Abstract

Polar growth is a fundamental process in filamentous fungi and is necessary for disease initiation in many pathogenic systems. Previously, swoF was identified in Aspergillus nidulans as a single-locus, temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant aberrant in both polarity establishment and polarity maintenance. The swoF gene was cloned by complementation of the ts phenotype and sequenced. The derived protein sequence had high identity with N-myristoyl transferases (NMTs) found in fungi, plants, and animals. In addition, wild-type growth at restrictive temperature was partially restored by the addition of myristic acid to the growth medium. Sequencing revealed that the mutation in swoF changes the conserved aspartic acid 369 to a tyrosine. The predicted A. nidulans SwoF protein, SwoFp, was homology modeled based on crystal structures of NMTs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. The D369Y swoF mutation is on the opposite face of the protein, distal to the myristoyl coenzyme A and peptide substrate binding sites. In wild-type NMTs, D369 appears to stabilize a structural β-strand bend through two hydrogen bonds and an ionic interaction. These stabilizing bonds are abolished in the D369Y mutant. We hypothesize that a substrate of SwoFp must be myristoylated for proper polarity establishment and maintenance. The mutation prevents the proper function of SwoFp at restrictive temperature and thus blocks polar growth.

For many filamentous fungi, two distinct growth modes are used during the process of spore germination and early development. When dormancy is broken, the spore first grows isotropically, adding new cell wall material uniformly in every direction. A switch to polarized growth soon follows, with new cell wall deposition occurring only at the growing tip, leading to elongated hyphae characteristic of filamentous fungi. In Aspergillus nidulans, the switch from isotropic to polar growth occurs just after the first round of mitosis (34). Two distinct processes are involved in the switch to polar growth: polarity establishment, i.e., choosing the spot where new material will be deposited, and polarity maintenance, i.e., the continued deposition of wall material at the growing tip.

Not surprisingly, the process of polar growth requires an intact cytoskeleton and proper vesicle transport. Pharmacological disruption of F actin prevents the polar growth of Neurospora crassa and Saprolegnia ferax (22). The actin-associated motor protein myosin has a high level of tip localization, and loss of myosin function in A. nidulans leads to large apolar cells (32, 37). Mutations in sepA, which encodes an actin-associated protein, result in abnormally large, septumless A. nidulans hyphae (20). In N. crassa, kinesin and dynein mutants grow with abnormally short, thick germ tubes (40, 41). Normal vesicle assembly is also required for polar growth. The A. nidulans α-cop-related gene sodVIC, involved in coated vesicle assembly, is essential both to establish polarity and to maintain polarity (45).

Because polar growth is coordinated with nuclear division in filamentous fungi, it is also not surprising that cell division signaling pathways are involved in polarity. A cyclin-dependent kinase mutant (phoA) and a mitogen-activated protein kinase deletion mutant (mpkA) both have abnormal germination and polarity maintenance (10). Strains with mutations in the protein phosphatase gene pphA display abnormal hyphal growth and mitotic defects (28). Temperature-sensitive (ts) mutations in N. crassa protein kinase A result in swollen cells with abnormal polarity maintenance (8). Also, in N. crassa the Ser/Thr protein kinase encoded by cot1 is necessary for polar growth (18, 47). In Penicillium marneffei, the Cdc42 (Rho) homologue encoded by cflA is required for both polarity establishment and polarity maintenance (7).

The A. nidulans swo (swollen cell) mutants are characterized by either continued isotropic growth without establishment of polarity or the inability to maintain polar growth at restrictive temperatures (35). Through a series of temperature shift experiments and genetic crosses, it was determined that the events of polarity establishment and polarity maintenance are genetically separable. swoC and swoD were found to be involved in polarity establishment, while swoA was found to be required for polarity maintenance. swoF was found to be involved in both processes.

In this study, we describe the cloning, sequencing, and further characterization of swoF (35). We show that swoF encodes an N-myristoyl transferase (NMT). NMTs are highly conserved proteins that catalyze the transfer of myristate (C14:0) from myristoyl coenzyme A (myristoyl-CoA) to the N-terminal glycine of a subset of cellular proteins (4-6). This modification increases the affinity of the target protein for membranes and has been proposed to constitute a reversible mechanism that allows the target protein to switch between membrane-bound and cytoplasmic states (5). Known targets of NMTs include protein phosphatases, protein kinases, kinase substrates, and G protein α subunits (9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media used.

Strain A773 (pyrG89 pyroA4 wA3) was crossed with strain AJB11 (swoF) by using standard methods (21, 25) to produce strain AXL19 (pyrG89 swoF). All experiments reported here used strain AXL19 as the swoF mutant and strain A773 as the wild type. Media used were as previously reported (35).

Growth of germlings and microscopic observations.

Conditions for growth and preparation of germlings for observations were as previously reported (35). Microscopic observations were made by using an Axioplan microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, N.Y.), and digital images were acquired by using an Optronics (Goleta, Calif.) digital imaging system. Images were prepared by using Photoshop 5.5 (Adobe, Mountain View, Calif.).

Complementation and plasmid recovery.

