Abstract

Giardia lamblia is medically important as a cause of diarrhea and malabsorption throughout the world and is thought to be one of the earliest-branching eukaryotes on a phylogenetic tree. Nevertheless, the mechanisms of inheritance are largely unknown. The trophozoites of Giardia and other diplomonads are interesting in their possession of two nuclei that are identical or similar in several respects. They replicate at nearly the same time, have similar quantities of DNA, and are both transcriptionally active. We used fluorescence in situ hybridization to demonstrate that genes from each of the five chromosomes are found in both nuclei, confirming that each nucleus has at least one complete copy of the genome. This raises a second question. The alleles of a gene in different nuclei are expected to accumulate different mutations, but surprisingly, the degree of heterozygosity in a clone is very low. One possible mechanism for eliminating sequence differences between nuclei is that each daughter cell receives two copies of the same nucleus at cell division. We used trophozoites with a plasmid transfected into a single nucleus to demonstrate that the two nuclei are partitioned equationally at cytokinesis. The mechanism(s) by which homozygosity is maintained will require further investigation.

Protists of the genus Giardia infect the small intestines of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals (1). Giardia lamblia is the species that infects humans and a variety of other mammals. In addition to being significant for the medical importance of G. lamblia (also Giardia intestinalis and Giardia duodenalis), the Giardia species are of interest because they belong to the diplomonads, one of the most basal eukaryotic branches on a phylogenetic tree (4, 25). G. lamblia and the other diplomonads are also of interest because of their possession of two nuclei. The two nuclei in a trophozoite are identical in all ways that have been reported. They replicate at approximately the same time (28), are both transcriptionally active (15), and contain similar quantities of DNA (10, 15). These observations indicate the contrast between the two nuclei of Giardia and the two or more nuclei of the ciliates, such as Paramecium and Tetrahymena species. Ciliate cells contain one or more micronuclei which have a complete diploid genome; these genes are transcriptionally silent and participate in sexual reproduction. Ciliate cells also have a macronucleus which contains many copies of each gene on separate chromosomes; these genes are transcribed and translated but are not inherited during sexual reproduction.

The existence of two nuclei in the diplomonads raises a number of questions regarding the origin and maintenance of both nuclei. Although examples of organisms with single nuclei have been documented by microscopy (R. Adam, unpublished observations), there is no way to determine whether these uninuclear trophozoites are viable. Lines of organisms with single nuclei have not been reported, suggesting that both nuclei are required. One possible reason for the requirement of two nuclei that has not been formally ruled out is the possession of different complements of DNA by the two nuclei. Although the two nuclei contain similar amounts of DNA and each contains copies of the ribosomal DNA as demonstrated by DNA-DNA in situ hybridization (15), the ribosomal DNA repeats are found on multiple chromosomes (2, 6), and these studies did not have high enough resolution to allow the detection of single-copy genes.

G. lamblia trophozoites contain five chromosomes ranging in size from 1.6 to 3.8 Mb and defined by chromosome-specific probes (5). Although the haploid genome size of 12 Mb predicted by the sum of the chromosome sizes (5) differs from the estimates of 30 Mb (21) and 80 Mb (12) determined by CoT analysis, it is supported by data from the Giardia genome sequencing project, which is currently at approximately 90 to 95% completion (18) (www.mbl.edu/Giardia). Calculations of the total DNA content by a variety of methods (3) have yielded estimates of 1.34 × 108 bp, predicting up to 8 to 12 copies of each chromosome compared with the haploid genome size (5). On the other hand, the detection of up to four alleles of repeat-containing vsp genes (30) and up to four size variants of chromosome 1 (14) within a single clone suggests a functional ploidy of four. The discrepancy between these ploidy estimates is adequately explained by recent fluorescence-activated cell sorting data showing that trophozoites have the 4C amount of DNA in G1 and so are probably tetraploid but spend most of their time in the G2 phase of DNA replication with a total DNA complement of 8C (10).

In sexual organisms, the degree of allelic heterozygosity is typically 1% or less (0.05 to 0.1% in humans [22]). However, it can be much higher in organisms with a ploidy of two or more that have been reproducing only asexually for long periods of time, provided that mitotic gene conversion and crossing over do not intervene (11). For example, allelic heterozygosity of three genes in the bdelloid rotifers is on the order of 15 to 50% for synonymous substitutions (27). G. lamblia has a level of allelic heterozygosity that is less than 0.1% for the genotype that includes the WB isolate, as demonstrated by multiple sequences of the triose phosphate isomerase (tim) gene from multiple isolates (9). A low degree of allelic heterozygosity within a single nucleus could potentially be explained by a high rate of mitotic recombination, but the maintenance of homozygosity between the two nuclei (homokaryosity) requires other explanations.

