Abstract

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by T cell‐mediated pancreatic β cell loss, resulting in lifelong absolute insulin deficiency and hyperglycaemia. Environmental factors are recognized as a key contributor to the development of T1D, with the gut serving as a primary interface for environmental stimuli. Recent studies have revealed that the alterations in the intestinal microenvironment profoundly affect host immune responses, contributing to the aetiology and pathogenesis of T1D. However, the dominant intestinal immune cells and the underlying mechanisms remain incompletely elucidated. In this review, we provide an overview of the possible mechanisms of the intestinal mucosal system that underpin the pathogenesis of T1D, shedding light on the roles of both non‐classical and classical immune cells in T1D. Our goal is to gain insights into how modulating these immune components may hold potential implications for T1D prevention and provide novel perspectives for immune‐mediated therapy.

Keywords: gut‐pancreas axis, intestinal mucosal immunity, microbiota, type 1 diabetes, unconventional T cell

1. INTRODUCTION

T1D is an autoimmune disease driven by an innate, adaptive immune dysregulation resulting in insulin‐producing pancreatic β cell destruction. Although genetic predisposition and environmental factors are involved in the pathogenesis of T1D, evidence from increasing incidence rates, 1 immigrant studies 2 and twin studies 3 suggest that environmental factors seem to play a more significant role in triggering the disease onset and progression. Accumulating evidence highlights the significant role of environmental factors in the development of T1D. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 When specific external factors, such as microbiota, viral exposure and dietary influences, interact with individuals with a genetic susceptibility, they trigger a cascade of autoimmune reactions mediated by lymphocytes. This process leads to targeted destruction and functional impairment of islet β cells, progressively dampening insulin secretion, ultimately resulting in diabetes.

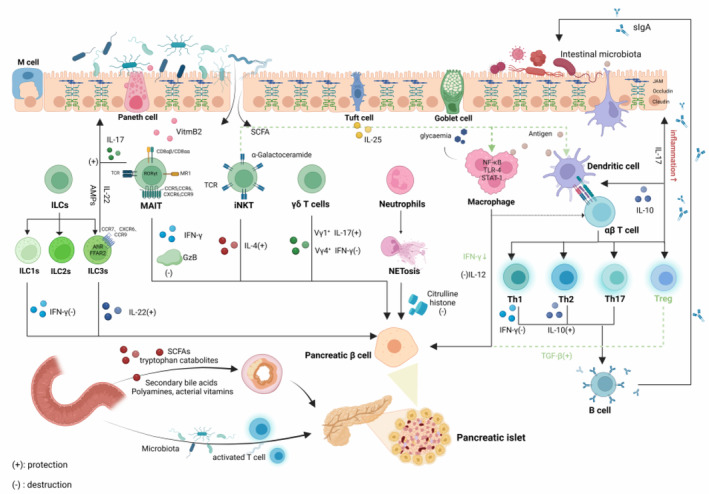

In addition to direct islet destruction, the pathogenesis of T1D is also driven by responses in extra‐islet tissues and organs. Outi Vaarala et al. 8 emphasized the significance of intestinal microbiota, intestinal barrier function and mucosal immune interactions in driving T1D pathogenesis. The intestinal microbiota and epithelial barrier engage in a complex dialogue to maintain homeostasis. Perturbations deriving from foods, physical conditions, chemical substances, as well as changes in gut microbiota, can potentially alter this equilibrium. 9 Detrimental environmental exposure and genetic defects may disrupt tolerance and intestinal homeostasis, leading to increased intestinal barrier permeability and consequently impacting host immunity and contributing to chronic inflammatory or autoimmune diseases. Studies have demonstrated that gut commensal microbiota aberrantly activated tissue‐specific pathogenetic T cells, and subsequently evoked autoimmune attack in extra‐intestinal tissues. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 For example, dietary short‐chain fatty acids (SCFAs) ameliorate autoimmune encephalomyelitis via expanding intestinal lamina‐propria‐derived T regulatory cells (Tregs) by suppression of the JNK1 and p38 pathway. 14 Impaired gut barrier integrity can activate islet‐specific T cells within the intestinal mucosa, leading to autoimmune diabetes, characterized by an increase in T cells expressing gut homing marker α4β7 integrin in the pancreatic lymph nodes (PLN) and islets. 15 However, a direct causal link between enteropathy and triggering of islet β cell autoimmunity has yet to be established. This review will provide a basic overview of the intestinal microenvironment, with an emphasis on how non‐classical immune cells affect the pathogenesis of T1D. We also discuss the therapeutic implications of targeting intestine immunity to reduce the activation of islet‐specific T cells in the gut to prevent T1D occurrence (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Implication of the communication between gut and pancreas in the aetiology of type 1 diabetes. Created in BioRender.com.

2. INTESTINAL MICROENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS IN T1D

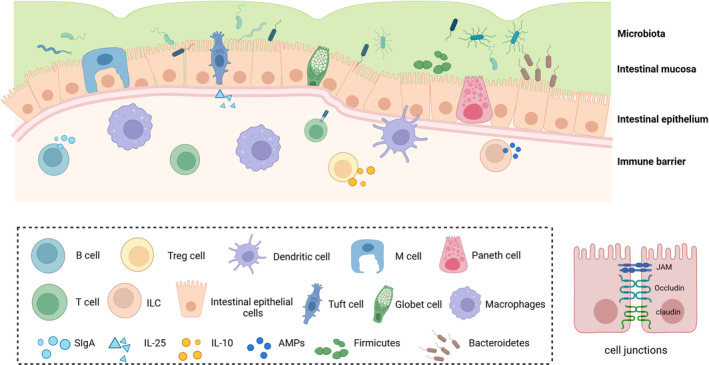

The intestinal microenvironment is composed of normal gut microbiota, the intestinal barrier and its surrounding environment. The intestinal barrier, comprising the intestinal immune system, epithelium, mucus layer and microbiota, exhibits selective permeability to limit microbial exposure while facilitating efficient absorption of water and nutrients. 16 Preclinical and clinical models of T1D have demonstrated impaired intestinal epithelial barrier, disrupted mucus layer, increased gut permeability and microbiota dysbiosis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of T1D (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The gut microbiota, gut barrier, and their surrounding environment together form the intestinal microenvironment. Created in BioRender.com.

2.1. Intestinal epithelium

The intestinal epithelium, composed of a single layer of cells, plays a pivotal role in maintaining gut homeostasis and serves as both a physical barrier and a coordinating hub for immune defence and crosstalk between bacteria and immune cells. These cells encompass enterocytes, various secretory cells such as goblets cells, enteroendocrine cells and Paneth cells, along with the chemosensory tuft cells and M cells. 17 Enterocytes are the most predominant cell type of the intestinal epithelium, responsible for nutrient and water absorption. Upon encountering bacteria or their products, these cells can elaborate a range of chemokines and cytokines to recruit and/or activate neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells. Their local immune response capacity is related to intestinal mucosa damage and intestinal barrier infections. 17 Goblet cells secrete mucin 2, 18 a highly O‐glycosylated protein that forms a gel and organizes the thick mucus layer covering the large intestinal epithelium. Paneth cells, absent in the large intestine, produce antimicrobial molecules such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and Reg3 family proteins to impede bacterial infiltration into the crypt. M cells are essential for the uptake and eventual presentation of luminal antigens to the immune system. 19 Chemosensory tuft cells release the cytokine interleukin‐25 (IL‐25), promoting intestinal mucosal T helper 2 (Th2) immune responses. These responses facilitate tissue repair and parasite expulsion but can also cause inflammatory diseases like asthma and allergies. 17 , 20 Additionally, the intestinal epithelium can hamper microbiota invasion through cell junctions, including tight junction and adhesion junction. A tight junction consists of claudins, occludins and intracellular zonula occludens (ZO) proteins. Research has shown that feeding non‐obese diabetic (NOD) mice with an anti‐inflammatory diet high in soluble fibre inulin and ω‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can prevent T1D. This diet helps restore the integrity of gut barrier resulting in thicker mucus layer layers, higher mRNA transcripts of structural mucin (Muc2) and immunoregulatory mucins (Muc1 and Muc3), as well as of tight junction proteins (Claudin1). 21 Meanwhile, T1D patients exhibited impaired intestinal permeability even before the clinical onset of T1D. 22

2.2. Intestinal mucosa

The mucus layer coats the entire gastrointestinal tract. It acts as the initial interface of contact for commensal bacteria before they interact with the host. This forms a crucial barrier against microbial invasion. Apart from serving as a physical barrier to prevent bacterial translocation, the mucus layer is composed of a complex network of molecules, including mucins and AMPs, which exert critical immune regulatory and anti‐microbial functions, modulating the host‐microbe interface and maintaining homeostasis. In NOD mice with early‐stage insulitis, the intestinal mucus layer exhibited compromised structure and phosphatidylcholine lipid composition. 23 A recent cross‐sectional study has revealed a decrease in mucosal mucins (MUC2, MUC12, MUC13, MUC15, MUC20 and MUC21) and AMP mRNA expression in human T1D patients, which is related to the reduced relative abundance of intestinal microbiota producing SCFAs. 24 Moreover, secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) is involved in mucus‐associated commensal colonization and exclusion. T‐dependent immunoglobulin G (IgG) also regulates host‐microbiota crosstalk at the mucosal border. 25 Studies have shown that SCFAs are beneficial for promoting the growth of intestinal epithelial cells and strengthening intestinal tight junctions in T1D. 26 We reiterate that dietary modulation is a crucial adjunctive therapeutic strategy for the management of T1D.

