Abstract

Introduction

Digital health literacy is integral to accessing reliable information, especially for students making informed health decisions. This study aims to assess the digital health literacy level as well as sociodemographic factors of students of universities in Asadabad County, Hamadan, Western Iran.

Methods

The present research was a descriptive-cross-sectional study conducted between May to June 2024. The statistical population included 500 students from the following Iranian universities in Asadabad county: Islamic Azad University, Payame Noor University, Technical and Vocational College, and Asadabad School of Medical Sciences. The van der Vaart Digital Health Literacy Scale was used for data collection.

Results

The study showed that students’ digital health literacy status is moderate (47.19 ± 8.34). In the dimensions of digital health literacy, operational skills (61.84 ± 32.97) were at a desirable level, with the most significant issues related to privacy protection (23.51 ± 21.72). The mean digital health literacy score of students of Medical Sciences University was significantly higher than Azad University (P < 0.001) but lower than Technical and Vocational University (P = 0.048). There was a significant relationship between digital health literacy and the variables of the university of study (p < 0.001), gender (p = 0.049), education level (p = 0.017), nativity status (p = 0.001), and residence status (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The results of the present study revealed that the digital health literacy of students in Iran was moderate, depending on sociodemographic factors. The findings from this study can be used to develop and implement interventions and strategies to improve digital health literacy.

Keywords: Digital health literacy, Health literacy, Student, Cross-sectional study

Introduction

Today, health literacy is recognized as a significant public health issue that plays an essential role in improving health equity [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), health literacy refers to “the personal characteristics and social resources needed by individuals and communities to access, understand, evaluate, and use information and services for health-related decision-making” [2]. With the advancement of technology, the sources for obtaining health-related information [3]have shifted from traditional media (radio, television, magazines, bestselling books, etc.) to digital media [4]. The use of health information technology has given rise to the concept of digital health literacy (DHL) [5]. Digital health literacy (DHL), also known as electronic health literacy, involves using the internet to access, understand, and evaluate health-related information to address health issues [6].

Digital health literacy is an important and evolving concept that can lead to optimistic transformations in health outcomes [7]. It encompasses unique skills, including traditional literacy, health literacy, information literacy, scientific literacy, media literacy, and computer literacy, to navigate health-related care in the age of technology [3, 8]. Moreover, due to its role in optimizing the health of individuals, digital health literacy is crucial in reducing health inequalities on a larger scale [9]. Individuals who use the Internet and have more digital skills may be more motivated to utilize health-related resources and digital health services [10]. According to international studies, inadequate digital health literacy has been shown to reduce the use of healthcare services, lower the ability to make health-related decisions, and increase the likelihood of poorer health outcomes overall [3, 11, 12]. Based on the study by Cheng et al., individuals with higher digital health literacy are more competent in searching for and finding suitable, reliable, and health-related information compared to those with lower digital health literacy [13].

The academic community widely relies on the Internet for access to scientific and medical websites as well as national and international databases, making them dependent on Internet resources [14]. Students represent a significant portion of the population and are expected to possess a high level of knowledge about health issues [13]. Digital health literacy empowers students to utilize emerging technologies, enhancing the quality of healthcare delivery [15]. With the digitization of medical information, students need the ability to evaluate and differentiate between inaccurate and efficient information in order to apply information effectively [16]. Research on students’ digital health literacy remains limited. According to O’Doherty et al. [17]،, students demonstrated high proficiency in searching for information online and engaging in social programs on digital platforms. In the study by Rathnayake et al. [18], nearly half of the students (49.4%) had inadequate digital health literacy skills. Another study reported that medical students’ digital health literacy skills were also poor (53.2%) [19]. Without sufficient digital health literacy, accessing a large volume of information can lead to confusion [3]. The abundance of information generated through the internet, which includes inaccurate health data, can interfere with an individual’s ability to make informed health decisions [20]. The results of other studies [21, 22] point to the existence of a digital divide, indicating that sociodemographic factors can affect individuals’ access to the internet for health-related information searches. According to the Model of eHealth Use Integrative [23], demographic characteristics (such as education, age, gender, income, and internet usage features like having a personal electronic device) influence digital health literacy. Based on this model, social structural inequalities contribute to healthcare disparities through digital health literacy [3]. Understanding the relationship between digital health literacy and sociodemographic factors may help evaluate and implement digital interventions, ultimately reducing health disparities [12, 21].

The results of studies by Estrela et al. [21], Shi [24], and Lwin et al. [25]suggest that factors such as income level, education, age, gender, and marital status are associated with digital health literacy. According to the findings of De Santis et al. [26] and Choi et al. [27], younger individuals with higher education levels have better health-related digital health literacy. Conversely, adults with lower education levels may face comprehension barriers when searching for health information [28]. Another study [29] reported that men had lower digital health literacy scores than women, however studies by Tran et al. [30] and Huang et al. [31], showed that male students had higher digital health literacy scores than female students. Additionally, previous studies [32, 33] have shown that higher digital health literacy scores were associated with greater income levels. In one study, occupation and marital status significantly impacted digital health literacy [34].

Given that a large number of internet users are students, and there is a higher probability of students being youths, concerns were raised regarding the physical, mental, and social health of the next generation in the country [35]. Digital health literacy is crucial, serving as a significant step toward empowering individuals, youth, and students to manage their health and make autonomous health-related decisions. Therefore, research on digital health literacy is necessary to understand students’ adaptation to digital technology and their use of digital healthcare resources [36]. Accordingly, the present study aimed to assess the digital health literacy level as well as sociodemographic factors of students of universities in Asadabad County, Hamadan, Western Iran. The findings from this study will help develop educational strategies and interventions to enhance students’ digital health literacy.

Methods

Study design

This research was a descriptive-cross-sectional study conducted between May to June 2024 among all students from universities in Asadabad county [comprising Islamic Azad University (550 students), Payame Noor University (300 students), Asadabad Technical and Vocational College (300 students), and Asadabad School of Medical Sciences (250 students)].

Samples

To determine the sample size, the formula for estimating the mean ( ) was used, where S is the standard deviation of the digital health literacy score, which was 5.02 in the study by Turan et al. [36]. The square of the 95th percentile of the normal distribution is 3.84, and d represents the margin of error, or the difference considered for estimating the mean, which is 0.44. After substituting these values into the formula, the sample size for this study was calculated to be 500 participants.

