Abstract

Purpose

Although immune-checkpoint inhibitors have become a new therapeutic option for recurrent/metastatic non-small cell lung cancers (R/M-NSCLC), its clinical benefit in the real-world is still unclear.

Methods

We investigated 1181 Korean patients with programmed death-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1)-positive [tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥ 10% by the SP263 assay or ≥ 50% by the 22C3 assay] R/M-NSCLC treated with pembrolizumab or nivolumab after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy.

Results

The median age was 67 years, 13% of patients had ECOG-PS ≥ 2, and 27% were never-smokers. Adenocarcinoma was predominant (61%) and 18.1% harbored an EGFR activating mutation or ALK rearrangement. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab were administered to 51.3% and 48.7, respectively, and 42% received them beyond the third-line chemotherapy. Objective response rate (ORR) was 28.6%. Pembrolizumab group showed numerically higher ORR (30.7%) than the nivolumab group (26.4%), but it was comparable with that of the nivolumab group having PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% (32.4%). Median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 2.9 (95% CI 0–27.9) and 10.7 months (95% CI 0–28.2), respectively. In multivariable analysis, concordance of TPS ≥ 50% in both PD-L1 assays and the development of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) were two significant predictors of better ORR, PFS, and OS. EGFR mutation could also predict significantly worse OS outcomes.

Conclusion

The real-world benefit of later-line anti-PD1 antibodies was comparable to clinical trials in patients with R/M-NSCLC, although patients generally were more heavily pretreated and had poorer ECOG-PS. Concordantly high PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% and development of irAE could independently predict better treatment outcomes, while EGFR mutation negatively affected OS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-021-03527-4.

Keywords: Immune-checkpoint inhibitor, Non-small cell lung cancer, Real-world, Biomarkers, PD-L1, irAE

Introduction

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have promised a new era for patients with recurrent and/or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (R/M-NSCLC), initially based on the landmark trials which demonstrated a clear therapeutic benefit of 2nd-line treatment with ICIs compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy. The benefit was obvious in terms of overall survival (OS), with most trials reporting a median OS of 10–16 months (Borghaei et al. 2015; Brahmer et al. 2015; Herbst et al. 2016; Rittmeyer et al. 2017). Moreover, two landmark trials, Keynote-010 and -024, consistently addressed a greater survival benefit in patients with high programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression [tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥ 50%], which could be further enhanced when shifting to front-line treatment (Gandhi et al. 2018; Reck et al. 2016). Although the magnitude of benefit seemed relatively modest in terms of objective response rate (ORR), ranging from 15 to 20%, the ORR was also significantly enriched (up to 30%) for PD-L1-positive patients.

However, there still remains a critical gap between the data from clinical trials and our daily practice, as clinical trials enroll patients according to the stricter eligibility (Eisenhauer et al. 2009; Gandhi et al. 2018). Accordingly, in a previous study, only 30% of R/M-NSCLC patients in the real-world were eligible on the basis of eligibility criteria of landmark phase III trials of later-line ICIs (Yoo et al. 2018). In this context, there is an increasing concern that therapeutic benefits proved in clinical trials could not be fully translated into our real-world practice. Although several recent studies suggested comparable efficacy of ICIs in R/M-NSCLC in the real-world setting, this gap of eligibility would be more prominent in under-investigated population of clinical trials, such as those with molecular aberrations, underlying comorbidities, poor performance, or Asian ethnicity (Ahn et al. 2019; Smit et al. 2020; Tournoy et al. 2018).

Therefore, in the study, we evaluated the real-world efficacy and safety of later-line ICIs in a large multi-center dataset of Korean patients having PD-L1-positive R/M-NSCLC, to assess whether a meaningful therapeutic benefit exists in real-life practice. Furthermore, we investigated potential predictors of efficacy outcomes among clinicopathologic parameters, mainly focusing on PD-L1 TPS, to contribute to a more practical biomarker-driven strategy of ICIs.

Materials and methods

Study population

We retrospectively reviewed R/M-NSCLC patients who received later-line anti-PD-1 inhibitors after the failure of platinum-based chemotherapy between August 2017 and June 2018. Data were collected from the 20 top-ranked medical centers in terms of the number of prescribed ICIs. Additional inclusion criteria are described in Supplementary Data 1. As mandated by the national reimbursement regulation (Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service 2019), the types of anti-PD-1 inhibitors were determined by available PD-L1 TPS: either pembrolizumab or nivolumab could be administered when TPS ≥ 50% using the 22C3 assay (pembrolizumab group) or ≥ 10% using the SP263 assay (nivolumab group). According to the licensed dose and administration method, pembrolizumab was given at a fixed dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks and nivolumab was given at a fixed dose of 3.0 mg/kg every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. To ensure the quality and consistency of data, we delegated data collection and management to the site management organization (Supplementary Data2).

