Abstract

To characterize cancer risk in heterozygous p53 mutation carriers, we analyzed cancer incidence in 56 germline p53 mutation carriers and 3,201 noncarriers from 107 kindreds ascertained through patients with childhood soft-tissue sarcoma who were treated at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. We systematically followed members in these kindreds for cancer incidence for >20 years and evaluated their p53 gene status. We found seven kindreds with germline p53 mutations that include both missense and truncation mutation types. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed similar cancer risks between 21 missense and 35 truncation p53 mutation carriers (log-rank χ2=0.04; P=.84). We found a significantly higher cancer risk in female carriers than in male carriers (log-rank χ2=12.1; P<.001), a difference not explained by an excess of sex-specific cancer. The calculated standardized incidence ratio (SIR) showed that mutation carriers had a risk for all types of cancer that was much higher than that for the general population (SIR = 41.1; 95% confidence interval [CI] 29.9–55.0) whereas noncarriers had a risk for all types of cancer that was similar to that in the general population (SIR = 0.9; 95% CI 0.8–1.0). The calculated SIRs showed a >100-fold higher risk of sarcoma, female breast cancer, and hematologic malignancies for the p53 mutation carriers and agreed with the findings of an earlier segregation analysis based on the same cohort. These results quantitatively illustrated the spectrum of cancer risk in germline p53 mutation carriers and will provide valuable reference for the evaluation and treatment of patients with cancer.

Introduction

The tumor-suppressor gene p53 (MIM 191170) plays a central role in tumorigenesis (Levine 1997). Somatic mutation of p53 has been found in >50% of human cancers and is the most common genetic alteration in human neoplasms (Hussain and Harris 1999; Martin et al. 2002). Moreover, germline mutations of p53 have been identified in 50%–70% of families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS [MIM 151623]) (Frebourg et al. 1995; Varley et al. 1997; Bougeard et al. 2001). Germline p53 mutations have been found in ∼1% of patients with early-onset breast cancer and in up to 9% of patients with sarcoma in population-based studies (Iavarone et al. 1992; Malkin et al. 1992; Kyritsis et al. 1994; McIntyre et al. 1994; Diller et al. 1995; Rapakko et al. 2001), and a substantial portion of these carriers had a family history of cancer consistent with LFS (Toguchida et al. 1992; Nichols et al. 2001). Several other studies have showed that p53 mutation carriers had a remarkable risk of developing multiple cancers (McIntyre et al. 1994; Saeki et al. 1997; Hisada et al. 1998).

Most of these studies designed to identify germline p53 mutations, however, were deficient in the recruitment of comparable control individuals and in long-term systematic follow-up and were therefore limited in their ability to further characterize the cancer risks related to germline p53 mutations. We have performed a long-term family study that overcomes these limitations. We have collected cancer-incidence data by following up, for >20 years, 159 extended families identified through 3-year survivors of childhood soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) (Strong and Williams 1987). We have performed p53 mutation analysis in 107 of these 159 kindreds, and we have identified germline p53 mutations in 7 kindreds (Malkin et al. 1990; Law et al. 1991; Shete et al. 2002).

In the present study, we combined the cancer-incidence data for relatives in these 107 kindreds to determine their cancer risk by mutation type and by sex. We then compared the type-specific cancer risk of p53 mutation carriers with that of noncarriers.

Subjects and Methods

Identification of Families and Cancer Incidence

The present study population was composed of blood relatives in 159 extended families identified through 3-year survivors of childhood STS who were diagnosed between 1944 and 1975 at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston). Methods in the identification of families and the recording of cancer incidence have been described elsewhere (Strong and Williams 1987; Bondy et al. 1992; Lustbader et al. 1992). Here, we used medical records and death certificates to verify the reported cancer or cancer-related heath conditions. We defined case subjects with cancer as individuals with any malignant tumor diagnosis except nonmelanoma skin cancer. The cancer incidence was truncated at age 75 years, since the aim of the study was to identify early-onset cancer. As the result of these criteria, the cancer risk of 107 probands and 3,257 relatives, together representing a total of 563 cancer diagnoses, was investigated in the present study.

Subjects were classified as p53 mutation carriers if they had a mutation or if both a parent and an offspring were shown to be mutation carriers. Data for close relatives of mutation carriers whose mutation status was unknown—that is, those with a 50% probability of carrying the germline p53 mutation—were included only in the calculation for standardized incidence ratio (SIR). Subjects were classified as noncarriers if they were probands who did not have a mutation or were relatives from p53 mutation–positive families who could be excluded from carrying a mutation.