A genomic library was generously provided by Greg May (University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston). This library was constructed by ligating Sau3A fragments of genomic DNA into the BamHI site of pRG3AMA1 (36). Protoplasts of AXL19 were produced and transformation was conducted by using standard A. nidulans protocols (48). Transformants were selected by assaying for restoration to pyrG prototrophy. Complementation was judged by restoration of wild-type growth at restrictive temperature (42°C). The complementing plasmid replicated autonomously (e.g., extrachromosomally) due to the AMA1 sequence (1) contained in the library vector. The complementing plasmid was recovered by transformation of Escherichia coli XL1-Blue with DNA isolated from the complemented strain and selection on ampicillin-containing medium. The restriction patterns of three rescued plasmids were compared, and those showing common insert patterns were used to retransform the swoF mutant. Two of three recovered plasmids complemented swoF and showed identical restriction patterns. One of these, p19c2, was chosen for sequencing.

Sequencing.

p19c2 was transposon tagged by using a GPS-1 kit (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. Colonies representing individual randomly tagged plasmids were arrayed in a 96-well format. Plasmid preparation was carried out with an R.E.A.L. 96-well kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Label was incorporated by using Big Dye 2.0 (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Boston, Mass.). Sequencing was done with outward-facing primers designed on the basis of the transposon provided with the GPS-1 kit. Unincorporated dyes were removed by using a DyeEx 96 kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Sequencing in the 96-well format was performed with an ABI Prism 3700 robotic sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Subsequent analysis was done with the programs Phred version 0.000925c and Phrap version 0.990319 for assembly and quality determination and Consed version 11.0 for sequence viewing and recovery (all three Unix-based programs are available from http://depts.washington.edu/ventures/collabtr/direct/ppccombo.htm). All sequences contained at least fourfold redundancy, with a quality rating of at least 20.

Identification of the swoF gene.

The complete sequence for complementing genomic DNA was compared to sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by using blastX. Multiple open reading frames were found within the genomic sequence. Transposon-tagged plasmids with strategically placed transposon insertions were chosen from the plasmid array to test for complementation. Transposon-tagged plasmids were transformed into AXL19. Transformants were replica plated at permissive and restrictive temperatures. The open reading frame which, when disrupted by transposon insertion, lost the ability to restore AXL19 to wild-type growth at 42°C was identified as swoF.

Sequencing of the swoF mutant allele.

Genomic DNA from AXL19 was isolated by using standard methods (39). This genomic DNA was used as a template in a PCR with the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind.). The following primers were used for PCR amplification: swoF5 BamHI, 5-CGGGATCCCGATGTCAGACTCAAAAGACTC-3, and swoF3 SpeI, 5-GGACTAGTCCCTAGAGCATAACAACGCCCA-3. Each primer contains a 20-mer based on the wild-type swoF sequence and a 10-mer to create a restriction enzyme recognition site. PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T vector system (Promega), transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue, and selected on ampicillin-containing medium with blue-white selection. Clones were verified by restriction analysis. Three clones were sequenced by using the strategy described above. Sequences of all three clones were compared to the wild-type sequence to determine the mutant lesion. All three had the same base change.

Protein alignment.

Sequences for orthologues of NMT were obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Protein sequence alignment was carried out by using the program GeneDoc version 2.6.001 (www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc) with default parameters and minimal manual adjustment to align sequences with secondary structural features.

Homology modeling.

The model for the predicted A. nidulans SwoF protein, SwoFp, was prepared by homology modeling with the program Swiss PDB Viewer version 3.7b2 (http://www.expasy.ch/spdbv/). The templates used were the atomic structures determined by X-ray crystallography of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae NMT complexed with myrisoyl-CoA and a peptide analogue (Protein Data Bank accession number 2NMT) and the Candida albicans NMT (PDB accession number 1NMT). The structure of the S. cerevisiae NMT was used as the principal model as it represents a conformationally closed complex representative of the substrate-bound structure. Loops were built by using the Swiss PDB Viewer; in some cases, program O was used (24) because of its ability to merge coordinates and slightly better modeling capabilities. Poor side-chain orientations were identified by their high energies and corrected by using the optimize function in Swiss PDB Viewer. After all loops were built and side-chain conformations were corrected, the model was energy minimized by using steepest descent and conjugate gradients until the change in energy between steps was <0.05 kJ/mol and no locally poor energies remained. The model has threading energies, conformational energies, and phi-psi plots similar to those of the original crystal structures. Thus, no attempt was made to correct geometric or energetic problem areas that appeared to carry over from the atomic structures. The nomenclature for β strands and α helices follows that used by Bhatnagar and colleagues (3). The substrate myristoyl-CoA and the peptide analogue from 2NMT were docked by using the magic-fit option. No energy minimization was required.

Growth restoration with myristate.

To ascertain if myristic acid medium amendment allowed polar growth of swoF cells at restrictive temperature, A773 and AXL19 were grown either in liquid or on solid minimal medium containing 500 μM myristate and 1% (wt/vol) Brij 58 (polyoxyetheylene 20 cetyl ether) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The presence of 1% Brij 58 helps to solubilize myristate (14).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The full genomic sequence, as well as intron locations, and the predicted protein sequence determined here have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AY057437.