) was used, where S is the standard deviation of the digital health literacy score, which was 5.02 in the study by Turan et al. [36]. The square of the 95th percentile of the normal distribution is 3.84, and d represents the margin of error, or the difference considered for estimating the mean, which is 0.44. After substituting these values into the formula, the sample size for this study was calculated to be 500 participants.

Data was collected from 500 students enrolled in associate, bachelor’s, master’s, and higher degree programs in the universities of Asadabad county using stratified random sampling proportional to the population size. In this way, each of the universities was considered as a stratum, and then several students (proportionate to the number of students of that university) were randomly selected from each stratum (university). Of these, 198 students (39.6%) were from Islamic Azad University, 104 students (20.8%) from Payame Noor University Asadabad, 108 students (21.6%) from Technical and Vocational College, and 90 students (18%) from Asadabad School of Medical Sciences. Students at each university were selected randomly. This was done by visiting the education office of each college, obtaining a list of students, and then randomly selecting a specific number of individuals. These students were contacted and invited to participate in the study. If a student was unavailable or unwilling to participate, another individual was randomly chosen as a replacement. Inclusion criteria included: being enrolled in one of the universities or colleges in Asadabad county at the time of the study and consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criterion was incomplete questionnaires.

Measures

Demographic information

The demographic information of the students included university, gender, education level, marital status, nativity status, residence, duration of computer use, and satisfaction with financial status.

Digital health literacy instrument (DHL)

A pre-designed standard questionnaire by Van Der Vaart and Drossaert (2017) was used to assess DHL for this study [37]. This questionnaire is designed to evaluate DHL and has previously been validated in various populations and countries [38, 39]. The questionnaire comprises 21 questions and seven subscales, each with three items. The subscales are:

Operational skills

Using a computer keyboard or mouse, using buttons or links and hyperlinks on websites.

Navigation skills

Losing track on a website or the internet, knowing how to return to the previous page, clicking on something and seeing something different from what was expected,

Information search

Choosing from all the information found, using appropriate words or search phrases to find the desired information, finding the precise information needed,

Evaluating reliability

Deciding whether the information is reliable, deciding whether the information is written with commercial interests, checking different websites to see if they provide the same information,

Determining data relevancy

Deciding on the usefulness of the information found, using the information found in daily life, using the information found to make health decisions,

Adding content

Clearly formulating a health-related question or concern, expressing opinions, thoughts, or feelings in writing, writing a message, and

Protecting privacy

Judging who can share private information with reading, sharing others’ private information.

This questionnaire has 21 questions and seven domains (each with three questions) including Operational skills, determining data relevancy, evaluating data reliability, Information searching, adding content, protecting privacy and Navigation skills. Items related to the five areas of operational skills, establishing relevance, assessing reliability, searching for information, adding content by a 4-point Likert scale (from “very difficult” = 1 to “very easy” = 4), and items related to two The extent of privacy protection and orientation skills were scored on a 4-point scale (from “never” = 1 to “always” = 4) [40]. Finally, the grades of all areas and the overall grade were transferred to the range of zero to 100 and analyzed. Skills are rated as very undesirable for an average of less than 20.0% of the total score, undesirable between 21.0% and 40.0%, intermediate between 41.0% and 60.0%, desirable between 61.0% and 80.0%, and very desirable between 81.0% and 100.0% [38]. In the study by Van Der Vaart and Drossaert, the DHL tool showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87, indicating acceptable reliability [37]. Additionally, in the study by Alipour et al. among healthcare workers in teaching hospitals in southeast Iran, the validity and reliability of this questionnaire were achieved with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.98 for the overall scale [38]. A pilot study involving 25 individuals who met the study’s inclusion criteria further confirmed all questionnaire sections’ clarity and applicability. In addition, internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha for Operational skill, determining data relevancy, evaluating data reliability, Information searching, adding content, protecting privacy and Navigation skills, yielding satisfactory values of 0.91, 0.89, 0.82, 0.85, 0.85, 0.71, and 0.73, the for Scales of DHL questionnaire, respectively. Also, for the entire questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.92 was obtained.

Data collection

After approval from the ethics committee and obtaining permission from the university’s research vice-chancellor, coordination with the selected universities was carried out. The researchers introduced themselves and obtained consent from the research units to participate in the study. The study’s objectives were explained to the samples. They were included in the study if they met all the inclusion criteria and provided written informed consent. According to the introductory explanation of the questionnaire, participation in the study was voluntary, and students could withdraw from the study at any time without completing the questionnaire. Additionally, the researchers explained the anonymity and confidentiality of the questionnaires and requested that the research units accurately answer all questions.

Data analysis

After data collection, SPSS24 software was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, standard deviation, mean, and percentage, were used to describe the demographic characteristics of the samples. The normality assumption for all variables was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and skewness and kurtosis indices, the variables whose indices were in the range of -1 to 1 were considered as normal. Independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA were then used to compare the mean scores of various dimensions of digital health literacy across different qualitative variables. The impact of various variables on the digital health literacy score was also assessed using multiple linear regression models. A significance level of less than 0.05 was considered for this study.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved and adhered to by the ethics committee of Asadabad School of Medical Sciences with the ethical code (IR.ASAUMS.REC.1403.009). Oral and written consent was obtained from samples based on the recommendations approved by the ethics committee. Samples were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time if they wished. Additionally, all samples were involved in the research process, and their information was kept confidential.

Results

Demographics

In this study, 500 students from four universities in the city of Asadabad participated. The majority of the students were female (305 students, 61%), and most of the students (245 students, 49.00%) were enrolled in associate’s degree programs. 380 students (76%) were single, and 280 students (56%) were native to Asadabad. The frequency distribution of the samples based on various variables such as university, gender, level of education, marital status, native status, place of residence, Duration of computer use (hours), and satisfaction with financial status is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of mean digital literacy scores on different levels of qualitative variables among students participating in the study

| Variable | Levels | N (%) | Mean | Standard Deviation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 305 (61.0) | 48.44 | 17.79 | 0.049* |

| Male | 195 (39.0) | 44.95 | 21.42 | ||

| Education | Associate’s Degree | 245 (49.0) | 48.81 | 19.06 | 0.017** |

| Bachelor’s | 238 (47.6) | 46.09 | 19.54 | ||

| Master’s degree and above | 17 (3.4) | 36.04 | 16.84 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 380 (76.0) | 47.91 | 19.29 | 0.089* |

