Abstract

Background

Attrition is a challenge in parameter estimation in both longitudinal and multi-stage cross-sectional studies. Here, we examine utility of machine learning to predict attrition and identify associated factors in a two-stage population-based epilepsy prevalence study in Nairobi.

Methods

All individuals in the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) (Korogocho and Viwandani) were screened for epilepsy in two stages. Attrition was defined as probable epilepsy cases identified at stage-I but who did not attend stage-II (neurologist assessment). Categorical variables were one-hot encoded, class imbalance was addressed using synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) and numeric variables were scaled and centered. The dataset was split into training and testing sets (7:3 ratio), and seven machine learning models, including the ensemble Super Learner, were trained. Hyperparameters were tuned using 10-fold cross-validation, and model performance evaluated using metrics like Area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, Brier score and F1 score over 500 bootstrap samples of the test data.

Results

Random forest (AUC = 0.98, accuracy = 0.95, Brier score = 0.06, and F1 = 0.94), extreme gradient boost (XGB) (AUC = 0.96, accuracy = 0.91, Brier score = 0.08, F1 = 0.90) and support vector machine (SVM) (AUC = 0.93, accuracy = 0.93, Brier score = 0.07, F1 = 0.92) were the best performing models (base learners). Ensemble Super Learner had similarly high performance. Important predictors of attrition included proximity to industrial areas, male gender, employment, education, smaller households, and a history of complex partial seizures.

Conclusion

These findings can aid researchers plan targeted mobilization for scheduled clinical appointments to improve follow-up rates. These findings will inform development of a web-based algorithm to predict attrition risk and aid in targeted follow-up efforts in similar studies.

Keywords: Machine learning, Attrition, Loss to follow-up, Urban settlements, Epilepsy, Prevalence, Surveillance

Background

Epilepsy is among the most common neurological disorders, affecting over 50 million people worldwide and over 80 % of the cases are in low- and middle-income countries [1]. The World Health Organization in 2022 published the Intersectoral Global Action Plan (IGAP) on epilepsy and other neurological disorders which outlines five strategic objectives including to strengthen public health approach to epilepsy (strategic objective 5). One of the key global targets under strategic objective (SO) 5 of IGAP is to increase epilepsy service coverage by 50 % by 2031. The denominator to compute service coverage is the number of people with epilepsy (prevalence). Accurate estimation of prevalence for epilepsy is therefore important to contribute effective measurement of progress towards IGAP goals. It is also important for evidence-based decisions on policy and national planning of epilepsy services.

Estimation of prevalence of epilepsy in urban settlements is a subject of active research. Often, the designs used to estimate prevalence of epilepsy involves multiple stages including household listing, household level screening and assessment by a specialist at the health facility [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. A prevalence estimate is defined as the number of participants confirmed to have epilepsy in the last stage of screening which in most cases is the assessment by a neurologist [2]. Prevalence estimates are usually obtained using data from sample surveys, population-based surveys, or longitudinal population cohort studies. However, data from such studies tend to suffer a number of challenges such as interviewer bias, non-response and attrition. Data cleaning and robust study methodology can help mitigate some of these challenges. Attrition, also known as loss to follow-up (LTFU) or drop-outs, however has been shown to be a constant challenge in studies involving multiple measurements such as longitudinal studies or multi-stage cross-sectional studies. Attrition often results to data missing for the participants on some key variables in subsequent timepoints. This can be addressed by determining participants at higher risk of attrition and designing targeted follow-up and mobilization strategies to improve follow-up rates.

In studies measuring the prevalence of epilepsy, attrition occurs when subjects identified in the first stage fail to participate in the subsequent stages. Depending on the sensitivity of the screening tool used at the first stage, it follows that probability of those screened as positive in the first stage being confirmed as having epilepsy is high. This means if a subset of the probable cases is LTFU, then the chances of underestimating prevalence increase. It has been shown that differing attrition rates between study groups or different socio-demographic profiles of the subjects may affect internal validity and generalizability of results [[6], [7], [8]]. Attrition tends to be higher in urban areas compared to rural areas, because of relocation (migration), work commitments or declining consent [4,9,10]. While there is no cutoff established in the literature as an acceptable proportion of missing data in a dataset for a valid and accurate statistical inference, some studies have reported that a missing data proportion of 5 % or less may be inconsequential [11]. However, while the overall missing proportion may be small, disproportionate missingness among different groups in the dataset may increase risk of bias. More recent studies have suggested that statistical inference is likely to be biased when more than 10 % of data are missing [12,13]. However, this may not always be the case depending on several factors including the study design, underlying types of the missing data (missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR) or missing not at random (MNAR)), the analytical approach used to account for the missing data. Estimates can also be biased even with low attrition depending on how attrition rate is correlated with baseline and follow-up variables [14]. There are a number of methods to account for missing data, the most common recommended is multiple imputation (MI) and maximum likelihood estimation [2,4,8,11,[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. Assuming the data are MAR, fitting models for effective multiple imputation requires that all variables included in the scientific model be also included in the MI model [11]. It is therefore important to establish factors associated with its missingness.

Studies on factors associated with attrition in the literature have focused more on longitudinal studies and studies for patients enrolled on long-term care and treatment programs. The most common include studies on attrition for patients enrolled on tuberculosis [7,9] and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) programs [6,21,22]. These studies have mostly used traditional approaches to determine factors associated with LTFU, with the most common method used being logistic regression [23,24]. These classical theory-based models are however constrained by independence and linearity assumptions which may not adequately represent the complex systems regarding relationships between outcomes and predictors [25,26].

Predictive models such as advanced machine learning prediction algorithms are able to address limitations of logistic regression. Machine learning is a field of data science that uses computer systems to identify patterns in data using algorithms and statistical models and predict outcomes or draw inferences. Machine learning algorithms are classified under four broad categories namely supervised machine learning, unsupervised machine learning, semi-supervised machine learning and reinforcement learning. Further details about the types of machine learning can be found in JavaTpoint [27]. This study focuses on prediction (also known as classification) models. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly becoming popular for modeling and predicting outcomes given a set of covariates. The common machine learning prediction algorithms include random forest, naïve Bayes, decision trees, gradient boosting machines, extreme gradient boost, logistic model and support vector machines.

Machine learning algorithms have the ability to quickly identify patterns and trends from large volumes of datasets that is then used for prediction. For instance, these techniques have been applied to aid in clinical decision making [28,29] and development of diagnostic applications [30], identification of gastrointestinal predictors for the risk of COVID-19 related hospitalizations [31] among other examples. To the best of our knowledge however, performance of machine learning predictive models for attrition in epilepsy studies has not been studied. Additionally, there are also limited studies that have looked at factors associated with high attrition for participants screened for epilepsy in urban settlements.

In this paper, we determine utility of using machine learning to model and predict risk for attrition in a two-stage population-based epilepsy prevalence study in Nairobi. We also determine predictive factors for attrition among participants screened for epilepsy. We hypothesize that socio-demographic characteristics of participants collected at the first stage of the screening can predict those at risk of being LTFU and this understanding can help researchers plan individualized targeted mobilization for scheduled follow-up visits or future clinical appointments.

