Abstract

A variety of inherited human disorders affecting skeletal muscle contraction, heart rhythm, and nervous system function have been traced to mutations in genes encoding voltage-gated sodium channels. Clinical severity among these conditions ranges from mild or even latent disease to life-threatening or incapacitating conditions. The sodium channelopathies were among the first recognized ion channel diseases and continue to attract widespread clinical and scientific interest. An expanding knowledge base has substantially advanced our understanding of structure-function and genotype-phenotype relationships for voltage-gated sodium channels and provided new insights into the pathophysiological basis for common diseases such as cardiac arrhythmias and epilepsy.

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVChs) are important for the generation and propagation of signals in electrically excitable tissues like muscle, the heart, and nerve. Activation of NaVChs in these tissues causes the initial upstroke of the compound action potential, which in turn triggers other physiological events leading to muscular contraction and neuronal firing. NaVChs are also important targets for local anesthetics, anticonvulsants, and antiarrhythmic agents.

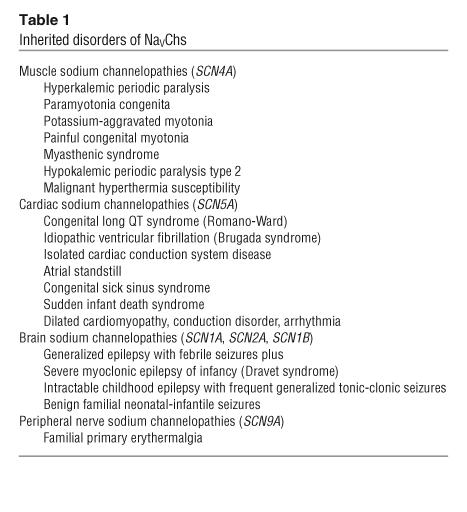

The essential nature of NaVChs is emphasized by the existence of inherited disorders (sodium “channelopathies”) caused by mutations in genes that encode these vital proteins. Nearly 20 disorders affecting skeletal muscle contraction, cardiac rhythm, or neuronal function and ranging in severity from mild or latent disease to life-threatening or incapacitating conditions have been linked to mutations in human NaVCh genes (Table 1). Most sodium channelopathies are dominantly inherited, but some are transmitted by recessive inheritance or appear sporadic. Additionally, certain pharmacogenetic syndromes have been traced to variants in NaVCh genes. The clinical manifestations of these disorders depend primarily on the expression pattern of the mutant gene at the tissue level and the biophysical character of NaVCh dysfunction at the molecular level.

Table 1.

Inherited disorders of NaVChs

This review will cover the current state of knowledge of human sodium channelopathies and illustrate important links among clinical, genetic, and pathophysiological features of the major syndromes with the corresponding biophysical properties of mutant NaVChs. An initial brief overview of the structure and function of NaVChs will provide essential background information needed to understand the nuances of these relationships. This will be followed by a review of the major syndromes, organized by affected tissue. Emphasis will be placed on relating clinical phenotypes to patterns of channel dysfunction that underlie pathophysiology of these conditions.

Structure and function of NaVChs

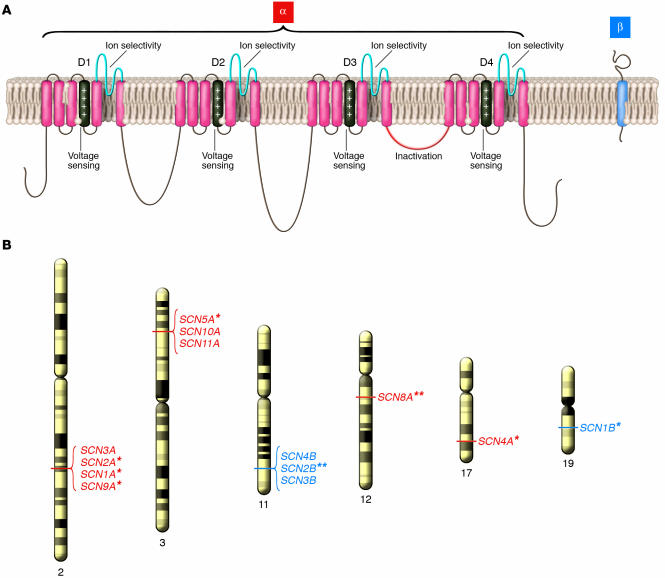

Sodium channels are heteromultimeric, integral membrane proteins belonging to a superfamily of ion channels that are gated (opened and closed) by changes in membrane potential (1, 2). Sodium channel proteins from mammalian brain, muscle, and myocardium consist of a single large (approximately 260 kDa) pore-forming α subunit complexed with 1 or 2 smaller accessory β subunits (Figure 1). Nine genes (SCN1A, SCN2A, etc.) encoding distinct α subunit isoforms and 4 β subunit genes (SCN1B, SCN2B, etc.) have been identified in the human genome. Many isoforms are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous system (3), while skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle express more restricted NaVCh repertoires (4–9). The α subunits are constructed with a 4-fold symmetry consisting of structurally homologous domains (D1–D4) each containing 6 membrane-spanning segments (S1–S6) and a region (S5–S6 pore loop) controlling ion selectivity and permeation (Figure 1). The S4 segment, which functions as a voltage sensor (10, 11), is amphipathic with multiple basic amino acids (arginine or lysine) at every third position surrounded by hydrophobic residues. Each domain resembles an entire voltage-gated potassium channel subunit as well as a primitive bacterial NaVCh (12).

Figure 1.

Structure and genomic location of human NaVChs. (A) Simple model representing transmembrane topology of α and β NaVCh subunits. Structural domains mediating key functional properties are labeled. (B) Chromosomal location of human genes encoding α (red) and β (blue) subunits across the genome. An asterisk next to the gene name indicates association with an inherited human disease. A double asterisk indicates association with murine phenotypes.

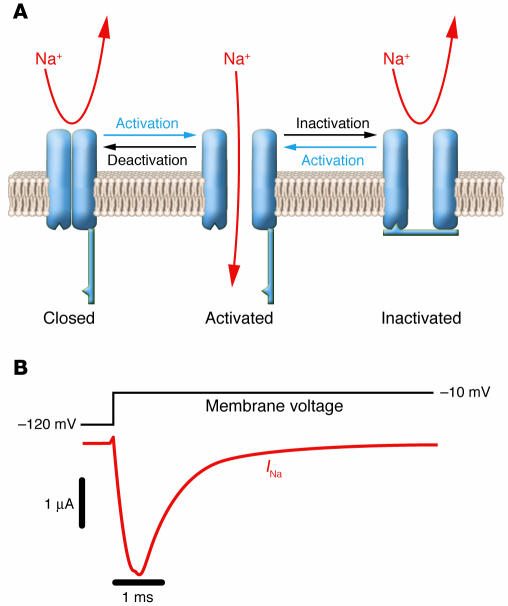

NaVChs switch between 3 functional states depending on the membrane potential (Figure 2) (13). In excitable membranes, a sudden membrane depolarization causes a rapid rise in local Na+ permeability due to the opening (activation) of NaVChs from their resting closed state. For this to occur, voltage sensors (the 4 S4 segments) within the NaVCh protein must move in an outward direction, propelled by the change in membrane potential, and then translate this conformational energy to other structures (most likely S6 segments) that swing out of the way of incoming Na+ ions. This increase in Na+ permeability causes the sudden membrane depolarization that characterizes the initial phase of an action potential. Normally, activation of NaVChs is transient owing to inactivation, another gating process mediated by structures located on the cytoplasmic face of the channel protein (mainly the D3–D4 linker). NaVChs cannot reopen until the membrane is repolarized and they undergo recovery from inactivation. Membrane repolarization is achieved by fast inactivation of NaVChs and is augmented by activation of voltage-gated potassium channels. During recovery from inactivation, NaVChs may undergo deactivation, the transition from the open to the closed state (14). Activation, inactivation, and recovery from inactivation occur within a few milliseconds. In addition to these rapid gating transitions, NaVChs are also susceptible to closing by slower inactivating processes (slow inactivation) if the membrane remains depolarized for a longer time (15). These slower events may contribute to determining the availability of active channels under various physiological conditions.

