Abstract

Dacomitinib demonstrated superior survival benefit compared to gefitinib as a first-line treatment in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with common EGFR mutations through ARCHER 1050. However, there is limited real-world data concerning its efficacy and safety. This study included patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who received dacomitinib as a first-line treatment between January 2021 and December 2022 at Samsung Medical Center and St. Vincent’s Hospital. This study assessed the objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), safety profile of dacomitinib, and subsequent treatments after dacomitinib failure. In total, 153 patients were included in this study. Exon 19 deletion was observed in 50.3% of patients, while the L858R mutation in exon 21 was observed in 46.4% of patients. 45.1% of patients had brain metastasis. The ORR was 84.3%. The median follow-up duration was 16.9 months, with a median PFS of 16.7 months (95% CI, 14.4 to 25.2). Based on the type of EGFR mutation, the median PFS was 18.1 months (95% CI, 14.5 to NE) in patients with exon 19 deletion, and 15.9 months (95% CI, 12.5 to NE) in patients with L858R mutation. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were observed in 7.2% of patients. Initially administered at a dose of 45 mg, dose reduction was necessary for 85.6% of patients, with a final dosage of 30 mg in 49.0% and 15 mg in 36.6% of cases. Out of the 60 patients who experienced disease progression, 31 underwent tissue re-biopsy and 25 underwent liquid biopsy. Overall, T790M mutation was detected in 40.9% of patients who progressed after dacomitinib. The survival benefit of dacomitinib has been demonstrated, indicating its promising efficacy in a real-world setting. The detection rate of the T790M mutation after dacomitinib treatment failure was comparable to that of other second-generation EGFR-TKIs.

Keywords: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Dacomitinib, Real-world data

Subject terms: Lung cancer, Cancer therapy

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death1, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) constituting nearly 85% of newly diagnosed cases. Over the last decade, significant progress has occurred in the understanding of NSCLC. Targeted therapy has notably enhanced clinical outcomes for a considerable portion of advanced/metastatic NSCLC patients possessing actionable genetic alterations, particularly Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) mutations2. Among these, EGFR mutation is the most common targetable driver mutation in lung cancer, appearing in 17-61% of NSCLC adenocarcinomas, with higher frequencies observed in Asian, female, and never-smoker patients3. The most common EGFR mutations include exon 19 deletion and L858R mutation in exon 21 and are observed in 80–90% of cases4. First-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as erlotinib and gefitinib, and second-generation TKIs like afatinib and dacomitinib have previously demonstrated clinical superiority over platinum-based chemotherapy5–8. Recently, osimertinib (third-generation EGFR-TKI) has emerged as the preferred first-line option, showing enhanced survival benefits compared with first-generation EGFR-TKIs9.

Dacomitinib is an orally administered, small-molecule irreversible TKI that targets HER1 (EGFR), HER2, and HER410. Two distinguishing features of this second-generation EGFR TKI, which distinguish them from first-generation EGFR TKIs, are their irreversible mode of binding and their broader activity against HER family members11. ARCHER 1050 aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of dacomitinib with gefitinib (first-generation EGFR-TKI) for the first-line treatment of locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC with common EGFR mutations. Dacomitinib demonstrates superior efficacy in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to gefitinib with a median PFS of 14.7 months versus 9.2 months (hazard ratio 0.59, p < 0.0001) and a median OS of 34.1 months versus 26.8 months (hazard ratio 0.76, p = 0.044)8.

Based on the result of ARCHER 1050, dacomitinib obtained FDA approval as a first-line treatment for patients with metastatic NSCLC with EGFR exon 19 deletion or L858R mutation in exon 21. However, there is relatively limited real-world data available regarding its efficacy and safety. In particular, a significant limitation of ARCHER 1050 is the exclusion of patients with brain metastasis, which results in a gap in the evidence concerning survival benefits in this subgroup of patients. Hence, real-world data are required to address this issue. Furthermore, there is limited understanding of acquired resistance mechanism and available subsequent treatment options when the disease progresses following dacomitinib as a first-line treatment in the clinical setting.

This multi-center retrospective study aims to clarify the efficacy and safety of dacomitinib as a first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Additionally, it explores subsequent treatment strategies following dacomitinib failure in a real-world setting.

