Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the synergistic effect of glycolysis inhibition on therapy answer to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal carcinoma.

Methods

Primary cell cultures from 33 renal tumors including clear cell RCC (ccRCC), papillary RCC and the rare subtype chromophobe RCC as well as two metastases of ccRCC were obtained and cultivated. The patient-derived cells were verified by immunohistochemistry. CcRCC cells were further examined by exon sequencing of the von Hippel–Lindau gene (VHL) and by RNA-sequencing. Next, cell cultures of all subtypes of RCC were exposed to increasing doses of various tyrosine kinase inhibitors (axitinib, cabozantinib and pazopanib) and the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-d-glucose, alone or combined. CellTiter-Glo® Luminescence assay and Crystal Violet staining were used to assess the inhibition of glycolysis and the viability of the cultured primary cells.

Results

The cells expressed characteristic tissue markers and, in case of ccRCC cultures, the VHL status of the tumor they derived from. An upregulation of HK1, PFKP and SLC2A1 was observed, while components of the respiratory chain were downregulated, confirming a metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis. The tumors displayed variable individual responses for the therapeutics. All subtypes of RCC were susceptible to cabozantinib treatment indicated by decreased proliferation. Adding 2-deoxy-d-glucose to tyrosine kinase inhibitors decreased ATP production and increased the susceptibility of ccRCC to pazopanib treatment.

Conclusion

This study presents a valuable tool to cultivate even uncommon and rare renal cancer subtypes and allows testing of targeted therapies as a personalized approach as well as testing new therapies such as glycolysis inhibition in an in vitro model.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00432-020-03278-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Renal cancer, Clear cell renal cell carcinoma, Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, Deoxyglucose, Papillary renal cell carcinoma, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) combines a heterogeneous group of malignant neoplasia responsible for 5% of all cancers in men and 3% in women (Capitanio et al. 2019). Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most common subtype with 70–75% of all RCC, followed by papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC) with 15% and chromophobe RCC (chRCC) with 5% (Shuch et al. 2015). Apart from surgery, possible therapy options are extremely limited due to high resistance of RCC against conventional chemotherapy and radiation (Buti et al. 2013). The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, ipilimumab and pembrolizumab is the established first-line therapy (Angulo and Shapiro 2019; Albiges et al. 2019). First reports reveal a response rate in only 42% of patients with a median progression-free survival of 11.6 months (Motzer et al. 2018). In case of disease progression or intolerance to immune checkpoint inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) such as cabozantinib, axitinib, sunitinib or pazopanib remain a second-line option. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors prolonged the overall survival 48 months in a low-risk group of patients with advanced RCC. However, only 30–40% of the patients responded to TKI such as sunitinib or pazopanib (Ljungberg et al. 2014; Motzer et al. 2007; Sternberg et al. 1990). Unfortunately, it has not been elaborated which sequences of immunotherapeutic agents and TKI are the most effective treatment for metastatic ccRCC. Even less data exist regarding the optimal therapy of advanced non-clear renal cell carcinomas since most of the published studies focused on ccRCC (Fernández-Pello et al. 2017; Keizman et al. 2016).

Testing TKI in patient-individualized cell cultures are a step towards personalized treatment of metastatic renal cancer. Moreover, this in vitro model might allow the development of new therapeutic approaches. Therefore, we exposed primary cell cultures of various RCC entities to the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) alone and in combination with TKI. Especially, ccRCC depends on aerobic glycolysis even under normoxic conditions, which is referred to as Warburg effect (Akhtar et al. 2018; Linehan and Ricketts 2013). Early studies revealed that the inhibition of glycolysis leads to cell death in ccRCC (Chan et al. 2011). The efficiency of several inhibitors and small molecules targeting the glutamine metabolism and glycolysis is assessed in current clinical trials (Akins et al. 2018). In this study, we present a fast and reliable protocol for cultivating several subtypes of RCC and assess their susceptibility to TKI in combination with 2-DG, targeting glycolysis as a metabolic key feature.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The acquisition of patient material and experiments was performed with the patient’s consent and the approval of the ethics committee of Bonn University Hospital (EK 219/17). All materials, if not stated otherwise, were acquired by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, USA).

Figure 1 summarizes and demonstrates the generation and processing of RCC primary cell cultures.

Fig. 1.

