Abstract

Background

The goal of this retrospective cohort study was to analyze the association between benign thyroid alteration and thyroid cancer in patients followed in general practices in Germany.

Methods

Patients aged 18–80 who had received an initial diagnosis of thyroid cancer in one of 1261 general practices in Germany between January 2009 and December 2018 were included in this study (index date). These patients were matched (1:1) to non-cancer patients by age, sex, physician and index year. The main outcome of the study was the association between various benign thyroid alterations and thyroid cancer.

Results

The study included 2787 patients with thyroid cancer and 2787 individuals without cancer (mean age: 52.8 years, 73.5% women). The main finding was that all benign changes in the thyroid with the exception of thyroiditis were associated with thyroid cancer. The strongest association was observed by the nontoxic goiter. Half of the patients with thyroid cancer had nontoxic goiter compared to just one-sixth of the control group. Thyrotoxicosis was found in 12.9% of the cancer group and in 3.9% of the controls. By analyzing TSH in groups, we found an association between suppressed TSH and elevated TSH levels and thyroid cancer.

Conclusion

In accordance with the literature, we confirmed that any kind of benign thyroid alteration was associated with an elevated risk of thyroid cancer. The odds ratio was greatest for nontoxic goiter, followed by benign neoplasms of the thyroid, other disorders of the thyroid such as Hashimoto and thyrotoxicosis. We also found an elevated risk of cancer in patients with either a suppressed or elevated TSH.

Keywords: Thyroid cancer, Goiter, Benign neoplasm

Background

The incidence of thyroid cancer has increased greatly in developed countries over the last 30 years, e.g., in the US, it has risen from 4.9 in 1975 to 14.3 in 2009. Nevertheless, the mortality rate has remained at a low level of approximately 0.5 (Olson et al. 2019). Although the incidence of thyroid cancer has also increased in Germany, due in part to an increase in well-differentiated papillary thyroid cancer, the overall mortality rate has dropped slightly (RKI 2019). There are two different hypotheses that could explain this increase. The first is that the increase is due to better diagnosis, meaning that the increase is simply a statistical increase without any real increase in numbers. The second hypothesis indicates that there is a real increase in numbers. Since the mortality rate has not changed within the observation period, we feel that the second hypothesis is most likely to be true.

There are some known risk factors for developing thyroid cancer including exposure to ionizing radiation, gender, family history, obesity, substance abuse and exposure to flame retardants (Cardis et al. 2005; Han and Kim 2018; Hoffmann et al. 2017; Kitahara et al. 2012; Parker et al. 1974; Ron et al. 1995; Schmid et al. 2015). Of course, we realize that changes within the thyroid itself also affect the development of thyroid cancer (Brito et al. 2014; Staniforth et al. 2016; Welker and Orlov 2003; Yun et al. 2019; Zayed et al. 2015). Until now, however, the question of whether different thyroid lesions lead to thyroid cancer at different rates has not yet been investigated.

The goal of this retrospective cohort study was to analyze the correlation between benign thyroid alterations and the development of thyroid cancer.

Methods

Database

This study was based on data from the Disease Analyzer database (IQVIA). This database contains anonymous information on diagnoses, prescriptions, and demographic data from computer systems used in the practices of general practitioners and specialists (Rathmann et al. 2018). The coverage is approximately 3% of all outpatient offices in Germany. The quality of reported data is monitored regularly by IQVIA. In Germany, the sampling methods used to select physicians’ practices are appropriate for obtaining a representative database of general and specialized practices (Rathmann et al. 2018).