One possible explanation for a low level of heterozygosity would be a form of cell division in which the progeny of each of the two nuclei are distributed to different trophozoites. A study of cell division using light microscopy of fixed cells (13) was interpreted as showing that trophozoites undergo a ventral-dorsal form of cytokinesis in which each daughter cell receives one copy of each nucleus and which maintains the left-right asymmetry of the nuclei (Fig. 1). We refer to this as equational partitioning of nuclei, analogous to the equational partitioning of chromatids during mitosis. If this were correct, heterozygosity between the nuclei would be maintained from generation to generation. However, the figures in the work of Filice (13) are not completely convincing and might depict artifacts of fixation. If, on the other hand, nuclear partitioning in Giardia segregates two left nuclei to one daughter trophozoite and two right nuclei to the other, heterozygosity between nuclei (heterokaryosity) would be eliminated in each generation. A second possible explanation for low heterokaryosity would be if the two nuclei had different partial sets of chromosomes, so that all alleles of each gene were found in only one nucleus. This would only be possible with equational partitioning of nuclei, because segregational partitioning would result in daughter cells with incomplete genomes. In addition, a ventral-ventral form of replication has been proposed (M. Frisardi and J. Samuelson, 11th Woods Hole Mol. Parasitol. Meet., abstr. 202C, 2000) in which the left-right symmetry would be reversed each generation. This ventral-ventral form of replication would not resolve heterokaryosity but would result in the equal distribution of a specific heterozygosity between right and left nuclei in a population of trophozoites.

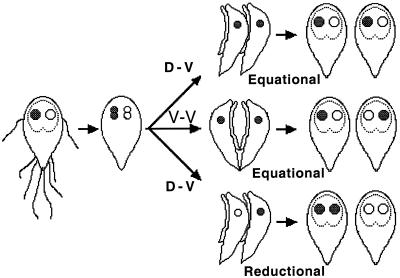

FIG. 1.

Three possible modes of cytokinesis and the resulting distribution of the nuclei are shown. Equational division with ventral-dorsal cytokinesis (top) maintains nuclear asymmetry and handedness in the progeny. Equational division with ventral-ventral cytokinesis (middle) reverses the handedness with each round of replication. Reductional division with either ventral-dorsal (bottom) or ventral-ventral cytokinesis homogenizes the nuclei with each round of replication.

In the present study, we used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to track an extrachromosomal plasmid transfected into one nucleus and show that nuclear partitioning is equational, with left-right asymmetry maintained. We also used FISH with multiple single-copy genes from each of the five chromosomes to show that both nuclei contain at least one copy of each chromosome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source and cultivation of G. lamblia trophozoites.

Trophozoites were grown in modified TYI-S-33 medium as described previously (16). The WB isolate was originally obtained from a patient with symptomatic giardiasis who probably acquired his infection in Afghanistan (24). The WB isolate was cloned twice in succession on soft agar and then cloned again twice by limiting dilution, resulting in the WBA6 cloned line (20). The ISR E11 isolate is a doubly cloned line of the ISR isolate, which belongs to the same genotype as WB but is characterized by size variability of chromosome 1 (2, 5). The cloning done in the present study was performed as previously described (5).

Nucleic acid preparation and hybridization.

Giardia genomic DNA was prepared by using the Genomic-tip 100/G column (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif). Plasmid DNA was prepared by alkaline lysis followed by column purification using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). DNA was digested, separated by agarose electrophoresis, and transferred to nylon in alkaline buffer (0.5 N NaOH, 1 M NaCl). Probes were labeled by random priming. After hybridization at 50°C overnight in hybridization buffer (0.08% Ficoll, 0.08% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.17% milk powder), the blots were washed in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, with a final washing temperature of 65°C.

Probes and probe labeling.

The probes are described in Table 1. Some have previously been described as noted in the table. The remaining clones have been used as part of the Giardia genome project 18; (www.mbl.edu/Giardia). These plasmid clones were constructed by mechanical shearing followed by size selection and ligation into a pUC18 plasmid. The size range is approximately 2.5 to 5 kb.

TABLE 1.

Probes used for FISH

For the genome project clones, the two GenBank numbers represent single-pass reads from each end of the clone.

P4F11 is relatively near the telomere.

GDH is on the telomeric 260-kb NotI fragment.

Triose phosphate isomerase gene.

For single-color FISH, the plasmid probes were labeled with biotin by nick translation (BioNick labeling system; Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) using a solution containing 1 μg of DNA; a 0.02 mM concentration (each) of dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 0.01 mM dATP; 0.01 mM biotin-14-dATP; 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8); 5 mM MgCl2; 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol; nuclease-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) (10 μg/ml); 2.5 U of DNA polymerase I; 0.035 U of DNase I; 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); 0.5 mM magnesium chloride; 0.01 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; and 5% (vol/vol) glycerol. The labeling reaction was incubated at 15°C for 150 min.

For two-color FISH, the second probe was labeled with fluorescein by nick translation using a solution containing plasmid DNA (1 μg); 2.5 U of DNA polymerase I; 0.0007 U of DNase I/μl; 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); 0.5 mM magnesium chloride; 0.01 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 5% (vol/vol) glycerol; nuclease-free BSA (10 μg/ml); a 0.02 mM concentration (each) of dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 0.01 mM dATP; 0.01 mM fluorescein-12-dATP; 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8); 5 mM MgCl2; and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Biotin- and fluorescein-labeled probes were purified by sodium acetate and ethanol precipitation followed by washing with 70% ethanol. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mM EDTA) and stored at −20°C.

A 25-mer oligonucleotide containing five repeats of the telomeric sequence TAGGG (6) was end labeled with terminal transferase using 5 pmol of oligonucleotide, 0.25 mM CoCl2, 50 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM Tris acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 U of terminal transferase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) at 37°C for 1 h, and this was followed by removal of unincorporated nucleotides by spun-column chromatography using Sepharose G-25 (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.).

Slide preparation and hybridization.

