Abstract

Introduction

hTERT (human telomerase reverse transcriptase) is a catalytic subunit of the enzyme telomerase and has a role in cell proliferation, cellular senescence, and human aging.

Materials and methods

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the expression and significance of hTERT protein expression as a prognostic marker in different histological subtypes of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs), including 46 embryonal carcinomas, 46 yolk sac tumors, 38 teratomas, 84 seminomas as well as two main subtypes of seminomas and non-seminomas using tissue microarray (TMA) technique.

Results

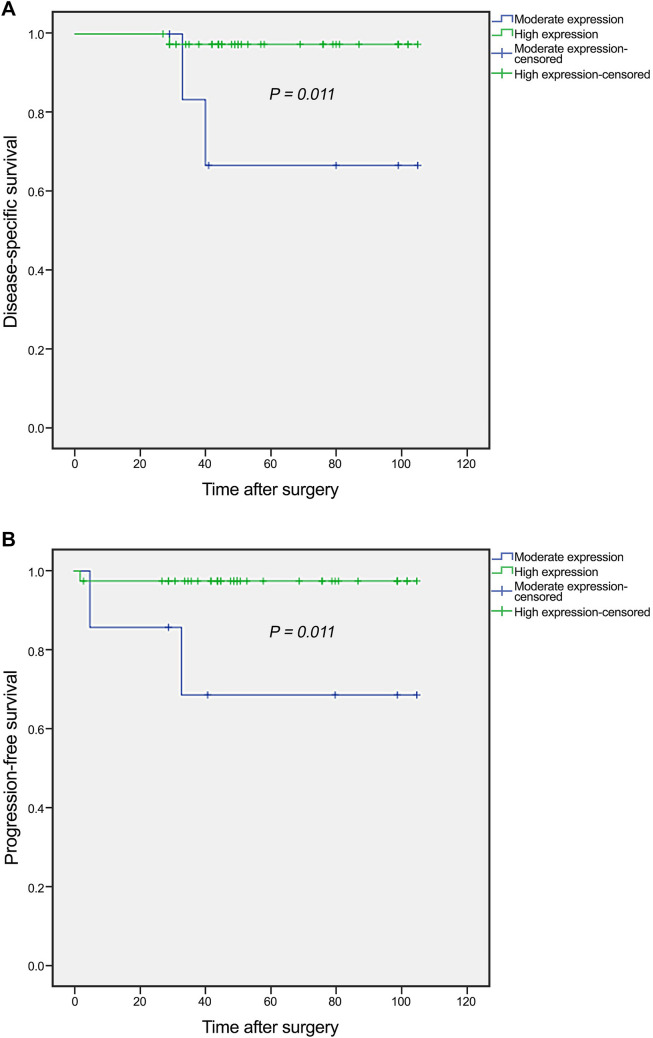

The results showed that there is a statistically significance difference between the expression of hTERT and various histological subtypes of TGCTs (P < 0.001). In embryonal carcinoma, low level expression of hTERT protein was significantly associated with advanced pT stage (P = 0.023) as well as tunica vaginalis invasion (P = 0.043). Moreover, low level expression of hTERT protein was found to be a significant predictor of worse DSS (log rank: P = 0.011) and PFS (log rank: P = 0.011) in the univariate analysis. Additionally, significant differences were observed (P =0.021, P =0.018) with 5-year survival rates for DSS and PFS of 66% and 70% for moderate as compared to 97% and 97% for high hTERT protein expression, respectively.

Conclusion

We showed that hTERT protein expression was associated with more aggressive tumor behavior in embryonal carcinoma patients. Also, hTERT may be a novel worse prognostic indicator of DSS or PFS, if the patients are followed up for more time periods.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00432-020-03319-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: hTERT, Protein expression, Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs), Embryonal carcinoma, Tissue microarray (TMA)

Background

Testicular cancer is the most common solid malignancy among young men, aged 20–45 years and represents 1.5% of male neoplasms and 5% of urologic tumors (Albers et al. 2018; Stephenson et al. 2019). The incidence of testicular cancer has significantly increased approximately 1.2% per year over the past decade (Ibrahim and Sun 2019). The highest incidence rate was observed in Europe (7.2–8.7) and the lowest incidence in Africa (0.3–0.6) and Asia (0.4–1.7) (Farmanfarma et al. 2018). In the United States, it is estimated that, there will be 9610 new cases of testicular cancer and 440 deaths during 2020 (Siegel et al. 2020). Moreover, the incidence rates of testicular cancer are predicted to rise in 21 of 28 European countries over the period 2010–2035 (Znaor et al. 2019).

The most frequent neoplasms of the testis is testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) which accounts for about 90–95% of all testicular tumors (Rajpert-De Meyts et al. 2018). In the current classification of testicular cancer, based on the recent restructuring of terminology recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) 2016 classification, TGCTs are divided into two main categories: GCT derived from germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) and GCT unrelated to GCNIS. GCNIS are classified as seminoma and non-seminomatous GCT or NSGCT. NSGCT includes embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, teratoma, choriocarcinoma, and mixed germ cell tumors (Moch et al. 2016).

Currently, there are no biomarkers for the early detection of TGCTs, which contributes to the delayed diagnosis. There are a set of serum tumor biomarkers presently available, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) which should be measured prior to any treatment such as orchiectomy in a man with a solid mass in the test which is suspicious for malignant neoplasm. However, these markers are proper for diagnostic and have low accuracy and low sensitivity when used as prognostic and predictive markers (Leão et al. 2019). Investigations have shown that although TGCTs are highly treatable and respond well to cisplatin, some patients are troubled by side effects and long-term toxicities of their treatment, and also some tumors do not respond to treatment (Fung et al. 2015; Oldenburg 2015; Richie 2006). Therefore, to decrease morbidity of treatment and improvement of therapies, identification of the new molecular markers is vital.

Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase that synthesizes telomeric DNA sequences, (TTAGGG) n, and adds it to the 3′ end of telomeres. Telomeres protect the end of the chromosome from DNA damage hence preventing shortening and maintaining telomeres. Telomerase consists of two essential components and associated protective proteins, of which functional RNA component called human telomerase RNA molecule (hTR) or hTERC serves as a template for telomeric DNA synthesis; the other is a catalytic protein, human telomerase reverse-transcriptase (hTERT) with reverse transcriptase activity (Dahse et al. 1997). Investigations have shown that most human normal somatic cells do not have significant levels of telomerase activity. However, embryonic stem cells and majority of human tumors exhibit high telomerase activity and adult tissue stem cells are potentially able to up-regulate telomerase after activation (Hiyama and Hiyama 2007; Khattar et al. 2016; Wright et al. 1996).

hTERT is necessary for telomerase activity, so that overexpression of hTERT is accompanied by increased telomerase activity (Blackburn 2005). In addition, hTERT is essential for the maintenance of telomere length, chromosomal stability, and cellular immortality (Cong and Shay 2008). A number of studies have demonstrated that increased expression of hTERT was associated with a poor prognosis in solid tumors, including lung cancer (Lu et al. 2004; Marchetti et al. 2002), oral squamous cell carcinoma (Chen et al. 2007), bladder cancer (Zachos et al. 2009), and clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) (Saeednejad Zanjani et al. 2019a). However, we could not find any data in literature regarding hTERT protein expression patterns, particularly by immunohistochemistry (IHC), and its association with clinicopathological characteristic and survival outcomes in patients with TGCTs.

The present study was designed for the first time to investigate the expression levels and potential prognostic role of hTERT protein expression in a series of TGCTs tumor samples, including embryonal carcinomas, yolk sac tumors, teratomas, and seminomas using IHC method on tissue microarray (TMA) slides. We, then, classified hTERT protein expression into seminoma and non-seminomatous GCT. This may help determine the potential utility of this biomarker in the targeted therapy of TGCTs.