2.3. Microbiota

It is widely accepted that the gut is sterile before birth and subsequently colonized by microorganisms during delivery through vertical transmission in the birth canal. 27 Furthermore, infants can modulate their microbiota composition through breastfeeding. 28 Moreover, the gut microbiota can regulate the secretion of host defence factors such as AMPs and sIgA, thereby autonomously regulating its ecosystem. 29 In a healthy gut, strictly anaerobic bacteria predominantly belonging to Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes constitute the majority of the gut microbiota. Specifically, certain oxygen‐tolerant Firmicutes and Proteobacteria dominate in the small intestine. 30

In children with T1D, the progression to autoimmune diabetes is associated with an altered composition and diversity of the intestinal microbial colonies, a decreased abundance of Firmicutes compared to Bacteroidetes and a reduction in butyrate‐producing bacteria subgroups. 31 , 32 In Streptozotocin‐induced T1D mice, commensal microbiota translocated from the intestinal tract to PLNs, then activated NOD2 receptors in myeloid cells and drove the differentiation of pathogenic Th1 and Th17 cells, further promoting the development of T1D. 33 Antibiotics‐induced dysbiosis can restore the intestinal permeability of B‐cell‐specific T lymphocyte‐like receptor (TLR) 9‐deficient NOD mice. Notably, studies have demonstrated that alterations in the intestinal microbiota, characterized by an enrichment of Lachnospiraceae, are associated with an upregulation of IL‐10 expression in regulatory B cells, which in turn, leads to a delay in the onset of diabetes. 34 The lack of myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) in specific pathogen‐free NOD mice has been demonstrated to prevent the onset of diabetes. In contrast, germ‐free MyD88‐negative NOD mice can develop robust diabetes, indicating that the protective effect of mucosal immunity disappears and is abolished in the absence of microbiota. 35 A population‐based cross‐sectional study revealed that 12 taxa were uniquely altered in adult‐onset T1D patients, with a notable enrichment of Bacteroidetes. 36 The US Food and Drug Administration has recently approved teplizumab, a T cell‐specific anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody, for T1D treatment. Teplizumab promotes operational tolerance in T1D and prevent the expansion of autoreactive T cells to protect against T1D, 37 increase endogenous insulin production, reduce insulin dosage and improve the lifestyle of patients. 38 Notably, clinical trials have demonstrated that the treatment efficacy of teplizumab is positively correlated with the magnitude of IgG2 responses against Bifidobacterium longum and Enterococcus faecalis in the gut. 39 The gut‐pancreatic axis is an important pathway for the intestinal mucosal immune system to affect the onset of T1D. The role of gut microbiota in the mucosal immune system cannot be ignored, and changes in microbiota composition and abundance can affect the progression of T1D.

3. THE ROLE OF INTESTINAL MUCOSAL IMMUNE SYSTEM IN T1D

Aberrant activation of the intestinal immune system can lead to the generation of tissue‐specific autoreactive lymphocytes, which in turn triggers a series of non‐intestinal autoimmune diseases, such as T1D, 15 autoimmune uveitis 9 and rheumatoid arthritis‐related lung pathology. 40 Mucosal lymphocytes are characterized by the expression of integrin α4β7 and chemokine receptor CCR9, which bind to the endothelial adhesion molecule MAdCAM‐1 and chemokine CCL25, respectively. 12 Mia Westerholm‐Ormio et al. discovered significant immune activation in the small intestine through clinical studies conducted on children with T1D. 41 , 42 This was evidenced by an increase in the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II antigens and intercellular adhesion molecules‐1, as well as enhanced antigen presentation ability. Additionally, there was an upregulation of islet gut‐associated homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9, indicating the existence of a gut‐pancreas axis and potential migration of intestinal T cells to the pancreas. 43 , 44 CCR9 can be expressed in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD127− Treg cells and is required for T cell homing to the small intestine. 45 Consequently, it can be postulated that defects in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD127− Treg cells production within the intestinal mucosa may disrupt the balance between Teff/Treg cells in PLNs and islets, thereby promoting T1D development. The increase of IL‐4 and IL‐18 mRNA expression in small intestinal mucosa observed in children with T1D is primarily mediated by intestinal macrophages, 43 further supporting aberrant activation of the intestinal immune system in T1D pathogenesis. Thus, modulating intestinal mucosal immunity emerges as a promising therapeutic strategy for restoring immune homeostasis and protecting T1D development.

Intestinal mucosal immunity is divided into innate and adaptive immunity. There is reciprocal crosstalk between intestinal epithelial cells and adaptive immune cells, and the crosstalk may exhibit an essential effect on intestinal mucosal immunity. 46 Intestinal adaptive immunity plays a critical role in maintaining immune tolerance towards symbionts and in preserving intestinal barrier integrity. Meanwhile, the innate immune system regulates the adaptive immune responses to intestinal commensal bacteria, which mainly includes intraepithelial lymphocytes as well as epithelial and lamina propria lymphoid cells. 47 , 48 Next, we will elucidate the relationship between the intestinal mucosal immune system and T1D in two parts: non‐classical immune cells and classical immune cells.

3.1. Features of non‐classical immune cells

Unconventional T cells, including γδ T cells, invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells and mucosal‐associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, are restricted by monomorphic MHC class Ib molecules. These cells express a semi‐invariant T cell receptor (TCR) that limits their antigenic range in a manner similar to an innate immune receptor. Thus, they are also called innate‐like T cells. 49 , 50 They all share the ability to massively secrete a wide range of cytokines rapidly in a TCR‐dependent or TCR‐independent manner. Such rapid responses allow these cells to bridge innate and adaptive immune responses. Their high conservatism of evolution makes these ‘innate’ T cells appealing targets for developing one‐size‐fits‐all immunotherapies. 51 In addition, a study has shown that innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) play an essential role in intestinal mucosal immunity and T1D pathogenesis. 47

3.1.1. γδ T cells

T cells are divided into αβ T cells and γδ T cells according to TCR. In comparison to the conventional αβ T cells, γδ T cells exhibit numerous unique innate immune system properties. These include highly diverse TCR expression, lack of MHC restriction and independence from processing and presentation by antigen‐presenting cells, which enables them to respond rapidly to pathogen‐associated molecular patterns and cytokines in absence of TCR ligands. 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 They are predominantly present in epithelial tissues, with a particularly high abundance observed in the intestinal tract. 18 In healthy adult humans, they constitute 1%–10% of the total circulating lymphocytes and are predominantly characterized by a CD4/CD8 double‐negative phenotype. 55

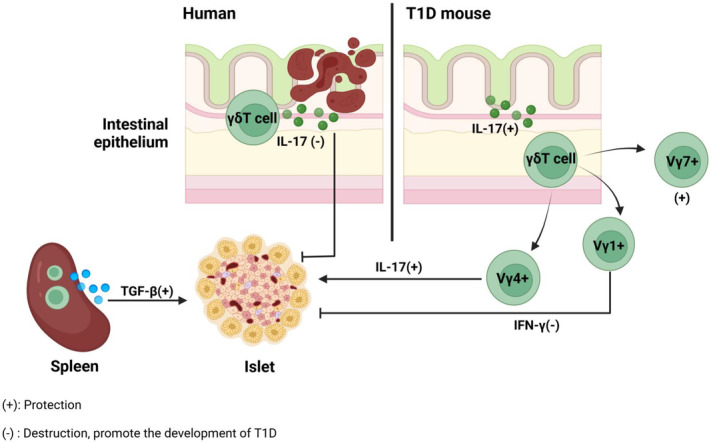

γδ T cells have been identified as the major initial IL‐17 producers in mouse models of autoimmune diseases. IL‐17 maintains epithelial barrier integrity, but overactive Th17 cell reaction promotes inflammation. Some studies investigating the involvement of γδ T cells in the pathogenesis of T1D have been inconsistent and contradictory. In human T1D, IL‐17 mucosal immunity is activated and plays a role in destroying islet β cells. In NOD mice, spleen γδ T cells exhibit a protective effect 56 , 57 , 58 by preventing diabetes in a transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) dependent manner. 58 However, a subsequent study revealed that γδ T cells can also be detrimental to NOD diabetes. 59 In fact, γδ T cells can be classified into distinct subtypes based on the Vγ gene, 60 , 61 exhibiting diverse metabolic phenotypes and functional features. 62 , 63 NOD Vγ4+ γδ T cells impede T1D progression via IL‐17 production and/or CD4+ αβ T cells (Tregs) development. 64 While the vast majority of γδ T cells in the draining lymph nodes in the pancreas and spleen of NOD mice are Vγ1+ and these Vγ1+ cells, which have a bias to producing interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ), can promote diabetes development. 64 Furthermore, intraepithelial lymphocytes, specifically γδ T cells, in NOD mice showed significantly increased CD8α expression, particularly within the predominant colonic Vγ7+ subset. Studies indicate that insufficient numbers of gut CD8α+ Vγ7+ γδ T cells may contribute to accelerated diabetes development. 64 Thus, γδ T cells are implicated in T1D pathogenesis, with Vγ gene usage influencing disease outcome. Specifically, Vγ4+ and Vγ7+ γδ T cells exhibit protective effects, whereas Vγ1+ cells promote T1D development (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

γδ T cell. We compared the differences in the mechanisms of γδ T cell engagement in human T1D and NOD mice. In human T1D, intestinal inflammation leads to the activation of mucosal immunity, which in turn triggers IL‐17 to destroy islet β cells. Based on the Vγ gene, γδT cells in the intestinal mucosa of NOD mice are classified into Vγ4+, Vγ7+ γδT cells that protect against T1D, and Vγ1+ γδT cells that promote the development of T1D. γδT cells in the spleen secrete TGF‐β for the protection of T1D. Created in BioRender.com.