Trophozoites were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline, placed on slides (treated with 0.5% poly-l-lysine), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow the trophozoites to adhere to the slide by their ventral disks. The slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and preserved in 70% ethanol at −20°C. Before use, the slides were rehydrated in 2× SSC and treated with DNase-free RNase for 90 min in 37°C. The slides were then treated with 0.5%Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature and dehydrated in 70% ethanol for 5 min and 100% ethanol for 5 min.

The slides were denatured in 70% formamide-2× SSC at 70°C for 2 min and then dehydrated in 70% ethanol (−20°C) and 100% ethanol for 5 min each and air dried. Twenty microliters of probe was mixed with 10 μg of salmon DNA and 10 μg of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA, air dried, and resuspended in 10 μl of 100% formamide. Probes were denatured at 95°C for 10 min and then immediately placed on ice. An equal volume of hybridization buffer (4× SSC, 20% dextran sulfate, BSA [4 mg/ml]) was added. The probe solution was placed on Parafilm, and the slides were placed face down on the liquid and covered with Parafilm. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the slides were washed in 2× SSC with 50% formamide at 37°C for 30 min, followed by 2× SSC at 37°C and 1× SSC at room temperature for 30 min each.

Signal amplification was performed according to the manufacturer's directions (New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.). Briefly, the slides were blocked with TNB buffer (0.1 M Tris, pH 7.5; 0.15 M NaCl; 0.5% blocking reagent, supplied in kit) for 30 min at room temperature. Then the slides were incubated with streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase (HRP) complex (for biotin-labeled probes) or antifluorescein antibody-HRP (for fluorescein-labeled probes) for 30 min and washed with TNT buffer (0.1 M Tris, pH 7.5; 0.15 M NaCl; 0.05% Tween 20) for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the slides were incubated with cyanine-3 (Cy3)-tyramide or fluorescein-tyramide (New England Nuclear) for 30 min at room temperature and washed with TNT buffer for 5 min. The slides were mounted in antifade medium for microscopy.

For two-color FISH, the first signal was developed with streptavidin-HRP. Then, the remaining HRP was deactivated by incubating slides with 100 μl of 1% H2O2 in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0) for 15 min at room temperature. The slides were then washed three times for 5 min each in fresh TNT buffer at room temperature, followed by incubation with antifluorescein-HRP and Cy3-tyramide to develop the signal of the second probe.

Epifluorescence and confocal fluorescence microscopy.

The hybridized slides were observed using a reflected-light dual-color fluorescence microscope (model BH2-RFL; Olympus). The green fluorescence signal from fluorescein was visualized with a BP-490 filter, while the red fluorescence signal from Cy3 was visualized with a BP-545 filter. Laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed using a Leica model TCS-4D microscope with a pinhole setting of 100, the band-pass fluorescein isothiocyanate filter for the green (fluorescein) signal, and the LP-590 filter for the red (Cy3) signal. The images were collected with SCANWARE (version 5.10b) software from the same company.

Transfection and selection of puromycin-resistant trophozoites.

Giardia trophozoites were transfected by electroporation as described previously (23), using an episomal plasmid, 5′Δ5n-pac, which contains the puromycin-N-acetyltransferase (pac) gene (obtained from Theodore Nash).

RESULTS

Controls.