Materials and methods

Patients and sample collection

A total of 191 paraffin-embedded tissues from TGCTs tumor samples were collected from the Hasheminejad Hospital, a major referral university-based urology–nephrology center in Tehran, Iran, during 2011–2017. No patients were treated with any relevant chemotherapy, radiotherapy or immunotherapy before surgery. These samples comprised various subtypes of TGCTs, including embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and seminoma. Some of these samples were pure and the others were a mixture of the mentioned histological subtypes. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides and medical archival records were retrieved to obtain clinicopathological characteristic including age, tumor size (maximum tumor diameter), pT stage, venous invasion (VI), GCNIS, rete testis involvement, hilum involvement, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte, epididymis involvement, tunica vaginalis and tunica albuginea invasion, spermatic cord and spermatic cord margin invasion, scar, tumor necrosis, levels of serum tumor markers, distant metastasis and tumor recurrence. Moreover, 21 benign tumor samples, including leydig cell tumor, epidermoid cyst, cavernous hemangioma, and adenomatoid tumor as well as 67 adjacent normal tissues were included to compare the expression levels of hTERT marker in a range of tissue specimens. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was defined as the time from radical orchiectomy to the date of death related to the patient’s cancer. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the interval between the primary surgery and the last follow-up visit if the patient showed no evidence of disease, recurrence or metastasis. The stage was defined based on the pTNM classification for TGCTs (Magers and Idrees 2018).

TMA construction

The H&E slides were consulted to select and mark the most representative areas in different parts of the tumor by one experienced pathologist. The TMA recipient blocks were constructed by a TMA instrument (Minicore; Alphelys, France). In this study, three cores were punched for each histological subtype and then evaluated and scored individually. Previous validation studies have shown that three cores are highly representative for the whole sections (Jourdan et al. 2003; Langer et al. 2006). Then, 4-mm sections were cut from the completed array blocks and transferred to adhesive slides. Next, TMA blocks were constructed in three copies for each specimen.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for evaluating the expression of hTERT protein

Briefly, all TMA sections were dewaxed and rehydrated by xylene and graded ethanol treatment. Endogenous peroxides and non-reactive staining were blocked with 3% H2O2 for 20 min at room temperature. After washing the tissue sections three times, antigen retrieval was performed by immersing the tissues in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min in an autoclave. The tissue sections were incubated with primary antibody, anti-telomerase reverse transcriptase antibody (ab183105, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) dilution of 1/500, overnight at 4 °C. Moreover, for isotype control, rabbit immunoglobulin IgG (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used at a dilution of 1/500. TMA slides were then incubated with anti-rabbit/anti mouse Envision (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) as a secondary antibody for 30 min. Staining patterns were visualized by exposure to 3, 30-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin to visualize the antigen (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Finally, the slides were dehydrated in alcohol, cleared in xylene, and mounted for examination. Human tonsillar tissue was used as a positive control, and the replacement of the primary antibody with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) wash buffer was applied as the negative control for confirming the nonspecific bindings of secondary antibody.

Scoring system of TMA slides

Immunohistochemical staining of hTERT was independently evaluated by two pathologists (MAa & MAb) who were blinded to the pathological characteristics and patients’ outcomes. A consensus was obtained for all samples. The intensity of staining was scored by applying a semiquantitative system, ranging from negative to strong as follows: 0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong. The percentage of positive cells was categorized according to the positive tumor cells as follows: Group 1, less than 25% positive cells; Group 2, 25–50% positive cells; Group 3, 51–75% positive cells; and Group 4, more than 75% positive cells. The histochemical score (H-score) was obtained by multiplying the intensity score by the percentage of positive cells, which yielded a range from 0 to 300. The mean H-score values of three cores were calculated as final scores. In this study, H-score was classified into three groups: 0–100 as group 1 (low expression), 101–200 as group 2 (moderate expression), and 201–300 as group 3 (high expression).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM Corp, USA) was used to analyze the data. We reported the categorical data by N (%), valid percent and quantitative data as follows: mean (SD) and median (Q1, Q3). Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests were run for pairwise comparison between groups. Moreover, Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation tests were employed to analyze the significance of association and correlation between hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological parameters. DSS and PFS curves were drawn adopting the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test was performed to compare the estimated curves between groups with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied to determine which variables affected DSS or PFS. Variables that significantly affected survival in univariate analysis were included in multivariable analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

From 191 cases, some of them were pure and the others were in combination with embryonal carcinoma, seminoma, yolk sac tumor, and teratoma which were as follows: embryonal carcinoma (5 pure, 41 mixed), yolk sac tumor (2 pure, 44 mixed), teratoma (8 pure, 30 mixed), and seminoma (64 pure, 20 mixed). In this study, we investigated each histological subtypes of TGCTs separately which comprised 46 embryonal carcinomas, 46 yolk sac tumors, 38 teratomas, and 84 seminomas. Then, we continued the analysis based on classification to seminoma and non-seminomatous GCT. The patients’ clinicopathological characteristic for samples from the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients and tumor pathological characteristic of histological subtypes of TGCTs and benign tumors

| Patients and tumor characteristics | Embryonal carcinoma N (%) | Yolk sac tumor N (%) | Teratoma N (%) | Seminoma N (%) | Benign tumors N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | 46 | 46 | 38 | 84 | 21 |

| Mean age, years (range) | 29 (16–59) | 28 (1–59) | 25 (1–45) | 33 (19–79) | 29 (15-55) |

| ≤ Mean or Median age | 26 (56.5) | 25 (54.3) | 19 (50.0) | 47 (56.0) | 11 (52.4) |

| > Mean or Median age | 20 (43.5) | 21 (45.7) | 19 (50.0) | 37 (44.0) | 10 (47.6) |

| Mean tumor size (cm) (range) | 4 (1.5–11.5) | 5 (1-15) | 5 (1-15) | 5 (1-20) | 2 (1-6) |

| ≤ Mean | 46 (100.0) | 28 (60.9) | 38 (100.0) | 53 (63.1) | 16 (76.2) |

| > Mean | 0 (0.0) | 18 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (36.9) | 5 (23.8) |

| Primary tumor (PT) stage | |||||

| pT1 | 28 (60.9) | 31 (67.4) | 27 (71.1) | 55 (65.5) | 1 (4.8) |

| pT2 | 15 (32.6) | 12 (26.1) | 4 (10.5) | 24 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| pT3 | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not classified | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (18.4) | 1 (1.2) | 20 (95.2) |

| Venous invasion (VI) | |||||

| Present | 18 (39.1) | 14 (30.4) | 4 (10.5) | 23 (27.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Absent | 28 (60.9) | 32(69.6) | 34 (89.5) | 61 (72.6) | 21(100.0) |

| Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) | |||||

| Present | 40 (87.0) | 39 (84.8) | 26 (68.4) | 63 (75.0) | 2 (9.5) |

| Not identified | 6 (13.0) | 7 (15.2) | 12 (31.6) | 21 (25.0) | 19 (90.5) |

| Rete testis involvement | |||||

| Present | 16 (34.8) | 14 (30.4) | 9 (23.7) | 30 (35.7) | 1 (4.8) |

| Absent | 30 (65.2) | 32 (69.6) | 29 (76.3) | 54 (64.3) | 20 (95.2) |

| Hilum involvement | |||||

| Present | 8 (17.4) | 3 (6.5) | 2 (5.3) | 10 (11.9) | 1 (4.8) |

| Absent | 38 (82.6) | 43 (93.5) | 36 (94.7) | 74 (88.1) | 20 (95.2) |

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte | |||||

| Present | 12 (26.1) | 9 (19.6) | 7 (18.4) | 50 (59.5) | 1 (4.8) |

| Absent | 34 (73.9) | 37 (80.4) | 31 (81.6) | 34 (40.5) | 20 (95.2) |

| Epididymis involvement | |||||

| Present | 4 (8.7) | 5 (10.9) | 3 (7.9) | 8 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) |

| Absent | 42 (91.3) | 41 (89.1) | 35 (92.1) | 76 (90.5) | 20 (95.2) |

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | |||||

| Present | 28 (60.9) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Absent | 18 (39.1) | 44 (95.7) | 38 (100.0) | 79 (94.0) | 21 (100.0) |

| Tunica albuginea invasion | |||||

| Present | 28 (60.9) | 22 (47.8) | 17 (44.7) | 47 (56.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| Absent | 18 (39.1) | 24 (52.2) | 21 (55.3) | 37 (44.0) | 20 (95.2) |

| Spermatic cord invasion | |||||

| Present | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Absent | 43 (93.5) | 43 (93.5) | 38 (100.0) | 81 (96.4) | 21 (100.0) |

| Spermatic cord margin invasion | |||||

| Present | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Absent | 45 (97.8) | 45 (97.8) | 38 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) |

| Tumor necrosis | |||||

| Present | 42 (91.3) | 38 (82.6) | 22 (57.9) | 51 (60.7) | 2 (9.5) |

| Absent | 4 (8.7) | 8 (17.4) | 16 (42.1) | 33 (39.3) | 19 (90.5) |

| Scar | |||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Absent | 46 (100.0) | 46 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) |

| Serum tumor markers | |||||

| Elevated | 29 (63.0) | 34 (73.9) | 28 (73.7) | 37 (44.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Within normal limits | 11 (23.9) | 6 (13.0) | 5 (13.2) | 39 (46.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not identified | 6 (13.0) | 6 (13.0) | 5 (13.2) | 8 (9.5) | 21 (100.0) |

| Distant metastasis | |||||

| Present | 2 (4.3) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Absent | 44 (95.7) | 44 (95.7) | 38 (100.0) | 81 (96.4) | 21 (100.0) |

| Tumor recurrence | |||||

| Yes | 4 (8.7) | 6 (13.0) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 42 (91.3) | 40 (87.0) | 34 (89.5) | 78 (92.9) | 21 (100.0) |