Definition of PD-L1 expression

PD-L1 expression was assessed immunohistochemically in formalin-fixed, pretreatment tumor samples using the PD-L1 22C3 pharmDx antibody (Dako North America Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA) or the Ventana PD-L1 SP263 antibody (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) (Borghaei et al. 2015; Roach et al. 2016). It was based on the definition of the TPS, determined as the percentage of stained membranes of tumor cells in each section that included at least 100 evaluable tumor cells. TPS was estimated in increments of 5%, except for a 1% value, and patients with at least 1% of the stained tumor cells were considered positive in both PD-L1 assays.

Assessment of treatment outcomes

Efficacy outcomes included objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Tumor response was assessed by computed tomography scans, but the decisions concerning the follow-up intervals or radiologic tools were entirely at the discretion of the physician. Responses to anti-PD-1 antibodies were defined according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v.1.1) (Supplementary Data 3) (Eisenhauer et al. 2009). PFS was defined as the time interval between the initiation of treatment with ICIs and the date of first objective detection of PD. OS was defined as the time interval between the treatment initiation and the date of death from any cause. All patients who received at least one dose of pembrolizumab or nivolumab were evaluated for adverse events, particularly focusing on immune-related adverse events (irAEs) before each subsequent treatment cycle, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) v.5.0 (National Institutes of Health 2017).

Statistical analyses

Independent t tests for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables were used as appropriate for comparison of patient characteristics and study outcomes between the pembrolizumab and nivolumab groups. In exploratory biomarker analysis, univariable and multivariable logistic regressions were used to identify the predictors of ORR. Cox proportional hazard regression was performed to identify the associated predictors of OS and PFS. The Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test was used to estimate the survival outcomes. All p values were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients and treatment

Baseline characteristics of the 1,181 patients are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1, and there was no significant difference between the pembrolizumab and nivolumab groups (data not shown). The median age was 67 years (range 22–95 years). Current or former smokers constituted 73.5% of the patients. Although most of patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) 0 or 1, 12% presented with ECOG-PS ≥ 2. Adenocarcinoma was predominant (61%), but 35% of patients displayed squamous histology. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement were observed in 14.8% and 4.3% of the evaluable patients, respectively. Twelve percent of the patients experienced metastases to brain parenchyma or leptomeninges.

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic characteristics of the total of 1181 patients at the time of treatment with ICIs

| Demographic | Total (n = 1181, 100%) | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Missing rate | |

| Gender | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Male | 932 (78.9) | |

| Female | 249 (21.1) | |

| Age, median (range) | 67 (22, 95) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Smoking history | (0.00) | |

| Never-smoker | 305 (26.5) | |

| Ex-smoker | 371 (32.3) | |

| Current smoker | 474 (41.2) | 31 (2.62%) |

| Histologic subtype | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 396 (34.6) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 701 (61.2) | |

| Other | 48 (4.2) | 36 (3.05%) |

| ECOG-PS | 48 (4.06%) | |

| 0 | 35 (3.1) | |

| 1 | 958 (84.5) | |

| ≥ 2 | 141 (12.4) | |

| Stage | 1 (0.08%) | |

| Stage III | 28 (5.3) | |

| Stage IV | 1117 (94.7) | |

| Prior radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 554 (46.9) | |

| Curative aim | 217 (39.2) | |

| Palliative aim | 337 (60.8) | |

| Locoregional irradiation | 274 (49.5) | |

| Distant site irradiation | 280 (50.5) | |

| No | ||

| Disease setting | 2 (0.17%) | |

| Initially metastatic | 758 (64.3) | |

| Relapsed or progressed metastatic | ||

| After curative surgery | 144 (12.2) | |

| After definitive CRT for Stage IIIA/IIIB | 141 (12.0) | |

| After CTx alone for Stage IIIA/IIIB | 136 (11.5) | |

| Metastatic sites | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Regional lymph nodes | 25 (1.1) | |

| Lung | 410 (18.3) | |

| Pleural | 272 (12.1) | |

| Distant lymph nodes | 518 (23.1) | |

| Adrenal | 117 (5.2) | |

| Bone | 364 (16.3) | |

| Liver | 139 (6.2) | |

| Brain | 259 (11.5) | |

| Leptomeninges | 2 (0.1) | |

| Line of Therapy (ICIs treatment) | (6.0) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 1st line | 17 (1.4) | |

