Abstract

In-frame BRAF exon 12 deletions are increasingly identified in various tumor types. The resultant BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins usually lack five amino acids in the β3-αC helix linker and sometimes contain de novo insertions. The dimerization status of BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins, their precise pathomechanism, and their direct druggability by RAF inhibitors (RAFi) has been under debate. Here, we functionally characterize BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and two novel mutants, BRAFdelinsFS and BRAFΔLNVT>F, and compare them with other BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins. We show that BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins not only form stable homodimers and large multiprotein complexes but also require dimerization. Nevertheless, details matter as aromatic amino acids at the deletion junction of some BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins, e.g., BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, increase their stability and dimerization propensity while conferring resistance to monomer-favoring RAFi such as dabrafenib or HSP 90/CDC37 inhibition. In contrast, dimer-favoring inhibitors such as naporafenib inhibit all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants in cell lines and patient-derived organoids, suggesting that tumors driven by such oncoproteins are vulnerable to these compounds.

Aromatic amino acid insertions define the properties of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants.

INTRODUCTION

The serine/threonine kinases of the RAF family comprise the ARAF, BRAF, and RAF1 isoforms and represent critical signaling elements in the RAS/RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. RAFs, in particular the frequently mutated BRAF isoform, emerged as major drug targets in oncology (1). RAF becomes activated by RAS-mediated membrane recruitment, which in turn promotes the transition from a closed autoinhibited to an open conformation in which the exposed kinase domains are activated by dimerization-induced allosteric transactivation (2, 3). The mechanisms leading to physiological and oncogenic RAF activation are best understood from a structural perspective (4–6). RAFs share three conserved regions (CRs): CR1 and CR2 mediate RAS and 14-3-3 binding, respectively, thereby controlling membrane recruitment and the degree of autoinhibition (4, 7). Among other features, the CR3 encompasses the kinase domain, which displays the typical organization of an N- and C-lobe. The kinase domain contains a dimer interface (DIF), which comprises several noncontiguous residues in both lobes (8). Of these, R509, which is located in the conserved R506KTR509HV motif at the C-terminal end of the αC helix, not only plays a key role in the formation and stabilization of RAF dimers (Fig. 1A) but also is essential for the allosteric transactivation of a still inactive receiver protomer by an already activated RAF protein (9–12). The binding of 14-3-3 proteins to the C-terminal end of CR3 also contributes to dimerization (13).

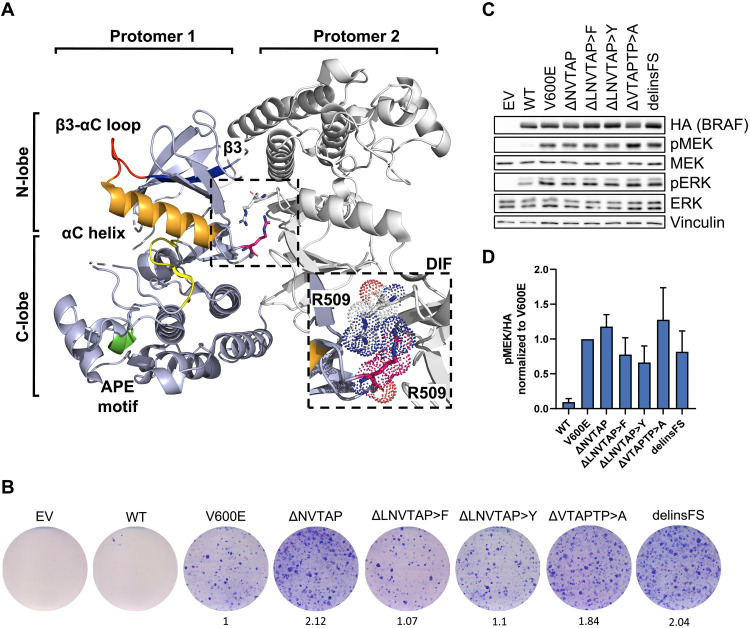

Fig. 1. The recently identified Δβ3-αC mutation BRAFdelinsFS is activating and confers transforming ability.

(A) BRAF elements that are essential in this study are highlighted in protomer 1 of a representative BRAF dimer. Orange, αC helix; red, αC-β3 loop; blue, β3 sheet; pink, R509; green, APE motif; yellow, D594FGLATV600KS motif of the AS. The ribbon diagram, which is based on a crystal structure of dimerized human BRAF kinase domains bound to 14-3-3 proteins [PDB: 6XAG, (113)], was created using the PyMol Molecular Graphics System (version 2.5.2, Schrödinger, LLC). The 14-3-3 dimer was excluded for simplicity. (B) Focus formation assay. MEFs were infected with retroviral vectors encoding the indicated BRAF proteins, cultured for 14 days, and stained with Giemsa reagent. To quantify focus formation, the integrated pixel density was determined using ImageJ and normalized to BRAFV600E. (C) Immunoblot of HEK293T cells expressing the indicated BRAF proteins. (D) Immunoblots were quantified using ImageJ. The bar graph shows pMEK/hemagglutinin (HA) levels (means + SD, n = 3) normalized to BRAFV600E. Images are representative of at least three independent experiments.

RAS recruits BRAF to the membrane and assists in its full activation by relieving the kinase domain from 14-3-3–mediated autoinhibition (14). The exposed kinase domain engages in homo- or heterodimerization with other RAF protomers, which in turn induces their conformational changes (3, 12, 15) that are probably accompanied by phosphorylation of the D594FGLAT599V600KS602 motif within the activation segment (AS) (16). While AS phosphorylation has not been observed in recent mass spectrometry (MS) experiments (6), it is supported by structural and genetic approaches (12, 17, 18). For example, T599 phosphorylation is mimicked by the most common oncogenic BRAF mutation, V600E, which generates a mutation-specific salt bridge between E600 and K507 in the αC helix of the N-lobe, which in turn shifts the αC helix and AS into the active “αC helix-IN/DFG-IN/R506-IN” conformation (17, 19, 20). Consequently, this salt bridge locks BRAFV600E in the active conformation and exempts it from multiple regulatory requirements, including an intact RAS-binding domain, DIF, AS, and the C-terminal 14-3-3–binding site (9, 11, 18, 21). The fact that BRAFV600E can still provide high and transforming ERK activity in the presence of artificial DIF and/or C-terminal 14-3-3–binding site mutations suggests that it signals as a monomer, and indeed, it could be shown that it is only receptive to V600E-selective type I1/2 RAF inhibitors (RAFi) in its monomeric state due to the phenomenon of negative allostery (20, 22). However, these findings do not indicate that BRAFV600E always exists as a monomer in living cells. We and others showed that BRAFV600E displays a higher dimerization propensity than wild-type (WT) BRAF (BRAFWT) and is more effective in phosphorylating MEK in its dimeric state and that a large fraction of this oncoprotein resides in large protein complexes that are sensitive to DIF mutations (9, 17, 23, 24).

The phosphorylation- and dimerization-induced conformational changes within the kinase domain also promote its transition from an inactive to an active conformation, involving the realignment of conserved hydrophobic regulatory residues. If they are aligned in the active conformation, they will constitute the so-called R-spine that is essential for catalysis. The spine residues provide critical contact points for RAFi, and hence, their orientation, along with that of the αC helix and the AS, decides about drug binding and efficacy (12, 25). For example, the clinically irrelevant type I inhibitors stabilize the RAF kinase domain in its active αC helix-in/DFG-in/R506in conformation, while type II compounds, such as the approved sorafenib and the clinical phase 2 trialed naporafenib, stabilize the αC helix-in/DFG-out/R506in conformation. The clinically used BRAFV600E-selective drugs vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib represent the aforementioned type I1/2 inhibitors, inducing an αC-helix-out/DFG-in/R506in conformation (20).

The spectrum of BRAF alterations is still expanding because of the increasing sequence coverage of tumor genomes. Oncogenic mutations are subdivided into single-nucleotide/amino acid substitutions (e.g., V600E), small in-frame insertions/deletions resulting in full-length BRAF proteins with altered kinase activity, and gene fusions (26). Their complexity is increased by the fact that BRAF oncoproteins differ in their enzymatic activity and drive MEK/ERK hyperactivation by various mechanisms (27). These differences have practical implications for targeted therapies and stimulated the classification of BRAF oncoproteins (26). Class I mutants are confined to V600 substitutions and can still unfold their high intrinsic enzymatic activity and oncogenic signaling potential if deprived of the aforementioned dimer-promoting features. In contrast, class III mutants represent the other end of the spectrum as they display lower intrinsic kinase activity than BRAFWT or lack kinase activity at all. They cooperate with activated RAS and induce paradoxical MEK hyperactivation by dimerizing with catalytically competent RAF protomers and promoting their transactivation (9, 28, 29). Class II contains a wide spectrum of BRAF oncoproteins with varying degrees of intermediate activity (30). They rely on dimerization but can signal independent of RAS (21).

The so-called BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants represent still relatively underexplored but potentially highly active oncoproteins found in various tumor entities, especially in KRAS WT pancreatic neoplasia (31–34). According to the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) database, 0.005% of its curated pan-cancer samples encode BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants. As the responsible mutations map to exon 12, which is ignored by most diagnostic procedures that only address exons 11 and 15, their frequency is probably underestimated, in particular for “RAS/BRAF WT” tumors of typically RAS/ERK pathway–driven entities. At the protein level, BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants are characterized by short in-frame deletions removing usually five amino acids in the loop linking the β3 strand with the αC helix (35–37). As this deletion affects the orientation of the αC helix (Fig. 1A), which in turn controls the exposure of the R506KTR509HV motif, BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants might display an aberrant dimerization behavior. However, the first studies describing BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants arrived at different conclusions whether they signal as dimers or autonomous monomers (35–37). However, defining the biochemical properties of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, which determine RAFi efficacy, is of direct clinical relevance, as Molecular Tumor Boards (MTBs) increasingly discuss the druggability of these oncoproteins in clinical decision-making. Here, we provide an in-depth analysis of the signaling potential and dimerization state of various BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins, including the previously uncharacterized BRAFΔLNVTAP>F oncoprotein and the hitherto undescribed BRAFdelinsFS and BRAFΔLNVT>F mutants. By defining their druggability, we observed an unexpected variety in dabrafenib responsiveness, while sorafenib and the phase 2 trialed compound naporafenib inhibit all mutants tested. We also dissect the mechanism determining dabrafenib sensitivity and propose an algorithm for choosing the appropriate RAFi in the clinical setting.

