Abstract

Background

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a chronic, unpredictable disease. Long‐term prophylactic treatments that offer durable efficacy, safety, and convenience are required to assist patients in achieving complete disease control, per international guidelines. We report an interim analysis of an ongoing phase 3 (VANGUARD) open‐label extension (OLE) study evaluating the long‐term safety and efficacy of garadacimab for HAE prophylaxis.

Methods

Adults and adolescents aged ≥12 years with HAE previously participating in phase 2 and pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) studies were rolled over to an OLE, alongside newly enrolled patients. Patients received garadacimab 200 mg subcutaneously, once monthly for ≥12 months. The primary endpoint was treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in patients with C1 inhibitor deficiency/dysfunction.

Results

At data cut‐off (February 13, 2023; N = 161), median (interquartile range) exposure was 13.8 months (11.9–16.3). For the primary endpoint, 133/159 patients experienced ≥1 TEAE (524 events), equivalent to 0.23 events/administration and 2.84 events/patient‐year. Garadacimab‐related TEAEs (13% of patients, 52 events) were most commonly injection‐site reactions (ISRs). No deaths occurred. One patient discontinued treatment due to garadacimab‐related moderate ISR. Most TEAEs were mild/moderate; three events were serious (COVID‐19, two events; abdominal HAE attack, one event) and not garadacimab related. No abnormal bleeding, thromboembolic, severe hypersensitivity, or anaphylactic events were observed. Mean HAE attack rate decreased by 95% from the run‐in period; 60% of patients were attack‐free. Almost all patients (93%) rated their response to garadacimab as “good” or “excellent.”

Conclusion

Garadacimab has a favorable safety profile suitable for long‐term use and provides durable protection against HAE attacks.

Keywords: factor XIIa, garadacimab, hereditary angioedema, long‐term prophylaxis, monoclonal antibody

The ongoing phase 3 (VANGUARD) OLE study evaluated the long‐term safety and efficacy of garadacimab (FXIIa inhibitor) for HAE prophylaxis. Garadacimab demonstrated a favorable safety profile. Most patients were attack‐free, and substantial attack rate reduction was sustained. Garadacimab showed durable protection against attacks, a favorable long‐term safety profile, and high patient‐reported satisfaction, making it suitable for long‐term HAE prophylaxis.Abbreviations: AESI, adverse event of special interest (abnormal bleeding, thromboembolic, hypersensitivity, or anaphylaxis events); FXIIa, activated factor XII; HAE, hereditary angioedema; ISR, injection‐site reaction; OLE, open‐label extension; q1m, once monthly; SAE, serious adverse event; SC, subcutaneous; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- AE‐QoL

Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire

- AESI

adverse event of special interest

- C1INH

C1 inhibitor

- C4

complement factor 4

- CI

confidence interval

- EAACI

European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- FXIIa

activated factor XII

- HAE

hereditary angioedema

- HAE‐C1INH

hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency or dysfunction

- HAE‐nC1INH

hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor

- ICH

International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use

- IGART

Investigator's Global Assessment of Response to Therapy

- IQR

interquartile range

- ISR

injection‐site reaction

- LTP

long‐term prophylaxis

- ODT

on‐demand treatment

- OLE

open‐label extension

- QoL

quality of life

- SAE

serious adverse event

- SC

subcutaneous

- SD

standard deviation

- SGART

Subject's Global Assessment of Response to Therapy

- TEAE

treatment‐emergent adverse event

- WAO

World Allergy Organization

- WPAI

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

1. INTRODUCTION

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disease with an estimated global prevalence of approximately 1 in 50,000–100,000. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 HAE is characterized by recurrent episodes (attacks) of disfiguring swelling, most commonly affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and upper airways; attacks involving the tongue and larynx are potentially life‐threatening. 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 The unpredictable nature of attacks can substantially impair quality of life (QoL) by impacting daily activities, work, and mental health, resulting in considerable lifestyle modifications. 4 , 9 , 10 Current World Allergy Organization/European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (WAO/EAACI) guidelines state that the goals of HAE treatment are to achieve complete disease control and normalize patients' lives; presently, this can only be achieved with long‐term prophylaxis (LTP). 4 Although currently available LTP options are efficacious, they may not be convenient for all patients as some require frequent dosing (e.g., once‐daily berotralstat, lanadelumab every 2 weeks initially), some are administered intravenously (e.g., plasma‐derived C1 inhibitor [C1INH]), and others are given in variable doses (e.g., subcutaneous [SC] C1INH). 4 , 11 , 12 Despite sharing the same mechanism of action for kallikrein inhibition, berotralstat and lanadelumab differ in efficacy. 4 , 11 , 12 , 13 This indicates that there remains a need for additional LTP options with alternative mechanisms of action, durable efficacy, a favorable safety profile, and convenient administration (with regard to frequency, route, and fixed dosing) to optimize patient compliance. Such therapies will provide greater opportunity for treatment optimization and achieving complete disease control. 4 , 14

Prior phase 2 and pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) studies demonstrated the safety and efficacy of garadacimab, an activated factor XII (FXIIa)‐targeted monoclonal antibody, as an LTP treatment for HAE. 15 , 16 In the phase 3 study, garadacimab 200 mg SC once monthly significantly lowered HAE attack rate in adults and adolescents versus placebo (mean difference 87%; median difference 100%; p < .001). 15 Notably, 62% of patients receiving garadacimab were attack‐free throughout the 6‐month study versus 0% of patients receiving placebo. 15 Patients receiving garadacimab experienced substantial improvements in QoL, measured by the Angioedema Quality of Life questionnaire (AE‐QoL) score, as early as Day 31; this was further improved by the study end, corresponding with sustained efficacy. 15 Overall, garadacimab demonstrated a favorable safety profile. 15

