Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning are making groundbreaking strides in protein structure prediction. AlphaFold is remarkable in this arena for its outstanding accuracy in modelling proteins fold based solely on their amino acid sequences. In spite of these remarkable advances, experimental structure determination remains critical. Here we report severe deviations between the experimental structure of a two-domain protein and its equivalent AI-prediction. These observations are particularly relevant to the relative orientation of the domains within the global protein scaffold. We observe positional divergence in equivalent residues beyond 30 Å, and an overall RMSD of 7.7 Å. Significant deviation between experimental structures and AI-predicted models echoes the presence of unusual conformations, insufficient training data and high complexity in protein folding that can ultimately lead to current limitations in protein structure prediction.

Subject terms: Nanocrystallography, Molecular modelling

Main text

The potential for determining protein structures based solely on the amino acid sequence is rapidly evolving, driven primarily by the availability of vast numbers of experimental structures that artificial intelligence and deep learning resources can exploit. Most recently, AlphaFold1has led transformative effects in the field of structural biology by enabling fast and unprecedented accurate prediction of protein structures. Despite these highly significant contributions, several limitations and challenges2,3 in protein structure determination cannot yet be addressed by computational procedures.

Recently4, we have described the experimental structure of a marine sponge receptor via X-ray crystallography with a resolution of 1.6 Å (Table 1). This fragment corresponds to two tandem Ig-like domains that are part of the extracellular region of this receptor known as SAML (Sponge Adhesion Molecule, long form). Given the lack of a good homologue that could be used to solve the structure through molecular replacement, we used the predicted AlphaFold equivalent. This attempt failed to yield a structure solution. However, an alternative trial using, separately, the individual Ig domains led to the solution of the target structure using the same procedure5. This fact prompted us to interrogate the accuracy of the AlphaFold predicted model (AF-Q9U965-F1). Thus, we confronted it with the atomic coordinates obtained with the experimental structure. Protein–protein alignments and superpositions through the C-alpha atoms readily showed remarkable discrepancies (RMSD 7.735 Å) between the predicted and experimental structures (Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Diffraction data collection and refinement statistics.

| SAML (PDB 8OVQ) | |

|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 77.8- 1.6 (1.64—1.61) |

| Space group | P1211 |

| Unit cell | 33.08 41.16 77.80 90 90 90 |

| Total reflections | 160,776 (15,963) |

| Unique reflections | 27,240 (2722) |

| Redundancy | 4.1 (3.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.40 (99.82) |

| Mean I/sigma(I) | 9.3 (1.5) |

| Wilson B-factor | 20.56 |

| R-merge | 0.067 (0.74) |

| CC1/2 | 0.997 (0.576) |

| Reflections used in refinement | 27,228 (2722) |

| Reflections used for R-free | 4063 (414) |

| R-work | 0.169 (0.304) |

| R-free | 0.216 (0.336) |

| RMS (bonds) | 0.012 |

| RMS (angles) | 1.85 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 98 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 2.0 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.0 |

| Average B-factor | 32.5 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

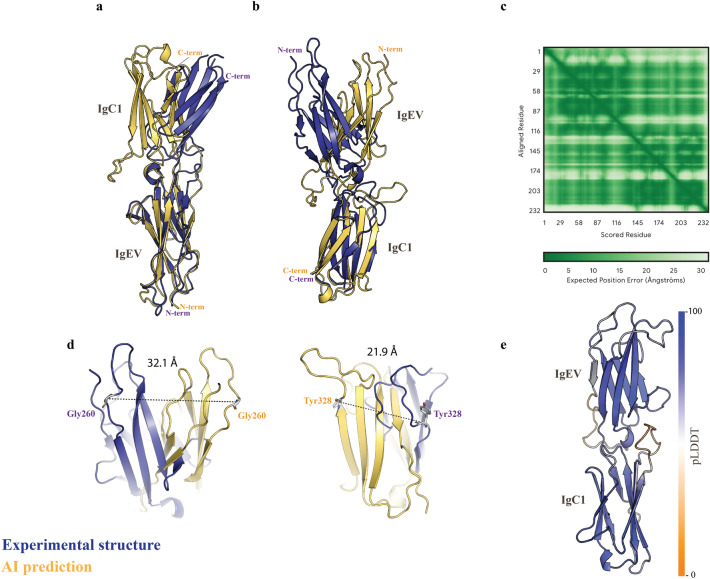

Yet, more striking differences were noticed when the structures were compared by aligning them through either the N- or the C-terminal Ig domains. In both cases, the results show evident architecture mismatches. The orientation of the free Ig-domains relative to the aligned Ig-domains shows a strong deviation in the predicted models (Fig. 1). These discrepancies are particularly remarkable as we would expect the alignments of the N- and C- terminal Ig-domains to be reasonably close to the experimental structure, regardless of the aligned reference region, whether N- or C-terminal.

