Abstract

Purpose

As few genotype–phenotype correlations are available for nonsyndromic hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC), we implemented genomic analysis on the basis of the revised Bethesda guideline (RBG) and extended (12 items) to verify possible subtypes.

Methods

Patients with sporadic CRC (n = 249) were enrolled, stratified according to the revised Bethesda guidelines (RBG+ and RBG− groups) plus additional criteria. Exome/transcriptome analyses (n = 98) and cell-based functional assays were conducted.

Results

We detected 469 somatic and 830 germline gene mutations differing significantly between the positive and negative groups, associated with 12 RBG items/additional criteria. Twenty-one genes had significantly higher mutation rates in left, relative to right, colon cancer, while USP40, HCFC1, and HSPG2 mutation rates were higher in rectal than colon cancer. FAT4 mutation rates were lower in early-onset CRC, in contrast to increased rates in microsatellite instability (MSI)-positive tumors, potentially defining an early-onset microsatellite-stable subtype. The mutation rates of COL6A5 and MGAM2 were significantly and SETD5 was assumably, associated CRC pedigree with concurrent gastric cancer (GC). The predicted deleterious/damaging germline variants, SH2D4A rs35647122, was associated with synchronous/metachronous CRC with related tumors, while NUP160 rs381660 and KRTAP27-1 rs2244485 were potentially associated with a GC pedigree and less strictly defined hereditary CRC, respectively. SH2D4A and NUP160 acted as oncogenic facilitators.

Conclusion

Our limited genomic analysis for RBG and additional items suggested that specific somatic alterations in the respective items may enlighten relevant pathogenesis along with the knowledge of germline mutations. Further validation is needed to indicate appropriate surveillance in suspected individuals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00432-020-03391-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hereditary colorectal cancer, Revised Bethesda guideline, Nonsyndromic, NGS, SNP

Introduction

Approximately 30% of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) have a family history of CRC and could potentially be included in the broad spectrum of hereditary colorectal cancer (HCRC) (Kanth et al. 2017); however, only 5–7% of all CRCs are defined as well-established Mendelian inherited disorders, so-called syndromic HCRC (sHCRC). Accordingly, more than 80% of HCRC may be categorized as non-syndromic HCRC (nsHCRC), which has no particular associated symptoms/signs or well-established genotype–phenotype correlations. One study, involving 1006 familial CRC cases with early-onset (≤ 55 years at diagnosis), identified highly penetrant rare gene mutations in 16% of them (Chubb et al. 2016). Unfortunately, efficient screening methods and accurate information about risk factors for nsHCRC have been lacking, hence cases will presumably have been assumed to have multigenic causes.

The Bethesda guidelines (BG) and revised guidelines (RBG) are primarily intended to identify patients with HNPCC who require analysis of microsatellite instability (MSI) (Umar et al. 2004). As we cannot neglect the possibility of nsHCRC in cases that satisfy the RBG criteria, without MSI, the relationships of item-specific phenotypes with possible heredity warrants investigation. Discovery of genes related to nsHCRC pathogenesis using integrative and accurate genomic investigations will be crucial in enabling personalized diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance.

In this study, we implemented genetic analyses of patients stratified according to the RBG criteria plus additional items (12 items) and assessed their genotype–phenotype correlations with the aim of defining possible subtypes of nsHCRC, including microsatellite-stable (MSS) groups. Further, specific germline alterations were analyzed to identify candidate variants associated with specific phenotypes.

Materials and methods

Patient enrollment, sample acquisition, and study design

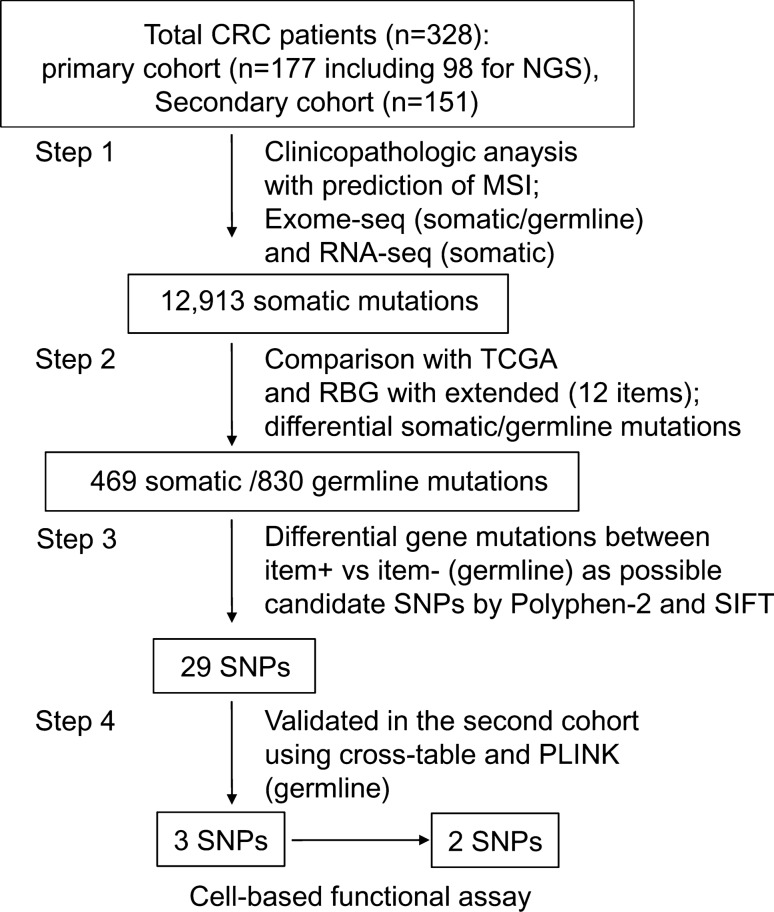

A total of 249 patients with sporadic CRC treated at Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) were enrolled during two periods (2008–2013 and 2014–2018), and consisted of 92 patients (31.8%) that satisfied the RBG criteria (RBG + group) and 157 (63.1%) that did not (RBG− group). All patients were classified according to 12 items, consisting of the five RBG items and seven additional criteria possibly predicting heredity (Table 1). A summary of comparative clinicopathological features is presented in Table A1. Blood and tissue samples of 98 patients enrolled during the first study period were used as a training set for next generation sequencing (NGS) assays. Samples from 151 patients enrolled during the second period were grouped as a validation set to confirm identified germline mutations. We used CRC tissue samples containing approximately > 90% tumor cells under triplicate histological reviews, their normal colonic epithelium (> 5 cm from the tumor border) and lymphocyte samples. Patients diagnosed with canonical sHCRC were excluded from the current study. Patient data and family history were collected using a structured medical-record review and questionnaire data from the two closest relatives from both the paternal and maternal lines, and they included the following: family history of cancer, relationships, age at diagnosis, cancer type and stage, and treatment details. A summarized schema of the current study design is presented in Fig. 1. All patients provided voluntary written formal consent including sample acquisition, and the study protocol, which conformed strictly to the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (registration numbers: 2019-1367).

