Abstract

Molecular techniques allowing in vivo modulation of gene expression have provided unique opportunities and challenges for behavioural studies aimed at understanding the function of particular genes or biological systems under physiological or pathological conditions. Although various animal models are available, the laboratory mouse (Mus musculus) has unique features and is therefore a preferred animal model. The mouse shares a remarkable genetic resemblance and aspects of behaviour with humans. In this review, first we describe common mouse models for behavioural analyses. As both genetic and environmental factors influence behavioural performance and need to be carefully evaluated in behavioural experiments, considerations for designing and interpretations of these experiments are subsequently discussed. Finally, common behavioural tests used to assess brain function are reviewed, and it is illustrated how behavioural tests are used to increase our understanding of the role of histaminergic neurotransmission in brain function.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E, behavioural phenotyping, behavioural testing, histamine, histamine receptor, mouse model, transgenic gene

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropin; AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AVP, arginine vasopressin; BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus; CEA, central amygdaloid nucleus; CNS, central nervous system; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; ENU, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; HPA axis, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; H1R, histamine 1 receptor; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; QTL, quantitative trait locus; RP, retinitis pigmentosa; (r)tTA, (reverse) tetracycline-controlled transactivator system; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide

MOUSE MODELS FOR BEHAVIOURAL ANALYSES

Why use a mouse?

The mouse shares many features at the anatomical, cellular, biochemical, and molecular level with humans. Also, the mouse shares with humans brain functions, such as anxiety, hunger, circadian rhythm, aggression, memory, sexual behaviour and other emotional responses. Therefore many studies use mouse models to approximate human behavioural responses under physiological and pathological conditions, for example to develop therapeutic interventions or for toxicological screenings. Mice are also relatively cheap, easily accommodated, and easy to handle. They breed in captivity and the generation time is relatively short; they reach adulthood in approx. 3 months and have an average lifespan of 2 years.

Efforts in elucidating the mouse genome have dramatically accelerated human–mouse comparative research. Using a female C57BL/6 strain, a comparative analysis was made between the 2.5 Gb-large mouse genome and the 2.9 Gb-large, almost completely sequenced human genome [1,2]. Over 90% of the mouse and human genes are syntenic. Employing an automated alignment of rat, mouse and human genomes, it was shown that 87% of human and mouse/rat sequences are aligned, and that 97% of all alignments with human sequences larger than 100 kb agree with an independent three-way synteny map [3]. Finally, nearly 99% of human genes have mouse equivalents [4]. The wide range of tools available to study known and unknown genes in mice is briefly reviewed below.

Artificially selected lines

In artificial selection, individuals are selected based on their score for a particular inheritable trait. Selected lines are created by mating individuals either scoring very high or very low for a phenotype, compared with a control group. Using these selected lines, the genes underlying the phenotype can be identified and studied. For example, voluntary high wheel running is a trait that can be used to study ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). This hyperactivity is often associated with dysfunction of the dopaminergic system. Outbred Hsd:ICR mice featuring voluntary high wheel running were used to study the effects of several dopamine receptor compounds. Administration of Ritalin, a hallmark ADHD therapeutic, reduced wheel running in selected lines, but increased wheel running in control lines. Using selective dopamine receptor antagonists, the study suggested that D1-like, but not D2-like, dopamine receptors are impaired in voluntary high-wheel-running mice [5].

QTL (quantitative trait locus) and linkage analysis

Although some disorders or phenotypes, such as obesity [6] and Huntington's disease [7], are monogenetic, most disorders are polygenetic in nature. Where single-gene phenotypes follow a Mendelian or qualitative expression pattern, it is often the case that a set of genes are involved in more complex behaviours and diseases. When a phenotype or trait shows continuous variation in a given population, it is defined as a quantitative trait. QTL analysis combines DNA marker and phenotypic trait data to locate and characterize genes that influence quantitative traits. The initial step of QTL analysis is to choose a phenotype and determine its variation. The genome of each subject is scanned with markers to identify changes. Subsequently, fine mapping might lead to a narrowed set of genes regulating the phenotype. This fine mapping of the chromosomal regions is accomplished by adopting breeding strategies that reduce the size of the QTL to one where just a few genes can be directly identified (for a review, see [8]). Alcoholism, for example, is a polygenic trait with important non-genetic determinants. Characteristics of alcoholism such as tolerance, temperature regulation and withdrawal can be identified by means of QTL analysis. Using a genetic marker database, a group of markers was found in an inbred C57BL/6 and DBA/2 cross strain that correlated with withdrawal severity, suggesting several QTLs near those markers. Interestingly, one of the QTLs on chromosome 11 lies near a region that codes for subunits of the GABAA (γ-amino-butyric acid A) receptor, an inhibitory neurotransmitter that could underlie alcohol withdrawal convulsions when perturbed [9].

Spontaneous mutations

Single nucleotide polymorphisms and frame-shift mutations are usually the result of errors made during replication of undamaged template DNA, mutagenic nucleotide substrates and endogenous DNA lesions. Although there are several mechanisms by which these spontaneous mutations can be repaired, in some cases they are the source of disorders. For example, various mutations in both humans and mice lead to selective and progressive degeneration of motor neurons [10,11]. The ‘wobbler’ mouse, for instance, has a naturally occurring mutation at chromosome 11, and has been widely used to tease out the aetiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a lethal human motor neuron disease [12].

X-ray and chemical mutagenesis

X-rays are able to induce chromosomal rearrangements with a 20–100-fold-higher frequency than that which normally occurs in spontaneous mutations. However, following induction of several hundreds of mutations in one mouse, finding mutated genes that regulate an observed phenotype remains a complicated task. The chemical mutagen chlorambucil has a much higher mutagenesis frequency, and is used as an alternative for X-ray mutagenesis. Like X-rays, chlorambucil induces chromosomal rearrangements and affects multiple genes. The offspring of the mutated mice are examined in order to find a mutation-induced change in a selected trait. An advantage of this induced variation is that potentially every gene affecting the selected trait is a target for mutagenesis.

Using chlorambucil as a mutagenesis agent, the mouse mutant scraggly (sgl) was generated. The skin of sgl mice appeared flakier than that of control littermates, and mutant mice also showed signs of hair loss. Also, sgl mice developed ulcerative dermatitis. Gene mapping revealed that sgl is mapped on chromosome 19. Fine mapping linked the hair loss mutation to an anonymous DNA marker D19Umi1; two candidate genes, Fgf8 and Cyp17, were identified and are currently being analysed [13].

Another chemical capable of inducing mutations at a high frequency is ENU (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea) [14]. This alkylating agent primarily induces point mutations in pre-mitotic spermatogonial stem cells [15], and can lead to a large number of mutated F1 progeny. The advantage of ENU over the aforementioned mutagenesis strategies is that ENU induces mutations in single genes. Generated mutations are identified by changes in phenotype. For example, the SMA-1 mouse is an ENU-induced mutant characterized by dwarfism, caused by an A→G missense mutation in exon 5 of the growth hormone gene [16]. Promising ENU mutagenesis strategies have been developed for use in genomic screens [17,18] and to generate mutations in various animal models [19–21].

Gene trapping

Gene-trapping bridges the gap between random mutagenesis and defined mutations. It has evolved into a powerful strategy that allows rapid and simultaneous genome-wide analysis, thus including the potential to investigate as-yet-unknown genes [22,23]. Furthermore, mutations generated with this technique tend to be null mutations, and can therefore be useful in exploring the function of the gene. Gene trapping involves the random introduction into the genome of a reporter vector by electroporation or retroviral infection. The vector is incorporated into an endogenous gene by creating a fusion transcript, and the mutation that the gene-trap vector creates can be identified and tracked by a reporter element such as β-galactosidase. For example, using a gene-trap strategy a mouse mutation for the gene encoding α-E-catenin, a protein associated with the cytoplasmic domain of cadherins, was found. In vitro culturing of embryos carrying the mutant revealed that, whereas normal embryos showed an outgrowth of the inner cell mass in the form of intimately associated cells, abnormal ones produced cells that remained round and did not adhere to each other. Furthermore, development of mutant embryos was blocked at the blastocyst stage, effects that parallel the defects observed in E-cadherin mutant embryos [24].

Transgenics and knockouts

In the beginning of the 1980s, modified DNA was successfully introduced into embryonic stem cells [25]. Today, this technique is routinely used to create transgenic (addition of a gene) or knockout (deletion of a gene) mice. Conventional knockouts are created by selectively creating a construct that introduces a mutation in the gene of interest, which generally deletes a key exon and ensures that the mutated gene is no longer expressed, ‘knocking out’ the functionality of the protein (for a review, see [26]). An antibiotic resistance cassette, such as Neo (the neomycin-resistance gene), is usually introduced as a marker to identify a successful knockout. This construct is incorporated into a targeting vector, which is then introduced into embryonic stem cells by electroporation or retroviral infection. Neo-resistant embryonic stem cells are implanted into blastulas from normal mice by microinjection. Subsequently, the injected blastulas are implanted into pseudo-pregnant recipient females, which go through complete gestation. The resulting chimaera offspring are cross-bred with wild-type (+/+) mice to create an F1 generation. Detection by Southern blotting or PCR identifies positive progeny, which are crossed to generate null mutants (−/−) in which the gene is effectively knocked out. Similarly, transgenic mice are obtained by introducing a functional gene of interest into the targeting vector. Deletion or expression of some genes may lead to fatality when expression of the knocked-out gene is needed to sustain life, thereby allowing these vital genes, for which there is no compensatory redundancy, to be mapped and studied. For instance, the extracellular matrix of hyaline cartilage contains an elaborated collagen fibrillar network essential for mechanical stability. Collagen fibrils contain mainly collagen II and, to a lesser extent, collagen IX. The importance of collagen II is demonstrated by collagen II-knockout mice that die at birth with severely deformed skeletons. In contrast, collagen IX-knockout mice develop an osteoarthritis-like phenotype in the knee joints [27].