Sample Collection and Mutation Testing

Peripheral-blood samples were collected from the probands and relatives after they signed informed consent forms, and the present study has been approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. A total of 107 kindreds were tested for p53 mutations: 92 had only the proband tested, 3 had only affected close relatives tested, and 12 had both the proband and relatives tested. The remaining kindreds could not be tested because of either deceased probands whose relatives were not affected (n=31) or inadequate samples from probands (n=21).

Three of the seven mutations have been described elsewhere (Malkin et al. 1990; Law et al. 1991). Mutations reported here (in families I, II, III, and VI) were identified using a combination of various assays: SSCP for exons 2–11, sequencing of exons 2–11, and the yeast functional assay (Flaman et al. 1995; Evans et al. 1998).

Statistical Analyses

Among the mutation carriers, we tested for risk differences according to both the type of p53 mutation and the carriers’ sex, using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method. Differences in ages at cancer diagnosis between male and female carriers, as well as between those with a truncation versus a missense mutation, were assessed using the log-rank test, for which a P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. We further tested for risk differences by using Cox’s proportional-hazards regression model, to adjust for the potential confounding factors of birth year and race. We used a robust variance procedure to adjust for familial correlation in the proportional-hazards model, which applied the approximate jackknife estimate of variance to adjust for the correlation between onset ages for family members (Lipsitz and Parzen 1996). The time intervals in these regression models were the time between birth and first-cancer diagnosis, for those with cancer, and the time between birth and last contact (December 31, 2001) or death (if before last contact), for those without cancer. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT, version 6.12 (SAS Institute), and SPLUS, version 6 (Data Analysis Products Division).

Mutation carriers’ and noncarriers’ cancer risks were further characterized with the SIR, which was calculated using an updated Monson program called “Cohort Analysis for Genetic Epidemiology” (CAGE). The expected number of cancer cases was calculated on the basis of the study subjects' birth year, age, and sex, to compare with the cancer incidence reported by the Connecticut Tumor Registry. The 95% CI was calculated from a Poisson distribution. A 95% CI excluding 1 was considered as statistically significant. We compared the SIR for the carriers with that for the noncarriers in the study cohort, to minimize variations in the definition of site-specific cancers, especially sarcoma. The SIR was calculated for a total of 18 groups of cancer diagnoses, which included all cancer types for the 45 carriers who developed cancer.

Results

Of the 107 kindreds, 7 (6.6%) harbored a germline p53 mutation (table 1). Six kindreds with p53 mutations had family histories of cancer that are consistent with the classic LFS pattern. The H365Y mutation in kindred II was considered to be de novo because there was no unusual family history of cancer, but no samples from relatives were available for mutation analysis. This mutation has never been reported as a germline mutation but has been reported once as a somatic mutation in a colorectal cancer (Hayes et al. 1999; Hernandez-Boussard et al. 1999). When the 7 probands with p53 mutations were compared with the 100 probands without p53 mutations, there was no difference in the age at initial sarcoma diagnosis or in survival time after STS diagnosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Germline p53 Mutations in Seven Kindreds with STS

| Kindreda (Mutation Site) | Amino AcidChange | No. ofCarriersb | No. ofTumorsc |

| I (exon 8, codon 298) | Glu-Stop | 32 | 33 |

| IId (exon 10, codon 365) | His-Tyr | 1 | 1 |

| III (exon 5, codon 175) | Arg-His | 4 | 11 |

| IV (exon 5, codon 184) | Frameshift | 4 | 10 |

| V (exon 5, codon 133) | Met-Thr | 17 | 20 |

| VIe (intron 9) | … | 2 | 2 |

| VII (exon 7, codon 248) | Arg-Trp | 3 | 5 |

All kindreds except kindred II had family histories of cancer that are consistent with classic LFS.

Confirmed carriers, identified either through direct mutation detection or through inference based on family structure.

Malignant tumors diagnosed in the carriers.

De novo mutation.

Splice mutation in intron 9.

For the seven kindreds with mutations, a total of 63 carriers were identified either through direct mutation detection or through inference based on family structure. A total of 82 malignant tumors were confirmed in 52 of 63 mutation carriers, including probands. Of these tumors, 52 (63%) were associated with classic LFS and included sarcoma (n=28), female breast cancer (n=17), brain tumor (n=3), and leukemia (n=4). Of the remaining tumors, 16 are common adult-onset cancers, such as lung (n=9), colorectal (n=5), and prostate (n=2) cancers. Seventeen carriers eventually developed multiple primary neoplasms. The second malignancies were diagnosed from 3 mo to 33 years (median 9.3 years) after the initial cancer diagnosis. By contrast, among 10 noncarriers who developed a second cancer, the second cancers were diagnosed from 2 years to 34.5 years (median 5.8 years) after first-cancer diagnosis. Although no noncarrier developed a third cancer, a total of seven carriers were diagnosed with a third cancer from 6 mo to 17.7 years after their second-cancer diagnosis. Among these seven, three then developed a fourth cancer, and one proband eventually developed a fifth cancer.

