Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to determine the impact of preconception paternal alcohol consumption (PPAC) on retinal function and morphology in PPAC-offspring. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD)–related ocular defects caused by maternal alcohol exposure has been well investigated, but the influence of PPAC on offspring eyes remains unknown.

Methods

Adult C57BL/6J male mice were exposed to either 10% ethanol or water (control) for six weeks and bred to naïve females. Dark-adapted retinal light responses at two, four, and six months old were assessed using electroretinography (ERG) for the offspring born to PPAC and control males. The thicknesses of whole retinas and different retinal layers of the control and PPAC-offspring were analyzed at two and six months old.

Results

Some PPAC-offspring had only one developed eye. ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes were reduced in PPAC-offspring compared to controls, with a more pronounced effect in females. PPAC had significant effects on inner retinal function. At two months old, there was a significant thinning of the retinal inner nuclear and inner plexiform layers in PPAC-offspring. At six months old, the retinal thickness and ERG amplitudes were similar between both treatment groups.

Conclusions

This study provides pioneering evidence that PPAC contributes to FASD-related ocular defects including negative impacts on retinal light responses and retinal thinning in young adult offspring. Thus the adverse impact of paternal alcohol consumption prior to conception on their offspring (from childhood to early adulthood) should be considered as seriously as the maternal contribution to FASD.

Keywords: preconception paternal alcohol consumption, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, ocular defects, microphthalmia, electroretinography, retinal morphology

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is a spectrum of alcohol-related developmental disorders negatively affecting 1% to 5% of the population in Western countries.1 FASD-related disabilities, especially neurodevelopmental disorders, annually cost the US over 4 billion dollars.1 While FASD caused by maternal drinking during pregnancy and nursing has been investigated intensively, 75% of FASD children have alcoholic biological fathers,2 and more males than females in the US are heavy drinkers.3 In a large-scale clinical study with only 3% of the mothers reporting alcohol consumption, 40.4% of FASD-children had paternal alcohol-exposure,4 which clearly demonstrates that FASD-birth defects are associated with preconception paternal alcohol consumption (PPAC). Hence, PPAC is an emerging contributor to the teratogenic effects of FASD.5–8

More than 90% of FASD children have ocular abnormalities,9 making the eye a sensitive indicator of alcohol toxicity. FASD associated ocular defects exhibit a spectrum of phenotypes including external eye malformations, microphthalmia, optic nerve hypoplasia, short palpebral fissure, uveal coloboma, blepharoptosis, increased retinal vessel tortuosity, coloboma, strabismus, retinal dysmorphia, reduced visual acuity, abnormal light responses, and other visual impairments.10–13 Ocular development is susceptible to teratogenic stressors such as alcohol and neurotoxicants, and developmental delays, impaired neural cell differentiation, and increased retinal cell loss are observed in alcohol-mediated ocular defects.14 In utero exposure to ethanol causes significant deficits in rod photoreceptor sensitivity to light in rats, which affects dark adaptation.15 However, the influence of PPAC on the development and health of the offspring remains understudied,7,16 and the contribution of PPAC in FASD-associated ocular abnormalities is unknown. Hence, the purpose of this study is to provide new evidence on the adverse contributions of PPAC to ocular abnormalities with a focus on retinal physiology and morphology in the offspring.

Our team previously established a mouse model for PPAC17–23 that mimics male binge drinking behavior during their circadian active phase (the night/dark phase for mice).17,18,21,22,24 The males given alcohol for 6 weeks prior to mating with non-alcohol females have offspring with developmental defects including dysfunctional placentae, fetal growth restriction, delayed fetal gestation, suppressed immune responses,19,21,25 abnormal cholesterol metabolism,26 microcephaly, and abnormal craniofacial formations.22 As growth deficiency, facial dysmorphology, and microcephaly are often observed in children with FASD,27–29 these data strongly support that PPAC contributes to FASD. Based on our previous observation that PPAC contributes to microcephaly22 and microphthalmia36 in their offspring, we hypothesized that PPAC not only causes microphthalmia but also functional deficiencies of the neural retinas in PPAC-offspring. In this study, we investigated the influence of PPAC on adult offspring retinal physiology and morphology by measuring the retinal light responses via electroretinograms (ERGs) and changes in thicknesses of various retinal layers up to 6 months old. We further analyzed the differential influences of PPAC on male and female offspring, as well as on central versus peripheral retinal thicknesses. This is the first study of PPAC-associated adverse effects on retinal light responses and morphology of the offspring.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments complied with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols (AUP #2020-0211, #2020-0286) of Texas A&M University and the Association of Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO, Rockville, MD, USA) guidelines for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Adult male and female C57BL/6J mice (Strain#:000664 RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The colony used for this study was housed at the Texas Institute of Genomic Medicine (TIGM, Texas A&M, College Station, TX, USA) under temperature- and humidity-controlled conditions, on a reverse 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights off at 8:30 am) with ad libitum access to a standard chow (catalog# 2019, Teklad Diets, Madison, WI, USA) and water. To minimize stress, shelter tubes for males and igloos for females (catalog# K3322 and catalog# K3570, Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ, USA) were placed in their home cages.

