ABSTRACT

Managing acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with thrombocytopenia is challenging. We used data from the RIETE registry to investigate the impact of baseline thrombocytopenia on early VTE‐related outcomes, depending on the initial presentation as pulmonary embolism (PE) or isolated lower‐limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT). From March 2003 to November 2022, 90 418 patients with VTE were included. Thrombocytopenia was categorized as severe (< 50 000/μL, n = 303) or moderate (50 000–99 999/μL, n = 1882). The primary outcome, fatal PE within 15 days after diagnosis, and secondary outcomes, including major bleeding and recurrent VTE, were analyzed using multivariable‐adjusted models. Among 52 703 patients with PE, the 15‐day case‐fatality rates from PE were 5.8% for severe thrombocytopenia, 4.5% for moderate thrombocytopenia, and 1.1% for normal platelet counts. In 37 715 patients with isolated DVT, the cumulative incidence of fatal PE were 0, 0.2%, and 0.05%, respectively. Multivariable analysis revealed a five‐fold increase in the risk for fatal PE in severe thrombocytopenia (adjusted HR: 4.89; 95%CI: 2.55–9.39) without significant differences between severe and moderate thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia, either moderate or severe, was also associated with increased risk for both, major bleeding and recurrent VTE at 15 days. Initial presentation with PE substantially worsened prognosis compared to isolated DVT. In conclusion, in patients with acute VTE, thrombocytopenia at baseline was associated with increased risk of early death from PE, a finding that was driven by the subgroup whose initial presentation was PE.

1. Introduction

The occurrence of a venous thromboembolism (VTE) event among patients with thrombocytopenia is not uncommon, particularly in the setting of cancer [1, 2]. While for the general population VTE management in clinical practice is well‐established, with clear guidelines guiding treatment decisions, however, a substantial gap exists when it comes to addressing VTE in patients with thrombocytopenia [3, 4, 5, 6]. Actually, these patients are frequently excluded from randomized clinical trials, which constitute the gold standard for establishing treatment guidelines. This exclusion, justified by prioritizing patient safety, leaves clinicians with a significant dilemma when facing VTE patients presenting with thrombocytopenia [7]. As a result, the optimal approach to managing VTE in this vulnerable population remains an uncharted territory within the realm of evidence‐based medicine.

This study used routine practice data from the RIETE (Registro Informatizado Enfermedad TromboEmbólica) registry, the world's largest registry of VTE patients, to explore how thrombocytopenia impacts the early incidence of fatal pulmonary embolism (PE), VTE recurrences, and major bleeding events depending on the initial presentation, either as isolated lower‐limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or as PE. Our findings aim to enhance the decision‐making process for clinicians treating VTE in patients with thrombocytopenia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The RIETE registry, an ongoing international project, enrolls consecutive unselected patients with objectively confirmed acute VTE. Originally launched in Spain in March 2001, RIETE currently includes 207 active centers in 28 countries from Europe, North‐ and South America, Asia, and Africa. Details about the methodology of RIETE have been described elsewhere [8, 9]. This study adheres to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

2.2. Patients

The study included consecutive adult (≥ 18 years‐old) patients diagnosed with symptomatic DVT or PE, confirmed by objective imaging tests. Patients were managed according to the clinical practice of each participating hospital, without standardization. Patients were excluded in case of participation in a therapeutic clinical trial with a blinded therapy. All participants gave informed consent in accordance with local ethics committee requirements. After VTE diagnosis, all patients were monitored for a minimum of 3 months via hospital visits or telephone interviews to assess for signs or symptoms of VTE recurrence or major bleeding, as well as to document anticoagulant therapy details. Only patients initially presenting with PE and/or DVT in the lower limbs were considered for this study.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome was fatal PE within 15 days of diagnosis. Secondary outcomes were VTE recurrences, major bleeding, and all‐cause mortality. Thrombocytopenia was categorized as severe (< 50 000/μL) or moderate (50 000–99 999/μL), with the comparison group comprising patients with normal platelet counts (≥ 100 000/μL). Clinically suspected VTE recurrences were confirmed by repeat imaging. Bleeding was considered as major if it was overt and required a transfusion of two or more units of blood, involved a critical site (retroperitoneal, spinal, or intracranial), or was fatal. This definition closely resembles that of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) for major bleeding [10], although the RIETE definition preceded the ISTH definition. Fatal PE, in the absence of autopsy, was defined as any death appearing < 10 days after PE diagnosis (either the index PE or recurrent PE), in the absence of any alternative cause of death. Fatal bleeding was defined as any death occurring < 10 days after a major bleeding episode, in the absence of an alternative cause of death.