Table 1.

The five items of the revised Bethesda guideline (RBG) and additional items

| Items | Annotations |

|---|---|

| RBG item 1 | CRC cancer diagnosed in a patient who is less than 50 years of age |

| RBG item 2 | Presence of synchronous, metachronous colorectal, or other HNPCC-related tumorsa, regardless of age |

| RBG item 3 | CRC with the MSI-H histology† diagnosed in a patient who is less than 60 years of age |

| RBG item 4 | CRC diagnosed in one or more first-degree relatives with an HNPCC-related tumora, with one of the cancers being diagnosed under age 50 years |

| RBG item 5 | CRC diagnosed in two or more first- or second-degree relatives with HNPCC-related tumorsa, regardless of age |

| Additional item 6 | CRC diagnosed in one first- or second-degree relatives with HNPCC-related tumorsb, regardless of age |

| Additional item 7 | Positive for MSH-H and negative for MSI-L or MSS on a Bethesda 5-panel analysis |

| Additional item 8 | Colorectal cancer patients with family history of CRC in their first or second relatives |

| Additional item 9 | Colorectal cancer patients with family history of GC in their first or second relatives |

| Additional item 10 | MLH1 promoter methylation and MSI immunostaining to the item 7 |

| Additional item 11 | CRC occurring at the right colon vs left colon |

| Additional item 12 | CRC occurring the colon vs rectum |

aHNPCC-related tumors include colorectal, endometrial, stomach, ovarian, pancreas, ureter and renal pelvis, biliary tract, and brain (usually glioblastoma as seen in Turcot syndrome) tumors, sebaceous gland adenomas and keratoacanthomas in Muir–Torre syndrome, and carcinoma of the small bowel

bPresence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, Crohn’s-like lymphocytic reaction, mucinous/signet-ring differentiation, or medullary growth pattern

RBG revised Bethesda guideline, HNPCC hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, MSI-H microsatellite instability in high frequency, MSI-L microsatellite instability in low frequency, MSS microsatellite in stable, CRC colorectal cancer, GC gastric cancer

Fig. 1.

A summary schema, outlining the four-step process applied in this study with sequential outcomes. CRC colorectal cancer, MSI microsatellite instability, TCGA the cancer genome atlas, RBG revised Bethesda guideline (Arakawa et al. 2018)

NGS, gene screening, and pathway enrichment analysis

DNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Library kit (Seq Cap EZ Exome v.3.0 Kit) and whole exome sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to generate 100 bp paired-end reads. The overall variant calling process was based on GATK best practice (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/best-practices, GATK v. 3.8). For the filtering variants, SNVs were filtered at VQSR truth sensitivity (TS) 99.5% and indels at VQSR TS 99.0%, following GATK documentation. Qualimap2 (v.2.2.1) was used to verify read coverage with mapping quality (https://bitbucket.org/kokonech/qualimap), attached in Table A2. Variants with too low read depth (< 10) were filtered out. Variant annotation database were using Snpsift (v.4.3) and dbSNP (v.138) databases. The R-package, deconstruct Sigs (v1.8.0), was used to apply a multiple regression approach to statistically quantify the contribution of mutational signatures for each tumor. Mutational signatures were obtained from the COSMIC mutational signature database (v.2; https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/signatures). Only non-synonymous somatic mutations were used to obtain mutational signatures. Weights were then combined, and the association between mutational signatures and clinical data, or the RBG items and extended criteria for each patient was analyzed. Detailed procedures, including variant calling and mutational signature with gene set analyses, are described in Table A3a.

RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina), and sequencing was conducted using the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Sequenced reads were mapped to the human genome (hg19) using STAR (v.2.5.1), and gene expression levels were quantified using the count module in STAR. The edgeR (v.3.12.1) package was used to select differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq count data. Meanwhile, trimmed mean of M-values normalization counts per million values for each gene were floored to 1 and log2-transformed for further analysis.

MSI and hMLH1 promoter methylation

Tumor MSI status was verified based on the Bethesda panel (BAT25, BAT26, D5S346, D2S123, and D17S250) using an ABI PRISM 310 DNA Sequencer and GeneScan 3.1 software (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and hMLH1 promoter methylation was assayed using DNA samples treated with sodium bisulfite (Zymo Research, Orange, CA, USA) (Tables A3b and c).

Genotype analysis of 29 differential gene mutations

Deleterious or damaging single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (n = 29) were selected from the initial screening experiment, based on analyses using PolyPhen-2(https://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), Clinvar (https://www.clinicalgenome.org/) and SIFT4G (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/sift4g/). These 25 SNPs were subjected to validation by pyrosequencing of samples from 151 patients in the second cohort using PSQ 96MA (version 2.0.2, Biotage), for the purpose of accuracy improvement of the NGS data as recommended (Del Vecchio et al. 2017).

Colorectal cancer cell-based assays

Cell-based functional assays included proliferation, invasion/migration, apoptosis and autophagy, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Among the ten CRC cell lines, CRC cell lines with minimal mRNA expression for specific molecules were selected for gene transfection or knockdown. Both wild- and mutant-type cDNAs of three genes, i.e., SH2D4A, KRTAP27-1, and NUP160, were amplified by PCR and subcloned into DDK-tagged pCMV6-entry for stable transfection (OriGene, Rockville, MD, USA). For knock-down, human-specific shRNAs (Dharmacon/Seoulin Bioscience, Hwaseong-sh, Korea) were transfected into cells using RNAiMax transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cell proliferation rate was measured using a cell proliferation assay kit (CCK-8) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Dojindo Corporation, Japan). Cell invasion and migration were assessed by uing a BD Biocoat™ Matrigel Invasion Chamber (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and a Transwell (24-well insert, 8 μm pore size; Corning, ME, USA), respectively. Otherwise, DNA content frequency was measured on a flow cytometry and immunoblottings. Autophagy was assessed by the electromobility of LC3 proteins from LC3-I to LC3-II and Beclin-1 expression, while epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) was simply evaluated for cadherin switch and expression of vimentin. Details of cell-based analyses including immunoassays were described in Table A3c and d.