As patients with HAE require lifelong treatment, evaluation of LTP treatments over an extended duration is critical. 17 Therefore, patients who had participated in these studies were eligible to roll over into an open‐label extension (OLE) (NCT04739059), alongside newly enrolled patients. 18 Here, we report the results of an interim analysis of the OLE evaluating the long‐term safety and efficacy of garadacimab for preventing HAE attacks.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and patients

The phase 3 (VANGUARD) OLE is a multicenter, open‐label, single‐arm study evaluating the long‐term safety and efficacy of garadacimab 200 mg SC once monthly in adults and adolescents aged ≥12 years with HAE. It is being conducted in 44 centers globally, in Australia (three centers), Canada (five), Czechia (two), Germany (four), Hong Kong (one), Hungary (one), Israel (one), Japan (10), Netherlands (one), New Zealand (one), Russia (one), Spain (two), Taiwan (one), and the USA (11). 18 Patients will receive ≥12 months of treatment, and the estimated primary completion date is November 2025.

Patients entered the OLE study as rollover patients from the prior phase 2 or pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) studies, or as newly enrolled patients (Figure S1). In the prior studies, eligible patients were aged 18–65 years (phase 2) or ≥12 years (phase 3) with clinically and laboratory‐confirmed HAE with C1INH deficiency or dysfunction (HAE‐C1INH types 1 and 2, respectively); additionally, patients who had HAE with normal C1INH (HAE‐nC1INH) with either a FXII or PLG mutation were eligible for enrollment in the phase 2 study and therefore eligible to roll over to the OLE. Full eligibility criteria for these studies have been published previously. 15 , 16 Rollover patients were required to have completed their prior study before entering the OLE study.

For newly enrolled patients to enter the phase 3 (VANGUARD) OLE, key inclusion criteria were age ≥12 years and confirmed HAE‐C1INH based on clinical history consistent with HAE, C1INH antigen concentration and/or functional activity ≤50% of normal, and complement factor 4 (C4) antigen concentration below the lower limit of the reference range (<16 mg/dL). Patients were required to have had ≥3 HAE attacks during the 3 months prior to screening. Patients with HAE‐nC1INH were ineligible to be newly enrolled. Full eligibility criteria for newly enrolled patients are provided in Appendix S1.

Rollover patients had already completed screening and run‐in during their prior studies and therefore entered the OLE treatment period directly. 15 , 16 Regardless of prior treatment arm, rollover patients received garadacimab 200 mg SC once monthly in the OLE. After screening, newly enrolled patients underwent a run‐in period to determine baseline HAE attack rate (Table S1). Upon entering the treatment period, they received a loading dose of garadacimab 400 mg SC followed by garadacimab 200 mg SC once monthly. For all patients, garadacimab was prepared in a prefilled syringe which, after training, was self‐administered at home or supervised at the study site (Tables S2 and S3). Other HAE prophylactic treatments were prohibited during the entire study, but on‐demand treatments (ODTs) were permitted as per the patient's treatment plan (Appendix S1). The planned duration of treatment is ≥12 months.

This study was conducted under a US Food and Drug Administration Biologics License Application, in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Good Clinical Practice guidelines, all applicable national and local regulations, and standard operating procedures for clinical research and development at CSL Behring. Informed consent or assent was obtained from patients or their legal representatives before screening. Consent forms and the trial protocol were approved by the ethics committee or institutional review board. For Japanese sites, the head of site submitted a written report to the board detailing all safety‐related information reported by the funding source. An independent data monitoring committee provided statistical and clinical oversight.

2.2. Outcome measures

The primary safety endpoint was treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in patients with HAE‐C1INH, including the number/percentage of TEAEs, the number/proportion of patients with TEAEs, and TEAE rates per administration of the study drug and per patient‐year. Secondary safety endpoints in the overall population (patients with HAE‐C1INH or HAE‐nC1INH) included the number/proportion of patients experiencing TEAEs related to garadacimab, TEAEs leading to death, TEAEs leading to study discontinuation, TEAEs by severity, serious adverse events (SAEs), adverse events of special interest (AESIs) per protocol (defined as abnormal bleeding, thromboembolic events, severe hypersensitivity, and anaphylaxis), laboratory findings reported as adverse events (AEs), and anti‐garadacimab antibodies. The Appendix S1 defines AEs and causality.

Secondary efficacy endpoints comprised the time‐normalized number of HAE attacks per month (attack rate) during the run‐in and treatment periods; the reduction in attack rate during treatment versus run‐in; the number of patients experiencing ≥50%, ≥90%, or 100% (attack‐free) reduction in attack rate from run‐in; the number of attacks requiring ODT; the number of moderate and severe attacks; and the proportion of patients rating their response to therapy as “good” or “excellent” using the Subject's Global Assessment of Response to Therapy (SGART) at Month 12 (Appendix S1). Exploratory QoL endpoints included Investigator's Global Assessment of Response to Therapy (IGART) at Month 12, reported here. Other QoL measures, such as Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) and AE‐QoL, will be published elsewhere.

2.3. Procedures

Patients were requested to record symptoms of potential attacks in electronic diaries (eDiaries) and contact the study site within 72 h after attack onset. Investigators confirmed attacks and attack severity upon eDiary review (Appendix S1). Site visit schedules and assessments during screening, run‐in, and treatment are detailed in Tables S1–S3. Laboratory assessments for pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity are described in Tables S4 and S5; pharmacokinetics data will be reported elsewhere.