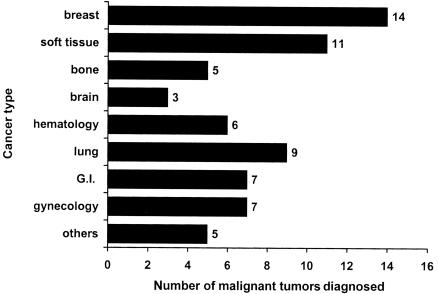

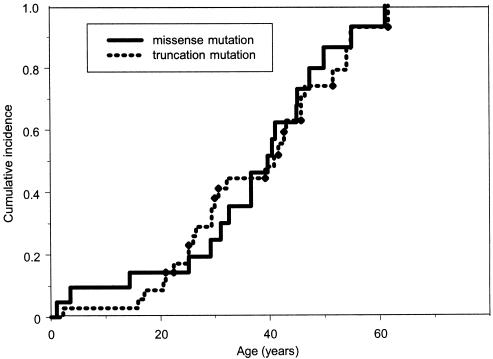

Of the 56 carriers who were not probands, 45 developed a total of 67 malignant tumors, with breast cancer as the most common cancer, followed by STS (fig. 1). Adulthood malignancies, such as lung and colorectal cancer, were relatively common and occurred in an even higher proportion than did osteosarcoma and malignant brain tumor. Among the carriers, 12%, 35%, 52%, and 80% developed cancer by ages 20, 30, 40, and 50 years, respectively, compared with the corresponding cumulative risks of 0.7%, 1.0%, 2.2%, and 5.1% for the 3,201 noncarriers at the same ages. As shown in figure 2, there was no difference in the cumulative cancer risk for all types of cancer (log-rank χ2=0.04, with 1 df; P=.84) between 21 missense and 35 truncation mutation carriers. Similar risk levels were also observed for site-specific cancers between these two groups of carriers (data not shown). For example, a total of 13 carriers developed breast cancer (one carrier had two primary breast cancers); of these 13 carriers, 4 (ages 25 to 46 years) were in the group with missense mutations, and 9 (ages 25 to 52 years) were in the group with truncation mutation (log-rank χ2=0.18, with 1 df; P=.66). Among the 45 carriers who developed cancer, we observed a similar second-cancer risk by mutation type, in 7 of the 18 with a missense mutation and 6 of the 27 with a truncation mutation (log-rank χ2=1.94, with 1 df; P=.16).

Figure 1.

Number of site-specific cancers for 56 germline p53 mutation carriers. Eleven carriers did not have cancer at the time of last contact. A total of 67 malignant neoplasms were diagnosed for the 45 carriers (excluded probands). The “hematology” group comprises four leukemia and two multiple myeloma; the “gynecology” group comprises four ovarian cancers, two prostate cancers, and one testicular cancer; and the “others” group comprises three head and neck tumors, one melanoma, and one thyroid cancer. G.I. = gastrointestinal.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimated cumulative incidence of all types of cancer—in 56 germline p53 mutation carriers (excluding probands) identified in a cohort with childhood sarcoma. Ages shown are the time between birth and first-cancer diagnosis, for those with cancer, and the time between birth and either last contact or death, for those without cancer. Among these 56 carriers, 21 carry missense mutations, and 35 carry truncation mutations.