2.4. Data Elements

Variables routinely collected in RIETE included baseline characteristics, VTE presentation, risk factors for VTE, comorbidities, blood tests at baseline, concomitant therapies, and treatment of the VTE event (including anticoagulant type, dose, and duration). For this study, the initial anticoagulant treatment was considered as ‘reduced doses’ if the daily dose administered was lower than 130 IU/Kg of enoxaparin, 170 IU/Kg of tinzaparin, 100 IU/Kg of bemiparin, 150 IU/kg of dalteparin, 15 mg/12 h of rivaroxaban, 10 mg/12 h of apixaban. As RIETE is an observational study, the therapeutic management may vary according to the decision by the treating clinician.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables were presented as percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviation or medians with interquartile ranges for non‐normally distributed data. Comparison of categorical variables was performed using the Chi squared test, while the analysis of variance test (ANOVA) was applied for continuous variables. For the comparison of baseline characteristics between the three groups, the group with normal platelet count was used as the reference group and the standardized difference of means/proportions was calculated, considering a difference greater than 10% as clinically relevant. Cumulative incidences with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each outcome. To address potential data clustering and capture variability across different data levels, multilevel analysis was conducted. Binary outcomes (mortality) were modeled using mixed effects survival models that account for data's nested structure and confounding factors. Cox proportional hazard models, incorporating the Fine‐Gray method for competing risks, were used to assess standardized hazard ratios of VTE recurrences or major bleeding, considering death not due to major bleeding nor recurrent PE as competing risks. Fatal PE was analyzed using a Fine‐Gray method, with non‐PE death as the competing risk. Covariates for the adjusted model were selected based on a priori clinical interest and a statistically significance, with a p value threshold of 0.1. Additionally, a mediation analysis was performed to determine the proportion of outcomes attributable to treatment, factoring thrombocytopenia severity (independent variable), 15‐day outcomes (dependent variable), and treatment intensity (mediating variable). A p value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using SPSS software (version 20, SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, United States) and Stata MP v.15.1 (Stata Corp, Texas, United States).

3. Results

A comprehensive evaluation of 90 418 patients with VTE, recruited in RIETE from March 2003 through November 2022, was conducted. Acute PE, with or without accompanying DVT, was the initial presentation in 52 703 patients (58%), while 37 715 subjects (42%) presented with isolated lower‐limb DVT.

3.1. Thrombocytopenia and Patients' Characteristics

Baseline thrombocytopenia was identified in 2.4% of the whole cohort, including 303 patients (0.3%) with severe thrombocytopenia (61 of them had a platelet count < 25 000/μL) and 1882 patients (2.1%) with moderate thrombocytopenia. Patients with severe thrombocytopenia were less likely to present with PE (51% vs. 58%) and more often had active cancer, particularly hematologic malignancies, recent major bleeding, anemia, or a history receiving corticosteroids (Table 1). Moderate thrombocytopenia was more common in men, with higher presence of cancer, chronic thrombocytopenia, anemia, and corticosteroid use compared to those with normal platelet counts.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients, according to platelet count at baseline.