Race, ethnicity, and sex were self‐reported by the patient according to a list of classifications; if racial identity was multiracial, then all applicable races were selected.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The sample size was based on the ICH E1A guideline rather than a statistical sample size calculation. 19 A minimum of 100 patients receiving treatment for ≥12 months was estimated, to allow for observation of ≥1 AE with a probability of 3% with 95% confidence. The results are reported with descriptive statistics, and there was no hypothesis testing. Multiplicity adjustment according to the Šidák method was performed for the exploratory QoL endpoints to ensure an overall 5% error rate.

The primary safety analysis was performed in patients with HAE‐C1INH, while secondary safety analyses were performed in the overall population (comprising patients with HAE‐C1INH or HAE‐nC1INH). All secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed using the overall population.

Continuous variables are presented using mean values with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard deviation (SD) and median values with corresponding interquartile ranges (IQRs).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

Overall, 161 patients entered the phase 3 (VANGUARD) OLE study, consisting of 92 rollover patients and 69 newly enrolled patients (Figure S2). The rollover group included 35 patients from the phase 2 study and 57 patients from the pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) study. 16 At the data cut‐off for this interim analysis (February 13, 2023), the median garadacimab exposure in the OLE was 13.8 months (IQR, 11.86–16.33; range, 3.0–21.1); 119 patients (74%) had garadacimab exposure of ≥12 months and 55 (34%) had ≥15 months. The majority of patients were female (63%) and White (84%); the mean (SD) age was 42.3 years (15.3), and all patients had HAE‐C1INH except for two patients with HAE‐nC1INH who had rolled over from the phase 2 study (Table 1). There were 151 adults (aged ≥18 years) and 10 adolescents (aged 12–17 years).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics (overall population).

| Characteristic | Garadacimab 200 mg (N = 161) |

|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 101 (62.7) |

| Mean (SD) age at screening [range], years | 42.3 (15.3) [13–73] |

| Mean (SD) body mass index at baseline a | 28.1 (6.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 |

| Asian | 22 (13.7) |

| Black or African American | 2 (1.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 |

| White | 135 (83.9) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) |

| Multiple | 1 (0.6) |

| HAE type, n (%) | |

| Type 1 | 145 (90.1) |

| Type 2 | 14 (8.7) |

| HAE‐nC1INH | 2 (1.2) b |

| Patient age group at diagnosis, n (%) c | |

| ≤17 years | 10 (6.2) |

| >17 years | 151 (93.8) |

| ≤65 years | 148 (91.9) |

| >65 years | 13 (8.1) |

| Patients receiving prophylactic therapy during 3 months before screening, n (%) | 59 (36.6) |

| Mean (95% CI) number of HAE attacks during the 3 months before screening or at the start of prophylaxis d | 9.3 (8.2–10.4) |

| Mean (95% CI) number of HAE attacks during the run‐in period e | 4.7 (4.2–5.1) |

| History of laryngeal attacks, n (%) | 103 (64.0) |

| Location of HAE attacks during the 3 months before screening, n (%) | |

| Cutaneous (extremities) | 124 (77.0) |

| Abdominal | 123 (76.4) |

| Facial | 51 (31.7) |

| Trunk | 16 (9.9) |

| Throat | 15 (9.3) |

| Peripheral | 1 (0.6) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HAE, hereditary angioedema; HAE‐nC1INH, hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor; SD, standard deviation.

Body mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Both patients had HAE‐nC1INH with an FXII mutation.

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

For patients not receiving HAE prophylaxis, the number of HAE attacks during the 3 months before screening was calculated; for patients receiving HAE prophylaxis, the number of HAE attacks during the 3 months before the start of prophylaxis was calculated.

95% CI based on t‐distribution.

3.2. Primary and secondary safety endpoints

In the primary safety analysis set (N = 159; excluding patients with HAE‐nC1INH) for the primary safety endpoint, 133 patients (84%) experienced ≥1 TEAE, with a total of 524 TEAEs reported (Table 2). The TEAE rate per administration was 0.23, and the TEAE rate per patient‐year was 2.84.

TABLE 2.

Summary of adverse events (primary safety analysis set and overall population).

| Adverse event, n (%) [E] a | Garadacimab 200 mg (N = 161) |

|---|---|

| Primary safety endpoints in patients with HAE‐C1INH (n = 159) b | |

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE | 133 (83.6) [524] |

| TEAE rate per administration of study drug | 0.23 |

| TEAE rate per patient‐year | 2.84 |

| TEAEs leading to death | 0 |

| TEAEs leading to study discontinuation | 1 (1) c |

| TEAEs by severity | |

| Mild | 101 (62.7) [328] |

| Moderate | 81 (50.3) [184] |

| Severe | 9 (5.6) [13] |

| SAEs | 3 (2) d |

| AESI per protocol e | 0 |

| Common TEAEs in ≥5% of patients by Preferred Term | |

| COVID‐19 | 58 (36) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 27 (17) |

| Injection‐site reactions f | 19 (12) |

| Injection‐site erythema | 11 (7) |

| Pruritus | 4 (3) |

| Urticaria | 2 (1) |

| Bruising | 1 (1) |

| Hematoma | 1 (1) |

| Irritation | 1 (1) |

| Headache | 10 (6) |

| Influenza | 11 (7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 9 (6) |

Note: Data are the number of patients who experienced events presented as n (%), and number of events presented as [E].

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; AESI, adverse event of special interest; E, number of events; HAE‐C1INH, hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency or dysfunction; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

AEs were coded according to System Organ Class and Preferred Term using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (v25.1); percentages are based on patients in the overall population (N = 161) who received ≥1 dose, unless stated otherwise.

Primary endpoints were assessed based on the primary analysis safety set of patients with HAE‐C1INH (N = 159).

Injection‐site irritation related to garadacimab leading to study discontinuation.

Three SAEs assessed as not related to garadacimab were reported (COVID‐19, n = 2; abdominal HAE attack, n = 1).