RESULTS

Identification of the previously unidentified in-frame deletion mutant BRAFdelinsFS

This study was prompted by a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) case analyzed within the Molecularly Aided Stratification for Tumor Eradication Research (MASTER) program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) and the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) (38) in which a BRAF exon 12 p.L485-P490delinsFS (BRAFdelinsFS) was detected. The patient was diagnosed with poorly differentiated PDAC and hepatic metastases at the age of 58. Palliative chemotherapy with mFOLFIRINOX [oxaliplatin, leucovorin, irinotecan, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)] resulted in an objective response and was deescalated to 5-FU after 7 months. At disease progression 4 months later, treatment was changed to irinotecan/5-FU [time to progression (TTP), 6 months]. Further treatment lines were nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine (TTP, 7 months), nal-irinotecan (TTP, 9 months), and FOLFOX4 (TTP, 2 months). The patient was then enrolled in NCT/DKTK MASTER, and treatment was switched to gemcitabine/erlotinib (TTP, 3 months), which was continued beyond progression due to reduced tumor growth compared to previous regimens and a lack of therapeutic alternatives. On the basis of the BRAFdelinsFS mutation detected, MEK inhibition ± RAFi was recommended by the MTB. Unfortunately, no suitable clinical trial was available at that time, and the patient died 3 months later at the age of 62.

BRAFdelinsFS lacks six of the original amino acids of the β3-αC helix loop but carries two de novo–introduced residues, a phenylalanine and a serine, in this segment (Fig. 1A). As this represents a net deletion of four amino acids, as compared to the previously published Δβ3-αC mutants, and because deletion length influences signaling activity (36, 37), we analyzed the properties of BRAFdelinsFS. First, we compared the transformation potential of the previously uncharacterized BRAFdelinsFS mutant with that of other Δβ3-αC mutants (described in fig. S1) and BRAFV600E in immortalized murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Fig. 1B). BRAFdelinsFS induces foci to a similar extent as the other Δβ3-αC mutants, including the previously described but functionally uncharacterized BRAFΔLNVTAP>F (39). Commensurate with their transformation potential, all mutants activated the ERK pathway in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells (Fig. 1, C and D). The MEK/ERK phosphorylation potential of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants was not affected by the AVKA mutation replacing T599 and S602 by alanine residues (fig. S1B). This is reminiscent of BRAFV600E, which, unlike other BRAF oncoproteins, signals independent of an intact T599V600KS602 motif (18, 40, 41), indicating that AS-induced conformational changes are also dispensable for BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins.

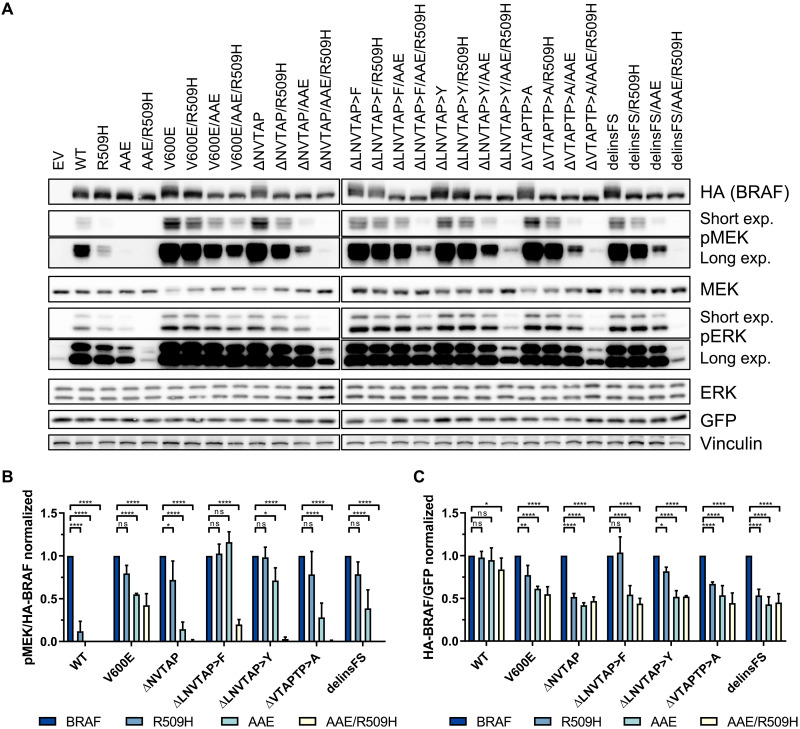

BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants require dimerization for oncogenic signaling and stability

The initial studies disagreed whether BRAFΔβ3-αC act as mono- or dimers and whether they require an intact DIF to unfold their oncogenic potential (24, 35, 36). This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that these laboratories studied different BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (fig. S1A). Therefore, we assessed the dimerization capacity of BRAFdelinsFS, which formed heterodimers with RAF1 and displayed increased homodimerization potential with coexpressed BRAFWT and even more pronounced with itself (fig. S1C). This finding and the aforementioned controversy about the requirements of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants for an intact DIF prompted us to systematically analyze the effects of the R509H and AAE mutations, either singly or in combination, on the signaling potential of these oncoproteins (Fig. 2). The typical DIF mutation, R509H, impairs BRAF homo- and, albeit to a lesser extent, heterodimerization (9). The AAE mutation was inspired by the noncanonical APE motif (AAE) at the C-terminal end of the ARAF AS that indirectly decreases the dimerization propensity of RAF kinases (24). We included BRAFV600E as a reference for a BRAF oncoprotein that can signal and transform independent of an intact DIF (9, 11, 24, 42). Commensurate with previous findings (9, 24), the R509H and AAE substitutions had a strong and severe impact on the MEK phosphorylation potential of BRAFWT, respectively. In contrast, BRAFV600E was less affected and only the simultaneous introduction of the R509H and AAE mutations reduced the MEK phosphorylation potential by more than 50% (Fig. 2B). Likewise, the BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants resembled BRAFV600E as they remained highly and moderately active in the presence of the R509H and AAE alterations, respectively. Only their combination reduced the MEK phosphorylation potential of BRAFV600E by more than 70%. Unexpectedly, the BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants differed in their sensitivity toward the R509H and AAE mutations, with BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y being most resistant (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 2. Dimerization is essential for the activity and stability of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants.

(A) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated HA-BRAF plasmids. Total cell lysates (TCLs) were analyzed by immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. Vinculin detection serves as a loading control. Images are representative of three independent experiments. (B and C) Immunoblots were quantified using ImageJ. Data were normalized to the corresponding BRAF protein without the additional dimerization-impairing mutations R509H and/or AAE. Statistical analysis: means + SD, n = 3, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett‘s test for multiple comparisons, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. ns, not significant.

We also assessed the transformation potential of the BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants in simian virus 40 large T antigen immortalized murine fibroblasts (MEFs) and compared it with that of BRAFV600E and BRAFF595L, another oncoprotein with lower intrinsic kinase activity than BRAFV600E (43) but potent focus formation potential (44). These MEFs display a stringent contact inhibition response that is only overridden by oncogenic but not WT BRAF (18, 40, 44). As seen in Fig. 1B and fig. S2A, all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants caused focus formation to a similar extent as the high-intensity BRAFV600E mutant, and hence, their transforming activity correlates with their MEK phosphorylation potential. However, introducing the R509H and AAE mutations, either singly or in combination, increased the focus formation of MEFs transformed by BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, albeit this effect was influenced by the individual in-frame deletion. At first glance, this observation appears counterintuitive but ties in with our previous observation that BRAF oncoproteins with an intermediate activity, e.g., BRAFF595L, are more effective in driving the proliferation of these MEFs than BRAFV600E (18, 44). Thus, although all cells expressing BRAFV600E and the BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants displayed a transformed morphology (fig. S2B), the correlation between MEK/ERK phosphorylation and focus proliferation follows a bell-shape curve (fig. S2C).

The R509H and AAE mutations increased the electrophoretic mobility of all BRAF proteins, which probably reflects their decreased phosphorylation status due to reduced feedback and transphosphorylation events (45). On closer inspection of the BRAF bands on well-resolved Western blots (Fig. 2A), we noticed that R509H and, in particular, AAE reduced the amount of the BRAF proteins. This apparent reduction was not caused by differences in phosphorylation status that might interfere with protein transfer or detection, as dephosphorylation of BRAFΔNVTAP did not increase its abundance (fig. S3). To distinguish between an effect on BRAF stability and abundance differences caused by distinct transfection efficiencies or transcript production/stability, we exploited the bi-cistronic design of the hemagglutinin (HA)–BRAF–internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)–green fluorescent protein (GFP) cassette of the pMIG vectors from which HA-BRAF and GFP are coexpressed (9). The quantitative assessment of the HA-BRAF/GFP ratio confirmed that BRAFWT levels were hardly affected by dimerization-impairing mutations (Fig. 2C). R509H had little to no effects on the abundance of the high-activity BRAFV600E class I mutant, the intermediate-activity class II mutant BRAFF595L (44), BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y, while that of the other BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants was reduced by 30 to 50% (Fig. 2, A and C, and fig. S4, A and C). Linear regression between GFP-normalized HA-BRAF expression and HA-BRAF–normalized pMEK levels upon R509H introduction revealed that, in contrast to the class II mutant BRAFF595L, the stability of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, as reflected by their abundance, correlates with their MEK phosphorylation potential (fig. S4, B to D). It should be noted that the effects of the R509H and AAE mutations on the stability of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants were neither quantified nor remarked in the initial publications (24, 35, 36). Upon densitometry of the Western blot bands in these three publications, however, we noted that all three studies showed that the R509H mutation reduced the abundance of all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants to a similar extent (fig. S4E).

BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants display high dimerization propensity and form large multiprotein complexes containing heat shock protein 90

Given the profound effect of dimer impairing mutations on the activity and stability of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, we next analyzed their homodimerization potential (Fig. 3, A and B). This experimental setup in which the BRAF dimers are purified by anti-HA immunoprecipitation reveals stable dimers and can discriminate the various affinities displayed by BRAF mutants. Using this assay, we, and subsequently others applying different methods, demonstrated that BRAFV600E, despite its ability to signal as a monomer under artificial circumstances, has a higher homodimerization propensity than BRAFWT (9, 17, 46). Unexpectedly, all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants displayed an even higher and significantly elevated homodimerization potential compared to BRAFV600E (Fig. 3, A and B). Nevertheless, homodimerization was reduced but not abolished by the R509H mutation, whereas combination of R509H and AAE mutations abrogated the homodimerization potential of all analyzed mutants. The BRAFΔLNVTAP>F oncoprotein, whose MEK/ERK phosphorylation potential was the least affected by the R509H substitution, still retained more than fivefold homodimerization capacity over BRAFV600E after introducing this DIF mutation.

Fig. 3. BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants form exceptionally stable dimers, with varying sensitivities to the R509H mutation and affinity toward each other and heat shock protein 90.

(A) The indicated HA- or Myc-tagged BRAF proteins were coexpressed in HEK293T cells. BRAF complexes were precipitated with an anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates and TCLs were analyzed by immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. TCLs confirm the expression of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and the BRAF proteins in question for all coimmunoprecipitations. Images are representative of three independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation. (B to D) Immunoblots were quantified using ImageJ. Bar graphs show copurified Myc-BRAF (B) or HSP90 [(C) and (D)] per precipitated HA-BRAF. Statistical analysis: means + SD, n = 3, one-way (C) or two-way [(B) and (D)] ANOVA with Tukey’s [(B) and (C)] or Dunnett’s (D) test for multiple comparisons, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (E) Analysis of BRAF complexes by BN-PAGE. HEK293T cells expressing the indicated BRAF proteins were cultured in the presence of the HSP90 inhibitor XL888 (1 μM) or vehicle control for 4 hours, followed by lysis. TCLs were analyzed by Western blotting following BN-PAGE (left), using the indicated antibodies. To confirm the inhibition of HSP90 binding, BRAF complexes were precipitated using an anti-HA antibody, followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. TCLs confirm comparable expression levels of CDC37, HSP90, and the BRAF proteins in question for coimmunoprecipitation and BN-PAGE. Representative images for two biological replicates are shown. See also fig. S5B.

Almost all high-activity BRAF point mutants, except for a few variants such as the highly dimerization-proficient BRAFE585K oncoprotein, require the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90)/CDC37 chaperone complex for their activity (47, 48). In addition, BRAFV600E forms large multiprotein complexes with this chaperone (23). As the requirement and affinity of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants for HSP90 remains unknown, we assessed the HSP90 levels in immunoprecipitates and observed increased HSP90 binding compared to BRAFWT, albeit to a different extent (Fig. 3, A, C, and D). The only exception is BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, which exhibits no significant difference in HSP90 recruitment compared to BRAFWT. The dimerization impairing R509H and AAE mutations further increased the interaction between HSP90 and the various BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants. Nonlinear regression of precipitated BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants and HSP90 revealed a negative correlation among BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants between homodimerization and HSP90 binding (fig. S5A), suggesting that dimerization and HSP90 binding cooperate and potentially compensate each other in stabilizing BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants. Using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and size exclusion chromatography–based proteomics, we demonstrated previously that hyperactive and dimeric BRAFV600E predominantly occurs in a large multiprotein complex enriched with HSP90 and its co-chaperone CDC37, while BRAFWT is mostly confined to a small complex (9, 23). Therefore, we applied BN-PAGE to compare the sizes of multiprotein complexes containing either BRAFWT, BRAFV600E, BRAFΔNVTAP, or BRAFΔLNVTAP>F. This analysis revealed that the propensity of BRAFV600E to form a large multiprotein complex was even further enhanced in both BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, as the small complex almost completely disappeared in these samples (Fig. 3E and fig. S5B). This effect was most pronounced in lysates from cells expressing BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, which displayed a particularly large complex of >880 kDa. Albeit to a lesser extent, this complex was also observed in lysates from BRAFΔNVTAP but not detected in those expressing BRAFV600E or BRAFWT. The increasing abundance in large BRAF complexes and the emergence of the >880 kDa complex correlate with the strongly increased dimerization potential of both BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants compared to BRAFV600E (Fig. 3B). Given the unexpected finding that BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, unlike the other BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, did not differ from BRAFWT in terms of HSP90 recruitment (Fig. 3, A, C, and D), we analyzed the colocalization between BRAF, CDC37, and HSP90 in BN-PAGE experiments and the association of the three proteins by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 3E). CDC37, which recruits kinases to HSP90, was enriched in large complexes comigrating with that of BRAFV600E and BRAFΔNVTAP, and this colocalization was almost abolished by the clinically tested HSP90 inhibitor XL888 (49). As expected from the coimmunoprecipitation experiments shown in Fig. 3 (A, C, and D), CDC37 was less abundant in large complexes comigrating with those organized by BRAFΔLNVTAP>F. Unfortunately, we could not identify an HSP90 complex that comigrated with the large BRAF-containing complexes in our BN-PAGE experiments. We assume that the epitope for the anti-HSP90 antibody is not accessible in native complexes because HSP90 and CDC37 were readily detected as XL888-sensitive interactors in SDS-PAGE–resolved and, hence, denatured BRAFV600E and BRAFΔNVTAP coimmunoprecipitates from this experimental setup (Fig. 3E).

Together, our BN-PAGE and coimmunoprecipitation experiments indicate that the CDC37/HSP90 complex is present in the large molecular mass complexes typically formed by BRAFV600E and BRAF∆NVTAP but not BRAF∆LNVTAP>F. Our data also show that BRAF oncoproteins do not form one but multiple high molecular mass complexes and that the >880 kDa complex observed predominantly in BRAF∆LNVTAP>F-expressing cells predicts a multiprotein assembly independent of HSP90/CDC37.

Vulnerability of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants toward HSP90 inhibition correlates with their dimerization propensity

The reduced abundance of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants could be linked to an inherent instability that is compensated by increased homodimerization and/or HSP90 binding. To address these hypotheses, we generated Braf-deficient MEFs harboring tetracycline (tet)–regulated expression vectors for the BRAF proteins in question to monitor their longevity following tet washout (fig. S6). BRAFWT, its R509H/AAE counterpart, and BRAFΔLNVTAP>F displayed longer half-lives than BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFV600E (fig. S6, A to C). Our calculated half-life of BRAFV600E in MEFs was in a similar range as reported for HEK293T cells (50). In agreement with the reduced BRAF levels shown in Fig. 2, impairing the dimerization potential of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F by the R509H/AAE mutations reduced its half-life into the range of BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFV600E (fig. S6C).

Next, we investigated whether XL888 would affect the stability of BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S7). XL888 caused a noticeable depletion of BRAFΔNVTAP down to 50%. In contrast, BRAFΔLNVTAP>F levels were only mildly reduced at 8 hours and comparable to those of BRAFWT. In line with Fig. 3, increased HSP90 binding induced by reduction of dimerization potential (R509H AAE) sensitized BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and BRAFWT for HSP90 inhibition. This suggests that BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants are less stable and are stabilized to a different extent by increased dimerization or HSP90 binding.

Fig. 4. BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants show enhanced susceptibility to HSP90 inhibition.

(A) Expression of the indicated BRAF proteins in lentivirally transduced MEF lines was induced by tet addition for 72 hours, followed by addition of XL888 (1 μM). Cells were lysed after the indicated XL888 treatment periods, and HA-BRAF levels were quantified by Western blot. (B) BRAF levels were normalized to α-tubulin. Bar graph shows the reduction of BRAF levels after 8 hours. Statistical analysis: means + SD, n = 3, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (C) Following cultivation of OV-90 cells in the presence of 1 μM XL888 or control [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] for 24 hours, endogenous BRAF was purified and digested with trypsin before MS. Abundances of the BRAFWT (MLNVTAPTPQQLQAFK)– and corresponding BRAFΔNVTAP (MLTPQQLQAFK)–derived peptides were compared between control (DMSO) and XL888-treated cells. Peptide abundance for both proteins purified from DMSO-treated cells was set to 1 and was measured in technical triplicates. Statistical analysis: means + SEM, unpaired, two-tailed t tests, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. AU, arbitrary units.

To confirm the decreased stability and enhanced XL888 sensitivity of an endogenously expressed BRAFΔβ3-αC mutant, we established an approach using the human ovarian carcinoma cell line OV-90 in which we can monitor the coexpression, as suggested by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (fig. S13A), and abundance of BRAFWT and BRAFΔNVTAP side by side. By looking at the distribution of trypsin cleavage sites in BRAF, we reasoned not only that MS would allow us to detect a peptide specific for the ΔNVTAP deletion but also that HSP90 inhibition should trigger its depletion. The BRAFΔNVTAP-derived peptide was reduced by 50% upon XL888 treatment, whereas the abundance of the BRAFWT peptide was unaffected (Fig. 4C). Our MS approach might be also of diagnostic interest as it could be useful to confirm the endogenous expression of similar oncoproteins generated by short in-frame deletions/insertions, e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and HER2 (36), which cannot easily be distinguished from their WT counterparts by Western blotting or by immunohistochemistry.

BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants differ in their sensitivity toward type I1/2 inhibitors but are all blocked by type II compounds

However, how could tumors with BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants be treated with targeted therapy? MEK inhibitors (MEKi) would be an obvious choice as trametinib blocked ERK pathway activation by all BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins (fig. S8A). We also searched for a strategy directly inhibiting BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants as such a RAFi could be very useful, either in a monotherapy setting or as a component of a vertical pathway inhibition strategy (51). In the initial studies, however, the tested BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants were not blocked by the type I1/2 inhibitor vemurafenib, while they remained sensitive toward the type I inhibitor GDC-0879 and the type II inhibitors LY3009120 and AZ-628 (35, 36). We confirmed these findings for LY30009120 and vemurafenib and extended them to other BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (fig. S8, B and C).

As the phase 1 trial of LY3009120 was terminated because of inefficacy (52) and GDC-0879 as well as AZ-628 have not progressed beyond preclinical testing [(19) and our own research on https://clinicaltrials.gov], we first analyzed the sensitivity of the highly active and dimerizing BRAFΔLNVTAP>F oncoprotein toward other type II inhibitors, including the clinically applied sorafenib and currently trialed inhibitors such as belvarafenib (53) and naporafenib (LXH254) (54). We also tested the clinically available type I1/2 inhibitors dabrafenib and encorafenib for their activity against BRAFΔLNVTAP>F. While few data are available for dabrafenib for BRAFΔNVTAP (35), the activity of encorafenib against BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants is unknown. Both type I1/2 inhibitors were ineffective against BRAFΔLNVTAP>F (fig. S8D). In contrast, all type II inhibitors impaired MEK/ERK activation by BRAFΔLNVTAP>F.

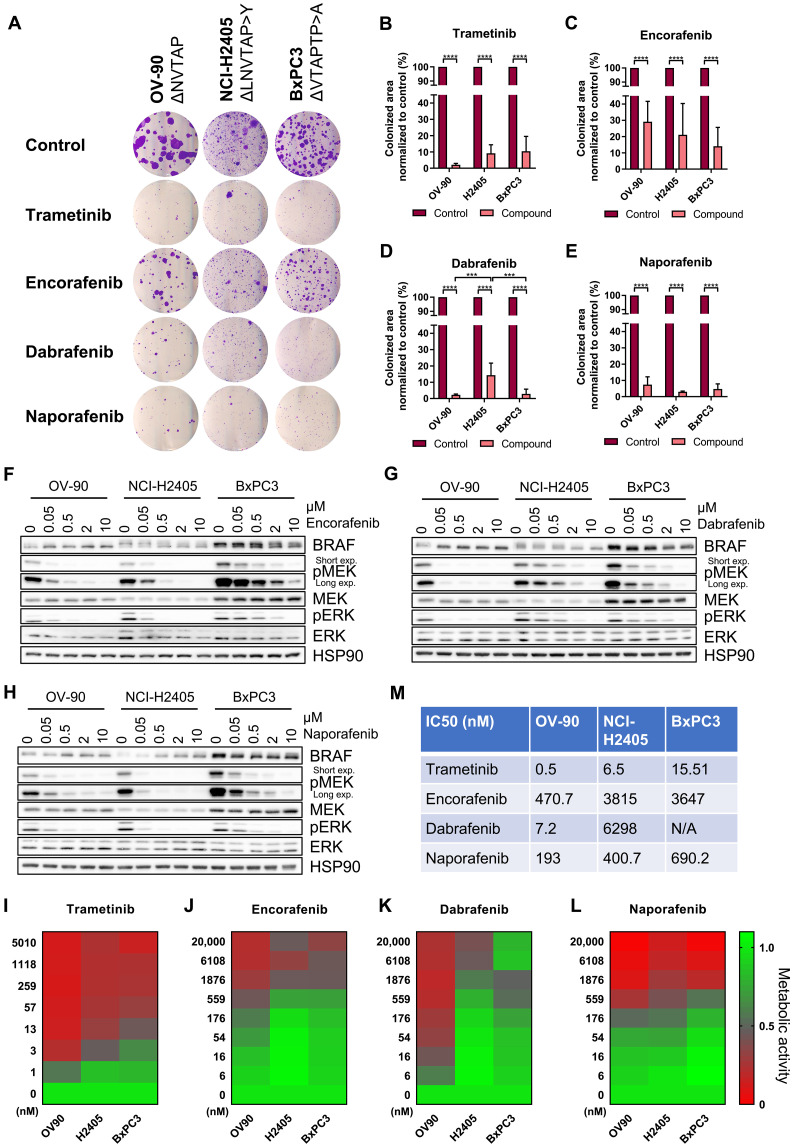

Given the poor sensitivity of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants toward vemurafenib (fig. S8C), the clinical availability of dabrafenib and encorafenib, and their distinct effects on kinase domain conformation (19), we compared the sensitivity of additional in-frame deletion mutants to these type I1/2 inhibitors and naporafenib. HEK293T cells expressing BRAFV600E served as reference for successful inhibition by dabrafenib and encorafenib. While encorafenib was quite ineffective in reducing MEK phosphorylation triggered by all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, dabrafenib inhibited BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFΔVTAPTP>A but not BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y, and BRAFdelinsFS. Notably, we rather observed a trend for increased MEK phosphorylation in cells expressing BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y treated with these type I1/2 inhibitors (Fig. 5, A, B, E, and F). In contrast, the type II inhibitor naporafenib was effective against all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (Fig. 5, C to G). As often observed in these experiments and probably reflecting the multiple feedback loops and rheostasis mechanisms operating in the RAS/ERK pathway (40, 55–58), the RAFi-mediated effects were more pronounced at the level of MEK than ERK phosphorylation. Nevertheless, pERK levels followed similar trends (fig. S9).

Fig. 5. BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants exhibit varying sensitivity to encorafenib and dabrafenib, but all of them are potently inhibited by dimer-targeting naporafenib.

(A to D) The indicated HA-BRAF proteins were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells. Before lysis, cells were treated with encorafenib (0.5 μM), dabrafenib (1 μM), naporafenib (1 μM), sorafenib (10 μM), or vehicle control (DMSO) for 4 hours. The lysates were analyzed by immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. (E to H) Immunoblots were quantified using ImageJ. Bar graphs show calculated fold changes (inhibitor/control) of phospho-MEK levels normalized to HA-BRAF. The indicated inhibitors were compared to vehicle control (E) to (G) or each other (H) for each BRAF protein. BRAFV600E served as a control. Statistical analysis: means + SD, n = 3, unpaired t tests with Holm-Šídák correction for multiple comparisons (E) to (G) or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (H), *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Quantified phospho-ERK levels are shown in fig. S9.

Given the contrasting efficacies of type I1/2 compounds against the various BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, we next assessed their affinity in a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) in which drugs stabilize their target against heat-induced denaturation in cellulo (59). Thermal stability of the dabrafenib-sensitive mutants BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFV600E (positive control) was increased by dabrafenib, whereas that of the insensitive BRAFΔLNVTAP>F oncoprotein remained unaffected, indicating inefficient drug accommodation (fig. S10, A to D). Thus, CETSA confirms the suspected variation in binding efficiency of dabrafenib to BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins. BRAFΔLNVTAP>F activity, monitored via phospho-MEK levels (fig. S10E), was eventually inhibited in the presence of 100 μM dabrafenib, an exceptionally high concentration not achievable in a therapeutic setting, suggesting that drug binding to BRAFΔLNVTAP>F is not completely prevented. This impaired drug binding could explain the observed paradoxical activation in BRAFΔLNVTAP>F- and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y-expressing HEK293T cells treated with encorafenib or dabrafenib (Fig. 5, A, B, D, and E). In cells expressing dabrafenib-/encorafenib-receptive mutants like BRAFΔNVTAP, the applied inhibitor concentration saturated most protomers. In contrast, the same concentration is only subsaturating in cells expressing variants like BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y that display a reduced binding affinity to these type I1/2 compounds. The few drug-bound BRAFΔLNVTAP>F/Y protomers, however, that manage to take up these inhibitors might serve, because of their high dimerization propensity (Fig. 3B), as highly potent allosteric transactivators of drug-free RAF protomers, resulting in paradoxical MEK phosphorylation (60, 61). This model is supported by Yuan et al. (24), showing that other BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins rendered kinase-inactive by mutation serve as allosteric transactivators. Alternatively, but not excluding the first model, it might be possible that BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y, which are less likely occupied by type I1/2 compounds, are further activated by drug-bound WT BRAF or RAF1, as both isoforms take up dabrafenib and encorafenib in the single-digit nanomolar range (62–64).

Next, we asked whether the high homodimerization propensity of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F could explain its dabrafenib resistance by negative allostery (19, 65) and introduced the R509H mutation, either singly or in combination with the AAE substitution, into this oncoprotein. Unexpectedly, these alterations did not restore dabrafenib sensitivity, suggesting that other mechanisms modulate dabrafenib affinity of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (fig. S11).