Results

Study population and clinical characteristics

Between January 6th, 2021, and December 9th, 2022, 153 patients received dacomitinib as a first-line treatment. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study population. The median age at diagnosis was 64.6 years. Among total, 60.8% were female, and 68.6% were never-smokers. One hundred and forty-seven patients (96.1%) had adenocarcinoma, while 6 patients had other pathologies. Ninety-nine patients (64.7%) were diagnosed with stage IV at the time of diagnosis, with 47 patients (30.7%) undergoing surgery and 10 patients (6.5%) receiving definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and experiencing progression to primary therapy. Exon 19 deletions were observed in 77 patients (50.3%), and 71 (46.4%) had L858R mutations in exon 21.

Table 1.

Baseline chacteristics.

| Patient characteristics | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 64.6 (54.5–74.7) |

| < 65 years | 79 (51.6%) |

| ≥ 65 years | 74 (48.4%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 60 (39.2%) |

| Female | 93 (60.8%) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 47 (30.7%) |

| 1 | 100 (65.4%) |

| ≥ 2 | 6 (4.0%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoker | 105 (68.6%) |

| Current or Ex-smoker | 48 (31.4%) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 147 (96.1%) |

| Squamous | 3 (2.0%) |

| Othersa | 3 (2.0%) |

| Stage at initial diagnosis | |

| I | 23 (15.0%) |

| II | 12 (7.9%) |

| III | 19 (12.4%) |

| IV | 99 (64.7%) |

| Previous history of treatments | |

| Curative surgery | 47 (30.7%) |

| Definitive CCRT | 10 (6.5%) |

| Type of EGFR mutation | |

| Exon 19 deletion | 77 (50.3%) |

| L858R mutation in exon 21 | 71 (46.4%) |

| Othersb | 5 (3.3%) |

| Distant metastasis at initiation of dacomitinib | |

| Brain | 69 (45.1%) |

| Bone | 56 (36.6%) |

| Pleura | 45 (29.4%) |

| Adrenal gland | 10 (6.5%) |

| Liver | 7 (4.6%) |

aThe histology of the 3 patients were adeno-squamous. bThe EGFR mutation status of patients categorized under others is as follows: L861Q mutation in exon 21, Exon 20 insertion, G719X mutation in exon 18, G719X mutation in exon 18 and S768I mutation in exon 20, G719X mutation in exon 18 and L861Q mutation in exon 21. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; CCRT, concurrent chemo-radiotherapy.

At the initiation of dacomitinib, 69 patients (45.1%) presented with concurrent brain metastasis, while bone metastasis, pleural metastasis, liver metastasis, and adrenal metastasis were observed in 56 (36.6%), 45 (29.4%), 10 (6.5%), and 7 (4.6%) patients, respectively.