Abnormal bleeding, thromboembolic events, severe hypersensitivity, and anaphylaxis.

TEAEs are categorized as injection‐site reactions based on medical review of all relevant Preferred Terms.

In the overall population (N = 161), the TEAE profile was consistent with results from the primary safety analysis set, with 135 patients (84%) experiencing ≥1 TEAE and a total of 526 TEAEs reported. Of these, 21 patients (13%) experienced a total of 52 TEAEs that were considered to be garadacimab related. No deaths were observed. One patient (1%) discontinued garadacimab due to a garadacimab‐related TEAE occurring after 4 months of treatment (injection‐site irritation in the abdomen of moderate severity, within 24 h after injection; recovered/resolved after 13 days). For most patients, the TEAEs were mild (63% of patients) or moderate (50% of patients); 6% of patients experienced severe TEAEs. Three patients (2%) experienced a total of three SAEs (COVID‐19 [two] and abdominal HAE attack [one]); none were deemed to be garadacimab related, and all recovered or resolved. There were no reports of AESIs per protocol (abnormal bleeding, thromboembolic events, severe hypersensitivity, or anaphylaxis).

The most common TEAEs were COVID‐19 (n = 58; 36%), nasopharyngitis (27; 17%), injection‐site reactions (ISRs; 19; 12%), influenza (11; 7%), headaches (10; 6%), and upper respiratory tract infections (9; 6%). Of the 19 patients with ISRs, there were 43 events, including injection‐site erythema, pruritus, urticaria, bruising, hematoma, and irritation; most were mild (41, 95%) and the remaining two were moderate in severity. ISRs were the most common garadacimab‐related TEAE (36/52 events, 69%).

3.3. Laboratory findings

Laboratory analyses in the overall population (N = 161) revealed increased levels of prothrombin fragment 1 + 2 in two patients (1%) (Table S6). Low‐titer anti‐garadacimab antibodies were detected in one patient at Day 1, one patient at Month 6, three patients at Month 12, and one patient at the end of treatment. Laboratory findings reported as TEAEs occurred in six patients (4%; total of 19 events), including positive bacterial tests in urine (n = 4; 3%) and red blood cells in urine (2; 1%). All TEAEs related to laboratory findings were mild (17/19; 89%) or moderate (2/19; 11%) in severity, and none were considered to be garadacimab related. There were no clinically relevant changes in mean prothrombin time or mean activated partial thromboplastin time throughout the OLE period, and no changes in these parameters were reported as TEAEs.

3.4. Secondary efficacy endpoints

At data cut‐off, the mean (95% CI) HAE attack rate reduction across the OLE treatment period versus run‐in was 95% (93–97) in the overall population (N = 161; mean [95% CI] attack rate of 0.16 [0.10–0.22] and 3.57 [3.20–3.95], respectively) (Table 3). Treatment effect was evident in the first 3 months and sustained throughout the long‐term treatment period, with a mean ≥94% reduction in attack rate versus run‐in observed in each 3‐month treatment window (Figure 1). Rollover patients (n = 92) experienced a mean (95% CI) attack rate of 0.12 (0.05–0.19) in the OLE, corresponding to a mean (95% CI) 96% (94–98) reduction from run‐in (mean [95% CI] attack rate 3.69 [3.22–4.16]). Newly enrolled patients (n = 69) experienced a mean (95% CI) attack rate of 0.21 (0.11–0.31) in the OLE versus 3.41 (2.79–4.04) during run‐in, corresponding to a mean (95% CI) 93% (90–96) reduction.

TABLE 3.

Secondary efficacy endpoints (overall population).

| Endpoint | Overall (N = 161) | Rollovers (n = 92) | Newly enrolled (n = 69) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garadacimab exposure, months | |||

| Median (IQR) | 13.8 (11.9–16.3) | 14.8 (11.2–17.7) | 13.5 (12.7–14.4) |

| Range | 3.0–21.1 | 4.9–20.9 | 3.0–21.1 |

| Mean (95% CI) number of HAE attacks per month | |||

| Run‐in period | 3.57 (3.20–3.95) | 3.69 (3.22–4.16) | 3.41 (2.79–4.04) |

| Treatment period | 0.16 (0.10–0.22) | 0.12 (0.05–0.19) | 0.21 (0.11–0.31) |

| First 31 days | 0.21 (0.10–0.31) | 0.07 (0.01–0.14) | 0.38 (0.16–0.61) |

| Months 1–3 | 0.21 (0.12–0.30) | 0.13 (0.04–0.21) | 0.32 (0.15–0.49) |

| Months 4–6 | 0.14 (0.08–0.21) | 0.09 (0.03–0.16) | 0.21 (0.09–0.33) |

| Months 7–9 | 0.15 (0.09–0.22) | 0.12 (0.05–0.19) | 0.20 (0.07–0.33) |

| Months 10–12 | 0.14 (0.07–0.21) | 0.12 (0.03–0.21) | 0.17 (0.05–0.28) |

| Months 13–15 | 0.13 (0.03–0.22) | 0.12 (−0.02–0.27) | 0.13 (0.01–0.25) |

| Mean percentage difference (95% CI) in number of HAE attacks per month vs. run‐in period | −95 (−97 to −93) | −96 (−98 to −94) | −93 (−96 to −90) |

| Median (IQR) number of HAE attacks per month | |||

| Run‐in period | 2.85 (1.90–4.35) | 3.04 (2.00–4.63) | 2.61 (1.79–4.06) |

| Treatment period | 0 (0–0.13) | 0 (0–0.09) | 0 (0–0.15) |

| Median percentage difference (IQR) in number of HAE attacks per month vs. run‐in period | −100 (−100 to −96) | −100 (−100 to −97) | −100 (−100 to −92) |

