Abstract

Purpose

In metastatic breast cancer (MBC) population treated with capecitabine monotherapy, we investigated clinical-pathological features as possible biomarkers for the oncological outcome.

Methods

Retrospective study of consecutive MBC patients treated at University Hospitals Leuven starting capecitabine between 1999 and 2017. The primary endpoint was the durable response (DR), defined as non-progressive disease for > 52 weeks. Other main endpoints were objective response rate (ORR), time to progression (TTP) and overall survival (OS).

Results

We included 506 patients; mean age at primary breast cancer diagnosis was 51.2 years; 18.2% had de novo MBC; 98.8% were pre-treated with taxanes and/or anthracycline. DR was reached in 11.6%. Patients with DR, as compared to those without DR, were more likely oestrogen receptor (ER) positive (91.5% vs. 76.8%, p = 0.010) at first diagnosis, had a lower incidence of lymph node (LN) involvement (35.6% vs. 49.9%, p = 0.039) before starting capecitabine, were more likely to present with metastases limited to ≤ 2 involved sites (54.2% vs. 38.5%, p = 0.020) and time from metastasis to start of capecitabine was longer (mean 3.5 vs. 2.7 years, p = 0.020). ORR was 22%. Median TTP and OS were 28 and 58 weeks, respectively. In multivariate analysis (only performed for TTP), ER positivity (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.529, p < 0.0001), HER2 negativity (HR = 0.582, p = 0.024), absence of LN (HR = 0.751, p = 0.008) and liver involvement (HR = 0.746, p = 0.013), older age at capecitabine start (HR = 0.925, p < 0.0001) and younger age at diagnosis of MBC (HR = 0.935, p = 0.001) were significant features of longer TTP.

Conclusion

Our data display relevant clinical-pathological features associated with DR and TTP in patients receiving capecitabine monotherapy for MBC.

Keywords: Capecitabine monotherapy, Durable response, Metastatic breast cancer, Treatment efficacy

Introduction

The most important goals of therapy in advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are to optimise disease control while maintaining a good quality of life (Barchiesi et al. 2019).

Capecitabine (Xeloda®), a chemotherapeutic agent which belongs to the drug class of fluoropyrimidines, is known for its strong anti-tumour activity, also in reduced dose, and overall favourable toxicity profile (Yin et al. 2015). This, together with the advantages of oral administration and the lack of alopecia, makes capecitabine monotherapy an interesting agent in advanced breast cancer.

This chemotherapeutic agent is designed as a prodrug that is enzymatically converted in the liver and in cancerous tissue to its active form 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (Tabata et al. 2004; Dean 2012). One of the final steps in this activation pathway is catalysed by thymidine phosphorylase, present in 3–tenfold higher concentration in cancer cells compared to normal cells. Consequently, the effect of capecitabine is concentrated within these cancer cells and therefore causes less systemic toxicity events (Miwa et al. 1998; Saif et al. 2008; White et al. 2014). Thymidine phosphorylase also converts 5-FU to fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate which causes inhibition of thymidylate synthase. The absence of thymidylate synthase, essential for DNA synthesis and repair, blocks proliferation and causes cell death (Costi et al. 2005; Wilson et al. 2008). In addition, two other active metabolites of 5-FU, fluorodeoxyuridine triphosphate and fluorouridine triphosphate, can be incorporated into DNA and RNA, finally also leading to cell death (Wilson et al. 2014). Afterwards, 5-FU is inactivated by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) (Dean 2012).

The most common adverse effects noticed in ≥ 5% of the patients include diarrhoea, stomatitis, nausea and vomiting, hand-foot syndrome, dermatitis, fatigue and cytopenia. Angina pectoris is a less common side effect which is reported in 0.2% of the patients ([CSL STYLE ERROR: reference with no printed form (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2015)]). In respectively 0.5% and 8% of Caucasians a DPD enzyme lack or low levels are present due to homozygous or heterozygous mutations in the DPYD gene which, because of decreased inactivation of 5-FU, can lead to severe and life-threatening side effects such as neutropenia, neurotoxicity, severe diarrhoea and stomatitis. Consequently, testing of patients for DPD deficiency prior to capecitabine use is recently (March 2020) recommended by EMA.