Figure 2.

Functional properties of NaVChs. (A) Schematic representation of an NaVCh undergoing the major gating transitions. (B) Voltage-clamp recording of NaVCh activity in response to membrane depolarization. Downward deflection of the current trace (red) corresponds to inward movement of Na+.

Muscle sodium channelopathies

Disturbances in the function of muscle NaVChs can affect the ability of skeletal muscle to contract or relax. Two symptoms are characteristic of muscle membrane (sarcolemma) NaVCh dysfunction, myotonia and periodic paralysis (16). Myotonia is characterized by delayed relaxation of muscle following a sudden forceful contraction and is associated with repetitive action potential generation, a manifestation of sarcolemmal hyperexcitability. By contrast, periodic paralysis represents a transient state of hypoexcitability or inexcitability in which action potentials cannot be generated or propagated.

Periodic paralysis and myotonia.

Periodic paralysis is characterized by episodic weakness or paralysis of voluntary muscles occurring with normal neuromuscular transmission and in the absence of motor neuron disease. Patients with familial periodic paralysis present typically in childhood (17). Attacks of weakness are often associated with changes in the serum potassium (K+) concentration as a result of abrupt redistribution of intracellular and extracellular K+. This clinical epiphenomenon forms the basis for classifying periodic paralysis as hypokalemic, hyperkalemic, or normokalemic. In paramyotonia congenita, the dominant symptom is cold-induced muscle stiffness and weakness (17, 18). Potassium-aggravated myotonia is characterized by myotonia without weakness and worsening symptoms following K+ ingestion (19). In general, these disorders are not associated with disabling muscular dystrophy, although chronic weakness may develop in some individuals with long-standing hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (20).

In vitro electrophysiological studies determined that both myotonia and periodic paralysis are associated with abnormal muscle cell membrane sodium conductance (21), and these findings pointed to SCN4A as the most plausible candidate gene. Genetic linkage studies confirmed this hypothesis (22–24). Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis, paramyotonia congenita, and potassium-aggravated myotonia are all associated with missense mutations in SCN4A. There are 2 predominant mutations associated with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (T704M and M1592V), and these occur independently in unrelated kindreds (20, 25). Allelic diversity is greater for paramyotonia congenita and potassium-aggravated myotonia (26–32). In addition, approximately 15% of patients with genotype-defined hypokalemic periodic paralysis carry SCN4A mutations (33). Patients with SCN4A mutations may present rarely with life-threatening myotonic reactions upon exposure to succinylcholine resembling the syndrome of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility (34, 35). In 1 report, congenital myasthenia has been linked to SCN4A mutations (36).

Characterization of SCN4A mutations and pathophysiology.

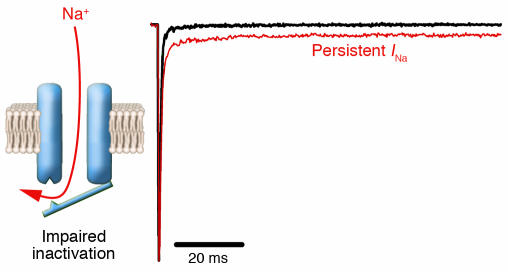

Using heterologously expressed recombinant NaVChs, several laboratories have characterized the biophysical properties of many mutations associated with either periodic paralysis or various myotonic disorders. These studies demonstrated that variable defects in the rate or extent of inactivation occur in virtually all cases. Mutations associated with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis exhibit incomplete inactivation leading to a small level (1–2% of peak current) of persistent Na+ current that is predicted to cause sustained muscle fiber depolarization (Figure 3) (37, 38). Sustained depolarization will cause the majority of NaVChs (mutant and wild type) to become inactivated, and this explains conduction failure and electrical inexcitability observed in skeletal muscle during an attack of periodic paralysis (39, 40). By this mechanism, mutant NaVChs exert an indirect dominant-negative effect on normal channels. In addition, some, but not all, mutations associated with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis have impaired slow inactivation (41), and this may contribute to sustaining the effect of persistent Na+ current (42).

Figure 3.

A common form of defective inactivation exhibited by mutant NaVChs associated with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis, long QT syndrome, and inherited epilepsy. The defect is caused by incomplete closure of the inactivation gate (left panel) resulting in an increased level of persistent current (right panel, red trace) as compared with NaVChs with normal inactivation (black trace).

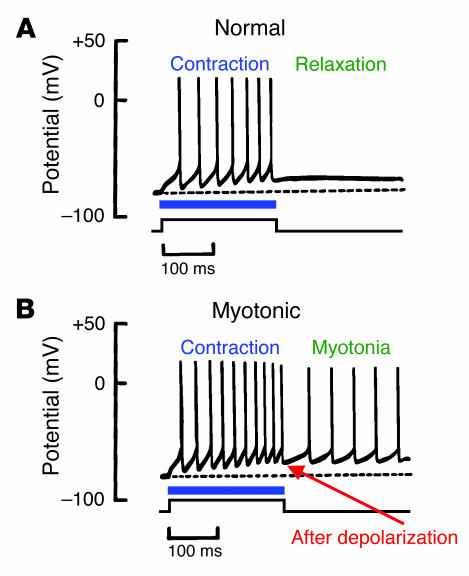

SCN4A mutations in the myotonic disorders slow the rate of inactivation, speed recovery from inactivation, and slow deactivation (30, 43–47). These biophysical defects are predicted to lengthen the duration of muscle action potentials (48). Prolongation of action potentials along T-tubule membranes will exaggerate the local rise in extracellular K+ concentration by efflux through persistently activated potassium channels. Extracellular K+ in T-tubules exerts a depolarizing effect on the resting membrane potential, increasing the probability of an aberrant afterdepolarization. A large afterdepolarization can trigger spontaneous action potentials in adjacent surface membranes, which in turn cause persistent muscle contraction and delayed relaxation, the physiological hallmarks of myotonia (Figure 4) (49).

Figure 4.

Differences between normal and myotonic muscle action potentials. (A) Generation of action potential spikes during electrical stimulation (horizontal blue line and square wave) of a normal muscle fiber. Contraction occurs during action potential firing, followed by muscle relaxation when stimulation ceases. (B) Action potentials in myotonic muscle during and immediately after electrical stimulation. An afterdepolarization triggers spontaneous action potentials that fire after termination of the electrical stimulus (myotonic activity).

Treatment strategies for muscle sodium channelopathies.

Pharmacological treatment for periodic paralysis with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors is often successful, but the mechanism of action is poorly understood (50, 51). Certain local anesthetic/antiarrhythmic agents have antimyotonic activity and are sometimes useful treatments for nondystrophic myotonias (52, 53). These drugs are effective because of their ability to interrupt rapidly conducted trains of action potentials through their use-dependent NaVCh-blocking action. Mexiletine is the most commonly used antimyotonic agent, and there have been in vitro studies demonstrating its effectiveness (54), but there have been no clinical trials comparing this agent with either placebo or other treatments. A more potent NaVCh blocker, flecainide, may also have utility in severe forms of myotonia that are resistant to mexiletine (55). The efficacy of flecainide for treating myotonia associated with certain SCN4A mutations may be greatest when there is a depolarizing shift of the steady-state fast inactivation curve for the mutant channel, whereas mutations that induce hyperpolarizing shifts in this curve are predicted to have greater sensitivity to mexiletine (56). Long-term treatment of myotonia with NaVCh blockers is often limited by drug side effects.