Fig. 1.

Fold deviation in the predicted AI-model. a-b, the experimental structure (deep blue) and AI-derived model (yellow orange) are represented in cartoon mode and are superposed through the alpha carbons of the N-terminal (a) or C-terminal (b) Ig-domains. The N-terminal early-variable Ig-like (EV) domain and the C-terminal Ig-like C14-set are indicated. c, graphic plot (source AlphaFold) accounting for the PAE error of the predicted AlphaFold model. The dashed squares indicate the areas for expected errors of the Ig interdomain spatial relationships. d, the position of the residues showing the strongest deviations between the X-ray structure and the AlphaFold prediction are displayed in Å. e, Ribbon diagram of SAML AlphaFold structure prediction, colored according to pLDDT (predicted Local Distance Difference Test) confidence scores, with a color gradient from orange (low confidence) to blue (high confidence). The pLDDT scale bar is displayed on the right side of the image, ranging from 0 to 100.

AlphaFold outputs are accompanied by thorough details describing the confidence metrics for a particular target. These are based on a predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT), a predicted aligned error (PAE) and estimates of the predicted template modeling (pTM)1. Thus, any user is informed about the accuracy of the predicted models. The PAE plot calculated by AlphaFold accounts for the accuracy of the position and orientation of two independent domains relative to each other within a single protein. For SAML, the PAE plot (Fig. 1c) suggests moderate to low expected errors (0–10 Å for most residues), indicating relatively modest positional uncertainty for the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. However, structural comparisons (Figs. 1a-b) reveal significant disagreement in the relative orientation of these domains, as highlighted by the relative positions of the N- and C-terminal domains. The observed discrepancies between low PAE values and the disagreement in the relative orientation of domains in predicted and experimental structures can be attributed to several factors. Flexible linkers between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains may allow multiple conformations, leading to variations in relative domain positioning between predictions and experimental structures. On the other hand, insufficient evolutionary homologues or inter-domain interactions in the input data can lead to incorrect domain arrangements in computational models. In addition, experimental structures may reflect a stabilized conformation influenced by the crystallization conditions, which predictions do not always account for. Further investigation to address these discrepancies, combining computational methods with experimental validation (e.g., SAXS) and exploring domain flexibility through MD simulations can provide more accurate insights into the protein’s structural and functional dynamics.

Our results on SAML indicate that the prediction of the interdomain spatial relationship does not match that of the experimental structure. These findings would explain why our initials attempts failed to find a plausible solution in the molecular replacement procedure. On the contrary, the alignment of the individual domains yielded closely related structures (Fig. S2), as indicated by the root mean square deviations (RMSD) values below 0.9 Å (Figs. S2A and S2B).

To address the limitations associated with static structure prediction and expand the hypothetical conformational landscape of SAML, we customized the search for alternative folds by combining a low MSA depth6, different random seeds and multiple recycling steps6 (see Methods). Despite the broader range of conformations sampled, none of the predicted models could replicate the experimental structure, particularly in terms of overall fold and inter-domain alignment (Fig. 2a). Instead, the predictions consistently exhibited a conformational bias, favoring a preferential inter-domain fold missaligned with that of the X-ray-derived structure. This observation is accompanied by fluctuating and relatively low pLDDT scores (Fig. 2c), indicating moderate confidence in the structural predictions. The relative orientation of each domain remains associated with PAE values indicating poor confidence (Fig. 2d). This bias in the predicted inter-domain orientation could be due to different factors related with limitations in the AlphaFold algorithm and the input data used for the predictions. First, the sequence coverage (Fig. 2b) reveals uneven alignment depth across residues, many regions with low or no coverage, as well as persistent low sequence identity, leading to weak structural predictions. AlphaFold relies heavily on evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). In this regard, the insufficient coverage can limit its ability to accurately predict alternative inter-domain conformations, favoring a more conserved or biased fold based on the available data. Second, intrinsic limitations in sampling diverse conformations, particularly for flexible or multi-domain proteins, might cause AlphaFold to favor a single dominant fold that is “energetically plausible”. Further in this line, proteins with multi-domain architecture often exhibit significant inter-domain flexibility, resulting in multiple biologically relevant conformations. AlphaFold may struggle to capture these dynamic interactions, especially if the experimental structure represents a specific conformation stabilized by external factors (e.g., crystallization conditions).