Preconception Paternal Ethanol Exposures

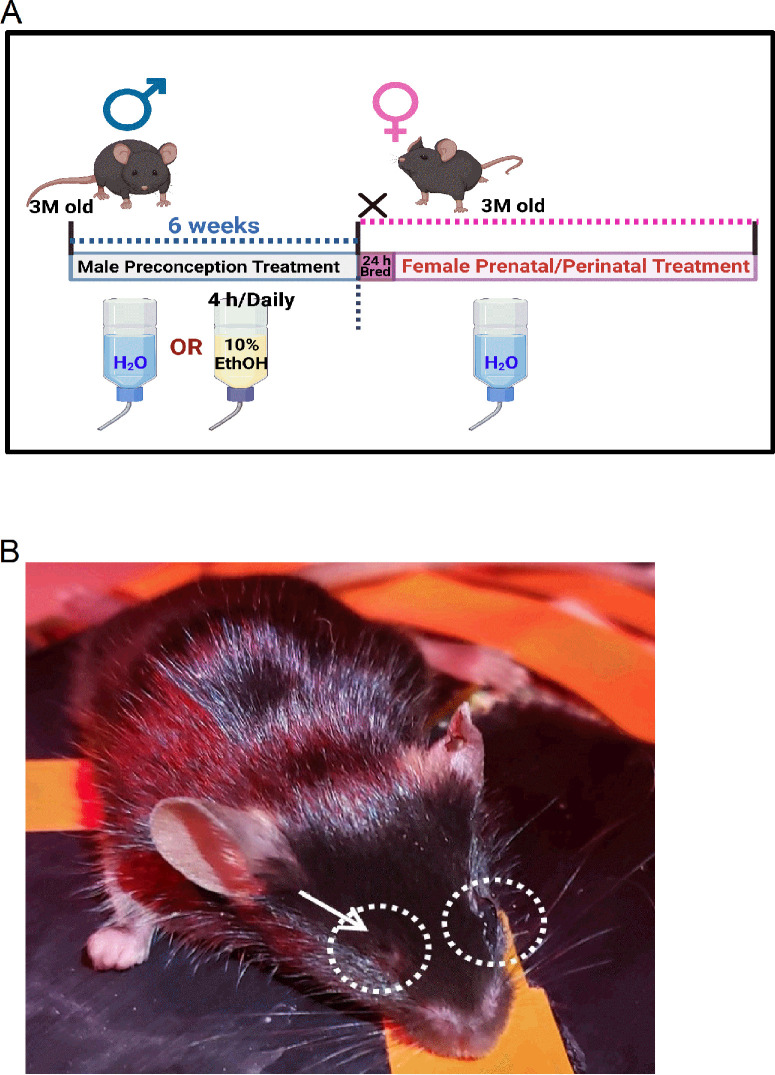

The preconception paternal ethanol treatments were described previously (Fig. 1A).17,18,21,22 Briefly, three-months old male mice were randomly assigned to either control (water only) or experimental (10% w/v ethanol; catalog# E7023; Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) groups. Male mice were first acclimated to individual housing conditions for one week. After which, we used a modified version of the “Drinking in the Dark” model of voluntary alcohol consumption.30 Three hours into the dark phase, their home cage water bottles were replaced with either water (control) or 10% ethanol (experimental group) for four hours daily for six weeks (preconception period), encompassing one complete spermatogenic cycle in male mice.21,22,31 Water bottles of control and ethanol-treated males were exchanged concurrently to ensure identical handling and stress. Males were then bred to naïve three-month-old females whose reproductive cycles were first synchronized21,22,32 while maintaining the male preconception treatments. A female was placed into a male's home cage immediately after the daily exposure window. Six hours after confirmed mating (presence of a vaginal plug), females were returned to their original cages. The offspring from control or paternal ethanol-exposed (P-Ethanol) groups were collected at various postnatal ages for further analyses.

Figure 1.

The PPAC experimental model and a representative photograph of a PPAC-offspring mouse with a missing eye. (A) A schematic diagram of the PPAC experimental treatment model. Three-month-old (3M) males were given either water (control) or 10% ethanol (four hours per day) for six weeks before breeding with naïve females (three months old). After confirmed mating with the presence of a vaginal plug, females were returned to their own cages. (B) Few PPAC-offspring mice were born with one eye, and in this case, the left eye was fully developed, but the right eye (arrow) was missing or recessed within the eye socket.

In Vivo Electroretinogram (ERG)

The in vivo ERG recordings of retinal light responses were performed as described previously.33,34 Mice were dark adapted for at least three hours and anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (2% 2,2,2-tribromoethanol, 1.25% tert-amyl alcohol; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) solution (12.5 mg/ml) at a dosage of 500 µL per 25 g body weight. Pupils were dilated using a drop of 1% tropicamide/2.5% phenylephrine mixture for five minutes. Mice were placed on a heating pad to maintain the body temperature at 37 °C. The ground and reference electrodes were placed on the tail and under the cheek skin, respectively. A thin drop of Goniovisc (Hub Pharmaceuticals, Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA) was applied on the cornea to keep it moist, and a threaded recording electrode conjugated to a mini contact lens (Ocuscience, Henderson, NV, USA) was positioned on the cornea. All preparatory procedures were done under dim red light, which was turned off during the recording. A portable ERG device (OcuScience) was used to measure dark-adapted ERG recordings at light intensities of 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 25 cd ∙ s/m2. Responses to four light flashes were averaged at lower light intensities (0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 cd ∙ s/m2), while only one light flash was applied for higher intensities (10 and 25 cd ∙ s/m2). The low pass filter cutoff was at 150 Hz (OcuScience). A one-minute recovery period was programmed between different light intensities. The amplitudes and implicit times of the ERG a- and b-wave were analyzed using ERGView 4.4 software (OcuScience).

Ocular Tissue Processing and Retinal Morphometrics

Eyes from two- and six-months old offspring were collected for retinal morphometrics. After euthanasia, mice eyes were excised and prepared as previously described.35 Briefly, eyes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, washed PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.3), post-fixed in 70% ethanol, and further processed for paraffin-embedded sagittal sectioning at 4 µm. The eye sections from both control and P-Ethanol groups were mounted on the same slide. Sections selected for retinal morphometrics were collected closest to the optic nerve head to ensure consistency across all samples and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin after deparaffinization to visualize retinal morphology. Because retinal thickness is not homogenous, we selectively chose the central and peripheral areas for measurements. All experimental groups were measured in the same manner. Images of one central (adjacent to the optic nerve head) and two peripheral retinal areas (equidistant [to the left and right] from the central) per section were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA) under identical magnification (×4 and ×40). Retinal thickness was quantified for various retinal layers: outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), inner nuclear layer (INL), and inner plexiform layer (IPL), by an individual blind to the sample identities. Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) software was used to quantify these measurements. Data from three sections of the same eye were averaged as n = 1, and each group had at least two eyes from three mice (n = 6).