| < 50 000/μL | 50 000–99 999/μL | ≥ 100 000/μL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 303 | 1882 | 88 233 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Male sex | 148 (49%) | 1103 (59%) a | 43 459 (49%) |

| Age (mean years±SD) | 64 ± 1 a | 67 ± 15 | 66 ± 17 |

| Body weight (mean kg ± SD) | 72 ± 16 a | 74 ± 16 a | 77 ± 17 |

| Initial VTE presentation | |||

| PE (with or without concomitant DVT) | 156 (51%) a | 1045 (56%) | 51 502 (58%) |

| Isolated DVT | 147 (49%) a | 837 (44%) | 36 731 (42%) |

| Heart rate > 100 bpm | 85 (28%) a | 439 (23%) | 17 522 (20%) |

| Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg | 20 (6.9%) a | 92 (5.1%) a | 1936 (2.3%) |

| Additional risk factors for VTE | |||

| Active cancer | 157 (52%) a | 703 (37%) a | 14 169 (16%) |

| Recent surgery | 34 (11%) | 143 (7.6%) a | 9387 (11%) |

| Recent immobility ≥ 4 days | 77 (25%) a | 460 (24%) a | 20 158 (23%) |

| Estrogen use | 9 (3.0%) a | 61 (3.2%) a | 49 491 (5.7%) |

| Pregnancy or postpartum | 1 (0.3%) a | 10 (0.5%) | 1021 (1.2%) |

| None of the above | 83 (27%) a | 763 (40%) a | 45 198 (51%) |

| Prior VTE | 43 (14%) | 251 (13%) | 13 227 (15%) |

| Underlying conditions | |||

| Chronic thrombocytopenia | 29 (9.6%) a | 88 (4.7%) a | 143 (0.2%) |

| Chronic liver disease | 19 (6.3%) a | 135 (7.2%) a | 869 (1.0%) |

| Recent (< 30 days) major bleeding | 21 (6.9%) a | 67 (3.6%) | 1964 (2.2%) |

| HIV infection | 3 (1.0%) | 13 (0.7%) | 317 (0.4%) |

| Recent COVID‐19 infection | 6 (2.0%) | 40 (2.1%) | 2710 (3.1%) |

| Blood tests | |||

| Anemia | 218 (72%) a | 970 (51%) a | 28 797 (33%) |

| Leukocyte count > 11 000/μL | 74 (24%) | 419 (22%) a | 23 886 (27%) |

| CrCl levels < 50 mL/min | 80 (26%) | 519 (28%) a | 19 428 (22%) |

| Concomitant drugs | |||

| Corticosteroids | 75 (25%) a | 393 (21%) a | 7103 (8.1%) |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 8 (2.6%) | 76 (4.0%) | 3325 (3,8%) |

| Among patients with cancer, N | 157 | 703 | 14 169 |

| Metastases | 90 (57%) | 430 (61%) a | 7689 (54%) |

| Site of cancer | |||

| Genitourinary | 36 (23%) | 143 (20%) | 3686 (26%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 15 (9.6%) a | 101 (14%) a | 2754 (19%) |

| Breast | 7 (4.5%) a | 51 (7.3%) a | 1804 (13%) |

| Lung | 26 (17%) | 145 (21%) a | 2342 (16%) |

| Hematologic | 40 (25%) a | 98 (14%) a | 920 (6.5%) |

| Pancreas | 8 (5.1%) | 41 (5.8%) | 724 (5.1%) |

| Cerebral | 6 (3.8%) | 41 (5.8%) | 581 (4.1%) |

| Other sites | 19 (12%) | 83 (12%) | 1358 (9.6%) |

Abbreviations: CrCl, creatinine clearance; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PE, pulmonary embolism; SD, standard deviation; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Standardized difference of means/proportions > 10% (as compared to the group ≥ 100.000 platelets/μL).