Generation of primary cell cultures of RCC specimens. After surgical resection, the tumor tissue of clear cell RCC, papillary RCC and chromophobe RCC was minced, digested, filtered and cultivated. The cell cultures were validated using immunohistochemical staining for characteristic tissue- and tumor markers. For ccRCC specimens and their corresponding cultures, the VHL gene was sequenced, matching the VHL status of the cell cultures with the tissue they derived from. RNA was extracted from tumor and benign tissue for RNA-sequencing to identify central gene expression characteristics and alterations. All RCC subtypes were treated in vitro with tyrosine kinase inhibitors −/+2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG), using a CellTiter-Glo® Luminescence assay and a crystal violet assay to assess the decrease of glycolysis and the cell viability after treatment; ccRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma, VHLvon Hippel–Lindau gene

Generation of primary cell cultures

Fresh tumor and non-neoplastic material from 32 patients who underwent partial or complete nephrectomy for ccRCC, pRCC and chRCC as well as two cases of adrenal metastasis (ccRCC) and one oncocytoma were included (histopathological parameters in Table 1). A piece of tissue, approximately 2 cm3, was obtained from the tumor mass. Necrotic, fibrotic and capsular regions were avoided. Visible blood vessel remnants were removed. The tissue was minced and transferred in 10-mL digestion solution (RPMI 1640) pre-warmed to 37 °C, containing 200-U/mL collagenase type II, 100-U/mL hyaluronidase type V (Sigma Aldrich, USA) and 2% penicillin/streptomycin. The tissue was incubated in a water bath (37 °C) under constant shaking (150 rpm). After 2 h of digestion, the cell solution was filtered using sterile 70-µm and 40-µm sieves (VWR International, Germany). The cells were washed with DPBS and centrifuged (1000 rpm, 5 min); the supernatant was carefully discarded. Cells were then seeded at a density of approximately 10,000 cells/cm3. The serum-reduced cell culture medium (SRM) contained supplements as follows: DMEM/F12 medium + 5% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10 ng/mL hrEGF (R&D Systems, USA), 10 ng/mL FGF-basic (PeproTech, Germany), 1 × B27-supplement, 1 × Lipid Mixture 1 (Sigma Aldrich), 1-mM N-Acetyl-Cysteine, 4-mM l-Glutamine, 1 × Non-essential amino acids and 10-mM HEPES (GE Healthcare, UK). The cell cultures were tested for mycoplasma contamination every two weeks and were free of any contamination.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological parameters of the included patient specimens

| N | [%] | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 23 | 65.71 |

| Female | 12 | 34.29 |

| Total | 35 | |

| Median age at surgery (years) | 66 | Range 47–87 |

| Histology⃰ | ||

| ccRCC | 22 | 62.85 |

| pRCC | 6 | 17.14 |

| chRCC | 4 | 11.34 |

| Oncocytoma | 1 | 2.86 |

| Metastases (ccRCC) | 2 | 5.71 |

| Total | 35 | |

| pT stage** | ||

| pT1 | 16 | 50.0 |

| pT2 | 1 | 3.12 |

| pT3 | 15 | 46.87 |

| Total | 32 | |

| Grade*** | ||

| 1 | 2 | 7.14 |

| 2 | 13 | 46.43 |

| 3 | 11 | 39.29 |

| 4 | 2 | 7.14 |

| Total | 28 | |

*The histology was assessed according to the 2016 WHO Classification of tumors of the urinary system

**The TNM status was assessed to the WHO/UICC Classification system and the tumor grade according to the WHO/ISUP Classification. The TNM classification was not used for oncocytoma and the metastases of ccRCC

***The tumor grade was not assessed for chRCC, the metastases of ccRCC and the oncocytoma

CcRCC17: a patient pre-treated with nivolumab and sunitinib

One patient had a primary metastatic ccRCC (pulmonary and bone) and received neo-adjuvant treatment with nivolumab and sunitinib before nephrectomy. Radiological follow-up revealed a mixed response three months after neo-adjuvant therapy. The cells were cultivated and treated like the other ccRCC specimens.

Immunohistochemical validation

For IHC staining of primary cell cultures, the cells were detached with trypsin–EDTA and washed in DPBS, the cell pellet was resuspended in 300-µL Richard-Allan Scientific HistoGel according to the manufacturer’s instructions, fixed in 400-μL PFA (4%) and embedded in paraffin. IHC staining was performed using antibodies as follows (dilution in spaces; distributors in supplementary materials): PAX8 (1:100), vimentin (VIM, 1:5000), CD10 (pre-diluted), CA9 (1:8000), CK7 (1:500), AMACR (1:100), CD117 (c-kit, 1:200). IHC staining was performed on a Ventana Benchmark system for CD10, AMACR and CD117 and on a Medac 480S system for PAX8, VIM, CA9 and CK7. IHC staining was performed using established staining protocols of the routine laboratory. Immunohistochemical staining was assessed using a Leica DM 500 microscope (Leica, Germany). GIMP software v.2.10.12 was used to optimize the IHC pictures (brightness and clearness, if necessary) without altering the IHC staining characteristics or intensity.