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The factors taken into consideration were paternal treatment group, sex, and age. Student's t-test was first used to determine the statistical difference between males and females of the same age and treatment. If statistical differences were observed at a particular age, then the data for males and females were analyzed independently. If not, then data from both sexes were combined for further analyses. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test for unbalanced n was used for statistical comparison. Throughout, P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Origin 9.0 was used for statistical analyses and graph plotting (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Results

Preconception Paternal Alcohol Consumption (PPAC) Causes Gross Anatomical Changes in the Offspring

Microphthalmia is common among newborns and young children diagnosed with FASD.13 We previously demonstrated that offspring from PPAC male mice have smaller ocular sizes compared to controls.36 In our previous and current PPAC studies, occasionally, mice born to PPAC males from different litters had one eye (Fig. 1B) unlike the control offspring born with two normal eyes. The “missing eyes” of these PPAC-offspring never fully developed, which shows a paternal contribution to microphthalmia in offspring subjected to preconception alcohol exposure. Data from PPAC-offspring with one eye was excluded from the following studies, because the frequency of single-eye-offspring occurrence was low, and we aimed to compare potential differences between both eyes for each experimental condition.

PPAC Affects the Retinal Light Responses in the Offspring

Some altered facial features in FASD patients might improve over time,37 because their appearances would look normal by middle age. However, cases of reported myopia persist throughout adulthood.38 We examined whether there was a potential deficit in retinal function in PPAC-offspring, and whether these functional deficits would persist into adulthood. At two, four, and six months old, the dark-adapted retinal light responses of the control and PPAC-offspring mice were recorded by ERG.

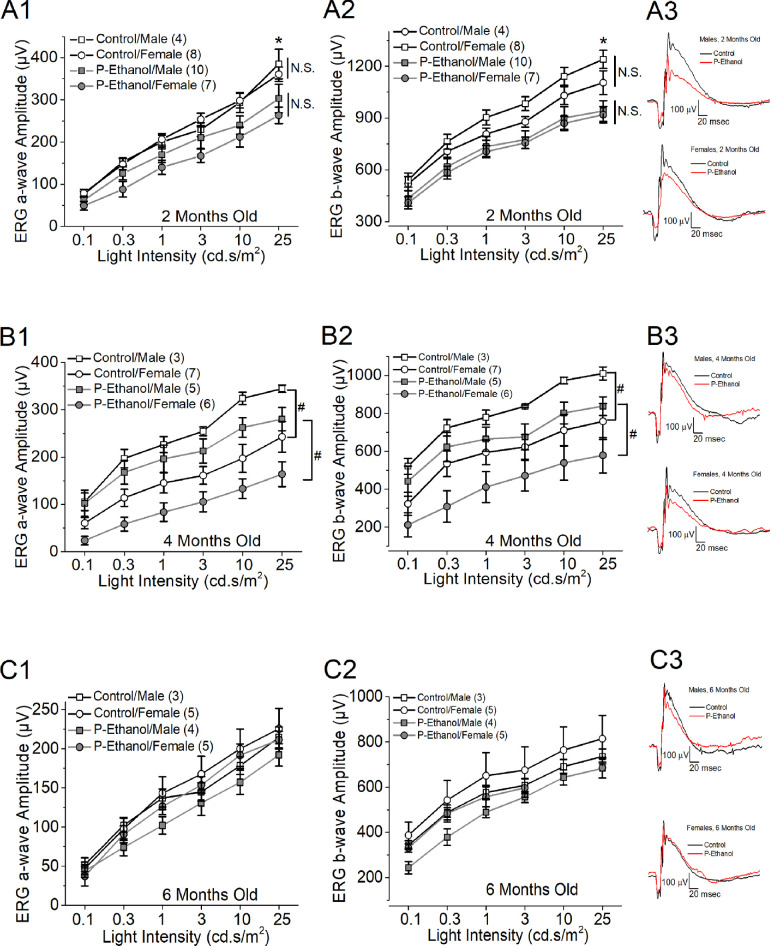

We first compared the ERG responses from the left and right eyes within each experimental group for all age groups at different light intensities and found no statistical differences, so ERG recordings from both eyes were averaged for every mouse as n = 1. Overall, at two months old (Figs. 2A1, 2A2), PPAC-offspring (P-Ethanol) had smaller ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes at the highest stimulating light intensity (25 cd.s/m2) compared to the control (Control; two-way ANOVA: treatments and sexes; P < 0.05), and there was no sex difference (N.S.) in retinal light responses. At four months old (Figs. 2B1, 2B2), the PPAC-offspring exhibited smaller ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes than the controls at all stimulating light intensities and females had significantly smaller light responses compared to males in both treatment groups (P < 0.05; two-way ANOVA: treatments and sexes). At six months old (Figs. 2C1, 2C2), there was no statistical difference between PPAC-offspring and the control nor males compared to females, even though PPAC-offspring had smaller ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes at all stimulating light intensities. We did not observe any statistical differences in ERG a- and b-wave implicit times between the control and PPAC-offspring in all ages (ERG waveforms shown in Figs. 2A3, 2B3, and 2C3).

Figure 2.

PPAC decreased retinal light responses in their offspring. Dark-adapted ERG responses with a series of light flashes (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 25 cd ∙ s/m2) were recorded in control and PPAC-offspring mice at two (A1 and A2), four (B1 and B2), and six (C1 and C2) months old. Each group has three to 10 mice (n = 3–10) as denoted in each panel. (A1 and A2) At two months old, the ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes are significantly lower in PPAC-offspring mice (P-Ethanol) than the control mice (Control). *: indicates a statistical difference (P < 0.05) between the control and P-Ethanol at 25 cd ∙ s/m2 light intensity. There is no statistical difference (N.S.) between male and female mice. (A3) Representative ERG waveforms recorded from two months old mice at 25 cd ∙ s/m2 light intensity. Black line: control; red line: P-Ethanol. (B1 and B2) At four months old, there is a statistical difference between male and female mice (#: P < 0.05). (B3) Representative ERG waveforms recorded from four-month-old mice at 25 cd ∙ s/m2 light intensity. Black line: control; red line: P-Ethanol. (C1 and C2) At six months old, there is no statistical difference among the four groups. (C3) Representative ERG waveforms recorded from six-month-old mice at 25 cd ∙ s/m2 light intensity. Black line: control; red line: P-Ethanol. Two-way ANOVA (factor a: light intensities; factor b: four experimental groups), P < 0.05.