In search of an explanation for the varying properties of the analyzed BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, we noticed that BRAFΔNVTAP, BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, and BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y only differ in the amino acid residue at position 485 (fig. S1), with BRAFΔLNVTAP>F resembling the previously described point mutation L485F (41). Notably, while representing a smaller net deletion, BRAFdelinsFS also substitutes L485 by a phenylalanine residue, and the tyrosine introduced into BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y might entertain similar hydrophobic interactions. In BRAFL485F, F485 has been implicated to interact with F498, thereby creating a critical hydrophobic network that contributes to increased kinase activity and resistance to type I1/2 inhibitors, including dabrafenib (41, 66). As suggested by structural models of BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, this aromatic interaction could also be established in BRAFΔβ3-αC variants exhibiting an aromatic amino acid residue at position 485 (fig. S12A). Therefore, we tested whether replacing F498 by an alanine residue could abrogate the differences between BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (fig. S12, B and C). Unexpectedly, the F498A substitution strongly reduced the activity of BRAFΔNVTAP, although the proposed aromatic interaction of F498 cannot be established in this mutant as L485 remains preserved (fig. S12A). In addition, the moderate reduction of BRAFV600E activity upon F498A introduction suggests a broader and hitherto unrecognized role of F498 in BRAF activity extending beyond the previously proposed interaction with L485F. In contrast to BRAFΔNVTAP, pMEK levels of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F and BRAFdelinsFS were only mildly reduced, suggesting that the de novo–inserted aromatic amino acid residue of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F or BRAFdelinsFS could compensate for the loss of F498. In agreement with the model postulating an aromatic F485-F498 interaction (41, 66), the F498A substitution reduced the intrinsic dabrafenib resistance of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, albeit by only 50% (fig. S12, D and E). While our manuscript was in initial review, we identified a previously unidentified exon 12 in-frame deletion mutant, BRAFΔLNVT>F, in a melanoma case. This mutant provides an independent conformation for our hypothesis that aromatic amino acid residue substitutions of L485 play a central role in rendering BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants resistant to type I1/2 inhibitors. BRAFΔLNVT>F differs from the previously characterized type1/2 inhibitor–resistant mutants by its shorter net deletion of three amino acids (fig. S1). However, L485 was also substituted with a phenylalanine residue. As predicted from our analyses on BRAFΔβ3-αC variants with aromatic de novo amino acid insertions at position 485, BRAFΔLNVT>F was insensitive to dabrafenib. In contrast, naporafenib and sorafenib efficiently blocked the signaling output of BRAFΔLNVT>F (Fig. 5, D and H). In summary, all four BRAFΔβ3-αC variants with aromatic de novo amino acid insertions show intrinsic dabrafenib resistance.

Naporafenib blocks the proliferation of human cell lines expressing endogenous BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins

The well-defined heterologous HEK293T system provides a strong advantage when comparing BRAF oncoproteins for their signaling output and druggability as it allows the comparison of the various mutants in question without the interference by cell line–specific comutations—a problem that might arise when comparing multiple cell lines. A disadvantage of this approach, however, is the ectopic overexpression of the oncoprotein in question outside of its histological context. This is particularly important as the histological context, which is mainly defined by the ontogeny of the cancer cell and its tumor microenvironment, is responsible for the contrasting drug responsiveness of various BRAFV600E-driven tumor entities (67, 68). Therefore, we assayed the drug responsiveness of three cell lines derived from ovarian (OV-90), non–small cell lung (NCI-H2405), and pancreatic (BxPC3) carcinoma that harbored three distinct endogenous BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins, as we confirmed ourselves (fig. S13, A to C). Again, naporafenib and, as expected from its action downstream of BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins, trametinib suppressed colony growth in all cell lines by more than 90% (Fig. 6, A to L). In contrast, encorafenib was less effective in all three cell lines, while the effects of dabrafenib on colony growth differed between the cell lines with the BRAFΔNVTAP-expressing cell line OV-90 being the most sensitive. The high BRAF dependency of OV-90 is also reflected by the DepMap tool (https://depmap.org/portal/) that lists BRAF within the top 10 most essential genes for this but not the other two cell lines. Western blotting confirmed the successful but variable inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway in all three cell lines, with the OV-90 cell line again responding best to encorafenib and dabrafenib (Fig. 6, F to H, and fig. S14, A to C). BxPC3 displayed the highest BRAF levels of these three cell lines, which agrees with the reported tetrasomy of the BRAF-containing chromosome 7 (69). As type I1/2 inhibitor efficacy is modulated by the expression level of BRAF (70) and the ratio between its WT and mutant versions differing in drug affinity (63, 64), it should be also kept in mind that NCI-H2405 lacks a BRAFWT allele, while OV90 and BxPC3 contain BRAFWT and BRAFΔβ3-αC alleles (fig. S13, A to C).

Fig. 6. Encorafenib, dabrafenib, and naporafenib block the growth of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutant–expressing cell lines with varying efficacy.

(A) Cells were cultivated in the presence of trametinib (5 nM), encorafenib (0.5 μM), dabrafenib (1 μM), naporafenib (1 μM), or vehicle control (DMSO). OV-90, NCI-H2405, and BxPC3 cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet after 16, 21, or 18 days, respectively. (B to E) The colonized area was determined using ImageJ. Bar graphs show the colonized area of inhibitor-treated cells normalized to the area of those treated with vehicle control. Statistical analysis: means + SD, n = 3, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (F to H) Western blot analysis showing the effect of the applied RAFis on MEK/ERK phosphorylation in the three cell lines. Detection of HSP90 serves as loading control. The corresponding quantification of pMEK levels is shown in fig. S15 (A to C). (I to L) Heatmaps showing the antiproliferative effect of trametinib, encorafenib, dabrafenib, and naporafenib on BRAFΔβ3-αC mutant–expressing cancer cell lines. Following incubation with inhibitor or vehicle control for 96 hours at the indicated concentrations, the metabolic activity was measured by XTT assay and normalized to vehicle control (n = 3). (M) Antiproliferation IC50 values were calculated by nonlinear fitting using GraphPad Prism 9. Calculated fitted curves are shown in fig. S15 (D to G).

As naporafenib is still awaiting clinical approval, we asked whether sorafenib, a clinically extensively used type II inhibitor that has been crystalized with BRAFΔNVTAP (36), would yield similar effects (fig. S13, D and E). Four and ten micromolar sorafenib significantly reduced colony growth in all cell lines with endogenous BRAFΔβ3-αC mutations, and even 1 μM led to a slight but significant reduction in colony growth in OV-90 and NCI-H2405 cells. As these sorafenib concentrations are widely used in the field (28, 71, 72) and because peak plasma concentrations of up to 20 μM range were reported (73, 74), our data suggest that this clinically available type II inhibitor could be further explored for the treatment of tumors driven by BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins.

Next, we performed metabolic 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilid (XTT) assays to determine half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the three RAFi and trametinib in the three human cell lines with endogenously expressed BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins (Fig. 6, I to M, and fig. S14, D to I). Similar to the colony growth and Western blot assays, the calculated IC50 values and the heatmaps demonstrate the relatively uniform responses of all three human cell lines to trametinib and naporafenib, while those to the type I1/2 inhibitors encorafenib and dabrafenib varied considerably. Unexpectedly, we observed paradoxical metabolic activity in the pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line BxPC3 at high dabrafenib concentrations, which precluded us from determining an IC50 for this cell line. As this phenomenon was not observed in the other cell lines, we exclude an artifact caused by chemical interference between dabrafenib and XTT. In addition to trametinib and the various RAFi, the ERK inhibitor ulixertinib (75, 76) was similarly effective at clinically achievable concentrations in all three cell lines (fig. S14I).

Moreover, because BxPC3 expresses the BRAFΔVTAPTP>A variant, which was as efficiently inhibited as BRAFΔNVTAP by both type I1/2 inhibitors in the HEK293T system (Fig. 5), we expected that the antiproliferative effects on OV-90 and BxPC3 cells would be comparable. To further investigate why BxPC3 differed so drastically from OV-90, we analyzed the phosphorylation status of EGFR and AKT, as we suspected an up-regulation of metabolic processes by compensatory hyperactivation of these signaling elements, e.g., by relief from MEK/ERK-mediated negative feedbacks or cross-talk (55, 77–80). These analyses revealed two interesting differences between the three cell lines (fig. S14J). First, OV-90 lacked the prominent expression and autophosphorylation of EGFR observed in NCI-H2405 and BxPC3 cells. Second, BxPC3 exhibited high levels of AKT phosphorylated at the activating mTORC2 phosphorylation site S473 (81), which was further augmented by dabrafenib or naporafenib. This up-regulation might reflect the negative cross-talk between the ERK and AKT pathways that has been described for various cell types, including BxPC3 cells (80, 82). Thus, in addition to the aforementioned differences between the three BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins in terms of their RAFi sensitivity, differences in EGFR expression/activity and/or AKT activity could explain the increased sensitivity of OV-90 cells to the three RAFi and trametinib. Conversely, the unexpected mild-to-moderate effects of type I1/2 inhibitors on BxPC3 cells could be due to the high activity of the PI3K/AKT signaling axis and the relief of EGFR from negative feedback (78, 79). Nevertheless, how naporafenib achieves substantial inhibition across the three cell lines (Fig. 6L), despite promoting phospho-AKT levels as well, requires further study. Collectively, these data, and, in particular, the phenotype of BxPC3 cells, demonstrate that the comparison of human cell lines with similar alterations in the pathway of interest is confounded by alterations such as co-mutations or chromosomal aberrations specific to each cell line and potentially cell-of-origin–related differences in gene expression.