Fig. 2.

Enhanced conformational landscape of AlphaFold predictions. a, multiple predicted protein structures generated by AlphaFold using varied random seeds and low MSA depth. To account for the relative interdomain orientation of the predicted models, the 10 conformations with the highest pLDDT values are shown aligned individually, via the alpha carbons of the N-terminal domain, with the experimental structure (shown in purple color). Each prediction is colored differently, and the pLDDT scores for each structure are highlighted below, ranging from 73.9 to 72.5, indicating moderate confidence overall. b, sequence coverage across multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) used in the prediction. The overlaid black line represents the number of matches to the target at a given position. c, pIDDT values in a per residue basis. d, PAE plots illustrating the confidence in the relative positions of residues within the predicted protein folds. e, the X-ray structure of SAML (purple) is shown aligned with the prediction with highest pTM score (0.69) using AF-cluster. A diagram with the pLDDT confidence scores in a per residue basis (middle) is shown along with the PAE plot (right).

An alternative fold prediction method based on MSA clustering and sequence similarity7 led to models ranging from low to medium confidence, as suggested by the highest predicted Template Modeling (pTM) score of 0.69, which indicates moderate accuracy in the overall topology (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 1). Nevertheless, as observed with the previous prediction method, while the structural alignment reveals a noticeable tilt in the relative orientation of the C-terminal domain between the predicted and experimental structures, the PAE plot indicates a relatively high confidence in the inter-domain orientation. (Fig. 2e). This misalignment between the experimental and predicted structures appears to be systematic rather than random, indicating a possible limitation in capturing the exact inter-domain arrangement for this protein. As mentioned, this could be due to insufficient inter-domain contact information in the input MSA or inherent flexibility in SAML.

Further discrepancies were noticed at a more local level. While these are mainly found in the loop regions, the impact of these discrepancies leads to additional deviations in the location and orientation of some beta strands that are part of the rigid core of the Ig-like β sandwich. This is expected as loops are usually associated with high flexibility and is also consistent with the AlphaFold anticipation of expected low accuracy for these regions. Nevertheless, discrepancies hit not only from a folding perspective, but concerning the type of secondary structure. For instance, and according to the Dictionary of Secondary Structure in Proteins (DSSP) for secondary structure assignment8, the A beta strand of the C-terminal Ig-domain expands from Leu274 to Leu283 (LIVEVDSSGL) in the X-ray structure, while only the portion defined by residues Ile275 to Asp279 (LIVEVDSSGL) is considered as a β strand motif by the AI model (Fig. S3A). Moreover, an additional region with a higher confidence level (90 > pLDDT > 70) presents also an unmatched secondary structure assignment (Fig. S3B). Here, the model prediction assigns a beta strand secondary motif (FNITPRY), while the X-ray structure indicates that only a fragment of this sequence corresponds to a beta strand (Fig. S3B), with the remaining fraction showing a loose area with no secondary structure (FNITPRY).

Yet, and beyond the local discrepancies that can be foreseen by the predictor confidence metrics, what is particularly relevant in this case study is the aforementioned evident divergence that exists in the spatial relationship between the two Ig-domains that conform the target protein. As already discussed, two major factors can contribute to these deviations. On the one hand, in the X-ray structure, the protein surrounding moiety (buffer, ions and other small molecules), the crystal packing contacts and other potential environmental factors might bias a particular conformation in the experimental structure. On the other hand, current AI limitations might not optimally address interdomain interactions, leading to inaccurate predictions in multidomain proteins.

The observed differences in the orientation of the single domains relative to each other between the predicted and the experimental structures highlight the complexity of these predictions, especially in multidomain proteins. A precise definition of the folding mode in multidomain proteins is pivotal for the advance of biomedicine: their role in protein–protein interactions, the potential for allosteric modulation, or their utility in structure-based drug design are just some examples. It is expected that the continuous expansion of experimental structures and subsequent training models will lead to improved algorithms that account for high-accuracy inter-domain orientation.

Methodology

Gene synthesis, cloning and plasmid purification

The extracellular region of SAML was cloned via PCR into the pAcGP67A vector with BamHI and NotI sites restriction sites at 5’ and 3’ ends, respectively. And N-terminal TwinStrep tag was fused to the native protein sequence for protein purification purposes. Purified plasmids were sequence-verified via Sanger sequencing and Sf9 insect cells (Gibco) were transduced to produce recombinant baculovirus. To this aim, 500 ng of SAML- plasmid, 100 ng BestBac 2.0 Δ v-cath/chiA Linearized Baculovirus DNA (Chimigen) and 1,2 µl TransIT (Mirus Bio) were combined with the cells. The initial baculovirus were collected after five days of incubation at 28 ºC. An amplified virus stock was generated by infecting a new culture of sf9 cells at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml with the initial baculovirus. The new baculovirus was collected from the cell supernatant through centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 min two days after infection, and stored at 4 °C.

