Abstract

Parental monitoring is a construct of longstanding interest in multiple fields—but what is it? This paper makes two contributions to the ongoing debate. First, we review how the published literature has defined and operationalized parental monitoring. We show that the monitoring construct has often been defined in an indirect and nonspecific fashion and measured using instruments that vary widely in conceptual content. The result has been a disjointed empirical literature that cannot accurately be described as the unified study of a single construct nor is achieving a cumulative scientific character. Second, we offer a new formulation of the monitoring construct intended to remedy this situation. We define parental monitoring as the set of all behaviors performed by caregivers with the goal of acquiring information about the youth’s activities and life. We introduce a taxonomy identifying 5 distinct types of monitoring behaviors (Types 1–5), with each behavior varying along five dimensions (performer, target, frequency, context, style). We distinguish parental monitoring from 16 other parenting constructs it is often conflated with and position monitoring as one element within the broader parent-youth monitoring process: the continuous, dyadic interplay between caregivers and youth as they navigate caregivers attempts’ to monitor youth. By offering an explicit and detailed conceptualization of monitoring, we aim to foster more rigorous and impactful research in this area.

Keywords: parenting, parental monitoring, childhood, adolescence

1. Parental monitoring, 25 years later

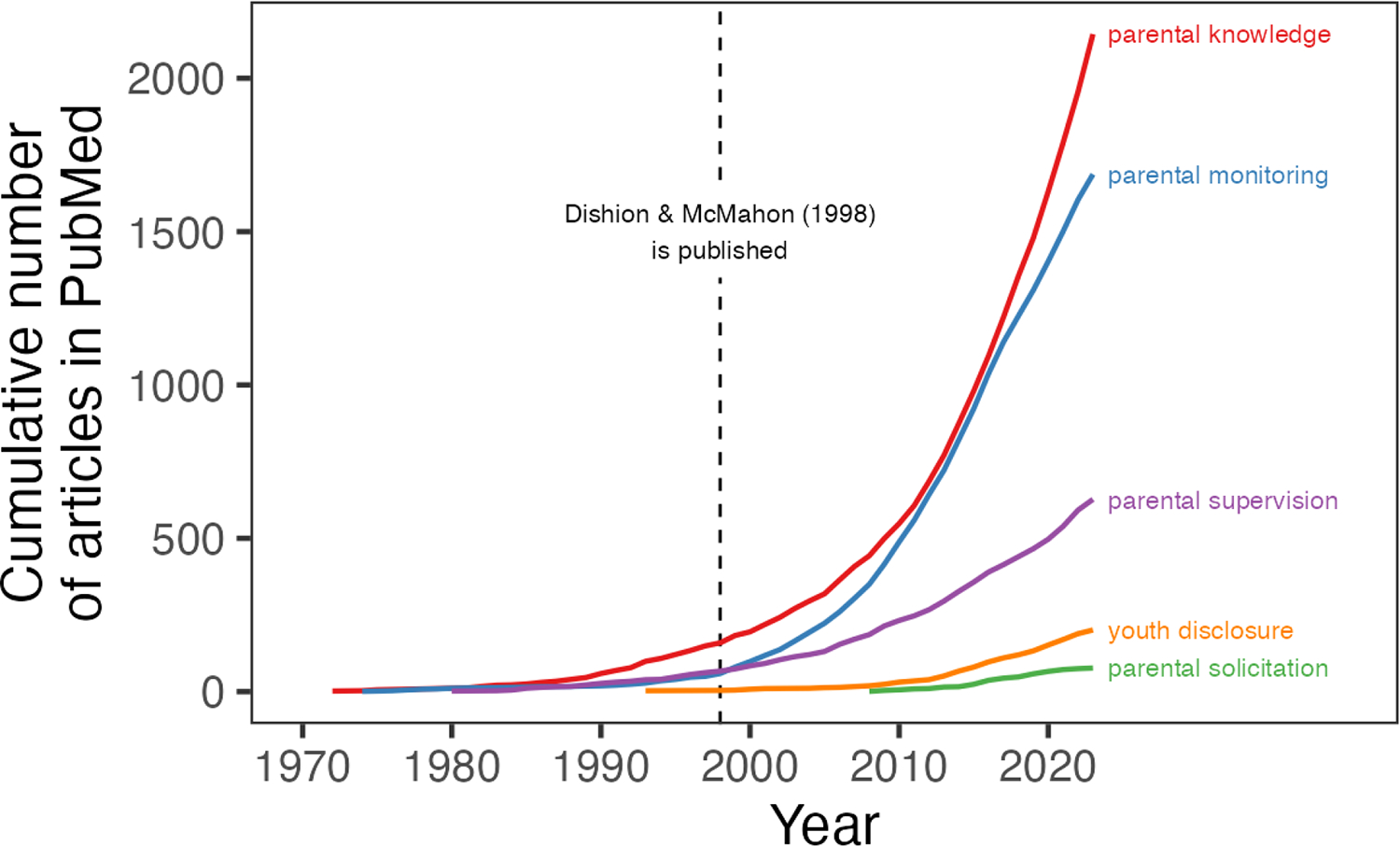

In the very first issue of Clinical Child Family and Psychology Review, Dishion and McMahon (1998) published a seminal paper formalizing “parental monitoring” as a construct of scientific and clinical interest. This paper spurred the consolidation and growth of research on the topic of parental monitoring into a literature now comprising several thousand articles (Figure 1). 25 years later, this paper revisits a fundamental topic of Dishion and McMahon’s landmark paper: What is parental monitoring? Dishion and McMahon offered the following definition:

“Monitoring of the child by parents is one component in the constellation of effective child-rearing practices. Parental monitoring includes both structuring the child’s home, school, and community environments, and tracking the child’s behavior in those environments. Parental monitoring is relevant to children’s adaptation from infancy into young adulthood and should be developmentally, contextually, and culturally appropriate. Positive parental social cognitions concerning monitoring are a necessary but not sufficient prerequisite for the successful implementation of parental monitoring practices.”

(p. 66)

Dishion and McMahon’s (1998) definition of monitoring remains the most widely cited today, with the article accumulating 2,127 citations at the time of writing.1 Yet as research on monitoring accelerated (Figure 1), the number of definitions proliferated. Reviewers of subsequent work on monitoring have all called attention to serious issues with construct definition and operationalization that hamper evaluation of the accumulated literature (Anderson & Branstetter, 2012; Crouter & Head, 2002; Ellis et al., 2008; Handschuh et al., 2020; Keijsers, 2016; Racz & McMahon, 2011; Stattin et al., 2010).

Figure 1. Publications Per Year Referencing Parental Monitoring and Related Terms in Title or Abstract, PubMed, 1970–2023.

Note. Based on search for each term occurring in titles and abstracts on PubMed. Search was performed on April 15, 2024 and restricted to articles published before or during 2023. Each search included alternative terms for “parental” (e.g., maternal) or “youth” (e.g., child) where applicable.

This paper makes two contributions. First, we review how the published literature has defined parental monitoring and document a stark lack of clarity and consistency that is impeding forward progress. Second, to remedy this situation, we propose a new formulation that re-casts parental monitoring as a set of parent behaviors organized into a taxonomy and each varying along 5 dimensions. The new formulation (1) yields a clear and consistent construct definition, (2) resolves or enables progress on six major questions in the literature, and (3) reveals holes in the evidence and directions for future research.

2. How has parental monitoring been conceptualized to date?

2.1. A brief history of research on parental monitoring

The notion that parental tracking and awareness of youths’ activities could be important has been around for a long time, existing in multiple fields under multiple names. The history can be told in three phases. In the first phase, criminologists pioneered the construct; in the second phase, clinical psychologists expanded and formalized it; and in the third phase, developmental psychologists re-interpreted it.

The construct of parental monitoring first emerged in criminology under the label “parental supervision.” As early as the 1950s, criminologists were linking low supervision of young boys to risk of delinquency (Glueck & Glueck, 1950), a finding replicated in several long-term prospective studies designed to identify the antecedents of crime (e.g., McCord, 1979; Robins, 1966; West & Farrington, 1977). This early work tended to offer a narrow, literal conceptualization of monitoring as the parent being with and keeping a close eye on the child or leaving them in the care of another responsible adult. For example, Glueck and Glueck (1950) characterize whether or not a mother was working outside the home as a measure of parental supervision, a choice implying that monitoring youth simply means being in the same place as them.

The second phase of monitoring research began when Patterson and colleagues brought the construct to the attention of clinical psychologists. In a landmark book (Patterson, 1982) and subsequent article in Child Development (Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984), Patterson gave the construct a new, broader label—“monitoring”—and simultaneously expanded its conceptual scope. For Patterson, monitoring was not just keeping an eye on your child, but a “family management practice” that involved multiple facets: awareness of your child’s whereabouts, setting and enforcing expectations about when to be home after school, checking that they finished chores and noticing when they break the rules, and establishing regular and nonjudgmental sharing information about each others’ lives. Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber (1984) collected data showing that parental monitoring held stronger links to delinquency among adolescent boys than did traditionally researched parenting practices such as reinforcement, discipline, and problem solving, piquing the interest of other psychologists.

