Significance

Continued fate-maintenance of the uterine simple columnar epithelium is essential for embryo implantation, with concordant reports of pathologic plasticity resulting in fertility deficits. The mechanisms by which uterine cell-fate is actively maintained have long remained elusive. The present study demonstrates that retinoic acid (RA) signaling plays critical roles in maintaining the simple columnar morphology of the adult uterine epithelium via continuous antagonization of estrogen signaling. Mice lacking RA receptors in the adult uterus exhibit complete transdifferentiation of uterine epithelium into cervicovaginal-like epithelium, which can be prevented by attenuating estrogen signaling. The delicate balance between these two critical signaling pathways may explain uterine pathology induced by in utero exposure to diethylstiblestrol, an endocrine disruptor that has affected millions of pregnancies world-wide.

Keywords: female reproductive tract, cell-fate, retinoic acid, diethylstilbestrol

Abstract

Classical tissue recombination experiments demonstrate that cell-fate determination along the anterior–posterior axis of the Müllerian duct occurs prior to postnatal day 7 in mice. However, little is known about how these cell types are maintained in adults. In this study, we provide genetic evidence that a balance between antagonistic retinoic acid (RA) and estrogen signaling activity is required to maintain simple columnar cell fate in adult uterine epithelium. Transdifferentiation of simple columnar uterine epithelium into stratified cervicovaginal-like epithelium was observed in three related mouse genetic models, in which RA signaling was perturbed in the postnatal uterus. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis identified the transformed epithelial cell populations and revealed extensive immune cell infiltration resulting from loss of RA signaling. Surprisingly, disruption of RA signaling led to dysregulated expression of a substantial number of estrogen target genes, suggesting that these two pathways may functionally oppose each other in determining and maintaining uterine epithelial cell fate. Consistent with this model, neonatal exposure to the strong synthetic estrogen, diethylstilbestrol, downregulated expression of a group of RA target genes and led to epithelial stratification and immune cell infiltration in wild-type uterus. Treating RA receptor triple conditional knockout pups with fulvestrant, an estrogen antagonist, reestablished the balance between the two signaling pathways, and effectively prevented the transformation of mutant simple columnar epithelia to metaplastic stratified epithelia. These findings implicate an essential role for RA signaling in maintaining uterine cytodifferentiation by antagonizing estrogen signaling in the postnatal uterus.

The embryonic paramesonephric duct, also known as the Müllerian duct, undergoes intricate patterning orchestrated by a symphony of genetic and cellular interactions to form the majority of the mammalian female reproductive tract (FRT). Following its formation, the homogenous Müllerian duct next differentiates into segments along the anterior–posterior (A–P) axis with each segment developing into distinct structures (i.e., oviduct, uterus, cervix, and upper vagina). Central to this segmentation event is the AbdominalB Hox genes, which provide instructional positional information along the A-P axis. A number of posterior Hoxa genes express in nested patterns along the A-P axis in the developing Müllerian duct, establishing a “Hox code” that serves as a blueprint for the regional identity within the FRT (1, 2). Mutations in these genes result in profound homeotic transformations and functional disruptions, often leading to infertility (3, 4). In addition to the Hox genes, WNT/β-catenin signaling plays pivotal roles in both the uterine and vaginal epithelia by promoting cell proliferation, differentiation, and gland formation in the uterus, as well as stratification and maintenance of the vaginal epithelium (5–8). Transcription factors such as FOXA2 and genes involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, such as MMPs and TIMPS, further modulate these processes by regulating genes essential for epithelial cell identity and function in the uterus (9, 10). In contrast, the differentiation of vaginal epithelium is largely dependent on TRP63, which maintains progenitor cell populations necessary for ongoing renewal and barrier formation (11). Additionally, regulators such as FGF signaling, RUNX1, and SIX1 play critical roles in guiding tissue morphogenesis and defining cellular identity, which are essential for the proper differentiation and maintenance of the vaginal epithelium (12, 13). Estrogen receptor (ER) signaling, particularly through ESR1, is crucial for lower Müllerian duct differentiation by enhancing proliferation, as loss of Esr1 or in combination with Esr2 leads to aberrant vaginal epithelial differentiation or keratinization (14–16). This complex network of genetic and hormonal signals ensures that each segment of the Müllerian duct develops appropriately, reflecting the unique physiological roles of the uterus and vagina in reproductive biology.

Classical tissue recombination experiments have provided foundational evidence demonstrating that cell-fate determination along the A–P axis of the FRT hinges on the reciprocal communication between the epithelium and the mesenchyme (17). In mice, the critical period for FRT epithelial cell-fate determination occurs between postnatal days 5 to 7, guided by mesenchymal signals (18). For instance, the neonatal Müllerian epithelium has the potential to develop into either simple columnar uterine epithelium or stratified squamous vaginal epithelium, depending on the source of underlying mesenchyme (18). Even though the nature of the mesenchymal cues remains to be elucidated, it is suggested that these stromal signals are controlled by the Hox genes, since ectopic expression of the vaginally restricted HOXA13 homeodomain in the form of a hybrid HOXA11-HOXA13 fusion protein in the uterine stroma resulted in stratification of the uterine epithelium (19). Notably, once the FRT epithelium reaches maturity, its plasticity appears limited, suggesting that the capacity for such mesenchymal-induced transformation diminishes after development (18). The differences in epithelial architecture reflect specialized and finely tuned functions of each region within the reproductive tract — simple columnar epithelium is essential for embryo implantation and gestation in the uterus, whereas stratified epithelium provides a protective barrier as a defense mechanism in the vagina.

Despite advancements in understanding developmental processes, there remains a striking knowledge gap regarding how uterine cell fate is maintained in adulthood. Ovarian hormones may be key players in this process. Estrogen is known to stimulate proliferation and growth within the FRT which prepares the uterine lining for pregnancy. Ovariectomy in mice causes FRT atrophy and turns the vaginal epithelium into two layers of cuboidal cells, and 17beta-estradiol (E2) treatment fully restores it back to keratinized squamous epithelium (16). Genetic ablation of estrogen receptor 1 (Esr1) via keratin 5-cre leads to a failure of the vaginal epithelium to undergo keratinization. However, this effect can be mitigated to some extent with the application of amphiregulin, a growth factor that aids in epithelial differentiation (16). Neonatal exposure to DES, a strong synthetic estrogen, leads to alterations in uterine morphology including squamous metaplasia (20). Progesterone, working in concert with estrogen, facilitates differentiation, prepares the endometrium for implantation and pregnancy. This hormonal interplay is underscored by the regulatory loop between ESR1 that controls the progesterone receptor (PGR) expression in a tissue specific manner and PGR signaling which in turn modulates ESR1 activity, together maintaining a delicate equilibrium within the uterine environment (21).

It has long been known that vitamin A deficiency causes uterine metaplasia, although the underlying mechanism remains elusive (22). Retinoic acid (RA), the bioactive derivative of vitamin A (retinol), is a critical signaling molecule that exerts its effects by regulating gene expression [for review (23)]. RA traverses the intracellular space of target cells to bind to its nuclear receptors, RA receptors (RARs), which dimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRs). The RAR/RXR heterodimers, upon binding to RA, undergo a conformational change that facilitates their interaction with coactivators which subsequently bind to RA response elements (RAREs) located in the promoter regions of target genes. In the absence of RA, RAR/RXR heterodimers associate with corepressor proteins, maintaining target genes in a repressed state. This ligand-dependent switch from repression to activation is a central feature of RAR signaling, allowing for tight spatial and temporal control of gene expression. The downstream effects of RAR signaling are extensive and context-dependent, involving a myriad of target genes that govern cell cycle progression, apoptosis, differentiation, and patterning. During embryonic development, RAR signaling is indispensable for the proper formation of the A-P axis and the development of many organs including the central nervous system, heart, craniofacial structures and limbs (24–27). In adult tissues, this signaling pathway continues to play a vital role in maintaining cellular differentiation and function.

This study presents compelling genetic evidence that illuminates the crucial role of RAR signaling as a missing link that counterbalances ER signaling in maintaining postnatal uterine epithelium cell fate. This finding marks a paradigm shift in our understanding of uterine cell-fate determination and maintenance and suggests that cellular identity in the adult uterus is not as permanently fixed as previously thought, but rather is a dynamic state sustained by the interplay between RAR and ER signaling pathways.