Regulating transgene expression

Methods have been developed to regulate transgene expression. An advantage of this regulation is that genes can then be maintained in neonatal mice during development and turned off once mice reach adulthood (important for vital genes). Conversely, genes can be turned off early in life or after a pathological event has taken place. This is of great help in determining the time window in which the gene of interest fulfils a physiological or pathological function, and whether a pathological event is reversible, which is important in the development of treatment strategies (for a review, see [28]). Two main expression systems are most commonly used for gene regulation. In the first system, the effector is a site-specific DNA recombinase that modulates expression of a LoxP-flanked target gene [29–32]. In the second system, the effector transactivates transcription of the transgene [e.g. Tet (tetracycline)-based systems]. Two versions of Tet-based systems exist: a tTA (tetracycline-controlled transactivator system) and an rtTA (reverse tTA). In the tTA system, transcription is activated by administration of doxycycline, a tetracycline analogue which penetrates the blood–brain barrier. In contrast, in the rtTA system, transactivation is deactivated when doxycycline is administered (for a review, see [33]). Tet-based systems can be successfully used to model neurodegenerative diseases [34,35].

Considerations for designing, and interpretations of, behavioural experiments

Behavioural performance is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Therefore they need to be carefully considered in behavioural experiments. The ability to maximally control environmental conditions is a major advantage (and strength) of behavioural research involving non-human subjects over behavioural research involving human subjects. In human subjects, environmental factors such as diet, sleep cycle and stress levels are much more difficult to exert control over. In this chapter, several genetic and environmental factors influencing behavioural performance of the mouse are discussed in detail.

General health

Mice must be in good health for behavioural testing. Therefore preliminary inspections should exclude grossly abnormal mice, such as mice that lie immobile and do not react to action challenges, severely wounded mice or mice that do not look thriving and are severely ill. General health tests might reveal deficiencies that rule out certain behavioural tasks. In such cases, behavioural paradigms might be modified so that their outcome will be unaffected by the deficiencies. For example, mice that are visually impaired cannot be used in learning paradigms requiring vision to solve the task, but they could be used in olfactory discrimination tasks. In some cases, physical abnormalities are the direct result of gene mutations. For example, Stargazer mice have an ataxic gait and vestibular problems, including a distinctive head-tossing motion, caused by a mutation in a set of genes in the stargazer locus located on chromosome 15 [36].

Genetic background

The choice of the genetic background of a mouse model is also an important consideration for behavioural studies. Mouse strains differ significantly in behaviour and physiology. For instance, when aggression and anxiety was investigated in four genetic lines of mice (wild-type, outbred Swiss-CD1, inbred DBA/2 and inbred C57BL/6N mice) using aggression and novel location exploration paradigms, the genetic lines with the highest levels of inter-male aggression, such as wild-type mice and Swiss-CD1 mice, also had the highest levels of infanticide, inter-female attack and maternal aggression and displayed the lowest levels of anxiety [37]. In another study, 12 mouse models, including DBA/2, C57BL/6 and 129/SvevTacfBr mice, were compared for water maze performance and fear conditioning to assess complex learning. Consistent with polygenic regulation, all learning tasks showed strain differences in learning and sensory capabilities [38].

With the genetic background of mouse strains in mind, selection of a particular strain for a model should reflect the goal of the study. For example, C57BL/6 mice are superb learners of complex tests [39]. This strain might therefore be a better candidate in studies investigating manipulations impairing learning abilities than studies attempting to develop cognitive enhancers. On the other hand, a mouse strain that shows average performance in the behaviour(s) of interest may more easily allow the detection of improvements in performance.

Developmental milestones

If the role of a particular gene during development is the focus of study, general health of postnatal mice can be monitored by looking for specific and easily determined developmental milestones, such as fore- and hind-limb placing, ear twitch/eye opening, auditory startle and gait [40–42]. In Table 1, an example of such a test battery is shown. Neonatal mice showing a delayed progression through developmental milestones, compared with controls, could indicate developmental deficiencies. For example, the drug VA, a hybrid peptide consisting of a C-terminal segment (residues 7–28) of VIP (vasoactive intestinal peptide), a neuropeptide present in lymphoid tissue microenvironments and showing anti-inflammatory properties, and a 6-amino-acid neurotensin fragment, retards the development of behaviours such as surface righting, ear twitching and negative geotaxis [43]. VA binds both high- and low-affinity sites of the VIP receptor and, compared with VIP, has a 10-fold-higher affinity for the low-affinity site and is equipotent at the high-affinity site.

Table 1. Example of a behavioral test battery to determine developmental milestones.

| Developmental milestone | Description of test |

|---|---|

| Somatic growth | |

| Body weight | Pups are weighed daily |

| Eyelid opening | Scored 0–3 (not open–fully open) |

| Ear opening | Scored 0–3 (not open–fully open) |

| Incisor eruption | Scored 0–3 (not open–fully open) |

| Sensorimotor reflexes* | |

| Righting reflex | |

| Forelimb placing | When the dorsum of the foot is contacted against the edge of an object, the foot is raised and placed on the surface. |

| Fore and hind limb grasping | When the underside of the forefoot is stroked with a toothpick, the foot reflexes to grab the object. |

| Screen climbing | When the pup is placed on a flat screen and allowed to grip and the screen is then turned to a 90° angle, the mouse climbs upward. |

| Vibrissa placing | When a cotton swab is stroked across the mouse's vibrissa (whiskers) it places its paw on the cotton swab. |

| Cliff aversion | When the pup is placed at the edge of a cliff or tabletop with forepaws and face over the edge, it turns and crawls away from the edge. |

| Auditory startle response | When a loud clap of the hands occurs less than 10 cm away, the pup shows a whole body startle response. |

| Tactile stimulation | When von Frey hairs of 0.05 (weak) or 0.35 g (strong) are applied to the perioral area on each side of the head, the head should turn in that direction. |

| Ultrasonic vocalization | The pup is placed in a sound-attenuating chamber. Vocalizations are captured with a microphone, filtered, amplified, and recorded. The number of ultrasonic calls is analysed. |

| Homing test | A litter of pups is placed in an incubator for 30 min. They are individually placed into a plastic viewing arena with wood shavings and nesting material in one corner demarcated with tape. Time for the pup to reach the goal area is recorded in seconds. |

* Sensory motor reflexes are scored as 0 (no response), 1 (a slight response), 2 (a moderate response) and 3 (a complete response).

Animal care

All animals are very well taken care of, as all institutions accommodating mice are required by law to subject their mice to regular veterinary health checks to keep their mice in good physical health. Most journals also now require a statement ensuring that animals have been treated within governmental guidelines and legislation [for example, the Animal Welfare Act APHIS, USDA, amended January 1985, ETS No. 123 (European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes), or the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986]. Additionally, several investigators have developed excellent test batteries to ascertain the general health of a mouse [44–47] (for an example, see Table 2 [48]).

Table 2. Example of a test battery for evaluating general health of a mouse*.

| Property | Features |

|---|---|

| Physical characteristics | Weight, temperature, whiskers, bald patches, eyelid closure, piloerection† |

| General behavioural observations in home cage | Running, sniffing, licking, rearing, jumping, defaecation, urination and movement |

| Sensorimotor reflexes | Righting‡, whisker response§, eye blink, ear twitch |

| Motor responses | Wire hang∥, tail suspension¶, pole test** |

| Cliff aversion | Latency to edge††, pokes over edge‡‡ |

* The described test battery shown in the Table was adapted from the one used in [48].

† Involuntary bristling of hairs due to a sympathetic reflex.

‡ The pup is placed on its side or back, and ability to turn over to position with all four feet on the ground is recorded.

§ A cotton swab is stroked across the whiskers of the mouse, and the response of placing its forepaw on the cotton swab is recorded.

∥ The mouse is allowed to grip a wire top, then inverted and gently waved in the air, so that it grips the wire. Latency to fall on to the bedding is recorded.

¶ The mouse is securely fastened by the distal end of the tail to a flat metallic surface and suspended in a visually isolated area. The presence or absence of immobility, defined as the absence of limb movement, is recorded.

** The mouse is timed on its performance to climb up a vertically placed pole.

†† The mouse is placed at an edge and the time to move away from it is recorded.

‡‡ The number of times the mouse pokes its head over the edge is recorded.

Sex and age

Various studies pool behavioural data from male and female mice to increase statistical power. However, because there might be sex differences in behavioural performance and an increased variation in female mice due to individual differences in the oestrous cycle, it might be better not to pool male and female data. For example, sleep regulation in female mice is influenced primarily by genetic background but also, albeit to a lesser extent, by hormonal variations associated with the oestrous cycle [49]. In many cases, there is a profound difference between male and female performance. For example, transgenic mice expressing the neuropotentiating protein cholera toxin A1 subunit are models for Tourette's syndrome and OCDs (obsessive–compulsive disorders). In this model, gender-specific hormonal differences have been detected that cause male OCD mice to exhibit increased tic severity compared with female OCD mice [50].

The effects of ethanol consumption on steroid levels in mouse brain are also sex-dependent. In male, but not female, C57BL/6 mice, oral intake of ethanol significantly alters the levels of brain allopregnanolone, a neuroactive steroid that modulates GABAA receptors with a pharmacological profile similar to that of ethanol [51].