| 2nd line | 680 (57.6) | |

| ≥ 3rd Line | 484 (41.0) | |

| Biomarker assessment | 0 (0.00%) | |

| PD-L1 | 1181 (100.0) | |

| EGFR mutation | 928 (78.6) | |

| ALK rearrangement | 844 (71.5) | |

| ROS-1 | 22 (1.9) | |

| K-RAS | 26 (2.2) | |

| B-RAF | 2 (0.2) | |

| RET | 1 (0.1) | |

| PD-L1 (SP263 assay) | 391 (33.11%) | |

| Median (range) | 40 (0, 100) | |

| PD-L1 (22C3 assay) | 370 (31.33%) | |

| Median (range) | 70 (0, 100) | |

| PD-L1 ≥ TPS 50 in either assay | ||

| Yes | 863 (73.1) | |

| No | 318 (26.9) | |

| PD-L1 ≥ TPS 50 in both assays | ||

| Yes | 182 (15.4) | |

| No | 243 (20.5) | |

| EGFR mutation | 253 (21.42%) | |

| Positive | 137 (11.6) | |

| Negative | 791 (67.0) | |

| ALK rearrangement | 337 (28.54%) | |

| Positive | 36 (3.1) | |

| Negative | 808 (68.4) | |

CRT chemoradiation therapy, CTx chemotherapy

PD-L1 TPS was assessed in all patients, with 790 assessed using the SP263 assay and 811 assessed using the 22C3 assay. Median values of TPS were 40 (range 0–100) for the SP263 assay and 70 (range 0–100) for the 22C3 assay, and about 15% of patients (n = 182) simultaneously demonstrated TPS ≥ 50%. Of all, pembrolizumab and nivolumab were administered to 606 (51.3%) and 575 (48.7%) patients, respectively, and 42% of patients received the drug beyond their third-line chemotherapies. The majority of patients (n = 927, 78.5%) discontinued the treatment primarily because of disease progression (76.5%) or toxicity (10.6%), while 21% of patients maintained ICIs without treatment interruption until the end of the study. Forty-two (3.6%) patients harbored underlying autoimmune diseases at the time of initiation of treatment with ICIs. The most frequent diseases were hypothyroidism (n = 23, 54.8%) and rheumatic arthritis (n = 9, 21.4%). Concurrent malignancies, which were mostly curatively resected or well-stabilized, were also found in 76 cases (6.4%) (Supplementary Table 1).

Real-world outcomes of ICIs

Efficacy

The ORR in the 1181 patients was 28.6% (n = 338); complete response (CR): 0.7% (n = 9), partial response (PR): 27.9% (n = 329), and disease-control rate was 55.3% (n = 653), respectively. For responders, the median time-to-response was 2.3 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.1, 2.5] with a median duration of response (DOR) of 13 months (95% CI 11.9, not reached) (Table 2). Although statistically insignificant (p = 0.106), the ORR of the pembrolizumab group (30.7%) tended to be higher than that of the nivolumab group (26.4%) (Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, in the nivolumab group, the ORR of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% was significantly higher than those with TPS < 50% by the SP263 assay (32.4% vs 21.3%, p = 0.003), which was numerically comparable to that of pembrolizumab group (32.4% vs 30.7%) (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of treatment responses in the 1181 total patients and 1026 evaluable patients

| Efficacy outcomes | Total (n = 1181, 100%) Evaluable (n = 1026, 100%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) or [median] | 95% CI | |

| ORR | 338 (28.6) [32.9] | (26.0, 31.2) |

| DCR | 653 (55.3) [63.7] | (52.5, 58.1) |

| TTR (months) | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.5) |

| DOR (months) | 13.1 | (11.9, –) |

| Best response | Event, n | % (Total n = 1181) | % (Total n = 1023) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR (Complete response) | 9 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| PR (Partial response) | 329 | 27.9 | 32.2 |

| SD (Stable disease) | 315 | 26.7 | 30.8 |

| PD (Progressive disease) | 373 | 31.6 | 36.5 |

| N/A or N/E | 155 | 13.1 |

ORR Objective response rate, DCR disease-control rate, TTR time-to-response, DOR duration of response, N/A not available, N/E non-evaluable