Materials and methods

Study setting

This study was conducted in the two informal settlements, Viwandani and Korogocho, constituting the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS). Like most other urban informal settlements in Nairobi, Viwandani and Korogocho are characterised by lack of basic infrastructure, poor sanitation, overcrowding, high unemployment rate, poverty, and inadequate health infrastructure. Epilepsy studies have been conducted more predominantly in rural settings. This site was selected because it represents urban poor settlements in Nairobi. Viwandani is more mobile population where most residents are workers of the nearby companies in the industrial area of Nairobi. Korogocho is a more settled population where most residents have stayed there all their life. The two settings provide a good environment to study attrition in urban settings, the subject of this paper. Detailed information about the NUHDSS is published elsewhere [32,33].

Study design

This study is embedded under the Epilepsy Pathway Innovation in Africa (EPInA) project conducted in Nairobi and Kilifi, Kenya; Mahenge, Tanzania and Accra, Ghana (Protocol reference: NIHR200134) [34]. This was set up to improve epilepsy treatment pathways, including prevention, diagnosis, treatment and awareness in Africa. The study was led by the University of Oxford and conducted by a consortium of partners, which included the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) leading the NUHDSS in Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute-Wellcome Trust (KEMRI-WTRP) leading the Kilifi site in Kenya, University of Ghana leading the Accra site in Ghana and National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) leading the Mahenge site in Tanzania.

The data used in this study come from a multi-stage cross-sectional population-based epilepsy prevalence survey (census) conducted in the NUHDSS in Nairobi. The survey had two stages of screening patients for epilepsy. In the first stage, trained field interviewers administered a standardized validated screening questionnaire with 14 items [33] to the head of household or an adult representative in the household to identify persons with history of epilepsy. Socio-demographic characteristics of all members of the household were collected at this stage, including age, sex, education level, employment status, phone ownership and marital status. Participants identified as probable cases of epilepsy in the first stage were then be invited for assessment by the neurologist at a nearby facility (second stage). The participants were invited through scheduled appointments, and those who missed appointments were physically traced using confidential contact and residential information they provided in the first stage. The first stage of screening was conducted between 21st September 2021 and 21st December 2021, and the second stage between 14th April 2022 and 6th August 2022.

The dataset

The entire EPInA data set in the Nairobi site consisted of 56,425 participants. In this study, we analyzed data consisting of participants who were screened as possible cases of epilepsy (N = 1126) in the first stage of screening (at household level), of whom 253 were LTFU at the second stage (assessment by neurologist at the clinic). The outcome measure of the study was attrition, defined as participants who were identified as possible cases in the first stage of screening but were not assessed by a neurologist in the second stage because of withdrawing consent, unavailability or migration. These variables were collected in the first phase of the study. Table 1 provides an overview of the classification of the variables considered in the study. (See Table 2.)

Table 1.

Variables definition.

| Variable | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Outcome | |

| Attrition: defined as number of participants who were identified as possible cases in the first stage of screening but were not assessed by a neurologist in the second stage because of withdrawing consent, unavailability or migration | Binary outcome coded 1 if not observed due to attrition, and 0 if observed (that is, completed the survey) |

| Predictors | |

| Age of the participant | Categorized as 0–5 years, 6–12 years, 13–18 years, 19–28 years, 29–49 years and 50 years or older |

| Sex of the participant | Binary variable coded as 0 (Female) and 1 (Male) |

| Education level of the participant | Categorical variable coded as 0 (no formal education), 1 (Primary), 2 (Secondary) and 3 (Post-secondary) |

| Marital status of the participant | Categorical variable coded as 0 (not married/single), 1 (Married), 2 (Separated/Divorced) |

| Employment status of the participant | Categorical variable coded as 0 (Not unemployed), 1 (Full time or part-time employed), 2 (Self-employed) and 3 (Informal employment) |

| Site/location | Residential location of the participant (0 for Korogocho and 1 for Viwandani) |

| Date of first screening used to define duration between first stage of screening and second stage | Generated a categorical variable for months ranging from 4, 5, 6, and 7 months after first screening. |

| Phone ownership | Coded as 1 for Yes and 0 for No |

| History of having convulsive epilepsy or seizures | Coded as 1 for Yes and 0 for No |

| History of having non-convulsive epilepsy or seizures | Coded as 1 for Yes and 0 for No |

Notes:Detailed list of screening questions used for convulsive/non-convulsive seizures is published here [35] and also shown in the supplementary material (Appendix 1, Table A.1).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of residents of Korogocho and Viwandani urban informal settlements in Nairobi identified as possible cases during the first phase of the household survey.

| Korogocho |

Viwandani |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (=349) |

(=777) |

(=1126) |

|

| count (%) | count (%) | count (%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 178 (51.0) | 400 (51.5) | 578 (51.3) |

| Female | 171 (49.0) | 377 (48.5) | 548 (48.7) |

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 25 (13–36) | 28 (20–39) | 27 (17–38) |

| Age groups (years) | |||

| 0–5 | 36 (10.3) | 51 (6.6) | 87 (7.7) |

| 6–12 | 49 (14.0) | 63 (8.1) | 112 (9.9) |

| 13–18 | 43 (12.3) | 69 (8.9) | 112 (9.9) |

| 19–28 | 78 (22.3) | 220 (28.3) | 298 (26.5) |

| 29–49 | 106 (30.4) | 313 (40.3) | 419 (37.2) |

| 50 or older | 37 (10.6) | 61 (7.9) | 98 (8.7) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Less than primary/No formal education | 140 (40.1) | 164 (21.1) | 304 (27) |

| Primary | 132 (37.8) | 316 (40.7) | 448 (39.8) |

| Secondary | 43 (12.3) | 213 (27.4) | 256 (22.7) |

| Post-secondary | 6 (1.7) | 35 (4.5) | 41 (3.6) |

| Employment | |||

| Not employed | 104 (44.8) | 196 (31.9) | 300 (35.4) |

| Full-time or part time employed | 17 (7.3) | 131 (21.3) | 148 (17.5) |

| Self-employed | 38 (16.4) | 117 (19.0) | 155 (18.3) |

| Informal employment | 73 (31.4) | 171 (27.8) | 244 (28.8) |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 92 (26.4) | 154 (19.8) | 246 (21.8) |

| Married/Cohabiting | 89 (25.5) | 351 (45.2) | 440 (39.1) |

| Separated | 51 (14.6) | 110 (14.2) | 161 (14.3) |

| Divorced | 117 (33.5) | 162 (20.8) | 279 (24.8) |

Data preprocessing

We split the data into training set and testing set in the ratio of 7:3, training the models on the identified important features. This ratio provides a balanced trade-off between having enough data for training the model and retaining sufficient data for model evaluation. The two datasets were balanced on site, sex, age, education level, employment status and marital status. This ratio was chosen to enable robust model training and leave enough data for model validation. Categorical variables were recoded using one-hot encoding principle because some machine learning algorithms cannot operate with categorical data directly but rather require them to be transformed to numeric variables. The prevalence of the outcome (attrition) was 23 % resulting to an imbalanced dataset which could make the models training biased towards the majority class. This problem was addressed using synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) from R's smotefamily() library [25,36]. SMOTE works by artificially generating new examples of minority class of the target variable using their nearest neighbours [36], and has previously been successfully used to address similar problem [25].

