Abstract

Purpose

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) is generally slow growing but has highly metastatic potential to distant organs. Several factors and biomarkers are associated with metastasis and treatment outcomes, although further definition is needed. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the risk factors for survival and distant metastasis in patients with head and neck AdCC.

Methods

This study included 125 patients with previously untreated AdCC who underwent primary surgery with or without radiotherapy in our tertiary referral centre. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to identify risk factors associated with overall survival (OS), cause-specific survival (CSS), disease-free survival (DFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS). Factors associated with OS in patients with distant metastasis were separately analysed.

Results

During a median follow-up of 9.8 years (range 3.0–22.6 years), 58 patients (46.4%) had distant metastasis and 29 (23.2%) died of disease. Multivariate analyses showed that lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis were independent factors of OS and CSS outcomes (all P < 0.05). The T classification and extranodal extension were independent factors of DFS and DMFS outcomes (P < 0.05). After patients presented with distant metastasis, the median survival was 5.8 years. Multivariate analyses showed that extranodal extension and regional recurrence were independent factors of survival after occurrence of distant metastasis (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Several clinicopathological factors can predict distant metastasis and survival of patients with AdCC treated with primary surgery. This may promote post-treatment surveillance in patients with AdCC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00432-020-03170-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adenoid cystic carcinoma, Head and neck, Distant metastasis, Survival, Risk factors

Introduction

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) is a rare malignancy with an annual incidence of 3–4.5 cases per million people, accounting for approximately only 1% of all head and neck malignancies (Bjorndal et al. 2011). AdCC of the head and neck arises in major salivary glands, i.e. the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands; approximately 50% of cases arise in the minor salivary glands and diffusely spread in the upper aerodigestive tract (Bjorndal et al. 2011). AdCC is a major pathological subtype comprising approximately 25% of salivary gland cancer cases; AdCC has 22 subtypes with distinct incidence and diverse biological heterogeneity (Thompson 2006; El-Naggar et al. 2017). AdCC is generally slow growing but is associated with high late recurrence and poor long-term survival rates, and hence is called “a wolf in sheep’s clothing” (Lloyd et al. 2011). The 10-year overall survival (OS) rate of patients with AdCC is 70% but most patients experience recurrence in distant organs as well as in locoregional areas (Lloyd et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2016; He et al. 2017). Currently, the prognosis of AdCC is determined on the basis of tumour size, perineural or lymphovascular invasion, histological grade, surgical margins, tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, and age (van Weert et al. 2013; Coca-Pelaz et al. 2015). These prognostic indicators may be required to better stratify patients with a high risk of unfavourable survival outcomes.

The optimal treatment for AdCC, to achieve local disease control, is surgery with postoperative radiotherapy. Moreover, very late recurrence is a distinct aspect of this disease. Hence, poor long-term survival outcomes of AdCC are associated with high recurrence rates in distant organs, indicating the need for clinical follow-up for at least > 15 years (Coca-Pelaz et al. 2015). In a recent study, 48% of 112 patients treated in two tertiary hospitals had distant metastasis; 94.4% of patients had lung metastasis (Seok et al. 2019). In addition, tumour size, perineural invasion, and local recurrence were risk factors for lung metastasis.

Despite the high rate of distant metastasis in AdCC (up to 70%) (Yu et al. 2007), the prognostic indicators have been rarely investigated considering the distant metastasis and long-term survival of this uncommon disease (Seok et al. 2019). Furthermore, only a few studies have examined the factors associated with patient survival after the occurrence of distant metastasis. The results of further studies may contribute in defining the risk stratification for survival and distant metastasis of patients with AdCC by better understanding the nature of this distinct disease. Therefore, the current study evaluated the risk factors for survival and distant metastasis of patients with AdCC of the head and neck.

