Abstract

Objectives

Evidence from multiple clinical trials showed that local consolidative therapy (LCT) improved survival in oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. In the present study, we aim to explore the potential role of microwave ablation (MWA) as LCT for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant advanced NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis.

Materials and methods

From January 2015 to December 2018, a total of 86 EGFR-mutant stage IIIB or IV NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis were enrolled for retrospective analysis. MWA was used as LCT for all oligometastatic lesions and/or primary tumors in 34 patients without progression after first-line EGFR-TKIs therapy (consolidation group), while the other 52 patients received only TKIs until disease progression (monotherapy group). We calculated and compared the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of the two groups.

Results and conclusion

Patients with MWA consolidation therapy had significantly improved PFS (median 16.7 vs. 12.9 months, HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.22–0.88, P = 0.02) and OS (median: 34.8 vs. 22.7 months, HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24–0.88, P = 0.04) than monotherapy group. MWA for LCT was identified as the independent predictive factor for better PFS (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.37–0.82, P < 0.01) and OS (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.33–0.91, P = 0.02). Most toxicities were mild and well tolerated. No patient had to discontinue EGFR-TKIs because of MWA complications. These findings suggest that MWA as local consolidative therapy after first-line EGFR-TKIs treatment leads to better disease control and survival than TKIs monotherapy in EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis. MWA as a novel option of LCT might be considered for clinical management of these patients.

Keywords: Microwave ablation, Local consolidative therapy, Oligometastasis, Non-small cell lung cancer, EGFR-TKIs

Introduction

Advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients harboring active epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations have high response and progression-free survival (PFS) rates when treated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (Mitsudomi et al. 2010; Soria et al. 2015; Rosell et al. 2012). EGFR-TKIs including gefitinib, erlotinib, icotinib and afatinib have been approved as the standard first-line therapy in advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations.

Approximately 70% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients have advanced disease at diagnosis and lose the opportunity of undergoing a curative treatment. However, advanced NSCLCs with five or fewer distant metastatic sites at initial diagnosis, termed as oligometastatic disease, represent an intermediate state between locally confined and widely metastatic cancer (Hellman and Weichselbaum 1995; Weichselbaum and Hellman 2011). Multiple clinical studies suggested that oligometastatic disease could benefit from local ablative therapy (e.g., surgery or radiotherapy) for consolidation to achieve long-term survival (Juan and Popat 2017; Khan et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2017). Recently published prospective randomized studies by Gomez et al. suggested that aggressive local consolidative therapy (LCT) with radiotherapy or surgery improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with oligometastatic NSCLCs that did not progress after front-line systemic therapy (Gomez et al. 2016, 2019). However, numbers of patients with active EGFR mutations enrolled in these studies were relatively small. The potential benefits of local consolidative therapy for this subgroup of patients warrant further investigation.

Image-guided percutaneous microwave ablation (MWA) as a newly developed minimally invasive technique has been increasingly used for the treatment of both primary and secondary pulmonary malignancies (Ye et al. 2018; Vogl et al. 2017; de Baere et al. 2016). MWA has been shown to have some advantages like safety, efficacy, and good local disease control while preserving most of the lung parenchyma for medically inoperable patients with NSCLC and oligometastatic disease (Yang et al. 2014, 2017, 2018). In addition, our previous results indicated that MWA with continued EGFR-TKIs was associated with favorable disease control in EGFR-mutated patients who developed acquired resistant extracranial oligoprogression (Ni et al. 2016, 2019). We hypothesize that local consolidative MWA can also improve the survival outcomes of advanced NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis that do not progress during first-line EGFR-TKI therapy. To address this issue, we conducted this study to investigate the potential benefits of local consolidative MWA therapy in combination with TKIs for EGFR-mutant advanced stage NSCLCs.