Statistical methodology

Mathematical representation

Let Y be a random variable such that denotes probability of being LTFU and otherwise. The focus of this study is to identify models that predict probability of being LTFU (attrition) given a set of predictors Thus, is a dichotomous dependent variable, that is,

Gradient boosting machine (GBM), naïve Bayes, random forest, extreme gradient boost (XGB), support vector machine (SVM), decision tree and logistic regression model are considered and compared. Statistical representations of the machine learning algorithms are presented below and more information can be found in [25,[37], [38], [39]].

Machine learning algorithms

In this subsection, we provide a brief overview of the machine learning classification algorithms that could be considered for handling missing data due to attrition. They are a special case of single imputation methods such as regression imputation, and can be used alongside methods such as inverse probability weights or multiple imputation. Detailed mathematical formulations and derivation are detailed in the provided in JavaTpoint [27].

Logistic regression

Logistic regression is a supervised learning algorithm used for binary classification problems. It models the probability that a given input belongs to a certain class using the logistic function. The mathematical representation of logistic regression algorithm involves estimating the parameters of the logistic function through maximum likelihood estimation [40].

Let represent the input features and represent the binary class label (either 0 or 1). Logistic regression models the probability that a given input belongs to class 1 using the logistic function

| (1) |

where is the weight vector, is the bias term and is the base of the natural logarithm (Euler's number).

The logistic function maps the linear combination of input features and model parameters to the range [0,1], representing the probability of belonging to class 1. The parameters and are estimated through maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) or other optimization techniques to minimize the logistic loss function defined as as the average negative log-likelihood of the Bernoulli distribution

| (2) |

where is the total number of observations in the training set, is the feature vector for the observation in the training set and is the outcome variable for the observation in the training set. The parameters and are then used to predict the probability of class 1 for new input data (test set).

This formulation captures the essence of how logistic regression models the probability of belonging to a certain class using the logistic function and estimates the parameters through maximum likelihood estimation.

Naïve Bayes

Naïve Bayes is a probabilistic classifier based on Bayes' theorem with an assumption of independence between features. Despite its simplicity, it often performs well in practice, especially for text classification tasks [41].

Let represent the input features (predictors), index the number of observations in the training set and be the outcome/target variable. The mathematical representation involves computing the posterior probability of each class given the input features using Bayes' theorem

| (3) |

where:

-

•

is the posterior probability of class given input features .

-

•

is the prior probability of class .

-

•

is the likelihood of observing features given class .

-

•

is the evidence or marginal likelihood of observing features .

The naïve Bayes algorithm assumes that features are conditionally independent given the class label . In particular, the likelihood is defined as:

| (4) |

and is defined as:

| (5) |

Naïve Bayes classifier often uses specific probability distributions to model , such as Gaussian distribution for continuous features, Bernoulli distribution for binary features, or multinomial distribution for categorical features. The class with the highest posterior probability is assigned as the predicted class

This formulation captures the essence of how naïve Bayes classifier computes the posterior probabilities of each class given the input features using Bayes' theorem with the assumption of feature independence.

Decision tree

Decision trees works by partitioning the feature space into regions based on feature values, with each region corresponding to a specific class or predicted value [37]. It involves recursively partitioning the feature space into regions based on binary splitting criteria, such as Gini impurity or information gain.

Given a training dataset , where represents the features and represents the class labels, a decision tree recursively partitions the feature space into disjoint regions and assigns a class label to each region.

Let represent the region of the feature space. For classification problems, the prediction of a decision tree is determined by the class label assigned to the region where the input falls. More precisely,

| (6) |

where is the class label associated with region .

The partitioning process continues until certain stopping criteria are met (e.g., maximum depth of the tree, minimum number of samples in a node, purity threshold). This formulation captures the essence of how a Decision Tree partitions the feature space and assigns class labels to each region based on the input features for a classification problem. The final prediction for a given input is determined by the majority class or average value of the samples within the corresponding region.

Random forest

Random forests are an ensemble learning method that constructs a multitude of decision trees during training and outputs the mode of the classes (classification) or the average prediction (regression) of the individual trees [37]. It involves aggregating the predictions of multiple decision trees, each trained on a random subset of the training data and a random subset of features.

Let be the total number of decision trees in the random forest model. Each decision tree is trained on a random subset of the training data and a random subset of features.

For classification tasks, the final prediction is determined by voting over the predictions of all decision trees. The class with the most votes is chosen as the predicted class, that is,

| (7) |

where returns the most common class label among the predictions of all decision trees.

The randomness introduced during training, including random sampling of the training data and random feature selection for each tree, helps to decorrelate the individual trees and reduce overfitting. As a result, random forests often generalize well to unseen data and are robust to noise in the training data.

This formulation captures the essence of how Random Forests combine the predictions of multiple decision trees to make accurate predictions for both regression and classification tasks. The final prediction is determined by averaging (regression) or voting (classification) over the predictions of individual trees.

Support vector machines

Support Vector Machines (SVM) aims to find the hyperplane that best separates the data points of different classes in the feature space while maximizing the margin between the classes [42]. It involves finding the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between the classes. This is achieved by solving a convex optimization problem, typically using the method of Lagrange multipliers. In the case of non-linearly separable data, SVM can use kernel tricks to map the input data into a higher-dimensional space where linear separation is possible.

Given a training dataset , where represents the features and represents the class labels (either or ), SVM aims to find the optimal hyperplane that separates the data points of different classes while maximizing the margin between the classes.

Let be the weight vector and be the bias term. The decision function of SVM is given by

| (8) |

where the sign function defined as

is used to determine the class label, where indicates that the point belongs to one class and that the point belongs to the other class.

The objective of SVM is to find the optimal hyperplane parameters and that maximize the margin while correctly classifying all training data points. This can be formulated as the following optimization problem

subject to the constraints

The constraints ensure that each data point is correctly classified by the decision function and lies on the correct side of the hyperplane. The margin between the hyperplane and the closest data points (support vectors) is , which is maximized by minimizing .

In the case of non-linearly separable data, SVM can use kernel tricks to map the input data into a higher-dimensional space where linear separation is possible. The optimization problem remains the same, but the decision function becomes

| (9) |

where are the Lagrange multipliers and is the kernel function that computes the inner product of the mapped feature vectors and . That is,

where refers to the mapping of the input data into a higher-dimensional feature space.

Gradient boosting machine

Gradient boosting machine (GBM) is an ensemble learning technique that builds a strong predictive model by sequentially adding weak learners (typically decision trees) to correct the errors of previous models. GBM minimizes a loss function using gradient descent. The mathematical formulation of gradient boosting involves minimizing a loss function by iteratively adding weak learners (decision trees) to the ensemble.

Let be the training data points, where is the features (predictors) for the individual in the training set, and be the target outcome variable. Let be the current ensemble model, initially denoted , and is a weak learner (typically decision tree), with parameters . Then, is the loss function measuring the difference between the true target and the predicted value .

Each weak learner is trained to predict the residual errors of the ensemble, and the predictions of all learners are combined to obtain the final prediction. The ensemble is built in a stage-wise manner, where each new learner is trained to minimize the loss function of the entire ensemble. The final model is the sum of weak learners weighted by some learning rate , as shown in the model below

| (10) |

The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Step 1: Initialize .

Step 2: For .

-

(i)

Compute the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current ensemble model.

