Abstract

Background

Pollinators impose strong selection on floral traits, but other abiotic and biotic agents also drive the evolution of floral traits and influence plant reproduction. Global change is expected to have widespread effects on biotic and abiotic systems, resulting in novel selection on floral traits in future conditions.

Scope

Global change has depressed pollinator abundance and altered abiotic conditions, thereby exposing flowering plant species to novel suites of selective pressures. Here, we consider how biotic and abiotic factors interact to shape the expression and evolution of floral characteristics (the targets of selection), including floral size, colour, physiology, reward quantity and quality, and longevity, amongst other traits. We examine cases in which selection imposed by climatic factors conflicts with pollinator-mediated selection. Additionally, we explore how floral traits respond to environmental changes through phenotypic plasticity and how that can alter plant fecundity. Throughout this review, we evaluate how global change might shift the expression and evolution of floral phenotypes.

Conclusions

Floral traits evolve in response to multiple interacting agents of selection. Different agents can sometimes exert conflicting selection. For example, pollinators often prefer large flowers, but drought stress can favour the evolution of smaller flowers, and the size of floral organs can evolve as a trade-off between selection mediated by these opposing actors. Nevertheless, few studies have manipulated abiotic and biotic agents of selection factorially to disentangle their relative strengths and directions of selection. The literature has more often evaluated plastic responses of floral traits to stressors than it has considered how abiotic factors alter selection on these traits. Global change will likely alter the selective landscape through changes in the abundance and community composition of mutualists and antagonists and novel abiotic conditions. We encourage future work to consider the effects of abiotic and biotic agents of selection on floral evolution, which will enable more robust predictions about floral evolution and plant reproduction as global change progresses.

Keywords: Floral evolution, biotic interactions, global change, pollinator-mediated selection, natural selection

INTRODUCTION

Evidence in the fossil record suggests that animal-mediated pollen and spore dispersal date back as far as the Silurian era, 420 million years ago, pre-dating the evolution of angiosperms (Labandeira, 2006). These plant–animal mutualisms have shaped the rapid evolution of floral form and function in angiosperms since the Cretaceous (145 million years ago) (Hu et al., 2008; van der Niet and Johnson, 2012; Gervasi and Schiestl, 2017). In contemporary landscapes, an estimated 90 % of angiosperms have flowers that are pollinated by animals (Ollerton et al., 2011; Tong et al., 2023). These mutualists are potent agents of selection on floral traits, including flower colour (Sletvold et al., 2016; Brunet et al., 2021), floral morphology (Anton et al., 2013), flower size (Lavi and Sapir, 2015), floral display size (Chapurlat et al., 2015), floral rewards, such as nectar and pollen quantity and quality (Ruedenauer et al., 2019; Vandelook et al., 2019), and the timing of development of various floral organs (Wu and Li, 2017). Indeed, the role of pollinators in sculpting floral phenotypes is so crucial that we sometimes overlook other agents of selection that also drive the evolution of flowers (Strauss and Whittall, 2006).

Pollinators are only one component of the network of abiotic and biotic conditions that act on floral traits (Strauss and Whittall, 2006; Sletvold, 2019). A meta-analysis found that abiotic factors exert selection on floral traits at a similar strength to selection imposed by pollinators (Caruso et al., 2019). For example, high ultraviolet (UV) exposure favoured the evolution of greater petal pigmentation in the high-elevation forb Argentina anserina (Rosaceae) (Koski et al., 2022). Furthermore, increasing temperature and drought stress can exert selection on phenology, favouring earlier flowering time (Kooyers, 2015; Ehrlén and Valdés, 2020), and drought favours smaller flowers (Galen, 2000), which have lower rates of transpiration (Galen et al., 1999). In addition, abiotic factors can work in direct opposition to pollinators. For example, bumble bees prefer Polemonium viscosum (Polemoniaceae) flowers with larger corollas, but these individuals have reduced fitness because of drought stress (Galen, 2000). Nevertheless, only eight studies in the meta-analysis by Caruso et al. (2019) manipulated an abiotic factor, and only one study manipulated both biotic and abiotic factors. Studies of selection on floral traits often evaluate only one agent of selection experimentally, but abiotic and biotic factors do not act in isolation. Thus, we still have a limited understanding of the role of abiotic factors in the expression and evolution of floral characteristics, which hinders our ability to predict how rapid global change could influence the eco-evolutionary dynamics of these traits.

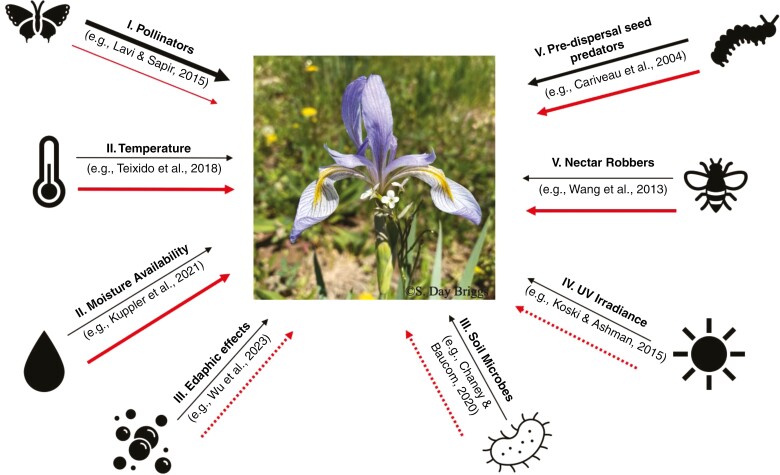

Here, we examine how abiotic and biotic factors act to alter the expression of floral traits and exert selection on floral traits, which can have profound consequences for plant reproductive success and fecundity. We then explore how multiple agents of selection interact to shape the evolution and expression of floral phenotypes by altering the direction, magnitude or even mode (stabilizing, directional or disruptive) of selection on floral traits. These interactions can act synergistically to strengthen the degree of selection in the same direction or they can act antagonistically, imposing selection in opposite directions. For example, pollinator-mediated selection for large flowers can conflict with drought-mediated selection for smaller flowers (Galen, 2000). Climate change is rapidly altering the abiotic conditions that natural populations experience (Hamann et al., 2021a). Novel abiotic conditions attributable to climate change can shift floral trait expression via plasticity (Kuppler et al., 2021) and impose natural selection on these traits that can oppose pollinator-mediated selection (Sletvold, 2019). Furthermore, global declines in pollinator abundance attributable to human actions can weaken the extent of pollinator-mediated selection on floral characteristics (Byers, 2017), shifting the balance of selection to traits favoured under novel climatic regimes. To examine how global change could alter floral phenotypes, we focus on how: (1) the abiotic and biotic environment induces phenotypically plastic changes in both floral and pollinator traits, which alter plant–pollinator interactions; and (2) natural selection via abiotic and biotic agents drives the evolution of floral characteristics. A holistic perspective on plant–pollinator interactions that considers abiotic conditions and other interacting species will enable us, as a community, to make more robust predictions about how global change could influence plant and pollinator fitness in a rapidly changing world (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A conceptual overview demonstrating that multiple agents of selection interact to influence floral evolution. The centred image (©S. Day Briggs), taken at Lake Irwin in Crested Butte, CO, USA, depicts the vast range of flower sizes, ranging from the large charismatic flower of the outcrossing Iris missouriensis (Iridaceae) to the inconspicuous flower of the self-pollinating Boechera stricta (Brassicaceae). The citations reflect examples of studies investigating the role that the indicated agent of selection plays in floral evolution of various flowering species. For simplicity, we indicate the direct effects of these agents of selection independently, although we recognize that they interact. Structural equation modelling would allow researchers to disentangle their interactive effects. The black lines represent the likely historical magnitude of selection on floral evolution, and red lines are representative of potential future relative strengths of selection. Dashed lines indicate that the change in response to global change is unclear. We expect novel suites of conditions to shape floral trait evolution under global change.