Sequencing of the VHL gene

Genomic DNA was extracted for VHL exon sequencing using the QIAmp DNA Minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. VHL exons (1, 2a, 2b, 3) were amplified using a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (primer sequences: supplementary data). Fragment sizes were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey–Nagel, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sanger sequencing for the VHL gene sequences was performed by GATC sequencing service (Eurofins Genomics, Germany). Sequencing trace files were analyzed using ApE Plasmid Editor (Jorgensen Laboratory, USA) and FinchTV (Geospiza Inc., USA) to identify VHL alterations. The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used as a reference database to check for known VHL mutations (Tate et al. 2019).

RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq)

RNA from eight ccRCC and corresponding benign tissue was extracted. Raw single-read sequencing results were mapped to the human genome (GRCh38) with hisat2-2.1.0 (Kim et al. 2015). The mapped reads were processed using samtools (Li et al. 2009) and featureCounts (Liao et al. 2014) to quantify reads. Read counts were statistically analyzed with the Bioconductor software package DESeq2 (Love et al. 2014). Differentially expressed genes were calculated for each of the groups by applying multiple testing corrections including Bonferroni correction method and FDR. A p value cut-off of 0.05 was accepted as significant. The PCA plot was generated using ggplot2 (Wickham 2016). The differentially expressed genes were called into the database Enrichr (https://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/) using a fold change of log2 (1.0) for upregulated genes and of log2 (− 1.0) for downregulation.

Generation of a CellTiter-Glo®-Luminescent viability assay and -analysis

The primary cells of eight ccRCC cultures, four chRCC cultures and two pRCC cultures were seeded in a 96-well plate (Sarstedt, Germany) with a density of 1000 cells/well in SRM (100μL/well). After 24 h, cells were treated with different concentrations of axitinib (AXT; 2.5 μM, 5.0 μM, 10.0 μM, 20.0 μM), cabozantinib (CZB; 4.5 μM, 9 μM, 18 μM, 36 μM) and pazopanib (PZP; 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, 80 μM). Additionally, cells were treated with AXT, CZB and PZP as described above in combination with 50-μM D-deoxy-d-glucose (DDG) to assess the effect of additional glycolysis inhibition. After 72 h, the wells were provided with 100-μL CellTiter-Glo®-Luminescent reagent (Promega, USA) and incubated for 6 min to stabilize the signal. The cells were transferred to a nontransparent 96-well plate (Greiner bio-one, Austria) and luminescence was assessed on a Centro LB 960 microplate luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Germany). The viability data were referred to an untreated control and analyzed and visualized with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, USA) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Crystal violet assay

Since 2-DG blocks ATP production by inhibition of glycolysis and CellTiter-Glo is an ATP-based assay, we verified our results with the Crystal Violet assay. The therapy response assays were repeated with primary cells of four new cultivated ccRCC and one previous examined chRCC and pRCC, respectively. After 72 h, the medium was carefully removed, washed with PBS and fixed for 10 min with 4% PFA. 4%PFA was removed and the cells were incubated with 0.5% Crystal Violet solution for 10 min at room temperature. After that, the 96-well plates were washed two times with ddH2O. To solubilize the stain 1% SDS was added. The absorbance of each well was read at 570 nm. The viability data were normalized to the untreated control and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The data obtained for the CellTiter-Glo assay were compared with the data obtained from the Crystal Violet assay.