-

(ii)

Compute the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current ensemble model.

| (11) |

-

(iii)

Fit a weak learner (e.g., decision tree) to the negative gradient .

| (12) |

-

(iv)

Compute the optimal step size by minimizing the loss function with respect to the step size:

| (13) |

-

(v)

Update the ensemble model:

| (14) |

The above steps are repeated until convergence or until a predefined number of iterations is reached. This formulation ensures that each weak learner is fitted to the residuals of the previous ensemble, allowing the model to learn complex relationships between features and target variables. The learning rate controls the contribution of each weak learner to the ensemble, and it is a hyperparameter that needs to be tuned during model training.

Extreme gradient boost

Extreme gradient boost (XGB) is an optimized implementation of the gradient boosting algorithm that is known for its efficiency, scalability, and performance [43]. XGB introduces several enhancements over traditional gradient boosting, including regularization, parallelized tree construction, and handling missing values. It is similar to traditional gradient boosting but includes additional regularization terms in the objective function to prevent overfitting. XGB also employs a novel tree construction algorithm that prunes trees during the building process to improve computational efficiency.

Ensemble learning with super learner

Van der Laan et al. [44] recommended a more superior approach, called the Super Learner. This approach seeks to improve prediction performance by optimally combining predictions from multiple machine learning algorithms. It uses weighted combination of individual models, where the weights are determined through cross-validation to minimize prediction error. This method has been shown to outperform the individual learners included in the ensemble.

The prediction of the ensemble Super Learner, , is computed as

| (15) |

where represents the prediction from the base learner, is the weight assigned to the learner, is the total number of base learners, and . The weights are estimated through cross-validation to minimize the prediction error, typically using a loss function such as the mean squared error for continuous outcomes or the negative log-likelihood for binary outcomes.

For this study, the base learners, which included logistic, naïve Bayes, decision tree, random forest, support vector machines, gradient boosting machine and extreme gradient boost, were trained independently and the best three models included in the ensemble Super Learner model construction.

Statistical analysis

The variables considered for inclusion in the model are presented in Table 1. We evaluated associations between the covariates and attrition using test and included those that were associated with attrition, that is, had a p-value, at 95 % confidence level [45]. This was combined with selecting variables intuitively for ease of interpretation and application.

We trained seven machine learning algorithms (base learners), including logistic regression, decision tree, naïve Bayes, random forest, gradient boosting machine, extreme gradient boost, and support vector machine and the ensemble Super Learner model. To tune the hyperparameters, training data was used to perform 10-fold cross-validation. To evaluate the predictive performance of the models, we performed bootstrapping with 500 replications as recommended by Efron and Tibshirani [46]. In each replication, test data were sampled with replacement to generate the bootstrap samples. Predictive performance metrics, including accuracy, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, Brier score, and F1 score were computed for each bootstrap sample. The results were then summarized using descriptive statistics, including quantiles. The 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were computed for each metric across the 500 bootstrap samples. The definitions of the evaluation metrics are provided below.

Accuracy

| (16) |

Accuracy ranges from 0 to 1, where higher values means greater accuracy.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve plots sensitivity (true positive rate) against 1-specificity (false positive rate) at various threshold values. The area under the curve (AUC) ranges from 0 to 1, where an AUC of 0.5 represents a model with no discriminative ability (equivalent to random guessing), and higher AUC values indicate better model performance. An AUC of greater than 0.7 is commonly recommended for a model to be considered acceptable [47].

Brier score

| (17) |

where is the number of instances, is the true class label (0 or 1), and is the predicted probability of class 1. Models with Brier scores are deemed best performing.

F1 score

| (18) |

where Precision is the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions, and Recall (also known as True Positive Rate or Sensitivity) is the proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive instances. F1 score ranges from 0 to 1. Higher F1 indicates a better performing model, mostly recommended to be [48].

The cut-off points that maximized sensitivity and specificity of the models were chosen based on Youden's J statistic, given by

| (19) |

The best performing models were selected using AUC and F1 score. The three best performing models from the internal validation were further evaluated on the original dataset (the dataset before applying SMOTE) to test how well the models can predict actual data. All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.3) [49].

Results and discussion

Empirical results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table. The majority of the participants (69 %) were from Viwandani. There was an even distribution by sex in both sites and the median age was 27 years (interquartile range: 17–38). Slightly over a third had primary education. About 21 % of the participants from Viwandani were in full time or part-time employment, compared to 7 % from Korogocho. More than half of the participants were married or living together with a partner. There were differences in the size of the households between the two sites with 58 % of Korogocho participants being from larger households (4 or more members) compared to 45 % from Viwandani.

Fig. 1 presents important features based on scores for inclusion in training the models for prediction of attrition.

Fig. 1.

Feature importance for prediction based on scores

Thus, features with p-value were included in the prediction model. This included socio-demographic features namely, age, sex site, duration post first screening, household size, education level, employment status, relationship of the patient with the head of the household, marital status and phone ownership. Epilepsy seizure related features identified during screening that had p-value were having had seizures with febrile illness or fever, focal seizures with impaired awareness and falling to the ground and losing bladder control.

Table 3 presents bivariate relationships between the selected features and attrition. A total of 253 (23 %) participants were lost to follow-up in the second stage of the screening. The major reasons for attrition were outmigration (n = 48 (19 %)), withdrawing consent (n = 22 (8 %)) and inability to trace the households or the individuals (n = 185 (73 %)). Factors associated with attrition included location, age, sex, education level, employment status, marital status and relationship to the head of the household). Overall, attrition was higher in Viwandani compared to Korogocho, among male compared to female, among teenagers (13–18 years) and young adults (19–28 years), among male participants, among those who had never married, those with higher education (completed primary school or higher), those in smaller household sizes (<3 members) and those in some form of employment (full- or part-time or informal) compared to those who were not employed or self-employed. Further, attrition was higher among those who were screened in December 2021 (34 %) compared to those in who were screened earlier (September, October and November 2021).

Table 3.

Bivariate analysis to examine association between selected features with attrition.

| Factor | N | Completed the study () | Attrition () | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||

| Korogocho | 349 | 313 (89.7) | 36 (10.3) | |

| Viwandani | 777 | 560 (72.1) | 217 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| Age categories | ||||

| 0-5y | 87 | 70 (80.5) | 17 (19.5) | |

| 6-12y | 112 | 95 (84.8) | 17 (15.2) | |

| 13-18y | 112 | 87 (77.7) | 25 (22.3) | |

| 19-28y | 298 | 202 (67.8) | 96 (32.2) | |

| 29-49y | 419 | 336 (82.0) | 74 (18.0) | |

| 50y or older | 98 | 83 (84.7) | 15 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Household size | ||||

| One | 241 | 175 (72.6) | 66 (27.4) | |

| Two or three | 368 | 269 (73.1) | 99 (26.9) | |

| 4 to 7 | 435 | 361 (83.0) | 74 (17.0) | |

| >7 | 82 | 68 (82.9) | 14 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 578 | 427 (73.9) | 151 (26.1) | |

| Female | 548 | 446 (81.4) | 102 (18.6) | 0.003 |

| Education | ||||

| <Primary or no formal education | 304 | 255 (83.9) | 49 (16.1) | |

| Primary | 448 | 345 (77.0) | 103 (23.0) | |

| Secondary | 256 | 181 (70.7) | 75 (29.3) | |

| Postsecondary | 41 | 30 (73.2) | 11 (26.8) | 0.003 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 246 | 177 (72.0) | 69 (28.0) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 440 | 330 (75.0) | 110 (25.0) | |