In addition to sex, age also can influence behavioural performance. Some impairments become detectable in aged animals. This is illustrated in a mouse model of RP (retinitis pigmentosa), a common group of human retinopathic diseases characterized by late-onset night blindness, loss of peripheral vision and diminished or absent electroretinogram responses. In Rp1-knockout mice, which lack the photoreceptor-specific gene Rp1, the number of rod photoreceptors decreases progressively over a period of 1 year, regardless of sex [52].

Sex- and age-related impairments are aspects of a mouse model that allow sex- and age-related disorders in humans to be studied. For instance, female, but not male, mice expressing apoE4 (apolipoprotein E4), which is involved in lipoprotein and cholesterol metabolism and is a risk factor for age-related cognitive decline and AD (Alzheimer's disease), show age-related cognitive impairments [53,54]. In addition, in CBA/J and CBA/CaJ mice, which show late-onset age-related hearing loss, the thresholds to high-frequency stimuli of the auditory brainstem response are higher in males than females. In contrast, in C57BL/6 mice which show late onset age-related hearing loss, there is massive loss of sensitivity with increasing age [55]. The potential developmental problem of blindness, particularly in strains like FVB/N, should also be taken into consideration [56].

Environmental factors

Environmental factors are also important to consider, as they can modify behavioural performance (e.g. see [57]). Environmental factors can be diverse, ranging from temperature changes, housing, noise and diet in the pre- and post-natal environment. There is a lot of interest in determining which environmental factors early in life (embryonic, prenatal or postnatal) are able to induce specific behavioural phenotypes later in life.

Prenatal environment

Differences in behaviour may also be due to environmental factors before birth. For example, the prenatal environment influences hormonal balance in unborn pups. Steroid hormones affect adjacent fetuses of different gender, modifying their development and adult behavioural performance [58]. A female fetus that developed between male fetuses entered puberty later and displayed increased aggression towards other females [59]. Conversely, a male fetus that developed between two female fetuses and was subjected to higher oestradiol levels than control males had lower levels of aggression and decreased levels of sexual activity [60]. The early postnatal environment in which the pups grow up and are not yet weaned can also influence behavioural performance in adulthood [61,62]. In large litters, it is possible that pups receive less milk and/or maternal attention, leading to increased emotional responses later in life [63,64]. Early weaned pups also demonstrated a great number of wounds on their tails and hindquarters, suggesting that the deprivation of the mother–pup interaction in early postnatal days augments anxiety and aggressiveness [65]. Also, several knockout strains of mice show inappropriate maternal behaviour. For this reason, cross-fostering of knockout offspring to a foster mother has become a relatively common procedure to allow normal pup rearing [66].

Housing conditions

Carefully monitoring and maintaining optimal temperature, humidity, opting for ventilation of cages, and selecting a cage type to house animals can optimize breeding efficiency and minimize the stress levels of the animals [67,68]. For example, the effects of different housing systems on breeding performance in DBA/2 mice were studied using three rack systems: ventilated cabinet, normal open rack and the IVC (Individually Ventilated Cage Systems) rack. All systems contained enriched or non-enriched makrolon cages. The breeding index across the three rack systems was similar in non-enriched cages. However, using IVC racks, the variation in breeding performance was higher. Using IVC racks with enrichment seems to lead to a slight, though not significant, decrease in the number of pups born [69].

Environmental stress

Noise in and outside the facility can greatly influence stress levels and food intake in mice. When construction took place near an animal housing facility, growth rates and food intake of mice housed in the ‘construction’ room were decreased compared with those housed in the ‘quiet’ room [70]. It is not only audible noise that can have an influence. Ultrasounds generated by human activity or equipment may be undetectable via human hearing, but are well within the hearing limits of most laboratory mice. This uncontrollable variable can therefore also influence their behavioural performance [71]. It is therefore recommended to minimize environmental noise or to use constant white noise to block it [71–73].

Another important variable is the lighting conditions in both experimental and housing facilities. Light–dark cycles may be varied if, for example, circadian rhythm is studied [74]. Both the intensity of the lighting as well as colour of the lighting (red light and fluorescent light are often used) are important variables that can influence animal behaviour.

When mice are transported over longer distances to a facility or within the facility from the housing room to a laboratory on the day of testing, their stress levels might be elevated due to the transport. To control for these potential effects, mice should always be transported using the shortest route possible. They should also be transported at the same time of day, as the stress response shows a circadian pattern. For instance, when mice were transported over longer distances by plane or truck, plasma corticosterone values in the mice were markedly increased at arrival, and remained elevated for 48 h [75]. When the time needed to acclimatize mice to experimental procedures was investigated, behaviours such as rearing, climbing, grooming, feeding and sexual behaviour changed immediately after transportation of mice. Although most of these behaviours stabilized quickly, on the basis of the exhibited behaviour it was suggested that even 4 days were not enough to allow the mice to fully acclimatize [76].

Diet

Most chow contains a balanced mixture of nutrients, such as vitamins, minerals, proteins and carbohydrates. Depending on the scientific hypothesis, several types of diet can be used, to which supplements are added. For example, there are many standard diets available to study drug action, diabetes, obesity, cancer or cardiovascular disorders, and it is also possible to assemble custom diets for specialized protocols [77–80]. For instance, a diet with a high fat content can be used to simulate a Western diet and induce obesity in C57BL/6 mice [81].

Giving mice free access to fluids can be particularly useful in studies investigating consumption of abused substances [82–85]. For example, a selected line can be created by the method of two-bottle preference: one bottle contains water, the other an ethanol solution. Selecting the mice with the highest preference for the ethanol solution can be used to map genes that might be involved in addiction and alcoholism. Using this technique, ethanol preference was linked to a QTL on chromosome 3 [86].

Environmental factors across laboratories

To investigate the effects of environmental factors on behavioural performance, different strains were subjected to a series of behavioural tests in three different testing facilities. The apparatus, protocols and environmental variables were maximally equated, yet there were systematic differences in the performance of the mouse strains across the laboratories [87]. After carefully reviewing the experiment, it was found that not all variables were equated, possibly explaining these differences [88].

Inter-laboratory differences are not limited to behavioural experiments, and the need to control environmental and experimental factors in behavioural studies is not different from other laboratory model systems. For example, slight differences in the content of cell-culture medium, sera or other additives are sufficient to create differences in the same cell lines. When acute myelogenous leukaemia blasts were grown in four different culture media, constitutive cytokine secretion and accessory cell function differed markedly [89]. In addition, a significant difference in technical sensitivity and specificity for two widely used PCR primer systems to detect toxoplasma was demonstrated; only one method appeared adequate for samples containing blood or tissue [90]. Finally, in 1999 a special workshop for standardization of T-cell assays investigating insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was organized to address inter-laboratory differences, because multiple and sometimes conflicting studies have identified a variety of aberrations in the cellular immune response to autoantigens. When a series of autoantigens was distributed blindly to 26 laboratories for analysis of T-cell responses and proliferation, all centres were able to reproducibly measure T-cell responses to two identical samples of tetanus toxoid. However, there was a significant inter-laboratory variation in sensitivity and extent of the proliferative response measured. Although a few laboratories could distinguish Type I diabetes patients from non-diabetic controls in proliferative responses to individual islet autoantigens, no differences in T-cell proliferation between the two groups could be identified [91]. Existence of inter-laboratory differences is now widely accepted, and various meetings and training schools try to tackle these problems.

BEHAVIOURAL TESTS AND THEIR USE TO ASSESS THE ROLE OF HISTAMINERGIC NEUROTRANSMISSION IN BRAIN FUNCTION

It is beyond the scope of the present review to describe all behavioural tests designed to study a particular phenotype. Therefore we have selected tests that are prevalent in many studies, and illustrate their use in the context of examples describing the role of histaminergic neurotransmission in brain function.

Histamine receptors

In the CNS (central nervous system), synthesis of 1-histidine into histamine by L-histidine decarboxylase takes place in a restricted population of neurons located in the TM (tuberomammillary nucleus) of the posterior hypothalamus. From the TM, histaminergic neurons project to virtually the entire brain, and in the CNS histamine is involved in many important physiological processes, such as the sleep–wake state, temperature control, cardiovascular control, eating, release of stress hormones such as CRF (corticotropin-releasing factor) and AVP (arginine vasopressin; for a review, see [92]). Four distinct histamine receptors which are all GPCRs (G-protein-coupled receptors) have been identified:

(a) The H1R (histamine H1 receptor) is located on chromosome 3 of the human genome [93] and couples to Gq/11 proteins. H1Rs are expressed in the CNS, especially in the thalamus, hippocampus, cortex, amygdala and in the basal forebrain. In the periphery, H1Rs are widely expressed in tissues such as the ileum, smooth muscle and heart. Mobilization of calcium from intracellular Ca2+ stores is the main action of H1Rs. Besides increasing the accumulation of inositol phosphate, which increases further calcium flow, Ca2+ is, among other things, also responsible for the induction of nitric oxide production, leading to relaxation of the endothelium [94,95].

(b) H2R (the histamine H2 receptor) is expressed in the periphery and in the CNS, couples to Gs proteins and is located on chromosome 5 of the human genome. In the periphery, the main role of H2R is the regulation of gastric acid secretion in the parietal cells in the endothelium. Furthermore, H2R mediates relaxation of airway and vascular smooth muscle. In the CNS, the H2R is widely expressed. Particularly high receptor density is found in the basal ganglia, the hippocampus and amygdala. High expression is also found in pyramidal cells, raphe nuclei and the substantia nigra. In the CNS, H2R activation is associated with excitation through a blocking effect of Ca2+ and K+ channels, regulation of fluid balance, and regulation of hormonal secretion [96].