RESULTS

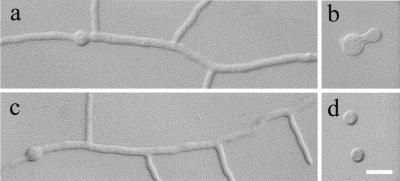

The swoF mutant was identified in a screen for ts mutants with defects in polar growth (35). Originally, swoF was thought to be necessary for both polarity establishment and polarity maintenance based on the failure to initiate germ tube growth at a restrictive temperature and upon a shift from a restrictive to a permissive temperature. However, in our current experiments, we found that swoF cells did sometimes initiate polar growth after 16 h of incubation at restrictive temperature (42°C), making short, thick germ tubes with swollen apices (16%; n = 500) (Fig. 1b). However, the majority of swoF cells failed to make germ tubes at the restrictive temperature, as previously reported (Fig. 1d). Both swoF cells with short germ tubes and those without germ tubes completed two or three mitotic divisions after 16 h of incubation at the restrictive temperature. In contrast, wild-type germlings under the same conditions produced elongated primary and secondary germ tubes with one or more lateral branches (Fig. 1a) and underwent five or more mitotic events after 16 h of incubation.

FIG. 1.

Wild-type, swoF, and complemented cells grown in complete medium for 16 h at restrictive temperature (42°C). (a) Wild-type strain A773. (b and d) Two morphologies of swoF strain AXL19. (c) AXL19 transformed with p19c2 containing wild-type swoF. Bar, 10 μm.

Complementation and sequencing of wild-type and mutant alleles.

A swoF pyrG strain was transformed with a genomic library constructed in vector pRG3AMA1, which carries the pyr4 gene and the AMA1 sequence for plasmid autonomous replication (1, 36). A total of 1,092 pyr prototrophs were screened for growth at restrictive temperature (42°C). Three transformants were judged to be complemented based on wild-type colony morphology at the restrictive temperature. These transformants also showed wild-type morphology when examined microscopically (Fig. 1c). Restriction digestion of the complementing plasmid in each of the three transformants revealed that two contained precisely the same genomic insert (data not shown). One of these two, plasmid p19c2, was selected for sequencing by transposon insertion.

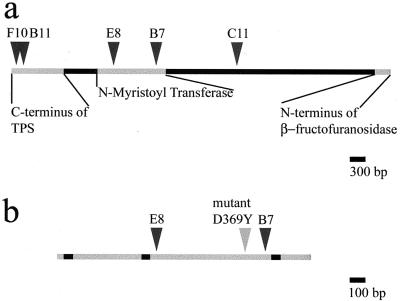

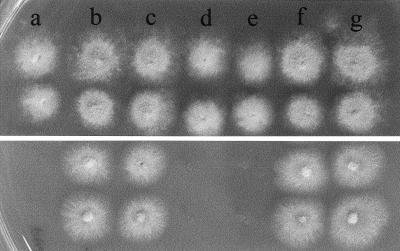

The genomic insert in p19c2 is 7,385 bp long (Fig. 2a). It encodes predicted proteins with high similarity to NMTs (see below), the C terminus of a tetrahydrofolylpolyglutamate synthase, and the N terminus of a β-fructofuranosidase. The swoF mutant was transformed with plasmids containing transposon insertion disruptions in the tetrahydrofolylpolyglutamate synthase region (F10 and B11), the NMT region (E8 and B7), or the large region without a predicted open reading frame (C11). Only an insertion in the NMT region disrupted the ability of p19c2 to complement swoF temperature sensitivity (Fig. 3). Both tested transposon insertions in the NMT homologue failed to complement swoF (Fig. 3d and e); therefore, the complementing gene encodes an NMT. The A. nidulans NMT gene, swoF, is 1,639 bp long and contains three introns of 55, 56, and 49 bp, making the cDNA 1,479 bp long (Fig. 2b). Intron placement was deduced on the basis of consensus splice site sequences (2) and protein alignment with known NMT sequences. Transposons E8 and B7 are inserted in the third exon of the gene at 637 and 1,358 bp, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Complementing genomic DNA and swoF. (a) Schematic representation of the 7,385-bp genomic fragment that complements swoF. Three open reading frames were revealed by a search of GenBank, the full NMT gene and portions of a tetrahydrofolylpolyglutamate synthase (TPS) gene and a β-fructofuranosidase gene. The locations of five transposon insertions are indicated by arrowheads. (b) Schematic representation of swoF (NMT), a 1,639-bp open reading frame containing three introns represented by black boxes. The light gray arrowhead shows the location of mutant lesion D369Y.

FIG. 3.

Transposon insertion verifies that the NMT region complements swoF. Colonies of swoF cells were grown at a permissive temperature (30°C) (top) or at restrictive temperature (42°C) (bottom). (a) swoF. (b to g) swoF transformed with p19c2 containing no transposon insertion (b) or transposon insertion C11 (c), E8 (d), B7 (e), F10 (f), or B11(g).