GLOBAL CHANGE

Anthropogenic climate change has increased global temperatures and ushered in extreme weather conditions, such as frequent heat waves, droughts and irregular precipitation events (IPCC, 2021). These changes will expose natural populations to novel suites of biotic and abiotic conditions. In addition, climate change, land-use changes and widespread pesticide use have been implicated in global pollinator decline (Potts et al., 2010; Hallmann et al., 2017; Wagner, 2020). These pollinator declines could lead to reduced reproductive success in plant species with specialized pollination syndromes (Ratto et al., 2018). Additionally, a recent study in Ipomoea purpurea (Convolvulaceae) found that plants with reduced access to pollinators produced smaller flowers than plants with ample access to pollinators, indicating a potential plastic response of flower size to pollinator availability (García et al., 2023). If the abundance of floral visitors declines, plants could experience stronger selection for floral rewards to attract the few remaining pollinators (Caruso et al., 2019). Climate change has also altered the timing of critical life-history transitions in plants and their pollinators; these shifts can lead to dramatic phenological mismatches, which have been reviewed extensively elsewhere (e.g. Forrest, 2015; Duchenne et al., 2020; Iler et al., 2021).

Furthermore, selection for the ability to self-fertilize could intensify with climate change (Cheptou et al., 2022), and plastic expression of traits associated with selfing can increase under stressful abiotic conditions (Van Etten and Brunet, 2013). Indeed, global change might lead to greater rates of selfing in self-compatible species (Thomann et al., 2013). For example, in a resurrection study of Viola arvensis (Violaceae) comparing seeds collected in 1991 and 2012, Cheptou et al. (2022) found that contemporary populations had reduced flower sizes, shorter floral longevities and higher rates of self-fertilization, indicating that plants were likely to be responding to local pollinator declines by evolving selfing syndrome traits. Indeed, increasing mean annual temperature and decreasing annual precipitation were associated with increased selfing morphology in herbarium records spanning the years 1875–2015 for the species Viola sororia (Violaceae) (Austin et al., 2022). When compared with outcrossing species, plant species that are predominantly self-pollinating typically harbour limited genetic diversity within populations owing to reduced gene flow; furthermore, increased homozygosity, diminished effective population size, altered strength of selection and other eco-evolutionary processes can have strong effects on the evolutionary dynamics of selfing species (Wright et al., 2013; Clo et al., 2019; Busch et al., 2022), hence they might not be able to adapt rapidly to novel conditions (Franks et al., 2014). For example, a study simulating the complete loss of pollinators in an experimental population of Mimulus gutattus (Phyrmaceae) found that ≤24 % of nucleotide diversity was lost after nine generations of selfing (Busch et al., 2022). Although this evidence suggests that some plants are evolving reproductive strategies to reduce the need for pollinators, little research has evaluated selection on floral traits in primarily self-fertilizing species (Caruso et al., 2019).

Additionally, temperature can influence the survival of pollinators directly. Large bees in warmer climates can experience heat stress and die, whereas smaller bees struggle to thrive in colder climates (Fitzgerald et al., 2022). This theory is consistent with Bergmann’s (1847) observation that species are often larger in cooler climates. This rule generally holds true at the community level for 615 bee species (Gérard et al., 2018). Nevertheless, some larger bees might have greater survival when plant populations are fragmented owing to larger resource stores that allow them to travel longer distances between nutritional sources (Greenleaf et al., 2007; Naug, 2009; Kelemen and Rehan, 2021), but pollinator surveys have documented greater losses of large-bodied insect pollinators relative to small-bodied ones (Müller et al., 2006; Bartomeus et al., 2013; Nooten and Rehan, 2020). Smaller-bodied bees are the more frequent visitors of smaller flowers (Delgado et al., 2023) and are typically less effective at pollination relative to larger bees (Földesi et al., 2021), thus evolutionary shifts in bee body size might also result in selection favouring smaller flowers.

Global change will have direct and indirect effects on plant reproduction. Although we often consider pollinators to be the primary drivers of floral trait evolution, other biotic and abiotic agents also influence the expression and evolution of flowers. To generate reliable predictions about biological responses to global change, we must dissect the contributions of various abiotic and biotic factors to floral trait evolution in the context of rapid environmental change.

POLLINATOR-MEDIATED SELECTION

Pollinator-mediated selection is so strong that phylogenetically unrelated plants frequented by the same pollinators have converged on similar floral characteristics and vegetative morphology (Fenster et al., 2004). Additionally, the strength of selection on floral phenotypes often increases with the degree of pollen limitation, which reflects the dependence of plants on pollinators (Trunschke et al., 2017). That is, species that rely heavily on pollinators, and are pollen limited, experience heightened selection on floral traits (Bartkowska and Johnston, 2015), such as flower size and colour, which serve as honest cues of the quantity or quality of floral rewards (Parachnowitsch et al., 2019; Ortiz et al., 2021; Lozada-Gobilard et al., 2023) . Pollinator preferences can lead to the evolution of increased floral display size, with a greater number of flowers (Weber and Kolb, 2013; Bauer et al., 2017), larger flowers (Fishman and Willis, 2008), greater floral pigmentation (Koski, 2023) with more contrast (Sletvold et al., 2016), and increased production of floral volatile compounds (Knauer and Schiestl, 2016). In addition, pollinators impose selection for increased spur length to allow sufficient pollen to be transferred by pollinators with a long proboscis (Chapurlat et al., 2015).

Pollinators impose consistent selection over multiple generations, resulting in rapid evolutionary changes in their plant mutualists (Gervasi and Schiestl, 2017), which, in some cases, can generate local adaptation of plants to their pollinator communities (Sun et al., 2014). For example, Nerine humilis (Amaryllidaceae) individuals have the highest fecundity in their home sites, where their morphology best matches that of local pollinators (Newman et al., 2015). Owing to the greater attraction of pollinators to locally adapted ecotypes that produce greater floral rewards, pollinators can facilitate and reinforce local adaptation (Takimoto et al., 2022). For example, Phlox drummondii (Polemoniaceae) individuals grown under prolonged drought maintained higher levels of nectar than well-watered individuals only if they originated from arid environments (Suni et al., 2020). Shifts in pollinator assemblages across the range of a species can also drive divergence in phenotypes; for example, regional differences in pollinator communities result in variable selection on floral scent compounds in Gymnadenia odoratissima (Orchidaceae) (Gross et al., 2016).

Pollinator-mediated selection can be so strong that it drives reproductive isolation and speciation in some systems (Hopkins, 2022; Takimoto et al., 2022). In the species Phlox drummondii, pollinator preference for flower colour reduces movement between a dark-coloured morph and a light-coloured congener, Phlox cuspidata, reducing hybridization and reinforcing reproductive isolation between the species (Hopkins and Rausher, 2012). This pollinator reinforcement is also evident in the pollinator fidelity of sympatric Mimulus (Phrymaceae) species, where pollinators rarely move between the pink Mimulus lewisii and the red Mimulus cardinalis (Ramsey et al., 2003). Hybridization in both these systems results in low fitness (Hopkins and Rausher, 2011; Stathos and Fishman, 2014), thus pollinator-mediated selection can play a crucial role in imposing prezygotic reproductive isolation that mitigates the high cost of hybridization (Hopkins, 2013).

Nevertheless, pollinator-mediated selection is only one component of floral evolution. The literature has not thoroughly explored other abiotic and biotic agents of selection individually or how these various agents of selection interact to shape the evolution of floral traits. Below, we explore how agents of selection other than pollinators influence the evolution of floral physiology, size, pigmentation, rewards, scent, longevity and other crucial targets of selection. We organize sections based on key abiotic and biotic factors, and we describe emerging questions that warrant further research.

TEMPERATURE AND MOISTURE AVAILABILITY

Temperature and moisture availability are highly correlated (Fischer and Knutti, 2013) and often have similar effects on plants (Lamaoui et al., 2018), hence it can be difficult to determine their individual contributions to floral trait expression without concerted multifactorial experiments. For that reason, we consider these two factors jointly in this section. We encourage researchers to conduct experiments that manipulate these abiotic factors factorially to dissect their contributions to the expression and evolution of floral traits.