Over the next 15 years, other research groups began linking monitoring to other forms of youth adjustment, in older and younger youth, and in girls as well as boys (e.g., Chilcoat & Anthony, 1996; Kolko & Kazdin, 1990). As evidence accumulated, it became clear that monitoring was an important aspect of parenting with applicability to many contexts and populations beyond its original roots in criminology. Dishion and McMahon’s (1998) landmark paper in CCFPR represented the culmination of this second phase of monitoring research, canonizing the “parental monitoring” construct with a centralized, citable label and formulation that spanned multiple fields, forms of youth adjustment, and developmental periods.

Yet the consolidation was short-lived. Two years later, the third phase of monitoring research began with the publication of two major papers by Stattin and Kerr (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Stattin & Kerr, 2000) that split the field in two. Stattin and Kerr called for a “re-interpretation” of the monitoring construct, making a two-step argument. First, they showed that upon closer inspection, the measures being used to assess monitoring in the emerging literature were mislabeled. The survey items on measures of “monitoring” almost always asked about parental knowledge of youth activities (e.g., “How often do your parents know where you go?”) rather than the actions parents performed to gain that knowledge (e.g., “How often do your parents ask you where you’re going?”). Thus, the literature emerging since Patterson’s work had actually been linking parental knowledge, not monitoring understood as parent action, to youth adjustment. Second, motivated by this observation, Stattin and Kerr investigated the predictors of parental knowledge, finding that youth disclosure of information was a stronger predictor of knowledge than were parent actions to acquire information. Based on these findings, they argued for a reinterpretation of the monitoring construct that emphasized the active role of youth, minimized the active role of the parent, and suggested that parents focus on facilitating youth disclosure of information rather than seeking that information themselves.

Stattin and Kerr’s papers sparked a bifurcation of the literature on monitoring, with the resulting camps corresponding roughly to the fields of clinical and developmental psychology (Aks et al., 2024). Clinical psychologists in large part ignored Stattin and Kerr’s argument, continuing to emphasize parent action when conceptualizing and studying parental monitoring. For example, clinical interventions for problem behavior still focus on increasing parents’ monitoring behaviors, not facilitating youth disclosure (Schwarz-Torres et al., 2024). In contrast, developmental psychologists reacted by turning their attention to other elements of the monitoring process and significantly expanding the conceptual scope of inquiry. Substantial literatures emerged on how youths’ voluntary disclosure of information (e.g., Smetana et al., 2019, 2023), youths’ secrecy, concealment, and lying (e.g., Frijns et al., 2010; Smetana et al., 2019), and parents’ affective reactions to youths’ problem behavior (e.g., Kerr et al., 2008; Kerr & Stattin, 2003) interact with parental monitoring and independently predict youth adjustment.

The divide opened by Stattin and Kerr’s papers remains today. Monitoring research tends to be conducted either by those who view it as a parent-directed process or those who view it as a child-directed process, with construct definitions differing accordingly. Yet this dichotomy is simplistic and obscures the heterogeneity present within each camp. Thus, with the basic narrative backdrop in place, we now undertake a more comprehensive assessment of how parental monitoring is being conceptualized today. We use two strategies: first, we analyze the construct definitions offered in 29 seminal articles on monitoring, and second, we analyze the scale structure and item content of 39 scales being used to measure monitoring.

2.2. Analyzing construct definitions in seminal articles

We extracted the construct definitions offered in 29 seminal articles on monitoring (including those discussed in the prior section). The first, second, and sixth authors have expertise on parental monitoring and worked together to select the articles. We included every review article or major theoretical statement that we were aware of. We then added highly-cited and influential empirical studies, ensuring that all major camps of monitoring research were represented in the resulting list before proceeding.

Table 1 lists the articles reviewed and gives quotations from each that best captured its definition of parental monitoring. Comparison of the extracted definitions yielded three findings. First, most articles did not include an explicit definition of the monitoring construct. Rather, most defined monitoring indirectly, such as by describing what “good” monitoring looks like (Crouter & Head, 2002; Gabriels, 2016), explaining the “function” of monitoring (e.g., Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2010) or what it “relies on” (e.g., Ceballo et al., 2003), identifying important “aspects of monitoring” (e.g., DiClemente et al., 2001; Dittus et al., 2015), or listing what monitoring “includes” (e.g., Gentile et al., 2014) or “incorporates” (e.g., Li et al., 2000). Because the articles did not assert directly what monitoring is, it is difficult to determine the boundaries of the offered definitions.

Table 1.

Definitions of Parental Monitoring in a Selection of the Seminal Articles Reviewed

| Article | Definition of parental monitoring |

|---|---|

| (Patterson, 1982) |

|

| (Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984) |

|

| (Dishion & McMahon, 1998) |

|

| (Li et al., 2000) |

|

| (Stattin & Kerr, 2000) |

|

| (DiClemente et al., 2001) |

|

| (Crouter & Head, 2002) |

|

| (Borawski et al., 2003) |

|

| (Ellis et al., 2008) |

|

| (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2010) |

|

| (Racz & McMahon, 2011) |

|

| (Gentile et al., 2012) |

|

| (Anderson & Branstetter, 2012) |

|

| (Dittus et al., 2015) |

|

| (Gabriels, 2016) |

|

Note. Each row of the table lists the definition(s) of parental monitoring offered in a single article. When an article did not offer an explicit definition, we chose the text that came closest to doing so (e.g., described examples of monitoring). The article by Guilamo-Ramos et al. (2010) is a chapter in which six experts on parental monitoring were asked to explain their own construct definition-for this reason, each quotation is followed by the name of the expert who offered the quoted perspective. For brevity, this table lists 12 of the 29 total articles we reviewed for definitions–Table S1 includes the definitions of the remaining articles (Ceballo et al., 2003; Fletcher et al., 2004; Hayes et al., 2003; Jacobson & Crockett, 2000; Keijsers, 2016; Laird & Marrero, 2010; Omer et al., 2016; Smetana, 2008; Smetana & Daddis, 2002; Stanton et al., 2000; Stattin et al., 2010; Steinberg et al., 1994; Weintraub & Gold, 1991; Willoughby & Hamza, 2011).

Second, construct definitions were often expansive. Articles described monitoring as tracking youths’ activities (e.g., Dishion & McMahon, 1998), knowing about youths’ activities (e.g., Jacobson & Crockett, 2000; Smetana, 2008), directly supervising youth (e.g., Ceballo et al., 2003; Li et al., 2000), communicating with youth (e.g., Crouter & Head, 2002; Stanton et al., 2000), structuring the youths’ environment (e.g., Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Racz & McMahon, 2011), setting and enforcing rules for youth (e.g., Dittus et al., 2015; Willoughby & Hamza, 2011), negotiating and problem-solving (e.g., Borawski et al., 2003), and an aspect of the parent-child relationship (e.g., Borawski et al., 2003; Crouter & Head, 2002). Most articles described monitoring as encompassing more than one of these concepts.

Third, construct definitions were inconsistent across articles. The degree of inconsistency is difficult to assess precisely because the definitions were rarely explicit. However, there were two repeated points of disagreement. First, some articles defined parental monitoring as either entirely comprising (e.g., Jacobson & Crockett, 2000) or including parental knowledge (e.g., Smetana, 2008) whereas other articles excluded parental knowledge from the construct definition (e.g., Stattin et al., 2010; Willoughby & Hamza, 2011). Second, some articles defined parental monitoring as a behavior performed by parents (e.g., Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2010) whereas other articles defined monitoring as a dyadic behavior or process performed by both parent and youth (e.g., Crouter & Head, 2002; Gabriels, 2016).

2.3. Analyzing item content on scales used to measure monitoring

We collected 309 items from 20 instruments containing 39 total scales used to measure parental monitoring in published work.2 To identify measures, we began with the 6 instruments located in a recent systematic review of monitoring instruments (Handschuh et al., 2020) then added further instruments located via several other strategies. The first, second, and sixth authors added instruments they were aware of given their expertise in parental monitoring. The first author searched Google Scholar and reviewed results to identify any other instruments in existence (search string: “‘parental monitoring’ (survey | scale | questionnaire)”). The first author also emailed prominent authors in the field to ask if they knew of instruments we had missed.

Table 2 lists the 20 instruments and gives citations. We inspected the scale format (e.g., instructions, response scale), then the item content, then how items were combined into scales. Inspection of the scale format showed that monitoring is conceptualized as perceivable by both parents and youth, best measured as a frequency, and stable over several months. 14 scales were to be completed only by youth, 9 only by parents, and 16 by youth or parents. Almost all scales (34 out of 39) measured parental monitoring by asking the youth or parent to rate the frequency of an occurrence or how often a statement was true along a Likert scale (e.g., never to always). 30 scales did not specify the timeframe they were asking about, presuming monitoring to be stable over time. 9 scales specifying a timeframe of the past 1–6 months.