Results

Age-Dependent Morphological Changes in the RaraDNPgr Uterine Epithelium.

Previously, we uncovered a crucial role for endogenous RAR signaling in female fertility by expressing one allele of the dominant-negative variant of RA receptor alpha (RaraDNPgr) in the pregnant uterus which led to almost complete female sterility (28). This impairment in fertility was predominantly caused by compromised uterine receptivity and the decidualization process, despite normal reproductive tract morphology. These findings underscore a pivotal role of RAR signaling in the early stages of pregnancy. Surprisingly, however, closer examination of the RaraDNPgr uterus revealed dramatic morphological changes upon aging. By 14 mo, a conspicuous swelling of the mutant uterine horns was noted as compared to age-matched controls (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the mutant uterine lumens were found to contain large lumps of shed cells mixed with trapped fluid upon dissection (Fig. 1A, inset). Histological analyses revealed epithelial stratifications within many segments of the luminal epithelium (LE) in the aged RaraDNPgr uteri (Fig. 1B), deviating from the normal simple columnar epithelial architecture. The incidence of this altered morphology correlated with age and was present in four of six mutants at 14 mo, while none was observed in younger 8-mo mutant mice.

Fig. 1.

Age-dependent epithelial metaplasia in the RaraDNPgr uterus. (A) Comparative gross morphology of uteri from 14-mo control and RaraDNPgr mice. The inset shows the white cell lump accumulated inside the mutant uterine horn upon dissection. (B) H&E staining of a 14-mo RaraDNPgr uterine section. (C and D) IF staining for TRP63 (green) and FOXA2 (red) in control (C) and RaraDNPgr (D) uteri, with nuclear counterstaining with DAPI (blue). High-magnification views of the indicated areas in panel D are shown in E and F, respectively. Arrows in C indicate FOXA2-positive uterine glands. Arrows in D mark regions of the TRP63-positive mutant epithelium devoid of FOXA2 expression. Arrowheads and arrow in E point to TRP63-positive basal epithelial and FOXA2-positive suprabasal epithelial cells, respectively. (G–I) IF staining against SIX1 in the uterus (G) and vagina (H) of aged control mice, and the aged RaraDNPgr uterus (I). (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

To better define the epithelial cell type in the mutant epithelium, we employed immunofluorescence (IF) staining against FOXA2 and TRP63, transcription factors expressed in specific epithelial cell populations. FOXA2 is expressed in the oviductal, cervical superficial, and mature uterine glandular epithelial cells (GE) (9), whereas TRP63 is expressed in the basal and parabasal cells of the cervical and vaginal epithelia (VE) (11). The aged RaraDNPgr uterus exhibited robust TRP63 expression within the basal layers of the stratified LE cells (Fig. 1D). Some TRP63-positive regions also coexpressed FOXA2 in the parabasal cells, suggesting a shift toward cervical-like morphology (Fig. 1E), while other regions of the mutant uterus retained normal uterine histology (Fig. 1F). On the other hand, TRP63-positive areas devoid of FOXA2 staining would be consistent with a vaginal-like transdifferentiation (Fig. 1D, arrows). This was corroborated by IF staining against SIX1, another marker for VE, which showed regional metaplasia of the RaraDNPgr LE (Fig. 1 G–I). Notably, we detected a pronounced cell population with green autofluorescence in the mutant stromal compartment, potentially indicative of immune cell infiltration, which will be discussed later. These morphological and molecular alterations demonstrate an age-dependent shift in epithelial cell types within the RaraDNPgr uterus, suggesting potential roles of RAR signaling in determination and maintenance of epithelial identity in the FRT.

Indispensable Role of RAR Signaling in Preserving Uterine Epithelial Cell Identity.

The transdifferentiation of uterine LE cells into stratified squamous epithelial cells resembling that of cervical and vaginal epithelium in RaraDNPgr mice prompted us to investigate the role of RAR signaling during normal uterine homeostasis. We first examined the expression profiles of all three RARs in the murine uterus at postnatal day 20 (PD 20). Quantitative RT-PCR revealed the presence of Rarα (Rara) and Rarγ (Rarg) at comparable levels, with Rarβ (Rarb) expression approximately 100-fold lower than its two paralogs (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). IF staining was employed to determine cellular and subcellular localizations of RARA and RARG at the same developmental stage. RARA was ubiquitously expressed across the uterine LE, GE, and stromal cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C), whereas RARG exhibited strong nuclear staining in LE cells, with lower expression in the stroma and GE cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and E). Both receptors showed minimal expression in the myometrium (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 F and G). Due to the challenges with available commercial antibodies against RARB, RNAscope in situ hybridization was performed instead to detect its transcript. This sensitive method revealed that Rarb mRNA levels were below the detection threshold in the uterus, despite its robust expression in the vaginal epithelium (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 H and I).

Given the potential off-target effect of RaraDN, it is essential to use a clean genetic model to study RAR signaling during uterine cytodifferentiation. We generated compound mutant mice lacking all three RARs by crossing the L2 alleles (Rarafl/fl; Rarbfl/fl; Rargfl/fl) (29–31) into the Pgr-Cre mouse (32), excising all three Rar genes in PGR-expressing cells, including the FRT. The progeny, designated as triple conditional knockout (tKO) with the genotype Pgr-Cre;Rarafl/fl; Rarbfl/fl; Rargfl/fl, along with littermates containing various combinations of Rar mutations, were subjected to further analyses. The tKO mouse model offers several advantages over the dominant-negative RaraDNPgr model for investigating RAR signaling. First, it specifically disrupts RAR signaling, thereby minimizing potential off-target effects on other pathways, which are more likely with the dominant-negative approach. Second, the tKO model ensures a more complete loss of function of RAR signaling compared to the DN model, whose efficacy in attenuating RAR signaling activity is less certain.

To assess the efficiency of Rar gene deletion with Pgr-Cre, quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay was performed, with primers targeting the LoxP-flanked regions of individual Rar genes. The results confirmed a significant reduction of Rar transcripts as early as PD 10, corroborating the effective deletion mediated by the Pgr-Cre recombinase (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Complete removal of the RAR proteins at PD 20 was further confirmed by IF staining of the RAR proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C).

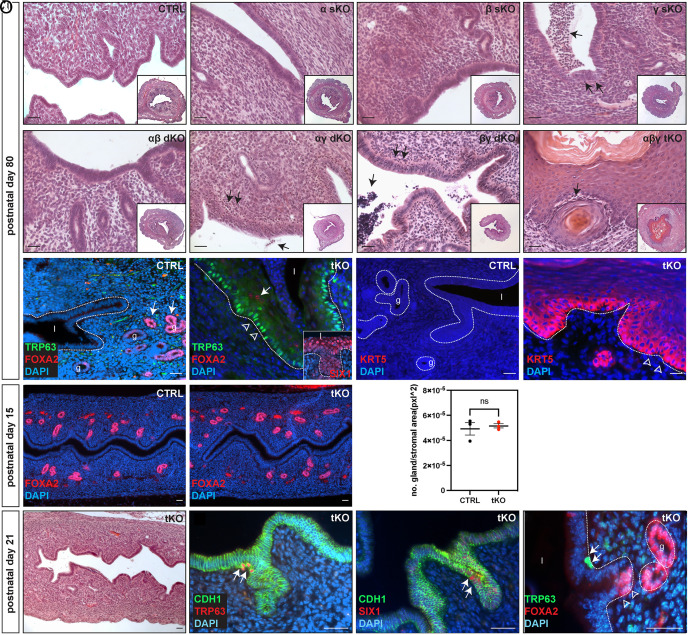

Histological analyses were conducted on young adult female uteri (PD 80) carrying targeted genetic deletions of one, two, or all three Rar genes (Fig. 2 A–H). No discernible structural abnormalities were detected in Rara or Rarb single-knockout (sKO) or Rara and Rarb double-knockout (dKO) mouse uteri (Fig. 2 B, C and E). In contrast, uteri with Rarg deletion, either alone or in combination with Rara or Rarb deletions, displayed signs of immune cell infiltration throughout the uterine stroma, some of which traversed the LE, with an otherwise normal uterine morphology (Fig. 2 D, F and G, arrows). In contrast, tKO uteri displayed a markedly stratified and hypercornified LE, a significantly more dramatic phenotype than that observed in aged RaraDNPgr uteri (Fig. 2H and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 G and H). Similarly, lumps of shed cells, immune cells, and other cellular debris were also observed in the mutant uterine lumen during dissection and upon histological analyses (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 G and H). Immunofluorescent marker analyses indicated that the entire LE of the tKO uterus was lined with stratified epithelial cells expressing TRP63 in the basal layer (Fig. 2J compared to 2I), with some suprabasal cells also positive for FOXA2 (Fig. 2J arrow) or SIX1 (Fig. 2J Inset), suggesting a transdifferentiation toward cervicovaginal-like epithelium. Additionally, Keratin 5 (KRT5), a marker for stratified epithelia, was robustly expressed in the basal layer of the tKO uterine LE, with expression tapering off in cells closer to the lumen (Fig. 2 K and L).

