatment courses who may have experienced less impact on developmental goals and HRQoL relative to those who received chemotherapy and/or radiation.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Preliminary analyses

Our final sample (N = 383, Mage = 27.2, SD = 6.0) included 193 EAs (Mage = 22.2, SD = 2.3), and 190 YAs (Mage = 32.3, SD = 4.0). Across the full sample, participants were 44% female and 56% male; identified their race as Black/African American (n = 32, 8%), Asian (n = 19, 5%), Pacific Islander (n = 2, 1%), Native American (n = 4, 1%), White (n = 296, 77%), other race (n = 6, 2%), mixed-race (n = 23, 6%), or declined to answer (n = 1, 0.3%); and identified their ethnicity as Hispanic (n = 60, 16%) or non-Hispanic (n = 319, 83%). The most commonly reported cancer diagnoses were breast (n = 43, 11%), leukemia (n = 37, 10%), melanoma (n = 37, 10%), lung cancer (n = 33, 9%), brain/CNS tumor (n = 26, 7%), bone tumors/sarcomas (n = 26, 7%) and testicular (n = 25, 7%). Sex, treatment status, and treatment history were similarly distributed across EAs and YAs (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Social milestones, sociodemographic factors, and clinical characteristics of emerging adults by perceived adult status.

| Total N (%) |

Achieved adulthood N (%) |

Achieved adulthood in some respects N (%) |

Not achieved adulthood N (%) |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 0.09 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 22.2 (2.30) | 22.7 (2.06) | 21.9 (2.39) | 22.1 (2.67) | |

| Sex | 0.57 | ||||

| Male | 105 (54.4) | 42 (59.1) | 59 (51.3) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Female | 88 (45.6) | 29 (40.9) | 56 (48.7) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Childrearing status | 0.004 | ||||

| Raising child | 28 (14.5) | 18 (25.4) | 10 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not raising child | 165 (85.5) | 53 (74.7) | 105 (91.3) | 7 (100.0) | |

| Education | 0.08 | ||||

| ≤High school | 89 (46.1) | 31 (43.7) | 52 (45.2) | 6 (85.7) | |

| Some college | 55 (28.5) | 17 (23.9) | 38 (33.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ≥College degree | 49 (25.4) | 23 (32.4) | 25 (21.7) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Employment | 0.0001 | ||||

| Not working or student | 42 (21.8) | 13 (18.3) | 25 (21.7) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Working | 55 (28.5) | 34 (47.9) | 20 (17.4) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Student | 81 (42.0) | 19 (26.8) | 60 (52.2) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Unknown | 15 (7.8) | 5 (7.0) | 10 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.007 | ||||

| Partnered | 31 (16.1) | 19 (26.8) | 12 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Single | 162 (83.9) | 52 (73.2) | 103 (89.6) | 7 (100.0) | |

| Treatment historyb | 0.22 | ||||

| Chemo only | 49 (30.0) | 18 (30.0) | 31 (31.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Radiation only | 71 (42.8) | 20 (33.3) | 46 (46.5) | 5 (71.3) | |

| Chemo and radiation | 23 (13.9) | 12 (20.0) | 10 (10.1) | 1 (14.3) | |

| No chemo or radiation | 23 (13.9) | 10 (16.7) | 12 (12.1) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Treatment status | 0.92 | ||||

| On | 96 (49.7) | 35 (49.3) | 58 (50.4) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Off | 97 (50.3) | 36 (50.7) | 57 (49.6) | 4 (57.1) |

p-value corresponds to chi-square statistic (categorical variables) or F statistic (continuous variables).

Chemo = chemotherapy; all treatment categories are +/− surgery.

TABLE 2.

Social milestones, sociodemographic factors, and clinical characteristics of young adults by perceived adult status.