Table 2.

Rating Scales Used to Measure Parental Monitoring

| Citation | Instrument | Abbreviation | Scale | Informant | # items | Concepts from Table 3 measured on items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essau et al., 2006 | Alabama Parenting Questionnaire | APQ | Poor monitoring/ supervision | Youth/Parent | 10 | 5, 11,13, 16, 17, 18, 21 |

| Arthur et al., 2002 | Communities that Care Youth Survey | CCPFM | Poor family management | Youth | 8 | 2, 6, 7, 9, 11 |

| Weisskirch, 2011 | Adolescent-Family Process Measure | AFPM | Monitoring | Youth/Parent | 5 | 11 |

| Weisskirch, 2009 | Cell Phone Parenting | CPP-T | Truthfulness | Youth/Parent | 7 | 15 |

| CPP-PC | Parent initiated calls | Youth/Parent | 23 | 1, 2, 6, 19 | ||

| CPP-AC | Adolescent initiated calls | Youth/Parent | 18 | 13, 14, 18, 19 | ||

| Dishion & Loeber, 1985 | Parent Monitoring | DL-PM | N/A | Youth/Parent | 7 | 11, 12, 13, 20 |

| Waizenhofer et al., 2004 | Methods of Obtaining Knowledge | MOK | N/A | Parent | 20 | 2, 4, 19 |

| Capaldi & Patterson, 1989 | Oregon Youth Study Parental Monitoring Scale | OYS-PMR | Parent report on monitoring rules | Parent | 10 | 9, 11, 13, 19 |

| OYS-CMR | Child’s report on monitoring rules | Youth | 6 | 13, 15, 18 | ||

| OYS-CMP | Child’s report of parents’ monitoring practices | Youth | 5 | 1 | ||

| OYS-CME | Child’s monitoring expectancies | Youth | 4 | 5, 7, 9 | ||

| Pettit et al., 1999 | Parental Monitoring and Supervision | P-PMS | N/A | Parent | 9 | 11, 15, 16, 19, 21 |

| Steinberg et al., 1994 | Parental Monitoring and Peer Influences on Adolescent Substance Use | PMPI | N/A | Youth | 10 | 10, 11 |

| Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2019 | Parental Monitoring- Self-Report about own Parenting Behavior | PMSR-KS | Knowledge solicitation | Parent | 5 | 10 |

| PMSR-RS | Rule setting | Parent | 5 | 5, 7 | ||

| Cottrell et al., 2007 | Parental Monitoring Instrument | PMI-IM | Indirect monitoring | Youth/Parent | 7 | 4, 21 |

| PMI-DM | Direct monitoring | Youth/Parent | 3 | 1 | ||

| PMI-SM | School monitoring | Youth/Parent | 4 | 2, 4, 19 | ||

| PMI-HM | Health monitoring | Youth/Parent | 4 | 2, 19 | ||

| PMI-CM | Computer monitoring | Youth/Parent | 4 | 3, 8 | ||

| PMI-PM | Phone monitoring | Youth/Parent | 2 | 8 | ||

| PMI-RM | Restrictive monitoring | Youth/Parent | 3 | 3 | ||

| Karoly et al., 2016 | Parental Monitoring Questionnaire | PMQ | N/A | Youth | 5 | 11, 13, 18, 19, 20 |

| Small & Kerns, 1993 | Parental Monitoring Scale | PMS | N/A | Youth | 8 | 5, 11, 12, 13 |

| Swaim & Stanley, 2022 | Parental Monitoring Short Scale | PMSS-PK | Parental knowledge | Youth | 3 | 11 |

| PMSS-PC | Parental control | Youth | 3 | 5, 7 | ||

| PMSS-PS | Parental solicitation | Youth | 3 | 1, 4 | ||

| PMSS-CD | Child disclosure | Youth | 3 | 15 | ||

| Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2019 | Parental Monitoring of Technology-Self-Report about own Parenting Behavior | PMTSR-TD | Technology discourse with child | Parent | 6 | 19 |

| PMTSR-MT | Monitoring of child’s technology use | Parent | 7 | 3, 8, 20 | ||

| Kerr & Stattin, 2000 | Stattin & Kerr Scales | S&K-KS | Knowledge scale | Youth/Parent | 8–9a | 11 |

| S&K-SS | Solicitation scale | Youth/Parent | 5–6a | 1, 4, 19 | ||

| S&K-CS | Control scale | Youth/Parent | 5–6a | 5, 7, 10 | ||

| Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2019 | Supervision Questionnaire | SQ-PC | Primary Caregiver | Parent | 20 | 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 21, 23 |

| SQ-C | Child | Youth | 18 | 5, 9, 11, 13, 17, 18, 19 | ||

| Yang, Lippold, & Stouthamer., 2022 | Parental Monitoring | YLS-PM | N/A | Parent | 5 | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Aber et al., 2021 | Parental Active Tracking Efforts | PATE | N/A | Youth | 19 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 21 |

| Glynn et al., 2019 | Questionnaire of Unpredictability in Childhood | QUIC | Parental monitoring and involvement | Youthb | 9 | 1, 2, 11, 19, 20, 22 |

Note. The numbers in the “Concepts asked about on items” column correspond to the numbering of concepts in Table 3.

The parent- and youth-completed forms have a different number of items.

This scale is intended for adults to complete retrospectively, describing their own childhood.

Inspection of the item content showed that monitoring is conceptualized as spanning multiple domains, being stable across contexts, and encompassing many different concepts. Scale items typically asked about behavior and functioning in many contexts (e.g. home, school, afterschool, friend’s house, free time, weekends, evenings). Scale items typically asked about general patterns of behavior, rather than about behavior under certain conditions or in certain circumstances. An exception would be items that asked specifically about what happens when the youth is home alone or the youth is leaving the house without the parent.

We identified 23 distinguishable concepts tapped across the 309 items. Table 3 lists the concepts and gives examples of items tapping each. Every concept invoked in the theoretical definitions of monitoring reviewed in Section 2.2 was tapped by at least some items in the item pool. In addition, there were items asking about additional concepts not present in any of the theoretical definitions, such as about the youth keeping secrets, the youth following rules, or time spent together by the parent and youth.

Table 3.

23 Concepts Present in 309 Items from Rating Scales Used to Measure Parental Monitoring

| # | Concept | Examples of items tapping concept | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item wording | Source | ||

| 1 | The parent asking the youth about plans, behaviors, feelings, or past events | “How many times has your parent asked you what happened after planned activities?” | PMI-DM |

| “How often have you discussed with your child his/her plans for the coming day?” | SQ-PC | ||

| 2 | The parent checking on the youth’s behavior (e.g., looking at homework) | “How many times have you checked to make sure [youth] completed homework?” | PMI-SM |

| “How often do you call your teen to verify that your teen is doing what he/she said he/she would be doing?” | CPP-P | ||

| 3 | The parent perusing the youth’s belongings, space, or phone | “[How often do you] check the content of your child’s devices/social media accounts” | PMTSR-MT |

| “How many times has your parent looked through your drawers or closets?” | PMI-RM | ||

| 4 | The parent communicating with the youth’s friends, other adults, or neighbors | “How many times has your parent contacted your friends’ parent(s) to talk to them?” | PMI-IM |

| “How often do your parents talk to your friends when they come to your house? (Ask what they do, how they think and feel about different things)” | S&K-SS | ||

| 5 | The parent setting, communicating, and enforcing rules about going out, staying out, and curfews | “Do you need to have your parents’ permission to stay out late on a weekday evening?” | S&K-CS |

| “Do you have a set time to be home on school nights?” | SQ-C | ||

| 6 | The parent setting, communicating, and enforcing rules about problem behavior (e.g., drinking) | “My family has clear rules about alcohol and drug use.” | CCPFM |

| “How often do you call your teen to deliver punishment or discipine?” | CCPFM | ||

| 7 | The parent setting rules about where the youth can go and with whom the youth can spend time | “How often do you set rules or limits on who your child spends time with?” | PMSR-RS |

| “I talk to my child’s friend’s parents before he/she can spend the night at their house for the first time” | YLS-PM | ||

| 8 | The parent setting limits on phone use, internet use, and computer time | “How many times has your parent placed computer in an open area where it can be observed?” | PMI-CM |

| “How many times has your parent set limits for phone calls?” | PMI-PM | ||

| 9 | The likelihood that a parent would catch an instance of problem behavior (e.g., drinking) | “If you carried a handgun without your parents’ permission, would you be caught by your parents?” | CCPFM |

| “If you did not come home by the time that you were supposed to be in, would your [parent] know?” | SQ-C | ||

| 10 | The parent’s unspecified efforts to know things | “How much do you try to know who your child spends time with?” | PSMR |

| “How much do your parents try to know what you do with your free time?” | PMPI | ||

| 11 | The parent’s knowledge about the youth’s activities, companions, and whereabouts | “Do you know what your child is doing on his/ her free time?” | S&K-KS |