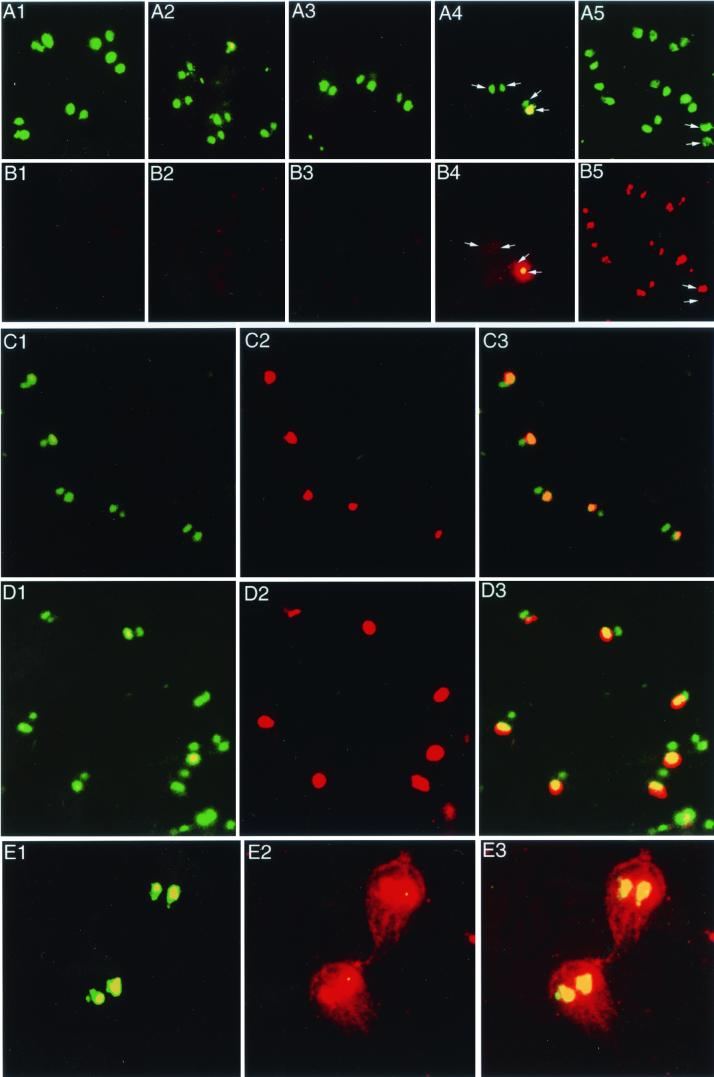

A set of control assays was used to identify the sensitivity and specificity of the present FISH protocol (Fig. 2A and B). When single-color FISH was performed, a nucleic acid-specific fluorescence dye, YoYo-1, was used to identify the location of the nuclei. YoYo-1 emits a fluorescent signal at 509 nm, while the Cy3 fluorochrome of the probe emits a fluorescent signal at 570 nm, allowing simultaneous detection of the probe signal and the nuclear position. The colocalization of the hybridization signal with that of the nuclear label confirmed the nuclear specificity of the probe hybridization. To rule out a false-positive signal from cellular RNA, the trophozoites were treated with RNase and hybridized with probe biotin-glutamate dehydrogenase (biotin-GDH) without denaturing the slide, in order to confirm that the probe was labeling DNA rather than RNA. The success of the RNase treatment was confirmed by the lack of hybridization of the probes to nondenatured slides (Fig. 1 and B1). A no-probe control was used to exclude the possibility of nonspecific staining during the FISH process (Fig. 2 and B2). There was also no hybridization to DNase-treated trophozoites or when pBluescript, pGEM, or pBR322 plasmids without inserts were used as probes (Fig. 3 and C3), confirming the specificity of the DNA-DNA hybridization of the probes to the nuclear DNA. The specificity of the signal was also supported by the high signal/noise ratio between the nuclear fluorescence signal and that of the cytoplasm and extracellular space (Fig. 2A and B).

FIG.2.

(A and B) Fluorescence microscopy showing the negative and positive controls for FISH. The YoYo-1 stain (green) indicates the positions of the nuclei (A), and Cy3 labeling (red) of the same field of trophozoites identifies the location of probe hybridization (B). (A1 and B1) RNase-treated undenatured trophozoites. The YoYo-1 stain identifies the nuclei (A1), while the GDH probe demonstrates no specific signal (B1). (A2 and B2) No-probe control. The YoYo-1 stain identifies the nuclei (A2), while the probe demonstrates no specific signal (B2). (A3 and B3) Vector control. The YoYo-1 stain identifies the nuclei (A3), while the PBR322 probe demonstrates no specific signal (B3). Vector controls with pBluescript II and pGEM also gave no signal (not shown). (A4 and B4) Trophozoites with 5′Δ5n-pac transfected into one nucleus. The YoYo-1 stain identifies the nuclei (A4), while the 5′Δ5n-pac probe demonstrates an intense signal in one of the two nuclei of the lower trophozoite (B4). The signal intensity of the transfected nucleus is so great that yellow bleed-through color can be see in the YoYo-1 stain (B4). In the upper trophozoite, neither nucleus was labeled by the 5′Δ5n-pac probe. (A5 and B5) Telomeric oligonucleotide (TAGGG)5. For most of the trophozoites, both nuclei were labeled, but the arrows demonstrate a trophozoite in which one nucleus appears partially degraded (A5) and shows no probe signal (B5). (C and D) Trophozoites transfected with 5′Δ5n-pac are shown after 2 weeks (C1 to 3), and the same line of transfected trophozoites is shown after 1 year (D1 to 3) of continuous in vitro growth, showing that even after approximately 1,000 generations, only one nucleus contains the transfected plasmid. The YoYo-1 nuclear stain (C1 and D1), pac hybridization signal (C2 and D2), and image overlays (C3 and D3) are shown. (E) Trophozoite morphology shown by overexposure. (E1) The YoYo-1 stain shows the position of nuclei. (E2) The trophozoite morphology is shown by overexposure of the slide after labeling by the β-actin probe. (E3) Overlay of E1 and E2.

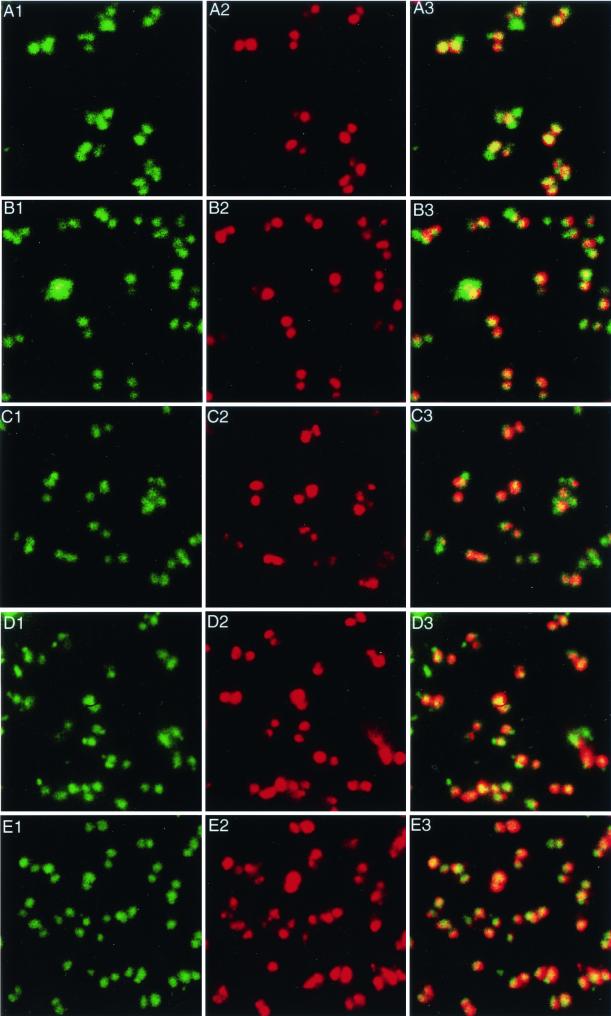

FIG. 3.