TGCTs testicular germ cell tumors

Expression of hTERT protein in the subtypes of TGCTs, benign, and adjacent normal tissue samples

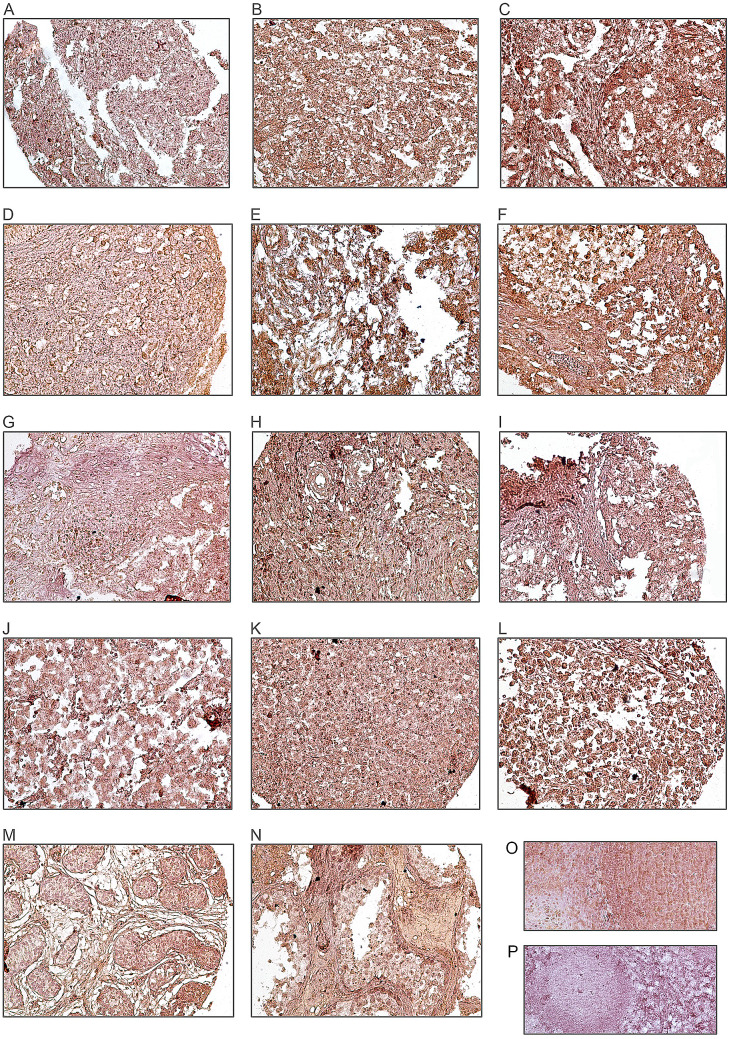

The expression level of hTERT protein was evaluated using IHC on TMA sections by three scoring methods, namely the intensity of staining, percentage of positive tumor cells, and H-score. hTERT marker was expressed at different intensities in the nucleus and cytoplasm in the samples; however, we focused only on the nuclear expression of hTERT because cytoplasmic hTERT expression was detected uniform. hTERT protein expressions were detected in all cases of TGCTs as well as benign tumors (Table 2). The mean expression level of hTERT protein was 280 in benign samples, 284 in embryonal carcinoma, 208 in yolk sac tumor, 218 in teratoma, and 262 in seminoma. There was less expression of hTERT in adjacent normal tissues compared to tumor samples. Moreover, human tonsil tissue used as a positive control showed strong staining in nucleus (Fig. 1). The figures of isotype controls are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Association of nuclear hTERT protein expression (intensity of staining, percentage of positive tumor cells, and H-score) between subtypes of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) and benign tumors (P value; Pearson’s test)

| Scoring system | Embryonal carcinoma N (%) | Yolk sac tumor N (%) | Teratoma N (%) | Seminoma N (%) | P value | Benign tumors N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of staining | 0.001 | |||||

| Negative (0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Weak (+1) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Moderate (+2) | 7 (8.6) | 26 (32.1) | 21 (25.9) | 27 (33.3) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Strong (+3) | 39 (32.8) | 12 (10.1) | 13 (10.9) | 55 (46.2) | 17 (81.0) | |

| Percentage of positive tumor cells | –* | |||||

| < 25% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 25–50% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–75% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 75% | 46 (21.5) | 46 (21.5) | 38 (17.8) | 84 (39.3) | 21 (100.0) | |

| H-score (3 groups) | 0.001 | |||||

| 0–100 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (53.3) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 101–200 | 7 (8.8) | 26 (32.5) | 20 (25.0) | 27 (33.8) | 4 (19.0) | |

| 201–300 | 39 (32.8) | 12 (10.1) | 13 (10.9) | 55 (46.2) | 17 (81.0) | |

| Total | 46 | 46 | 38 | 84 | 21 |

Values in bold are statistically significant

H-score histological score

*No statistical are computed because the parameter is constant

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of hTERT expression in TGCTs samples. hTERT expression in embryonal carcinomas: a low expression, b moderate expression, c high expression. In yolk sac tumors: d low expression, e moderate expression f, high expression. hTERT expression in teratomas: g low expression, h moderate expression, i high expression. hTERT expression in seminomas: j low expression, k moderate expression, l high expression. IHC staining of adjacent normal tissue (m), benign tumor tissue (n), and also tonsil tissues as (o) positive and (p) negative controls

Comparison of hTERT protein expression based on histological subtypes of TGCTs

Pearson’s test was performed to examine the association between expression of hTERT protein and histological subtypes of TGCTs. Results showed that there is a statistically significance difference between the expression of hTERT and various subtypes of TGCTs [in terms of intensity, and H-score (all, P < 0.001)] (Table 2)). The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests were applied to compare differences between the mean expression level of hTERT protein among the histological subtypes of TGCTs. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference between the various levels of hTERT protein expression in different TGCTs subtypes (P < 0.001). Mann–Whitney U test also demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the mean level of hTERT protein expression between the subtypes of TGCTs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean level of hTERT protein expression between histological subtypes of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs)

| Histological subtypes of TGCTs | P value |

|---|---|

| Embryonal carcinoma and yolk sac tumor | < 0.001 |

| Embryonal carcinoma and teratoma | < 0.001 |

| Embryonal carcinoma and seminoma | 0.016 |

| Seminoma and yolk sac tumor | < 0.001 |

| Seminoma and teratoma | < 0.001 |

| Teratoma and yolk sac tumor | 0.412 |

Values in bold are statistically significant

Associations between hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristics in subtypes of TGCTs

Embryonal carcinoma

In embryonal carcinoma, Pearson’s test showed a significant association between expression of hTERT protein and pT stage (P = 0.023) as well as tunica vaginalis invasion (P = 0.043). We did not find any association between hTERT protein expression and the other clinicopathological characteristics (Table 4). Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a statistically significant difference (P = 0.025) between the mean expression level of hTERT protein and various pT stages (I–III). The mean expression level of hTERT was 296 in stage I and 266 in stage II as well as stage III. Moreover, Mann–Whitney U test showed a significant difference in the mean level of hTERT protein expression between stages I and III (P = 0.050). Further, bivariate analysis was performed to show the correlation between expression of hTERT protein and clinicopathological characteristics. The results of bivariate analysis revealed that a significant inverse correlation between hTERT protein expression and advanced in pT stages (P = 0.006) as well as invasion to tunica vaginalis (P = 0.043). Low level expression of hTERT protein correlated with increased pT stages and invasion to tunica vaginalis.

Table 4.