Materials and methods

Study patients

Electronic medical records were reviewed to identify patients with previously untreated AdCC who were treated in our tertiary referral centre between 1991 and 2016. Patients were included if they underwent extirpation of tumours with or without postoperative adjuvant therapy and followed up for > 3 years. Patients with distant metastasis at presentation and second cancers were also included. Patients were excluded if they underwent primary radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, had inoperable locally advanced disease or underwent palliative chemotherapy alone, had recurrent AdCC, had a previous history of surgery or irradiation for other head and neck cancers, and did not have sufficient follow-up information. Finally, 125 patients were included in this study. Tumours were staged using the AJCC staging manual (8th ed.) (Lydiatt et al. 2017). This retrospective observational study was approved by the institutional review board of Asan Medical Center, and the need for informed consent from each patient was waived.

Patients underwent extirpation of the primary tumours with tumour-free margins and preservation of adjacent important structures that were not directly invaded by the tumours. Some patients (n = 63, 50.4%) also underwent therapeutic or elective neck dissection; therapeutic neck dissection was performed in patients with clinically nodal metastasis at neck levels I–V, while elective neck dissection was performed at neck levels I–III. Postoperative radiotherapy was administered to 88 patients (70.4%) with adverse pathological findings (Amin et al. 2017a, b), using a total irradiation dose of 62 Gy (range, 44–70 Gy) with a daily dose of 1.8–2.0 Gy for 5 days per week for 5–8 weeks. Nine patients (7.2%) including 7 (5.6%) with distant metastasis at presentation received chemotherapy, mostly using cisplatin.

Patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic every 1–3 months in the first year, 2–4 months in the second years, 6 months in the third–fifth years, and annually thereafter (Denaro et al. 2016). Any suspected locoregional recurrences on examinations and imaging were confirmed via biopsy. Distant recurrences were confirmed via biopsy or serial follow-up imaging if biopsy was not available. Patients with disease relapse underwent salvage surgery or palliative treatments. Of 58 patients with distant metastasis during follow-up, 23 (39.7%) received cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Variables

Clinical records of all patients were reviewed to obtain information about variables, including the age at diagnosis (> 60 years), sex, history of smoking (> 20 pack-years) and alcohol consumption (≥ 1 drink/day), tumour site (minor gland vs major gland), tumour size (≤ 2 cm vs > 2 to ≤ 4 cm vs > 4 cm), extracapsular extension, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, resection margins (negative vs positive), T classification (T1–2 vs T3–4), N classification (N0 vs N1–N3), overall TNM stage (I–II vs III–IV), extranodal extension, treatment modality, postoperative radiotherapy, and the presence of local or regional recurrence and distant metastasis.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint was OS. Secondary endpoints were cause-specific survival (CSS), disease-free survival (DFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS). Continuous and categorical variables were compared between patients with and without distant metastasis at presentation and during follow-up by using the t-test and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, respectively. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to determine the significant predictors of survival. Multivariate models were obtained using a backward stepwise selection procedure with all the variables with P < 0.1 on univariate analysis. Variables with multi-collinearity were separately fitted in the multivariable model (Vatcheva et al. 2016). Factors associated with OS of patients with distant recurrence were separately analysed. The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Kaplan–Meier curves were obtained to estimate mortality, recurrence, and mortality after the presentation of distant metastasis, and log-rank tests were used to determine the statistical significance. All statistical tests were two tailed, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 24.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient characteristics

The current study included 125 patients, 52 men (41.6%) and 73 women (58.4%), with a median age of 52 years (range 13–79 years). The patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. Tumours were most commonly found in the minor salivary glands of the head and neck (n = 53, 42.4%), followed by the parotid gland (n = 35, 28.0%), submandibular gland (n = 28, 22.4%), and sublingual gland (n = 9, 7.2%). Tumour perineural invasion and lymphovascular invasion were found in 59 (47.2%) and 32 patients (25.6%), respectively. Positive resection margins were observed in 62 patients (49.6%). Locally advanced T3–T4 tumours were observed in 60 patients (48.0%), and advanced overall III–IV stage in 63 (50.4%). Lymph node metastasis was also found in 15 patients (12.0%), mainly in the neck level I or II (93.3%) with the positive lymph node number of median 2 (range 1–65). Extranodal extension was noted in 9 patients (7.2%). Initial distant metastasis was observed in 7 patients (5.6%). The patients were followed up for a median of 9.8 years (range 3.0–22.6 years). At the last follow-up, 52 patients (41.6%) were alive without disease, 35 (28.0%) were alive with disease (mostly distant metastasis), 29 (23.2%) had died of disease, and 9 (7.2%) had died of other causes. During follow-up, recurrence at any site was found in 76 patients (60.8%): local recurrence in 34 patients (27.2%), regional in 6 (4.8%), and distant in 58 (46.4%), with overlapping recurrence sites in some patients. Of 58 patients with distant metastasis, 55 (94.8%) had lung metastasis and 14 (11.2%) had metastasis to multiple distant organs. The median time to distant metastasis was 32.7 months (interquartile range 12.5–62.6 months): 33.5 months for lung metastasis alone and 26.0 months for multiple organ metastasis (t-test, P = 0.474).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 125)