Fig. 2.

RAR signaling is required for maintaining uterine epithelial cell identity. (A–H) H&E staining of PD 80 uterine sections from control (A), Rara, Rarb, or Rarg sKO (B–D), Rara;Rarb, Rara;Rarg, or Rarb;Rarg dKO (E–G) and tKO (H) mice. Insets in A–H show lower-magnification images of the respective genotype. Arrows in D, F–H point to clusters of cells characterized by smaller and more densely staining nuclei, suggestive of immune cell infiltration. (I and J) IF staining for FOXA2 (red) and TRP63 (green) in control (I) and tKO (J) uteri. Epithelia outlined with dotted lines; l, lumen; g, glands. Arrows in I point to FOXA2-positive uterine glands of the control uterus. Arrow and arrowheads in J point to FOXA2-positive suprabasal cells and TRP63-positive basal cells in stratified epithelium of the tKO, respectively. The inset in J shows SIX1 staining (red) of tKO LE, which corresponds to epithelial metaplasia. (K and L) IF staining displays no KRT5 expression in control (K) but strong expression in the basal epithelium of the tKO uterus (L). (M and N) IF staining of FOXA2 displays normal gland development in the tKO at PD 15. (O) Quantification of FOXA2-positive glands at PD15. Six FOXA2-stained uterine sections were examined from each animal (CTRL 4.93E-05 ± 8.61E-06 glands/pxl2 vs. tKO 5.16E-05 ± 2.96-E06 glands/pxl2, P = 0.686, n = 3). (P) H&E staining at PD 21 reveals no apparent morphological changes in the tKO. (Q and R) IF staining reveals sporadic TRP63-positive or SIX1-positive cells (red, arrows in Q and R, respectively) within the simple-columnar tKO uterine epithelium (outlined by CDH1 staining, green). (S) Double IF staining reveals TRP63-positive cells (green, arrows) reside within the LE at the junctional zone between LE and GE as they transition into FOXA2-positive (red, arrowheads) GE cells. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

Classical tissue recombination experiments demonstrated that the uterine epithelial cell fate was determined between PD 5 to 7 by the underlying stroma (18). Given the onset of Cre activity in the uterine epithelium as early as PD 2 and in the stroma by PD 10 in Pgr-Cre mice (32), it is possible that the observed metaplasia event might have resulted from a general failure to specify the uterine LE fate along the length of the entire uterus. If this scenario is true, one would anticipate simultaneous transdifferentiation of extensive segments of the LE into stratified cervicovaginal-like epithelial cells. On the other hand, we observed much reduced yet still detectable RAR proteins and transcripts at PD 10 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A, D–G), suggesting some functional RAR signaling may still be present at this time. Such observation raises the possibility that initial uterine LE cell-fate in the tKO is determined correctly, but subsequent cell-fate maintenance is affected by loss of RAR signaling. To differentiate these possibilities, we examined younger tKO mutant uteri. PD 15 mutant tKO uteri maintained a simple columnar epithelium with normal number of FOXA2-positive glands developed (Fig. 2 M–O and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B). However, as early as PD 21, despite the LE maintaining its simple columnar structure (Fig. 2P and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D), a subset of cells within the tKO uterine LE began to express basal markers TRP63 and SIX1 (Fig. 2 Q and R, arrows). Notably, while these TRP63-positive cells were found along the length of A–P axis, they were predominantly localized at the junctions between the LE and the newly emerging GE, a region where the proposed uterine stem/progenitor cell population resides (33). Double staining of TRP63 and FOXA2 confirmed that TRP63-positive cells were situated within the LE at invagination sites leading into the underlying mesenchyme, immediately prior to the onset of FOXA2 expression (Fig. 2S, arrowheads). These results align with the hypothesis that the observed mutant LE metaplasia phenotype does not originate from a developmental failure to correctly specify uterine LE cell fate but rather from a failure to maintain established uterine cell fate. In this scenario, a subset of uterine stem/progenitor cells could have adopted a stratified epithelial cell fate as a result of RAR signaling loss, which subsequently outcompete and replace the original uterine LE population. Collectively, these data demonstrated that RAR signaling plays an indispensable role in preserving adult uterine epithelial cell identity, whose loss initiates a complete transdifferentiation of the uterine epithelium into cervicovaginal-like epithelium.

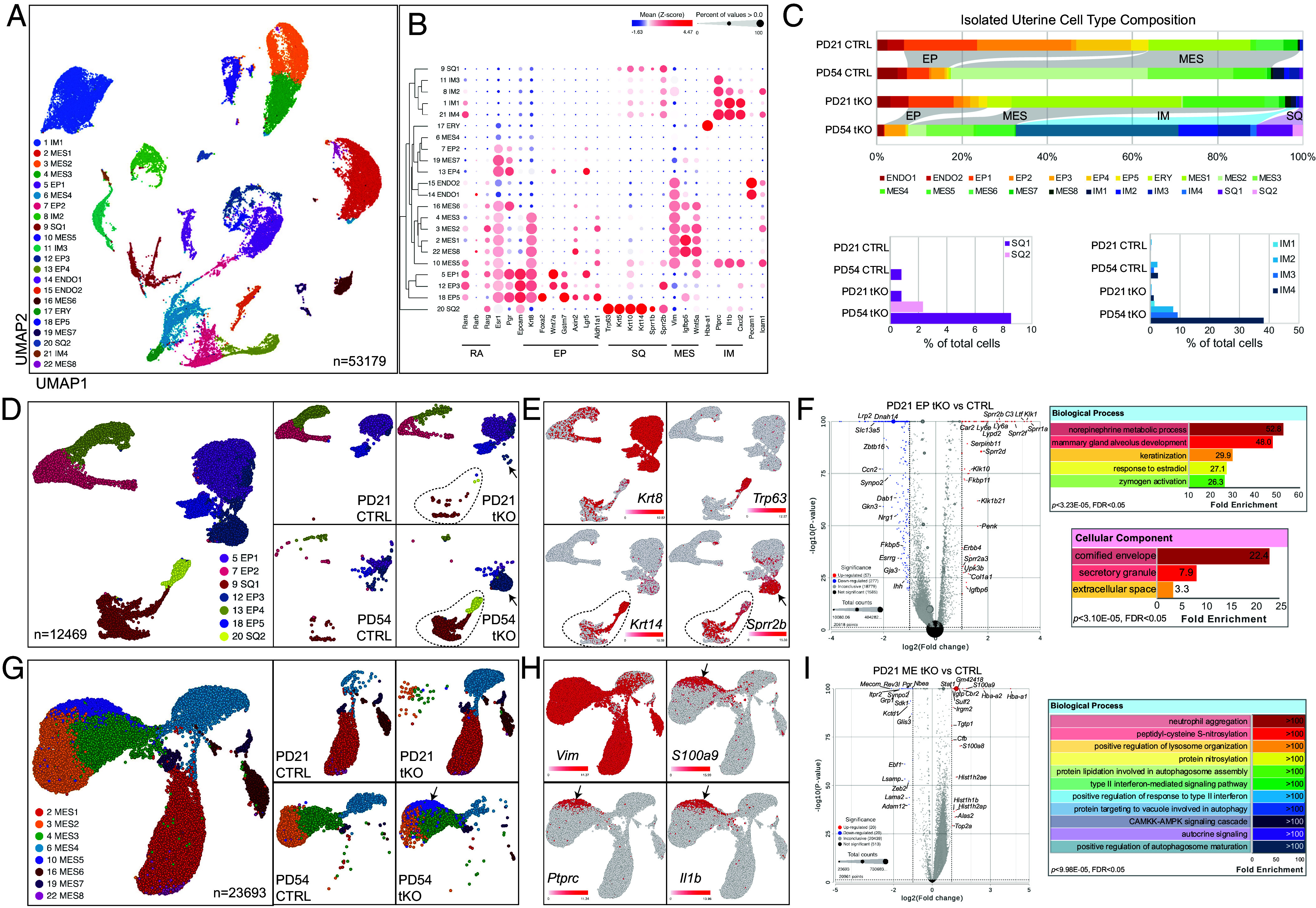

Comprehensive Cellular Landscape of tKO Uterine Cells Revealed by scRNAseq.