| Married | 120 (24.0) | 44.46 | 19.36 | ||

| Native status | Native | 280 (56.0) | 44.57 | 19.83 | 0.001* |

| Non-native | 220 (44.0) | 50.27 | 18.26 | ||

| Place of residence | Dormitory | 193 (38.6) | 53.75 | 15.86 | < 0.001** |

| Rental | 87 (17.4) | 31.67 | 23.10 | ||

| Personal house | 220 (44.0) | 47.32 | 17.00 | ||

| Duration of computer use (hours) | 0–1 | 183 (36.6) | 45.51 | 18.77 | 0.118** |

| 2–3 | 160 (32.0) | 49.80 | 17.08 | ||

| 4–5 | 97 (19.4) | 47.42 | 19.04 | ||

| 6 and more | 60 (12.0) | 44.05 | 25.79 | ||

| financial status | Quite enough | 44 (8.8) | 56.82 | 22.91 | < 0.001** |

| Enough | 220 (44.0) | 54.07 | 11.47 | ||

| Less than enough | 91 (18.2) | 48.16 | 15.65 | ||

| Insufficient | 145 (29.0) | 32.84 | 21.87 |

*Independent t-tests; **One-way ANOVA

According to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the skewness and kurtosis indices, all variables (except age and the “protecting privacy” dimension) had a normal distribution. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was also calculated and reported for the overall score and all dimensions of the digital health literacy questionnaire. Table 2 presents the minimum, maximum, mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and Cronbach’s alpha for all the quantitative variables.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation as well as skewness and kurtosis indices of quantitative variables among students participating in the study

| Variable | Min. amount | Max. amount | Mean | Standard Deviation | Situation | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 18.00 | 62.00 | 24.46 | 6.98 | 2.231 | 5.674 | - | |

| Operational skill | 0.00 | 100.00 | 61.84 | 32.97 | Desirable | − 0.775 | − 0.606 | 0.907 |

| Determining data relevancy | 0.00 | 100.00 | 57.58 | 29.94 | Moderate | − 0.600 | − 0.435 | 0.894 |

| Evaluating data reliability | 0.00 | 100.00 | 48.78 | 26.72 | Moderate | − 0.176 | − 0.599 | 0.825 |

| Information searching | 0.00 | 100.00 | 56.13 | 27.05 | Moderate | − 0.539 | − 0.250 | 0.849 |

| Adding content | 0.00 | 100.00 | 53.51 | 26.88 | Moderate | − 0.275 | − 0.435 | 0.853 |

| Protecting privacy | 0.00 | 100.00 | 23.51 | 21.72 | Undesirable | 1.485 | 2.179 | 0.707 |

| Navigation skill | 0.00 | 100.00 | 28.20 | 22.10 | Undesirable | 0.958 | 0.874 | 0.725 |

| Digital Health Literacy | 0.00 | 100.00 | 47.08 | 19.34 | Moderate | − 0.450 | 0.228 | 0.922 |

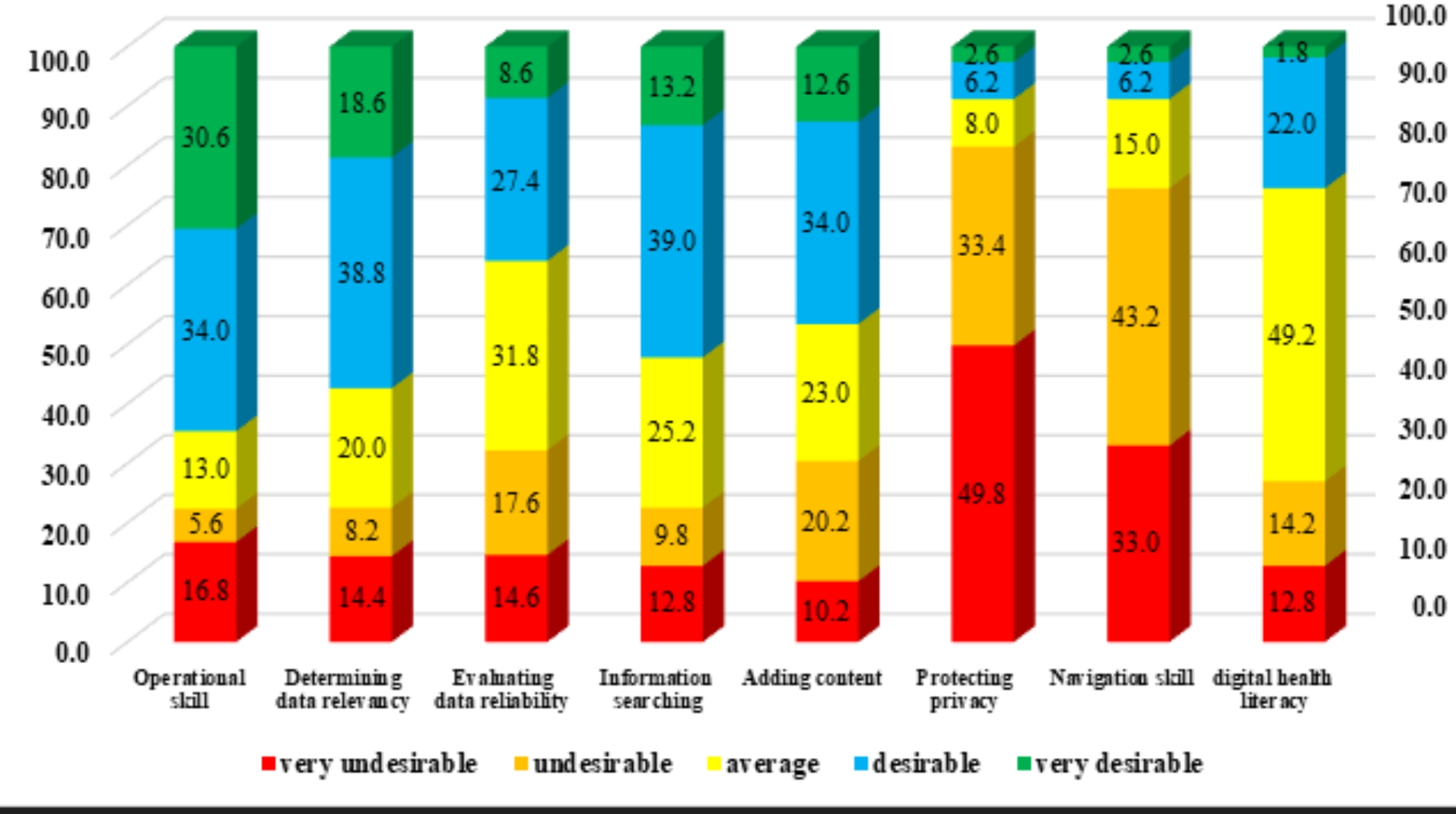

According to the questionnaire instructions, the digital health literacy scores and their various dimensions were calculated by summing the relevant questions. All the scores were then transformed to a 0-100 scale for analysis. Scores less than 20 were considered “very desirable “, 21–40 as " undesirable “, 41–60 as " moderate “, 61–80 as “good”, and 81–100 as “very desirable” digital literacy. In Fig. 1, the percentage of individuals in each level of digital health literacy (from undesirable to desirable) is shown.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the frequency of student participation according to the status of the points achieved from “undesirable” to “desirable”