| Patients responding to treatment vs. run‐in period, n (%) | |||

| ≥50% reduction in the number of HAE attacks per month | 158 (98) | 90 (98) | 68 (99) |

| ≥70% reduction in the number of HAE attacks per month | 151 (94) | 88 (96) | 63 (91) |

| ≥90% reduction in the number of HAE attacks per month | 137 (85) | 84 (91) | 53 (77) |

| Attack‐free patients (100% reduction in HAE attack rate) | 96 (60) | 58 (63) | 38 (55) |

| Mean (95% CI) number of HAE attacks per month requiring ODT | |||

| Run‐in period | 2.98 (2.57–3.40) | 3.24 (2.73–2.74) | 2.64 (1.94–3.34) |

| Treatment period | 0.14 (0.09–0.20) | 0.11 (0.04–0.18) | 0.19 (0.09–0.28) |

| Mean (95% CI) number of moderate or severe HAE attacks per month | |||

| Run‐in period | 2.59 (2.26–2.92) | 2.63 (2.21–3.04) | 2.55 (2.01–3.09) |

| Treatment period | 0.11 (0.07–0.15) | 0.08 (0.03–0.13) | 0.15 (0.08–0.23) |

| Subject's Global Assessment of Response to Therapy at visit Month 12, n (%) | |||

| Good or excellent a | 110 (93.2) | 58 (95.1) | 52 (91.2) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HAE, hereditary angioedema; IQR, interquartile range; ODT, on‐demand treatment.

Rollovers (n = 61) and newly enrolled patients (n = 57).

FIGURE 1.

Mean HAE attack rate in the run‐in period and treatment period by 3‐month windows for the overall population, rollover patients, and newly enrolled patients. CI, confidence interval; HAE, hereditary angioedema; IQR, interquartile range.

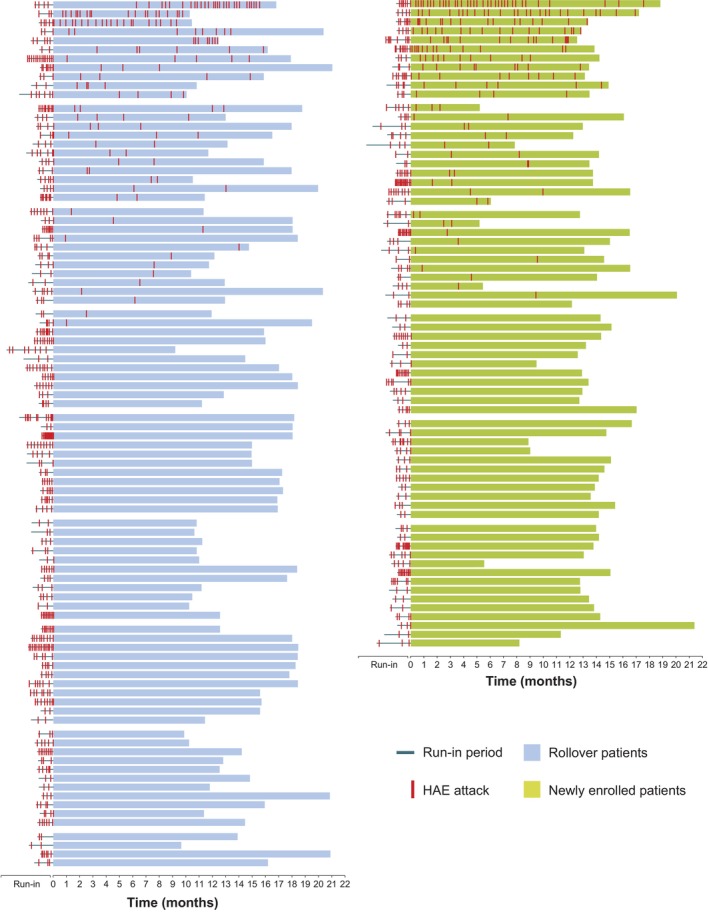

In the overall population (N = 161), 158 (98%) and 137 patients (85%) had ≥50% and ≥90% reductions in attack rate from run‐in, respectively, while 96 patients (60%) were attack‐free (100% reduction) up to data cut‐off (Figure 2A and Table 3). For rollover patients, 90 (98%), 84 (91%), and 58 (63%) had ≥50% reductions, ≥90% reductions, and were attack‐free, respectively. A post hoc analysis showed that 95% of patients in the rollover group treated with garadacimab (21/22) who were attack‐free during the 6‐month pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) study remained attack‐free in the OLE after a mean exposure of 14.0 months (range, 11.3–17.8). Among newly enrolled patients in the OLE, 68 (99%) and 53 (77%) had ≥50% and ≥90% reductions in attack rate from run‐in, respectively, and 38 (55%) were attack‐free. Consistent proportions of patients were attack‐free in 3‐month treatment windows throughout the OLE in the overall population, as well as in the rollover and newly enrolled groups (Figure 2A). Figure 3 shows the per‐patient profiles of HAE attacks over time during the run‐in and treatment periods.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of patients (A) with reductions of ≥50%, ≥90%, and 100% (attack‐free) in HAE attack rate in the treatment period compared with the run‐in period, and (B) who were attack‐free in the treatment period by 3‐month windows, for the overall population, rollover patients, and newly enrolled patients. HAE, hereditary angioedema.

FIGURE 3.

Timeline of HAE attacks during run‐in and treatment periods, per patient, grouped by rollover patients and newly enrolled patients. Each horizontal block represents the timeline of an individual patient. Within patient groupings, timelines are displayed in order, from patients with the highest number of HAE attacks during the treatment period to those with no attacks during treatment. HAE, hereditary angioedema.