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 52 (13–79) | |

| Sex, male | 52 | 41.6 |

| Tumour site | ||

| Parotid gland | 35 | 28.0 |

| Submandibular gland | 28 | 22.4 |

| Sublingual gland | 9 | 7.2 |

| Minor gland | 53 | 42.4 |

| Tumour size (cm), median (range) | 2.9 (0.5–10.0) | |

| TNM stage (AJCC 8th ed.) | ||

| T1/T2/T3/T4a/T4b | 17/48/30/25/5 | 13.6/38.4/24.0/20.0/4.0 |

| N0/N1/N2b/N3b | 110/2/4/9 | 88.0/1.6/3.2/7.2 |

| I/II/III/IVA/IVB/IVC | 16/46/27/20/9/7 | 12.8/36.8/21.6/16.0/7.2/5.6 |

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery alone | 37 | 29.6 |

| Surgery and PORT | 88 | 70.4 |

| Chemotherapy | 9 | 7.2 |

| Follow-up (years), median (range) | 9.8 (3.0–22.6) | |

| Last status, NED/AD/DOD/DOC | 52/35/29/9 | 41.6/28.0/23.2/7.2 |

| Recurrence, any site/local/regional/distanta | 76/34/6/58 | 60.8/27.2/5.2/46.4 |

AD alive with disease, DOC died of other cause, DOD died of disease, DM distant metastasis, NED no evidence of disease, PORT postoperative radiotherapy, TNM pathological tumour-node-metastasis staging proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 8th edition)

a With overlapping recurrence sites in some patients

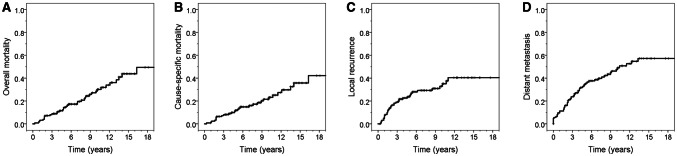

When the characteristics were compared between the patients with and without distant metastasis, smoking status, tumour extracapsular extension, T and N classifications, overall TNM stage, extranodal extension, and mortality were significantly higher in patients with distant metastasis than in those without distant metastasis (all P < 0.05; Supplementary Table S1). The 10- and 20-year OS rates of all patients were 71.4% (95% CI 66.7–76.1%) and 50.6% (42.7–58.5%), respectively. The 10- and 20-year CSS rates were 78.5% (72.3–82.7%) and 57.8% (49.4–66.2%), respectively. The 5- and 10-year DFS rates were 52.2% (47.6–56.8%) and 37.9% (33.1–42.7%), respectively. The 5- and 10-year DMFS rates were 65.4% (61.0–69.8%) and 52.4% (47.4–57.4%), respectively (Fig. 1). The 10-year OS rates were significantly different between patients without and those with distant metastasis (81.5% [75.8–87.2%] vs 60.2% [53.0–67.4%], P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence curves of overall survival (a), cause-specific survival (b), local recurrence (c), and distant metastasis (d) for all the included patients