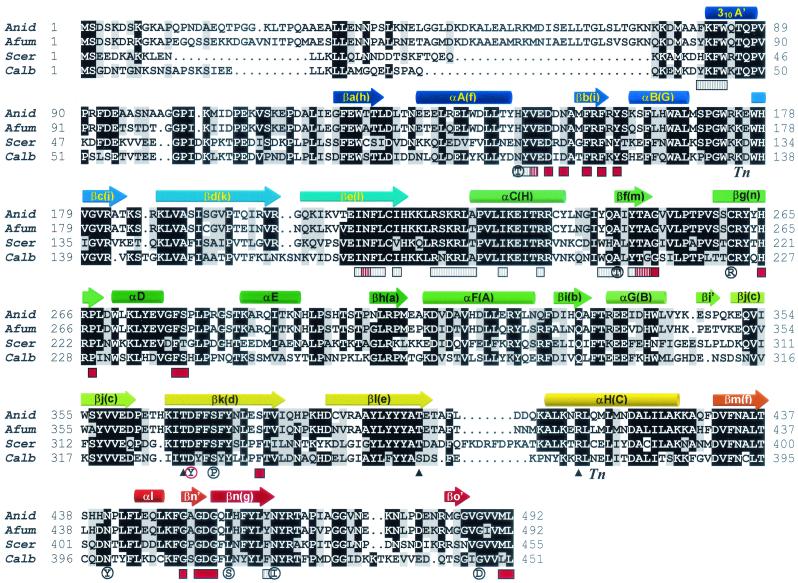

Alignment of the SwoFp sequence with several other known NMT proteins revealed a high degree of conservation (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The highest identity and similarity (80 and 88%, respectively) were to a predicted NMT from Aspergillus fumigatus found in GenBank. The highest identity and similarity to an experimentally verified NMT were to S. cerevisiae Nmt1p (50 and 65%, respectively). The N-terminal 30 to 100 residues of these proteins were poorly conserved; however, the remaining 350 to 400 residues were highly conserved.

TABLE 1.

Identity and similarity of SwoFp and other NMTs

| Species | Protein | GenBank accession no. | %

|

e value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | Similarity | ||||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Nmtp | 6505827 | 80 | 88 | 0.0 |

| Ajellomyces capsulatus | Nmt1p | P34763 | 65 | 81 | 0.0 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Nmt1p | NP 013296 | 50 | 65 | e−114 |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Nmt1p | O43010 | 50 | 65 | e−125 |

| Candida albicans | Nmt1p | P30418 | 46 | 61 | e−110 |

FIG. 4.

Alignment of A. nidulans SwoFp (Anid), putative Nmtp from A. fumigatus (Afum), Nmt1p from S. cerevisiae (Scer), and Nmt1p from C. albicans (Calb). Black shading shows residue identity in at least three proteins. Gray shading shows similarity in at least two residues. Secondary structures are shown above the corresponding amino acid sequence as colored arrows (β strands) or cylinders (α helices) coded blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus). The nomenclature for the secondary structures follows that used by Bhatnager et al. (3). Residues involved in binding myristoyl-CoA are indicated by gray stippled bars below the corresponding sequence, residues involved in binding the peptide substrate are indicated by red bars, and residues involved in binding both ligands are indicated by gray and red stippled bars. Tn, sites of transposon insertion disruption at K175 (E8) and at Q415 (B7). Solid black triangles below the sequence indicate residues interacting with D369. S. cerevisiae ts mutations reported by Zhang et al. (49) are indicated by a mutant residue enclosed by a black circle below the wild-type residue. The A. nidulans swoF mutation is denoted by a mutant residue (Y) enclosed by a red circle below the wild-type D residue.

The swoF mutant allele was amplified from AXL19 by PCR. Sequence determination for three replicate PCR clones showed that the swoF mutant allele contains a change in base 1216 of the genomic sequence from G to T, resulting in a change in protein residue 369 from aspartic acid to tyrosine.

Protein modeling.

