Abstract

Camel milk is a dairy product widely consumed in desert and semi-arid areas, with high nutritional value and potential for auxiliary medical treatment. It has unique efficacy and a gamey taste, and exploring its functional factors and making camel milk more easily accepted by the public has become a research hotspot. This study mainly investigated the protein components in camel milk that may play a role in alleviating insulin resistance by observing the cell activity, glucose consumption, and morphological changes of the treatment group. Further research was conducted on the potential synergistic hypoglycemic effect of camel milk and D-allulose, and a formula was ultimately determined to enhance the flavor of camel milk through a series of sensory evaluation experiments. The optimal concentration for the treatment of insulin resistance (IR) was identified as 4 mg/mL of CWP4 combined with 1 mg/mL of D-allulose for a period of 12 h. The addition of D-allulose at a ratio of 1:36 in camel milk has been observed reduce the odoriferous properties of the camel milk, while simultaneously retaining the majority of other desirable flavors. This research helps to concentrate the functional protein factors in camel milk, promote the intensive processing of camel milk, and develop new camel milk health products. These products may help patients with diabetes stabilize their blood sugar levels in daily life, thus enriching their diet, and may expand the market of camel milk.

Keywords: Alleviated insulin resistance, D-allulose, Camel milk, Hypoglycemic, Food additives

1. Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) is a pathological phenomenon that can cause elevated plasma insulin and hyperglycemia levels. This is manifested by a diminished physiological effect of insulin in the organism, which occurs a result of increased secretion as a compensatory mechanism. This process usually leads to the development of metabolic syndrome, arthrolithiasis and type 2 diabetes. According to a report published by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) indicates that the number of individuals with diabetes worldwide is projected to increase from 463 million in 2019 to 700 million in 2045 [1]. The pharmacological agents employed for the treatment of diabetes mainly include biguanides, sulfonylureas, glinides, α-glucosidase inhibitors thiazolidinediones, insulin and insulin analogues, and a selection of novel therapeutic agents, such as Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, and innovative insulin formulations [2]. The aforementioned pharmacological agents are capable of regulating blood glucose at different levels, they are also come with some adverse reactions. The complications associated with diabetes and the dependence and by-effects of drugs make it challenging for individuals to live. Consequently, there has a trend to choose functional foods into the diet for adjuvant treatment.

Camel milk has been an essential component of the dietary regimen of various populations across Asia, and the Arab region since ancient times [3]. Camel milk, especially fermented camel milk, is a highly nutritious product that is free of common allergens and has been used for centuries for its recognized nutritional and therapeutic benefits. The composition of water, lactose, protein, and fat in camel milk is not significantly different from that of other dairy products. However, it has prominent characteristics in terms of vitamin, immunoglobulin, and fatty acid composition. The distinctive physicochemical properties and physiological functions of camel milk are also significant factors contributing to the growing recognition of its nutritional and economic value [2]. In certain countries and regions, camel milk is traditionally regarded as having medicinal value. In arid areas of Asia and Africa, for example, camel milk has been used as a biomedical treatment for a range of health issues including asthma and edema [4]. Currently, camel milk is referenced in both domestic and international studies as an adjuvant therapy for diabetes with documented benefits for liver, kidney and immune system health [5]. Camel milk has the highest milk fat content and the richest variety of branched-chain fatty acids, with the content reaching 8.00 % of the total fatty acids, which represents a significant good source of branched chain fatty acids [6]. Despite the nutritional advantages of camel milk, its distinctive odor presents a challenge for consumer acceptance, which in turn impedes the advancement of camel milk industrialization [7]. The most commonly used methods for deodorizing dairy products include heat treatment, centrifugal defatting, the addition of masking agents, microbial fermentation, and so forth. Among these, the use of sugar as an additive has been demonstrated to effectively improve the flavor of camel milk while maintaining its nutritional components [8].

D-allulose is a sugar substitute boasting a molecular weight of 180.16 and a melting point of 96 °C. It is readily soluble in water and possesses a sweetness approximately 70 % that of sucrose. In the food industry, D-allulose offers numerous advantages, including ease of processing and a pure, delightful taste. Furthermore, it is more prone to undergoing the Maillard reaction with protein components in food compared to D-fructose and D-glucose. As is well known, the Maillard reaction helps to add a sweet taste, tempting caramel color, and improve the antioxidant performance of food, thereby extending shelf life. It can be seen that it is a food additive with excellent properties [9]. Unlike traditional sweeteners, D-allulose produces only 0.3 % energy of an equivalent amount of sucrose [10]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated to significantly induce GLP-1 release, reduce food intake [11], lowering blood glucose levels and insulin concentration [12], and make a good inhibitory effect on weight gain [13]. D-allulose can reduce the expression of signaling proteins associated with lipid absorption in the small intestine, thereby exerting a lipid-lowering effect. Furthermore, it has been shown to alleviate insulin resistance in experimental rats, increase insulin sensitivity, and improve the function of pancreatic β-cells [14]. Therefore, replacing traditional white sugar and sucrose with D-allulose in food not only does not raise blood sugar, but may also synergize with camel's milk, preserving or even amplifying its health benefits, making it one of the good ways to ease IR.