In Table 3, the correlation between age and the questionnaire variables (total score and its dimensions) is reported. According to the study results, the correlation between age and navigation skill is positive and significant (r = 0.118, p < 0.001), indicating that, on average, navigation skill increases with age. However, the correlation between age and other questionnaire variables (except protecting privacy) is negative and significant (p < 0.001), suggesting that these variables, on average, decrease as age increases.

Table 3.

Correlation between age and total digital health literacy scores and ratings of its dimensions among the students participating in the study

| Variables | r* | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Operational skill | − 0.343 | < 0.001 |

| Determining data relevancy | − 0.239 | < 0.001 |

| Evaluating data reliability | − 0.245 | < 0.001 |

| Information searching | − 0.243 | < 0.001 |

| Adding content | − 0.262 | < 0.001 |

| Protecting privacy | − 0.088 | 0.050 |

| Navigation skill | 0.118 | < 0.001 |

| Digital Health Literacy | − 0.284 | < 0.001 |

* Spearman correlation coefficient

Given the normality of the digital health literacy variable, independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA were used to compare the mean digital health literacy scores of students across different levels of qualitative variables. The results are reported in Table 1. According to these tests, the digital health literacy score was significantly associated with the variables of university, gender, level of education, native status, place of residence, and satisfaction with financial status. The digital health literacy score was significantly higher in female students compared to males (P = 0.049), and in non-native students compared to native students (P = 0.001).

Then, Tukey’s post hoc test was used to compare the mean digital literacy score on different levels of qualitative variables under two conditions. According to the results of this test, the mean digital health literacy score was significantly higher among students from the technical and vocational universities of three universities: Payam Noor (P = 0.041), medical sciences (P = 0.048) and Azad (P < 0.001). There were significantly more at Payam Noor (P < 0.001) and medical sciences (P < 0.001) universities than at Azad University.

The mean digital health literacy score was significantly higher for associate students than for master’s students and higher (P = 0.023). The mean digital health literacy score among students living in dormitories is significantly higher than that of students living in private houses (P < 0.001) and rented houses (P < 0.001), and this mean for students living in personal houses is significantly higher than students who lived in rental houses (P < 0.001). With the increase in satisfaction with the financial status, the mean score of digital health literacy has also increased, that this means is significantly higher among students with completely sufficient levels of satisfaction than among students with less sufficient levels of satisfaction (P = 0.028) and insufficient (P < 0.001). This mean is significantly higher for students with sufficient levels of satisfaction than for students with less than sufficient (P = 0.027) and insufficient (P < 0.001) levels of satisfaction, and the mean for students with less than sufficient levels of satisfaction is also above the value Students with insufficient satisfaction. (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean digital health literacy at different levels of qualitative variables using Tukey’s post hoc test

| Variable | Group I | Group J | Mean difference of the groups (I-J) | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Associate’s Degree | Bachelor’s | 2.73 | 1.75 | 0.265 |

| Master’s degree and above | 12.77 | 4.82 | 0.023 | ||

| Bachelor’s | Master’s degree and above | 10.04 | 4.83 | 0.095 | |

| Place of residence | Dormitory | Personal | 6.42 | 1.76 | < 0.001 |

| Rental | 22.07 | 2.30 | < 0.001 | ||

| Personal | Rental | 15.65 | 2.25 | < 0.001 | |

| Financial status | Completely sufficient | Sufficient | 2.75 | 2.80 | 0.759 |

| Less sufficient | 8.66 | 3.11 | 0.028 | ||

| Insufficient | 23.98 | 2.92 | < 0.001 | ||

| Sufficient | Less sufficient | 5.91 | 2.11 | 0.027 | |

| Insufficient | 21.23 | 1.81 | < 0.001 | ||

| Less sufficient | Insufficient | 15.32 | 2.27 | < 0.001 |

Finally, multiple linear regression was used to examine the simultaneous effect of various variables on the overall digital health literacy score. All variables were initially entered into the model, and then the Backward Selection method was used to remove variables that were not statistically significant. The final model showed that age and satisfaction with financial status were significantly associated with digital health literacy scores. For every one-year increase in age, the digital health literacy score decreased by -0.54 units (P < 0.001). Additionally, as dissatisfaction with financial status increased (from completely sufficient to sufficient to less than sufficient to insufficient), the digital health literacy score decreased by a moderate of 9.12 units (P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The simultaneous effect of different variables on the digital health literacy score of the students participating in the study

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | SE | Standardized coefficients | t statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Width from origin | 84.57 | 3.39 | 24.97 | < 0.001 | |

| Age (years) | -0.54 | 0.11 | -0.19 | -5.00 | < 0.001 |

|

Financial status (completely sufficient, sufficient, less sufficient, insufficient) |

-9.12 | 0.76 | -0.47 | -12.04 | < 0.001 |

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the digital Health literacy in students and the associated factors. Therefore, due to the increase in false information and news that negatively impact disease prevention, understanding students’ DHL levels and related factors is essential for health policymakers and decision-makers as well as for public health interventions.

The results of this study indicate that students’ digital health literacy is moderate level, which is consistent with the results of the study by Tubaishat et al., Tsukahara et al., and Tanaka et al. [41–43]. Additionally, it is in line with previous studies conducted in Pakistan, France, and where students’ health literacy levels were relatively low and moderate [43–46]. In the Rivadeneira et al. study [47], more than half of students had sufficient health literacy, in Germany 49.9% [48], in Pakistan 54.3% [49], and in the United States [50] only 49% of students had sufficient digital health literacy. In a similar study in Iran, the score of digital health literacy among health workers was higher than in the present study [38], which was not consistent with the results of this study. The status of digital health literacy depends on socioeconomic factors (e.g. culture, environmental factors, income, etc.) [51, 52]. There are no websites like MedlinePlus (American National Library of Medicine) in Iran, on the other hand, the lack of trust of Iranian internet users and the dependence of Iranian students on unreliable sources has also caused the value of digital health literacy to decrease [53, 54]. Therefore, depending on the needs and usefulness of current information, increasing the level of digital health literacy of students, health authorities and policymakers taking measures to use online health information sources and providing health-related information on social media are essential.