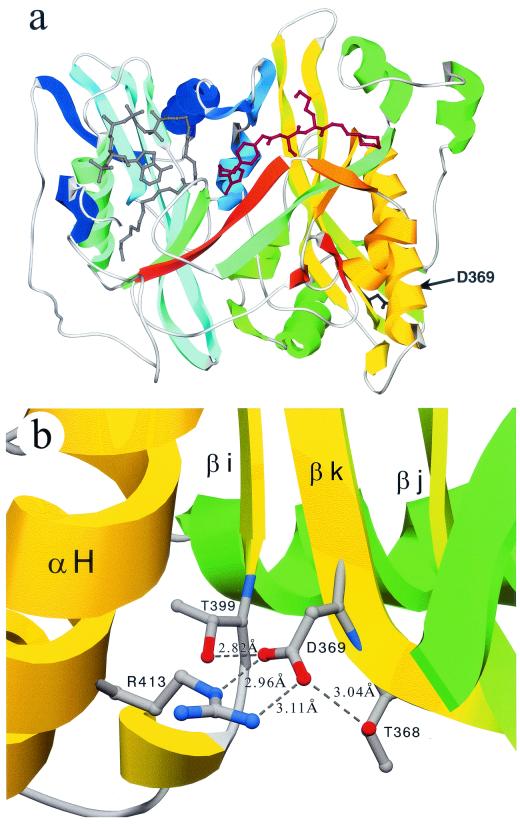

The crystal structures for the C. albicans and S. cerevisiae NMTs have been determined with and without bound substrate peptide and myristoyl-CoA analogues (3, 16, 44). The Nmt1p fold contains a large β sheet bisected by a pseudo-twofold symmetry axis and flanked by several α helices. The ligand binding sites are related by a pseudo-twofold axis, with the myristoyl-CoA binding to the N-terminal half of the protein and the peptide substrate binding to the C-terminal half. Using these structures as templates, we generated a homology model for A. nidulans SwoFp (Fig. 5). The N-terminal 76 amino acids are missing from the crystal structures and so are not included in our model. Most of the residues found to be important in myristoyl-CoA binding, peptide binding, or transferase activity are conserved in SwoFp (Fig. 4). Amino acids critical for structural stability are also conserved among all NMTs. The swoF D369Y mutation changes one of these structurally important residues, an aspartic acid that participates in stabilizing a turn in β-strand βk via hydrogen bonds and an ionic interaction (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Ribbon representation of the A. nidulans SwoFp homology model. (a) The SwoFp homology model lacking the first 76 residues is portrayed in a ribbon representation with secondary structure features colored blue (N terminus) through red (C terminus). The substrate molecules are shown in ball-stick representation with myristoyl-CoA colored gray and a peptide analogue colored red. The side chain of D369 projects from β-strand βk and is shown in ball-stick representation and colored black. Helix αH is at the lower right of this view and is colored yellow. (b) Enlargement of the region near D369. The view is rotated about 90° relative to that in panel a, looking down the arrow toward D369. The side chains of T368, D369, T399, and R413 are shown in ball-stick representation. Broken lines represent hydrogen bonds. Bond distances are indicated.

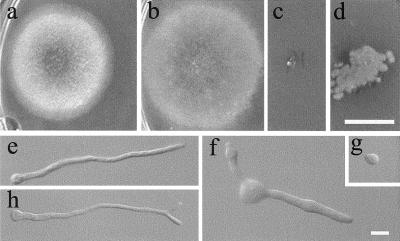

Partial growth restoration with myristate.

In S. cerevisiae, the addition of myristate restores wild-type growth to most ts nmt mutants (14). Strain AXL19 containing the swoF mutation did not produce a mycelial colony at 42°C (Fig. 6c). However, with the addition of 500 μM myristate, AXL19 produced a filamentous colony (Fig. 6d), although it was smaller than the colony produced by swoF+ strain A773 (Fig. 6b). Microscopically, A773 establishes characteristic long filamentous germ tubes in minimal medium with or without 500 μM myristate (Fig. 6e and h). swoF cells grown in minimal medium at restrictive temperature either failed to establish polarity (Fig. 1d and 6g) or established but could not maintain polarity (Fig. 1b). Viewed microscopically, swoF cells grown in minimal medium amended with 500 μM myristate established and maintained polarity but showed abnormal swelling within spores and hyphae. Germ tubes were also thicker and shorter than those of the wild type in the presence of myristate (Fig. 6f).

FIG. 6.

Medium supplementation with myristate partially restores the growth of swoF cells. (a and c) Wild-type and swoF colonies, respectively, after 48 h of incubation in minimal medium at restrictive temperature. (b and d) Wild-type and swoF colonies, respectively, after 48 h of incubation in minimal medium supplemented with 500 μM myristate and 1% Brij 58 at restrictive temperature. (e and g) Wild-type and swoF germlings, respectively, after 16 h of incubation in minimal medium at restrictive temperature. (h and f) Wild-type and swoF germlings, respectively, after 16 h of incubation in minimal medium supplemented with 500 μM myristate and 1% Brij 58 at restrictive temperature. Bars: d (for a to d), 1 cm; f (for e to h), 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

SwoFp is an NMT.

The swoF mutant was restored to wild-type growth by introduction of an A. nidulans gene predicted to encode an NMT. Given the high level of sequence conservation among NMTs, the identification of the complementing gene as an NMT gene is unambiguous. The presence of the D369Y mutation in the swoF gene in the mutant argues that the NMT is not a suppressor of swoF. Myristate amendment of medium restores wild-type growth to nmt mutants in S. cerevisiae, Cryptococcus neoformans, and other organisms (23, 30). Indeed, the first S. cerevisiae nmt mutant was discovered as a myristate auxotroph (33). Thus, the ability of myristate to partially restore wild-type growth to the swoF mutant further argues that the mutant lesion is within the NMT gene. Myristate remediation is thought to increase the pools of myristoyl-CoA enough to overcome any myristoyl-CoA binding defect found in mutant Nmt proteins. It is also possible that myristate stabilizes the folding of the mutant protein. In this light, it is interesting that myristic acid allows only limited growth of the swoF mutant. Perhaps lower levels of NMT activity are sufficient for the very limited polar growth of yeasts such as S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans but are not sufficient for the highly polar growth of filamentous fungi such as A. nidulans.