Single-color FISH with chromosome-specific probes. In each case, the YoYo-1 stain (green) indicates the positions of the nuclei (panels 1), and Cy3 labeling (red) of the same field of trophozoites identifies the location of probe hybridization (panels 2). The third image in each row is the overlay of the first two. (A) Chromosome 1, probe AJ2845; (B) chromosome 2, probe CI0032; (C) chromosome 3, probe AJ1265; (D) chromosome 4, probe AI0432; (E) chromosome 5, probe AJ2972. For each of these probes, the hybridization signal was seen in both nuclei in 90% of the trophozoites.

As a control for the presence of chromosomal DNA, an oligonucleotide containing the telomeric sequence TAGGG (6) was used to label the chromosomes of both nuclei. Both nuclei were labeled in the majority of trophozoites (Fig. 5 and B5), which indicates that both nuclei contain chromosomes. However, some trophozoites showed only one or no nuclei stained by the probe (see the example shown by arrows in Fig. 5 and B5). This is probably an artifact, since the simultaneous YoYo-1 stain showed that at least some unlabeled nuclei had suffered destruction during slide preparation (Fig. 2A and B).

Hybridization to transfected DNA.

The episomal vector, 5′Δ5n-pac, was transfected into strain WBA6 for use as a positive control. After selection by puromycin, the drug-resistant trophozoites were hybridized with a probe containing the pac sequence. The FISH result showed that trophozoite nuclei were strongly labeled by the probe (Fig. 4 and B4), which further confirms the effectiveness of the present FISH protocol. Interestingly, for all the trophozoites being labeled, only one of the two nuclei was labeled by the probe, which indicates that a foreign plasmid enters only one nucleus during transfection. This observation provides a marker to show the left-to-right orientation of the trophozoite. Further cloning of the transfected Giardia by limiting dilution yielded five clones from 192 wells. After being transferred into the fresh medium, two of five clones did not grow. The other three clones were used for FISH. Observations using Nomarski optics showed that 39 of 50 (78%) trophozoites adhered via their ventral side of the disk, while the other 22% attached via their dorsal side during the slide preparation procedure. FISH results on slides prepared in the same way demonstrated left/right nuclear staining ratios of 74:26, 20:80, and 24:76 for clones 1, 2, and 3, respectively. These observations suggest that the left nucleus of the original trophozoite of clone 1 and the right nuclei of clones 2 and 3 were transfected. More importantly, it shows that the left-right asymmetry of the nuclei is still preserved after many generations of culture (approximately 42 generations after 2 weeks of in vitro growth). In order to determine whether the transfected DNA remained in only one nucleus for a longer period of time, transfected organisms were continuously cultivated for 1 year (approximately 1,000 generations). The transfected DNA was never found in more than one nucleus (Fig. 2C and D), indicating that extrachromosomal DNA is not commonly copied or transferred from one nucleus to the other.

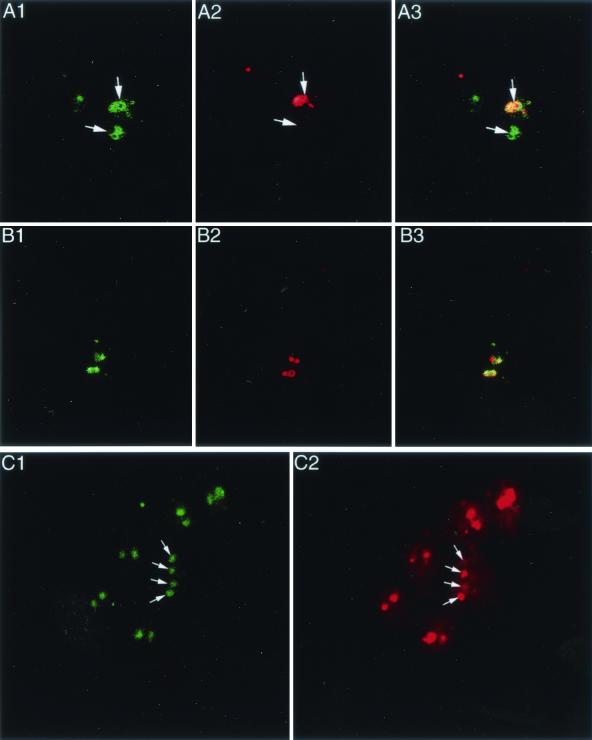

FIG. 4.