| Separated | 440 | 136 (84.5) | 25 (15.5) | 0.013 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Not employed | 300 | 234 (78.0) | 66 (22.0) | |

| FT or PT employed | 148 | 105 (70.9) | 43 (29.1) | |

| Self-employed | 155 | 129 (83.2) | 26 (16.8) | |

| Informal employment | 244 | 175 (71.7) | 69 (28.3) | 0.022 |

| Relationship to head of household | ||||

| Self | 504 | 373 (74.0) | 131 (26.0) | |

| Spouse | 181 | 147 (81.2) | 34 (18.8) | |

| Child | 364 | 296 (81.3) | 68 (18.7) | |

| Other relative | 77 | 57 (74.0) | 20 (26.0) | 0.036 |

| Duration after first screening | ||||

| Four months | 174 | 115 (66.1) | 59 (33.9) | |

| Five months | 308 | 241 (78.3) | 67 (21.8) | |

| Six months | 488 | 385 (78.9) | 103 (21.1) | |

| Seven months | 156 | 132 (85.6) | 24 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| At least 1 HH member owns mobile phone | ||||

| No | 418 | 338 (80.9) | 80 (19.1) | |

| Yes | 708 | 535 (75.6) | 173 (24.4) | 0.047 |

| Focal seizures with impaired awareness | ||||

| No | 759 | 574 (75.6) | 185 (24.4) | |

| Yes | 367 | 299 (81.5) | 68 (18.5) | 0.033 |

| Falling down and losing bladder control | ||||

| No | 909 | 693 (76.2) | 216 (23.8) | |

| Yes | 217 | 180 (82.9) | 37 (17.1) | 0.042 |

| Seizures with febrile illness or fever | ||||

| No | 834 | 633 (75.9) | 201 (24.1) | |

| Yes | 292 | 240 (82.2) | 52 (17.8) | 0.033 |

Performance metrics from all the seven models and the ensemble Super Learner constructed from random forest, SVM and extreme gradient boost are presented in Table 4. All the models performed relatively well with AUC > 0.75. In particular, however, extreme gradient boost (XGB), random forest and support vector machine (SVM) and gradient boosting machine (AUC > 0.90 and accuracy >0.88) performed better than logistic regression, naïve Bayes and decision tree models (AUC < 0.85, accuracy <0.80). Gradient boosting machine (GBM) however had a slightly lower sensitivity (0.76) compared to random forest (0.92), XGB (0.89) and SVM (0.89). Decision tree had a modest accuracy of 0.79, AUC 0.83, and specificity 0.90 but had a relatively lower sensitivity of 0.66. Logistic regression had accuracy of 0.69, AUC 0.75, sensitivity of 0.79 and low specificity of 0.59. Naïve Bayes algorithm had accuracy of 0.69, AUC 0.75, sensitivity 0.74 and a low specificity of 0.66. Overall, among the base learners, random forest seemed the best performing model (AUC = 0.98, accuracy = 0.95 and F1 score = 0.94), followed very closely by XGB (AUC = 0.96, accuracy = 0.91 and F1 score = 0.90) and SVM (AUC = 0.93, accuracy = 0.93 and F1 score = 0.92).

Table 4.

External evaluation of performance of the machine learning classification models using the bootstrap samples of the test data.

| AUC | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | 0.79 (0.79–0.79) | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) | 0.82 (0.69–0.91) | 0.59 (0.48–0.72) | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.75 (0.72–0.79) | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) | 0.74 (0.60–0.85) | 0.66 (0.53–0.79) | 0.67 (0.61–0.71) |

| Random forest | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) |

| Decision tree | 0.83 (0.80–0.87) | 0.79 (0.76–0.83) | 0.66 (0.59–0.73) | 0.90 (0.84–0.93) | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) |

| Support vector machine | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 0.89 (0.85–0.93) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) |

| Gradient boosting machine | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | 0.85 (0.83–0.88) | 0.76 (0.69–0.82) | 0.93 (0.87–0.97) | 0.82 (0.78–0.85) |

| Extreme gradient boost | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | 0.89 (0.85–0.92) | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) | 0.90 (0.87–0.92) |

| Super Learner | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | 0.91 (0.87–0.94) | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) |

Notes: Values in brackets are 95 % confidence intervals from 500 bootstrap samples.

The ensemble Super Learner model, which combined predictions from three of the best performing models, namely random forest, XGB and SVM, was also included in the comparison (Table 4). The ensemble Super Learner model performed very similarly with the the three best performing base learners across all the metrics (AUC = 0.97, accuracy = 0.92 and F1 score = 0.91).

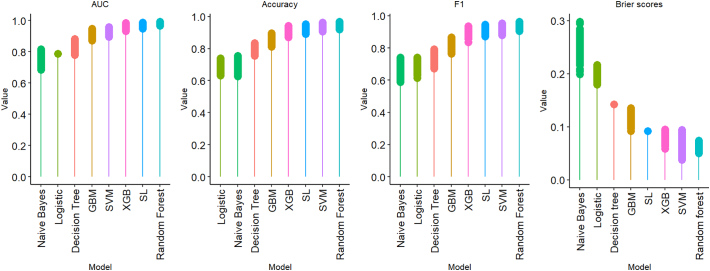

Fig. 2 visualizes the four important metrics used in the evaluation of the models, recorded from the 500 bootstrap samples. The ROC curves are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix 2, Fig. A.1).

Fig. 2.

Visualization of model performance metrics - AUC, F1, Accuracy and Brier scores.

Further to AUC, F1 and accuracy, random forest had the lowest average Brier score (<0.1) followed by XGB and SVM and naïve Bayes had the highest Brier score (>0.2). Overall, random forest had the best performance followed by XGB and SVM respectively. Random forest and extreme gradient boost were picked for further evaluation as shown below. While XGB and SVM performed similarly in sensitivity and F1 scores, XGB had lower Brier score and better AUC than SVM. And while SVM and GBM had similar AUC and Brier score, SVM had better sensitivity.

While most of the models performed satisfactorily based on the F1 > 0.7, the best performing model that optimized the three main metrics (Accuracy, AUC, F1 score) used to assess performance was random forest followed by XGB and SVM. However, based on the Brier score, random forest and XGB had better scores compared to SVM. Gradient boosting machine may also be considered for further evaluation.

Performance of the three best performing models and the Super Learner were further evaluated to determine how well they predict the outcomes in the loss to follow-up data (the dataset before applying SMOTE). Table 5 shows the confusion matrices, accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, specificity of the four models. The methods are based on a dichotomous dependent variable, where denotes probability of being LTFU due to attrition, and denotes probability of completing the survey. Thus, in Table 5, the event is indicated as a yes and the event is indicated as a no.

Table 5.

Performance of best performing models on the loss to follow-up data (the dataset before applying SMOTE).

| Confusion Matrix |

Accuracy |

AUC |

F1 |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | ||||||||

| Random forest | Predicted | No | Yes | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.92 |

| No | 804 | 37 | ||||||

| Yes | 69 | 216 | ||||||

| Total | 873 | 253 | ||||||

| XGB | Predicted | No | Yes | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| No | 736 | 43 | ||||||

| Yes | 137 | 210 | ||||||

| Total | 873 | 253 | ||||||

| SVM | Predicted | No | Yes | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.96 |

| No | 837 | 48 | ||||||

| Yes | 36 | 205 | ||||||

| Total | 873 | 253 | ||||||

| Super Learner | Predicted | No | Yes | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.87 |

| No | 760 | 41 | ||||||

| Yes | 113 | 212 | ||||||

| Total | 873 | 253 | ||||||

Notes:Observed values;numbers predicted by the model.