Many NMT orthologues have been reported in the literature, including representatives from S. cerevisiae (15), C. albicans (46), Ajellomyces capsulatus (31), C. neoformans (30), and Homo sapiens (17). In addition, NMT orthologues from Schizosaccharomyces pombe and A. fumigatus are present in GenBank. NMT genes are single-copy genes in all fungi in which they have been characterized (30). Disruption of this single copy is lethal in S. cerevisiae (15), C. albicans (43), and C. neoformans (30). NMTs from C. albicans, C. neoformans, and H. sapiens functionally complement the lethal S. cerevisiae null allele (31). A preliminary search of the A. nidulans expressed sequence tag database (http://www.genome.ou.edu/asperblast.html) indicates only one NMT in A. nidulans. Additionally, in Southern analysis of A. nidulans genomic DNA, a swoF probe hybridizes to only one band (B. D. Shaw and M. Momany, unpublished data).

SwoFp homology model.

Using the X-ray crystal structures of NMTs from S. cerevisiae and C. albicans as templates, we homology modeled A. nidulans SwoFp (Fig. 5). Because most residues involved in substrate binding, catalysis, and structural stability among the NMTs are absolutely conserved, our model is likely very accurate. As can be seen in the template structures, the predicted SwoFp consists of two β sheets related by a pseudo-twofold symmetry axis and flanked by α helices. Most of the ts mutations previously reported for NMTs are either in the central core or in residues very near the substrate binding sites and result in higher Km and/or lower Vmax values relative to those for the wild type (Fig. 4) (3, 49). We expected that the D369Y lesion in the swoF mutant would also fall within the core or near the pockets where myristoyl-CoA and peptide ligands bind. However, the mutated residue is at the amino-terminal end of β-strand βk, near the surface of the protein and on the face opposite that of the substrate binding sites. The carboxy-terminal end of β-strand βk interacts with the peptide substrate. Therefore, one explanation for the temperature sensitivity is that the D369Y mutation distorts the orientation of strand βk and thus distorts peptide substrate binding. It seems more likely, however, that the D369Y mutation destabilizes the tertiary structure in the local region around strand βk and thus has a more global effect. Figure 5b illustrates the local environment around D369. In the wild-type protein, D369 stabilizes a bend at the amino-terminal end of βk by hydrogen bonding to T368 and bridges the side chains of neighboring secondary structures via an ionic interaction with R413 (helix αH) and hydrogen bonds with T368 and T399 (β-strand βi). T368 and D369 are absolutely conserved across species (49), suggesting that these residues play a critical role in NMTs. Alhough R413 and T399 are not conserved in higher eukaryotes, conservative replacements, such as K for R413 and S for T399, could maintain these interactions and substitute functionally. While modeling suggests that the bulky side chain of Y369 in the swoF mutant could be accommodated with some adjustment of the surrounding residues, the stabilizing effects of the ionic and hydrogen bonds would be completely lost. Destabilization of strand βk in the mutant could result in lower SwoFp activity levels through conformational changes affecting substrate binding and catalytic function. Alternatively, destabilization might lead to lower steady-state levels of SwoFp either from improper folding or from increased proteolytic sensitivity. If improper folding is the main defect in SwoFp, it raises the intriguing possibility that myristate remediation acts by furnishing a scaffold around which the myrisotyl-CoA binding pocket can be folded or stabilized.

Conclusion.

Polar growth is essential for the pathogenicity of A. fumigatus and many other fungal pathogens of animals and plants. Polar growth is a two-step process, and SwoFp plays a role in the first step (polarity establishment) and is absolutely required for the second step (polarity maintenance). Our current model for the involvement of SwoFp in polarity is that a target protein(s) required for polar growth must be myristoylated to be properly localized and/or fully active. At restrictive temperature, mutant SwoFp is unable to properly myristoylate its target. In this light, a recent report that an sgdD germination mutant is defective in a malonyl-CoA synthetase (36) is intriguing. This protein is involved in the formation of acetyl-CoA, a necessary precursor in the production of myristoyl-CoA. It is possible that sgdD is needed for the production of the myristoyl-CoA necessary for the myristoylation of an as-yet-unknown target responsible for the initiation of germination and polar growth.

NMTs are a highly conserved class of eukaryotic proteins; however, their substrate specificities have diverged, with fungal NMTs generally having targets different from those of mammalian NMTs (12, 13, 27, 30, 38). This target divergence, coupled with the fact that deletion of the single copy of the NMT gene in fungi is lethal (15, 30, 43), has led to considerable interest in NMTs as possible targets for a new class of antifungal drugs. This approach has met with success in C. albicans and C. neoformans, for which compounds that specifically inhibit myristoylation are being tested (11, 12, 26, 29, 42). To our knowledge, this option has not yet been explored for A. fumigatus, now the most common fungal pathogen found in autopsies of immunocompromised patients in European hospitals (19). This antifungal potential, coupled with the key role that myristoylation plays in polar growth (a critical aspect of fungal pathogenesis), is a fruitful area for further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by DOE biosciences grant DE-FG02-97ER20275 to M.M.

