Abstract

Gene-specific CTG/CAG repeat expansion is associated with at least 14 human diseases, including myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1). Most of our understanding of trinucleotide instability is from nonhuman models, which have presented mixed results, supporting replication errors or processes independent of cell division as causes. Nevertheless, the mechanism occurring at the disease loci in patient cells is poorly understood. Using primary fibroblasts derived from a fetus with DM1, we have shown that spontaneous expansion of the diseased (CTG)216 allele occurred in proliferating cells but not in quiescent cells. Expansions were “synchronous,” with mutation frequencies approaching 100%. Furthermore, cells were treated with agents known to alter DNA synthesis but not to directly damage DNA. Inhibiting replication initiation with mimosine had no effect upon instability. Inhibiting both leading- and lagging-strand synthesis with aphidicolin or blocking only lagging strand synthesis with emetine significantly enhanced CTG expansions. It was striking that only the expanded DM1 allele was altered, leaving the normal allele, (CTG)12, and other repeat loci unaffected. Standard and small-pool polymerase chain reaction revealed that inhibitors enhanced the magnitude of short expansions in most cells threefold, whereas 11%–25% of cells experienced gains of 122–170 repeats, to sizes of (CTG)338–(CTG)386. Similar results were observed for an adult DM1 cell line. Our results support a role for the perturbation of replication fork dynamics in DM1 CTG expansions within patient fibroblasts. This is the first report that repeat-length alterations specific to a disease allele can be modulated by exogenously added compounds.

Introduction

The unstable expansion of gene-specific repeat sequences is the causative mutation responsible for at least 33 human diseases. Fourteen diseases, including myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1 [MIM 160900]), Huntington disease (HD), spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1), and spinal bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), are caused by unstable CTG/CAG repeats. Repeat instability in patients and families has recently been reviewed (Cleary and Pearson 2003; Pearson 2003). In addition to mutations occurring in the germ line (Pearson 2003), somatic repeat expansions during early development have been observed in fetuses with DM1 (Jansen et al. 1994; Wohrle et al. 1995; Zatz et al. 1995; Martorell et al. 1997) but not HD or SBMA (Benitez et al. 1995; Jedele et al. 1998). Only low levels of somatic instability have been observed in individuals with HD, SCA1, or SBMA, and, in the former two, length heterogeneity is restricted to the brain and sperm (Cleary and Pearson 2003). In contrast, individuals with DM1 can display high levels of somatic instability, in which intertissue repeat-length differences as large as 1,000 repeats are evident during early fetal development, and differences as great as 3,000 repeats are seen in adult patients (e.g., between either muscle or skin and the peripheral blood leukocytes of a given patient with DM1) (Anvret et al. 1993; Thornton et al. 1994; Wohrle et al. 1995; Zatz et al. 1995; Peterlin et al. 1996; Martorell et al. 1997). Ongoing expansions in somatic cells may contribute to the progressive nature and tissue specificity of disease symptoms (Wong et al. 1995; Martorell et al. 1998).

It is important to understand how repeat expansions occur in their chromosomal context within patient cells for the following reasons: First, the mutation and associated diseases are unique to humans. Second, disease-specific cis elements, including flanking sequences (Neville et al. 1994) and chromatin context, are likely to “drive” the instability (Cleary et al. 2002; Cleary and Pearson 2003; Libby et al. 2003). Third, different diseases display variable levels of repeat instability in different tissues at various developmental windows (Cleary and Pearson 2003). Together, these observations suggest that different mechanisms of instability might occur among the different disease loci. Indeed, nonhuman model systems have suggested that various biological processes can contribute to CTG/CAG instability, including replication slippage, the direction of DNA replication fork progression, Okazaki fragment processing, mismatch repair, gap repair, double-strand break repair, and recombination (reviewed by Lahue and Slater 2003; Pearson 2003; Lenzmeier and Freudenreich 2003). However, in spite of this information, the mutation mechanism occurring at any one disease locus in any patient tissue (somatic or germ cells) is poorly understood (reviewed by Cleary and Pearson 2003; Pearson 2003).

Models using cultured human cells have given mixed results regarding trinucleotide repeat instability. Some failed to show any instability; in others, the mechanism(s) of instability was not clear. No repeat instability was observed in cultured cells from patients with SBMA, HD, or fragile X (FRAXA) (Benitez et al. 1995; Wohrle et al. 1995; Spiegel et al. 1996). In contrast, proliferation of fibroblasts, myoblasts, or virally transformed lymphoblasts in patients with DM1 (Wohrle et al. 1995; Peterlin et al. 1996; Furling et al. 2001; Khajavi et al. 2001) led to detectable expansions of the diseased CTG repeat tract. Transgenic mouse models suggest that there may not be a simple association of cellular proliferation rate with CTG instability, but they have not excluded a requirement for proliferation (Lia et al. 1998; Gomes-Pereira et al. 2001). Although data supporting any particular cellular process were lacking in these cellular studies, it was generally assumed that repeat expansions arose through replication errors, which contrasts with recent observations of instability in nonproliferating tissues in some of the transgenic mouse models (reviewed by Lahue and Slater 2003; Pearson 2003).

In an effort to understand the mechanism of chromosomal repeat instability in somatic human cells, we investigated the requirement of cell proliferation and the effect of various replication inhibitors on CTG instability in primary cell cultures derived from patients with DM1 harboring an expanded (CTG)216 on the chromosome 19 background typical of families with DM1 (Neville et al. 1994), as well as a normal (CTG)12 on the other chromosome 19. We demonstrated that CTG expansions occurred only in proliferating cells from patients with DM1 and that agents that affect DNA synthesis but not replication initiation can specifically modulate the instability of the expanded DM1 CTG repeat.

Methods

Cells and Cell Culture

A primary fibroblast cell line derived from the skin of a 22.5-wk female fetus with DM1 that harbored a maternally inherited repeat tract of (CTG)216, with (CTG)12 on the other allele. Haplotype analysis (not shown) revealed that the expanded allele was on the chromosome 19 background typical of families with DM1 (Neville et al. 1994). The fibroblastic nature of the cells was determined by immunocytochemically staining positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin, desmin, and neuron filament protein (not shown). Another primary fibroblast cell line, derived from the skin of a 76-year-old woman harboring a heterogeneous CTG expansion at the DM1 locus, was used for the experiments shown in figure 6. The use of primary human cell lines reduced the contribution of altered DNA metabolism (replication, repair, recombination, and CpG methylation) specific to virally, chemically, or spontaneously transformed lines (Oppenheim et al. 1981; Habib et al. 1999; Rhim 2000). Unless otherwise noted, cells were cultured in α Minimum Essential Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) at 37°C with 5% CO2, as described elsewhere (Kramer et al. 1996). Proliferating cells were maintained between 20% and 80% confluence and were passaged by splitting 1:4. Cells were arrested and maintained in a nonproliferating state by serum starvation (0.5% serum) or by confluence-induced contact inhibition (with 10% serum), as described by Dell’orco (1974). Clonal lines were derived from single cells isolated from the initial population through the cloning ring technique (Clarke 1997).

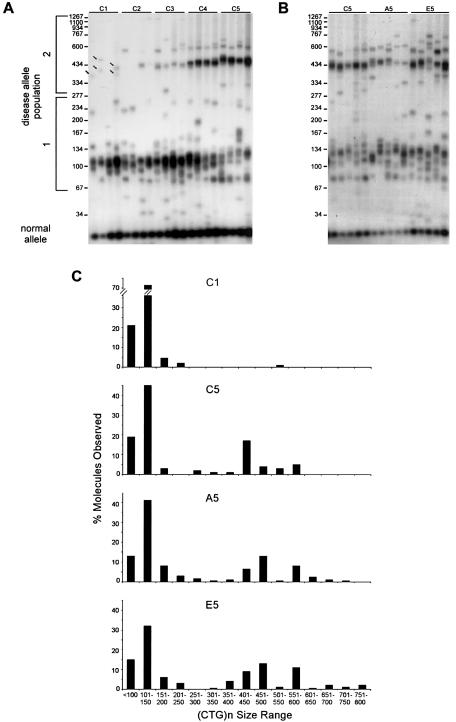

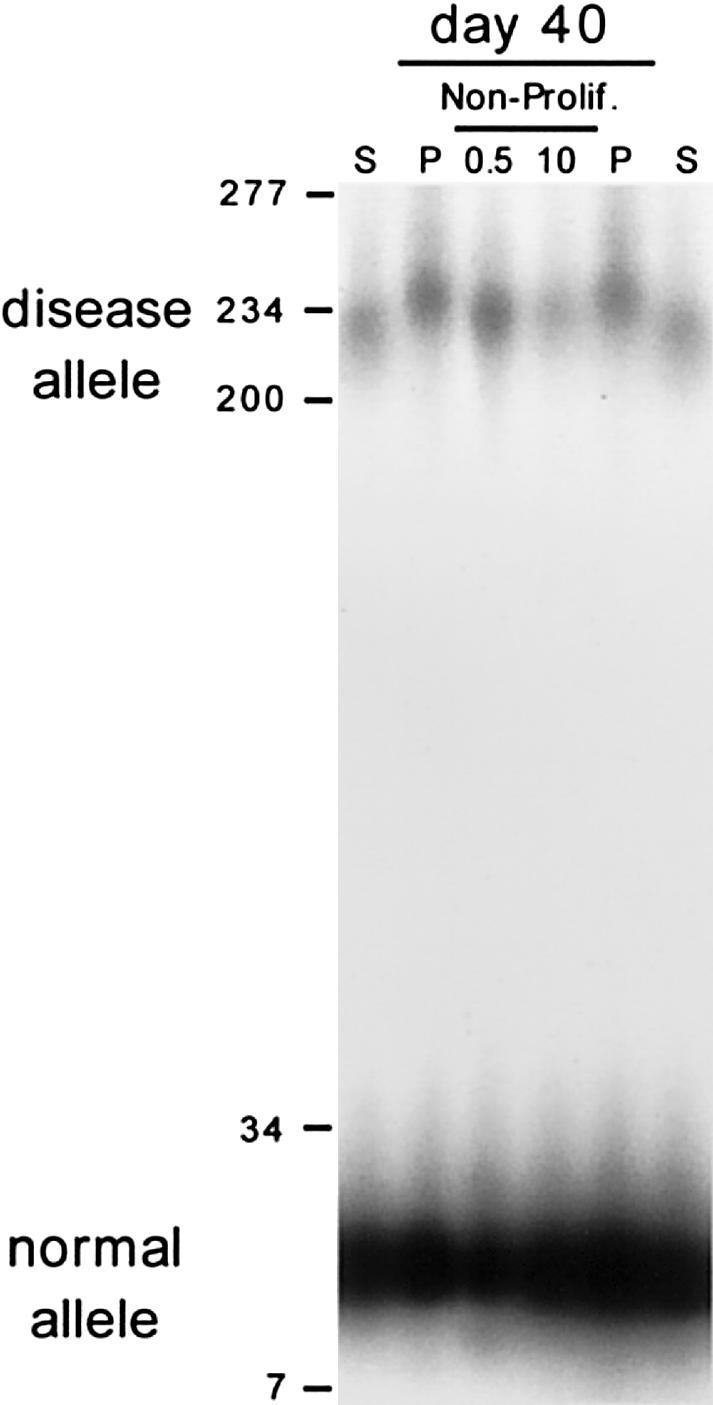

Figure 6.