Factors associated with OS, CSS, DFS, and DMFS outcomes

Univariate analyses showed that age (> 60 years), second cancer, tumour size, perineural and lymphovascular invasion, T classification (T3–T4), lymph node metastasis, overall TNM stage (III–IV), extranodal extension, and distant recurrence were significant factors associated with poor OS outcomes (all P < 0.05, Supplementary Table S2). T classification (T3–T4), lymph node metastasis, extranodal extension, and distant recurrence were also the significant factors predictive of poor CSS outcomes (all P < 0.05). Smoking (> 20 pack-years), tumour size (> 4 cm), T classification (T3–T4), lymph node metastasis, overall TNM stage (III–IV), and extranodal extension were significantly associated with poor DFS and DMFS outcomes (all P < 0.05). Extracapsular extension and perineural invasion were also significant predictors of poor DMFS outcomes (P < 0.05). Multivariate analyses revealed that lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and distant recurrence remained independent factors of OS and CSS outcomes (all P < 0.05; Table 2). T classification and extranodal extension were independent factors of DFS and DMFS outcomes (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses of factors affecting overall survival, cause-specific survival, disease-free survival, and distant metastasis-free survival

| Variable | OS | CSS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | Pa | HR (95% CI) | Pa | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 2.46 (1.11–5.44) | 0.027* | 3.26 (1.28–8.28) | 0.013* |

| LN metastasis | 4.24 (1.84–9.77) | 0.001* | 3.47 (1.36–8.82) | 0.009* |

| Distant metastasisb | 3.41 (1.63–7.14) | 0.001* | 13.64 (4.00–46.46) | < 0.001* |

| DFS | DMFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | Pa | HR (95% CI) | Pa | |

| T3–T4 classification | 2.09 (1.29–3.41) | 0.003* | 2.77 (1.53–5.02) | 0.001* |

| Extranodal extension | 2.51 (1.15–5.47) | 0.021* | 3.58 (1.60–5.02) | < 0.001* |

CI confidence interval, CSS cause-specific survival, DMFS distant metastasis-free survival, DFS disease-free survival, LN lymph node, OS overall survival, PORT postoperative radiotherapy, TNM pathological tumour-node-metastasis staging proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 8th edition)

aMultivariate models were prepared using a backward stepwise selection procedure with all the variables with P < 0.1 on univariate analysis (Supplementary Table S1). *P < 0.05

bAt the time of disease presentation and follow-up

Factors associated with overall survival after the presentation of distant metastasis

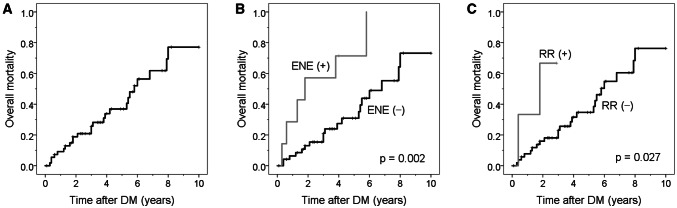

Of 58 patients, 26 (44.4%) with overall distant metastasis died of disease during the median follow-up of 3.5 years (range, 0.2–10 years). Factors associated with OS after the presentation of distant metastasis were analysed in the 58 patients. Univariate analyses showed that tumour lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and extranodal extension at presentation, as well as regional recurrence were significantly associated with shorter OS (all P < 0.05; Table 3). Multivariate analyses revealed that extranodal extension and regional recurrence remained independent factors of post-distant metastasis survival (P < 0.05). Patients with extranodal extension had a 4.17-fold increase in the risk of mortality and patients with regional recurrence had a 7.26-fold increase in the risk of mortality, compared with their counterparts. After the presentation of distant metastasis, the median survival of patients was 5.8 years (95% CI, 4.9–6.6 years). The 5- and 10-year OS rates of all 58 patients were 63.1% (95% CI 55.7–70.5%) and 22.9% (95% CI 12.8–33.0%), respectively (Fig. 2). The 5-year survival rates of patients with and without extranodal extension were 28.6% (95% CI 11.5–34.2%) and 69.1% (95% CI 61.4–76.8%), respectively (P = 0.002).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors influencing overall survival after the presentation of distant metastasis

