Abstract

A feedlot trial was conducted to assess the efficacy of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 vaccine in reducing fecal shedding of E. coli O157:H7 in 218 pens of feedlot cattle in 9 feedlots in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Pens of cattle were vaccinated once at arrival processing and again at reimplanting with either the E. coli O157:H7 vaccine or a placebo. The E. coli O157:H7 vaccine included 50 μg of type III secreted proteins. Fecal samples were collected from 30 fresh manure patties within each feedlot pen at arrival processing, revaccination at reimplanting, and within 2 wk of slaughter.

The mean pen prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in feces was 5.0%; ranging in pens from 0% to 90%, and varying signif icantly (P < 0.001) among feedlots. There was no signif icant association (P > 0.20) between vaccination and pen prevalence of fecal E. coli O157:H7 following initial vaccination, at reimplanting, or prior to slaughter.

Résumé

Essai sur le terrain d’un vaccin contre Escherichia coli O157:H7 dans 9 parcs d’engraissement de l’Alberta et de la Saskatchewan. Un essai en parcs d’engraissement a été conduit afin de vérifier l’efficacité d’un vaccin contre Escherichia coli O157:H7 pour réduire l’élimination fécale de E. coli O157:H7 dans 218 enclos de 9 parcs d’engraissement de bovins en Alberta et en Saskatchewan. Les bestiaux ont été vaccinés au cours des procédures de réception en enclos et une 2ième fois lors de leur transfert avec le vaccin E. coli O157:H7 ou un placebo. Le vaccin E. coli O157:H7 comprenait 50 μg de protéines sécrétées de type III. Des échantillons fécaux ont été recueillis sur 30 bouses fraîches dans chaque enclos des parcs d’engraissement au cours des procédures de réception, à la revaccination lors du transfert et dans les 2 semaines précédant l’abattage.

La prévalence moyenne en enclos de E. coli O157:H7 dans les fèces était de 5 %, allant de 0 % à 90 % dans les enclos et variant significativement (P < 0,001) entre les parcs d’engraissement. Il n’y avait pas d’association significative (P > 0,20) entre la vaccination et la prévalence en enclos de E. coli 0157:H7 dans les fèces à la suite des différentes vaccinations : initiale, au transfert ou avant l’abattage.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Introduction

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is a bacterium that has been associated with foodborne and waterborne disease in humans (1). Cattle have been identified as a major source of the bacteria to humans (1–4). Currently, there are few effective preslaughter interventions to reduce the risk of shedding E. coli O157:H7 in feces or hide contamination in cattle.

Recently, an E. coli 0157:H7 vaccine was tested and shown to reduce the duration, frequency, and quantity of E. coli O157:H7 shed in cattle following experimental challenge (5). In addition, the experimental vaccine was shown to significantly reduce shedding of the organism under conditions of natural exposure (5). Further field studies were deemed necessary to evaluate the efficacy of the vaccine in cattle under commercial feedlot conditions in western Canada.

The purpose of the study described here was to determine the effectiveness of an E. coli O157:H7 vaccine in reducing fecal shedding of E. coli O157:H7 in pens of feedlot cattle.

Materials and methods

Feedlots

Commercial feedlots in Alberta and Saskatchewan that were known to the lead researcher were contacted to see if they would be willing to participate in the field trial. Eight feedlots in Alberta and 1 feedlot in Saskatchewan agreed to participate. The feedlots ranged in one-time capacity from approximately 10 000 to 35 000 head of cattle. The feedlot trial began October 2001 and continued until December 2002.

Feedlots were asked to provide pens of cattle that would remain together from arrival until slaughter for the entire trial period. They were also asked to ensure that pens of cattle from different vaccine groups did not share water bowls. Within a feedlot, either all calf or all yearling pens of cattle were on trial. Feedlots began the trial at different times, depending on availability of pens of cattle for the study.

Vaccinated pens of cattle for the trial within a feedlot were handled similarly for feedlot management procedures, such as processing, treating, feeding, and manure management. Feedlots kept vaccination, processing, and treatment records on the trial pens of cattle.

Vaccination

The unit of analysis in this field trial was the feedlot pen. Feedlots were each provided with a vaccination sheet that randomly allocated pens of cattle within the feedlot to 1 of the 2 vaccine groups. The number of pens per feedlot on trial ranged from 10 to 42 pens. In total, there were 218 pens on trial.