Capecitabine monotherapy is approved and reimbursed in Belgium for more than 2 decades in MBC when used after failure of taxanes and anthracyclines (unless there is a contraindication for the anthracycline-based regimen). However, the duration of response varies highly among patients. In the past, several studies were performed to evaluate characteristics of durable response to capecitabine monotherapy in MBC patients (Siva et al. 2008; Osako et al. 2009), though these studies had a small sample size. A study of Hong et al. (2015) included 236 patients who received second-or further line palliative capecitabine monotherapy after previous treatment with anthracycline-and taxanes containing regimens. It demonstrated that oestrogen receptor (ER) positivity, absence of lymph nodes and single-organ metastasis were clinical features of response of ≥ 12 months. This is the only study performed with a large number of patients.

A randomized phase III trial published in 2018 (vinflunine plus capecitabine vs. capecitabine alone in patients with advanced breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and resistant to taxane) found an objective response rate (ORR) of 23%, a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 19 weeks and a median overall survival (OS) of 51 weeks for patients treated with capecitabine monotherapy (Martin et al. 2018).

In our study, we investigated clinical and pathologic features as possible biomarkers correlated to durable response (DR), as well as ORR, time to progression (TTP) and OS in MBC patients treated with capecitabine monotherapy.

Patients and methods

Study design

This monocentric retrospective study was performed at University Hospitals Leuven and included MBC patients starting capecitabine monotherapy between March 1999 and November 2017. Follow-up ended in May 2019. Patients who received a combination therapy with capecitabine and patients who received prior capecitabine monotherapy in early/advanced setting were excluded. Patients with HER2- positive disease were allowed as long as capecitabine was given in monotherapy.

Following features were extracted from each patient file: clinical characteristics at breast cancer diagnosis such as age, tumour setting (early breast cancer, neoadjuvant, metastatic), TNM classification, age at metastatic relapse, age and dose at the start of capecitabine monotherapy, dose reduction, survival status and cause of death, tumour characteristics including histological type (invasive breast carcinoma of no special type (NST), invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), mixed, other) and receptor status ([ER, progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)]) at the diagnosis of breast cancer, previous treatments (endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy), metastatic disease characteristics such as involved organs before start of capecitabine based on imaging studies (brain, abdomen without liver, liver, cutaneous, lung, pleura, bone, lymph node (LN), other), time to treatment discontinuation (in weeks), reason of discontinuation of capecitabine and best response on capecitabine.

All patients initiated capecitabine monotherapy in a 2-week on/1-week off schedule.

Treatment responses were evaluated at baseline and at (variable) subsequent time points according to clinical judgement using clinical examination and appropriate imaging, like computed tomography, whole-body diffusion weight magnetic resonance imaging or bone scan. Best objective responses were classified based on Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours (RECIST) v1.1, mainly retrospectively by the first author in 2019.

As we wanted to compare our data with the study of Hong et al. (2015), DR was defined as non-progressive disease for longer than 52 weeks. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved a complete response or partial response as their best overall response across all time points based on RECIST v1.1. TTP was defined as the time between the start of capecitabine monotherapy and progressive disease. Patients were censored at the time of terminating treatment for other reasons than a progression, or at last follow-up when still on treatment. OS was defined as the time between initiation of first-line capecitabine monotherapy till the date of death of any cause. Patients alive were censored at last follow-up.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (MP008844).

Statistical analysis

Baseline features were summarized as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and as means with standard deviation (Std) and/or medians with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables.

The cumulative incidence function was used for estimating TTP, accounting for treatment stop for other reasons as competing events. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for estimating OS.

Comparison between patients with and without DR was performed using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used for the analysis of time-to-event outcomes. A forward stepwise selection procedure was utilized for a multivariable model, with a 5% level for variables to enter or to leave the model. Results were presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All tests were two sided and a 5% significance level was assumed. Analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows).