Random forest and support vector machine had better prediction, correctly predicting 91 % and 93 % of the data respectively and had F1 scores of 0.80 and 0.83 respectively. Random forest and the Super Learner however had better AUC of 95 % and 93 % respectively. Extreme gradient boost predicted 84 % of the data correctly (accuracy) with AUC of 91 % and F1 score of 0.70. Overall, random forest, extreme gradient boost, support vector machine and the ensemble Super Learner constructed from the three base learners were found to be the best performing models for predicting attrition for patients screened for epilepsy in Nairobi.

We evaluated variable importance by examining the feature ranking by all the models. Variable importance measure gives an indication of important factors for predicting the outcome. Fig. 3 presents how each of the considered models ranked the features based on their contribution to prediction of the outcome and Fig. 4 features ranked in the top 10 by the three best performing models. In Fig. 3, the darker the color is for a particular feature the higher the rank is based on a specific model. Residential location, particularly being a resident of the Viwandani site, age, and sex (particularly being male) were ranked highly (rank 1, 2 or 3) by atleast four of the models including three of the best performing models (random forest and extreme gradient boost). Other features ranked in the top five by at least two of the best performing models are household size, having focal seizures with impared awareness and having secondary education.

Fig. 3.

Feature rank comparison across models.

Fig. 4.

Top 10 features based on importance ranking across the three best performing models.

Based on feature ranking from Fig. 3, Fig. 4 and the bivariate analysis in Table 3, male participants, participants from Viwandani (industrial area), those with post-primary education, had some form of employment (either formal or informal) and were either teens (13 to 18 years old) or young adults (19–28 years old), and were from from smaller households (1 to 3 members) had a higher risk of attrition. Among seizure related features, having experienced focal seizures with impaired awareness was ranked among the top 5 predictors by random forest, XGB and SVM. Triangulating with findings in Table 3, those who did not experience focal seizures with impaired awareness (24.4 %) were slightly more likely be lost to follow-up (attrition) compared to those who did (18.5 %). Another important feature ranked among the top 5 by three of the best performing models was duration after first screening. As highlighted in Table 3, the risk of attrition was higher among those screened in a more recent time compared to those screened in an earlier time period.

Discussion and conclusion

This study compared seven machine learning classification algorithms to predict attrition for patients screened positive for epilepsy. Our results showed that random forest, extreme gradient boost and support vector machine were the ‘best’ performing models whereas logistic regression and naïve Bayes performed poorly.

A similar study on predicting attrition in a population-based cohort of very preterm infants in Portugal also found that random forest performed better than logistic regression model [25]. In fact, random forest was found to have the best performance in a large study that evaluated 179 classifiers using 121 different datasets [50]. In the study, SVM with Gaussian kernel was second. The good performance of random forest over logistic regression for predictive models has also been demonstrated in other studies, including predicting suicide attempts [51], readmissions for patients with heart failure [52] and unplanned re-hospitalization of pre-term babies [53]. Other studies have, however, favored logistic regression model because of their superior clinical interpretation [30,54] and simplicity [23]. This is so because no classifier can always best fit all datasets.

There are not many other studies that have investigated the ability of machine learning to predict attrition in settings similar to ours and especially for epilepsy related studies, which limits our ability to robustly compare our findings with other studies. However, a study to determine factors predictive of patients at risk of being LTFU after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome estimated logistic regression model [23]. Further research to improve performance of logistic regression algorithm may be necessary because of its ease of interpretation, which is desired in practice. Another similar study was conducted to predict and prevent attrition of adult trauma patients in randomized control trials by Madden et al. [24]. The study also estimated a logistic regression model to determine participant characteristics associated with a higher risk of attrition. The study ( [23]), however, did not compare predictive ability of logistic regression and other machine learning algorithms.

Further, the results showed that most important socio-demographic factors for predicting risk of attrition among patients with epilepsy are residential location, age, sex, education, employment and duration since first screening. We found that attrition was higher in Viwandani (industrial area); among teenagers (13-18y years) and young adults (19–28 years), among males, among those with post-primary education; and among those in some form of employment (formal or informal) and among those from smaller households (1 to 3 members). These features are consistent with the type of population more likely to be found in Viwandani, which is located within the industrial area of Nairobi. In an updated profile of the NUHDSS, Wamukoya et al. [55], majority of the residents in Viwandani are between 19 and 49 years, most of whom are part-time or casual works in the surrounding industries. The population of people working in the industries is more predominantly male due to the manual work involved, which is likely to be manual labour [56]. Further, Viwandani is characterised by small household sizes compared to Korogocho [32]. This could be inferred that attrition in the Nairobi informal settlements is likely to be driven by how flexibly available the participant is during the scheduled appointment, which could be determined by the type of work the participant does. Another important factor considered in this study was the duration between the first screening and the follow-up. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that participants screened later (nearer to the start of the second stage) were actually more likely to be LTFU (attrition) compared to those screened earlier. This unexpected finding could be explained by the stigma associated with epilepsy where participants may prefer to take longer before going back to a facility for an appointment. Another potential reason could be the differences in the mobilization strategy where the participants who were screened earlier are targeted first before those that were screened more recently.

We also found that participants who experienced focal seizures with impaired awareness (also known as complex partial seizures) were less likely to be LTFU. This could be because individuals with complex partial seizures experience more noticeable or disruptive symptoms compared to those with focal aware seizures. This could prompt them to seek medical attention more diligently and adhere to treatment plans. The sudden onset of impaired awareness during these seizures significantly impacts daily activities, increasing the perceived need for consistent medical care [57]. While there is limited research linking specific seizure types to follow-up adherence directly, studies indicate that seizure severity and frequency influence patient engagement with healthcare services [58]. For instance, individuals experiencing more severe or frequent seizures are more likely to adhere to treatment and follow-up schedules to achieve better seizure control. Conversely, patients with less severe or infrequent seizures may perceive their condition as less critical, leading to decreased adherence to follow-up appointments.

Most common reasons for attrition in this study were outmigration, withdrawing consent and inability to trace the households or the participants during the follow up mobilization. These are consistent with findings from previous studies [4,9,10]. However, there are not many epilepsy studies conducted in urban settings in general that have used machine learning methodology to study socio-demographic factors associated with attrition with whom we can compare our findings.

This paper has strengths. First, the data used in this study are from a population-based survey (census). This means nearly all potential reasons for one being LTFU in a similar urban settlement are considered. Urban settlements are characterised by high attrition due to migration or work commitments. While the data used in this study are from an urban setting, the models applied in this study can also be used to predict risk for attrition also in areas which may have relatively low attrition, and can include a wide range of covariates thought to be associated with attrition. The ML models evaluated in this study are general and can also predict low attrition. Second, to our knowledge, this is one of the few studies that have applied predictive models for attrition for patients screened for epilepsy in an urban setting using machine learning techniques.