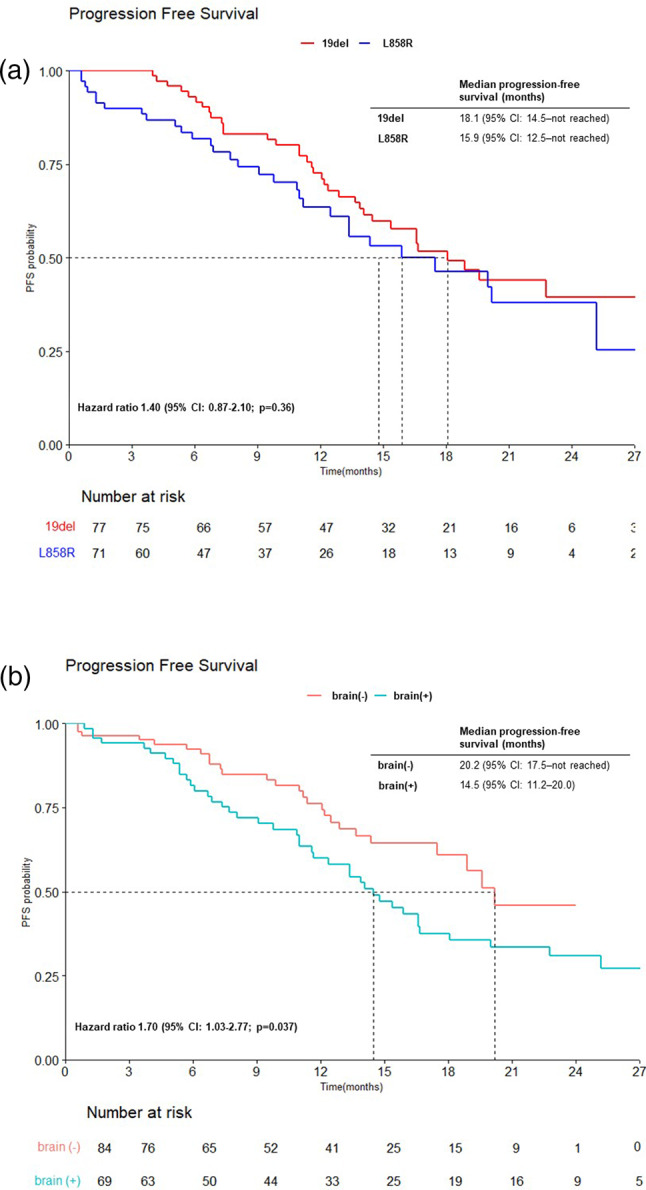

Efficacy of dacomitinib

The data lock was performed on April 30th, 2023. At the time of data lock, with 16.9 months of median follow-up duration (range: 5.9–27.9), 67 patients experienced a PFS event, while 73 patients continued dacomitinib. The median number of cycles of dacomitinib was 13 (range: 2–24). Out of the 153 patients receiving dacomitinib, one patient achieved CR (0.7%), while 128 achieved PR (83.7%), resulting in an ORR of 84.3% (Table 2). The median PFS was 16.7 months (95% CI; 14.4–25.2) in total population (Fig. 1A). The median OS was not reached, with a 24-month OS rate of 83.9% (Fig. 1B). Among patients with exon 19 deletion, the median PFS was 18.1 months (95% CI: 14.5–not reached), while among those with the L858R mutation in exon 21, the median PFS was 15.9 months (95% CI: 12.5–not reached) (Fig. 2A). Among patients with brain metastasis, the median PFS was 14.5 months (95% CI: 11.2–20.0), whereas the median PFS was 20.2 months in those without brain metastasis (95% CI: 17.5–not reached), indicating a longer PFS in the absence of brain metastasis (p = 0.037) (Fig. 2B).

Table 2.

Objective response to dacomitinib.

| Treatment response | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| No. of cycles, median (range) | 13 (2–24) |

| Complete response | 1 (0.7%) |

| Partial response | 128 (83.7%) |

| Stable disease | 11 (7.2%) |

| Progressive disease | 6 (3.9%) |

| Unknown | 7 (4.6%) |

| Overall objective response rate | 129 (84.3%) |

| Overall disease control rate | 140 (91.5%) |

| Proportion overall PFS at 12 months | 48.4% |

PFS, progression-free survival.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival according to (A) the type of EGFR mutation (exon19 deletion and L858R mutation in exon 21) and (B) the presence of brain metastasis.

Safety profile

Out of the total 153 patients, 94.1% reported at least one adverse event, while 11 patients (7.2%) reported adverse events of grade 3 or higher. Grade 4 adverse event was not reported. The most commonly reported adverse events were rash, diarrhea, and mucositis (51.0%, 49.0%, and 40.5% respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse events and dose reduction of dacomitinib.

| Adverse events | Any grade | Grade ≥ 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 75 (49.0%) | 3 (2.0%) |

| Paronychia | 60 (39.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Dermatitis | 45 (29.4%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Rash | 78 (51.0%) | 7 (4.6%) |

| Oral mucositis | 62 (40.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Nausea | 3 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Fatigue | 6 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Increased AST/ALT | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Final reduced dose owing to adverse events | ||

| No dose reduction | 22 (14.4%) | |

| Dose reduction | 131 (85.6%) | |

| 30 mg per day | 75 (49.0%) | |

| 15 mg per day | 56 (36.6%) | |

| Permanent discontinuation | 13 (8.5%) | |

| Temporary interruption | 37 (24.2%) | |

One hundred and fifty patients started on a once-daily dose of 45 mg of dacomitinib, while three patients started dacomitinib with a dosage of 30 mg. Dose reductions owing to adverse events occurred in 131 (85.6%) patients. The lowest dacomitinib dose was 30 mg once daily in 75 patients (49.0%) and 15 mg once daily in 56 patients (36.6%). Moreover, it took a median time of 1.2 months to achieve a dose reduction of 30 mg, and 4.3 months to 15 mg. Temporary dose interruptions occurred in 37 (24.2%) patients. Thirteen patients (8.5%) permanently discontinued dacomitinib and changed to other EGFR-TKI owing to intolerable adverse events.