Results

Successful cultivation of several RCC entities including ccRCC, pRCC and chRCC

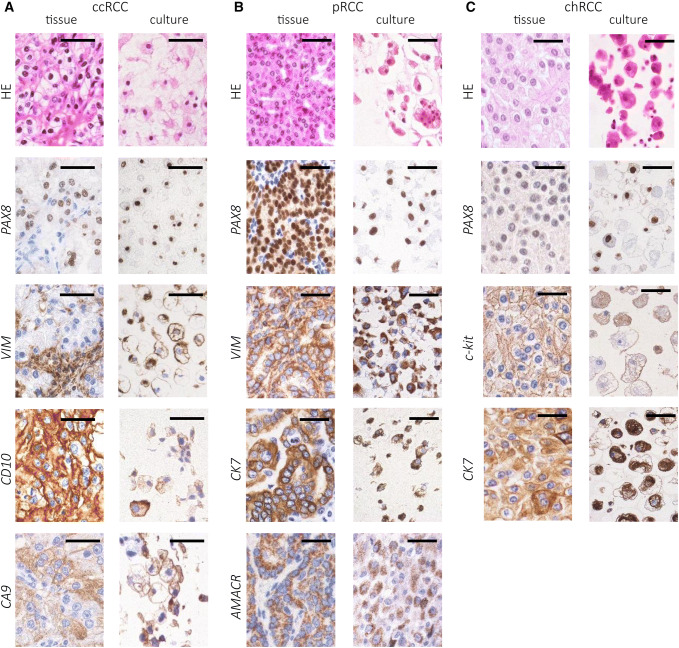

86.4% of ccRCC specimens (19/22), 100% of pRCC samples (6/6), 100% of chRCC specimens (4/4), one oncocytoma and 29 cases of normal renal tissue (100%) were successfully cultivated. Whereas RCC cell cultures were successfully passaged four–five times until growth arrest occurred (minimum two, maximum 14 times), benign cell cultures easily reached up to ten confluences. Histological characterization and IHC staining revealed a high similarity to the tissue of origin (Fig. 2). Three ccRCC cultures (13.6%) and the two cultures of ccRCC metastases were positive for vimentin but devoid of other characteristic markers of ccRCC, indicating fibroblast overgrowth. The oncocytoma displayed a growth in epithelial cell nests, similar to chRCC cell cultures, and expressed PAX8 and c-kit but was negative for CK7, matching the tissue of origin (data not shown). Benign primary cell cultures grew in a typical cobblestone-like pattern and expressed PAX8 as a marker of renal epithelial origin in all cases (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

IHC staining of RCC tissue and derived primary cell cultures. The cells were detached, embedded in paraffin and stained for tissue- and tumor markers. a ccRCC expressed PAX8, vimentin (VIM), CD10 and CA9. b pRCC tissue and cell cultures expressed PAX8, VIM, CK7 and AMACR. c chRCC expressed PAX8, CK7 and c-kit (CD117); HE = hematoxylin–eosin; bar = 100 µm; The staining was assessed using a Leica DM500 microscope; ccRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma, pRCC papillary renal cell carcinoma, chRCC chromophobe renal cell carcinoma

In four of the seven ccRCC specimens (57.1%), mutations in one of the three VHL exons were observed. While three of them were heterozygous, one was homozygous (Table 2). The three other samples (ccRCC1, ccRCC6 and ccRCC8) were VHL wild type. Among the discovered mutations, a new frameshift deletion in exon 2a and an in-frame deletion in exon 1 were detected. In all cases, the VHL status of the tissue of origin matched the correspondent cell culture.

Table 2.

Sequencing of VHL gene exons in ccRCC specimens

| ID | Exon | VHL status (DNA) | VHL status (amino acids) | Mutation type | COSMIC-ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ccRCC2 | 1 | c.332G>T/+ | VHLp.S111I/+ | Missense substitution | COSM36341 |

| ccRCC3 | 2a | c.420_439del20/+ | p.N141fs25/+ | Frameshift deletion | – |

| ccRCC5 | 1 | c.223_225delCAT/+ | VHLp.I75del/+ | In frame deletion | – |

| ccRCC10 | 3 | c.491 A>T | p.Q164L | Missense substitution | COSM30288 |

In four of the seven tested ccRCC primary cell cultures, mutations in the DNA exons coding for pVHL were detected. Three had a heterozygote mutation status (/+), one sample (ccRCC10) had a homozygote mutation leading to missense substitution. Two of these mutations have been reported before in the COSMIC database (COSMIC-ID)