Study population

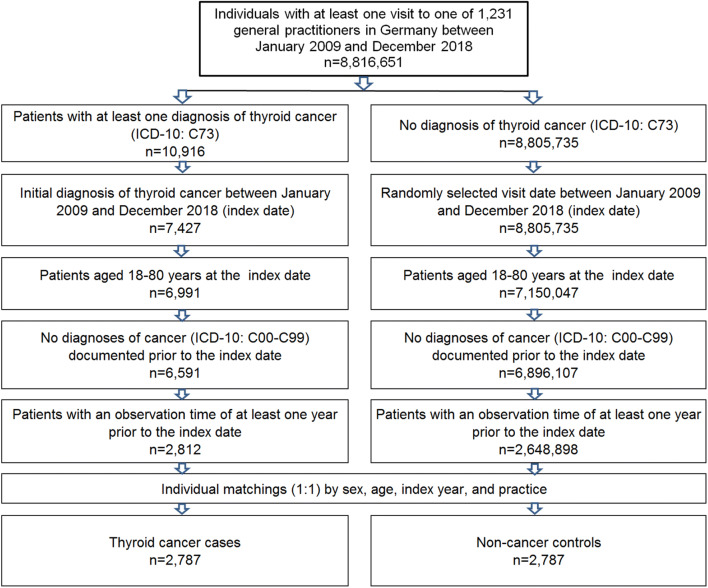

This retrospective case–control study included patients aged 18-80 years with an initial diagnosis of thyroid cancer (ICD-10: C73) in 1,231 general practices in Germany between January 2009 and December 2018 (index date; Fig. 1). One further inclusion criterion was an observation time of at least 12 months prior to the index date. Patients with cancer diagnoses (ICD-10: C00-C99) prior to the index date were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Selection of study patients

Thyroid cancer patients were matched to non-cancer patients by age, sex, physician, and index year. Matching by age was necessary, because the risk of cancer differs with age; matching by sex was necessary as thyroid cancer occurs more often in women than in men; matching by physician was necessary as diagnosis behaviors differ between physicians; finally, matching by index year was necessary to ensure a similar pre-observation time for cases and controls. For the controls, the index date was that of a randomly selected visit between January 2009 and December 2018 (Fig. 1).

Study outcomes and covariates

The main outcome of the study was the association between various thyroid gland diseases and thyroid cancer. All thyroid gland disorders found in at least 0.1% of study patients were included in the analyses. The diagnoses included in the study are listed in Table 1. The mean TSH value was also calculated for each patient based on all documented TSH values prior to the index date.

Table 1.

ICD-10 codes used in the study

| Diagnosis | ICD-10 code |

|---|---|

| Iodine deficiency-related thyroid disorders and allied conditions | E01 |

| Iodine deficiency-related diffuse (endemic) goiter | E01.0 |

| Iodine deficiency-related multinodular (endemic) goiter | E01.1 |

| Iodine deficiency-related (endemic) goiter, unspecified | E01.2 |

| Other iodine deficiency-related thyroid disorders | E01.8 |

| Other hypothyroidism | E03 |

| Other nontoxic goiter | E04 |

| Nontoxic diffuse goiter | E04.0 |

| Nontoxic single thyroid nodule | E04.1 |

| Nontoxic multinodular goiter | E04.2 |

| Other or unspecified specified nontoxic goiter | E04.8, E04.9 |

| Thyrotoxicosis [hyperthyroidism] | E05 |

| Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter | E05.0 |

| Thyrotoxicosis with toxic single thyroid nodule | E05.1 |

| Thyrotoxicosis with toxic multinodular goiter | E05.2 |

| Thyrotoxicosis factitia | E05.4 |

| Other or unspecified thyrotoxicosis | E05.8, E05.9 |

| Thyroiditis | E06 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | E06.3 |

| Other disorders of thyroid | E07 |

| Benign neoplasm of thyroid gland | D34 |

Statistical analyses

Differences in the sample characteristics (age and sex) between those with and those without thyroid cancer were investigated using Chi squared tests for sex and Wilcoxon tests for age. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to study the association between the thyroid gland disorders and the TSH values and thyroid cancer incidence. Three different models were calculated. The first contained the seven main thyroid gland diseases: (1) iodine deficiency-related thyroid disorders and allied conditions, (2) other hypothyroidism, (3) other nontoxic goiter, (4) thyrotoxicosis [hyperthyroidism], (5) thyroiditis, (6) other disorders of thyroid, and (7) benign neoplasm of thyroid gland. The second model contained all detailed diagnoses, while the third included TSH values grouped as < 0.3, 0.3–4.2 (reference value), 4.3–6.0, 6.1–10.0, and > 10.0 units per liter. P values < 0.01 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Basic characteristics of the study sample