Results

Baseline patient and treatment characteristics

Between March 1999 and November 2017, a total of 506 patients started capecitabine monotherapy; 92/506 (18.2%) were de novo metastatic at primary breast cancer diagnosis and 500/506 (98.8%) were pre-treated with taxanes and/or anthracycline in neoadjuvant, adjuvant and/or metastatic setting. The mean age at primary breast cancer diagnosis was 51.2 years (Std 11.2, range 22–85 years); the mean age at diagnosis of metastasis was 55.9 years (Std 11.3, range 24–88 years), while mean age at start capecitabine was 58.9 years (Std 11.5, range 24–90 years). At the moment of analysis, 3/506 (0.6%) patients were still on treatment; 392/506 (77.5%) discontinued capecitabine treatment due to progression and 111/506 (21.9%) for other reasons (toxicity (n = 38), elevation tumour marker without evident changes on imaging studies (n = 10) or before imaging studies were done (n = 2), physical decline (n = 28), treatment-break (n = 7), death (n = 23) or other reason (n = 3)).

The starting dose was 1000, 1250 or 950 mg/m2 bid in 51.2%, 16.6% and 15.8% respectively depending on the clinical setting and age (8.7% started at lower dose; 7.7% unknown dose). 28.9% of patients required a dose reduction (unknown in 5.7%).

HER2 positivity at primary breast cancer diagnosis was present in 26/506 patients (5.1%); 18/26 (69.2%) received the previous HER2 targeted treatment. In 5/8 patients who did not receive it previously, HER2 targeted agents were administered after discontinuation of capecitabine monotherapy. 1/8 patients had a contraindication for anti-HER2 therapy.

Median follow-up since the start of capecitabine was 53 weeks (IQR 21; 98 weeks) and median duration of treatment was 18 weeks (IQR 9; 34 weeks). Among 506 patients, 59 patients (11.6%) achieved DR.

Best response outcomes are summarized in Table 1. ORR was 22.0%. In 54/506 patients (10.7%) best objective response was not evaluable, mainly due to stop capecitabine before imaging could be performed.

Table 1.

Best response outcomes to capecitabine monotherapy

| Best response outcome | n/N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 5/506 | 1.0 |

| Partial response | 106/506 | 21.0 |

| Stable disease | 190/506 | 37.6 |

| Progressive disease | 151/506 | 29.8 |

| Not evaluable | 54/506 | 10.7 |

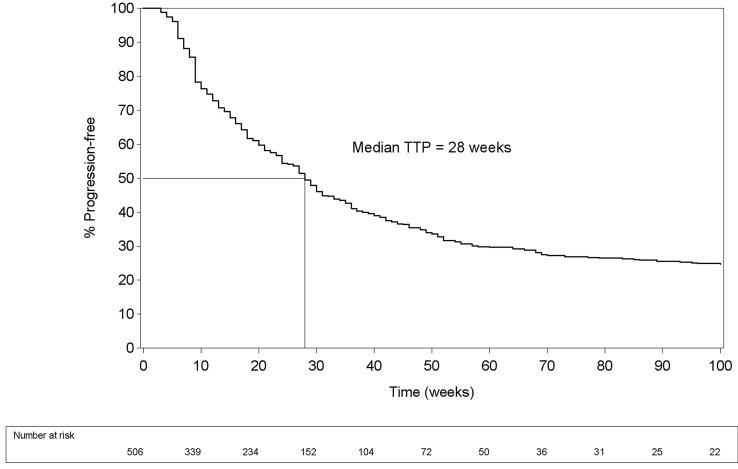

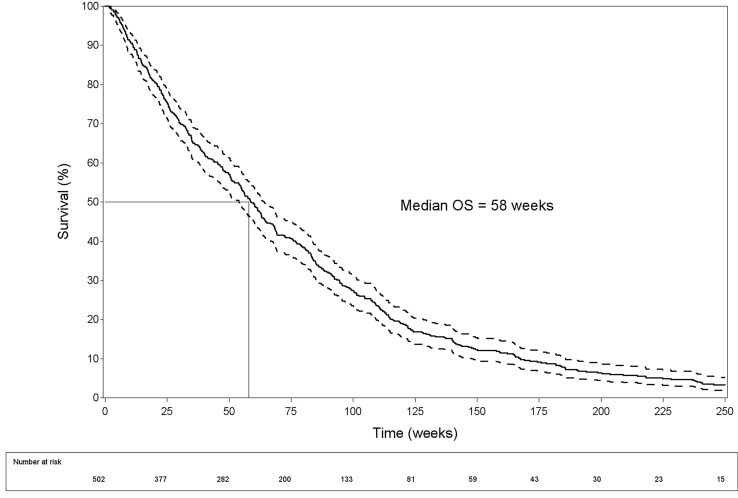

Median TTP was 28 weeks (IQR 11; 96 weeks) (Fig. 1) and median OS 58 weeks (IQR 25; 106 weeks) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Time to progression (TTP) curve