(c) In 1983, the existence of H3R (the histamine H3 receptor) was discovered by showing that histamine was able to inhibit its own release from depolarized rat brain slices [97]. This action was mediated by a receptor pharmacologically distinct from H1R and H2R. Almost 16 years later, the human H3R was cloned and shown to be located on chromosome 20 of the human genome. It was found through homology searches of expressed sequence tag databases. A partial clone termed GPCR97 was revealed [98], and with this clone a human thalamus cDNA library was probed. From that screen, a full-length clone was obtained, revealing a 445-amino-acid protein that contained hallmarks of the biogenic amine subfamily of receptors [99–101]. Analysis of the histamine H3R gene suggested that alternative splicing could yield different isoforms. Indeed, to date 17 human H3R isoforms have been identified [102]. However, the function of most isoforms is still unknown. Inactive receptor isoforms may change the expression levels of active receptors in tissues where they are co-localized with functioning isoforms, or non-functional receptors could form oligomers with other proteins and receptors, thereby changing their function or expression pattern [103].

The H3R isoforms are heterogeneously distributed in rats, suggesting that isoforms may indeed have distinct roles [104]. Recently, it was found by in situ hybridization that mouse H3R isoforms have different expression patterns in the brain that are similar to those in rats [105]. In the CNS, H3Rs are widely expressed as presynaptic autoreceptors. High densities have been found in nucleus accumbens, striatum, olfactory tubercles, substantia nigra and the amygdala. Lower receptor densities have been detected in the hypothalamus. The H3R is a constitutively active receptor [106] that mediates its effects through the Gi/o class of G-proteins [107]. Not only does the H3R regulate histamine release, it also has effects on many other neurotransmitters, such as dopamine [108], serotonin or 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine) [109,110], GABA [111], norepinephrine (noradrenaline) [112], and various peptides [113].

A role for the H3R has been suggested in neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, drug abuse and several affective, appetite and sleeping disorders (reviewed in [114]). In AD, high densities of neurofibrillary tangles, a hallmark of AD, are found in the vicinity of cortically projecting histaminergic neurons [115,116] and in the tuberomammillary area in the hypothalamus [117]. In addition, reduced levels of histamine are found in the AD-affected brain [118,119]; however, this is not found in all studies [120,121].

(d) The recently discovered H4R (H4 receptor) [122] is not as widely expressed as other histamine receptors. H4R cDNA has been found mainly in medullary and peripheral haematopoietic cells such as eosinophils, neutrophils and CD4+ T-cells [123–126], suggesting an important role for the H4R in the immune system. In the CNS, H4Rs are mainly found in the cerebellum and at much lower levels in the hippocampus [123].

Role of histamine in anxiety

Anxiety is a normal response to threatening situations, and occurs routinely in daily life. This state of uneasiness and apprehension manifests itself in, for instance, restlessness, increased heart rate, transpiration, restlessness or fear. Anxiety has important protective effects in humans and animals, initiating fight-or-flight responses. However, some individuals display excessive levels of anxiety, which might indicate an anxiety disorder such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder or obsessive compulsive behaviour.

The amygdala is one of the key brain regions involved in mediating anxiety [126a]. Because anxiety involves such a graded response, a myriad of signalling pathways are involved in modulating anxiety, which are mediated by various neurotransmitters, including noradrenaline, 5-HT and GABA.

Increasing evidence supports a role of histamine in emotion and cognition. To investigate the role of histamine in anxiety, we studied the effects of acute H3R blockade on anxiety. H3R antagonists were administered to apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) and wild-type C57BL/6 male mice. As sex differences were not the objective of this study and due to the cycle, more female than male mice are required for assessing significant behavioural effects but were not available at the time; only male mice were used. In addition to the effects of acute H3R blockade on anxiety, we also investigated the effects of chronic H3R deficiency on anxiety by using H3R-knockout male mice (H3R−/−).

Open field

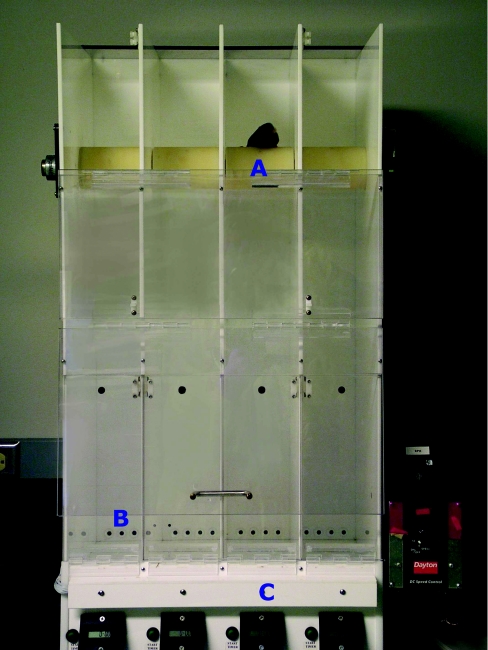

The open field test (see multimedia adjunct MOV00241.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm) is one of the most common tests used to observe general motor activity, exploratory behaviour and measures of anxiety [127–129]. A typical arena consists of a Plexiglas cage lined with infrared photobeams. A second set of infrared photobeams placed above the first allows rearing to be recorded (Figure 1). Photobeams or video tracking (see below) allow behavioural recording without the experimenter being present in the testing room; especially important when measures of anxiety are being assessed. Movements are recorded when the animal, by exploring the arena, breaks new photobeams. The distance travelled and active times, calculated from the photobeam breaks, are measures for the exerted motor activity. The open field can also be used to assess measures of anxiety. Mice will seek protection in the periphery of the arena, rather than enter the relatively more vulnerable centre. Mice that are less anxious will spend more time in the centre. We observed no genotype differences between Apoe−/− and wild-type mice in overall activity levels or measures of anxiety in the centre of the open field.

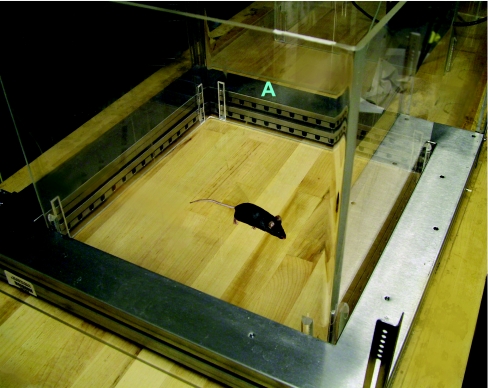

Figure 1. Open field activity.

Open field activity is measured in a 16×16 inch2 arena. IR photobeams (stemming from the area shown by the A label) are used to record movements.

Elevated plus maze

In contrast with the open field, the elevated plus maze [130,131] revealed significant differences between the two genotypes, supporting a dissociation in measures of anxiety in these two tests in genetic mutant mice. The plus maze consists of a perpendicular cross that is elevated above the floor, in which the sides of one axis are walled off (Figure 2). There are photobeams on both arms and the edges to record movement. Mice will, on one hand, prefer the safety of the enclosed, darker arms, but on the other hand like to explore the open arms and poke over the edge. Less anxious mice will venture more on to the open arms, and poke their heads more over the edges of the open arms. In this test, it is important to ensure that there are no differences in overall activity levels in the experimental groups; reduced activity could otherwise wrongfully be interpreted as increased measures of anxiety. On the basis of data recorded by photobeams, various parameters are calculated, including the total time, distance moved, and entries into the open and closed arms and the number of extensions over the edges of the open arms.

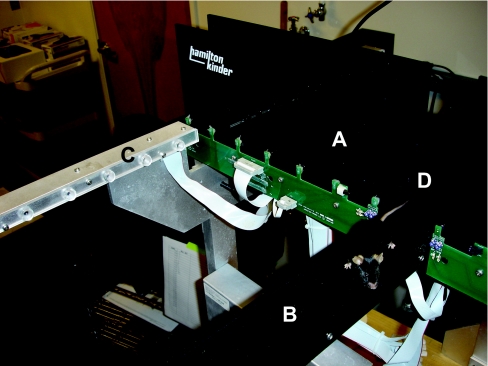

Figure 2. The elevated plus maze paradigm assesses measures of anxiety.

The enclosed arms (A) are less anxiety-provoking than the open arms (B). Movements, time spent in particular areas of the maze and pokes over the edges are recorded by IR photobeams (C). The centre area (D) connects the open and the closed arms.

Wild-type mice that were treated with thioperamide (5 mg/kg), an H3R antagonist, 1 h before testing spent significantly less time in the open arms of the plus maze (Figure 3). Also, thioperamide-treated wild-type mice did not move as much in the open arms, showed reduced entries into the open arms and showed significantly less extending over the edges of the open arms, all indicating increased measures of anxiety. In contrast with wild-type mice, Apoe−/− mice that were similarly treated with thioperamide did not show these changes in any of the anxiety measures (Figure 3).

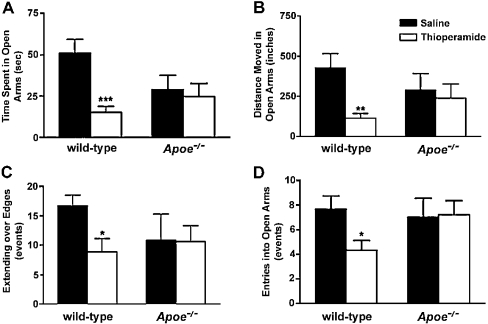

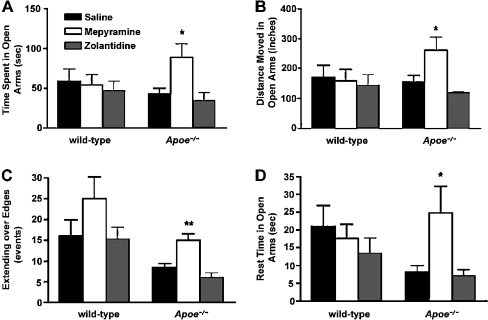

Figure 3. Measures of anxiety levels in thioperamide-treated male wild-type and Apoe−/− mice in the elevated plus maze.