3.2. Therapeutic Interventions

Treatment approaches varied, reflecting the complexity of this clinical scenario (Table S1). Low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) was used as initial therapy in a majority of patients, but those with thrombocytopenia more often received unfractionated heparin (UFH) than patients with normal platelet counts. Among patients treated with LMWH, the use of reduced doses was more frequent in those with thrombocytopenia, reaching 45% of subjects with severe thrombocytopenia who presented as isolated DVT.

Of note, one in every 10 patients with severe thrombocytopenia, and one in every five with platelet counts below 25 000/μL, did not receive initial anticoagulant therapy. Among those patients with severe thrombocytopenia who were not treated, 35% had platelet counts under 25 000/μL. Instead, they more likely underwent nonpharmacological thrombolysis/thrombectomy or underwent a vena cava filter placement, particularly if presenting as PE.

3.3. Outcomes

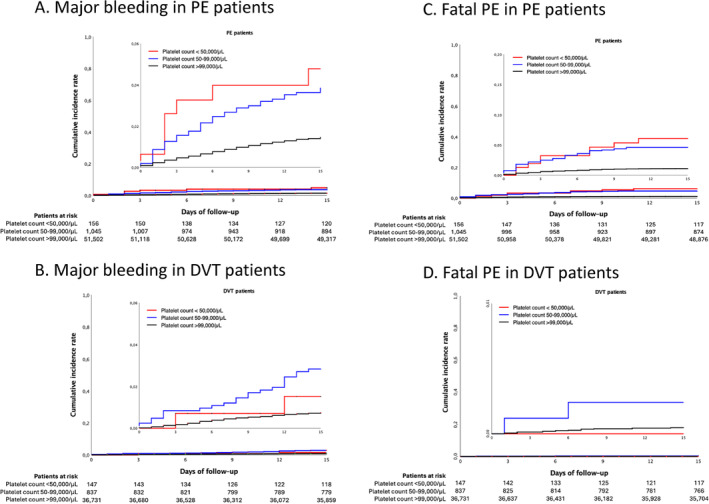

Among patients presenting with PE, those with severe thrombocytopenia had a cumulative incidence of fatal PE of 5.8% within the first 15 days after diagnosis, as compared to 4.5% in patients with moderate thrombocytopenia, and 1.1% in those with normal platelet counts (Table 2). A similar pattern was observed in major bleeding events, with cumulative incidence of 4.5%, 3.6%, and 1.4%, respectively (Figure 1). The incidence of recurrent VTE were also more frequent among patients with thrombocytopenia: 2.6%, 1.1%, and 0.4%, respectively (Figure S1).

TABLE 2.

Fifteen‐day outcomes according to platelet count at baseline and initial VTE presentation.

| Pulmonary embolism | Isolated deep vein thrombosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 50 000/μL | 50 000–99 999/μL | ≥ 100 000/μL | < 50 000/μL | 50 000–99 999/μL | ≥ 100 000/μL | |

| Patients, N | 156 | 1045 | 51 502 | 147 | 837 | 36 731 |

| Recurrent VTE | 4 (2.6%)*** | 12 (1.1%)** | 231 (0.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 7 (0.8%) | 219 (0.6%) |

| Recurrent PE | 4 (2.6%)*** | 8 (0.8%)* | 171 (0.3%) | 0 | 4 (0.5%) | 112 (0.3%) |

| Recurrent DVT | 0 | 4 (0.4%)* | 60 (0.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (0.4%) | 107 (0.3%) |

| Major bleeding | 7 (4.5%)** | 38 (3.6%)*** | 735 (1.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 23 (2.7%)*** | 274 (0.7%) |

| Sites of bleeding | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 5 (3.2%)*** | 11 (1.1%)*** | 189 (0.4%) | 0 | 10 (1.2%)*** | 103 (0.3%) |