Floral physiology

To regulate temperature in warm environments, plants transpire through both their leaves and their flowers; in fact, the rate of transpiration increases exponentially with increasing floral area (Galen et al., 1999; Teixido and Valladares, 2014). Larger flowers of the Mediterranean species Cistus ladanifer (Cistaceae) experienced disproportionately greater rates of floral transpiration than smaller flowers on the same individual plant (Teixido and Valladares, 2014). Although flowers typically require fewer resources to produce than leaves (Roddy et al., 2023), they are costlier to maintain (Galen et al., 1999; Roddy et al., 2023). Thus, maintaining large flowers in warm, dry environments could reduce plant reproductive success. Flowers are often aborted in experimental warming treatments (Guilioni et al., 1997; Saavedra et al., 2003; Garruña-Hernández et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2019), and failed reproduction in stressful abiotic environments can depress lifetime fecundity (Hamann et al., 2021b). To reduce the loss of reproductive structures, plants can increase floral transpiration relative to vegetative respiration under heat stress to cool reproductive structures at the expense of foliage, as is the case in soybean, Glycine max (Fabaceae) (Sinha et al., 2022). Increased floral transpiration under thermal stress can protect sensitive floral tissue, but it also increases water loss (Bourbia et al., 2020), thereby subjecting plants to heightened drought stress. Much of what we currently know about how temperature and drought stressors influence floral physiology is based on agricultural literature, leaving large gaps in our understanding of how native plants respond to climate extremes.

Floral size

Pollinators often prefer large flowers (e.g. Galen, 1989; Sandring and Ågren, 2009; Lavi and Sapir, 2015), but thermal stress can influence the size of flowers (Teixido et al., 2016). In an intriguing study of Echium plantagineum and Echium vulgare (Boraginaceae), Descamps et al. (2020) manipulated water availability and temperature factorially and found that elevated temperatures alone reduced multiple traits contributing to overall flower size. In contrast, higher temperatures induced larger flowers in the annual crop Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae), although these effects fluctuated with seasonality (López-Atanacio et al., 2022). These studies demonstrate how increasing temperatures can alter flower size through phenotypic plasticity. Nevertheless, how thermal stress influences selection on flower size remains unclear.

Likewise, drought stress augments the cost of large floral displays with many or large flowers because of increased transpiration, leading to plants that produce fewer, smaller flowers (Teixido et al., 2016). For example, Leptosiphon bicolor (Polemoniaceae) experiences significantly reduced flower size in response to drought even after controlling for developmental rate (Lambrecht, 2013). Galen et al. (1999) proposed that drought favours the evolution of smaller flowers through selection, and subsequent studies (Galen, 2000; Carroll et al., 2001; Brunet and Van Etten, 2019) have supported this prediction. Indeed, under drought stress, Sinapis arvensis (Brassicaceae) produces fewer, smaller flowers that are visited less frequently by pollinators than well-watered individuals (Kuppler et al., 2021). In some environments, plants that have evolved drought-escape strategies flower earlier and exhibit reduced correlated traits, such as vegetative biomass and flower size (Franks, 2011; Kooyers, 2015; Hamann et al., 2018; Lambrecht et al., 2020; Kooyers et al., 2021). Thus, it is crucial to determine how selection operates on correlated traits, including the size of individual flowers, the number of flowers produced and drought-escape responses, such as flowering time.

To the best of our knowledge, no experimental study has evaluated the degree to which heat stress, moisture availability and pollinators interact to exert selection on flower size or whether selection imposed by abiotic stress can conflict with pollinator-mediated selection. In an observational study, Teixido et al. (2018) evaluated selection on floral size in two Brazilian congeners in the Clusiaceae, Kielmeyera coriacea and Kielmeyera regalis, which flower in different seasons. In the cool and wet season, directional selection favoured larger K. regalis flowers, but in the hot and dry season, stabilizing selection favoured intermediate flower size in K. coriacea (Teixido et al., 2018). We cannot isolate the agent of selection in this system because this study compares patterns of selection in two different species, and factors such as differences in floral traits or pollinator communities influence selection in different seasons. However, this study suggests that shifts in abiotic conditions might modulate the evolution of flower size. We were unable to find a study addressing this question in a single species.

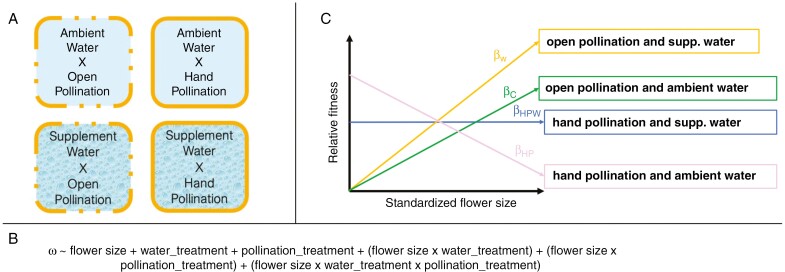

To determine how abiotic and biotic agents of selection drive the evolution of correlated suites of floral traits, we encourage researchers to expose experimental individuals sourced from multiple populations to manipulations of water availability, pollinator visitation and other key agents of selection. Fig. 2 demonstrates predictions from a theoretical experiment that evaluates the relative strengths of selection attributable to pollinator preference and drought-mediated selection on flower size. Multifactorial manipulations require large sample sizes to detect selection; therefore, researchers will need to leverage their understanding of the natural history of their study species from direct observations and greenhouse and growth chamber manipulations of single or dual factors. We highlight that plants often have altered fitness and trait expression in simplified environments in greenhouse and growth chamber experiments compared with the field, which can lead to biases in our conclusions about fitness (Poorter et al., 2016; Forero et al., 2019). For example, a study that evaluated 30 lines of Medicago lupulina (Fabaceae) in both greenhouse and field settings found that fitness and trait expression shifted dramatically between settings, with selection favouring different genotypes depending on the experimental environment (Batstone et al., 2020). Therefore, field experiments within the native range are best to evaluate the absolute values of trait expression and fitness in realistic ecological conditions. Such experiments could disentangle genetic from plastic contributions to trait expression and isolate the specific abiotic or biotic factor that exerts selection on traits such as flower size (Wadgymar et al., 2017; Schwinning et al., 2022).

Fig. 2.

The effects of abiotic factors and pollinators might interact to influence selection on floral traits. We predict that selection for smaller flowers under drought stress counteracts pollinator-mediated selection for larger flowers when water availability is high. (A) This hypothesis can be tested in a multifactorial common garden study in an arid field environment where pollination is either open to pollinators or supplemented by hand pollinations and water is either ambient (dry) or supplemented. In a mesic field environment, researchers could use rain-out shelters or other approaches to reduce water levels for comparison against ambient (wet) conditions. (B) The statistical model would examine relative fitness (ω) as a function of flower size, drought treatment and pollinator treatment, along with all two- and three-way interactions. Non-linear selection could be examined by modeling quadratic or higher-order effects of flower size, and other floral traits could also be included. If these factors interact to exert selection on floral phenotypes, the analyses would reveal a significant three-way interaction of floral trait and the two treatments. In that case, researchers would examine the direction and magnitude of selection in different treatments by contrasting the slopes of the relationship between relative fitness and traits. (C) If pollinator-mediated selection favours larger flowers, then larger flowers would have greater relative fitness under open pollination with supplemental water (orange line, βW). Ambient water levels would expose plants to drought stress, thereby attenuating the strength of selection for larger flowers when pollinators are present (green line, βC). Researchers can examine the strength of pollinator-mediated selection through supplemental pollination, in which experimenters provide ample pollen to all plants, regardless of floral size (e.g. Lavi and Sapir, 2015). Experimental supplementation of pollen and water could relax selection, because small and large flowers have equivalent fitness (blue line, βHPW). Finally, under ambient water and supplemental pollen, drought stress might counteract the effect of pollinators, favouring smaller flowers (pink line, βHP).

Floral pigmentation

Pollinators are often thought to be strong drivers of selection on flower colour, although this has been difficult to detect empirically (Trunschke et al., 2021). Nevertheless, floral pigments clearly evolve in response to temperature along with other biotic and abiotic factors (Rausher, 2008). In cooler environments, darker-coloured flowers can absorb more solar radiation, which warms the flowers (van der Kooi et al., 2019). Floral warmth is a reward sought by many insect pollinators (Seymour et al., 2003; Sapir et al., 2006) and can be a stronger driver of pollinator preference than flower colour (Dyer et al., 2006). Additionally, plants that produce darker floral and fruit pigments can be at an advantage in cooler climates owing to their ability to thermoregulate. For example, darker pigmentation of Plantago lanceolata (Plantaginaceae) flowers and fruits allows plants to maintain warmth in the cool environments of temperate latitudes and to reproduce before herbivores emerge, which increases fecundity (Lacey and Herr, 2005). Herbarium records of 42 flowering species from 1941 to 2017 reveal that pigmentation of floral tissue has decreased with increasing temperature for species with anthers that are concealed in the floral tissue, where they are more susceptible to heat damage (Koski et al., 2020), likely owing to the detrimental effects of heat stress on pollen development and viability (Chaturvedi et al., 2021).