Based on the results of this study, the level of digital health literacy among students was desirable in terms of “operational skills”. Considering that the first step in accessing health information is using computers and internet browsers, operational skills play an important role in enhancing individuals’ digital health literacy [55]. According to the study by Shudayfat and colleagues in Jordan and the study by Alipour and colleagues in Zahedan, respondents reported very desirable operational skills [38, 55]. In the study by Farooq and colleagues, 83% of students received a high score in digital health literacy in the area of operational skills [56]. Other studies [41, 57] have shown that university students do not have the necessary skills to search for health information on the Internet. This highlights the importance of providing students with the skills necessary to evaluate health information. People who can use computers and the Internet is better able to search for resources correctly, use them correctly and identify the right resources, which has a positive impact on the level of digital health literacy and health decisions of the people affected students. However, further studies are needed to obtain more accurate results.

Based on the results of our study, the privacy protection category was the most challenging, so it has the lowest score among the subscales and students’ ability to maintain privacy when sharing health information is unfavourable. In the Aydınlar et al. study [58] students said that they feel helpless in the face of the laws adopted by the organization to protect personal data and that the fact that students spend more time on the Internet and use information technologies more often may make them more vulnerable to cyber threats than other people [59]. Additionally, a study on web-based data protection in the German population showed that 72% of samples have doubts about the security of their data shared online and lack control over what happens to their web-based data [60]. Feeling secure in the digital world, especially when searching for health-related information, is a vital issue [61]. Therefore, suggested that in education, young people, especially female students, should be involved in security and privacy awareness programs and be aware of the use of effective passwords to protect their websites [62].

The results of the study showed that the ability of participants in the category “navigation skill” or correct orientation on websites to find suitable information is at an unfavorable level. The ability to navigate properly is a necessary skill and is influenced by individuals’ skills and the complexity of health information systems. This result is consistent with Zhao et al.‘s study, where respondents reported the lowest scores in the area of information-seeking skills [20]. In Farooq et al.‘s study, students’ navigation skills were at a desirable level, which did not align with our study results [63]. Because the students in this study had poor levels of health information navigation skills, they do not have good potential to improve self-care. Therefore, it is recommended that curriculum planners be aware of students’ navigation skills and design a program according to their needs. On the other hand, it is necessary to comprehensively integrate the topics related to digital health into their training so that they can better deal with digital health tools.

Students participating in this study had a lower chance of achieving a sufficient level of digital health literacy in the “determining data relevancy” aspect. Determining data relevancy refers to the utility of data in clinical settings [38]. We believe this is an interesting finding that suggests that as the amount of information increases, there may be challenges for individuals to find and apply appropriate information. As the amount of information increases, it may lead to challenges for individuals in finding and utilizing appropriate information. Students in the study by Rosário et al. also had moderate levels of digital health literacy in the data linkage aspect [64]. Desirable results in the data linkage scale were reported in the study by Shudayfat et al. and the study by Zakar et al., which were not consistent with the results of this study [49, 55]. Irrelevant health information can be costly and may waste people’s time, leading to errors in health planning [65]. Therefore, it is proposed to pay more attention to the importance of training students in digital areas to obtain the necessary health information.

Proper search plays an important role in obtaining accurate information as one of the dimensions of digital health literacy. In this study, students were in a moderate position in the " information searching " issue. In Nguyen et al.‘s study, information searching was associated with a moderate level of digital health literacy, which is consistent with the results of the present study [66]. Other studies showed [41, 57] that university students do not have the necessary skills to search for health information on the Internet, highlighting the importance of the need for better education in Internet searching and health information retrieval skills for students via the Internet [67]. Governments can also use popular social media (Telegram, YouTube, etc.) to integrate official health messaging [66].

According to the results of our study, students scored moderately in the category of “Adding content”. This category examines the ability to formulate health-related questions, express opinions, thoughts and feelings in writing, and write messages in a comprehensible way that is understandable to the recipient [37]. Shaabani et al. rated respondents’ attitudes toward sharing digital technology information with their audience as moderate, which is consistent with our results [63]. Since young people can be confused when exposed to different media content, it is necessary to improve competencies such as skills, knowledge and attitudes towards media technologies.

One of the topics discussed in this study was the " Evaluating data reliability " category on websites. In the present study, students had a moderate ability to identify which websites provided reliable information on health topics. This may be because in Iran it is not easy for the audience to access health information online, while in other countries this aspect of health information is emphasized and some associations and health organizations such as the Medical Library Association and the Medical Association of the United Kingdom have reputable ones Health websites introduced. The information on these websites is regularly evaluated by the Ministry of Health for medical and health-related websites. On the other hand, in Iran, the issue of evaluating health information on websites is not yet officially addressed and there are doubts about the accuracy of the information provided on these websites [54]. According to the results of the study by Bak et al., for nearly one in three students, deciding whether the information is reliable, verified, and comes from official sources is difficult [68]. A Slovenian study also showed that one out of every two students (49.3%) have problems judging the reliability of digital information [69]. However, attention should be paid to students’ ability to select reliable sources of information and to correctly use the information obtained when making health-related decisions. Therefore, the need for educational interventions for students on how to validate health information available on the Internet and other digital technologies to improve health literacy is emphasized.

Contrary to the results of other studies [70, 71], there was a significant difference between women and men in digital health literacy, such that female students had higher scores in digital health literacy compared to male students. In the study of Park et al. and Salehi et al., [72, 73] a significant difference was found between the two genders regarding e-health literacy. In a country like Iran, compared to men, as a cultural expression, women have visited health centres and health professionals more and asked more questions about health issues, and men rarely visit doctors and prefer to seek other solutions. On the other hand, for cultural reasons, Iranian women are more likely to seek health information for both their children and their partners, as they play a role in the family [74]. Further studies are needed to examine the impact of gender on students’ digital health.

We also found that non-native students and those living in dormitories had higher digital health literacy scores compared to native students. Due to the research limitations in the sources reviewed, the possibility of aligning the results was not feasible. An alternative explanation for this result may be that students from different cultures have different attitudes towards digital health literacy [75]. It is clear that the requirement of dormitory life and being away from family is the adaptation of students to different cultures and dormitory conditions, so they may use the internet more to cope with these conditions. However, our results should be interpreted with care.