| Hematoma | 0 | 9 (0.9%)* | 222 (0.4%) | 0 | 5 (0.6%)* | 78 (0.2%) |

| Intracranial | 0 | 5 (0.5%)* | 82 (0.2%) | 1 (0.7%)** | 1 (0.1%) | 21 (0.1%) |

| Retroperitoneal | 1 (0.6%) | 5 (0.5%)* | 81 (0.2%) | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 29 (0.1%) |

| Death | 31 (20%)*** | 137 (13%)*** | 1614 (3.1%) | 27 (18%)*** | 45 (5.4%)*** | 446 (1.2%) |

| Causes of death | ||||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 9 (5.8%)*** | 47 (4.5%)*** | 571 (1.1%) | 0 | 2 (0.2%)* | 17 (0.05%) |

| Initial PE | 8 (5.1%)*** | 47 (4.5%)*** | 538 (1.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrent PE | 1 (0.6%)** | 0 | 33 (0.1%) | 0 | 2 (0.2%)* | 17 (0.05%) |

| Bleeding | 3 (1.9%)*** | 8 (0.8%)*** | 107 (0.2%) | 1 (0.7%) | 6 (0.7%)*** | 47 (0.1%) |

| Sudden, unexpected | 1 (0.6%)* | 2 (0.2%) | 55 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 20 (0.1%) |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 3 (1.9%)** | 13 (1.2%)*** | 179 (0.3%) | 5 (3.4%)*** | 3 (0.4%)* | 41 (0.1%) |

| Disseminated cancer | 4 (2.6%)*** | 28 (2.7%)*** | 217 (0.4%) | 9 (6.1%)*** | 17 (2.0%)*** | 120 (0.3%) |

Note: Differences between patients with‐ versus without thrombocytopenia.

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

FIGURE 1.

Major bleedings and fatal PE at 15 days according to initial presentation of VTE and baseline platelet count. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In the isolated lower‐limb DVT group, the rates of fatal PE at 15 days were low across all platelet count categories (0%, 0.2% and 0.05%, respectively) (Table 2). In addition, major bleeding was significantly more frequent in patients with thrombocytopenia, particularly in those with moderate thrombocytopenia (2.7%) than in those with normal platelet count (0.7%), (Figure 1).

3.4. Multivariable Analysis

Multivariable models confirmed a consistent increase in the risk for fatal PE, major bleeding and recurrent VTE associated with thrombocytopenia, either moderate or severe (Table 3). Severe thrombocytopenia increased the risk for fatal PE by nearly five‐fold (hazard ratio [HR]: 4.89; 95%CI: 2.55–9.39), while moderate thrombocytopenia increased the risk for fatal PE by nearly four‐fold (HR: 3.80; 95%CI: 2.74–5.27), (Figure S2). The effects of moderate and severe baseline thrombocytopenia continued at the 30 day landmark (Tables S2 and S3). Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis that excluded cancer patients yielded results consistent with the overall study population (Table S4).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable analyses for major bleeding, VTE recurrences, fatal PE or all‐cause death within the first 15 days.

| Major bleeding | VTE recurrences | Fatal PE | All‐cause death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial VTE presentation as PE | 1.48 (1.19–1.84)*** | 0.57 (0.43–0.77)*** | 13.97 (8.90–21.93)*** | 2.13 (1.90–2.38)*** |

| Active cancer | 1.57 (1.33–1.85)*** | 2.52 (1.77–3.58)*** | 2.78 (2.17–3.57)*** | 3.68 (3.31–4.08)*** |

| Platelet count | ||||

| > 99 999/μL | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 50 000–99 999/μL | 2.86 (2.21–3.71)*** | 2.16 (1.26–3.69)*** | 3.80 (2.74–5.27)*** | 3.19 (2.63–3.87)*** |

| < 50 000/μL | 2.62 (1.18–5.81)*** | 3.60 (1.65–7.87)*** | 4.89 (2.55–9.39)*** | 4.74 (3.25–6.90)*** |

| Anticoagulant treatment doses | ||||

| Full doses | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Reduced doses | 0.65 (0.42–1.03) | 1.01 (0.71–1.45) | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 1.44 (1.26–1.64)*** |

| No treatment | 0.90 (0.72–1.14) | 9.43 (2.68–33.20)*** | 6.92 (2.09–22.89)*** | 3.98 (2.95–5.36)*** |

| Interruption of AC therapy ≥ 2 days | 0.63 (0.38–1.03) | 1.48 (0.76–2.89) | 1.71 (0.98–2.98) | 2.96 (2.36–3.71)*** |