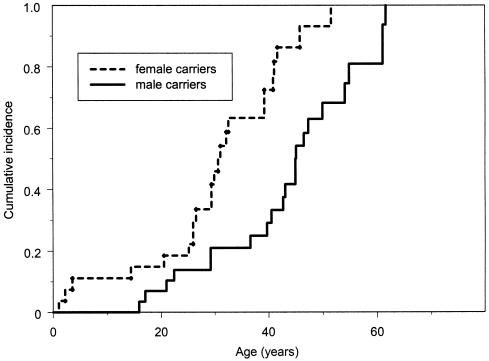

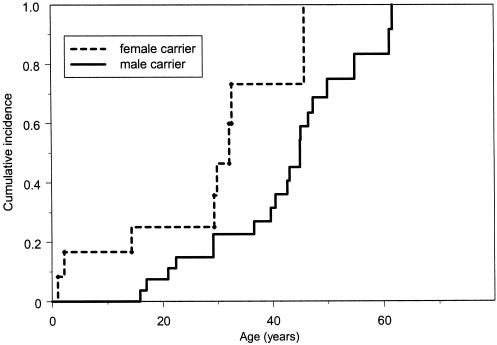

The cancer risk for all carriers was also analyzed by sex. At all ages, female carriers consistently had a higher cancer risk (log-rank χ2=12.1, with 1 df; P<.001). Results of Cox’s proportional-hazards model showed that female carriers had a 2.5-fold higher cancer risk than did male carriers after adjustment for birth year, race, and familial correlation of cancer, as shown in figure 3. Female carriers had an earlier age at first-cancer diagnosis than did male carriers (mean age at diagnosis, 29 vs. 40 years). By ages 20, 30, 40, and 50 years, the female carriers had respective cumulative risks of 18%, 49%, 77%, and 93% for the development of cancer, compared with respective cumulative risks of 10%, 21%, 33%, and 68% in the male carriers at the same ages. The difference in risk was not explained by the high incidence of sex-specific cancer. Results of the Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a consistently higher cancer risk in the female carriers (log-rank χ2=3.7, with 1 df; P=.05), even after the exclusion of cases of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer (fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimated cumulative incidence for all types of cancer—in 27 male and 29 female germline p53 mutation carriers. Ages shown are the time between birth and first-cancer diagnosis, for those with cancer, and the time between birth and either last contact or death, for those without cancer.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimated cumulative incidence for all types of cancer—in 27 male and 12 female germline p53 mutation carriers. Cases of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer were excluded here. Ages shown are the time between birth and first-cancer diagnosis, for those with cancer, and the time between birth and either last contact or death, for those without cancer.

In contrast to p53 mutation carriers, there was no difference in the cancer risk for all types of cancer between male and female noncarriers (1,625 males and 1,576 females) (log-rank χ2=0.62, with 1 df; P=.43). Also different from mutation carriers, the risk for the 3,123 noncarriers after cases of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer were excluded was significantly higher for men (n=1,602) than for women (n=1,521) (log-rank χ2=8.5, with 1 df; P<.003). This difference, however, was due to a higher cancer incidence in the men after age 50 years. For the noncarriers who developed cancer, the second-cancer risk was the same for men and women; however, only 10 of the 324 noncarriers developed a second cancer.

The number of cancer cases in the present group of 3,201 noncarriers was no different from the number expected on the basis of cancer-incidence rates of the Connecticut Tumor Registry. However, in the group that we studied, the noncarriers had a significantly lower risk for colorectal cancer and malignancies of the buccal cavity but a higher risk for STS. The higher STS risk in the noncarriers may have been due to a difference in our definition of STS, since we used the histological typing (instead of site code only) to define STS and osteosarcoma. The mutation carriers had a 41-fold higher risk for all types of cancer relative to that for general population and had a >100-fold higher risk for LFS-component cancers, such as sarcoma, female breast cancer, multiple myeloma, and ovarian cancer (table 2). The risk for mutation carriers who had cancer to develop a second cancer was also higher than that for the general population (SIR=12.3; 95% CI 7.1–19.6). We also determined the SIR for the 92 relatives in the p53 kindreds who had a 50% probability of inheriting a germline p53 mutation, and we observed a 4.5-fold higher risk for all types of cancer. This group of relatives had a significantly higher risk for STS, female breast cancer, malignant brain tumor, and leukemia than did the general population.

Table 2.

SIRs for Relatives in 107 Kindreds Identified through 3-Year Survivors of Childhood STS, Grouped by Germline p53 Mutation Status

|

All Relatives(N=3,349) |

Mutation Carriers(N=56) |

Relatives with 50% Risk(N=92) |

Noncarrier(N=3,201) |

|||||

| Cancer Type | N | SIR (95% CI) | N | SIR (95% CI) | N | SIR (95% CI) | N | SIR (95% CI) |

| All cancera | 398 | 1.0 (.9–1.1) | 45 | 41.1 (29.9–55.0) | 29 | 4.5 (2.9–6.4) | 324 | .9 (.8–1.0) |

| STS | 21 | 6.8 (4.2–10.4) | 8 | 302.8 (130.4–596.8) | 4 | 69.7 (18.7–178.4) | 9 | 3.0 (1.3–5.7) |

| Osteosarcoma | 9 | 6.0 (2.7–11.5) | 5 | 289.0 (93.1–674.4) | 0 | … | 4 | 2.7 (.7–7.1) |