Statistical analysis

Adequate sample number was determined using a difference in odds ratio for RBG frequency of 35% as the standard difference, with statistical power set at 80% likelihood of discrimination using the RBG. Clinicopathological features were appropriately compared using Fisher’s exact test with two-sided verification and cross-tabulation analysis with Pearson’s χ2 test, unpaired Student’s t-test, or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in gene mutation and mRNA expression levels between the two groups for each item were evaluated using Mann–Whitney U-test. Candidate germline mutations were verified by association analysis using PLINK (version 1.07, https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink) or cross-tabulation analysis with Pearson’s χ2 test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 software (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

General characteristics of somatic mutations

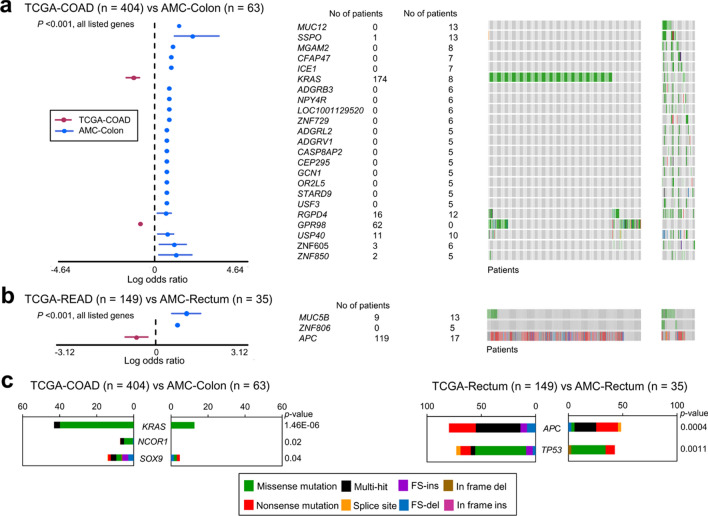

Compared with data from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which includes 12,913 genes mutated in CRC, few genes were as differentially mutated between the two cohorts, showing 172/11,618 (1.5%) genes of colon cancer and 14/1,687 (0.8%) genes of rectal cancer identified (Table A4a and b, Fig. 2a, b). Particularly, rates of CRC driver gene mutations in KRAS and APC were remarkably greater in TCGA cohort colon and rectal cancer data, respectively, than those in our patients (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2c). In the current study, significant differences in somatic mutation rates between the respective item + and item− groups were identified for 469 genes (Table A5, Fig. A1a and b). Among these genes differentially mutated according to the 12 items, 102 genes, corresponding to ten items (excluding items 5 and 9) also exhibited significantly different mRNA expression of their mutated forms between the item + and item− groups, with 73 genes underexpressed and 29 overexpressed, exclusive of driver gene mutations (Table 2). Mutation rates of relevant genes were exclusively higher in the item + than the item- group for the first ten items, except that FAT4 had a higher mutation rate in the negative group of item 1 (early-onset CRC, ≤ 50 years). Otherwise, the positive groups for items 11 (left colon cancer) and 12 (rectal cancer) showed higher mutation rates of 20 and three genes, respectively, than their respective negative groups, except for SYNE1 in item 11.

Fig. 2.

Highly significant (p < 0.001) gene mutations (forest plots) and various mutation patterns (oncoplots) between TCGA and AMC cohorts in colon cancer (a, COAD vs. colon) and rectal cancer (b, READ vs. rectum). Significant driver gene mutations differing between the two cohorts (c). TCGA the cancer genome atlas, COAD colon adenocarcinoma, READ rectal adenocarcinoma, FS frame-shift, ins insertion, del deletion

Table 2.

The five items of the revised Bethesda guideline (RBG) and additional items

| Relevant genes in respective itema | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11c | 12d |

| FAT4b |

EPHA3 HELZ2 MEGF8 SI SPTA1 UNC79 |

BMPR2 DST ERBB4 FAT1 FAT4 KDM5A MUC16 UBR5 |

BMPR2 MSH3 |

SETD5 |

ANKS1A BMPR2 CNOT1 DNHD1 DST FAT1 FAT4 FREM2 HELZ2 HSPG2 INO80 KDM5A LRRC7 MEGF8 MGA MSH3 MUC12 MUC16 PCNT RAI1 REV3L RIMS2 SCAF4 SEC31A SLC8A1 SYNE1 TTN USP40 ZC3H13 |

DNAH3 HELZ2 MUC16 PCDH17 SCAF4 SLC8A1 |

ANKS1A BMPR2 CNOT1 DNHD1 DST FAT1 FREM2 HELZ2 HSPG2 INO80 KDM5A LRRC7 MEGF8 MSH3 MUC16 PCNT RAI1 REV3L RIMS2 SCAF4 SEC31A SLC8A1 SYNE1 USP40 VPS13C ZC3H13 |

ANKS1A C2orf16 CACNA1D CDH1 CDH10 CNOT DCLK1 DGKH HCFC1 PCDH19 PRDM2 PTPRQ RAI1 RBBP8 SI SYNE1 TOP2B TRIO USP40 VPS13C XPOT |

HCFC1 HSPG2 USP40 |

Underscored genes indicated higher mutation rate with increased mRNA expression in the positive group compared with the negative group

aAll items are precisely defined in the Table 1

bExceptionally showing lower mutation rate in the positive group

cPositive group = left colon cancer, negative group = right colon cancer

dPositive group = rectal cancer, negative group = colon cancer

MSI- or DMMR-related somatic mutations

Tumor MSI rates were 18.9% in patients satisfying the RBG criteria and 17.1% in those satisfying the additional RBG criteria. Among genes with significantly increased mutation rates in patients meeting the criteria in items 7 and 10, ten (i.e., FAT1, FAT4, INO80, LRRC7, MUC16, PCNT, RAI1, REV3L, RIMS2, and TTN) also exhibited mRNA overexpression in tumors (Table 2). Other CRC-associated items (2, 3, and 8) shared differential mutations in common with 33–75% of those for items 7 and 10.

Gastric cancer-related somatic mutations

Item 9 was associated with a significantly higher mutation rate in the two genes, COL6A5 and MGAM2, which did not exhibit differential mRNA expressions in tumors (Fig. A1b). COL6A5 mutation was also higher in the positive group of item 10. As more than two-thirds of item 6 was concerned with family history of GC, the higher SETD5 mutation rate with mRNA overexpression observed in this group may be associated with CRC accompanying GC (Table 2).