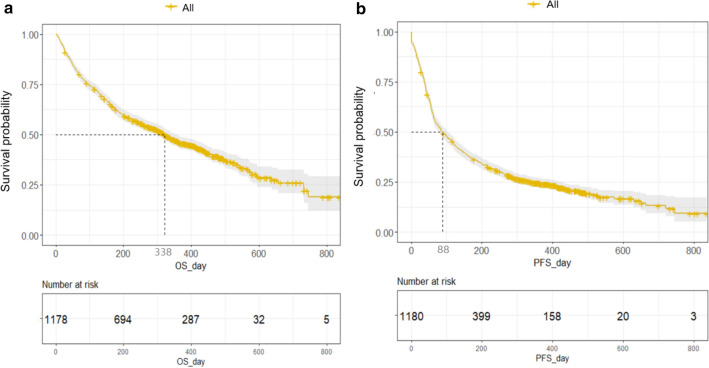

Estimation of survival outcomes was possible in 1,178 patients (99.7%). During the median follow-up of 10.5 months (range 0–28.2), the median PFS and OS of the survivors were 2.9 (95% CI 2.2–3.5) and 10.7 months (95% CI 9.7–11.8), respectively (Fig. 1). There was no significant survival difference between the pembrolizumab and nivolumab groups (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b) of the total of 1178 patients

Non-evaluable patients

While response assessment data were available for 1026 (86.9%, evaluable group), there was no documentation of assessment record in 155 patients (13.1%, non-evaluable group) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Comparing clinicopathologic parameters between these two group, significantly more patients with old age and poor ECOG-PS were included in the non-evaluable group (p = 0.024 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Supplementary Table 4). Moreover, both OS and PFS were significantly worse in the non-evaluable group compared to the evaluable group (both p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Toxicity

A total of 573 of 1181 patients (48.5%) experienced adverse events (AEs) at least once during treatment with ICIs. The irAEs comprised 42.6% (n = 244) of all AEs, which was 20.7% of all patients. Toxicities were mostly grade 1 or 2, and the most frequent AE was a skin problem, including non-specific rash, eczema, or psoriasis (5.9%). Two most commonly noticed irAEs were pneumonitis (n = 34, 2.9%) and hypothyroidism (2.2%). Among the 33 patients who experienced ≥ grade 3 irAEs, pneumonitis was most frequent, constituting 44.4% of all the irAEs (Table 3). After AEs occurred, 64% of the patients continued to receive treatment with ICIs treatment, and ICIs were retried in 5% of patients after a temporary suspension. Twenty-four percent of patients permanently discontinued the treatment regardless of their recovery. Interestingly, in more than half of the cases, physicians conferred a positive association of ICIs with the aforementioned AEs. Corticosteroid was administered to manage irAEs in 20% of patients.

Table 3.

Summary of any adverse events (AEs), their grade (A), type of AEs in > 3% of all patients (B), and immune-related AEs (irAEs) in ≥ grade3 (C) during treatment with ICIs in the 1181 total patients

| Total n, 573 (100%) | |

|---|---|

| n (%) [% of patients with toxicity] | |

| A. General summary of any AEs and their grade | |

| Type of AE | |

| AE only | 329 (57.42%) |

| irAE only | 152 (26.53%) |

| AE and irAE | 92 (16.06%) |

| Severity | |

| Grade 1 | 212 (17.95%) [37.0] |

| Grade 2 | 248 (21.00%) [43.3] |

| Grade 3 | 96 (8.13%) [16.8] |

| Grade 4 | 10 (0.85%) [1.7] |

| Grade 5 | 7 (0.59%) [1.2] |

| ≥ Grade 3 | 113 (9.57) [19.7] |

| Type of AE | Total n, 573 (100%) |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| B. Any AEs with incidence > 3% in all patients | |

| Skin rash or skin problem | 69 (12.04%) |

| Asthenia or fatigue | 49 (8.55%) |

| Pneumonitis | 34 (5.93%) |

| Pruritis | 32 (5.58%) |

| Dyspnea or DOE | 30 (5.24%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 26 (4.54%) |

| irAE | Total n = 36 (1.5% of all irAEs) |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| C. Summary of irAEs ≥ grade 3 | |

| Pneumonitis | 16 (44.44%) |

| Skin rash or skin problem | 5 (13.89%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (2.78%) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1 (2.78%) |

| Hepatitis | 1 (2.78%) |

| Other | 12 (33.33%) |

Biomarker analysis of efficacy outcomes

Objective response

Univariable and multivariable analyses of ORR are summarized in Supplementary Table 5. Univariable analysis revealed that PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% either in one or both assays was a significant predictor of higher ORR. ORR was also positively associated with prior smoking history and irAEs. Interestingly, underlying autoimmune disease or concurrent malignancies did not affect ORR. In multivariable analysis, prior irradiation was associated with a significantly lower ORR [Odds ratio (OR) 0.44, 95% CI 0.23–0.87, p < 0.017], whereas development of irAE (OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.46–5.09, p = 0.002) and PD-L1 TPS > 50% in both assays (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.22–4.61, p = 0.011) were two independent predictors of favorable ORR (Supplementary Table 5). Interestingly, underlying autoimmune disease or concurrent malignancies did not affect ORR.