This study examines the functional protein components in camel milk, their concentration, and the synergistic effect of D-allulose and camel milk protein on the alleviation of IR at the cellular level. It also explores a reasonable formula for improving the flavor of camel dairy products through the combination of this sweetener and camel milk.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh camel milk was purchased from Urumqi, Xinjiang, China (Geographical coordinates 86°37′33″-88°58′24″ E, 42°45′32″-45°00′00″ N); while D-allulose was obtained from Fit Lane Nutrition, USA. The DMEM medium, phosphate buffer solution, 0.25 % trypsin were purchased from Hyclone, USA; fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Sangon Biotech, China; 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiahiazo (-z-y1)-3,5-di-phenytetrazoliumromide (MTT) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shang hai) Trading Co.; metformin, palmitic acid was purchased from Beijing Solabao Technology Co. Glucose assay kit (glucose oxidase method) was purchased from Shanghai Rongsheng Biopharmaceutical Co. The Apoptosis-Hoechst staining kit was purchased from Beyotime Biotech Inc.

2.2. Cell culture and passage

HepG2 cells are a type of hepatoembryonal tumor cell derived from humans that is an ideal cell for studying the pathogenesis related to insulin resistance and the mechanism of hypoglycemic drugs in vitro. Consequently, it is used as a cellular model for the investigation of liver glucose, fructose and galactose metabolism [15,16]. The human liver cancer cell line HepG2 utilized in this experiment was provided by the Key Laboratory of Biological Resources and Genetic Engineering of Xinjiang University.

HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM low sugar medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator. When the cell density reaches 80 %, discard the original culture medium and wash it twice with 2 mL of sterile PBS. After suctioning off the PBS, add 0.5–1.0 mL of 0.25 % trypsin to allow the cells to fully contact with trypsin and let it stand in the incubator for 1–2 min. Take out and observe under a microscope. When the cell protrusions retract, the intercellular gaps become larger, and the cells become almost circular, digestion is completed. Add 2.0 mL of fresh culture medium to terminate digestion, and gently blow and beat repeatedly to evenly disperse the cells. Take an appropriate amount of cell suspension and place it in a new culture bottle. Generally, subculture in a 1:3 ratio. Add 6.0–7.0 mL of complete culture medium to each culture bottle and continue culturing in a CO2 incubator.

2.3. Camel whey separation

After purchasing camel milk samples, they are stored at 4 °C and transported back to the laboratory; fresh milk samples are filtered with a nylon filter (200 mesh) to remove impurities. The samples are then subjected to centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C to remove fat; adjust pH with 10 %(v/v) glacial acetic acid to 4.6, take a 40 °C water bath for 20 min and let it stand at 4 °C for 3 h, then centrifuge at 5000 rpm and 4 °C, discard the precipitate (casein).

The corresponding ammonium sulfate was dissolved in distilled water to create solutions of varying concentrations. Camel milk was added to the ammonium sulfate solution (concentration from low to high), and the precipitated camel whey was collected at the concentration of ammonium sulfate solution of 0–30 %, 30%–50 %, 50%–80 %, and 80%–100 %, respectively. They were named CWP1 to CWP4 (CWP, camel whey protein) and stored at −20 °C after freeze-dried.

2.4. Palmitic acid-induced insulin resistance model

Dissolve 0.1026g of palmitic acid (PA) in 5.0 mL of 80 mmol/L NaOH solution, heated in a water bath at 90 °C, and dissolved by constant shake until the solution was clear and transparent, and then prepared into 80 mmol/L PA storage solution. Add 35.0 mL of 10 % bovine serum albumin to 5.0 mL of PA storage solution and mix thoroughly to prepare a 10 mmol/L PA working solution in a 55 °C water bath. In addition, 0.5 mL 80 mmol/L NaOH solution was added to 3.5 mL 10 % bovine serum albumin at 55 °C and completely dissolved to prepare PA-free solvent stock solution. The above solutions were filtered by 0.45 μm filter membrane. Store at −20 °C for later use.

HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) high sugar medium with 10 % FBS, 1 % penicillin in 37 °C, 5 % CO2 incubator. Cells in log phase were inoculated in 96-well plates at the desired concentrations, set up blank group, control group, and treatment groups. Add different concentrations of palmitic acid (PA) to the treatment group, including 0.05 mM, 0.10 mM, 0.15 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.5 mM, and 1 mM, and treat them for 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, respectively. The MTT method was used to detect the cell activity combined with the glucose content in the cell culture medium measured by the glucose assay kit and apoptosis-Hoechst staining kit to determine the optimal concentration and time for palmitic acid effect, to establish a cellular model of insulin resistance in HepG2 cells. The group established through optimal conditions is called the MODEL group, while a positive control group (Y group) is constructed, which uses metformin to treat the MODEL group.

2.5. MTT method to measure cell activity

HepG2 cells were inoculated in 96 plates with a cell suspension of 1 × 10 5 cells/mL, 150 μL/well, and after they were plastered, wells were replaced with the substances to be tested (treatment group) and continued to incubate, with the wells without added analytes as control group and the wells without cells as blank group. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to dissolve the crystalline particles, and the OD value was subsequently measured at 490 nm (n = 6).

| (1) |

2.6. Detection of glucose consumption in insulin-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma cells

Since extracellular glucose uptake is reduced in cells with IR, the ability of subjects to alleviate IR was assessed by determining the glucose content of the culture medium. Replace the medium with DMEM without test substance or with different concentrations of test substance (0.1–0.05 mmol/L), set up control and model groups, and continue the culture. The culture medium was collected and the glucose content was measured according to the glucose assay kit (n = 3).

| (2) |

2.7. Cell morphology observation

Following the observation of HepG2 cells reaching a stable growth state and the establishment of an injury model, 1 mL/well of the camel whey medium with different concentrations was added and inoculated in 24-well plates. The medium was discarded after 12 h of cultivate, and each group was randomly photographed under a microscope with a field of view.