Two bottles, labeled “A” and “B,” were provided to each feedlot, so that the feedlot personnel were blind to the status of the vaccine. One bottle held the vaccine, which contained type III secreted proteins (Esps, Tir) from E. coli O157:H7 and was prepared by the Alberta Research Council Inc. (5). Type III secreted proteins are required for E. coli O157:H7 intestinal colonization (5). The adjuvant used in the vaccine formulation was an oil-water emulsion designed to be mixed directly with antigens (Emulsigen; MVP Laboratories, Ralston, Nebraska, USA) and included gentamicin. The total protein concentration was 25 μg/mL. The diluent was 0.85% sodium chloride. The other bottle held the placebo, which was the same as the vaccine but without the antigen.

Two milliliters of the vaccine (50 mg protein) were administered, SC, by injection in the neck of cattle at arrival processing and again at reimplanting (average 103 d on feed in calf pens, 73 d on feed in yearling pens). All cattle within a pen received the same vaccine.

Fecal samples

Fecal samples were collected from 30 fresh manure patties distributed throughout the pens of vaccinated cattle at arrival processing, revaccination at reimplanting, and within 2 wk of slaughter (average 221 d on feed in calf pens, 179 d on feed in yearling pens). This sample size is consistent with previous research to obtain reliable estimates of pen prevalence (6–8).

Ten grams of feces collected from each manure patty were placed in vials with transport media (Tryptic soy broth with vancomycin at 40 mg/L and cefixime at 0.05 mg/L) and sent by courier to the Vaccine & Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) in Saskatoon. Upon arrival, fecal samples were cultured for E. coli O157:H7 after immunomagnetic enrichment, as has been described previously (5).

Statistical analysis

All data were entered into a database and assessed by using statistical software (Statistix 7 for Windows; Analytical Software, Tallahassee, Florida, USA; SAS, Version 8; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The outcome measure was the proportion of fecal samples positive for E. coli O157:H7 within a pen. The fecal proportion was not normally distributed; thus, it was transformed by arcsin. A general linear model (GLM) analysis was performed evaluating the effects of vaccine, feedlot, age (calf or yearling) and the interactions among these 3 variables. Analyses of residuals from the GLM were examined for normality. Arcsin transformation was used for the final GLM, since it reduced deviation from normality better than did others, though it did not eliminate it. Because of the non-normality issue, 2 categorical analyses were done in addition to the GLM. First, the E. coli O157:H7 pen-prevalence data were collapsed into 3 levels: 0, > 0 to < 0.101, and > 0.10. Second, the pen prevalence data proportions were collapsed to any positives within a pen: “yes” or “no.” For both categorical analyses, the Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel statistic was computed to test for the association of fecal E. coli O157: H7 pen prevalence and vaccine, while controlling for feedlot.

Additionally, a signed rank test for paired data was performed in which data were collapsed to create a single mean for each vaccine group for each feedlot. A Wilcoxin Signed Rank Test was used to evaluate vaccine differences. Given the variability among feedlots, each feedlot was also examined individually to evaluate vaccine effect (Wilcoxin Rank Sum Test).