(A and B) Dual-color FISH with two chromosome 1 probes imaged by confocal microscopy. (A1) p5D2 with a fluorescein label; (A2) p4F11 with a Cy3 label; (A3) overlay of A1 and A2. The arrows indicate the nuclei of a trophozoite in which the p4F11 probe demonstrated hybridization to only one of the two nuclei. (B1 to 3) Same as A1 to 3, except that another field in which both probes hybridized to both nuclei of a trophozoite is shown. p4F11 was unique among the probes in that only one nucleus was labeled in approximately 30 to 40% of trophozoites instead of the 10% seen with other probes. (C) Dual-color FISH with two chromosome 4 probes. (C1) β-Giardin with a fluorescein label; (C2) GDH with a Cy3 label. For a majority of the trophozoites, both nuclei were labeled. The arrows identify two trophozoites in which β-giardin labeled both nuclei, while GDH labeled only one. This pattern was seen in about 10% of the trophozoites and showed no probe preference.

Single-color hybridization with single-copy probes.

In order to determine whether the two nuclei had similar or different complements of DNA, probes were chosen from each of the five chromosomes of G. lamblia as determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis hybridization (5) (Table 1). One or two probes from each chromosome have previously been shown to be present as single copies in the Giardia genome (5), and the remainder have been verified as chromosome-specific probes by their hybridization to a single chromosome on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis chromosomal separations (data not shown). The trophozoite morphology is demonstrated in Fig. 4 with an intentional overexposure using the actin probe.

For all of the probes, with the exception of p4F11 from chromosome 1 (discussed below), the results were similar (Fig. 3). Most of the trophozoites contained signals in both nuclei, while in approximately 10% of trophozoites, only one nucleus was labeled (Fig. 3). There were always some trophozoites that were not labeled, although the YoYo-1 stain showed a normal nuclear morphology. These results indicate that multiple probes specific for each of the five chromosomes hybridize to each of the two nuclei and indicate that in most cells each of the two nuclei contains a complete genome.

Dual-color hybridization with single copy probes.

The occasional failure of one or both nuclei to be labeled has several possible explanations which can be distinguished by the use of dual-color hybridization. (i) All the copies of an entire chromosome may be deleted from one nucleus. In this case, hybridization with two probes from the same chromosome would give similar results, while probes from different chromosomes may give discordant results. (ii) A subchromosomal deletion may result in the loss of a portion of a chromosome from one nucleus. In this case, discordant results may be seen with probes from the same chromosome. (iii) The permeabilization of the nuclei may be incomplete, leaving nuclei that were inadequately permeabilized to allow probe entry. In this case, concordant results would be expected with probes from the same or different chromosomes.

For the dual-color hybridizations, one probe was labeled with biotin and developed with streptavidin, while the other was labeled with fluorescein and developed with antifluorescein antibody. The two chromosome 4 probes, GDH and β-giardin, gave similar results (Fig. 4C). GDH is on a telomeric 260-kb NotI fragment, while β-giardin is on a nontelomeric NotI fragment (data not shown). None of the genotype A-1 organisms (including ISR) have significant size variation of chromosome 4. Most cells had both nuclei labeled with both probes; fewer than 10% had only one nucleus labeled with one probe, while the other probe labeled both nuclei. The pattern was no more common for one probe than for the other, suggesting that the occasional failure to detect a gene on chromosome 4 is an artifact (Fig. 4C).

Since p4F11 labeled only one nucleus in 30 to 40% of trophozoites instead of the 10% frequency found with other probes in single-color FISH, this raised the possibility that part or all of chromosome 1 had been lost in one of the nuclei. Therefore, a quantitative comparison of the hybridization patterns of the two chromosome 1 probes was performed using dual-color hybridization with two chromosome 1 probes followed by epifluorescence (not shown) or confocal microscopy (Fig. 4A and B). The frequency of hybridization to a single nucleus was higher for the more telomeric p4F11 (34 to 50%) than for p5D2 (8 to 12%). In order to see if this pattern persisted in a true clonal population, ISRE11 trophozoites (previously cloned twice by limiting dilution [5]) were again cloned twice by limiting dilution. Of the first-round clones, p4F11 labeled both nuclei in 50 to 66% of organisms. Three second-round clones derived from a first-round clone in which both nuclei were labeled in 62% of trophozoites had both nuclei labeled by p4F11 in 52 to 60% of both trophozoites, compared to 82 to 92% for the p5D2 probe. The ISR isolate is notable for substantial chromosome size variation of chromosome 1 (5), but the WB isolate demonstrates no detectable chromosome 1 size variation. Therefore, p4F11 and p5D2 labeling of the WB isolate were performed. Interestingly, the results were similar to those of the ISR isolate, with labeling of both nuclei in 64% of trophozoites with the p4F11 probe and 84% of trophozoites with the p5D2 probe. This finding was unique to the p4F11 probe and did not correlate with chromosome size variability. Our data suggest that p4F11 detects a chromosomal region near the telomere that undergoes frequent reorganization in both WB and ISR. Reorganization of a subtelomeric region containing the p4F11 sequence has been documented in ISR (2), and this reorganization results in substantial changes in chromosome size. It is possible that smaller-scale rearrangements in the same general area occur in WB.

DISCUSSION

G. lamblia trophozoites reproduce by fission. It has generally been assumed that reproduction is asexual, with the nuclei undergoing mitosis. This assumption is based on the lack of direct evidence for sexual reproduction and on population genetic studies showing that the reproduction is mainly clonal (8, 26). It has also been assumed on the basis of light microscopic studies done by Filice (13) that the daughter nuclei are partitioned equationally, with each daughter cell getting one copy of each nucleus, and that they divide in such a way as to maintain their left-right (dorsal-ventral) asymmetry.