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (OS) curve with 95% confidence intervals

Comparison between DR group and non-DR group

Primary breast cancer characteristics of patients according to DR are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primary breast cancer characteristics in non-DR and DR group

| Characteristics | Non-DR group n = 447 | DR-group n = 59 | Total n = 506 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (Std) at diagnosis | 51.1 (11.3) | 51.3 (10.4) | 51.2 (11.2) | 0.888 |

| Tumour setting (%): | 0.234 | |||

| Early breast cancer | 290 (64.9) | 43 (72.9) | 333 (65.8) | |

| Neoadjuvant | 71 (15.9) | 10 (17.0) | 81 (16.0) | |

| Metastatic | 86 (19.2) | 6 (10.2) | 92 (18.2) | |

| Dose at start capecitabine monotherapy: | 0.591 | |||

| Mean (Std, mg/m2 bid) | 936.3 (283.3) | 957.15 (247.0) | 938.8 (279.2) | |

| Median (IQR, mg/m2 bid) | 1000.0 (950.0; 1000.0) | 1000.0 (950.0; 1000.0) | 1000.0 (950.0; 1000.0) | |

| Histological type tumour (%): | 0.470 | |||

| NST | 358 (80.3) | 43 (72.9) | 401 (79.4) | |

| ILC | 57 (12.8) | 9 (15.3) | 66 (13.7) | |

| Mixed | 15 (3.4) | 4 (6.8) | 19 (3.8) | |

| Other | 16 (3.6) | 3 (5.1) | 19 (3.8) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||

| Receptor status (%): | ||||

| ER + | 341 (76.8) | 54 (91.5) | 395 (78.5) | 0.010 |

| PR + | 287 (64.6) | 43 (72.9) | 330 (65.6) | 0.211 |

| HER2 + | 25 (5.6) | 1 (1.7) | 26 (5.2) | 0.200 |

| Unknown | 3 | 3 | ||

| Breast cancer subtype (%): | 0.034 | |||

| ER + PR + HER2- | 273 (61.1) | 43 (72.9) | 316 (62.5) | |

| ER + PR-HER2- | 53 (11.9) | 11 (18.6) | 64 (12.6) | |

| ER-PR + HER2- | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.0) | |

| ER + PR-HER2 + | 6 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | |

| ER-PR-HER2 + | 10 (2.2) | 1 (1.7) | 11 (2.2) | |

| Triple-negative | 88 (19.8) | 4 (6.8) | 92 (18.2) | |

| Triple-positive | 9 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.8) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 3 | ||

DR durable response; Std standard deviation; IQR interquartile range; NST invasive. breast carcinoma of no special type; ILC invasive lobular carcinoma; ER oestrogen receptor; PR progesterone receptor; HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

Patients with DR were more likely ER positive (91.5% vs. 76.8%, p = 0.010) at diagnosis as compared to patients without DR. Consequently, they were also more likely ER + PR + HER2- (72.9% vs. 61.1%), ER + PR-HER2- (18.6% vs. 11.9%) and less likely triple-negative (6.8% vs. 19.8%) concerning the breast cancer subtype (p = 0.034). No differences were seen between DR- and non-DR group concerning the age at diagnosis, tumour setting (early breast cancer, neoadjuvant, metastatic), dose at the start of capecitabine monotherapy, clinical and pathological TNM stage, histologic type of tumour, as well as HER2 status and PR status.

In Table 3, previous treatments were compared between DR group and non-DR group. Patients with DR received more frequently endocrine therapy in adjuvant (62.7% vs. 47.7%, p = 0.030) and metastatic setting (88.1% vs. 73.38%, p = 0.014), as well as less taxanes during palliative treatment (67.8% vs. 83.7%, p = 0.003).

Table 3.