A few limitations should however be considered while interpreting the results of this study. This study had a limited scope and focus, but the methodology can be replicated in other settings. The study was conducted in NUHDSS with only two informal settlements (Korogocho and Viwandani) and this may limit the generalizability of the findings to other areas that may have different socio-demographic characteristics and/or different migration patterns. We did not have the data from rural settings to compare our findings. In general, findings will depend on the prevailing socio-demograhic characteristics in a given rural or urban setting.

In conclusion, compared to the models evaluated in our study, random forest and extreme gradient boost models were found to have the most promising ability to predict risk of attrition for patients screened for epilepsy in Nairobi urban informal settlements. This study has demonstrated that given sufficient socio-demographic characteristics of participants at baseline, risk of attrition can be predicted using machine learning models. These models can aid researchers plan targeted mobilization for scheduled follow-up visits or future clinical appointments. Further, residential location, age, sex, education, employment, seizure severity and duration since first screening were identified as factors with most predictive value for increased risk of attrition. These findings suggest that regardless of when a participant was screened, or how soon the next clinical appointment is for a participant, effort should be made to mobilize each participant for their next clinical appointment with more attention to those in formal employment, those living in an industrial area with high migration rates, teenagers and young adults, and those with higher levels of education. Results of this study will be used to develop a web-based algorithm to aid researchers predict risk of attrition in similar settings.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by Scientific Ethics Review Unit (SERU) at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) (Reference Number: KEMRI/RES/7/3/1). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Funding

This research was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (grant number NIHR200134) using Official Development Assistance (ODA) funding. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Daniel M. Mwanga: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Isaac C. Kipchirchir: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. George O. Muhua: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Charles R. Newton: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Damazo T. Kadengye: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Charles R. Newton: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Daniel Mtai Mwanga: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Damazo T. Kadengye: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Daniel Nana Yaw: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding received from NIHR (indicated above) that supported this study through the EPInA project. We also thank the data collection team at both stages of the study and the Nairobi City County Health Department leadership for allowing the team to use the public health facilities in Nairobi to conduct the assessments. We recognize the technical input of Gabriel Davis Jones (University of Oxford), Ioana Duta (University of Oxford), Samuel Iddi (APHRC) and Steve Cygu (APHRC). The team also acknowledges the Epilepsy Pathway Innovation in Africa (EPInA) scientific committee for the leadership and support for this study and the whole EPInA team listed under the EPInA group below†.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloepi.2025.100183.

Contributor Information

Daniel M. Mwanga, Email: dmwanga@aphrc.org.

for EPInA Study Team:

Abankwah Junior, Albert Akpalu, Arjune Sen, Bruno Mmbando, Charles R. Newton, Cynthia Sottie, Dan Bhwana, Daniel Mtai Mwanga, Damazo T. Kadengye, Daniel Nana Yaw, David McDaid, Dorcas Muli, Emmanuel Darkwa, Frederick Murunga Wekesah, Gershim Asiki, Gergana Manolova, Guillaume Pages, Helen Cross, Henrika Kimambo, Isolide S. Massawe, Josemir W. Sander, Mary Bitta, Mercy Atieno, Neerja Chowdhary, Patrick Adjei, Peter O. Otieno, Ryan Wagner, Richard Walker, Sabina Asiamah, Samuel Iddi, Simone Grassi, Sloan Mahone, Sonia Vallentin, Stella Waruingi, Symon Kariuki, Tarun Dua, Thomas Kwasa, Timothy Denison, Tony Godi, Vivian Mushi, and William Matuja

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.WHO. Epilepsy. In: Epilepsy [Internet]. 9 Feb 2023. World Health Organization, url: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy, 2023.

- 2.Ngugi Anthony K., Bottomley Christian, Kleinschmidt Immo, Wagner Ryan G., Kakooza-Mwesige Angelina, Ae-Ngibise Kenneth, et al. Prevalence of active convulsive epilepsy in sub-saharan africa and associated risk factors: cross-sectional and case-control studies. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):253–263. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngugi Anthony K., Bottomley Christian, Kleinschmidt Immo, Sander Josemir W., Newton Charles R. Estimation of the burden of active and life-time epilepsy: a meta-analytic approach. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kariuki Symon M., Ngugi Anthony K., Kombe Martha Z., Kazungu Michael, Chengo Eddie, Odhiambo Rachael, et al. Prevalence and mortality of epilepsies with convulsive and non-convulsive seizures in Kilifi, Kenya. Seizure. 2021;89:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2021.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stelzle Dominik, Schmidt Veronika, Ngowi Bernard J., Matuja William, Schmutzhard Erich, Winkler Andrea S. Lifetime prevalence of epilepsy in urban tanzania–a door-to-door random cluster survey. eNeurologicalSci. 2021;24:100352. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2021.100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidze Larissa Kamgue, Faye Albert, Tetang Suzie Ndiang, Penda Ida, Guemkam Georgette, Ateba Francis Ndongo, et al. Different factors associated with loss to follow-up of infants born to hiv-infected or uninfected mothers: observations from the anrs 12140-pediacam study in Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharani Zatil Zahidah, Ismail Nurhuda, Yasin Siti Munira, Zakaria Yuslina, Razali Asmah, Demong Nur Atiqah Rochin, et al. Characteristics and determinants of loss to follow-up among tuberculosis (tb) patients who smoke in an industrial state of Malaysia: a registry-based study of the years 2013–2017. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):638. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristman Vicki L., Manno Michael, Côté Pierre. Methods to account for attrition in longitudinal data: do they work? A simulation study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:657–662. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-7919-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kizito Kibango Walter, Dunkley Sophie, Kingori Magdalene, Reid Tony. Lost to follow up from tuberculosis treatment in an urban informal settlement (kibera), Nairobi, Kenya: what are the rates and determinants? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105(1):52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamo Y., Dukessa T., Mortimore A., Dee D., Luintel A., Fordham I., et al. Non-communicable disease clinics in rural Ethiopia: why patients are lost to follow-up. Public Health Action. 2019;9(3):102–106. doi: 10.5588/pha.18.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer Joseph L. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett Derrick A. How can i deal with missing data in my study? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(5):464–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira Juliana Carvalho, Patino Cecilia Maria. Loss to follow-up and missing data: important issues that can affect your study results. J Bras Pneumol. 2019;45 doi: 10.1590/1806-3713/e20190091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustavson Kristin, von Soest Tilmann, Karevold Evalill, Røysamb Espen. Attrition and generalizability in longitudinal studies: findings from a 15-year population-based study and a Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnard John, Meng Xiao-Li. Applications of multiple imputation in medical studies: from aids to nhanes. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):17–36. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamuyu Gathoni, Bottomley Christian, Mageto James, Lowe Brett, Wilkins Patricia P., Noh John C., et al. Exposure to multiple parasites is associated with the prevalence of active convulsive epilepsy in sub-saharan africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham John W., Olchowski Allison E., Gilreath Tamika D. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little R.J.A., Rubin D.B. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuart Elizabeth A., Azur Melissa, Frangakis Constantine, Leaf Philip. Multiple imputation with large data sets: a case study of the children's mental health initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(9):1133–1139. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen Cattram D., Carlin John B., Lee Katherine J. Practical strategies for handling breakdown of multiple imputation procedures. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2021;18(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12982-021-00095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koech Emily, Stafford Kristen A., Mutysia Immaculate, Katana Abraham, Jumbe Marline, Awuor Patrick, et al. Factors associated with loss to follow-up among patients receiving hiv treatment in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;37(9):642–646. doi: 10.1089/AID.2020.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiwanuka Julius, Waila Jacinta Mukulu, Kahungu Methuselah Muhindo, Kitonsa Jonathan, Kiwanuka Noah. Determinants of loss to follow-up among hiv positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a test and treat setting: a retrospective cohort study in Masaka, Uganda. PloS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunze Kyle N., Burnett Robert A., Lee Elaine K., Rasio Jonathan P., Nho Shane J. Development of machine learning algorithms to predict being lost to follow-up after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehab. 2020;2(5):e591–e598. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madden Kim, Scott Taryn, McKay Paula, Petrisor Brad A., Jeray Kyle J., Tanner Stephanie L., et al. Predicting and preventing loss to follow-up of adult trauma patients in randomized controlled trials: an example from the flow trial. JBJS. 2017;99(13):1086–1092. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teixeira Raquel, Rodrigues Carina, Moreira Carla, Barros Henrique, Camacho Rui. Machine learning methods to predict attrition in a population-based cohort of very preterm infants. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):10587. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13946-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hastie Trevor, Tibshirani Robert, Friedman Jerome H. vol. 2. Springer; 2009. The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction. [Google Scholar]