| Total N (%) |

Achieved adulthood N (%) |

Achieved adulthood in some respects N (%) |

Not achieved adulthood N (%) |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 0.14 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 32.3 (3.99) | 32.7 (4.07) | 31.5 (3.70) | 31.3 (4.59) | |

| Sex | 0.02 | ||||

| Male | 110 (57.9) | 63 (50.8) | 43 (71.7) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Female | 80 (42.1) | 61 (49.2) | 17 (28.3) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Childrearing status | 0.44 | ||||

| Raising child | 71 (37.4) | 45 (36.3) | 25 (41.7) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Not raising child | 119 (62.6) | 79 (63.7) | 35 (58.3) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Education | 0.61 | ||||

| ≤High school | 27 (14.2) | 18 (14.5) | 7 (11.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Some college | 49 (25.8) | 30 (24.2) | 18 (30.0) | 1 (16.7) | |

| ≥College degree | 114 (60.0) | 76 (61.3) | 35 (58.3) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Employment | 0.17 | ||||

| Not working or student | 30 (15.8) | 16 (12.9) | 11 (18.3) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Working | 117 (61.6) | 82 (66.1) | 32 (53.3) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Student | 21 (11.1) | 12 (9.7) | 9 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 22 (11.6) | 14 (11.3) | 8 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.20 | ||||

| Partnered | 87 (45.8) | 55 (44.4) | 32 (53.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Single | 103 (54.2) | 69 (55.7) | 28 (46.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Treatment historyb | 0.08 | ||||

| Chemo only | 44 (26.5) | 34 (32.1) | 9 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Radiation only | 53 (31.9) | 34 (32.1) | 17 (31.5) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Chemo + radiation | 41 (24.7) | 24 (22.6) | 17 (31.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No chemo no radiation | 28 (16.7) | 14 (13.2) | 11 (20.4) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Treatment status | 0.26 | ||||

| On | 97 (51.1) | 61 (49.2) | 31 (51.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Off | 93 (48.9) | 63 (50.8) | 29 (48.3) | 1 (16.7) |

p-value corresponds to chi-square statistic (categorical variables) or F statistic (continuous variables).

Chemo = chemotherapy; all treatment categories are +/− surgery.

For all HRQoL domains, there was a consistent pattern such that satisfaction tended to be lower among EAs than YAs. Factor analytic results showed a strong single factor underlying domain subscores (Appendix A). The single factor accounted for 61% of variance, and the second factor for 10%. Thus, we determined that it was appropriate to proceed with a mean HRQoL satisfaction score as our outcome variable.

3.2 |. Aim 1. Perceived adult status among emerging adults and young adults with cancer