Based on the results of this study, the digital health literacy scores of students in technical and vocational universities were significantly higher than those of the three universities of Payam Noor, Medical Sciences, and Azad. In the study by Dastani et al., no difference was observed in the level of electronic health literacy among students of different schools [76]. The reason for the inconsistency of the results may be the cultural differences between the studies, and the differences between the participants in terms of age and level of education.

Regarding the relationship between education level and digital health literacy, students with a higher education level had a lower digital health literacy level. In Iran, Dastani et al. study showed moderate e-health literacy in master’s and doctoral students, which was consistent with the present study [54]. We argue that in this study, associate degree students are significantly more exposed to web-based health information due to their younger age group compared to other degree programs, and their digital health literacy decreases with age. On the other hand, this problem can also be caused by their exposure to electronic resources as well as educational courses and information units that are included in their curriculum. Further research is needed to understand the relationship between educational level and digital health literacy [7].

The association between digital health literacy and living in a dormitory was also significant. These results require careful consideration of cultural fit. Students living in dormitories may spend more time on the Internet due to being away from their families [77]. Therefore, whether participants are native or non-native must be taken into account to assess the status of digital health literacy in multicultural environments.

Additionally, based on multiple linear regression analysis, the association between age and satisfaction with financial status on digital health literacy was significant. The value of students’ digital health literacy decreased as they got older. Young people are one of the primary consumers of digital information and are also at the forefront of using social media to disseminate information, which impacts their health-related behaviours [78]. According to the results of the study by Dolu et al.,, in Turkey, age was not a predictor of the level of e-health literacy [79]. In the study by Dadaczynski et al., younger age groups were more influenced by web-based health information [14]. Previous studies by Zhao et al., Cheng et al., and García-García et al. also found that age was negatively associated with digital health literacy scores [20, 80, 81]. Previous studies by van Deursen et al. showed that older adults often have lower operational and navigational skills compared to younger individuals [82]. With increasing age, individuals face more cognitive, sensory, and motor barriers and challenges in using technology for health information compared to younger individuals [83].

Additionally, based on multiple linear regression analysis, the association between age and satisfaction with financial status with digital health literacy was significant. In this study, it appears that as the economic situation improved, students’ access to the Internet improved, which led to an improvement in Internet access quality, which may lead to better search and knowledge related to digital health literacy. The study by Rivadeneira in Spain [47] and the Svendsen et al. study [84] showed that unfavourable economic and social status was associated with lower digital health literacy. Policymakers in universities and government should focus on reducing socioeconomic inequalities and identifying the role of cultural factors on digital health literacy.

One of the strengths of this study, as mentioned above, in addition to identifying the level of digital health literacy and the factors influencing it, was the use of a valid digital health literacy questionnaire, which provided an opportunity to compare the digital health literacy of Iranian university students with other countries. In the present study, this instrument showed alpha above 0.5 in the total scale and in all subscales, which is similar to the results of validation of the main scale by Drossaert and van der Vaart [37] and also the reliability of the questionnaire is consistent with a similar study by Alipour [38] in the country.

Limitations

This study has limitations. One of the cross-sectional designs of the study was that causality between the variables cannot be examined. Due to the design of the study, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the entire student population of Iranian universities. In this study, self-reporting was used as a digital health literacy questionnaire, which is one of the limitations of the present study. In this study, digital health literacy was not measured using an instrument that tests functional health literacy. The low participation of some universities in responding to the questionnaire despite continuous follow-up was another limitation of this study. Therefore, similar studies are recommended to address these limitations and implement effective interventions by policymakers to increase the level of digital health literacy at the community level.

Future recommendations

The results of this study highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the level of digital health literacy of students and indicate that the provision of correct information by the Ministry of Health can improve the level of digital health literacy in different parts of society. Also, suggested to include health literacy and digital health literacy in university curricula as part of the health communication strategy. To improve lifestyles and implement healthy habits in the lives of citizens, especially students and young people, policymakers have to define the digital health literacy roadmap to address the existing deficiencies in this area. It is necessary to conduct further studies in this area by combining other factors such as Internet access, personal and Internet skills, social impact, access to facilities cost concerns, etc. that may impact digital health literacy.

Conclusion

The level of digital health literacy among Iranian university students was moderate, and female students have higher levels of digital health literacy than their male counterparts. The connection between sociodemographic status and digital health literacy was also significant. The findings of this study can be used by health policymakers to implement a digital health infrastructure. Also, suggested that higher education programs be designed to better prepare students for the era of technological change by creating more space for digital health literacy among healthcare students. On the other hand, understanding which factors can influence the digital health literacy of young people is one of the important questions for health decision-makers.

Acknowledgements

The research team appreciates all the participants for providing their valuable knowledge and experiences.

Abbreviations

- DHL

Digital health literacy

- CSS

Cross-sectional study

Author contributions

All authors were responsible for the study. AZ and FD conceived and designed the survey. AZ and FD performed the investigation. HA analyzed the data. AZ and FD revised the paper. AZ and FD edited the paper grammatically. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported and funded by Asadabad School of Medical Sciences with researchproject number 168.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to consent not being obtained from participants for this purpose but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data collection in the present study was conducted after the approval of the Asadabad School of Medical Sciences, and Publication Ethics Board the number IR.ASAUMS.REC.1403.009. We confirm that all methods used in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The participation of students was completely voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Batterham RW, Hawkins M, Collins P, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH. Health literacy: applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health. 2016;132:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Word Health Organization. Health literacy toolkit for low-and middle-income countries: a series of information sheets to empower communities and strengthen health systems. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2015.

- 3.Smith B, Magnani JW. New technologies, new disparities: the intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. Int J Cardio. 2019;292:280–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins D, Dunn P. Digital health literacy in a person-centric world. Int J Cardio. 2019;290:154–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida S, Pinto E, Correia M, Veiga N, Almeida A, Evaluating E-H, Literacy. Knowledge, attitude, and Health Online Information in Portuguese University students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(3):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Singh G, Sawatzky B, Nimmon L, Mortenson WB. Perceived eHealth literacy and health literacy among people with spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2023;46(1):118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adil A, Usman A, Khan NM, Mirza FI. Adolescent health literacy: factors effecting usage and expertise of digital health literacy among universities students in Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welsh T, Wright M. Information literacy in the digital age: an evidence-based approach. Elsevier; 2010.