spPCR analysis of the DM1 CTG tract from an adult cell line. As many as 40 individual spPCRs per sample were performed (see the “Methods” section), and CTG lengths of each product in each reaction were determined on 1.8% agarose gels relative to a DNA size marker (converted to repeat numbers). A, A representative set of spPCR products from the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth rounds of growth of control cells grown in the absence of inhibitors (C1–C5). The major and minor populations of cells harboring shorter and longer CTG expansions are indicated as “population 1” and “population 2,” respectively. Individual faint products in population 2 of C1 are indicated by arrows. B, A representative set of spPCR products from the fifth round of growth in the absence (C5) or presence of aphidicolin (A5) or emetine (E5). Panels A and B are portions of the same gel, permitting the comparison between all lanes and the starting C1 samples. C, Graphical representation of CTG size distributions of individual spPCR products in each sample. The complete sizing and analysis of these and other samples can be found in appendix C (online only).

Replication Inhibitors

Mimosine (Sigma) was stored at −20°C as a 10 mM solution in NaOH/PBS, aphidicolin (Sigma) was stored at −20°C as a 1 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide/PBS, and emetine (Sigma) was stored at −20°C as a 1 mM stock solution in PBS. Mimosine concentration was determined using a range that was previously documented to inhibit initiation of replication origins (Krude 1999). Flow cytometry confirmed that the concentration we used blocked DM1 cells in late G1, prior to replication initiation. Aphidicolin concentration was empirically determined such that the proliferation of the DM1 cells was not arrested but cells would replicate slowly (under perturbed conditions) in the presence of this polymerase inhibitor. Emetine concentration was determined using a range reported to result in preferential inhibition of lagging strand synthesis (Burhans et al. 1991). We confirmed by flow cytometry that both aphidicolin and emetine concentrations that we used resulted in increased levels of DM1 cells in S phase, typical of cells with impaired replication forks. Cells were exposed to replication inhibitors through use of the regimen that is outlined in figure 2 and is described in detail in the figure legend and the “Results” section.

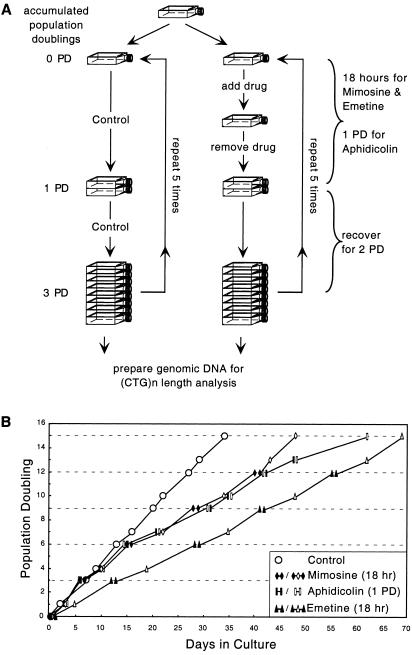

Figure 2.

Drug treatment and growth of DM1 fibroblasts. A, Strategy of drug treatments. Logarithmically growing cells from the same initial plate were split into control (no drug) and drug treatment regimens. To avoid selection for drug-resistant lines, cells were repeatedly exposed to one drug, with drug-free recovery periods between exposures. One “round” of treatment, including exposure and recovery periods, represented a total of three cell PDs. Cells were maintained between 20% and 80% confluence. Approximately 5–6×105 cells/plate at 40% confluence (100-mm plates) were exposed to 1 μM emetine or 200 μM mimosine for 18 h, during which the rate of replication progressively decreased. Low-dose aphidicolin (0.207 μM) exposure spanned a single PD. After exposure, drugs were removed, and cells were washed with PBS and allowed to recover in fresh, drug-free media. Cells were passed through subsequent treatment/recovery regimens for as many as five rounds of exposure to the same drug. At the end of each recovery period, an aliquot of cells was removed, and genomic DNA was extracted for CTG length analyses. For the “no-drug” controls, an equal amount of cells were mock-treated through the same number of cell doublings, and aliquots were taken for DNA analysis after the same number of PD. B, Proliferative status. Drug exposures occurred between blackened-to-blackened shapes, and drug-free recovery periods occurred between blackened shapes interspersed with unblackened shapes.

Repeat-Tract Length Analysis

Genomic DNAs were isolated as described by Kramer et al. (1996). DM1 CTG tract length analysis was performed as follows. Standard PCRs were performed using 100 ng of genomic DNA in the presence of 0.1 μCi α[32P]-dCTP and using previously described primers and amplification conditions (Kramer et al. 1996). Small-pool PCRs (spPCRs) and their analyses were performed essentially as described by Monckton et al. (1995), Wong et al. (1995), and Libby et al. (2003), through use of 1–10 amplifiable genome equivalents that were empirically determined by titrations for each genomic sample. As many as 15–40 spPCRs were performed per sample, each containing 1–5 products of the expanded allele (fig. 4). Repeat-tract lengths of both standard and spPCR products were determined relative to a DNA size marker, after resolution on 1.5% and 1.8% agarose gels, respectively. Sizes were confirmed on denaturing sequencing gels. Determination of the length from any given electrophoretic band cannot be absolute, since size resolution is limited for the longer DNAs: for standard PCR, reported fragment sizes were determined from the peak intensities of individual electrophoretic bands from six independent experiments, and an average is reported.

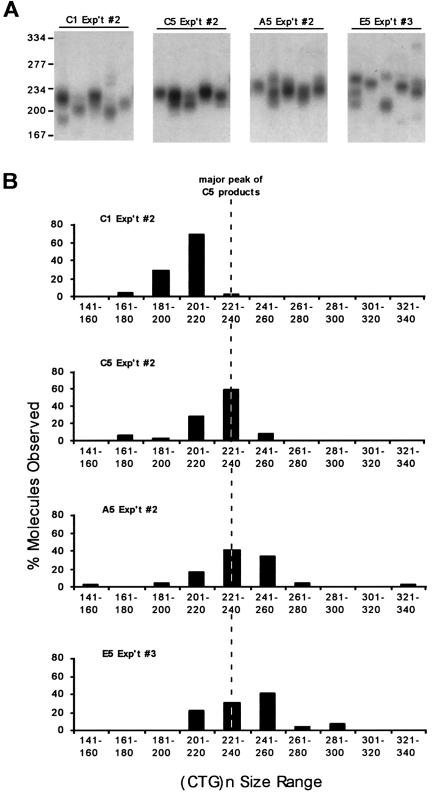

Figure 4.

spPCR analysis of the DM1 CTG tract from control, aphidicolin-treated, and emetine-treated cells. As many as 15–40 individual spPCRs per sample were performed (see the “Methods” section), and CTG lengths of each product in each reaction were determined on 1.8% agarose gels, relative to a DNA size marker (converted to repeat numbers). A, A representative set of spPCR products from the first and fifth rounds of growth of control cells (in the absence of inhibitors) and from the fifth round of growth in the presence of aphidicolin or emetine. The normal DM1 allele remained (CTG)12, and, for the sake of clarity, only the upper portion of the gel with the unstable disease allele is shown. B, Graphical representation of CTG size distributions of individual spPCR products in each sample. To facilitate comparisons, a dashed line indicates the peak CTG size in the fifth round of control cells (C5). The complete sizing and analysis of these and other samples can be found in appendix B (online only).

The trinucleotide and dinucleotide tract lengths of the ERDA1, CTG18.1, FRAXA, and Mfd15 loci were PCR amplified from genomic DNA in the presence of 0.1 μCi α[32P]-dCTP, through use of primers and amplification conditions described elsewhere (Fu et al. 1991; Breschel et al. 1997; Dietmaier et al. 1997; Nakamoto et al. 1997). Products were sized relative to sequencing ladders after resolution on denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels, were dried, and were exposed to x-ray film.

Statistical Analysis

Mann-Whitney tests and SDs were assessed by SPSS 10, and the Fisher’s Exact test was performed through use of the Fisher's Exact Test Web site. All of the compiled data can be found in appendices A, B, and C (online-only).

Results

Instability Occurs in Proliferating but not Quiescent DM1 Cells

To determine the requirement of cell proliferation for repeat instability, we assessed CTG repeat lengths in parallel DM1 cell cultures that had been maintained under proliferative and quiescent states. CTG expansions did not occur in the absence of cell proliferation. After being maintained in a nonproliferative state for 40 d, the CTG tract lengths of both the normal and expanded disease alleles were unchanged relative to the starting culture (compare nonproliferating lanes with starting [S] lanes in fig. 1). In contrast, the proliferating control cells, which had gone through 18 population doublings (PDs) over the 40 d, displayed continuous expansions of the disease allele up to 225 repeats, gaining 9 repeats, whereas the normal allele, (CTG)12, remained unchanged (compare proliferating [P] lanes with starting [S] lanes in fig. 1). Multiple rounds of growth arrest and release did not affect the rate of CTG expansion relative to the total number of PDs (data not shown), and there was no significant variation between CTG length prior to and following growth arrest (Mann-Whitney P>.05). The absence of expansions in the quiescent cells indicated that somatic instability at the DM1 CTG repeat in cultured human fibroblasts is mediated by processes active only during proliferation, possibly during replication.

Figure 1.