The present study included 2787 patients with thyroid cancer and 2787 non-cancer controls. The age and sex structures of the study patients are displayed in Table 2. The mean age [SD] was 52.8 [14.8] years and 73.5% of subjects were women.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study patients after 1:1 matching by age, sex, index year, and physician

| Thyroid cancer patients (%) | Non-cancer patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 2787 | 2787 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 52.8 (14.8) | 52.8 (14.8) |

| Age 18–30 | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| Age 31–40 | 13.0 | 13.0 |

| Age 41–50 | 22.4 | 22.4 |

| Age 51–60 | 24.3 | 24.3 |

| Age 61–70 | 18.3 | 18.3 |

| Age 71–80 | 13.8 | 13.8 |

| Gender: female | 73.5 | 73.5 |

| Gender: male | 26.5 | 26.5 |

Association between thyroid gland disorders and thyroid cancer

Table 3 shows the proportions of patients diagnosed with various thyroid gland disorders and the results of the regression analyses. In total, 50.1% of cases versus 17.2% of controls had nontoxic goiter, 19.1% of cases versus 10.8% of controls had hypothyroidism, 12.9% versus 3.9% had hyperthyroidism, 9.6% versus 5.6% had thyroiditis, 5.6% versus 2.9% had iodine deficiency-related thyroid disorders, and 2.1% versus 0.4% benign neoplasm of thyroid gland. In the first regression model, the strongest association with thyroid cancer was found for nontoxic goiter (OR = 4.85, p < 0.001), followed by benign neoplasm of the thyroid gland (OR = 2.72, p = 0.003), and other disorders of the thyroid (OR = 2.69, p < 0.001). In the second regression model, nontoxic multinodular goiter (OR = 4.60, p < 0.001) had the strongest association with thyroid cancer, followed by nontoxic single thyroid nodule (OR = 3.97, p < 0.001) and unspecified specified nontoxic goiter (OR = 3.97, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between thyroid gland disorders and the incidence of thyroid cancer in general practices in Germany (univariate logistic regression)

| Diagnosis (ICD-10 code) | Thyroid cancer patients (%) | Non-cancer patients (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | ||||

| Iodine deficiency-related thyroid disorders and allied conditions [E01] | 5.6 | 2.9 | 1.87 (1.39–2.51) | < 0.001 |

| Other hypothyroidism [E03] | 19.6 | 10.8 | 1.44 (1.21–1.71) | < 0.001 |

| Other nontoxic goiter [E04] | 50.1 | 17.2 | 4.85 (4.26–5.52) | < 0.001 |

| Thyrotoxicosis [hyperthyroidism] [E05] | 12.9 | 3.9 | 2.65 (2.09–3.67) | < 0.001 |

| Thyroiditis [E06] | 9.6 | 5.6 | 1.02 (0.81–1.30) | 0.831 |

| Other disorders of thyroid [E07] | 6.8 | 2.2 | 2.69 (1.97–3.67) | < 0.001 |

| Benign neoplasm of thyroid gland [D34] | 2.1 | 0.4 | 2.72 (1.40–5.29) | 0.003 |

| Model II | ||||

| Iodine deficiency-related diffuse (endemic) goiter [E01.0] | 2.3 | 1.2 | 1.90 (1.19–3.01) | 0.007 |

| Iodine deficiency-related multinodular (endemic) goiter [E01.1] | 2.0 | 0.7 | 2.53 (1.46–4.39) | 0.001 |