| Female breast | 66 | 1.0 (.8–1.3) | 13 | 105.1 (55.9–179.8) | 5 | 5.7 (1.8–13.3) | 48 | .7 (.5–1.0) |

| Brain | 20 | 2.3 (1.4–3.6) | 3 | 45.0 (9.0–131.5) | 7 | 49.4 (19.8–101.7) | 10 | 1.2 (.5–2.2) |

| Leukemia | 25 | 2.0 (1.3–3.0) | 4 | 47.3 (12.7–121.1) | 3 | 12.0 (2.4–35.0) | 18 | 1.5 (.9–2.4) |

| Multiple myeloma | 10 | 2.5 (1.2–4.6) | 2 | 171.6 (19.2–619.6) | 0 | … | 8 | 2.0 (.8–4.0) |

| Ovarian | 12 | 1.1 (.5–1.9) | 4 | 120.5 (32.4–308.5) | 1 | 5.4 (.0–30.0) | 7 | .6 (.2–1.3) |

| Lung | 63 | .9 (.7–1.2) | 8 | 38.5 (16.6–76.0) | 3 | 3.0 (.6–8.8) | 52 | .8 (.6–1.0) |

| Prostate | 25 | .8 (.5–1.2) | 2 | 52.2 (5.8–188.7) | 1 | 1.8 (.0–10.4) | 22 | .8 (.5–1.2) |

| Esophagus | 2 | .3 (.04–1.1) | 1 | 46.6 (.6–259.6) | 0 | … | 1 | .1 (.0–.9) |

| Pancreas | 12 | 1.0 (.5–1.8) | 1 | 30.5 (.4–170.1) | 2 | 9.2 (1.0–33.3) | 9 | .8 (.4–1.5) |

| Liver | 5 | .8(.2–1.9) | 1 | 60.7 (.7–337.9) | 0 | … | 4 | .6 (.1–1.7) |

| Colon | 27 | .6 (.4–.8) | 2 | 18.1 (2.0–65.6) | 1 | 1.2 (.0–6.7) | 24 | .5 (.3–.8) |

| Rectal | 11 | .4 (.2–.8) | 3 | 45.5 (9.1–133.1) | 0 | … | 8 | .3 (.1–.7) |

| Buccal cavity | 4 | .2 (.1–.6) | 1 | 12.8 (.1–71.2) | 0 | … | 3 | .1 (.04–.5) |

| Melanoma | 15 | 1.3 (.7–2.1) | 1 | 11.0 (.1–61.6) | 1 | 7.9 (.1–44.4) | 13 | 1.1 (.6–1.9) |

| Testicular | 4 | 1.4 (.3–3.7) | 1 | 23.2 (.3–129.1) | 0 | … | 3 | 1.1 (.2–3.3) |

All types of cancer except nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Discussion

The present study investigated the cancer risk in kindreds ascertained on the basis of the presence of STS in their probands, rather than on the basis of a history of excess early-onset cancers, and thus is clearly different from most reported studies of cancer-prone families. We identified germline p53 mutations in 6.6% of the kindreds that we studied, a percentage that is similar to the 4.1% identified in 196 case subjects with sarcoma and the 9% in 33 case subjects with rhabdomyosarcoma (Toguchida et al. 1992; Diller et al. 1995). We characterized the cancer risks of p53 mutation carriers and comparable noncarriers who had been systematically followed for >20 years. The noncarriers had a cancer risk that was almost identical to that for the general population. In the p53 mutation carriers, we observed several characteristics that were consistent with previously reported findings: LFS-component cancers represented the largest proportion of cancer incidence, and breast cancers represented the largest number of tumors diagnosed (Kleihues et al. 1997). We also observed significantly earlier ages at onset of gastrointestinal and lung cancers for the mutation carriers, supporting a previous suggestion to include these cancer types as possible LFS components (Varley et al. 1997). However, in contrast with a previous report (Birch et al. 2001), there were only a few rare cancer types in our carriers: no adrenocortical carcinoma or Wilms tumor and only one phyllodes tumor.