The association between nuclear hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristic of embryonal carcinoma samples (intensity of staining and H-score)

| Characteristics of tumors | Total cases N (%) |

Intensity of staining N (%) | P value | H-score | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonal carcinoma | 46 | 0 (negative) | 1+ (weak) | 2+ (moderate) | 3+ (strong) | H-score 0–100 |

H-score 101–200 |

H-score 201–300 |

||

| Mean age, years (range) | 29 (16–59) | 0.428 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

3(42.9) 4(57.1) |

23(59.0) 16(41.0) |

0.428 | ||||

| ≤Mean | 26 (56.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (42.9) | 23 (59.0) | |||||

| >Mean | 20 (43.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (57.1) | 16 (41.0) | |||||

| Mean tumor size (cm) (range) | 4 (1.5–11.5) | 0.388 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

5 (71.4) 2 (28.6) |

21 (53.8) 18 (46.2) |

0.388 | ||||

| ≤Mean | 26 (56.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (71.4) | 21 (53.8) | |||||

| >Mean | 20 (43.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 18 (46.2) | |||||

| Primary tumor (PT) stage | ||||||||||

| pT1 | 28 (60.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 27 (69.2) | 0.023 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) 5 (71.4) 1 (14.3) 0 (0.0) |

27 (69.2) 10 (25.6) 2 (5.1) 0 (0.0) |

0.023 |

| pT2 | 15 (32.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (71.4) | 10 (25.6) | |||||

| pT3 | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.1) | |||||

| Not classified | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Venous invasion (VI) | ||||||||||

| Present | 18 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (71.4) | 13 (33.3) | 0.057 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

5 (71.4) 2 (28.6) |

13 (33.3) 26 (66.7) |

0.057 |

| Absent | 28 (60.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 26 (66.7) | |||||

| Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) | ||||||||||

| Present | 40 (87.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 33 (84.6) | 0.266 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

7 (100.0) 0 (0.0) |

33 (84.6) 6 (15.4) |

0.266 |

| Not identified | 6 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.4) | |||||

| Rete testis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 16 (34.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 15 (38.5) | 0.216 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) 6 (85.7) |

15 (38.5) 24 (61.5) |

0.216 |

| Absent | 30 (65.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 24 (61.5) | |||||

| Hilum involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 8 (17.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (17.9) | 0.814 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) 6 (85.7) |

7 (17.9) 32 (82.1) |

0.814 |

| Absent | 38 (82.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 32 (82.1) | |||||

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte | ||||||||||

| Present | 12 (26.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (42.9) | 9 (23.1) | 0.272 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

3 (42.9) 4 (57.1) |

9 (23.1) 30 (76.9) |

0.272 |

| Absent | 34 (73.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (57.1) | 30 (76.9) | |||||

| Epididymis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.3) | 0.375 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) 7 (100.0) |

4 (10.3) 35 (89.7) |

0.375 |

| Absent | 42 (91.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 35 (89.7) | |||||

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (5.1) | 0.043 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

2 (28.6) 5 (71.4) |

2 (5.1) 37 (94.9) |

0.043 |

| Absent | 42 (91.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (71.4) | 37 (94.9) | |||||

| Tunica albuginea invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 28 (60.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 22 (56.4) | 0.144 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

6 (85.7) 1 (14.3) |

22 (56.4) 17 (43.6) |

0.144 |

| Absent | 18 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 17 (43.6) | |||||

| Spermatic cord invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.1) | 0.366 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) 6 (85.7) |

2 (5.1) 37 (94.9) |

0.366 |

| Absent | 43 (93.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 37 (94.9) | |||||

| Spermatic cord margin invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0.668 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) 7 (100.0) |

1 (2.6) 38 (97.4) |

0.668 |

| Absent | 45 (97.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 38 (97.4) | |||||

| Tumor necrosis | ||||||||||

| Present | 42 (91.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 35 (89.7) | 0.375 | 0 (0.0) |

7 (100.0) 0 (0.0) |

35 (89.7) 4 (10.3) |

0.375 |

| Absent | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Scar | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) 7 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 39 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 46 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) | |||||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||||

| Present | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0.161 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) 6 (85.7) |

1 (2.6) 38 (97.4) |

0.161 |

| Absent | 44 (95.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 38 (97.4) | |||||

| Tumor recurrence | ||||||||||

| Yes | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (7.7) | 0.569 |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) 6 (85.7) |

3 (7.7) 36 (92.3) |

0.569 |

| No | 42 (91.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 36 (92.3) | |||||

Values in bold are statistically significant

P value; Pearson’s test

H-score histological score

*No statistical are computed because the parameter is constant

Yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and seminoma

In yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and seminoma, there was no significant association between hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristics of patients (Tables 5, 6 and 7).

Table 5.

The association between nuclear hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristic of yolk sac tumor samples (Intensity of staining and H-score)

| Characteristics of tumors | Total cases N (%) |

Intensity of staining N(%) | P value | H-score | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolk sac tumor | 46 | 0 (negative) | 1+ (weak) | 2+ (moderate) | 3+ (strong) | H-score 0–100 |

H-score 101–200 |

H-score 201–300 |

||

| Median age, years (range) | 28 (1–59) | |||||||||

| ≤Median | 25 (54.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (37.5) | 15 (57.7) | 7 (58.3) | 0.574 |

3 (37.5) 5 (62.5) |

15 (57.7) 11 (42.3) |

7 (58.3) 5 (41.7) |

0.574 |

| >Median | 21 (45.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (62.5) | 11 (42.3) | 5 (41.7) | |||||

| Mean tumor size (cm) (range) | 5 (1–15) | |||||||||

| ≤Mean | 28 (60.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (62.5) | 16 (61.5) | 7 (58.3) | 0.977 |

5 (62.5) 3 (37.5) |

16 (61.5) 10 (38.5) |

7 (58.3) 5 (41.7) |

0.977 |

| >Mean | 18 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (37.5) | 10 (38.5) | 5 (41.7) | |||||

| Primary tumor (PT) stage | ||||||||||

| pT1 | 31 (67.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (50.0) | 17 (65.4) | 10 (83.3) | 0.572 |

4 (50.0) 3 (37.5) 1 (12.5) 0 (0.0) |

17 (65.4) 7 (26.9) 2 (7.7) 0 (0.0) |

10 (83.3) 2 (16.7) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

0.572 |

| pT2 | 12 (26.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (16.7) | |||||

| pT3 | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Not classified | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Venous invasion (VI) | ||||||||||

| Present | 14 (30.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (37.5) | 9 (34.6) | 2 (16.7) | 0.478 |

3 (37.5) 5 (62.5) |

9 (34.6) 17 (65.4) |

2 (16.7) 10 (83.3) |

0.478 |

| Absent | 32(69.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (62.5) | 17 (65.4) | 10 (83.3) | |||||

| Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) | ||||||||||

| Present | 39 (84.8) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) | 21 (80.8) | 11 (91.7) | 0.667 |

7 (87.5) 1 (12.5) |

21 (80.8) 5 (19.2) |

11 (91.7) 1 (8.3) |

0.667 |

| Not identified | 7 (15.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (19.2) | 1 (8.3) | |||||

| Rete testis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 14 (30.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 9 (34.6) | 3 (25.0) | 0.781 |

2 (25.0) 6 (75.0) |

9 (34.6) 17 (65.4) |

3 (25.0) 9 (75.0) |

0.781 |

| Absent | 32 (69.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (75.0) | 17 (65.4) | 9 (75.0) | |||||

| Hilum involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.291 |

0 (0.0) 8 (100.0) |

3 (11.5) 23 (88.5) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.291 |

| Absent | 43 (93.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | 23 (88.5) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte | ||||||||||

| Present | 9 (19.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.93 |

3 (37.5) 5 (62.5) |

6 (23.1) 20 (76.9) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.93 |

| Absent | 37 (80.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (62.5) | 20 (76.9) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Epididymis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 5 (10.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.362 |

1 (12.5) 7 (87.5) |

4 (15.4) 22 (84.6) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.362 |

| Absent | 41 (89.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) | 22 (84.6) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.399 |

1 (12.5) 7 (87.5) |

1 (3.8) 25 (96.2) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.399 |

| Absent | 44 (95.7) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) | 25 (96.2) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Tunica albuginea invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 22 (47.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) | 0.884 |

4 (50.0) 4 (50.0) |

13 (50.0) 13 (50.0) |

5 (41.7) 7 (58.3) |

0.884 |

| Absent | 24 (52.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | 7 (58.3) | |||||

| Spermatic cord invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.505 |

1 (12.5) 7 (87.5) |

2 (7.7) 24 (92.3) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.505 |

| Absent | 43 (93.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) | 24 (92.3) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Spermatic cord margin invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.675 |