If our stem/progenitor cell model is correct, we would expect that the TP63+/SIX1+ cell population should increase in number as a function of time to generate other cervicovaginal-like epithelial populations. To test this hypothesis and to comprehensively characterize the transformed cell types in tKO mutant uteri, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) on uterine cells enzymatically dissociated from either tKO or wild-type female mice (3 each). This analysis was conducted at two developmental stages: PD 21, when TRP63+/SIX1+ cell starts to emerge but precedes any observable morphological alterations (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D); and PD 54, when patches of epithelial metaplasia are apparent (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E and F). We sequenced between 7,813 and 22,932 cells per biological group, totaling 53,179 cells, which we analyzed using Partek™ Flow™ software, version 11.0. (34) Integrative analysis of the data from the four biological conditions identified twenty-two transcriptionally distinct clusters (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Table S1). We determined the cell types of individual clusters using the CellKb annotation tool (www.cellkb.com, version 2.7), applying a rank-based method to align biomarkers of each cluster with canonical cellular signatures from the literature (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Dataset S1). The identified clusters included typical cell types found in murine uteri at these stages, including simple columnar epithelial (EP), mesenchymal (MES), endothelial (ENDO), immune cells (IM), and erythrocytes (ERY, Fig. 3B). Notably, two clusters of squamous epithelial cells (SQ) were present almost exclusively in the tKO samples at both time points (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Table S1). Cell type composition analyses revealed an extensive expansion of the IM clusters and the SQ clusters in the tKO over time (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Table S1), consistent with the observed phenotype.

Fig. 3.

Delineating cellular profiles of tKO uterine cells by scRNAseq. (A) UMAPs of the 22 graph-based clusters of all sequenced cells. (B) Bubble map of selected marker expression in the 22 clusters. RA, retinoic acid-related; scEP simple columnar epithelium; ssEP, stratified squamous epithelium; MES, mesenchym; IM, immune. (C) Cell composition of isolated uterine cells of each biological sample. (D) UMAP of epithelial clusters and that of individual samples. Dotted lines outline squamous clusters and arrows point to cluster 18. (E) Expression of indicated markers by different epithelial clusters. (F) Volcano plot of genes expressed in epithelial clusters of PD 21 samples and GO analyses of the DRGs. (G) UMAP of mesenchymal clusters and that of individual samples. The arrow points to cluster 10. (H) Expression of indicated markers by different mesenchymal clusters. (I) Volcano plot of genes expressed in mesenchymal clusters of PD 21 samples and GO analyses of the DRGs.

To gain further insights into the molecular and cellular changes in a cell-type-specific manner, we extracted epithelial clusters, including both EP and SQ cells, and reran the analysis (Fig. 3D). Reclustering revealed stratification within the simple columnar epithelial cells into Krt8high (EP1, EP3, and EP5) and Krt8low (EP2 and EP4) populations (Fig. 3E), all expressing high levels of Esr1 and Pgr (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Within the Krt8high simple columnar epithelial clusters, EP5 cells expressed high level of Foxa2, hence are GE cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). The two SQ clusters, closely related transcriptionally, differed significantly in their composition over time. SQ2, exclusive to the tKO uteri, comprised a minor fraction of the cell population at both PD 21 and PD 54 (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Table S1) and was characterized by the expression of basal squamous epithelial markers such as Trp63, Pitx1, Krt5, and Krt14 (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). In contrast, SQ1 cells, though sparsely present in control samples, constituted 0.33% and 8.54% of the tKO uterine cell population at PD 21 and PD 54, respectively (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Table S1). These cells expressed lower or absent levels of Trp63 and Pitx1, and diminishing levels of Krt5 and Krt14 as they differentiate (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). They also showed increasing expression of markers for suprabasal cells (Krt1) and cornified cells (Sprr2b) (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) suggesting a more differentiated squamous epithelial phenotype. Intriguingly, Sprr2b was also detected in the simple columnar epithelial cluster EP3, primarily in PD 54 tKO samples (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these findings suggest that SQ2 cells exhibit stem-like/progenitor characteristics, while SQ1 cells represent a more differentiated squamous epithelial phenotype.

To probe into the origin of SQ2 cells, we conducted cell lineage and pseudotime trajectory inference analysis using the Monocle 3 suite in Partek Flow on the PD 21 tKO sample, when SQ2 cells first began to emerge. A main trajectory was identified, with emerging SQ2 cells embedded within the Krt8high EP1, EP3, and EP5 clusters (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). This cell cluster exhibited high expression levels of genes previously identified as uterine epithelial stem cell markers, including Axin2, Lgr5, Aldh1a1, and Gstm7 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C) (35–39). Closer examination revealed that these clusters expressed increasing levels of the vaginal marker Trp63 and the cornification marker Sprr2b, alongside a decreasing level of the stem cell marker Gstm7 over pseudotime (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 D–G). These findings suggest that SQ2 progenitor squamous epithelial cells originate from epithelial tissue and are likely close descendants of the proposed uterine epithelial stem cells.

Differential gene expression analysis, comparing scRNAseq data of all epithelial cells from PD 21 tKO with control samples, identified 57 upregulated and 277 downregulated genes (Log2 fold change >2, P-value < 0.05, Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Table S3). Gene ontology analysis of the differentially regulated genes (DRGs) highlighted enrichment in pathways related to the norepinephrine metabolic process, keratinization, and response to E2, among others (Fig. 3F). Several up-regulated DRGs including Sprr1a, Klk1, Klk10, Ltf, and Ly6a, exhibited significant increases specifically in the Krt8high LE cluster EP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–E). This upregulation persisted in the LE EP3 cluster and the SQ clusters at PD 54 in the tKO samples for all genes except Klk1, which was nearly absent in all adult EP cells regardless of genotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–E). Conversely, the most prominently downregulated DRGs, including Lrp2, Kcnb2, and Frmd5, were initially highly expressed in nearly all simple columnar epithelial clusters of the PD 21 CTRL sample (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 F–H). Their expression was downregulated in the PD 21 tKO sample and became nearly undetectable by PD54 in samples of both genotypes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 F–H).

Similar reclustering and differential gene expression analyses were performed on all MES clusters, comparing PD 21 CTRL and tKO samples (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Table S3). A high level of Vimentin (Vim) was detected across all MES clusters (Fig. 3H). GO analysis of PD 21 MES DRGs indicated significant enrichment in pathways associated with neutrophil aggregation, interferon-mediated signaling, and autophagy-related processes (Fig. 3I and SI Appendix, Table S3). Intriguingly, a unique mesenchymal cluster (MES5), comprised predominantly of cells from tKO samples, expanded over time (Fig. 3G arrow, SI Appendix, Table S2). These mesenchymal cells expressed high levels of immune-related genes such as S100a9, Ptprc (CD45), and Il1b (Fig. 3H), suggesting their potential role in the immune cell infiltration phenotype observed in the tKO uterus.

Inflammatory Response and Immune Cell Infiltration in Absence of RA Signaling.