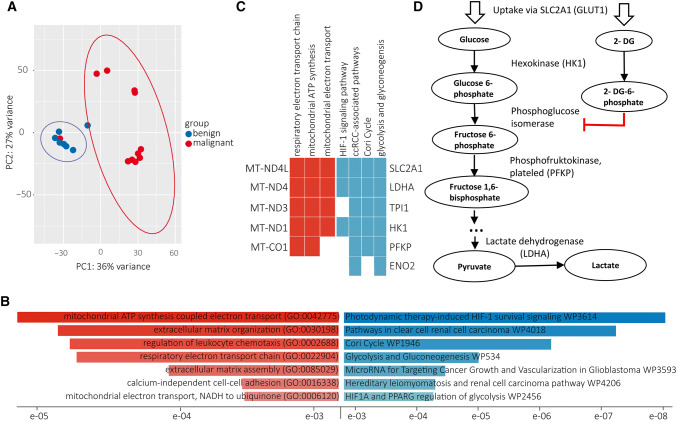

RNA-sequencing reveals a metabolic shift in ccRCC specimens

Seven ccRCC specimens were analyzed with RNA-Seq using benign tissue as a reference. The ccRCC specimens displayed a significant downregulation (FDR < 0.05) of several genes encoding respiratory chain components and mitochondrial electron transporters as well as pathways involved in extracellular matrix organization, referring to the GO database 2018 for Biological Processes (Fig. 3b). Genes involved in glycolysis were significantly upregulated, including hexokinase 1 (HK1), phosphofructokinase, platelet (PFKP) as well as the glucose transporter SLC2A1 (GLUT1) according to KEGG 2019 Human database (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 3.

RNA-sequencing and alternated pathways in ccRCC samples. Seven ccRCC specimens were analyzed using the benign tissue as reference. a Within the distinct populations of malignant and benign tissue, a close genetic relationship was observed. b The biological processes (Gene Ontology) of mitochondrial ATP synthesis and respiratory electron transport chain were significantly downregulated in ccRCC tumors; whereas, the pathways (KEGG 2019 Human) of HIF-1 signaling, Cori cycle, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis were upregulated. c The genes MT-ND4L, MT-ND4, MT-ND3, MT-ND1 and MT-CO1 were downregulated in ccRCC tissue. The expression of several genes involved in HIF-1 signaling and glycolysis were upregulated. d Glycolysis and their inhibition by 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG, simplified): After uptake via SLC2A1, glucose and 2-DG are phosphorylated to glucose 6-phosphate or 2-DG 6-phosphate, respectively. 2-DG-6-phosphate is a competitive inhibitor of the phosphoglucose isomerase, thus inhibiting further glycolysis; a full list of all genes significantly alternated is provided in the supplementary data. Several corrections were used to identify significance, including FDR and Bonferroni corrections with a p value ≤ 0.05 being significant

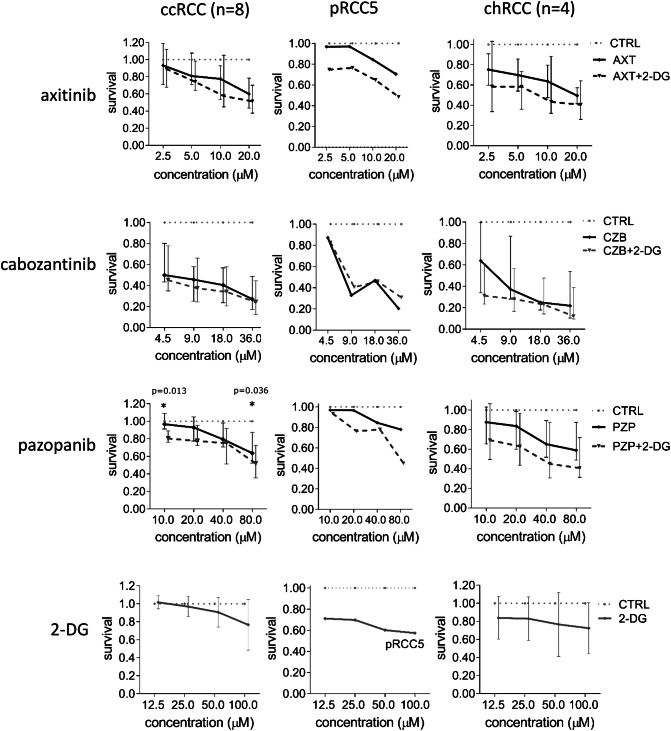

2-DG sensitizes RCC primary cells to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors

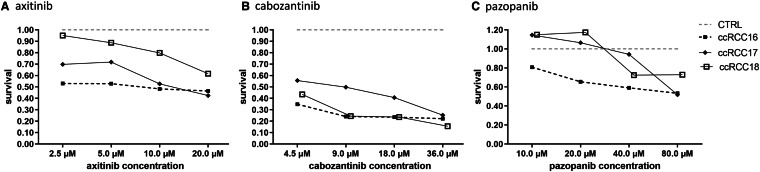

The cell cultures were exposed to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) axitinib (AXT), cabozantinib (CZB) and pazopanib (PZP) at increasing doses. To assess the viability of the cells, the ATP-based CellTiter-Glo assay was used. Only at a concentration of 80 µM, ccRCC and pRCC5 responded to AXT in vitro. Cell cultures of chRCC were susceptible to AXT alone (Fig. 4). CBZ was effective against all RCC subtypes, reducing the viability up to 80% at higher levels (Fig. 4). In case of PZP, cell cultures of ccRCC and chRCC responded especially to higher doses (40 µM and 80 µM). Compared to the untreated control, all cell lines of ccRCC responded to the different TKI with varying decreased cell viability depending on the concentration. Interestingly, the different cell lines of ccRCC, pRCC and chRCC as well as the single cases of each histological subtype displayed a highly variable response to the treatment with TKI (Fig. 5). The tumor line ccRCC17, a primary metastatic ccRCC pre-treated with sunitinib and nivolumab, responded well to AXT and CBZ.

Fig. 4.

Treatment of RCC cell cultures with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and 2-DG. The primary cell cultures of eight ccRCC, two pRCC (here pRCC5 as example) and four chRCC were treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in combination with 2-DG (details see “Materials and methods”). The cell lines of ccRCC responded with a significant decrease of viability in the CellTiter-Glo assay. Additionally, the cells were treated with 2-DG alone. For ccRCC and chRCC, the median with the interquartile range is displayed. CcRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma, pRCC papillary renal cell carcinoma, chRCC chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; CTRL untreated control, AXT axitinib, CBZ cabozantinib, PZP pazopanib, 2-DG 2-deoxy-d-glucose

Fig. 5.

Individual response of three exemplary ccRCC lines to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The cell lines of all tumor entities displayed different responses to the treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the CellTiter-Glo assay. CcRCC17 belonged to a patient who was diagnosed with primary metastatic disease and underwent neo-adjuvant treatment with sunitinib and nivolumab before nephrectomy, showing in vitro therapy response especially to axitinib and cabozantinib; ccRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma

When added to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), 2-DG further reduced the cell viability of pRCC5 cells under treatment with AXT and PZP by additional 20% (Fig. 4). Cell cultures of chRCC responded to all TKI with an additional viability reduction by 10–20%, when 2-DG was added (Fig. 4). In case of PZP, cell cultures of ccRCC displayed a dramatic decrease of cell viability when adding 2-DG to pazopanib at doses of 10 µM and 80 µM, respectively. A sensitizing effect of 2-DG to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors was not observed for ccRCC17 (data not shown).

The isolated treatment with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) proved to be slightly effective against pRCC5 and chRCC. The cell viability was reduced by 20% in chRCC cultures and by 30–40% in pRCC5 (Fig. 4).

To assess, whether or not the reduced luminescence and, hence, ATP levels in vitro were caused by reduced cell population, we repeated the treatment with five cultivated ccRCC and performed a viability assay with Crystal Violet. We obtained results for the therapy response similar to the CellTiter-Glo experiments (Suppl. Fig. 1): The five tested ccRCC cell lines responded similar to the addition of 2-DG with a decrease of cell viability as they displayed a decrease of luminescence in the CellTiter-Glo assay. When 2-DG was added, the cell line of chRCC1 did not display any decrease of cell population in the crystal violet assay while showing no change in luminescence in the CellTiter-Glo assay as well. A statistical analysis was not performed due to the restricted number of samples.

Overall, a decrease of luminescence in the CellTiter-Glo assay correlated with a decreased cell population in the crystal violet assay for the tested cell lines of RCC when 2-DG was added to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Discussion

The cultivation of primary cell cultures of RCC remains challenging. The successful cultivation of previous studies ranges between 40 and 90%, most of them cultivating ccRCC, and depends on the procedure of validation (Yap et al. 2019; Lobo et al. 2016; Cifola et al. 2011; Perego et al. 2005; Bianchi et al. 2010). Common methods are IHC staining and, for ccRCC, VHL sequencing. Recent studies, however, reported that not all ccRCC cells maintain their VHL status in cell culture conditions, despite previous immunohistochemical confirmation of ccRCC (Lobo et al. 2016; Bolck et al. 2019). In our study, all ccRCC cultures except for three, expressed PAX8, VIM, CA9 and CD10 and the VHL status of all tested ccRCC cultures matched the tumor tissue. This indicates the successful and efficient generation of ccRCC cultures.