Note: Multivariable analyses for major bleeding, VTE recurrences and Fatal PE were performed with competing risks for death. Results are expressed as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

Abbreviations: AC, anticoagulation; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Patients presenting with PE were at increased risk for fatal PE (HR: 13.97; 95%CI: 8.90–21.93), all‐cause death (HR: 2.13; 95%CI: 1.90–2.38), and major bleeding (HR: 1.48; 95%CI: 1.19–1.84), but had a lower risk for recurrent VTE (HR: 0.57; 95%CI: 0.43–0.77).

The use of reduced doses of anticoagulants as initial therapy did not significantly impact the risk of fatal PE, major bleeding, or recurrent VTE. Also, mediation analysis showed minimal impact of the intensity of treatment on the different outcomes (less than 4.0% in all cases). However, patients who did not receive anticoagulants had higher risks for fatal PE (HR: 6.92; 95%CI: 2.09–22.89) and VTE recurrences (HR: 9.43; 95%CI: 2.68–33.20). Treatment interruption for two or more consecutive days, not due to an adverse event, was associated with a marginally lower major bleeding risk (HR: 0.63; 95%CI: 0.38–1.03), and a higher risk for fatal PE (HR: 1.71; 95%CI: 0.98–2.98), without significant changes in recurrent VTE (HR: 1.48; 95%CI: 0.76–2.89) (Table 3).

In a subgroup analysis focusing only on patients with thrombocytopenia, no significant outcome differences emerged between moderate and severe thrombocytopenia groups, except for all‐cause death (Table S5). Reduced anticoagulant doses did not significantly impact fatal PE, recurrent VTE, or major bleeding at 15 days. Both, the absence of anticoagulation use and transient interruption of anticoagulant therapy for over 2 days were associated with a lower risk for major bleeding but increased risk for fatal PE, without significantly modifying the risk of recurrent VTE. An additional analysis comparing patients with < 25 000 platelets/μL with those with 25 000–50 000/μL showed no significant differences in study outcomes, although the limited number of events restricted this assessment (Table S6).

4. Discussion

Our comprehensive analysis of VTE outcomes in patients with thrombocytopenia provides significant insights that challenge and expand upon the existing paradigms of VTE management. The heightened risk of early fatal PE, major bleeding, and recurrent VTE in patients with baseline thrombocytopenia, especially in those presenting with acute PE, emphasizes the need for a nuanced approach to their care. Current guidelines generally suggest conservative management strategies, particularly in patients with severe thrombocytopenia, focused on reducing bleeding risks. However, our data suggest that such strategies might need to be carefully balanced with the risk of thrombotic events. In our study, PE patients had significantly worse outcomes in the presence of thrombocytopenia than those presenting with isolated DVT. This was particularly notable in the marked differences in fatality and major bleeding rates, suggesting that the physiological burden of PE exacerbates the risks imposed by thrombocytopenia. On the other hand, the higher risk of bleeding could also be related with a more intense anticoagulant therapy compared to patients with isolated DVT. For patients presenting with PE, there might be a need to prioritize interventions that allow a rapid stabilization and thorough monitoring. In contrast, the impact of thrombocytopenia was less pronounced in DVT patients, justifying a distinct management strategy for PE versus isolated DVT [11, 12]. DVT patients might benefit from a more conservative approach, focusing on preventing progression and recurrence of thrombosis while minimizing bleeding risks.