2.8. Sensory evaluation

A total of 21 participants were involved in the evaluation experiment, each of them had carefully read and signed an informed consent form before the experiment to understand the specific requirements of this experiment. The samples were scored for sweetness, physical taste, sourness, bitterness, saltiness, retention, general impression, and viscosity. A 1–10 points scale was used, 1 = threshold, 10 = very high intensity, no 0 was used. Participants should rate one dimension after tasting each sample, rather than all features, and rinse their mouths as soon as possible to avoid affecting the results of the next sample. The evaluation content was completed within 15 min and statistical analysis was performed at the end of scoring. Subsequently, the highest and the lowest scores were removed from the data, the average value was taken as the final score of each item.

2.9. Application of statistical analysis methods

The data generated in this experiment were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.3 statistical software, while the following conclusions were drawn from the analysis of the data by using one-way ANOVA. Three parallel groups were set for each experimental group, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD. In the figure, ∗ represents P < 0.05, ∗∗ represents P < 0.01, ∗∗∗ represents P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗ represents P < 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of an insulin-resistant HepG2 cell model

Different concentrations of palmitic acid (PA) were applied to HepG2 cells for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h and observe the effects on cell viability and Glucose consumption (Fig. 1). To evaluate the toxic effect of PA on HepG2 cells, cell activity was evaluated using an MTT assay. At 6 h, all concentrations of PA had no significant effect on cell viability. However, following a period of incubation exceeding 12 h, it was found that PA ranging from 0.25 mmol/L to 1 mmol/L produced significant cytotoxicity (Fig. 1a). The consumption of glucose is highly similar to cellular activity. In the PA-induced insulin resistance model, there was no notable difference in glucose consumption among different treatment groups at 6 h. Furthermore, regardless of whether the cells were incubated for 12 or 24 h, all treatment groups exhibited lower glucose consumption compared to the control group.

Fig. 1.

Relative cell viability (a) and glucose consumption (b) after treatment with different concentrations of palmitic acid for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h.

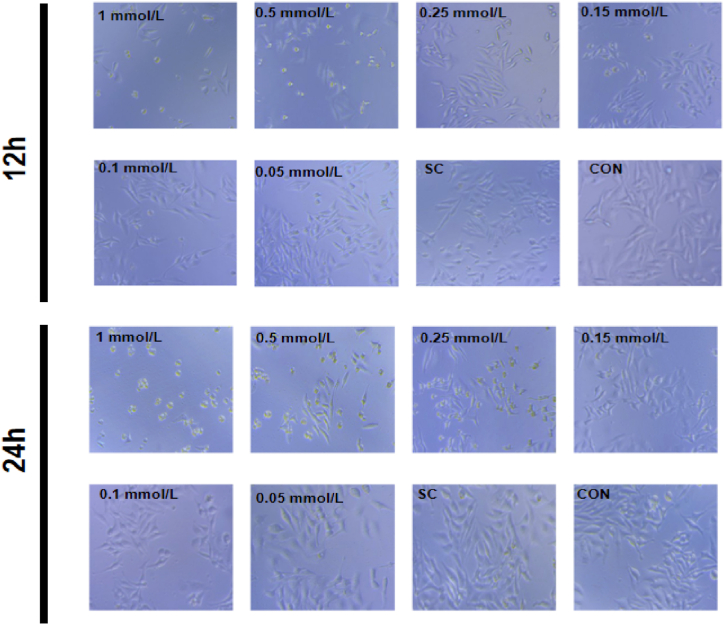

In establishing the insulin resistance model, the optimal conditions for glucose consumption, cell activity and morphology were selected. The cell morphology after treatment with different concentrations of PA for 12 h and 24 h is shown in Fig. 2. After incubation, the number of HepG2 cells decreased compared to the control group after treat with low concentrations of PA (0.050 and 0.100 mmol/L). As the concentration of PA increases, the degree of cell shrinkage and the number of apoptotic cells significantly increase. This may be caused by strong insulin resistance symptoms induced by high concentrations of PA. In view of the above situation, the HepG2 cells treated with 0.1 mmol/L PA for 12 h were selected as the conditions for establishing the insulin resistance model.

Fig. 2.

Cell morphology after 12 h, 24 h treatment with different concentrations of palmitic acid. Sc: solvent control group.

3.2. Effect of camel milk protein treatment on cellular activity and glucose consumption

CWP fractions were added to HepG2 cells for 24 h and 48 h, respectively, in accordance with the constructed cell model. The results indicate that at 24 h of treatment, there were significant differences (P < 0.01) in cell activity (Fig. 3-a) and glucose consumption of the CWP4 group compared with the MODEL group. Nevertheless, the alleviation of IR was not statistically significant in the treatment groups when compared with the MODEL group at 48 h. Ultimately, the protein components precipitated from ammonium sulfate at concentrations ranging from 80 % to 100 % were selected as the optimal experimental group for treatment of HepG2 cells for 24 h. The effects of different concentrations of CWP4 on the relative cell viability and glucose consumption of HepG2 cells are shown in Fig. 3-a and Fig. 3-b. As shown in these two figures, component CWP4 increased the relative cell activity compared to the control and and increased glucose consumption to between the control and MODEL groups, indicating that the addition of CWP4 in the MODEL group alleviated a portion of the IR and brought its state to normal cells. Further exploration of the optimal addition of CWP4 revealed that the cell activity was relatively better in the 4 mg/mL group at 24 h compared to the control group (Fig. 3-c and Fig. 3-d). 48 h was not chosen because the cell viability and glucose consumption of the treated group were lower than those of the control group. Compared with the metformin treatment group, its effect in relieving IR is slightly inferior. The above results showed that the cell activity and alleviation of IR in the 4 mg/mL of CWP4 at 24 h were the best treatment.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different camel whey protein component on relative cell viability (a) and glucose consumption (b); the effects of different concentrations of CPW4 on relative cell viability (c) and glucose consumption (d).