0 (0.0) 8 (100.0) |

1 (3.8) 25 (96.2) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.675 |

| Absent | 45 (97.8) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | 25 (96.2) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor necrosis | ||||||||||

| Present | 38 (82.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (75.0) | 23 (88.5) | 9 (75.0) | 0.490 |

6 (75.0) 2 (25.0) |

23 (88.5) 3 (11.5) |

9 (75.0) 3 (25.0) |

0.490 |

| Absent | 8 (17.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (25.0) | |||||

| Scar | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 26 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.) |

0 (0.0) 8 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 46 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | |||||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||||

| Present | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.447 |

0 (0.0) 8 (100.0) |

2 (7.7) 24 (92.3) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.447 |

| Absent | 44 (95.7) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | 24 (92.3) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor recurrence | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (19.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.262 |

1 (12.5) 7 (87.5) |

5 (19.2) 21 (80.8) |

0 (0.0) 12 (100.0) |

0.262 |

| No | 40 (87.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) | 21 (80.8) | 12 (100.0) | |||||

Values in bold are statistically significant

P value; Pearson’s test

H-score histological score

*No statistical are computed because the parameter is constant

Table 6.

The association between nuclear hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristic of teratoma samples (intensity of staining and H-score)

| Characteristics of tumors | Total cases N (%) |

Intensity of staining N(%) | P value | H-score | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teratoma | 38 | 0 (negative) | 1+ (weak) | 2+ (moderate) | 3+ (strong) | H-score 0–100 |

H-score 101–200 |

H-score 201–300 |

||

| Mean age, years (range) | 25 (1–45) | |||||||||

| ≤Mean | 19 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 10 (47.6) | 6 (46.2) | 0.570 |

4 (80.0) 1 (20.0) |

9 (45.0) 11 (55.0) |

6 (46.2) 7 (53.8) |

0.354 |

| >Mean | 19 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 11 (52.4) | 7 (53.8) | |||||

| Mean tumor size (cm) (range) | 5 (1–15) | |||||||||

| ≤Mean | 24 (63.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 12 (57.1) | 9 (69.2) | 0.679 |

4 (80.0) 1 (20.0) |

11 (55.0) 9 (45.0) |

9 (69.2) 4 (30.8) |

0.500 |

| >Mean | 14 (36.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 9 (42.9) | 4 (30.8) | |||||

| Primary tumor (PT) stage | ||||||||||

| pT1 | 27 (71.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 15 (71.4) | 10 (76.9) | 0.525 |

3 (60.0) 1 (20.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (20.0) |

14 (70.0) 3 (15.0) 0 (0.0) 3 (15.0) |

10 (76.9) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 3 (23.1) |

0.297 |

| pT2 | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| pT3 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Not classified | 7 (18.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (23.1) | |||||

| Venous invasion (VI) | ||||||||||

| Present | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.255 |

1 (20.0) 4 (80.0) |

3 (15.0) 17 (85.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

0.297 |

| Absent | 34 (89.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 18 (85.7) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) | ||||||||||

| Present | 26 (68.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 14 (66.7) | 9 (69.2) | 0.945 |

3 (60.0) 2 (40.0) |

14 (70.0) 6 (30.0) |

9 (69.2) 4 (30.8) |

0.909 |

| Not identified | 12 (31.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 7 (33.3) | 4 (30.8) | |||||

| Rete testis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 9 (23.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) | 0.244 |

1 (20.0) 4 (80.0) |

6 (30.0) 14 (70.0) |

2 (15.4) 11 (84.6) |

0.614 |

| Absent | 29 (76.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (66.7) | 11 (84.6) | |||||

| Hilum involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.425 |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

2 (20.0) 18 (90.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

0.387 |

| Absent | 36 (94.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 19 (90.5) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte | ||||||||||

| Present | 7 (18.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (30.8) | 0.292 |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

3 (15.0) 17 (85.0) |

4 (30.8) 9 (69.2) |

0.272 |

| Absent | 31 (81.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 18 (85.7) | 9 (69.2) | |||||

| Epididymis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (7.7) | 0.388 |

1 (20.0) 4 (80.0) |

1 (5.0) 19 (95.0) |

1 (7.7) 12 (92.3) |

0.538 |

| Absent | 35 (92.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 20 (95.2) | 12 (92.3) | |||||

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

0 (0.0) 20 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Tunica albuginea invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 17 (44.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 10 (47.6) | 6 (46.2) | 0.701 |

1 (20.0) 4 (80.0) |

10 (50.0) 10 (50.0) |

6 (46.2) 7 (53.8) |

0.479 |

| Absent | 21 (55.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 11 (52.4) | 7 (53.8) | |||||

| Spermatic cord invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

0 (0.0) 20 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Spermatic cord margin invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

0 (0.0) 20 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor necrosis | ||||||||||

| Present | 22 (57.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 11 (52.4) | 8 (61.5) | 0.666 |

3 (60.0) 2 (40.0) |

11 (55.0) 9 (45.0) |

8 (61.5) 5 (38.5) |

0.928 |

| Absent | 16 (42.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 10 (47.6) | 5 (38.5) | |||||

| Scar | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

0 (0.0) 20 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

0 (0.0) 20 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 13 (100.0) |

–* |

| Absent | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor recurrence | ||||||||||

| Yes | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (7.7) | 0.639 |

0 (0.0) 5 (100) |

3 (15.0) 17 (85.0) |

1 (7.7) 12 (92.3) |

0.570 |

| No | 34 (89.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 18 (85.7) | 12 (92.3) | |||||

Values in bold are statistically significant

P value; Pearson’s test

H-score histological score

*No statistical are computed because the parameter is constant

Table 7.

The association between nuclear hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristic of seminoma samples (intensity of staining and H-score)

| Characteristics of tumors | Total cases N (%) |

Intensity of staining N(%) | P value | H-score | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seminoma | 84 | 0 (negative) | 1+ (weak) | 2+ (moderate) | 3+ (strong) | H-score 0–100 |

H-score 101–200 |

H-score 201–300 |

||

| Median age, years (range) | 33 (19–79) | |||||||||

| ≤ Median | 47 (56.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 14 (51.9) | 32 (58.2) | 0.850 |

1 (50.0) 1 (50.0) |

14 (51.9) 13 (48.1) |

32 (58.2) 23 (41.8) |

0.850 |

| > Median | 37 (44.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 13 (48.1) | 23 (41.8) | |||||

| Mean tumor size (cm) (range) | 5 (1-20) | |||||||||

| ≤ Mean | 53 (63.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 16 (59.3) | 36 (65.5) | 0.799 |

1 (50.0) 1 (50.0) |

16 (59.3) 11 (40.7) |

36 (65.5) 19 (34.5) |

0.799 |

| > Mean | 31 (36.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 11 (40.7) | 19 (34.5) | |||||

| Primary tumor (PT) stage | ||||||||||

| pT1 | 55 (65.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 18 (66.7) | 35 (63.6) | 0.889 |

2 (100.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

18 (66.7) 7 (25.9) 2 (7.4) 0 (0.0) |

35 (63.6) 17 (30.9) 2 (3.6) 1 (1.8) |

0.889 |

| pT2 | 24 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (25.9) | 17 (30.9) | |||||

| pT3 | 4 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.6) | |||||

| Not classified | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | |||||

| Venous invasion (VI) | ||||||||||

| Present | 23 (27.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (25.9) | 16 (29.1) | 0.649 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

7 (25.9) 20 (74.1) |

16 (29.1) 39 (70.9) |

0.649 |

| Absent | 61 (72.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 20 (74.1) | 39 (70.9) | |||||

| Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) | ||||||||||

| Present | 63 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 21 (77.8) | 41 (74.5) | 0.676 |

1 (50.0) 1 (50.0) |

21 (77.8) 6 (22.2) |

41 (74.5) 14 (25.5) |

0.676 |

| Not identified | 21 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 6 (22.2) | 14 (25.5) | |||||

| Rete testis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 30 (35.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (37.0) | 20 (36.4) | 0.565 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

10 (37.0) 17 (63.0) |

20 (36.4) 35 (63.6) |

0.565 |

| Absent | 54 (64.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 17 (63.0) | 35 (63.6) | |||||

| Hilum involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 10 (11.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 9 (16.4) | 0.218 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