Our findings not only reveal the influence of initial VTE presentation on outcomes but also show an unexpected similarity in the risk profiles between severe and moderate thrombocytopenia. Traditionally, severe thrombocytopenia has been associated with a higher risk of bleeding and adverse outcomes [7]. However, our study shows that moderate thrombocytopenia poses similar risks of fatal PE, major bleeding, and recurrent VTE. This finding challenges existing perceptions and suggests that the threshold for high‐risk thrombocytopenia may need reevaluation. In patients with chemotherapy‐induced thrombocytopenia, the platelet count may further decrease in the following days. Consequently, moderate thrombocytopenia might signal impending lower counts. On the other hand, despite adjustments, thrombocytopenia at any level may simply indicate overall patient severity. Nevertheless, our results indicate that even moderate reductions in platelet count can be clinically significant and warrant active management similar to those with severe thrombocytopenia.

Indeed, tailoring treatment to individual patient profiles is crucial. Factors such as the initial VTE presentation, the severity of thrombocytopenia, the presence of active cancer, or previous bleeding history should influence therapeutic decisions. This approach requires integrating a multidisciplinary team to design a treatment plan that considers all aspects of a patient's health status.

Prior studies with heterogeneous designs have largely focused on cancer‐associated thrombocytopenia, where the risk of bleeding is often deemed to overshadow the thrombotic risks, showing mixed outcomes with varied anticoagulant strategies [13, 14, 15]. A recent systematic review, including 707 patients, also showed high rates of recurrent VTE and major bleeding, regardless of the management strategy (full dose anticoagulation, modified dose, or no anticoagulation) [16]. Our findings do not indicate a reduction of the risk of major bleeding with lower‐intensity anticoagulant regimens, although caution is required due to potential uncontrolled confounding factors. In any case, our study extends these previous findings by showing that even in non‐cancer patients, thrombocytopenia represents a significant independent risk factor for adverse VTE outcomes (the effect of cancer as a potential confounder was controlled in the multivariable analysis and a further sensitivity assessment limited to non‐cancer patients confirmed these findings). This aligns with research suggesting that thrombocytopenia should be a key consideration in VTE risk models, which currently do not adequately account for it.

While this study provides a robust data set from a multinational registry, its observational design and the inherent limitations of registry data, including potential reporting biases and variability in treatment across centers, suggest caution in generalizing the findings. The challenge of determining PE as the cause of death in patients with multimorbidities is acknowledged. Moreover, the dynamic nature of platelet counts and their management suggests that a longer follow‐up period may provide additional insights into the chronic management of these patients. Additionally, the effect of platelet transfusions (suggested by some guidelines only in selected patients with severe thrombocytopenia, not in those with moderate thrombocytopenia) remains unassessed. Separate analyses for PE risk stratification and the evaluation of vena cava filters or catheter‐directed therapies were not feasible due to the small number of patients in certain subgroups. Finally, despite multivariable adjustments, unmeasured factors could affect outcomes.

In summary, thrombocytopenia is associated with significantly worse short‐term prognosis for PE patients, less for isolated DVT. The findings of our study underscore the need for a nuanced approach to managing VTE in patients with thrombocytopenia. Moderate thrombocytopenia is not substantially safer than severe thrombocytopenia inviting a paradigm shift in treatment strategies, ensuring that all thrombocytopenic patients receive the vigilant care necessary to mitigate the risks of adverse outcomes.

Author Contributions

R.L., P.R.A., J.T.S., B.B., and M.M. designed the study and analyzed the data. R.L., P.R.A., J.T.S., and M.M. drafted the manuscript. M.M.J., M.P.P., I.Q., G.C., J.G., and B.B. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to SANOFI and ROVI for supporting this Registry with an unrestricted educational grant. We also thank the RIETE Registry Coordinating Center, S&H Medical Science Service, for their quality control data, logistic, and administrative support.