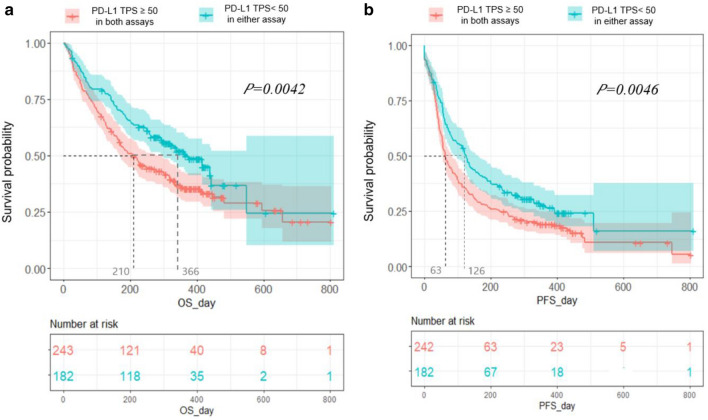

Survival outcomes

Univariable and multivariable analyses of OS are summarized in Table 4. In multivariable analysis, development of irAE [Hazard ratio (HR) 0.53, 95% CI 0.33–0.86), p < 0.001] and simultaneous PD-L1 TPS over 50% (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40–0.93, p < 0.022) consistently predicted better OS, while EGFR activating mutation was an independent negative predictor (HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.08–3.31, p = 0.026) (Table 4). Regarding PFS, the multivariable analysis revealed that irAEs could also predict more favorable outcomes (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.32–0.85, p < 0.009) (Supplementary Table 6). Concordance of TPS > 50% by both PD-L1 assays could consistently predict better PFS, but only in univariable analysis (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.92, p < 0.021) (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of clinicopathologic parameters in association with overall survival (OS) in all patients

| OS | Total n = 1178 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Univariable Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

P | Multivariable Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

P |

| Age | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 1.18 (1.01, 1.37) | 0.035 | 1.11 (0.73, 1.69) | 0.795 |

| ECOG-PS | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 1.09 (0.66, 1.79) | 0.741 | ||

| Historic subtype | ||||

| SqCC | 1.13 (0.96, 1.32) | 0.150 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| IV | 1.85 (1.25, 2.74) | 0.002 | 1.23 (0.51, 3.82) | 0.675 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.79, 1.12) | 0.487 | ||

| PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% | ||||

| In both assays | 0.69 (0.53, 0.89) | 0.004 | 0.61 (0.40, 0.93) | 0.022 |

| In either assay | 0.95 (0.80, 1.13) | 0.573 | ||

| EGFR | ||||

| Positive | 1.35 (1.07, 1.69) | 0.011 | 1.89 (1.08, 3.31) | 0.026 |

| ALK | ||||

| Positive | 0.70 (0.43, 1.15) | 0.160 | ||

| Underlying autoimmune disease | ||||

| Yes | 1.19 (0.30, 4.79) | 0.804 | ||

| Co-malignancy | ||||

| Yes | 0.81 (0.58, 1.13) | 0.214 | ||

| irAE | ||||

| Yes | 0.55 (0.44, 0.68) | < .001 | 0.53 (0.33, 0.86) | 0.001 |

| Type of ICIs | ||||

| Nivolumab | 0.97 (0.83, 1.13) | 0.690 | ||

| Prior radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 1.24 (1.06, 1.46) | 0.008 | 1.41 (0.83, 2.39) | 0.206 |

| RTx site | ||||

| Distant metastatic sites | 1.37 (1.10, 1.71) | 0.005 | 1.06 (0.62,1.83) | 0.824 |

| Metastatic sites | ||||

| Liver | 1.05 (0.90, 1.23) | 0.536 | ||

| Lung | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 0.296 | ||

| Pleura | 1.13 (0.95, 1.35) | 0.166 | ||

| Lymph node | 1.06 (0.91, 1.23) | 0.488 | ||

| Adrenal gland | 1.11 (0.87, 1.42) | 0.405 | ||

| Bone | 1.45 (1.23, 1.70) | < .001 | 1.22 (0.76, 1.93) | 0.412 |

| Brain or LMS | 1.24 (1.04, 1.48) | 0.018 | 0.61 (0.36, 1.04) | 0.067 |

| Previous line of chemotherapy | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 1.05 (0.88, 1.26) | 0.598 | ||

PS performance status, TPS tumor proportion score, irAE immune-related adverse events, ICIs immune-checkpoint inhibitors, RTx radiotherapy, LMS leptomeningeal seeding