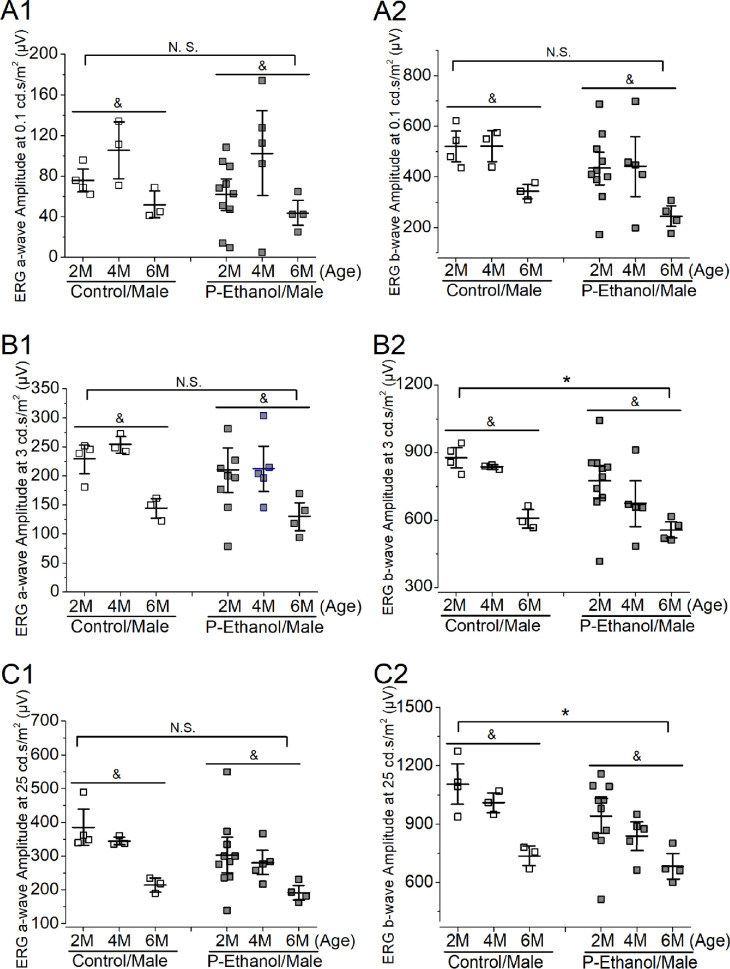

As we observed a sex difference in retinal light responses in 4-months old offspring, we further independently analyzed the ERG responses in males (Fig. 3) and females (Fig. 4) for both treatment groups (PPAC-offspring versus controls) across all ages at three different stimulating light intensities (0.1, 3, and 25 cd ∙ s/m2) using two-way ANOVA (treatments and ages). In males, aging had a significant impact on the retinal light responses, as the six-month-old mice (6M) had lower ERG responses than two- or four-month-old (2M or 4M) in both control and PPAC-offspring (P < 0.05). Interestingly, PPAC did not appear to have an impact on the photoreceptor light responses, as there was no statistical difference (N.S.) between PPAC-offspring and the control measured by ERG a-waves at three different stimulating light intensities (Figs. 3A1, 3B1, 3C1), but PPAC significantly decreased the inner retinal light responses as measured by ERG b-waves at higher stimulating light intensities (3 and 25 cd ∙ s/m2; P < 0.05). There was no cross-interaction between the treatments and ages meaning PPAC did not affect or worsen the aging effects in retinal light responses, and aging did not cause PPAC-offspring to have smaller retinal light responses.

Figure 3.

The effect of PPAC on retinal light responses of male offspring-mice. Dark-adapted ERG recordings of male mice across two, four, and six months old at 0.1 (A1 and A2), 3 (B1 and B2), and 25 (C1 and C2) cd ∙ s/m2 light intensities were further analyzed using two-way ANOVA (factor a: age; factor b: control vs. PPAC-offspring; P < 0.05). (A1 and A2) At 0.1 cd ∙ s/m2 light intensity, there is no statistical difference (N.S.) between the control and PPAC-offspring mice (P-Ethanol) in ERG a-wave (A1) and ERG b-wave (A2). There is an age difference (&) between two, four, and six months old (2M, 4M, and 6M) in both ERG a- (A1) and b- (A2) waves. (B1 and B2) At 3 cd ∙ s/m2, there is a statistical difference between the control and PPAC-offspring (P-Ethanol) in ERG b-wave (B2). There is an age difference (&) between two, four, and six months old in both ERG a- (B1) and b- (B2) waves. (C1 and C2) At 25 cd ∙ s/m2, there is a statistical difference between the control and PPAC-offspring (P-Ethanol) in ERG b-wave (C2). There is an age difference (&) between two, four, and six months old in both ERG a- (C1) and b- (C2) waves.