Results

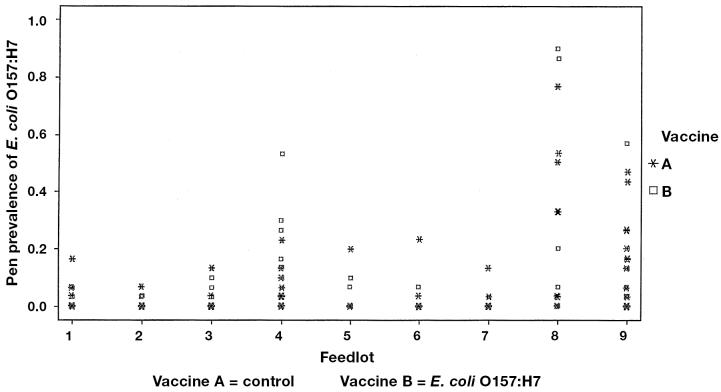

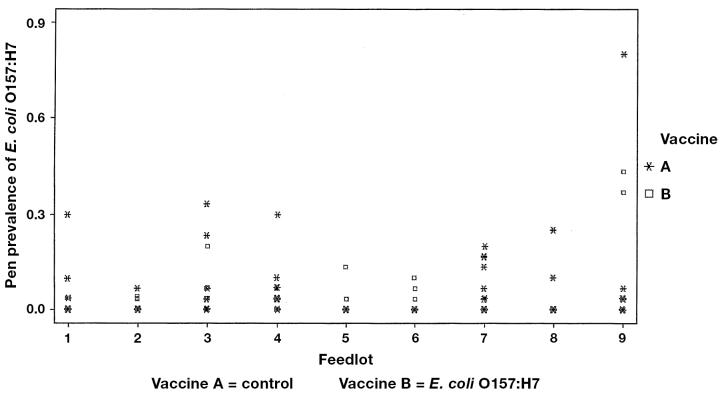

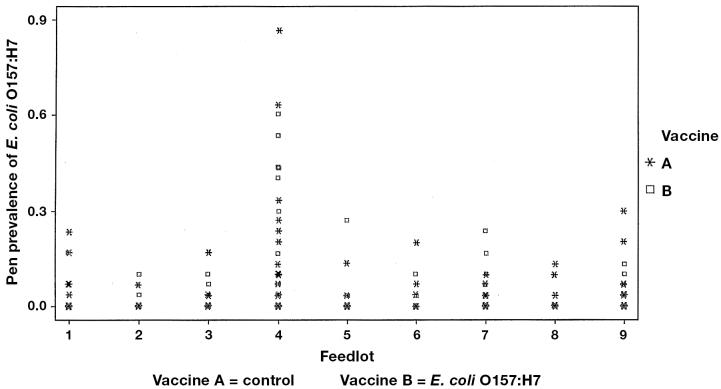

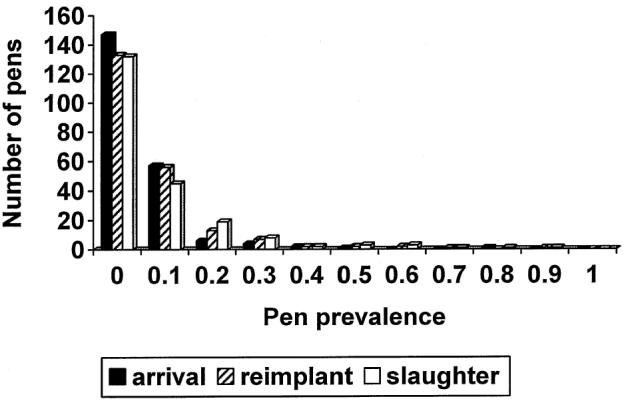

The proportions of pens positive and the mean within-pen prevalence by vaccine and sampling time are shown in Table 1. The pen prevalence was highly variable, ranging from 0% to 80% at arrival processing, 0% to 87% at revaccination, and 0% to 90% preslaughter (Figures 1 to 4). The pen prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in feces was significantly (P < 0.001) different among feedlots at arrival, revaccination, and preslaughter. No significant effect of age was observed. Due to the staging of sampling within each feedlot, season could not be separated from feedlot in the analyses. Controlling for feedlot and age of cattle, no significant association (P > 0.25) was found between vaccine and pen prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 (Figures 2 to 4) at any time point. Within any one feedlot, there was also no significant vaccine effect.

Table 1.

Proportion of feedlot pens positive and mean within pen prevalence by Escherichia coli O157:H7 vaccine and sampling time

| % positive pens

|

Mean (standard error) % within pen prevalence

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | E. coli O157:H7 vaccine | Control | E. coli O157:H7 vaccine | |

| Number of pens | 109 | 109 | 109 | 109 |

| Arrival processing | 34.9 | 30.3 | 4.0 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.6) |

| Revaccination | 41.3 | 35.8 | 5.5 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.1) |

| Slaughter | 37.6 | 38.5 | 6.6 (1.3) | 6.1 (1.4) |

Figure 1.

The prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the feces of 218 pens of feedlot cattle at arrival, reimplanting, and 2 wk before slaughter.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of E. coli O157 at slaughter.

Figure 2.

Feedlot prevalence of E. coli O157 at arrival.

Discussion

The E. coli O157:H7 vaccine did not significantly reduce the proportion of cattle in a feedlot pen shedding E. coli O157:H7 in their feces. In a previous feedlot trial (5), 3 doses of the similar vaccine formulation at 3-week intervals significantly (P = 0.04) reduced the average pen proportion of feedlot cattle shedding E. coli O157:H7 in feces from 21.3% to 8.8% during the 106-day feeding period from May to September. Failure to see a vaccine effect here may be due to a poor immunological response to the vaccine because of 1) alterations of protein confirmation and hence epitopic changes by formalin fixation or 2) a different vaccination strategy (interval between vaccinations and number of doses).

The vaccine used in this study was produced under scaled-up growth conditions rather than the laboratory-scale production process used to produce the experimental vaccine used in the previous feedlot trial (5), also the vaccine contained a different adjuvant called VSA3 (5). The adjuvant VSA3 contains an immunomodulatory compound to enhance immune responses. The antigen used in the present study was treated with formalin, which could possibly have altered the immunogenicity of the vaccine. Recent results from an experiment in which groups of animals were vaccinated with formulations produced with or without formalin suggest that treatment with formalin interferes with the protective capacity of the vaccine (unpublished observations). Further investigation is needed to evaluate whether formalin treatment changed protein conformation or the adjuvant chosen affected the immunological response to the antigens. Investigation indicated that the vaccines were handled, stored, and administered properly in the 2 feedlots.