1 (3.7) 26 (96.3) |

9 (16.4) 46 (83.6) |

0.218 |

| Absent | 74 (88.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) | 46 (83.6) | |||||

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte | ||||||||||

| Present | 50 (59.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 14 (51.9) | 35 (36.4) | 0.751 |

1 (50.0) 1 (50.0) |

14 (51.9) 13 (48.1) |

35 (36.4) 20 (36.4) |

0.751 |

| Absent | 34 (40.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 13 (48.1) | 20 (36.4) | |||||

| Epididymis involvement | ||||||||||

| Present | 8 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.1) | 5 (9.1) | 0.860 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

3 (11.1) 24 (88.9) |

5 (9.1) 50 (90.9) |

0.860 |

| Absent | 76 (90.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 24 (88.9) | 50 (90.9) | |||||

| Tunica vaginalis invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 5 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (7.3) | 0.763 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

1 (3.7) 26 (96.3) |

4 (7.3) 51 (92.7) |

0.763 |

| Absent | 79 (94.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) | 51 (92.7) | |||||

| Tunica albuginea invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 47 (56.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 13 (48.1) | 33 (60.0) | 0.588 |

1 (50.0) 1 (50.0) |

13 (48.1) 14 (51.9) |

33 (60.0) 22 (40.0) |

0.588 |

| Absent | 37 (44.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 14 (51.9) | 22 (40.0) | |||||

| Spermatic cord invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.963 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

1 (3.7) 26 (96.3) |

2 (3.6) 53 (96.4) |

0.963 |

| Absent | 81 (96.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) | 53 (96.4) | |||||

| Spermatic cord margin invasion | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 27 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 55 (100.) |

–* |

| Absent | 84 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 27 (100.0) | 55 (100.0) | |||||

| Tumor necrosis | ||||||||||

| Present | 51 (60.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (66.7) | 33 (60.0) | 0.173 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

18 (66.7) 9 (33.3) |

33 (60.0) 22 (40.0) |

0.173 |

| Absent | 33 (39.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 9 (33.3) | 22 (40.0) | |||||

| Scar | ||||||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | –* |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 27 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 55 (100.) |

–* |

| Absent | 84 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 27 (100.0) | 55 (100.0) | |||||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||||

| Present | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.963 |

0 (0.0) 2 (100.0) |

1 (3.7) 26 (96.3) |

2 (3.6) 53 (96.4) |

0.963 |

| Absent | 81 (96.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) | 53 (96.4) | |||||

| Tumor recurrence | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.9) | 0.182 | 0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) 27 (100.0) |

6 (10.9) 49 (89.1) |

0.182 |

| No | 78 (92.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 27 (100.0) | 49 (89.1) | 2 (100.0) | ||||

P value; Pearson’s test

H-score histological score

*No statistical are computed because the parameter is constant

Values in bold are statistically significant

Prognostic value of hTERT protein expression for clinical outcomes in TGCTs

In the present study, in non-seminomatous GCTs, 116 (89.2%) patients had no history of metastasis and recurrence but 14 (10.8%) patients were positive for these parameters. Metastasis and recurrence occurred in 4 (3.1%) and 14 (10.8%) patients, respectively. During the follow-up, cancer-related death occurred in 7 patients (5.4%). The mean duration of the follow-up was 61 months (SD = 24.9), median was 53.0 months (39, 81), and range was 16–107 months. Table 8 shows the main characteristics of patients enrolled for survival analysis according to the subtypes of TGCTs.

Table 8.

The main characteristics of patients enrolled for survival analysis according to histological subtypes of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs)

| Features | Histological subtypes of TGCTs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonal carcinoma N (%) | Yolk sac tumor N (%) | Teratoma N (%) | Seminoma N (%) | |

| Number of patients (N) | 46 | 46 | 38 | 84 |

| Follow-up duration (months) | 105 | 107 | 107 | 105 |

| Mean duration of follow-up time (months) (SD) | 58 (25.1) | 64 (24.7) | 62 (25.1) | 60 (23.7) |

| Median duration of follow-up time (months) (Q1, Q3) | 49 (40, 80) | 63 (44, 82) | 57 (39, 81) | 57 (41, 79) |

| Cancer-related death (N %) | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.5) | 1 (2.6) | 1(1.2) |

| Distant metastasis during follow-up (N %) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) |

| Tumor recurrence during follow-up (N %) | 4 (8.7) | 6 (13.0) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (7.1) |

| Alive patients without metastasis and recurrence (N %) | 42 (91.3) | 40 (87.0) | 34 (89.5) | 76 (90.5) |

Survival outcomes based on the expression of hTERT protein in the subtypes of TGCTs

Embryonal carcinoma

The results of Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrated significant differences between DSS and the patients with high and moderate expression of hTERT (P = 0.011) (Fig. 2a). In this study the expression level of hTERT based on the classification of H-score in low expression (H-score 0–100) was 0. The mean DSS time for patients with high and moderate expression of hTERT was 103 (SD = 1.9) and 82 (SD = 13.2) months, respectively. In addition, the 5-year survival rates for DSS in patients whose specimens expressed high and moderate expression of hTERT protein was 97 and 66%, respectively (P = 0.021). Moreover, the results of Kaplan–Meier displayed significant differences between PFS and the patients with high and moderate hTERT protein expression (P = 0.011) (Fig. 2b). Further, the mean PFS time for patients with high and moderate expression of hTERT protein was 102 (SD = 2.6) and 78 (SD = 15.8) months, respectively. The 5-year survival rates for PFS in patients whose specimens expressed high expression of hTERT protein was 97 and moderate expression was 70% (P = 0.018).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to the protein expression levels of hTERT in embryonal carcinomas. a In embryonal carcinoma patients, moderate level of hTERT protein expression was associated with shorter DSS compared to the tumors with higher expression of this protein (P = 0.011). b Moderate expression of hTERT had shorter PFS than those with high expression (P = 0.011). The expression level of hTERT was 0 based on the classification of H-score in low expression (H-score 0–100)

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to investigate whether the expression of hTERT protein was an independent prognostic factor of DSS and PFS, and to assess the clinical significance of various parameters that might influence survival outcomes in patients with embryonal carcinoma. Our finding showed that the expression of hTERT, pT stage, and spermatic cord invasion were significant risk factors affecting the DSS or PFS of patients with embryonal carcinoma in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis (Table 9). Other clinicopathologic variables were not significant factors for the DSS or PFS in univariate and multivariate analyses in patients with embryonal carcinoma.

Table 9.

Univariate and multivariate cox regression analyses of potential prognostic factors for disease-specific survival and progression-free survival in patients with embryonal carcinoma

| Disease-specific survival (DSS) | Progression-free survival (PFS) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Expression of hTERT protein | ||||||||

| Moderate vs high | 1.087 (1.008–1.958) | 0.046 | 0.172 (0.012–2.449) | 0.194 | 1.086 (1.008–1.953) | 0.046 | 0.322 (0.028–3.656) | 0.361 |

| Primary tumor (PT) stage | 19.701 (2.145–28.958) | 0.008 | 0.003 (0.001–9.081) | 0.952 | 15.665 (1.901–129.102) | 0.011 | 205 (0.001–3.337) | 0.938 |

| Spermatic cord invasion | 43.052 (3.0750–49.203) | 0.003 | 7. 717 (1.00–2.356) | 0.927 | 35.273 (3.178–391.525) | 0.004 | 0.001 (0.001–8.299) | 0.952 |

The variables with P value less than 0.05 were included in multivariable analyses

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Values in bold are statistically significant

Yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and seminoma

The Kaplan–Meier curves showed that there were no significant differences between DSS or PFS and the patients with high, moderate, and low expression of hTERT in yolk sac tumors (Fig. 3a, b) and seminomas (Fig. 4a, b). In addition, results of univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated that clinicopathological variables were not significant factors affecting DSS or PFS in these cases. There was only one cancer-related death in the subtype of teratomas, so it was impossible to calculate the P value of Kaplan–Meier curves for DSS and PFS.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free survival (PFS) based on hTERT protein expression level in yolk sac tumors. In yolk sac tumors, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that low levels of hTERT expression are not significantly related to a DSS (P = 0.295) and b PFS (P = 0.277), respectively

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free survival (PFS) based on hTERT protein expression level in seminomas. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that there are no statistically differences between a DSS or b PFS and the patients with high, moderate, and low expression of hTERT in seminomas (P = 0.779, P = 0.534), respectively

Associations between hTERT protein expression and clinicopathological characteristics in non-seminomatous GCT

In non-seminomatous GCT samples (130 cases), we did not find any significant association between the expression of hTERT protein and clinicopathological characteristics (Supplementary Table 1). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that lower expression of hTERT protein leads to reduce the patients’ survival outcomes and progression of disease, but without any statistically significant association in log-rank test (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). In addition, the results of univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated that the listed clinicopathologic variables were not significant factors for the DSS or PFS of patients with non-seminomatous GCT.