Our scRNAseq data revealed a dramatic increase of immune cell populations in the tKO uteri over time (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Table S2). A closer look at all Ptprc+ cells revealed that they resembled neutrophils (IM1, S100a8high), macrophages (IM2, Adgre1high), and T cells (IM3 and IM4, Cd3dhigh) based on expression of canonical marker genes (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Immune cell infiltration in RAR-deficient uteri. (A) UMAPs of immune clusters from scRNAseq with marker expression and quantitative RT-PCR of indicated genes comparing PD 80 control and tKO uterine tissues. Error bars represent mean with SD. (B–D) IF staining revealed very few LY6G-positive neutrophils in the control stroma (B) and influx of neutrophils to the LE of βγ dKO (C). Neutrophils continued to be present in the unstratified tKO epithelia (D). (E–G) IF staining identified sporadic F4/80-positive macrophages in control (E) and pronounced macrophage infiltration in both βγ dKO (F) and tKO (G) uteri. (H–J) IF staining of macrophage subtype markers CD86 (H), ARG1 (I), and CD206 (J) in βγ dKO uteri. (K–P) IF staining of F4/80 (K and N), ARG1 (L and O), and CD206 (M and P) in PD 10 control (K–M) and tKO (N–P) uteri reveals presence of macrophages in the tKO uteri, preceding epithelial changes. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

Upregulation of several interleukin- and chemokine-related genes (Il1a, Il1b, Itgam, S100a8, S100a9, Cxcl2) in the tKO model was validated through quantitative RT-PCR, using RNA isolated from whole uteri of indicated genotypes at PD 80 (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Given that scRNAseq results revealed a marked increase in neutrophil and macrophage populations over time, we sought to corroborate this observation with marker staining. While neither Rarg single- nor double-knockout mutants exhibited epithelial stratification, both displayed immune cell infiltration (Fig. 2 D, F and G). Therefore, a Rarb/Rarg double KO (βγ dKO) was used as an intermediate control to better understand these cellular dynamics. IF staining demonstrated few sporadically distributed LY6G-positive neutrophils and F4/80-positive macrophages in control uteri, primarily within the stroma (Fig. 4 B and E). In contrast, a pronounced infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages was evident in the dKO uteri, with neutrophils residing primarily in the LE (Fig. 4C) and macrophages spanning both stromal and LE layers (Fig. 4F). Following extensive epithelial transdifferentiation into cervicovaginal-like epithelium in the tKO uteri, neutrophil presence was predominantly observed in the unstratified GE (Fig. 4D) and macrophage in the stroma (Fig. 4G). To determine the type of infiltrating macrophages, IF was performed with antibodies against markers indicative of M1 (CD86) and M2 macrophages (ARG1 and CD206). IF staining showed that M2 but not M1 macrophages were present in the mutant, with CD206+ M2 cells residing in the stroma and ARG1+ M2 cells localized to the epithelium (Fig. 4 H–J). The distinction between these M2 macrophage subpopulations and the regulatory mechanisms governing their marker expression during epithelial transition remain elusive at present. Furthermore, it is unclear whether there is a causal link between immune cell infiltration and epithelial metaplasia, or if these are two independent events. Nevertheless, marker staining on younger specimens demonstrated that increased number of F4/80- and CD206-positive M2 macrophages were present in the tKO uterine stroma as early as PD 10, preceding any morphological alterations (Fig. 4 K–P).

Interplay between RAR and ER Signaling in Uterine Epithelial Fate Maintenance.

Given that our differential gene expression analysis on PD 21 epithelial clusters identified ER signaling as one of the top-enriched pathways (Fig. 3F) and considering the critical role of ER signaling in uterine homeostasis, we conducted further investigations into this pathway. By cross-referencing our PD 21 epithelial cluster DRG list with a published transcriptomic study that identified transcriptional targets of E2 in ovariectomized mice treated with either vehicle or E2 (40), we determined that 134 of the 334 epithelial DRGs are also known E2 targets. More importantly, expression of the majority of these genes exhibited concordant regulatory trends. This represents a dramatic statistical enrichment over what would be expected by random chance, as confirmed by the chi-square test (SI Appendix, Table S3). Furthermore, our previous microarray analysis of uterine epithelial and stromal tissues in a neonatal diethylstilbestrol (DES, a strong synthetic estrogen) model, suggested a significant overlap between RA targets and genes affected by exogenous estrogen exposure (41). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis corroborated a pronounced downregulation of RAR signaling pathway activity in neonatal uteri by DES treatment, evidenced by decreased expression of Stra6 and Hsd11b2, predominantly within the uterine epithelium (Fig. 5A). This downregulation of RAR signaling in response to estrogen induction occurred concomitantly with the upregulation of interleukin-associated genes including Il1a (Fig. 5A) and many well-documented transcriptional targets of ER signaling (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Neonatal DES treatment also elicited rapid macrophage infiltration phenotype similar to that observed in the tKO uteri (Fig. 5 B and C). Interestingly, this phenotype persisted long after the treatment had ended. Abundant F4/80-positive macrophages and LY6G-positive neutrophils were detected in the uteri of 5-mo mice treated with DES from PD 1 to 5, along with notable stratification of the uterine epithelium at this later stage (Fig. 5 D and E).

Fig. 5.

Antagonism between RA and ER signaling pathways dictates adult uterine epithelium fate. (A) Real-time RT-PCR of RAR signaling readout genes Stra6 and Hsd11b2 and Interleukin-associated gene Il1a in PD 5 uterine epithelium (UE) and uterine mesenchyme (UM), from mice treated daily with oil or DES. Error bars represent mean with SD. P-values are presented on top of each pair of comparison. ns, not significant. (B and C) IF staining of epithelial marker CDH1 (green) and macrophage marker F4/80 (red) reveals macrophage infiltration in DES-treated uterus at PD 5. (D and E) LY6G and F4/80 IF staining of 5-mo uteri showing persistence of neutrophil and macrophage infiltration in mice treated postnatally with DES (E). Arrows and arrowheads point to macrophages residing in the epithelium and stroma, respectively. (F and G) H&E staining at PD 60 illustrates that weekly fulvestrant retains simple columnar morphology in tKO uteri (insets showing high-magnification images of the boxed regions). (H and I) Robust KRT5 expression in stratified tKO uteri (H) is not seen in fulvestrant-treated counterparts (I). (J and K) IF staining of CDH1 (green) and F4/80 (red) shows significantly reduced macrophage infiltration in the tKO treated with fulvestrant (K) when compared to nontreated counterpart (J). (L) Quantitative RT-PCR results demonstrate restoration of genes associated with stratification, immune cell infiltration, and cornification that are aberrantly up-regulated in the tKO by fulvestrant treatment. Error bars represent mean with SD.

These observations suggest a model in which antagonism between RAR and ER signaling pathways plays a pivotal role in modulating uterine epithelial cell fate. Under physiological conditions, strong RAR signaling balances that of ER to maintain the uterine epithelium as simple columnar cells. However, when RAR signaling is compromised or when ER signaling is augmented supraphysiologically, as observed in the tKO and DES models respectively, the uterine epithelium exhibits characteristics akin to cervicovaginal epithelium. If true, this model would predict that attenuating ER signaling in Rar tKO mice may reestablish this equilibrium and prevent the simple columnar uterine LE from stratification. To test this hypothesis, we administered fulvestrant (a.k.a. ICI 182780), an efficacious ER antagonist, to tKO females weekly from PD 7. At PD 60, while the tKO LE displayed large regions of stratification with strong KRT5 staining (Fig. 5 F and H), the LE of fulvestrant-treated tKO littermates remained simple columnar with no KRT5 expression (n = 3, Fig. 5 G and I). This remarkable phenotypic rescue was accompanied by a marked reduction in macrophage infiltration (Fig. 5 J and K) and a restoration of gene expression profiles including markers for stratification (Trp63, Krt5, Krt14), immune cell infiltration (S100a9 and Cxcl2), and cornification (Sprr2d) toward those of wild-type controls (Fig. 5L). To rule out the possibility that fulvestrant might interfere with uterine patterning, the rescue experiment was subsequently repeated in tKO mice with treatment initiated at PD 15, a time when LE specification has long finished and uterine homeostasis is well underway. Similar histological outcomes were observed in these fulvestrant-treated tKO at PD 60, with the LE maintaining a simple columnar structure in treated animals (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Collectively, these rescue experiments provide compelling evidence supporting the model in which interplay between RAR and ER signaling cascades is instrumental in cell-fate determination of the adult uterine LE.

Cell-Autonomous Role of RAR Signaling to Maintain LE Fate.