3.1.2. Invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT cells)

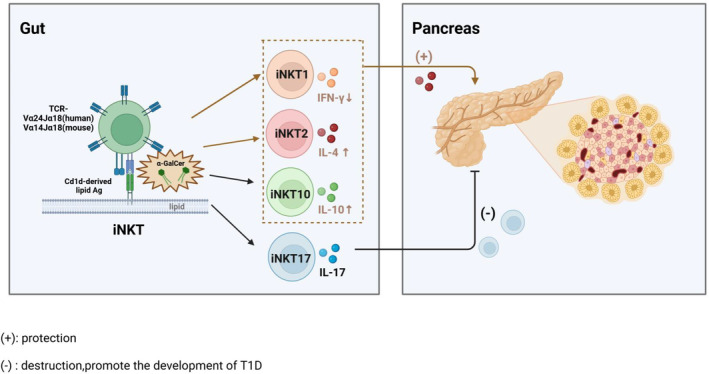

iNKT cells express a semi‐invariant TCR α chain namely Vα24‐Jα18 in humans, and Vα14‐Jα18 in mice, which specifically recognize lipid antigens like α‐galactosylceramide (α‐GalCer) presented by non‐polymorphic CD1d molecules. 65 , 66 The activation and function of iNKT cells can be modulated by the microbiota. 67 , 68 Several CD1d‐restricted antigens in bacteria and other microbes play a role in this modulation. For example, glycolipids from Chlamydia muridarum 69 and Helicobacter pylori, 70 as well as phospholipids from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette‐Guerin 71 and the parasite Leishmania donovani. 72 The nature of the iNKT cell response depends on the structure of the lipid antigen being recognized, thereby giving rise to distinct subsets of iNKT cells, namely iNKT1, iNKT2, iNKT10 and iNKT17 cells that exhibit differential cytokine production profiles (IFN‐γ, IL‐4, IL‐10 and IL‐17), which empowers iNKT cells with diverse functional capacities under various pathological backgrounds 73 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

iNKT. iNKT cells differentiate into distinct cell subsets upon recognition of lipid antigens. α‐GalCer offers protection against T1D by stimulating IL‐4 secretion and reducing IFN‐γ secretion by iNKT cells. iNKT17 cells secrete IL‐17 and migrate to the pancreas to facilitate the development of T1D. Created in BioRender.com.

Distinct subsets of iNKT cells exhibit either protective or detrimental roles in the pathogenesis of T1D. Numerical and functional iNKT cell defects have been identified in NOD mice and human. 74 , 75 , 76 Evidence from the accelerated development of T1D in Cd1‐deficient NOD mice 77 , 78 and α‐GalCer activation of iNKT cells preventing the onset of T1D 79 , 80 fully demonstrated the protective role of iNKT cells. A previous study demonstrated that α‐GalCer protection against spontaneous T1D is associated with a polarized Th2 environment, characterized by elevated IL‐4 and IL‐10 levels, as well as reduced IFN‐γ levels in the spleen and pancreas, along with increased IL‐10R transcription in the spleen. 79 However, subsequent research suggested that the protection mediated by α‐GalCer‐activated iNKT cells depends on IL‐4 rather than IL‐10. 81 Overall, the protective role of iNKT cells in T1D is well established, α‐GalCer relies on IL‐4 to promote iNKT cells to protect T1D progression in NOD mice. We suggest that insufficient IL‐4 secretion may contribute to the development of T1D, and replenishing IL‐4 levels may emerge as a crucial therapeutic strategy for T1D treatment.

iNKT cells have also been shown to promote anti‐virus response in virus‐induced T1D. In lymphochoriomeningitis virus‐induced T1D mice, iNKT cells induce tolerogenic plasmacytoid DCs, converting naive T cells into Treg cells in pancreatic drainage lymph nodes. Then Treg cells were recruited into the pancreatic islets, producing TGF‐β, suppressing the diabetogenic T cell responses in the pancreatic islets, and thereby preventing T1D. 82 Pancreatropic enterovirus Coxsackievirus B4 (CVB4) infection can accelerate T1D development in a subset of proinsulin 2–deficient NOD mice. Following CVB4 infection, α‐GalCer administration activates iNKT cells, leading to a rapid surge in IFN‐γ production. This IFN‐γ promotes indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase expression in islet‐infiltrating suppressive macrophages. Indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase subsequently modulates the activity of anti‐islet T cells, potentially leading to IFN‐γ‐mediated β cell destruction and ultimately preventing T1D onset. 83

However, not all iNKT cell subsets are protective. Research has revealed an elevated frequency and number of iNKT17 cells in PLNs of NOD mice, which exacerbates diabetes. 84 , 85 Additionally, the gut microbiota in NOD mice can facilitate the intestinal expansion of effective iNKT17 cells. The frequency of iNKT17 cells in NOD mice positively correlates with the relative abundance of Bacteroidales species and inversely correlates with Clostridiales strains. 68 These cells can migrate from gut mucosa to PLN and pancreas, thereby promoting T1D pathogenesis. 68

In contrast, data on human T1D are scarce and even contradictory. While a study reported reduced iNKT cells in T1D patients, 76 others have shown normal or even higher frequency in these individuals. 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 We propose that additional clinical studies in cohorts of T1D patients are requisite to elucidate its role. Nevertheless, functionally aberrant iNKT responses have been demonstrated in T1D patients. iNKT cells derived from T1D patients exhibited impaired compacity to secrete IL‐13, 75 which plays a crucial role in maintaining pancreatic β cell viability following exposure to various cytotoxic insults. 92 In fact, iNKT clones bearing high‐affinity iNKT‐TCRs demonstrated more robust proliferation and secreted increased amounts of cytokines in response to CD1d‐expressing antigen‐presenting cells. 93 Recent‐onset T1D patients have a selective loss of iNKT clones expressing high‐affinity TCRs in peripheral blood compared to matched healthy controls. 91 Overall, further investigation should focus on well‐defined cohort studies to explore the dynamic alteration in both frequencies and function of iNKT cells during the development of T1D. Given the robust advantages of α‐GalCer in activating iNKT cells, developing its analogues favouring IL‐13 production may be an effective strategy for enhancing iNKT function to prevent T1D.

3.1.3. Mucosal‐associated invariant T cells (MAIT cells)

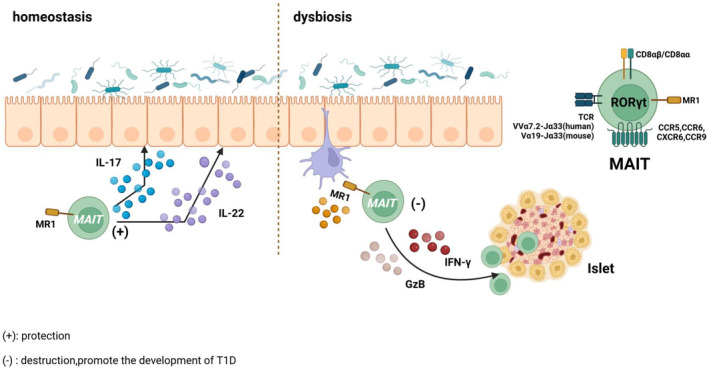

MAIT cells are an evolutionally conserved T cell subset, expressing a canonical and invariant TCRα chain (Vα7.2‐Jα33 in humans; Vα19‐Jα33 in mice). 94 MAIT cells, functionally similar to iNKT cells, which are restricted to highly conserved MHC‐I related molecular (MR1), can respond to most bacteria by recognition of vitamin B2 biosynthetic pathway. 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 Vitamin B2 metabolites produced by the microbiota control the thymic development of MAIT cells. 17 Then, MAIT cells traveled toward the mucosal barrier and lymphoid organs to maintain the homeostasis of the intestinal epithelial barrier. In humans, MAIT cell frequencies are very high in blood (1%–10% of T cells), liver (20%–40%), lung and gut lamina propria. MAIT cells can directly lyse bacterially sensitized and infected target cells 99 , 100 and produce the proinflammatory cytokines IFN‐γ, tumour necrosis factor α (TNF‐α) and IL‐17. 101 MAIT cells are generally CD8+ (~85%) with the remaining cells mainly being double negative (DN, CD4− and CD8−), although CD4+ and double positive (DP, CD4+ and CD8+) groups are frequently observable in scant amounts in healthy donors. 94