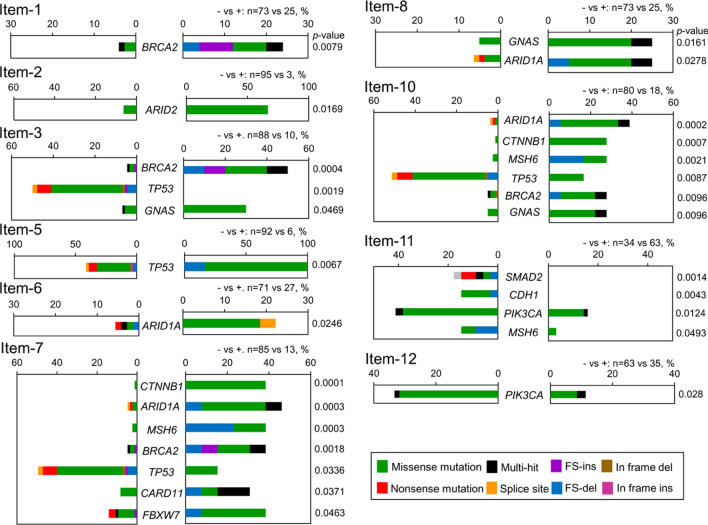

Driver gene mutation in analyzed items

A total of 27 driver gene mutations in 12 driver genes were mutated at significantly higher rates in the item + than the item− groups for each item, except for items 11 and 12. Four driver gene mutations (ARID2, MSH6, SMAD2, and CDH1) also showed mRNA overexpression in the item + group. The TP53 mutation rate was significantly higher in the negative groups of items 3, 7, and 10 (Fig. 3), while higher BRCA2 mutation rates were strongly associated with the positive groups of items 1, 3, 7, and 10.

Fig. 3.

Driver gene mutations by the 12 driver genes showed higher mutation rates in the item + group than the item− group of each item, except for items 4 and 9. All items are precisely defined in the Table 1. FS, frame-shift; ins, insertion; del, deletion

Candidate SNPs as possible markers to predict nsHCRC

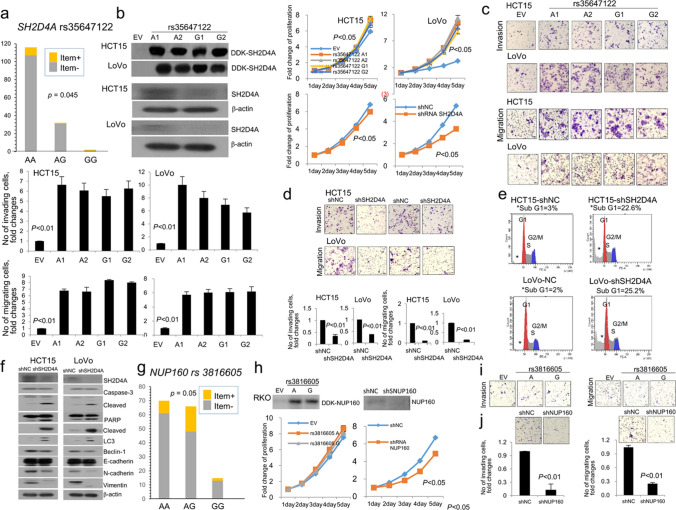

A total of 830 genes showed significantly higher rates of germline mutations in the positive groups of the items (Table A6). These were further selected according to mutations confined to open reading frames excluding synonymous ones. A total of 25 candidate SNPs were selected based on prediction that they were deleterious or damaging, including 17 associated with RBG items and eight with extended items (Table 3). These SNPs were consistently identified in both somatic and germline samples. Indels were exclusively identified in introns of relevant genes. Finally, three SNPs were chosen by the validation in another set of 151 patients with CRC. Items 2 was significantly associated with SH2D4A rs35647122 (p = 0.045), whereas the other two SNPs showed a trend of correlations with items 4 and 9 (KRTAP27-1 rs244485 and NUP160 rs3816605, respectively: both p = 0.05).

Table 3.

Pathogenic SNPsa associated with the revised Bethesda guide line and extended in the training cohort

| Itemsa | Gene | SNP ID | Position: nucleotide change | Predicted AA change |

Genotype: control vs case, RR/RS/SS | p-value | MAF | Clinical relevance PP-2/SIFT/ClinVar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Globalb | ||||||||

| 1 | MUC16 | rs112439001 | NM_024690.2:c.40730G > A | p.Ser13577Asn | 59/11/0 vs 12/13/0 | 0.0009127 | 0.126 | 0.0455 | NA/D/NA |

| 2 | SH2D4A | rs35647122 | NM_001174159.1:c.626A > G | p.Glu209Gly | 69/14/0 vs 0/3/0 | 0.0008036 | 0.198 | 0.0359 | D/D/NA |

| 2 | OR5A2 | rs17153691 | NM_001001954.1:c.307 T > C | p.Phe103Leu | 77/14/0 vs 0/3/0 | 0.0003774 | 0.181 | 0.0449 | D/T/NA |

| 2 | MMP27 | rs2509010 | NM_022122.2:c.1339G > A | p.Asp447Asn | 81/12/1 vs 1/1/1 | 0.0002847 | 0.155 | 0.1637 | D/NA/NA |

| 2 | KRT76 | rs2280480 | NM_015848.4:c.1886C > T | p.Thr629Met | 68/20/3 vs 0/1/2 | 7.311e-06 | 0.277 | 0.1659 | D/D/NA |

| 2 | DLGAP5 | rs8010791 | NM_014750.4:c.972A > C | p.Gln324His | 82/8/0 vs 1/1/1 | 3.261e-06 | 0.108 | 0.1176 | D/D/NA |

| 2 | KAZN | rs12048768 | NM_201628.2:c.2287C > T | p.Arg763Cys | 68/11/1 vs 1/1/1 | 0.0006443 | 0.096 | 0.0513 | NA/D/NA |

| 2 | ELMO3 | rs79736950 | NM_024712.3:c.1084C > T | p.Arg362Trp | 73/7/1 vs 0/3/0 | 3.315e-05 | 0.071 | 0.0118 | NA/D/NA |

| 2 | CENPT | rs11558533 | NM_025082.3:c.364A > G | p.Arg122Gly | 66/15/1 vs 0/2/1 | 3.846e-05 | 0.124 | 0.0258 | NA/D/NA |

| 3 | TAS2R4 | rs2234000 | NM_016944.1:c.221C > T | p.Thr74Met | 78/8/1 vs 5/4/1 | 0.0001884 | 0.144 | 0.0068 | D/NA/NA |

| 4 | WARS2 | rs3790549 | NM_201263.2:c.165G > C | p.Ala267Pro | 71/15/1 vs 3/6/1 | 0.0001327 | 0.237 | 0.0968 | D/NA/NA |

| 4 | KRTAP27-1 | rs2244485 | NM_001077711.1:c.296C > T | p.Ala99Val | 64/21/1 vs 2/6/1 | 0.0006876 | 0.305 | 0.3213 | D/NA/NA |