We also observed a 12-fold higher second-cancer risk for the carriers, which was similar to the risk reported for the 24 families with LFS that had had their first cancer diagnosed between ages 20 and 44 years (Hisada et al. 1998). Although it appeared to take longer for the carriers to develop a second cancer than for the noncarriers, this difference was mainly due to the carriers’ earlier age at first-cancer diagnosis.

p53 is unique among tumor-suppressor genes: most p53 mutations are missense mutations, whereas truncation mutations are more common for other tumor-suppressor genes (Hernandez-Boussard et al. 1999; Hussain and Harris 1999; Guimaraes and Hainaut 2002). Several laboratory and animal studies have suggested that some p53 mutants have dominant-negative activity over the wild-type p53 or gain new functions (Dittmer et al. 1993; Hsiao et al. 1994; Gualberto et al. 1998; Blagosklonny 2000; Hixon et al. 2000; Sigal and Rotter 2000; van Oijen and Slootweg 2000). The novel functions of mutant p53 may be caused by inhibition of wild-type p53 through hetero-oligomerization or by acquiring abilities to bind new DNA sequences or new protein partners (Roemer 1999; Cadwell and Zambetti 2001). The hypothesis of mutant p53’s gain of function has also been suggested on the basis of a study of families with LFS (Birch et al. 1998). The study by Birch et al. (1998) reported a significantly higher cancer incidence and earlier age at cancer diagnosis in families with LFS that carry missense mutations at the DNA binding domain of p53 than in families that carry protein-inactivation mutations. In addition, a significantly higher risk for breast and CNS cancers was observed in families with mutations at the DNA binding domain.

The present study did not show a higher cancer incidence or earlier onset in p53 mutation carriers who had missense mutations at the central core domain or p53 than in those who had truncation mutations. In several studies, two of the kindreds studied that carried missense mutations (R175H and R248W) have been shown to have gain-of-function and/or dominant-negative activities (Wang et al. 1998; Di Como et al. 1999; Roemer 1999); however, there was no difference in cancer risk between these two groups of mutation carriers. We used only data for confirmed mutation carriers, instead of data for all the relatives in the p53 mutation–positive kindreds. These two groups of carriers had similar distributions of sex and birth years and thus represented a unique cohort for testing the hypothesis of mutant p53’s gain of function. The differences in data source, the p53 mutation sites, and strategies for family recruitment may all contribute to the difference of findings between the present study and previous studies.

We observed nearly equal numbers of male and female p53 mutation carriers, which is a finding consistent with the results of a meta-analysis (Kleihues et al. 1997). We observed cancer risk to be significantly higher in female p53 carriers than in male carriers, which is a finding that had not, to our knowledge, been described previously. The latter finding is consistent with a report of different risk for the development of tumors between male and female mutant p53 mice: the incidence of osteosarcoma was observed to be consistently higher in female mice than in male mice, regardless of genetic backgrounds (Donehower et al. 1995). There are also several anecdotal reports supporting that male p53 mutation carriers may have a lower risk for cancer than female carriers. One of the three subjects with germline p53 mutations who were studied by Toguchida et al. (1992) had an unaffected father in his mid-50s. In a kindred that carried the R290H mutation, the father of a 9-year-old girl who had a brain tumor and the father of the girl’s first cousin, who died of rhabdomyosarcoma, were unaffected (Quesnel et al. 1999). In a germline p53 mutation–positive family reported by Saeki et al. (1997), two of the four male carriers in the probands’ generation were unaffected, whereas both female carriers, including the proband, were affected. Grayson et al. (1994) have reported an unaffected 38-year-old father of a p53 mutation carrier who had adrenal cortical carcinoma. Sun et al. (1996) have reported a p53 mutation–positive family with late-onset breast cancer and have noted unaffected male relatives—but, again, no females—in their 50s and 70s. In the present study cohort, all female carriers developed cancer by age 55 years, whereas six male carriers were still unaffected at age 50 years and two of them were unaffected at age 60 years.

It is not clear yet what is the mechanism for the sex difference in cancer risk. The significantly earlier age at cancer onset in the female carriers was not due simply to the incidence of female breast cancer; we also observed an increased risk for brain and lung cancer in women. The large difference between men and women in age at cancer diagnosis and the large number of childhood and adolescent cancer cases among the mutation carriers lessened the possibility that the sex-related differences could be explained by the fact that women seek medical care more frequently than men. It is tempting to speculate that sex hormones may contribute to this observation; however, we could not investigate this in detail, because all female mutation carriers developed cancer by age 55 years. It is expected that future study, to evaluate cancer risk in a larger group of mutation carriers, will further characterize the sex difference and may aid in the generation of biological mechanisms that lead to the difference.

Acknowledgments

We thanks B. Mims for germline p53 testing, G. Robertson and D. Sembera for family contact, P. Begin for sample collection, and the family members for kind support. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA 34936.