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b) according to the cutoff of PD-L1 TPS 50% by both the 22C3 or SP263 assays

EGFR mutations and efficacy outcomes

Patients with EGFR mutations were found to have significantly worse ORR in univariable analysis, although it did not reach the statistical significance in multivariable analysis. EGFR-mutated patients showed 34.8% of ORR while patients without EGFR mutation achieved 24.8% (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.20–0.1.37, p < 0.189) (Supplementary Table 5). Consistently, patients harboring EGFR mutations showed longer median PFS compared with EGFR wild-type patients (3.3 M vs 2.03 M) (OR 1.45, 95% CI 0.82–2.60, p < 0.205) (Supplementary Table 6; Fig. 3). Most importantly, EGFR mutations were significantly associated with poorer OS outcomes that median OS of patients with and without EGFR mutations were 7.5 months and 11.3 months, respectively (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.08–3.31, p < 0.026) (Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

In the study, we evaluated the real-world efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 antibodies and their potential practical predictors in patients with PD-L1-positive, platinum-refractory R/M-NSCLC. Efficacy outcomes were generally comparable with landmark clinical trials. ORR was approximately 30% and durable with a median DOR of 13 months, and the median PFS and OS were 2.9 and 10.7 months, respectively. Biomarker analysis identified the concordance of PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% and the development of irAEs as two consistent predictors of improved ORR, PFS, and OS. EGFR mutations could also predict significantly worse OS outcomes in the cohort.

Current multi-center registry, to our best knowledge, constitutes the largest series of R/M-NSCLC accompanying with complete assessment of PD-L1 in the real-world setting. Predictive value of PD-L1 has been strongly supported by the results of several landmark trials in R/M-NSCLC, and also have been reproduced in some real-world investigations (Ahn et al. 2019; Garon et al. 2019; Herbst et al. 2016; Rittmeyer et al. 2017). Meanwhile, the robustness of PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker has been debated for a long time, with critics citing the inevitable heterogeneity of expression and its conflicting immunologic functions (Buttner et al. 2017; Herbst et al. 2014; Torlakovic et al. 2020; Velcheti et al. 2018). In this context, our findings bolster the value of PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% as an independent predictor of treatment outcomes with ICIs, particularly when concordantly observed in both SP263 and 22C3 assays. Notably, patients with TPS ≥ 50% in the nivolumab group displayed better survival outcomes than did patients with TPS < 50%, and their ORR was comparable to patients in the pembrolizumab group. Thus, we can carefully speculate that the predictive impact of PD-L1 might be magnified with the cutoff value of TPS 50 in patients with R/M-NSCLC, irrespective of the type of assay or drugs.

Another notable finding of the study is that we observed EGFR sensitizing mutations as the significant negative predictor of OS, which once again suggests the lack of efficacy of ICIs monotherapy in these patients. This agrees with the Checkmate-057, Keynote-010, and OAK phase III trials (Borghaei et al. 2015; Herbst et al. 2016; Rittmeyer et al. 2017) and other studies (Ahn et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2017). Although the impact of activating EGFR mutations on the sensitivity of ICIs is still controversial (Garassino et al. 2018; Mazieres et al. 2019), relatively lower tumor mutational burden and less engagement of CD8 + tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are regarded as the most plausible explanations for the negative association (Rizvi et al. 2015; Rozenblum et al. 2017). However, more recently, the observed heterogeneity of EGFR-mutant tumors suggested an allele-specific immunologic impact of EGFR mutations based on its mutational signatures (Hastings et al. 2019). We also observed prior irradiation as a negative predictor of the objective response. Although the mechanism remains unclear, radiotherapy may occasionally accelerate tumor growth in the irradiated field by promoting an immune-suppressive phenotype (Ogata et al. 2018; Seifert et al. 2016).

The development of irAEs was significantly correlated with better ORR and survival outcomes as consistently suggested in previous studies (Ahn et al. 2019; Haratani et al. 2018). Meanwhile, there could be a possible concern about potential confounding relationships between the treatment exposure, ORR, and development of irAEs, which was consistently suggested in latest long-term follow-up data of Keynote-001(Garon et al. 2019). Unfortunately, owing to its retrospective nature, we could not thoroughly review the exact onset of each irAE and make additional analysis between these parameters. However, based on previous studies regarding irAEs, we acknowledge various onsets of different types of irAEs and there has been no reliable evidence to support an association of treatment duration and rise of irAE incidence. Hence, at this time point, with more blocks of the evidences from recent studies (Das and Johnson 2019; Zhou et al. 2020), it seems still worthwhile to make active surveillance for irAEs rather than rashly abandoning the treatment. In particular, pneumonitis should be closely monitored and managed preemptively, given that it is the most frequently captured irAE with fatality in our routine practice (Suresh et al. 2019).