Discussion

TGCTs are the most frequent solid malignant tumors affecting the majority of younger males and the most frequent cause of death from solid tumors in this group (Albers et al. 2018; Stephenson et al. 2019). About 90% of TGCTs are successfully treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy (Leão et al. 2019). Despite that, it seems reasonable to introduce molecular markers that would help define the most appropriate treatment and follow-up of these patients due to the limitation of currently available serum biomarkers, side effects and also long-term toxicities of recent treatments, including the possibility of developing secondary cancers and cardiovascular disease (Fung et al. 2015; Oldenburg 2015; Richie 2006).

Telomerase was thought to be an attractive target for the development of a novel biomarker and anti-cancer therapeutics target because it is expressed almost universally in human cancers and low or non-expression in majority of normal somatic cells (Cifuentes-Rojas and Shippen 2012; Shay and Wright 2010). Previous studies have investigated the expression levels of telomerase activity using TRAP assay technique and expression of hTERT mRNA by RT-PCR in TGCTs (Nowak et al. 2000; Schrader et al. 2002; 叶哲伟 et al. 2004), whereas we could not find any study addressing the expression of hTERT protein in these type of tumors.

This study is the first report to investigate the levels of hTERT protein expression in a large series of TGCTs samples, including 46 embryonal carcinoma, 46 yolk sac tumor, 38 teratoma, and 84 seminoma treated with radical orchiectomy through IHC on TMA slides. To the best of our knowledge, there was only one study which has adopted the IHC method, and worked in canine testicular tumors to determine the IHC expression of canine hTERT as compared two different antibodies for hTERT and to correlate them with well-established markers specific to dividing cells such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and ki67. Their finding indicated that hTERT and PCNA are useful proliferation markers, but not helpful to evaluate prognosis (Papaioannou et al. 2009).

Investigation of the histological subtypes is critical for therapeutic decisions and contributes to reducing mortality, considering that these various histological subtypes of TGCTs may be associated with different biologic behavior and prognostic measures. Currently, no information concerning TGCTs histological subtypes was available for this matter. Thus, in the current study, the expression patterns of hTERT protein in different histological subtypes of TGCTs were assed. TGCTs subtypes display differential expression of hTERT protein with a range of intensities from weak to strong. Also, there were highly significant associations between the level of hTERT protein expression and TGCTs histological subtypes (P < 0.001). Moreover, a significant difference was observed in the mean level of hTERT protein expression between embryonal carcinoma and yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and seminoma, respectively (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.016), and between seminoma and yolk sac tumor as well as seminoma and teratoma (all, P < 0.001). These findings demonstrate that hTERT has different expression patterns among various subtypes of TGCTs so it can influence the value of prognosis and treatment of patients. In addition, in our study, embryonal carcinoma and benign samples showed the highest expression of hTERT protein compared to other histological subtypes as well as adjacent normal tissues, whereas teratoma exhibited the lowest hTERT protein expression. Our finding is in agreement with a study performed by Mark Schrader et al. who showed that telomerase activity is higher in embryonal carcinoma which is the most undifferentiated subtypes of NSGCT compared to differentiated teratomas In other words, there was an inverse relationship between the level of telomerase activity and hTERT mRNA expression and the differentiation state of TGCTs (Schrader et al. 2002).

Embryonal carcinoma is the most common NSGCT and is an aggressive tumor which presents 77% of mixed of NSGCT. Pure forms of NSGCT are relatively uncommon. In addition, embryonal carcinoma has a capacity to differentiate into various lineages, including choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumor and teratoma (Bahrami et al. 2007). In this study, we showed that there is an adverse correlation between the expression of hTERT protein and more advanced pTstage as well as the invasion to tunica vaginalis in embryonal carcinoma cases. In addition, pTstage and spermatic cord invasion were prognostic variables in univariate analysis. The prognostic impact of such parameters in these patients has already been investigated, so that these variables are associated with more aggressive tumor behavior (Magers and Idrees 2018) (Sanfrancesco et al. 2018) (Yilmaz et al. 2013). According to the previous studies in the majority of cancers, higher expression of telomerase activity is correlated with malignancy such as lung, oral squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer and ccRCC (Chen et al. 2007; Lu et al. 2004; Marchetti et al. 2002; Zachos et al. 2009; Saeednejad Zanjani et al. 2019b) but this is not the case in TGCTs, since the origin of TGCTs, male germ cells, also possess high intrinsic telomerase activity (Wright et al. 1996). Thus, by transforming the normal germ cells into the tumor cells and progressing to the malignancy, the expression of hTERT will decrease. Importantly, we observed that the mean expression level of hTERT protein was less in more advanced tumor stages (stages II and III) compared with lower stage (stages I), which reveals that low level expression of hTERT protein is associated with the aggressiveness of embryonal carcinoma.

In this study, for the first time, we found that tumors with low level expression of hTERT protein tend to have a worse prognosis for DSS and PFS compared to those with high expression. In addition, embryonal carcinoma patients who expressed a lower level of hTERT had a shorter 5-year survival rates for DSS and PFS compared with those with high expression. Thus, our findings indicated that there are inverse relationships between the level expression of hTERT and an increased in pTstage, invasion of tunica vaginalis, exacerbated prognosis, and more advanced diseases in embryonal carcinoma samples. Regarding embryonal carcinoma, our findings are in line with the characteristics of some cancer stem cells (CSCs) in previous studies (Campbell et al. 2006; Saeednejad Zanjani et al. 2019a; Shervington et al. 2009). CSCs are a small subpopulation of the cells within the tumor which possess features associated with normal stem cells, which are able to differentiate, accelerate tumor development, disease progression, treatment resistance and metastasis, and foster the recurrence in several human cancers (Nguyen et al. 2012). In a recent study by our group, (Saeednejad Zanjani et al. 2019a) spheroid derived cells (SDCs) from renal adenocarcinoma ACHN cell line enriched using sphere culture system, showed low level expression of hTERT mRNA and telomerase activity compared to parental ACHN cells, while this population exhibited properties of CSCs including higher clonogenicity, extended superior-colony and sphere-forming ability, stronger tumorigenicity, and invasiveness. In addition, SDCs revealed a higher expression of markers for CSCs, stemness, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), apoptosis, and ABC transporter genes compared to their parental cells. Parallel to our recent study, embryonal carcinoma showed properties of CSCs, including invasiveness, worsened prognosis, and progression of disease with low level expression of hTERT. Moreover, hTERT has been demonstrated to be downregulated in the CD34 + haematopoietic stem cells compared to the parental cells of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and brain CSCs, respectively (Campbell et al. 2006; Shervington et al. 2009). It has been found that hTERT can modulate classical cancer pathways including NF-jB, TGF-b1/Smad, and Wnt/b-catenin signaling that all contribute to the metastatic of cancers and stem cell phenotype of cancer cells (Hannen and Bartsch 2018). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying our findings remain unclear and require more elaborate investigations.

As far as we know, this is the first study showing expression patterns and prognostic significant of the hTERT protein expression for DSS and PFD in TGCTs, without an independent prognostic significance in embryonal carcinoma though. Since the number of cancer-related deaths or events was low, more prolonged follow-up periods seem to be important because by extending the follow-up time the prognostic value of hTERT expression may also rise.