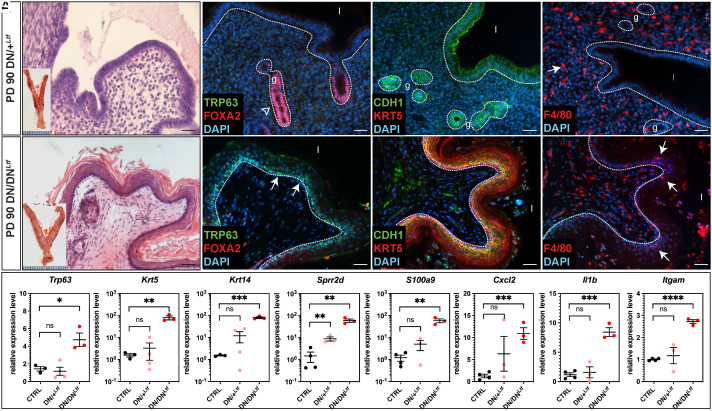

To determine the tissue-specific requirement for RAR signaling in maintaining LE fate, we utilized the Ltf-iCre driver to selectively express either one or two alleles of the dominant-negative receptor RaraDN in the LE to achieve varying degree of RAR signal disruption (42). Young mice carrying a single allele (referred to as DN/+Ltf) maintained fertility and showed normal uterine morphology (Fig. 6A). This suggests that the fertility impairment observed in RaraDNPgr mice is not caused by disrupted RA signaling within the LE.

Fig. 6.

LE-specific disruption of RAR signaling leads to LE metaplasia. (A and B) H&E staining of PD 90 DN/+Ltf and DN/DNLtf uteri. Insets show gross morphology of the entire FRTs upon dissection, note that the uterine horns are visually thicker. (C and D) IF staining of basal marker TRP63 (green, arrows) and uterine gland marker FOXA2 (red, open arrow). Epithelia outlined with dotted lines; l, lumen; g, glands. (E and F) IF staining of epithelial marker CDH1 (green) and stratified epithelial marker KRT5 (red). (G and H) IF staining of macrophage marker F4/80 (red, arrows). Note that there is macrophage infiltration into the stratified epithelium of the DN/DNLtf uteri (H, arrows). (I) Quantitative RT-PCR of indicated genes comparing PD 90 control (CTRL), DN/+Ltf, and DN/DNLtf uterine tissues. Error bars represent mean with SD.

In stark contrast, females with two RaraDN alleles (DN/DNLtf) exhibited nearly complete uterine LE metaplasia by 3 mo (Fig. 6B). IF staining demonstrated elevated expression of stratified squamous epithelial markers TRP63 and KRT5 in the DN/DNLtf uterine LE (Fig. 6 D and F), which were not detected in control and DN/+Ltf uteri (Fig. 2I and Fig. 6C). CDH1 IF staining revealed that DN/+Ltf uterine lumen retained a simple-columnar epithelium (Fig. 6E), whereas the DN/DNLtf uterus transitioned to a stratified epithelium (Fig. 6F).

Despite the morphological similarities between the DN/DNLtf and tKO uteri, the former did not exhibit significant immune cell infiltration as observed in the tKO mice. H&E staining showed no apparent immune cell presence in the DN/DNLtf uterine stroma or lumen (Fig. 6B), with macrophage numbers (Fig. 6H) similar to those of the DN/+Ltf (Fig. 6G) and control mice (Fig. 4E), contrary to the massive number of macrophages in tKO uteri (Fig. 4G). Real-time RT-PCR confirmed the significant upregulation in the expression of markers for stratification (Trp63, Krt5, Krt14) and cornification (Sprr2d) in the DN/DNLtf uteri, and revealed that despite lack of phenotypical immune cell infiltration, many chemokine-related genes (S100a9, Cxcl2, Il1b, and Itgam) are up-regulated in the DN/DNLtf uteri (Fig. 6I). DN/+Ltf showed normal expression of all assayed genes except for elevated level of Sprr2d (Fig. 6I). These data, taken together, are consistent with the notion that a cell-autonomous role of RAR signaling within the LE is essential to maintain adult LE homeostasis. Further investigation using the Ltf-iCre to eliminate all Rar receptors is warranted to confirm these findings.

Discussion

Several studies have previously suggested a decreasing gradient of RAR signaling activity along the A-P axis of the Müllerian ducts (43–45). Organ-cultured neonatal mouse Müllerian ducts, when exposed to exogenous RA or RA antagonists, differentiate into uterine- or vaginal-like structures respectively, indicating the crucial role of RAR signaling in initial FRT cell-fate determination (45). Furthermore, gene profiling of epithelial organoids from wild-type and Smad2/3 dKO uteri suggested that RAR signaling is involved in maintaining the adult epithelial progenitor cell state (46). In the present study, we provided compelling genetic evidence that RAR signaling is required to maintain adult uterine epithelial homeostasis, principally through antagonizing ER signaling.

The RAR signaling cascade is primarily mediated by RAR/RXR heterodimers that bind to RAREs within the genomic DNA, which then activate transcription of genes critical for cell differentiation, apoptosis, and metabolic pathways [for review (23)]. Our study leverages the Pgr-cre driver, which is active postnatally in the uterus, to disrupt RAR signaling through targeted genetic manipulations — either by excising all three Rar genes or by activating a dominant-negative RARA variant. While these manipulations did not alter initial uterine patterning or adenogenesis, age-dependent epithelial metaplasia was observed, manifesting within 2 mo in the tKO model and around 1 y in the RaraDNPgr mice. This temporal variation likely reflects the differing impacts of these models on RAR signaling: the tKO model completely disrupts the signaling cascade by removing all functional RAR receptors in cre-positive cells, effectively nullifying both activating and repressive effects, while the dominant negative receptor in the RaraDNPgr model impairs activating effects but preserved the repressive effect of RARA. It is noteworthy that the metaplastic uterine epithelia observed in both models not only morphologically resemble vaginal epithelia, but also show physiological similarities. The shedding of suprabasal and cornified layers, along with immune cells into the uterine lumen, was observed, likely as a response to hormonal changes during the estrus cycle. Moreover, the aforementioned age-dependent changes align with the well-documented effects of vitamin A deficiency on uterine metaplasia, where the persistent association with corepressors, due to lack of RA, presumably maintains a repressive state. These findings illustrate that localized disruptions in RAR signaling within the female reproductive organs, rather than a systemic ligand deficiency, is the leading cause to induce metaplasia, and underscore the critical role of activating effects of RAR signaling in maintaining uterine epithelial identity.

ScRNAseq has emerged as a robust method to unravel cellular heterogeneity within tissues. Our scRNAseq analysis elucidated the developmental trajectory and expansion of squamous epithelial cells in tKO uteri over time, offering profound insights into epithelial cell dynamics under RAR signaling and during its disruption. Notably, we identified two distinct clusters of squamous epithelial cells: SQ1 and SQ2. SQ2, representing a minor fraction of the isolated uterine cells, was absent in control samples and exhibited high transcript levels of canonical basal squamous cell markers, suggesting their potential identity as the early-stage progenitor cells in squamous epithelial development. In contrast, SQ1, more prevalent, displayed progressive expansion and predominantly expressed genes associated with suprabasal and cornified layers of squamous epithelia, en route to differentiation toward mature squamous epithelial cells.

Immunofluorescent staining identified sporadic TRP63+ or SIX1+ cells within the PD 20 tKO LE, notably at the neck region of invaginating glands, a site proposed as a spatial niche for uterine epithelial stem cells (33). This finding suggests that RAR signaling may play a crucial role in maintaining the identity of these cells or its immediate descendants. Disruption of RAR signaling appears to reprogram these cells or their immediate descendants toward a vaginal-like stem/progenitor cell-fate, initiating their differentiation into stratified squamous epithelial cells that eventually predominate throughout the uterine lining. We hypothesize that this transdifferentiation originates from changes in uterine stem/progenitor cells, likely through generation of cervicovaginal-fated transient amplifying populations, but not from mature uterine epithelial cells. The hypothesis was supported by the trajectory inference analysis, where we observed that SQ2 squamous progenitor cells are embedded within the stem-like simple columnar epithelial cell clusters and are likely close descendants of Gstm7+ uterine epithelial stem cells. Consistently in our DN/DNLtf model, which specifically perturbs RAR signaling in LE cells, extensive uterine LE metaplasia was observed. This underscores the pivotal role of RAR signaling in a cell-autonomous manner in maintaining adult LE homeostasis. Collectively, these data demonstrate that RAR signaling dynamically regulates uterine epithelial cell fate in adulthood.