Previous treatments in non-DR and DR group

| Treatment | Non-DR group n = 447 (%) | DR-group n = 59 (%) | Total n = 506 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy | 12 (2.7) | 3 (5.1) | 15 (3.0) | 0.307 |

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | 213 (47.7) | 37 (62.7) | 250 (49.4) | 0.030 |

| Metastatic endocrine therapy | 328 (73.4) | 52 (88.1) | 380 (75.1) | 0.014 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 75 (16.8) | 11 (18.6) | 86 (17.0) | 0.720 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 186 (41.6) | 27 (45.8) | 213 (42.1) | 0.544 |

| Perioperative chemotherapy | ||||

| Taxane-containing regimen | 118 (40.7) | 14 (13.7) | 132 (26.1) | 0.199 |

| Anthracycline-containing regimen | 183 (40.9) | 26 (44.1) | 209 (41.3) | 0.294 |

| Palliative chemotherapy | ||||

| Taxane-containing regimen | 374 (83.7) | 40 (67.8) | 414 (81.8) | 0.003 |

| Anthracycline-containing regimen | 251 (56.2) | 26 (44.1) | 277 (54.7) | 0.082 |

DR durable response

MBC characteristics are shown in Table 4. A longer interval from the first metastasis to start capecitabine was seen in the DR-group compared to non-DR group (mean 3.5 years vs. 2.7 years, p = 0.023). Patients with DR had also a lower incidence of LN involvement before the start of capecitabine (35.6% vs. 49.9%, p = 0.039), as well as more often metastases limited to ≤ 2 involved sites (54.2% vs. 38.5%, p = 0.020).

Table 4.

Metastatic breast cancer characteristics in non-DR and DR group

| Characteristics | Non-DR group n = 447 | DR-group n = 59 | Total n = 506 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (Std) at diagnosis metastatic disease | 55.8 (11.3) | 57.4 (11.0) | 56.0 (11.3) | 0.286 |

| Mean years (Std) between diagnosis breast cancer and metastasis | 5.2 (5.8) | 6.6 (6.0) | 5.4 (5.8) | 0.092 |

| Number palliative lines chemotherapy and targeted therapy before capecitabine | 0.065 | |||

| Mean (Std) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.1) | |

| Median (Range) | 2.0 (0.0; 6.0) | 2.0 (0.0; 5.0) | 2.0 (0.0; 6.0) | |

| Mean age (Std) at start capecitabine | 58.6 (11.5) | 61.6 (11.1) | 58.9 (11.5) | 0.059 |

| Mean years (Std) between diagnosis metastasis and start capecitabine | 2.7 (2.6) | 3.5 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.7) | 0.023 |

| Metastatic sites (%) | ||||

| Brain | 67 (15.0) | 4 (6.8) | 71 (14.0) | 0.088 |

| Abdomen without liver | 111 (24.8) | 10 (17.0) | 121 (23.9) | 0.182 |

| Liver | 304 (68.0) | 35 (59.3) | 339 (67.0) | 0.182 |

| Cutaneous | 48 (10.7) | 6 (10.2) | 54 (10.7) | 0.894 |

| Lung | 140 (31.3) | 19 (32.2) | 159 (31.4) | 0.891 |

| Pleura | 69 (15.4) | 10 (17.0) | 79 (15.6) | 0.763 |

| Bone | 307 (68.7) | 43 (72.9) | 350 (69.2) | 0.511 |

| Lymph node | 223 (49.9) | 21 (35.6) | 244 (48.2) | 0.039 |

| Number of involved organs (%) | 0.020 | |||

| ≤ 2 organs | 172 (38.5) | 32 (54.2) | 204 (40.3) | |

| > 2 organs | 275 (61.5) | 27 (45.8) | 302 (59.7) | |

DR durable response; Std standard deviation

Multivariate analysis was not performed because of the small number of patients in the DR group and the high number of possible features.