- 9.Kim J, Jin B, Livingston MA, Henan MD, Hwang J. Fundamentals of Digital Health Literacy: A Review of the Literature. 2022. Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2022/papers/32

- 10.Cheng C, Elsworth G, Osborne RH. Validity evidence based on relations to other variables of the eHealth literacy questionnaire (eHLQ): bayesian approach to test for known-groups validity. J Med Int Res. 2021;23(10):e30243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaihlanen A-M, Virtanen L, Buchert U, Safarov N, Valkonen P, Hietapakka L, et al. Towards digital health equity-a qualitative study of the challenges experienced by vulnerable groups in using digital health services in the COVID-19 era. Bmc Health serv res. 2022;22(1):188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristjánsdóttir Ó, Welander Tärneberg A, Stenström P, Castor C, Kristensson Hallström I. eHealth literacy and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of parents of children needing paediatric surgery in Sweden. Nurs Open. 2023;10(2):509–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Çetin M, Gümüş R. Research into the relationship between digital health literacy and healthy lifestyle behaviors: an intergenerational comparison. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1259412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadaczynski K, Okan O, Messer M, Leung AY, Rosário R, Darlington E, et al. Digital health literacy and web-based information-seeking behaviors of university students in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Int Res. 2021;23(1):e24097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafi M, JianMing Z, Ahmad K. Technology integration for students’ information and digital literacy education in academic libraries. Inf Discover Delivery. 2019;47(4):203–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dashti S, Peyman N, Tajfard M, Esmaeeli H. E-Health literacy of medical and health sciences university students in Mashhad, Iran in 2016: a pilot study. Electron Physician. 2017;9(3):3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Doherty D, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, Dromey M, O’Tuathaigh C, et al. Internet skills of medical faculty and students: is there a difference? BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathnayake S, Senevirathna A. Self-reported eHealth literacy skills among nursing students in Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;78:50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogel J, Albert SM, Schnabel F, Ditkoff BA, Neugut AI. Use of the internet by women with breast cancer. J Med Int Res. 2002;4(2):e866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao B-Y, Huang L, Cheng X, Chen T-T, Li S-J, Wang X-J, et al. Digital health literacy and associated factors among internet users from China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estrela M, Semedo G, Roque F, Ferreira PL, Herdeiro MT. Sociodemographic determinants of digital health literacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Med Inf. 2023;177:105124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aydın GÖ, Kaya N, Turan N. The role of health literacy in access to online health information. Proc-Soc Behav Sci. 2015;195:1683–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodie GD, Dutta MJ. Understanding health literacy for strategic health marketing: eHealth literacy, health disparities, and the digital divide. Health Market Quart. 2008;25(1–2):175–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Y, Ma D, Zhang J, Chen B. In the digital age: a systematic literature review of the e-health literacy and influencing factors among Chinese older adults. J Public Health. 2023;31(5):679–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lwin MO, Panchapakesan C, Sheldenkar A, Calvert GA, Lim LK, Lu J. Determinants of eHealth literacy among adults in China. J Health Communicat. 2020;25(5):385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Santis KK, Jahnel T, Sina E, Wienert J, Zeeb H. Digitization and health in Germany: cross-sectional nationwide survey. JMIR Public Health Surveillance. 2021;7(11):e32951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi NG, DiNitto DM. The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/Internet use. J Med Int Res. 2013;15(5):e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birru MS, Monaco VM, Charles L, Drew H, Njie V, Bierria T, et al. Internet usage by low-literacy adults seeking health information: an observational analysis. J Med Int Res. 2004;6(3):e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zrubka Z, Hajdu O, Rencz F, Baji P, Gulácsi L, Péntek M. Psychometric properties of the Hungarian version of the eHealth literacy scale. Europ J Health Econom. 2019;20:57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran HT, Nguyen MH, Pham TT, Kim GB, Nguyen HT, Nguyen N-M, et al. Predictors of eHealth literacy and its associations with preventive behaviors, fear of COVID-19, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang CL, Yang S-C, Chiang C-H. The associations between individual factors, eHealth literacy, and health behaviors among college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiferaw KB, Tilahun BC, Endehabtu BF, Gullslett MK, Mengiste SA. E-health literacy and associated factors among chronic patients in a low-income country: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2020;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo Z, Zhao SZ, Guo N, Wu Y, Weng X, Wong JY-H, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in eHealth literacy and preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong: cross-sectional study. J Med Int Res. 2021;23(4):e24577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rezakhani Moghaddam H, Ranjbaran S, Babazadeh T. The role of e-health literacy and some cognitive factors in adopting protective behaviors of COVID-19 in Khalkhal residents. Front Public Health. 2022;10:916362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frings D, Sykes S, Ojo A, Rowlands G, Trasolini A, Dadaczynski K, et al. Differences in digital health literacy and future anxiety between health care and other university students in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turan N, Güven Özdemir N, Çulha Y, Özdemir Aydın G, Kaya H, Aştı T. The effect of undergraduate nursing students’e-Health literacy on healthy lifestyle behaviour. Glob Health Promot. 2021;28(3):6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Der Vaart R, Drossaert C. Development of the digital health literacy instrument: measuring a broad spectrum of health 1.0 and health 2.0 skills. J Med Int Res. 2017;19(1):e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alipour J, Payandeh A. Assessing the level of digital health literacy among healthcare workers of teaching hospitals in the southeast of Iran. Inf Med Unlocked. 2022;29:100868. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martins S, Augusto C, Martins MR, José Silva M, Okan O, Dadaczynski K, et al. Adaptation and validation of the Digital Health Literacy Instrument for Portuguese university students. Health Promot J Aust. 2022;33:390–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeVellis RF, Thorpe CT. Scale development: theory and applications. Sage; 2021.

- 41.Tubaishat A, Habiballah L. eHealth literacy among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;42:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukahara S, Yamaguchi S, Igarashi F, Uruma R, Ikuina N, Iwakura K, et al. Association of eHealth literacy with lifestyle behaviors in university students: questionnaire-based cross-sectional study. J Med Int Rese. 2020;22(6):e18155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka J, Kuroda H, Igawa N, Sakurai T, Ohnishi M. Perceived eHealth literacy and learning experiences among Japanese undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional study. CIN: Computers Inf Nurs. 2020;38(4):198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, Ganahl K, Boltzmann L, editors. Measuring comprehensive health literacy in general populations: validation of instrument, indices and scales of the HLS-EU study. Proceedings of the 6th Annual Health Literacy Research Conference; 2014.