| “Where is your child usually in the evening?” | SQ-PC | ||

| 12 | The parent’s perceived importance and/or difficulty of having knowledge about the youth’s location and activities | “Is it important to you to know what your child is doing when he/she is outside of the home?” | SQ-PC |

| “How important do you think it is to know where your child is?” | DL-PM | ||

| 13 | The youth telling parents about activities, events, and feelings | “How often do you talk to your parent or guardian about your plans for the coming day, such as your plans about what will happen at school or what you are going to do with friends?” | PMQ |

| “How often do you call your parent to tell him/her about something good that happened or when you are happy about something?” | CPP-A | ||

| 14 | The youth seeking the counsel of parents | “How often do you call your parent to ask a question about something?” | CPP-A |

| “When you have a problem, who do you usually go to?” | DL-PM | ||

| 15 | The youth keeping secrets or telling the truth | “How truthful are you about your whereabouts when you speak to your parent by cell phone?” | CPP-T |

| “I keep secrets from my parents about what I do in my free time” | PMSS-CD | ||

| 16 | The youth following rules about going and staying out and curfews | “You stay out in the evening past the time you are supposed to be home.” | APQ-PM/S S |

| “You go out without a set time to be home.” | APQ-PM/S S | ||

| 17 | Where the youth goes and with whom the youth spends time | “Where do you usually stay in the evening?” | SQ-C |

| “Where do you usually go after school?” | SQ-C | ||

| 18 | Whether the youth knows how to reach the parent and where the parent is when the parent is not home | “How often know how to reach parents if they’re out” | OYS-CMR |

| “Your parents leave the house and don’t tell you where they are going.” | APQ-PM/SS | ||

| 19 | The frequency of the parent-youth communication | “How often [do you] talk to parents about daily plans?” | OYS-CMR |

| “I talk to my parent(s) about the plans I have with my friends” | PMS | ||

| 20 | Time spent together by parent and youth | “How often do you spend time with your parent(s)?” | DL-PM |

| “Frequency do shared activities together with your child online or on social media” | PMTSR-MT | ||

| 21 | An adult being present with youth | “When [youth name] is at a friend’s house, how often do you think that a parent or another adult is there? | P-PMS |

| “You go out after dark without an adult with you.” | APQ-PM/SS | ||

| 22 | The youth having established routines | “I had a set morning routine on school days (i.e., I usually did the same thing each day to get ready)” | QUIC |

| “I had a set bedtime routine (e.g., my parents tucked me in, my parents read me a book, I took a bath)” | QUIC | ||

| 23 | Parent’s perception of the influence of the youth’s friends on the youth | “do you feel that your child’s friends have a good influence on his/her behavior?” | SQ-PC |

| “do you feel that your child’s friends have a bad influence on his/her behavior?” | SQ-PC | ||

Note. See Table 2 column “Abbreviation” to identify the scales listed in the “Source” column.

Finally, inspection of how items were combined into scales showed that developers hold different conceptualizations of monitoring, ranging from a narrow set of certain behaviors to a broad characterization of the state of a family’s home life. While a few scales assessed a single concept (11 out of 39), most scales assessed several concepts at once (see rightmost column of Table 2). An example of the single-concept approach is the 3-item “direct monitoring” subscale of the Parental Monitoring Instrument (Cottrell et al., 2007), which asks the youth how many times the parent has talked to them about what the youth had planned, about the specifics of planned activities, or about what happened after planned activities. An example of the several-concept approach is the “poor monitoring/supervision” subscale of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Essau et al., 2006), which asks youth how often they are home alone, how well their parents know their friends, and how often youth violate a set curfew, along with further concepts.

3. How issues of construct definition obstruct forward progress

So, what is parental monitoring? Our review of the literature in Section 2 showed that the field does not have a consistent or clear answer to this question. Theoretical definitions are typically indirect, often expansive, and sometimes contradictory across seminal publications. Operationalizations on rating scales are even more expansive, with item content tapping at least 23 distinguishable concepts and the breadth of the construct varying substantially across scales.

Today, authors are writing about monitoring with very different conceptualizations in mind. A pair of studies ostensibly both about monitoring are often measuring it using scales with partially or even entirely non-overlapping content. Arguments and evidence often blur the lines between the narrow concept of tracking youths’ activities and whereabouts and related concepts like knowledge, communication, disclosure, rules, discipline, and norms. Indeed, our findings question the notion that there really is a literature on parental monitoring. Work on monitoring to date is probably better regarded as a complex set of literatures, each one theorizing and measuring a somewhat different amalgam of concepts.

As seen in our sketch of the field’s history (Section 2.1), two of the largest and most sustained controversies about monitoring pertain directly to the construct definition. Is parental knowledge a part of the monitoring construct? Is monitoring a parent behavior or a dyadic interaction between parents and youth? These are fundamental and unresolved questions that have left the field divided. Furthermore, other arguments that appear superficially unrelated to the construct definition in fact cannot be resolved without first agreeing about what parental monitoring is. We can name at least four such examples.

First, is parental monitoring a cause or merely a correlate of youth adjustment? Some argue that the relationship is causal, so that parents should be advised to monitor youth and clinicians should seek to improve parents’ monitoring when treating at-risk youth (Schwarz-Torres et al., 2024). Others argue that the relationship is spurious, owed to confounding variables, so that parents and clinicians should turn their attention to other factors besides monitoring (Keijsers et al., 2016). Resolving this debate empirically will require first deciding what comprises monitoring, whose effects on adjustment we are trying to estimate, versus what comprises a confounding variable that needs to be controlled for. For example, if parental knowledge is part of the monitoring construct, then estimating the effects of monitoring using a measure that conflates monitoring and knowledge is perfectly appropriate. But if parental knowledge is not a part of the monitoring construct, then parental knowledge is instead an important confounding variable to control for in order to avoid spurious results.

Second, is more monitoring always better? Some argue the answer is no: that monitoring can sometimes be received by youth as invasive or controlling, ultimately backfiring (Laird et al., 2018), or that many of the behaviors associated with monitoring are also associated with constructs recognized as negative, such as overprotective parenting or helicopter parenting (Ellis et al., 2008). However, some definitions of monitoring explicitly exclude invasive or controlling behaviors from the construct, suggesting that when monitoring becomes too invasive, it simply ceases to be monitoring. Resolving this debate will require first deciding what counts as monitoring. Does a given behavior count as monitoring in all contexts?

Third, how much does the monitoring process vary across families? Most research has studied monitoring using methods that assume the monitoring process is the same in all families (Keijsers et al., 2016). Others have argued that the monitoring process may vary greatly, even allowing for the direction of effects to be opposite in a given pair of families (Frijns et al., 2020). Resolving this debate will require first deciding what it is that would vary across families. Is monitoring a behavior, such that we could measure the rates and compare them across families to assess differences? Or is monitoring a relationship property, such that the rate of underlying behaviors could differ greatly across families even as the relationship property remains the same?

Fourth, how does monitoring unfold over time? Most research has studied monitoring using methods that assume the monitoring process is highly stable over time and has long-lasting effects (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). Others have argued that monitoring may fluctuate rapidly and have acute effects detectable only in intensive longitudinal data (Pelham et al., 2023). Resolving this debate will require first deciding what it is that would vary over time. Is monitoring about directly supervising the youth, in which case it likely varies from moment-to-moment as parents and youth come in and out of contact? Or is monitoring about setting rules and imposing structure, in which case day-to-day changes are unlikely?

3.1. The need for a new approach

In summary, the lack of a clear and consistent conceptualization of parental monitoring is making it difficult to study it. Picture science as the construction of a tower: scientists laying brick upon empirical brick in an orderly fashion, all right angles and flush connections, building upon one another’s findings and elevating the structure to progressively greater heights. Today, the science of monitoring does not resemble that idealized image. Rather than using bricks, study-to-study differences in definition and measurement leave scientists of monitoring working with irregular stones. The stones fit together sometimes, but the foundation is precarious, and there are frequent setbacks when a column turns out to be unstable and topples over. And rather than a single tower, scientists of monitoring are working on several different structures in parallel, often with minimal communication and sometimes even with different construction materials that are fundamentally incompatible. It seems unlikely that a sturdy and cumulative structure will emerge from this pattern of work.

The next section proposes a new formulation of the parental monitoring construct intended to remedy this situation and enable the construction of a more rigorous, unified, cumulative science of parental monitoring. Development of the new formulation was guided by the problems observed in the prior literature. First, to improve clarity, we define parental monitoring explicitly and describe how it differs from and overlaps with closely related constructs. Second, to improve consistency, we propose a comprehensive taxonomy of parental monitoring behaviors that integrates the construct’s many different facets that have been explored in prior work.

4. A new formulation of parental monitoring

4.1. What is parental monitoring?

We define parental monitoring as follows:

Parental monitoring refers to the set of all behaviors performed by caregivers with the goal of acquiring information about the youth’s activities and life

(e.g., whereabouts, companions, events, stressors, behaviors).