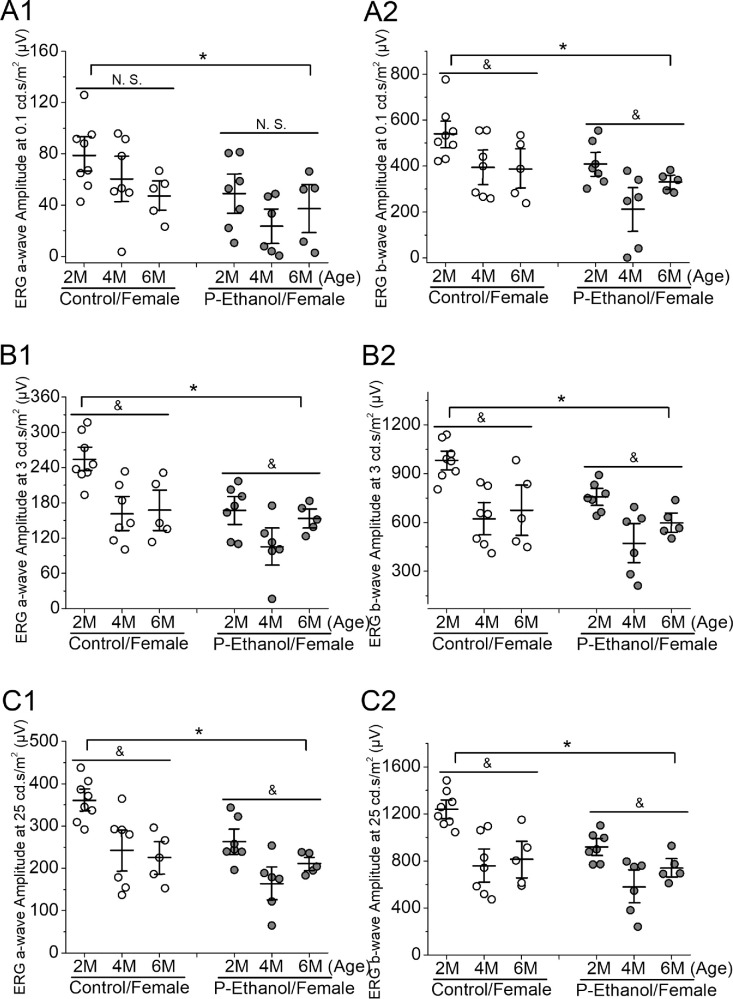

Figure 4.

The effect of PPAC on retinal light responses of female offspring-mice. Dark-adapted ERG recordings of female mice across two, four, and six months old at 0.1 (A1 and A2), 3 (B1 and B2), and 25 (C1 and C2) cd ∙ s/m2 light intensities were further analyzed using two-way ANOVA (factor a: age; factor b: control vs. PPAC-offspring; P < 0.05). (A1 and A2) At 0.1 cd ∙ s/m2 light intensity, there is a statistical difference (asterisk) between the control and PPAC-offspring mice (P-Ethanol) in ERG a-wave (A1) and ERG b-wave (A2). There is an age difference (&) between two, four, and six months old (2M, 4M, and 6M) in ERG b-wave (A2) but not a-wave (A1; N.S.). (B1 and B2) At 3 cd ∙ s/m2, there is a statistical difference between the control and PPAC-offspring (P-Ethanol) in both ERG a- (B1) and b- (B2) waves. There is an age difference (&) between two, four, and six months old in both ERG a- (B1) and b- (B2) waves. (C1 and C2) At 25 cd ∙ s/m2, there is a statistical difference between the control and PPAC-offspring (P-Ethanol) in ERG a- (C1) and b- (C2) waves. There is an age difference (&) between two, four, and six months old in both ERG a- (C1) and b- (C2) waves.

As for female mice (Fig. 4), PPAC had a significant impact on the retinal light responses in the offspring (P-Ethanol) compared to the controls (Control) in all three stimulating light intensities (P < 0.05). Aging had some impacts on all female mice regardless of the treatments, since all 2 months old female mice had significantly higher ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes than the 4 or 6 months old (P < 0.05). There was no cross-interaction between the treatments and ages, so PPAC did not impact the aging effects, and aging did not worsen PPAC-caused smaller retinal light responses of females.

Overall, it appears that PPAC might adversely impact female offspring (P-Ethanol/ Female; Fig. 4) more than male offspring (P-Ethanol/Male; Fig. 3). At all light intensities, ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes were smaller in PPAC-female offspring than the control females (Fig. 4), whereas PPAC-male offspring only had significantly smaller ERG b-wave amplitudes compared to the male controls only at the higher stimulating light intensities (Fig. 3). Interestingly, in males, the ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes recorded from the 6 months old mice were smaller than those recorded from the two- and four-month-old mice irrespective of treatments, whereas the a- and b-wave amplitudes recorded at both four and six months were similar in females. Thus aging might have differential impacts on retinal light responses in males versus females devoid of the PPAC influence. There was no statistical difference of ERG a- and b-wave implicit times between PPAC and control offspring, as well as males versus females across all light intensities (two-way ANOVA; data not shown), suggesting that PPAC did not impact the offspring in the response times to light flashes.

PPAC Affects Retinal Thicknesses in the Offspring

As microphthalmia is characteristic of some FASD children,13 we next examined whether the histological features of the neural retina were altered by PPAC. We measured the total neural retinal thickness (from the outer/inner photoreceptor segment to the retinal nerve fiber layer) and various retinal layers (Fig. 5). There was no statistical difference between males and females, so we combined the data from both sexes for each treatment group. The total retinal thickness was statistically different between PPAC-offspring and controls in central (Fig. 5A1) and peripheral (Fig. 5A2) retinal areas (P < 0.05). There is a significant difference in retinal thickness between two- and six-month-old mice (P < 0.05).