The mean (95% CI) number of HAE attacks per month requiring ODT in the OLE was 0.14 (0.09–0.20) in the overall population, 0.11 (0.04–0.18) in rollover patients, and 0.19 (0.09–0.28) in newly enrolled patients (Table 3). Treatment with garadacimab reduced the mean (95% CI) number of moderate or severe attacks per month from 2.59 (2.26–2.92) during run‐in to 0.11 (0.07–0.15) during treatment in the overall population. For rollover and newly enrolled patients, the mean (95% CI) number of moderate or severe attacks per month decreased from 2.63 (2.21–3.04) to 0.08 (0.03–0.13) and from 2.55 (2.01–3.09) to 0.15 (0.08–0.23), respectively.

Among the patients who completed the SGART (N = 118), the majority (110; 93%) rated their response to garadacimab as “good” or “excellent” at Month 12; few patients (three; 3%) rated their response to treatment as “none” or “poor” (Figure S3). The majority of rollover patients (58/61; 95%) and newly enrolled patients (52/57; 91%) rated their response to garadacimab as “good” or “excellent,” with few in either group rating their response as “none” or “poor.” According to IGART findings (N = 119), investigators assessed the majority of their patients (117; 98%) as having a “good” or “excellent” response to garadacimab at Month 12 (Figure S3); no patients were assessed as having “none” or “poor” response.

4. DISCUSSION

In this interim analysis of the ongoing phase 3 (VANGUARD) OLE study, the primary and secondary safety endpoint findings support that garadacimab has a favorable safety profile suitable for long‐term use in HAE. The safety profile reported here is generally consistent with that observed in the pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) study. 15 Notably, there were no occurrences of AESIs per protocol, such as abnormal bleeding or thromboembolic events, in a sample size that had a 95% probability of detecting events with an event rate of >3%. There is no evidence from our study to indicate any plausible negative relationship between FXIIa inhibition by garadacimab and hemostasis, which is further corroborated by the lack of bleeding events in people with congenital FXII deficiency. 20 , 21 , 22

Although infections were frequently reported as TEAEs, none were considered to be related to garadacimab, and only two were serious (COVID‐19). Generally, clinical studies conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic reported an increased incidence of infections, such as respiratory infections and COVID‐19, which is consistent with the observations in our study. 11 , 15 , 23 , 24 , 25 Our findings demonstrate that continuous administration of garadacimab does not increase the severity of infections over time; notably, most cases were mild or moderate. The observed absence of effect on infection severity is supported by a study of patients with severe COVID‐19, which found that while garadacimab did not confer a clinical benefit, it did not result in an increased incidence of tracheal intubation or death and was not associated with thromboembolic or abnormal bleeding events. 26

In this study, garadacimab demonstrated substantial reductions in mean attack rate and durable efficacy, providing sustained protection from HAE attacks in a large population (N = 161) over a median exposure of 13.8 months. Garadacimab reduced the mean attack rate by 95% versus run‐in, with most patients (60%) remaining attack‐free until data cut‐off. This outcome is consistent with the pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) study in which patients receiving garadacimab (n = 39) experienced a 91% reduction in mean attack rate from baseline, and 62% of patients were attack‐free throughout the 6‐month treatment period, supporting the treatment effect observed in our larger cohort. 15 Furthermore, the substantial reduction (93%) in attack rate observed in newly enrolled patients is also consistent with that previously observed, providing further evidence for garadacimab as a suitable option for long‐term prevention of HAE attacks. Our results show that the sustained protection from attacks was substantiated by high treatment satisfaction; 93% and 98% of patients and investigators, respectively, rated the response to garadacimab as “good” or “excellent” at Month 12.

The durable efficacy of garadacimab, high proportion of patients who were attack‐free, high patient satisfaction, and convenience of once‐monthly fixed dosing via SC self‐administration point to garadacimab being a strong candidate for helping patients achieve the goal of complete disease control, per WAO/EAACI guidelines. 4 Garadacimab has the potential to improve patient compliance over other LTP treatments requiring more frequent dosing or intravenous administration. 13 Furthermore, the novel mechanism of action of garadacimab acts through the inhibition of FXIIa at the most upstream therapeutic target of the contact activation pathway of inflammation, therefore differing from approved LTP treatments that act as C1INH replacements or target kallikrein. 14 , 15 Although there are no head‐to‐head comparative studies between LTP treatments, the pivotal phase 3 study of berotralstat showed no difference to placebo in attack‐free rates, and the pivotal phase 3 study of lanadelumab demonstrated moderate attack‐free rates (31% and 44% for 300 mg every 4 weeks and 300 mg every 2 weeks, respectively), indicating a need for new treatment options with enhanced efficacy. 12 , 13 , 27 Patients receiving garadacimab demonstrated a 62% attack‐free rate in the pivotal phase 3 study, providing an opportunity to optimize current HAE treatment. 15

A potential limitation of this study was that the open‐label design may have influenced patient‐reported outcomes, such as SGART. In the pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) study, 82% of patients reported response to treatment as “good” or “excellent” after 6 months versus 93% of patients at Month 12 in this OLE. 15 It is possible that patients in an open‐label study may become biased, knowing that they are receiving active treatment. However, since other efficacy endpoints were similar between the pivotal phase 3 (VANGUARD) study and the OLE, we believe that the increase in “good” or “excellent” ratings per SGART is likely a reflection of the patients' satisfaction with the durable efficacy of garadacimab in preventing attacks.

Another potential limitation relates to how patients were grouped in the OLE. Based on the prespecified analysis, rollover patients who previously received placebo were grouped with rollover patients who previously received garadacimab. Grouping placebo rollover patients with newly enrolled patients may be pertinent to compare the effect of prior garadacimab treatment with newly initiated garadacimab, and a post hoc analysis of the OLE is planned to assess the impact of such grouping.