Our definition has two key innovations. The first innovation is to put “acquiring information” at the heart of the definition. Monitoring behaviors vary greatly in form—from keeping a close eye on youth, to asking about their day, to getting to know their friends’ parents—as well as across contexts and developmental stages. What such phenotypically diverse behaviors actually share in common is the goal of acquiring information.3 The goal of acquiring information is also what makes monitoring unique relative to other parenting behaviors—it is often an antecedent or precondition to further action, rather than an endpoint. Moreover, the phrase “acquiring information” closely matches the meaning of the English verb to monitor as to “watch, keep track of, or check usually for a special purpose” (Merriam-Webster, 2023), preserving a strong correspondence between the label and the underlying construct.

The second key innovation of our definition is defining parental monitoring as a set of concrete behaviors. In contrast to some prior formulations, parental monitoring is not a state of being, an attribute of a family, or a relationship property, but a behavior performed by a person, in a place, at a point in time. Defining parental monitoring as a behavior has several benefits.

First, determining what is versus is not parental monitoring is straightforward. A given behavior can be compared to our definition and a determination can be made about whether that particular behavior meets criteria to be considered “parental monitoring.” In contrast, more indirect or impressionistic definitions of monitoring leave the boundaries of the construct unclear, sowing confusion and making communication more difficult.

Second, parental monitoring corresponds to discrete, observable, physical occurrences, making it straightforward to conceptualize, measure, and analyze. Techniques for measuring and analyzing behavior are well-established (Fisher et al., 2021). In contrast, when monitoring is defined as a more diffuse phenomenon, how to operationalize and analyze it remains fuzzy.

Third, a tight connection is forged between the basic science of monitoring and its clinical applications. Scientists study parent behaviors and determine their effects on the youth; then, clinicians change those parent behaviors in the ways the scientists determined most optimal to promote youth adjustment (e.g., increase their frequency, alter when they are performed). In contrast, when monitoring is conceptualized more hazily as a dyadic process or relationship property, it is not clear how findings in basic science should be translated into clinical practice. Clinicians must make a longer chain of inferences, guessing at the parent behaviors they should change to produce the recommended changes in the dyadic process or relationship property.

4.2. Parental monitoring is one element of a broader parent-youth monitoring process

We distinguish parental monitoring from the parent-youth monitoring process. “Parental monitoring” is always a behavior performed by the parent, never the youth and never the dyad. Thus, parental monitoring is not a “dyadic process,” “dyadic construct,” “dyadic behavior,” the “interplay between parents and youth,” or “communication patterns between parents and youth,” to choose a few common phrases.

We then use the label “parent-youth monitoring process” to refer to something broader and more complex: the continuous, dyadic interplay between caregivers and youth as they navigate caregivers attempts’ to monitor youth. Parental monitoring is just one of several elements in the parent-youth monitoring process, along with other elements like parental knowledge, youth disclosure, and youth secrecy (Figure 4). By replacing “parental” with the hyphenated “parent-youth,” we better capture that the construct is defined by the actions of both agents and create a parallelism with other dyadic constructs such as parent-child relationship quality or parent-child communication. By adding the word “process,” we connote the dynamic, bidirectional, ongoing nature of the phenomenon.

Figure 4. Parental Monitoring as One Element Within the Parent-Youth Monitoring Process.

Note. The figure depicts our perspective that there are likely bidirectional effects between all elements in the parent-youth monitoring process. Bidirectional effects between non-adjacent boxes (e.g., youth disclosure and youth adjustment) are omitted only to improve readability. The list of included elements is not meant to be exhaustive; the parent-youth monitoring process could be further elaborated with constructs like trust (Kerr et al., 1999) or the perceived legitimacy of parent authority (LaFleur et al., 2016).

We have two reasons for making this distinction and insisting that parental monitoring refer only to behaviors performed by parents. The first reason is semantic: the label “parental monitoring” connotes that the parent is the one performing the monitoring. Requiring that parental monitoring is performed only by the parent results in a better match between the construct label and construct definition (Stattin et al., 2010).

The second reason is technical: when parental monitoring refers only to parent behaviors, we are better positioned to separate what parents and youth each bring to the monitoring process. Youth behavior is both a cause of and reaction to parents’ monitoring (Frijns et al., 2020; Rote & Smetana, 2018). Yet theorizing and studying the bidirectional links between parent and youth actions over time requires first maintaining a firm conceptual distinction between them.

Some argue that because youth contribute to the monitoring process, monitoring must be defined as a dyadic construct (e.g., Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2010). We disagree. Most if not all phenomena that occur in families are dyadically determined: Parent behavior affects youth behavior, youth behavior in turn affects parent behavior, and so on (Sameroff, 2014). Yet the fact that a behavior is dyadically determined does not imply that it must be dyadically defined, or that the contributions of each dyad member cannot be distinguished.

This point is seen readily by analogy to a context other than monitoring. Child depression is in part caused by maladaptive parenting behaviors, and a child being depressed in turn evokes changes in how parents parent him or her (Restifo & Bögels, 2009; Sheeber et al., 2001). Yet no scientist would argue that child depression is a dyadic construct, or that items measuring parenting should be combined with survey items measuring the child’s depressive symptoms into a single score then labeled “child depression.” Scientists recognize that parents’ parenting and children’s depression each affect the other even while studying them as independent constructs.

4.3. Our definition of parental monitoring is non-evaluative

We define parental monitoring in a non-evaluative fashion, without reference to whether the underlying behaviors are effective, appropriate, or adaptive. There are three advantages to separating the behavior itself from evaluations of the behavior. First, we avoid conflating the behavior with its outcome, better positioning us to determine the effects of monitoring behaviors. For example, a monitoring behavior remains a monitoring behavior whether or not it yields accurate information, elicits disclosure from youth, or is received poorly by youth. Second, we avoid introducing definitional instability such that the same behavior counts as monitoring in one context but not another, due to differing appropriateness. For example, setting a rule that the youth cannot leave the home without an adult is still a monitoring behavior whether performed for a 5-year-old, for whom it would typically be appropriate, or an 18-year-old, for whom it would typically be inappropriate. This better positions us to compare the effects of monitoring behaviors across families and over time. Finally, we avoid circular reasoning in which monitoring is ipso facto defined to be beneficial in all instances, because the construct definition excludes any ineffective or inappropriate behaviors. This better positions us to identify persons and settings for whom monitoring may have mixed or adverse effects (Laird et al., 2010, 2018).

4.4. Parental monitoring across development, families, and settings

Our definition of monitoring is intended to apply to all stages of development, families, and settings: monitoring behaviors are always those performed by caregivers with the goal of acquiring information about the youth’s activities and life. However, which monitoring behaviors are feasible, appropriate, and adaptive changes substantially across developmental and sociocultural contexts, so these contextual factors must be carefully considered when moving from construct definition to measurement, data analysis, and data interpretation (Millsap, 2011; Petersen et al., 2020). For example, constant direct observation is appropriate monitoring during infancy but not during young adulthood. Likewise, strict rules about a teenager leaving the home unsupervised might be appropriate for a family living in a disadvantaged, dangerous neighborhood but less appropriate for a family living elsewhere (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). Many studies have shown that the nature or efficacy of parental monitoring can vary by child, family, and environmental characteristics such as age (e.g., Drozdova et al., 2023), racial or ethnic identity (e.g., Bumpus & Rodgers, 2009), socioeconomic status (e.g., Rekker et al., 2017), neighborhood safety (e.g., Skinner et al., 2014), family structure (e.g., Padilla-Walker et al., 2011), or parent-child relationship quality (e.g., Keijsers et al., 2009). In our formulation, these child, family, and environmental characteristics should inform our evaluations of monitoring behaviors, as explained in Section 4.6.3.

4.5. Parental monitoring in relation to other parenting constructs

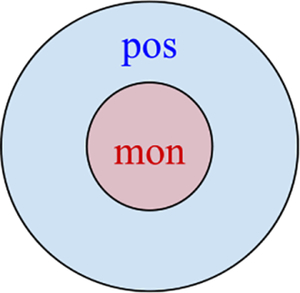

As seen in Section 2, a point of continued confusion in the literature has been the conceptual overlap between monitoring and other constructs. As such, Table 5 explains how parental monitoring as we define it relates to 16 other parenting constructs– sometimes overlapping with, sometimes encompassing, and sometimes being encompassed by the other construct. In the text, we focus on the relation that has provoked the most controversy in the literature: that between parental monitoring and parental knowledge: the information that parents have about youths’ activities, whereabouts, and companions (Stattin et al., 2010).

Table 5.