| 4 | SIGLEC12 | rs74354979 | NM_053003.2:c.229G > A | p.Ala77Thr | 71/9/0 vs 5/3/1 | 0.0009324 | 0.079 | 0.096 | NA/D/NA |

| 5 | ERICH3 | rs2305549 | NM_001002912.4:c.2072A > G | p.His691Arg | 67/21/3 vs 1/3/2 | 0.0001236 | 0.316 | 0.1176 | D/NA/NA |

| 5 | ZNF366 | rs13188519 | NM_152625.2:c.2216C > G | p.Ala739Glu | 78/7/0 vs 3/1/1 | 0.0005157 | 0.1 | 0.0725 | D/NA/NA |

| 5 | CCDC122 | rs9567280 | NM_144974.4:c.806 T > C | p.Ile269Thr, | 77/9/1 vs 3/2/1 | 0.0008882 | 0.14 | 0.0619 | D/D/NA |

| 5 | GOLGB1 | rs35674179 | NM_004487.4:c.5138G > T | p.Cys1718Phe | 84/6/0 vs 3/2/1 | 5.938e-06 | 0.052 | 0.1218 | NA/D/NA |

| 7 | THSD7A | rs2285744 | NM_015204.2:c.2313C > G | p.Asp771Glu | 60/16/0 vs 1/10/2 | 7.679e-05 | 0.169 | 0.721 | D/D/NA |

| 7 | CTBP2 | rs146419230 | NM_022802.2:c.2897C > G | p.Ala966Gly | 65/11/0 vs 3/7/0 | 1.370 e-04 | 0.105 | 0.9999 | NA/D/NA |

| 7 | MS4A14 | rs7131283 | NM_032597.4:c.529A > T | p.Asn177Tyr | 27/42/14 vs 1/4/8 | 0.0009599 | 0.468 | 0.6493 | D/D/NA |

| 8 | FSCN3 | rs3779536 | NM_020369.2:c.70G > T | p.Ala24Ser | 62/9/0 vs 10/7/1 | 0.0009094 | 0.191 | 0.1106 | D/D/NA |

| 9 | CCDC122 | rs9567280 | NM_144974.4:c.806 T > C | p.Ile269Thr, | 67/7/0 vs 13/4 2 | 0.0009795 | 0.14 | 0.0619 | D/D/NA |

| 9 | NUP160 | rs3816605 | NM_015231.2:c.1051A > G | p.Thr351Ala | 26/36/12 vs 16/3/1 | 0.0009383 | 0.346 | 0.3458 | NA/D/NA |

| 10 | THSD7A | rs2285744 | NM_015204.2:c.2313C > G | p.Asp771Glu | 60/16/0 vs 6/10/2 | 7.679e-05 | 0.1456 | 0.2788 | D/D/NA |

| 12 | ANKK1 | rs7118900 | NM_178510.1:c.715G > A | p.Ala239Thr | 6/13/10 vs 25/22/3 | 0.000323 | 0.386 | 0.2533 | NA/D/NA |

SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, AA amino acid, SS two substitution alleles, SR one reference and one substitution alleles, RR two reference alleles, MAF minor allele frequency, D damaging in the PP-2 and deleterious in the SIFT, respectively, NA not available, CRC family history of colorectal cancer, GC family history of gastric cancer, DMMR deficiency in mismatch repair genes

aAll items are precisely defined in the Supplementary Table S1

bGlobal allele frequency according to the dbSNP provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/)

cPossible to probable pathogenic SNPs based on the PolyPhen-2 (Polymorphism Phenotyping v2; https://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), SIFT (Sorting Intolerant from tolerant; https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) and ClinVar (https://www.clinicalgenome.org/). Any of these three tools suggesting benign or likely benign were excluded from the clinical significance

SH2D4A overexpression enhanced cell proliferation and invasion/migration, inhibiting apoptosis. Otherwise, SH2D4A underexpression increased autophagic LC3 and E-cadherin expression, concurrently showing reduced N-cadherin and vimentin expressions (Fig. 4a–g). NUP160 underexpression suppressed proliferation and invasion/migration (Fig. 4h, i). However, these biological behaviors were not significantly different between identified SNPs of SH2D4A and NUP160. KRTAP27-1 did not show any significant changes in cell-based assays.

Fig. 4.

Respective SH2D4A rs35647122 genotypes in a validation cohort (a): immunoblottings and proliferation in transfected clones of HCT15 and LoVo cells (b); invasion and migration in overexpressed (c) and underexpressed cells (d); flow cytometry identifying increased sub-G1 of apoptotic cells in underexpressed cells (e); immunoblottings of apoptosis-, autophagy-, and epithelial mesenchymal transition-related molecules (f). Respective NUP160 rs3816605 genotypes in a validation cohort (g): immunoblottings and proliferation in transfected clones of RKO cells (h); invasion and migration in overexpressed and underexpressed cells (i). KRTAP27-1 rs2244485 did not show any changes in cell-based assays and thus omitted in this illustration. A1, A2, A3, and A4 represent clones transfected with respective SNPs; sh short hairpin, NC negative control, EV empty vector

Discussion

Item 1 of the RBG essentially describes early-onset cancer, which is generally accepted as a hallmark of inherited cancer predisposition (Pearlman et al. 2017). Patients who meet the item 2 criteria may have strong evidence of cancer heritability, for example, as determined by a twin study (Lichtenstein et al. 2000). The histological characteristics defined in item 3 are proven to correlate with MSI or deficient mismatch repair (DMMR) (Jenkins et al. 2007). Items 4 to 10 may be suspected or categorized as concerning the broad spectrum of HCRC, including gastric cancer (GC). Item 11, defined by right vs. left colon cancer, and item 12, by colon vs. rectal cancer, were included to verify the reported trend for a high frequency of chromosomal instability (CIN) in left CRC in contrast to susceptibility to MSI associated with right CRC, and increased levels of non-hypermutation in rectal, compared with colon, cancer (The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2012; Hause et al. 2016). The overall MSI rates were ≤ 20% in our RBG and RBG/additional groups, which is in the lower range, relative to previous reports (16–47%) (Arakawa et al. 2018). Therefore, in approximately 80% of patients satisfying the RBG criteria, pathways other than MSI were likely responsible for the cancer with item-specific phenotypes.