Given the efficacy of the type II compounds naporafenib and sorafenib across all BRAF∆β3-αC oncoproteins (Figs. 5 and 6 and fig. S8D), we combined them with the MEKi trametinib, which further increased the efficacy of these RAFi at nanomolar concentrations (Fig. 7, A to F). Notably, the sorafenib/trametinib combination has already been applied in the context of BRAF class III mutations (83) and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (84), while first clinical data on naporafenib/trametinib combinations have recently been published for NRAS-driven melanoma (85). We also tested whether the efficacy of naporafenib could be further improved by the HSP90i XL888, which shows clinical activity in combination with vemurafenib in melanoma (49, 86). In all three cell lines, however, XL888 exhibited a narrow range between not being additive to naporafenib and too toxic by itself to discern additive/synergistic effects with this RAFi (fig. S14, K to M). In summary, our analyses support the concept that the responsiveness of human cell lines expressing BRAF∆β3-αC oncoproteins toward dabrafenib and encorafenib is modulated by the details of the BRAF in-frame deletion and their cellular context. In contrast, type II inhibitors, the MEKi trametinib, and the ERKi ulixertinib all impair viability in a uniform manner. Moreover, because sorafenib and trametinib were approved more than 10 years ago and because naporafenib is currently in clinical phase 2 trials, our data highlight potential clinically realizable vertical combination therapies for BRAFΔβ3-αC-driven tumors.

Fig. 7. Trametinib enhances the efficacy of type II RAFi.

BRAFΔβ3-αC mutant–expressing cancer cell lines were incubated with naporafenib (A to C) or sorafenib (D to F) at the indicated concentrations, alone or combined with 1 or 8 nM trametinib, to explore the potential of vertical pathway inhibition. After 96 hours, the metabolic activity was measured by XTT assay and normalized to vehicle control. The metabolic activity in the absence of RAFis is indicated by dotted lines in the color of the respective trametinib concentration (dark blue, 1 nM trametinib; light blue, 8 nM trametinib). Graphs show the means + SD of three independent experiments. Nonlinear fitted curves were calculated using GraphPad Prism 9.

Confirmation of type II RAFi efficacy in patient-derived organoids

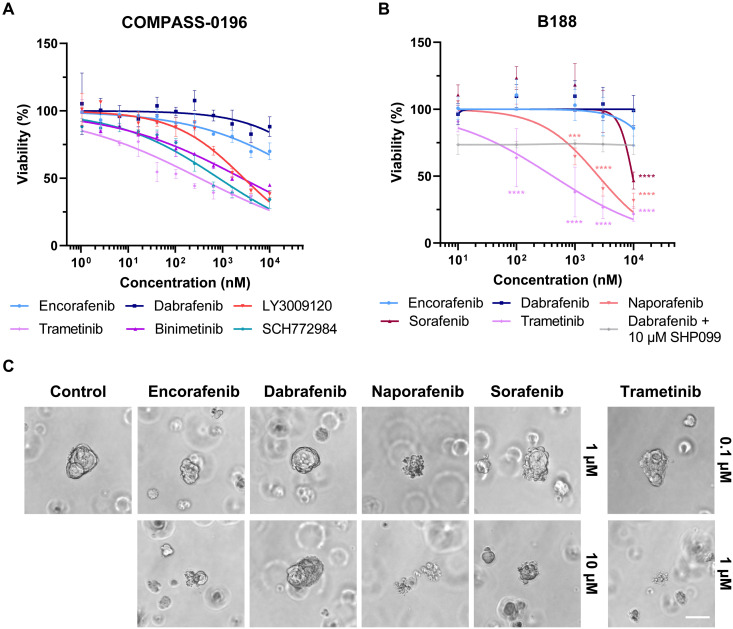

As the three cell lines investigated have been established more than two decades ago, we next screened patient-derived organoids (PDOs) or associated unpublished datasets available to us for BRAF exon 12 in-frame deletions. We identified two PDAC PDOs harboring BRAFΔNVTAP mutations and investigated their drug responsiveness. The first dataset was derived from the COMPASS-0196 (NCT-04469556) PDO that was already drug tested before we identified the efficacy of naporafenib on BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants. In this PDO, the type II RAFi LY3009120, the two MEKi binimetinib and trametinib, and the ERKi SCH772984 were highly effective in suppressing PDO growth, while dabrafenib and encorafenib were only effective at very high concentrations (Fig. 8A). The underlying molecular mechanism remains unclear at present, but the presence of an ERBB3G507R mutation, which is uncharacterized so far but is located in subdomain IV involved in dimerization control of this receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), and a slight copy number variation (CNV) gain in KRAS (four copies) might have contributed to the paradoxical action of dabrafenib.

Fig. 8. Type II RAFi like naporafenib suppresses the growth and viability of PDAC PDOs.

(A) COMPASS-0196 PDOs were treated with the indicated kinase inhibitors for 7 days. The viability was determined by CellTiter-Glo 3D assay and normalized to vehicle control. The graph shows the means + SD and calculated fitted curves of three independent experiments. (B) The viability of B188 organoids grown in the presence of the indicated inhibitors for 72 hours was determined using the CellTiter-Glo 3D assay and normalized to vehicle control (DMSO). Nonlinear fitted curves were calculated using GraphPad Prism 9. Statistical analysis: means + SD, n = 4 (dabrafenib + SHP099: n = 3), two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (C) Representative micrographs of inhibitor-treated B188 organoids right before performing the viability measurements shown in (B). Scale bar, 50 μM.

Given the aforementioned failure of LY3009120 in clinical trials and the data shown in Figs. 5 and 6, we generated another dataset of the B188 PDO using the type II RAFi naporafenib and sorafenib, the type I1/2 compounds dabrafenib and encorafenib, as well as the MEKi trametinib. Trametinib and also both type II RAFi potently suppressed the viability of the PDO at clinically achievable concentrations (Fig. 8, B and C). Similar to the COMPASS-0196 PDO, dabrafenib and also encorafenib only showed slight effects at very high concentrations. As this finding is in contrast to the dabrafenib sensitivity of BRAFΔNVTAP mutant OV-90 cells, we screened the next generation sequencing (NGS) data of the B188 PDO for potential resistance mechanisms. Notably, we identified a previously unidentified E138Q mutation in GNA13 (fig. S13C). Although this mutation represents a variant of unknown significance, RAS/ERK activation has been observed in cells overexpressing this heterotrimeric G protein subunit (87, 88). Consequently, one could envisage a paradoxical action of type I1/2 inhibitors. Alternatively, but not excluding these possibilities, it is possible that, in contrast to the simple OV-90 culture medium, the organoid media enriched with EGF and fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) could have contributed to paradoxical action of the type I1/2 compounds and therefore could have blunted drug responses in both PDO models. In that regard, we combined dabrafenib with an allosteric SHP2 inhibitor to lower physiological RAS signaling (Fig. 8B). Although this compound by itself lowered viability by 25%, we did not observe significant additive effects with dabrafenib. Thus, identifying these confounding factors of dabrafenib resistance represents a project beyond the current study. Nevertheless, our cell line and PDO data already show that the BRAF exon 12 genotype represents only one criterion for inhibitor choice. Even if a dabrafenib-sensitive mutant is encountered, the spectrum of co-mutations and/or the ground state of the signaling network, e.g., RTK expression levels, might critically modulate dabrafenib responses. This insight represents a strong encouragement for more comprehensive genomic profiling before therapy. Moreover, a switch to type II inhibitors should be considered if primary or secondary drug resistance phenomena are encountered during dabrafenib therapy (fig. S16).

DISCUSSION

As comprehensive mutational screening of the entire BRAF coding sequence becomes diagnostic routine, more alterations outside of the classical hotspot exons 11 and 15 are discussed in MTBs. We noticed an increase in enquiries and literature concerning BRAF exon 12 alterations, most notably Δβ3-αC in-frame deletions (31, 32, 34, 39, 89). For example, 3.15% of KRAS WT PDACs analyzed in a multicenter study carried such alterations (90). Depending on the cohort, Chen et al. (35) reported a prevalence between 2.3 and 7.1% in KRAS WT pancreatic carcinoma. Considering the 458,918 new cases of pancreatic carcinoma reported in 2018 (91) and that ⁓5 to 10% of these lack KRAS alterations, we estimate that several thousand patients of this disease group alone will be potentially diagnosed with druggable BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants annually. We expect that more exon 12 variants will be found in the future, and here, we extend their spectrum by identifying and characterizing two previously unidentified mutants, BRAFdelinsFS and BRAFΔLNVT>F. The BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants originally identified within human neoplasms have been recently observed in 19% of canine urothelial carcinoma (92), highlighting the possibility that studying their pathobiology and druggability will bridge between human and veterinarian oncology.

From our experience, two major questions are recurrently raised in MTBs regarding BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants. The first concerns their general relevance as oncogenic drivers, in particular, as activity correlates with deletion length (36, 37). So far, all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants turned out to be very potent oncogenic drivers and BRAFdelinsFS and BRAFΔLNVT>F, despite their shorter deletion, are no exception. On the basis of our functional analyses (Fig. 2, A and B) and previous studies (35, 66), we posit that all BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins owe their high signaling potential to their high dimerization propensity that stems from their αC helices locked in the IN position. In that regard, BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins imitate a conformation into which WT RAF proteins are transferred during dimerization. Recent structural modeling proposes that dimerization breaks protomer-internal hydrophobic interactions mediated by so-called π-π stacking and replaces them with intermolecular π-π bonds formed between aromatic amino acid residues in both protomers (15). These interactions reorientate the αC helix and the HRD motif, leading to kinase activation through R-spine formation (41, 93). Consequently, the high dimerization propensity of BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins promotes full kinase activation and MEK phosphorylation, which is facilitated by dimeric RAF (24).