DM1 CTG expansion in cultured DM1 fibroblasts requires cell proliferation. Starting cells (S) were split into control, proliferating cells (P), and growth-arrested cells (Non-Prolif.) regimens. Growth arrest was induced by serum starvation (0.5% serum, indicated by “0.5”) or by confluence-induced contact inhibition (10% serum, indicated by “10”). Proliferating cells were split 1:4 nine times over the 40 d. DNAs were isolated, CTG repeats of the DM1 locus were PCR amplified (see the “Methods” section), and tract lengths were determined on 1.5% agarose gels. The size marker has been converted to repeat numbers. The normal (CTG)12 and expanded diseased (CTG)216 DM1 alleles are indicated. To facilitate comparison, the control starting and proliferating samples were loaded flanking the arrested samples.

Growth and Inhibitor-Treatment Strategy

We speculated that insights into the mechanism of repeat instability could be gained if the exposure of cells to replication inhibitors known to perturb different aspects of DNA synthesis were to alter repeat instability. We selected inhibitors for which the mechanism of action is well characterized. Mimosine inhibits replication initiation in human cells (Krude 1999). Aphidicolin inhibits DNA polymerases α, δ, and ε, which act on both the leading and lagging strands of replication forks, as well as at sites of DNA repair (Wright et al. 1994; Michael et al. 2000). Emetine induces imbalanced synthesis at chromosomal replication forks, preferentially blocking synthesis of Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand but not on the leading strand (Burhans et al. 1991). Synthesis of only the leading strand results in replication forks with long stretches of single-stranded lagging strand template. Thus, each drug affected different aspects of DNA metabolism that may participate in CTG instability.

The basic strategy for inducing repeat-length alterations is outlined in figure 2A. Logarithmically growing cells from the same initial plate were split into control (i.e., no drug) and drug treatment regimens. To avoid selection for drug-resistant lines, cells were repeatedly exposed to only one drug, with drug-free recovery periods between treatments. One “round” of treatment included a drug exposure and a recovery period, representing a total of three cell PDs. Cells were exposed to 200 μM mimosine or 1 μM emetine for 18 h, during which the rate of replication progressively decreased until it was completely arrested. Low-dose aphidicolin (0.207 μM) exposure did not completely arrest replication, but it did slow growth, and exposure spanned a single PD. After exposure, drugs were removed and cells were allowed to recover. Cells were passed through subsequent treatment/recovery regimens for as many as five rounds. At the end of each round, an aliquot of cells was removed and genomic DNA extracted for CTG length analysis. For the “no-drug” controls, cells were mock treated and aliquots were taken for DNA analysis after the same number of PDs. Treating cells with drugs multiple times permitted monitoring of the CTG tract for possible length alterations over a time course.

The effect of each drug on cell growth was monitored through multiple rounds of treatment. As noted above, an 18-h exposure to either mimosine or emetine had a considerable affect on cell growth, whereas low-dose aphidicolin exposure only slowed proliferation, extending the PD time (fig. 2B). The inhibitory effects of each drug were reversible, and, for a given drug, the growth rate between individual treatments was consistent. Treated cells continued to be sensitive to the inhibitory action of the drug with subsequent treatments, indicating that we had not selected for drug-resistant populations.

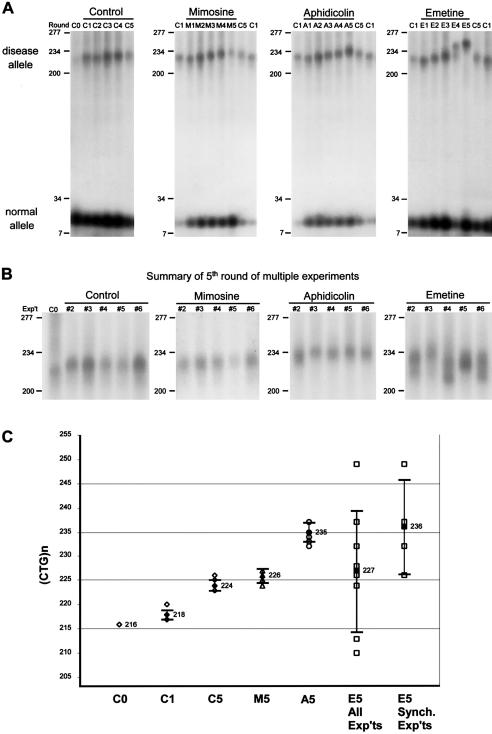

Spontaneous CTG Expansions Can Be Modulated

In the absence of a drug, continued expansions of only the diseased DM1 (CTG)216 repeat occurred over multiple PDs (fig. 3A, control: compare lanes C1–C5). The normal allele remained (CTG)12. Expansions appeared to be “synchronous,” in that the majority—if not all—of the DM1 alleles in the population of cells seemed to expand together, permitting these expansions to be detected using standard PCR techniques (see the “Methods” section). This experiment was repeated as many as six times, and a summary of the fifth rounds of growth in control cells is shown in figure 3B (control). Figure 3C shows a graphical representation of the sizes of the major diseased CTG products in each fifth-round sample. Over the course of five rounds of growth, the diseased allele increased significantly, by 7–10 repeats/15 PDs, to an average length of 224±1.2 repeats (Mann-Whitney P=.002) (see controls in fig. 3A, 3B, and 3C). Similar “synchronous” CTG expansions of comparable magnitudes were reported in DM1 fibroblasts (Wohrle et al. 1995; Peterlin et al. 1996) and myoblasts (Furling et al. 2001) but not in Epstein-Barr virus–transformed lymphoblasts (Khajavi et al. 2001).

Figure 3.

Expansion of chromosomal DM1 CTG repeats in DM1 fibroblasts with or without exposure to replication inhibitors. Control and drug-treated cells were grown through one to five rounds, as outlined in figure 2, and DNAs were isolated for PCR analysis (see the “Methods” section). DM1 CTG repeat lengths were determined on 1.5% agarose gels, relative to a DNA size marker (converted to repeat numbers). A, Results from one set of six independent experiments (experiment #1). PCR products from control cells grown in the absence of drug (starting culture C0, multiple rounds C1–C5). To facilitate length comparisons, flanking each set of PCR products from drug-treated cells are PCR products from control cells (C1 or C5). PCR products are from cells treated with mimosine (rounds M1–M5); aphidicolin (rounds A1–A5); and emetine (rounds E1–E5). B, Summary of the PCR products of fifth round of growth in control, mimosine-, aphidicolin-, and emetine-treated cells from five other independent sets of experiments. The normal DM1 allele remained at (CTG)12 and, for the sake of clarity, only the upper portion of the gel with the unstable disease allele is shown. All panels are portions of the same gel, permitting the comparison between all lanes and the starting C0 sample in the first panel. C, Graphical representation of the sizes of the major diseased CTG products in each fifth round of control and drug-treated samples. For each sample, individual measurements are unblackened symbols, the mean is blackened, and the error bars show plus and minus one sample SD of the data. Two major products were observed in two emetine-treated samples (experiments #4 and #6); hence, there are eight data points for the six repetitions of the experiment. The four emetine-treated samples that displayed synchronous expansions (experiments #1 #2, #3, and #5) are separated out plotted to the right (“Synch.”). The complete sizing of these samples can be found in appendix A (online only).

Inhibition of replication initiation with mimosine yielded CTG expansions similar to those in control cells (fig. 3A, mimosine). As assessed from a total of six independent experiments (fig. 3B, mimosine), five exposures to mimosine did not cause a significant change in the level of CTG instability (Mann-Whitney P=.093), resulting in a mean size of 226±1.5 repeats, similar to the 224±1.2 repeats in control cells (fig. 3C). Thus, repeated inhibition of replication initiation by mimosine had little or no effect on CTG instability. This observation is similar to the lack of an effect by growth arrest in G0 by serum starvation (see fig. 1).

Inhibition of both leading and lagging strands of replication forks by aphidicolin enhanced the magnitude of CTG expansion relative to that in control cells. Aphidicolin induced continued synchronous expansions over multiple treatments, displaying an increased number of CTG repeats gained relative to cells grown in the absence of drug for the same number of PDs (fig. 3A, aphidicolin: compare lanes A1–A5 with C1 and C5). The enhancing effect of aphidicolin upon CTG expansions was highly reproducible over six identical experiments, inducing expansions to a final mean size of 235±2.1 repeats (fig. 3B, aphidicolin). Aphidicolin led to gains of 16–21 repeats/15 PDs, which were significantly greater than the 7–10 repeats/15 PDs gained in control cells, representing a two- to threefold increase (Mann-Whitney P=.002) (fig. 3C). Aphidicolin affected the stability of only the expanded allele, while the normal DM1 allele remained (CTG)12.

The preferential inhibition of lagging-strand synthesis by emetine had two distinct effects on the expanded CTG tract, in that it enhanced CTG expansions and also perturbed the apparent synchronous nature of the expansions. The latter effect manifested as an increased degree of CTG length heterogeneity, evidenced by both the broad, nondistinct nature of the major products and the occurrence of multiple major products (fig. 3B, emetine). In four independent experiments, emetine induced continuous expansions over the multiple treatments relative to control cells grown for the same number of PDs (fig. 3A, emetine: compare lanes E1–E5 with C1 and C5; fig. 3B, emetine: experiments #2, #3, and #5). In these four experiments, emetine significantly enhanced CTG expansions relative to control cells to a broad range of final sizes, with a mean of 236±9.8 repeats (note the large SD) (Mann-Whitney P=.01) (fig. 3C, E5 synchronous experiments). This represents an average gain of 20 repeats/15 PDs, which is a two- to threefold increase over the 7–10 repeats/15 PDs gained by control cells. In two separate experiments, more than one major product was observed (fig. 3B, emetine: experiments #4 and #6). The lower expanded allele in these samples may have arisen by the selection of cells in the starting population with that length, since their sizes were not significantly different from those in the controls (Mann-Whitney P=.071). Both the enhanced expansions and the increased CTG length heterogeneity caused by emetine treatment in each experiment were further assessed by an independent and more sensitive assay (below).