Any patient with nsHCRC may harbor multiple low penetrance variants that potentially increase the risk of late-onset CRC (Talseth-Palmer et al. 2016). We initially identified significantly different mutation rates of 469 genes between the item+ and item− groups of the RBG/extended criteria. Mutations resulting from MSI appear to drive oncogenesis by inactivating TSG. The 13 MSI-related gene mutations identified in our study correspond to cancer-specific MSI, according to a previous study using TCGA cohort data (n = 5930) (Hause et al. 2016). It is currently unknown whether the remaining 17 genes contribute to the cause or consequence of MSI or DMMR. Among overexpressed mutated genes associated with MSI or DMMR, inactivation of TSG, such as FAT1 and FAT4, leads to Wnt/β-catenin signaling and regulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β pathways, respectively (Wei et al. 2019). The other gene mutation, in MUC16, identified as associated with mRNA overexpression, is often classified as one of the top three frequently mutated genes facilitating proliferation and invasion of cancer cells (Aithal et al. 2018). Further, TTN mutation may be associated with CRC carcinogenesis, as a recent study identified TTN to be a candidate gene predisposing to classic PTEN-wildtype Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome including hamartomatous polyposis (Yehia and Eng 2017).

Few ethnic differences related to gene mutations and rates were identified in TCGA cohort data and our patient data. Exceptionally, mutation rates of two driver genes, KRAS and APC, were remarkably greater in colon and rectal cancers, respectively, in TCGA cohort data compared with those from our patients. These two genes play determinant roles in the initial step of adenoma–carcinoma transition (Cappell 2018). Our findings suggest somewhat fewer APC pathway-associated cases among our patients with CRC, consistent with previous investigations reporting lower frequencies of BRAF, KRAS, and APC mutations in Asians relative to Caucasians and Africans (Yoon et al. 2015; Ling et al. 2015).

As potential novel gene mutations associated with left colon cancer, 21 genes associated with item 11 showed higher mutation rates in left than right colon cancer, potentially different to be discriminative. Among these 21 genes, CDH1 and DCLK1 are known to mediate the epithelial–mesenchymal transition, probably via Wnt signaling, which is implicated in the control of various stem cells (Daulagala et al. 2019; Park et al. 2019). Further, TCGA study revealed that rectal and colon cancers are indistinguishable based on somatic copy number variation and mRNA/microRNA expression analyses (The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2012); however, we identified three genes (USP40, HCFC1, and HSPG2) that exhibit higher mutation rates in rectal cancer compared with colon cancer. USP40 is MSI-cancer specific and exhibits ubiquitin-specific protease activity, thereby inhibiting CASP8 activation and degradation of CFLARL (Hause et al. 2016; An et al. 2019). Thus, higher mutation rates of USP40 may indicate that this is a rare MSI gene, given the relatively low MSI incidence in rectal cancer (3%) (Hause et al. 2016). HCFC1 is characterized by THAP11-dependent gene expression, and a complex of these proteins may be important for the regulation of transcription and cell growth in CRC (Parker et al. 2012). Moreover, HSPG2 participates in diverse extracellular matrix scaffolding functions and is associated with various tumors, including CRC (Kalscheuer et al. 2019). The finding that FAT4 mutation was decreased in the item 1 + group, while it was increased in items 3 and 7, is novel. We speculate that decreased FAT4 mutation in the item 1 + group may indicate early-onset MSS CRC or relatively later-onset CRC.

Although the incidence of synchronous or metachronous GC in patients with CRC is generally reported to be higher in patients with HNPCC than in controls, controversial issues remain concerning the relationship between CRC and GC in the presence of significantly different GC incidence, depending on ethnicity and geographic region (Gylling et al. 2007). In our study, two novel mutations in the genes COL6A5 and MGAM2 were associated with item 9, while mutation of COL6A5 was also associated with item 10. MGAM2 mutation has been identified in human cancers related to carbohydrate metabolic pathways (https://www.genecards.org). COL6A5, a member of the collagen family, has been reported to carry somatic mutations in breast and esophageal cancer; however, it has not previously been associated with CRC, and may exert its effects via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and p53 pathways (Li et al. 2019). Additionally, SETD5 showed an increased mutation rate and mRNA overexpression in the item 6 positive group, which was significantly correlated with item 9 in our study. SETD5 displays histone methyltransferase activity and histone acetylation during gene transcription (Osipovich et al. 2016). SETD5 can be considered a common genetic alteration in GC and CRC, and is probably unrelated to MSI or DMMR, along with COL6A5 and MGAM2 mutations.

Driver genes have roles in genome maintenance or cell survival and fate, conferring a selective growth advantage (Vogelstein et al. 2018). Driver mutation rates were generally higher in the positive than in the negative groups, except for TP53, which exhibited the reverse correlation with items 7 and 11. These findings implicate TP53 mutations in the MSS phenotype, consistent with a previous study (Loree et al. 2018). We found higher levels of BRCA2 mutations to be closely related to early-onset and MSI-related CRCs, consistent with a previous study reporting a strong association of MSI CRCs with BRCA2 mutation (Gokare et al. 2017). Another NGS study, involving 450 patients with early-onset CRC (< 50 years old), identified germline mutations of BRCA1/2, regardless of family history of breast or ovarian cancers (Pearlman et al. 2017). Mutation rates of the three driver genes, SMAD2, CDH1, and PIK3CA, were significantly higher in right colon or colon cancers, compared with left colon cancer or rectal cancer, respectively in our study. CDH1, encoding E-cadherin, is also considered as TSG in the colon, primarily via dysregulation of Wnt signaling, which is a predominant driver of colonic tumorigenesis, particularly in right colon cancer (Daulagala et al. 2019). Right colon cancer is associated with susceptibility to MSI and is frequently accompanied by aberrant activation of the EGFR pathway, involving increased mutation of the two oncogenes, BRAF and PIK3CA, compared with those of the left colon and rectal cancers (Loree et al. 2018). No correlation of SMAD2 mutation with specific CRC location has yet been identified; however, it may be related to the TGF-β growth inhibitory pathway, which influences the down-stream effector proteins, SMAD2/3 (Troncone et al. 2018).