Electronic-Database Information

The URL for data presented herein is as follows:

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for LFS and p53)

References

- Birch JM, Alston RD, McNally RJ, Evans DG, Kelsey AM, Harris M, Eden OB, Varley JM (2001) Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene 20:4621–4628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch JM, Blair V, Kelsey AM, Evans DG, Harris M, Tricker KJ, Varley JM (1998) Cancer phenotype correlates with constitutional TP53 genotype in families with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Oncogene 17:1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV (2000) p53 from complexity to simplicity: mutant p53 stabilization, gain-of-function, and dominant-negative effect. FASEB J 14:1901–1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy ML, Lustbader ED, Strom SS, Strong LC (1992) Segregation analysis of 159 soft tissue sarcoma kindreds: comparison of fixed and sequential sampling schemes. Genet Epidemiol 9:291–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougeard G, Limacher JM, Martin C, Charbonnier F, Killian A, Delattre O, Longy M, Jonveaux P, Fricker JP, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Flaman JM, Frebourg T (2001) Detection of 11 germline inactivating TP53 mutations and absence of TP63 and HCHK2 mutations in 17 French families with Li-Fraumeni or Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome. J Med Genet 38:253–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell C, Zambetti GP (2001) The effects of wild-type p53 tumor suppressor activity and mutant p53 gain-of-function on cell growth. Gene 277:15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Como CJ, Gaiddon C, Prives C (1999) p73 function is inhibited by tumor-derived p53 mutants in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 19:1438–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diller L, Sexsmith E, Gottlieb A, Li FP, Malkin D (1995) Germline p53 mutations are frequently detected in young children with rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Invest 95:1606–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer D, Pati S, Zambetti G, Chu S, Teresky AK, Moore M, Finlay C, Levine AJ (1993) Gain of function mutations in p53. Nat Genet 4:42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Vogel H, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA Jr, Park SH, Thompson T, Ford RJ, Bradley A (1995) Effects of genetic background on tumorigenesis in p53-deficient mice. Mol Carcinog 14:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Mims B, McMasters KM, Foster CJ, deAndrade M, Amos CI, Strong LC, Lozano G (1998) Exclusion of a p53 germline mutation in a classic Li-Fraumeni syndrome family. Hum Genet 102:681–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaman JM, Frebourg T, Moreau V, Charbonnier F, Martin C, Chappuis P, Sappino AP, Limacher IM, Bron L, Benhattar J, Tada M, Van Meir EG, Estreicher A, Iggo RD (1995) A simple p53 functional assay for screening cell lines, blood, and tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:3963–3967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frebourg T, Barbier N, Yan YX, Garber JE, Dreyfus M, Fraumeni J Jr, Li FP, Friend SH (1995) Germ-line p53 mutations in 15 families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 56:608–615 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson GH, Moore S, Schneider BG, Saldivar V, Hensel CH (1994) Novel germline mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in a child with incidentally discovered adrenal cortical carcinoma. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 16:341–347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualberto A, Aldape K, Kozakiewicz K, Tlsty TD (1998) An oncogenic form of p53 confers a dominant, gain-of-function phenotype that disrupts spindle checkpoint control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:5166–5171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes DP, Hainaut P (2002) TP53: a key gene in human cancer. Biochimie 84:83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes VM, Bleeker W, Verlind E, Timmer T, Karrenbeld A, Plukker JT, Marx MP, Hofstra RMW, Buys CHCM (1999) Comprehensive TP53-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis mutation detection assay also applicable to archival paraffin-embedded tissue. Diagn Mol Pathol 8:2–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Boussard T, Rodriguez-Tome P, Montesano R, Hainaut P (1999) IARC p53 mutation database: a relational database to compile and analyze p53 mutations in human tumors and cell lines. Hum Mutat 14:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisada M, Garber JE, Fung CY, Fraumeni JF Jr, Li FP (1998) Multiple primary cancers in families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst 90:606–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixon ML, Flores A, Wagner M, Gualberto A (2000) Gain of function properties of mutant p53 proteins at the mitotic spindle cell cycle checkpoint. Histol Histopathol 15:551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao M, Low J, Dorn E, Ku D, Pattengale P, Yeargin J, Haas M (1994) Gain-of-function mutations of the p53 gene induce lymphohematopoietic metastatic potential and tissue invasiveness. Am J Pathol 145:702–714 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain SP, Harris CC (1999) p53 mutation spectrum and load: the generation of hypotheses linking the exposure of endogenous or exogenous carcinogens to human cancer. Mutat Res 428:23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A, Matthay