spPCR Analysis Reveals Frequency and Magnitude of CTG Length Alterations

Analysis using the highly sensitive spPCR assay revealed that significantly greater expansions were induced by aphidicolin and emetine; it also indicated the full range of repeat lengths within control and drug-treated samples. spPCR permits the sizing of individual CTG alleles within the population and facilitates the detection of rare large expansion and deletion events, thereby providing an accurate representation of the CTG length distribution within a sample (Monckton et al. 1995; Wong et al. 1995; Libby et al. 2003). Representative spPCR products of DNAs from the control, aphidicolin-treated, and emetine-treated cells are shown in figure 4A, and a graphic representation of the CTG size distributions is shown in figure 4B. In control cells, after five rounds of growth in the absence of drug, the distribution of CTG sizes was significantly increased (Mann-Whitney P<.001), with the mean shifting from 205 repeats (C1) to 222 repeats (C5) and with sizes in the fifth round ranging from 171 to 257 repeats (compare C1 with C5 in fig. 4B). The majority of alleles shifted from a range of 201–220 repeats (C1) to 221–240 repeats (C5), confirming the synchronous nature of the expansions. The CTG size in the aphidicolin-treated cells was significantly greater than in control cells (Mann-Whitney P=.001), having a mean of 236 repeats, with sizes ranging from 159 to 338 repeats (compare A5 with C5 in fig. 4B). In four of the emetine-treated samples, the mean size of the CTG repeat was significantly greater relative to that in the control cells (Mann-Whitney P ranging from <.001 to .002) and ranged from 107 to 386 repeats (compare E5 with C5 in fig. 4B). In the two emetine-treated samples that displayed more than one major expanded allele by standard PCR (fig. 3B, emetine: experiments #4 and #6), the mean CTG size by spPCR was 237 repeats (not shown) and 228 repeats (not shown). Although greater than the mean size in the control (222 repeats), these were not significantly different (Mann-Whitney P=.076 and P=.32). In all six emetine-treated samples, the range of CTG tract lengths (107–386 repeats) was considerably greater than that in control cells (171–257 repeats). Importantly, in the emetine-treated samples, a significant portion of alleles (25%) contained more repeats (as many as 129 more) than the largest tract, (CTG)257, observed in the control cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.001), representing gains of as many as 170 repeats onto the initial (CTG)216. In contrast, only 1% of emetine-treated alleles contained fewer repeats than the shortest tract, (CTG)171, in the control, and these were not significant (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P=1). Similarly, for aphidicolin-treated samples, 11% of the alleles were significantly larger (as many as 81 repeats) than the largest tract, (CTG)257, in the controls (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P=.038), which represents 122 repeats more than the initial (CTG)216, and only a nonsignificant 2% contained fewer repeats than the shortest tract, (CTG)171, in the control samples (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P=1). Thus, aphidicolin and emetine enhanced both the CTG expansion size and CTG tract length heterogeneity.

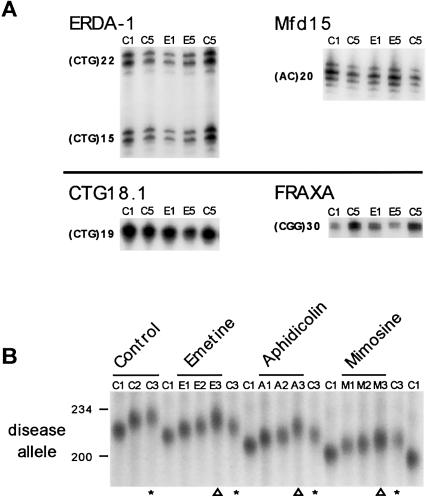

Specificity of Inhibitor-Induced Instability

The preferential susceptibility of the expanded—but not the normal—DM1 allele to mutations induced by replication fork inhibitors was further investigated by analyzing other repeat loci (ERDA1, CTG18.1, FRAXA, and Mfd15) in DNAs derived from mimosine-treated, aphidicolin-treated, and emetine-treated DM1 cells, as well as control cells. Although these repeat tracts can display length instabilities in some individuals and can be hypersensitive to changes in repair-deficient cells (Fu et al. 1991; Breschel et al. 1997; Dietmaier et al. 1997; Nakamoto et al. 1997), none of the short tracts varied in length after multiple exposures to emetine (fig. 5A) or mimosine or aphidicolin (data not shown). These results illustrate that aphidicolin and emetine preferentially affected the stability of the expanded disease DM1 CTG tract in the fibroblasts of patients with DM1.

Figure 5.

Preferential and actively enhanced expansions of the diseased DM1 CTG repeat. A, Repeat-tract lengths of the ERDA1, CTG18.1, FRAXA, and Mfd15 loci were determined by PCR (see the “Methods” section) in control and drug-treated DM1 cells grown through one to five rounds, as outlined in figure 2. DNAs were isolated for PCR analysis (see the “Methods” section), and tract lengths were determined on denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels, relative to sequencing ladders. Only the first and fifth rounds of the control and emetine-treated cells are shown. The same analysis was performed on DNA from aphidicolin-treated and mimosine-treated cells; length variation was not observed at any of these repeats (data not shown). B, Expansion of DM1 CTG repeats in a single cell clonal line of the DM1 fibroblasts. Control and drug-treated cells were grown through multiple rounds, and DNAs were isolated as outlined in figure 2A. DM1 CTG repeats were PCR amplified, and tract lengths were determined by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels alongside a DNA size marker (converted to repeat numbers). To facilitate length comparisons, flanking each set of PCR products from drug-treated cells are PCR products from control cells (C1 or C3). Although this gel was run at a slant, CTG length differences are observable by comparing flanking C3 with E3 or A3 (compare lanes indicated by asterisks with those indicated by triangles). As indicated, shown are PCR products from control cells grown in the absence of drug (rounds C1–C3), cells treated with emetine (rounds E1–E3), aphidicolin (rounds A1–A3), or mimosine (rounds M1–M3).

Active Expansions Occur in a Single Cell Clone

To determine whether the progressively larger alleles observed were due to active repeat expansion or were solely the result of selective growth of a few cells containing longer repeats, we isolated a clonal line of the DM1 cells and subjected it to the drug treatment regimen. Since the clonal line was derived from a single cell, it permitted any alleles with repeat lengths different from those of the progenitor cell to be scored as mutants. Similar to the mixed population, both spontaneous and drug-enhanced CTG expansions were observed in the clonal lines. The pattern of CTG expansion appeared synchronous. Repeated treatments with emetine or aphidicolin resulted in progressively larger DM1 CTG tracts (compare lanes C1–C3 with E1–E3 and A1–A3 in fig. 5B). Mimosine failed to alter the magnitudes of expansion (compare lane M3 with C3). The extensive growth required for isolation of the clonal lines from single cells reduced the growth potential of the cells, which may be related to the reduced culture life previously reported for DM1 cells (Furling et al. 2001; Khajavi et al. 2001). Multiple experiments from different clones consistently showed spontaneous expansions that were enhanced by emetine and aphidicolin treatment but not by mimosine treatment. Other experiments revealed that, after treatment, the enhanced expansion rate did not persist without subsequent drug treatments, revealing that we had not selected for a subpopulation with an inherently increased expansion rate (not shown). Thus, active expansions are occurring in the fibroblasts. In addition to active expansions, selective growth advantage of daughter cells with de novo expansion may also be occurring in our cell cultures. Together, the results indicate that active expansions of the DM1 CTG repeat are spontaneously occurring and that emetine or aphidicolin treatment enhanced the magnitude of the expansions.

Spontaneous CTG Expansions Can Be Modulated in an Adult DM1 Cell Line

An independent cell line derived from the skin of an adult patient with DM1 was subjected to the same growth/treatment regimen, to determine the effect of replication inhibitors, since the pattern of CTG expansions in cultured DM1 cells can vary. The synchronous appearance of the CTG expansions in fetal cell lines observed by us and by others (Wohrle et al. 1995; Furling et al. 2001) may be due to the low levels of intratissue CTG length heterogeneity acquired at this early stage (instability is first detectable around week 16 of fetal development) (Wohrle et al. 1995; Martorell et al. 1997). High levels of intratissue CTG length heterogeneity in adult patients with DM1 are age-dependent (Wong et al. 1995; Martorell et al. 1998). Although cultured cell lines derived from adult patients with DM1 display active CTG expansions, the pattern was not synchronous (Ashizawa et al. 1996; Khajavi et al. 2001). We extended our experiments to an adult (76 year old) fibroblast cell line. Unlike the fetal line, the adult line displayed considerable CTG length heterogeneity, which is consistent with the age dependency of heterogeneity (Wong et al. 1995). The majority of the cells had CTG tracts ranging from 63 to 241 repeats (fig. 6A: see disease allele population 1), and a minor population had larger repeat sizes (fig. 6A: see disease allele population 2 and bands on C1 lanes indicated by arrows). The degree and magnitude of CTG length heterogeneity was confirmed by isolation of individual clones, which contained only one expanded allele from either size population. Unfortunately, these clonal lines did not have sufficient growth potential for further experimentation (data not shown). After growth in drug-free conditions, two major populations of CTG lengths became apparent: those with lengths ranging from 56 to 260 repeats and those ranging from 295 to 570 repeats (compare C1–C5 in fig. 6A). The increase in cells with longer repeats indicates a “mitotic drive,” or selective growth advantage of cells with longer tract lengths, a phenomenon previously described for cultured lymphoblastoid cells from adults with DM1 and transgenic mouse cells (Gomes-Pereira et al. 2001; Khajavi et al. 2001). Active spontaneous CTG expansions were also occurring, since the CTG distribution in C5 cells was significantly larger than that in C1 cells (Mann-Whitney P<.001) (compare C1 with C5 in fig. 6C). Importantly, in the C5 samples, a significant portion of alleles (8%) contained more repeats (as many as 25 more) than the largest tract, (CTG)545, observed in the C1 cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P=.001). Multiple treatments with aphidicolin or emetine significantly enhanced the magnitude of CTG expansions (compare C5 with A5 and C5 with E5 in fig. 6B; see also fig. 6C). The CTG size in the aphidicolin-treated cells was significantly greater than in control cells (Mann-Whitney P=.007) and contained a significant portion of alleles (10%) with more repeats (as many as 152 more) than the largest tract, (CTG)570, observed in the C5 cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.001) (compare A5 with C5 in fig. 6C). Similarly, the CTG size in the emetine-treated cells was significantly greater than in control cells (Mann-Whitney P<.001) and contained a significant portion of alleles (13%) with more repeats (as many as 207 more) than the largest (CTG)570 tract observed in the C5 cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.001) (compare E5 with C5 in fig. 6C). Under all conditions, the normal CTG allele did not change (fig. 6A and 6B). These results provide independent evidence that spontaneous CTG expansions are occurring at the DM1 disease locus and that the magnitude of these expansions is enhanced by treatment with either aphidicolin or emetine.