Funding: This work was supported by Sanofi España and Rovi.

A full list of RIETE investigators is given in the Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing statement: For original data, please contact rlecumber@unav.es.

References

- 1. Di Micco P., Ruiz‐Giménez N., Nieto J. A., et al., “Platelet Count and Outcome in Patients With Acute Venous Thromboembolism,” Thrombosis and Haemostasis 110, no. 5 (2013): 1025–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hsu C., Patell R., and Zwicker J. I., “The Prevalence of Thrombocytopenia in Patients With Acute Cancer‐Associated Thrombosis,” Blood Advances 7, no. 17 (2023): 4721–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stevens S. M., Woller S. C., Kreuziger L. B., et al., “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Second Update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report,” Chest 160, no. 6 (2021): e545–e608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ortel T. L., Neumann I., Ageno W., et al., “American Society of Hematology 2020 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism: Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism,” Blood Advances 4, no. 19 (2020): 4693–4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farge D., Frere C., Connors J. M., et al., “2022 International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment and Prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With Cancer, Including Patients With COVID‐19,” Lancet Oncology 23, no. 7 (2022): e334–e347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falanga A., Ay C., Di Nisio M., et al., “Venous Thromboembolism in Cancer Patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline,” Annals of Oncology 34, no. 5 (2023): 452–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Falanga A., Leader A., Ambaglio C., et al., “EHA Guidelines on Management of Antithrombotic Treatments in Thrombocytopenic Patients With Cancer,” Hema 6, no. 8 (2022): e750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lecumberri R., Soler S., Del Toro J., et al., “Effect of the Time of Diagnosis on Outcome in Patients With Acute Venous Thromboembolism. Findings From the RIETE Registry,” Thrombosis and Haemostasis 105, no. 1 (2011): 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lecumberri R., Ruiz‐Artacho P., Tzoran I., et al., “Outcome of Cancer‐Associated Venous Thromboembolism Is More Favorable Among Patients With Hematologic Malignancies Than in Those With Solid Tumors,” Thrombosis and Haemostasis 122, no. 9 (2022): 1594–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schulman S. and Kearon C., “Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of Major Bleeding in Clinical Investigations of Antihemostatic Medicinal Products in Non‐Surgical Patients,” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 3, no. 4 (2005): 692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wenger N., Sebastian T., Engelberger R. P., Kucher N., and Spirk D., “Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis: Similar but Different,” Thrombosis Research 206 (2021): 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lecumberri R., Alfonso A., Jiménez D., et al., “Dynamics of Case‐Fatality Rates of Recurrent Thromboembolism and Major Bleeding in Patients Treated for Venous Thromboembolism,” Thrombosis and Haemostasis 110, no. 4 (2013): 834–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lecumberri R., Ruiz‐Artacho P., Trujillo‐Santos J., et al., “Management and Outcomes of Cancer Patients With Venous Thromboembolism Presenting With Thrombocytopenia,” Thrombosis Research 195 (2020): 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Booth S., HaemSTAR Network , Desborough M., Curry N., and Stanworth S., “Platelet Transfusion and Anticoagulation in Hematological Cancer‐Associated Thrombosis and Thrombocytopenia: The CAVEaT Multicenter Prospective Cohort,” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 20, no. 8 (2022): 1830–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carney B. J., Wang T. F., Ren S., et al., “Anticoagulation in Cancer‐Associated Thromboembolism With Thrombocytopenia: A Prospective, Multicenter Cohort Study,” Blood Advances 5, no. 24 (2021): 5546–5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang T. F., Carrier M., Carney B. J., Kimpton M., and Delluc A., “Anticoagulation Management and Related Outcomes in Patients With Cancer‐Associated Thrombosis and Thrombocytopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Thrombosis Research 227 (2023): 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing statement: For original data, please contact rlecumber@unav.es.