How Parental Monitoring Relates to Other Commonly Studied Parenting Constructs

| Construct | Relation to the monitoring construct |

|---|---|

|

Parenting style: The parent’s constellation of attitudes toward the youth that create a global emotional climate for the parent-youth relationship (e.g., authoritative, permissive) (Darling & Steinberg, 1993) |

“Parenting style” could be a cause of or context for parental monitoring behaviors. Parenting style should not be confused with the “style” dimension of monitoring behaviors in our taxonomy, which refers to the manner in which a given monitoring behavior is performed. |

|

Parental strictness: The parent’s general tendency toward surveillance, demandingness, and supervision of the youth (Garcia et al., 2020) |

“Parental strictness” could be a cause of monitoring behaviors. In our taxonomy, parental strictness would be reflected in the style dimension: monitoring behaviors can be performed in more or less strict fashion. |

|

Parental warmth: The parent’s general tendency to show the youth acceptance and affection and to be responsive (Garcia et al., 2020) |

“Parental warmth” could be a cause of monitoring behaviors. In our taxonomy, parental warmth would be reflected in the style dimension: monitoring behaviors can be performed in a warmer or colder fashion. (Olson et al., 2023) |

|

Parent-child relationship quality: “The degree of closeness, understanding, trust, shared decision making, and caring that exists in the parent-child relationship” (Olson et al., 2023) |

“Parent-child relationship quality” could be a context for parental monitoring behaviors. In our taxonomy, parent-child relationship quality could be reflected in the style dimension: the kind of relationship a parent has with their youth may affect the fashion in which they monitor. |

|

Parental knowledge: Information the parent has about the child’s general activities, whereabouts, and company (Stattin & Kerr, 2000) |

“Parental knowledge” is not a set of behaviors, it is information a parent knows about their youth. |

|

Spending time with youth: Time when the parent is in the youth’s physical presence. |

Spending time with youth enables Type 4 monitoring behaviors, if the parent is actively observing the youth. However, parents can spend time with youth without directly observing them, which would not comprise monitoring. |

|

Helicopter parenting: Parenting behaviors that are high in control, high in warmth/support, and low on granting youth autonomy (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012) |

Some “helicopter parenting” behaviors are monitoring behaviors if they are performed to gather information (e.g. asking friends for information about youth’s whereabouts). However, other helicopter parenting behaviors are not monitoring behaviors (e.g., sending the youth jobs they should apply to). |

|

Parent-youth communication: The exchange of information between the parent and the youth. |

Parent communication to the youth can sometimes be a parental monitoring behavior. Youth communication to the parent can never be a parental monitoring behavior because parental monitoring behaviors are only performed by parents. Parent-youth communication that consists of the parent asking the youth about their life and activities is a Type 1 monitoring behavior (Section 4.6.1). Parent-youth communication that consists of the parent communicating a rule designed to gather information is a Type 2 monitoring behavior. When the parent is not communicating with the goal of gathering information about the youth’s activities or life, then that parent-youth communication is not a monitoring behavior. |

|

Parental discipline: The parent delivering a negative consequence when the youth breaks a rule. |

Most “parental discipline” is not parental monitoring because the behaviors are not performed with the goal of gathering information about the youth’s life and activities. However, parental discipline to enforce a rule designed to gather information (e.g., grounding the teen for breaking curfew) would be a Type 2 monitoring behavior. |

|

Parental involvement: Involvement in the child’s life through shared activities (Essau et al., 2006) |

Some forms of “parental involvement” are Type 1 parental monitoring behaviors (e.g., asking the youth about events of their day), but others are not (e.g., planning family activities). |

|

Parental rules: A behavioral criterion for the youth that has been communicated by a caregiver to the youth. |

Setting and enforcing rules is a Type 2 monitoring behavior if the rule is intended to gather information (e.g., a rule that youth must always be reachable by phone when out of the house). Setting and enforcing rules that are not intended to gather information (e.g., a rule against drinking alcohol) do not count as monitoring behaviors. |

|

Parental control: Parents setting of rules about whether youth must seek permission or inform parents about plans and activities when leaving the house (Kerr & Stattin, 2000) |

“Parental control” is encompassed by Type 2 parental monitoring behaviors. Type 2 parental monitoring behaviors are broader than parental control because they include any behavior to set or enforce rules to gather information, rather than only about coming and going as they please. |

|

Parental solicitation: The parent asking youth and others in their life about the youth’s activities, whereabouts, and companions (Kerr & Stattin, 2000) |

“Parental solicitation” is encompassed by Type 1 parental monitoring behaviors. Type 1 parental monitoring behaviors are broader than parental solicitation; they include asking any person for information, rather than just youth, youths’ friends, and youths’ friends’ parents (e.g., teachers, neighbors). |

|

Parental snooping: The parent going through the youth’s belongings (e.g., phone, computer, diary, backpack) or space (e.g., bedroom) without the youth’s permission or knowledge (Hawk et al., 2016) |

“Parental snooping” is encompassed by Type 3 parental monitoring behavior. Type 3 parental monitoring behaviors are broader because they include the parent going through the youth’s belongings with permission or with the youth’s knowledge. In our taxonomy, the style dimension would capture differences between other Type 3 monitoring behaviors and parental snooping. |

|

Parental supervision: The parent’s observation of the youth when co-located with the youth (Coley & Hoffman, 1996) |

“Parental supervision” and Type 4 parental monitoring behaviors are identical. |

|

Positive parenting: Parenting practices that include having warm affect, nurturing a trusting relationship with the youth, nonaversive interactions, attentive involvement and guidance, positive reinforcement, and proactively promoting development. (Dishion et al., 2008) |

“Positive parenting” is a broader construct that parental monitoring is entirely encompassed by. |

Note. Each row in the table describes the differences and overlap between the parental monitoring construct as we define it (Section 4.1) and a related construct from the broader parenting literature. Definitions of the other constructs are often inconsistent and unclear in the literature, so the first column states the definition we used for each construct when making the comparison to monitoring. In the second column, the Venn diagram shows how each other construct relates to parental monitoring. The depiction is qualitative - the amount of spatial overlap has no quantitative meaning. A Venn diagram is omitted when the nature of the other parenting construct prohibits a meaningful visual depiction of its relation to monitoring. The second column sometimes references aspects of the taxonomy we develop in Section 4 (e.g., Types 1–5 monitoring behaviors, the dimensions of monitoring behaviors)—see Sections 4.6.1 and 4.6.2 for an explanation.

Concurring with prior authors (Crouter & Head, 2002; Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Racz & McMahon, 2011; Stattin et al., 2010), we exclude parental knowledge from the definition of parental monitoring for four reasons. First, the label of a construct should match its contents, and to “monitor” does not mean to possess knowledge of something. Mismatch between the construct and its label muddles thinking and communication among scientists. Second, knowledge and monitoring are theoretically dissociable: it is straightforward to distinguish knowledge, a mental object in the parent’s mind, from monitoring, a behavior that a parent performs in the physical world. Third, knowledge and monitoring are empirically dissociable: research to date has found they are only moderately correlated (e.g., r = 0.30−0.50; Eaton et al., 2009; Hamza & Willoughby, 2011). Finally, even if parental knowledge is the hoped-for outcome of monitoring, that is not a compelling argument for measuring knowledge and then labeling it monitoring. This makes about as much sense as measuring a person’s heart health then labeling it “exercise.” Just as there are many determinants of heart health besides exercise, there are many determinants of knowledge besides monitoring.