We identified three novel germline SNPs associated with specific RBG/extended criteria items, which may be implicated in specific types of CRC carcinogenesis. Although putative candidate missense variants are challenging, in terms of determining their pathogenic impact, the potential relevance of missense variants in functionally important domains cannot be underestimated (de Voer et al. 2016). Otherwise, highly deleterious mutations are likely to be subject to negative selection (Sham and Purcell 2014). Among the three SNPs identified in our study, SH2D4A rs35647122 was associated with synchronous and metachronous CRC, or CRC-related, cancers. The tumor suppressor function of SH2D4A has exclusively been investigated in liver cancer and cirrhosis via two pathways; however, no associations with this gene have previously been identified in CC (Ploeger et al. 2016). Conversely in our study, SH2D4A appeared to promote oncogenic progression in HCT15 and LoVo CRC cells. The other SNP, NUP160 rs3816605, showed a trend of correlation with GC pedigree. NUP160 is poorly studied; however, there is one report confirming an oncogenic effect of NUP160-SLC43A3-expressing fibroblasts (Shimozono et al. 2015). Similar oncogenic property was identified in our CRC cells. Another SNP, KRTAP27-1 rs2244485, appeared to be correlated with an attenuated form of HNPCC, but its oncogenic implication is presently unexplained. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome, a rare type of HNPCC, includes CRC, hematologic, and central nervous system malignancies during childhood presenting café-au-lait spot associated with epidermal histogenesis of keratin (Kanth 2017). Altered keratin expression in carcinogenesis is presently reported to modulate signaling pathways involved in tumor progression (Dmello et al. 2019). However, these three SNPs did not show any difference between their wild and mutant alleles. Another oncogenic function or an effect of mixed alleles to some degree may eliminate or reduce delicate differences of biological behavior in our cell-based assays.

Our study has several limitations influencing the strength of the conclusions that can be reached based on our data. First, we likely omitted a fair number of somatic and germline mutations, which we did not consider because of our primary focus on defining presently uncharacterized genotype–phenotype correlations, regardless of MSI. Second, given the limited size of the positive patient groups for some items (e.g., items 2 and 5) in our NGS cohort, we may have failed to detect important gene mutations associated with these phenotypes. Third, the observed discrepancies between mutation rates, mRNA expression levels, and alterations in introns or untranslated regions require further investigation to clarify their roles in CRC carcinogenesis; specifically, these occurred in approximately one-third of item-specific differential gene mutations.

Conclusion

Our study may be a novel one to define potential relationships between genetic alterations and possible nsHCRC in terms of the well-characterized RBG/additional items; previous studies have been confined to MSI-associated CRCs. In particular, specific gene mutations associated with left colon or rectal cancers and accompanied by GC appear to warrant further validation, which should consider their presently unidentified genomic pathogenesis, respectively. Although we could not identify any high penetrant germline mutations, three SNPs, i.e., SH2D4A rs35647122, NUP160 rs3816605, and KRTAP27-1 rs244485, potentially affect synchronous and metachronous CRC, CRC associated with GC, and lesser-strict criteria of HNPCC, respectively. Our limited genomic analysis for RBG and additional items suggests that particular somatic alterations in the respective item may provide item-specific pathogenesis of CRC along with germline mutations, and further appropriate surveillances. The approach adopted here appears to be a method for defining presently unknown nsHCRC, and further studies including sufficient numbers of subjects and functional validation of untranslated regions and introns may strengthen our findings.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Fig. A1. Oncoplots of significant gene mutations between the respective item+ and item- groups of 12 items (a. items 1-8 , b. items 9-12). All differential genes of respective items presented p < 0.05, except for items 7 and 10 (p < 0.001) (XLSX 3669 kb)

Funding

This study was cooperatively supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2020R1C11009345, 2017R1A2B1009062, and 2016R1E1A1A02919844) grants funded by the Korea government (NSIT).

Data availability

Raw sequence tags were deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra), under the accession number SRP199998. RNA-seq data sets were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession number GSE132024.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (registration no.: 2019-1367).

Informed consent

All samples were collected from the Institutional Bioresource Center, with written consent from patients [registration no. 2015-08(98)].

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jin Cheon Kim and Jong Hwan Kim have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jin Cheon Kim, Email: jckim@amc.seoul.kr.

Seon-Young Kim, Email: kimsy@kribb.re.kr.