The second and even more pressing question is which targeted therapy compounds are the most appropriate for treating tumors carrying BRAF exon 12 in-frame deletions. Given the high activity of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, tumors driven by these oncoproteins qualify for a treatment regimen involving MEKi, as also reflected by therapeutic responses of several PDAC cases (31, 34) and a Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (94). In BRAFV600E-driven tumors, however, MEKi are usually combined with BRAFV600E-selective drugs to achieve more sustainable therapeutic outcomes (95). On the basis of pathway topology, it can be expected that this concept is also applicable to other cancers driven by highly active non-V600E BRAF mutants. Moreover, the emerging concept of low-dose vertical pathway inhibition (51, 96) highlights the necessity to identify compounds effectively and directly inhibiting BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins for future treatment regimen. Here, we show that oncogenic signaling by all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants we investigated can be efficiently inhibited by the type II RAFi naporafenib and sorafenib. As these drugs are in clinical trials and use, respectively, our data might inform decisions concerning the inclusion of patients into clinical trials involving naporafenib and other emerging third-generation RAFis, or to recommend off-label and compassionate use of sorafenib. As suggested previously (35, 36) and as extended by fig. S8D, other type II inhibitors in (pre)clinical development might represent attractive alternatives as well.

The varying efficacy of the type I1/2 inhibitors vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib against BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants represents an interesting aspect from both a clinical and a basic kinase biochemistry perspective. We confirm previous observations that vemurafenib is ineffective against BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (35, 36), while encorafenib, an inhibitor not yet tested on these oncoproteins, shows limited and probably insufficient activity. In line with case reports demonstrating therapeutic responses of two BRAFΔNVTAP-positive PDACs (89, 97) and an LCH (98) to (initial) dabrafenib monotherapy, we [and (35)] show that dabrafenib strongly suppresses BRAFΔNVTAP-driven MEK/ERK phosphorylation in OV-90 cells. While our manuscript was under review, another case report presented an at least 18-month-lasting partial response of a melanoma containing a similar BRAFΔNVTAP mutant to dabrafenib/trametinib combination therapy (99). As there is now more than a decade of clinical experience with dabrafenib, the efficacy of this compound against BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins is of particular interest. Chen et al. (35), however, observed that dabrafenib only had minimal effects on MEK/ERK phosphorylation in NCI-H2405 (BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y) and BxPC3 (BRAFΔVTAPTP>A) cells. We reproduced these findings (Fig. 6G) and decided to use our heterologous HEK293T model, which does not harbor the caveat of distinct genetic and histological backgrounds, as it is the case for cell lines, to clarify whether the difference in dabrafenib sensitivity is linked to the individual deletion type. Only BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFΔVTAPTP>A displayed dabrafenib sensitivity (Fig. 5F). As BRAFΔLNVTAP>F showed a significantly higher propensity for homodimerization than BRAFΔNVTAP (Fig. 3, A and B), it is tempting to attribute the observed dabrafenib resistance of the former to increased dimerization and negative allostery (19). In that regard, Foster et al. (36) demonstrated that, in contrast to dabrafenib, vemurafenib induces and requires a greater αC helix shift during inhibitor accommodation that cannot be provided by BRAFΔNVTAP because of the sterical constraints imposed by the in-frame deletion. Therefore, the dabrafenib-resistant BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y, BRAFΔLNVT>F, and BRAFdelinsFS mutants (Fig. 5, B, F, D, and H), which have not yet been investigated for their impact on αC helix flexibility, might differ from BRAFΔNVTAP in such a way that their deletions, which are accompanied by insertions of a bulky aromatic residue, preclude dabrafenib binding by negative allostery. The aforementioned study by Zhang et al. (15), who describe the critical role of hydrophobic interactions occurring during RAF activation, proposes that dimerization tightens the adenosine triphosphate–binding pocket and thereby interferes with inhibitor accommodation by steric clashes in which minute differences between the various RAFi might have large effects.

Another recent study, however, showed that the binding affinities of the dimer-favoring type II inhibitor naporafenib and dabrafenib to chemically enforced BRAFV600E dimers are comparable, demonstrating that increased dimerization is insufficient to confer resistance to type I1/2 inhibitors (25). Moreover, the inability of the R509H substitution, alone or combined with the AAE mutation, to improve dabrafenib sensitivity in BRAFΔLNVTAP>F suggests that other mechanisms decide drug accommodation (fig. S11). For example, the mechanism for dabrafenib resistance could be explained by the hydrophobic network that underlies the formation of the R-spine (15, 41). In that respect, we noted that BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y, BRAFΔLNVT>F, and BRAFdelinsFS substitute L485 for a bulky aromatic residue that could restrict dabrafenib binding, while the in terms of deletion length similar BRAFΔVTAPTP>A mutant remained dabrafenib sensitive. This concept is supported by a study proposing that the introduced phenylalanine of the BRAFL485F point mutant forms a hydrophobic network with F498, which in turn stabilizes the R-spine and precludes type I1/2 inhibitor binding (66). Consequently, loss of F498 should break dabrafenib resistance. The F498A substitution reduced the dabrafenib resistance of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F by 50% (fig. S12, D and E). This finding supports this model but also suggests that other mechanisms contribute to the dabrafenib resistance of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F, BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y, BRAFΔLNVT>F, and BRAFdelinsFS. Therefore, the insertion of de novo hydrophobic amino acids at the in-frame deletion junction might generate a distinct mutation-specific hydrophobic network or modify the already recognized ones (15) and thereby increase dimerization propensity, activity, and type I1/2 RAFi resistance. This represents an interesting area for future studies. Moreover, as the spectrum of tumor-associated BRAFΔβ3-αC will probably expand in the near future, we will learn whether there is a selective pressure for maintaining or even replacing L485 with bulky hydrophobic residues to increase oncogenic potential and type I1/2 inhibitor resistance. By revisiting the deletion walking experiment by Foster and colleagues (36), we realized that their data also support the critical role of L485 as in-frame deletions omitting L485 hardly increased the MEK phosphorylation potential of BRAF. The analysis of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F crystal structures, which are not available to date, could potentially reveal the mechanisms conferring resistance against type I1/2 RAFis. Close inspection of the orientation and potential intramolecular interactions of F485 of BRAFΔLNVTAP>F compared to those of L485 of BRAFΔNVTAP will be key. Although the precise mechanism(s) of dabrafenib resistance need to be addressed in separate studies, our data already demonstrate that BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins significantly differ in their sensitivity toward this compound. Thus, extra caution must be applied when experiences from individual case reports with marked responses for one BRAFΔβ3-αC mutant to dabrafenib are used as evidence to tailor a therapy for an oncoprotein with a seemingly highly similar but distinct alteration.

We also obtained previously unknown insights into the requirements of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants for oncogenic signaling. A major open question was whether BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants signal as monomers or (constitutive) dimers (24, 35–37). In hindsight, this controversy was partly caused by the fact that the various laboratories investigated distinct BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants and used the R509H mutation as a tool to measure dimer dependency. In that regard, the R509H mutation reliably blocks allosteric transactivation, a process from which BRAFV600E and potentially other high-activity mutants are largely exempted (9). However, while the R509H mutation strongly reduces homodimer affinity, it does not completely abrogate dimerization, and only the additional introduction of the AAE mutation really renders almost all BRAF molecules monomeric, at least according to coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Thus, the suitability of the R509H mutation to discriminate between dimeric and monomeric BRAF needs to be taken with caution, in particular, within the context of mutants with high dimerization propensity (24). Therefore, we revisited the dimerization potential of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants and demonstrate that they form very stable homodimers with a significantly higher efficiency than BRAFV600E. On the basis of these data and work by others on BRAFΔNVTAP and other in-frame deletion mutants (24, 35), we conclude that BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants signal as dimers because they lose their high MEK phosphorylation and dimerization potential upon the simultaneous introduction of the R509H and AAE mutations. We interpret the relative resistance of the BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants toward the R509H mutation by the aforementioned structural peculiarities of these oncoproteins that, due to their special αC helix conformation, lock them in an active state. Thereby, they become independent of allosteric transactivation that is critical for other BRAF gain-of-function mutants (3). Like BRAFV600E, but unlike other BRAF oncoproteins (18, 40), Δβ3-αC mutants signal independent of D594FGLATV600KS-motif phosphorylation, which further supports the notion that the in-frame deletion constitutively induces the active αC-helix-IN/DFG-IN/R506-IN conformation. In all these respects, BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants resemble the canonical class I mutant BRAFV600E, although their varying sensitivity toward type I1/2 inhibitors argues against this categorization. Thus, these oncoproteins might constitute a class of their own. Another notable parallel to BRAFV600E is the ability of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants to form large multiprotein complexes. We demonstrated previously that these large multiprotein complexes reflect BRAF activity as endogenous BRAFV600E shifts to the small complex upon vemurafenib treatment (23). As we had demonstrated that the large BRAFV600E-containing complex is enriched with the HSP90/CDC37 complex and because BRAFV600E shows a specific vulnerability toward HSP90 inhibition (47, 48, 86), we investigated the association of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants with HSP90. BRAFdelinsFS recruits HSP90 to a similar extent as BRAFV600E, while recruitment of HSP90 to BRAFΔNVTAP was even more pronounced. Unexpectedly, BRAFΔLNVTAP>F recruits less of this chaperone. In line with this result, BRAFΔNVTAP and BRAFV600E become unstable in the presence of the clinically trialed HSP90 inhibitor XL888 and present with a significantly shorter half-life. Commensurate with its lower HSP90 recruitment propensity (like BRAFWT), BRAFΔLNVTAP>F displays higher overall stability in our tet-washout experiments and in the presence of XL888. It is tempting to speculate that the very high homodimer formation shown by BRAFΔLNVTAP>F stabilizes this oncoprotein and alleviates the need for being chaperoned by HSP90/CDC37.