Compared with saline controls, wild-type mice that received thioperamide showed significant reductions in time spent in the open arms (A), in distance moved in the open arms (B), in the number of extensions over the edges of the open arms (C), and in the number of entries into the open arms (D), indicating increased measures of anxiety after treatment with thioperamide. Apoe−/− mice showed no significant change in any of these measures of anxiety. None of the differences between wild-type and Apoe−/− mice were significant. ***P<0.001; **P<0.01; *P<0.05 compared with saline controls. n=5–15 mice were used per group (for wild-type mice, saline control, n=15, and thioperamide-treated, n=15; for Apoe−/− mice, saline control, n=7, and thioperamide-treated, n=8). Results are expressed as means±S.E.M.

To determine why there were different effects of thioperamide on measures of anxiety in wild-type and Apoe−/− mice, we first determined expression levels of H3Rs in brain regions involved in emotion or cognition. Using [3H]Nα-methylhistamine as a selective H3R radioligand, we determined H3R levels in the hypothalamus, amygdala, cortex and hippocampus by saturation binding. H3R levels were significantly lower in the amygdala, cortex and hippocampus, but not in the hypothalamus of Apoe−/− mice compared with wild-type mice; however, binding affinities were unaltered (Figure 4). In Apoe−/− mice, there might be reduced negative feedback of H3Rs, thereby increasing H1R and H2R signalling. Indeed, treatment with mepyramine (5.6 mg/kg), an H1R antagonist, 1 h before elevated plus maze testing reduced measures of anxiety in Apoe−/− but not wild-type mice compared with saline-treated genotype-matched mice (Figure 5). On the other hand, treatment with zolantidine (10 mg/kg), an H2R antagonist, did not ameliorate measures of anxiety in the elevated plus maze in either genotype. Consistent with these results, in experimental models of anxiety, stimulation of H1Rs, but not of H2Rs, increases measures of anxiety [132–134].

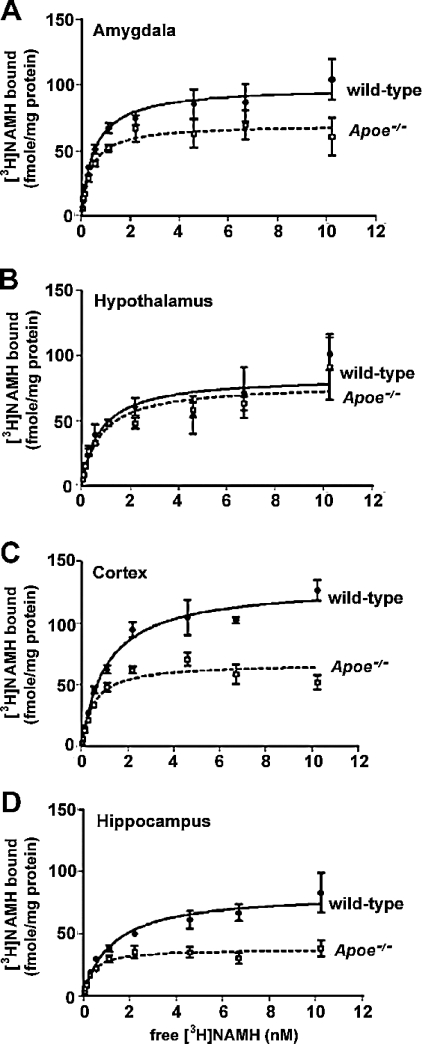

Figure 4. Saturation curve of [3H]Nα-methylhistamine binding in the amygdala (A), hypothalamus (B), cortex (C) and hippocampus (D) of male wild-type (solid line) and Apoe−/− (dashed line) mice.

Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM thioperamide. Significant differences in the total number of receptors were seen in the amygdala (P<0.05), cortex (P<0.001) and hippocampus (P<0.001). n=7 pooled mice were used per brain region for these experiments.

Figure 5. Measures of anxiety in mepyramine- and zolantidine-treated male wild-type and Apoe−/− mice in the elevated plus maze.

Compared with saline controls, Apoe−/− mice that received mepyramine showed significant increases in time spent in the open arms (A), in distance moved in the open arms (B), in the number of extensions over the edges of the open arms (C) and in the rest time in the open arms (D), indicating decreased measures of anxiety after treatment with mepyramine. Wild-type mice showed no significant change in any of these measures of anxiety. None of the differences between wild-type and Apoe−/− mice were significant. Treatment with zolantidine did not ameliorate measures of anxiety in either genotype. **P<0.01; *P<0.05 compared with saline controls. Wild-type mice, saline control, n=9; mepyramine-treated, n=8; zolantidine-treated, n=8; Apoe−/− mice, saline control, n=7; mepyramine-treated, n=7; zolantidine-treated, n=5.

Whereas the HPA axis (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis), which regulates the secretion of ACTH (adrenocorticotropin) and corticosterone, plays an important role in emotion (for a review, see [135]), the ability of mepyramine to reduce measures of anxiety in Apoe−/− mice was independent of inhibition of the HPA axis. Plasma levels of ACTH and corticosterone were measured directly after plus maze testing. Mepyramine reduced plasma corticosterone and ACTH levels in wild-type, but not in Apoe−/−, mice (Table 3). Thus, in the plus maze, effects of mepyramine on measures of anxiety are dissociated from effects attributed to the HPA axis. To investigate whether H1R levels were altered in Apoe−/− mice and could have contributed to the differential responses to mepyramine on measures of anxiety, saturation analysis with [3H]mepyramine in brain regions implicated in emotion and cognition were performed. However, no differences in H1R expression or affinity in the amygdala, hippocampus, cortex or hypothalamus were detected.

Table 3. Plasma ACTH and corticosterone levels in mepyramine- and saline-treated wild-type and Apoe−/−.

The data are represented as means±S.E.M. *P<0.05 compared with the saline-treated wild-type mice.

| Genotype | Treatment | Plasma ACTH (pg/ml) | Plasma corticosterone (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Saline (n=6) | 121±20 | 179±38 |

| Mepyramine (n=6) | 77±9* | 89±26* | |

| Apoe−/− | Saline (n=8) | 57±5 | 206±30 |

| Mepyramine (n=9) | 62±11 | 224±10 |

To determine whether extended periods of H3R deficiency have the same effects on measures of anxiety as acute receptor blockade, performance of H3R−/− mice was assessed in the elevated plus maze. H3R−/− mice spent more time in the open arms and poked over the edge of the open arms more often, indicating reduced measures of anxiety (Figure 6). Anxiety in H3R−/− mice was also evaluated in the elevated zero maze. In the elevated plus maze, the mouse needs to turn around in the open arms in order to return to the closed arms. This turn is highly anxiogenic and might constitute an unnatural behaviour for a mouse. In the elevated zero maze [136], the mouse does not need to turn around in the open areas to enter the closed areas. Our custom built zero maze (Hamilton-Kinder) consists of two enclosed areas and two open areas, identical in length with the open and closed arms in the elevated plus maze (35.5 cm; Figure 7). Mice are placed in the closed part of the maze and allowed free access for 10 min. They can spend their time either in a closed safe area or in an open area. A video tracking system (EthoVision, Noldus) is used to calculate the time spent, the distance moved, the entries into the open and closed areas, and velocity. Less anxious mice will spend more time in the open areas than more anxious mice that prefer the darker closed-off areas. As in the elevated plus maze, H3R−/− mice were less anxious, spending almost double the time in the open arms than wild-type mice (Figure 8). Thus there were striking differences in the effects of acute and chronic H3R modulation on measures of anxiety. Although, in tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli, short-term H3R blockade increased measures of anxiety, long-term H3R deficiency decreased measures of anxiety.

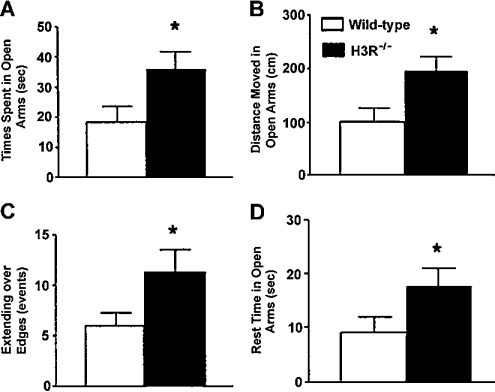

Figure 6. Elevated plus maze performance of H3R−/− and wild-type mice.

In the elevated plus maze, H3R−/− mice spent more time (A), travelled greater distances (B), extended more times over the edges of the open arms (C), and rested more time on the open arms (D) than wild-type littermates. There was no difference in distance moved or rest time in the closed arms, indicating that potential differences in overall activity levels did not account for the differences in the open arm measures. P<0.05; n=9–12 mice per genotype.

Figure 7. The elevated zero maze paradigm assesses measures of anxiety in mice.

Mice that are less anxious will spend more time in the open area (A), whereas anxious animals will prefer the darker enclosed area (B). Movement and time spent in particular areas of the maze is tracked by a video camera.

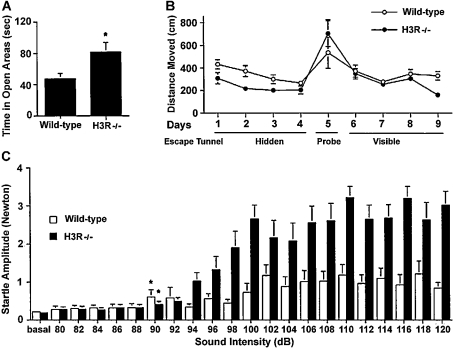

Figure 8. (A) Elevated zero maze performance of H3R−/− and wild-type mice.