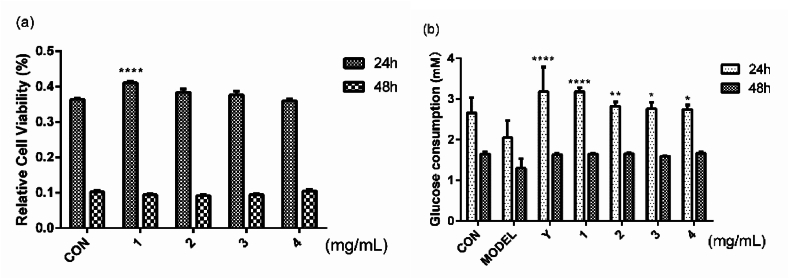

3.3. Effect of D-allulose treatment on cellular activity and glucose consumption

The results of cell activity and glucose consumption after treatment with different concentrations of D-allulose are shown in Fig. 4. The cell activity of 1 mg/mL group was higher than that of the control group at 24 h, while the glucose consumption was also higher than that of the other groups. In terms of glucose consumption, the groups treated with the sweetener and metformin showed similar results, both exceeding the control group and returning to the same level as the control group after 48 h. This indicates that D-allulose itself has strong hypoglycaemic efficacy and can be metabolised relatively quickly. Consequently, the results of the concentration of 1 mg/mL at 24 h is the optimal formula for the treatment of IR.

Fig. 4.

Effects of different concentrations of D-allulose on relative cell viability (a) and glucose consumption (b).

By testing the effects of different concentrations of CWP4 fractions of camel whey (5 mg/mL, 4 mg/mL, 3 mg/mL) and D-allulose (0.5 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, 1.5 mg/mL) combinations on cell activity and glucose consumption for 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48h to select the best collaboration conditions.

As illustrated in Fig. 5 at 6 h, there was no notable distinction in cell activity between the MODEL group, several treatment groups had higher glucose consumption than the MODEL group. At 12 h and 24 h, most experimental groups exhibited higher relative cell viability and glucose consumption to varying degrees, even slightly higher than the positive drug control group Y, with M1, M4 and M5 being particularly prominent. From this figure, it can be observed that with either combination, the relative cell viability gradually decreased to a level approximating that of the control group from 24 h onwards with time, indicating that camel milk and D-allulose undergo the process of acting to metabolizing out of the body within 48 h, and that there is no need to worry about the accumulation. At 48 h, both cell activity and glucose consumption were not performing well in the treatment groups. At 12 h, cell activity is highest in most groups, and glucose consumption is highest in the M5 group at this time. The effect of alleviating insulin resistance should be the most significant.

Fig. 5.

Effects of different concentrations of CWP4 combined with D-allulose on relative cell viability (a) and glucose consumption (b) after 6 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h.

Note: M1: 1.5 mg/mL of D-allulose with 5 mg/mL of CWP4; M2: 1.5 mg/mL of D-allulose with 4 mg/mL of CWP4; M3: 1.5 mg/mL of D-allulose with 3 mg/mL of CWP4; M4: 1.0 mg/mL of D-allulose with 5 mg/mL of CWP4; M5: 1.0 mg/mL of D-allulose with 4 mg/mL of CWP4; M6: 1.0 mg/mL of D-allulose with 3 mg/mL of CWP4; M7: 0.5 mg/mL of D-allulose with 5 mg/mL of CWP4; M8: 0.5 mg/mL of D-allulose with 4 mg/mL of CWP4; M9: 0.5 mg/mL of D-allulose with 3 mg/mL of CWP4.

Fig. 6.

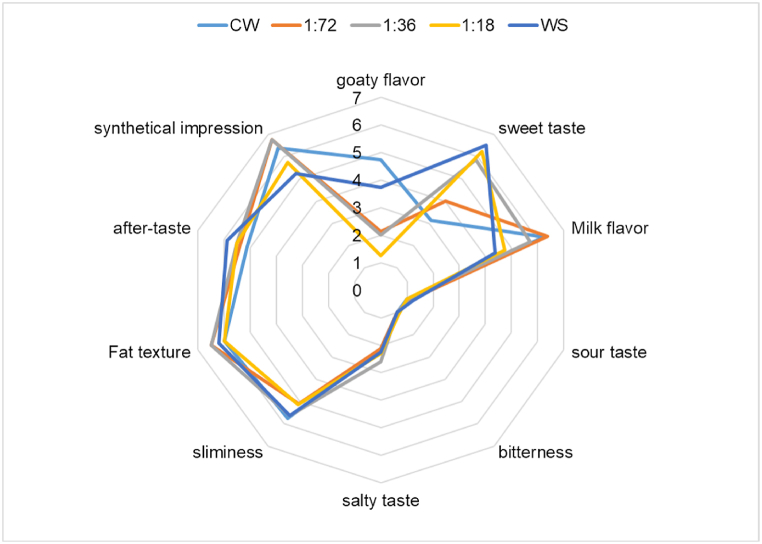

Radar plot of descriptive test for five samples.

Note: CW, Fresh camel whey; 1:72, D-allulose to camel milk 1:72; 1:36,D-allulose to camel milk 1:36; 1:18: D-allulose to camel milk 1:18; WS, white sugar.

Combining the above data, the results showed that the CWP4 fractions of 4 mg/mL of camel whey in combination with 1 mg/mL of D-allulose at 12 h was the optimal formula for the treatment of IR.