Studies have demonstrated that MAIT cells are implicated in multiple autoimmune diseases such as T1D, multiple sclerosis, 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 rheumatoid arthritis 106 , 107 , 108 and systemic lupus erythematosus. 109 , 110 Studies have observed sharply reduced frequency and number of MAIT cells in the fresh peripheral blood of children with newly diagnosed T1D and autoantibody‐positive at‐risk T1D individuals compared with the control group. 111 , 112 , 113 Specifically, in children with newly diagnosed T1D, circulating CD8− CD27− MAIT cells increased, coupled with a decrease CD8+ CD27+ MAIT cells. 113 Additionally, in adults with long‐term T1D, there was a slight reduction in circulating CD8+ MAIT cells compared with healthy controls. 114 These circulation MAIT cells also exhibited functional alterations, including an activated phenotype characterized by increased granzyme B (GzB) and cytokine production like TNF‐α, IL‐4, 111 upregulated CD25 and costimulatory marker CD27 114 as well as an exhausted phenotype marked by decreased homing receptor CCR6, 111 CCR5, β7 integrin 113 or anti‐apoptotic Bcl‐2 molecules, 111 upregulated programmed cell death 1. 114 This notion is supported by augmented MAIT cells with cytotoxic activity in pancreatic islets in NOD mice and their production of GzB and IFN‐γ, which could directly participate in islet β cell death. 111 In NOD mice, MAIT cells exhibited protective or detrimental phenotypes according to their tissue localization. 111 On one hand, in gut mucosa, MAIT cells sense microbiota and their metabolites and produce IL‐17 and IL‐22 to maintain gut mucosa integrity, two critical cytokines in intestinal homeostasis, but this protective effect is diminished during T1D progression. On the other hand, in the pancreas, the frequency of MAIT cells and their production of GzB and IFN‐γ increased with disease development in NOD mice. 111 Without MAIT cells, intestinal permeability was significantly increased, immune cell activation occurred, and diabetes worsened markedly in MR1−/− NOD mice. 111

Nevertheless, Kuric et al. questioned the presence of MAIT cells in islet lesions of recently diagnosed T1D patients. 115 Studies also implied that child‐onset T1D patients exhibited comparable frequency of circulating CD8+ MAIT cells and DN MAIT cells when compared to control individuals, with no significance with diabetic duration, autoantibody levels or HbA1c. 116 , 117 Conversely, another cohort of adults with recent‐onset T1D suggested that several MAIT cell variables such as CD56, Ki67, GzB and IL‐4 were associated with the level of HbA1c and the MAIT cell changes in adult T1D patients were related to impaired glucose homeostasis. 114 Notably, discrepancies in gating strategy for MAIT cells, as well as differences in age and human leukocyte antigen 113 background among study cohorts may account for some of these dissimilarities. In fact, in human insulitis, the number of infiltrating cells is relatively modest compared to the NOD mouse model, which features extensive lymphocyte infiltration, underscoring the difference between the mouse model and human disease. 118 , 119 Overall, MAIT cells are crucial in communicating between gut microbiota and the pancreas. Furthermore, altered MAIT cells were observed in both patients and mice prior to T1D onset, suggesting that the protective role of MAIT cells at the intestinal mucosal level in NOD mice may pave the way for the development of new therapeutic strategies based on their local triggering in this tissue early in disease progression. 111 In addition, folates (vitamin B9) 120 and riboflavin (vitamin B2) 121 are important for MR1/MAIT regulation, while riboflavin is not synthesized by humans, it is metabolized by microbiota. 121 More human cohort studies are needed to confirm the feasibility of dietary vitamin supplementation to protect against T1D (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

MAIT cell. In the homeostasis of NOD mice, MAIT cells migrate to the mucosal barrier and lymphoid organs to secrete IL‐17 and IL‐22 for maintaining the intestinal epithelial barrier. As T1D progresses, MAIT cells with cytotoxic activity migrate to the pancreas and secrete GzB and IFN‐γ to destroy islet β cells. Created in BioRender.com.

3.1.4. Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)

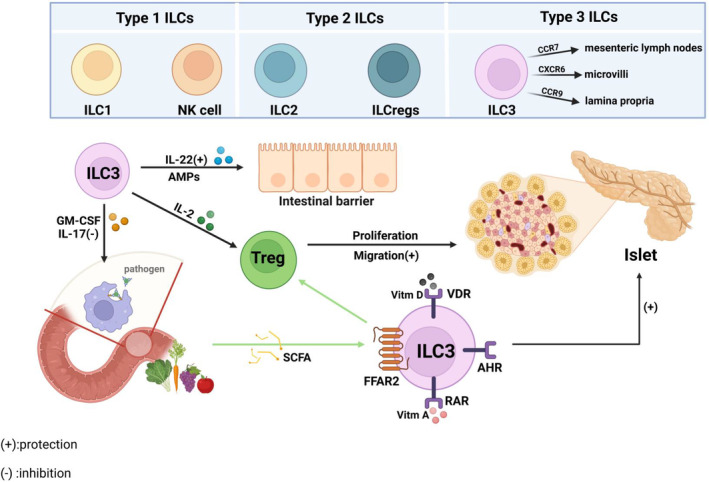

ILCs are crucial in immunity, tissue homeostasis and pathological inflammation and are enriched in mucosal sites. 12 ILCs are divided into three groups based on their phenotype and functional characteristics, all of which belong to the innate immune system. The group 1 ILCs include ILC1s and natural killer (NK) cells, which can produce IFN‐γ. 122 NK cells have a direct cytotoxic effect, and studies have shown that individuals with T1D exhibited impaired lytic activity in NK cells. 123 The group 2 ILCs including ILC2s are able to produce Th2 cell‐associated cytokines. 122 The group 3 ILCs primarily consist of ILC3s, which express different chemokine receptors and migrate to distinct regions of gut‐associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). Specifically, ILC3s expressing CCR7 migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes, CXCR6‐expressing ILC3s migrate to microvilli, and CCR9‐expressing ILC3s migrate to lamina propria. 124

ILC3s intricately orchestrate signals from metabolites in food and gut microbiota to regulate the immune response. The secretion of IL‐17 and Granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor prevents immune cell activation from pathogenic microorganisms. 125 In parallel, the secretion of IL‐22 and AMPs maintains intestinal barrier integrity. IL‐2 secretion promotes the stability and proliferation of intestinal Tregs, enabling their migration to PLNs where they regulate the autoimmune response by establishing an inhibitory microenvironment. 125 In the intestinal biopsy of T1D patients, a notable rise in ILC1s and a decline in IL‐2 and IL‐22‐producing ILC3s were observed, underscoring the plasticity of intestinal ILCs and T cells. 126 The inflammatory environment of GALT‐producing IFN‐γ transforms ILC3s into ILC1s. Thus, the impaired function of Tregs promotes the onset of T1D. The protective effects of IL2+ and IL‐22+ ILC3s in T1D NOD mice were also suggested. 125 , 126 ILC3s specifically regulate the target free fatty acid receptor (FFAR) 2 (also termed as G‐protein‐coupled receptor (GPR) 43), which mediates the production of IL‐22, but do not produce IFN‐γ, which can reduce the autoimmune response of islet β cells. 125 Experiments revealed that intestinal microbiota metabolites SCFAs (propionate and acetate), as the corresponding ligand of FFAR2 can induce Tregs to inhibit the occurrence and development of T1D. 125 In addition, ILC3s express the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) transcription factor, which is crucial for the development, proliferation and IL‐22 secretion in the intestinal lamina propria. Experiments have shown a reduced number of ILC3s in the intestine of AHR‐deficient mice, and AHR activation prevents T1D by either Tregs‐dependent or Tregs‐independent mechanisms. 127 Furthermore, ILC3s express receptors for retinoic acid and vitamin D that upon activation with respective vitamins instigate ILC3s proliferation and/or secretion of IL‐22. 125 Therefore, supplementation of corresponding vitamins can regulate ILC3s secretion to protect against T1D (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

ILCs. ILCs are divided into three groups based on their phenotype and functional characteristics. ILC3s secrete IL‐17 and GM‐CSF to prevent immune cells from being activated by pathogenic microorganisms, secrete IL‐22 and antimicrobial peptides to maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and secrete IL‐2 to promote the migration of intestinal Tregs to the PLN, thereby protecting against T1D. ILC3s recognize SCFA, inducing Treg cells to protect against T1D. Created in BioRender.com.

The high conservatism of unconventional T cell evolution renders them an attractive target for immunotherapy, such as strategies aimed at inhibiting IFN‐γ secretion by γδ T cells and promoting IL‐13 secretion by iNKT cells. However, the high conservatism of these cells also contributes to the disparities between mouse models and human diseases, thereby hindering the translation of basic research findings into clinical practice. Nevertheless, we remain optimistic about the potential of immunotherapy targeting unconventional T cells to yield significant breakthroughs.

3.2. Features of classical immune cells

The intestinal microbiota and the host immune system maintain homeostasis through intricate interactions at the mucosal interface, orchestrated by innate and adaptive immune responses. Perturbations in environmental exposures and genetic factors can disrupt this delicate balance of haemostasis and immune tolerance within the gut, ultimately contributing to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases 33 (Figure 7).