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | Pa |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Age, > 60 years | 1.35 (0.58–3.13) | 0.491 |

| Sex, male | 0.83 (0.37–1.86) | 0.655 |

| Smoking, > 20 pack-years | 1.07 (0.40–2.87) | 0.892 |

| Alcohol, ≥ 1 drink/day | 1.13 (0.47–2.74) | 0.783 |

| Second cancer | 2.50 (0.95–6.59) | 0.064 |

| Tumour site, minor gland | 1.50 (0.65–3.49) | 0.343 |

| Tumour size | 1.12 (0.76–1.39) | 0.859 |

| Extracapsular extension | 1.10 (0.49–2.49) | 0.813 |

| Perineural invasion | 1.65 (6.70–3.90) | 0.254 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 2.76 (1.12–6.77) | 0.027* |

| T classification, T3–T4/T1–T2 | 1.08 (0.70–1.66) | 0.730 |

| LN metastasis, N1–N3/N0 | 3.89 (1.55–9.77) | 0.004* |

| Overall TNM stage, III–IV/ I–II | 1.08 (0.70–1.66) | 0.730 |

| Extranodal extension | 4.26 (1.55–10.43) | 0.004* |

| Initial PORT | 1.25 (0.48–3.25) | 0.649 |

| Initial chemotherapy | 1.61 (0.54–4.79) | 0.395 |

| Local recurrence | 0.42 (0.16–1.12) | 0.082 |

| Regional recurrence | 4.78 (1.03–22.21) | 0.046* |

| Multiple distant organs involved | 2.21 (0.97–5.05) | 0.060 |

| Chemotherapy for recurrence | 1.28 (0.55–2.96) | 0.567 |

| Multivariate analysisb | ||

| Extranodal extension | 4.17 (1.57–11.10) | 0.004* |

| Regional recurrence | 7.26 (1.49–35.40) | 0.014* |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

aUnivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models, *P < 0.05

bThe multivariate models were prepared using a backward stepwise selection procedure with all the variables with P < 0.1 on univariate analysis. *P < 0.05

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of overall survival after the presentation of distant metastasis (DM, a) and according to the presence of extranodal extension (ENE, b) and regional recurrence (RR, c). Log-rank test, P < 0.05

Discussion

The results of the present study suggested that several clinicopathological factors predicted survival, recurrence, and distant metastasis after primary surgery for head and neck AdCC. The cohort in the current study included a relatively large number of patients (n = 125) with a median follow-up of almost 10 years after surgery. The largest series till date analysed the records from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (1973–2007) in the USA by including 3026 patients with head and neck AdCC; the 5- and 10-year OS rates were 90.3% and 79.9%, respectively (Ellington et al. 2012). In another study of 1425 patients with AdCC using the SEER database (2004–2013), the 5-year OS and CSS were 76.8% and 82.6%, respectively, for a median follow-up of 4.7 years (Shen et al. 2017). In a study using data of 201 patients with AdCC from the national Danish salivary gland carcinoma database (1995–2005), the 10-year OS, CSS, DFS, and DMFS rates were 58%, 75%, 64%, and 82%, respectively, during a median follow-up of 7.5 years (Bjorndal et al. 2011). In a multicentre study in Japan, the 5-year OS was 82.2% for 103 patients during a median follow-up of 4.2 years (Takebayashi et al. 2018). A recent study from South Korea included 112 patients with AdCC from two hospitals who had 10-year lung metastasis and local recurrence rates of 55.2% and 35.5%, respectively, during a median follow-up of 5 years (Seok et al. 2019). The present study reported the 10-year OS, CSS, DFS, and DMFS rates to be 71.4%, 78.5%, 37.9%, and 52.4%, respectively. Most other published studies included less than 100 patients from a single institution, because of the rarity of AdCC (Ali et al. 2017; Hametoja et al. 2017). The survival and recurrence rates reported till date varied among different institutions and countries, without clear description in some studies. However, the most challenging aspect of this rare disease is the high rate of long-term recurrences at local sites as well as to distant organs.