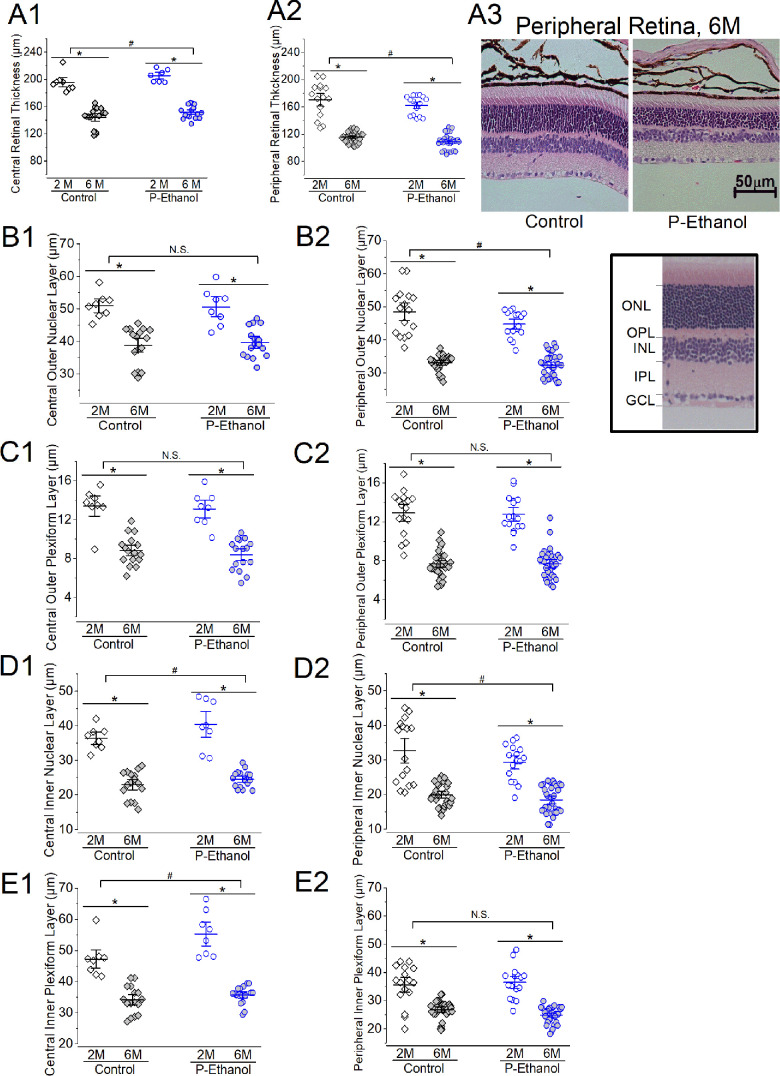

Figure 5.

The effect of PPAC on the morphology of the retinal layers. Mouse retinal sections (4 µm) from two (2M) and six months old (6M) of the control (Control) and PPAC-offspring mice (P-Ethanol) were processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and the thickness of various retinal layers were measured. The central (A1, B1, C1, D1, and E1) and peripheral (A2, B2, C2, D2, and E2) retinas were concurrently analyzed. Two-way ANOVA (factor a: Control vs. P-Ethanol; factor b: 2M vs. 6M) with P < 0.05 was used for statistical analysis. Three sections of the same eye were averaged because n = 1, and each group had at least two eyes from three mice (n = 6). (A1 and A2) There is a statistical difference between Control and P-Ethanol (pound sign), as well as age (asterisk) in the total retinal thickness measured from the central (A1) and peripheral (A2) retina. (A3) Representative photographs of H&E-stained retinal sections taken from the peripheral retinas of the Control and P-Ethanol mice at six months (6M) old. Scale bar: 50 µm. (B1 and B2) There is no statistical difference (N.S.) between Control and P-Ethanol in the central ONL (B1), but it is significant (pound sign) in the peripheral ONL (B2). There is a statistical difference of the ONL measured in the central (B1) and peripheral (B2) retina between ages (asterisk). (Insert) A representative retinal section with labeled ONL, OPL, INL, IPL, and the ganglion cell layer (GCL). (C1 and C2) Although there is a statistical difference in OPL between two and six months old (asterisk), there is no statistical difference between Control and P-Ethanol in central (C1) and peripheral (C2) OPL. (D1 and D2) There is a statistical difference in INL between Control and P-Ethanol (pound sign) and between two and six months old (asterisk) measured in the central (D1) and peripheral (D2) retina. (E1 and E2) There is a statistical difference in IPL between Control and P-Ethanol (pound sign) in the central (E1) but not peripheral (E2) retina. There is a statistical difference in IPL between two and six months old (asterisk) measured in the central (E1) and peripheral (E2) retina.

We further measured the central and peripheral retinal layers including ONL (Figs. 5B1, 5B2), OPL (Figs. 5C1, 5C2), INL (Figs. 5D1, 5D2), and IPL (Figs. 5E1, 5E2). When comparing the thicknesses of different retinal layers between the two- (2M) and six-month-old (6M) mice, aging caused significant retinal thinning in all layers measured in controls (Control) and PPAC-offspring (P-Ethanol; P < 0.05). In the central retina, PPAC elicited significant changes in the INL and IPL layers of its offspring (P-Ethanol) compared to the control (Figs. 5D1, 5E1; P < 0.05). In the peripheral retina, PPAC elicited statistical differences in the ONL and INL compared to the control (Figs. 5B2, 5D2; P < 0.05). It appears that PPAC had more impacts in the inner retina (INL and IPL) than the outer retina (ONL and OPL) of the offspring. However, there was no statistical difference between the control and PPAC-offspring of 6 months old mouse retinas in either the total thickness or the thickness of various layers. There was no cross-interaction between treatments and aging. Thus aging might have stronger effects on retinal thinning than PPAC throughout mid-adulthood.

Discussion

This is the first study that investigates the effect of PPAC on neural retinal function and morphometrics of PPAC-offspring mice. Microphthalmia is a commonly reported gross ocular defect in FASD9,11,13 and has since been listed as a diagnostic criterion of FASD.39 Although microphthalmia can manifest either unilaterally or bilaterally,40,41 we previously reported that there is a strong tendency for the right eyes to be smaller than the left in PPAC-offspring mice,22 bearing resemblance to the microphthalmia phenotype frequently observed in the right eyes of FASD mice after in utero exposure to alcohol.42 The underlying mechanism of such asymmetry and pronounced susceptibility of the right eyes in FASD mice43,44 remains unknown. In this study, we observed a few adult PPAC-offspring mice (Fig. 1) with a single eye, in which one eye was not fully developed and was recessed in the eye socket. The occurrence of single-eyed PPAC-offspring mice was infrequent (fewer than one pup per two or three litters), so we did not include these mice in the following studies (Figs. 234–5).