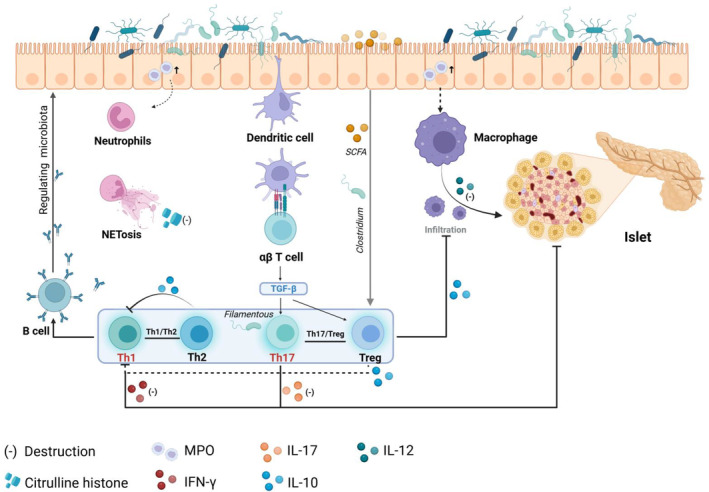

FIGURE 7.

Classical immune cell. Neutrophils and macrophages infiltrate the intestinal tract of NOD mice. NETs release citrulline histones and directly damage tissues, while macrophages secrete IL‐12 and induce gut‐derived Tc1 cells to migrate to the pancreas to promote the development of T1D. DCs present antigens to induce T cell differentiation, and the balance between Th17/Treg and Th1/Th2 is of great significance for protecting against T1D. In addition, T cells promote B cell activation and secretion of specific sIgA, shaping the gut microbiome and maintaining homeostasis. Created in BioRender.com.

3.2.1. Innate immune cells

Innate immune cells are strategically distributed at the host‐microbiome interface within the intestinal mucosa. They exhibit a remarkable ability to recognize and respond to various components or products derived from microorganisms, thereby initiating intricate signaling cascades that enable the host to sense conserved microbial elements through specialized receptors and subsequently trigger an orchestrated immune response. 128

Neutrophils and macrophages are crucial in mediating the pathogenesis of T1D. Research has demonstrated that alterations in intestinal permeability can contribute to intestinal inflammation, which is often observed in patients with T1D. 129 Hardin et al. discovered a significant increase in myeloperoxidase activity within the small intestine of both type 1 diabetic rats and bio‐breeding (BB) rats prone to developing T1D, accompanied by infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages. 130 , 131 Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), through the release of their intracellular contents, serve as an essential defence mechanism against pathogens. 42 The citrulline histones released by NETs serve as antigens in autoimmune reactions. 132 Dysfunctional NETs can directly damage tissues and contribute to the development of T1D. 42 Abnormal production of macrophage cytokines is a characteristic feature in NOD mice, with elevated levels of IL‐12 playing a pathological role in autoimmunity and guiding disease organ differentiation (high levels observed in T1D and low levels in lupus). 133 Macrophages are the first inflammatory immune cells infiltrating into pancreatic islets, which are essential for activating diabetogenic T cells. A study has found that T1D patients’ duodenal mucosa has an increased infiltration of monocyte/macrophage lineage compared with the normal control group. 134 Activated intestinal macrophages promote the homing of intestinal‐derived Tc1 cells to pancreas, further promoting the T1D progression in NOD mice. 135

Innate immunity serves as a prerequisite and initiating factor for adaptive immunity. Within the lamina propria of the intestinal mucosa, two primary populations of CD11c+ mononuclear phagocytes exist DCs and macrophages. DCs can be further categorized into three major subgroups based on their CD11b and CD103 expression: CD11b+CD103+, CD11b−CD103+ and CD11b−CD103−. These subsets can migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes through CCR7 signaling. 136 Disruption of the intestinal mucosal barrier can trigger an inflammatory response from the microbiome. Proinflammatory antigens are presented to DCs or macrophages, which then migrate to lymph nodes for presentation to T cells. This preferentially polarizes T cells towards Th1 or Th17 subgroups. 137 In NOD mice, GPR41 expression is abnormally reduced in the pancreas and colon, and GPR41 deficiency promotes DC maturation in mice, resulting in intestinal immune dysfunction and IFN‐γ T cell migration to the pancreas. 138 Intestinal inflammation triggers the infiltration of innate immune cells, which in turn stimulates T cell differentiation, culminating in a dysregulated autoimmune response that exacerbates the development of T1D.

3.2.2. Adaptive immune cells

Atarashi et al. demonstrated the capacity of Clostridium strain complex to induce Treg cells in the gut of mice. SCFAs have been closely associated with the proliferation of Treg cells. 128 , 139 Furthermore, Treg cells differentiate to produce IL‐10, which inhibits macrophage and DC functions while restricting Th1 immune responses, 140 thereby maintaining intestinal homeostasis.

The mucosal immunity of Th17 is in close proximity to the microbiota. The Th17 subgroup secrete IL‐17A, which is responsible for maintaining the epithelial barrier integrity, yet excessive Th17 activity can lead to inflammation. After treating NOD mice with anti‐CD20, the levels of Th17 cells and IL‐17A in the spleen and pancreas decreased, while the levels of Treg cells increased, delaying the progression of T1D in NOD mice. 141 In human T1D, activation of IL‐17 mucosal immunity plays a role in β cell destruction. 142 Both Th17 and Tregs exhibit significant plasticity and share a common signaling pathway mediated by TGF‐β. Under normal microbial conditions, the balance between Th17/Treg is maintained. However, dysregulation of microorganisms and invasion of intestinal mucosa by pathogens can promote pro‐inflammatory cytokine production by IECs, 86 thereby shifting the balance towards Th17 cells, 143 resulting in inflammation and the development of T1D. Therefore, maintaining Th17/Treg balance is an important target to inhibit the development of T1D, and more studies have been conducted to verify its feasibility. Human intestinal segmented Filamentous bacteria can induce Th17 cell differentiation. Depletion of Lactobacillus muris caused by salt consumption can contribute to Th17 disorders and autoimmune disorders, which may be alleviated through supplementation with Lactobacillus muris via non‐segmented filamentous bacteria mechanisms, 128 offering a potential treatment approach for T1D.

The Th1 immune response orchestrates tissue‐damaging inflammation and is characterized by the expression of T‐bet, IL‐12 and IFN‐γ, as well as phosphorylation and dimerization of signal transducers and transcription‐1 activators. 144 Th2 cells are pivotal in driving and regulating immune responses triggered by allergens and worm infections. 145 IL‐10 is an important cytokine secreted by Th2 cells and may have immunosuppressant activity and anti‐inflammatory effects, inhibiting the production and release of IL‐2, IFN‐γ and other pro‐inflammatory cytokines, and inhibiting Th1 cell proliferation and cytokine production, thereby rebalancing the Th1/Th2 subpopulation and protecting β cells in NOD mice. 146 Research has demonstrated that parasite infection can mitigate the development of T1D in NOD mice through downregulation of Th1 expression. 143 Lymphocytes in individuals with autoimmune diabetes exhibit impaired TCR‐mediated signaling, abnormal T cell activation and proliferation which may disrupt the balance between Th1/Th2 cytokine secretion patterns thereby promoting the onset of T1D. 147 Therefore, as with Th17/Treg, it is important to maintain a balance between Th1/Th2 secretion patterns, and it has been shown that parasites have a powerful ability to modulate mammalian immune responses and that their excretory/secretory products may be potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of T1D. 148

T cells facilitate the activation of B cells and secrete specific sIgA, which subsequently suppresses the expression of flagella‐related genes to modulate the microbiome, 137 thereby targeting the gut microbes. However, the mucosal sIgA response to microbiota lacks typical characteristics of a classical memory response. When there is a change in microbiota composition, intestinal plasma cells that generate sIgA clones may become inactive, allowing for an adaptive mucosal immune system response to accommodate the fluctuating microbiota, 149 thus maintaining tolerance towards variable intestinal microbiota. What is more, microbiota‐reactive IgA can also arise via T cell‐independent pathways. Without T cell help, T cell‐independent mechanisms of IgA induction in the intestinal lamina propria and isolated lymphoid follicles generate polyreactive and low‐affinity antibodies. 150 They shape the composition of the gut microbiome and enhance gut‐microbiome homeostasis.

Studies have shown that intestinal immune cells can also migrate under specific circumstances, such as intestinal infection and inflammatory stimulation, contributing to extraintestinal diseases. Since 70% of its blood supply comes from the portal vein, the liver is physiologically exposed to gut microbes and metabolites. 151 Research involving patients with concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis‐inflammatory bowel disease has clearly revealed a clonal correlation of T‐cell infiltration in both the gut and liver. 152 Dysregulation of microbiota associated with central nervous system autoimmunity, resulting in a selective decrease in propionate mediated GPR43 stimulation in mucosal lymphocytes, induces a shift of colonic T cells to a proinflammatory phenotype, and promotes the transit of these T cells from the colonic mucosa to the central nervous system autoimmunity. It can promote the development of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. 153

The mechanism by which gut microbiota and intestinal immune cells regulate T1D through the gut‐pancreas axis may be similar to the gut‐brain axis and gut‐liver axis. Adaptive immune cells play a crucial role in maintaining the stability of intestinal mucosal immunity by dynamically regulating the balance of cellular subpopulations and adapting to the fluctuating intestinal microbiota. The significance of this process cannot be ignored, as disruptions to adaptive immunity can precipitate autoimmune diseases, including T1D. Therefore, it is essential to further investigate the factors that regulate the intestinal mucosal immune system, with the goal of identifying potential therapeutic targets for the protentional prevention and treatment of T1D.