| Iodine deficiency-related (endemic) goiter, unspecified [E01.2] | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.37 (0.79–2.38) | 0.266 |

| Other iodine deficiency-related thyroid disorders and allied conditions [E01.8] | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.13 (0.45–2.85) | 0.794 |

| Nontoxic diffuse goiter [E04.0] | 5.4 | 3.6 | 1.07 (0.80–1.44) | 0.648 |

| Nontoxic single thyroid nodule [E04.1] | 11.8 | 2.7 | 3.97 (3.02–5.20) | < 0.001 |

| Nontoxic multinodular goiter [E04.2] | 13.5 | 2.5 | 4.60 (3.49–6.05) | < 0.001 |

| Other or unspecified specified nontoxic goiter [E04.8, E04.9] | 35.1 | 11.6 | 3.73 (3.20–4.33) | < 0.001 |

| Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter [E05.0] | 3.2 | 1.3 | 1.39 (0.89–2.19) | 0.152 |

| Thyrotoxicosis with toxic single thyroid nodule [E05.1] | 0.8 | 0.2 | 2.22 (0.76–6.45) | 0.144 |

| Thyrotoxicosis with toxic multinodular goiter [E05.2] | 0.9 | 0.1 | 5.97 (1.32–26.92) | 0.020 |

| Thyrotoxicosis factitia [E05.4] | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.44 (0.67–3.07) | 0.347 |

| Other or unspecified thyrotoxicosis [E05.8, E05.9] | 9.7 | 2.6 | 2.92 (2.18–3.90) | < 0.001 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis [E06.3] | 8.9 | 5.2 | 1.05 (0.82–1.34) | 0.703 |

Association between TSH values and thyroid cancer

The mean TSH value was 2.6 (SD: 4.0) in thyroid cancer patients and 1.8 (SD: 1.3) in non-cancer controls. Compared to the reference groups of 0.3–4.2 units per liter, the odds ratio for thyroid cancer was 2.94 (p < 0.001) in the group < 0.3 units per liter, 1.79 (p < 0.001) in 4.3–6.0 units per liter, 4.96 (p < 0.001) in 6.1–10.0 units per liter, and 15.87 in > 10 units per liter (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between mean TSH value and the incidence of thyroid cancer in general practices in Germany (univariate logistic regression)

| TSH value (milli-international units per liter) | Thyroid cancer patients (%) | Non-cancer patients (%) | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (4.0) | 1.8 (1.3) | ||

| < 0.3 | 8.0 | 3.1 | 2.94 (1.98–4.35) | < 0.001 |

| 0.3–4.2 | 77.9 | 91.9 | Reference | < 0.001 |

| 4.3–6.0 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 1.79 (1.16–2.75) | 0.009 |

| 6.1–10.0 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 4.96 (2.32–10.59) | < 0.001 |

| > 10.0 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 15.87 (5.78–43.59) | < 0.001 |

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that there was an association between all benign changes of the thyroid with the exception of thyroiditis and thyroid cancer. The odds ratios differed for the various benign changes, indicating that various benign alterations are associated with the development of thyroid cancer to different extents.

The strongest association was observed by the nontoxic goiter. Thyrotoxicosis, which includes Graves’ Disease, was found in 12.9% of the cancer group and in 3.9% of the controls. Although nontoxic goiter was also the alteration most commonly associated with thyroid cancer in a number of other studies, the proportion varied widely up to 67.9% (Aksoy et al. 2020). Most of the data published on this topic addressed the question of which nodules are malignant and which are benign (Brito et al. 2014; Dean and Gharib 2008; Durante et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2011; Lim et al. 2013; Welker and Orlov 2003; Yun et al. 2019). This might be an important question, since the prevalence of nodules discovered incidentally via ultrasound in the thyroid is between 19 and 67% (Welker and Orlov 2003). Ultrasound is a diagnostic method for thyroid changes that is easy to perform and widely available. Brito et al. demonstrated in a systematic review that ultrasound scans are not accurate enough to predict thyroid cancer (Brito et al. 2014). On the other hand, Yun et al. (2019) recently showed that increases in the volume of thyroid nodules, initial maximum diameter and initial volume were associated with thyroid cancer, albeit in a rather small study population of 229 patients. It could be surmised, therefore, that ultrasound alone is insufficient in most cases to identify cancer in patients undergoing surgical or nuclear medical treatment for thyroid alterations.