Floral pigments serve multiple functions beyond temperature regulation, including protection of flowers from reactive oxygen species that accumulate during drought stress (Nakabayashi et al., 2014). As a result of oxidative stress in the absence of pigments, Solanum lycopersicum mutants that lack the ability to produce flavonoids that accumulate in reproductive tissue have reduced pollen viability (Muhlemann et al., 2018). Additionally, in Ipomoea purpurea (Convolvulaceae), elevated temperatures favour greater floral pigmentation (Coberly and Rausher, 2003), reflecting the ability of flavonoids to reduce the accumulation of reactive oxygen species that result from heat stress (Brunetti et al., 2013).

Floral organs other than petals and sepals also display colour variation subject to selection. For instance, pollen colour can evolve in response to pollinators (Lau and Galloway, 2004), antagonists, such as pollen thieves (Xiong et al., 2019), and abiotic factors (Jorgensen and Andersson, 2005). Clinal variation in pollen colour exists in the herb Campanula americana (Campanulaceae), as colours range from white in cooler climates to dark purple in warmer climates of the USA, indicating that pollen colour in this system is likely to have evolved in response to temperature variation across the range (Koski and Galloway, 2018). Additionally, in experimental high temperatures, dark pollen is 85 % more likely to germinate than white pollen (Koski and Galloway, 2018), suggesting that pollen pigments also act in oxidative stress pathways to reduce the effects of heat stress. Future studies that disentangle the heat amelioration benefits from flavonoids and floral warming owing to greater floral pigmentation could yield insight into how the evolution of floral pigments will respond to global change. Climate warming could favour lighter pigmentation of floral organs. Future work on the complex relationships of temperature, pollinators and floral pigments will illuminate how increasing temperatures could alter the evolution of the colour of floral organs in different regions globally. Common garden experiments that manipulate temperature and pollination factorially could test whether darker pigmentation has greater fitness in high temperature or whether there is balancing selection owing to pollinator preference and floral warming.

Floral longevity

Floral longevity, or the length of time that a flower remains open and receptive to pollen, can directly influence plant fitness (Ashman and Schoen, 1996). Enhanced floral longevity can ensure effective fertilization (Rathcke, 2003) but can also reduce the number of flowers a plant produces (Spigler and Woodard, 2019). Additionally, pollen and ovule viability can decline with increasing floral age (Ashman and Schoen, 1997). A recent global meta-analysis found that warmer temperatures are correlated with reduced floral longevity (Song et al., 2022). Indeed, for the species Helleborus bocconei and Helleborus foetidus (Ranunculaceae), flowering in warmer conditions can reduce floral longevity from ~42 days to ~7 days (Vesprini and Pacini, 2005). Despite these global correlations of floral longevity and temperature, we know of no study that has determined whether temperature is causally linked with floral longevity or that has evaluated the underlying mechanism.

Floral rewards

Animal-pollinated species often produce attractants and rewards, such as floral scent, nectar and pollen. The quantity and quality of these rewards can depend upon temperature and moisture availability. For example, heat stress can disrupt pollen development and decrease the nutritional quality of pollen (Raja et al., 2019). In the tomato species Lycopersicon esculentum (Solanaceae), thermal stress reduces pollen production, viability and the sugar and starch concentrations (Pressman et al., 2002). Additionally, elevated temperature depressed nectar volume and sugar concentration in Impatiens glandulifera (Balsaminaceae) (Descamps et al., 2021). Reduced nectar production from extreme heat can have lasting impacts even after temperatures return to ambient conditions (Hemberger et al., 2023). Drought stress can also reduce nectar quantity (Phillips et al., 2018; García et al., 2023), thereby diminishing floral rewards available to pollinators. The reduced quality of these floral rewards can have severe impacts on pollinator communities and, therefore, plant reproductive success (Walters et al., 2022). Given that many pollinator species rely on floral rewards for nutrition, these reward traits are often under strong pollinator-mediated selection (Robertson et al., 1999; Schiestl and Johnson, 2013; Z. Zhao et al., 2016). However, a recent study in Ipomoea purpurea (Convolvulaceae) determined that selection favoured increased nectar production even when pollinators were excluded; this surprising result suggests that alternative agents are driving selection on nectar quantity in this system (García et al., 2023). These studies suggest that increasing temperature and aridity under climate change could diminish the supply of rewards to pollinators, which has the potential to alter pollinator behaviour and, potentially, depress plant and pollinator fitness.

Floral scent

Floral volatile organic compounds can regulate biotic interactions, while also playing crucial roles in mitigating the effects of abiotic stress (Loreto and Schnitzler, 2010). Indeed, Ipomopsis aggregata (Polemoniaceae) grown in drought conditions exhibits a non-linear increase in floral scent emission (Campbell et al., 2019). Additionally, changes in floral volatile emissions in response to moisture availability can vary across populations, suggesting a genetic basis for phenotypic plasticity of floral scent (i.e. genotype by environment interactions) (Keefover-Ring et al., 2022). Altered expression of floral scents or shifts in the direction or magnitude of selection owing to changing abiotic conditions could modify ecological interactions and change plant fecundity (Slavković and Bendahmane, 2023). For example, in Sinapis arvensis (Brassicaceae), experimentally increasing scent emission reduced the time to first bumblebee visit and increased the number of visits, although drought stress did not significantly increase floral scent emission (Höfer et al., 2021). Likewise, a meta-analysis found that drought does not necessarily increase overall scent emission, but instead alters the composition of scents (Kuppler and Kotowska, 2021). Clines in the volatile organic compound composition of floral scent have likely evolved in response to aridity gradients, with monoterpenes being more common in plants from dry conditions and sesquiterpenes more prevalent in plants from ambient conditions (Farré-Armengol et al., 2020). Thus, selection acts on compounds individually rather than on total floral scent emission, complicating the study of selection on floral scent (e.g. Chapurlat et al., 2019).

Future directions

Given that moisture availability and temperature typically exhibit a strong correlation (Jin and Mullens, 2014), it can be difficult to disentangle their independent effects on floral traits. Studies often conflate their effects on floral traits, hence their individual contributions to floral evolution remain unclear. A recent report found that precipitation and moisture availability explain global variation in natural selection more so than temperature (Siepielski et al., 2017). Climate change research has allowed us to make predictions about globally increasing temperatures with high confidence, but predictions on how precipitation patterns will change are less certain (IPCC, 2021). Studies that manipulate temperature and aridity factorially could disentangle their correlated effects on floral trait expression and evolution. These studies could be conducted in a similar factorial common garden style to the experiment proposed in Fig. 2. It can be challenging to manipulate temperature in field experiments, although open-top chambers and soil-warming beds are reliable options. In addition, to test whether temperature- and drought-mediated selection conflict with pollinator-mediated selection, future experiments could also manipulate pollen availability in these factorial experiments (e.g. Fig. 2).

To disentangle the relative strengths of selection imposed by pollinators vs. drought on flower size, researchers could design a fully factorial common garden experiment manipulating levels of pollen availability and drought (Fig. 2). Researchers could initially sample seeds from populations distributed across the range, which have evolved in disparate environmental conditions, thereby increasing the phenotypic and genetic diversity of accessions included in the study. Multiple individuals from clonal lines or families of known origin would be transplanted into each treatment to evaluate plastic and genotypic responses to treatments, along with quantitative genetic parameters, such as heritability (e.g. Santangelo et al., 2019). Recent studies evaluating the effects of multiple agents of selection in similar studies have used samples sizes of ~400 individuals per treatment (e.g. Wu et al., 2023), although other studies have used significantly fewer plants (e.g. Knauer and Schiestl, 2016). To manipulate pollinator visitation, researchers would include open pollination and a supplemental pollination, which would reduce selection imposed by pollinators. We have envisioned an experiment in a common garden where ambient conditions are arid and where researchers expose plants to ambient conditions and supplemental water to reduce drought stress; however, this study could also be conducted in a mesic site with rainout shelters to depress water levels. To examine divergent selection in a Lande and Arnold (1983) framework, relative fitness would be regressed on flower size, pollen treatment and water treatment, along with all two- and three-way interactions (Sletvold, 2019). Should pollinators and drought both impose selection on flower size, we would expect to find a significant three-way interaction. We could then determine the direction and magnitude of selection by evaluating the slopes under different treatments. Researchers could use a similar framework to evaluate selection on a variety of traits and should leverage their knowledge of the natural history of their study system to determine appropriate agents of selection to evaluate. An alternative approach to investigating selection involves modifying traits. For example, one could plant various cohorts that flower at different times in the field to expand the phenotypic range of flowering time (Austen and Weis, 2016). Trait modifications, such as changes to floral size or floral rewards, would be more challenging. However, those modifications would directly test whether selection is operating on those traits. Environmental treatments would still need to be imposed to examine how pollinators or other biotic or abiotic factors modify the magnitude, direction or mode of selection.