Recombinant protein expression and purification

SAML protein was produced through infection of sf9 cells at a density of 2 × 106cells/ml using Xpress medium (Lonza) and the amplified virus stock at a 1:2000 ratio. Cells were left under constant orbital shaking for 72 h at a controlled temperature of 28 °C. The cell supernantant was then collected and processed to isolate pure target protein using a StrepTactin 4Flow cartridge (Iba Lifesciences). The eluted protein was digested with 6xHis-tagged 3C protease9 and the tag-free protein was recovered through size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 10/300 GL (Cytiva) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) pH 7.4. The sample was then passed through a NTA resin (ABT) to remove any remaining 3C protease and the flow-through was concentrated to 6.5 mg/ml in a 10-KDa MWCO Amicon (Millipore) prior to crystallization studies.

Fold predictions

The search for multiple conformational predictions of SAML was conducted using ColabFold v1.5.5. The number of recycling steps was set to 12, with mmseqs2_uniref_2 selected as the MSA mode. The MSA depth was configured with a maximum of 16:32, and the number of seeds was set to 16. Predictions based on MSA clustering and sequence similarity were performed with AF-cluster10.

Crystallization, diffraction data collection and structure solution

SAML protein crystallized in 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 30% w/v PEG4000. Crystals were cryoprotected with crystallization medium supplemented with 20% (v/v) glycerol. SAML crystals were analyzed for diffraction at the BL13-XALOC beamline of the ALBA Synchrotron (Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain). Full SAML datasets were processed with autoPROC11 and merged and scaled in AIMLESS12. The resolution cutoff was set to 1.6 Å based on the CC1/2 and I/sigma values in the high-resolution shell (Table 1). This choice was supported by a nearly 100% completeness across all shells as well as subsequent structure refinement steps. The molecular structure of SAML was determined via molecular replacement with Phaser5, using as templates the individual Ig-domains derived from the Alphafold prediction (AF-Q9U965-F1, Uniprot). Structure refinement was carried out using phenix.refine13and refmac514, including anisotropic refinement of B-factors, along with manual building in Coot15.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Xaloc beamline at ALBA Synchrotron for their assistance with X-ray diffraction data collection.

Author contributions

Conceived research project: JLS; Performed experiments: AU, JLS; Data analysis: JLS, AU; Draft writing: JLS.

Funding

Ramón y Cajal, Grant RYC‐2017‐21683, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Government of Spain (JLS). Alejandro Urdiciain is a recipient of a Margarita Salas contract funded by UPNA and the Ministry of Universities of Spain within the Plan of Recovery, Transformation and Resilience and the European Recovery Instrument Next Generation EU.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for SAML is available in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 8OVQ.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jacinto López-Sagaseta and Alejandro Urdiciain These Authors are Equaly contributed for This Work.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-89516-w.

References

- 1.Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terwilliger, T. C. et al. AlphaFold predictions are valuable hypotheses and accelerate but do not replace experimental structure determination. Nat. Methods21, 110–116 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakravarty, D. & Porter, L. L. AlphaFold2 fails to predict protein fold switching. Protein Sci.31, e4353 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urdiciain, A. et al. Unusual traits shape the architecture of the Ig ancestor molecule. BioRxiv10.1101/2024.07.22.604567 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr.40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Alamo, D., Sala, D., McHaourab, H. S. & Meiler, J. TITLE: Sampling alternative conformational states of transporters and receptors with AlphaFold2. Elife10.7554/eLife.75751 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wayment-Steele, H. K. et al. Predicting multiple conformations via sequence clustering and AlphaFold2. Nature625, 832–839 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabsch, W. & Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers22, 2577–2637 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erausquin, E. et al. Identification of a broad lipid repertoire associated to the endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR). Sci. Rep.12, 15127 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamarind Bio. State of the art computational tools for biology. https://www.tamarind.bio/ (2024).

- 11.Vonrhein, C. et al. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.67, 293–302 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, P. R. & Murshudov, G. N. How good are my data and what is the resolution?. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.69, 1204–1214 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovalevskiy, O., Nicholls, R. A. & Murshudov, G. N. Automated refinement of macromolecular structures at low resolution using prior information. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol.72, 1149–1161 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for SAML is available in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 8OVQ.