Subsequential treatment after dacomitinib

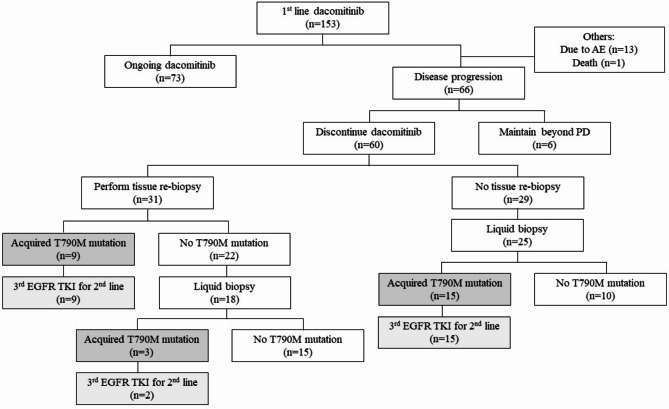

Figure 3 summarizes the subsequent treatments of patients after dacomitinib as a first-line treatment. Seventy-three patients continued dacomitinib without evidence of disease progression, while 14 patients discontinued dacomitinib for reasons other than disease progression. Among 66 patients who experienced disease progression while on dacomitinib, 22 patients (33.3%) continued dacomitinib under the concept of beyond progression. Among them, lesions associated with disease progression occurred in the brain, bone, and lung in 11, 9, and 3 patients, respectively. Among 11 patients with intracranial progression, 8 patients underwent gamma-knife radiosurgery for the corresponding lesions. At the time of data lock, 6 patients continued dacomitinib beyond disease progression.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of subsequent treatments.

Thirty-one patients underwent tissue re-biopsy to confirm the acquired resistance mechanism of dacomitinib. Among the 29 patients who did not undergo tissue re-biopsy, 25 underwent liquid biopsy. Of the 56 patients who underwent either tissue or liquid re-biopsy, 27 were found to have the EGFR T790M mutation in exon 20 (T790M). Except for one patient, all switched to third-generation EGFR TKIs, with 11 switching to osimertinib and 15 to lazertinib. Among the 29 patients without the T790M mutation, three were enrolled in a clinical trial for further treatment and are still under observation, while 16 patients received platinum-based cytotoxic chemotherapy (14 received pemetrexed/carboplatin and 2 received gemcitabine/carboplatin). Others refused further treatment due to poor performance status or were transferred to another hospital.

Overall, T790M was detected in 40.9% of patients who progressed from dacomitinib. In patients who underwent tissue re-biopsy, additional examinations were conducted to identify other resistance mechanisms beyond T790M. C-MET expression was assessed through immunohistochemistry staining using re-biopsy tissue, with positive results observed in 7 patients. No histological transformation to small-cell lung cancer was detected. Additionally, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was conducted in 11 patients, and TP53 mutation was detected in 8 of them.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, dacomitinib showed a durable efficacy and maintained a manageable safety profile but necessitated dose reduction in the majority of patients in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC. For the overall population, ORR was 84.3% and the median PFS was 16.7 months, which was quite superior to the survival results represented in ARCHER 10508.

The primary differences in baseline characteristics compared to ARCHER 1050 are the presence of brain metastasis and racial composition. Unlike ARCHER 1050, which demonstrated a relatively diverse racial distribution with 75% Asian, 25% White, and less than 1% Black participants, this retrospective study was only included Asian in South Korea. Furthermore, ARCHER 1050 excluded patients with brain metastasis, while 45.1% of patients had brain metastasis at the initiation of dacomitinib in this study. Survival results are superior in this study compared to ARCHER 1050, despite including patients with brain metastasis. These superior outcomes are likely attributable to the comprehensive oncology care system, including enhanced supportive care, which may have contributed to the survival benefit. The distribution of smoking status and the prevalence of EGFR mutation, including exon 19 deletion and L858R mutation in exon 21 were comparable between this study and ARCHER 1050.