Cardiac sodium channelopathies

In the heart, NaVChs are essential for the orderly progression of action potentials from the sinoatrial node, through the atria, across the atrioventricular node, along the specialized conduction system of the ventricles (His-Purkinje system), and ultimately throughout the myocardium to stimulate rhythmic contraction. Mutations in SCN5A, the gene encoding the principal NaVCh α subunit expressed in the human heart, cause inherited susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia (congenital long QT syndrome, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation) (57–59), impaired cardiac conduction (60), or both (61–65). SCN5A mutations may also manifest as drug-induced arrhythmias (66), sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (67, 68), and other forms of arrhythmia susceptibility (69).

Inherited arrhythmia syndromes: long QT and Brugada.

Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS), an inherited condition of abnormal myocardial repolarization, is characterized clinically by an increased risk of potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias, especially torsade de pointes (70, 71). The syndrome is transmitted most often in families as an autosomal dominant trait (Romano-Ward syndrome) and less commonly as an autosomal recessive disease combined with congenital deafness (Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome). The syndrome derives its name from the characteristic prolongation of the QT interval on surface ECGs of affected individuals, a surrogate marker of an increased ventricular action potential duration and abnormal myocardial repolarization. Approximately 10% of LQTS cases are caused by SCN5A mutations, whereas the majority of Romano-Ward subjects harbor mutations in 2 cardiac potassium channel genes (KCNQ1 and HERG) (72, 73). Triggering factors associated with arrhythmic events are different among genetic subsets of LQTS. SCN5A mutations often produce distinct clinical features including bradycardia, and a tendency for cardiac events to occur during sleep or rest (74, 75).

Mutations in SCN5A have also been associated with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, including Brugada syndrome (59, 76) and sudden unexplained death syndrome (SUDS) (77, 78). Individuals with Brugada syndrome have an increased risk for potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias (polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation) without concomitant ischemia, electrolyte abnormalities, or structural heart disease. Individuals with the disease often exhibit a characteristic ECG pattern consisting of ST elevation in the right precordial leads, apparent right bundle branch block, but normal QT intervals (79). Administration of NaVCh-blocking agents (i.e., procainamide, flecainide, ajmaline) may expose this ECG pattern in latent cases (80). Inheritance is autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance and a male predominance. A family history of unexplained sudden death is typical. SUDS is a very similar syndrome that causes sudden death, typically during sleep, in young and middle-aged males in Southeast Asian countries (81–83).

Disorders of cardiac conduction.

Mutations in SCN5A are also associated with heterogeneous familial disorders of cardiac conduction manifest as impaired atrioventricular conduction (heart block), slowed intramyocardial conduction velocity, or atrial inexcitability (atrial standstill) (60, 62, 84, 85). The degree of impaired cardiac conduction may progress with advancing age and is generally not associated with prolongation of the QT interval or ECG changes consistent with Brugada syndrome. Heart block in these disorders is usually the result of conduction slowing in the His-Purkinje system. In most cases, inheritance of the phenotype is autosomal dominant. By contrast, atrial standstill has been reported to occur either as a recessive disorder of SCN5A (congenital sick sinus syndrome) (85) or by digenic inheritance of a heterozygous SCN5A mutation with a promoter variant in the connexin-40 gene (84).

Mutations in SCN5A may also cause more complex phenotypes representing combinations of LQTS, Brugada syndrome, and conduction system disease. There have been documented examples of LQTS combined with Brugada syndrome (63) or congenital heart block (86, 87), and cases of Brugada syndrome with impaired conduction (88). In 1 unique family, all 3 clinical phenotypes occur together (65). SCN5A mutations have also been discovered in families segregating impaired cardiac conduction, supraventricular arrhythmia, and dilated cardiomyopathy (64, 89). Certain mutations may manifest different phenotypes in different families.

Characterization of SCN5A mutations and arrhythmogenesis.

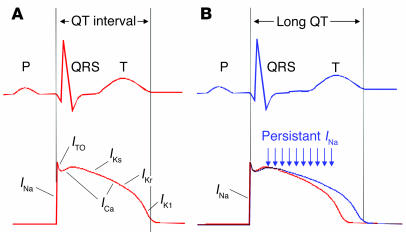

The clinical heterogeneity associated with SCN5A mutations is partly explained by corresponding differences in the degree and characteristics of channel dysfunction. In congenital LQTS, SCN5A mutations have a dominant gain-of-function phenotype at the molecular level. Specifically, most mutant cardiac NaVChs associated with LQTS exhibit a characteristic impairment of inactivation, leading to persistent inward Na+ current during prolonged membrane depolarizations (Figure 3) (90–92). A general slowing of inactivation may be present in mutations associated with severe LQTS (93), while some mutations alter voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation but do not have measurable non-inactivating current (94). Persistent Na+ current during the cardiac action potential explains abnormal myocardial repolarization in LQTS (95). By contrast with nerve and muscle, cardiac action potentials last several hundred milliseconds because of a prolonged depolarization phase (plateau), the result of opposing inward (mainly Na+ and Ca2+) and outward (K+) ionic currents. Repolarization occurs when net outward current exceeds net inward current. Non-inactivating behavior of mutant cardiac NaVChs will shift this balance toward inward current and delay onset of repolarization, thus lengthening the action potential duration and the corresponding QT interval (Figure 5). Delayed repolarization predisposes to ventricular arrhythmias by exaggerating the dispersion of refractoriness throughout the myocardium and increasing the probability of early afterdepolarization, a phenomenon caused largely by reactivation of calcium channels during the action potential plateau (96). Both of these phenomena create conditions that allow electrical signals from depolarized regions of the heart to prematurely re-excite adjacent myocardium that has already repolarized, the basis for a reentrant arrhythmia. Additional proof of the role of cardiac NaVCh mutations in LQTS has come from studies of mice heterozygous for a prototypic LQTS SCN5A mutation (delKPQ). These mice have spontaneous life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and a persistent Na+ current in cardiac myocytes (97). SCN5A mutations associated with SIDS also exhibit this biophysical phenotype; this suggests a pathophysiological relationship with LQTS (67, 68).

Figure 5.

Electrophysiological basis for LQTS. (A) Relationship of surface ECG (top) with a representative cardiac action potential (bottom). The QT interval approximates the action potential duration. Individual ionic currents responsible for different phases of the action potential are labeled. (B) Prolongation of the QT interval and corresponding abnormal cardiac action potential (blue) resulting from persistent sodium current. ICa, calcium current; IK1, inward rectifier current; IKr, rapid component of delayed rectifier current; IKs, slow component of delayed rectifier current; INa, sodium current; ITO, transient outward current.

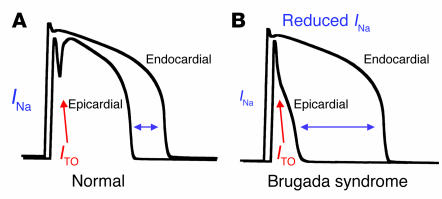

The proposed cellular basis of Brugada syndrome involves a primary reduction in myocardial sodium current that exaggerates differences in action potential duration between the inner (endocardium) and outer (epicardium) layers of ventricular muscle (96, 98, 99). These differences exist initially because of an unequal distribution of potassium channels responsible for the transient outward current (ITO), a repolarizing current more prominent in the epicardial layer that contributes to the characteristic spike and dome shape of the cardiac action potential. Reduced myocardial Na+ current will cause disproportionate shortening of epicardial action potentials because of unopposed ITO, leading to an exaggerated transmural voltage gradient, dispersion of repolarization, and a substrate promoting reentrant arrhythmias (Figure 6). This hypothesis has been validated using animal models and computational methods. The theory helps explain the characteristic ECG pattern observed in Brugada syndrome and the effects of NaVCh-blocking agents to aggravate the phenotype.