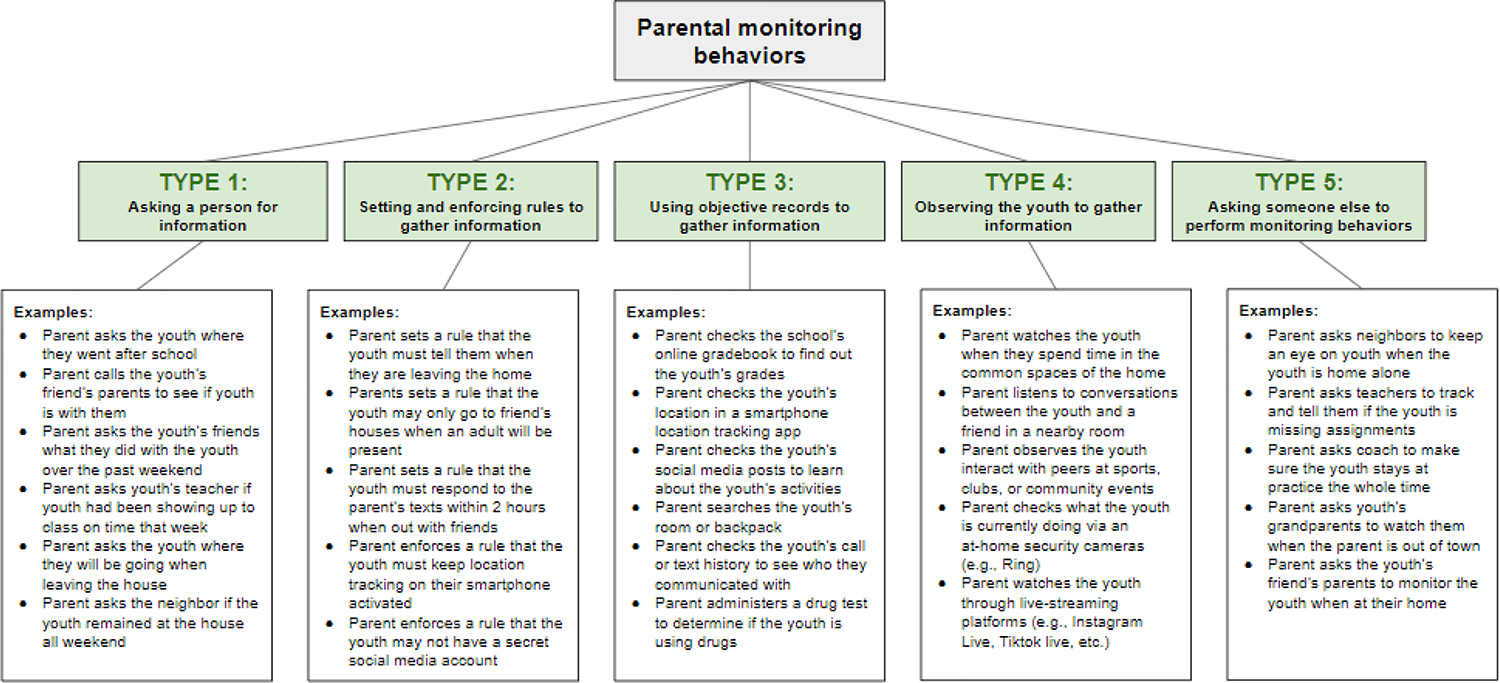

4.6. A taxonomy of monitoring behaviors

Having defined parental monitoring as a set of parent behaviors (Section 4.1), we now develop a taxonomy to organize such behaviors. The taxonomy is outlined in Table 4 and shown in Figure 2. There are five types of monitoring behaviors, each of which vary along five dimensions.

Table 4.

Aspects of Taxonomy of Parental Monitoring Behaviors

| Aspect of taxonomy | Purpose of aspect | Description of aspect |

|---|---|---|

| Types | To categorize monitoring behaviors based on their essential form: the method by which they aim to acquire information |

|

| Dimensions | To describe ways in which a given monitoring behavior may vary |

|

| Evaluations | To capture evaluations (i.e., judgments, appraisals) of a given monitoring behavior |

|

| Further distinctions | To make further distinctions among monitoring behaviors that could be theoretically relevant |

|

Note. Table gives an overview of the taxonomy described in Section 4.6.

Figure 2. Examples of the Five Types of Monitoring Behaviors.

Note. Figure illustrates the taxonomy of parental monitoring behaviors described in Section 4.6 and summarized in Table 4.

4.6.1. Types.

“Types” of monitoring behaviors differ in the form of the parent behavior performed to gather information. There are five types: Figure 2 gives examples of each. In Type 1 monitoring behaviors, parents ask a person for information. For example, the parent could ask the youth, a sibling, a teacher, a neighbor, another parent, or the youth’s peers for information about the youth’s future or past plans, activities, whereabouts, and behaviors.

In Type 2 monitoring behaviors, parents set and enforce rules to gather information. For example, the parent might require that the youth give them the phone number of the youth’s friend’s parent before spending time at the friend’s house (setting a rule) and then might ground the youth for violating this rule (enforcing a rule). The rule being set and enforced must be for the purpose of gathering information; setting and enforcing a rule against drinking alcohol, for example, would not count as a Type 2 monitoring behavior. “Enforcing” a rule refers to providing an appropriate consequence: reinforcement when the youth follows the rule and punishment when the youth violates the rule.

In Type 3 monitoring behaviors, parents use objective records to gather information. For example, the parent might drug test their youth at home to have physical records of substance use and keep track of their sobriety. The records could be physical (e.g., inspecting homework worksheets) or electronic (e.g., inspecting text message history).

In Type 4 monitoring behaviors, parents observe the youth to gather information. For example, the parent might check on what the youth is doing in their bedroom, listen to what the youth talks about with their friends when they are visiting, or drive to where the youth said they would be after school to see if they are there.

In Type 5 monitoring behaviors, parents ask someone else to perform a monitoring behavior (e.g., another family member, a teacher, a neighbor). For example, the parent could recruit a neighbor to go over to the family’s home after school and check what the youth is doing.

4.6.2. Dimensions.

Each instance of monitoring behavior can vary along five dimensions: performer, target, frequency, context, and style. The performer and target dimensions are discrete while the frequency, context, and style dimensions are continuous. Next, we explain each dimension using the example monitoring behavior of asking youth for information about their day.

“Performer” refers to who performed the monitoring behavior. For example, mothers, fathers, or other caregivers could ask the youth for information about their day. Or, multiple caregivers could coordinate to jointly perform a monitoring behavior.

“Target” refers to what domain of information the monitoring behavior is intended to gather. For example, when asking the youth for information about their day, the parent could ask about where the youth had been (target: location), who the youth had been with (target: peers), or whether the youth had received a test back at school (target: academics). Possible target domains of monitoring include the youth’s location, companions and friendships, activities during unsupervised time (after school, evenings, etc.), school and academics (e.g., attendance, homework, grades), employment (e.g., attendance, performance), internet use and media consumption, dating and romantic relationship, money (e.g., amount, spending habits), health (e.g., diet, exercise, medication), personal space and belongings (e.g., bedroom), problem behaviors (e.g., alcohol use), and mood (e.g., depression, anxiety).

“Frequency” refers to how often parents perform monitoring behaviors over time. For example, a parent could ask the youth for information about their day multiple times a day, 7 times per week, 1 time per week, or less.

“Context” complements the frequency dimension by capturing when, where, and why a parent performs monitoring behaviors. For example, the parent could ask the youth for information about their day during the car ride home from school, while doing an enjoyable shared activity, or immediately after an argument about the youth’s grades at school.

“Style” refers to whether the monitoring behavior is performed in a warm, supportive, respectful style or a hostile, critical, controlling style.4 For example, when asking the youth for information about their day, the parent could say “What did you do after school, anything fun?” (warm) or “What did you do after school–you better not have wasted time playing video games again!” (critical).

4.6.3. Evaluations.

As explained in Section 4.3, we separate the monitoring behavior itself–defined by types and dimensions–from evaluations of that behavior (i.e., appraisals, judgments). Table 4 lists possible evaluations of monitoring behaviors. For example, one possible evaluation is the developmental appropriateness of a monitoring behavior. Supervising the youth while they take a bath is a monitoring behavior whether it is performed with a 3-year-old or a 17-year old. However, it is a developmentally appropriate monitoring behavior only for the former.

Another evaluation is situational appropriateness: is the parental monitoring behavior reasonable given the recent behavior of the youth and the context in which it is performed? For example, going through the youth’s phone messages to see who they had been with would be contextually inappropriate without any reason to be concerned, yet the same behavior would be contextually appropriate if the youth arrived home one night appearing dangerously ill and intoxicated from an unknown ingestion.

Another possible evaluation is invasiveness: is the behavior invasive or intrusive of the youth’s privacy? Invasive monitoring behaviors may provoke negative reactions from youth, including becoming more secretive and less willing to share information with parents (Hawk et al., 2008). Some monitoring behaviors are inherently more invasive, such as going through a youth’s phone, whereas others might be invasive only in some circumstances or to some youth. For example, asking detailed questions about what the teen did on a night out might be received well if the night out was with friends but as invasive if the night out was a date with a romantic interest.

Other possible evaluations include accuracy and difficulty: How likely is the monitoring behavior to yield accurate information and how difficult and effortful is the monitoring behavior to perform? For example, asking the youth where they were after school might be expected to yield less accurate information than would checking the history in an application that tracks the youth’s smartphone’s location (Davis et al., 2023). Likewise, asking the youth about their grades at school might require less effort from parents than gaining access to the school’s electronic gradebook to check their grade point average independently.

4.7. Further possible distinctions among monitoring behaviors

Beyond types, dimensions, and evaluations of monitoring behaviors, we also introduce four further distinctions among monitoring behaviors that could be of theoretical relevance. These distinctions can be applied to all five types of monitoring behaviors.

4.7.1. Overt vs. covert monitoring behaviors (Hawk, 2017).

A monitoring behavior is overt when the youth is aware it is being performed; a monitoring behavior is covert when the youth is not aware it is being performed. For example, the parent asking the youth where they currently are would be an overt monitoring behavior, whereas checking the youth’s location using an app surreptitiously installed on the youth’s smartphone would be a covert monitoring behavior.

4.7.2. Proactive vs. reactive monitoring behaviors.

Proactive monitoring behaviors are performed according to a preplanned schedule, whereas reactive monitoring behaviors are triggered or provoked by a stimulus. For example, a parent could ask the youth about what they did at school that day every night at dinner (proactive) or only on days when the youth seems especially moody (reactive).

4.7.3. Retrospective vs. concurrent vs. prospective parental monitoring behaviors.

Parental monitoring behaviors may seek to acquire information about what has already happened (retrospective), what is currently happening (concurrent), or what will happen in the future (prospective).