However, these assumptions regarding the mode of replication have been called into question by recent observations. First, it has become clear that G. lamblia has a very low level of allelic sequence heterozygosity (ASH) despite being polyploid (4). The polyploidy has been demonstrated by a variety of observations. These include the identification of at least three or four size variants of chromosome 1 (2, 5, 14) and identification of three or four alleles of repeat-containing vsp genes on chromosomes 4 (29) and 5 (30). Quantitative data have suggested an even higher ploidy of at least eight (see reference 3). Recent fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis using Escherichia coli as a standard for comparison has provided a possible explanation by suggesting that G1 trophozoites are tetraploid (10) but that the trophozoites spend most of their time in G2. However, none of these studies have addressed the distribution of the chromosomes between the two nuclei. Although previous work using in situ hybridization had shown that each nucleus contained rRNA genes (15), these genes are variably distributed among the chromosomes (6), and the techniques available for that study were not sensitive enough to allow the identification of single copy probes.

If each nucleus contains at least one copy of each chromosome and gene, asexually dividing trophozoites would be expected to accumulate substantial ASH between nuclei, and also within nuclei, if mitotic recombination failed to eliminate it as in the bdelloid rotifers (27). In contrast to these predictions, no ASH was detected in more than 6.5 kb of sequence for the tim gene from seven genotype A-1 (Nash group 1) isolates (9), for an overall ASH level that is less than 0.1%. In addition, the level of ASH identified as part of the Giardia genome project (18) is strikingly low (unpublished data).

The low level of ASH would be explained if each nucleus contained a different genome (different set of chromosomes). Therefore, we used multiple probes specific to each of the five chromosomes to determine whether each of the chromosomes is present in one or both nuclei. The results show that at least one copy of each chromosome was present in each nucleus, at least for the majority of trophozoites. If trophozoites are tetraploid in G1, the simplest interpretation is that each nucleus is diploid. However, other work using FISH has also indicated that at least one copy of each chromosome is present in each nucleus, but this work suggested a 3:1 distribution of at least some of the chromosomes between the two nuclei (Frisardi and Samuelson, 11th Woods Hole Mol. Parasitol. Meet.). The present work does not confirm or refute the suggestion that the chromosomes are asymmetrically distributed.

The second question we have addressed in the present work is whether nuclear segregation is reductional or equational. Reductional division would have partitioned both left nuclei to one daughter and both right nuclei to the other and would eliminate all sequence differences between nuclei at each division. Also, any nuclear asymmetry would be completely resolved with each round of replication. Our studies demonstrated that a transfected plasmid remains in one nucleus even after 1 year of continuous in vitro growth (approximately 1,000 generations), proving equational division.

Equational division could be ventral-dorsal (Fig. 1), as suggested by the work of Filice (13), or ventral-ventral (mirror), as suggested by Frisardi and Samuelson (11th Woods Hole Mol. Parasitol. Meet.). Our data suggest that cytokinesis is dorsal-ventral rather than dorsal-dorsal or ventral-ventral (Fig. 1). Dorsal-ventral cell division should maintain left-right asymmetry for each generation, while dorsal-dorsal or ventral-ventral division would reverse the left-right asymmetry each generation. Therefore, a probe transfected into a nucleus would reverse sides with each generation and a population of transfected trophozoites should all be labeled in a single nucleus, but half of them would be labeled in the left nucleus and half of them would be labeled in the right nucleus, regardless of the original transfected nucleus. We found that the majority of trophozoites in a transfected clone have the plasmid in the same nucleus, left in some clones and right in others, and that the proportion of cells with the plasmid in the opposite nucleus is the same as the proportion of trophozoites adhered by their dorsal side. This is good evidence in favor of dorsal-ventral replication that maintains the left-right asymmetry.

Our data have ruled out two causes of the very-low heterokaryosity in Giardia. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of reductional partitioning or nondisjunction of nuclei that is too infrequent to be detected in our experiments but frequent enough to maintain homokaryosity. Sexual reproduction with inbreeding might also explain homokaryosity and also homozygosity. Sexual reproduction has never been detected in Giardia but might not be detectable if it is rare, if it requires cells from two different clones, or if sexual stages are difficult to identify by morphology. Our study does not address the maintenance of homozygosity within a nucleus that contains two or more copies of a chromosome; this might involve mitotic recombination, nondisjunction, sexual reproduction with inbreeding, or more exotic phenomena.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