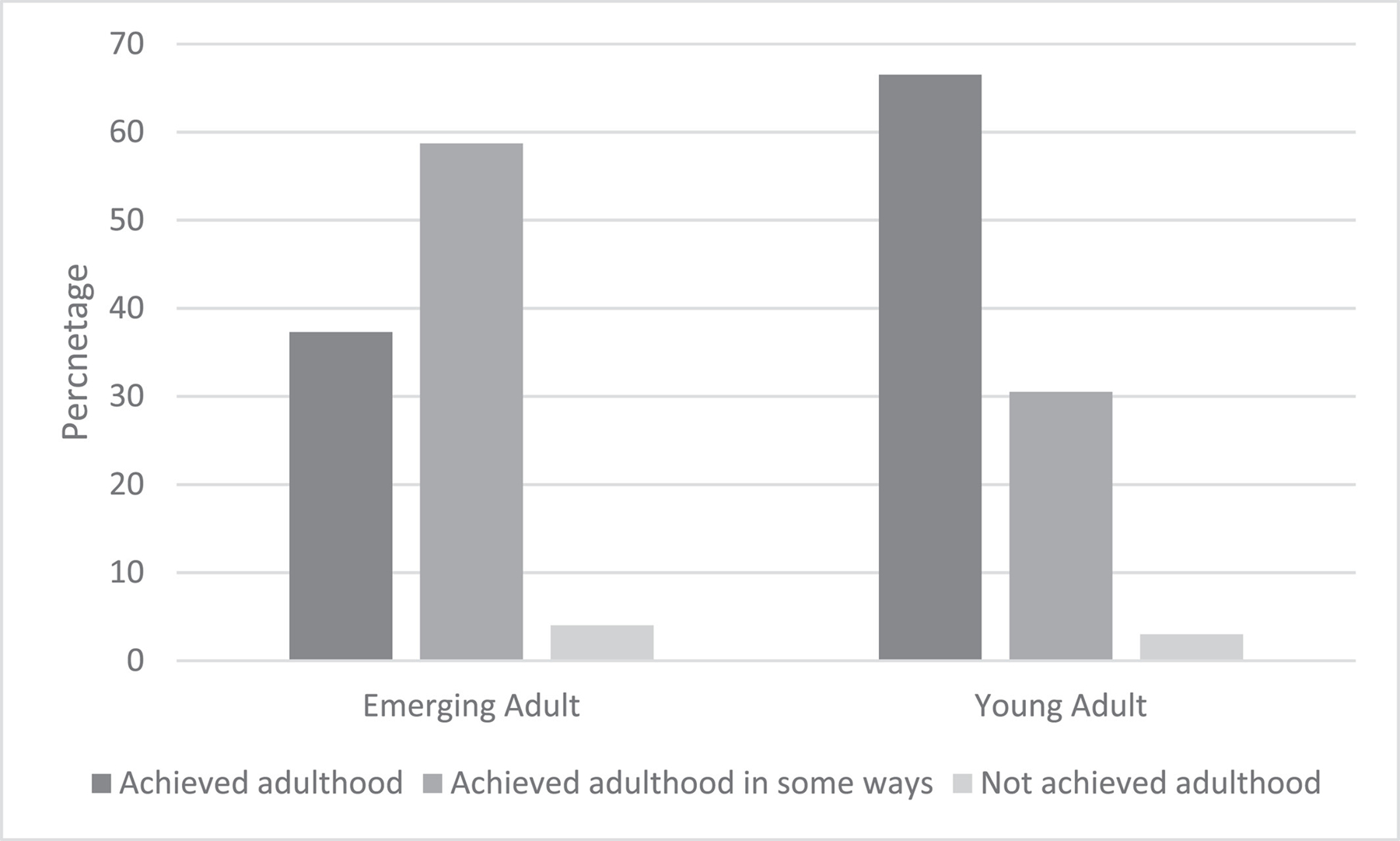

Figure 1 shows the distributions of perceived adult status among EAs and YAs. Among EAs, 60% perceived they had reached adulthood in some respects but not others; 37% perceived they had reached adulthood; and 3% perceived they had not reached adulthood. Among YAs, 65% perceived they had reached adulthood; 32% perceived they had reached adulthood in some respects but not others; and 3% perceived they had not reached adulthood.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of perceived adult status among emerging adults and young adults with cancer.

Among EAs, perceived adult status was associated with childrearing, marital, and employment status (Table 1). A larger proportion of EAs who perceived they had reached adulthood were partnered (27%) compared to EAs who perceived they had reached adulthood in some respects (10% partnered) or not reached adulthood (0% partnered). Similarly, a larger proportion of EAs who perceived they had reached adulthood were raising a child (25%) compared to EAs who perceived they had reached adulthood in some respects (9% raising child) or not reached adulthood (0% raising child). For employment, the largest proportion of EAs who perceived they had reached adulthood were working (48%); the largest proportion who perceived they had reached adulthood in some respects were students (52%); and the largest proportion who perceived they had not reached adulthood were neither working nor students (57%). EAs’ perceived adult status was not associated with sex, educational attainment, treatment status, or treatment history.

Among YAs, perceived adult status was associated with sex such that a larger proportion of YAs who perceived they had reached adulthood were female (49%) compared to YAs who perceived they had reached adulthood in some respects (28% female) or not reached adulthood (33% female; Table 2). YAs’ perceived adult status was not associated with marital, child-rearing, educational, or treatment status, or treatment history.

3.3 |. Aim 2. Associations between perceived adult status and health-related quality of life

Among EAs, perceived adult status was associated with HRQoL satisfaction such that EAs who reported higher perceived adult status had higher satisfaction (b = −0.89, SE = 0.25, p < 0.001; Table 3). No social milestones (child-rearing status, education, employment, marital status) or covariates (age, gender, treatment status, treatment history) were associated with HRQoL. Among YAs, there were no associations between perceived adult status, social milestones, or covariates and HRQoL (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Generalized linear models examining predictors of health-related quality of life.