EDAPHIC CONDITIONS AND THE SOIL MICROBIAL COMMUNITY

Floral display size

Increased soil nutrient and resource availability can augment the number of flowers in a floral display (Muñoz et al., 2005; Burkle and Irwin, 2009; Friberg et al., 2017; Spigler and Woodard, 2019). The flowers produced are often not individually larger in size when plants grow in nutrient-rich soil (Muñoz et al., 2005; Spigler and Woodard, 2019), but the overall larger floral display can enhance pollinator visitation (Conner and Rush, 1996; Akter et al., 2017). For example, Mimulus guttatus (Phrymaceae) grown in serpentine soils produces smaller floral displays that attract fewer pollinators and produces fewer seeds when compared with plants grown in non-serpentine soils (Meindl et al., 2013). Future research should evaluate how slight changes to soil type might influence selection, especially in the context of climate change when plants encounter novel soil types during range expansions.

Because plants can have such strong fitness responses to soil nutrients (Campbell and Halama, 1993), research has evaluated whether higher soil resource levels simply increase mean plant fitness or whether they shift the fitness landscape, favouring different trait values (Caruso et al., 2019). For the common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca (Asclepiadaceae), floral trait values did not differ between plants in the control treatment and those exposed to supplemental nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium; however, fitness was higher in the nutrient-supplemented treatment (Caruso et al., 2005). As such, it remains unclear whether selection acts by directly impacting reproduction or whether plants perform better with additional resources. Furthermore, a recent study in Primula tibetica (Primulaceae) found that water and nutrient supplementation interacted to favour a larger floral display, with the production of more and larger flowers (Wu et al., 2023). Thus, it is possible that nutrient supplementation alone is not enough to alter selection on floral traits if sufficient water supply is not available.

Anthropogenic factors, such as land-use changes and increased demands on agriculture, have had profound effects on soil nutrient availability (Smith et al., 2016). In addition to changing soil nutrient levels, global change has exposed populations to changes in moisture availability (IPCC, 2021). Floral displays have strong plastic responses to edaphic factors (Muñoz et al., 2005; Meindl et al., 2013; Spigler and Woodard, 2019), but the extent to which soil properties directly influence floral evolution remains unclear. Furthermore, we know very little about how edaphic factors interact with other abiotic components, such as drought, to exert selection on flowers.

Pigmentation

Soil nutrients contribute greatly to floral pigmentation (Zhao and Tao, 2015). Indeed, horticulturalists often apply various nutrients to change or improve floral pigmentation in ornamental plants (Burchi et al., 2010). In natural communities, pollinators use colour as a visual cue and may visit a less rewarding flower if it is the same colour as the species that they frequently visit (Coetzee et al., 2021). A growing body of literature explores how edaphic effects exert selection on floral traits (see Caruso et al., 2005; Sletvold et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2023), but this literature generally neglects floral pigmentation. A study in the self-pollinating forb, Boechera stricta (Brassicaceae), found a correlation between flower colour and soil potassium levels along with a potential fitness advantage for individuals with pink/purple flowers vs. those with the more common white flower color in natural populations but did not examine experimentally whether potassium influenced the selective landscape (Vaidya et al., 2018). To the best of our knowledge, what extent edaphic effects influence selection on floral pigmentation remains to be evaluated.

Floral rewards

Outcrossing plants that rely on pollinators invest nutrients from the soil into pollinator rewards and attractants. Soil nutrients can affect the rate of nectar production, the volume of nectar produced, the composition of the nectar (Burkle and Irwin, 2009, 2010; Hoover et al., 2012; Vaudo et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2023) and the rate of pollen production and pollen quality (Jochner et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2019; Pers-Kamczyc et al., 2020). For Juniperus communis (Cupressaceae), nutrient supplementation increases pollen production but decreases the quality of pollen (Pers-Kamczyc et al., 2020). In some cases, nutrient levels interact with other abiotic factors to induce the expression of floral rewards. For instance, nitrogen supplementation in conjunction with elevated temperatures alters the sugar and amino acid composition of nectar in Cucurbita maxima (Cucurbitaceae), but these factors have no effect when manipulated independently (Hoover et al., 2012). Thus, the combination of multiple abiotic factors, especially in the context of global change, could have greater evolutionary consequences than the effect of increasing soil nitrogen availability alone. Few studies have investigated the primary agents of selection on nectar production and composition (Parachnowitsch et al., 2019). Given that floral rewards are a primary source of nutrition for a variety of pollinators, changes to the composition are likely to have strong consequences for the fitness of plants and pollinators.

Floral scent

Floral scents, much like floral rewards, are likely to be subject to changes in soil nutrients. For example, a study in Arabis alpina (Brassicaceae) found that abundant soil nutrients induced greater floral scent emission. Thus, there is likely to be a role for soil nutrients in the expression of floral scent, but the evolutionary role remains unevaluated. Another study in A. alpina found that selfing and outcrossing individuals produce similar levels of floral scent compounds, indicating that pollinators are likely not to be the evolutionary force driving floral scent (Petrén et al., 2021). Thus, it is possible that abiotic conditions drive floral scent evolution in this system, but it remains unstudied.

The effect of the soil biotic community on floral traits

The soil microbial community is complex (Fierer, 2017), and advancements in the field of soil microbiology are needed before finer-scale studies can investigate the role that certain taxa play in selection on floral traits. Nevertheless, the soil microbiome can facilitate the uptake of water and various soil nutrients by plants (Hayat et al., 2010) and is, therefore, likely to contribute to the expression of floral traits through phenotypic plasticity. Bioinoculants, or plant supplements composed of beneficial microbes, can benefit host plants by increasing the size and number of flowers (Saini et al., 2019), while influencing flowering time (Panke-Buisse et al., 2015) and the production of floral pigments (Saini et al., 2017). Researchers are beginning to investigate how the soil biotic community can shift selection on flowering phenology (Lau and Lennon, 2011; Wagner et al., 2014; Chaney and Baucom, 2020). For example, when Ipomoea purpurea (Convolvulaceae) is grown in sterilized vs. inoculated soil, selection for earlier flowering is stronger in the inoculated soil group (Chaney and Baucom, 2020). Furthermore, correlational selection on flowering time and growth rate favoured either fast-growing/early flowering phenotypes or slow growing/late-flowering phenotypes, potentially owing to a lack of mutualists in the simple sterilized soil early in the experiment (Chaney and Baucom, 2020). These studies have demonstrated that the microbial community is capable of exerting selection on floral phenology. Indeed, microbes can exert stronger selection than water availability on phenological and leaf traits in Brassica rapa (Lau and Lennon, 2011). Nevertheless, it is unclear whether microbiota influence selection on floral morphology and rewards. Climate change is expected to have a strong effect on soil microbial communities, increasing diversity and homogenizing the microbiome (Guerra et al., 2021). Plants have already begun to shift their ranges in response to climate change (Lenoir and Svenning, 2015), thereby exposing them to novel soil biotic assemblages. Plant microbes are crucial components of nutrient uptake, disease resistance and abiotic stress mitigation (Trivedi et al., 2020), and because floral traits are directly influenced by these factors, the soil microbial community is likely to influence their expression indirectly. Thus, further research is needed to understand how the soil biotic community influences selection on other floral traits, such as flower colour, how the complexity of the biotic community plays a role in patterns of selection and how selection imposed by the soil biotic community interacts with selection imposed by other abiotic and biotic factors.