Most protocols concentrate solely on ccRCC, since this subtype is most commonly available. Due to the focus on ccRCC or other questions of interest, the very few existing studies including pRCC or chRCC did not characterize or validate the reliability of their protocol (Bianchi et al. 2010) (Krawczyk et al. 2017; Valente et al. 2011). Since up to 20% of all RCC cases are non-clear cell RCC, the lack of research of these subtypes becomes eminent. Therefore, specimens of pRCC and even chRCC were successfully included in this study and excessively verified by IHC markers, expressing the tumor markers of the tumors they originated from. This demonstrates the potential of our protocol.

In the ccRCC specimens, an upregulation of glycolysis-related genes and HIF-1 signaling was observed. The metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis is a characteristic feature especially of ccRCC, even under normoxic conditions, which leads to ccRCC being considered as a metabolic disease (Akhtar et al. 2018; Morais et al. 1861; Linehan and Ricketts 2013).

Thus, for the treatment of RCC cultures, the combination of frequently applied TKI and 2-DG was used to specifically target aerobic glycolysis. The potential use of glycolysis inhibitors is focus of several ongoing studies (Akins et al. 2018; Srinivasan et al. 2015). This is the first study targeting patient-derived individual cells of ccRCC, pRCC and even chRCC in an in vitro model combining common TKI and 2-DG. When 2-DG was added to TKI, we observed an additional reduction of cell viability.

Overall, the ccRCC cells responded well to cabozantinib and pazopanib treatment in vitro. Our results indicate an increase in susceptibility to pazopanib when the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) is added for most ccRCC cell lines. In the case of ccRCC17, in which the patient underwent neo-adjuvant treatment with nivolumab and sunitinib, the cells were successfully treated with axitinib and cabozantinib. Since this ccRCC was widely metastatic at the point of diagnosis, the therapeutic options are limited. A response to axitinib and cabozantinib in vitro might be the first step in identifying additional second-line reagents in a patient-individualized therapeutic approach. However, the therapy response on TKI ± 2-DG was individual for each tumor sample, which underlines the importance of personalized approaches for therapy testing. The results of the treatment of pRCC cultures indicate a susceptibility to cabozantinib alone or combined with 2-DG. One culture (pRCC5), which did not respond to AXT alone, showed reduced cell viability when exposed to axitinib and 2-DG, demonstrating a synergistic effect of 2-DG. The same was observed for pazopanib at high concentrations. Although we only exposed two cell cultures of pRCC and four of chRCC, our results justify further research for a potential use of 2-DG or other metabolism-targeting agents against these renal cancer subtypes. While there are therapy standards for the treatment of advanced and metastatic ccRCC, for metastatic pRCC and chRCC, the data are extremely limited and inconclusive. At current state, there is only limited evidence for the efficiency of immune checkpoint inhibitors, which are the first-line approach for ccRCC (Tsimafeyeu 2017). When advanced, pRCC and chRCC are treated mainly with anti-angiogenetic agents like sunitinib or TKI; the benefit in progression-free survival and overall survival depends on the therapeutic setting and the combination of drugs. But none of these studies was able to include more than 109 patients due to the rarity of pRCC and chRCC (Fernández-Pello et al. 2017; Keizman et al. 2016; Ito 2019; Malouf et al. 2017). This demonstrates an urgent need for further data acquisition and clinical research. Our protocol allows the cultivation of these more infrequent tumors as well as the identification and evaluation of possible targets, as demonstrated with the sensitizing effect of 2-DG on TKI treatment in vitro.

The treatment standards for RCC change constantly and demonstrate a need for more therapeutic options. Since also new first-line therapies with avelumab and axitinib and other combinations still showed an objective response of about 55% (Motzer et al. 2019), in vitro therapy testing for second- or third-line option becomes more important. This might facilitate the identification of the most effective therapeutic regime and patient-individualized medicine.

In conclusion, we presented and validated a fast, reliable and simple protocol for the generation of individualized primary cell cultures of RCC entities. Especially, the uncommon pRCC and chRCC subtypes will require further research to investigate their characteristics and to identify possible targets for therapeutics such as cell metabolism. Our study provides the opportunity to design subtype-specific experiments in a patient-individualized in vitro model.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Kerstin Fuchs, Susanne Steiner, Carsten Golletz and Cristina Göbbel for their excellent technical assistance. We furthermore are thankful to the Next Generation Sequencing Core Facility of Bonn University Hospital.