After this paper was accepted, material from the abstract cited in the text as suggesting a mirror image (ventral:ventral) cell division (M. Frisardi and J. Samuelson, 11th Woods Hole Molecular Parasitology Meeting, abstr. 202C, 2000) was published (S. Ghosh, M. Frisardi, R. Rogers, and J. Samuelson, Infect. Immun. 69:7866-7872, 2001). In that report, FISH of a single clone of trophozoites transfected with a plasmid showed an approximately 50:50 ratio of cells labeled in the left and right nucleus. The difference between those results and ours might be explained if fixed cells in that study adhered to the slide by dorsal and ventral surfaces equally frequently. It should be noted that both studies confirm equational rather than reductional division.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ted Nash for providing the 5′Δ5n-pac plasmid and Lynda Schurig for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the Flinn Foundation to the Genetics Interdisciplinary Program at the University of Arizona. The Giardia genome project (supported by NIH grant RO1AI43273) is acknowledged for providing many of the clones used as probes in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam, R. D. 1991. The biology of Giardia spp. Microbiol. Rev. 55:706-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam, R. D. 1992. Chromosome-size variation in Giardia lamblia: the role of rDNA repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3057-3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam, R. D. 2000. The Giardia lamblia genome. Int. J. Parasitol. 30:475-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam, R. D. 2001. Biology of Giardia lamblia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:447-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam, R. D., T. E. Nash, and T. E. Wellems. 1988. The Giardia lamblia trophozoite contains sets of closely related chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:4555-4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adam, R. D., T. E. Nash, and T. E. Wellems. 1991. Telomeric location of Giardia rDNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3326-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggarwal, A., R. D. Adam, and T. E. Nash. 1989. Characterization of a 29.4-kilodalton structural protein of Giardia lamblia and localization to the ventral disk. Infect. Immun. 57:1305-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala, F. J. 1998. Is sex better? Parasites say “no.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3346-3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baruch, A. C., J. Isaac-Renton, and R. D. Adam. 1996. The molecular epidemiology of Giardia lamblia: a sequence-based approach. J. Infect. Dis. 174:233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernander, R., J. E. Palm, and S. G. Svärd. 2001. Genome ploidy in different stages of the Giardia lamblia life cycle. Cell. Microbiol. 3:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birky, C. W., Jr. 1996. Heterozygosity, heteromorphy, and phylogenetic trees in asexual eukaryotes. Genetics 144:427-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boothroyd, J. C., A. Wang, D. A. Campbell, and C. C. Wang. 1987. An unusually compact ribosomal DNA repeat in the protozoan Giardia lamblia. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:4065-4084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filice, F. P. 1952. Studies on the cytology and life history of a Giardia from the laboratory rat. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 57:53-146. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou, G., S. M. Le Blancq, E. Yaping, H. Zhu, and M. G. Lee. 1995. Structure of a frequently rearranged rRNA-encoding chromosome in Giardia lamblia. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:3310-3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabnick, K. S., and D. A. Peattie. 1990. In situ analyses reveal that the two nuclei of Giardia lamblia are equivalent. J. Cell Sci. 95:353-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keister, D. B. 1983. Axenic culture of Giardia lamblia in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with bile. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77:487-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Blancq, S. M., and R. D. Adam. 1998. Structural basis of karyotype heterogeneity in Giardia lamblia. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 97:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McArthur, A. G., H. G. Morrison, J. E. J. Nixon, N. Q. E. Passamaneck, U. Kim, G. Hinkle, M. K. Crocker, M. E. Holder, R. Farr, C. I. Reich, G. E. Olsen, S. B. Aley, R. D. Adam, F. D. Gillin, and M. L. Sogin. 2000. The Giardia genome project database. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189:271-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mowatt, M. R., E. C. Weinbach, T. C. Howard, and T. E. Nash. 1994. Complementation of an Escherichia coli glycolysis mutant by Giardia lamblia triosephosphate isomerase. Exp. Parasitol. 78:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nash, T. E., A. Aggarwal, R. D. Adam, J. T. Conrad, and J. W. Merritt, Jr. 1988. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia. J. Immunol. 141:636-641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nash, T. E., T. McCutchan, D. Keister, J. B. Dame, J. D. Conrad, and F. D. Gillin. 1985. Restriction-endonuclease analysis of DNA from 15 Giardia isolates obtained from humans and animals. J. Infect. Dis. 152:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachidanandam, R., D. Weissman, S. C. Schmidt, J. M. Kakol, L. D. Stein, G. Marth, S. Sherry, and J. C. Mullikin. 2001. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409:928-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer, S. M., J. Yee, and T. E. Nash. 1998. Episomal and integrated maintenance of foreign DNA in Giardia lamblia. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 92:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith, P. D., F. D. Gillin, N. A. Kaushal, and T. E. Nash. 1982. Antigenic analysis of Giardia lamblia from Afghanistan, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, and Oregon. Infect. Immun. 36:714-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sogin, M. L., J. H. Gunderson, H. J. Elwood, R. A. Alonso, and D. A. Peattie. 1989. Phylogenetic meaning of the kingdom concept: an unusual ribosomal RNA from Giardia lamblia. Science 243:75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tibayrenc, M., F. Kjellberg, J. Arnaud, B. Oury, S. F. Breniëre, M. L. Dardë, and F. J. Ayala. 1991. Are eukaryotic microorganisms clonal or sexual? A population genetics vantage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5129-5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welch, D. M., and M. Meselson. 2000. Evidence for the evolution of bdelloid rotifers without sexual reproduction or genetic exchange. Science 288:1211-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiesehahn, G. P., E. L. Jarroll, D. G. Lindmark, E. A. Meyer, and L. M. Hallick. 1984. Giardia lamblia: autoradiographic analysis of nuclear replication. Exp. Parasitol. 58:94-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang, Y. M., and R. D. Adam. 1994. Allele-specific expression of a variant-specific surface protein (VSP) of Giardia lamblia. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:2102-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang, Y. M., Y. Ortega, C. Sterling, and R. D. Adam. 1994. Giardia lamblia trophozoites contain multiple alleles of a variant-specific surface protein gene with 105-base pair tandem repeats. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 68:267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yee, J., and P. P. Dennis. 1992. Isolation and characterization of a NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase gene from the primitive eucaryote Giardia lamblia. J. Biol. Chem. 267:7539-7544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]