Discussion

Of the 14 diseases associated with CTG/CAG expansions, the contribution of somatic instability is most predominant for DM1, in which large intertissue repeat-length differences are evident during early fetal development and in adult patients (Wohrle et al. 1995; Zatz et al. 1995; Martorell et al. 1997). Considerably greater expansions have been observed in muscle (Anvret et al. 1993; Thornton et al. 1994), fibroblasts, and skin (Peterlin et al. 1996) than in blood from the same individual with DM1. In blood, CTG expansions can continue throughout the life of affected individuals (Wong et al. 1995; Martorell et al. 1998), although the same may not be true for muscle (Anvret et al. 1993; Thornton et al. 1994). It has been suggested that, in muscle and fibroblasts, expansions begin during early development, progress during cell division, and cease in childhood at a stage coincident with cell quiescence and terminal differentiation (Zatz et al. 1995). Larger CTG expansions in tumors of patients with DM1 relative to their nonneoplastic tissue suggest that expansions may also occur during acquired cell proliferation (Osanai et al. 2000; Kinoshita et al. 2002). We have experimentally demonstrated that somatic CTG instability at the DM1 locus is mediated by processes that are functional in proliferating cells and that cell quiescence is associated with the arrest of expansions.

Active expansions of the DM1 CTG repeat occurred spontaneously in cultured DM1 fibroblasts. The apparent “synchronous” pattern has been reported for various cultured DM1 fetal cells from different tissues (Wohrle et al. 1995; Furling et al. 2001). spPCR revealed that the changes were not strictly synchronous but that the range of expansion sizes was limited. The pattern of synchronous expansion is unusual and, for no obvious reason, it seems that the magnitude of repeats gained by most cells was similar. This may reflect the amount of excess or slipped repeats that are permitted within the replication fork machinery. Although we have demonstrated that active expansions are occurring, selective growth advantage of cells harboring larger repeats may also be operating, particularly after considerable length heterogeneity has been established, as may be evident in older patients. The mode of CTG expansion observed herein may resemble instability occurring in somatic tissues of fetuses and patients with DM1.

Aphidicolin and emetine enhanced the magnitude of CTG expansions in DM1 fibroblasts. Both compounds act on replication forks but do not damage DNA, supporting a mechanism of somatic expansion involving replication forks. Aphidicolin, but not emetine, can induce locus-specific “common” but not “rare” fragile sites (Sutherland and Richards 1999). Rare fragile sites, such as FRAXA, are induced by folate perturbations but not by aphidicolin. It is unlikely that the enhanced DM1 CTG expansion is related to fragile-site expression, since none of the sequenced common fragile sites contain repeated sequences. Furthermore, numerous stressors, including aphidicolin, have failed to induce fragile-site expression at the DM1 locus in normal or patient cells (Jalal et al. 1993; Wenger et al. 1996), and the DM1 region is not predisposed to breakage or recombination, which are common to many fragile sites. Thus, aphidicolin- and emetine-enhanced CTG expansions are likely mediated by mutagenic events at the replication fork.

We demonstrated that CTG expansions occurred only in proliferating cells from patients with DM1 and that agents that affect DNA synthesis—but not replication initiation—can specifically modulate the instability of the expanded DM1 CTG repeat. Our results may reflect repeat expansions occurring either by repair processes that are replication-independent but active only during cell proliferation or by the formation and error-prone processing of replication fork errors. Several pieces of evidence favor the latter possibility. First, the fact that many repair processes, including mismatch repair, are active in both proliferating and quiescent cells argues against a proliferation-specific repair mechanism (Dell’orco and Whittle 1978; reviewed by Nouspikel and Hanawalt 2002). Second, the increased expansions induced by aphidicolin and emetine likely arose through their perturbation of replication forks rather than by repair processes, since protein-synthesis inhibitors such as emetine preferentially affect replication (Gautschi et al. 1973; Stimac et al. 1977), and aphidicolin does not affect all forms of repair (Wright et al. 1994; Wood and Shivji 1997). Third, the lack of an effect by mimosine, which can also affect repair, supports replication-mediated expansions. Fourth, since neither aphidicolin nor emetine is known to directly damage DNA, it is unlikely that their effect on CTG instability arose from damage-induced, error-prone repair. Thus, our data support a mechanism of somatic DM1 CTG expansions occurring by replication fork errors.

We propose that aphidicolin or emetine induced imbalanced DNA synthesis between the leading and lagging strands and thereby facilitated CTG expansions. The emetine-enhanced CTG expansions were likely mediated by the striking effects of this compound upon replication fork dynamics, permitting considerable stretches of leading-strand synthesis in the complete absence of lagging-strand synthesis (Burhans et al. 1991). Different polymerases might participate in the polymerization and/or exonucleolytic steps of leading- and lagging-strand synthesis (e.g., polymerases α, δ, and ε) (Karthikeyan et al. 2000; Sogo et al. 2002; Chilkova et al. 2003). The differential inhibition of these polymerases by a low dose of aphidicolin (Wright et al. 1994) might induce uncoupling of leading- from lagging-strand synthesis, thereby facilitating expansions. Both aphidicolin and emetine induce extensive regions of single-stranded template DNA at replication forks (Burhans et al. 1991; Michael et al. 2000). Biophysical destabilization of replication forks may occur preferentially at expanded repeat tracts and could facilitate genetic instability, possibly involving slipped-strand DNAs (Pearson et al. 2002). Perturbation of replication fork dynamics by either emetine or aphidicolin enhanced by threefold the magnitude of short expansions in most cells, whereas 11%–25% of cells experienced gains of 122–170 repeats (from [CTG]216 to [CTG]338–[CTG]386). Consistent with a replication-based mechanism are the observations that treatment of mammalian cells with various replication inhibitors induced overreplication and gene amplification (Hoy et al. 1987), as well as increased replication fork-associated recombination between tandem repeats (Saintigny et al. 2001). Recent evidence from model systems indicates the importance of replication fork dynamics in replication-mediated CTG instability (Samadashwily et al. 1997; Cleary et al. 2002; reviewed by Lahue and Slater 2003; Lenzmeier and Freudenreich 2003). The results presented here show that CTG expansions at a disease chromosomal locus (DM1) in patient cells occur through replication errors. Our results support replication-mediated CTG expansions at the DM1 chromosomal locus.

Regardless of the precise mechanism, we have demonstrated that exposure to exogenously added compounds can specifically alter the genetic instability of the expanded CTG tract at the DM1 chromosomal locus in patient cells, leaving the normal DM1 allele and other sequences unaffected. The longer expanded CTG tract at the diseased allele may be hypermutable when replication is impaired by inhibitors, a sensitivity that may be mediated by an increased propensity to form slipped-strand DNA structures, which are known to be sensitive to repeat length (Pearson et al. 2002). This interpretation is consistent with the enhanced expansions being caused by perturbation of replication fork progression but not by the inhibition of replication initiation or by the ablation of instability with the arrest of proliferation. We suggest that the mode through which the DM1 chromosomal CTG repeat is replicated is a critical determinant of repeat instability, and compounds that alter this replication may critically affect the fidelity by which the CTG repeats are copied. The identification of exogenously added compounds that specifically alter repeat instability at a disease locus provides insight for research aimed at developing pharmacological agents that would intervene with the mutation process, to slow pathogenesis in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank our lab members for their discussions and John Heddle for critically reviewing the manuscript. We also thank Andrew Paterson for statistical analysis and Darren G. Monckton for expert advice on spPCR. This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association USA (to C.E.P.). C.E.P. is a CIHR Scholar and a Canadian Genetic Disease Network Scholar. Z.Y. is a CIHR/Fragile X Research Foundation of Canada postdoctoral fellow.

Appendix A: DM1 CTG Length Determined by Standard PCR

Six independent repetitions of each experiment, with or without exposure to replication inhibitors, were performed as outlined in figure 2. The DM1 cells had initial lengths of (CTG)216 and (CTG)12 at the disease and normal alleles, respectively. DM1 CTG repeat lengths were determined on 1.5% agarose gels, relative to a DNA size marker (for examples, see fig. 3A and 3B). Individual numbered experiments are indicated in table A1. The normal allele remained (CTG)12. Shown in table A1 are the CTG tract lengths of the major PCR products of the disease allele in the first and fifth rounds of growth, as well as their means and SDs. The Mann-Whitney P values are given in table A2. The data in table A1 were used to plot the graph shown in figure 3C.

Table A1.

Standard PCR Data[Note]

| Sample | No. ofRepeats |

| Control Round 1 (C1): | |

| Experiment #1 | 218 |

| Experiment #2 | 217 |

| Experiment #3 | 218 |

| Experiment #4 | 220 |

| Experiment #5 | 218 |

| Experiment #6 | 218 |

| Mean±SD | 218±1.0 |

| Control Round 5 (C5): | |

| Experiment #1 | 224 |

| Experiment #2 | 225 |

| Experiment #3 | 226 |

| Experiment #4 | 223 |

| Experiment #5 | 223 |

| Experiment #6 | 224 |

| Mean±SD | 224±1.2 |

| Mimosine Round 5 (M5): | |

| Experiment #1 | 227 |

| Experiment #2 | 224 |

| Experiment #3 | 224 |

| Experiment #4 | 225 |

| Experiment #5 | 227 |

| Experiment #6 | 227 |

| Mean±SD | 226±1.5 |

| Aphidicolin round 5 (A5): | |

| Experiment #1 | 233 |

| Experiment #2 | 232 |

| Experiment #3 | 237 |

| Experiment #4 | 234 |

| Experiment #5 | 237 |

| Experiment #6 | 234 |

| Mean±SD | 235±2.1 |

| Emetine round 5 (E5): | |

| All Experiments: | |

| Experiment #1 | 249 |

| Experiment #2 | 232 |

| Experiment #3 | 237 |

| Experiment #4a | 224, 210 |

| Experiment #5 | 226 |

| Experiment #6a | 228, 213 |

| Mean±SD | 227±12.6 |

| Synchronous experiments: | |

| Experiment #1 | 249 |

| Experiment #2 | 232 |

| Experiment #3 | 237 |

| Experiment #5 | 226 |

| Mean±SD | 236±9.8 |

Table A2.