3.4. Sensory evaluation

Five groups of samples were designed, including normal fresh camel milk, camel milk mixed with D-allulose at ratios of 1:72, 1:36, and 1:18, and white sugar mixed with camel milk at a ratio of 1:36. Subsequently sensory scoring was performed according to method 2.5 (Fig. 6).

As shown in Fig. 6, the overall flavor was deemed to be evaluated and the evaluation team rated the samples with the white sugar group as less acceptable and recognisable than the other groups. In comparing the characteristic milk flavor of the dairy products, the samples of normal fresh camel milk exhibited the lowest scores. It is possible that the sweetness made the good flavor more pronounced, and every concentration of D-allulose had a low stinkiness score, probably because the D-allulose concealed the stinkiness of camel milk. It has been suggested that camel milk has a high-protein content compared to other dairy products and that substances such as protein produce flavor precursors such as flavor peptides and amino acids with sweet and sour flavors.

The main products of fat hydrolysis are fatty acids, mono- and diglycerides, and short-chain fatty acids, including butyric acid and capric acid. The presence of these products can produce a strong odor, and removing most of the fat from the sample can greatly reduce the negative flavor caused by fat hydrolysis. In addition, adding different sweeteners is also a good way, especially for heat-treated dairy products after adding sugar, which can cause Maillard reaction between sugar and protein in it, not only reducing the gamey taste, but also increasing the charming burnt aroma. The low scores for off-flavors such as sourness, bitterness and astringency indicated that the quality of the four samples was satisfactory. However, a slight salty taste was still present in the camel milk, which may be related to the individual camel's diet. Lipid sensation is a combination of smoothness, fluidity and softness of bovine dairy products in the mouth. This sensation of dairy products in the mouth is mainly due to fat, and the lipid sensation attribute scores of the five samples were consistent and did not differ significantly. Overall, a 1:36 ratio achieved a higher score, resulting in a more balanced taste while retaining special flavors.

4. Discussion

Camels have historically played a pivotal role in facilitating trade and cultural exchange across arid landscapes, including deserts, in regions such as Arabia, the Near East, and North Africa. As globalization progresses, camel milk is becoming increasingly recognized by a wider audience for its distinctive nutritional composition and physiological benefits [3]. Due to its low susceptibility to lactose intolerance symptoms, camel milk has gradually increased its market share as a competitor to cow milk. Grand View Research has projected that the global market for camel milk will reach a value of 18.3 billion US dollars by 2027, and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.8 % from 2020 to 2027. However, the promotion of camel milk faces serious practical challenges, including in some countries where camel milk is considered to have unpleasant flavors (including acidity and saltiness) [7]. In addition, the processing technology of camel milk is also restricted, usually sold in the form of fresh milk or yogurt, which limits its promotion on a global commercial scale [17].

It can be reasonably deduced that odor is the biggest driving factor in expanding the camel milk market. Research has found that the composition of camel milk is influenced by various factors, including but not limited to feeding methods and feed composition, the physiological status of lactating camels, climate and season, and the varieties of camels [18,19]. In order to improve the flavor of camel milk, previous researchers have also made some attempts. For example, by processing camel's milk through microorganisms, diverse microbial communities have fermented to produce different flavors of fermented camel milk beverages. Additionally, camel milk producers in different regions have unique microorganism strains that give the products specific tastes and textures [20]. For example, Mohamed A. Farag used Kefir granules, which contain various bacteria and yeast, to ferment camel milk, and added an appropriate amount of inulin to the product, resulting in a product with a stronger cheese flavor and aroma than milk Kefir [21]. Extracting different species of lactic acid bacteria from dairy products for testing and selecting fermentation strains that are more suitable for industrial production can also help further reduce the odor of sour camel milk. In addition, the bad smell in camel milk can be masked and neutralized by additives, such as the monk fruit sweetener [22], inulin [23], Cordia myxa [24], etc., which can obtain higher sensory evaluation scores.

Camel milk is known to be low-sugar, low-fat, and contains a higher concentration of insulin, which has the potential to improve diabetes [25,26]. In recent years, multi-level research on camel milk to alleviate diabetes has been widely carried out, most of which focus on the determination of the biological activity of the whole component of camel milk or the hydrolyzed polypeptide and its metabolic regulation on the subjects. Indeed, other in vivo and in vitro studies using animal models of type 1 or type 2 diabetes (rats, rabbits, and dogs) and diabetic patients have also confirmed the beneficial effects of camel milk for the treatment of diabetes, including lowering blood glucose, increasing insulin secretion, reducing insulin resistance, and improving blood lipid status [27,28]. After feeding adult male Wistar rats with camel milk protein hydrolysate and camel milk protein whole component separately, Mohammad A Alshuniaber found that both components could reduce fasting blood glucose and insulin levels, as well as multiple blood routine indicators, and hydrolyzed protein had a better effect [29]. Similarly, studies at the cellular level have shown that camel milk can effectively improve palmitic acid-induced cell damage and inhibit apoptosis. Ashraf et al. also used complete camel milk whey protein and some whey protein hydrolysates derived from gastric protease to determine the IR relief effect on HEK293 and HepG2 cells [25].The conclusion drawn is similar to the cell level conclusion made in this article. There are indeed multiple protein enzymes or peptides in camel milk whey protein that have hypoglycemic and insulin resistance relieving effects.