Association of patient/disease characteristics with progression

In univariate analysis, the characteristics associated with better TTP were as follows: ER positivity (HR = 0.52 (0.411; 0.66), p < 0.0001)), PR positivity (HR = 0.72 (0.58; 0.89), p = 0.0019), adjuvant (HR = 0.82 (0.67; 0.99), p = 0.049) and metastatic endocrine therapy (HR = 0.53 (0.43;0.67), p < 0.0001), older age at metastatic disease (HR = 0.99 (0.98; 0.99), p = 0.029), older age at start capecitabine (HR = 0.98 (0.98; 0.99), p = 0.0003), absence of LN involvement before start of capecitabine (HR = 0.75 (0.61; 0.91), p = 0.0044), less than 2 involved organs before start of capecitabine (HR = 0.78 (0.63; 0.95), p = 0.0134) and longer time between metastasis to start capecitabine (HR = 0.92 (0.89; 0.96), p < 0.0001). There was also a significant association between subtype and TTP, with higher risk of progression for triple-negative patients compared to both ER + PR + HER2- (HR = 2.08 (1.60; 2.69), p < 0.0001) and ER + PR-HER2- (HR = 2.27 (1.56;3.30), p < 0.0001) patients.

In a multivariable model, shown in Table 5, ER positivity and HER2 negativity at diagnosis, absence of LN involvement and liver involvement before the start of capecitabine, older age at the start of capecitabine and younger age at metastatic disease were significant features of longer TTP.

Table 5.

Multivariable model for progression (forward stepwise selection procedure)

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ER positivity at diagnosis | 0.529 (0.403; 0.694) | < 0.0001 |

| HER2 negativity at diagnosis | 0.582 (0.363; 0.932) | 0.024 |

| Metastatic site: absence of liver involvement | 0.746 (0.592; 0.940) | 0.013 |

| Metastatic site: absence of lymph node involvement | 0.751 (0.608; 0.927) | 0.008 |

| Age start capecitabine | 0.925 (0.890; 0.962) | < 0.0001 |

| Age metastasis | 1.070 (1.029; 1.113) | 0.001 |

ER oestrogen receptor; HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR hazard ratio; CI confidence interval

Continuous predictor: HR for 1−unit increase. HR > (<) 1: increased (decreased) progression risk with increasing predictor level

Binary predictor: HR for indicated level versus reference. HR < 1: lower progression risk for indicated level

Discussion

In our study of 506 patients with MBC, 11.6% achieved DR (> 52 weeks). Compared to patients without DR, these patients were more likely ER positive at diagnosis and had a lower incidence of LN involvement before the start of capecitabine, as well as more often metastases limited to ≤ 2 involved sites. Furthermore, in patients with DR, time from first metastasis to start of capecitabine was longer. Patients with DR also received more often endocrine treatment in the adjuvant and metastatic setting, as well as less taxanes during palliative treatment. This higher incidence of endocrine therapy can probably be explained by the higher proportion of ER-positive status while less use of taxanes for stage IV disease reflects earlier use of capecitabine.

Hong et al. (2015) found a DR rate of 14%. They reported ER positivity, absence of lymph nodes and single-organ metastasis as clinical characteristics of DR to capecitabine monotherapy.

Concerning treatment efficacy, a systematic review of 8 phase II trials and 2 phase III trials enrolling 1494 patients, of whom 80% received taxanes and anthracyclines, showed an ORR of 18%, a median PFS of 18 weeks and a median OS of 59 weeks in patients treated with capecitabine monotherapy (Oostendorp et al. 2011). We calculated TTP instead of PFS, so the 23 patients who died during therapy with capecitabine were censored as ‘competing events’. Our data showed an ORR of 22%, a median duration of treatment of 18 weeks, a median TTP of 28 weeks and a median OS of 58 weeks. In the study of Hong et al. (2015) the number of patients who discontinued treatment with capecitabine due to another reason than PD or death, as well as the specific reason, have not been described.

Hong et al. (2015) suggested that ER positivity and single-organ metastasis can be predictive markers for better PFS. Our data show that ER positivity and HER2 negativity at diagnosis, absence of LN involvement and liver involvement before the start of capecitabine, older age at start capecitabine and younger age at metastatic disease are independent features of longer TTP. However, given the design of our study we are not able to distinguish between prognostic factors and factors predictive for the effect of capecitabine.

Even though other previous studies had a smaller sample size, they all showed that ER positivity has been associated with a better response (Lee et al. 2004; Osako et al. 2009). In 2011 Lee et al. (2011) reported that high levels of thymidylate synthase and low levels of thymidine phosphorylase along with hormonal subtypes were correlated with poor PFS with capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxanes-pretreated MBC. A recent study of Siddiqui et al. (2019) showed that thymidylate synthase levels were found significantly higher in poorly differentiated and in triple-negative breast cancer, which can be a possible explanation why ER positivity is associated with DR and longer TTP.