Statistical Analysis

| Comparison of Samples | Mann-Whitney P Value |

| C1 versus C5 (all experiments) | .002 |

| C5 versus M5 (all experiments) | .093 |

| C5 versus A5 (all experiments) | .002 |

| C5 versus E5 (all experiments) | .282 |

| C5 versus E5 (synchronous experiments) | .01 |

Appendix B: DM1 CTG Length Determined by spPCR

Six independent repetitions of each experiment, with or without exposure to aphidicolin or emetine, were performed as outlined in figure 2. The DM1 cells had initial lengths of (CTG)216 and (CTG)12, at the disease and normal alleles, respectively. As many as 15–40 independent spPCRs were performed on each of the first and fifth rounds of both control and aphidicolin and emetine-treated samples for each experiment (see the “Methods” section). Each spPCR contained one to five products of the expanded allele (fig. 4A). CTG lengths of each product in each reaction were determined on 1.8% agarose gels, relative to a DNA size marker. Results of individual experiments are indicated in tables B1 and B2. The normal allele remained (CTG)12. Table B1 shows the CTG tract lengths of individual spPCR products; listed at the bottom of the table are the mean sizes. The statistics (Mann-Whitney) derived by comparison of individual spPCR products are shown in table B2. The proportion of all the emetine-treated alleles that were greater than the largest control (C5) allele, (CTG)257, is shown to be 25% and is statistically significant (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.001). The longest emetine-treated sample contained 386 repeats, which was 170 repeats greater than the initial (CTG)216. Similarly, the proportion of all the aphidicolin-treated alleles that were greater than the largest control (C5) allele, (CTG)257, is shown to be 11% and is statistically significant (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.038). The longest aphidicolin-treated sample contained 338 repeats, which was 122 repeats greater than the initial (CTG)216. The normal DM1 allele remained (CTG)12. These data were used to plot the CTG length distributions illustrated in figure 4B.

Table B1.

Small Pool PCR Data[Note]

|

CTG Tract Length |

|||||||||

| C1 Experiment #2 | C5 Experiment #2 | A5 Experiment #2 | E5 Experiment #1 | E5 Experiment #2 | E5 Experiment #3 | E5 Experiment #4 | E5 Experiment #5 | E5 Experiment #6 | |

| 174 | 171 | 159 | 221 | 199 | 212 | 198 | 107 | 199 | |

| 176 | 173 | 193 | 223 | 207 | 212 | 202 | 111 | 217 | |

| 182 | 195 | 196 | 240 | 207 | 217 | 203 | 221 | 217 | |

| 186 | 204 | 202 | 240 | 207 | 217 | 207 | 221 | 217 | |

| 190 | 204 | 208 | 246 | 207 | 217 | 211 | 226 | 219 | |

| 192 | 204 | 208 | 246 | 212 | 217 | 216 | 231 | 221 | |

| 194 | 208 | 214 | 253 | 216 | 217 | 221 | 231 | 221 | |

| 196 | 212 | 217 | 259 | 216 | 217 | 226 | 236 | 221 | |

| 198 | 214 | 217 | 259 | 216 | 222 | 231 | 241 | 223 | |

| 198 | 214 | 217 | 259 | 216 | 227 | 231 | 241 | 223 | |

| 198 | 214 | 220 | 263 | 218 | 227 | 236 | 241 | 225 | |

| 198 | 217 | 220 | 263 | 221 | 230 | 241 | 246 | 225 | |

| 198 | 217 | 223 | 263 | 221 | 230 | 241 | 251 | 228 | |

| 200 | 219 | 223 | 263 | 221 | 232 | 244 | 251 | 234 | |

| 202 | 221 | 226 | 266 | 221 | 232 | 251 | 251 | 236 | |

| 202 | 221 | 226 | 266 | 223 | 232 | 253 | 266 | 236 | |

| 202 | 225 | 226 | 266 | 225 | 232 | 256 | 272 | 236 | |

| 202 | 225 | 229 | 266 | 225 | 232 | 260 | 272 | 238 | |

| 202 | 225 | 232 | 266 | 225 | 232 | 277 | 282 | 238 | |

| 202 | 225 | 232 | 266 | 225 | 243 | 323 | 240 | ||

| 204 | 225 | 232 | 266 | 225 | 245 | 242 | |||

| 206 | 225 | 232 | 266 | 226 | 248 | 259 | |||

| 206 | 225 | 232 | 266 | 226 | 248 | ||||

| 206 | 225 | 232 | 266 | 226 | 248 | ||||

| 206 | 228 | 232 | 266 | 226 | 248 | ||||

| 206 | 228 | 236 | 266 | 226 | 248 | ||||

| 209 | 230 | 236 | 266 | 229 | 251 | ||||

| 211 | 230 | 236 | 266 | 231 | 254 | ||||

| 213 | 230 | 236 | 266 | 231 | 254 | ||||

| 213 | 232 | 236 | 270 | 231 | 254 | ||||

| 216 | 234 | 236 | 280 | 231 | 256 | ||||

| 216 | 234 | 239 | 234 | 259 | |||||

| 216 | 234 | 239 | 237 | 259 | |||||

| 216 | 237 | 239 | 240 | 259 | |||||

| 216 | 239 | 242 | 240 | 265 | |||||

| 216 | 239 | 242 | 242 | 292 | |||||

| 216 | 239 | 242 | 242 | 295 | |||||

| 218 | 243 | 242 | 242 | ||||||

| 218 | 243 | 242 | 242 | ||||||

| 218 | 257 | 245 | 243 | ||||||

| 220 | 245 | 245 | |||||||

| 220 | 245 | 248 | |||||||

| 220 | 252 | 248 | |||||||

| 220 | 252 | 248 | |||||||

| 225 | 252 | 251 | |||||||

| 252 | 251 | ||||||||

| 256 | 253 | ||||||||

| 256 | 253 | ||||||||

| 256 | 254 | ||||||||

| 259 | 254 | ||||||||

| 259 | 254 | ||||||||

| 259 | 254 | ||||||||

| 266 | 254 | ||||||||

| 273 | 254 | ||||||||

| 338 | 254 | ||||||||

| 258 | |||||||||

| 260 | |||||||||

| 262 | |||||||||

| 262 | |||||||||

| 262 | |||||||||

| 262 | |||||||||

| 266 | |||||||||

| 267 | |||||||||

| 272 | |||||||||

| 304 | |||||||||

| 386 | |||||||||

| Mean | 205 | 222 | 236 | 259 | 240 | 240 | 237 | 232 | 228 |

Table B2.

Statistical Analysis

| Comparison of Samples | Mann-Whitney P Value |

| C1 experiment #2 versus C5 experiment #2 | <.001 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus A5 experiment #2 | .001 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 experiment #1 | <.001 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 experiment #2 | <.001 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 experiment #3 | <.001 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 experiment #4 | .076 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 experiment #5 | .002 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 experiment #6 | .323 |

| Fisher's Exact Test Two-Tailed P Value |

|

| C5 experiment #2 versus A5 experiment #2a | .038 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus A5 experiment #2b | 1 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 (all experiments)c | <.001 |

| C5 experiment #2 versus E5 (all experiments)d | 1 |

Eleven percent of alleles were larger than the largest control allele, (CTG)257.

Two percent of alleles were smaller than the smallest control allele, (CTG)171.

Twenty-five percent of alleles were larger than the largest control allele, (CTG)257.

One percent of alleles were smaller than the smallest control allele, (CTG)171.

Appendix C: DM1 CTG Length Determined by spPCR on an Adult Cell Line

An independent cell line derived from the skin of an adult patient with DM1 was exposed to aphidicolin or emetine as outlined in figure 2, and spPCR was performed. Between 32 and 40 independent spPCRs were performed on each of the first and fifth rounds of control samples and on the fifth round of aphidicolin and emetine-treated samples. Each spPCR contained 2–10 products of the disease allele (fig. 6B). CTG lengths of each product in each reaction were determined on 1.8% agarose gels, relative to a DNA size marker. Table C1 shows the CTG tract lengths of individual spPCR products; those products with peak area <3% are underlined in the table and were not used to plot the graph in figure 6C or in statistical analysis (table C2). In the C5 samples, a significant portion of alleles (8%) contained more repeats (as many as 25 more) than the largest tract, (CTG)545, observed in the C1 cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P=.001). The CTG size in the aphidicolin-treated cells contained a significant portion of alleles (10%) with more repeats (as many as 152 more) than the largest tract, (CTG)570, observed in the C5 cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.001). Similarly, the CTG size in the emetine-treated cells contained a significant portion of alleles (13%) with more repeats (as many as 207 more) than the largest tract, (CTG)570, observed in the C5 cells (Fisher's Exact test, two-tailed P<.001). Under all conditions, the normal CTG allele did not change.