Staniforth et al. (2016) found the likelihood of association between Graves’ Disease and thyroid cancer to be twice as high as the 2% rate accepted by the American Thyroid Association in 2016. These results were confirmed by Mekrasksakit et al. (2019) 3 years later. The present study shows a comparable association between thyrotoxicosis and thyroid cancer, although methods differed between the studies.

By analyzing TSH in groups, we found an association between thyroid cancer and suppressed and elevated TSH levels. Negro et al. (2013) found no correlation between TSH and thyroid cancer in a meta-analysis they performed, but this could be because this study used pooled data. Haymart et al. (2008), on the other hand, found an increased likelihood of malignancy when TSH was elevated. They analyzed a cohort of 843 patients in a single center who had undergone thyroid surgery, of which 241 had thyroid cancers.

This study contained large number of patients and the real-world data from general practitioners with continuously documented diagnoses was used. However, this study has several limitations. They include the use of ICD-10 codes, lack of confounding factors like education, income, alcohol use, sport, smoking status. Finally, no hospital data, no data of endocrinologists and oncologists, and no mortality data was available.

In accordance with the literature, we confirmed that any kind of benign thyroid alteration is associated with an elevated risk of thyroid cancer. The odds ratio is highest for nontoxic goiter, followed by benign neoplasms of the thyroid, other disorders of the thyroid such as Hashimoto and thyrotoxicosis. In addition, we found an elevated risk in patients with either a suppressed or elevated TSH.

Since thyroid cancer rates have been climbing in recent last decades, it may be expedient to monitor benign alterations of the thyroid more closely.

Author contributions

LS and MK: Designed research, co-wrote the manuscript. KK: Acquired data, analyzed data, co-wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Data availability