PPAC appears to have more adverse impacts on female offspring retinal light responses than the male offspring (Figs. 23–4). In male mice, while there was an age-dependent difference in retinal light responses, PPAC did not have a significant impact on the photoreceptor light responses (ERG a-waves; Figs. 3A1, 3B1, and 3C1). But in female mice, PPAC adversely affected the photoreceptor light responses in PPAC-offspring compared to the control (Figs. 4A1, 4B1, 4C1). PPAC significantly decreased inner retinal light responses (ERG b-waves) when the light intensities were at mesopic (3 cd ∙ s/m2) and photopic (25 cd ∙ s/m2) conditions in PPAC-male offspring (Figs. 3B2, 3C2), but in females, PPAC elicited a decline in ERG b-waves even under scotopic (0.1 cd ∙ s/m2) conditions (Figs. 4A2, 4B2, 4C2). Thus PPAC adversely affects the inner retinal physiology (shown in ERG b-wave) more than the photoreceptors in the offspring of both sexes. Interestingly, in our morphological analyses of the various retinal layer thicknesses, it appears that PPAC has more impacts in the inner retina (INL and IPL) than the outer retina (ONL and OPL) of the offspring. This observation echoes previous reports that the inner retina might be more vulnerable or sensitive to environmental insults45,46 than the outer retina. There was a sex difference in PPAC-elicited impacts on their offspring shown in our ERGs. This result points to the possibility that females might be more susceptible to prenatal and perinatal alcohol stress than males. As previously reported, female FASD children show profound cognitive impairment and dysmorphia compared to males at age seven.47

In FASD patients, the neural retina is the most susceptible tissue to the negative impact of ethanol among other FASD-associated ocular abnormalities.13 Neurogenesis of the neural retina is critical for the development of the whole eye.14,48–50 As a teratogen, direct exposure to ethanol affects the morphogenesis of optic vesicles thus interferes with neural retina formation.51 However, unlike most FASD mouse studies in which the pregnant mice or pups had direct alcohol-exposure, the PPAC-offspring mice were never exposed to ethanol in utero or postnatally. We previously showed that the sperms of ethanol-exposed male mice have epigenetic modifications,52,53 resulting in PPAC-fetuses with smaller placenta21,25,52 and abnormal liver metabolism.54 Here, we have further unveiled that PPAC not only impacts the fetus and early development but transcends into adulthood.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated in this study that PPAC has adverse impacts on offspring during early development18,19,22–25,36,52,55 and in adulthood. Paternal drinking prior to conception could cause congenital ocular defects in children and to a larger extent, craniofacial dysmorphia and growth deficits. As we showed that PPAC negatively affects the retinal light responses of its offspring even in early adulthood, it implies that PPAC could cause vision problems in their school-age children to young adults and impact their learning and early career development. Hence, FASD is not only linked to maternal alcohol use, and the health-advisory warning of the negative impacts of alcohol consumption should be broadened to include both parents and extended to preconception paternal alcohol consumption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alexander Patawaran and Jenivi Tham for assisting in data analyses.

Supported in part by NIHR21EY031813 from the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to G. Y.-P. K. and NIHR01AA028219 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of NIH to M.C.G.

Disclosure: K. Owusu-Ansah, None; K.N. Thomas, None; K. Cox, None; D.L. Pham, None; W.-L. Chen, None; M.L. Ko, None; M.C. Golding, None; G.Y.-P. Ko, None

References

- 1. Center for Disease Control And Prevention (CDC). Data & Statistics on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/fasd/data/index.html. Accessed September 10, 2024.

- 2. May PA, Hasken JM, de Vries MM, et al.. Maternal and paternal risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Alcohol and other drug use as proximal influences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2023; 47: 2090–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naimi TS, Lipscomb LE, Brewer RD, Gilbert BC.. Binge drinking in the preconception period and the risk of unintended pregnancy: Implications for women and their children. Pediatrics. 2003; 111(suppl 1): 1136–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou Q, Song L, Chen J, et al.. Association of Preconception Paternal Alcohol Consumption With Increased Fetal Birth Defect Risk. JAMA Pediatr. 2021; 175: 742–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rompala GR, Homanics GE.. Intergenerational effects of alcohol: a review of paternal preconception ethanol exposure studies and epigenetic mechanisms in the male germline. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019; 43: 1032–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terracina S, Ferraguti G, Tarani L, et al.. Transgenerational abnormalities induced by paternal preconceptual alcohol drinking: findings from humans and animal models. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2022; 20: 1158–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Golding MC. Teratogenesis and the epigenetic programming of congenital defects: why paternal exposures matter. Birth Defects Res. 2023; 115: 1825–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rice RC, Gil DV, Baratta AM, et al.. Inter- and transgenerational heritability of preconception chronic stress or alcohol exposure: translational outcomes in brain and behavior. Neurobiol Stress. 2024; 29: 100603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strömland K. Ocular involvement in the fetal alcohol syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1987; 31: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Altman B. Fetal alcohol syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol. 1976; 13: 255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan T, Bowell R, O'Keefe M, Lanigan B. Ocular manifestations in fetal alcohol syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991; 75: 524–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hug TE, Fitzgerald KM, Cibis GW.. Clinical and electroretinographic findings in fetal alcohol syndrome. J AAPOS. 2000; 4: 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Strömland K, Pinazo-Durán MD.. Ophthalmic involvement in the fetal alcohol syndrome: clinical and animal model studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002; 37: 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kashyap B, Frederickson LC, Stenkamp DL.. Mechanisms for persistent microphthalmia following ethanol exposure during retinal neurogenesis in zebrafish embryos. Vis Neurosci. 2007; 24: 409–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katz LM, Fox DA.. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters scotopic and photopic components of adult rat electroretinograms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991; 32: 2861–2872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Golding MC. Paternal alcohol use contributes to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder growth & metabolic defects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2021; 45: 32A–32A. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chang RC, Skiles WM, Chronister SS, et al.. DNA methylation-independent growth restriction and altered developmental programming in a mouse model of preconception male alcohol exposure. Epigenetics. 2017; 12: 841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang RC, Wang H, Bedi Y, Golding MC.. Preconception paternal alcohol exposure exerts sex-specific effects on offspring growth and long-term metabolic programming. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2019; 12(1): 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bedi Y, Chang RC, Gibbs R, Clement TM, Golding MC.. Preconception paternal alcohol exposure alters the sperm noncoding RNA content and leads to fetal growth restriction. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2020; 44: 195–195. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas KN, Zimmel KN, Roach AN, et al.. Maternal background alters the penetrance of growth phenotypes and sex-specific placental adaptation of offspring sired by alcohol-exposed males. FASEB J. 2021; 35(12): e22035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas KN, Zimmel KN, Basel A, et al.. Paternal alcohol exposures program intergenerational hormetic effects on offspring fetoplacental growth. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022; 10: 930375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomas KN, Srikanth N, Bhadsavle S, et al.. Preconception paternal ethanol exposures induce alcohol-related craniofacial growth deficiencies in fetal offspring. J Clin Invest. 2023; 133(11): e167624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Srikanth N, Thomas K, Bhadsavle S, et al.. Paternal alcohol exposure induces alcohol-related craniofacial defects. APHA 2023 Annual Meeting and Expo. 2023.