Two recent studies might provide additional explanations for the contrasting HSP90 binding behavior of BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants (100, 101). Using cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM), it was shown that the HSP90/CDC37 complex binds to the C-lobe of the kinase domains of BRAF and RAF1, while the latter, which shows higher affinity to the chaperone complex, also binds to the N-lobe and in the vicinity of the Δβ3-αC segment (101). This interaction requires the unfolding of the N-lobe, which remains folded in the context of BRAFWT but becomes unstructured and more RAF1-like in the context of the specific conformation of BRAFV600E imposed by the aforementioned salt bridge linking N- and C-lobes. This explains why BRAFV600E tightly interacts with this chaperone (23) and is exquisitely sensitive to HSP90 inhibition (47, 48). Thus, deletion of Δβ3-αC segment might restructure the BRAF N-lobe in such a way that it becomes an interaction point for the HSP90/CDC37 complex. This concept would explain why several but not all BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants tightly copurify with HSP90/CDC37 and how specific details of the in-frame deletion modulate this interaction. The BRAF∆LNVTAP>F mutant and, potentially due to structural similarities, BRAFΔLNVTAP>Y represent a notable exception for the increased HSP90 binding observed for other BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins (Fig. 3, A, B, and D). On the basis of very recent insights from cryo-EM and deuterium exchange/MS experiments showing that the HSP90/CDC37 complex recognizes RAF molecules with N and C loop unfolded (101–103) and the notion that R-spine formation–induced conformational changes are a prerequisite for efficient N- and C-loop compaction and hence DIF-mediated dimerization (15, 17, 93), we posit that it is the high dimerization propensity of BRAF∆LNVTAP>F that precludes its interaction with the chaperone complex. This hypothesis is supported by our experiment in which the R509H and AAE mutations increased HSP90 binding of BRAF∆LNVTAP>F (Fig. 3D). Although this represents an area for future studies, our present data nevertheless suggest that inhibitors targeting specific HSP90/CDC37 complexes could be useful to treat tumors driven by other BRAFΔβ3-αC mutants, e.g., to enhance the efficacy of RAFi. Therefore, our study highlights the so-far unrecognized functional diversity of BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins and recommends that precision and attention to molecular details must be applied when potentially effective but highly discriminating type I1/2 inhibitors like dabrafenib are considered. Encouraging responses with dabrafenib were observed in individual PDAC cases of BRAFΔNVTAP-driven tumors (89, 97) and in the OV-90 cell line containing the same in-frame deletion (Fig. 6, A, D, G, M, and K). However, two BRAFΔNVTAP-containing PDAC PDOs hardly responded to clinically meaningful dabrafenib concentrations, possibly because of private co-mutations as discussed above. Likewise, the BxPC3 cell line containing the dabrafenib-sensitive BRAFΔVTAPTP>A mutant appeared less BRAF addicted, probably because of its high pAKT levels. Thus, our data suggest an algorithm for targeted therapy recommendations (fig. S16) based on structural differences predicting intrinsic dabrafenib sensitivity/resistance and based on private comutations and/or expression levels of signaling elements modulating dabrafenib responsiveness. Last, our data provide impetus for the clinical development of safe and effective pan-RAFis that block the activity of all BRAFΔβ3-αC oncoproteins, irrespective of their intrinsic dabrafenib sensitivity or the private signaling network of the tumor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient

The patient had given written informed consent for molecular analysis (whole-genome/exome and RNA sequencing, DNA methylation profiling) within NCT/DKTK MASTER, a prospective observational and registry study approved by the Ethics Committee of Heidelberg University (protocol number S-206/ 2011) in which patients with advanced rare cancers and patients diagnosed with advanced common cancers at an unusually young age undergo a standardized precision oncology workflow, including clinical decision-making in a multi-institutional MTB (38, 104).

Cell lines and genomic DNA analysis

Plat-E cells were provided by T. Kitamura (University of Tokyo). HEK293T cells were provided in-house by A. Hecht. Plat-E, HEK293T cells, and pBABE-puro-CreERT2-transduced BraffloxE12/floxE12 MEF, which were generated in-house and are immortalized by simian virus 40 large T antigen expression (9), were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (4.5 g/liter glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, penicillin (200 U/ml), and streptomycin (200 μg/ml). OV-90 and NCI-H2405 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. BxPC3 cells were a gift of S. Diederichs (University Medical Center Freiburg). These three cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, penicillin (200 U/ml), and streptomycin (200 μg/ml) and were authenticated by genomic DNA (gDNA)–based PCR analysis confirming the presence of the BRAF mutations previously reported for these cell lines (35, 36). To this end, gDNA was extracted using standard protocols and used as template for a PCR using Phusion polymerase (NEB) and oligonucleotides matching to introns 11 (5′- GGAGGATCCCCATGGAACAAACAAGGTTG-3′) and 12 (5′- GGAGAATTCCCACCTCTAAATGTATTCTG-3′) of BRAF. PCR amplicons were subcloned into pSC-A (Stratagene) for further analysis (fig. S12, A to C). Absence of mycoplasma was confirmed by PCR (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany).

PDO establishment, culture, and drug tests

The COMP-196 PDO was identified within a cohort of PDAC PDOs established at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Living Biobank (https://pmlivingbiobank.uhnresearch.ca/) from patients enrolled in the COMPASS trial (105, 106) and using procedures previously described in detail for xenograft-derived organoids (107). In brief, percutaneous core biopsy tissue from a liver metastasis was minced and dissociated in 1 ml of advanced DMEM (adDMEM)/F12 with 100 μl of Liberase TH (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 μM Y-27632 at 37°C for 15 min. Cell pellets were washed with adDMEM/F12, counted, and plated in Matrigel with modified human organoid medium [adDMEM/F12, 20% (v/v) Wnt-3a conditioned media, 30% (v/v) R-Spondin1 conditioned media, 1× B27, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 10 mM Hepes, antibiotic-antimycotic (100 U/ml), 1 mM nicotinamide, 1.25 mM N-acetyl cysteine, 10 nM gastrin I, hNoggin (100 ng/ml), FGF10 (100 ng/ml), EGF (50 ng/ml), 0.5 μM A 83-01, 10 μM Y-27632, and 2.5 μM CHIR-99021]. For drug tests, domes were dissolved and passaged in TrypLE (Gibco) for 30 to 60 min and counted in trypan blue. Cells were seeded in 10 μl of Matrigel in a 384-well plate at 1000 cells per well overlain with 40 μl of human organoid media (day 1). After 24-hour recovery, drugs were added using a Tecan D300e dispenser (day 2). Viability was measured using Cell Titre Glo 3D after 1 week (day 8).

The B188 PDO was identified within a cohort of pancreatic carcinoma PDOs established at the University Medical Centre Freiburg, Germany. Informed consent was obtained from patients for the establishment and use of three-dimensional (3D) organoid cultures from human pancreatic cancer tissue samples. Sampling was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Freiburg Medical Center (126/17; 28 March 2017). Surgery was performed at the Department of General and Visceral Surgery of the University Hospital Freiburg for proven or suspected pancreatic cancer. Organoid derivation and cultivation protocols were adapted from previous publications (108, 109). In brief, tissue samples were minced into small fragments and digested in 3 ml of complete collagenase digestion buffer [1× human complete feeding medium (COM), Collagenase Crude Type XI (5 mg/ ml; Sigma-Aldrich), 10.5 μM Y-27632, and deoxyribonuclease (DNAse) (10 μg/ml)]. COM consists of 1× HuWa medium [1× adDMEM/ F-12, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.2 to 7.5), 1× GlutaMAX supplement (all three from Gibco), and Primocin (100 μg/ml; InVivoGen)], 1× Wnt3a-conditioned medium or Afamin/Wnt3a-conditioned medium, 1× R-Spondin1–conditioned medium, 1× B27 supplement (Gibco), 10 mM nicotinamide, 1.25 mM N-acetylcysteine (both from Sigma-Aldrich), Plasmocin (2.5 μg/ml; InVivoGen), hEGF (50 ng/ml), hFGF10 (100 ng/ml), 10 nM hGastrin I (all three from PeproTech), 500 nM A 83-01 (TOCRIS), and 10.5 μM Y-27632 (Sigma-Aldrich).

In total, two incubation steps in a rotating incubator were performed at 37°C for 15 min. After each incubation, the digested tissue was manually triturated 10 to 20 times, and the supernatant of both fractions was centrifuged at 4°C, 200g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in 2 ml of ACK lysing buffer (Gibco), incubated for 2 min, and spun again. Subsequently, the cells were washed once with HuWa medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich). The cell pellet was resuspended in an adequate amount of Matrigel (8 mg/ml; Corning). New domes with 25 μl of Matrigel each were made and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 15 to 20 min. Thereafter, 500 μl of Complete Organoid Medium with Wnt (COM-Wnt) or Wnt-Afamin (COM-W/A) supplemented with 10.5 μM Y-27632 was added. PDOs were grown 6 to 12 days at 37°C, 5% CO2 and checked every third day. NGS sequencing leading to the identification of the BRAFΔNVTAP mutation was performed at University Spital Zürich, Molecular Pathology department (sequencing type, FoundationOne CDx).

To passage PDOs, two Matrigel domes were pooled and dissolved in 500 μl of ice-cold cell recovery solution (CRS). Subsequently, the suspension was incubated for 30 min on ice, inverting the tube every 10 min. The cells were pelleted, and the CRS was discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of TrypLE Master mix [1.5 ml of 1× TrypLE Express Enzyme (Gibco), 0.5 ml of HuWawith, 0.1% BSA, 10.5 μM Y-27632, and DNase (10 μg/ml)]. The cells were incubated in a rotating incubator at 37°C and 180 rpm for 15 min. Cells were pelleted again, and the supernatant was aspirated. The cell pellet was resuspended 20 times in ice-cold HuWa medium with 0.1% BSA to mechanically dissociate the PDOs. Following a last centrifugation step, cells were resuspended in Matrigel, and new domes (25 μl of Matrigel each) were spotted into tissue culture wells incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 15 to 20 min before being overlain with 500 μl of COM-Wnt or COM-W/A supplemented with 10.5 μM Y-27632. Occasionally, an aliquot of cells was used to isolate gDNA as described above to confirm the presence of driver mutations.