Methods

Patients

The clinical data of NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis at Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong First Medical University between January 2015 and December 2018 were identified and retrospectively analyzed. Patients who met the following criteria were enrolled: (1) pathologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC with EGFR sensitive mutation; (2) stage IIIB or IV disease according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, with synchronous oligometastatic disease (five or fewer metastases within 2 months of diagnosis in one to multiples organs, excluding primary tumor). The state of oligometastasis was assessed by systemic examination of either contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, bone scan, or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) and brain imaging (either contrast-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (3) receiving EGFR-TKIs as first-line treatment; (4) did not progress after first-line EGFR-TKI treatment; (5) ≥ 18 years old, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score < 2.

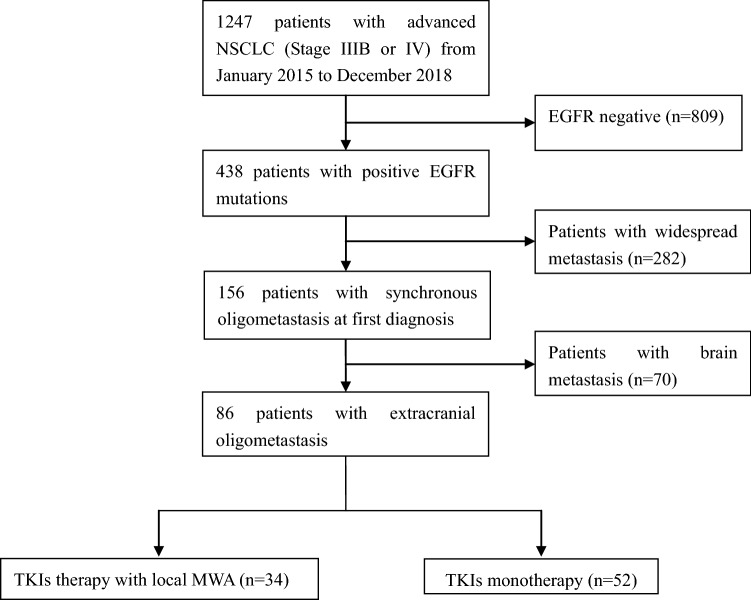

The exclusion criteria included: (1) patients who did not undergo a systemic examination prior to enroll in this study; (2) patients were diagnosed with synchronous brain metastasis at baseline; (3) first-line treatment with second or third generation of TKI. Patients’ selection steps are shown in Fig. 1. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong First Medical University and written informed consent to use the clinical data for research was obtained from each participant before the medical intervention started.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients’ treatments

Treatment procedures

First-generation EGFR-TKIs used in the study included: gefitinib (250 mg po per day), erlotinib (150 mg po per day), and icotinib (125 mg three times per day). All patients received routine surveillance imaging every 2 months after initial TKI treatment. Local MWA as LCT was performed for primary tumors and oligometastatic lesions before disease progression and continued TKIs were used as maintenance therapy. Detailed ablation procedures were as we previously described (Ni et al. 2016). One month after ablation, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was performed to determine the local response (complete or incomplete ablation) based on criteria as we previously described (Ye et al. 2018). Patients received contrast-enhanced CT or MR scan every 1–2 months after ablation to assess their response to treatment and to identify adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s Chi square (or Fisher’s exact) and t test were used to determine differences between groups. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time initiation of TKI treatment to first progression of disease or last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of diagnosis to the date of death from any case or last follow-up. Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test were used for survival analyses. Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). P values were two-sided and considered significant if < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows Version 17.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient characteristics

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 86 EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis were included in the present study (patients’ characteristics shown in Table 1). Thirty-four patients of them received local MWA with concurrent EGFR-TKIs, while the remaining 52 cases received TKI monotherapy. Clinical characteristics were well balanced between the two groups. The most common distant metastases were lung metastases (39.5% in consolidation therapy group, 32.4% in TKI monotherapy group), followed by liver, bone and adrenal gland metastases. In the consolidation therapy group, 30 out of 34 cases received MWA for their primary tumors. In addition, 43 oligometastatic lesions were ablated. The mean size of the metastatic lesions was 2.9 cm (range 1–5.6 cm).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Variables | MWA consolidation therapy (n = 34) | TKIs monotherapy (n = 52) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median (IQR) | 64 (43–78) | 63 (55–83) | 0.57 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 11 (32.4) | 14 (26.9) | |