All data and materials are contained within the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aksoy SÖ, Sevinc AI, Durak MG (2020) Hyperthyroidism with thyroid cancer: more common than expected? Ann Ital Chir 91:16–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito JP, Gionfriddo MR, Al Nofal A, Boehmer KR, Leppin AL, Reading C, Callstrom M, Elraiyah TA, Prokop LJ, Stan MN, Murad MH, Morris JC, Montori VM (2014) The accuracy of thyroid nodule ultrasound to predict thyroid cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:1253–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardis E, Kesminiene A, Ivanov V, Malakhova I, Shibata Y, Khrouch V, Drozdovitch V, Maceika E, Zvonova I, Vlassov O, Bouville A, Goulko G, Hoshi M, Abrosimov A, Anoshko J, Astakhova L, Chekin S, Demidchik E, Galanti R, Ito M, Korobova E, Lushnikov E, Maksioutov M, Masyakin V, Nerovnia A, Parshin V, Parshkov E, Piliptsevich N, Pinchera A, Polyakov S, Shabeka N, Suonio E, Tenet V, Tsyb A, Yamashita S, Williams D (2005) Risk of thyroid cancer after exposure to I131 in childhood. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:724–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean DS, Gharib H (2008) Epidemiology of thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrin Metab 22:901–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante C, Costante G, Lucisano G, Bruno R, Meringolo D, Paciaroni A, Puxeddu E, Torlontano M, Tumino S, Attard M, Lamartina L, Nicolucci A, Filetti S (2015) The natural history of benign thyroid nodules. JAMA 313:926–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MA, Kim JH (2018) Diagnostic X-ray exposure and thyroid cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 28:220–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haymart MR, Repplinger DJ, Leverson GE, Elson DF, Sippel RS, Jaume JC, Chen H (2008) Higher serum thyroid stimulating hormone level in thyroid nodule patients is associated with greater risks of differentiated thyroid cancer and advanced tumor stage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:809–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann K, Lorenzo A, Butt CM, Hammel SC, Henderson BB, Roman SA, Scheri RP, Stapleton HM, Sosa JA (2017) Exposure to flame retardant chemicals and occurrence and severity of papillary thyroid cancer: a case control study. Environ Int 107:235–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Kim MR, Mok JY, Huh JE, Jeon YK, Kim BH, Kim SJ, Kim YK, Kim IJ (2011) Benign cystic nodules may have ultrasonographic features mimicking papillary thyroid carcinoma during interval changes. Endocr J 58:638–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara CM, Linet MS, Beane Freeman LE, Check DP, Church TR, Park Y, Purdue MP, Schairer C, Berrington de González A (2012) Cigarette smoking, alcohol intake and thyroid cancer risk: a pooled analysis of five prospective studies in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 23:1615–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DJ, Kim JY, Baek KH, Kim MK, Park WC, Lee JM, Kang MI, Cha BY (2013) Natural course of cytologically benign thyroid nodules: observation of ultrasonographic changes. Endocinol Metab 28:110–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekrasksakit P, Rattanawong P, Karnchanasorn R, Kanitsoraphan C, Leelaviwat N, Poonsombudlert K, Kewcharoen J, Dejhansathit S, Samoa R (2019) Prognosis of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in patients with graces disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr Pract 25:1323–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro R, Valcavi R, Toulis KA (2013) Incidental thyroid cancer in toxic and nontoxic goiter: is TSH associated with malignancy rate? Results of a meta-analysis. Endocr Pract 19:212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson E, Wintheiser G, Wolfe KM, Droessler J, Silberstein PT (2019) Epidemiology of thyroid cancer: a review of the national cancer database, 2000–2013. Cureus 11(2):e4127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LN, Belsky JL, Yamamoto T, Kawamoto S, Keehn RJ (1974) Thyroid carcinoma after exposure to atomic radiation: a continuing survey of a fixed population, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1958–1971. Ann Intern Med 80:600–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann W, Bongaerts B, Carius HJ, Kruppert Y, Kostev K (2018) Basic characteristics and representativeness of the german disease analyzer database. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 56:459–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RKI (2019) Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten im Robert Koch-Institut: Datenbankabfrage mit Schätzung der Inzidenz, Prävalenz und des Überlebens von Krebs in Deutschland auf Basis der epidemiologischen Landeskrebsregisterdaten. www.krebsdaten.de/abfrage. Accessed 6 Apr 2020

- Ron E, Lubin JH, Shore RE, Mabuchi K, Modan B, Pottern LM, Schneider AB, Tucker MA, Boice JD Jr (1995) Thyroid cancer after exposure to external radiation: a pooled analysis of seven studies. Radiat Rex 141:259–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid D, Ricci C, Behrens G, Leitzmann MF (2015) Adiposity and risk of thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 16:1042–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniforth JUL, Erdirimanne S, Eslick GD (2016) Thyroid carcinoma in Graves’ disease: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg 27:118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker MJ, Orlov D (2003) Thyroid nodules. Am Fam Phys 63:559–566 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun KJ, Ha J, Kim MH, Seo YY, Kim MK, Kwon HS, Song KH, Kang MI, Baek KH (2019) Comparison of natural course between thyroid cancer nodules and thyroid benign nodules. Endocrinol Metab 34:195–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayed AA, Ali MK, Jaber OI, Suleiman MJ, Ashhab AA, Al Shweiat WM, Momani MS, Shomaf M, AbuRuz SM (2015) Is Hashimoto’s disease a risk factor for medullary thyroid carcinoma? Our experience and a literature review. Endocrine 48:629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are contained within the manuscript.