(A) For the experiments examining the times spent in open areas, *P<0.05; n=10–12 mice per genotype. (B) Barnes maze performance of H3R−/− and wild-type mice. On days 1–4, mice were trained to locate a hidden escape tunnel, and on day 5, two probe trials were used with the tunnel placed under different holes. On days 6–9, mice were trained to locate a visible escape tunnel. H3R−/− mice moved less than the wild-type mice moved to locate the hidden platform location (P<0.05). There was no group difference in the number of errors, perseverance, or in the distribution of search strategies used to locate the hidden escape tunnel (n=11–12 mice per genotype). (C) Acoustic startle response of H3R−/− and wild-type mice. The mice were tested using acoustic stimuli between 80 and 120 dB for 30 ms, and the startle amplitude was recorded. H3R−/− mice showed significantly higher startle amplitudes than wild-type mice (overall ANOVA, P<0.05). *P<0.05, lowest intensity significantly different from baseline; n=11–13 mice per genotype.

Acoustic startle

In the elevated plus and zero mazes, mice can avoid the anxiety-provoking stimuli. There are also tests of anxiety involving unavoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli. An example of such a test is ‘acoustic startle’. Mice are placed in a sound-attenuated box on a sensing platform, where they are subjected to acoustic stimuli consisting of white noise. These stimuli will startle the animal, resulting in a full-body flinch recorded by the sensing platform. The acoustic startle threshold is defined as the lowest sound intensity level that elicits a body flinch. Less anxious mice might display higher thresholds than control peers and/or reduced amplitudes of acoustic startle responses. H3R−/− mice showed higher startle amplitudes than wild-type mice, but there were no genotype differences in startle thresholds (Figure 8). Thus H3R−/− mice show increased measures of anxiety in tests involving unavoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli, but decreased measures of anxiety in tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli.

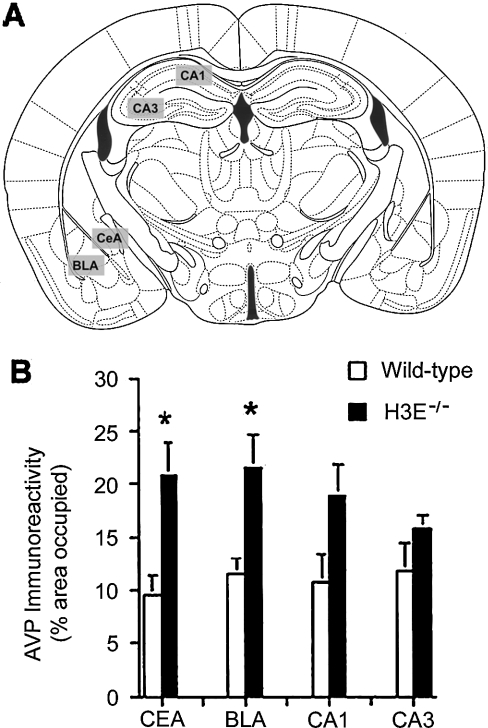

In the amygdala, the BLA (basolateral amygdaloid nucleus) plays a key role in fear conditioning and measures of anxiety in exploratory tests based on choice behaviour, such as in the elevated plus maze, whereas the CEA (central amygdaloid nucleus) plays a key role in anxiety-related responses as measured in the acoustic startle paradigm [137]. We used immunohisto-chemistry to determine brain levels of the stress hormones AVP and CRF in the amygdala and hippocampus of H3R−/− and wild-type mice to investigate possible alterations of stress hormone levels in these regions. AVP, but not CRF, levels in the CEA and BLA were higher in H3R−/− mice than in wild-type mice (Figure 9). As H3R stimulation inhibits neuronal histamine release and reduces stimulation of H1Rs, H3R deficiency in the amygdala might increase histamine release, which could increase stimulation of H1Rs, and subsequently AVP levels. Such effects might be region-specific, because H1R densities were similar in cortex [138] and lower in the hypothalamus [139] of H3R−/− compared with wild-type mice.

Figure 9. AVP immunoreactivity in the CEA, BLA, CA1 and CA3 of H3R−/− and wild-type mice.

The area occupied by immunolabelled cells (expressed as a percentage of the total image) was determined in the selected brain regions (A). (B) AVP immunoreactivity, expressed as the percentage area occupied, in the CEA, BLA, CA1 and CA3 regions of the brain. *P<0.05; n=5–6 mice per genotype.

The CEA is a target for AVP [140]. The amplitude of the acoustic startle response and the time spent in the open areas of the zero maze correlated with AVP immunoreactivity in the CEA and BLA. These data do not support specific functions for the CEA and BLA in regulation of anxiety levels involving unavoidable compared with avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli. Additionally, septal lesions or intraseptal infusion of midazolam (used to produce sleepiness and to relieve anxiety) reduced measures of anxiety in the plus maze [141], and in H3R−/− mice, hypothalamic H1Rs were down-regulated [139]. Therefore, in H3R−/− mice, the hypothalamus and/or septum might be more important for regulation of anxiety levels in tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli. Reduced H1R signalling would be expected to reduce measures of anxiety regulated by this brain region.

LEARNING AND MEMORY

Object recognition

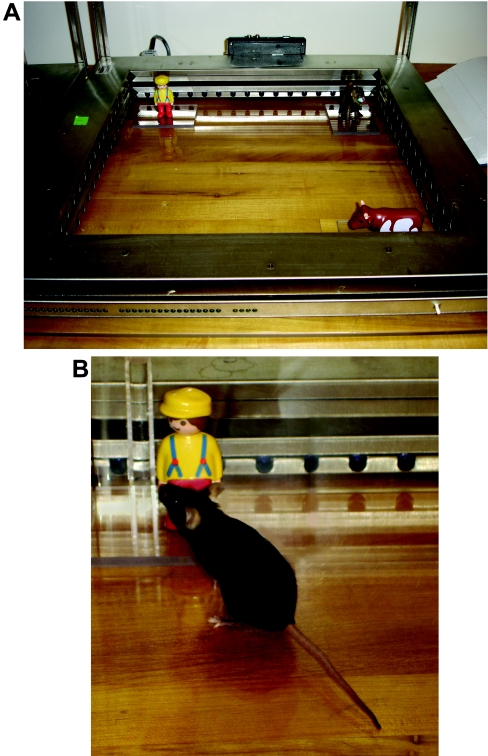

Novel object recognition (Figure 10) (see multimedia adjunct V00255.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm), which depends on the hippocampus and cortex [142,143], was used to evaluate the role of histamine in learning and memory in wild-type and Apoe−/− mice. Before testing, mice were habituated to an open field for 5 min on 3 subsequent days. Prior to the training session on day 4, two objects were placed in the open field, and the mouse was allowed to explore freely for 15 min. The session was videotaped, and the time spent with each object was manually recorded. Exploring an object was defined as close investigation within 1 cm of the objects. On day 4 of novel object training, one of the objects was replaced by a replica to remove any potential odour cues, and the other by a novel object. Again, the amount of time spent exploring each object was scored [144].

Figure 10. Object recognition.

(A) After habituation, two or three objects are placed in the open field and the mouse is allowed to explore them freely. The time spent with each object is videotaped and manually scored. Exploring an object is defined as close investigation within 1 cm of the objects. On the next day (day 5), one of the two objects is replaced by a replica to remove any potential odour cues, and the other by a novel object. In the version with three objects, after three trials with three objects, in the fourth trial one of the objects is moved to a novel location, whereas in the fifth trial one of the objects is replaced by a novel one. Again, the amount of time spent exploring each object is scored. The objects used can vary. In our setup, a man (top left), monkey (top right) and cow (bottom right) are used. (B) Example of a mouse exploring one of the objects.

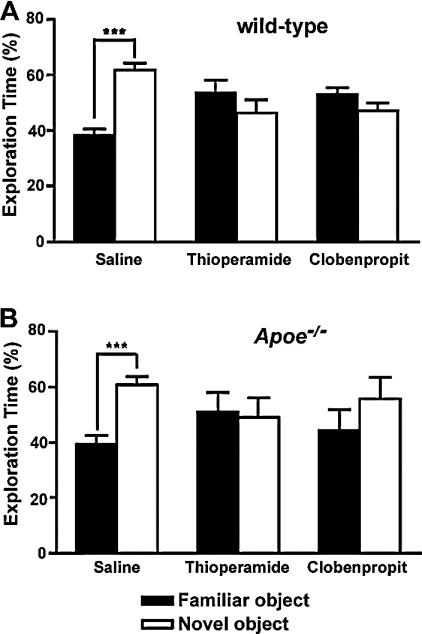

During the training sessions, both wild-type and Apoe−/− mice spent equal time with both objects. In the novel object session, mice of both genotypes that received saline injections spent significantly more time with the new object, indicative of novel object recognition (Figure 11). In contrast, mice that were treated with H3R antagonists did not show novel object recognition and spent equal amounts of time with the familiar and novel objects. When H3R−/− mice and wild-type mice were observed during a novel object recognition experiment, no differences were found between the two genotypes.

Figure 11. Novel object recognition in thioperamide- and clobenpropit-treated wild-type and Apoe−/− male mice.

The percentages of time spent exploring the novel and familiar objects on day 5 of testing are shown. Only saline-treated mice spent significantly more time exploring the novel object. ***P<0.001 novel compared with familiar object; n=5–19 mice per group. Wild-type mice, saline control, n=19; thioperamide-treated, n=15; clobenpropit-treated, n=6; Apoe−/− mice, saline control, n=10; thioperamide-treated, n=5; clobenpropit-treated, n=6.