In the previous feedlot study (5), where the vaccine showed a beneficial effect in reducing the pen proportion of animals shedding E. coli O157:H7, 3 doses of the vaccine were administered at 3-week intervals. In the present study, only 2 doses of the vaccine were given, at arrival processing and again at reimplanting, 73 to 103 d postarrival. Failure to see a beneficial response here may suggest that the time interval between repeat immunizations, the number of doses of vaccine, or both, were insufficient to induce protective immunity of sufficient duration until slaughter. Vaccinating feedlot cattle 3 times within a 3-week interval postarrival does not fit many feedlot management protocols and compliance would be difficult for such a vaccination strategy.

In the trial described here, the size of pens of feedlot cattle reflected commercial conditions, averaging 250 animals per pen. In the previous feedlot trial (5), pens of cattle contained only 8 animals. Additionally, the previous trial (5) was conducted over a shorter time frame (fewer days on feed) than described here. Both of these factors (pen size, days on feed) may also explain differences noted in vaccine efficacy.

The pen prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in feces was highly variable within and among feedlots studied here and as described previously (2–4). Some of the variability in pen prevalence among feedlots here may have reflected seasonal differences when the fecal sampling was conducted. Researchers do not have a good understanding of the reasons for this variability within and among feedlots (1–4). Large variability in pen prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in feces may make it difficult to detect vaccine effects, unless a very large sample size is used.

The pen prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in the feedlots studied here was much lower than that in the previous feedlot trial (5), which makes detecting a vaccine effect more difficult. However, in the feedlot trial here, 218 pens of cattle were vaccinated, of which 109 received the E. coli O157:H7 vaccine. With a mean pen prevalence of 5.0%, the sample size here had an 85% power of detecting a 50% vaccine efficacy.

The difference in pen prevalence between the 2 studies may reflect differences in fecal culture methods (rectal versus manure patty samples) or differences in the true prevalence of the bacteria in different geographic areas (western Canada versus Nebraska). Where possible, trials should try to standardize fecal sampling and culture methods, using the most sensitive and accurate techniques available.

Research should continue to identify why some pens within the same feedlot pens had a 90% fecal prevalence and other pens had a 0% fecal prevalence. Vaccination could then be targeted at high “risk” pens of cattle.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of E. coli O157 at revaccination.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the 9 feedlots that participated in the study. The authors are grateful to Gail McLeod, Robin Downen, Darren Malchow, Joanne MacDougall, and Sue Bygrove for vaccinating cattle and collecting the fecal samples. Gordon Crockford, Sandy Klashinsky, and Kingsley Amoako from the Vaccine & Infectious Disease Organization are thanked for conducting the culturing of fecal samples. Michael Best from the Alberta Research Council Inc. is acknowledged for producing the E. coli O157:H7 vaccine. The Alberta Research Council Inc. is the license holder of the vaccine technology developed by Dr. Brett Finlay and Dr. Andy Potter. Dr. Brett Finlay of the University of British Columbia provided valuable advice during the study and his assistance is acknowledged. CVJ

Footnotes

Funding provided by Alberta Agriculture Research Institute, Alberta Research Council Inc., Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network Centre of Excellence, and Bioniche Life Sciences.

References

- 1.Stewart CD, Flint HJ. Escherichia coli O157 in Farm Animals. New York: CABI Publ, 1999:147–168.

- 2.Sargeant JM, Sanderson MW, Smith RA, Griffin DD. Escherichia coli O157 in feedlot cattle feces and water in four major feeder-cattle states in the USA. Prev Vet Med. 2003;61:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(03)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith D, Blackford M, Younts S, et al. Ecological relationships between the prevalence of cattle shedding Escherichia coli O157: H7 and characteristics of the cattle or conditions of the feedlot pen. J Food Prot. 2001;64:1899–1903. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.12.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaitsa ML, Smith DR, Stoner JA, et al. Incidence, duration, and prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 fecal shedding by feedlot cattle during the finishing period. J Food Prot. 2003;66:1972–1977. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-66.11.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter AA, Klashinsky S, Li Y, et al. Decreased shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by cattle following vaccination with type III secreted proteins. Vaccine. 2004;22:362–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Donkersgoed J, Berg J, Potter A, et al. Environmental sources and transmission of E. coli O157:H7 in feedlot cattle. Can Vet J. 2001;42:714–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hancock DD, Rice DH, Thomas LA, Dargatz DA, Besser TE. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157 in feedlot cattle. J Food Prot. 1997;60:462–465. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.5.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dartgatz DA, Wells SJ, Thomas LA, Hancock DD, Garber LP. Factors associated with the presence of Escherichia coli O157 in feces of feedlot cattle. J Food Prot. 1997;60:466–470. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]