| Parameter | Estimate (unstandardized) | Standard error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging adults | |||

| Intercept | 6.53 | 1.55 | <0.0001 |

| Perceived adult status | −0.89 | 0.25 | 0.0004 |

| Sex: Female | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.89 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.89 |

| Child-rearing: Raising child | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.95 |

| Marital: Partnered | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.75 |

| Educationa | |||

| ≤High school | −0.38 | 0.37 | 0.30 |

| Some college | −0.19 | 0.37 | 0.61 |

| Employmentb | |||

| Not working/student | −0.69 | 0.38 | 0.07 |

| Student | −0.03 | 0.34 | 0.93 |

| Unknown | −0.78 | 0.50 | 0.12 |

| Treatment status: Off | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.76 |

| Treatment historyc | |||

| Radiation only | −0.37 | 0.40 | 0.36 |

| Chemo only | −0.03 | 0.43 | 0.48 |

| Radiation + chemo | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.96 |

| Young adults | |||

| Intercept | 3.14 | 1.14 | 0.007 |

| Perceived adult status | −0.09 | 0.22 | 0.68 |

| Sex: Female | −0.39 | 0.24 | 0.11 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Child-rearing: Raising child | −0.04 | 0.28 | 0.90 |

| Marital: Married/cohabitating | 0.02 | −0.26 | 0.94 |

| Education | |||

| ≤ High school | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.79 |

| Some college | −0.23 | 0.29 | 0.44 |

| Employmentb | |||

| Not working/student | −0.13 | 0.37 | 0.70 |

| Student | −0.31 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| Unknown | −0.33 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| Treatment status: Off | −0.01 | 0.37 | 0.98 |

| Treatment historyc | |||

| Radiation only | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.79 |

| Chemo only | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| Radiation + chemo | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.23 |

Reference category = college degree or higher.

Reference category = working.

Reference category = surgery only.

3.4 |. Sensitivity analyses

Associations between perceived adult status and HRQoL did not differ substantially when participants who reported a treatment history of surgery-only (n = 31) were excluded from the analysis (Appendix B). Associations between our predictors of interest (i.e., perceived adult status, social milestones), covariates, and HRQoL were similar for EAs and YAs, with one exception: among YAs, there was a significant association between sex and HRQoL satisfaction such that female YAs reported lower satisfaction than male YAs (b = −0.53, SE = 0.24, p = 0.04; Appendix B).

4 |. DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to describe and examine perceived adult status as a developmental indicator among EAs and YAs with cancer. Distributions of perceived adult status were similar to the general population among both EAs and YAs,8 suggesting that having cancer does not change how AYAs perceive their own developmental status. Social milestones of marital status, child-rearing status, and employment were associated with perceived adult status among EAs but not YAs. In partial support of our hypothesis, perceived adult status was uniquely associated with HRQoL among EAs when accounting for marital, child-rearing, employment, and education status suggesting that perceived adult status may be a unique and useful developmental indicator for this age group.

EAs who were married, had children, or were working tended to perceive they had reached adulthood more often than EAs who had not reached these milestones. This finding contrasts with studies in the general population suggesting that EAs do not consider social role transitions necessary criteria for reaching adulthood.11–13 Though these milestones may not be necessary in and of themselves, they may be associated with other key markers of adulthood such as personal responsibility or financial independence. It is also possible that adult social roles such as marriage or parenthood may be more meaningful in the context of cancer compared to the general population as EAs with cancer may be limited in their opportunities to pursue other individualistic developmental goals associated with adulthood (e.g., equal relationship with parents). Social reference groups may explain why some milestones were associated with perceived adult status for EAs but not YAs. In the United States, the average age at first marriage for women and men is 28 and 30 years-old, respectively, and for having a first child is 30 and 31 years-old, respectively.21 Thus, EAs who reach these milestones precociously may be treated as adults at a younger age or feel more mature in reference to their peers who have yet to assume these responsibilities. Finally, as these associations were descriptive and not directional in nature, it is also possible that EAs who perceive they have reached adulthood are more likely to pursue adult social roles at an earlier age, or that these associations may be explained by third variables. Future studies should assess factors that AYAs with cancer consider important markers for adulthood to determine if they align with the general population or vary between EAs and YAs, as well as examine relations between social milestone achievements and perceived adult status longitudinally.

Perceived adult status was uniquely associated with HRQoL among EAs but not YAs such that EAs who reported lower perceived adult status had lower satisfaction with their HRQoL. This suggests that the developmental impact of cancer may be especially salient during emerging adulthood. Many EAs with cancer delay educational or career plans and remain dependent upon parents for support. This may limit their ability to achieve developmental goals of emerging adulthood such as exploring identity, establishing autonomy, or becoming self-sufficient—factors which EAs also consider important markers of maturity.11,12 Emerging adulthood is also associated with wide variability in life situation.8 For EAs with cancer, differences between their own and their peers’ lives may be especially salient and elicit commonly described feelings of being “left behind”.22–24 EAs who feel left behind by their peers and unable to progress toward developmental goals may then perceive they are less mature and feel less satisfied with their quality of life as a result.