Future directions

Industrialization has exposed plants to novel abiotic conditions, including increased N deposition (Ollivier et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2019). The effects of edaphic factors and soil biotic assemblages on floral trait evolution is an emerging field that requires further exploration to understand how both plant and microbial range shifts and increased nitrogen deposition will affect floral evolution. Soil characteristics strongly influence floral trait expression, but questions remain about how those factors influence selection on floral traits. Experiments that contrast selection on floral traits within and beyond the range margin could allow us to make better predictions about floral evolution in future conditions in shifted geographical regions. We know very little about the indirect effect that nutrient supplementation has on pollinators. For example, bumble bee visitation and nectar consumption increases to flowers of Cucurbita maxima plants that are supplemented with nitrogen, but those bees experience significantly reduced longevity, potentially attributable to fertilizers changing sugar compositions of nectar (Hoover et al., 2012). Likewise, Succisa pratensis (Caprifoliaceae) plants supplemented with fertilizer in the greenhouse had different amino acid and sugar compositions from unfertilized plants, which increased mortality rates of bee larvae in colonies of the pollinator Bombus terrestris (Ceulemans et al., 2017). Monitoring pollinator health can be challenging, especially in natural environments, but it is a crucial component of predicting plant persistence in future conditions. Studies that evaluate the soil edaphic and microbial effects on floral evolution should not neglect the indirect effects on pollinators. To test the hypothesis that soil nutrients have indirect effects on pollinators, future manipulative experiments should be done in combination with controlled pollinator enclosures or traditional pollinator observation studies.

ULTRAVIOLET IRRADIANCE

Pigmentation

Floral pigmentation often increases with solar radiation (Berardi et al., 2016; Koski et al., 2022), as is the case with floral anthocyanin content in Silene vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae) across elevational gradients (Berardi et al., 2016). For the Royal Gala apple, Malus domestica (Rosaceae), experimentally increasing UV exposure can plastically induce the production of UV stress-mitigating pigments (Henry-Kirk et al., 2018). In contrast, Clarkia unguiculata (Onagraceae) produced slightly more anthocyanin pigments under LED lights rather than LED + UV light in the greenhouse, although this study did not account for the production of non-anthocyanin flavonoids (Peach et al., 2020). A growing body of literature investigates how UV influences selection on floral pigmentation. For example, in the species Argentina anserina (Rosaceae), UV-absorbing patches on flowers can reduce the amount of pollen-damaging UV reflection onto the anthers, which could otherwise reduce pollen viability (Koski and Ashman, 2015). Koski and Ashman (2015) confirmed this by placing pollen on artificial flowers with varying sizes of UV-absorbing patches, exposing them to UV radiation and quantifying pollen viability. Indeed, UV radiation could play a large role in the evolution of flower pigmentation in many species, but it can be difficult to measure or manipulate in field experiments.

Future directions

As plants migrate poleward and higher in elevation to escape the effects of climate change, they might be exposed to greater degrees of UV stress (Barnes et al., 2017). An increase in production of UV-mitigating floral pigments might result in greater fitness in high-UV environments, but it could conflict with pollinator-mediated selection. Some pollinators demonstrate strong preferences for flower colour and patterns (Sletvold et al., 2016), hence it is possible that shifts in trait values attributable to UV stress might disrupt selection imposed by pollinators on these pigment traits. In addition, pollinator foraging efficiency is influenced by combinations of flower size and colour, such that a specific colour can make a smaller flower more attractive than a larger flower of the same colour (Spaethe et al., 2001). Thus, we need to consider how UV-mediated shifts in pigmentation might affect pollinator attraction in combination with other traits that might also be changing.

ANTAGONISTS

Antagonists, such as florivores, nectar robbers and predispersal seed predators, can exert strong selection on floral traits, which can directly conflict with pollinator-mediated selection (Marquis, 1992; Irwin, 2006; Strauss and Whittall, 2006; Kessler and Halitschke, 2009; Sletvold et al., 2015). For example, both predispersal seed predators and pollinators prefer longer calyx length in Castilleja linariaefolia (Scrophulariaceae), such that plants with shorter calyces escape damage from predators but suffer from reduced pollinator visitation (Cariveau et al., 2004). In this case, predator-mediated selection conflicts with pollinator-mediated selection (Cariveau et al., 2004). Indeed, biotic antagonists could drive the evolution of traits often assumed to be subject to pollinator-mediated selection; for this reason, studies of floral trait evolution in autonomously selfing species could be illuminating, because pollinators do not shape floral evolution. In the selfing forb Boechera stricta (Brassicaceae), flower colour likely evolves in response to both abiotic conditions and herbivory (Vaidya et al., 2018). Indeed, both herbivores and pathogens impose selection on flower colour that conflicts with pollinator-mediated selection in Claytonia virginica (Portulacaceae), resulting in the maintenance of flower colour polymorphisms within natural populations (Frey, 2004). Herbivores not only alter selection on floral traits, but they can also alter the expression of floral traits through plasticity (Moreira et al., 2019; Rusman et al., 2019). Indeed, B. rapa (Brassicaceae) plants subjected to herbivory from Pieris brassicae (Pieridae) produced a larger number of open flowers with reduced floral scent emission than control individuals (Schiestl et al., 2014), which could result in increased fecundity in herbivorized plants.

Many floral traits function to attract floral visitors, leading to higher rates of fertilization, but they can also result in increased floral and vegetative herbivory from larvae, which can reduce fitness dramatically. For example, in Gymnadenia conopsea (Orchidaceae), pollinator-mediated selection favours larger flowers, whereas selection owing to herbivory on flowers, fruits and leaves favours smaller flowers (Sletvold et al., 2015). Herbivores can also use nectar as a cue for plant nutrient level, potentially through taste, leading to conflicting herbivore- and pollinator-mediated selection on nectar traits (Adler and Bronstein, 2004). Additionally, floral scent is a crucial component of pollinator attraction (Parachnowitsch et al., 2012), although it can also play a role as an antagonist deterrent (Schiestl et al., 2011). These conflicting interactions can vary through space and time, generating intriguing patterns of phenotypic differentiation across the landscape (Nuismer et al., 2000). That is, net selection on floral display size or floral scent resulting from interactions with mutualists and antagonists is likely to fluctuate across the range of a species depending on the local prevalence of these interacting species. Furthermore, studies that isolate the effect of pollinators often reveal that pollinators favour delayed flowering (Sandring and Ågren, 2009; Chen et al., 2017). In Gymnadenia conopsea, flowering time evolves through a balance of pollinator-mediated selection for delayed flowering and herbivore-mediated selection for early flowering (Sletvold et al., 2015). In contrast, in Lobelia siphilitica (Lobeliaceae), pollinators do not exert selection on flowering time; instead, predispersal seed herbivores select for later flowering (Parachnowitsch and Caruso, 2008). These examples demonstrate that manipulations of multiple agents of selection in factorial experiments can better evaluate how selection occurs in natural systems.

Similar patterns arise through the actions of pathogens. For instance, in both Dianthus silvester and Silene dioica (Caryophyllaceae) larger floral displays attract more pollinators that should increase the fecundity of those plants, but pollinators can deposit the anther smut fungus, Microbotryum violaceum (Shykoff et al., 1997; Giles et al., 2006). Infection by M. violaceum fills reproductive structures with spores and eventually prevents any further plant reproduction, thereby counteracting pollinator-mediated selection for larger flowers (Giles et al., 2006). Given that climate change has shifted the geographical distributions of both plants and plant pathogens, plants could encounter novel pathogens that shift historical patterns of selection (Elad and Pertot, 2014).

Finally, nectar robbers can influence selection on floral traits (Irwin et al., 2010). Concordant with the examples above, selection mediated by nectar robbers can oppose that of pollinators (Irwin, 2006). However, this pattern of selection can vary depending on floral morphology. Specifically, both pollinators and nectar robbers act in concert to favour larger flowers of Impatiens oxyanthera (Balsaminaceae), as larger flowers are more difficult to rob (Wang et al., 2013). Thus, selection imposed by nectar robbers is variable and likely to differ depending on floral morphology and on nectar availability.