The specific mechanism by which camel milk exerts its anti-diabetic effects involves a range of intricate molecular and cellular processes, encompassing glucose metabolism and transport, as well as insulin synthesis and secretion [30]. Utilizing bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) techniques, it was revealed that both insulin and CWP could enhance the BRET signal intensity between the human insulin receptor (hIR) and insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) in a dose-dependent manner within human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. This finding suggests that both insulin and CWP have the ability to activate the hIR. Similarly, the study of Camelusdromedarius showed that in the absence of insulin stimulation, camel milk did not promote the increase of BRET signal intensity between hIR and IRS1. However, it significantly enhanced the BRET signal stimulated by insulin between hIR and growth factor receptor binding protein 2, suggesting another possible mechanism of camel milk against diabetes [31]. According to the research of many researchers in related fields at the cellular and molecular levels indicates that camel milk may play a role at different levels at the same time, such as affecting the survival, growth and overall activity of islet cells. Limited studies have focused on both the functionality and edible properties of camel milk. Therefore, the key objectives of this study include exploring the functional molecules in camel milk, concentrating on functional components, further enhancing the flavor of camel milk products, and developing a range of camel milk products that are more widely acceptable to the public.

A possible option to improve the taste of camel milk is seasoning, such as adding sugars, aromatic substances, etc. In this study, we chose a healthy sweetener, D-allulose, as a substitute for white sugar. This is a kind of rare sugars found in trace amounts in nature in wheat, fruits, and other foods. In 2011, D-allulose was certified by the FDA as safe and can be used as an additive in food and dietary fields [32]. It not only has moderate sweetness, extremely low-calorie content, good solubility, and is prone to Maillard reactions with food proteins to improve food flavor, but also has various pharmacological effects such as hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and immunosuppressive effects [12]. Hexokinase and Pyruvate kinase are important rate-limiting enzymes in the glycolysis process [33,34]. When the activity of hexokinase and pyruvate kinase in hepatocytes decreases, the utilization of glucose in hepatocytes decreases, glycogen synthesis, and the onset of liver insulin resistance [35]. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that D-allulose can alleviate insulin resistance [14,31,[36], [37], [38]]. The main mechanism of action is that D-allulose inhibits the phosphorylation of IRS-1 and enhances Akt phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Additionally, it inhibits the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) signaling pathways, and enhances glucose uptake and adiponectin secretion. In addition, D-allulose may increase insulin-mediated endothelial NO production, thereby alleviating insulin-mediated microvascular blood flow, enhancing muscle uptake of glucose [39], inhibiting lipid accumulation weight gain [35] and fat deposition [[40], [41], [42]], while also increasing β-oxidation [42] and energy consumption to prevent weight gain and obesity. In addition, D-allulose may be rapidly eliminated in the body through urinary excretion, indicating that it is unlikely to accumulate in the body and cause safety concerns [42].

In this study, we chose to add D-allulose to camel's milk, using the traditional sweetener white sugar as a control, in order to explore the optimal proportion of it to be added. The results showed a ratio of that 1: 36 D-allulose was added to camel milk, and the sample had the lowest odor score. It may be that this concentration of it will cover the odor and there is no lag in other scoring items. The addition of D-allulose in camel milk can cover the odor of camel milk and improve the acceptance of camel milk. In addition to the improvement in the flavour of camel dairy products, we also examined the formulation's enhancement of IR mitigating efficacy.

Many studies at home and abroad have pointed out that camel milk and D-allulose are involved in IRS1 to activate PI3K, AKT, AMPK and other signaling pathways. Therefore, the synergistic effect of camel milk and D-allulose can better alleviate insulin resistance. As result, in this study, different concentrations of D-allulose and camel milk were unitedin the insulin resistance model of HepG2 cells. The combined effect of camel milk and D-allulose demonstrated a significant increase in glucose consumption of the combined resistance group of camel milk and D-allulose was significantly increased, and the processing time was shortened from 24 h to 12 h, shows that camel milk and D-allulose have a significant synergistic effect.

In this study, the improvement effect of camel milk combined with D-allulose on palmitic acid-induced insulin resistance in HepG2 cells at the cellular level. The mechanism may be related to an increase in glucose consumption and the enhancement of glucose metabolism-related enzyme activity levels. The results of the study provide an experimental basis for the development of diabetes treatment drugs under the exploration of camel milk and D-allulose, but the glucose metabolism process is also regulated by many factors. The effect of combined treatment on glucose metabolism and insulin resistance-related protein expression levels needs to be further confirmed.

The results of this study provide an experimental basis for adding D-allulose into camel milk to improve the flavor of camel milk products, while retaining its efficacy in reducing insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Drawing from this study, lactic acid bacteria, yeast, and other fermentation strains conducive to industrial production can be integrated to manufacture cheese, yogurt, and various other dairy products. Additionally, vacuum freeze-drying technology can be employed to make camel milk powder and compressed candies, thereby fostering the acceptance of camel milk among consumers who are enthusiastic about its health benefits and possess a demand for it. This approach offers a pathway for developing a broader range of camel milk products and broadening its global market presence. A meta-analysis [43] of clinical data related to camel milk concludes that unimodal camel milk has limited impact on patients' glucose homeostasis parameters, primarily reducing fasting blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in subjects. Nevertheless, the article also acknowledges that the sample size of research in this field is relatively small, characterized by high heterogeneity and numerous interfering factors that have yet to be excluded. Further elucidation of functional protein structures represents a key research direction for the future. In further research on camel whey protein, we isolated and purified the CWP4 protein components, analyzed the protein composition and sequence using mass spectrometry, and constructed a synthetic pathway for producing a single type of protein in yeast chassis cells, aiming to achieve precise mining and high-yield synthesis of key small molecule functional proteins, laying a substrate foundation for the deep processing of camel milk protein.In terms of developing camel milk products, we will also consider a variety of formulas, including the addition of plant derived antioxidant factors, hypoglycemic function factor, flavor compounds, etc., such as EGCG from green tea [44,45] and Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi polysaccharide [46,47] to maximize the palatability, functionality, and diversity of the products.