Social milestone achievements were not associated with HRQoL among EAs or YAs when accounting for perceived adult status. This suggests that delays in social milestones among AYA survivors may not necessarily translate to HRQoL deficits. It is possible that social milestones may hold less or different value for the current generation due to shifts in cultural values and expectations and more flexible views of the life course.25 Given the increasing age of some social role transitions like marriage and parenthood,21,25 AYAs with cancer may also perceive they have more time to pursue these milestones in the future and be less distressed by their delay. Future studies examining AYAs’ social outcomes may also benefit from exploring other social milestones that are more proximal to developmental goals such as living independently or being financially self-sufficient, as these may be more meaningfully associated with HRQoL outcomes.

4.1 |. Study limitations

Some study limitations should be noted. First, data were collected from AYAs recruited using an anonymous, cross-sectional online research panel. Though data collected through online research panels have been shown to be comparable to data obtained from population-based estimates,26 we were unable to confirm accuracy of self-reported clinical information and limited in our ability to assess treatment history. Unexamined clinical factors such as time since diagnosis, age or developmental stage at diagnosis, treatment intensity, and transplant history may influence the developmental impact of cancer and should be considered in future research. In addition, AYAs with any stage of cancer were included in this study which may have influenced our findings. Though we conducted sensitivity analyses omitting AYAs with a treatment history of surgery only and controlled for treatment type, this may not have captured all AYAs with low stage cancers for whom the developmental impact of cancer may be different. Third, though our sample was representative in terms of race/ethnicity based on cancer incidence among AYAs,27 we did not have sufficient power to statistically examine racial or ethnic subgroup differences in our questions of interest. Finally, some measurement limitations should be considered. Perceived adult status was measured by a single item which assessed AYAs’ perceptions of the extent to which they had reached adulthood and may not have captured other more nuanced aspects of subjective developmental status. In addition, our assessment of AYAs self-reported sex provided a dichotomous response option (male or female) and thus did not account for the possible range of AYAs’ gender identities (e.g., non-binary, transgender). Relevant strengths of this study include our large sample size and proportion of male participants for observational AYA research, stratified sampling approach, and characterization of EAs as distinct from YAs.

4.2 |. Clinical implications

Together, these findings highlight the importance of AYAs’ subjective perceptions of their developmental status and the unique developmental needs of EAs with cancer. Given the critical role of exploration, independence, and identity development during emerging adulthood,8 disruptions in these areas may be especially salient and distressing for EAs with cancer. Assessing how EAs perceive their own maturity may help identify those experiencing greater developmental impact and at risk for poor HRQoL. As others have emphasized, mitigating developmental disruption is a critical goal for AYA researchers and clinicians.6,28–30 For EAs, identifying ways to promote autonomy, creating opportunities for identity development and role exploration, and encouraging self-sufficiency may bolster EAs perceived maturity during and after their cancer treatment. Important future directions include identifying modifiable factors that promote or limit perceived adult status for EAs with cancer and creating developmentally tailored supportive care programs that address their unique needs.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

This study contributes to broader understanding of developmental status among AYAs with cancer, suggesting that perceived adult status may be a useful indicator of developmental status for EAs with implications for HRQoL. Our findings support the importance of recognizing emerging adulthood and young adulthood as unique developmental periods within AYA research and care provision; underscore the unique developmental needs of EAs with cancer; and highlight the importance of using AYA perspectives to better understand the developmental impact of cancer.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded through a pilot grant from the Department of Medical Social Sciences at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Drs. Fladeboe, Rosenberg, and Salsman are currently supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (Fladeboe K99CA267481; Rosenberg: R01CA222486, R01CA225629, R01CA267107, R01CA269574; Salsman: R01CA218398, R01CA-242849). The opinions and content herein are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding organizations.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health; Feinberg School of Medicine