Future directions

Global change will have strong effects on biotic interactions (Blois et al., 2013; Alexander et al., 2015; Hamann et al., 2021a). A meta-analysis of range and phenological shifts found that mobile terrestrial insects, animals and fungi are generally responding to climate change more rapidly than most plants (Vitasse et al., 2021). As these insects, animals and fungi shift their ranges in response to climate changes, plants will be exposed to novel antagonistic interactions that will shift historical patterns of selection. Given that antagonists can act in conflict with pollinators, more is required to investigate their interactive effects in factorial studies. In addition, the interactive effects of abiotic factors and antagonists might favour a more inconspicuous floral display, but it is unclear whether the combined effects would be additive or synergistic or how these patterns of selection would interact with pollinator-mediated selection.

INTERACTIONS OF MULTIPLE AGENTS OF SELECTION

Although studies that investigate agents of selection independently are informative, they do not reveal how selection operates in complex environments or under changing climates (Sletvold, 2019), hindering our predictions of floral evolution in contemporary landscapes. We have outlined some predicted changes in floral traits owing to global change in Table 1. For simplicity, we outline how changes in a single factor might shift selection or trait values, but we emphasize that some of these predicted effects will conflict with or enhance the effects of other components. For example, ungulate herbivory in Erysimum mediohispanicum (Brassicaceae) disrupts pollinator-mediated selection on various floral and plant traits (Gómez, 2003), hence we expect floral and vegetative traits to evolve differently in areas of high and low herbivory. Of the studies that have investigated multiple agents of selection, few have focused on interactions of biotic and abiotic factors (Caruso et al., 2019). A recent study in Primula tibetica (Primulaceae) found that the strength and direction of pollinator-mediated directional selection on the number of flowers shifts depending on water and nutrient availability, with selection favouring fewer flowers under water and nutrient restriction and more flowers under supplemental water and nutrients (Wu et al., 2023). Other abiotic factors, such as UV and temperature, are more difficult to manipulate, leading to a dearth of studies on interactions of these conditions with pollinators. Studies investigating these components individually suggest that greater floral pigmentation evolves in response to high UV exposure (Peach et al., 2020) and high thermal stress favours reduced pigmentation (Koski and Galloway, 2018), indicating potentially conflicting selective pressures in a high-UV and high-temperature environment. Thus, current research demonstrates that UV and temperature factors play a role in floral evolution, but their relative roles and the strength of their interactions remain to be investigated.

Table 1.

Predictions of floral trait responses to novel conditions associated with industrialization. Here, we summarize predictions laid out in each section of this manuscript for how selection and floral trait values could shift under global change. Each corresponding section of the main text has a more nuanced discussion of these predictions.

| Global change prediction | Trait prediction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower size | Pigmentation | Rewards | Scent | Longevity | ||

| Pollinators | Reduced pollinator abundance and diversity. Range shifts alter community compositions | For species with mixed mating systems, possible relaxation of selection for larger flowers (Fishman and Willis, 2008) | Reduced pollinator abundance or novel pollinators might shift the strength of selection on different pigments, because pollinators can have strong preferences for different flower colours (Hopkins and Rausher, 2012) | Reduced pollinator abundances will relax selection favouring greater floral rewards (Fenster et al., 2004) | Novel pollinator assemblages could shift the strength of selection on floral scent compounds (Knauer and Schiestl, 2016) | Reduced pollinator abundance could favour increased floral longevity to ensure reproductive success of outcrossing species (Rathcke, 2003) |

| Temperature and moisture availability | Global increased temperatures. Precipitation decreases in some areas and increases in others | Flower size decreases in drought conditions (Kuppler et al., 2021). Selection favours smaller flowers under elevated drought stress (Galen, 2000) and temperatures (Teixido et al., 2016) | Selection could favour darker pigmentation to mitigate oxidative stress (Coberly and Rausher, 2003) or reduced pigmentation if darker flowers overheat in high-temperature environments (Koski et al., 2020) | High temperatures and drought can decrease nectar production (Descamps et al., 2021; García et al., 2023), but this might be a stress response. Unclear predictions for shifts in the magnitude or direction of selection | Drought conditions increase floral scent emissions (Campbell et al., 2019) and alter compositions (Kuppler and Kotowska, 2021). Thus, we predict that aridification could favour greater scent emissions | High temperatures reduce floral longevity (Vesprini and Pacini, 2005), which could be a stress response. Unclear predictions for shifts in the magnitude or direction of selection |

| Edaphic conditions and soil microbes | Increased nitrogen deposition and pollution, range shifts of plants and microbes could expose plants to novel microbial communities | Selection might favour larger flowers in regions where greater nutrient availability is combined with greater moisture availability (Wu et al., 2023) | Abundant soil nutrients can increase floral pigment production (Zhao and Tao, 2015). The role of selection attributable to edaphic effects and soil biota on floral pigmentation remains unresolved | Increased nutrients can augment nectar volume and concentration and pollen quantity (Vaudo et al., 2022). Unclear predictions for shifts in the magnitude or direction of selection | Higher soil nutrient levels can induce heightened floral scent emissions (Luizzi et al., 2021). Unclear predictions for shifts in the magnitude or direction of selection | No clear predictions |

| Ultraviolet irradiance | Poleward and upslope range shifts increase exposure to UV radiation | No clear predictions | Given that pigmentation can increase in response to high UV radiation exposure (Henry-Kirk et al., 2018), we predict that selection could favour greater UV-absorbing pigmentation to reduce UV damage to reproductive structures (Koski and Ashman, 2015) | No clear predictions | No clear predictions | No clear predictions |

| Antagonists | Reduced insect abundance. Altered community compositions. Range shifts leading to novel biotic interactions | If antagonists (florivores, nectar robbers and fungal pathogens) prefer larger flowers, declines in their abundance would relax selection for smaller flowers (Cariveau et al., 2004) | Reduced antagonist abundances might relax selection for lighter-coloured inconspicuous flowers (Frey, 2004) | Selection might favour larger nectar volume when antagonist interactions are reduced (Adler and Bronstein, 2004) | Reduced antagonist interactions might favour increased floral scent emissions and other attractants (Schiestl et al., 2014; Knauer and Schiestl, 2016) | No clear predictions |

CONCLUSION

Global change is rapidly altering the biotic and abiotic environments that plants experience, which is shifting the expression of floral traits via plasticity and imposing novel selection on these traits. Evolutionary ecologists often focus on how pollinators have shaped various floral traits, yet floral form and function are likely to evolve through the joint actions of multiple agents of selection, some of which conflict with each other. Investigating how both biotic and abiotic components interact is crucial for understanding plant reproduction and evolution as global change progresses. It is possible that in benign conditions, pollinator-mediated selection drives the evolution of floral traits, but that in stressful conditions abiotic agents of selection prevail. For example, drought-mediated selection conflicts with pollinator-mediated selection for larger flowers (Galen, 2000). The effects of multiple agents of selection might not be additive, as is the case for the effect of water and nutrient availability on flower size (Wu et al., 2023). Additionally, the effect of one agent of selection might depend on other factors that are also influencing a trait (Sletvold, 2019). Furthermore, global change might reduce pollinator abundance, which would elevate the importance of other abiotic and biotic factors in the continued evolution of flowers. By dissecting the contributions and interactions of different agents of selection to floral evolution, we can generate more robust predictions of plant responses to climate change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Johanne Brunet, Amy Parachnowitsch and an anonymous reviewer for the insightful comments on a previous draft. We would also like to thank Derek Denney, Inam Jameel, Lillie Pennington, Mia Rochford, Kelly McCrum, Liz Thomas, Daniel Briggs and Tom Pendergast for discussions and comments on a previous draft.

Contributor Information

Samantha Day Briggs, Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Jill T Anderson, Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the American Iris Society Foundation, a faculty seed grant from the University of Georgia, and grants from the U.S. National Science Foundation (IOS-2220927 and DEB-1553408 to J. Anderson).