5. Conclusion

This study mainly explored the hypoglycemic effects of D-allulose and camel milk, and explored a formula to improve the flavor of camel milk. The conditions of the insulin resistance model human hepatocellular carcinomas (HepG2) cell at the cellular level. The hypoglycaemic effect of the combination was assessed by observing the cellular activity and glucose consumption after treatment with D-allulose and camel milk whey at different concentrations and times, as well as the morphological changes of the cells under the microscope. The effect of different proportions of D-allulose added to camel milk to improve its taste. The best concentration for treating insulin resistance was obtained when camel milk of CW4 protein fractions of 4 mg/mL was combined with 1 mg/mL of D-allulose for 12 h. And adding this sugar substitute in camel milk at a ratio of 1:36 can reduce the odor and preserve other good flavors. The findings provide a foundation for further research on the scope and mechanisms of camel milk, which will contribute to the development of camel milk functional foods and the exploration of drug potential. Camel milk and D-allulose have broad application prospects as safe and functional health foods.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tuerxunnayi Aili: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Zhaoxu Xu: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis. Chen Liu: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Jie Yang: Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Haitao Yue: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethics approval

This article does not require IRB/IACUC approval because there are no human and animal participants.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: HaiTao Yue reports financial support was provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China. HaiTao Yue reports financial support was provided by the Outstanding Young Scientific and Technological Talents Training Program of Xinjiang Autonomous Region. HaiTao Yue reports financial support was provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China. HaiTao Yue has patent issued to CN116327803A. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2019YFC1606102), the Outstanding Young Scientific and Technological Talents Training Program of Xinjiang Autonomous Region (grant 2020Q002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant U2003305, 31860018), the Key Research and Development Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China (grant 2023B02034, 2023B02034-2).