As mentioned above, the efficacy of dacomitinib in patients with brain metastasis was initially unclear in previous prospective studies. In this study, the inclusion of patients with brain metastasis and survival analysis based on the presence of brain metastasis contributed to obtaining insight regarding this aspect, despite its retrospective nature. The median PFS was 16.7 months despite 45.1% of patients having brain metastasis. Several retrospective studies showed the intracranial efficacy of dacomitinib, with an overall intracranial objective response rate (iORR) of 85%12,13. In a previous prospective study involving 30 patients with brain metastasis, dacomitinib demonstrated an iORR of 96.7% and the median PFS was 17.5 months14.

In subgroup analysis conducted based on EGFR mutation in ARCHER 1050, dacomitinib demonstrated significantly superior survival efficacy compared to gefitinib in patients harboring L858R mutation in exon 21 (hazard ratio: 0.63, 95% CI; 0.44–0.88). The superior survival efficacy of dacomitinib in patients with the L858R mutation in exon 21 represents a unique feature not observed in other EGFR-TKIs, including afatinib, which belongs to the same generation of EGFR TKIs7. Recent in vitro studies revealed that dacomitinib demonstrates the lowest IC50 values for the L858R mutation in exon 21 (IC50 = 2.6) compared to gefitinib (IC50 = 26), erlotinib (IC50 = 16), afatinib (IC50 = 4), and osimertinib (IC50 = 9). The efficacy of dacomitinib in L858R mutation in exon 21 appears to be linked to these IC50 values15. Additionally, in FLAURA, subgroup analysis based on EGFR mutation demonstrates relatively limited OS benefit in L858R mutation in the exon 21 subgroup with osimertinib (hazard ratio: 1.0, 95% CI; 0.71–1.40)16. Dacomitinib may represent a promising treatment option for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC harboring L858R mutation in exon 21, when compared to other EGFR TKIs.

The recommended optimal starting dose for dacomitinib is 45 mg per day in ARCHER 1050. However, women, Asians, and patients with lower body weight tend to reduce the dose17. In this study, dose reductions were necessary in most patients (85.6%) owing to adverse events. Dose reductions occurred more frequently in this study compared to ARCHER 1050, where 66% of patients experienced dose reductions. This study also showed that the reduction to 30 mg took a median time of 1.2 months, while further reduction to 15 mg required a median time of 4.3 months. The relatively early implementation of dose reductions can be attributed to the prevailing belief that a generous reduction is preferable and does not compromise efficacy17. The metabolism of dacomitinib varies individually. In previous study of dacomitinib through plasma concentration, there was no difference among the patients who remained on 45 mg per day, those who had their dose reduced from 45 mg to 30 mg per day, and those who had their dose reduced from 45 mg to 30 mg and then to 15 mg per day. Starting at 45 mg or 30 mg per day and adjusting according to adverse events with close and frequent follow-up is a top-down approach which considered to be optimal17.

It is well-established that T790M mutation in exon 20 occur in 50-60% of patients treated with EGFR first- or second-generation TKIs18. In this study, the T790M mutation was detected in 40.9% of patients who experienced disease progression following dacomitinib treatment, which is lower than the 50–60% reported in previous studies of EGFR TKIs. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that only 56 of the 66 patients with disease progression underwent tissue or liquid biopsy to identify resistance mechanisms. The remaining 10 patients were not evaluated, which could have contributed to the comparatively lower reported rate of T790M mutation in this cohort.

This study had several limitations. The median OS was not reached owing to the relatively short follow-up time. Additionally, the retrospective nature of this study limits the ability to establish definitive causal inferences, as it is based on previously collected data. The small sample size may reduce the statistical validity of the findings, requiring careful interpretation. In the results regarding resistance mechanisms after the use of dacomitinib, it was difficult to report in-depth findings on resistance mechanisms other than T790M, as re-biopsy was not performed in all patients with disease progression and also NGS testing was performed in only a small number of patients after disease progression.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a real-world efficacy of dacomitinib in EGFR-mutated NSCLC as a first-line treatment. With a tolerable safety profile and superior survival efficacy compared with previous prospective studies, it is anticipated to be a valuable second-generation EGFR TKI in clinical practice. Additionally, the study highlights its efficacy in patients with brain metastasis, establishing it as one of the viable treatment options for NSCLC patients with brain metastasis.