LITERATURE CITED

- Adler LS, Bronstein JL.. 2004. Attracting antagonists: does floral nectar increase leaf herbivory? Ecology 85: 1519–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Akter A, Biella P, Klecka J.. 2017. Effects of small-scale clustering of flowers on pollinator foraging behaviour and flower visitation rate. PLoS One 12: e0187976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JM, Diez JM, Levine JM.. 2015. Novel competitors shape species’ responses to climate change. Nature 525: 515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton, KA, Ward RJ, Cruzan, MB.. 2013. Pollinator-mediated selection on floral morphology: evidence for transgressive evolution in a derived hybrid lineage. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 26: 660–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman T-L, Schoen DJ.. 1996. Floral longevity: fitness consequences and resource costs. In: Lloyd DG, Barrett SCH. eds. Floral biology: studies on floral evolution in animal-pollinated plants. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall, 112–139. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-4613-1165-2_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman T-L, Schoen DJ.. 1997. The cost of floral longevity in Clarkia tembloriensis: an experimental investigation. Evolutionary Ecology 11: 289–300. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1018416403530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austen EJ, Weis AE.. 2016. The causes of selection on flowering time through male fitness in a hermaphroditic annual plant. Evolution 70: 111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MW, Cole PO, Olsen KM, Smith AB. 2022. Climate change is associated with increased allocation to potential outcrossing in a common mixed mating species. American Journal of Botany 109: 1085–1096. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.16021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PW, Ryel RJ, Flint SD.. 2017. UV screening in native and non-native plant species in the tropical alpine: implications for climate change-driven migration of species to higher elevations. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 1451. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2017.01451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowska MP, Johnston MO.. 2015. Pollen limitation and its influence on natural selection through seed set. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28: 2097–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartomeus I, Ascher JS, Gibbs J, et al. 2013. Historical changes in Northeastern US bee pollinators related to shared ecological traits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 4656–4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batstone RT, Peters MAE, Simonsen AK, Stinchcombe JR, Frederickson ME.. 2020. Environmental variation impacts trait expression and selection in the legume–rhizobium symbiosis. American Journal of Botany 107: 195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AA, Clayton MK, Brunet J.. 2017. Floral traits influencing plant attractiveness to three bee species: consequences for plant reproductive success. American Journal of Botany 104: 772–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi AE, Fields PD, Abbate JL, Taylor DR.. 2016. Elevational divergence and clinal variation in floral color and leaf chemistry in Silene vulgaris. American Journal of Botany 103: 1508–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann C. 1847. Über die Verhältnisse der Wärmeökonomie der Thiere zu ihrer Größe, Vol. 3. Munich, Germany: Gottinger Studien, 595–708. [Google Scholar]

- Blois JL, Zarnetske PL, Fitzpatrick MC, Finnegan S.. 2013. Climate change and the past, present, and future of biotic interactions. Science 341: 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbia I, Carins-Murphy MR, Gracie A, Brodribb TJ.. 2020. Xylem cavitation isolates leaky flowers during water stress in pyrethrum. The New Phytologist 227: 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet J, Van Etten ML.. 2019. The response of floral traits associated with pollinator attraction to environmental changes expected under anthropogenic climate change in high-altitude habitats. International Journal of Plant Sciences 180: 954–964. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1086/705591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet J, Flick AJ, Bauer AA.. 2021. Phenotypic selection on flower color and floral display size by three bee species. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 587528. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.587528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti C, Di Ferdinando M, Fini A, Pollastri S, Tattini M.. 2013. Flavonoids as antioxidants and developmental regulators: relative significance in plants and humans. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14: 3540–3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchi G, Prisa D, Ballarin A, Menesatti P.. 2010. Improvement of flower color by means of leaf treatments in lily. Scientia Horticulturae 125: 456–460. [Google Scholar]

- Burkle LA, Irwin RE.. 2009. The effects of nutrient addition on floral characters and pollination in two subalpine plants, Ipomopsis aggregata and Linum lewisii. Plant Ecology 203: 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Burkle LA, Irwin RE.. 2010. Beyond biomass: measuring the effects of community-level nitrogen enrichment on floral traits, pollinator visitation and plant reproduction. Journal of Ecology 98: 705–717. [Google Scholar]

- Busch JW, Bodbyl-Roels S, Tusuubira S, Kelly JK.. 2022. Pollinator loss causes rapid adaptive evolution of selfing and dramatically reduces genome-wide genetic variability. Evolution 76: 2130–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers DL. 2017. Studying plant–pollinator interactions in a changing climate: a review of approaches. Applications in Plant Sciences 5: 1700012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DR, Halama KJ.. 1993. Resource and pollen limitations to lifetime seed production in a natural plant population. Ecology 74: 1043–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DR, Sosenski P, Raguso RA.. 2019. Phenotypic plasticity of floral volatiles in response to increasing drought stress. Annals of Botany 123: 601–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariveau D, Irwin RE, Brody AK, Garcia-Mayeya LS, Von Der Ohe A.. 2004. Direct and indirect effects of pollinators and seed predators to selection on plant and floral traits. Oikos 104: 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll AB, Pallardy SG, Galen C.. 2001. Drought stress, plant water status, and floral trait expression in fireweed, Epilobium angustifolium (Onagraceae). American Journal of Botany 88: 438–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso CM, Remington DLD, Ostergren KE.. 2005. Variation in resource limitation of plant reproduction influences natural selection on floral traits of Asclepias syriaca. Oecologia 146: 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso CM, Eisen KE, Martin RA, Sletvold N.. 2019. A meta‐analysis of the agents of selection on floral traits. Evolution 73: 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceulemans T, Hulsmans E, Vanden Ende W, Honnay O.. 2017. Nutrient enrichment is associated with altered nectar and pollen chemical composition in Succisa pratensis Moench and increased larval mortality of its pollinator Bombus terrestris L. PLoS One 12: e0175160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney L, Baucom RS.. 2020. The soil microbial community alters patterns of selection on flowering time and fitness‐related traits in Ipomoea purpurea. American Journal of Botany 107: 186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapurlat E, Ågren J, Sletvold N.. 2015. Spatial variation in pollinator-mediated selection on phenology, floral display and spur length in the orchid Gymnadenia conopsea. The New Phytologist 208: 1264–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapurlat E, Ågren J, Anderson J, Friberg M, Sletvold N.. 2019. Conflicting selection on floral scent emission in the orchid Gymnadenia conopsea. The New Phytologist 222: 2009–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi P, Wiese AJ, Ghatak A, Záveská Drábková L, Weckwerth W, Honys D.. 2021. Heat stress response mechanisms in pollen development. The New Phytologist 231: 571–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhang B, Li Q.. 2017. Pollinator-mediated selection on flowering phenology and floral display in a distylous herb Primula alpicola. Scientific Reports 7: 13157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheptou P-O, Imbert E, Thomann M.. 2022. Rapid evolution of selfing syndrome traits in Viola arvensis revealed by resurrection ecology. American Journal of Botany 109: 1838–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clo J, Gay L, Ronfort J.. 2019. How does selfing affect the genetic variance of quantitative traits? An updated meta-analysis on empirical results in angiosperm species. Evolution 73: 1578–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coberly LC, Rausher MD.. 2003. Analysis of a chalcone synthase mutant in Ipomoea purpurea reveals a novel function for flavonoids: amelioration of heat stress. Molecular Ecology 12: 1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee A, Seymour CL, Spottiswoode CN.. 2021. Facilitation and competition shape a geographical mosaic of flower colour polymorphisms. Functional Ecology 35: 1914–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Conner JK, Rush S.. 1996. Effects of flower size and number on pollinator visitation to wild radish, Raphanus raphanistrum. Oecologia 105: 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JK, Aguirre LA, Barber NA, Stevenson PC, Adler LS.. 2019. From plant fungi to bee parasites: mycorrhizae and soil nutrients shape floral chemistry and bee pathogens. Ecology 100: e02801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado T, Leal LC, El Ottra JHL, Brito VLG, Nogueira A. 2023. Flower size affects bee species visitation pattern on flowers with poricidal anthers across pollination studies. Flora 299: 152198. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2022.152198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Descamps C, Marée S, Hugon S, Quinet M, Jacquemart A-L.. 2020. Species-specific responses to combined water stress and increasing temperatures in two bee-pollinated congeners (Echium, Boraginaceae). Ecology and Evolution 10: 6549–6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descamps C, Boubnan N, Jacquemart A-L, Quinet M.. 2021. Growing and flowering in a changing climate: effects of higher temperatures and drought stress on the bee-pollinated species Impatiens glandulifera Royle. Plants 10: 988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchenne F, Thébault E, Michez D, et al. 2020. Phenological shifts alter the seasonal structure of pollinator assemblages in Europe. Nature Ecology & Evolution 4: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer AG, Whitney HM, Arnold SEJ, Glover BJ, Chittka L.. 2006. Bees associate warmth with floral colour. Nature 442: 525–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]