4. FACTORS THAT REGULATE INTESTINAL MUCOSAL IMMUNITY IN T1D

The gut mucosal immune system, which consists of lymph nodes, lamina propria and epithelial cells, forms a protective barrier safeguarding the integrity of the intestinal tract. The intestinal mucosa is exposed to various external antigens such as food antigens, food‐borne pathogens and commensal microbes in the intestinal lumen. 154

4.1. Gut microbiota

The gut microbiota is the largest symbiotic ecosystem with the host. It mainly regulates intestinal mucosal immunity through its metabolites, including intestinal microbiota‐derived metabolites, metabolites produced by gut bacteria from dietary components (SCFAs, tryptophan catabolites, trimethylamine‐N‐oxide), metabolites produced by the host and modified by gut bacteria (secondary bile acids) and metabolites synthesized de novo by gut bacteria (branched‐chain amino acids, polyamines, bacterial vitamins). 155 The gut microbiota produces a diverse array of receptors within the intestinal mucosal immune system, encompassing TLR, NOD‐like receptors, purinergic receptors, GPRs and AHR. 156 , 157 These receptors sense the microbiota and regulate the production of cytokines or chemokines. Specifically, NOD‐like receptor family pyrin domain‐containing 6 mediates activation of mucus secretion, AHR facilitates IL‐22 production, MyD88 regulates microbiome‐specific IgA secretion, TLR mediates AMP secretion and GPR‐mediated signally activates T cell. The lack of these innate immune receptors impairs pathogen defences and renders tissues susceptible to spontaneous inflammation. 157 Microbiota contributes to the stability of the intestinal mucosal barrier by influencing the expression and function of ZO‐1, occludin and claudin‐5 in the intestinal epithelium. 158

Microbiota products combine with intestinal mucosal cells to produce mucin to inhibit the colonization of pathogens. 126 Innate immune cells are distributed in the host‐microbiome interface of the mucosa, especially DCs to detect microbial components or products, and provide MHC to promote T cell activation. 126 , 128 Studies have shown that an increase in lipopolysaccharides production by microbiota and a decrease in SCFA production can result in inflammation. 12 , 159 Lipopolysaccharides can inhibit innate immune signals and lead to immune dysfunction. SCFA acts on GPR, inhibits histone deacetylase expression, increases the intestinal tight junction mRNA and protein expression and reduces intestinal permeability to protect intestinal barrier integrity. 160 Butyric acid can contribute to intestinal mucosa by stimulating mucin synthesis and facilitating tight junction formation. At the same time, tryptophan metabolites of bacteria can regulate intestinal barrier function through aromatic hydrocarbon receptors. 157 The intestinal microbiota regulates the response of mucosal products secreted by IgA and AMPs, which require stimulation from symbiotic microorganisms. Simultaneously, IgA and AMPs function to shape and maintain microbial communities, neutralize bacterial toxins and inhibit bacterial reproduction. 161 Experiments have demonstrated that the intestinal microbiota can migrate to PLNs and act through NOD2 receptors to accelerate T1D onset in mice. 33

Consequently, the intestinal microbiota maintains epithelial barrier integrity and shapes the mucosal immune system, balancing host defence and oral tolerance with microbial metabolites, components and attachment to host cells.

4.2. Intestinal permeability

Intestinal permeability refers to the property that enables solute and fluid exchange between the lumen and tissue. The intestinal barrier comprises a mucus layer (biological barrier) and an intestinal epithelial layer (physical barrier). The impairment of the intestinal barrier is referred to as ‘leaky gut’, which is mainly caused by bacterial infections, oxidative stress, alcohol or chronic allergen exposure, and dysbiosis. 162 Impaired intestinal barrier integrity, particularly disruption of tight junctions, can enhance intestinal permeability. 163 , 164 The translocation of intestinal microbiota and their metabolites into circulation disrupts self‐tolerance and an elevation in systemic inflammation, thereby facilitating the development of T1D. 157 On the one hand, bacterial translocation further disrupts the stability of intestinal microbiota, leading to the imbalance of intestinal mucosal immunity, especially microbial‐antigen‐specific sIgA and AMPs. This decreases the ability to neutralize toxins and promotes the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria. On the other hand, reduced production of bacterial metabolites such as SCFAs and dysfunction of immune system receptors can trigger inflammation within the mucosal immune system. 157

Studies have demonstrated increased intestinal permeability in children with islet autoimmunity, particularly in those who subsequently develop T1D or possess a genetic susceptibility to the disease. 43 , 165 This phenomenon has been associated with alterations in interepithelial junctions as revealed by electron microscopy. 166 Similarly, elevated intestinal permeability has been identified before the onset of autoimmune diabetes in female NOD mice, 15 consistent with previous findings in diabetic BB rats. 167 Loss of gut barrier integrity triggers activation of islet‐reactive T cells within the gut mucosa. These activated T cells, which express gut‐homing marker α4β7 integrin, subsequently migrate to PLN and induce T1D. 15 These findings suggest that enhanced intestinal permeability precedes the onset of T1D rather than being a consequence of diabetes‐induced metabolic alterations. Besides, in addition to physical barriers, recent studies have highlighted the significance of the mucus layer in the pathogenesis of T1D. 15 , 24 Alterations in the composition of the mucus layer, including mucins and AMPs, are present in human T1D patients. These changes are linked to dysbiosis, characterized by a reduced mucus‐associated gut microbiota of numerous SCFA‐producing species that play a crucial role in maintaining mucus layer integrity and gut immune tolerance like Clostridium butyricum, Roseburia intestinalis and Bifidobacterium dentium. 24 Therefore, it has been proposed that T1D originates from the intestine, and regulating intestinal permeability could serve as an effective strategy for modifying the microbiota profile and preventing the development of T1D. 8 , 168 , 169

At present, it is difficult to conclude whether microbial alterations are causal or consequential of T1D, and further intervention studies in humans are needed. However, current studies have found that changes in microbiota can regulate intestinal permeability, and intestinal permeability changes occur before T1D, so we believe that it is feasible to regulate microbiota to intervene in the development of T1D. Treatment methods such as faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), prebiotics and probiotics can increase the proportion of related bacteria and maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier, thereby protecting against T1D. 162

4.3. Virome

The enterovirus group includes endogenous retroviruses, eukaryotic viruses and most phages that infect bacteria in the human gut. 170 Phages infect their bacterial hosts and replicate by either exploiting host genomic replication machinery or by disrupting host transcription and translation processes. 171 A study found a significant association between islet autoimmunity and the number of stool samples positive for all enteroviruses, with common viruses including enterovirus bocaparvovirus, anelovirus, parechovirus and so on. 172 A meta‐analysis of 56 studies showed an association between enterovirus and islet autoimmunity, T1D or onset of T1D within 1 month. 173 Enterovirus C is the most relevant, followed by Enterovirus B and Enterovirus A. In addition, Coxsackievirus B1 and Coxsackievirus B4 are also closely related to T1D. 173

The presence of chronic, low‐grade enterovirus infection in the early stages of T1D and the magnitude of the association between enterovirus and T1D was greatly detected in peripheral blood support the contribution of enterovirus to the development of T1D by establishing persistent infection. 173 The presence of multiple virus‐positive stool samples suggests that the intestinal mucosa may be a potential reservoir for persistent pancreatic infection. 172 Given the dependence of viruses on cell survival, we propose that the enterovirus affects the composition of the gut microbiota and may also invade host cells to indirectly induce inflammation‐related cellular damage, thereby promoting the development of T1D. 174 Studies have shown that naturally occurring adenovirus infections in nonhuman primates are associated with profound changes in microbiota, with an overall increase in Firmicutes and Clostridia observed in infected animals. 175

Therefore, anti‐viral therapy may protect against T1D. A phase 2, placebo‐controlled, randomized, parallel‐group, double‐blind trial suggested that anti‐viral therapy could preserve residual insulin production in children and adolescents with new‐onset T1D. 176 In addition, the first multivalent vaccine developed against Coxsackievirus B1‐B5 (PRV‐101) for the prevention of T1D showed protection against Coxsackievirus B‐induced T1D in an experimental mouse model and showed strong immunogenicity and safety. 177 However, the efficacy and safety of the vaccine in humans need to be tested in clinical trials. Moreover, the vaccine has the limitation of targeting coxsackievirus‐induced T1D, so widespread application for primary prevention is still a long way off.

4.4. Diet

Diet modulates the risk of T1D by affecting the gut microbiota and immune system. 44 Increased intake of total sugars and higher diet glycaemic index are associated with an increased risk of progression to T1D in autoantibody‐positive individuals. 178 High‐fat diet (HFD) protects NOD mice from the effects of autoimmune diabetes. HFD‐NOD mice showed an increased abundance of Verrucomicrobia, which increased islet Treg cells and delayed diabetes onset, 179 suggesting the feasibility of diet regulating gut microbiota composition to protect against T1D.