This study is also limited by inadequate racial and ethnic representation; the majority of the patients were White, which is similar to that reported in other HAE clinical trials. 12 , 27

The data presented here are from an interim analysis of the ongoing OLE study, and further data are being gathered to fully evaluate the long‐term safety and efficacy of garadacimab as LTP for HAE.

In conclusion, our interim analysis indicates that garadacimab has a favorable safety profile suitable for long‐term use and provides durable protection against HAE attacks, findings that are generally consistent with safety and efficacy data from previous studies. Garadacimab has the potential to bring patients closer to achieving the HAE treatment goals of complete disease control and normalization of patients' lives.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J‐P. Lawo, L. Wieman, A. Reshef and T.J. Craig contributed to the study design. T.J. Craig contributed to devising the study concept. All authors contributed to data acquisition. J‐P. Lawo contributed to the data analysis. J‐P. Lawo, H. Shetty, M. Pollen, L. Wieman, A. Reshef, and T.J. Craig contributed to data interpretation. All authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors provided intellectual input.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was sponsored by CSL Behring. The funder contributed to the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A. Reshef received research grants as a principal investigator, speaker, and advisor for BioCryst, CSL Behring, Ionis, Pharming, Pharvaris, Shulov Innovative Science, and Takeda/Shire. C. Hsu is a CSL Behring advisory board member and has received honoraria. C.H. Katelaris has conducted research with and has acted as an advisory board member for BioCryst, CSL Behring, Genzyme, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Takeda; and served on the scientific committee for HAE International educational meetings and the Budapest C1 inhibitor deficiency workshop. P.H. Li has received financial support from CSL Behring for acting as a study center investigator during the conduct of the study. He has acted as an advisory board member for CSL Behring, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Pharvaris, and Takeda. M. Magerl has received financial support from CSL Behring for acting as a study center investigator during the conduct of the study and personal fees from BioCryst, CSL Behring, Intellia, Ionis, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Octapharma, Pharming Technologies, Pharvaris, and Takeda/Shire outside the submitted work. K. Yamagami has received financial support from CSL Behring for acting as a study center investigator during the conduct of the study and honoraria for educational purposes from CSL Behring, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novartis, and Takeda. M. Guilarte has received honoraria for educational purposes from BioCryst, CSL Behring, Novartis, Pharming, and Takeda; participated in advisory boards organized by BioCryst, CSL Behring, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pharvaris, and Takeda; and has received funding to attend conferences and educational events from CSL Behring, Novartis, Pharming, and Takeda. She is a clinical trial/registry investigator for BioCryst, CSL Behring, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pharming, Pharvaris, and Takeda; and is a researcher at the Vall d'Hebron Research Institute program for promoting research activities. P.K. Keith has been a speaker, advisory board member, or consultant for and has received honoraria from ALK, AstraZeneca, Bausch, BioCryst, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Canadian Pharmacists Association, CSL Behring, GSK, Medexus, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda/Shire, and Valeo; has received research grants from CSL Behring and Takeda/Shire; serves as a medical advisor (volunteer) for Hereditary Angioedema Canada, a patient organization; serves as a board member (volunteer) for the Canadian Hereditary Angioedema Network, a physician organization; and is an employee of McMaster University. J.A. Bernstein is a consultant and principal investigator for BioCryst, BioMarin, CSL Behring, Intellia, Ionis, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Pharming, and Takeda/Shire; and is a consultant for Astria, Cycle Pharmaceuticals, and ONO Pharmaceutical. J‐P. Lawo is a full‐time employee of CSL Behring Innovation GmbH and shareholder of CSL Limited. H. Shetty is a full‐time employee of CSL Behring LLC and shareholder of CSL Limited. M. Pollen is a full‐time employee of CSL Behring LLC and shareholder of CSL Limited. L. Wieman is a full‐time employee of CSL Behring LLC and shareholder of CSL Limited. T.J. Craig is a speaker for CSL Behring, Grifols, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda; has received research and consultancy grants from BioCryst, BioMarin, CSL Behring, Grifols, Ionis, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Pharvaris, Astria, and Takeda; and is on the Medical Advisory Board for the US Hereditary Angioedema Association, Director of ACARE Angioedema Center at Penn State University, Hershey, PA, USA.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study investigators, study site coordinators, patients who participated in this study, and their families who supported them; the independent data monitoring committee members Bruce Zuraw (Chairperson), Konrad Bork, and Danny Cohn for their oversight; and Iris Jacobs, Henrike Feuersenger, Ingo Pragst, Andre Drysch, and Maria Proupin‐Perez of CSL Behring for designing and coordinating the trial and providing invaluable assistance in reviewing the manuscript. Medical writing support was provided by Suzanne Berresford, BPharm, of Helix, OPEN Health Communications (London, UK), and was funded by CSL Behring, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp‐2022).

Reshef A, Hsu C, Katelaris CH, et al. Long‐term safety and efficacy of garadacimab for preventing hereditary angioedema attacks: Phase 3 open‐label extension study. Allergy. 2025;80:545‐556. doi: 10.1111/all.16351

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04739059.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