The pronounced expansion of immune cell populations — neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells — exclusively observed in the tKO model aligns with the transdifferentiation of the uterine epithelium into a vaginal-like epithelium. This transdifferentiation is further characterized by a marked upregulation of proinflammatory markers such as Il1b and its receptor Il1r2, coupled with a substantial infiltration of leukocytes. These changes suggest a shift toward a proinflammatory environment in the tKO uterus, akin to that of the adult vagina. Intriguingly, despite the extensive LE metaplasia observed in the DN/DNLtf model, such immune response phenotype was absent. This suggests that the immune response may not actively lead to the morphological alterations associated with RAR signaling deficiency. Nevertheless, the inflammatory response observed here parallels findings that estrogen signaling is crucial in the recruitment and maintenance of leukocytes within the uterus (47), underscoring an intricate interplay between RAR and ER signaling pathways. Surprisingly, both SQ clusters and a mesenchymal cluster (MES5), unique to the tKO, also express various immunoglobulin genes, typically associated with B cells and antibody production. This unexpected finding of immunoglobulin transcripts presence in nonimmune cell clusters is unusual and intriguing, suggesting a potential aspect of uterine cell function in immune response and warrants further investigation.

The differential gene expression profiles uncovered by our scRNAseq, which are significantly enriched in genes previously shown to be transcriptional targets of ER (40), prompted us to hypothesize the existence of an antagonistic relationship between ER and RAR signaling pathways. This hypothesis was tested in two animal models in vivo: 1. In the neonatal DES model, where newborn mice received daily dose of synthetic estrogen, we found a significant downregulation of RAR signaling pathway readout genes, particularly in the uterine epithelium, indicating that ER activation directly suppresses the RAR signaling cascade; 2. In the Rar tKO model, treatment with the ER antagonist fulvestrant effectively prevented stratification of the mutant uterine epithelia and a suppression of leukocyte influx, suggesting that balancing ER and RAR signaling is crucial in maintaining epithelial cell identity and regulating the immune landscape within the uterine environment. Our antagonistic model between RAR and ER signaling provides a coherent framework for understanding DES-induced toxicity upon FRTs. DES, as a potent synthetic estrogen, exacerbates ER signaling, potentially overwhelming the regulatory effects of RAR signaling on cellular differentiation and proliferation. This imbalance can lead to excessive cellular proliferation and a deviation from normal epithelial cell development, contributing to the uterine metaplasia and adenocarcinoma phenotype observed later in life of DES-exposed females. Recently Rizo et al. demonstrated that loss of Esr1 led to multilayered stratified squamous epithelium in mouse endometrial epithelial organoids, deviating from the typical single-layer columnar epithelium (48). On the other hand, the role of Esr1 in Müllerian duct LE-specification appear to be cell-type specific in vivo. In either Esr1−/− or Pgr-cre; Esr1f/f uteri, no stratification was observed (48). When Esr1 was removed in the LE and GE using Wnt7a-Cre, simple columnar uterine LE and GE were observed with some cells expressing ectopic FOXA2 and KRT5. In contrast, when Esr1 was abolished in mature GE using Foxa2-cre, stratification occurred only in the GE. These experimental results highlight a complex cell type–specific requirement for ESR1 in uterine fate specification and maintenance.

A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-chip study in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line provided a potential molecular basis for RAR-ER antagonism proposed herein (49). In ESR1-positive human breast cancers, RAR signaling inhibits cancer cell growth and induces apoptosis, whereas ER signaling promotes proliferation and survival. The genome-wide ChIP-chip analysis revealed extensive colocalization of ESR1- and RAR-binding sites, with the two receptors mediating opposite gene expression regulation on shared transcriptional targets through competitive binding (49). Further exploration through single-cell ChIP-sequencing using ER- and RAR-specific antibodies in wild-type and tKO uterine cells at various developmental stages may offer additional insights into gene regulation of the two intertwining pathways, and deepen our understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms within the context of the endometrium.

Taken together, our study revealed an antagonistic relationship between RAR and ER signaling pathways in adult uterine epithelium, thereby ensuring the preservation of the simple columnar morphology. Our data show that disruption of RAR signaling induces a transformation of the uterine epithelium toward a stratified cervicovaginal phenotype accompanied by cellular and immunological disturbances, highlighting the critical balance orchestrated by RAR and ER pathways in uterine homeostasis. This research lays the groundwork for future studies, including the development of treatments aimed at reestablishing the RAR-ER signaling equilibrium in disorders of the FRT and potentially broadening the impact of these findings to explore epithelial cell-fate determination in other organ systems.

Methods

Mice.

The generation of mice carrying the L2 alleles of all three Rar genes was previously described (29–31) and kindly provided by Dr. Joo-Seop Park. The Pgr-Cre line (32), obtained from Drs. Francesco DeMayo (the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) and John Lydon (Baylor College of Medicine), was crossed with mice homozygous for the floxed alleles of Rara, Rarb, and Rarg (triple-floxed mice) to produce offspring carrying Pgr-Cre alongside all three heterozygous floxed alleles. Backcrossing of F1 progeny and triple-floxed mice yielded males with the genotype Pgr-cre; Rarafl/fl; Rarbfl/fl; Rargfl/fl (tKO studs), which were subsequently bred with triple-floxed females to generate tKO females and their littermate controls. This backcrossing also produced various combinations of single knockout (sKO) and double knockout (dKO) mice. The generation of RaraDNPgr mice has been described previously (28). RaraDNfl/fl mice were crossed to Ltf-iCre (generous gift from Dr. Demayo) to generate RaraDNfl/+; Ltf-iCre male offspring, which were subsequently bred to RaraDNfl/fl females to generate RaraDNfl/+; Ltf-iCre (DN/+Ltf) and RaraDNfl/fl; Ltf-iCre (DN/DNLtf) females used in this study. For DES treatment, neonate female pups received daily subcutaneous injection of 20 μL corn oil or DES (1 mg/kg B.W.) from PD 1 to PD 5, and killed 6 h after the last injection (41). For fulvestrant treatment, PD 7 or PD 15 tKO female pups received weekly subcutaneous injections of fulvestrant (5% DMSO/95% corn oil at 25 mg/Kg B.W. (50)or vehicle and killed at PD 60. All experimental mice were maintained in a barrier facility at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, with strict adherence to institutional animal care guidelines under an approved protocol.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time RT-PCR.

RNA from uterine tissues was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems Inc., ABI). Quantitative PCR analyses were performed on the QuantStudio5 Real-Time PCR System (ABI) using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (ABI) and gene-specific primers (SI Appendix, Table S4). Each experimental condition was tested in three biological replicates unless otherwise specified. Relative gene expression changes were quantified using the delta-delta Ct method, with normalization to the housekeeping gene Rpl7.

Histology, IF, and In Situ Hybridization.

Tissues fixed in Bouin fixative were processed for dehydration and embedding at the Developmental Biology Histology Core at Washington University School of Medicine. Eight-micron sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) for histology. IF was performed as previously described using antibodies diluted in blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 3% normal goat serum in PBS) at concentrations listed in SI Appendix, Table S4. In Situ hybridization was performed on PFA-fixed paraffin-embedded 8 µm tissue sections using RNAscope® 2.5 HD Assay-RED kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, ACD, Newark, CA). Predesigned gene-specific double-”Z” oligo probe against Rarb was ordered from ACD (probe-Mm-Rarb) and detailed in situ procedure has been described previously (51).

Uterine Cell Isolation and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing.

Uterine horns were longitudinally incised and segmented into 2 to 3 mm pieces following dissection. These tissue fragments were then enzymatically digested in 15-mL conical tubes containing 1% trypsin in phenol red-, Ca2+-, and Mg2+-free Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Sigma #H6648) at room temperature for 1 h with agitation. To terminate the digestion, an equal volume of fetal bovine serum was added, and the tubes were vigorously shaken to dislodge uterine cells. The supernatant, which contained the dissociated cells, was carefully pipetted out and passed through 70 µm nylon filters to remove debris. The filtered cells were washed twice, collected by low-speed centrifugation, and subsequently resuspended in 0.04% BSA in 1× PBS at a concentration of 1,000 cells/µL, with cell viability exceeding 85%. The cell suspension was then sent to the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University School of Medicine for single-cell RNA sequencing. Detailed description for library construction and sequencing data analysis can be found in SI Appendix.

Statistical Analysis.

All experimental groups contained three biological replicates, if not specified otherwise. Two-tailed Student t test assuming unequal variance was performed to compare means of the experimental groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with raw individual experimental data displayed as dot plots overlay. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Dr. Joo-Seop Park, Francesco DeMayo, and John Lydon for generously providing the mouse lines used in this study. We thank Dr. John McLachlan for helpful discussions and the Genome Technology Access Center at the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University School of Medicine for help with genomic analysis. The Center is partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. This publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. This work was supported by NIH grant HD106120 and R21CA283677 to L. M.