In this study, we found no significant association between the expression of hTERT protein and important clinicopathological parameters and patient outcomes in other subtypes of TGCTs. Thus, we could not conclude that hTERT is a useful prognostic marker across all histological subtypes of TGCTs. In addition, we demonstrated the importance of analyzing hTERT protein expression between individual histological subtypes of TGCTs as we observed significant prognostic results upon separate investigation of the histological subtypes; there was no significant prognostic results when the subtypes were classified into two main groups: seminomas and non-seminomatous GCT. Other markers may serve better for yolk sac tumor, teratoma, and seminoma.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings revealed a statistically significant difference between hTERT protein expression among the different histological subtypes of TGCTs. A better understanding of the histological subtypes will facilitate the development of better treatment options. Moreover, while embryonal carcinomas were found to have the highest mean expression level of hTERT protein, downregulation of hTERT protein expression was seen associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and worse prognosis affecting DSS and PFS. Therefore, hTERT protein expression may be a novel prognostic marker of worse outcomes and progression of the disease in embryonal carcinoma patients. Larger trials and more follow-up periods are needed to improve our knowledge about hTERT in order to clarify the prognostic impact of hTERT protein expression in TGCTs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1: Isotype controls in immunohistochemistry staining for confirming nonspecific binding of primary antibody. In embryonal carcinomas (A), yolk sac tumors (B), teratomas (C), seminomas (D), adjacent normal tissue (E), and in benign tumor tissue (F)

Supplementary Fig. 2: Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free survival (PFS) based on hTERT protein expression level in non-seminomatous GCT. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that low levels of hTERT expression are not significantly related to (A) DSS and (B) PFS (P = 0.161, P = 0.148), respectively in non-seminomatous GCT samples

Author contributions

ZM designed and supervised the work; MS gathered the paraffin-embedded tissues, collected the patient data, examined hematoxylin and eosin slides, and marked the most representative areas in different parts of the tumor for preparing the TMA blocks; LS performed the immunohistochemistry examinations, prepared the information of patient survival outcomes, analyzed and interpreted the data as well as wrote the manuscript; MAa, and MAb scored TMA slides after immunohistochemical staining; MR was a consultant on this project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant from Iran University of Medical Sciences (number: 1397-2-28-12348).

Data availability

The analyzed data during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences in Iran (Ref no: IR.IUMS.REC1397.443). All the procedures were performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants, parents or legally authorized representatives of participants under legal age years old at the time of sample collection with routine consent forms.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Marzieh Shahin and Leili Saeednejad Zanjani contributed equally to this work and are joint first authors.

References

- Albers P et al (2018) Testicular cancer EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Copenhagen. ISBN 978-94-92671-01-1

- Bahrami A, Ro JY, Ayala AG (2007) An overview of testicular germ cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 131:1267–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH (2005) Telomeres and telomerase: their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS Lett 579:859–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L et al (2006) hTERT, the catalytic component of telomerase, is downregulated in the haematopoietic stem cells of patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 20:671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H-H et al (2007) Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) protein is significantly associated with the progression, recurrence and prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan. Oral Oncol 43:122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Rojas C, Shippen DE (2012) Telomerase regulation. Mutat Res Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen 730:20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y, Shay JW (2008) Actions of human telomerase beyond telomeres. Cell Res 18:725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahse R, Fiedler W, Ernst G (1997) Telomeres and telomerase: biological and clinical importance. Clin Chem 43:708–714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmanfarma KK, Mahdavifar N, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Salehiniya H (2018) Testicular cancer in the world: an epidemiological review. World Cancer Res J 5(4):e1180 [Google Scholar]

- Fung C, Fossa SD, Williams A, Travis LB (2015) Long-term morbidity of testicular cancer treatment. Urol Clin 42:393–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannen R, Bartsch JW (2018) Essential roles of telomerase reverse transcriptase hTERT in cancer stemness and metastasis. FEBS Lett 592:2023–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Hiyama K (2007) Telomere and telomerase in stem cells. Br J Cancer 96:1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim DY, Sun H (2019) Somatic malignant transformation of a testicular teratoma: a case report and an unusual presentation case reports in pathology. Article ID 5273607, 5 pages [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jourdan F et al (2003) Tissue microarray technology: validation in colorectal carcinoma and analysis of p53, hMLH1, and hMSH2 immunohistochemical expression. Virchows Arch 443:115–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattar E et al (2016) Telomerase reverse transcriptase promotes cancer cell proliferation by augmenting tRNA expression. J Clin Investig 126:4045–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R et al (2006) Prognostic significance of expression patterns of c-erbB-2, p53, p16INK4A, p27KIP1, cyclin D1 and epidermal growth factor receptor in oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a tissue microarray study. J Clin Pathol 59:631–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão R, Ahmad AE, Hamilton RJ (2019) Testicular cancer biomarkers: a role for precision medicine in testicular cancer. Clin Genitour Cancer 17:e176–e183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C et al (2004) Prognostic factors in resected stage I non–small-cell lung cancer: a multivariate analysis of six molecular markers. J Clin Oncol 22:4575–4583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magers MJ, Idrees MT (2018) Updates in staging and reporting of testicular cancer. Surg Pathol Clin 11:813–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti A et al (2002) Prediction of survival in stage I lung carcinoma patients by telomerase function evaluation. Lab Investig 82:729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM (2016) The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs—part a: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol 70:93–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LV, Vanner R, Dirks P, Eaves CJ (2012) Cancer stem cells: an evolving concept. Nat Rev Cancer 12:133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak R, Sikora K, Piętas A, Skoneczna I, Chrapusta SJ (2000) Germ cell-like telomeric length homeostasis in nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors. Oncogene 19:4075–4078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg J (2015) Hypogonadism and fertility issues following primary treatment for testicular cancer. In: Urologic oncology: seminars and original investigations 33:407–412 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Papaioannou N, Psalla D, Zavlaris M, Loukopoulos P, Tziris N, Vlemmas I (2009) Immunohistochemical expression of dogTERT in canine testicular tumours in relation to PCNA, ki67 and p53 expression. Vet Res Commun 33:905–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE, Toppari J (2018) Testicular cancer pathogenesis, diagnosis and endocrine aspects. In: Endotext [Internet]. MDText. com, Inc.,

- Richie JP (2006) Second cancers among 40,576 testicular cancer patients: focus on long-term survivors: Travis LB, Fossa SD, Schonfeld SJ, McMaster ML, Lynch CF, Storm H, Hall P, Holowaty E, Andersen A, Pukkala E, Andersson M, Kaijser M, Gospodarowicz M, Joensuu T, Cohen RJ, Boice JD Jr, Dores GM, Gilbert ES, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. In: Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, 24:171–172

- Saeednejad Zanjani L et al (2019a) Spheroid-derived cells from renal adenocarcinoma have low telomerase activity and high stem-like and invasive characteristics. Front Oncol 9:1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeednejad Zanjani L et al (2019b) Human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein expression predicts tumour aggressiveness and survival in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Pathology 51:21–31 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sanfrancesco JM, Trevino KE, Xu H, Ulbright TM, Idrees MT (2018) The significance of spermatic cord involvement by testicular germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 42:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M et al (2002) The differentiation status of primary gonadal germ cell tumors correlates inversely with telomerase activity and the expression level of the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of telomerase. BMC Cancer 2:32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Wright WE (2010) Telomeres and telomerase in normal and cancer stem cells. FEBS Lett 584:3819–3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shervington A, Lu C, Patel R, Shervington L (2009) Telomerase downregulation in cancer brain stem cell. Mol Cell Biochem 331:153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2020) Cancer statistics, 2020 CA: a cancer. J Clin 70:7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson A et al (2019) Diagnosis and treatment of early stage testicular cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 10.1097/JU.0000000000000318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WE, Piatyszek MA, Rainey WE, Byrd W, Shay JW (1996) Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev Genet 18:173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A, Cheng T, Zhang J, Trpkov K (2013) Testicular hilum and vascular invasion predict advanced clinical stage in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Mod Pathol 26:579–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachos I et al (2009) Predictive value of telomerase reverse transcriptase expression in patients with high risk superficial bladder cancer treated with adjuvant BCG immunotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:1169–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Znaor A et al (2019) Testicular cancer incidence predictions in Europe 2010–2035: a rising burden despite population ageing. Int J Cancer 147:820–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 叶哲伟, 陈晓春, 杨述华, 杨秀萍, 曾汉青, 谷龙杰, 鲁功成 (2004) Expression and effects of human telomerase RNA in testicular tumor 中华医学杂志: 英文版 117:941–943 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1: Isotype controls in immunohistochemistry staining for confirming nonspecific binding of primary antibody. In embryonal carcinomas (A), yolk sac tumors (B), teratomas (C), seminomas (D), adjacent normal tissue (E), and in benign tumor tissue (F)

Supplementary Fig. 2: Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free survival (PFS) based on hTERT protein expression level in non-seminomatous GCT. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that low levels of hTERT expression are not significantly related to (A) DSS and (B) PFS (P = 0.161, P = 0.148), respectively in non-seminomatous GCT samples

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed data during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.