Figure 6.

Electrophysiological basis for Brugada syndrome. (A) Comparison of endocardial and epicardial action potentials in normal heart. The epicardial action potential is shorter because of large transient outward current. (B) Endocardial and epicardial action potentials in Brugada syndrome. Reduced sodium current causes disproportionate shortening of epicardial action potentials with resulting exaggeration of the transmural voltage gradient (horizontal double arrow).

Consistent with reduced sodium current as the primary pathophysiological event in Brugada syndrome, many SCN5A mutations associated with this disease cause frameshift errors, splice site defects, or premature stop codons (59, 100) that are predicted to produce nonfunctional channels. Furthermore, some missense mutations have also been demonstrated to be nonfunctional because of either impaired protein trafficking to the cell membrane or presumed disruption of Na+ conductance through the channel (101–104). However, other missense mutations associated with Brugada syndrome are functional but have biophysical defects predicted to reduce channel availability, such as altered voltage-dependence of activation, more rapid fast inactivation, and enhanced slow inactivation (105–107).

Pathophysiology of SCN5A dysfunction in cardiac conduction disorders.

Defects in cardiac NaVCh function due to mutations associated with disorders of cardiac conduction exhibit more complex biophysical properties (61, 62). Mutations causing isolated conduction defects have generally been observed to cause reduced NaVCh availability as a consequence of mixed gating disturbances. In the case of a Dutch family segregating a specific missense allele (G514C), the mutation causes unequal depolarizing shifts in the voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation such that a smaller number of channels are activated at typical threshold voltages (61). Computational modeling of these changes supports reduced conduction velocity, but the level of predicted NaVCh loss is insufficient to cause shortened epicardial action potentials, which explains why these individuals do not manifest Brugada syndrome. Two other SCN5A mutations causing isolated conduction disturbances (G298S and D1595N) are also predicted to reduce channel availability by enhancing the tendency of channels to undergo slow inactivation in combination with a complex mix of gain- and loss-of-function defects (62). However, other alleles exhibiting complete loss of function have also been associated with isolated cardiac conduction disease (108, 109) without the Brugada syndrome. These observations suggest that additional host factors may contribute to determining whether a mutation will manifest as arrhythmia susceptibility or impaired conduction. This idea is supported by the observation that a single SCN5A mutation causes either Brugada syndrome or isolated conduction defects in different members of a large French family (88).

Biophysical properties of mutant cardiac NaVChs associated with combined phenotypes are also more complex. An in-frame insertion mutation (1795insD) has been identified in a family segregating both LQTS and Brugada syndrome (63). This mutation causes an inactivation defect resulting in persistent Na+ current characteristic of most other SCN5A mutations associated with LQTS, but it also confers enhanced slow inactivation with reduced channel availability that is more characteristic of Brugada syndrome (63). The 2 biophysical abnormalities are predicted to predispose to ventricular arrhythmia at extremes of heart rate by different mechanisms (110). Whereas persistent current will prolong the QT interval to a greater degree at slow heart rates, enhanced slow inactivation predisposes myocardial cells to activity-dependent loss of NaVCh availability at fast rates. In another unusual case, deletion of lysine-1500 in SCN5A was associated with the unique combination of LQTS, Brugada syndrome, and impaired conduction in the same family (65). The mutation impairs inactivation, resulting in a persistent Na+ current, and reduces NaVCh availability by opposing shifts in voltage-dependence of inactivation and activation.

Unlike LQTS, Brugada syndrome, and isolated cardiac conduction disease, in which affected individuals are heterozygous for single NaVCh mutations, there are cases in which individuals with severe impairments in cardiac conduction have inherited mutations from both parents. Lupoglazoff et al. described a child homozygous for a missense SCN5A allele (V1777M) who exhibited LQTS with rate-dependent atrioventricular conduction block (86). In a separate report, probands from 3 families exhibited perinatal sinus bradycardia progressing to atrial standstill (congenital sick sinus syndrome) and were found to have compound heterozygosity for mutations in SCN5A (85). Compound heterozygosity in SCN5A has also been observed in 2 infants with neonatal wide complex tachycardia and a generalized cardiac conduction defect (111). In each case of compound heterozygosity, individuals inherited 1 nonfunctional or severely dysfunctional mutation from 1 parent and a second allele with mild biophysical defects from the other parent. Interestingly, the parents who were carriers of single mutations were asymptomatic, which suggests that they had subclinical disease or other host factors affording protection. These unusually severe examples of SCN5A-linked cardiac conduction disorders illustrate the clinical consequence of nearly complete loss of NaVCh function. Complete absence of the murine Scn5a locus results in embryonic lethality (112), and it is likely that homozygous deletion or inactivation of human SCN5A is also not compatible with life.

Treatment strategies for cardiac sodium channelopathies.

Specific therapeutic options for SCN5A-linked disorders are limited. β-Adrenergic blockers remain the first line of therapy in LQTS albeit this treatment strategy may be less efficacious in the setting of SCN5A mutations (113). Clinical and in vitro evidence suggests that mexiletine may counteract the aberrant persistent Na+ current and shorten the QT interval (114, 115) in SCN5A mutation carriers, although there are no data indicating an improvement in mortality. Mexiletine has also been demonstrated to rescue trafficking defective SCN5A mutants in vitro (116). Flecainide has also been observed to shorten QT intervals in the setting of certain SCN5A mutations (117, 118), but some have raised concern over the safety of this therapeutic strategy (119). Class III–type antiarrhythmic agents (quinidine, sotalol) may be beneficial in Brugada syndrome (120, 121). Device therapy (implantable defibrillator for LQTS and Brugada syndrome; pacemaker for conduction disorders) is also an important treatment option.

Neuronal sodium channelopathies

Neuronal NaVChs are critical for the generation and propagation of action potentials in the central and peripheral nervous system. Most of the 13 genes encoding NaVCh α or β subunits are expressed in the brain, peripheral nerves, or both (1). In addition to their critical physiological function, neuronal NaVChs serve as important pharmacological targets for anticonvulsants and local anesthetic agents (122, 123). Their roles in genetic disorders including a variety of inherited epilepsy syndromes and a rare painful neuropathy have been revealed during the past 7 years.

Sodium channels and inherited epilepsies.

Genetic defects in genes encoding 2 pore-forming α subunits (SCN1A and SCN2A) and the accessory β1 subunit (SCN1B) are responsible for a group of epilepsy syndromes with overlapping clinical characteristics but divergent clinical severity (124–129). Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) is usually a benignt disorder characterized by the frequent occurrence of febrile seizures in early childhood that persist beyond age 6 years, and epilepsy later in life associated with afebrile seizures with multiple clinical phenotypes (absence, myoclonic, atonic, myoclonic-astatic). Mutations in 3 neuronal NaVCh genes (SCN1A, SCN1B, and SCN2A) and a GABA receptor subunit (GABRG2) may independently cause GEFS+ or very similar disorders (130, 131). Mutations in SCN2A have also been associated with benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures (BFNIS), a seizure disorder of infancy that remits by age 12 months with no long-term neurological sequelae (129, 132). Interestingly, despite expression of SCN1A and SCN1B in the heart (9), there are no apparent cardiac manifestations associated with these disorders.