Patients and methods

Study participants and study procedure

This study included patients with advanced/metastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC who were administered first-line dacomitinib between January 6th, 2021, and December 9th, 2022 at Samsung Medical Center and St. Vincent’s Hospital. All patients received a dosage of 45 mg of dacomitinib administered once daily in 28-day cycles until they experienced objective disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or death. A dose reduction to 30 mg or 15 mg was performed when patients experienced grade 2 or higher treatment-related toxicities.

We reviewed the electronic clinical records and extracted data on age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, smoking status, stage at initial diagnosis, histopathology, type of EGFR mutation, and distant metastasis at initiation of dacomitinib.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center with a waiver for informed consent (Institutional Review Board no. 2023-05-039).

Study endpoints and statistical analysis

Tumor response was evaluated as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1. Objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the percentage (%) of patients with confirmed CR or PR. PFS was measured from the start of dacomitinib to the date of disease progression using RECIST 1.1 or death from any cause. OS was calculated from the start of dacomitinib to the date of death from any cause. The safety objectives were evaluated according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.3.

The categorical and continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics. The survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using a log-rank test. All p-values were two-sided and confidence intervals (CI) were at the 95% level, with statistical significance defined as p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 and R version 4.3.3.

Acknowledgements

This was an independent, investigator-initiated study supported by Pfizer.

Author contributions

The conception and design of the study were carried out by JE Shin, HA Jung, and BY Shim. Administrative support for the study was provided by BY Shim. The study materials or patients were provided by all the authors. The collection and assembly of data were performed by JE Shin and HA Jung. Data analysis and interpretation were conducted by JE Shin and HA Jung. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. The final approval of the manuscript was given by all the authors.

Data availability

The data analyzed in this study are Samsung Medical center and St. Vincent’s Hospital. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request with the permission of Samsung Medical center and St. Vincent’s Hospital.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2023-05-039), and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, M., Kim, S. Y. & Cheng, H. Update 2020: Management of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung198, 897–907. 10.1007/s00408-020-00407-5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawaguchi, T. et al. Prospective analysis of oncogenic driver mutations and environmental factors: Japan molecular epidemiology for lung cancer study. J. Clin. Oncol.34, 2247–2257. 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2322 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang, Z., Stiegler, A. L., Boggon, T. J., Kobayashi, S. & Halmos, B. EGFR-mutated lung cancer: A paradigm of molecular oncology. Oncotarget1, 497–514 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mok, T. S. et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med.361, 947–957. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosell, R. et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.13, 239–246. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park, K. et al. Afatinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment of patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (LUX-Lung 7): A phase 2B, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol.17, 577–589. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30033-X (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu, Y. L. et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.18, 1454–1466. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30608-3 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soria, J. C. et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.378, 113–125. 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirley, M. Dacomitinib: First global approval. Drugs78, 1947–1953. 10.1007/s40265-018-1028-x (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu, H. A. & Riely, G. J. Second-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancers. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw.11, 161–169. 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0024 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng, W. et al. Dacomitinib induces objective responses in metastatic brain lesions of patients with EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer: A brief report. Lung Cancer152, 66–70. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.12.008 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, J. et al. Efficacy of dacomitinib in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC and brain metastases. Thorac. Cancer12, 3407–3415. 10.1111/1759-7714.14222 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung, H. A. et al. Dacomitinib in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastasis: A single-arm, phase II study. ESMO Open8, 102068. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.102068 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi, Y. & Mitsudomi, T. Not all epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer are created equal: Perspectives for individualized treatment strategy. Cancer Sci.107, 1179–1186. 10.1111/cas.12996 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramalingam, S. S. et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med.382, 41–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corral, J. et al. Effects of dose modifications on the safety and efficacy of dacomitinib for EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol.15, 2795–2805. 10.2217/fon-2019-0299 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan, A. C. & Tan, D. S. W. Targeted therapies for lung cancer patients with oncogenic driver molecular alterations. J. Clin. Oncol.40, 611–625. 10.1200/JCO.21.01626 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study are Samsung Medical center and St. Vincent’s Hospital. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request with the permission of Samsung Medical center and St. Vincent’s Hospital.