Table C1.

spPCR Data on Adult Cell Line[Note]

| CTG Tract Length | |||

| C1 | C5 | A5 | E5 |

| 63 | 56 | 67 |

69 |

| 66 | 56 | 73 | 75 |

| 66 | 62 | 74 | 77 |

| 66 | 62 | 79 | 77 |

| 77 | 62 | 79 | 78 |

| 79 | 65 | 81 | 78 |

| 79 | 68 | 81 | 79 |

| 79 | 68 | 81 |

79 |

| 79 | 68 | 84 | 79 |

| 83 | 68 | 84 | 80 |

| 86 | 68 | 84 | 81 |

| 86 | 68 | 86 | 81 |

| 86 |

68 | 87 | 81 |

| 86 |

68 | 87 | 81 |

| 88 | 68 |

87 | 82 |

| 88 | 71 | 87 | 84 |

| 89 | 73 | 87 | 84 |

| 89 | 74 | 87 | 84 |

| 89 |

75 | 87 |

84 |

| 92 | 75 | 88 | 84 |

| 92 | 75 | 88 | 86 |

| 95 | 75 | 88 | 88 |

| 95 | 75 | 88 |

88 |

| 95 | 77 | 88 |

88 |

| 97 | 79 | 89 | 89 |

| 97 | 79 | 89 | 97 |

| 100 | 79 | 90 | 97 |

| 101 | 79 | 91 |

100 |

| 104 | 81 | 96 |

100 |

| 104 | 81 |

97 | 103 |

| 105 | 83 | 98 |

103 |

| 106 | 83 | 100 | 106 |

| 106 | 83 | 100 | 106 |

| 106 | 88 | 100 | 109 |

| 106 | 90 | 102 | 109 |

| 106 | 96 | 102 | 112 |

| 107 | 107 | 102 | 112 |

| 107 | 107 | 102 | 112 |

| 107 | 107 | 102 | 112 |

| 109 | 107 | 103 | 113 |

| 109 | 109 | 104 | 113 |

| 109 | 109 | 104 | 114 |

| 109 | 109 | 105 | 114 |

| 110 | 110 | 107 | 117 |

| 110 | 110 | 108 | 117 |

| 110 | 110 | 108 | 120 |

| 112 | 111 | 109 | 122 |

| 112 | 112 | 111 | 122 |

| 112 | 112 | 111 | 123 |

| 115 | 112 | 111 | 123 |

| 115 | 112 | 111 | 124 |

| 115 | 112 | 111 | 124 |

| 115 | 113 | 111 |

126 |

| 118 | 113 | 113 | 126 |

| 118 | 113 | 114 | 126 |

| 118 | 114 | 114 | 126 |

| 118 | 116 | 115 | 127 |

| 118 | 116 | 117 | 129 |

| 120 | 116 | 117 | 129 |

| 120 | 116 | 117 | 129 |

| 122 | 117 | 117 | 129 |

| 123 | 117 | 118 | 129 |

| 123 | 118 | 120 | 129 |

| 123 | 119 | 120 | 129 |

| 123 | 120 | 121 | 130 |

| 123 | 122 | 121 | 130 |

| 123 | 122 | 123 | 130 |

| 123 | 122 | 123 | 130 |

| 124 | 123 | 124 | 132 |

| 125 | 125 | 124 | 132 |

| 125 | 125 | 124 | 132 |

| 126 | 125 | 124 | 135 |

| 126 | 125 | 126 | 135 |

| 126 | 125 | 127 | 135 |

| 126 | 125 | 127 | 136 |

| 127 | 125 | 127 | 138 |

| 127 | 125 | 129 | 139 |

| 127 | 125 | 129 | 141 |

| 128 | 127 | 129 | 141 |

| 129 | 127 | 129 | 141 |

| 129 | 127 | 130 | 141 |

| 131 | 127 | 130 | 143 |

| 133 | 127 | 130 | 143 |

| 133 | 127 | 132 | 144 |

| 134 | 127 | 132 | 145 |

| 134 | 127 | 132 | 147 |

| 135 | 129 | 132 | 151 |

| 137 | 130 | 132 | 152 |

| 138 | 130 | 132 | 153 |

| 138 | 130 | 133 | 153 |

| 138 | 130 | 135 | 155 |

| 139 | 130 | 135 | 155 |

| 139 | 130 | 135 | 158 |

| 139 | 130 | 138 | 158 |

| 140 | 130 | 138 | 162 |

| 140 | 130 | 138 | 163 |

| 140 | 130 | 140 | 163 |

| 140 | 131 | 140 | 163 |

| 141 | 133 | 141 | 168 |

| 141 | 133 | 141 | 174 |

| 141 | 133 | 141 | 187 |

| 141 |

133 | 142 | 215 |

| 144 | 135 | 142 | 215 |

| 146 | 135 | 145 | 220 |

| 146 | 135 | 147 | 221 |

| 148 | 138 | 147 | 222 |

| 149 | 138 | 147 | 225 |

| 149 | 138 | 147 | 225 |

| 151 | 138 | 147 | 237 |

| 151 | 138 | 147 | 305 |

| 152 | 138 | 147 | 305 |

| 152 | 138 | 147 | 311 |

| 161 |

138 | 148 | 342 |

| 163 | 141 | 150 | 346 |

| 165 |

143 | 150 | 358 |

| 204 |

147 | 150 | 358 |

| 209 |

147 | 150 |

358 |

| 218 |

150 | 154 | 358 |

| 219 |

150 |

154 | 363 |

| 233 |

153 | 155 | 376 |

| 236 |

154 | 157 | 383 |

| 238 | 154 | 157 | 395 |

| 238 |

154 |

157 | 395 |

| 241 | 157 | 157 | 397 |

| 243 |

157 |

157 | 399 |

| 248 |

160 | 160 | 425 |

| 254 |

160 |

160 | 426 |

| 254 |

164 | 160 | 430 |

| 272 |

168 |

160 | 431 |

| 272 |

205 |

162 | 431 |

| 275 |

212 |

162 | 435 |

| 351 |

227 |

174 | 435 |

| 366 |

229 |

178 | 435 |

| 367 |

229 |

207 | 435 |

| 374 |

229 |

211 | 436 |

| 378 |

232 |

213 | 436 |

| 384 |

241 |

214 |

441 |

| 388 |

246 |

216 | 446 |

| 388 |

246 |

225 |

446 |

| 391 |

252 |

226 |

446 |

| 392 |

252 |

230 |

446 |

| 392 |

260 | 235 | 452 |

| 395 |

264 |

240 | 452 |

| 395 |

269 |

256 | 452 |

| 397 |

286 |

270 | 452 |

| 399 |

295 | 294 | 452 |

| 402 |

300 | 312 | 457 |

| 402 |

304 |

339 |

457 |

| 488 |

304 |

352 | 457 |

| 495 |

314 | 360 | 458 |

| 501 |

314 |

367 |

458 |

| 521 |

314 |

411 | 458 |

| 545 | 317 |

427 | 458 |

| 559 |

349 |

431 | 463 |

| 570 |

370 | 437 | 464 |

| 434 | 437 | 464 | |

| 434 | 437 | 470 | |

| 434 | 443 | 470 | |

| 434 | 443 | 470 | |

| 434 | 447 | 474 | |

| 434 | 447 | 483 | |

| 434 | 447 | 483 | |

| 436 | 447 | 483 | |

| 436 | 447 | 483 | |

| 436 | 452 | 496 | |

| 441 | 452 | 524 | |

| 441 | 454 | 540 | |

| 441 | 454 | 548 |

|

| 441 | 454 | 562 | |

| 441 | 454 | 562 | |

| 441 | 454 | 565 | |

| 441 | 454 | 565 | |

| 441 | 454 | 565 | |

| 441 | 454 | 574 | |

| 441 | 458 | 574 | |

| 441 | 458 | 574 | |

| 441 | 458 | 574 | |

| 441 | 458 | 574 | |

| 446 | 458 | 574 |

|

| 446 | 458 | 578 | |

| 447 | 458 | 578 | |

| 447 | 463 | 578 | |

| 447 | 463 |

586 | |

| 447 | 464 | 592 | |

| 447 | 464 | 592 | |

| 447 | 469 | 592 | |

| 451 | 469 |

592 | |

| 454 | 475 | 592 | |

| 454 | 475 | 592 |

|

| 454 | 475 |

612 | |

| 460 | 480 | 633 |

|

| 460 | 480 | 667 | |

| 460 | 519 | 679 | |

| 460 | 538 |

679 | |

| 517 |

538 |

679 |

|

| 524 | 553 | 732 |

|

| 524 |

563 | 732 |

|

| 539 | 563 | 733 |

|

| 539 |

563 |

746 | |

| 546 | 568 | 747 | |

| 546 | 568 | 761 | |

| 546 |

571 | 761 | |

| 546 |

571 | 774 | |

| 549 | 571 | 777 | |

| 549 | 579 | 941 |

|

| 549 |

579 | 1,135 |

|

| 549 |

579 | ||

| 549 |

579 |

||

| 554 | 584 |

||

| 554 | 592 | ||

| 554 | 596 | ||

| 554 | 596 | ||

| 554 | 596 | ||

| 554 | 596 | ||

| 554 |

601 | ||

| 562 | 601 | ||

| 563 | 610 | ||

| 563 |

643 | ||

| 563 |

643 | ||

| 570 | 654 | ||

| 570 | 679 |

||

| 579 |

698 | ||

| 702 |

|||

| 714 |

|||

| 722 | |||

| 722 |

|||

| 775 |

|||

| 775 |

|||

Note.— The peak area of each band was analyzed by ImageQuant; peak areas <3% of the total area of all the peaks in one sample (underlined) were not counted and not used in the statistical analysis.

Table C2.

Statistical Analysis

| Comparison of Samples | Mann-Whitney P Value |

| C1 versus C5 | <.001 |

| C5 versus A5 | .007 |

| C5 versus E5 | <.001 |

| Fisher’s Exact Test Two-Tailed P Value |

|

| C1 versus C5a | .001 |

| C1 versus C5b | .16 |

| C5 versus A5c | <.001 |

| C5 versus A5d | 1 |

| C5 versus E5e | <.001 |

| C5 versus E5f | 1 |

Eight percent of alleles were larger than the largest C1 control allele, (CTG)545.

Three percent of alleles were smaller than the smallest C1 control allele, (CTG)63.

Ten percent of alleles were larger than the largest C5 control allele, (CTG)570.

None of the alleles were smaller than the smallest C5 control allele, (CTG)56.

Thirteen percent of alleles were larger than the largest C5 control allele, (CTG)570.

None of the alleles were smaller than the smallest C5 control allele, (CTG)56.