The study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospectively designed study with the inevitable selection bias. Our special inclusion criteria of PD-L1 (TPS ≥ 50% by 22C3 or ≥ 10% by SP263) could reinforce this pitfall. Moreover, the incidence of AEs might be generally underestimated, and its exact onset or severity could not be accurately defined, as it was based solely on medical records. And these might possibly add confounding bias regarding the predictive value of irAE. Second, 13% (n = 155) of the patients were excluded from the response assessment and its biomarker analysis. Further analysis of non-evaluable patients revealed significantly older age and poorer ECOG-PS of the group, and more importantly, inferior OS and PFS. Collectively, we can make a clinical assumption that a majority of non-evaluable patients might experience a graver clinical course, including hyper-progression, which fully reflects our real-world practice. Lastly, we cannot escape from the concern that predictive significance of concordant TPS ≥ 50 might be overestimated in the study, given that the concordance rate of PD-L1 TPS is better for the higher cutoff values in previous international harmonization project (Hirsch et al. 2017). But still, TPS 50 seems to have its practical value as it has been regarded the least controversial predictive cutoff point for mNSCLC patients treated with ICIs (Garon et al. 2019; Horn et al. 2017).

Compared with reference trials (Borghaei et al. 2015; Brahmer et al. 2015; Herbst et al. 2016), we acknowledge a substantial discrepancy in eligibility. The cohort comprised higher percentages of adverse features against ICIs treatment; older patients, poorer ECOG-PS, never-smokers, squamous cell carcinoma, brain metastasis, more heavily pretreated patients, and EGFR or ALK aberrations. Nonetheless, the magnitude of therapeutic benefit was preserved, particularly in terms of response in the study. ORR (29%) was comparable with those of patients with TPS ≥ 50% in the Keynote-010 trial (30%) and with a TPS ≥ 10% in the CheckMate-057 trial (37%) (Borghaei et al. 2015; Herbst et al. 2016), which was even higher than that of the CheckMate-017 trial (20%) (Brahmer et al. 2015). This encouraging result might be primarily attributed to highly-selected PD-L1-positivity, such that 73% of patients demonstrated TPS ≥ 50% in either assay. However, survival outcomes were relatively disappointing, particularly concerning OS. The median OS of 10.7 months was considerably shorter than those of patients with TPS ≥ 50% in the Keynote-010 trial (14.9 months) or with TPS ≥ 10% in the CheckMate-057 trial (19.9 months). An insufficient follow-up duration of the study might have partly affected the OS underestimation. However, more importantly, the aforementioned distinct characteristics of real-world population, which were more obvious in non-evaluable patients, might be a major contributor to the relatively unfavorable outcomes.

Interestingly, lines of ICI treatment did not affect the efficacy in our study, which encourages the salvage treatment with ICIs in ICIs-naïve patients. In addition, concurrent autoimmune diseases (2.6%) and other malignancies (4.8%) that usually preclude the clinical trials, also did not influence the treatment outcomes as suggested in two recent studies (Ahn et al. 2019; Smit et al. 2020). Therefore, in clinical practice, drastic treatment with ICIs is consistently recommended in these comorbid patients if the magnitude of clinical benefits is judged to be significant.

In conclusion, although the real-world patients distinctly presented more unfavorable features, later-line anti-PD1 antibodies conferred a comparable benefit to patients with PD-L1-positive R/M-NSCLC, particularly in terms of the response rate. Survival outcomes were relatively discouraging, but might represent real-world heterogeneity outside the clinical trials. Current study strongly endorses concordant PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% and development of irAE as two relevant and feasible predictive biomarkers of ICIs treatment. Collectively, it might further help providing more efficient ICI treatment strategy in patients with R/M-NSCLC, filling the gap between the real-world and clinical trial outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Current multicenter research was initiated and supported by the collaboration from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service of Korea (201812072D200) and by the Korean Cancer Study Group (KCSG LU19-05). And this work was supported by Konkuk University Medical Center Research Grant 2018. Lastly, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Author contributions

LSK SMO gave a core assistance in data collection and developing a raw registry, which was thoroughly guided by JHP and JHK. GLR and HA made a final dataset, and made all statistical analyses for the study. JHP reviewed the literature, interpreted the data analysis, and mainly drafted the article. JHK initially inspired and motivated the concept of present study, who finally reviewed and confirmed the final version to be published. All co-authors listed equally contributed to enrollment of patients as expert medical oncologists or pulmonologists of lung cancer, and they all read and approved the final article.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No author has any financial disclosures to declare related to this study.