AdCC is a slow-growing tumour characterised by perineural invasion and multiple local recurrences with a relatively low potential of cervical lymphatic metastasis, although haematogenous metastasis to the lungs, bone, and liver is common (Kokemueller et al. 2004; Coca-Pelaz et al. 2015). AdCC is a high-grade malignancy, as it is not often curable and because it has continuously decreasing 10-, 20-, and 30-year survival rates, despite optimistic 5-year survival rates. The actuarial local recurrence rate was 54–100% at 30 years (Jones et al. 1997; DeAngelis et al. 2011). The very low long-term survival rate is uniformly associated with distant site failures, which are difficult to be controlled and are most frequently observed in the lungs (Spiro 1997): the median time to the occurrence of lung metastasis was 32.3 months and the median time to death from lung metastasis was 20.6 months. Lung metastasis can occur prior to the clinical presentation of primary AdCC, indicating a relatively high incidence of initial lung metastasis (Umeda et al. 1999). In the present study, the median time to the presentation of distant metastasis was 32.7 months and the median time to death from distant metastasis was 70 months, with the 3-, 5-, and 10-year distant metastasis rates of 23.7%, 34.6%, and 47.6%, respectively. Our results were similar to those of a previous study that showed that the median time to lung metastasis was 32.0 months, with the 3-, 5-, and 10-year lung metastasis rates of 24.9%, 39.9%, and 55.2%, respectively (Seok et al. 2019). Therefore, the factors associated with recurrence and distant metastasis might help to guide clinicians in risk stratification.

The prognostic factors for AdCC were the origin site, tumour size, perineural or lymphovascular invasion, solid histological pattern, lymph node metastasis, and advanced stage (Ellington et al. 2012). An early study including 196 patients with AdCC who underwent definitive treatments between 1939 and 1986 showed that the 10- and 20-year OS rates were 48% and 25%, respectively (Spiro 1997). Overall, distant metastasis was found in 74 patients (37.8%), of whom 67 (90.5%) had lung metastasis. Tumour size and nodal positivity were significant factors associated with distant metastasis. Lymph node metastasis and a high positive lymph node ratio (≥ 0.2) have also been strongly associated with distant metastasis (Liu et al. 2015). A recent study also showed that the risk factors for lung metastasis were tumour size (≥ 2.5 cm), perineural invasion, and local recurrence (Seok et al. 2019). In the present study, advanced tumour classification and extranodal extension were the independent factors predictive of DFS and DMFS outcomes. Extranodal extension is associated with an increased risk of post-treatment recurrence and death in patients with head and neck cancer (Kwon et al. 2015). In line with this finding, the recent version (8th edition) of the AJCC TNM staging system revised the N classification by including extranodal extension to increase the robustness of the staging system for predicting and discriminating survival rates of patients with head and neck cancer including salivary gland cancer (Amin et al. 2017a, b; Lydiatt et al. 2017). Extranodal extension, a histological grade, and N classification were independent indicators of recurrence and survival (Yoo et al. 2015). In the present study, lymph node metastasis and lymphovascular invasion were not independent predictors for recurrence or distant metastasis but they were for OS and CSS outcomes. Our results are partly consistent with the finding that lymphovascular invasion was associated with an increased likelihood of lymph node metastasis, resulting in significantly lower OS and DFS outcomes (Martins-Andrade et al. 2019). The present study also determined the factors associated with survival after the presentation of distant metastasis: extranodal extension and regional recurrence were independent factors. Therefore, the prognostic significance of extranodal extension should be continuously considered to determine the post-distant metastasis survival as well as to predict recurrence and distant metastasis.

The presentation of multiple local recurrence as well as distant metastasis is an important characteristic of AdCC (Coca-Pelaz et al. 2015). As shown in previous studies (Seok et al. 2019) and in the current study, the local recurrence rates continuously increased along with the time since treatment. The standard treatment for resectable AdCC is radical resection, thereby ensuring tumour-free margins. However, the goal of tumour-free margins is often not achieved, particularly in cases of tumours located deeply and in those with perineural or vascular invasion. This contributes to the considerably high local recurrence rates, which might be reduced by postoperative radiotherapy (Mendenhall et al. 2004). Postoperative radiotherapy might delay rather than prevent local recurrence, and unfortunately, there might be no gains in survival despite severe late adverse effects (Katz et al. 2002). Contemporary systemic chemotherapy may improve the quality of life but not survival in patients with AdCC and distant metastasis (Iseli et al. 2009). The present study showed a high incidence of positive resection margins from primary surgery that did not contribute to the increased recurrence rates, which might have resulted from the benefit of postoperative radiotherapy. However, cytotoxic chemotherapy appeared not to cure recurrence or distant metastasis, resulting in no impact on the survival after distant metastasis.