| Female | 23 (67.6) | 38 (73.1) | 0.59 |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0–1 | 27 (79.4) | 36 (69.2) | |

| 2 | 7 (20.6%) | 16 (30.8) | 0.30 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 29 (85.3) | 49 (94.2) | |

| Adenosquamous | 4 (11.8) | 3 (5.8) | |

| NSCLC, undefined | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0.27 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 24 (70.6) | 40 (76.9) | |

| Former smoker | 7 (20.6) | 10 (19.2) | |

| Present smoker | 3 (8.8) | 2 (3.9) | 0.69 |

| EGFR mutation status | |||

| 19del | 16 (47.1) | 30 (57.7) | |

| 21L858R | 18 (52.9) | 21 (40.4) | |

| Others | 0 | 1 (1.9) | 0.41 |

| Nodal status | |||

| N0/N1 | 13 (38.2) | 24 (46.2) | |

| N2/N3 | 21 (61.8) | 28 (53.8) | 0.47 |

| Oligometastasis location | |||

| Lung | 17 (39.5) | 24 (32.4) | |

| Liver | 10 (23.3) | 15 (20.3) | |

| Bone | 6 (14.0) | 17 (23.0) | |

| Adrenal gland | 7 (16.2) | 10 (13.5) | |

| Chest wall | 3 (7.0) | 8 (10.8) | 0.70 |

| Number of oligometastases | |||

| 1–3 | 29 (85.3) | 46 (88.5) | |

| 4–5 | 5 (14.7) | 6 (11.5) | 0.67 |

| Best response to first-line TKIs | |||

| CR | 0 | 1 (1.9) | |

| PR | 23 (67.6) | 35 (67.3) | |

| SD | 11 (32.4) | 16 (30.8) | 0.72 |

| Primary tumors ablation | |||

| Yes | 30 (88.2) | – | |

| No | 4 (11.8) | – | |

Outcomes

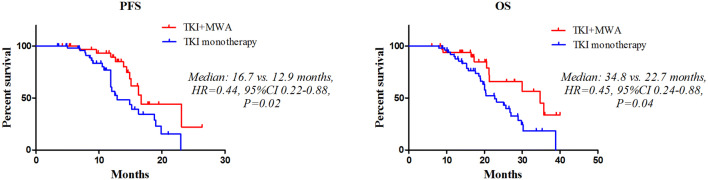

The median follow-up for this study was 36 months (range 6.1–42 months). Patients treated with MWA combined with TKIs had significantly improved PFS (median 16.7 vs. 12.9 months, HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.22–0.88, P = 0.02) (Fig. 2a) and OS (median 34.8 vs. 22.7 months, HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24–0.88, P = 0.04) (Fig. 2b) than TKI monotherapy group. We then examined the association of clinical variables with PFS and OS. Univariate analysis showed that initial best response to TKI (P = 0.02) and consolidation therapy (P < 0.01) was associated with better PFS, while consolidation therapy was only predictor of prolonged OS (P = 0.01) (Table 2). Multivariate analysis revealed MWA consolidation therapy as an independent predictive factor for better PFS (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.37–0.82, P < 0.01) and OS (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.33–0.91, P = 0.02) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

PFS and OS between MWA consolidation group and TKIs monotherapy group

Table 2.

Results of Cox regression analyses

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Univariate Cox regression analysis for PFS and OS | ||||||

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.24 | 0.85–4.33 | 0.37 | 1.46 | 0.36–3.55 | 0.55 |

| Age (≥ 65 vs. < 65) | 0.51 | 0.22–1.89 | 0.27 | 0.87 | 0.73–5.67 | 0.34 |

| ECOG score (0–1 vs. 2) | 0.98 | 0.77–5.67 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.56–7.93 | 0.51 |

| Smoking history (never smoker vs. present or former smoker) | 1.66 | 0.56–2.67 | 0.21 | 1.56 | 0.78–3.78 | 0.33 |

| Histology (adenocarcinoma vs. others) | 0.78 | 0.39–2.11 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.32–1.73 | 0.23 |

| EGFR mutation type (19 del vs. 21 L858R) | 1.12 | 0.55–1.67 | 0.11 | 1.76 | 0.47–4.21 | 0.28 |