We thank Greg May (University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) for providing the genomic library used in this study, Xiaorong Lin (University of Georgia) for assistance in sequencing and crosses to create the swoF strain used in this study, and Greg Derda (University of Georgia) for computer assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aleksenko, A., and A. J. Clutterbuck. 1997. Autonomous plasmid replication in Aspergillus nidulans: AMA1 and MATE elements. Fungal Genet. Biol. 21:373-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballance, D. J. 1986. Sequences important for gene expression in filamentous fungi. Yeast 2:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatnagar, R. S., K. Futterer, T. A. Farazi, S. Korolev, C. L. Murray, E. Jackson-Machelski, G. W. Gokel, J. I. Gordon, and G. Waksman. 1998. Structure of N-myristoyltransferase with bound myristoyl-CoA and peptide substrate analogs. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:1091-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatnagar, R. S., K. Futterer, G. Waksman, and J. I. Gordon. 1999. The structure of myristoyl-CoA: protein N-myristoyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1441:162-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatnagar, R. S., and J. I. Gordon. 1997. Understanding covalent modifications of lipids: where cell biology and biophysics mingle. Trends Cell Biol. 7:14-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutin, J. A. 1997. Myristoylation. Cell. Signal. 9:15-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce, K. J., M. J. Hynes, and A. Andrianopoulos. 2001. The CDC42 homolog of the dimorphic fungus Penicillium marneffei is required for correct cell polarization during growth but not development. J. Bacteriol. 183:3447-3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruno, K. S., R. Aramayo, P. F. Minke, R. L. Metzenberg, and M. Plamann. 1996. Loss of growth polarity and mislocalization of septa in a Neurospora mutant altered in the regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 15:5772-5782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant, M. L., L. Ratner, R. J. Duronio, N. S. Kishore, B. Devadas, S. P. Adams, and J. I. Gordon. 1991. Incorporation of 12-methoxydodecanoate into the human immunodeficiency virus 1 gag polyprotein precursor inhibits its proteolytic processing and virus production in a chronically infected human lymphoid cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2055-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bussink, H. J., and S. A. Osmani. 1999. A mitogen-activated protein kinase (mpkA) is involved in polarized growth in the filamentous fungus, A spergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devadas, B., S. K. Freeman, C. A. McWherter, N. S. Kishore, J. K. Lodge, E. Jackson-Machelski, J. I. Gordon, and J. A. Sikorski. 1998. Novel biologically active nonpeptidic inhibitors of myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Med. Chem. 41:996-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devadas, B., S. K. Freeman, M. E. Zupec, H. F. Lu, S. R. Nagarajan, N. S. Kishore, J. K. Lodge, D. W. Kuneman, C. A. McWherter, D. V. Vinjamoori, D. P. Getman, J. I. Gordon, and J. A. Sikorski. 1997. Design and synthesis of novel imidazole-substituted dipeptide amides as potent and selective inhibitors of Candida albicans myristoylCoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase and identification of related tripeptide inhibitors with mechanism-based antifungal activity. J. Med. Chem. 40:2609-2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duronio, R. J., S. I. Reed, and J. I. Gordon. 1992. Mutations of human myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase cause temperature-sensitive myristic acid auxotrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4129-4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duronio, R. J., D. A. Rudnick, R. L. Johnson, D. R. Johnson, and J. I. Gordon. 1991. Myristic acid auxotrophy caused by mutation of S. cerevisiae myristoyl-CoA: protein N myristoyltransferase. J. Cell Biol. 113:1313-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duronio, R. J., D. A. Towler, R. O. Heuckeroth, and J. I. Gordon. 1989. Disruption of the yeast N-myristoyl transferase gene causes recessive lethality. Science 243:796-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farazi, T. A., G. Waksman, and J. I. Gordon. 2001. Structures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae N-myristoyltransferase with bound myristoyl-CoA and peptide provide insights about substrate recognition and catalysis. Biochemistry 40:6335-6343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giang, D. K., and B. F. Cravatt. 1998. A second mammalian N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6595-6598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorovits, R., K. A. Sjollema, J. H. Sietsma, and O. Yarden. 2000. Cellular distribution of COT1 kinase in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 30:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groll, A. H., P. M. Shah, C. Mentzel, M. Schneider, G. Just-Nuebling, and K. Huebner. 1996. Trends in the postmortem epidemiology of invasive fungal infections at a university hospital. J. Infect. 33:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris, S. D., A. F. Hofmann, H. W. Tedford, and M. P. Lee. 1999. Identification and characterization of genes required for hyphal morphogenesis in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 151:1015-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris, S. D., J. L. Morrell, and J. E. Hamer. 1994. Identification and characterization of Aspergillus nidulans mutants defective in cytokinesis. Genetics 136:517-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heath, I. B., G. Gupta, and S. Bai. 2000. Plasma membrane-adjacent actin filaments, but not microtubules, are essential for both polarization and hyphal tip morphogenesis in Saprolegnia ferax and Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 30:45-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, D. R., R. J. Duronio, C. A. Langner, D. A. Rudnick, and J. I. Gordon. 1993. Genetic and biochemical studies of a mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase, nmt72pLeu99-pro, that produces temperature-sensitive myristic acid auxotrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 268:483-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones, T. A., and S. Thirup. 