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to declare.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the senior author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sodergren SC, Husson O, Robinson J, et al. Systematic review of the health-related quality of life issues facing adolescents and young adults with cancer. Qual Life Res 2017;26(7):1659–1672. 10.1007/s11136-017-1520-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(17):2136–2145. 10.1200/jco.2012.47.3173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harju E, Roser K, Dehler S, Michel G. Health-related quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2018;26(9):3099–3110. 10.1007/s00520-018-4151-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husson O, Prins JB, Kaal SE, et al. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) lymphoma survivors report lower health-related quality of life compared to a normative population: results from the PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol 2017;56(2):288–294. 10.1080/0284186x.2016.1267404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson P, McDonald FE, Zebrack B, Medlow S. Emerging Issues Among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Elsevier; 2015: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Agostino NM, Penney A, Zebrack B. Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2329–2334. 10.1002/cncr.26043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Docherty SL, Kayle M, Maslow GR, Santacroce SJ. The Adolescent and Young Adult with Cancer: A Developmental Life Course Perspective. Elsevier; 2015:186–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 2000;55(5):469–480. 10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett JJ, Emerging adulthood (s). Bridging Cultural and Developmental Approaches to Psychology: New Syntheses in Theory, Research, and Policy; 2010:255–275. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reifman A, Arnett JJ, Colwell MJ. Emerging adulthood: theory, assessment and application. J Youth Develop 2007;2(1):37–48. 10.5195/jyd.2007.359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnett JJ. Learning to stand alone: the contemporary American transition to adulthood in cultural and historical context. Hum Dev 1998;41(5–6):295–315. 10.1159/000022591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: perspectives from adolescence through midlife. J Adult Dev 2001;8(2):133–143. 10.1023/a:1026450103225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharon T Constructing adulthood: markers of adulthood and well-being among emerging adults. Emerg Adulthood. 2016;4(3):161–167. 10.1177/2167696815579826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhoff AC, Yi J, Wright J, Warner EL, Smith KR. Marriage and divorce among young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6(4):441–450. 10.1007/s11764-012-0238-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunnes MW, Lie RT, Bjørge T, et al. Reproduction and marriage among male survivors of cancer in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: a national cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(3): 348–356. 10.1038/bjc.2015.455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner EL, Kent EE, Trevino KM, Parsons HM, Zebrack BJ, Kirchhoff AC. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2016;122(7):1029–1037. 10.1002/cncr.29866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulte FS, Chalifour K, Eaton G, Garland SN. Quality of life among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer in Canada: a Young Adults with Cancer in Their Prime (YACPRIME) study. Cancer. 2021;127(8):1325–1333. 10.1002/cncr.33372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone DS, Ganz PA, Pavlish C, Robbins WA. Young adult cancer survivors and work: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2017;11(6): 765–781. 10.1007/s11764-017-0614-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, Sugimura K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(7):569–576. 10.1016/s2215-0366(14)00080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park CL, Wortmann JH, Hale AE, Cho D, Blank TO. Assessing quality of life in young adult cancer survivors: development of the Survivorship-Related Quality of Life scale. Qual Life Res 2014;23(8): 2213–2224. 10.1007/s11136-014-0682-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bureau USC. Families and Living Arrangements; 2022. Accessed 10 5 2022. https://www.census.gov/topics/families.html [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong AW, Chang T.-t, Christopher K, et al. Patterns of unmet needs in adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: in their own words. J Cancer Surviv 2017;11(6):751–764. 10.1007/s11764-017-0613-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donovan E, Martin SR, Seidman LC, et al. The role of social media in providing support from friends for adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients and survivors of sarcoma: perspectives of AYA, parents, and providers. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2021;10(6):720–725. 10.1089/jayao.2020.0200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grinyer A The biographical impact of teenage and adolescent cancer. Chron Illness. 2007;3(4):265–277. 10.1177/1742395307085335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vespa J The Changing Economics and Demographics of Young Adulthood: 1975–2016. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US; …; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H, Cella D, Gershon R, et al. Representativeness of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system internet panel. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63(11):1169–1178. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott AR, Stoltzfus KC, Tchelebi LT, et al. Trends in cancer incidence in US adolescents and young adults, 1973–2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2027738. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zebrack B, Isaacson S. Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(11): 1221–1226. 10.1200/jco.2011.39.5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(32):4825–4830. 10.1200/jco.2009.22.5474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zebrack BJ. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2289–2294. 10.1002/cncr.26056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the senior author upon reasonable request.