This study has limitations owing to the analytical problems associated with its retrospective nature. The number of patients might not be adequate for statistical analyses, resulting in different statistical significance. Moreover, the present study did not analyse the histological grade in terms of its relationship with recurrence and survival because of no recommendation in the recent WHO classification for salivary gland tumours (El-Naggar et al. 2017). Nonetheless, our results seem reliable owing to the long-term median follow-up of 9.8 years in a relatively large cohort of 125 patients with this rare disease. The results need to be proved by further analyses using multi-institutional accumulated data of head and neck AdCC in Korea. Alternative approaches, e.g. photon therapy, proton therapy or other particle therapy, might be applied to the primary or secondary treatment options of AdCC over primary surgery, which should be further studied.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that several clinicopathological factors can predict distant metastasis and survival of patients with AdCC treated with primary surgery. Lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis were significantly associated with OS and CSS outcomes. Extranodal extension was the most important factor predictive of recurrence and distant metastasis as well as survival after distant metastasis. Our results may promote the need for post-treatment surveillance in patients with AdCC.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), the Government of Korea (No. 2019R1A2C2002259) (J.-L.R.).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research board, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent from all individual participants was waved because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ali S, Palmer FL, Katabi N, Lee N, Shah JP, Patel SG, Ganly I (2017) Long-term local control rates of patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck managed by surgery and postoperative radiation. Laryngoscope 127(10):2265–2269. 10.1002/lary.26565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK (eds) (2017a) AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edn. Springer, New York, pp 149–161 [Google Scholar]

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK (eds) (2017b) AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edn. Springer, New York, pp 507–515 [Google Scholar]

- Bjorndal K, Krogdahl A, Therkildsen MH, Overgaard J, Johansen J, Kristensen CA, Homoe P, Sorensen CH, Andersen E, Bundgaard T, Primdahl H, Lambertsen K, Andersen LJ, Godballe C (2011) Salivary gland carcinoma in Denmark 1990–2005: a national study of incidence, site and histology. Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Oral Oncol 47(7):677–682. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, Vander Poorten V, Triantafyllou A, Hunt JL, Strojan P, Rinaldo A, Haigentz M Jr, Takes RP, Mondin V, Teymoortash A, Thompson LD, Ferlito A (2015) Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update. Oral Oncol 51(7):652–661. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis AF, Tsui A, Wiesenfeld D, Chandu A (2011) Outcomes of patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the minor salivary glands. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40(7):710–714. 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denaro N, Merlano MC, Russi EG (2016) Follow-up in head and neck cancer: do more does it mean do better? A systematic review and our proposal based on our experience. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 9(4):287–297. 10.21053/ceo.2015.00976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar AK, Chan J, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (2017) Tumours of salivary glands in WHO classification of tumours, vol 9, 4th edn. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 159–201 [Google Scholar]