1986. Using known substructures in protein model building and crystallography. EMBO J. 5:819-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kafer, E. 1977. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv. Genet. 19:33-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karki, R. G., and V. M. Kulkarni. 2001. A feature based pharmacophore for Candida albicans myristoyl-CoA: protein N-myristoyltransferase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 36:147-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishore, N. S., D. C. Wood, P. P. Mehta, A. C. Wade, T. Lu, G. W. Gokel, and J. I. Gordon. 1993. Comparison of the acyl chain specificities of human myristoyl-CoA synthetase and human myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:4889-4902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosmidou, E., P. Lunness, and J. H. Doonan. 2001. A type 2A protein phosphatase gene from Aspergillus nidulans is involved in hyphal morphogenesis. Curr. Genet. 39:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodge, J. K., E. Jackson-Machelski, B. Devadas, M. E. Zupec, D. P. Getman, N. Kishore, S. K. Freeman, C. A. McWherter, J. A. Sikorski, and J. I. Gordon. 1997. N-myristoylation of Arf proteins in Candida albicans: an in vivo assay for evaluating antifungal inhibitors of myristoyl-CoA: protein N-myristoyltransferase. Microbiology 143:357-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodge, J. K., E. Jackson-Machelski, D. L. Toffaletti, J. R. Perfect, and J. I. Gordon. 1994. Targeted gene replacement demonstrates that myristoyl-CoA: protein N-myristoyl transferase is essential for viability of Cryptococcus neoformans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12008-12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lodge, J. K., R. L. Johnson, R. A. Weinberg, and J. I. Gordon. 1994. Comparison of myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferases from three pathogenic fungi: Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 269:2996-3009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGoldrick, C. A., C. Gruver, and G. S. May. 1995. myoA of Aspergillus nidulans encodes an essential myosin I required for secretion and polarized growth. J. Cell Biol. 128:577-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer, K. H., and E. Schweizer. 1974. Saturated fatty acid mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with an intact fatty acid synthetase. J. Bacteriol. 117:345-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momany, M., and I. Taylor. 2000. Landmarks in the early duplication cycles of Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans: polarity, germ tube emergence and septation. Microbiology (Reading) 146:3279-3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Momany, M., P. J. Westfall, and G. Abramowsky. 1999. Aspergillus nidulans swo mutants show defects in polarity establishment, polarity maintenance and hyphal morphogenesis. Genetics 151:557-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osherov, N., and G. May. 2000. Conidial germination in Aspergillus nidulans requires RAS signaling and protein synthesis. Genetics 155:647-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osherov, N., R. A. Yamashita, Y. S. Chung, and G. S. May. 1998. Structural requirements for in vivo myosin I function in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27017-27025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocque, W. J., C. A. McWherter, D. C. Wood, and J. I. Gordon. 1993. A comparative analysis of the kinetic mechanism and peptide substrate specificity of human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:9964-9971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Seiler, S., F. E. Nargang, G. Steinberg, and M. Schliwa. 1997. Kinesin is essential for cell morphogenesis and polarized secretion in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 16:3025-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seiler, S., M. Plamann, and M. Schliwa. 1999. Kinesin and dynein mutants provide novel insights into the roles of vesicle traffic during cell morphogenesis in Neurospora. Curr. Biol. 9:779-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sikorski, J. A., B. Devadas, M. E. Zupec, S. K. Freeman, D. L. Brown, H. F. Lu, S. Nagarajan, P. P. Mehta, A. C. Wade, N. S. Kishore, M. L. Bryant, D. P. Getman, C. A. McWherter, and J. I. Gordon. 1997. Selective peptidic and peptidomimetic inhibitors of Candida albicans myristoylCoA: protein N-myristoyltransferase: a new approach to antifungal therapy. Biopolymers 43:43-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinberg, R. A., C. A. McWherter, S. K. Freeman, D. C. Wood, J. I. Gordon, and S. C. Lee. 1995. Genetic studies reveal that myristoyl CoA:protein N-myristoyl transferase is an essential enzyme in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 16:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weston, S. A., R. Camble, J. Colls, G. Rosenbrock, I. Taylor, M. Egerton, A. D. Tucker, A. Tunnicliffe, A. Mistry, F. Mancia, E. de la Fortelle, J. Irwin, G. Bricogne, and R. A. Pauptit. 1998. Crystal structure of the anti-fungal target N-myristoyl transferase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whittaker, S. L., P. Lunness, K. J. Milward, J. H. Doonan, and S. J. Assinder. 1999. sodVIC is an alpha-COP-related gene which is essential for establishing and maintaining polarized growth in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 26:236-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiegand, R. C., C. Carr, J. C. Minnerly, A. M. Pauley, C. P. Carron, C. A. Langner, R. J. Duronio, and J. I. Gordon. 1992. The Candida albicans myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase gene. Isolation and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:8591-8598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yarden, O., M. Plamann, D. J. Ebbole, and C. Yanofsky. 1992. cot-1, a gene required for hyphal elongation in Neurospora crassa, encodes a protein kinase. EMBO J. 11:2159-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yelton, M. M., J. E. Hamer, and W. E. Timberlake. 1984. Transformtaion of Aspergillus nidulans by using a trpC plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1470-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, L., E. Jackson-Machelski, and J. I. Gordon. 1996. Biochemical studies of Saccharomyces cerevisiae myristoyl-coenzyme A:protein N-myristoyltransferase mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33131-33140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]