- 45.Allington D, Dhavan N. The relationship between conspiracy beliefs and compliance with public health guidance with regard to COVID-19. London, UK: Centre for Countering Digital Hate; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Juvinyà-Canal D, Suñer-Soler R, Boixadós Porquet A, Vernay M, Blanchard H, Bertran-Noguer C. Health literacy among health and social care university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivadeneira MF, Miranda-Velasco MJ, Arroyo HV, Caicedo-Gallardo JD, Salvador-Pinos C. Digital health literacy related to COVID-19: validation and implementation of a questionnaire in hispanic university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okan O, Bollweg TM, Berens E-M, Hurrelmann K, Bauer U, Schaeffer D. Coronavirus-related health literacy: a cross-sectional study in adults during the COVID-19 infodemic in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zakar R, Iqbal S, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. COVID-19 and health information seeking behavior: digital health literacy survey amongst university students in Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patil U, Kostareva U, Hadley M, Manganello JA, Okan O, Dadaczynski K, et al. Health literacy, digital health literacy, and COVID-19 pandemic attitudes and behaviors in US college students: implications for interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khajouei R, Salehi F. Health literacy among Iranian high school students. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41(2):215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rocha PC, Rocha DC, Lemos SMA, editors. Functional health literacy and quality of life of high-school adolescents in state schools in Belo Horizonte. CoDAS; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Tennant B, Stellefson M, Dodd V, Chaney B, Chaney D, Paige S, et al. eHealth literacy and web 2.0 health information seeking behaviors among baby boomers and older adults. J Med Int Res. 2015;17(3):E70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dastani M, Ansari M, Sattari M. Evaluation of eHealth Literacy among Non-Clinical Graduate Students; An Iranian Experience (2018). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1856. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1856

- 55.Shudayfat T, Hani SB, Al Qadire M. Assessing digital health literacy level among nurses in Jordanian hospitals. Electron J Gen Med. 2023;20(5):em525. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Farooq Z, Imran A, Imran N. Preparing for the future of healthcare: Digital health literacy among medical students in Lahore, Pakistan. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2024;40(1Part–I):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lam MK, Hines M, Lowe R, Nagarajan S, Keep M, Penman M, et al. Preparedness for eHealth: Health sciences students’ knowledge, skills, and confidence. J Inf Techno Educ: Res. 2016;15:305–34. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aydınlar A, Mavi A, Kütükçü E, Kırımlı EE, Alış D, Akın A, et al. Awareness and level of digital literacy among students receiving health-based education. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeske D, Van Schaik P. Familiarity with internet threats: beyond awareness. Computers Secur. 2017;66:129–41. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagler K, Schröder D, Schilling A, Weber T. DsiN-Sicherheitsindex 2020. Studie von Deutschland sicher im Netz. 2020.

- 61.McGraw D, Mandl KD. Privacy protections to encourage use of health-relevant digital data in a learning health system. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alqahtani MA. Factors affecting cybersecurity awareness among university students. Appl Sci. 2022;12(5):2589. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaabani M, Mehdipour Y, Kafash M. The survey of Computer Literacy among the Employees of Health Information Management at Birjand hospitals: 2018. Inform Communication Techno Educ Sci. 2018;8(4):163–76. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosário R, Martins MR, Augusto C, Silva MJ, Martins S, Duarte A, et al. Associations between COVID-19-related digital health literacy and online information-seeking behavior among Portuguese university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen X, Hay JL, Waters EA, Kiviniemi MT, Biddle C, Schofield E, et al. Health literacy and use and trust in health information. J Health Communicat. 2018;23(8):724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nguyen LHT, Vo MTH, Tran LTM, Dadaczynski K, Okan O, Murray L, et al. Digital health literacy about COVID-19 as a factor mediating the association between the importance of online information search and subjective well-being among university students in Vietnam. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:739476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jia X, Pang Y, Liu LS, editors. Online health information seeking behavior: a systematic review. Healthcare: MDPI; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bak CK, Krammer JØ, Dadaczynski K, Orkan O, von Seelen J, Prinds C, et al. Digital health literacy and information-seeking behavior among university college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study from Denmark. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vrdelja M, Vrbovšek S, Klopčič V, Dadaczynski K, Okan O. Facing the growing COVID-19 infodemic: digital health literacy and information-seeking behaviour of university students in Slovenia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pokharel PK, Budhathoki SS, Pokharel HP. Electronic health literacy skills among medical and dental interns at. BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences; 2016. [PubMed]

- 71.Robb M, Shellenbarger T. Influential factors and perceptions of eHealth literacy among undergraduate college students. On-Line J Nurs Inf. 2014;18(3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salehi L, Keikavoosi-Arani L. Investigation E-health literacy and correlates factors among Alborz medical sciences students: a cross sectional study. Int J Adol Med Health. 2021;33(6):409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park H, Lee E. Self-reported eHealth literacy among undergraduate nursing students in South Korea: a pilot study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(2):408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Atkinson N, Saperstein S, Pleis J. Using the internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Int Res. 2009;11(1):e1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Syn SY, Kim SU. College students’ health information activities on Facebook: investigating the impacts of health topic sensitivity, information sources, and demographics. J Health Communicat. 2016;21(7):743–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dastani M, Mokhtarzadeh M, Eydi M, Delshad A. Evaluating the Internet-Based Electronic Health Literacy among Students of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences. J Med Educ Develop. 2019;14(1):3–45. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bao X-M. Challenges and opportunities: a report of the 1998 library survey of Internet users at Seton Hall University. Coll Res Libr. 1998;59(6):534–42. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bin Naeem S, Kamel Boulos MN. COVID-19 misinformation online and health literacy: a brief overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dolu İ, Durmuş SÇ. The relationship of e-health literacy levels of university students studying other than health sciences with health literacy, digital literacy, media and television literacy. Turkish J Public Health. 2023;21(1):16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng C, Gearon E, Hawkins M, McPhee C, Hanna L, Batterham R, et al. Digital health literacy as a predictor of awareness, engagement, and use of a national web-based personal health record: population-based survey study. J Med Int Res. 2022;24(9):e35772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hanik B, Stellefson M. E-Health literacy competencies among undergraduate health education students: a preliminary study. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2011;14:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Deursen AJ, van Dijk JA. Internet skills performance tests: are people ready for eHealth? J Med Int Res. 2011;13(2):e1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Green G. Seniors’ eHealth literacy, health and education status and personal health knowledge. Digit Health. 2022;8:20552076221089803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Svendsen MT, Bak CK, Sørensen K, Pelikan J, Riddersholm SJ, Skals RK, et al. Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: a large national population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to consent not being obtained from participants for this purpose but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.