Research involving human participants

It was conducted in full accordance with the guidelines for the Good Clinical Practice and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (of each participant center), and informed consents were achieved from all individual participants included in the study.

Informed consent to publication

All co-authors included in the study agreed with publication of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hyonggin An and Jin Hyoung Kang equally contributed to this study.

References

- Ahn BC et al (2019) Comprehensive analysis of the characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with anti-PD-1 therapy in real-world practice. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145:1613–1623. 10.1007/s00432-019-02899-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghaei H et al (2015) Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:1627–1639. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer J et al (2015) Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:123–135. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner R et al (2017) Programmed death-ligand 1 immunohistochemistry testing: a review of analytical assays and clinical implementation in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 35:3867–3876. 10.1200/jco.2017.74.7642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Johnson DB (2019) Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors . J Immunother Cancer 7:306. 10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer EA et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi L et al (2018) Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378:2078–2092. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garassino MC et al (2018) Durvalumab as third-line or later treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (ATLANTIC): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 19:521–536. 10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30144-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon EB et al (2019) Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study. J Clin Oncol 37:2518–2527. 10.1200/JCO.19.00934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haratani K et al (2018) Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 4:374–378. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings K et al (2019) EGFR mutation subtypes and response to immune checkpoint blockade treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer . Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 30:1311–1320. 10.1093/annonc/mdz141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service K (2019) Administrative rules for listed anti-cancer drugs (2020–81)

- Herbst RS et al (2014) Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 515:563–567. 10.1038/nature14011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst RS et al (2016) Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl 387:1540–1550. 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch FR et al (2017) PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assays for lung cancer: results from phase 1 of the blueprint PD-L1 IHC assay comparison project. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 12:208–222. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn L et al (2017) Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: two-year outcomes from two randomized, open-label, phase III trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057). J Clin Oncol 35:3924–3933. 10.1200/jco.2017.74.3062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, Links M, Gebski V, Mok T, Yang JC (2017) Checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer—a meta-analysis . J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 12:403–407. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazieres J et al (2019) Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry . Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 30:1321–1328. 10.1093/annonc/mdz167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health NCI, U.S. Department of Health and Human services (2017) Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), Version 5.0

- Ogata T, Satake H, Ogata M, Hatachi Y, Yasui H (2018) Hyperprogressive disease in the irradiation field after a single dose of nivolumab for gastric cancer: a case report . Case Rep Oncol 11:143–150. 10.1159/000487477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck M et al (2016) Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1823–1833. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmeyer A et al (2017) Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl 389:255–265. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32517-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi NA et al (2015) Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci NY NY) 348:124–128. 10.1126/science.aaa1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach C et al (2016) Development of a companion diagnostic PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay for pembrolizumab therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 24:392–397. 10.1097/pai.0000000000000408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenblum AB, Ilouze M, Dudnik E, Dvir A, Soussan-Gutman L, Geva S, Peled N (2017) Clinical impact of hybrid capture-based next-generation sequencing on changes in treatment decisions in lung cancer . J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 12:258–268. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert L et al (2016) Radiation therapy induces macrophages to suppress T-cell responses against pancreatic tumors in mice. Gastroenterology 150:1659-1672.e1655. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit HJM et al (2020) Effects of checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer at population level from the National Immunotherapy Registry. Lung Cancer Amst Neth 140:107–112. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh K et al (2019) Impact of checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis on survival in NSCLC patients receiving immune checkpoint immunotherapy . J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 14:494–502. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torlakovic E et al (2020) “Interchangeability” of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assays: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Mod Pathol 33:4–17. 10.1038/s41379-019-0327-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournoy KG et al (2018) Does nivolumab for progressed metastatic lung cancer fulfill its promises? An efficacy and safety analysis in 20 general hospitals. Lung Cancer Amst Neth 115:49–55. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcheti V, Patwardhan PD, Liu FX, Chen X, Cao X, Burke T (2018) Real-world PD-L1 testing and distribution of PD-L1 tumor expression by immunohistochemistry assay type among patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. PLoS ONE 13:e0206370–e0206370. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Keam B, Kim M, Kim TM, Kim DW, Heo DS (2018) Generalization and representativeness of phase III immune checkpoint blockade trials in non-small cell lung cancer. Thoracic cancer 9:736–744. 10.1111/1759-7714.12641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Yao Z, Yang H, Liang N, Zhang X, Zhang F (2020) Are immune-related adverse events associated with the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 18:87. 10.1186/s12916-020-01549-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.