Author contributions

Y.Y. and L.M. designed research; Y.Y., M.H., L.G., S.B., E.S., and V.R.-P. performed research; Y.Y., D.C., and L.M. analyzed data; and Y.Y., M.H., D.C., and L.M. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Sequencing data have been deposited in GEO (GSE282142) (34). All other data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Taylor H. S., Vanden Heuvel G. B., Igarashi P., A conserved Hox axis in the mouse and human female reproductive system: Late establishment and persistent adult expression of the Hoxa cluster genes. Biol. Reprod. 57, 1338–1345 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma L., Benson G. V., Lim H., Dey S. K., Maas R. L., Abdominal B (AbdB) Hoxa genes: Regulation in adult uterus by estrogen and progesterone and repression in mullerian duct by the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES). Dev. Biol. 197, 141–154 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson G. V., et al. , Mechanisms of reduced fertility in Hoxa-10 mutant mice: Uterine homeosis and loss of maternal Hoxa-10 expression. Development 122, 2687–2696 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warot X., Fromental-Ramain C., Fraulob V., Chambon P., Dolle P., Gene dosage-dependent effects of the Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 mutations on morphogenesis of the terminal parts of the digestive and urogenital tracts. Development 124, 4781–4791 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller C., Sassoon D. A., Wnt-7a maintains appropriate uterine patterning during the development of the mouse female reproductive tract. Development 125, 3201–3211 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali A., et al. , Cell lineage tracing identifies hormone-regulated and Wnt-responsive vaginal epithelial stem cells. Cell Rep. 30, 1463–1477.e1467 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goad J., Ko Y. A., Kumar M., Syed S. M., Tanwar P. S., Differential Wnt signaling activity limits epithelial gland development to the anti-mesometrial side of the mouse uterus. Dev. Biol. 423, 138–151 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mericskay M., Kitajewski J., Sassoon D., Wnt5a is required for proper epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the uterus. Development 131, 2061–2072 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelleher A. M., et al. , Forkhead box a2 (FOXA2) is essential for uterine function and fertility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E1018–E1026 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou H. E., Zhang X., Nothnick W. B., Disruption of the TIMP-1 gene product is associated with accelerated endometrial gland formation during early postnatal uterine development. Biol. Reprod. 71, 534–539 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurita T., Cunha G. R., Roles of p63 in differentiation of Mullerian duct epithelial cells. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 948, 9–12 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terakawa J., et al. , FGFR2IIIb-MAPK activity is required for epithelial cell fate decision in the lower mullerian duct. Mol. Endocrinol. 30, 783–795 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terakawa J., et al. , SIX1 cooperates with RUNX1 and SMAD4 in cell fate commitment of Mullerian duct epithelium. Cell Death Differ. 27, 3307–3320 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Couse J. F., Korach K. S., Estrogen receptor null mice: What have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr. Rev. 20, 358–417 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupont S., et al. , Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development 127, 4277–4291 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyagawa S., Iguchi T., Epithelial estrogen receptor 1 intrinsically mediates squamous differentiation in the mouse vagina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 12986–12991 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunha G. R., Stromal induction and specification of morphogenesis and cytodifferentiation of the epithelia of the Mullerian ducts and urogenital sinus during development of the uterus and vagina in mice. J. Exp. Zool. 196, 361–370 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurita T., Cooke P. S., Cunha G. R., Epithelial-stromal tissue interaction in paramesonephric (Mullerian) epithelial differentiation. Dev. Biol. 240, 194–211 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y., Potter S. S., Functional specificity of the Hoxa13 homeobox. Development 128, 3197–3207 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newbold R. R., et al. , Developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol alters uterine gene expression that may be associated with uterine neoplasia later in life. Mol. Carcinog. 46, 783–796 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuminato K., et al. , The role of mesenchymal estrogen receptor 1 in mouse uterus in response to estrogen. Sci. Rep. 13, 12293 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolbach S. B., Howe P. R., Tissue changes following deprivation of fat-soluble A vitamin. J. Exp. Med. 42, 753–777 (1925). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham T. J., Duester G., Mechanisms of retinoic acid signalling and its roles in organ and limb development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 110–123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sucov H. M., et al. , RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 8, 1007–1018 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durston A. J., et al. , Retinoic acid causes an anteroposterior transformation in the developing central nervous system. Nature 340, 140–144 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yip J. E., Kokich V. G., Shepard T. H., The effect of high doses of retinoic acid on prenatal craniofacial development in Macaca nemestrina. Teratology 21, 29–38 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochhar D. M., Limb development in mouse embryos. I. Analysis of teratogenic effects of retinoic acid. Teratology 7, 289–298 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin Y., Haller M. E., Chadchan S. B., Kommagani R., Ma L., Signaling through retinoic acid receptors is essential for mammalian uterine receptivity and decidualization. JCI Insight 6, e150254 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapellier B., et al. , A conditional floxed (loxP-flanked) allele for the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARalpha) gene. Genesis 32, 87–90 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapellier B., et al. , A conditional floxed (loxP-flanked) allele for the retinoic acid receptor beta (RARbeta) gene. Genesis 32, 91–94 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapellier B., et al. , A conditional floxed (loxP-flanked) allele for the retinoic acid receptor gamma (RARgamma) gene. Genesis 32, 95–98 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soyal S. M., et al. , Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 41, 58–66 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin S., Bipotent stem cells support the cyclical regeneration of endometrial epithelium of the murine uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 6848–6857 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Y., Ma L., Data from “Retinoic acid antagonizes estrogen signaling to maintain adult uterine cell fate.” GEO. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE282142. Deposited 18 November 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Syed S. M., et al. , Endometrial Axin2. Cell Stem Cell 26, 64–80.e13 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seishima R., et al. , Neonatal Wnt-dependent Lgr5 positive stem cells are essential for uterine gland development. Nat. Commun. 10, 5378 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomita H., Tanaka K., Tanaka T., Hara A., Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in stem cells and cancer. Oncotarget 7, 11018–11032 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu B., et al. , Reconstructing lineage hierarchies of mouse uterus epithelial development using single-cell analysis. Stem Cell Reports 9, 381–396 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spencer T. E., Lowke M. T., Davenport K. M., Dhakal P., Kelleher A. M., Single-cell insights into epithelial morphogenesis in the neonatal mouse uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2316410120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winuthayanon W., Hewitt S. C., Korach K. S., Uterine epithelial cell estrogen receptor alpha-dependent and -independent genomic profiles that underlie estrogen responses in mice. Biol. Reprod. 91, 110 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin Y., et al. , Neonatal diethylstilbestrol exposure alters the metabolic profile of uterine epithelial cells. Dis. Model Mech. 5, 870–880 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daikoku T., et al. , Lactoferrin-iCre: A new mouse line to study uterine epithelial gene function. Endocrinology 155, 2718–2724 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki A., et al. , Global gene expression in mouse vaginae exposed to diethylstilbestrol at different ages. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 231, 632–640 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki A., et al. , Gene expression change in the Müllerian duct of the mouse fetus exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 232, 503–514 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakajima T., Iguchi T., Sato T., Retinoic acid signaling determines the fate of uterine stroma in the mouse Müllerian duct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14354–14359 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kriseman M. L., et al. , SMAD2/3 signaling in the uterine epithelium controls endometrial cell homeostasis and regeneration. Commun. Biol. 6, 261 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pepe G., et al. , The estrogen-macrophage interplay in the homeostasis of the female reproductive tract. Hum. Reprod. Update 24, 652–672 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizo J. A., Davenport K. M., Winuthayanon W., Spencer T. E., Kelleher A. M., Estrogen receptor alpha regulates uterine epithelial lineage specification and homeostasis. iScience 26, 107568 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hua S., Kittler R., White K. P., Genomic antagonism between retinoic acid and estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Cell 137, 1259–1271 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wardell S. E., et al. , Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of fulvestrant in preclinical models of breast cancer to assess the importance of its estrogen receptor-α degrader activity in antitumor efficacy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 179, 67–77 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin Y., et al. , Heparan sulfate proteoglycan sulfation regulates uterine differentiation and signaling during embryo implantation. Endocrinology 159, 2459–2472 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data have been deposited in GEO (GSE282142) (34). All other data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.