Evidence from human and animal studies has demonstrated that a gluten‐free diet during pregnancy reduces the risk of T1D, 180 and the composition of the intestinal microbiota of the newborn is also related to diet. 181 Gluten‐containing standard (STD) diet is strongly associated with T1D as well as celiac disease. 7 Results from BALB/c mice induced by STD diet showed a significant increase in Th17 cells and a decrease in the proportion of γδT cells in PLN. 182 As discussed previously, Th17 cells are detrimental to T1D progression, while γδT cells mainly induce mucosal tolerance to prevent T1D. In addition, STD‐fed mice CD103 integrin was significantly elevated compared with the gluten‐free diet, promoting T cell homing to the intestinal compartment for immune response. 182 STD diet promotes the development of T1D by modulating immune cell responses, so reducing wheat gluten intake may protect against T1D to some extent, especially for those with high genetic risk.

SCFAs are major end‐products produced by the decomposition of dietary fibre by intestinal microbiota fermentative activity, including butyrate, acetate and propionate, which can regulate intestinal inflammation and autoimmune reactions. 183 Notably, the Diabetes and Prevention study in Finland identified that SCFAs were more abundant in the faeces of the control group, with comparison to confirmed cases of T1D in children. 178 , 184 Feeding NOD mice with a diet containing the combination of acetate and butyrate prevents the development of T1D, primarily by restricting autoreactive T cells through acetate and enhancing Treg cells. 185 IL‐18 is involved in repairing intestinal epithelial integrity and homeostasis, butyrate and acetate upregulate IL‐18 protein expression in IECs to reduce intestinal permeability and the incidence of T1D. 44 , 186 SCFAs act as extracellular signaling molecules by binding to their homologous GPRs, FFAR2 and FFAR3. This binding inhibits insulin secretion by coupling to Gi‐type G proteins, 187 and it also influences the migration and recruitment of immune cells to endothelial cells through histone deacetylase. 188 , 189 As mentioned above, increased intestinal permeability precedes the onset of T1D, so inhibiting the progression of T1D by dietary reduction of intestinal permeability is a reliable therapeutic approach. For instance, increasing dietary fibre intake and supplements abundant in probiotics such as Lactobacillus as well as Bifidobacterium can improve SCFA production, which may have a beneficial role in the prevention and treatment of T1D.

| List of abbreviations | |||

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides | IDO | Indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase |

| AHR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor | MUC | Mucosal mucins |

| α‐GalCer | α‐Galactosylceramide | MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| BB | Bio‐breeding | MAIT | Mucosal‐associated invariant T |

| CVB4 | Coxsackievirus B4 | MR1 | MHC‐I related molecular |

| DCs | Dendritic cells | MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| DP | Double positive | NOD | Non‐obese diabetic |

| DN | Double negative | NK | Natural killer |

| EBV | Epstein‐Barr virus | NETs | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| FFA | Free fatty acid | PLN | Pancreatic lymph nodes |

| FFAR | Free fatty acid receptor | sIgA | Secretory immunoglobulin A |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box protein P3 | SCFA | Short‐chain fatty acids |

| FMT | faecal microbiota transplantation | STD | Gluten‐containing standard |

| GzB | Granzyme B | T1D | Type 1 diabetes |

| GALT | Gut‐associated lymphoid tissue | Tregs | T regulatory cells |

| GPR | G‐protein‐coupled receptor | TFN‐α | Tumour necrosis factor α |

| HFD | High‐fat diet | TCR | T cell receptor |

| IL | Interleukin | TGF‐β | Transforming growth factor‐β |

| IgA | Immunoglobulin A | TLR | T lymphocyte‐like receptors |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G | TEDDY | The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young study |

| iNKT | Invariant natural killer T | ||

| ILCs | Innate lymphoid cells | Th2 | T helper 2 |

| IFN‐γ | Interferon‐γ | ZO | Zonula occludens |

5. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

The pancreas is anatomically connected to the gastrointestinal tr act through the pancreatic duct, establishing a crucial link between intestinal immunity and the pancreas. IECs play a pivotal role in maintaining local and systemic immunologic homeostasis by engaging in physical and biochemical interactions with both innate and adaptive immune populations. MAIT cells specifically recognize microbial vitamin derivatives, while iNKT cells target glycolipid antigens often overlooked by conventional T cells. This mechanism is an essential supplement to the body's overall immune response.

There is a growing understanding of the relationship between the intestinal immune system and autoimmune diseases; however, the precise mechanism by which the intestinal immune system regulates the islets remains unclear. The main mechanism that has been extensively studied is the regulation of pancreatic autoimmunity through the immune interaction of LN co‐drainage. 190 This process is predominantly characterized by the infiltration of intestinal immune cells into the pancreatic islets via lymphatic or blood circulation, ultimately modulating their function. Nevertheless, it is still worthwhile to explore other potential pathways.

The current treatment of T1D primarily relies on insulin therapy, which necessitates lifelong usage and does not prevent the development of diabetic complications. Pancreatic and islet transplantation is a promising approach for patients with T1D who experience an absolute deficiency of islet β cells. However, the utilization of transplantation for routine treatment is limited due to organ scarcity, transplant‐related complications and other factors. 111 Immunosuppressive agents are one of the classic immunotherapy methods, including cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, rabbit anti‐thymocyte globulin, and so on. However, long‐term use can increase the risk of chronic immunosuppression, such as severe infection, nephrotoxicity, and cancer. 191 Recently, autologous hematopoietic stem cells have been proposed to restore islet function, 115 although further exploration is required regarding the types and mechanisms by which stem cells act. The laborious steps involved in cell extraction, induction, and re‐infusion need optimization while acknowledging that the potential side effects of immunosuppressants should not be underestimated. Targeted therapy is a specific immune pathway targeting pancreatic islets involved in tolerance. Currently, drugs developed include templizumab, rituximab and alefacept and so on, which target treatment of β cell destruction and reduce fatal events due to severe hypoglycaemia. 192 The study demonstrated that the patients with recent onset of T1D had prolonged preservation time of endogenous insulin production and reduced requirement for exogenous insulin after taking two courses of alefacept. In addition, a similar degree of C‐peptide preservation was observed in patients treated with teplizumab and otelixizumab with long‐term follow‐up. 193 However, the increased incidence of Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) reactivation or EBV‐related disease during treatment cannot be ignored. Thus, the concept of continuous dosing with fewer side effects has driven drug development. Efficacy results of peptide immunotherapy IMCY‐0098 in adults with new‐onset T1D and Ustekinumab in adolescents showed safety. 194 , 195 However, compared with other less targeted immunotherapies for T1D, the effect of treatment on both the immune system and β cell function is greatly delayed. The slowing of β‐cell loss in the treatment group did not become apparent over 6–12 months. 195 The combination of less targeted early‐acting drugs such as teplizumab with safer late‐acting drugs such as Ustekinumab is a good solution, but the synergistic efficacy needs to be verified in more cohorts. Moreover, the application of these drugs in T1D treatment is still in the preclinical and clinical trial stages, making it difficult to convert from mouse models to human applications. 191 Therefore, if the function of islets can be restored by enhancing the communication between the intestinal immune system and the islets, it is anticipated that T1D could be treated more conveniently. Abnormal intestinal microbiota, alterations in intestinal mucosal permeability, and regulation of mucosal immune cells collectively contribute to the onset of T1D. Dietary adjustments and faecal transplantation can improve the regulation of intestinal microbiota. De Groot's study of FMT treatment in young patients with recent‐onset T1D showed that FMT can effectively prolong β cell function, which is mediated by T cells and associated with a specific strain of Desulfovibrio piger. 196 In a randomized controlled trial in obese young adults with T1D (duration≥1 year), the abundance of SCFA‐producing genera Bacteroides and Alistipes was inversely associated with carbohydrate intake, and faecal SCFA abundance was positively associated with dietary fibre intake. 197 The Australian T1D Gut Study cohort found that plasma acetate was positively associated with carbohydrate intake and inversely associated with fat intake. 198 Intestinal mucosal permeability closely correlates with the modulation of mucosal immune cells. By suppressing inflammatory responses, increasing Treg cell proportions and reducing inflammatory cytokine secretion, the promoting effect of the gut‐pancreas axis on T1D pathogenesis can be inhibited. These treatment side effects are significantly reduced compared to immunosuppressive agents, and the difficulty of therapy is reduced compared to stem cell transplantation. Given the limitations of current targeted therapies, we propose that modulating the gut microbiota composition to optimize clinical metabolic and immune responses could complement targeted therapies to drive T1D treatment. We suggest that larger cohorts should be established to validate the efficacy of targeted immunotherapies in individuals consuming a high‐fibre diet.