KK, Steinkirchner TM, Israel MA (1992) Germ-line and somatic p53 gene mutations in multifocal osteogenic sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:4207–4209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleihues P, Schauble B, zur Hausen A, Esteve J, Ohgaki H (1997) Tumors associated with p53 germline mutations: a synopsis of 91 families. Am J Pathol 150:1–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyritsis AP, Bondy ML, Xiao M, Berman EL, Cunningham JE, Lee PS, Levin VA, Saya H (1994) Germline p53 gene mutations in subsets of glioma patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 86:344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law JC, Strong LC, Chidambaram A, Ferrell RE (1991) A germ line mutation in exon 5 of the p53 gene in an extended cancer family. Cancer Res 51:6385–6387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ (1997) p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 88:323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz SR, Parzen M (1996) A jackknife estimator of variance for Cox regression for correlated survival data. Biometrics 52:291–298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustbader ED, Williams WR, Bondy ML, Strom S, Strong LC (1992) Segregation analysis of cancer in families of childhood soft-tissue-sarcoma patients. Am J Hum Genet 51:344–356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin D, Jolly KW, Barbier N, Look AT, Friend SH, Gebhardt MC, Andersen TI, Borresen AL, Li FP, Garber J, Strong LC (1992) Germline mutations of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene in children and young adults with second malignant neoplasms. N Engl J Med 326:1309–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF Jr, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, Friend SH (1990) Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science 250:1233–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AC, Facchiano AM, Cuff AL, Hernandez-Boussard T, Olivier M, Hainaut P, Thornton JM (2002) Integrating mutation data and structural analysis of the TP53 tumor-suppressor protein. Hum Mutat 19:149–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre JF, Smith-Sorensen B, Friend SH, Kassell J, Borresen AL, Yan YX, Russo C, Sato J, Barbier N, Miser J, Malkin D, Gebhardt MC (1994) Germline mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in children with osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol 12:925–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols KE, Malkin D, Garber JE, Fraumeni JF Jr, Li FP (2001) Germ-line p53 mutations predispose to a wide spectrum of early-onset cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10:83–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel S, Verselis S, Portwine C, Garber J, White M, Feunteun J, Malkin D, Li FP (1999) p53 compound heterozygosity in a severely affected child with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Oncogene 18:3970–3978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapakko K, Allinen M, Syrjakoski K, Vahteristo P, Huusko P, Vahakangas K, Eerola H, Kainu T, Kallioniemi OP, Nevanlinna H, Winqvist R (2001) Germline TP53 alterations in Finnish breast cancer families are rare and occur at conserved mutation-prone sites. Br J Cancer 84:116–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer K (1999) Mutant p53: gain-of-function oncoproteins and wild-type p53 inactivators. Biol Chem 380:879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y, Tamura K, Yamamoto Y, Hatada T, Furuyama J, Utsunomiya J (1997) Germline p53 mutation at codon 133 in a cancer-prone family. J Mol Med 75:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shete S, Amos CI, Hwang SJ, Strong LC (2002) Individual-specific liability groups in genetic linkage, with applications to kindreds with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 70:813–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal A, Rotter V (2000) Oncogenic mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor: the demons of the guardian of the genome. Cancer Res 60:6788–6793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong LC, Williams WR (1987) The genetic implications of long-term survival of childhood cancer: a conceptual framework. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 9:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XF, Johannsson O, Hakansson S, Sellberg G, Nordenskjold B, Olsson H, Borg A (1996) A novel p53 germline alteration identified in a late onset breast cancer kindred. Oncogene 13:407–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toguchida J, Yamaguchi T, Dayton SH, Beauchamp RL, Herrera GE, Ishizaki K, Yamamuro T, Meyers PA, Little JB, Sasaki MS, Weichselbaum RR, Yandell DW (1992) Prevalence and spectrum of germline mutations of the p53 gene among patients with sarcoma. N Engl J Med 326:1301–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oijen MG, Slootweg PJ (2000) Gain-of-function mutations in the tumor suppressor gene p53. Clin Cancer Res 6:2138–2145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varley JM, McGown G, Thorncroft M, Santibanez-Koref MF, Kelsey AM, Tricker KJ, Evans DG, Birch JM (1997) Germ-line mutations of TP53 in Li-Fraumeni families: an extended study of 39 families. Cancer Res 57:3245–3252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LH, Okaichi K, Ihara M, Okumura Y (1998) Sensitivity of anticancer drugs in Saos-2 cells transfected with mutant p53 varied with mutation point. Anticancer Res 18:321–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]