| Nodal status (N0/N1 vs. N2/N3) | 1.89 | 0.87–2.11 | 0.54 | 1.32 | 0.78–3.22 | 0.67 |

| Initial best response to TKI (CR + PR vs. SD) | 0.66 | 0.32–0.87 | 0.02 | 0.76 | 0.39–1.19 | 0.11 |

| Oligometastasis location (lung vs. other sites) | 0.91 | 0.74–3.65 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 0.47–3.24 | 0.27 |

| Number of oligometastases (1–3 vs. 4–5) | 0.46 | 0.23–1.98 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.34–1.77 | 0.22 |

| Primary tumors ablation (yes vs. no) | 0.79 | 0.45–1.98 | 0.24 | 0.74 | 0.54–2.63 | 0.33 |

| Treatment (MWA consolidation vs. TKIs monotherapy) | 0.53 | 0.23–0.79 | < 0.01 | 0.73 | 0.55–0.91 | 0.01 |

| Multivariable Cox regression analysis for PFS and OS | ||||||

| Best response to TKI (CR + PR vs. SD) | 0.79 | 0.47–1.22 | 0.19 | – | – | – |

| Treatment (MWA consolidation vs. TKIs monotherapy) | 0.46 | 0.37–0.82 | < 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.33–0.91 | 0.02 |

Treatment complications and toxicity

Most MWAs were well tolerated. No perioperative mortality was observed during ablation procedures or within 30 days after MWA. Pain was the predominant side effect and 20 patients (58.8%) suffered mild or moderate pain after ablation, but no severe post-ablation pain occurred. Post-ablation pneumothorax image findings were observed in 8 (18.6%) patients who received lung ablation, while 4 (9.3%) of them received chest tube drainage. Post-ablation syndrome including fever (below 38.5 °C), fatigue, general malaise, nausea, and vomiting, etc., occurred in 11 patients. The most common toxicities caused by TKIs included skin rash, diarrhea, neutropenia, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, alanine aminotransferase, and pneumonitis. Most toxicities were grade 1–2 and well tolerated. No TKI-related interstitial lung disease was observed in both groups. There was no patient that discontinued TKIs because of MWA complications.

Discussion

The concept of the oligometastatic state raised by Hellman and Weichselbaum (Hellman and Weichselbaum 1995) in 1995 consists of a particular subgroup of patients with metastases limited in number and location, representing an intermediate state between locally confined and widely metastatic cancer. A prolonged median OS was also reported for patients with oligometastatic disease than those with widespread lesions (Parikh et al. 2014). Several previously published studies have supported a role of local consolidative therapy in oligometastatic NSCLC. Gomez et al. (2016) reported results of the first multi-institutional, randomized study that examined the efficacy of LCT on PFS in NSCLC patients with three or fewer metastases. For all enrolled patients with oligometastatic NSCLC who did not progress after initial systemic therapy, the median PFS was longer for patients who received aggressive LCT including surgery and/or radiotherapy to oligometastatic lesions followed by standard maintenance treatment than for those who received maintenance treatment or observation alone (11.9 vs 3.9 months). In addition, LCT also contributed to increase the time to appearance of new sites of disease (Gomez et al. 2016). More recently, they presented the updated PFS and OS data in the same group of patients and also found an OS benefit in the LCT arm (Gomez et al. 2019). However, the small sample of EGFR-mutant NSCLCs (6/49, 12%) limits the significance of LCT for patients in this category. A relatively larger scale retrospective study including 145 stage IV EGFR-mutant NSCLCs with no more than 5 metastases within 2 months of diagnosis further explored the role of LCT for this subgroup of patients. In comparison with patients who did not receive any consolidative local ablative therapy, LCT to oligometastatic sites significantly improved the median PFS (20.6 vs 13.9 months). In addition, improved PFS was associated with prolonged OS in the LCT group (40.9 vs 30.8 months), especially in those with primary tumor ablation (40.5 vs 31.5 months), brain metastases (38.2 vs 29.2 months) and adrenal metastases (37.1 vs 29.2 months) (Xu et al. 2018). Recently, the same team also found that addition of local therapy to EGFR-TKIs was associated with a significantly longer PFS and OS in EGFR-mutant NSCLC with oligometastatic or oligoprogressive liver metastases (Jiang et al. 2019). Generally, adverse events in these studies were well tolerated and similar between groups.