CSL Behring will consider requests to share individual patient data (IPD) from CSL Behring‐sponsored studies with external, bona fide, qualified scientific and medical researchers on a case‐by‐case basis. When appropriate, IPD will generally be shared once review by major regulatory authorities (e.g., US Food and Drug Administration or European Medicines Agency) is complete and the primary publication is available. Proposed research should seek to answer a previously unanswered important medical or scientific question. Requests should reflect those important questions. Applicable country‐specific privacy and other laws and regulations will be considered and might prevent sharing of IPD. A research proposal detailing the use of the IPD will be reviewed by an internal CSL Behring review committee. If the request is approved, and the researcher agrees to the applicable terms and conditions in a data‐sharing agreement, IPD that has been appropriately anonymized will be made available. Supporting documents, including the study protocol and statistical analysis plan, will also be provided to the researcher. For information on the process and requirements for submitting a voluntary data‐sharing request for IPD, please contact CSL Behring at clinicaltrials@cslbehring.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zanichelli A, Arcoleo F, Barca MP, et al. A nationwide survey of hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency in Italy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aygören‐Pürsün E, Magerl M, Maetzel A, Maurer M. Epidemiology of bradykinin‐mediated angioedema: a systematic investigation of epidemiological studies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lumry WR, Settipane RA. Hereditary angioedema: epidemiology and burden of disease. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2020;41(Suppl 1):S8‐S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maurer M, Magerl M, Betschel S, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema‐the 2021 revision and update. Allergy. 2022;77(7):1961‐1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bygum A. Hereditary angio‐oedema in Denmark: a nationwide survey. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(5):1153‐1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agostoni A, Cicardi M. Hereditary and acquired C1‐inhibitor deficiency: biological and clinical characteristics in 235 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1992;71(4):206‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Busse PJ, Christiansen SC, Riedl MA, et al. US HAEA medical advisory board 2020 guidelines for the management of hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(1):132‐150.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Banerji A. The burden of illness in patients with hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(5):329‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aygören‐Pürsün E, Bygum A, Beusterien K, et al. Estimation of EuroQol 5‐dimensions health status utility values in hereditary angioedema. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1699‐1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banerji A, Davis KH, Brown TM, et al. Patient‐reported burden of hereditary angioedema: findings from a patient survey in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(6):600‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wedner HJ, Aygören‐Pürsün E, Bernstein J, et al. Randomized trial of the efficacy and safety of berotralstat (BCX7353) as an oral prophylactic therapy for hereditary angioedema: results of APeX‐2 through 48 weeks (part 2). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2305‐2314.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banerji A, Riedl MA, Bernstein JA, et al. Effect of lanadelumab compared with placebo on prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2108‐2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beard N, Frese M, Smertina E, Mere P, Katelaris C, Mills K. Interventions for the long‐term prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;11(11):CD013403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zanichelli A, Montinaro V, Triggiani M, Arcoleo F, Visigalli D, Cancian M. Emerging drugs for the treatment of hereditary angioedema due to C1‐inhibitor deficiency. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2022;27(2):103‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Craig TJ, Reshef A, Li HH, et al. Efficacy and safety of garadacimab, a factor XIIa inhibitor for hereditary angioedema prevention (VANGUARD): a global, multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10382):1079‐1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Craig T, Magerl M, Levy DS, et al. Prophylactic use of an anti‐activated factor XII monoclonal antibody, garadacimab, for patients with C1‐esterase inhibitor‐deficient hereditary angioedema: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):945‐955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valerieva A, Longhurst HJ. Treatment of hereditary angioedema‐single or multiple pathways to the rescue. Front Allergy. 2022;3:952233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Long‐term safety and efficacy of CSL312 (garadacimab) in the prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema attacks. 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04739059

- 19. US Food and Drug Administration . E1A the extent of population exposure to assess clinical safety: for drugs intended for long‐term treatment of non‐life‐threatening conditions. 1995. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory‐information/search‐fda‐guidance‐documents/e1a‐extent‐population‐exposure‐assess‐clinical‐safety‐drugs‐intended‐long‐term‐treatment‐non‐life

- 20. Fernandes HD, Newton S, Rodrigues JM. Factor XII deficiency mimicking bleeding diathesis: a unique presentation and diagnostic pitfall. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Renne T, Schmaier AH, Nickel KF, Blomback M, Maas C. In vivo roles of factor XII. Blood. 2012;120(22):4296‐4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lammle B, Wuillemin WA, Huber I, et al. Thromboembolism and bleeding tendency in congenital factor XII deficiency–a study on 74 subjects from 14 Swiss families. Thromb Haemost. 1991;65(2):117‐121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farkas H, Stobiecki M, Peter J, et al. Long‐term safety and effectiveness of berotralstat for hereditary angioedema: the open‐label APeX‐S study. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021;11(4):e12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalunian KC, Furie R, Morand EF, et al. A randomized, placebo‐controlled phase III extension trial of the long‐term safety and tolerability of anifrolumab in active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75(2):253‐265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu M, Zhu X, Wu J, et al. PCSK9 inhibitor recaticimab for hypercholesterolemia on stable statin dose: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 1b/2 study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Papi A, Stapleton RD, Shore PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of garadacimab in combination with standard of care treatment in patients with severe COVID‐19. Lung. 2023;201(2):159‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zuraw B, Lumry WR, Johnston DT, et al. Oral once‐daily berotralstat for the prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(1):164‐172.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

CSL Behring will consider requests to share individual patient data (IPD) from CSL Behring‐sponsored studies with external, bona fide, qualified scientific and medical researchers on a case‐by‐case basis. When appropriate, IPD will generally be shared once review by major regulatory authorities (e.g., US Food and Drug Administration or European Medicines Agency) is complete and the primary publication is available. Proposed research should seek to answer a previously unanswered important medical or scientific question. Requests should reflect those important questions. Applicable country‐specific privacy and other laws and regulations will be considered and might prevent sharing of IPD. A research proposal detailing the use of the IPD will be reviewed by an internal CSL Behring review committee. If the request is approved, and the researcher agrees to the applicable terms and conditions in a data‐sharing agreement, IPD that has been appropriately anonymized will be made available. Supporting documents, including the study protocol and statistical analysis plan, will also be provided to the researcher. For information on the process and requirements for submitting a voluntary data‐sharing request for IPD, please contact CSL Behring at clinicaltrials@cslbehring.com.