By contrast, severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI) and related syndromes have severe neurological sequelae. The diagnosis of SMEI is based on several clinical features, including (a) appearance of seizures, typically generalized tonic-clonic, during the first year of life, (b) impaired psychomotor development following onset of seizures, (c) occurrence of myoclonic seizures, (d) ataxia, and (e) poor response to antiepileptic drugs (133). Two designations, borderline SMEI (SMEB) (133, 134) and intractable childhood epilepsy with frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures (ICEGTC) (128), have been assigned to patients with a condition resembling SMEI but in whom myoclonic seizures are absent and less severe psychomotor impairment is evident. SCN1A mutations have been identified in probands affected by all of these conditions.

More than 100 SCN1A mutations have been identified, with missense mutations being most common in GEFS+ (125, 135–139) and more deleterious alleles (nonsense, frameshift) representing the majority of SMEI mutations (126, 140, 141). Only missense mutations in SCN1A have been reported for patients diagnosed with either ICEGTC or SMEB. There are rare reports of families segregating both GEFS+ and either SMEI or ICEGTC (128). The overlapping phenotypes and molecular genetic etiologies among the SCN1A-linked epilepsies suggest that they represent a continuum of clinical disorders (142).

Sodium channel dysfunction and epileptogenesis.

The first human NaVCh mutation associated with an inherited epilepsy (GEFS+) was discovered in SCN1B encoding the β1 accessory subunit (124). However, mutations in this gene have very rarely been associated with inherited epilepsy. Only 2 SCN1B mutations have been described to date, including a missense allele (C121W) and a 5–amino acid deletion (del70–74) (124, 143). Both mutations occur in an extracellular Ig-fold domain of the β1 subunit that is important for functional modulation of NaVCh α subunits (144, 145) and mediates protein-protein interactions critical for NaVCh subcellular localization in neurons (146). The C121W mutation disrupts a conserved disulfide bridge in this domain, and functional expression studies demonstrated a failure of the mutant to normally modulate the functional properties of recombinant brain NaVChs (124, 147). These findings and the observed seizure disorder in mice with targeted deletion of murine β1 subunit indicate that SCN1B loss of function explains the epilepsy phenotype (148). Functional characterization of the SCN1B deletion allele has not been reported.

Expression studies of α subunit mutations have demonstrated a wide range of functional disturbances. Early findings indicated that SCN1A mutations causing GEFS+ promote a gain of function, while mutations associated with SMEI are predicted to disable channel function. Two studies have demonstrated that increased persistent Na+ current is caused by several GEFS+ mutations (149, 150). This behavior is reminiscent of the channel dysfunction associated with 2 other human sodium channelopathies discussed above, hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and LQTS (Figure 3). Non-inactivating Na+ current may facilitate neuronal hyperexcitability by reducing the threshold for action potential firing. However, not all GEFS+ mutations exhibit increased persistent current. For example, a shift in the voltage-dependence of inactivation to more depolarized potentials has been observed for 2 other GEFS+ mutations (T875M and D1866Y). This functional change is predicted to increase channel availability at voltages near the resting membrane potential and is sufficient to enhance excitability in a simple computational model of a neuronal action potential (150). This may be an oversimplification, as T875M also exhibits enhanced slow inactivation, which is predicted to decrease channel availability. For D1866Y, the changed voltage-dependence of inactivation was attributed to decreased modulation by the β1 subunit, a novel epilepsy-associated mechanism. Other GEFS+ mutations have been described that are nonfunctional (V1353L, A1685V) or exhibit depolarizing shifts in voltage-dependence of activation (I1656M, R1657C) predicted to reduce channel activity (151). These findings indicate that more than 1 biophysical mechanism accounts for seizure susceptibility in GEFS+.

Most SCN1A mutations associated with SMEI are predicted to produce nonfunctional channels by introducing premature termination or frameshifts into the coding sequence. This observation led to the notion that SMEI stems from SCN1A haploinsufficiency. Consistent with this idea was the finding that some missense mutations associated with SMEI are nonfunctional (151, 152). However, a simple dichotomy of gain versus loss of function to explain clinical differences between GEFS+ and SMEI is not consistent with recent observations. As mentioned above, some GEFS+ mutations exhibit loss-of-function characteristics. More recently, 2 SMEI missense alleles (R1648C and F1661S) were demonstrated to encode functional channels that exhibit a mixed pattern of biophysical defects consistent with either gain (persistent Na+ current) or loss (reduced channel density, altered voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation) of function (152). The precise cellular mechanism by which this constellation of biophysical disturbances leads to epilepsy is uncertain and motivates further experiments in animal models to help determine the impact of NaVCh mutations.

SCN9A and painful inherited neuropathy.

Mutations in another neuronal NaVCh gene, SCN9A, encoding an α subunit isoform expressed in sensory and sympathetic neurons, have been discovered in patients with familial primary erythermalgia, a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of severe pain, redness, and warmth in the distal extremities. Two missense SCN9A mutations were recently identified in Chinese patients (153). Both mutations cause a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage-dependence of channel activation and slow the rate of deactivation (154). This combination of biophysical defects is predicted to confer hyperexcitability on peripheral sensory and sympathetic neurons, accounting for the episodic pain and vasomotor symptoms characteristic of the disease. Consistent with overactive NaVChs are anecdotal reports of improved symptoms during treatment with local anesthetic agents (i.e., lidocaine, bupivacaine) or mexiletine (155–157).

Summary and future challenges

NaVChs are important from many perspectives. Their recognized importance in the physiology and pharmacology of nerve, muscle, and heart is now further emphasized by their role in inherited disorders affecting these tissues. The sodium channelopathies provide outstanding illustrations of the delicate balances that maintain normal operation of critical physiological events such as muscle contraction and conduction of electrical signals.

Despite the extensive array of disorders listed in Table 1, it is likely that other inherited or pharmacogenetic disorders are caused by mutations or polymorphisms in NaVCh genes. Only 6 of the 13 known genes encoding NaVCh subunits have been linked to human disease. However, spontaneous or engineered disruption of 2 other genes (Scn8a and Scn2b) causes neurological phenotypes in mice (158–160), suggesting that other human sodium channelopathies might exist. Establishing new genotype-phenotype relationships, exploring pathophysiology, and developing new treatment strategies remain exciting challenges for the future.

Acknowledgments

The author is supported by grants from the NIH (NS32387 and HL68880) and is the recipient of a Javits Neuroscience Award from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: GEFS+, generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus; ICEGTC, intractable childhood epilepsy with frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures; LQTS, long QT syndrome; NaVCh, voltage-gated sodium channel; SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome; SMEB, borderline severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy; SMEI, severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy; SUDS, sudden unexplained death syndrome.