- 24. Thomas KN, Roach AR, Thomas KR, Basel A, Golding MC.. Developmental toxicity of dual parental alcohol consumption and the long-term effects of offspring growth, craniofacial, and neurological development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2022; 46: 47A–47A. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhadsavle SS, Golding MC.. Paternal epigenetic influences on placental health and their impacts on offspring development and disease. Front Genet. 2022; 13: 1068408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chang RC, Thomas KN, Bedi YS, Golding MC.. Programmed increases in LXRα induced by paternal alcohol use enhance offspring metabolic adaptation to high-fat diet induced obesity. Mol Metab. 2019; 30: 161–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jarmasz JS, Basalah DA, Chudley AE, Del Bigio MR.. Human brain abnormalities associated with prenatal alcohol exposure and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017; 76: 813–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suttie M, Foroud T, Wetherill L, et al.. Facial dysmorphism across the fetal alcohol spectrum. Pediatrics. 2013; 131(3): e779–e788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoyme HE, Kalberg WO, Elliott AJ, et al.. Updated clinical guidelines for diagnosing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2016; 138(2): e20154256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC.. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav. 2005; 84: 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adler ID. Comparison of the duration of spermatogenesis between male rodents and humans. Mutat Res. 1996; 352(1–2): 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whitten WK, Bronson FH, Greenstein JA.. Estrus-inducing pheromone of male mice: transport by movement of air. Science. 1968; 161(3841): 584–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yu F, Chapman S, Pham DL, Ko ML, Zhou B, Ko GYP.. Decreased miR-150 in obesity-associated type 2 diabetic mice increases intraocular inflammation and exacerbates retinal dysfunction. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020; 8(1): e001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim AJ, Chang JYA, Shi L, Chang RCA, Ko ML, Ko GYP.. The effects of metformin on obesity-induced dysfunctional retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58: 106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shi L, Kim AJ, Chang RCA, et al.. Deletion of miR-150 exacerbates retinal vascular overgrowth in high-fat-diet induced diabetic mice. PLoS One. 2016; 11(6): e0157543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thomas KN, Srikanth N, Bhadsavle SS, et al. Preconception paternal ethanol exposures induce alcohol-related craniofacial growth deficiencies in fetal offspring. J Clin Invest. 2023; 133(11): e167624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Spohr HL, Willms J, Steinhausen HC.. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in young adulthood. J Pediatr. 2007; 150: 175–179, 179.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gyllencreutz E, Aring E, Landgren V, Svensson L, Landgren M, Grönlund MA.. Ophthalmologic findings in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders—a cohort study from childhood to adulthood. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020; 214: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosett HL. A clinical perspective of the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1980; 4: 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Williamson KA, FitzPatrick DR.. The genetic architecture of microphthalmia, anophthalmia and coloboma. Eur J Med Genet. 2014; 57: 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harding P, Moosajee M.. The molecular basis of human anophthalmia and microphthalmia. J Dev Biol. 2019; 7(3): 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parnell SE, Dehart DB, Wills TA, et al.. Maternal oral intake mouse model for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: ocular defects as a measure of effect. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006; 30: 1791–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cook CS, Nowotny AZ, Sulik KK.. Fetal alcohol syndrome. Eye malformations in a mouse model. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987; 105: 1576–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tyndall DA, Cook CS.. Spontaneous, asymmetrical microphthalmia in C57B1/6J mice. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1990; 10: 353–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pardue MT, Barnes CS, Kim MK, et al.. Rodent Hyperglycemia-Induced Inner Retinal Deficits are Mirrored in Human Diabetes. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2014; 3(3): 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim MK, Aung MH, Mees L, et al.. Dopamine deficiency mediates early rod-driven inner retinal dysfunction in diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. May PA, Tabachnick B, Hasken JM, Marais AS, de Vries MM, Barnard R, et al.. Who is most affected by prenatal alcohol exposure: boys or girls? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017; 177: 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stenkamp DL, Frey RA, Mallory DE, Shupe EE.. Embryonic retinal gene expression in sonic-you mutant zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2002; 225: 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hyer J, Kuhlman J, Afif E, Mikawa T.. Optic cup morphogenesis requires pre-lens ectoderm but not lens differentiation. Dev Biol. 2003; 259: 351–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li Z, Hu M, Ochocinska MJ, Joseph NM, Easter SS Jr. Modulation of cell proliferation in the embryonic retina of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Dev Dyn. 2000; 219: 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kennelly K, Brennan D, Chummun K, Giles S.. Histological characterisation of the ethanol-induced microphthalmia phenotype in a chick embryo model system. Reprod Toxicol. 2011; 32: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bedi YS, Thomas KN, Golding MC.. Preconception paternal alcohol exposures, epigenetic programming of sperm, and the induction of fetal-placental growth defects. Birth Defects Res. 2022; 114: 419–419. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bedi Y, Chang RC, Gibbs R, Clement TM, Golding MC.. Alterations in sperm-inherited noncoding RNAs associate with late-term fetal growth restriction induced by preconception paternal alcohol use. Reprod Toxicol. 2019; 87: 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Basel A, Bhadsavle S, Thomas KN, et al.. Abstract 6458: Maternal and paternal alcohol exposures program higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in offspring. Cancer Res. 2023; 83(Suppl 7): 6458–6458. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thomas K, Golding M.. Paternal alcohol consumption as a modulator of FASD in a mouse model. Physiology (Bethesda). 2023; 38(S1): 5780717. [Google Scholar]