Abbreviations

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- ccRCC

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- pRCC

Papillary renal cell carcinoma

- chRCC

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- VHL

Von Hippel–Lindau gene/protein

- 2-DG

2-Deoxy-d-glucose

- AXT

Axitinib

- PZP

Pazopanib

- CBZ

Cabozantinib

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akhtar M, Al-Bozom IA, Al Hussain T (2018) Molecular and metabolic basis of clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Adv Anat Pathol 25:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins NS, Nielson TC, Le HV (2018) Inhibition of glycolysis and glutaminolysis. An emerging drug discovery approach to combat cancer. Curr Top Med Chem 18:494–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiges L et al (2019) Updated European Association of Urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. Immune checkpoint inhibition is the new backbone in first-line treatment of metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 76:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo JC, Shapiro O (2019) The changing therapeutic landscape of metastatic renal cancer. Cancers 11:1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi C et al (2010) Primary cell cultures from human renal cortex and renal-cell carcinoma evidence a differential expression of two spliced isoforms of Annexin A3. Am J Pathol 176:1660–1670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck HA et al (2019) Tracing clonal dynamics reveals that two- and three-dimensional patient-derived cell models capture tumor heterogeneity of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus. 10.1016/j.euf.2019.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buti S et al (2013) Chemotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma today? A systematic review. Anticancer Drugs 24:535–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio U et al (2019) Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 75:74–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DA et al (2011) Targeting GLUT1 and the warburg effect in renal cell carcinoma by chemical synthetic lethality. Sci Transl Med 3:94ra70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifola I et al (2011) Renal cell carcinoma primary cultures maintain genomic and phenotypic profile of parental tumor tissues. BMC Cancer 11:244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Pello S et al (2017) A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness and adverse effects of different systemic treatments for non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 71:426–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K (2019) Recent advances in the systemic treatment of metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Int J Urol 26:868–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizman D et al (2016) Outcome of patients with metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. Oncologist 21:1212–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2015) HISAT. A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12:357–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk KM et al (2017) Papillary renal cell carcinoma-derived chemerin, IL-8, and CXCL16 promote monocyte recruitment and differentiation into foam-cell macrophages. Lab Investig 97:1296–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H et al (2009) The sequence alignment/map format and SAM tools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W (2014) FeatureCounts. An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30:923–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan WM, Ricketts CJ (2013) The metabolic basis of kidney cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 23:46–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungberg B et al (2015) EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. 2014 update. Eur Urol 67:913–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo NC et al (2016) Efficient generation of patient-matched malignant and normal primary cell cultures from clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Clinically relevant models for research and personalized medicine. BMC Cancer 16:485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouf GG, Joseph RW, Shah AY, Tannir NM (2017) Non–clear cell renal cell carcinomas: biological insights and therapeutic challenges and opportunities. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 15:409–418 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais M, Dias F, Teixeira AL, Medeiros R (2017) MicroRNAs and altered metabolism of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Potential role as aerobic glycolysis biomarkers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861:2175–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ et al (2007) Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ et al (2018) Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 378:1277–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ et al (2019) Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 380:1103–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego RA et al (2005) Primary cell cultures arising from normal kidney and renal cell carcinoma retain the proteomic profile of corresponding tissues. J Proteome Res 4:1503–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuch B et al (2015) Understanding pathologic variants of renal cell carcinoma Distilling therapeutic opportunities from biologic complexity. Eur Urol 67:85–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Ricketts CJ, Sourbier C, Linehan WM (2015) New strategies in renal cell carcinoma. Targeting the genetic and metabolic basis of disease. Clin Cancer Res 21:10–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg CN et al (2013) A randomised, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Final overall survival results and safety update. Eur J Cancer 49:1287–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate JG et al (2019) COSMIC. The catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D941–D947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsimafeyeu I (2017) Management of non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Curr Approaches Urol Oncol 35:5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente MJ et al (2011) A rapid and simple procedure for the establishment of human normal and cancer renal primary cell cultures from surgical specimens. PLoS ONE 6:e19337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H (2016) ggplot2—Elegant graphics for data analysis, 2nd edn. Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- Yap NY et al (2019) Establishment of epithelial and fibroblast cell cultures and cell lines from primary renal cancer nephrectomies. Cell Biol Int. 10.1002/cbin.11150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.