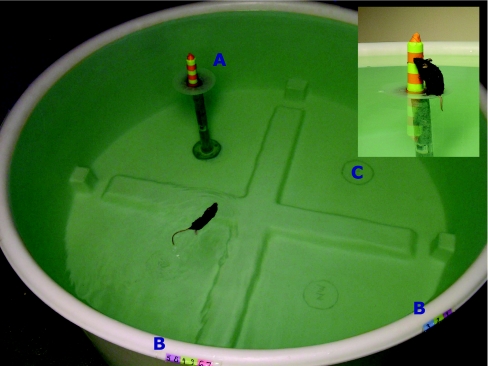

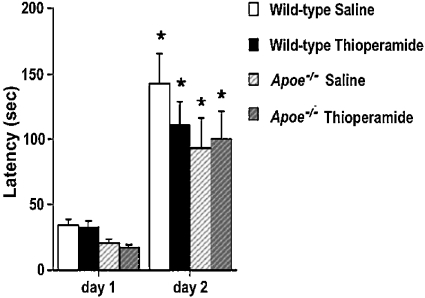

Water maze

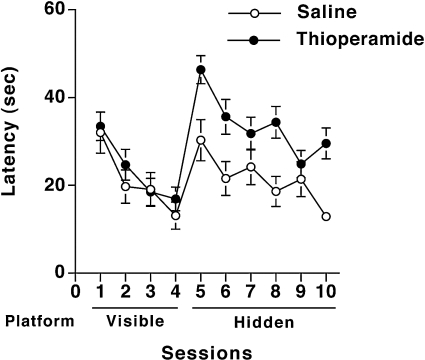

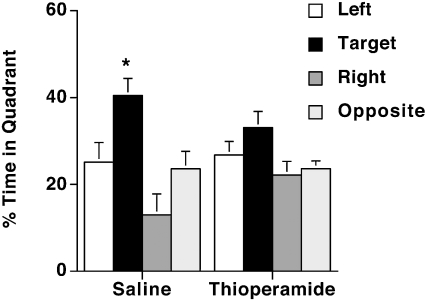

Spatial learning and memory in Apoe−/− and wild-type mice treated with H3R antagonists or saline was assessed in the Morris water maze (Figure 12), which is a widely used to study spatial learning and memory in rodents [145]. It consists of a pool filled with water, and for analysis is divided into four quadrants. During visible platform training, a platform containing a visible cue is placed in a quadrant and the mouse is trained to swim to it (see multimedia adjunct MOV00274.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm). The platform is moved to a different quadrant during each session, which consists of three trials. Visible platform training is important to exclude potential differences in vision, motor function, or motivation. After four sessions with the platform containing a visible cue, the visible cue is removed and the mouse is trained to locate the hidden platform location using spatial cues in the room. During hidden platform training (see multimedia adjuncts MOV00276.MPG and MOV00275.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm), the platform location remains constant. The starting location of the mouse is changed each trial, which maximally lasted 60 s. If the mouse failed to locate the platform within 60 s (see multimedia adjunct MOV00277.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm), it was guided to the platform location and allowed to stay on the platform for 15 s. At the end of hidden platform training, the target platform was removed to evaluate the spatial memory retention of the mouse. A mouse with spatial memory retention preferentially searches the quadrant, which previously contained the platform (target quadrant). Data were recorded with a videotracking system (Noldus Instruments EthoVision), and later analysed to calculate swim speeds, the time (latency) and distance moved to locate the platform, and the time spent in the target quadrant in relation to the other three quadrants during the probe trial (no platform present).

Figure 12. The Morris water maze assesses spatial learning and memory in mice.

Mice are dropped at selected locations (B) in a specific order and must locate the submerged platform on which a visible cue is placed (A). In later trials, the visible cue is removed, and the water is made opaque by a non-toxic, non-abrasive agent such as powdered milk or chalk to hide the platform. For analysis, the pool is divided into four quadrants; for example, (C) is one quadrant. Inset: close-up of the visible platform in the Morris water maze. Here, it is clear that the platform is submerged. In later trials, the platform becomes hidden when the visible cue is removed.

During visible platform training, there were no differences in swim speeds of saline-treated (17.6±1.2 cm/s, n=7) and thioperamide-treated (16.1±1.2 cm/s, n=9) wild-type mice. Both saline- and thioperamide-treated mice learned to locate the visible platform, but there were no treatment differences (Figure 13). However, during hidden training, thioperamide-treated mice showed poorer performance than saline-treated mice in their ability to locate the hidden platform (P<0.05; Tukey–Kramer test) (Figure 13). Consistent with these data, saline-treated mice spent more time in the target quadrant than in any other quadrants (P<0.05 compared with any other quadrant), indicating spatial memory retention (Figure 14). In contrast, thioperamide-treated animals did not show spatial memory retention; there was only a significant difference between the target and the right quadrant.

Figure 13. Water maze learning curve of thioperamide- and saline-treated wild-type mice.

Saline- and thioperamide-treated mice learned to locate the visible platform, but during hidden training thioperamide-treated mice showed poorer performance than saline-treated mice in their ability to locate the hidden platform (P<0.05). Saline control, n=7 mice; thioperamide-treated, n=9 mice.

Figure 14. Spatial memory retention of thioperamide- and saline-treated wild-type mice in the water maze.

Saline-treated mice spent significantly more time in the target quadrant than in any other quadrants (*P<0.05 compared with any other quadrant), but thioperamide-treated animals did not show spatial memory retention. Saline control, n=7 mice; thioperamide-treated, n=9 mice.

Barnes maze

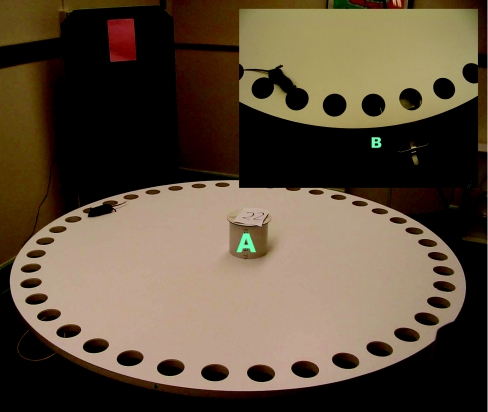

The Barnes maze also assesses spatial learning and memory in mice (Figure 15) [146,147]. The Barnes maze is based on the intrinsic capabilities of mice to explore and escape through holes. Our Barnes maze consisted of a circular surface with 40 holes around the perimeter. An escape tunnel was located beneath one of the holes. After habituation to the experimental setup, mice were trained to locate a hidden escape tunnel. To determine whether the mice used non-spatial cues to locate the tunnel, two probe trials were used, where the tunnel is moved 180° or 270° from the original position. Additionally, mice were trained to locate a visible escape tunnel, which changed location each session, by placing a coloured object directly behind the hole containing the escape tunnel. H3R−/− mice showed improved spatial learning and memory in the Barnes maze [148]. Although both wild-type and H3R−/− mice showed improved spatial learning and memory with days of training, H3R−/− mice travelled less than wild-type mice to locate the tunnel (Figure 8). The probe trials excluded strategies involving olfactory or proximal cues, and there was no difference in ability to locate the visible escape tunnel.

Figure 15. The Barnes maze consists of a circular surface with 40 holes around the perimeter.

An escape tunnel is located beneath one of the holes. Mice are trained to locate a hidden escape tunnel, and each trial starts by placing the mouse in the start cylinder (A). The trial starts by removing the start cylinder. Additionally, mice are trained to locate a visible escape tunnel, which changed locations each session, by placing a coloured object directly behind the hole containing the escape tunnel. Inset: close-up of the escape tunnel (B) the mouse is searching for.

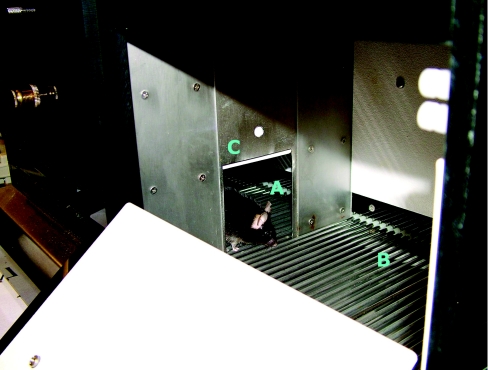

Passive avoidance

To evaluate the role of histamine in emotional learning and memory in wild-type, H3R−/− and Apoe−/− mice, these were tested for step-through passive avoidance (Figure 16). In this paradigm, a mouse is trained by using an aversive stimulus (0.3 mA for 1 s) to refrain from entering a dark area they normally would prefer [149–151]. The arena consisted of two compartments. At the start of the trial, one compartment was illuminated. The latency to enter the dark area of the arena was measured, and mice were trained until they reached a predefined criterion (e.g. they do not enter the dark compartment for three consecutive times or up to ten trials, whichever came first). The mouse was given 120 s to complete each training trial. The following day, the mouse was again placed in the lit compartment, and latency to enter the dark compartment was measured for up to 300 s. Mice that remember the conditioning stimulus will not re-enter the dark compartment or have a high latency to enter it.

Figure 16. Passive avoidance.

Mice are trained to stay inside the lit compartment (A) by receiving an aversive stimulus if they enter the darkened compartment (B). A connecting sliding door (C) separates both compartments.