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Catterall WA. Cellular and molecular biology of voltage-gated sodium channels [review] Physiol. Rev. 1992;72(Suppl. 4):S15–S48. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitaker WR, et al. Distribution of voltage-gated sodium channel alpha-subunit and beta-subunit mRNAs in human hippocampal formation, cortex, and cerebellum. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;422:123–139. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000619)422:1<123::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trimmer JS, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of a mammalian skeletal muscle sodium channel. Neuron. 1989;3:33–49. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George AL, Komisarof J, Kallen RG, Barchi RL. Primary structure of the adult human skeletal muscle voltage-dependent sodium channel. Ann. Neurol. 1992;31:131–137. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogart RB, Cribbs LL, Muglia LK, Kephart DD, Kaiser MW. Molecular cloning of a putative tetrodotoxin-resistant rat heart Na+ channel isoform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:8170–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gellens ME, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of the human cardiac tetrodotoxin-insensitive voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:554–558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maier SK, et al. An unexpected requirement for brain-type sodium channels for control of heart rate in the mouse sinoatrial node. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:3507–3512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627986100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maier SKG, et al. An unexpected role for brain-type sodium channels in coupling of cell surface depolarization to contraction in the heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:4073–4078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261705699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stühmer W, et al. Structural parts involved in activation and inactivation of the sodium channel. Nature. 1989;339:597–603. doi: 10.1038/339597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang NB, George AL, Jr, Horn R. Molecular basis of charge movement in voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 1996;16:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren D, et al. A prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel. Science. 2001;294:2372–2375. doi: 10.1126/science.1065635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. Currents carried by sodium and potassium ion through the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J. Physiol. 1952;116:449–472. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo CC, Bean BP. Na+ channels must deactivate to recover from inactivation. Neuron. 1994;12:819–829. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilin YY, Ruben PC. Slow inactivation in voltage-gated sodium channels: molecular substrates and contributions to channelopathies. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2001;35:171–190. doi: 10.1385/CBB:35:2:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon, S.C., and George, A.L. 2002. Pathophysiology of myotonia and periodic paralysis. In Diseases of the nervous system: clinical neuroscience and therapeutic principles. A.K. Asbury, G.M. Mckhann, W.I. McDonald, P.J. Goadsby, and J.C. McArthur, editors. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, United Kingdom. 1183–1206.