- Ellington CL, Goodman M, Kono SA, Grist W, Wadsworth T, Chen AY, Owonikoko T, Ramalingam S, Shin DM, Khuri FR, Beitler JJ, Saba NF (2012) Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: incidence and survival trends based on 1973–2007 surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. Cancer 118(18):4444–4451. 10.1002/cncr.27408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hametoja H, Hirvonen K, Hagstrom J, Leivo I, Saarilahti K, Apajalahti S, Haglund C, Makitie A, Back L (2017) Early stage minor salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma has favourable prognosis. Virchows Arch 471(6):785–792. 10.1007/s00428-017-2163-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Li P, Zhong Q, Hou L, Yu Z, Huang Z, Chen X, Fang J, Chen X (2017) Clinicopathologic and prognostic factors in adenoid cystic carcinoma of head and neck minor salivary glands: a clinical analysis of 130 cases. Am J Otolaryngol 38(2):157–162. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseli TA, Karnell LH, Graham SM, Funk GF, Buatti JM, Gupta AK, Robinson RA, Hoffman HT (2009) Role of radiotherapy in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. J Laryngol Otol 123(10):1137–1144. 10.1017/s0022215109990338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AS, Hamilton JW, Rowley H, Husband D, Helliwell TR (1997) Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 22(5):434–443. 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1997.00041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz TS, Mendenhall WM, Morris CG, Amdur RJ, Hinerman RW, Villaret DB (2002) Malignant tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Head Neck 24(9):821–829. 10.1002/hed.10143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim W, Lee J, Ki Y, Lee B, Cho K, Kim S, Nam J, Lee J, Kim D (2016) Pretreatment maximum standardized uptake value of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a predictor of distant metastasis in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 38(5):755–761. 10.1002/hed.23953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokemueller H, Eckardt A, Brachvogel P, Hausamen JE (2004) Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—a 20 years experience. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 33(1):25–31. 10.1054/ijom.2003.0448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Roh JL, Lee J, Cho KJ, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY (2015) Extranodal extension and thickness of metastatic lymph node as a significant prognostic marker of recurrence and survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 43(6):769–778. 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Fang Z, Dai T, Zhang C, Sun J, He Y (2015) Higher positive lymph node ratio indicates poorer distant metastasis-free survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma patients with nodal involvement. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 43(6):751–757. 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S, Yu JB, Wilson LD, Decker RH (2011) Determinants and patterns of survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck, including an analysis of adjuvant radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol 34(1):76–81. 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181d26d45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydiatt WM, O’Sullivan B, Patel SG, Shah JP. AJCC cancer staging manual. In: Amin M, Edge S, Greene FL, Byrd D, Brookland RK, Washington MK, eds. 8th ed. New York: Springer, 2017, 95–102.

- Martins-Andrade B, Dos Santos Costa SF, Sant'ana MSP, Altemani A, Vargas PA, Fregnani ER, Abreu LG, Batista AC, Fonseca FP (2019) Prognostic importance of the lymphovascular invasion in head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol 93:52–58. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall WM, Morris CG, Amdur RJ, Werning JW, Hinerman RW, Villaret DB (2004) Radiotherapy alone or combined with surgery for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 26(2):154–162. 10.1002/hed.10380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seok J, Lee DY, Kim WS, Jeong WJ, Chung EJ, Jung YH, Kwon SK, Kwon TK, Sung MW, Ahn SH (2019) Lung metastasis in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 10.1002/hed.25942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Sakamoto N, Yang L (2017) Model to predict cause-specific mortality in patients with head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: a competing risk analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 24(8):2129–2136. 10.1245/s10434-017-5861-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro RH (1997) Distant metastasis in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary origin. Am J Surg 174(5):495–498. 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00153-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi S, Shinohara S, Tamaki H, Tateya I, Kitamura M, Mizuta M, Tanaka S, Kojima T, Asato R, Maetani T, Ushiro K, Kitani Y, Ichimaru K, Honda K, Yamada K, Omori K (2018) Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: a retrospective multicenter study. Acta Otolaryngol 138(1):73–79. 10.1080/00016489.2017.1371329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L (2006) World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Ear Nose Throat J 85(2):74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda M, Nishimatsu N, Masago H, Ishida Y, Yokoo S, Fujioka M, Shibuya Y, Komori T (1999) Tumor-doubling time and onset of pulmonary metastasis from adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 88(4):473–478. 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70065-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weert S, Bloemena E, van der Waal I, de Bree R, Rietveld DH, Kuik JD, Leemans CR (2013) Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: a single-center analysis of 105 consecutive cases over a 30-year period. Oral Oncol 49(8):824–829. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH (2016) Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale) 6(2):227. 10.4172/2161-1165.1000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Roh JL, Kim SO, Cho KJ, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY (2015) Patterns and treatment of neck metastases in patients with salivary gland cancers. J Surg Oncol 111(8):1000–1006. 10.1002/jso.23914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Gao QH, Wang XY, Wen YM, Li LJ (2007) Malignant sublingual gland tumors: a retrospective clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Oncology 72(1–2):39–44. 10.1159/000111087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.