Our previously published studies indicated that MWA to only primary lung lesions plus EGFR-TKIs as front-line therapy tend to improve survival, whereas statistical significance was not reached in EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC (Wei et al. 2017). In the present study, progression-free survival in the TKIs monotherapy group (12.9 months) was similar to that proposed in previous studies (Mitsudomi et al. 2010). However, PFS in the consolidation therapy group was significantly prolonged (16.7 vs. 12.9 months) for patients that received MWA. Improved PFS also led to better OS for the same group of patients. Moreover, MWA for consolidation therapy was identified as the independent predictive factor for favorable prognosis, indicating that MWA for metastatic lesions and primary tumors is necessary and should be suggested for EGFR-mutant extracranial oligometastatic NSCLC patients that did not progress after first-line TKI treatment. Local ablative treatments applied in the previously published studies mainly included surgery and radiotherapy, while percutaneous thermal ablation (mainly radiofrequency ablation, RFA) was only used in some cases of liver metastases. In contrast to other ablation techniques, studies with MWA have shown advantages in large tumors, in locations around large vessels and in highly perfused areas (Pusceddu et al. 2019; Vogl et al. 2017; Solbiati 2018; Song et al. 2017). In this study, we used MWA for primary and oligometastatic lesions and showed its potential clinical benefits. The majority of complications by MWA were mild and well tolerated, which supports the safety of MWA as LCT for extracranial oligometastatic NSCLC patients. The most common complication in the present study was post-ablation pain, usually self-limiting. No grade 3 or greater toxicities were observed. Although acute complications of MWA appear to outweigh those of surgery or radiotherapy, late complications seem to be rare following ablation treatment.

There were still some limitations of our study. First, this is a single center retrospective study with small sample size; second, we excluded patients with brain metastases that are not suitable for MWA treatment in this study. As cerebral metastases are common in advanced stage NSCLC (30–50%) (Inal et al. 2018), further investigations are warranted to identify the potential role of MWA in combination with radiation therapy for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who developed brain metastases.

In conclusion, our results in this study indicated that MWA as local consolidative therapy after first-line EGFR-TKIs treatment leads to better PFS and OS than TKIs monotherapy in EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC patients with extracranial oligometastasis. Addition of MWA to EGFR-TKIs should be suggested for EGFR-mutant extracranial oligometastatic NSCLC patients that did not progress after first-line TKI treatment. Larger multicenter prospective studies are needed to further confirm the efficacy of MWA for this group of patients.

Acknowledgements

This study received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502610).