Wild-type and Apoe−/− mice treated with saline or thioperamide showed a higher latency to re-enter the dark compartment on the second day of testing compared with the first day, but there were no genotype differences (Figure 17). Consistent with increased measures of anxiety of Apoe−/− mice in the elevated plus maze, the latency to enter the dark compartment on day 1 was significantly lower in Apoe−/− than wild-type mice (Figure 17; P<0.05). There were no differences between H3R−/− mice and wild-type mice in passive avoidance learning (results not shown). These data indicate that H3Rs are not required for emotional learning and memory.

Figure 17. Passive avoidance learning in thioperamide-treated wild-type and Apoe−/− mice.

On day 1, there was a significant effect of genotype on latency to enter the dark compartment (P<0.05). Wild-type mice, saline control, n=20; wild-type mice, thioperamide-treated (5 mg/kg intraperitoneally), n=21; Apoe−/− mice, saline control, n=15; Apoe−/− mice, hioperamide-treated (5 mg/kg intraperitoneally), n=16. *P<0.01 compared with day 1.

Rotorod

Motor function is mediated by several structures, starting in the cortex, brain stem and spinal cord, and terminating in skeletal muscle. The rotorod paradigm is a reliable test to study motor function and balance (Figure 18). A rotorod (rotating cylinder) is widely used [152–154] (see multimedia adjunct MOV00253.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm), of which the rev./min can be adjusted. In some test paradigms, the speed of the rod is kept constant. In others, mice start out walking on the rotorod at a low rev./min, and are trained to remain on the rotorod while the speed gradually increases. The latency to fall is recorded as mice brake photobeams when they fall. Mice with sensorimotor impairments will fall off the rotorod earlier than wild-type mice. The nature of a potential rotorod impairment can be analysed further by conducting follow-up tests assessing either muscle strength or balance. For example, the balance beam is used to determine potential impairments in balance (see multimedia adjunct MOV00259.MPG; http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/389/bj3890593add.htm). To determine whether differences in sensorimotor function might have contributed to altered performance in cognitive tests, H3R−/− and wild-type mice were tested for rotorod performance. They both improved their rotorod performance with training, but there was no genotype difference.

Figure 18. Rotorod.

The rotorod paradigm assesses motor co-ordination and balance. The speed of the rotating rod (A) is gradually increased, and latency to fall is recorded by IR photobeams (B). Timers (C) record the latency of falling.

Growth and metabolism

Obesity is a growing problem in the Western world. There is much interest in elucidating the mechanisms of energy storage and expenditure, and how these are mediated is under continued debate (for reviews, see [155,156]). There is a general consensus that peripheral signals following specific signal transduction pathways are being processed in the hypothalamus, particularly in the arctuate nucleus. Leptin seems to be the key mediator of feeding circuits, but also neuropeptide Y, ghrelin and insulin regulate this circuit [157–159]. Mice are excellent candidates as model systems for disorders such as obesity. Knockout and transgenic mice focusing on the feeding circuitry have been developed. In addition, by altering the diet, obesity or malnutrition can be induced, and the removal of food from the food container is easily measured. However, it remains difficult to ensure that the food that is taken out of the food container is actually eaten. Mice may pulverize the food instead of eating it. Metabolism can be measured in a metabolic cage, which can accurately measure consumption of liquids and oxygen, and volume of excreted urine. Daily weighing and temperature measurements allow detailed records of growth and altered metabolic rates to be kept.

To investigate the effects of histaminergic regulation of body weight regulation, food intake and energy expenditure, H3R−/− mice were housed and studied in metabolic cages. Phenotypical observations revealed that the H3R−/− mice gained significantly more body weight over the course of their adult life. They showed a greater fat deposition, had an increased fat mass and decreased lean body mass, consistent with an obese phenotype. The daily food intake in H3R−/− mice was significantly increased. Limiting the food intake for a short period decreased energy expenditure. In H3R−/− mice, basal and total oxygen consumption was reduced, consistent with reduced energy expenditure. Plasma levels of leptin and insulin were elevated, and response to leptin administration was reduced. Thus H3R deficiency in mice alters body weight, food intake and energy expenditure, resulting in obesity [139].

Social recognition behaviour

Many social disorder models in mice can be linked to human social deficit syndromes, such as autism [160] and antisocial behaviour [161]. Social recognition in mice is based on olfaction [162], as opposed to humans that predominantly use visual cues [163]. Rodent behaviour such as kin recognition, pair bond formation, selective pregnancy termination, territoriality and hierarchy all depend on the ability to successfully differentiate olfactory signatures.

Two neuropeptides, oxytocin and AVP, have an important role as neuromodulators in social behaviour [164], besides their significance in endocrine functioning [165,166]. Normally, in rodent social recognition, the olfactory investigation time will decrease with repeated or prolonged contact with con-specifics. In impaired mice, this pattern is disrupted. For instance, mice deficient in oxytocin fail to develop social memory, and do not remember recently encountered adult animals. This is indicated by longer sniffing times, despite normal olfactory abilities [167].

In another study on social recognition, recognition was investigated by introducing alien pups, i.e. mice from another litter, and pups from the parents' own litter to adult male and female mice. Sniffing and licking was scored as a measure for recognition. Both sexes spent more time sniffing the alien pup than the preceding own pup, regardless of the age of pups at testing, and more time licking the alien pup on some test days. These data indicate that adult mice are able to discriminate between their own and alien offspring, based mostly on olfactory and gustatory cues [168]. Both alien and own pups emitted fewer ultrasounds in the presence of a male than a female, suggesting an early form of learning.

Isolation-induced aggression and resident intruder paradigms

Studies of aggression behaviour in mice increase our understanding of neurobiological and molecular mechanisms mediating behaviour in social conflict and social disorders such as psychosis or borderline personality disorder, in which aggression plays an important role [169–171]. There is direct evidence for a modulatory role of various 5-HT receptors, including 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 in aggression [172]. The 5-HT receptor modulates an array of other transmitters, such as dopamine, noradrenaline and glutamate. The hippocampus, striatum and amygdala are highly innervated by serotonergic neurons that project mainly from the brainstem (for a review, see [173,174]).

Distinct levels of aggression such as play fighting, offensive and defensive fighting, maternal aggression and predatory aggression exist in rodents. One of the easiest ways to measure general antagonistic behaviour is by observation, and scoring of such characteristics as the proportion of animals fighting, tail rattling, chasing, latency for the first-attack bite, and the duration of attack bouts or flurries. High-speed red-light-sensitive cameras are needed to record these fast actions so that they are suitable for detailed analysis [169]. Two behavioural paradigms are widely used to investigate aggressive behaviour in rodents. One is isolation-induced aggression, where a male mouse is singly housed in the home cage for a period of time, after which he is paired with an opponent [175,176]. The second is the resident-intruder paradigm, in which a male is introduced into the home cage of another male. Territorial instincts make this test an easy measure for aggression, and mice do not need to be isolated prior to the test [177,178].

Histamine has been linked to aggression in rat models. To investigate H1R-mediated aggressive behaviour in mice, H1R knockout (H1R−/−) mice were observed in a resident-intruder aggression test in which test mice were confronted with an intruder (C57BL/6 mouse) after being isolated for 1 or 6 months. Fighting was increased with the increment of the numbers of sessions in wild-type mice, whereas in H1R−/− mice this tendency did not develop. Additionally, H1R−/− mice had longer attack latencies and fewer bouts of aggression compared with wild-type control mice after a 6-month isolation period. Analysis revealed that the 5-HT turnover rate was increased in H1R−/− mice [179]. Serotonergic involvement in aggression has been widely accepted [180], especially in rodents. H1Rs may modulate 5-HT levels by facilitating the release of GABA, which in turn inhibits the release of 5-HT through GABAA receptors [181].

Porsolt forced-swim test and tail suspension test

The Porsolt forced-swim test [182] and tail suspension test [183,184] measure behavioural despair in rodents, and are generally used to study depression. The forced swim test uses a cylinder filled with water in which the mouse has no other option but to swim. The water level does not allow the mouse to rest on its tail, or escape the cylinder by climbing out. Primary measures are the time floating and the time spent fighting or trying to escape. The percentages fighting or floating are derived from the primary measures. In the tail suspension test, the mouse tries to move up to escape. The time a mouse remains immobile is scored as a measure of depression. For example, the effects of melatonin as an antidepressant in mice were investigated using the Porsolt forced-swim test. Administration of pharmacological doses of melatonin reversed the period of immobility. In addition, agmatine, an endogenous cationic amine considered an endogenous ligand for imidazoline receptors, reduced immobility in the forced swimming test and in the tail suspension test in mice, without accompanying changes in ambulation in open-field experiments [182].

Conclusion

Molecular techniques have dramatically improved genetic mouse models of human behaviour under physiological and pathological conditions. These models are now available for behavioural studies aimed at understanding the function of particular genes or biological systems. However, behavioural performance is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, and both should be carefully considered in the design and interpretation of behavioural experiments.

The value of behavioural experiments for development of treatment strategies is illustrated by the example showing the role of histamine in anxiety and cognition. Consistent with our data, H3R stimulation improved memory retention of naive rats in the water maze [185], and H3R blockade impaired social memory [186]. H3R blockade might be beneficial for cognitive impairments caused by cholinergic dysfunction [187–193]. However, H3R agonists improved cognition and reduced muscarinic antagonist-induced cognitive deficits in the water maze [194]. Based on the effects of H3R blockade on scopolamine-induced amnesia and on retention of animals trained to avoid an aversive stimulus in repeated acquisition avoidance models, H3R antagonists were suggested as potential candidates for treatment of cognitive disorders such as AD [117,195], which is associated with increased anxiety and cognitive disorders. However, our data suggest that H3R antagonists not only impair object recognition in acute H3R blockade, but also increase anxiety [144,196]. Therefore the use of H3R antagonists in AD might be counter-productive and should be carefully evaluated.

Multimedia adjuncts

Acknowledgments