References

- Aithal A, Rauth S, Kshirsagar P, Shah A, Lakshmanan I, Junker WM, Jain M, Ponnusamy MP, Batra SK (2018) MUC16 as a novel target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 22(8):675–686. 10.1080/14728222.2018.1498845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An W, Yao S, Sun X, Hou Z, Lin Y, Su L, Liu X (2019) Glucocorticoid modulatory element-binding protein 1 (GMEB1) interacts with the de-ubiquitinase USP40 to stabilize CFLARL and inhibit apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38(1):181. 10.1186/s13046-019-1182-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa K, Hata K, Kawai K, Tanaka T, Nishikawa T, Sasaki K, Shuno Y, Kaneko M, Hiyoshi M, Emoto S, Murono K, Nozawa H (2018) Predictors for high microsatellite instability in patients with colorectal cancer fulfilling the revised Bethesda guidelines. Anticancer Res. 38(8):4871–4876. 10.21873/anticanres.12800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell MS (2008) Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of colon cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 37(1):1–24. 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb D, Broderick P, Dobbins SE, Frampton M, Kinnersley B, Penegar S, Price A, Ma YP, Sherborne AL, Palles C, Timofeeva MN, Bishop DT, Dunlop MG, Tomlinson I, Houlston RS (2016) Rare disruptive mutations and their contribution to the heritable risk of colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 22(7):11883. 10.1038/ncomms11883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daulagala AC, Bridges MC, Kourtidis A (2019) E-cadherin beyond structure: a signaling hub in colon homeostasis and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 20(11):2756. 10.3390/ijms20112756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Voer RM, Hahn MM, Weren RD, Mensenkamp AR, Gilissen C, van Zelst-Stams WA, Spruijt L, Kets CM, Zhang J, Venselaar H, Vreede L, Schubert N, Tychon M, Derks R, Schackert HK, Geurts van Kessel A, Hoogerbrugge N, Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP (2016) Identification of novel candidate genes for early-onset colorectal cancer susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 12(2):e1005880. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio F, Mastroiaco V, Di Marco A, Compagnoni C, Capece D, Zazzeroni F, Capalbo C, Alesse E, Tessitore A (2017) Next-generation sequencing: recent applications to the analysis of colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 15(1):246. 10.1186/s12967-017-1353-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmello C, Srivastava SS, Tiwari R, Chaudhari PR, Sawant S, Vaidya MM (2019) Multifaceted role of keratins in epithelial cell differentiation and transformation. J Biosci 44(2):33. 10.1007/s12038-019-9864-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokare P, Lulla AR, El-Deiry WS (2017) MMR-deficiency and BRCA2/EGFR/NTRK mutations. Aging (Albany NY) 9(8):1849–1850. 10.18632/aging.101275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gylling A, Abdel-Rahman WM, Juhola M, Nuorva K, Hautala E, Järvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Aarnio M, Peltomäki P (2007) Is gastric cancer part of the tumour spectrum of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer? A molecular genetic study. Gut 56(7):926–933. 10.1136/gut.2006.114876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hause RJ, Pritchard CC, Shendure J, Salipante SJ (2016) Classification and characterization of microsatellite instability across 18 cancer types. Nat Med. 22(11):1342–1350. 10.1038/nm.4191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins MA, Hayashi S, O'Shea AM, Burgart LJ, Smyrk TC, Shimizu D, Waring PM, Ruszkiewicz AR, Pollett AF, Redston M, Barker MA, Baron JA, Casey GR, Dowty JG, Giles GG, Limburg P, Newcomb P, Young JP, Walsh MD, Thibodeau SN, Lindor NM, Lemarchand L, Gallinger S, Haile RW, Potter JD, Hopper JL, Jass JR, Colon Cancer Family Registry (2007) Pathology features in Bethesda guidelines predict colorectal cancer microsatellite instability: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 133(1):48–56. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalscheuer S, Khanna V, Kim H, Li S, Sachdev D, DeCarlo A, Yang D, Panyam J (2019) Discovery of HSPG2 (Perlecan) as a therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 9(1):12492. 10.1038/s41598-019-48993-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanth P, Grimmett J, Champine M, Burt R, Samadder NJ (2017) Hereditary colorectal polyposis and cancer syndromes: a primer on diagnosis and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 112:1509–1525. 10.1038/ajg.2017.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang X, Zheng K, Liu Y, Li J, Wang S, Liu K, Song X, Li N, Xie S, Wang S (2019) The clinical significance of collagen family gene expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Peer J. 7:e7705. 10.7717/peerj.7705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K (2000) Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer—analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 343(2):78–85. 10.1056/nejm200007133430201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling C, Wang L, Wang Z, Xu L, Sun L, Li WD, Wang K (2015) A pathway-centric survey of somatic mutations in Chinese patients with colorectal carcinomas. PLoS ONE 10(1):e0116753. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loree JM, Pereira AAL, Lam M, Willauer AN, Raghav K, Dasari A, Morris VK, Advani S, Menter DG, Eng C, Shaw K, Broaddus R, Routbort MJ, Liu Y, Morris JS, Luthra R, Meric-Bernstam F, Overman MJ, Maru D, Kopetz S (2018) Classifying colorectal cancer by tumor location rather than sidedness highlights a continuum in mutation profiles and consensus molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 24(5):1062–1072. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipovich AB, Gangula R, Vianna PG, Magnuson MA (2016) Setd5 is essential for mammalian development and the co-transcriptional regulation of histone acetylation. Development 143(24):4595–4607. 10.1242/dev.141465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Kim JY, Choi JH, Kim JH, Lee CJ, Singh P, Sarkar S, Baek JH, Nam JS (2019) Inhibition of LEF1-mediated DCLK1 by niclosamides attenuates colorectal cancer stemness. Clin Cancer Res. 25(4):1415–1429. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-18-1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JB, Palchaudhuri S, Yin H, Wei J, Chakravarti D (2012) A transcriptional regulatory role of the THAP11-HCF-1 complex in colon cancer cell function. Mol Cell Biol. 32(9):1654–1670. 10.1128/mcb.06033-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, Zhao W, Yilmaz A, Miller K, Bacher J, Bigley C, Nelsen L, Goodfellow PJ, Goldberg RM, Paskett E, Shields PG, Freudenheim JL, Stanich PP, Lattimer I, Arnold M, Liyanarachchi S, Kalady M, Heald B, Greenwood C, Paquette I, Prues M, Draper DJ, Lindeman C, Kuebler JP, Reynolds K, Brell JM, Shaper AA, Mahesh S, Buie N, Weeman K, Shine K, Haut M, Edwards J, Bastola S, Wickham K, Khanduja KS, Zacks R, Pritchard CC, Shirts BH, Jacobson A, Allen B, de la Chapelle A, Hampel H, Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative Study Group (2017) Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 3(4):464–471. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeger C, Waldburger N, Fraas A, Goeppert B, Pusch S, Breuhahn K, Wang XW, Schirmacher P, Roessler S (2016) Chromosome 8p tumor suppressor genes SH2D4A and SORBS3 cooperate to inhibit interleukin-6 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 64(3):828–842. 10.1002/hep.28684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham PC, Purcell SM (2014) Statistical power and significance testing in large-scale genetic studies. Nat Rev Genet. 15(5):335–346. 10.1038/nrg3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimozono N, Jinnin M, Masuzawa M, Masuzawa M, Wang Z, Hirano A, Tomizawa Y, Etoh-Kira T, Kajihara I, Harada M, Fukushima S, Ihn H, Shimozono N et al (2015) NUP160-SLC43A3 is a novel recurrent fusion oncogene in angiosarcoma. Cancer Res. 75(21):4458–4465. 10.1158/0008-5472 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Talseth-Palmer BA, Bauer DC, Sjursen W, Evans TJ, McPhillips M, Proietto A, Otton G, Spigelman AD, Scott RJ (2016) Targeted next-generation sequencing of 22 mismatch repair genes identifies Lynch syndrome families. Cancer Med. 5(5):929–941. 10.1002/cam4.628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012) Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487(7407):330–337. 10.1038/nature11252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troncone E, Marafini I, Stolfi C, Monteleone G (2018) Transforming growth factor-β1/smad7 in intestinal immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Front Immunol. 9:1407. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Rüschoff J, Fishel R, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Hamelin R, Hamilton SR, Hiatt RA, Jass J, Lindblom A, Lynch HT, Peltomaki P, Ramsey SD, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Vasen HF, Hawk ET, Barrett JC, Freedman AN, Srivastava S (2004) Revised Bethesda guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 96(4):261–268. 10.1093/jnci/djh034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW (2013) Cancer genome landscapes. Science 339(6127):1546–1558. 10.1126/science.1235122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R, Xiao Y, Song Y, Yuan H, Luo J, Xu W (2019) FAT4 regulates the EMT and autophagy in colorectal cancer cells in part via the PI3K-AKT signaling axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38(1):112. 10.1186/s13046-019-1043-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehia L, Ni Y, Eng Cs (2017) Germline TTN variants are enriched in PTEN-wildtype Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. NPJ Genom Med. 2:37. 10.1038/s41525-017-0039-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HH, Shi Q, Alberts SR, Goldberg RM, Thibodeau SN, Sargent DJ, Sinicrope FA (2015) Racial differences in BRAF/KRAS mutation rates and survival in stage III colon cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 107(10):djv186. 10.1093/jnci/djv186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. A1. Oncoplots of significant gene mutations between the respective item+ and item- groups of 12 items (a. items 1-8 , b. items 9-12). All differential genes of respective items presented p < 0.05, except for items 7 and 10 (p < 0.001) (XLSX 3669 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequence tags were deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra), under the accession number SRP199998. RNA-seq data sets were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession number GSE132024.