4.7.4. Transitory vs. structural monitoring behaviors.

Transitory monitoring behaviors are performed to acquire information in the short-term that will expire in relevance, while structural monitoring behaviors are performed to establish or strengthen the parent’s ability to acquire information in the future. For example, asking the youth where they are going when they leave the house is a transitory monitoring behavior because the youth’s answer will be useful information only for a few hours. In contrast, signing up for the youth’s school electronic gradebook at the start of the school year is a structural monitoring behavior because the goal is to be able to regularly and easily acquire information throughout the school year - not to find out the youth’s grade on a specific test right now.

4.8. How the new formulation helps

We now step back to show how our new formulation of the monitoring construct enables progress on the major questions in the literature that were discussed in Section 3. First, is parental knowledge part of the monitoring construct? We answered that parental monitoring is completely distinct from parental knowledge, instead conceptualizing knowledge as a hoped-for outcome of monitoring behaviors.

Second, is monitoring a parent behavior or a dyadic interaction between parents and youth? We answered that parental monitoring is a behavior performed exclusively by parents and justified the value of that conceptualization.

Third, is parental monitoring a cause of youth adjustment or merely a correlate? Our formulation enables progress on this question by conceptually separating parental monitoring behaviors from their effects (Section 4.3) and drawing crisp distinctions between monitoring and many constructs in nearby nomological space (Section 4.5). Indeed, monitoring cannot be rigorously evaluated as a possible cause of youth behavior unless it can be conceptually distinguished from youth behavior and from other correlated parenting behaviors.

Fourth, is more monitoring always better? Our formulation enables progress on this question in several ways. We define monitoring in a non-evaluative fashion, allowing that monitoring behaviors can be maladaptive or inappropriate (Section 4.3). We introduce the notion of “evaluations” of monitoring behaviors to capture the idea that monitoring could increase in frequency yet still be evaluated as less effective. We characterize monitoring as varying not just in frequency but in the context and style of performance, recognizing that monitoring could be intense (i.e., high frequency) yet deployed in a fashion that renders it detrimental. Finally, by defining parental monitoring as a set of behaviors rather than a unitary construct, we allow that specific monitoring behaviors could be adaptive even while others are not.

Fifth, how much does monitoring vary across families? Our formulation enables progress on this question by clarifying several ways in which monitoring could differ between families–in the selection of behaviors, in which caregivers perform them, or in the frequency, context, or style of performance. Similar scores on a monitoring rating scale could reflect very different underlying patterns of monitoring. Adaptive monitoring for one family may comprise a very different pattern across these dimensions than does adaptive monitoring for another family.

Sixth, how does monitoring unfold over time? Our formulation enables progress on this question by defining monitoring as observable behaviors that occur at a specific moment in time (i.e., the moment they are performed). Monitoring behaviors can be measured repeatedly to study their stability over time and establish clear temporal ordering when studying the causes and effects of monitoring. For example, we can study how a monitoring behavior performed on a given Tuesday affected youth behavior later that day, and itself was driven by youth behavior the previous day. In contrast, if monitoring is formulated as an attribute of a family or a relationship property, it is not obvious how to determine “when” that monitoring occurred.

5. What next?

This paper asked a simple but important question: What is parental monitoring? We reviewed previously published theoretical definitions and operationalizations and found little clarity or agreement, impeding scientific progress on several fronts. We then proposed a new formulation of parental monitoring that we believe can remedy the situation. In this section, we leverage the new formulation to identify several important areas meriting the field’s attention.

5.1. Gaps in the empirical evidence

Our formulation of parental monitoring suggests that the empirical literature on parental monitoring is far more limited than appears at first glance, for two reasons. The first reason is that only 2 of the 20 instruments listed in Table 2 are pure, direct measures of parental monitoring (S&K, PMI). Thus, the vast majority of the thousands of published articles ostensibly about monitoring (Figure 1) have instead analyzed scores on a mixture of monitoring and other constructs (e.g., discipline, communication) or scores on another construct entirely (e.g., knowledge). Today, it is unknown which findings obtained in the literature would be replicated using a pure measure of monitoring.

The second reason is that the only pure measures of monitoring in widespread use-Stattin and Kerr’s solicitation and control scales (S&K)-do not capture the full breadth of the monitoring construct. These scales measure Type 1 and Type 2 monitoring behaviors, respectively, and do not measure Types 3, 4, or 5 behaviors. They measure the frequency of monitoring behaviors in a limited set of domains, but not the context or style of performance. Thus, almost all empirical findings about “monitoring” today can be more precisely understood as about the frequency of Type 1 and 2 monitoring behaviors. Major, sustained efforts will be required to build an empirical literature of the monitoring construct as defined herein.

5.2. Gaps in measurement tools

Building a rigorous and comprehensive evidence base will first require much more attention to the measurement of monitoring. First, the field would benefit from more rigorous psychometric evaluation of existing scales. A systematic review found that monitoring scales have received little evaluation of factor structure or content validity (Handschuh et al., 2020). As described in Section 5.1, it seems likely that existing scales are missing both important types and dimensions of monitoring behaviors.

We also lack evidence that youth or parent reports of the frequency of monitoring behaviors on a rating scale actually correspond to the true frequency of those behaviors. Responses on rating scales have not been validated against direct observation of monitoring behaviors in naturalistic settings or objective records, such as phone logs. Concerningly, parent and youth reports of the frequency of the parent’s monitoring behaviors are only modestly correlated (e.g., r= 0.08–0.29 in Abar et al., 2015; Keijsers et al., 2010; Kerr et al., 2010).

Another priority is to understand the extent to which scales contaminated with other concepts (Table 2) can still be safely regarded as measures of monitoring. These scales may be so contaminated that we should simply exclude the resulting empirical findings from discussion of monitoring, or only mildly contaminated, yielding findings we can carefully integrate into the monitoring literature. A validated ontology of existing monitoring scales could clarify the situation and identify appropriate bridges between empirical work with differing perspectives (Eisenberg et al., 2019).

Second, the field would likely benefit from the development of new theory-driven measures. Major pieces of our taxonomy (Table 4) are not captured in any existing measures of monitoring. Types 3, 4, and 5 monitoring behaviors are absent from the only pure monitoring measure in widespread use (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). There is no measure of the style in which monitoring behaviors are performed. There is no measure that distinguishes proactive vs. reactive monitoring behaviors or assess the degree to which monitoring behaviors are being appropriately titrated to the context and level of risk. It seems likely that investigators will need a suite of measures, as the full breadth and detail of the monitoring construct would be difficult to capture in a single survey instrument.

Third, the field would benefit from greater consideration of multimethod and multi-informant measurement. Although early research on monitoring was multimethod (Patterson et al., 1984), the field has since relied almost entirely on survey-based measurement. Indeed, there is no existing non-survey-based measure of monitoring as we define the construct herein. Fully characterizing the type, frequency, context, and style of monitoring may require the creation of new interview-based or observational measurement schemes.

Likewise, despite evidence that discrepancies among different raters of monitoring are important (De Los Reyes et al., 2010), the field has not achieved a consensus on which informants to ask about monitoring or articulated a framework for combining reports or interpreting discrepancies (De Los Reyes et al., 2013). Our conceptualization of monitoring suggests the answer may not be simple. Different informants may have better or worse perspectives on only certain dimensions of monitoring behavior.

Fourth, the field would benefit from careful attention to developmental and sociocultural issues when evaluating existing measures of monitoring or developing new ones. Which monitoring behaviors are adaptive differs across ages, families, and contexts, and this fact must be carefully considered before evaluating longitudinal change or comparing across groups (Millsap, 2011; Petersen et al., 2020). The few published evaluations of measurement invariance on monitoring scales have found differences by age (Arim, 2009) and gender (Tilton-Weaver, 2014), and far more comprehensive testing is needed.

Finally, the field would benefit from greater attention to time scale when creating measures and designing protocols. If parental monitoring is to be studied as a cause or outcome of youth behavior, then we need procedures that can clearly establish the timing of monitoring behaviors within a sequence of parent and youth interactions over time. That is not possible with existing scales because the vast majority do not specify the timeframe being asked about. In addition, no existing scale uses item wording or response options that are suitable for measuring momentary or recent monitoring, such as in an ecological momentary assessment or daily diary paradigm. Having scales that can measure monitoring as a discrete behavior, rather than as a frequency over several months, would help us probe short-term and proximal effects (Pelham III et al., 2023).

5.3. Gaps in clinical applications

Our formulation of parental monitoring also reveals major gaps in clinical applications of the construct. Many prevention and intervention programs focus on improving parental monitoring as a way to reduce youth problem behavior. However, these programs focus on some dimensions of the monitoring construct at the neglect of others. Existing programs tend to have two goals: increase the frequency of monitoring or increase the targets of monitoring to include more domains (Hawes and Baker, 2023; Schwarz-Torres et al., 2023). In contrast, the context and style of monitoring receive limited attention in case conceptualization or clinical recommendations.