- 17.Griggs RC. The myotonic disorders and the periodic paralyses. Adv. Neurol. 1977;17:143–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streib EW. Differential diagnosis of myotonic syndromes. Muscle Nerve. 1987;10:603–615. doi: 10.1002/mus.880100704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rüdel R, Ricker K, Lehmann-Horn F. Genotype-phenotype correlations in human skeletal muscle sodium channel diseases. Arch. Neurol. 1993;50:1241–1248. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540110113011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ptacek LJ, et al. Identification of a mutation in the gene causing hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Cell. 1991;67:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rüdel R, Lehmann-Horn F. Membrane changes in cells from myotonia patients. Physiol. Rev. 1985;65:310–356. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1985.65.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontaine B, et al. Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and the adult muscle sodium channel alpha subunit gene. Science. 1990;250:1000–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.2173143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ptacek LJ, et al. Paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis map to the same sodium channel gene locus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1991;49:851–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebers GC, et al. Paramyotonia congenita and non-myotonic hyperkalemic periodic paralysis are linked to the adult muscle sodium channel gene. Ann. Neurol. 1991;30:810–816. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rojas CV, et al. A Met-to-Val mutation in the skeletal muscle Na+ channel α-subunit in hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Nature. 1991;354:387–389. doi: 10.1038/354387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClatchey AI, et al. Temperature-sensitive mutations in the III-IV cytoplasmic loop region of the skeletal muscle sodium channel gene in paramyotonia congenita. Cell. 1992;68:769–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ptacek LJ, et al. Mutations in an S4 segment of the adult skeletal muscle sodium channel gene cause paramyotonia congenita. Neuron. 1992;8:891–897. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90203-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ptacek LJ, et al. Sodium channel mutations in paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33:300–307. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ptacek LJ, et al. Sodium channel mutations in acetazolamide-responsive myotonia congenita, paramyotonia congenita, and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Neurology. 1994;44:1500–1503. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.8.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lerche H, et al. Human sodium channel myotonia: slowed channel inactivation due to substitutions for a glycine within the III/IV linker. J. Physiol. 1993;470:13–22. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerche H, Mitrovic N, Dubowitz V, Lehmann-Horn F. Paramyotonia congenita: the R1448P Na+ channel mutation in adult human skeletal muscle. Ann. Neurol. 1996;39:599–608. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricker K, Moxley RT, III, Heine R, Lehmann-Horn F. Myotonia fluctuans. A third type of muscle sodium channel disease. Arch. Neurol. 1994;51:1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540230033009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller TM, et al. Correlating phenotype and genotype in the periodic paralyses. Neurology. 2004;63:1647–1655. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000143383.91137.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vita GM, et al. Masseter muscle rigidity associated with glycine-1306 to alanine mutation in the adult muscle sodium channel α-subunit gene. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:1097–1103. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bendahhou S, et al. A double mutation in families with periodic paralysis defines new aspects of sodium channel slow inactivation. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:431–438. doi: 10.1172/JCI9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsujino A, et al. Myasthenic syndrome caused by mutation of the SCN4A sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:7377–7382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230273100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannon SC, Brown RH, Corey DP. A sodium channel defect in hyperkalemic periodic paralysis: potassium induced failure of inactivation. Neuron. 1991;6:619–626. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannon SC, Strittmatter SM. Functional expression of sodium channel mutations identified in families with periodic paralysis. Neuron. 1993;10:317–326. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90321-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehmann-Horn F, et al. Two cases of adynamia episodica hereditaria: in vitro investigation of muscle cell membrane and contraction parameters. Muscle Nerve. 1983;6:113–121. doi: 10.1002/mus.880060206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rüdel R, Lehmann-Horn F, Ricker K, Kuther G. Hypokalemic periodic paralysis: in vitro investigation of muscle fiber membrane parameters. Muscle Nerve. 1984;7:110–120. doi: 10.1002/mus.880070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummins TR, Sigworth FJ. Impaired slow inactivation in mutant sodium channels. Biophys. J. 1996;71:227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruff RL. Slow Na+ sodium channel inactivation must be disrupted to evoke prolonged depolarization-induced paralysis. Biophys. J. 1994;66:542–545. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80807-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang N, et al. Sodium channel mutations in paramyotonia congenita exhibit similar biophysical phenotypes in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:12785–12789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitrovic N, George AL, Jr, Rudel R, Lehmann-Horn F, Lerche H. Mutant channels contribute <50% to Na+ current in paramyotonia congenita muscle. Brain. 1999;122:1085–1092. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.6.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitrovic N, et al. K+-aggravated myotonia: destabilization of the inactivated state of the human muscle Na+ channel by the V1589M mutation. J. Physiol. 1994;478:395–402. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitrovic N, et al. Different effects on gating of three myotonia-causing mutations in the inactivation gate of the human muscle sodium channel. J. Physiol. 1995;487:107–114. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Jr, Cannon SC. Inactivation defects caused by myotonia-associated mutations in the sodium channel III-IV linker. J. Gen. Physiol. 1996;107:559–576. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cannon SC. From mutation to myotonia in sodium channel disorders. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1997;7:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(97)00430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adrian RH, Bryant SH. On the repetitive discharge in myotonic muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1974;240:505–515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moxley RT., III Channelopathies. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2000;2:31–47. doi: 10.1007/s11940-000-0022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meola G, Sansone V. Therapy in myotonic disorders and in muscle channelopathies [review] Neurol. Sci. 2000;21(Suppl. 5):S953–S961. doi: 10.1007/s100720070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackson CE, Barohn RJ, Ptacek LJ. Paramyotonia congenita: abnormal short exercise test, and improvement after mexiletine therapy. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:763–768. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwiecinski H, Ryniewicz B, Ostrzycki A. Treatment of myotonia with antiarrhythmic drugs. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1992;86:371–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb05103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi MP, Cannon SC. Mexiletine block of disease-associated mutations in S6 segments of the human skeletal muscle Na+ channel. J. Physiol. 2001;537:701–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosenfeld J, Sloan-Brown K, George AL., Jr A novel muscle sodium channel mutation causes painful congenital myotonia. Ann. Neurol. 1997;42:811–814. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Desaphy JF, De Luca A, Didonna MP, George AL, Conte CD. Different flecainide sensitivity of hNaV1.4 channels and myotonic mutants explained by state-dependent block. J. Physiol. 2003;554:321–334. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Q, et al. SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Q, et al. Cardiac sodium channel mutations in patients with long QT syndrome, an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:1603–1607. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.9.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Q, et al. Genetic basis and molecular mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:293–296. doi: 10.1038/32675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schott JJ, et al. Cardiac conduction defects associate with mutations in SCN5A. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:20–21. doi: 10.1038/12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan HL, et al. A sodium-channel mutation causes isolated cardiac conduction disease. Nature. 2001;409:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/35059090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang DW, Viswanathan PC, Balser JR, George AL, Jr, Benson DW. Clinical, genetic, and biophysical characterization of SCN5A mutations associated with atrioventricular conduction block. Circulation. 2002;105:341–346. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bezzina C, et al. A single Na+ channel mutation causing both long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circ. Res. 1999;85:1206–1213. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McNair WP, et al. SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia. Circulation. 2004;110:2163–2167. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144458.58660.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grant AO, et al. Long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and conduction system disease are linked to a single sodium channel mutation. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1201–1209. doi:10.1172/JCI200215570. doi: 10.1172/JCI15570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Makita N, et al. Drug-induced long-QT syndrome associated with a subclinical SCN5A mutation. Circulation. 2002;106:1269–1274. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027139.42087.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwartz PJ, et al. A molecular link between the sudden infant death syndrome and the long-QT syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:262–267. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ackerman MJ, et al. Postmortem molecular analysis of SCN5A defects in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA. 2001;286:2264–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Splawski I, et al. Variant of SCN5A sodium channel implicated in risk of cardiac arrhythmia. Science. 2002;297:1333–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1073569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keating MT. The long QT syndrome. A review of recent molecular genetic and physiologic discoveries [review] Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vincent GM. The molecular genetics of the long QT syndrome: genes causing fainting and sudden death. Annu. Rev. Med. 1998;49:263–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Curran ME, et al. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Q, et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat. Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwartz PJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001;103:89–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schwartz PJ, et al. Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to Na+ channel blockade and to increases in heart rate. Implications for gene-specific therapy. Circulation. 1995;92:3381–3386. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akai J, et al. A novel SCN5A mutation associated with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation without typical ECG findings of Brugada syndrome. FEBS Lett. 2000;479:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vatta M, et al. Genetic and biophysical basis of sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), a disease allelic to Brugada syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:337–345. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sangwatanaroj S, Yanatasneejit P, Sunsaneewitayakul B, Sitthisook S. Linkage analyses and SCN5A mutations screening in five sudden unexplained death syndrome (Lai-tai) families. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2002;85(Suppl. 1):S54–S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brugada J, Brugada P. Further characterization of the syndrome of right bundle branch block, ST segment elevation, and sudden cardiac death. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1997;8:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1997.tb00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brugada R, et al. Sodium channel blockers identify risk for sudden death in patients with ST-segment elevation and right bundle branch block but structurally normal hearts. Circulation. 2000;101:510–515. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baron RC, et al. Sudden death among Southeast Asian refugees. An unexplained nocturnal phenomenon. JAMA. 1983;250:2947–2951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nademanee K, et al. Arrhythmogenic marker for the sudden unexplained death syndrome in Thai men. Circulation. 1997;96:2595–2600. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sangwatanaroj S, Ngamchareon C, Prechawat S. Pattern of inheritance in three sudden unexplained death syndrome (“Lai-tai”) families. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2001;84(Suppl. 1):S443–S451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Groenewegen WA, et al. A cardiac sodium channel mutation cosegregates with a rare connexin40 genotype in familial atrial standstill. Circ. Res. 2003;92:14–22. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000050585.07097.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benson DW, et al. Congenital sick sinus syndrome caused by recessive mutations in the cardiac sodium channel gene (SCN5A) J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1019–1028. doi:10.1172/JCI200318062. doi: 10.1172/JCI18062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lupoglazoff JM, et al. Homozygous SCN5A mutation in long-QT syndrome with functional two-to-one atrioventricular block. Circ. Res. 2001;89:E16–E21. doi: 10.1161/hh1401.095087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chang CC, et al. A novel SCN5A mutation manifests as a malignant form of long QT syndrome with perinatal onset of tachycardia/bradycardia. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;64:268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kyndt F, et al. Novel SCN5A mutation leading either to isolated cardiac conduction defect or Brugada syndrome in a large French family. Circulation. 2001;104:3081–3086. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.100834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olson TM, et al. Sodium channel mutations and susceptibility to heart failure and atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2005;293:447–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Makita N, George AL., Jr Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995;376:683–685. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dumaine R, et al. Multiple mechanisms of Na+ channel-linked long-QT syndrome. Circ. Res. 1996;78:916–924. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang DW, Yazawa K, George AL, Jr, Bennett PB. Characterization of human cardiac Na+ channel mutations in the congenital long QT syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:13200–13205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kambouris NG, et al. Phenotypic characterization of a novel long-QT syndrome mutation (R1623Q) in the cardiac sodium channel. Circulation. 1998;97:640–644. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abriel H, et al. Novel arrhythmogenic mechanism revealed by a long-QT syndrome mutation in the cardiac Na+ channel. Circ. Res. 2001;88:740–745. doi: 10.1161/hh0701.089668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1999;400:566–569. doi: 10.1038/23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Antzelevitch C, Yan GX, Shimizu W. Transmural dispersion of repolarization and arrhythmogenicity: the Brugada syndrome versus the long QT syndrome [review] J. Electrocardiol. 1999;32(Suppl.):158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(99)90074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nuyens D, et al. Abrupt rate accelerations or premature beats cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mice with long-QT3 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1021–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST-segment elevation. Circulation. 1999;100:1660–1666. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.15.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Antzelevitch C. Ion channels and ventricular arrhythmias: cellular and ionic mechanisms underlying the Brugada syndrome. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 1999;14:274–279. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schulze-Bahr E, et al. Sodium channel gene (SCN5A) mutations in 44 index patients with Brugada syndrome: different incidences in familial and sporadic disease. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:651–652. doi: 10.1002/humu.9144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Baroudi G, Acharfi S, Larouche C, Chahine M. Expression and intracellular localization of an SCN5A double mutant R1232W/T1620M implicated in Brugada syndrome. Circ. Res. 2002;90:E11–E16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baroudi G, et al. Novel mechanism for Brugada syndrome: defective surface localization of an SCN5A mutant (R1432G) Circ. Res. 2001;88:E78–E83. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.093270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Baroudi G, Napolitano C, Priori SG, Del Bufalo A, Chahine M. Loss of function associated with novel mutations of the SCN5A gene in patients with Brugada syndrome. Can. J. Cardiol. 2004;20:425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Valdivia CR, et al. A trafficking defective, Brugada syndrome-causing SCN5A mutation rescued by drugs. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;62:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dumaine R, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ. Res. 1999;85:803–809. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.9.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang DW, Makita N, Kitabatake A, Balser JR, George AL., Jr Enhanced Na+ channel intermediate inactivation in Brugada syndrome. Circ. Res. 2000;87:E37–E43. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rook MB, et al. Human SCN5A gene mutations alter cardiac sodium channel kinetics and are associated with the Brugada syndrome. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;44:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Herfst LJ, et al. Na+ channel mutation leading to loss of function and non-progressive cardiac conduction defects. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003;35:549–557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Probst V, et al. Haploinsufficiency in combination with aging causes SCN5A-linked hereditary Lenegre disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;41:643–652. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Na(+) channel mutation that causes both Brugada and long-QT syndrome phenotypes: a simulation study of mechanism. Circulation. 2002;105:1208–1213. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bezzina CR, et al. Compound heterozygosity for mutations (W156X and R225W) in SCN5A associated with severe cardiac conduction disturbances and degenerative changes in the conduction system. Circ. Res. 2003;92:159–168. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000052672.97759.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Papadatos GA, et al. Slowed conduction and ventricular tachycardia after targeted disruption of the cardiac sodium channel gene Scn5a. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:6210–6215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082121299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Priori SG, et al. Association of long QT syndrome loci and cardiac events among patients treated with beta-blockers. JAMA. 2004;292:1341–1344. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schwartz PJ, et al. Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to Na+ channel blockade and to increases in heart rate. Implications for gene-specific therapy. Circulation. 1995;92:3381–3386. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang DW, Yazawa K, Makita N, George AL, Jr, Bennett PB. Pharmacological targeting of long QT mutant sodium channels. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1714–1720. doi: 10.1172/JCI119335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Valdivia CR, et al. A novel SCN5A arrhythmia mutation, M1766L, with expression defect rescued by mexiletine. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002;55:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Windle JR, Geletka RC, Moss AJ, Zareba W, Atkins DL. Normalization of ventricular repolarization with flecainide in long QT syndrome patients with SCN5A:DeltaKPQ mutation. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2001;6:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2001.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Abriel H, Wehrens XH, Benhorin J, Kerem B, Kass RS. Molecular pharmacology of the sodium channel mutation D1790G linked to the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2000;102:921–925. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Priori SG, et al. The elusive link between LQT3 and Brugada syndrome: the role of flecainide challenge. Circulation. 2000;102:945–947. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Belhassen B, Glick A, Viskin S. Efficacy of quinidine in high-risk patients with Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2004;110:1731–1737. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143159.30585.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Glatter KA, et al. Effectiveness of sotalol treatment in symptomatic Brugada syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004;93:1320–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Macdonald RL, Greenfield LJ., Jr Mechanisms of action of new antiepileptic drugs. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1997;10:121–128. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Catterall WA. Molecular properties of brain sodium channels: an important target for anticonvulsant drugs. Adv. Neurol. 1999;79:441–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wallace RH, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel β1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:366–370. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Escayg A, et al. Mutations of SCN1A, encoding a neuronal sodium channel, in two families with GEFS+2. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:343–345. doi: 10.1038/74159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Claes L, et al. De novo mutations in the sodium-channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:1327–1332. doi: 10.1086/320609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sugawara T, et al. A missense mutation of the Na+ channel αII subunit gene Nav1.2 in a patient with febrile and afebrile seizures causes channel dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:6384–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111065098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fujiwara T, et al. Mutations of sodium channel alpha subunit type 1 (SCN1A) in intractable childhood epilepsies with frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Brain. 2003;126:531–546. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Heron SE, et al. Sodium-channel defects in benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures. Lancet. 2002;360:851–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baulac S, et al. First genetic evidence of GABAA receptor dysfunction in epilepsy: a mutation in the γ2-subunit gene. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:46–48. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wallace RH, et al. Mutant GABAA receptor γ2-subunit in childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:49–52. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Berkovic SF, et al. Benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures: characterization of a new sodium channelopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:550–557. doi: 10.1002/ana.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ohmori I, et al. Is phenotype difference in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy related to SCN1A mutations? Brain Dev. 2003;25:488–493. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fukuma G, et al. Mutations of neuronal voltage-gated Na+ channel α1 subunit gene SCN1A in core severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI) and in borderline SMEI (SMEB) Epilepsia. 2004;45:140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.15103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Escayg A, et al. A novel SCN1A mutation associated with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus — and prevalence of variants in patients with epilepsy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:866–873. doi: 10.1086/319524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wallace RH, et al. Neuronal sodium-channel α1-subunit mutations in generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:859–865. doi: 10.1086/319516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Abou-Khalil B, et al. Partial epilepsy and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus and a novel SCN1A mutation. Neurology. 2001;57:2265–2272. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sugawara T, et al. Nav1.1 mutations cause febrile seizures associated with afebrile partial seizures. Neurology. 2001;57:703–705. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ito M, et al. Autosomal dominant epilepsy with febrile seizures plus with missense mutations of the Na+-channel α1 subunit gene, SCN1A. Epilepsy Res. 2002;48:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ohmori I, Ouchida M, Ohtsuka Y, Oka E, Shimizu K. Significant correlation of the SCN1A mutations and severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;295:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sugawara T, et al. Frequent mutations of SCN1A in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Neurology. 2002;58:1122–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.7.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Singh R, et al. Severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy: extended spectrum of GEFS+? Epilepsia. 2001;42:837–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042007837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Audenaert D, et al. A deletion in SCN1B is associated with febrile seizures and early-onset absence epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;61:854–856. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000080362.55784.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Makita N, Bennett PB, George AL., Jr Molecular determinants of β1 subunit-induced gating modulation in voltage-dependent Na+ channels. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:7117–7127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07117.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.McCormick KA, et al. Molecular determinants of Na+ channel function in the extracellular domain of the β1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3954–3962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.McEwen DP, Meadows LS, Chen C, Thyagarajan V, Isom LL. Sodium channel β1 subunit-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 currents and cell surface density is dependent on interactions with contactin and ankyrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16044–16049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Meadows LS, et al. Functional and biochemical analysis of a sodium channel β1 subunit mutation responsible for generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus type 1. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10699–10709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10699.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chen C, et al. Mice lacking sodium channel β1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4030–4042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4139-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Lossin C, Wang DW, Rhodes TH, Vanoye CG, George AL., Jr Molecular basis of an inherited epilepsy. Neuron. 2002;34:877–884. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Spampanato J, et al. A novel epilepsy mutation in the sodium channel SCN1A identifies a cytoplasmic domain for beta subunit interaction. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10022–10034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lossin C, et al. Epilepsy-associated dysfunction in the voltage-gated neuronal sodium channel SCN1A. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:11289–11295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11289.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Rhodes TH, Lossin C, Vanoye CG, Wang DW, George AL., Jr Noninactivating voltage-gated sodium channels in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:11147–11152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402482101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Yang Y, et al. Mutations in SCN9A, encoding a sodium channel alpha subunit, in patients with primary erythermalgia. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:171–174. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.012153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Electrophysiological properties of mutant Nav1.7 sodium channels in a painful inherited neuropathy. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8232–8236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2695-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Jang HS, et al. A case of primary erythromelalgia improved by mexiletine. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004;151:708–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Legroux-Crespel E, et al. Treatment of familial erythermalgia with the association of lidocaine and mexiletine. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2003;130:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Stricker LJ, Green CR. Resolution of refractory symptoms of secondary erythermalgia with intermittent epidural bupivacaine. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2001;26:488–490. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2001.25930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Buchner DA, Seburn KL, Frankel WN, Meisler MH. Three ENU-induced neurological mutations in the pore loop of sodium channel Scn8a Nav1.6 and a genetically linked retinal mutation, rd13. Mamm. Genome. 2004;15:344–351. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Kohrman DC, Smith MR, Goldin AL, Harris J, Meisler MH. A missense mutation in the sodium channel Scn8a is responsible for cerebellar ataxia in the mouse mutant jolting. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5993–5999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-05993.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Chen C, et al. Reduced sodium channel density, altered voltage dependence of inactivation, and increased susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking sodium channel β2-subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:17072–17077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212638099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]