Abbreviations

- LCT

Local consolidative therapy

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- MWA

Microwave ablation

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- HR

Hazard ratio

- TKIs

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- CT

Computed tomography

- PET-CT

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- PS

Performance status

- CI

Confidence interval

Compliance ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong First Medical University and written informed consent to use the clinical data for research was obtained from each participant before the medical intervention started.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- de Baere T, Tselikas L, Catena V, Buy X, Deschamps F, Palussiere J (2016) Percutaneous thermal ablation of primary lung cancer. Diagn Interv Imaging. 97(10):1019–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez DR, Blumenschein GR Jr, Lee JJ, Hernandez M, Ye R, Camidge DR et al (2016) Local consolidative therapy versus maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer without progression after first-line systemic therapy: a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 17(12):1672–1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, Blumenschein GR Jr, Hernandez M, Lee JJ et al (2019) Local consolidative therapy vs. maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of a multi-institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 8:JCO1900201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR (1995) Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol 13(1):8–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inal A, Kodaz H, Odabas H, Duran AO, Seker MM, Inanc M et al (2018) Prognostic factors of patients who received chemotherapy after cranial irradiation for non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases: a retrospective analysis of multicenter study (Anatolian Society of Medical Oncology). J Cancer Res Ther. 14(3):578–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Chu Q, Wang H, Zhou F, Gao G, Chen X et al (2019) EGFR-TKIs plus local therapy demonstrated survival benefit than EGFR-TKIs alone in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with oligometastatic or oligoprogressive liver metastases. Int J Cancer 144(10):2605–2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan O, Popat S (2017) Ablative therapy for oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 18(6):595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AJ, Mehta PS, Zusag TW, Bonomi PD, Penfield Faber L, Shott S et al (2006) Long term disease-free survival resulting from combined modality management of patients presenting with oligometastatic, non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). Radiother Oncol 81(2):163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Hoang CD, Kesarwala AH, Schrump DS, Guha U, Rajan A (2017) Role of local ablative therapy in patients with oligometastatic and oligoprogressive non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 12(2):179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J et al (2010) Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 11(2):121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y, Bi J, Ye X, Fan W, Yu G, Yang X et al (2016) Local microwave ablation with continued EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor as a treatment strategy in advanced non-small cell lung cancers that developed extra-central nervous system oligoprogressive disease during EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment: a pilot study. Medicine (Baltimore). 95(25):e3998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y, Liu B, Ye X, Fan W, Bi J, Yang X et al (2019) Local thermal ablation with continuous EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancers that developed extra-central nervous system (CNS) oligoprogressive disease. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 42(5):693–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh RB, Cronin AM, Kozono DE, Oxnard GR, Mak RH, Jackman DM et al (2014) Definitive primary therapy in patients presenting with oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 89(4):880–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusceddu C, Melis L, Sotgia B, Guerzoni D, Porcu A, Fancellu A (2019) Usefulness of percutaneous microwave ablation for large non-small cell lung cancer: a preliminary report. Oncol Lett. 18(1):659–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E et al (2012) Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13(3):239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbiati LA (2018) A valuable guideline for thermal ablation of primary and metastatic lung tumors. J Cancer Res Ther 14(4):725–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Qi H, Zhang H, Xie L, Cao F, Fan W et al (2017) Microwave ablation: results with three different diameters of antennas in ex vivo bovine and in vivo porcine liver. J Cancer Res Ther 13(5):737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria JC, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Kim SW, Yang JJ, Ahn MJ et al (2015) Gefitinib plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on first-line gefitinib (IMPRESS): a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 16(8):990–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl TJ, Nour-Eldin NA, Albrecht MH, Kaltenbach B, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Lin H et al (2017a) Thermal ablation of lung tumors: focus on microwave ablation. Rofo. 189(9):828–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl TJ, Nour-Eldin NA, Hammerstingl RM, Panahi B, Naguib NNN (2017b) Microwave ablation (MWA): basics, technique and results in primary and metastatic liver neoplasms—review article. Rofo. 189(11):1055–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Ye X, Yang X, Zheng A, Huang G, Li W et al (2017) Microwave ablation combined with EGFR-TKIs versus only EGFR-TKIs in advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR-sensitive mutations. Oncotarget. 8(34):56714–56725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S (2011) Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 8(6):378–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Zhou F, Liu H, Jiang T, Li X, Xu Y et al (2018) Consolidative local ablative therapy improves the survival of patients with synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC harboring EGFR activating mutation treated with first-line EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol. 13(9):1383–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Ye X, Zheng A, Huang G, Ni X, Wang J et al (2014) Percutaneous microwave ablation of stage I medically inoperable non-small cell lung cancer: clinical evaluation of 47 cases. J Surg Oncol 110(6):758–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Ye X, Huang G, Han X, Wang J, Li W et al (2017) Repeated percutaneous microwave ablation for local recurrence of inoperable stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 13(4):683–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Ye X, Lin Z, Jin Y, Zhang K, Dong Y et al (2018) Computed tomography-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for treatment of peripheral ground-glass opacity-lung adenocarcinoma: a pilot study. J Cancer Res Ther. 14(4):764–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Fan W, Wang H, Wang J, Wang Z, Gu S et al (2018) Expert consensus workshop report: guidelines for thermal ablation of primary and metastatic lung tumors (2018 edition). J Cancer Res Ther. 14(4):730–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]