References

- 1.Khan J., Shaw S. Risk of cataract and glaucoma among older persons with diabetes in India: a cross-sectional study based on LASI, Wave-1. Sci. Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-38229-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muthukumaran M.S., Mudgil P., Baba W.N., Ayoub M.A., Maqsood S. A comprehensive review on health benefits, nutritional composition and processed products of camel milk. Food Rev. Int. 2023;39(6):3080–3116. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2021.2008953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benmeziane-Derradji F. Evaluation of camel milk: gross composition-a scientific overview. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021;53(2):308. doi: 10.1007/s11250-021-02689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalesi M., Salami M., Moslehishad M., Winterburn J., Moosavi-Movahedi A.A. Biomolecular content of camel milk: a traditional superfood towards future healthcare industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017;62:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A.A., Ali Al-Attar S.A. The activity of camel milk to treated immunity changes that induced by Giardia lamblia in male rats. ATMPH. 2020;23(4):120–124. doi: 10.36295/ASRO.2020.23415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F., Chen M., Luo R., et al. Fatty acid profiles of milk from Holstein cows, Jersey cows, buffalos, yaks, humans, goats, camels, and donkeys based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Dairy Sci. 2022;105(2):1687–1700. doi: 10.3168/jds.2021-20750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Juboori A.T., Mohammed M., Rashid J., Kurian J., El Refaey S. Nutritional and medicinal value of camel (Camelus dromedarius) milk. 2013:221–232. doi: 10.2495/FENV130201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hameed A., Ishtiaq F., Zeeshan M., et al. Combined antidiabetic potential of camel milk yogurt with Cinnamomum verum and Stevia rebaudiana by using rodent modelling. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023;60(3):1175–1184. doi: 10.1007/s13197-023-05671-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia Y., Cheng Q., Mu W., et al. Research advances of d-allulose: an overview of physiological functions, enzymatic biotransformation technologies, and production processes. Foods. 2021;10(9):2186. doi: 10.3390/foods10092186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchi F., Yaranov D.M., Rollini F., et al. Effects of D-allulose on glucose tolerance and insulin response to a standard oral sucrose load: results of a prospective, randomized, crossover study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki Y., Sendo M., Dezaki K., et al. GLP-1 release and vagal afferent activation mediate the beneficial metabolic and chronotherapeutic effects of D-allulose. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):113. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02488-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z., Gao X.D., Li Z. Recent advances regarding the physiological functions and biosynthesis of D-allulose. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.881037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishii N., Nomizo T., Takashima S., Matsubara T., Tokuda M., Kitagawa H. Effects of D-allulose on glucose metabolism after the administration of sugar or food in healthy dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016;78(11):1657–1662. doi: 10.1292/jvms.16-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pongkan W., Jinawong K., Pratchayasakul W., et al. D-allulose provides cardioprotective effect by attenuating cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity-induced insulin-resistant rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021;60(4):2047–2061. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02394-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordero-Herrera I., Martín M.Á., Goya L., Ramos S. Cocoa flavonoids attenuate high glucose-induced insulin signalling blockade and modulate glucose uptake and production in human HepG2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014;64:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin J., Hu R., Chen M., et al. Effects of berberine on glucose metabolism in vitro. Metabolism. 2002;51(11):1439–1443. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faccia M., D'Alessandro A.G., Summer A., Hailu Y. Milk products from minor dairy species: a review. Animals (Basel) 2020;10(8):1260. doi: 10.3390/ani10081260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kula J. Medicinal values of camel milk. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Res. 2016;2(1):18–25. doi: 10.17352/ijvsr.000009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konuspayeva G., Faye B., Loiseau G. The composition of camel milk: a meta-analysis of the literature data. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009;22(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2008.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konuspayeva G., Faye B. Recent advances in camel milk processing. Animals (Basel) 2021;11(4):1045. doi: 10.3390/ani11041045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farag M.A., Jomaa S.A., El-Wahed A.A., El-Seedi A.H.R. The many faces of Kefir fermented dairy products: quality characteristics, flavour chemistry, nutritional value, health benefits, and safety. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):346. doi: 10.3390/nu12020346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchilina A., Aryana K. Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of camel milk yogurt as influenced by monk fruit sweetener. J. Dairy Sci. 2021;104(2):1484–1493. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-18842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziaeifar L., Labbafi Mazrae Shahi M., Salami M., Askari G.R. Effect of casein and inulin addition on physico-chemical characteristics of low fat camel dairy cream. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;117:858–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atwaa E.S.H., Shahein M.R., Raya-Álvarez E., et al. Assessment of the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of fermented camel milk fortified with Cordia myxa and its biological effects against oxidative stress and hyperlipidemia in rats. Front. Nutr. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1130224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayoub M.A., Palakkott A.R., Ashraf A., Iratni R. The molecular basis of the anti-diabetic properties of camel milk. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018;146:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korish A.A., Abdel Gader A.G.M., Alhaider A.A. Comparison of the hypoglycemic and antithrombotic (anticoagulant) actions of whole bovine and camel milk in streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus in rats. J. Dairy Sci. 2020;103(1):30–41. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shori A.B. Camel milk as a potential therapy for controlling diabetes and its complications: a review of in vivo studies. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015;23(4):609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sboui A., Khorchani T., Djegham M., Agrebi A., Elhatmi H., Belhadj O. Anti-diabetic effect of camel milk in alloxan-induced diabetic dogs: a dose-response experiment. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2010;94(4):540–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2009.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alshuniaber M.A., Alshammari G.M., Eleawa S.M., et al. Camel milk protein hydrosylate alleviates hepatic steatosis and hypertension in high fructose-fed rats. Pharm. Biol. 2022;60(1):1137–1147. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2022.2079678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihic T., Rainkie D., Wilby K.J., Pawluk S.A. The therapeutic effects of camel milk: a systematic review of animal and human trials. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(4):NP110–126. doi: 10.1177/2156587216658846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdulrahman A.O., Ismael M.A., Al-Hosaini K., et al. Differential effects of camel milk on insulin receptor signaling - toward understanding the insulin-like properties of camel milk. Front. Endocrinol. 2016;7:4. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2016.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang W., Zhang Y., Huang J., et al. Thermostability improvement of the d-allulose 3-epimerase from dorea sp. CAG317 by site-directed mutagenesis at the interface regions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66(22):5593–5601. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanasaki A., Iida T., Murao K., Shirouchi B., Sato M. D-Allulose enhances uptake of HDL-cholesterol into rat's primary hepatocyte via SR-B1. Cytotechnology. 2020;72(2):295–301. doi: 10.1007/s10616-020-00378-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeng H.J., Yoon J.H., Chun K.H., et al. Metabolic stability of D-allulose in biorelevant media and hepatocytes: comparison with fructose and erythritol. Foods. 2019;8(10):448. doi: 10.3390/foods8100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee G.H., Peng C., Lee H.Y., et al. D-allulose ameliorates adiposity through the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway in HFD-induced SD rats. Food Nutr. Res. 2021;65 doi: 10.29219/fnr.v65.7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shintani T., Yamada T., Hayashi N., et al. Rare sugar syrup containing d-allulose but not high-fructose corn syrup maintains glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity partly via hepatic glucokinase translocation in wistar rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65(13):2888–2894. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J., Huang W., Zhang T., Lu M., Jiang B. Anti-obesity potential of rare sugar d-psicose by regulating lipid metabolism in rats. Food Funct. 2019;10(5):2417–2425. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01089g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuo T., Izumori K. Effects of dietary D-psicose on diurnal variation in plasma glucose and insulin concentrations of rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006;70(9):2081–2085. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagata Y., Kanasaki A., Tamaru S., Tanaka K. D-psicose, an epimer of D-fructose, favorably alters lipid metabolism in Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63(12):3168–3176. doi: 10.1021/jf502535p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han Y., Han H.J., Kim A.H., et al. d-Allulose supplementation normalized the body weight and fat-pad mass in diet-induced obese mice via the regulation of lipid metabolism under isocaloric fed condition. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016;60(7):1695–1706. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baek S.H., Park S.J., Lee H.G. D-psicose, a sweet monosaccharide, ameliorate hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia in C57BL/6J db/db mice. J. Food Sci. 2010;75(2):H49–H53. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han Y., Yoon J., Choi M.S. Tracing the anti-inflammatory mechanism/triggers of d-allulose: a profile study of microbiome composition and mRNA expression in diet-induced obese mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020;64(5) doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.AlKurd R., Hanash N., Khalid N., et al. Effect of camel milk on glucose homeostasis in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2022;14(6):1245. doi: 10.3390/nu14061245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mokra D., Joskova M., Mokry J. Therapeutic effects of green tea polyphenol (‒)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in relation to molecular pathways controlling inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;24(1):340. doi: 10.3390/ijms24010340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xing L., Zhang H., Qi R., Tsao R., Mine Y. Recent advances in the understanding of the health benefits and molecular mechanisms associated with green tea polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67(4):1029–1043. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hui H., Gao W. Structure characterization, antioxidant and hypoglycemic activity of an arabinogalactoglucan from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;207:346–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yun C., Ji X., Chen Y., et al. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction of Scutellaria baicalensis root polysaccharide and its hypoglycemic and immunomodulatory activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;227:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]