The incidence of T1D has steadily and rapidly increased over the past 50 years. This increase is too fast to be caused by changes in the genetic risk profile and is instead thought to be caused by altered exposure to environmental risk factors. 199 As we discussed above, T1D has been associated with diet and infections, particularly enterovirus infections. Diet, a key component of T1D management, modulates the intestinal microbiota and its metabolically active byproducts‐including SCFA‐through fermentation of dietary fibre. 197 An inverse association between dietary fibre and glucose was observed in adults with early diabetes, and a protective association between fibre intake and poor glycemic control was observed in those without diabetes or with early diabetes. 200 Nevertheless, it is necessary to emphasize that the evidence regarding the efficacy of dietary regimens in the primary prevention of diabetes is insufficient. The current studies based on The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young study (TEDDY) failed to identify statistically significant protective associations between high soluble fibre intake and pancreatic autoimmunity or T1D, suggesting that testing the effectiveness of these approaches would demand extremely large enrollments and long‐term follow‐up. 201 Strategies targeting immune cells show promising efficacy in the early prevention of T1D. The recent T1D prevention trial, TrialNet (TN‐10), enrolled individuals at high risk of developing T1D, at least two islet autoantibodies and dysglycemia. Participants were randomized to receive a 14‐day course of teplizumab or a placebo. The trial delayed the diagnosis of diabetes by a median of 32.5 months and demonstrating improved β cell function. 39

In general, our current understanding of the function of the human intestinal immune system is rather limited, and the mechanism of the gut‐pancreatic axis remains to be further explored. We hope that more studies with larger cohorts and longer follow‐up will be conducted in the future.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RL and JZ were mainly responsible for designing the content structure, collecting literature and writing the original draft. YX, JH and ZZ made helpful suggestions for revising this manuscript. LX supervised the whole work and significantly contributed to designing the work and writing the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province for Youths (2022JJ40718 to L.X., 2022JJ40689 to J.H.), the Scientific Research Launch Project for new employees of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (L.X.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270891 to Y.X., 82200933 to J.H.), the Scientific research fund of National Clinical Research Center for Metabolic Diseases (2023ZLNL004 to J.H.) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JC0003 to Z.Z.).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1111/dom.16101.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Liu R, Zhang J, Chen S, et al. Intestinal mucosal immunity and type 1 diabetes: Non‐negligible communication between gut and pancreas. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27(3):1045‐1064. doi: 10.1111/dom.16101

Ruonan Liu and Jing Zhang contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hermann R, Knip M, Veijola R, et al. Temporal changes in the frequencies of HLA genotypes in patients with type 1 diabetes—indication of an increased environmental pressure? Diabetologia. 2003;46(3):420‐425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Söderström U, Aman J, Hjern A. Being born in Sweden increases the risk for type 1 diabetes – a study of migration of children to Sweden as a natural experiment. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(1):73‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nisticò L, Iafusco D, Galderisi A, et al. Emerging effects of early environmental factors over genetic background for type 1 diabetes susceptibility: evidence from a Nationwide Italian Twin Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):E1483‐E1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziegler AG, Danne T, Dunger DB, et al. Primary prevention of beta‐cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes – The Global Platform for the Prevention of Autoimmune Diabetes (GPPAD) perspectives. Mol Metab. 2016;5(4):255‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oakey H, Giles LC, Thomson RL, et al. Protocol for a nested case‐control study design for omics investigations in the environmental determinants of islet autoimmunity cohort. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):2198255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Lernmark Å, et al. Genetic and environmental interactions modify the risk of diabetes‐related autoimmunity by 6 years of age: The TEDDY Study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(9):1194‐1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rewers M, Bugawan TL, Norris JM, et al. Newborn screening for HLA markers associated with IDDM: diabetes autoimmunity study in the young (DAISY). Diabetologia. 1996;39(7):807‐812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaarala O, Atkinson MA, Neu J. The "perfect storm" for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes. 2008;57(10):2555‐2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Tommaso N, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani FR. Intestinal barrier in human health and disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23):12836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horai R, Zárate‐Bladés CR, Dillenburg‐Pilla P, et al. Microbiota‐dependent activation of an autoreactive T cell receptor provokes autoimmunity in an immunologically privileged site. Immunity. 2015;43(2):343‐353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trivedi PJ, Bruns T, Ward S, et al. Intestinal CCL25 expression is increased in colitis and correlates with inflammatory activity. J Autoimmun. 2016;68:98‐104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li B, Selmi C, Tang R, Gershwin ME, Ma X. The microbiome and autoimmunity: a paradigm from the gut‐liver axis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15(6):595‐609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hänninen A, Salmi M, Simell O, Jalkanen S. Mucosa‐associated (beta 7‐integrinhigh) lymphocytes accumulate early in the pancreas of NOD mice and show aberrant recirculation behavior. Diabetes. 1996;45(9):1173‐1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haghikia A, Jörg S, Duscha A, et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity. 2015;43(4):817‐829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sorini C, Cosorich I, Lo Conte M, et al. Loss of gut barrier integrity triggers activation of islet‐reactive T cells and autoimmune diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(30):15140‐15149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abdellatif AM, Sarvetnick NE. Current understanding of the role of gut dysbiosis in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2019;11(8):632‐644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Allaire JM, Crowley SM, Law HT, Chang SY, Ko HJ, Vallance BA. The intestinal epithelium: central coordinator of mucosal immunity. Trends Immunol. 2018;39(9):677‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoytema van Konijnenburg DP, Reis BS, Pedicord VA, Farache J, Victora GD, Mucida D. Intestinal epithelial and intraepithelial t cell crosstalk mediates a dynamic response to infection. Cell. 2017;171(4):783‐794.e713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kayama H, Okumura R, Takeda K. Interaction between the microbiota, epithelia, and immune cells in the intestine. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:23‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walker JA, McKenzie ANJ. T(H)2 cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):121‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lo Conte M, Antonini Cencicchio M, Ulaszewska M, et al. A diet enriched in omega‐3 PUFA and inulin prevents type 1 diabetes by restoring gut barrier integrity and immune homeostasis in NOD mice. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1089987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bosi E, Molteni L, Radaelli MG, et al. Increased intestinal permeability precedes clinical onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49(12):2824‐2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mønsted M, Bilgin M, Kuzma M, et al. Reduced phosphatidylcholine level in the intestinal mucus layer of prediabetic NOD mice. APMIS. 2023;131(6):237‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lo Conte M, Cosorich I, Ferrarese R, et al. Alterations of the intestinal mucus layer correlate with dysbiosis and immune dysregulation in human type 1 Diabetes. EBioMedicine. 2023;91:104567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao Q, Maynard CL. Mucus, commensals, and the immune system. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2041342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu W, Luo X, Tang J, et al. A bridge for short‐chain fatty acids to affect inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease positively: by changing gut barrier. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(5):2317‐2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Korpela K, de Vos WM. Early life colonization of the human gut: microbes matter everywhere. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;44:70‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adlerberth I, Wold AE. Establishment of the gut microbiota in Western infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(2):229‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee SM, Donaldson GP, Mikulski Z, Boyajian S, Ley K, Mazmanian SK. Bacterial colonization factors control specificity and stability of the gut microbiota. Nature. 2013;501(7467):426‐429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, Cani PD. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut. 2022;71(5):1020‐1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alkanani AK, Hara N, Gottlieb PA, et al. Alterations in intestinal microbiota correlate with susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(10):3510‐3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, et al. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(2):260‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Costa FR, Françozo MC, de Oliveira GG, et al. Gut microbiota translocation to the pancreatic lymph nodes triggers NOD2 activation and contributes to T1D onset. J Exp Med. 2016;213(7):1223‐1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang X, Huang J, Peng J, et al. Gut microbiota from B‐cell‐specific TLR9‐deficient NOD mice promote IL‐10(+) Breg cells and protect against T1D. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1413177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1109‐1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hu J, Ding J, Li X, et al. Distinct signatures of gut microbiota and metabolites in different types of diabetes: a population‐based cross‐sectional study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;62:102132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lledó‐Delgado A, Preston‐Hurlburt P, Currie S, et al. Teplizumab induces persistent changes in the antigen‐specific repertoire in individuals at risk for type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2024;134(18):e177492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ashraf MT, Ahmed Rizvi SH, Kashif MAB, Shakeel Khan MK, Ahmed SH, Asghar MS. Efficacy of anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibodies in delaying the progression of recent‐onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review, meta‐analyses and meta‐regression. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25(11):3377‐3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xie QY, Oh S, Wong A, Yau C, Herold KC, Danska JS. Immune responses to gut bacteria associated with time to diagnosis and clinical response to T cell‐directed therapy for type 1 diabetes prevention. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15(719):eadh0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bradley CP, Teng F, Felix KM, et al. Segmented filamentous bacteria provoke lung autoimmunity by inducing gut‐lung axis Th17 cells expressing dual TCRs. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22(5):697‐704.e694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lahdenperä AI, Hölttä V, Ruohtula T, et al. Up‐regulation of small intestinal interleukin‐17 immunity in untreated coeliac disease but not in potential coeliac disease or in type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167(2):226‐234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Westerholm‐Ormio M, Vaarala O, Pihkala P, Ilonen J, Savilahti E. Immunologic activity in the small intestinal mucosa of pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(9):2287‐2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harbison JE, Roth‐Schulze AJ, Giles LC, et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability in children with islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20(5):574‐583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yap YA, Mariño E. An insight into the intestinal web of mucosal immunity, microbiota, and diet in inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim TK, Lee JC, Im SH, Lee MS. Amelioration of autoimmune diabetes of NOD mice by immunomodulating probiotics. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lu JT, Xu AT, Shen J, Ran ZH. Crosstalk between intestinal epithelial cell and adaptive immune cell in intestinal mucosal immunity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(5):975‐980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang L, Zhu L, Qin S. Gut microbiota modulation on intestinal mucosal adaptive immunity. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:4735040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Montalban‐Arques A, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP, Bernardo D. The innate immune system in the gastrointestinal tract: role of intraepithelial lymphocytes and lamina propria innate lymphoid cells in intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(8):1649‐1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]