- 27.JavaTpoint Types of machine learning. 2021. https://www.javatpoint.com/types-of-machine-learning Available. [cited 13 Jul 2023]

- 28.Wang Huimin, Tang Jianxiang, Mengyao Wu, Wang Xiaoyu, Zhang Tao. Application of machine learning missing data imputation techniques in clinical decision making: taking the discharge assessment of patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage as an example. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12911-022-01752-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peiffer-Smadja Nathan, Rawson Timothy Miles, Ahmad Raheelah, Albert Buchard P., Georgiou F.-X. Lescure, Birgand Gabriel, et al. Machine learning for clinical decision support in infectious diseases: a narrative review of current applications. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(5):584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones Gabriel Davis, Kariuki Symon M., Ngugi Anthony K., Mwesige Angelina Kakooza, Masanja Honorati, Owusu-Agyei Seth, et al. Development and validation of a diagnostic aid for convulsive epilepsy in sub-saharan africa: a retrospective case-control study. Lancet Digital Health. 2023;5(4):e185–e193. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00255-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipták Peter, Banovcin Peter, Rosol'anka Róbert, Prokopič Michal, Kocan Ivan, Žiačiková Ivana, et al. A machine learning approach for identification of gastrointestinal predictors for the risk of covid-19 related hospitalization. PeerJ. 2022;10 doi: 10.7717/peerj.13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beguy Donatien, Elung'ata Patricia, Mberu Blessing, Oduor Clement, Wamukoya Marylene, Nganyi Bonface, et al. Health & demographic surveillance system profile: the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system (nuhdss) Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):462–471. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emina Jacques, Beguy Donatien, Zulu Eliya M., Ezeh Alex C., Muindi Kanyiva, Elung'ata Patricia, et al. Monitoring of health and demographic outcomes in poor urban settlements: evidence from the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. J Urban Health. 2011;88:200–218. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9594-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EPInA National institute of health research (nihr) research and innovation for global health epilepsy pathway innovation in africa (epina):(protocol reference: Nihr200134) 2020. https://epina.web.ox.ac.uk/

- 35.Mwanga Daniel, Kadengye Damazo T., Otieno Peter O., Wekesah Frederick M., Kipchirchir Isaac C., Muhua George O., et al. Prevalence of all epilepsies in urban informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya: a two-stage population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2024;12(8):e1323–e1330. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00217-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chawla Nitesh V., Bowyer Kevin W., Hall Lawrence O., Kegelmeyer W. Philip. Smote: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–357. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liaw Andy, Wiener Matthew, et al. Classification and regression by randomforest. R News. 2002;2(3):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuhn Max, Johnson Kjell, et al. vol. 26. Springer; 2013. Applied predictive modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Idris Nashreen Md, Chiam Yin Kia, Varathan Kasturi Dewi, Ahmad Wan Azman Wan, Chee Kok Han, Liew Yih Miin. Feature selection and risk prediction for patients with coronary artery disease using data mining. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2020;58:3123–3140. doi: 10.1007/s11517-020-02268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bishop Christopher M. Vol. 2. Springer; 2006. Pattern recognition and machine learning; pp. 645–678. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng Andrew, Jordan Michael. On discriminative vs. generative classifiers: a comparison of logistic regression and naive bayes. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2001;14 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kecman Vojislav. 2006. Support vector machines for pattern classification. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Tianqi, Guestrin Carlos. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 2016. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van der Laan Mark J., Polley Eric C., Hubbard Alan E. Super learner. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2007;6(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swetha C.V., Shaji Sibi, Meenakshi Sundaram B. International conference on advanced computing and intelligent technologies. Springer; 2023. Feature selection using chi-squared feature-class association model for fake profile detection in online social networks; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Efron Bradley, Tibshirani Robert J. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1994. An introduction to the bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandrekar Jayawant N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(9):1315–1316. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christopher D. Introduction to information retrieval. Syngress Publishing; 2008. Manning. [Google Scholar]

- 49.RCoreTeam . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.https://www.R-project.org/ Available. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernández-Delgado Manuel, Cernadas Eva, Barro Senén, Amorim Dinani. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems? J Mach Learn Res. 2014;15(1):3133–3181. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh Colin G., Ribeiro Jessica D., Franklin Joseph C. Predicting risk of suicide attempts over time through machine learning. Clin Psychol Sci. 2017;5(3):457–469. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mortazavi Bobak J., Downing Nicholas S., Bucholz Emily M., Dharmarajan Kumar, Manhapra Ajay, Li Shu-Xia, et al. Analysis of machine learning techniques for heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(6):629–640. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reed Robert A., Morgan Andrei S., Zeitlin Jennifer, Jarreau Pierre-Henri, Torchin Heloise, Pierrat Veronique, et al. Machine-learning vs. expert-opinion driven logistic regression modelling for predicting 30-day unplanned rehospitalisation in preterm babies: a prospective, population-based study (epipage 2) Front Pediatr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.585868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Christodoulou Evangelia, Ma Jie, Collins Gary S., Steyerberg Ewout W., Verbakel Jan Y., Van Calster Ben. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;110:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wamukoya M., Kadengye D.T., Iddi S., Chikozho C. The Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance of slum dwellers, 2002–2019: value, processes, and challenges. Glob Epidemiol. 2020;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groot Hilde E., Muthuri Stella K. Comparison of domains of self-reported physical activity between kenyan adult urban-slum dwellers and national estimates. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1342350. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1342350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Jinping, Zhang Zhao, Zhou Xia, Pang Xiaomin, Liang Xiulin, Huanjian Huang Lu Yu, et al. Disrupted alertness and related functional connectivity in patients with focal impaired awareness seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moran Nicholas, Poole Kingsley, Bell Gail, Solomon Juliet, Kendall Sally, McCarthy Mark, et al. Nhs services for epilepsy from the patient's perspective: a survey of primary, secondary and tertiary care access throughout the Uk. Seizure. 2000;9(8):559–565. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material