In addition to clinical-pathological features, gene expression analysis may also help to identify durable responders to capecitabine. Until now, only a small study is published in which molecular analyses of cancer tissue obtained from 6 ER-positive to HER2-negative MBC patients who had exceptional responses to capecitabine was performed. These data suggest that mutations which inactivate homologous recombination and/or chromatin remodelling genes within ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancers may predict for highly durable responses to capecitabine (Levin et al. 2015).

A limitation is that our findings are based on a retrospective analysis of a single-centre database. Moreover, a surrogate subtype evaluation is impossible because of the missing data for Ki-67 status. However, this study shows the results of the largest data set to validate biomarkers of DR to capecitabine monotherapy in advanced breast cancer.

Conclusion

Our data display relevant clinical-pathological features associated with DR and TTP in patients receiving capecitabine monotherapy for MBC.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by ST. Data analysis was conducted by ST and AL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ST and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

SAS software (version 9.4 of the SAS system for Windows).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (MP008844) in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Barchiesi G, Krasniqi E, Barba M et al (2019) Highly durable response to capecitabine in patient with metastatic estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 10.1097/md.0000000000017135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costi M, Ferrari S, Venturelli A et al (2005) Thymidylate Synthase Structure, Function and Implication in Drug Discovery. Curr Med Chem 12(19):2241–2258. 10.2174/0929867054864868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean L (2012) Capecitabine therapy and DPYD genotype. National Center for Biotechnology Information, US [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JY, Park YH, Choi MK et al (2015) Characterization of durable responder for capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 10.1016/j.clbc.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Lee J, Park J et al (2004) Capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Med Oncol. 10.1385/MO:21:3:223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, La CY, Park YH et al (2011) Thymidylate synthase and thymidine phosphorylase as predictive markers of capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 10.1007/s00280-010-1545-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MK, Wang K, Yelensky R et al (2015) Genomic alterations in DNA repair and chromatin remodeling genes in estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer patients with exceptional responses to capecitabine. Cancer Med. 10.1002/cam4.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Campone M, Bondarenko I et al (2018) Randomised phase III trial of vinflunine plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in patients with advanced breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and resistant to taxane. Ann Oncol. 10.1093/annonc/mdy063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M et al (1998) Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5 fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer. 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00058-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostendorp LJM, Stalmeier PFM, Donders ART et al (2011) Efficacy and safety of palliative chemotherapy for patients with advanced breast cancer pretreated with anthracyclines and taxanes: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 12(11):1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osako T, Ito Y, Ushijima M et al (2009) Predictive factors for efficacy of capecitabine in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 10.1007/s00280-008-0806-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saif MW, Katirtzoglou NA, Syrigos KN (2008) Capecitabine: An overview of the side effects and their management. Anticancer Drugs 19(5):447–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui A, Gollavilli PN, Schwab A et al (2019) Thymidylate synthase maintains the de-differentiated state of triple negative breast cancers. Cell Death Differ. 10.1038/s41418-019-0289-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siva M, Correa P, Skaria S, Canney P (2008) Capecitabine in advanced breast cancer: predictive factors for response. J Clin Oncol. 10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.1126 [Google Scholar]

- Tabata T, Katoh M, Tokudome S et al (2004) Bioactivation of capecitabine in human liver: Involvement of the cytosolic enzyme on 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine formation. Drug Metab Dispos. 10.1124/dmd.32.7.762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Lau PKH, Redfern AD, Bulsara MK (2014) Capecitabine for ER-positive versus ER-negative breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10.1002/14651858.CD011220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G et al (2008) Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PM, Danenberg PV, Johnston PG et al (2014) Standing the test of time: targeting thymidylate biosynthesis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 11(5):282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2015) Xeloda (capecitabine). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/020896s037lbl.pdf. (Accessed 8 Dec 2019)

- Yin W, Pei G, Liu G et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of capecitabine-based first-line chemotherapy in advanced or metastatic breast cancer: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Oncotarget. 10.18632/oncotarget.5460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

SAS software (version 9.4 of the SAS system for Windows).