Electronic-Database Information

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- Fisher’s Exact Test Web site, http://matforsk.no/ola/fisher.htm

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for DM1) [PubMed]

References

- Anvret M, Ahlberg G, Grandell U, Hedberg B, Johnson K, Edstrom L (1993) Larger expansions of the CTG repeat in muscle compared to lymphocytes from patients with myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2:1397–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashizawa T, Monckton DG, Vaishnav S, Patel BJ, Voskova A, Caskey CT (1996) Instability of the expanded (CTG)n repeats in the myotonin protein kinase gene in cultured lymphoblastoid cell lines from patients with myotonic dystrophy. Genomics 36:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez J, Robledo M, Ramos C, Ayuso C, Astarloa R, Garcia Yebenes J, Brambati B (1995) Somatic stability in chorionic villi samples and other Huntington fetal tissues. Hum Genet 96:229–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breschel TS, McInnis MG, Margolis RL, Sirugo G, Corneliussen B, Simpson SG, McMahon FJ, MacKinnon DF, Xu JF, Pleasant N, Huo Y, Ashworth RG, Grundstrom C, Grundstrom T, Kidd KK, DePaulo JR, Ross CA (1997) A novel, heritable, expanding CTG repeat in an intron of the SEF2–1 gene on chromosome 18q21.1. Hum Mol Genet 6:1855–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhans WC, Vassilev LT, Wu J, Sogo JM, Nallaseth FS, DePamphilis ML (1991) Emetine allows identification of origins of mammalian DNA replication by imbalanced DNA synthesis, not through conservative nucleosome segregation. Embo J 10:4351–4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilkova O, Jonsson BH, Johansson E (2003) The quaternary structure of DNA polymerase epsilon from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 278:14082–14086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JB (1997) The ring cloning technique. In: Doyle BGA (ed) Mammalian cell culture: essential techniques. John Wiley & Sons, New York, p 93 [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JD, Nichol K, Wang YH, Pearson CE (2002) Evidence of cis-acting factors in replication-mediated trinucleotide repeat instability in primate cells. Nat Genet 31:37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JD, Pearson CE (2003) The contribution of cis-elements to disease-associated repeat instability: clinical and experimental evidence. Cytogenet Genome Res 100:25–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’orco RT (1974) Maintenance of human diploid fibroblasts as arrested populations. Fed Proc 33:1969–1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’orco RT, Whittle WL (1978) Unscheduled DNA synthesis in confluent and mitotically arrested populations of aging human diploid fibroblasts. Mech Ageing Dev 8:269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietmaier W, Wallinger S, Bocker T, Kullmann F, Fishel R, Ruschoff J (1997) Diagnostic microsatellite instability: definition and correlation with mismatch repair protein expression. Cancer Res 57:4749–4756 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Richards S, Verkerk AJ, Holden JJ, Fenwick RG Jr, Warren ST, Oostra BA, Nelson DL Caskey CT (1991) Variation of the CGG repeat at the fragile X site results in genetic instability: resolution of the Sherman paradox. Cell 67:1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furling D, Coiffier L, Mouly V, Barbet JP, St Guily JL, Taneja K, Gourdon G, Junien C, Butler-Browne GS (2001) Defective satellite cells in congenital myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 10:2079–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautschi JR, Young BR, Cleaver JE (1973) Repair of damaged DNA in the absence of protein synthesis in mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res 76:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Pereira M, Fortune MT, Monckton DG (2001) Mouse tissue culture models of unstable triplet repeats: in vitro selection for larger alleles, mutational expansion bias and tissue specificity, but no association with cell division rates. Hum Mol Genet 10:845–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib M, Fares F, Bourgeois CA, Bella C, Bernardino J, Hernandez-Blazquez F, de Capoa A, Niveleau A (1999) DNA global hypomethylation in EBV-transformed interphase nuclei. Exp Cell Res 249:46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy CA, Rice GC, Kovacs M, Schimke RT (1987) Over-replication of DNA in S phase Chinese hamster ovary cells after DNA synthesis inhibition. J Biol Chem 262:11927–11934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal SM, Lindor NM, Michels VV, Buckley DD, Hoppe DA, Sarkar G, Dewald GW (1993) Absence of chromosome fragility at 19q13.3 in patients with myotonic dystrophy. Am J Med Genet 46:441–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen G, Willems P, Coerwinkel M, Nillesen W, Smeets H, Vits L, Howeler C, Brunner H, Wieringa B (1994) Gonosomal mosaicism in myotonic dystrophy patients: involvement of mitotic events in (CTG)n repeat variation and selection against extreme expansion in sperm. Am J Hum Genet 54:575–585 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedele KB, Wahl D, Chahrokh-Zadeh S, Wirtz A, Murken J, Holinski-Feder E (1998) Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA): somatic stability of an expanded CAG repeat in fetal tissues. Clin Genet 54:148–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan R, Vonarx EJ, Straffon AF, Simon M, Faye G, Kunz BA (2000) Evidence from mutational specificity studies that yeast DNA polymerases delta and epsilon replicate different DNA strands at an intracellular replication fork. J Mol Biol 299:405–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajavi M, Tari AM, Patel NB, Tsuji K, Siwak DR, Meistrich ML, Terry NH, Ashizawa T (2001) “Mitotic drive” of expanded CTG repeats in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1). Hum Mol Genet 10:855–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Osanai R, Kikkawa M, Adachi A, Ohtake T, Komori T, Hashimoto K, Itoyama S, Mitarai T, Hirose K (2002) A patient with myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM 1) accompanied by laryngeal and renal cell carcinomas had a small CTG triplet repeat expansion but no somatic instability in normal tissues. Intern Med 41:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PR, Pearson CE, Sinden RR (1996) Stability of triplet repeats of myotonic dystrophy and fragile X loci in human mutator mismatch repair cell lines. Hum Genet 98:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krude T (1999) Mimosine arrests proliferating human cells before onset of DNA replication in a dose-dependent manner. Exp Cell Res 247:148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahue RS, Slater DL (2003) DNA repair and trinucleotide repeat instability. Front Biosci 8:S653–S665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzmeier BA, Freudenreich CH (2003) Trinucleotide repeat instability: a hairpin curve at the crossroads of replication, recombination, and repair. Cytogenet Genome Res 100:7–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lia AS, Seznec H, Hofmann-Radvanyi H, Radvanyi F, Duros C, Saquet C, Blanche M, Junien C, Gourdon G (1998) Somatic instability of the CTG repeat in mice transgenic for the myotonic dystrophy region is age dependent but not correlated to the relative intertissue transcription levels and proliferative capacities. Hum Mol Genet 7:1285–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby RT, Monckton DG, Fu YH, Martinez RA, McAbney JP, Lau R, Einum DD, Nichol K, Ware CB, Ptacek LJ, Pearson CE, La Spada AR (2003) Genomic context drives SCA7 CAG repeat instability, while expressed SCA7 cDNAs are intergenerationally and somatically stable in transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 12:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell L, Johnson K, Boucher CA, Baiget M (1997) Somatic instability of the myotonic dystrophy (CTG)n repeat during human fetal development. Hum Mol Genet 6:877–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell L, Monckton DG, Gamez J, Johnson KJ, Gich I, de Munain AL, Baiget M (1998) Progression of somatic CTG repeat length heterogeneity in the blood cells of myotonic dystrophy patients. Hum Mol Genet 7:307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael WM, Ott R, Fanning E, Newport J (2000) Activation of the DNA replication checkpoint through RNA synthesis by primase. Science 289:2133–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monckton DG, Wong LJ, Ashizawa T, Caskey CT (1995) Somatic mosaicism, germline expansions, germline reversions and intergenerational reductions in myotonic dystrophy males: small pool PCR analyses. Hum Mol Genet 4:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto M, Takebayashi H, Kawaguchi Y, Narumiya S, Taniwaki M, Nakamura Y, Ishikawa Y, Akiguchi I, Kimura J, Kakizuka A (1997) A CAG/CTG expansion in the normal population. Nat Genet 17:385–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville CE, Mahadevan MS, Barcelo JM, Korneluk RG (1994) High resolution genetic analysis suggests one ancestral predisposing haplotype for the origin of the myotonic dystrophy mutation. Hum Mol Genet 3:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouspikel T, Hanawalt PC (2002) DNA repair in terminally differentiated cells. DNA Repair 1:59–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim A, Shlomai Z, Ben-Bassat H (1981) Initiation points for cellular deoxyribonucleic acid replication in human lymphoid cells converted by Epstein-Barr virus. Mol Cell Biol 1:753–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai R, Kinoshita M, Hirose K, Homma T, Kawabata I (2000) CTG triplet repeat expansion in a laryngeal carcinoma from a patient with myotonic dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 23:804–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CE (2003) Slipping while sleeping? Trinucleotide expansions in germ cells. Trends Mol Med 9:483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CE, Tam M, Wang YH, Montgomery SE, Dar A, Cleary JD, Nichol K (2002) Slipped-strand DNAs formed by long (CAG)·(CTG) repeats: slipped-out repeats and slip-out junctions. Nucleic Acids Res 30:4534–4547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin B, Logar N, Zidar J (1996) CTG repeat analysis in lymphocytes, muscles and fibroblasts in patients with myotonic dystrophy. Pflugers Arch 431:R199–R200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim JS (2000) Development of human cell lines from multiple organs. Ann NY Acad Sci 919:16–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saintigny Y, Delacote F, Vares G, Petitot F, Lambert S, Averbeck D, Lopez BS (2001) Characterization of homologous recombination induced by replication inhibition in mammalian cells. Embo J 20:3861–3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadashwily GM, Raca G, Mirkin SM (1997) Trinucleotide repeats affect DNA replication in vivo. Nat Genet 17:298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo JM, Lopes M, Foiani M (2002) Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science 297:599–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel R, La Spada AR, Kress W, Fischbeck KH, Schmid W (1996) Somatic stability of the expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat in X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Hum Mutat 8:32–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimac E, Housman D, Huberman JA (1977) Effects of inhibition of protein synthesis on DNA replication in cultured mammalian cells. J Mol Biol 115:485–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland GR, Richards RI (1999) Fragile sites—cytogenetic similarity with molecular diversity. Am J Hum Genet 64:354–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton CA, Johnson K, Moxley RT 3rd (1994) Myotonic dystrophy patients have larger CTG expansions in skeletal muscle than in leukocytes. Ann Neurol 35:104–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger SL, Giangreco CA, Tarleton J, Wessel HB (1996) Inability to induce fragile sites at CTG repeats in congenital myotonic dystrophy. Am J Med Genet 66:60–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, Kennerknecht I, Wolf M, Enders H, Schwemmle S, Steinbach P (1995) Heterogeneity of DM kinase repeat expansion in different fetal tissues and further expansion during cell proliferation in vitro: evidence for a casual involvement of methyl-directed DNA mismatch repair in triplet repeat stability. Hum Mol Genet 4:1147–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LJ, Ashizawa T, Monckton DG, Caskey CT, Richards CS (1995) Somatic heterogeneity of the CTG repeat in myotonic dystrophy is age and size dependent. Am J Hum Genet 56:114–122 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R, Shivji MK (1997) Which polymerases are used for DNA-repair in eukaryotes? Carcinogenesis 18:605–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]